Aisin Corporation: The Hidden Giant Behind Every Toyota

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

A thirty-two billion dollar company. One hundred twenty thousand employees. More than two hundred consolidated subsidiaries around the world. And yet, if you stopped someone on the street in America and asked if they’d heard of Aisin Corporation, you’d probably get a blank stare.

That’s the magic trick Aisin has been pulling for decades: enormous scale, near-zero consumer visibility.

Aisin was formed in 1965 and today supplies a huge swath of the modern car—engine and drivetrain components, body and chassis systems, aftermarket parts—for Toyota and plenty of other automakers. It’s one of the biggest players in global manufacturing, hiding in plain sight inside products that millions of people use every day.

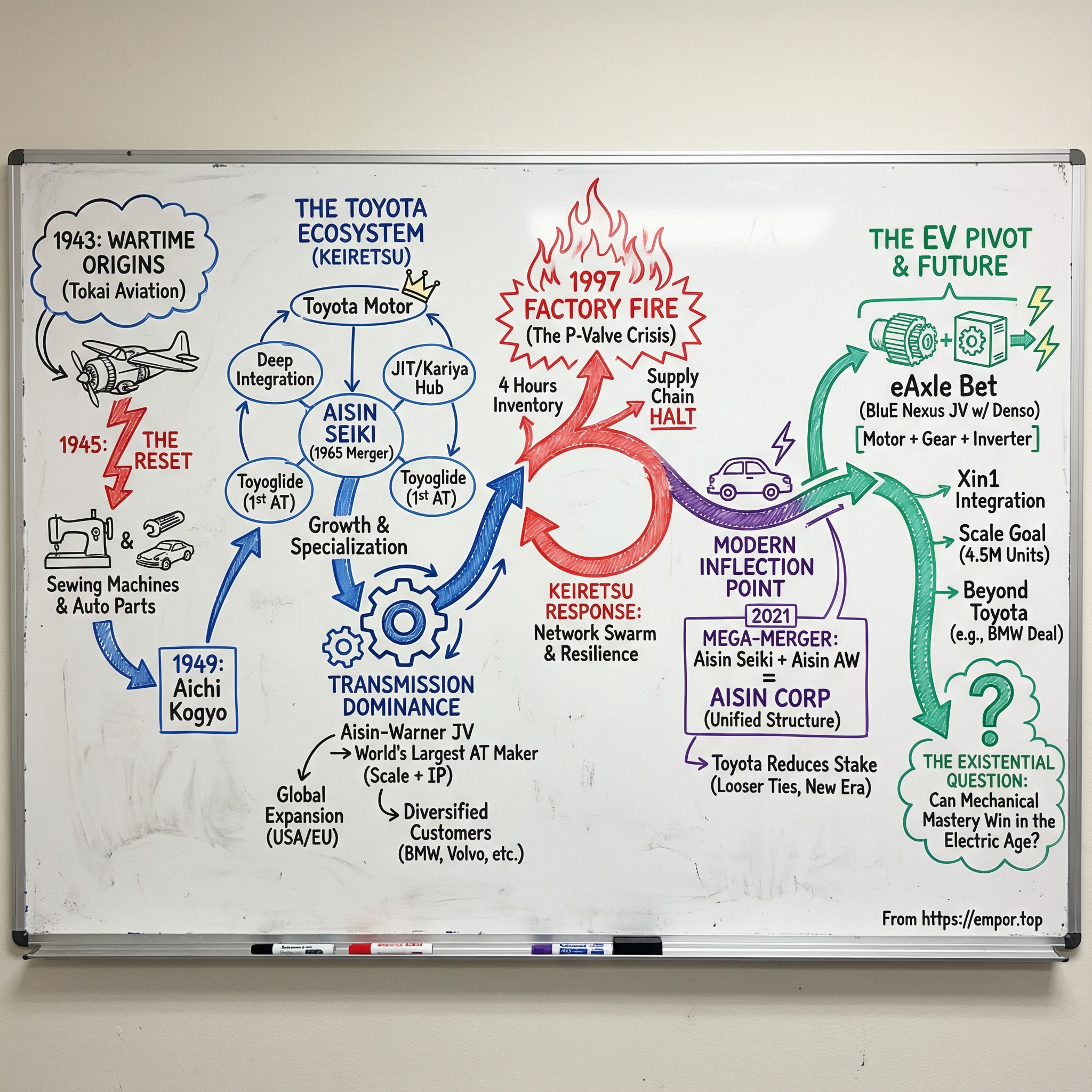

Here’s the puzzle we’re going to unravel: how did a wartime aircraft-engine effort, born in Japan’s total-war industrial push in 1943, turn into the invisible backbone of Toyota—and the world’s largest transmission maker? The origin story starts with Tokai Aviation Industries, a joint venture between Toyota Motor Corporation and Kawasaki Aircraft Industries, created to build aircraft engines for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service.

Fast-forward to the modern era and you see just how far that expertise traveled. When BMW developed vehicles on its FAAR platform—shifting from rear-wheel drive to front-wheel drive—it also switched transmission suppliers. Instead of ZF, BMW went with Aisin. The same pattern shows up across Volvo, Peugeot, and plenty of other OEMs: when they need a transmission that’s reliable at massive scale, they end up in Aisin’s orbit.

So even if you’ve never heard the name, every time you drive a Toyota, Lexus, BMW, Volvo, or Peugeot, there’s a very good chance Aisin technology is what’s translating power into motion.

And now we hit the big, uncomfortable question—because the industry is changing underneath them. At what might be the most important inflection point in automotive history, the shift to electric vehicles, Aisin faces an existential challenge: can the world’s largest transmission maker thrive in a world that needs far fewer transmissions?

This story is about keiretsu—Japan’s web of interlocking corporate relationships that creates a kind of resilience most Western companies never build. It’s about specialization and manufacturing excellence, and about what happens when the thing you’re best in the world at starts to disappear.

