Subaru Corporation: From Fighter Planes to Crossover Kings

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

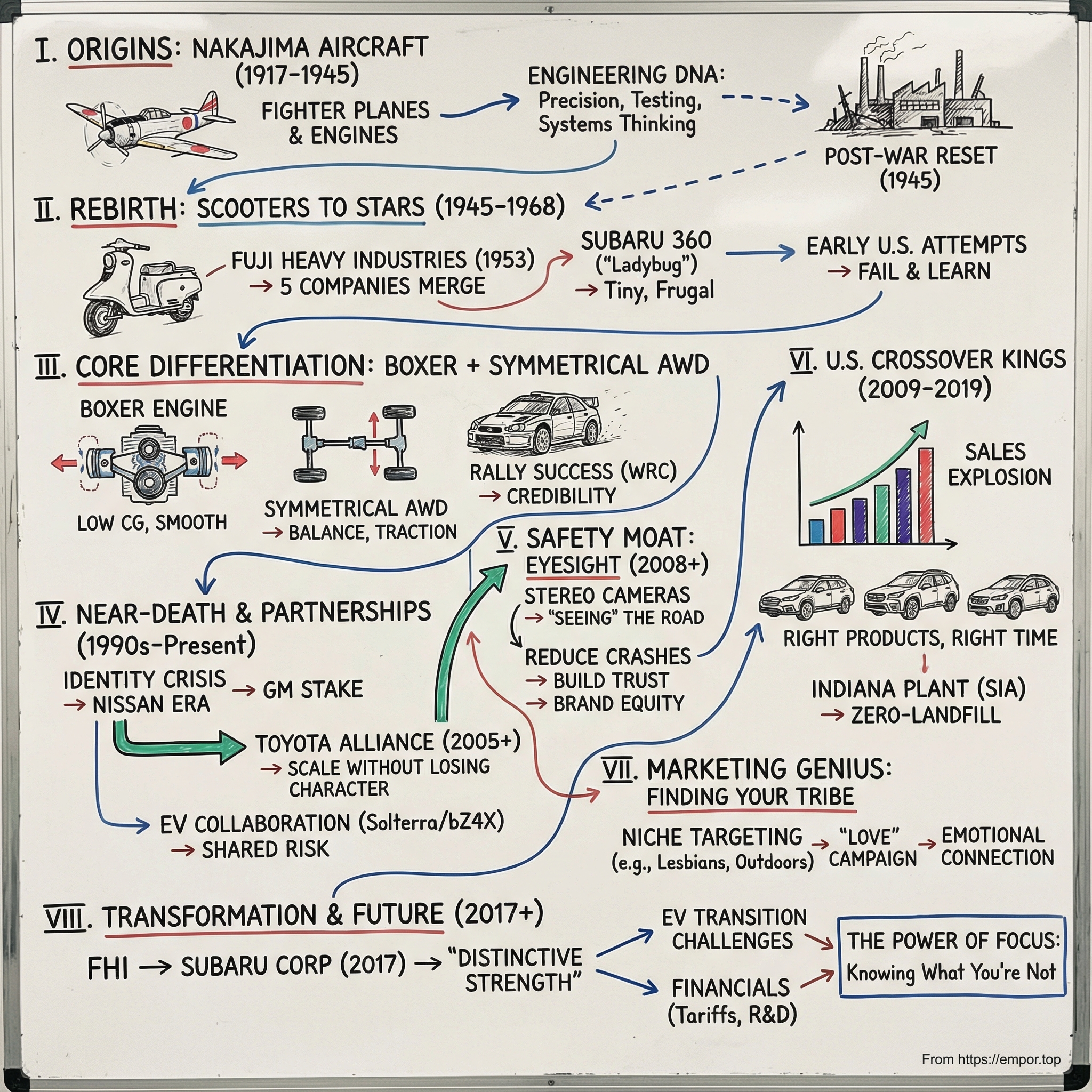

Picture this: it’s 1945. The smokestacks of Japan’s most formidable aircraft manufacturing empire have gone cold. Nakajima Aircraft—the company whose engines powered some of Japan’s most feared warplanes—has been bombed, broken up, and effectively outlawed by the postwar occupation. The factories are still there, but the mission is gone.

Fast-forward eight decades. That same lineage now shows up as a blue six-star badge on crossovers parked at REI, at ski resorts, and outside farmers’ markets from Portland to Burlington. The company that once turned out tens of thousands of aircraft engines becomes, improbably, one of America’s defining car brands of the 2010s.

How does a company that once built fighter planes become America’s favorite crossover brand—and do it by deliberately staying small?

Today’s Subaru Corporation is a Japanese multinational best known for its cars. It’s headquartered in Tokyo, started life as Fuji Heavy Industries, and in 2017 made it official: the company renamed itself Subaru Corporation, matching the corporate name to the brand on the hood.

But the plot twist isn’t the name change. It’s the strategy. Subaru’s story is about focus—almost stubborn focus—in an industry that rewards scale. While Toyota and Honda chased global dominance, Subaru carved out a narrow lane and built it into a fortress: all-weather capability, safety, and a brand vibe so distinct that customers didn’t just buy the cars, they joined the tribe. In Japan they even have a name for them: “Subarists.”

And the results are still showing up in the numbers. Subaru of America reported 667,725 vehicle sales in 2024, up 5.6% from 2023, with December marking the 29th straight month of U.S. increases. But none of this was preordained. Subaru had a real brush with collapse in the 1990s, needed a Nissan-led rescue, later found an unexpectedly aligned partner in Toyota, and then pulled off one of the most studied marketing plays in modern automotive history by leaning into underserved customers instead of trying to please everyone.

So this episode is about a few big ideas: what focus looks like in a commodity industry, why being the junior partner to a giant can be a superpower, how an aviation engineering culture turns into a road-car advantage, and—most importantly—how you can win by choosing not to compete everywhere.

The question we’re answering: how did a company that nearly collapsed in the 1990s become the fastest-growing mainstream auto brand in America for a decade—and what does that reveal about where the auto industry is headed next?

II. Origins: Nakajima Aircraft & The DNA of Engineering Excellence (1917–1945)

Before Subaru ever existed as a name or a badge, there was Chikuhei Nakajima: a naval engineer with an obsession for flight, and a conviction that Japan should build its own airplanes.

