Yamaha Motor: From Tuning Forks to Two-Wheelers and Beyond

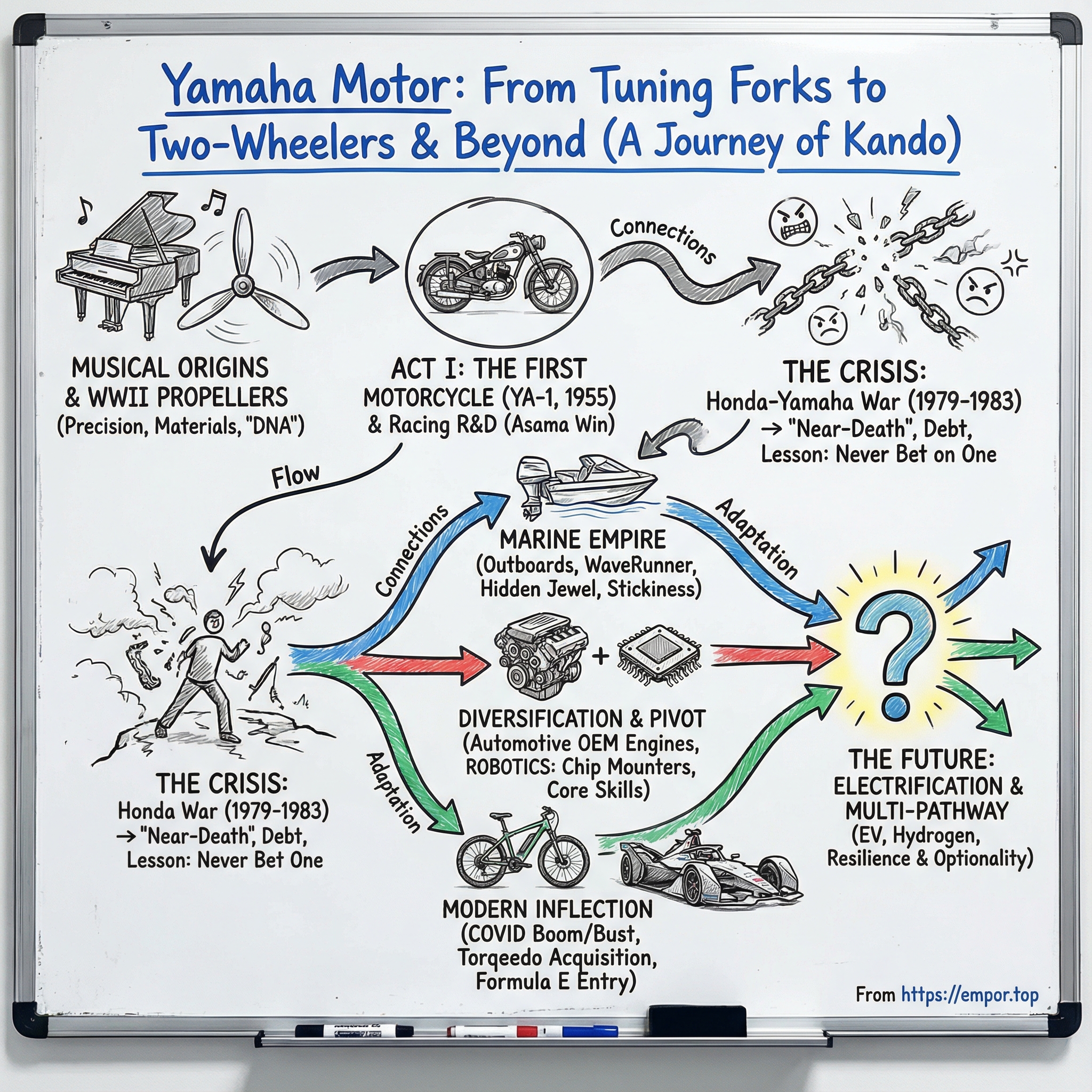

I. Introduction: The Mobility Conglomerate That Plays Every Instrument

Picture yourself walking through Yamaha Motor’s headquarters showroom in Iwata, Shizuoka. On one side: sportbikes bred on racetracks and refined for the street. Straight ahead: outboard motors built to start every morning, whether they’re bolted to a skiff in Indonesia or a center-console in Florida. Turn around and the scene flips again—industrial machines that place tiny electronic components onto circuit boards with a kind of calm, mechanical speed that feels almost unreal.

It’s an odd mix. And yet, it’s all Yamaha.

At its core, Yamaha Motor sits in a rare position: it has long been the world’s second-largest motorcycle manufacturer, it leads the world in water vehicle sales, and it holds the world’s second-largest market share in chip mounters for semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Two wheels, water, and the machinery behind the modern electronics supply chain—under one roof.

That’s what makes this story so compelling. Yamaha Motor began as a spin-off from a musical instrument company and grew into a roughly $17 billion diversified mobility powerhouse—one whose products show up in fishing villages, at yacht docks, inside factories, and on racetracks. The connective tissue isn’t “mobility” as a buzzword. It’s manufacturing capability: materials, casting, machining, and an obsession with precision.

Even the origin myth has music in it. A high-end piano’s strings pull with enormous force—close to twenty tons of tension on the frame. Building something that can hold that load, resonate correctly, and last for decades requires a particular kind of metallurgy and craftsmanship. That mindset—rigidity and elasticity, strength and feel—ends up echoing through everything Yamaha later builds.

So here’s the question that drives this deep dive: how did a company that started by repurposing idle wartime propeller machinery turn itself into one of the most strategically interesting manufacturers in the world?

Yamaha has an internal name for what it’s trying to create: a “Kando creating company.” Kando is a Japanese word for the simultaneous feelings of deep satisfaction and intense excitement you get when you encounter something of exceptional value. It’s not just a slogan. It’s Yamaha’s operating system—the idea that engineering isn’t complete until it produces an emotional response.

Over the next seven decades, that philosophy gets stress-tested again and again: by racing, by globalization, by diversification into products that look unrelated until you squint, and by a near-death corporate brawl with Honda that forces Yamaha to rethink what it is and how it survives.

