Isuzu Motors: Japan's Oldest Automaker and the Quiet Diesel Giant

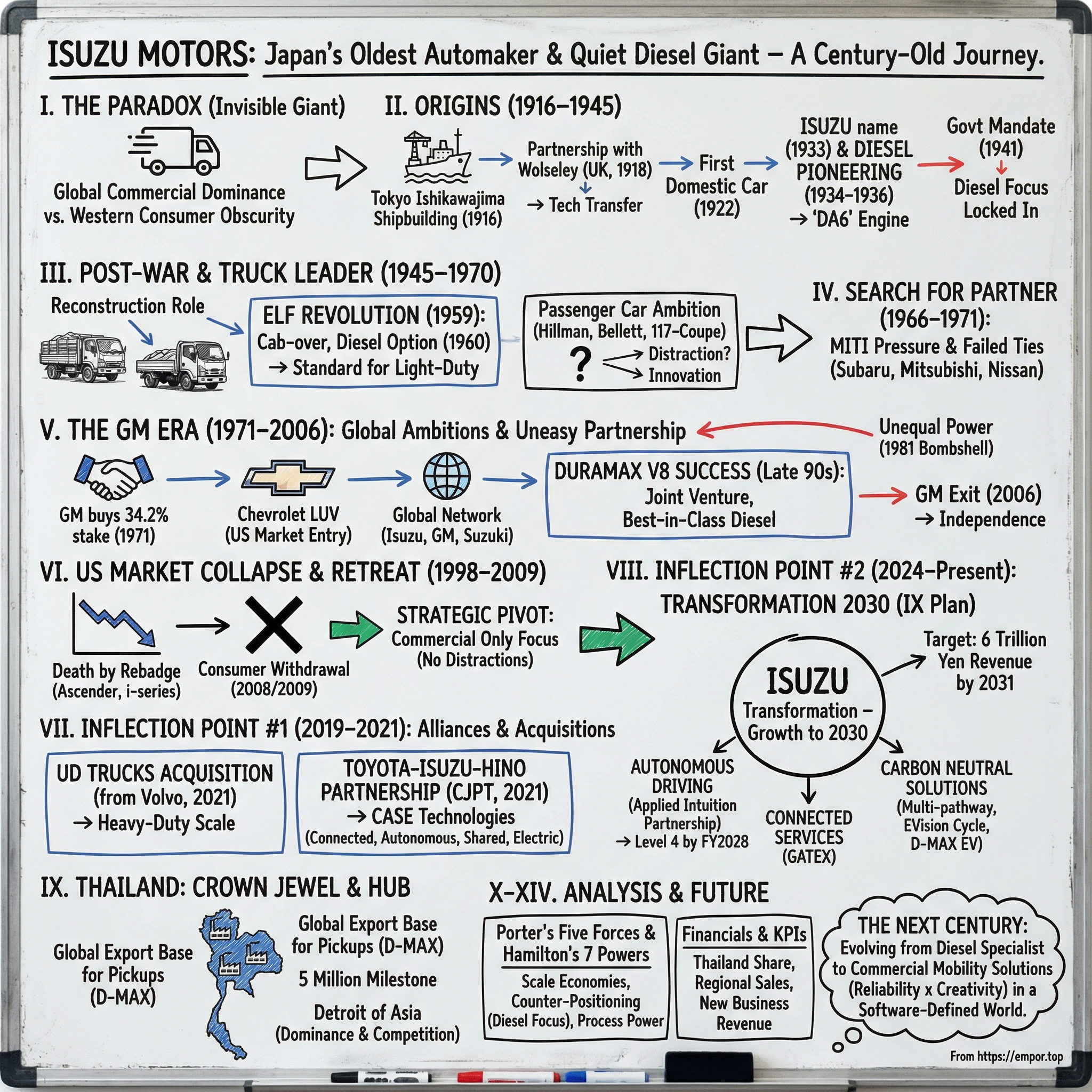

I. Introduction: The Paradox of the Invisible Giant

Picture yourself on a delivery route in Bangkok, slipping through humid streets at dawn. The truck beneath you isn’t a status symbol in Beverly Hills or a household name in Berlin. But out here, it rules the road the way Toyota rules the global imagination for passenger cars. Odds are, it’s an Isuzu D-MAX. And that’s the paradox: one of the most influential automakers on Earth is effectively invisible to most Western consumers.