In 1918, Nakajima partnered with Seibei Kawanishi, a textile manufacturer, to found Nihon Hikoki (Nippon Aircraft). It didn’t last. The two split in 1919, and Nakajima bought out the factory—helped along by tacit support from the Imperial Japanese Army. The early work was scrappy: prototypes, iterations, lessons learned the hard way. But the feedback loop was fast, and the timing was perfect. By 1920, the Army had taken notice. Contracts started arriving, and then they started getting bigger.

From the 1917 founding roots of Nakajima’s aircraft effort through the 1930s and into World War II, Nakajima Aircraft Company ballooned into a massive munitions manufacturer—one of Japan’s two dominant aircraft builders, alongside Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

Here’s the detail that matters for Subaru’s later story: Mitsubishi was diversified. Shipbuilding, heavy machinery, lots of industrial legs to stand on. Nakajima wasn’t. It stayed concentrated on aircraft.

That focus became both a superpower and a fatal vulnerability.

In wartime, it was a superpower. Nakajima produced engines for both Army and Navy aircraft, including the Sakae engine used in the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, as well as aircraft of its own like the Ki-43 “Oscar.” The Oscar became a prolific fighter, flown by many of the Japanese Army Air Force’s top aces and remaining in use through the end of the war.

And beneath the production numbers was something more durable: a way of thinking. Nakajima pushed an engineering culture built around tight tolerances, relentless testing, and systems integration. They developed airframes and powerplants in-house, which forced engineers to think across the entire machine—how thousands of parts behaved together, under stress, where failure wasn’t a warranty issue, it was life and death.

Even late in the war, Nakajima was still pushing the edge. The Nakajima Kikka became the only World War II Japanese jet aircraft capable of taking off under its own power—part of a frantic effort to respond to the jet age the Germans were already demonstrating with aircraft like the Messerschmitt Me 262.

Then Japan surrendered, and the bottom fell out. Under the Allied occupation, aircraft production and research were prohibited. Not throttled back—abolished. For a company built almost entirely around planes and plane engines, it was an existential shutdown.

But the factories and the people didn’t vanish. The engineering talent stayed in Japan, and many of the country’s leading aeronautical minds—engineers like Ryoichi Nakagawa—would go on to help reshape Japanese manufacturing in the decades that followed.

Nakajima Aircraft itself wouldn’t survive in its wartime form. The story would move through postwar reorganization and, eventually, a 1953 reunion that formed Fuji Heavy Industries—first known for Fuji Rabbit scooters, and then for something far more consequential: Subaru automobiles.

And that’s the through-line. Subaru’s later identity—engineering-first, obsessively mechanical, unusually serious about safety and stability—didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was inherited. The DNA was forged in an aircraft company that had one job: build machines that performed under extreme conditions, every single time.

III. Post-War Rebirth: From Scooters to the Stars (1945–1968)

When Japan surrendered, the industrial map of the country was basically erased. Factories were bombed out, cities were in ruins, and the occupation authorities didn’t just discourage aircraft production—they banned it outright. For Nakajima Aircraft, that wasn’t a downturn. It was a hard stop. The company had to find a new reason to exist, fast.

So it did the most practical thing imaginable: it repurposed what it had. Nakajima reorganized as Fuji Sangyo Co., Ltd., and in 1946 began building the Fuji Rabbit motor scooter, using leftover aircraft parts. It was the kind of pivot that only looks obvious in hindsight—take aerospace-grade materials and precision manufacturing know-how, and turn them into something a rebuilding nation actually needed: cheap, reliable mobility.

Then came another reset. In 1950, anti-zaibatsu policies broke up many of Japan’s large industrial groups to prevent the old wartime power structures from re-forming. Fuji Sangyo was split into twelve smaller companies, scattering the Nakajima lineage across the corporate landscape.

The comeback was a reunion, and it took years. Between 1953 and 1955, five of those companies—plus a newly formed one—stitched themselves back together as Fuji Heavy Industries. The pieces were practical and complementary: Fuji Kogyo (scooters), Fuji Jidosha (coachbuilding), Omiya Fuji Kogyo (engines), Utsunomiya Sharyo (chassis), and the Tokyo Fuji Sangyo trading company.

And then came the moment where the company stopped being just a postwar merger and became a story.

Fuji Heavy needed a name for its automotive brand. Executive Kenji Kita chose one he said he’d been “cherishing in his heart”: Subaru. It’s the Japanese name for the Pleiades star cluster—often called the “Seven Sisters.” Tradition says one sister is invisible to the naked eye, which is why Subaru’s badge shows six stars. It also nodded to what had just happened inside the company: separate firms aligning into one constellation.

In other words, the logo wasn’t decoration. It was the strategy in miniature—unity, identity, and a fresh start built on old engineering bones.

The first car to wear the name was the Subaru 1500 in 1954. It should have been the beginning of a new chapter, but reality intervened: supply problems meant only twenty were built. So Subaru regrouped and went smaller—literally. In 1958 it landed on the product that fit Japan’s moment: the Subaru 360, a kei car engineered around the country’s minimal-class regulations. Tiny, frugal, and thoughtfully built, it was exactly what a cash-strapped, rapidly modernizing Japan could actually buy.

Then, in 1968, Subaru tried the hardest thing it could have done: America.

Bringing the Subaru 360 into a market of big engines, big highways, and big expectations was a gamble. The car’s size and performance clashed with American road conditions and tastes, and the skepticism was loud—Consumer Reports even labeled it “not acceptable.”

But the important part wasn’t that the first attempt was rough. It’s that Subaru didn’t walk away. It treated the failure like data. And beneath that persistence was a realization that would eventually become Subaru’s defining advantage: it didn’t need to beat Ford and GM at their own game. It needed to find the customers who wanted something different—and then build obsessively for them.

IV. The Core Differentiation: Boxer Engines & Symmetrical AWD

Subaru’s modern identity can be reduced to two phrases you’ll hear repeated with near-religious devotion in any enthusiast corner of the internet: “boxer engine” and “symmetrical AWD.” They aren’t just slogans. They’re the company’s two big, stubborn engineering bets—and they rhyme perfectly with an organization that started life designing machines for stability, balance, and performance under stress.

Start with the boxer.

A boxer engine, also called a horizontally opposed engine, lays its cylinders flat. The pistons move side-to-side, firing in opposing pairs off a central crankshaft—like two fists punching outward in rhythm. That layout gives Subaru a low-profile engine with less vibration and, crucially, a lower center of gravity.