If you’re building products, studying strategy, or investing in industrial businesses, Yamaha is a case study you want in your toolkit: resilience, the danger of betting the company on one line of business, and the underrated power of keeping multiple paths open as technology shifts. And it all starts in an unlikely place—inside a musical instrument company looking for its next act.

II. The Musical Origins: Yamaha Corporation and the Post-War Pivot

To understand Yamaha Motor, you first have to understand the company it came from.

Nippon Gakki Co., Ltd—today’s Yamaha Corporation—was founded in 1887 by Torakusu Yamaha to build reed organs and pianos. By the early 20th century, it had grown into Japan’s largest musical instrument maker.

Torakusu wasn’t just talented. He was relentless. When one of his first reed organs couldn’t be tuned properly, he didn’t shrug and move on. He carried the defective instrument roughly 250 kilometers from Hamamatsu to Tokyo so a physics professor could teach him what he was missing. That kind of stubborn precision—treating “good enough” as a personal insult—became a cultural inheritance.

By the 1930s, Nippon Gakki was Japan’s dominant piano manufacturer. Then the war arrived, and the business—like the country—was rerouted. During World War II, the Japanese government contracted the company to manufacture airplane propellers, first wooden and later metal.

This wasn’t a side project. It reshaped what Nippon Gakki could do. Propellers are unforgiving: precision-machined parts that have to be perfectly balanced, durable under enormous stress, and consistent at scale. To make them, the company had to build up serious capability in machine tools, casting, and metalworking—capabilities far beyond what instrument-making alone required.

And then, in August 1945, the music stopped.

Japan was devastated. Under the American occupation, manufacturing faced restrictions, and demand for products like pianos collapsed. Nippon Gakki struggled. In the early 1950s, chairman Genichi Kawakami looked at those underused wartime facilities and made a decision that sounded almost absurd for a musical instrument company: they would build small motorcycles for leisure use.

The leap wasn’t as random as it seems—because the core technical challenge of building a great piano isn’t that different from building a great engine.

A concert grand’s strings pull on its frame with close to twenty tons of force. That frame has to be rigid enough to hold tension year after year, yet elastic enough to flex and resonate in the right way—strength and feel, locked together in a single cast-iron structure. Nippon Gakki had learned how to make materials do two opposite things at once.

That know-how transfers. Engines need castings that contain explosive pressure, shed heat, resist fatigue, and manage vibration—all while staying light enough to perform. What looks like “music” on the outside is, underneath, a sophisticated manufacturing discipline.

Kawakami saw that connection. Those idle propeller machines weren’t a relic of the war; they were a starting point. Postwar Japan needed practical, affordable transportation. A motorcycle—cheaper than a car, more capable than a bicycle—fit the moment perfectly.

And so Yamaha’s next act began: not with a melody, but with metal.

III. The Birth of Yamaha Motor: The YA-1 Story (1953-1955)

On November 7, 1953, a confidential directive made the rounds among Nippon Gakki’s executive officers. President Genichi Kawakami had decided—quietly, deliberately—that the company would build a prototype motorcycle engine.

On paper, the timing looked almost irresponsible. Postwar Japan had become a motorcycle gold rush. Dozens upon dozens of manufacturers piled in, and at one point the field swelled to more than two hundred. The problem was that the boom was already turning into a shakeout. Established names like Lilac, Marusha, Tohatsu, Showa, Meguro, Miyata, and Honda weren’t going to make room for a newcomer that, as far as the market knew, built pianos.

Kawakami’s logic was the opposite of panic. He later explained it simply: “While the company was performing well and had some financial leeway, I felt the need to look for our next area of business.” He didn’t want to diversify because the company was desperate. He wanted to diversify before it became desperate.

To learn fast, the team did what many ambitious Japanese manufacturers of the era did: they started with a world-class reference design. Their template was the German DKW RT 125—arguably the most copied motorcycle in history. BSA sold its version as the Bantam. Harley-Davidson built it as the Hummer. Thanks to the design’s wartime origins, there were no enforceable patents standing in the way. For Yamaha, it was a ready-made classroom.

But “copying” still meant doing the hard part: making it reliably, consistently, and at scale. The first cylinders were cast using techniques Nippon Gakki knew from piano frames, and the early results were ugly—rough, heavy-looking shapes that workers jokingly called teapots. Sand molds couldn’t deliver the clean, elegant cooling fins that DKW produced. The design might have been borrowed, but the manufacturing craft had to be earned.

That’s where Kawakami’s style mattered. He didn’t lead from a distance. He spent time on the production floor, assembled engines with his own hands, and rode prototypes during testing. He even joined a grueling durability run of more than 10,000 kilometers on public roads around Lake Hamana. In an era when motorcycles were often sold long before they were truly proven, Yamaha was trying to build credibility the slow way—by obsessing over the product.

The first prototype was completed on August 31, 1954. By January 1955, Nippon Gakki had moved into full-scale production at the newly built Hamana Factory.

The bike was called the YA-1, a 125 cc two-stroke single. It quickly gained a reputation for being unusually high quality and dependable, and riders gave it a nickname that captured its personality: the Aka-tombo, the “Red Dragonfly.” It was slender. It was elegant. And its chestnut-red finish stood out in a market dominated by imposing, all-black machines.

Still, reputation doesn’t spread fast enough when an industry is thinning by the week. Kawakami knew there was a shortcut—one Yamaha would rely on again and again: racing.

Yamaha entered the Mount Asama Volcano Race, a punishing 12.5-mile climb over shifting volcanic ash on a mountain north of Tokyo. It was the kind of event where machines shook loose, overheated, and broke in public. The fledgling team didn’t just show up—they shocked the field by winning.

And Yamaha kept winning. The YA-1 took its class at the 3rd Mt. Fuji Ascent Race in July 1955, then swept the top three spots in the ultra-light class at the 1st Asama Highlands Race later that year.

Those victories did what marketing money couldn’t. Young riders suddenly wanted a Yamaha. The YA-1 “Red Dragonfly” became a statement: this wasn’t a piano company playing with motorcycles. This was a real manufacturer with real engineering.

The growth was immediate. Yamaha built 2,272 units in 1955, and by the time YA-1 production ended in 1957, output had climbed to 11,000 bikes.