Here’s where we’re going. We’ll trace Aisin’s arc from wartime aircraft engines to postwar sewing machines; from Japan’s first domestically produced automatic transmission to the eAxle systems intended to power Toyota’s electric future. We’ll relive the 1997 factory fire that became one of the most famous supply chain case studies ever—and a defining moment for Toyota and Aisin alike. And we’ll ask whether a company built for the internal combustion era can reinvent itself fast enough for what comes next.

II. Wartime Origins & The Toyoda Dynasty

In the waning days of 1942, with World War II raging across the Pacific, Japan’s military demanded every ounce of industrial capacity it could squeeze out of the country. Aircraft engines and engine parts were in desperately short supply. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service needed more output, and it needed it immediately.

So in 1943, Kiichiro Toyoda—the founder of the Toyota Group—helped create a new company: Tokai Aircraft Company. Its job was straightforward: manufacture engine parts for wartime aircraft.

On paper, Kiichiro was an odd fit for aviation. The Toyoda family fortune came from textile machinery. Kiichiro’s father, Sakichi Toyoda, had invented Japan’s first power loom and built an industrial empire around automated looms. Kiichiro had taken that inheritance and bet the family’s future on cars in the 1930s, founding Toyota Motor Corporation. But in wartime Japan, what you wanted to build didn’t matter much. The state told you what to build.

Tokai Aircraft—also referred to as Tokai Hikoki—was set up as a joint venture with serious backing. It had capital of 50 million yen (including 12.5 million yen in paid-in capital), with 60 percent provided by Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. and 40 percent by Kawasaki Aircraft. The head office was in Tokyo, in Yotsuya 3-chome, Yotsuya-ku. Kiichiro Toyoda was appointed president.

It was, in many ways, a marriage of convenience: Toyota brought manufacturing muscle; Kawasaki brought aviation know-how. Construction began on a plant next to Toyota Machine & Tools in Kariya—the city that would remain the company’s home base for decades.

But Tokai Aircraft never really got the chance to become what it had been created to be. The war ended before it reached full-scale production. And in a twist that ended up shaping postwar Japan, the company was even displaced before it could ramp. Eiji Toyoda later described what happened:

“But in 1945 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ Nagoya works was destroyed by U.S. bombers, so the military had Mitsubishi move to Tokai Aircraft, driving us out. The military probably figured that it couldn’t afford to wait any longer for us to build our souped-up Benz engines.”

Then came August 1945, Japan’s surrender, and the hard reset that followed. The occupation authorities ordered Japanese industry to abandon military production. Tokai Aircraft had facilities, equipment, and trained workers—but its original purpose was gone. It had to find a new reason to exist, almost overnight.

In 1945, at the close of the war, Tokai Aircraft switched production to sewing machines and automotive parts—both of which had been in short supply during the war.

That decision wasn’t glamorous, but it was smart. Japan’s textile economy needed to rebuild fast, and sewing machines were suddenly essential household and industrial tools. Just as importantly, the precision manufacturing skills developed for aircraft components translated well to sewing machines. And making automotive parts was a natural extension of the Toyoda world.

Four years later, the company made its next pivot—from wartime identity to peacetime permanence. In 1949, Tokai Aircraft Company changed its name to Aichi Kogyo Company. It was a fresh start and, symbolically, a step away from its military origins. It also marked the early shape of what would later become Aisin Seiki.

But one thing didn’t change: the Toyoda connection.

Despite its size, Aisin—and the wider Toyota group—has always had a family-business dimension to it. Aisin’s current chairman, Kanshiro Toyoda, is an extended relative of Akio Toyoda, and Toyoda family members have held board or chairman roles across companies in the Toyota keiretsu.

This matters because it explains something that can otherwise feel mysterious from the outside. In a lot of Western industries, supplier relationships are arm’s-length and constantly re-bid. In the Toyota ecosystem, they’re deeper than that—long-term, intertwined, built on shared history and shared incentives. As we watch Aisin grow, and later respond to crisis and industry upheaval, keep that in mind: this wasn’t just a vendor. It was part of the family system.

III. Building the Toyota Ecosystem: The Keiretsu Model

The 1950s and 1960s were years of patient, almost quiet, foundation-building. Aisin’s world was still domestic—its operations were confined to Japan—and its role was clear: supply parts to Toyota and keep churning out sewing machines for a country rebuilding from scratch.

But underneath that steady rhythm, Aisin was learning how to become indispensable. This was the period that set the company’s default settings for decades to come: tight integration with Toyota’s development cycle, obsessive manufacturing quality, and a focus on specialized, hard-to-copy components that could become bottlenecks—in the best possible way.

Then came the moment where the pieces were formally locked together.

In 1965, Aichi Kogyo Co., Ltd. merged with its sister company, Shinkawa Kogyo Co., Ltd. The result was Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd., created to consolidate strengths and build a corporate structure that could compete internationally.

This wasn’t just a legal reorg. It was the birth of the Aisin we know today. The name “Aisin” itself was chosen deliberately—a phonetic rendering of characters suggesting “love” and “progress.” And strategically, the merger broadened what the company could do for Toyota: Aichi Kogyo brought expertise in transmissions and clutches; Shinkawa Kogyo added body parts and other components. Together, they became a more complete systems supplier rather than a narrow parts shop.

To really understand why that mattered, you need to understand keiretsu—the postwar Japanese model of interlocking corporate relationships that sits somewhere between a supply chain and a family tree. Aisin Seiki became one of 15 members of the Toyota Group. Toyota Motor Corporation owned about 22% of Aisin, and about 70% of Aisin’s products were sold to Toyota.

But the equity math is only the surface. In a keiretsu, the bond isn’t just shares; it’s the operating system. Companies don’t simply transact. They co-develop parts, share manufacturing methods, coordinate capacity, exchange employees, and show up for each other when things go wrong. Toyota didn’t just buy parts from Aisin. Toyota and Aisin built Toyota cars together.

You can see that ecosystem physically on a map. In Japan, Toyota’s gravitational pull is strong enough that entire cities tilt around it. Kariya, in Aichi Prefecture, is one of those places. It’s about 20 kilometers from Toyota’s headquarters in Toyota City, and it’s home to major Toyota Group companies—Denso and Aisin included.