Why would a company with aviation roots fall in love with this design for road cars? Because the physics are compelling. A lower center of gravity helps a car feel planted and reduces rollover risk. The opposing motion naturally cancels out a lot of vibration, so the engine runs smoother. And the flat shape lets engineers mount the engine lower in the chassis, which can free up space for stronger crash structures.

But this isn’t a free lunch. From an investor’s perspective, the boxer is both moat and constraint. The moat is specialization: today, only Subaru and Porsche still manufacture boxer engines for cars, which creates hard-won expertise that’s not easy to copy. The constraint is manufacturing reality: boxer engines require dedicated tooling and unique components, and that can limit flexibility and scale compared to the more common inline and V-style engines that the rest of the industry optimizes around.

Then there’s the other half of the Subaru “why”: all-wheel drive.

Subaru earned its following the honest way—by being the brand that starts on cold mornings, climbs slippery driveways, and makes ugly weather feel like a non-event. That’s why its cars over-index in places like the Pacific Northwest and New England. And it’s not just because Subaru offers AWD. It’s because Subaru committed to it.

While most competitors treated all-wheel drive as a pricey add-on—an option you had to request and pay extra for—Subaru made it a default across almost the entire lineup. Every Subaru, with the exception of the rear-wheel-drive BRZ sports coupe, comes standard with AWD. That decision isn’t a feature checklist item. It’s a brand promise, and it shapes what customers expect a Subaru to be.

The “symmetrical” part matters, too. Subaru’s drivetrain is laid out in a straight, balanced line: engine, transmission, and driveshaft aligned down the center, feeding front and rear differentials. That symmetry helps weight distribution and makes the car’s behavior more predictable—especially on snow, rain, gravel, and everything in between.

And then Subaru took that whole philosophy into the harshest lab environment imaginable: rally racing.

Beginning in 1989, Subaru partnered with British motorsport outfit Prodrive, which ran the Subaru World Rally Team through 2008. Subaru didn’t just show up—it became a force. The team won the manufacturers’ championship three times in the mid-1990s, and drivers brought home titles in 1995, 2001, and 2003. Along the way, the Impreza racked up 46 rally wins.

This era produced icons: Colin McRae, Richard Burns, Petter Solberg, Carlos Sainz. The blue-and-yellow livery became instantly recognizable, and the WRX’s distinctive sound turned into a cultural marker for an entire generation of enthusiasts. More importantly, the rally program wasn’t just a branding exercise. It was proof. Subaru used it to showcase symmetrical all-wheel drive under the most punishing conditions, then fed that credibility back into its road cars. Subaru has even credited its World Rally Championship success with boosting sales, especially for the Impreza, and with popularizing its AWD story.

Put it together and you get Subaru’s core strategic posture. The boxer engine plus standard AWD is a classic example of counter-positioning in Hamilton Helmer’s terms: rivals could imitate it in theory, but doing so would mean undoing decades of architecture choices, factory investments, and product planning. The cost of copying is so high that Subaru gets to keep the lane—though the same choices that make Subaru hard to imitate also make it harder for Subaru to chase pure scale.

V. The Near-Death Experience & Nissan Era (Late 1980s–2005)

By the late 1980s, Fuji Heavy Industries was in trouble—real trouble. It had become a meaningful supplier of military, aerospace, and railroad equipment in Japan, but the business still lived and died by automobiles. Cars made up about 80% of sales. And suddenly, the car business was sliding.

In 1989, sales dropped 15% to about $4.3 billion. In 1990, the company posted losses of more than $500 million. For a company Subaru’s size, that wasn’t a bad year. It was an existential threat.

What makes this moment so important is that Subaru hadn’t yet found the playbook that would later define it. The company was stuck in a brutal middle: too small to go toe-to-toe with Toyota and Honda on volume and cost, but not yet focused enough to charge premium prices or own a sharp niche. The boxer-and-AWD story was real, but it wasn’t yet the organizing principle for the whole company.

The Industrial Bank of Japan—Fuji Heavy’s main lender—basically forced a reset. It asked Nissan, which owned a 4.2% stake in Fuji Heavy Industries, to step in. Nissan responded by sending Isamu Kawai, the president of Nissan Diesel Motor Co., to take charge.

This “Nissan era” brought discipline, but it also exposed how unclear Subaru’s identity had become. In 1991, Fuji Heavy began contract-manufacturing Nissan Pulsar sedans and hatchbacks. On paper, it was sensible: fill excess factory capacity, bring in revenue, stabilize operations. But strategically, it was a tell. Subaru didn’t just need better execution—it needed to decide what it was.

That question hung over the entire 1990s: was Subaru a quirky enthusiast brand, or was it supposed to be a mainstream player? Internally, different factions pushed different answers. Some wanted to compete head-on with larger automakers by building more conventional cars. Others argued Subaru should lean harder into what made it different. The result was predictable: mixed signals, inconsistent marketing, and volatile performance.

Then General Motors entered the picture, picking up Nissan’s stake when Nissan divested during its own restructuring. But GM didn’t arrive with a thesis about Subaru. It wasn’t an operating partnership designed to sharpen the brand or unlock a shared platform strategy. It was largely financial—and it didn’t give Subaru the clarity it was missing.

In 1999, Nissan sold its holdings to General Motors, and GM later liquidated its stake in Fuji Heavy Industries in 2005.

For Subaru, that period was a holding pattern. The company had loyal customers—especially in the United States, which was increasingly becoming the most important market—but it struggled to break out. U.S. sales hovered around 200,000 units a year, stuck at “cult favorite” scale.

Subaru didn’t need a savior. It needed the right kind of partner: one that could offer scale where scale mattered, without sanding down the edges that made Subaru, Subaru. And that partner was about to show up.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Toyota Alliance (2005–Present)

When GM decided to exit its Subaru investment in 2005, Toyota saw what everyone else had missed: here was a small automaker with a devoted customer base, real engineering differentiation, and factories that could be more valuable with the right partner. Toyota bought an initial 8.7% stake—and in doing so, it didn’t just buy shares. It bought an option on Subaru’s future.

What’s remarkable is how Toyota chose to use that option.