Then came the formal separation. On July 1, 1955, Nippon Gakki spun off its motorcycle manufacturing department to establish Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd., headquartered in Hamakita, Shizuoka Prefecture, with capital of 30 million yen. Kawakami became president of the new company.

At launch, Yamaha Motor set a monthly production target of 200 units, employed around 150 people, and operated out of two wooden one-story buildings. It was humble—almost fragile.

But the early results had proven the only thing that really mattered: the “corporate DNA transfer” was real. The same discipline that made instruments precise and propellers dependable could make motorcycles that won races. Yamaha Motor’s first act wasn’t just a product launch. It was a declaration that this new company belonged on the starting line.

IV. Racing DNA and Early Expansion (1955-1979)

Those early wins at Mount Fuji and Asama didn’t just sell bikes. They set Yamaha’s operating philosophy: racing wasn’t a billboard. It was R&D, conducted in public, under the harshest conditions imaginable.

That mindset hardened fast into corporate habit. Yamaha kept showing up—across classes, across geographies—often in direct rivalry with the other rising Japanese giants: Honda, Suzuki, Kawasaki. The point wasn’t simply to win trophies. It was to force the machines, and the engineers, to level up.

In 1956, Yamaha took its first swing at international competition by entering the Catalina Grand Prix with the YA-1 and finishing sixth. Catalina Island, off the coast of California, was rugged, exposed, and unfamiliar—exactly the kind of proving ground that also happened to put Yamaha in front of an American audience for the first time.

Through the late 1950s and into the early 1960s, the results kept coming. By 1963, Yamaha’s bet on two-strokes and relentless racing paid off with its first international victory: the 250cc class at the Belgian Grand Prix. While the racing program built credibility, the business moved outward. Yamaha began planting flags overseas with new subsidiaries—Thailand in 1964, then the Netherlands in 1968—early steps in turning a Japanese motorcycle maker into a global manufacturer.

Thailand mattered for more than symbolism. It was a sign that Yamaha understood where the real growth would be: markets that needed affordable personal transportation at scale. Yamaha’s approach wasn’t to chase every customer. It leaned into motorcycles that delivered accessible performance—machines with a little more edge and excitement than the pure utilitarian baseline.

The U.S. push was taking shape too, starting with distribution. In 1958, Cooper Motors began selling Yamaha motorcycles in California. Two years later, Yamaha International Corporation began selling through dealers in the U.S., building the kind of channel presence that would determine winners and losers in a market as sprawling and fragmented as America.

And even as motorcycles grew, Genichi Kawakami’s gaze drifted—predictably—toward the next adjacency. In 1960, Yamaha moved into marine, beginning production of its first boats and outboard motors. It was the start of a new playbook: take what the company already knew how to do—engines, materials, precision manufacturing—and redeploy it into categories where those skills would matter.

That’s where Yamaha’s diversification philosophy really clicked into place: “what capabilities do we have that can be applied elsewhere?” The same casting precision that made cylinder heads dependable could support marine engines. The tuning instincts honed on bikes translated naturally to outboards. And FRP—fiberglass reinforced plastic—opened the door to building lightweight, durable forms at scale, whether that meant motorcycle parts or boat hulls.

Inside motorcycles, Yamaha was evolving too. Early on, the company had gone all-in on two-strokes—lightweight, mechanically simpler, and brutally effective for racing. But the market was changing. After producing only two-stroke models since its founding, Yamaha introduced its first four-stroke engine in 1968. Japan was expanding its expressways, riders worldwide were demanding bigger, faster machines, and four-strokes were increasingly the path to the kinds of large-displacement motorcycles that could dominate that era.

That shift wasn’t a minor tweak. Four-strokes demanded new engineering muscles—valves, cam timing, lubrication systems—the kind of complexity you don’t get to fake. But the payoff was access to larger, more premium segments, and a product roadmap that could keep stretching upward in performance and sophistication.

By the late 1970s, Yamaha had become a real force. The lineup had broadened dramatically—motorcycles ranging from small scooters to big displacement machines, a growing marine business with outboards spanning small portable units to serious power, and products tailored for specific geographies, like snowmobiles for North America. The company had momentum, global reach, and confidence.

And that’s when the danger crept in: success didn’t just make Yamaha stronger. It made Yamaha hungry.

V. The Honda-Yamaha War: A Corporate Near-Death Experience (1979-1983)

From 1979 to 1983, Honda and Yamaha fought a bruising, high-speed battle for dominance that became motorcycle-industry folklore: the Honda-Yamaha War.

It started with a declaration that was equal parts confidence and provocation. In 1979, Yamaha announced its intention to become the industry leader in motorcycles. It was bold—maybe even reckless—because Honda didn’t just lead the market. Honda had defined it. Soichiro Honda was still a living symbol of competitive obsession, and Honda’s organization knew how to win.

But Yamaha’s leadership believed the timing was finally right. Honda, in their view, was increasingly pulled toward cars—pouring capital and attention into automobiles and, supposedly, letting its motorcycle edge dull. Meanwhile, the market was expanding. Yamaha saw a window to seize the domestic crown and pushed hard with new products.

Then Yamaha made the commitment that turned a campaign into a war. In 1981, it opened an enormous new factory—so large that, at full tilt, it would make Yamaha the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer. The bet had been placed. And crucially, it wasn’t just a bet on share; it was a bet on volume staying high enough to justify all that capacity.

The financial footing under that bet was thin. Yamaha didn’t have anything like Honda’s fast-growing auto business to subsidize an all-out fight. So Yamaha invested in motorcycles at a pace its own cash generation couldn’t support and made up the difference with bank financing. Yamaha and its affiliated companies ran at close to a 3:1 debt-to-equity ratio, while the Honda group stayed below 1:1. In a price war, leverage isn’t a strategy. It’s a fuse.

Yamaha also made a second, even more dangerous assumption: that Honda wouldn’t respond with full force—that cars would keep Honda distracted. That turned out to be catastrophically wrong.

Honda didn’t play defense. It went on offense with a now-famous battle cry: “Yamaha wo tsubusu!” (“We will crush Yamaha!”)

Over the next 18 months, Honda unleashed an astonishing flood of new models—more than a hundred—turning product variety into a weapon. It wasn’t just quantity for quantity’s sake, either. Honda systematically listened to what riders and dealers wanted, then fed those insights back into rapid iterations. Yamaha wasn’t just being out-marketed. It was being out-cycled.