That proximity wasn’t convenience; it was strategy. The Toyota Production System depends on just-in-time delivery and fast problem-solving. Both get easier when suppliers are close enough to drive over, stand on the factory floor together, and fix issues face-to-face. Over time, Aichi Prefecture turned into an automotive ecosystem—dense, fast, and coordinated—where parts could arrive quickly and engineers could collaborate without bureaucracy getting in the way.

Aisin’s early technical breakthrough showed just how quickly it was leveling up. The Toyoglide—Japan’s first domestically produced automatic transmission—became one of the earliest examples of Toyota “Crown technologies” involving Aisin. Japan’s automatic-transmission era effectively began when Toyoglide was installed in the first-generation Crown, Japan’s first luxury passenger car. Automatic transmissions made driving easier and more comfortable, and it was obvious there was a market waiting.

In 1961, Aichi Kogyo, Aisin’s predecessor, took on the job of manufacturing the first-generation Toyoglide. It wasn’t just a new product. It was Japan proving it could build a core piece of automotive technology domestically, rather than relying on foreign suppliers—and Aisin was right at the center of that leap. By 1965, Aisin had produced 50,000 Toyoglide units, an early signal that this company could build complex precision hardware at scale.

The keiretsu model that enabled all of this comes with a built-in tradeoff. The upside is enormous: access to Toyota’s volumes, deep technical collaboration, and long-term stability. The downside is just as real: heavy customer concentration, the risk that Toyota’s priorities can pull the whole ecosystem in one direction, and the looming question for the future—when the industry changes, does this tight integration help Aisin move faster, or does it make it harder to break from the old playbook?

IV. The Transmission Revolution: Aisin-Warner Joint Venture

By the late 1960s, Aisin had a good problem: Toyoglide was working, and automatic transmissions were starting to feel like the future. But success came with a risk. As Toyoglide spread, so did an uncomfortable question—were they stepping on patents held by Borg-Warner, one of North America’s premier transmission players?

Instead of stumbling into years of litigation or a messy licensing fight, Toyota, Aisin, and Borg-Warner took a very Toyota-style path: turn the conflict into a collaboration.

In 1969, they created Aisin-Warner Limited, a Japan–U.S. joint venture dedicated to automatic transmissions. Borg-Warner brought decades of hard-earned know-how from the American market, where automatics had long been the default. Aisin brought manufacturing discipline and proximity to Toyota’s growing needs. And Toyota got something even more valuable than a parts supplier: a focused transmission specialist that could scale with it.

The early days weren’t smooth. Under a technical director dispatched from Borg-Warner’s British subsidiary, engineers pushed through basics that sound small until you imagine them inside a factory—language barriers, deciphering engineering drawings written in English, and writing detailed English reports back to Borg-Warner. Still, after three years of development, they finished the 03-55 transmission, which went into the fifth-generation Crown.

Then Aisin-Warner did something that signaled exactly what kind of company this would become: a 100 percent inspection policy. Every completed automatic transmission was mounted in an actual vehicle and put through a specific-distance driving test. Most competitors tested samples. Aisin tested everything.

Over time, the partnership shifted from joint venture to graduation. In 1981, BorgWarner reduced its equity in Aisin-Warner to 10%, and by 1987 it had sold the rest. By the late 1980s, Aisin had absorbed what it needed—transmission design capability, production expertise, and the confidence to stand on its own.

The results showed up at world scale. As of 2005, Aisin AW had surpassed General Motors’ Powertrain Division as the largest producer of automatic transmissions in the world, making 4.9 million units and holding 16.4% of the global automatic transmission market.

That’s the kind of milestone that’s easy to miss if you only track car brands. A supplier—quietly, methodically—outproduced the in-house transmission operation of the biggest automaker in the world at the time.

And Aisin AW didn’t stop at volume. It developed the Toyota Prius transmission and the world’s first speaking navigation system. The Prius work mattered in particular: when Toyota launched the Prius in 1997, it needed a transmission that could blend gasoline and electric power in a way that could actually be mass-produced. Aisin AW made it real.

Later, Aisin logged another major milestone: the world’s first eight-speed torque converter automatic transmission for transverse engines.

This is why transmissions are such a powerful strategic beachhead. They’re brutally complex systems with hundreds of precision parts that have to work flawlessly under heat, stress, and constant cycling. They demand huge capital investment in specialized tooling. And they reward accumulated engineering experience—the kind you build over decades, not quarters. All of that creates real barriers to entry.

Aisin AW went on to supply automatic transmissions to 55 automotive manufacturers around the world, including General Motors, Ford, Jeep, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Saab, VW, Volvo, Hyundai, and MINI.

And when automakers like BMW, Volvo, and Peugeot need transmissions for front-wheel-drive vehicles, Aisin is often where they land. The AISIN AWF8F Series became especially common in the transverse automatic market, used across many models globally. Part of that strength appears to come from deep intellectual property in this area, which has helped keep competing products limited.

In other words: years of engineering didn’t just turn into better transmissions. They turned into defensibility—knowledge embedded in manufacturing, locked into customer platforms, and reinforced by patents that made “just copy it” a non-option.

V. The 1997 Fire: A Supply Chain Masterclass

At 4:18 a.m. on Saturday, February 1, 1997, a fire broke out at Aisin Seiki’s Factory No. 1 in Kariya. Within hours, flames tore through the lines that made a part almost no driver on earth had ever heard of: the P-valve, a small proportioning valve that helps prevent rear-wheel lockup during braking.

It was also the kind of part that can stop the entire automotive machine cold.

Aisin was Toyota’s sole supplier of that valve. And because Toyota ran on the Toyota Production System, “inventory” wasn’t a warehouse full of safety stock. Toyota’s plants reportedly carried about four hours’ worth of P-valves.

Four hours. That was the gap between “everything is fine” and “the world’s most efficient car company can’t build cars.”