In an industry where “partnership” often means slow-motion absorption, Toyota took the opposite tack. It made a point of preserving Subaru’s independence and identity. The line that captures the philosophy, repeated as company lore, came from then–Toyota CEO Shoichiro Toyoda: “Do not be like Toyota. You lose your competitive advantage if you lose your character.”

That wasn’t politeness. It was strategy.

Toyota already owned the mainstream. It didn’t need Subaru to become a smaller Camry-and-RAV4 machine. What Toyota did want were the things Subaru did unusually well: all-wheel drive know-how, boxer-engine expertise, and the safety and driver-assistance capabilities Subaru was building.

A few years later, Toyota increased its position again, bringing its stake to around 16.5%. And with that deeper tie, the two companies decided to do something that would make the partnership legible to the public: co-develop a compact sports car.

The result was the BRZ/86 twins. Same bones, different personalities. Subaru brought the boxer engine and its chassis instincts; Toyota brought its product-planning muscle and global reach. Launched in 2012, the Toyota version was also sold as the Scion FR-S in the U.S., while Subaru kept the BRZ badge. The formula was simple: a lightweight, rear-wheel-drive coupe built to be fun, not flashy.

More importantly, the project proved the relationship could actually work. The companies shared development costs, each got a credible enthusiast halo car, and neither had to pretend it invented the other’s strengths. When the first generation ended in 2020, a second arrived quickly in 2021. Subaru kept “BRZ.” Toyota’s “86” evolved into the GR86 under Gazoo Racing.

Then came the moment the alliance shifted from “helpful” to “structural.”

In September 2019, Toyota raised its stake to about 20%. By March 2024, Toyota’s ownership sat at just over 20%—a meaningful block with real voting influence, but not outright control. And despite that influence, Toyota still wasn’t treating Subaru like a brand to be folded in and standardized. The whole point was that Subaru should keep being Subaru.

The reason is straightforward: scale matters more than ever, and Subaru is intentionally not a scale player. Electrification, software, batteries, new manufacturing tooling—these are capital-intensive bets that can crush a smaller automaker if it tries to do everything alone. Toyota can spread those costs across millions of vehicles. Subaru can’t.

That’s why the EV collaboration became the alliance’s center of gravity. In May 2022, Toyota launched the bZ4X and Subaru launched the Solterra—siblings built on Toyota’s e-TNGA platform, each with its own branding and positioning. Same underlying architecture; different promise on the hood.

Subaru CEO Atsushi Osaki put it bluntly: “There is a huge risk for us to go it alone in this field.” For Subaru, the Toyota partnership wasn’t about winning EVs faster than Tesla. It was about staying in the game without overextending itself into another near-death experience.

And the collaboration has continued. Subaru and Toyota have partnered to co-develop three all-electric crossovers planned for release by 2026, explicitly sharing risk and investment in a market that still demands massive spend—even as consumer demand has shown signs of cooling.

The relationship also goes beyond EVs. Subaru, Toyota, and Mazda have committed to developing new engines designed for electrification and carbon neutrality, with each company focusing on optimizing its own “signature” engine architecture while integrating better with motors, batteries, and other electric drive units. It’s a hedge: a way to keep improving combustion-based platforms while the industry sorts out what the transition timeline really looks like—and to do it without each company paying the full R&D bill alone.

For investors, the Toyota alliance is Subaru’s great stabilizer and its great dependency. The upside is obvious: access to components, processes, and technology Subaru would struggle to fund on its own. The downside is just as real: Subaru’s future becomes increasingly entangled with a partner whose incentives won’t always match—and whose stake could grow if Toyota ever decides the “option” is worth exercising more aggressively.

Either way, this alliance is one of the defining strategic choices in modern Subaru history. It gave Subaru something it never had in the 1990s: scale on demand, without surrendering its identity.

VII. Inflection Point #2: EyeSight & The Safety Moat (1999–Present)

Subaru’s safety story didn’t start with a splashy product launch or a Super Bowl ad. It started quietly, in 1999, when Subaru put a system called Active Driving Assist (ADA) into the Legacy Lancaster. At the time, almost nobody cared. The tech was early, the use case was narrow, and the industry’s attention was elsewhere. But inside Subaru, it was the first real step toward turning safety into a core competency—not a compliance box.

That bet became visible to the world in 2008, when Subaru launched EyeSight. The big idea was deceptively simple: instead of building the system around radar, Subaru used stereo cameras—two cameras, mounted like a pair of human eyes—so the car could judge depth and distance the way people do. In practice, that meant EyeSight could better “understand” what was happening ahead: how close objects were, how quickly things were changing, and when a routine moment was about to become an accident.

It was classic Subaru: aerospace-adjacent thinking applied to road cars. Not just detection, but interpretation. Not just reacting to a crash, but trying to avoid it.

Two years later, Subaru rolled out Advanced EyeSight (version 2) in 2010. It wasn’t a new philosophy so much as a sharper tool: improved Pre-Collision Braking Control that could stop the vehicle when it detected a frontal collision risk, plus upgraded all-speed adaptive cruise control that could bring the car to a stop if traffic ahead slowed or stopped. These weren’t gimmicks. They were features designed for real-world stress: stop-and-go commuting, sudden slowdowns, distracted drivers around you. The upgrade earned Subaru the 2010/2011 Japan Automotive Hall of Fame Car Technology of the Year award.

And then the data started to land.

IIHS studies found that EyeSight reduced rear-end crashes with injuries by up to 85% and reduced pedestrian-related injuries by 35%. That kind of improvement isn’t “nice to have.” It changes what customers believe a Subaru is supposed to do.

Adoption followed. EyeSight-equipped vehicles now account for about 91% of Subaru’s global sales. In other words, this didn’t remain an option package for cautious buyers. It became the default expectation.

EyeSight also forced the rest of the industry to move. Its effectiveness pushed competitors to accelerate their own advanced driver assistance systems, and Subaru’s early start helped it build credibility—and momentum—as ADAS went mainstream.

The awards piled on, too. Since 2013, Subaru has accumulated a total of 71 IIHS TOP SAFETY PICK+ awards, more than any other brand. And in more recent testing, IIHS evaluated 10 small SUVs including the 2024 Subaru Forester; the Forester was the only one to earn the highest possible rating of “Good.”

This is where EyeSight becomes more than a feature. It becomes a moat.