And Honda paired that product blitz with a second punch: price cuts. The combination was devastating. As the fight peaked, retail prices on popular models fell by more than 30%. Dealers were stocked. Promotions piled up. Honda’s line looked fresh and futuristic next to Yamaha’s.

The share shift was brutal and fast. Over that same 18-month stretch, Honda’s domestic market share rose from 38% to 47%, while Yamaha fell from 37% to 27%. Yamaha tried to respond with new launches, but it couldn’t match the pace. And when customers perceive you as the company with “last year’s bikes,” you end up competing on the only lever left: price. Yamaha found itself selling into a collapsing market at margins that evaporated, even as inventory costs soared.

By early 1983, Yamaha’s motorcycle sales had fallen by more than half and losses mounted. Unsold Yamaha stock in Japan was estimated to be roughly half of all unsold industry inventory, and at Yamaha’s sales pace it amounted to about a year’s worth of bikes sitting still—capital locked up in metal.

The balance sheet cracked under the strain. Debt-to-equity ballooned from around 3:1 in 1981 to 7:1 in 1983. In April 1983, Yamaha announced a second-half loss of 4 billion yen. Dividends were slashed by 80%, with no next dividend scheduled. Production plans were cut, and the company announced it would reduce headcount by 700 over two years.

To avoid bankruptcy, Yamaha sold fixed assets—land, buildings, equipment—at bargain prices. Average salaries were cut. Bonuses were stopped. The war that began as a push for leadership had become a fight for survival.

And eventually, Yamaha had to do the thing proud challengers almost never do in public: surrender the narrative. “We want to end the H-Y war. It is our fault,” declared Eguchi, Yamaha’s president. “We cannot match Honda’s sales and product strength. Of course there will be competition in the future, but it will be based on a mutual recognition of our respective positions.”

By 1983, the war was effectively over—and the verdict was clear. Yamaha had lost, decisively.

But it didn’t come away empty-handed. The pressure forged a culture that didn’t flinch at daunting problems—a mindset of having to “figure out a way to do it ourselves.” It built foundations for training and fostering engineers under real combat conditions. And it accelerated hard-won manufacturing advances, including new casting technologies, because when a company is cornered, it either learns fast or disappears.

Yamaha’s young engineers threw themselves into the work without fear of failure because failure wasn’t abstract anymore. For Yamaha, this wasn’t about grooming talent. It was corporate life and death.

The Honda-Yamaha War is still studied as a defining Japanese corporate episode: a cautionary tale about betting too much on one business, underestimating a competitor’s resolve, and what happens when aggressive expansion outruns financial discipline.

VI. The Post-War Rebuild and Diversification (1983-2000s)

The humiliation of 1983 didn’t just sting. It rewired Yamaha Motor’s strategy.

The lesson was blunt: never again bet the company on a single product line. Never again try to outlast a larger, better-capitalized rival in a war of attrition. If Yamaha was going to keep swinging in a world dominated by giants, it needed multiple engines of profit—businesses that could carry the company when one cycle inevitably turned ugly.

So Yamaha diversified. Aggressively.

The company’s product roster grew to include motorcycles, scooters, motorized bicycles, boats, sail boats, personal watercraft, swimming pools, utility boats, fishing boats, outboard motors, 4-wheel ATVs, recreational off-road vehicles, go-kart engines, golf carts, multi-purpose engines, electrical generators, water pumps, automobile engines, surface mounters, intelligent machinery, electrical power units for wheelchairs, and helmets.

It reads like a catalog from three different corporations. But there was method in the sprawl. Yamaha kept asking the same question: where can our core capabilities—precision manufacturing, engines, and materials expertise—matter enough to win? And then it entered those categories with the patience to build position over years, not quarters.

One of the most revealing expansions was into automobile engines—not cars, but the high-value, high-difficulty parts of cars.

In 1984, Yamaha Motor executives signed a contract with Ford to develop, produce, and supply a compact 60° 3.0 Liter DOHC V6 engine for transverse application in the 1989–95 Ford Taurus SHO.

For the Taurus SHO (Super High Output), Yamaha developed a high-performance 3.0L V6 based off Ford’s existing Vulcan V6 architecture. The result was a serious piece of engineering for the era: double overhead cams, 24 valves, aluminum heads, and a variable-length intake manifold, delivering 220 hp.

And it wasn’t just powerful—it loved to rev. The 3.0-litre V6 would spin to 7,300 rpm (and was apparently capable of more than 8,000), which was wild for a mainstream American sedan at the time. In output terms, this warmed-over Taurus could match—or beat—multiple V8 Fox Body Mustangs of the era.

More important than the headline specs was what the program signaled to the industry: Yamaha could be a credible, world-class partner for global automakers that wanted elite performance without building the entire capability in-house. From 1993 to 1995, the SHO engine was produced in 3.0 and 3.2 Liter versions. Yamaha later jointly designed a 3.4 Liter DOHC V-8 engine with Ford for the 1996–99 SHO.

Then came Volvo. From 2005 to 2010, Yamaha produced a 4.4 Litre V8 for Volvo. The B8444S engines went into the XC90 and S80, and the architecture was also adapted to a 5.0L configuration for Volvo’s foray into V8 Supercars with the S60. British sportscar maker Noble also uses a bi-turbo version of the Volvo V8 in their M600.

But the deepest, most consequential relationship was with Toyota. All performance-oriented cylinder heads on Toyota/Lexus engines were designed and/or built by Yamaha. Examples include the 1LR-GUE in the 2010–2012 Lexus LFA, the 2UR-GSE in the Lexus ISF, the 3S-GTE in the Toyota MR2 and Toyota Celica GT4/All-Trac, and the 2ZZ-GE in the 1999–2006 Toyota Celica GT-S and Lotus Elise Series 2.

And with the LFA, Yamaha didn’t just contribute components. After already shaping the character of engines like the Lexus IS-F’s naturally aspirated V8 through cylinder head work, Yamaha went a step further and designed the entire LFA engine: a 4.8-litre V10 that many consider among the finest road-car engines ever made.