The immediate fear wasn’t just that Aisin’s plant had burned. It was that rebuilding P-valve production could take months. If that happened, Toyota’s global production network—built to produce millions of vehicles a year—would grind to a halt for weeks.

The scale of the problem was brutal. Toyota was producing roughly 15,000 vehicles per day, and every one needed P-valves. Before the fire, Aisin had been making 32,500 P-valves a day. With no backup supplier and almost no inventory, Toyota stared down losses that were estimated in the hundreds of billions of yen, before you even counted the ripple effects to suppliers, dealers, and the broader economy.

Aisin and Toyota set up a crisis room and went straight to work on the only thing that mattered: getting P-valves made again, anywhere, by anyone, fast. Toyota pulled in engineers. Suppliers were asked to work overtime, bring in people, and help build or modify equipment that could produce the valves and their components.

Then the keiretsu did what it was built to do.

Within hours, Toyota and Aisin weren’t acting alone—they were mobilizing an entire network. Companies that had never made brake components, that normally produced completely different parts, volunteered capacity. They took drawings, sourced materials, reconfigured machines, trained workers, and aimed for Toyota-level quality under impossible time pressure.

The turnaround still feels unreal.

The first batch of P-valves reached Toyota on February 5—four days after the fire. By February 10, more than 200 suppliers were involved in producing P-valves, and Toyota was back to normal production levels. Toyota was able to resume production after only two days.

That’s why this incident became one of the most famous supply chain case studies in business school history. It’s not just a story about a factory fire. It’s a story about what a system looks like when it’s designed around relationships, not transactions.

Because one detail captures the whole thing: suppliers reportedly did not begin by asking what they’d be paid for rushing out P-valves.

In an arm’s-length supply chain, the first conversation is often commercial. Rush orders mean premium pricing. Retooling means surcharges. Overtime means line items. Here, the network moved first, trusting that Toyota would settle up afterward.

And Toyota did. It provided its first-tier suppliers with payments equal to 1% of their sales, totaling more than ¥15 billion. It wasn’t finger-pointing. It wasn’t punishment. It was Toyota reinforcing the behavior it depended on: show up when it counts, and the system will take care of you.

The deeper reason the recovery worked is that the ecosystem had been training for this moment without realizing it. In a JIT environment, workers and managers develop strong problem-solving capabilities. Within the Toyota group, practices like knowledge sharing and regular employee transfers across firms build common ways of working. That creates a kind of distributed manufacturing muscle—one that can be redeployed fast when a single node fails.

The Aisin fire became a watershed moment. It pushed Toyota to rethink supply chain risk management, but without abandoning the core benefits of just-in-time manufacturing. And it permanently cemented Aisin’s identity inside the Toyota universe—not just as a supplier, but as part of an operating system that, under extreme stress, proved it could bend without breaking.

VI. Going Global: From Japan to the World

The 1997 fire proved just how strong Aisin and Toyota’s Japan-centered ecosystem could be under pressure. But that resilience wasn’t meant to stay domestic. Long before the smoke cleared in Kariya, Aisin had already been laying rails for a global manufacturing network—expanding in lockstep with Toyota’s international push, while also building the credibility to win business on its own.

The beachhead was the United States. In 1986, Aisin built a factory in Seymour, Indiana, and by 1989 it was in production. Over time, the site expanded and began supplying components not just to Toyota, but to a broader lineup that included Honda, General Motors, Mitsubishi, and Nissan.

That detail matters. Seymour wasn’t simply “Toyota in America.” It was Aisin proving it could land and serve major non-Toyota customers at scale—on their turf, with their standards, and with the kind of consistency that turns a supplier into a long-term partner.

By the 2000s, Aisin’s North American presence had grown into a real platform. Across the region, Aisin Group companies reached more than $5 billion in sales, with about 14,000 employees and 36 manufacturing, sales, and R&D centers. And then there’s the facility that really signals intent: FT-Techno of America in Fowlerville, Michigan—a test track and proving ground spanning roughly 950 acres.

A proving ground like that is a statement. Aisin opened Aisin USA’s facility there on October 5, 2005, and it wasn’t built for show. With tracks designed for durability testing and performance evaluation, it lets Aisin do development and validation work locally, in real conditions, without treating Japan as the only center of gravity. If you want to be a serious supplier in North America, you don’t just manufacture there. You engineer there.

Europe got its own version of that long-term investment through IMRA—Institut Minoru de Recherche Avancée—founded in 1986 in Sophia Antipolis, France. IMRA operates across Europe, the U.S., and Japan, and functions as a key part of Aisin’s advanced R&D and technology consulting capability. Its U.S. division, IMRA America, was founded in 1990 in Ann Arbor, Michigan. IMRA’s work spans areas like biomedical research, batteries, and femtosecond lasers—fields that go well beyond conventional auto parts.

That’s a different kind of globalization. It isn’t only about placing factories near customers. It’s about placing research near ideas—and building the option value to play in technologies that may not look “automotive” today, but could matter enormously tomorrow.

The strategic payoff of this footprint is bigger than market access. It lets Aisin serve global automakers wherever they build, reduces exposure to currency swings by producing locally, and keeps the company close to technology trends across regions. In a world where competitors like ZF and Aisin span Asia, Europe, and North America—and where players like BorgWarner and Allison are particularly strong in U.S. commercial and off-highway markets—being global isn’t a brag. It’s table stakes.

VII. The 2021 Mega-Merger: Aisin Seiki + Aisin AW

In October 2019, Aisin Seiki announced it would merge with its subsidiary, Aisin AW—consolidating management under one roof and, in the process, retiring two legacy names. On April 1, 2021, the deal took effect. The combined company became what it’s called today: Aisin Corporation.

This was the pivotal structural move of the last decade. Aisin didn’t just tidy up an org chart. It rewired itself for a world where the drivetrain is being reinvented.

To see why, you have to look at what “Aisin” actually was before the merger. Aisin Seiki was the parent: body components, chassis parts, engine components, and a broad portfolio of automotive systems. Aisin AW was the specialist jewel: the transmission powerhouse that had grown into the world’s largest producer of automatic transmissions. And crucially, they weren’t simply two divisions. They ran with separate management teams, separate strategies, and separate profit responsibilities.