Isuzu sells vehicles in more than 150 countries and regions. In Japan, its ELF light-duty truck is the category’s flagship, and in market after market it’s treated as the default choice—the global standard for getting work done. Yet ask an American car enthusiast about Isuzu and you’ll usually get a half-smile of recognition: maybe the over-the-top “Joe Isuzu” ads from the 1980s, maybe the Trooper SUV, maybe nothing at all. That gap—commercial dominance paired with consumer obscurity—isn’t an accident. It’s the result of deliberate strategy, and it might be one of the most instructive examples of focus in modern business history.

Isuzu was founded in 1916, making it the oldest of Japan’s automakers. It began as a bet by an industrial shipbuilder that the future wouldn’t belong only to ships. Over the next century, that bet didn’t turn Isuzu into another Toyota or Honda. It turned Isuzu into something quieter—and in many ways, more foundational: a company built around the engines, frames, and fleets that keep the global economy moving.

And then came 2021—a year that effectively reset Isuzu’s trajectory. In a matter of months, the company completed its acquisition of UD Trucks from Volvo, forged a new partnership with Toyota, and put a stake in the ground for where it wanted to go next, including an ambition to reach 6 trillion yen in revenue by 2031. These weren’t the moves of a company scrambling to survive. They were the moves of a company preparing for a world where logistics is being reinvented—by electrification, automation, connectivity, and the simple reality that there aren’t enough drivers to keep the old system running.

This is the story of how Japan’s oldest automaker became a global diesel giant by choosing the unglamorous lane and owning it. How a decades-long partnership with General Motors helped Isuzu expand—and also boxed it in. And how Isuzu is now trying to turn that hard-won commercial DNA into an advantage in the next era of trucking, where diesel expertise could be either a superpower or a trap.

II. Origins: From Shipbuilding to Japan's First Vehicles (1916–1945)

The Shipbuilding Connection

Isuzu didn’t start in a garage. It started in a shipyard.

In the years after the Meiji Restoration, Japan was sprinting into industrial modernity, and the Tokyo Ishikawajima Shipbuilding and Engineering Company became a cornerstone of that push. Its facilities on Ishikawajima Island near Tokyo built heavy ships—serious national-infrastructure stuff. But shipbuilding had a problem that every capital-intensive industry eventually runs into: it’s cyclical. When government contracts slowed, revenue didn’t just dip. It fell off a cliff.

So in 1916, leadership made a classic anti-cycle move: diversify. Not into something adjacent like rail or steel—but into automobiles, a category that barely existed in Japan. The catch was obvious: shipbuilders didn’t know how to design cars. Their solution was also obvious: find someone who did. Tokyo Ishikawajima partnered with the Tokyo Gas and Electric Industrial Company, which had the engineering capabilities to build vehicles. That collaboration became the root system for what would later be recognized as Japan’s oldest automaker.

Learning from the British

If you wanted to build cars in the 1910s without a domestic playbook, you borrowed one.

Japan had ambition, but almost no automotive expertise. So in 1918, the venture struck a technical cooperation agreement with Wolseley Motors Limited in the U.K. The deal granted exclusive rights to produce and sell Wolseley vehicles across East Asia, using knock-down kits—import the parts, assemble locally, learn the craft on the factory floor. It was the early auto industry’s version of training wheels, and it worked.

Then came 1922: Japan’s first domestically produced automobile, a Wolseley Model A-9, rolled out of production. It wasn’t just a win for one company. It was proof, at a national level, that Japan could make automobiles at all. The know-how gained from assembling British cars would ripple outward as Japan’s auto industry took shape.

The Isuzu Name and Diesel Pioneering

By the early 1930s, Japan’s government wanted more than assembly competence. It wanted independence from foreign technology. In 1933, Ishikawa Automotive Works answered with a new car: the “Isuzu,” built as a government standard model and named after the Isuzu River that runs past the Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture—Japan’s oldest shrine. The symbolism wasn’t subtle. This was industrial modernization wrapped in cultural continuity.

But the real identity-defining move came next. In 1934, the company formed a diesel research committee and committed itself to developing diesel engines—at a time when diesel technology wasn’t even fully commercially established in Europe and North America. Gasoline was the mainstream. Diesel was seen as loud, harsh, and mostly for industrial equipment. Betting the company’s engineering prestige on it was a swing.

In 1936, that swing connected: the company introduced the air-cooled 5.3-liter DA6 diesel engine, Japan’s first commercial diesel engines. It was a breakthrough that arrived just as Japan’s military buildup was accelerating demand for diesel-powered vehicles.