For Subaru, safety turned into a flywheel: a reputation for safety builds trust; trust supports pricing power; pricing power funds more R&D; better technology improves real-world outcomes; those outcomes reinforce the reputation. It’s hard to break because it’s not just marketing—it’s measurable performance that customers and third parties can validate.

And that’s the strategic punchline. Most automakers treat safety as table stakes. Subaru managed to turn it into brand equity. Customers don’t just want Subaru’s safety systems—they expect them. That expectation is a burden, because Subaru has to keep investing to stay ahead. But it’s also a weapon: it deepens loyalty, supports premium pricing, and makes the decision to switch away feel like giving something up.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The U.S. Crossover Strategy (2009–2019)

If EyeSight became Subaru’s safety moat, the U.S. crossover wave became its growth engine.

Between 2009 and 2019, Subaru pulled off one of the most unlikely runs in modern American auto history: it went from a niche, outdoorsy cult favorite to a legitimate mainstream contender. In 2010, Subaru sold 263,000 vehicles in the United States. By 2019, it was at 700,000. And it didn’t get there with one blockbuster year—it broke its annual U.S. sales record every single year across the decade.

So what happened?

Three things lined up at exactly the right time: the right products, the right positioning, and the right timing.

First, product. Subaru leaned into crossovers and SUVs just as Americans were walking away from sedans. The lineup increasingly became a greatest-hits album of vehicles people actually wanted to buy: Outback, Forester, and then a new star. In 2013, Subaru launched the Crosstrek—an Impreza-based, smaller crossover that hit a sweet spot for buyers who wanted practicality and traction without the bulk. It became a volume pillar. In 2024, the Crosstrek, Forester, and Outback were Subaru’s top-selling models, and the Crosstrek led the pack with 181,811 sales, its best year ever.

And yes, Subaru still left a couple of hooks for enthusiasts: the BRZ rear-wheel-drive sports car, co-developed with Toyota (sold as the Toyota 86, and previously as the Scion FR-S), plus the WRX performance sedan. But the core of the business was clear. Subaru wasn’t trying to be everything. It was trying to be the best at a very specific kind of everyday vehicle.

Second, positioning. Subaru didn’t sell the American dream. It sold a practical promise: standard all-wheel-drive confidence, wrapped in cars that were safe, durable, and ready for real life. It focused heavily on its AWD unique selling point and built a tight lineup around it—especially the Outback, Forester, and Crosstrek.

Third, timing. Subaru’s “weird” advantages became mainstream advantages. All-wheel drive went from niche to normal as consumers prioritized all-weather confidence, and Subaru’s safety reputation—supercharged by EyeSight and validated by strong third-party ratings—made the purchase decision feel less like a preference and more like a responsible choice.

There were trade-offs. To keep doubling down on where it could win, Subaru effectively let some traditional passenger-car momentum go. Its sedans—the Legacy and Impreza—declined as the market shifted. Even the Legacy, Subaru’s longest-running model line, ultimately faced discontinuation, reflecting the broader move from passenger cars to SUVs and crossovers and Subaru’s transition toward electrified and fully electric vehicles. Subaru made the choice, took the hit, and kept its resources trained on the segments that were working.

Subaru’s momentum in the U.S. didn’t stop with that decade, either. From January to December 2023, Subaru of America sold 632,086 vehicles, a 13.6% increase over 2022, and December 2023 marked 17 consecutive months of U.S. sales growth.

But growth like that doesn’t happen on imports alone. Subaru needed American manufacturing capacity.

That’s where Subaru of Indiana Automotive—SIA—became a hidden pillar of the story. Today, the plant is a wholly owned subsidiary of Subaru Corporation, producing the Ascent, Crosstrek, Legacy, and Outback. As Subaru’s only manufacturing facility outside of Asia, SIA builds about half of all Subaru vehicles sold in North America.

SIA is massive: a 2.3 million-square-foot facility on an 820-acre site in Lafayette, Indiana. It opened in 1989 and has expanded and modernized over time as Subaru’s U.S. ambitions became real.

It also gave Subaru something most automakers only talk about: environmental credibility with receipts. SIA became the first auto manufacturer in the United States to achieve zero-landfill status, on May 4, 2004. And in 2019, the plant marked a stack of milestones—its 4 millionth Subaru produced, 10 years as a zero-landfill facility, 30 years of production, and its 6 millionth vehicle overall.

IX. The Marketing Genius: Finding Your Tribe

The most remarkable part of Subaru’s turnaround in America wasn’t a new model or some breakthrough piece of engineering. It was a marketing insight—and the nerve to act on it—when other automakers wouldn’t go near it.

If you’ve ever wondered why people joke about lesbians driving Subarus, it’s not just that lesbians liked Subarus. Subaru made a deliberate choice to cultivate that association, at a time when most companies either ignored gay customers or treated them like reputational risk.

This started in the mid-1990s, when Subaru of America was struggling and sales were sliding. In a bid to change its fortunes, Subaru tried to “go upscale,” launching its first luxury car and hiring a trendy ad agency to introduce it. The campaign flopped. The agency leaned too hard into irony, and the message missed the people Subaru actually had a shot at winning.

So Subaru fired the hip agency and did something radically different: it stopped trying to out-market bigger brands for the same generic customer. After attempts to reinvigorate sales with a sports car and a young, “cool” ad strategy fell flat, Subaru leaned into niche marketing. As Tim Bennett, a former Director of Advertising, put it: “That was and still is a unique approach. I’m always amazed that no one copied it.”

The new plan was simple: find the groups already buying Subarus, then speak directly to them. The research surfaced five core segments: outdoor enthusiasts, healthcare professionals, IT professionals, educators, and lesbians.

The data on the last group was striking. Market research in the 1990s found that lesbians were four times more likely than the average consumer to already be buying Subaru vehicles—before Subaru ran a single targeted ad.

And it wasn’t lukewarm affinity. It was passion. “These women were practically commercials for Subaru,” recalled John Nash, the creative director of the agency that ultimately produced Subaru’s gay and lesbian ads, in 2004.

The hard part wasn’t finding the audience. It was reaching them in an era that was openly hostile to LGBT Americans. This was the time of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Bill Clinton would soon sign the Defense of Marriage Act. Targeting lesbian customers wasn’t just unusual—it was brave.