So when April 2021 arrived, it was a real consolidation. Aisin merged business operations with Aisin AW and launched the new, unified company. In the Americas, the group footprint included roughly 14,000 employees and more than 40 manufacturing, sales, and R&D centers—evidence that this wasn’t a Japan-only reshuffle, but a global one.

The merger mattered because the EV transition changes what the “core product” even is. In an internal-combustion vehicle, the transmission is a discrete, complex system—almost its own kingdom. In a battery-electric vehicle, that kingdom collapses into an integrated drive unit. The eAxle bundles the motor, gears, and power electronics together, and it has to play nicely with thermal management, vehicle dynamics, and software controls. In that world, keeping a hard organizational boundary between the “body and chassis company” and the “transmission company” starts to look less like focus and more like friction.

As one Aisin leader put it, AW had long been a core part of the family—known for rapid technology development, impeccable quality, and speed—and now it would become “a driving force” inside the new Aisin Corporation.

The integration didn’t stop at the nameplate. Aisin reorganized major product domains—MT, brakes, seats, and body—aiming to strengthen competitiveness by consolidating business functions and allocating resources more rationally.

And zooming out, this wasn’t only an Aisin decision. It fit into a broader Toyota Group reorganization, with business domains being reshaped across the keiretsu so capabilities sat in more logical groupings. Even as cross-shareholdings slowly loosened, the coordination impulse—the instinct to redesign the system together—was still very much alive.

For investors, the message was straightforward: management was acknowledging that the old structure had been optimized for a world that was disappearing. A consolidated Aisin could deploy capital more efficiently, cut redundant functions, and build integrated product strategies that would have been far harder to execute with two separate leadership teams pulling in parallel.

VIII. The EV Pivot: BluE Nexus and the e-Axle Bet

This is the existential question for Aisin: Can the world’s largest transmission maker survive a world without transmissions?

Aisin’s bet is that the “new transmission” of the EV era is the eAxle: a single drive unit that integrates the electric motor, gearing, and power electronics. If the internal combustion age was defined by engines plus multi-speed gearboxes, the battery-electric age is defined by integration. And Aisin wants to be one of the companies that owns that integrated box.

To do it, Aisin didn’t go alone. In April 2019, it formed BluE Nexus, a joint venture with Denso to develop electric powertrain systems. Both companies sit inside the Toyota Group, and Toyota Motor Corporation took a 10% stake. The flagship product is the e-Axle, integrating an electric motor, gears, and an inverter.

The logic of the pairing is clean. Aisin brings decades of expertise in gears and mechanical integration. Denso brings leadership in power electronics—especially inverters. In the BluE Nexus setup, Aisin handles the motor and gears, while Denso provides the inverter.

Technically, an eAxle is exactly what it sounds like: a drive unit built into the axle structure that contains the major components needed to propel a battery-electric vehicle. In practice, it’s typically a gearbox, a motor, and an inverter packaged as one. By integrating these pieces, the unit can be smaller and lighter, with knock-on benefits like space savings, lower power consumption, and lower cost.

Both partners arrived with real scar tissue and real scale. Aisin had developed and produced more than five million electric units since launching its first hybrid transmission in 2004. Denso had developed and produced more than twenty million inverters since the first Prius launched in 1997. Put together, it’s a rare combination: deep mechanical manufacturing DNA fused with high-volume automotive electronics.

The first major commercial proof point was Toyota’s bZ4X. BluE Nexus, Aisin, and Denso jointly developed an eAxle for the vehicle, aiming for strong driving performance while shrinking the package to help extend electric driving range.

From there, Aisin laid out a clear, three-generation roadmap.

The first-generation eAxle is already in mass production. The second generation is planned for 2025, with a small, medium, and large lineup designed to deliver both higher efficiency and a more compact form factor as BEV demand accelerates. Aisin has said this second-generation effort targets meaningfully higher efficiency, substantial size reduction, and higher output versus competing products.

Then comes the third generation: “overwhelming miniaturization,” with a goal of cutting overall size in half versus the first generation.

Beyond that, Aisin is pushing an even more aggressive idea it calls Xin1—where “X” represents how many components and functions get integrated into one unit. The mainstream eAxle today is a 3in1 product, combining motor, gearbox, and inverter. Xin1 points to a future where additional systems are folded in too: power conversion, thermal management, and integrated control functions related to vehicle motion. The promise is straightforward: less space, less weight, and less energy lost to heat—so automakers can use the freed-up room for batteries, cabin space, or better packaging flexibility.

Aisin’s central argument is that it isn’t starting from zero. The gears, shafts, and casings that made it a transmission giant are exactly the kind of hard-won mechanical competencies an eAxle still needs. Just as important, Aisin believes it can repurpose and adapt production equipment—one of the most overlooked advantages in a transition that’s as much about manufacturing scale as it is about technology.

That message shows up in how Aisin talks about the work. “AISIN has a history of more than half a century of pursuing ‘high efficiency and miniaturization’ in transmission development,” says Kuboyama. “We have built up technologies to make each component smaller and more efficient.”

And crucially, Aisin has been working to make this an “outside Toyota” story, not just a Toyota Group internal upgrade.

Aisin and Subaru agreed to jointly develop eAxles and share production for BEVs Subaru plans to produce from the latter half of the 2020s.

Even more notable: BMW. Aisin and the BMW Group agreed on a strategic partnership focused on build-to-print e-axle production—Aisin manufacturing an e-axle based on a BMW design. Production is planned in both China and Europe, with installation in BMW vehicles targeted for the late 2020s. To support that, Aisin planned to expand capacity by extending a plant at AISIN Europe Manufacturing Czech in the Czech Republic.

The BMW deal is revealing because it highlights Aisin’s most durable value: world-class manufacturing at automotive scale. Even when an OEM wants to control the design, Aisin can still win the job by being the partner that can reliably build it—at quality, in volume, across regions. It’s also exactly the kind of customer diversification Aisin needs as the industry moves into electrification.