It made 552 hp, with peak power at 8,700 RPM—just 300 RPM before a 9,000 RPM redline. And it was so quick to respond that it could go from idle to redline in 0.6 seconds, fast enough that the car needed a digital tachometer because an analog needle couldn’t keep up.

This was Yamaha’s OEM strategy in its purest form. Instead of spending billions to become an automaker—and getting dragged into a brutal, capital-heavy industry—it became the “silent partner” that the world’s biggest brands called when they needed something exceptional. Attractive economics, modest capital requirements, and reputational gravity that pulled in the next partnership.

At the same time, Yamaha kept building its marine business with the same playbook: adjacency plus execution. Outboard technology translated naturally from motorcycle engine development. Fiberglass know-how carried into hulls and marine components. And personal watercraft became a premium recreational category where Yamaha’s WaveRunner could go head-to-head with Sea-Doo—and win plenty of mindshare along the way.

VII. The Marine Products Empire: Yamaha's Hidden Crown Jewel

Ask most people what Yamaha Motor’s most profitable business is and you’ll hear the obvious answer: motorcycles.

They’d be wrong.

Yamaha is the global market leader in outboard motors, holding around 40% market share. In other words: on the water, Yamaha isn’t the challenger. It’s the benchmark.

And that’s why marine has quietly become Yamaha’s hidden crown jewel—a business with a commanding position, healthier margins than motorcycles, less pure price competition, and far stickier customer relationships. People switch motorcycle brands all the time. But on the water, once you trust a motor to get you home, you tend to stay loyal.

This success has been building for decades. More than sixty years after Genichi Kawakami kicked off Yamaha’s move into marine, the company had expanded its lineup to cover just about every use case, with outboards at the center. By 2022, cumulative production of Yamaha outboard motors reached 13 million units.

The product philosophy is straightforward, and relentlessly executed: reliability and durability first, delivered in lightweight, compact packages. Yamaha’s range runs from tiny 2-horsepower motors up to 450 horsepower, spanning environmentally friendly four-stroke models to Enduro variants built for punishing daily use in emerging markets.

That range matters because Yamaha’s marine business is, in a very literal sense, global. More than 90% of Yamaha outboards are exported outside Japan, sold across roughly 180 countries and territories. That means Yamaha shows up everywhere—from subsistence fishermen in Indonesia to yacht owners in the Mediterranean—creating a kind of resilience you don’t get when you’re overly dependent on one region or one customer type.

The competitive landscape also plays to Yamaha’s strengths. The outboard category is dominated by a small set of legacy leaders—Brunswick (Mercury Marine), Yamaha, Suzuki, and Honda—companies that combine scale manufacturing with proprietary ECU software and deep dealer footprints. Winning isn’t just about horsepower; it’s about service networks, parts availability, and systems that boat makers and owners trust.

Yamaha has been pushing further up that “systems” stack. Its Helm Master EX joystick system integrates features like autopilot and GPS anchor functions, turning the outboard from a piece of hardware into an ecosystem. And ecosystems create switching costs. Once an owner gets used to the controls, service routines, and the broader Yamaha setup, moving to a competitor isn’t just a purchase decision—it’s a relearning exercise.

At the same time, Yamaha has been signaling that it doesn’t intend to surrender the next era of propulsion. It broadened its electric reach by rolling out the 48V HARMO system and taking equity stakes in battery integrators. HARMO—Yamaha’s electric rim-drive outboard—is a direct response to electrification pressure in marine. And marine electrification is its own beast: boats are used intermittently, often far from reliable electrical infrastructure, and weight constraints are brutal. That makes “just electrify it” far harder on the water than on the road.

So why has marine become such a strong profit center for Yamaha? A few forces stack in its favor.

First, boating customers—especially in recreation—tend to be less price-sensitive than motorcycle buyers. An outboard is expensive, but it’s usually a fraction of the total investment in the boat and the lifestyle around it.

Second, the aftermarket is massive. Outboards require regular servicing, parts, and eventually replacement. With a global dealer network, Yamaha can earn revenue over the full life of the motor, not just at the initial sale.

Third, the market structure is simply better. Motorcycles are a global knife fight with countless brands and segments. Premium outboards have far fewer credible players.

And fourth, growth in emerging markets remains durable. In Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America, fishing is livelihood, not leisure. As incomes rise, commercial operators upgrade from unreliable equipment to proven brands—and Yamaha is often the safe choice.

Zoom out, and marine shows the real power of Yamaha’s diversification strategy: it creates natural hedges. When motorcycle demand weakens in developed markets, marine can hold up. When recreational boating softens with the economy, other Yamaha categories—often tied to practical mobility—can help absorb the shock.

In a company built on engines, precision, and trust, the water turned out to be one of the best places Yamaha ever went.

VIII. The Robotics and Industrial Pivot: Semiconductor Equipment

If Yamaha’s marine dominance is the hidden crown jewel, this next business is the plot twist: semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Yamaha Motor holds the world’s second-largest market share in chip mounters—machines used in electronics manufacturing to place tiny components onto circuit boards. It’s a serious position in a market that, from the outside, seems galaxies away from motorcycles and outboards.

But Yamaha didn’t get here by randomly “diversifying into tech.” It got here the Yamaha way: by carrying a core skill forward. Precision manufacturing moved from musical instruments, to engines, to high-speed automation—and eventually to surface mount technology.

The chip mounter market itself is an oligopoly. A handful of players—Fuji Corporation, ASM Pacific Technology, Panasonic, Yamaha Motor, and Mycronic—collectively control the majority of global share. That concentration tells you something important: this is hard. You don’t stumble into it. You either build the capability over years, or you get pushed out.

So what, exactly, is a chip mounter?

Also called a pick-and-place machine, it’s the workhorse of modern electronics assembly: it automatically grabs surface-mount devices and places them onto printed circuit boards at extreme speed and with extreme accuracy. These machines operate in a world where tiny errors become defective products, and where “fast” only matters if it’s also repeatable, reliable, and easy to keep running on a factory floor.

In January 2024, Yamaha announced the YRM10, a next-generation compact high-speed modular surface mounter. Yamaha positioned it as an economy model, but with serious performance—rated at 52,000 chips per hour—and claimed it as the fastest in its 1-Beam/1-Head class.