Subaru’s solution was elegant: coded advertising that spoke clearly to the people it wanted, while flying right past everyone else. One ad showed two Subarus with plates that read CAMP OUT and XENA LVR—a nod to Xena: Warrior Princess and its famously suggestive subtext. Another plate read P-TOWN, a reference to Provincetown, Massachusetts. The taglines carried double meanings, too: “Get Out. And Stay Out.” “It’s Not a Choice. It’s the Way We’re Built.” “Entirely Comfortable With Its Orientation.”

It was mainstream auto advertising with a secret handshake.

And it worked. Subaru’s lesbian-focused campaign was so unusual—and so successful—that it helped pull gay and lesbian advertising out of the margins and into the mainstream.

By 2000, Subaru’s sales were rising, and the company brought in Martina Navratilova as a spokesperson. A year later, Subaru recorded its best sales year to date. Over time, its market share doubled.

Subaru didn’t stop there. The broader marketing play matured into the “Love” campaign—less wink-and-nod, more emotional connection—pairing practicality and safety with a sense of identity and belonging. Subaru positioned itself as “More Than a Car Company,” supporting charitable causes and building community around shared values.

And the loyalty numbers tell you this wasn’t just a good run of ads. Subaru posted a 61.1% loyalty rate, earning the highest overall score across mainstream SUVs. In Subaru’s words: “With the vast amount of vehicle choices available to consumers today, it is even more meaningful for Subaru to have such loyal customers as part of our Subaru Family.”

Subaru also ranked highest among mass market brands—and highest overall in the automotive industry—for a third consecutive year with a loyalty rate of 61.8%.

Then there’s the statistic Subaru loves to cite because it captures the whole brand promise in one line: 96% of Subaru vehicles sold in the last 10 years are still on the road today. Whether you take that as durability, owner devotion, or both, it’s the kind of real-world credibility no advertising budget can manufacture.

X. The Corporate Transformation: From FHI to Subaru Corporation (2017)

In May 2016, Fuji Heavy Industries made an announcement that sounded like a branding tweak but was really a strategic flag in the ground: the company would rename itself Subaru Corporation, effective April 1, 2017.

The timing wasn’t accidental. The change landed alongside the 100th anniversary of Nakajima Aircraft’s 1917 founding. But this wasn’t a sentimental victory lap. It was Subaru choosing, publicly, what it wanted to be.

Two years earlier, in May 2014, Fuji Heavy had laid out its mid-term management vision, “Prominence 2020.” The headline ambition was unusually candid for the auto industry: to be “a high-quality company that is not big in size but has distinctive strength.”

That line is the whole playbook. In an industry that worships scale, Subaru was saying the quiet part out loud: we’re not going to win by becoming enormous. We’re going to win by being unmistakably good at a few things.

The name change made that philosophy legible. “Fuji Heavy Industries” described an industrial conglomerate. “Subaru” described what customers actually bought, talked about, and loved. Unifying the corporate name with the badge on the hood wasn’t just cleaner marketing—it removed a lingering identity split and reinforced that Subaru the product, Subaru the brand, and Subaru the company were now the same thing.

And that mattered internally as much as externally. By explicitly embracing that it would stay smaller than Toyota, Honda, and the other giants, Subaru let go of the old temptation to chase every segment, every region, every trend. In the 1990s, that indecision nearly broke it. By 2017, the company was institutionalizing the opposite: focus as a virtue, not a concession.

Through all of it, the aviation thread still ran underneath. Subaru’s aerospace business continued to build helicopter and aircraft components, carrying forward the manufacturing culture that began at Nakajima Aircraft. It wasn’t just heritage for the museum wall; it kept alive a pipeline of advanced processes and materials thinking that could still flow into the car business.

XI. Current Financial Position and EV Transition

As Subaru heads into 2026, it’s staring down the biggest rewrite the auto industry has faced since the Model T replaced the horse. The company is coming into that moment from a position of strength—but you can also see the stress fractures starting to form.

On the headline numbers, the recent past looks pretty good. In fiscal year 2024 (ending March 2024), Subaru’s consolidated revenue jumped, helped by higher sales and favorable exchange rates. Global production climbed to just under a million vehicles, with growth in both Japan and, especially, the United States. Unit sales rose in tandem, driven by steady demand in North America—still Subaru’s profit engine.

That volume, plus pricing and currency tailwinds, did what you’d expect: it sent operating profit sharply higher for the year.

But then the more recent quarters tell a different story. For the six months ended September 30, 2025, revenue was up year over year—more vehicles sold, a better mix, and stronger pricing—yet operating profit fell hard. The culprits were exactly what you’d fear for a mid-sized automaker trying to fund a technology transition at the wrong moment: additional U.S. tariffs, rising R&D spend, and higher raw material costs, all while foreign exchange moved against them.

Subaru was explicit about the tariff pain. In its earnings release, the company said the Trump tariffs hit operating profit by 154.4 billion yen, and it expected tariffs to widen that hit to 210 billion yen by year-end. The reason it stings so much is structural: nearly half of Subaru’s U.S. sales are still imported from Japan.

That’s the flip side of Subaru’s “deliberately small” strategy. It’s more concentrated than most Japanese rivals. Subaru still builds roughly three quarters of the vehicles it sells internationally in Japan, and its main overseas manufacturing foothold is Subaru of Indiana Automotive.

So Subaru has started making moves to reduce that exposure. It previously announced a 40 billion yen investment to start building the Forester in Indiana, and Subaru of America has said that shift is now underway—explicitly framing it as a way to increase the availability of U.S.-built Subaru vehicles.

And then there’s the even bigger transition hanging over everything: electrification.

Subaru’s stated direction has been ambitious. The company has said it will invest about $10.5 billion in vehicle electrification by 2030 (including more than $1.7 billion already announced), and it has targeted battery-electric vehicles reaching 50% of global sales by 2030—moving away from earlier plans that pegged battery-electric and hybrids together at 40%.

But the market has been messy, and Subaru has been adjusting in real time. With consumer demand shifting and key government incentives no longer as reliable, Subaru announced it would cut EV-specific investment and redirect more effort toward gas-electric hybrids, as part of revisions to its more than 1.5 trillion yen electrification investment. Importantly, Subaru said it wasn’t reducing the total spend—just reallocating it as a broader “growth investment.” CEO Atsushi Osaki put the logic plainly: with hybrid demand rising and internal combustion being reappraised, “it is appropriate to delay the timing of full-scale EV mass production investment.”