By 1941, the government didn’t just approve—it effectively crowned them, designating the company as the only manufacturer permitted to produce diesel-powered vehicles. It was an extraordinary mandate, and it locked Isuzu’s diesel expertise into Japan’s national industrial policy.

After the war, the company would be renamed Isuzu Motors Limited in 1949. But the blueprint was already set: lean into the unglamorous work, master the hard engineering, and turn practical performance into a long-term moat. That DNA was planted here, decades before Isuzu became the quiet backbone of fleets around the world.

III. Post-War Reconstruction & Becoming Japan's Truck Leader (1945–1970)

The Post-War Mission

In the rubble of post-war Japan, nothing moved without someone moving it.

Factories needed raw materials. Cities needed building supplies. Markets needed food. So when truck and bus production resumed in 1945—with the occupation authorities’ permission—Isuzu went straight back to work, restarting the TX40 and TU60 series and the Isuzu Sumida bus. The demand was immediate and overwhelming.

Isuzu’s trucks became a kind of unglamorous national infrastructure. They hauled construction materials, consumer goods, and everything in between. The company later described this era as the moment its passion for truckmaking took root. That’s not PR language. It’s an origin story. In a country trying to rebuild itself, reliability wasn’t a selling point. It was a public necessity.

Through the 1950s, Isuzu expanded to keep up. In 1958, it opened a new factory in Fujisawa, Kanagawa—an investment that would pay off quickly, because Isuzu was about to introduce the vehicle that would become its calling card.

The ELF Revolution

In 1959, Isuzu launched the Elf—and in doing so, set the template for light-duty trucking in Japan.

The Elf was Japan’s first full cab-over 2-ton light-duty truck. That design choice mattered. By putting the driver above the engine instead of behind it, Isuzu squeezed more cargo space into a small footprint—perfect for Japan’s narrow streets and tight loading docks. It was practical engineering aimed at a practical problem, which is basically the Isuzu way.

Then came the move that cemented the Elf’s reputation: in 1960, Isuzu added a diesel option, becoming the first light-duty truck in Japan to offer diesel power. It wasn’t flashy, but it was decisive. Diesel meant durability, operating efficiency, and long-haul stamina—traits that fleet operators cared about far more than styling.

Isuzu kept pushing the segment forward. In 1970, it introduced Japan’s first 3-ton truck. The following year, it added a small diesel engine to the model—and it became a breakout hit, helping “Isuzu’s light-duty diesel trucks” evolve into a worldwide standard.

And yes, the sales record reflects that. The Elf went on to lead Japan’s 2 to 3-ton cab-over segment for 30 straight years. By 1978, cumulative sales had passed one million units.

But what made the Elf endure wasn’t one killer feature. It was that Isuzu obsessed over the things that keep commercial vehicles earning: uptime, fuel efficiency, durability, and cost of ownership. In consumer cars, those are nice-to-haves. In fleet operations, they’re the business model.

Passenger Car Adventures: Ambition or Distraction?

And yet, even as Isuzu doubled down on trucks, it couldn’t resist the passenger-car dream.

It started in 1953 with the Hillman, built under license from Britain’s Rootes Group. Then came the Bellel in 1961 and the Bellett in 1963. The Bellett GT—known affectionately as the “Bele-G”—earned real enthusiasm among Japanese drivers who wanted something with personality.

In 1968, Isuzu made its most daring statement: the 117-Coupe, styled by Giorgetto Giugiaro. It was genuinely beautiful—European proportions, confident design, the kind of car that proved Isuzu could do more than make workhorses. It won awards and turned heads.

But here’s the tension that would define the company for decades: passenger cars were never the center of gravity. Even when Isuzu played in that arena, it played like Isuzu—leaning into the diesel niche. In 1983, long before diesel became fashionable in passenger vehicles, diesels accounted for 63.4% of Isuzu’s passenger car production.

The push and pull between passenger-car ambition and commercial-vehicle reality didn’t resolve itself yet. That reckoning came later, and it would be one of the most important strategic decisions Isuzu ever made. For now, heading into the early 1970s, Isuzu was about to meet the partner that would shape its destiny for the next 35 years.

IV. The Search for a Partner: Musical Chairs Before GM (1966–1971)

MITI's Consolidation Push

By the late 1960s, Japan’s auto industry was starting to look less like a crowded marketplace and more like a policy problem.

Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, MITI, worried the country had too many automakers to stand up to American and European giants. Their answer was consolidation: fewer companies, bigger scale, stronger exports.