This isn’t just about a single machine, either. Yamaha has been pushing the idea of an integrated manufacturing stack—what it has described as a One-Stop Smart Solution—bringing together hardware, software, and process support to help customers run high-speed, high-quality surface mount production.

Then, in the early 2020s, the robotics business caught a tailwind that few industrial companies could ignore: AI. As generative AI demand surged, so did demand for semiconductor back-end process manufacturing equipment. More data centers, more compute hardware, more edge devices—all of it ultimately turns into more boards that need more components mounted, faster and more precisely.

Yamaha’s advantage here looks familiar. It’s the same playbook that made it credible as an OEM engine partner: invest in R&D, execute with manufacturing discipline, and sell globally through strong distribution. In a market where uptime and service matter as much as raw specs, those operational muscles count.

This business also captures Yamaha’s diversification philosophy in its cleanest form. The core competencies—precision mechanical engineering, high-speed motion control, and quality management—transfer shockingly well. If you can build engines and drivetrains that hold tight tolerances at scale, you can build machines that do microns all day.

And for anyone thinking about Yamaha as an investment case, the chip mounter business adds a specific kind of optionality: exposure to the long-term growth of electronics manufacturing, without taking direct bets on the most volatile parts of chipmaking itself.

IX. Key Inflection Points of the Last Two Decades (2010-2024)

The COVID-19 Boom and Bust Cycle

COVID didn’t just disrupt demand for Yamaha. It yanked it in two different directions at once.

First, personal mobility spiked. When people wanted to avoid crowded trains and buses, scooters and motorcycles suddenly looked less like hobbies and more like practical tools. At the same time, outdoor recreation exploded. Boating, powersports, and other socially distanced activities surged, giving Yamaha’s marine and recreational lines a jolt.

The whole industry responded the obvious way: build more. Capacity went up. Production ramped. Inventory followed.

Then the world reopened—and demand snapped back faster than most manufacturers could unwind their plans. The result wasn’t a gentle comedown. It was a hangover: excess inventory that lingered, and production systems that proved far better at ramping up than they were at throttling down.

That whiplash shows up clearly in Yamaha’s fiscal 2024 results. The company set a new revenue record, helped in part by improved semiconductor supply that supported the recovery of premium models. But profitability moved the other way. Operating income fell for the first time in four years, and demand tied to the pandemic-era recreation boom largely normalized in developed markets.

For the fiscal year, Yamaha reported revenue of 2,576.2 billion yen (about $17 billion), up 6.7% year over year. But net income attributable to owners of the parent fell to 108.1 billion yen, down 31.8%, and operating income declined to 181.5 billion yen, down 25.6%.

In other words: Yamaha proved it could still sell. The harder part, in the post-COVID world, was converting those sales into the kind of earnings momentum the company had enjoyed during the boom.

The 2024 Torqeedo Acquisition

In January 2024, Yamaha announced it had concluded a stock purchase agreement with Germany’s DEUTZ AG to acquire all shares of Torqeedo, the marine electric propulsion manufacturer.

The deal was framed as a milestone in Yamaha Motor’s Marine CASE Strategy 2024, aimed at achieving carbon neutrality in marine and accelerating development of an electric propulsion lineup. And Torqeedo brought real assets to the table: more than 250 patents spanning electric motors, propellers, and electrical systems, plus series production capabilities and research resources built up since the company was founded in 2005.

Yamaha put it plainly through Toshiaki Ibata, Senior Executive Officer and Chief Director of Marine Business Operations: “With the acquisition of Torqeedo, the global market leader for electric mobility on the water, we are taking the next step in our Marine CASE Strategy for 2024. Torqeedo's years of expertise provide us with expert support in driving the electrification of our marine applications to make an important contribution to a zero-emission shipping industry.”

Financially, Yamaha acquired Torqeedo for what it described as a higher double-digit million-euro amount.

Strategically, this was Yamaha placing its biggest chip yet on marine electrification. Instead of building everything from scratch—slowly, expensively, and while the market evolves underneath you—Yamaha bought a leader with an established technology base and a deep patent portfolio, effectively pulling forward its timeline.

The Formula E Entry (2024)

In March 2024, Yamaha announced a technical partnership with Lola Cars to develop and supply high-performance electric powertrains for the ABB FIA Formula E World Championship, the top tier of all-electric single-seater racing.

Yamaha began competing from Season 11 (2024–2025) as the Lola Yamaha ABT Formula E Team, alongside the German racing outfit ABT, using machines equipped with the powertrains developed and supplied through the Lola partnership.

Formula E also has a clear tech curve ahead. From Season 13 (2026–2027), the series will introduce fourth-generation GEN4 machines, with regulations shifting to higher power and significantly higher regenerative braking—changes that raise the bar for energy efficiency and powertrain performance.

If you’re looking for continuity in Yamaha’s story, it’s right here. Racing has always been Yamaha’s pressure cooker: a place to push engineering under brutal constraints, then feed what works back into product. For decades that meant two-strokes, four-strokes, and everything in between. Now, the crucible is electric.

The SPV Business Restructuring

Not every bet Yamaha placed in the last decade paid off.

In its Smart Power Vehicle business—electric wheelchairs, electrically power-assisted bicycles, and the drive units that power them—unit sales of e-bikes in Japan surpassed 2023 levels. But in Europe, the main market for Yamaha’s e-Kits, the story flipped. Sluggish demand led to prolonged inventory adjustments and falling unit sales.

The financial impact followed. Lower e-Kit volume, higher sales promotion expenses for complete Yamaha-brand models overseas, and impairment losses on fixed assets dragged the business down and contributed to lower profits.

In response, Yamaha began reviewing the business structures of both the recreational vehicle (RV) and Smart Power Vehicle (SPV) businesses—both operating at a loss—during fiscal 2024, with the explicit goal of addressing what wasn’t working and resetting for a fresh start.

It’s a familiar post-pandemic pattern: the European e-bike market looked like a clean growth runway, then demand normalized, inventory piled up, and the cost of selling rose. Yamaha’s experience here is less about a single product line and more about a broader reality of the 2020s: forecasting “the new normal” turned out to be its own kind of risk.

X. The Electrification Dilemma: Yamaha's Multi-Pathway Approach

Yamaha Motor now faces the same existential question confronting every internal combustion engine manufacturer: how do you move into an electric future without breaking the business that pays the bills today?