To support all of this, Aisin has been strengthening its production system region by region, aiming to establish a global production setup with annual output of 4.5 million electric units by 2025.

Aisin is one of the world’s largest Tier One automotive suppliers, and it was early to eAxles. But the real story isn’t “they got there first.” It’s whether the company that mastered the most complex mechanical product of the combustion era can become just as essential in a future defined by integration, electronics, and relentless cost-down.

IX. Toyota Reducing Stakes: The Evolving Relationship

In June 2024, Toyota announced a meaningful update to its relationship with Aisin—one that says a lot about how the keiretsu model is adapting to modern capital markets.

Toyota Motor Corporation said it would sell a portion of its shareholdings in Aisin as part of what it called a “revision of capital ties aimed at the growth of the Toyota Group,” an initiative it said had been underway since the prior year. The headline number: Toyota aimed to sell about a 4.8% stake, which would reduce its ownership to roughly 20%.

Toyota wasn’t alone. Toyota Motor, Denso, and Toyota Industries also planned to sell a combined stake of at least 12.5% in Aisin, continuing a broader push to unwind cross-shareholdings across the group. This followed similar moves elsewhere in the ecosystem, including the sale—by Toyota Motor, Toyota Industries, and Aisin—of a combined stake in Denso the year before. The logic is consistent: free up capital so the group can fund the expensive transition to battery-electric vehicles and other technology investments.

Toyota framed the move as part of a groupwide restructuring it has pursued since 2016 with a “home & away” perspective. After extensive discussions among Toyota, Aisin, Denso, and Toyota Industries, they agreed Toyota would reduce its Aisin stake. Toyota’s message was essentially: we can boost capital efficiency and fund growth, while still maintaining the capital ties that support the relationship.

The context here matters. Cross-shareholdings in Japan have faced increasing pressure from corporate governance advocates, who argue these arrangements can create overly comfortable relationships between management and major shareholders, sometimes at the expense of minority investors. As more Japanese companies wind down the practice, Toyota’s ties across its supplier network have come under sharper scrutiny too.

And yet, even after these reductions, Toyota remained a major owner. As of March 31, 2025, Toyota Motor Corporation held a 21.35% voting ratio in Aisin—still a substantial stake, and still a clear signal that Aisin’s direction remains closely aligned with Toyota Group priorities.

Crucially, the stake reduction wasn’t positioned as a breakup. Aisin said it would continue strengthening the Toyota Group’s competitiveness by leveraging its breadth in hardware and software, plus its manufacturing capabilities. Toyota, meanwhile, planned to redeploy the proceeds into growth investments centered on electrification, intelligence, and diversification.

That’s the trade: loosen the ownership web, but keep the operational bond.

For investors, this shift cuts both ways. On the upside, reduced cross-shareholdings can make Aisin more legible—and potentially more attractive—to global investors who prefer cleaner governance structures. It may also give Aisin more room to pursue non-Toyota business aggressively as the industry electrifies.

On the downside, it raises the question everyone thinks about, even if they don’t say it out loud: if the equity ties keep thinning, do the relationships still hold with the same force? In a crisis, does the keiretsu still respond like it did in 1997—or was that level of coordination inseparable from the old, tighter model?

X. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you want to understand why Aisin has been so durable, start here: transmissions are one of the hardest products in mass manufacturing. You’re not just building a component. You’re building a precision system that has to survive heat, vibration, and abuse for years—while shifting smoothly, quietly, and predictably across millions of units.

Aisin’s advantage is that it isn’t “good at one part.” It has decades of accumulated know-how across gears, shafts, and casings—the physical building blocks that have been refined through more than 50 years of automatic transmission development.

A true new entrant would need enormous capital for precision equipment, years of R&D to reach competitive performance, and then even more time to earn the kind of quality reputation that gets you onto an automaker’s platform. And even if you can build it, you still have to convince an OEM to bet its launch schedule and warranty costs on you.

Patents add another layer of friction. In the transverse automatic transmission market especially, Aisin has long been viewed as heavily protected by intellectual property, which has the practical effect of limiting how many viable “me too” competitors can show up with comparable products.

The EV transition does soften this force slightly, because eAxles are newer and the old transmission playbook doesn’t map perfectly. But even in EVs, the barriers don’t disappear—they shift. Manufacturing competence, global scale, and deep OEM relationships still matter. Aisin has all three, and most EV startups don’t.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Aisin buys key inputs like steel, aluminum, and rare earth magnets in global commodity markets. Its scale helps it negotiate, but it can’t negotiate away volatility. When raw material prices swing, Aisin feels it.

Vertical integration in some components reduces how much leverage any single supplier can exert. But electrification introduces new dependencies—battery-related materials and semiconductor chips—where supplier relationships and constraints look very different from the traditional ICE world. In other words, Aisin has leverage, but it’s operating in markets where leverage only goes so far.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

This is the big one. Toyota accounts for roughly 70% of Aisin’s sales, a level of concentration that gives Toyota real power in the relationship. The keiretsu ties and Toyota’s ownership stake reduce the odds of purely adversarial price pressure, but the structural imbalance remains: when one customer dominates, that customer has options you don’t.

Diversifying customers helps, and Aisin has made progress with automakers like BMW, Volvo, and Subaru. The counterweight in Aisin’s favor is switching cost. Automakers don’t swap transmissions—or drivetrain units—casually. Integration is expensive, validation takes a long time, and changing suppliers can ripple through the vehicle program. Once Aisin’s hardware is engineered into a platform, it tends to stay there.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH (and growing)

For Aisin, this isn’t theoretical. The substitute for an automatic transmission is the electric drivetrain—full stop. EVs don’t need multi-speed torque-converter automatics in the same way, and the value chain reorganizes around motors, power electronics, and integration.

The added pressure is that some EV makers—especially in China, with BYD often cited—are increasingly building proprietary drive systems instead of buying from suppliers like Aisin.