That recalibration could go further. Subaru has also considered delaying the launch of four additional EVs it planned to develop in-house by 2028, leaning more toward hybrids and gasoline-powered vehicles in the near term. As Osaki summarized it: “We will expand our product lineup to meet diverse needs.”

This is where Toyota becomes less of a nice-to-have and more of a shock absorber. Osaki has repeatedly emphasized that partnering with Toyota reduces the “huge risk” of going it alone on EVs. And he tied that caution directly to uncertainty: even after a year where operating profit surged, “it is quite difficult to predict how things will go from here with EVs.”

Subaru is still shipping product into the EV narrative, though—carefully, and with help. On April 18, 2025, Subaru unveiled the all-new 2026 Subaru Trailseeker (U.S. model) and the 2026 Subaru Solterra at the New York International Auto Show. Subaru positioned the Trailseeker as its newest and second-ever global battery-electric model, designed to blend BEV driving performance with everyday usability and “non-everyday” adventure—expanding the range of Subaru BEVs while staying on-brand.

The through-line is clear: Subaru is trying to keep its identity intact while the ground under the industry moves. The financials show it can still print money when conditions cooperate. The tariffs, the manufacturing footprint, and the EV timeline show just how fast that margin of safety can disappear.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Electrification has lowered the classic barriers to entry. Tesla showed that a newcomer can break into the global auto conversation, and Chinese manufacturers like BYD have been scaling fast. The catch is that Subaru isn’t just a “car company.” It’s a bundle of very specific competencies—especially all-wheel drive and the boxer-engine layout—that took decades to refine and to bake into products, manufacturing, and brand expectations. A startup can build an EV. It’s much harder to build Subaru’s particular version of competence and credibility. And even if you do, you still have to solve distribution: dealers, service, parts, and the trust that keeps owners coming back.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Subaru’s Toyota alliance matters here. It gives Subaru access to scale purchasing and shared tech that Subaru simply couldn’t extract on its own. Subaru’s aerospace business also provides some in-house capability for specialized work. But Subaru is still a relatively small-volume automaker, which limits its leverage with major suppliers. And because so much manufacturing is concentrated in Japan, Subaru is more exposed to supply chain shocks than peers with a broader global production footprint.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-LOW

Subaru’s biggest advantage with buyers is that many of them aren’t shopping Subaru as “one option among many.” They’re actively seeking it out. High loyalty lowers the odds that a customer will switch, and strong resale values reduce total cost of ownership, which makes the decision easier to justify. That said, cars are still cars: consumers have a lot of alternatives, and the broader market keeps pricing power in check—especially when competitors can offer similar-sized crossovers with similar feature lists.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The direct substitutes are obvious: other crossovers and SUVs, increasingly with AWD options and safety tech that looks similar on a brochure. The EV transition adds another substitution threat—if the market swings hard toward battery-electric and Subaru can’t keep pace, buyers may defect. Longer-term, ride-sharing, urban mobility solutions, and shifting preferences around car ownership could shrink demand. Subaru’s defense is that its appeal is rarely one attribute. It’s the bundle—safety reputation, standard AWD, durability, and a distinct brand feel—that’s harder to replace with any single substitute.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Subaru’s battleground is one of the most fought-over segments in the industry: crossovers and SUVs. Toyota, Honda, Mazda, and the Korean automakers all compete aggressively, with far more scale and resources. And the features that once made Subaru feel singular—AWD availability and advanced safety systems—are now table stakes across the category. Subaru’s global share remains modest, which means the company has to keep sharpening what makes it different, year after year, against competitors that can outspend it and outproduce it.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: WEAK

Subaru is intentionally not a scale player. Producing around a million vehicles a year gives it some efficiencies, but it’s operating in an industry where giants produce multiples of that. Subaru’s workaround is partnership: Toyota helps provide component and platform scale in the places where scale is non-negotiable, even if Subaru will never win on raw volume.

Network Effects: WEAK

Cars don’t naturally generate classic network effects. But Subaru has something adjacent: a real owner community. “Subarists” and the broader enthusiast and outdoors culture around the brand create a social gravity—people recommend the cars, normalize the identity, and reinforce the sense that buying a Subaru is joining something. It’s not a software flywheel, but it does strengthen retention and word-of-mouth.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG ⭐

This is Subaru’s signature power. Subaru committed to standard AWD across almost the entire lineup while competitors treated AWD as an upsell. For larger automakers, copying Subaru’s posture would have meant disrupting their own product ladders and pricing logic—effectively cannibalizing higher-margin trims and packages. Add in Subaru’s persistence with the boxer engine, its heavy safety investment, and its outdoor-adventure positioning, and you get a strategy that’s hard to mimic without paying real strategic costs.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching brands is mechanically easy—buyers can walk into another dealership tomorrow. But Subaru creates “soft” switching costs through familiarity and trust: customers get used to how Subaru’s AWD behaves, they expect EyeSight-style safety, and they value the durability and resale story. Alternatives may be good, but they can feel like giving something up.

Branding: STRONG

Subaru has built brand equity that’s unusually coherent: safety, reliability, durability, and an outdoorsy, values-forward identity. The “Love” era of marketing didn’t just communicate features; it built emotional affiliation. That branding strength helps Subaru price confidently relative to size and spec, because customers aren’t only buying transportation—they’re buying what Subaru signals about them.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Subaru’s “resource” isn’t a single patent. It’s accumulated know-how: decades of AWD tuning, boxer-engine packaging, and continual refinement of safety systems like EyeSight. Competitors could replicate pieces of this with enough time and money, but they’d be building from scratch what Subaru has been compounding for generations.

Process Power: MODERATE

Subaru’s aerospace-derived, engineering-first culture shows up in its consistency: it keeps executing the same differentiation strategy across products and years, rather than reinventing itself every cycle. Safety thinking is integrated into development, not bolted on. Operationally, Subaru has also demonstrated discipline—Subaru of Indiana Automotive’s zero-landfill achievement is a concrete example of process rigor, not just a slogan.

XIII. Key Metrics to Track and Investment Considerations

If you’re looking at Subaru as a long-term, fundamentals-driven investment, you don’t need a hundred KPIs. You need a few that actually steer the story. Three matter most:

1. U.S. sales momentum and market share

Subaru is, in a very real sense, an American car company with Japanese factories. More than 70% of Subaru’s global sales come from the U.S., and North America is where the profits are made. That means any sustained softening in U.S. demand isn’t a rounding error—it’s the core risk.