The company’s answer is what it calls a multi-pathway approach. Rather than declaring that everything will be battery-electric on a fixed timeline, Yamaha says it will pursue electrification alongside continued work on combustion and hybrids, with the long-term environmental goal of achieving carbon neutrality across all product lifecycles by 2050. The YE-01 project sits inside that plan as a concrete step toward electric motorcycles.

Under this broader strategy, Yamaha has also set emissions-reduction targets for its value chain: reducing Scope 3 emissions to 24% by 2030 and 38% by 2035, on the way to a 90% reduction by 2050.

What’s striking is how openly Yamaha acknowledges that the end-state won’t look the same across its product lines. Battery-electric power may win in passenger cars, but Yamaha lives in categories where the tradeoffs are harsher. Motorcycles are brutally weight-sensitive. Marine applications can be range- and infrastructure-constrained. Industrial equipment has its own reality, defined by duty cycles and uptime. The same chemistry and charging model that works for a commuter car doesn’t automatically work for an outboard or a small-displacement sportbike.

So “multi-pathway” doesn’t just mean different battery packs. It also includes work on what Yamaha describes as sustainable fuels to reduce CO2 emissions—another lever it can pull where full electrification isn’t yet practical.

On the product and technology side, Yamaha has been widening its options. Its efforts around compact personal mobility have included racing the TY-E electric trials bike in major international competitions, joining HySE (the joint Hydrogen Small Mobility & Engine Technology initiative with other Japanese motorcycle manufacturers), and helping establish a battery sharing service company.

And then there’s the attention-grabbing proof point from April 2021: a 350 kW (469 hp) electric drivetrain.

The headline number is impressive, but the engineering choice is the story. Instead of developing each piece of an EV powertrain in isolation, Yamaha integrated the motor, gearbox, and electronic speed controller into a single unit. The goal was output density—packing a lot of power into a compact, manufacturable assembly—and Yamaha described the result as reaching the industry’s highest class in output density.

To underline what that enables, Yamaha even demonstrated a skateboard-style chassis concept designed to accept four of these motors—one per wheel—for all-wheel drive and massive total output. It’s not a production car announcement. It’s Yamaha making a point: if the market wants extreme power in tight packaging, Yamaha can supply it.

That matters strategically because it echoes Yamaha’s old winning move in automotive: the OEM strategy. Just as it partnered with Ford, Volvo, and Toyota on high-performance engines and components rather than trying to become a full-fledged automaker, Yamaha is positioning itself to provide best-in-class electric powertrains to manufacturers around the world—without taking on the full cost and risk of building complete vehicles.

Put it all together and you get a deliberately multi-pronged electrification posture. Yamaha participates in battery-swapping consortiums. It has demonstrated it can build high-output electric motors in-house. And it has made significant investments in other electric two-wheeler manufacturers.

The theme here is strategic optionality. Yamaha isn’t betting everything on a single prophecy about how electrification will unfold. If hydrogen becomes viable in certain segments, it wants to be ready. If battery swapping becomes the norm for two-wheelers, it wants a seat at the table writing the standards. And if the future rewards extreme power density, Yamaha wants to be the supplier that’s already there.

XI. Competitive Position and Strategic Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate

In Yamaha’s core businesses, the barriers are still high. To compete seriously in motorcycles or outboards, you need massive capital, world-class manufacturing, and a distribution and service footprint that takes decades to build. That said, electrification shifts the terrain. Electric powertrains are mechanically simpler than internal combustion, which lowers some technical hurdles and has opened the door for new entrants, including companies like Stark Future in electric motorcycles.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Moderate

Yamaha gets leverage from scale, but the bigger advantage is what it keeps in-house. With deep vertical integration—casting, machining, assembly—the company is less exposed to supplier pricing and disruptions on the components that matter most. It doesn’t eliminate supplier risk, but it reduces dependence where competitors might be forced to outsource.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate

In developed markets, Yamaha sells into crowded categories. A motorcycle buyer can cross-shop Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki, and others. Marine customers have strong alternatives too, including Brunswick’s Mercury Marine. In many emerging markets, though, Yamaha’s brand and dealer presence are stronger relative to the field, which reduces buyer power somewhat—especially when reliability and service access are part of the purchase decision, not just sticker price.

Threat of Substitutes: Increasing

For motorcycles, the substitution pressure is real and rising: electric vehicles, improved public transit, and ride-sharing all chip away at the rationale for personal two-wheeler ownership in certain markets. Marine is different. Boats are often recreational, and while buyers can choose different forms of leisure, there isn’t a clean “replacement” in the way a commuter might replace a scooter with public transit.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense

Yamaha’s own history proves the point. The Honda-Yamaha War wasn’t an anomaly—it was an extreme example of what happens in a mature, high-stakes manufacturing market when competitors are willing to fight on product cadence, dealer support, marketing, and price. That rivalry remains a defining feature of motorcycles and marine, and Yamaha’s industrial businesses face their own version of it: relentless performance improvement and service expectations, with little patience for downtime.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies

Yamaha benefits from scale across multiple product lines, spreading fixed costs and supporting competitive pricing.

Network Effects

There aren’t classic, viral network effects here. But Yamaha’s dealer and service footprint functions like an ecosystem advantage: it’s hard for smaller competitors to match, and it can influence purchasing when uptime and support are critical.

Counter-Positioning

Yamaha’s diversification—motorcycles, marine, industrial equipment—sets it apart from more narrowly focused competitors. That breadth provides resilience, especially when one market hits a down cycle.

Switching Costs

Switching costs are strongest in marine. Dealer relationships, parts availability, and familiarity with integrated control systems can keep customers in the fold. In motorcycles, switching is easier and more common.

Branding

Yamaha’s brand carries real weight globally, particularly where performance and motorsports credibility matter. Racing success doesn’t just build trophies; it builds preference.

Cornered Resource

Decades of engine and manufacturing know-how—reflected in patents and process knowledge—create a library of hard-to-replicate intellectual property and experience.

Process Power

This is Yamaha’s signature. The company repeatedly carries precision manufacturing capability from one category to the next—musical instruments to motorcycles, motorcycles to marine, and then into robotics—turning “how we build” into a competitive edge.