The good news is simple: there’s no substitute for moving a vehicle forward. The “job” still exists. That’s why Aisin’s pivot to eAxles matters so much—it’s an attempt to be the supplier of the substitute. The bad news is that the EV drivetrain battlefield may reward different strengths than the transmission era did, and Aisin’s legacy advantages may not translate perfectly.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a crowded, high-stakes arena. In transmission systems, Aisin competes with major global suppliers like ZF Friedrichshafen, Allison Transmission, and BorgWarner—companies with deep engineering benches and the balance sheets to keep investing.

ZF is the most obvious heavyweight rival, with its 8HP often treated as the benchmark for performance and shift quality. BorgWarner has pushed aggressively into EV drivetrains and remains especially strong in North America. And then there’s the new pressure point: Chinese competition, including vertically integrated automakers that can choose to build in-house rather than buy.

So Aisin is fighting on two fronts at once—defending a mature, brutally competitive transmission market while trying to win in an EV drivetrain market that’s still being defined.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Aisin AW was originally built to be Toyota’s dedicated source for rear-wheel-drive automatic transmissions. Over time, it expanded into front-wheel-drive and all-wheel-drive automatics too—exactly the kind of product breadth that lets a supplier keep factories full and costs low.

When you’re producing transmissions by the millions, the advantage compounds. R&D, specialized tooling, and quality systems are brutally expensive up front, but once they’re in place, every additional unit drives the average cost down. That scale is one of the reasons Aisin has been so hard to dislodge in the transmission world.

And it’s also the logic behind its EV push. Aisin has set a goal of reaching annual output of 4.5 million electric units by 2025. If it hits that kind of volume, it isn’t just “participating” in eAxles—it’s trying to bring the same scale playbook that made it a transmission giant into the electric era.

Network Effects: MODERATE (via Toyota ecosystem)

Aisin doesn’t have classic Silicon Valley-style network effects, where more users automatically make the product more valuable for everyone else. But the Toyota keiretsu creates something that rhymes with it: an ecosystem where the relationships themselves become an asset.

Aisin’s strength reinforces Toyota’s strength, and Toyota’s success feeds volume, learning, and stability back into Aisin. The 1997 fire made this visible to the world. It showed that, inside this system, the ties between suppliers can matter just as much as the tie to the lead firm. That collaborative reflex—companies mobilizing before anyone negotiates—acts like a kind of “relationship flywheel” that most supply chains simply don’t have.

Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

Counter-positioning is the trap where an incumbent can’t fully embrace a superior new model because it would undermine its existing one. Aisin is staring right at that trap.

Its legacy advantage—massive investment in automatic transmission manufacturing—could easily become its internal resistance point. EAxles, by definition, shrink the role of the multi-speed automatic. Even if Aisin can win in EV drivetrains, doing so means leaning into a future that cannibalizes what made it great.

Management has acknowledged the tension and has positioned the EV pivot as central to the company’s future. But the risk here is execution: it’s one thing to declare a pivot; it’s another to reallocate talent, capital, and attention away from a cash-generating core.

Switching Costs: HIGH

Once an automaker commits to a transmission for a vehicle platform, it’s effectively married to it for the life of that program. Integration takes years, testing and validation are exhaustive, and the cost of getting it wrong shows up in recalls, warranty claims, and brand damage.

That’s why automakers don’t casually switch transmission suppliers. Changing suppliers means redesign work, new validation cycles, and real launch risk. And when co-development is involved, the integration runs even deeper—engineering teams, manufacturing processes, and quality systems get intertwined. For Aisin, those switching costs are a moat.

Branding: LOW (B2B)

Aisin’s consumer brand is almost nonexistent. Drivers see Toyota, Lexus, BMW—not the supplier behind the transmission or drivetrain unit.

That’s normal for a Tier One industrial supplier, but it has consequences. It limits pricing power and makes the business heavily dependent on OEM relationships and trust. Aisin’s “brand” mostly lives where it matters for a supplier: in engineering departments, purchasing teams, and quality audits.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Some of Aisin’s advantages can’t be replicated. The Toyoda family connection is one of them—an irreplaceable link into the Toyota group that has shaped trust, collaboration, and long-term alignment across decades. Despite its scale, Aisin and the wider Toyota group still operate, in part, like an extended family business, with Toyoda family members holding board or chairman roles across the keiretsu.

Alongside that is the less visible resource: accumulated manufacturing know-how. Decades of proprietary processes, hard-earned lessons, and the ability to build complex components reliably at scale aren’t something a competitor can buy off the shelf.

Process Power: STRONG

If Aisin has a superpower, it’s process.

In a just-in-time environment, you don’t survive without world-class problem solving. Over time, the Toyota group has institutionalized that capability through practices like knowledge sharing and regular transfers of employees among group firms. The result is a culture where issues get surfaced quickly, attacked systematically, and resolved permanently.

The Toyota Production System DNA runs through Aisin’s operations, and the 1997 fire was the proof point: an operational response that looked almost impossible from the outside, but was actually the output of years of capability building.

And importantly, this kind of process power travels. Whether Aisin is building torque-converter automatics or eAxles, the discipline is the same: stable production, relentless quality, and a factory culture that can adapt fast when the unexpected happens.

XII. The Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case:

Toyota Concentration Risk: Roughly 70% of Aisin’s revenue still comes from Toyota. That’s not a customer relationship—it’s a dependency. If Toyota stumbles in the EV transition and loses share to Tesla, BYD, or fast-moving Chinese competitors, Aisin gets dragged down with it, no matter how well Aisin executes on the factory floor.

EV Transition Threatens Core Business: Aisin earned its position through half a century of transmission excellence. But battery-electric vehicles don’t need traditional transmissions the way internal-combustion cars do. The eAxle is the obvious pivot, but it’s a different battlefield. Chinese EV makers are increasingly vertically integrated. Tesla builds its own drivetrains. The supplier-friendly “buy it from a specialist” model that helped Aisin become a global transmission powerhouse may not play out the same way in EVs.