So track the basics, but track them consistently: monthly sales releases, year-over-year comparisons, and whether growth streaks keep extending or finally snap. Subaru’s identity, dealer health, and pricing power are all downstream of U.S. momentum.

2. EyeSight penetration and third-party safety leadership

Subaru has turned safety into brand equity, and brand equity into pricing power. But moats aren’t permanent—they’re maintained.

So keep an eye on the proof points that reinforce the safety story: IIHS results versus the competitive set, how widely EyeSight remains standard or near-standard across new models, and whether rivals’ next-generation ADAS starts to feel meaningfully better in the real world. If Subaru slips from “obvious safety leader” to “just as good as everyone else,” the entire flywheel gets weaker.

3. The Toyota relationship and the pace of electrification

Toyota is Subaru’s greatest stabilizer—and the relationship you have to watch most carefully. It lowers Subaru’s cost of surviving the EV transition, but it also increases dependency.

Monitor the tells: new joint development announcements, any change in Toyota’s equity stake, and whether the co-developed EVs actually land with customers. The real question isn’t “Can Subaru build EVs?” It’s “Can Subaru stay Subaru in an EV world, and can it do it without Toyota quietly becoming the operating system?”

Bull Case

Subaru’s “small but distinctive” strategy gets more valuable as the auto market fragments. The EV shift doesn’t only reward the biggest players; it also creates openings for brands with clear identity, as long as they can translate that identity into new powertrains. Subaru has a credible claim to a specific kind of customer—people who want safety, all-weather confidence, and practical ruggedness—and that promise can carry into EVs and hybrids.

In this bull case, the Toyota partnership functions exactly as intended: Subaru gets access to platforms, batteries, and scale economics without having to bet the entire company on a solo EV roadmap. Loyalty stays high, hybrids serve as a smart bridge while the market’s EV timeline shakes out, and macro trends like an aging population that prioritizes safety and worsening weather that increases demand for all-weather capability keep playing to Subaru’s strengths.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with margins. Tariffs and import exposure force ugly choices: raise prices and risk demand, or eat costs and watch profit compress. Meanwhile, electrification changes what differentiation looks like. Boxer engines matter less in a world where electric motors deliver torque instantly, and traction control can replicate a lot of what used to require mechanical magic.

Competition also gets nastier. Lower-priced EV entrants—especially from China if they reach the U.S. in force—could offer compelling alternatives. Subaru’s smaller scale makes it harder to keep up with the industry’s spending race in software-defined vehicles and autonomous features. And then there’s the partnership risk: Toyota could choose to exert greater influence, tightening Subaru’s strategic freedom right when independence matters most. Finally, safety tech could commoditize if competitors close the gap, turning EyeSight from a differentiator into table stakes.

Myths vs. Reality

Myth: Subaru is just a quirky niche brand with limited growth potential.

Reality: Subaru delivered the fastest growth among mainstream U.S. automakers during the 2010s. It proved that focused differentiation can scale—especially when the market moves toward exactly what you’re good at.

Myth: Toyota effectively controls Subaru.

Reality: Toyota owns about 20%, but Subaru remains operationally independent. Toyota has also stated it has no interest in a full acquisition, and Subaru continues to run its own brand and product strategy.

Myth: AWD is commoditized now that everyone offers it.

Reality: AWD availability has increased, but Subaru’s symmetrical system and decades of refinement still shape how its cars feel and perform. Even more important: in consumers’ minds, Subaru and all-weather capability are culturally linked, not just mechanically similar.

Myth: Subaru is behind on electrification and will be disrupted.

Reality: Through Toyota, Subaru has access to EV platforms and battery technology. Subaru’s slower, more deliberate pace could be an advantage if EV adoption continues to wobble relative to earlier projections.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

Regulation is the constant pressure in the background. Subaru’s continued reliance on internal combustion—even efficient versions—creates exposure as more jurisdictions mandate zero-emission vehicles. In the U.S., tariff policy remains a live wire given Subaru’s heavy import mix. On the brand side, any meaningful slip in IIHS or NHTSA outcomes would do real damage, because Subaru has spent decades turning safety into trust.

The company hasn’t disclosed material legal contingencies that would obviously change the long-term picture, but warranty costs are worth watching as EyeSight and other advanced systems become more complex and more central to the ownership experience.

XIV. Conclusion: The Power of Knowing What You're Not

Subaru’s story carries a lesson that feels almost backwards in an industry obsessed with scale: sometimes the winning move is knowing what not to do.

While rivals chased global dominance and a model lineup for every imaginable customer, Subaru chose restraint. It accepted that it would never out-Toyota Toyota. Instead, it built a business around a handful of non-negotiables—and then executed them with almost stubborn consistency.

You can trace that through-line all the way back to Nakajima Aircraft: an engineering culture built on precision, testing, and systems thinking. On the road-car side, it shows up in choices that look quirky until they compound into identity: the boxer engine’s low, stable layout; symmetrical all-wheel drive as a default, not an upsell; and EyeSight evolving from an experiment into a safety reputation that third parties validated year after year. Subaru didn’t win by being broadly “good.” It won by being unmistakably good at a specific bundle of things—and by making that bundle hard for larger competitors to copy without breaking their own economics.

The Toyota partnership is the purest example of that same mindset. Subaru didn’t treat independence as the only virtue. It took the deal: be the smaller partner, keep the character, and gain access to the scale and technology needed to survive the next era. For a company that nearly went off the road in the 1990s, that pragmatism isn’t weakness—it’s learned wisdom.

None of this erases the risks. Tariffs hurt more when you import so much. The EV transition is expensive and uncertain. And relying heavily on the U.S. for volume and profit concentrates the downside when the market turns. Subaru’s margin for error will never be as wide as the giants’.

But if there’s one thing Subaru has proven across war, reinvention, near-collapse, and comeback, it’s durability—strategic and cultural. It keeps showing up with a clear point of view, and it keeps finding customers who want exactly that.

For anyone who follows the full arc—from fighter planes to scooters to rally championships to crossover dominance—Subaru stands out as something increasingly rare in modern automotive: a company that knows what it is, and just as importantly, what it isn’t.

And those six stars still mean what they always meant: separate parts, aligned into one constellation, moving in the same direction.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music