Comparison with Key Competitors

Honda Motor

Yamaha’s longtime rival is larger and more diversified, with automobiles and other businesses that generate cash flow Yamaha can’t match. That financial depth gives Honda strategic flexibility, especially in downturns. At the same time, Yamaha’s story has often been about focus and excellence inside mobility categories where Honda’s attention is spread across a broader empire.

Kawasaki Heavy Industries

Kawasaki’s diversification—spanning aerospace, rolling stock, and industrial equipment—looks more like a sibling strategy to Yamaha than a pure motorcycle rivalry. In bikes, Kawasaki competes strongly in premium segments like sport and adventure, where brand identity and performance matter.

Brunswick Corporation (Mercury Marine)

In outboards, Mercury is Yamaha’s primary rival. Brunswick’s vertical integration, including boat manufacturing, gives it advantages Yamaha doesn’t have. Yamaha, however, has built formidable global distribution—especially in emerging markets—where service networks and reliability reputations can outweigh corporate structure.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For fundamental investors tracking Yamaha Motor’s trajectory, three KPIs are especially worth watching:

-

Marine Products operating margin

This is Yamaha’s highest-quality earnings stream. If margins compress, it can be an early sign of tougher competition, discounting, or weakening demand. -

Emerging-market motorcycle unit volume

Long-term earnings power is driven by markets like Brazil, India, and Indonesia. Unit trends there often tell you more about future health than headlines in developed markets. -

Robotics business revenue growth

This segment is a useful proxy for cycles in electronics manufacturing and broader semiconductor capital spending—and a read on Yamaha’s position in chip mounting equipment.

XII. Current Financial Position and Outlook

After the post-COVID whiplash, Yamaha’s most recent results show a company that’s still growing—just with more friction than during the boom.

For the year, revenue came in at 2.576 trillion yen, up 6.7% from the prior fiscal year. The biggest driver was Land Mobility: Yamaha sold more units and captured better pricing on motorcycles in key growth markets like Brazil and India.

Looking ahead to the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, Yamaha expects that emerging-market motorcycle demand will remain robust, and that outboard motor demand in Marine Products will gradually recover. The company is also explicit about what could bite: higher costs for aluminum and other raw materials, plus continued increases in labor and energy.

On its own forecast for fiscal 2025, Yamaha is guiding to net income of 140.0 billion yen and operating income of 230.0 billion yen, with revenue expected to reach 2.70 trillion yen. Put simply, management is signaling a return to profit growth—suggesting the worst of the post-pandemic inventory correction is likely in the rearview mirror.

Still, there are real risks worth watching:

Geopolitical Risks: Yamaha expects fiscal 2025 to remain uncertain, citing the situation in the Middle East and other geopolitical risks, the sluggish Chinese economy, and the downstream effects of global economic policy.

Currency Exposure: With more than 90% of outboard motors exported, plus substantial operations in Brazil, India, and Indonesia, Yamaha carries meaningful currency translation risk.

Electrification Transition Costs: Developing electric products across multiple categories will require investment that can pressure near-term margins.

SPV Business Restructuring: The e-bike and electric wheelchair business still needs operational improvements to return to profitability.

Over this same period, Yamaha also rolled out a new Medium-Term Management Plan (2025–2027) that tightens how it thinks about the portfolio. It reorganizes the company into “Core Businesses,” “Strategic Businesses,” and “New Businesses.”

The message underneath the labels is straightforward: not every business gets the same right to capital. Core businesses—motorcycles and marine—are the cash generators. Strategic businesses—robotics and SPV—are where Yamaha wants to invest for long-term positioning. And new businesses are, by design, the set of bets that provide optionality if the next wave breaks in a different direction.

XIII. Conclusion: The Diversification Masterclass Continues

Seven decades after Genichi Kawakami looked at a set of idle propeller machines and decided to build motorcycles, Yamaha Motor has become one of the most unusual—and most instructive—manufacturing stories in the world. The company that nearly broke itself in the Honda-Yamaha War absorbed the message the hard way: if you’re going to compete against giants, you can’t let one product line be your only lifeline.

Today, Yamaha earns money in places that rarely show up in the same sentence: fishermen in Indonesia choosing outboards because they need an engine that starts every day; electronics manufacturers buying chip mounters because minutes of downtime cost a fortune; recreational riders and boaters in the U.S. paying for performance and trust; commuters in São Paulo relying on affordable two-wheel mobility. Those end markets don’t move in lockstep, and that’s the point. The portfolio is a shock absorber that many pure-play competitors simply don’t have.

Electrification is the next great stress test—and Yamaha is approaching it like a company that remembers what overconfidence costs. Its multi-pathway strategy isn’t indecision; it’s hedging based on where Yamaha actually lives: weight-sensitive motorcycles, infrastructure-constrained marine, uptime-driven industrial equipment. In that context, the moves from 2024 line up. The Torqeedo acquisition pulls electric marine capability forward. The Formula E partnership puts Yamaha back where it’s always learned fastest: racing under constraints. And the 350 kW motor concept is a statement that Yamaha can supply high-density electric power when customers demand it.

Through all of it, Yamaha’s north star remains Kando—the idea that engineering only counts when it creates a visceral response. That could be a sportbike carving a mountain road, a boat crossing open water with absolute confidence, or a factory-floor robot placing components with quiet, relentless precision. Different products, same intent: turn manufacturing excellence into something people feel.

As an investment case, Yamaha offers a rare mix: emerging-market growth in motorcycles, developed-market strength in marine, and real technology optionality in robotics and electrified powertrains—backed by decades of brand equity earned the hard way. The risks are real, too. Honda is still Honda. Chinese manufacturers keep climbing the quality curve. New EV players keep attacking from angles that didn’t exist a decade ago.

But the through-line of Yamaha’s story is survival through adaptation. It outlasted the 1950s shakeout that wiped out hundreds of motorcycle makers. It lived through the most infamous corporate war in Japanese motorcycling. And it rebuilt itself by learning how to diversify without losing its core identity.

The company that began with pianos and propellers now sits across the global economy—still chasing Kando, still finding new places where precision and engines can win, from tuning forks to two-wheelers and far beyond.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music