Slower EV Adoption by Toyota: Toyota has been more cautious on full battery-electric vehicles than many peers, continuing to invest heavily in hybrids and hydrogen fuel cells. If the market swings to pure EVs faster than Toyota expects, Aisin risks finding itself ramping eAxles later than competitors that have been scaling BEV hardware more aggressively.

Chinese Competition: BYD and other Chinese EV makers are building serious in-house powertrain capabilities, which makes them unlikely Aisin customers. At the same time, Chinese suppliers are moving quickly to offer competitive eAxle products—often at lower costs—tightening the squeeze on global incumbents.

Margin Pressure: Electrification demands heavy investment right as legacy transmission volumes may start to fall. If the transition is messy—years of overlap, pricing pressure, and uncertain EV demand—Aisin could end up in the hardest version of the pivot: high capex, declining legacy revenue, and EV volume that arrives slower than planned.

The Bull Case:

Execution Track Record: Aisin has a long history of navigating industry resets—aircraft engines to sewing machines to automatic transmissions to hybrid systems. The point isn’t that change is easy. It’s that this organization has done it before, repeatedly, and at scale.

eAxle Position: Aisin’s first-generation eAxles are already in production, with second- and third-generation systems in development and framed around ambitious efficiency and packaging goals. The BMW partnership is especially important here: it’s validation that Aisin’s EV relevance can extend beyond the Toyota ecosystem. Longer term, Aisin has set a very aggressive ambition—to become world number one in EV R&D by 2030.

Diversification Progress: Deals with Subaru and BMW matter not just for revenue, but for leverage. Each non-Toyota customer reduces concentration risk and forces Aisin to compete on open-market terms—exactly what it needs as the industry’s center of gravity shifts.

Manufacturing Excellence: Aisin’s real moat has always been process: manufacturing discipline, a quality culture, and fast, systematic problem solving. That advantage isn’t tied to one product category. If anything, it becomes more valuable when the industry is learning new technology under cost pressure—because execution is what separates “good prototype” from “reliable mass production.”

Hybrid Strength: Toyota hybrids continue to sell well globally, and hybrids still rely on sophisticated transmissions and power-split systems—precisely where Aisin has deep expertise. If the world takes longer than expected to fully electrify, Aisin’s hybrid-related business could remain a powerful earnings engine while the EV portfolio scales.

Financial Stability: Aisin reported an 18.5% year-over-year increase in net profit to ¥107.6 billion for the financial year ended March 31, 2025. That profitability gives the company breathing room—cash flow to invest through the transition, rather than being forced into a pivot from a position of weakness.

XIII. Key KPIs for Investors

If you’re trying to figure out whether Aisin is actually pulling off the EV pivot—or just saying the right things—there are three metrics that matter more than the rest.

1. Electric Unit Sales Volume and Mix

This is the scoreboard for the transition. Watch how many electric units Aisin ships each year—eAxles and hybrid transmissions—and how quickly those products become a bigger share of the powertrain business. In a healthy pivot, electric-unit volume climbs fast even if traditional transmission volume flattens or declines. Aisin’s own target of 4.5 million electric units annually is the benchmark to hold them to.

2. Non-Toyota Revenue Percentage

Aisin’s deep Toyota integration is both its superpower and its risk. With roughly 70% of revenue tied to Toyota, diversification isn’t optional—it’s strategic insurance. Track the share of revenue coming from non-Toyota customers, and pay special attention to where that growth is coming from. Wins in EV drivetrains with customers like BMW aren’t just incremental sales; they’re proof Aisin can compete outside the keiretsu “home field.”

3. Operating Margin Trajectory Through the Transition

Electrification is expensive. Aisin has to fund new platforms, new plants, and new capabilities while the legacy transmission business faces long-term pressure. Operating margin is the best single read on whether management is balancing that squeeze effectively. A strong transition keeps margins respectable even during heavy investment years. A weak one shows up as margin deterioration—investment rising just as the old profit engine fades.

XIV. Conclusion

Aisin Corporation is sitting at one of the most interesting inflection points in automotive history. For roughly eighty years, this “hidden giant” has repeatedly reinvented itself: from wartime aircraft-engine parts to postwar sewing machines, from Japan’s first domestically produced automatic transmission to the world’s largest transmission manufacturer, and from pure mechanical mastery to hybrid-era electrification.

Now comes the hardest reinvention yet.

The EV transition is a direct challenge to the thing Aisin became famous for. A half-century of automatic-transmission expertise doesn’t map perfectly onto a world where the center of gravity shifts toward electric motors, inverters, software controls, and integrated eAxle units. Even the keiretsu advantage—the relationship web that made the 1997 fire recovery possible—faces a modern stress test as cross-shareholdings unwind and open-market pressures rise.

And yet, Aisin isn’t walking into this fight empty-handed. Its edge has never been just “a great product.” It’s industrial capability: world-class manufacturing discipline, deep co-development muscle with Toyota, and a global footprint that lets it serve customers wherever they build. The BluE Nexus strategy and the three-generation eAxle roadmap give the pivot a clear destination, and the BMW partnership is a real signal that Aisin can win EV-relevant work beyond Toyota’s home field.

What decides the outcome is execution. Can Aisin scale electric units fast enough to matter? Can it diversify customers aggressively enough to reduce the Toyota dependency without losing the benefits of that ecosystem? And can it fund the transition without letting margins collapse during the messy overlap between old and new?

The next five years are likely to answer the question. Aisin could remain critical infrastructure for global mobility—quietly powering vehicles the way it always has—or it could become a textbook example of what happens when a dominant technology era ends.

For investors, that tension is the story. Aisin offers a front-row seat to the Toyota ecosystem and its hybrid strength, plus real upside if the EV pivot takes hold. The concentration risk is undeniable. But so is the company’s track record of adapting when it has to.

Every time you drive a Toyota, Lexus, BMW, or Volvo, there’s a good chance Aisin is doing the unseen work of turning energy into motion. Whether that stays true in 2035 depends on what happens now—in the engineering labs in Kariya, in the plants being retooled around the world, and in the strategic decisions made alongside Toyota as the rules of the industry get rewritten.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music