For Isuzu, that pressure landed at exactly the wrong time. It was respected—especially in trucks—but it wasn’t big enough. And in passenger cars, it was in an awkward middle ground: models that were often a bit too large and a bit too expensive for the home market. Isuzu was innovative, but subscale. Profitable in commercial vehicles, uncertain in consumer ones. If MITI wanted the industry to pair up, Isuzu needed a dance partner.

The Failed Suitors

What followed was a rapid-fire sequence of alliances that, in hindsight, reads like an industry speed-dating montage.

In 1966, Isuzu entered a cooperation with Fuji Heavy Industries, Subaru’s parent, focused on joint sales and service. Publicly, it was framed as a first step toward a merger. Many assumed MITI would eventually push it over the line.

It didn’t last. By 1968, the relationship had unraveled, and Isuzu moved on to Mitsubishi—only for that agreement to end by 1969. In 1970, Isuzu tried again with Nissan. That, too, proved short-lived.

These weren’t random failures. Isuzu’s identity made it hard to absorb. It wasn’t a clean “truck company” you could bolt onto an existing passenger-car empire, and it wasn’t a competitive standalone carmaker you could scale into a national champion. Partners wanted pieces of Isuzu—its diesel know-how, its commercial-vehicle strength—but not necessarily the whole puzzle, including a passenger-car business that was never quite a natural fit.

Why GM Came Calling

Then, in September 1971, the music stopped—and General Motors took the seat.

GM didn’t show up out of goodwill. It showed up because Isuzu had something GM wanted: a credible foothold in Asian export markets, real diesel expertise, and products in categories GM could use without building them from scratch. And Isuzu, for its part, needed something badly: capital.

Despite being a truck-market leader, Isuzu had stretched itself thin developing new models. The spending left the company financially weakened enough that its bankers started looking for a solution—and began talking to competitors. That’s the moment GM stepped into: not at Isuzu’s peak, but when it had the least leverage.

In 1971, GM bought a 34.2 percent stake in Isuzu—enough to exert serious influence without taking outright control. GM saw a partner with export promise and a technology base it could plug into its global strategy.

For Isuzu, the deal looked like a rescue and a launchpad at the same time: funding to keep building, access to the U.S. market, and the credibility of association with the world’s largest automaker. The trade-off—how much strategic freedom Isuzu would quietly give up—would take decades to fully reveal itself.

V. The GM Era: Global Ambitions & Uneasy Partnership (1971–2006)

The Chevrolet LUV and Early Success

The GM–Isuzu partnership paid off fast. One of the core deal terms was straightforward: Isuzu would build vehicles that GM could sell in the United States. In 1971, Isuzu’s one-ton pickup crossed the Pacific wearing a new badge: the Chevrolet LUV, short for “Light Utility Vehicle.” By the end of 1972, GM had sold about 100,000 of them.

The LUV wasn’t just another pickup. It was smaller, more efficient, and more practical than the full-size American trucks of the era—exactly the kind of vehicle that looked “nice to have” in 1971 and suddenly looked essential once fuel prices spiked. When the oil shocks hit, the market swung toward efficiency, and Isuzu’s compact truck landed in the U.S. at exactly the right moment.

The Three-Way Dance: Isuzu, GM, and Suzuki

By the early 1980s, GM wasn’t just partnering with Isuzu. It was building a whole Japanese network.

The Isuzu P’Up became the first vehicle sold in the U.S. under the Isuzu name, a small but meaningful shift: Isuzu wasn’t only a behind-the-scenes manufacturer for GM anymore. Around the same time, Isuzu president Toshio Okamoto pushed a new collaboration with Suzuki—Japan’s small-car specialist—to develop a global small car for GM, known as the S-car.

In August 1981, the arrangement became formal: Isuzu and Suzuki exchanged shares, and GM took a 5% stake in Suzuki. This wasn’t corporate friendship. It was strategy—GM trying to secure options and capabilities as Japanese automakers grew into global threats.

The partnership expanded beyond Japan, too. In 1985, Isuzu and GM set up IBC Vehicles in the United Kingdom, another signal that both companies still believed the relationship could scale internationally.

The 1981 Bombshell

But under the surface, the relationship was never purely additive.

In a landmark 1981 meeting, GM CEO Roger Smith delivered a jarring message to Isuzu chairman T. Okamoto: in GM’s view, Isuzu had lost its favorable potential as a global partner.

Then came the twist. Smith didn’t end the partnership. Instead, he asked Okamoto to help GM buy a stake in Honda.

Okamoto was stunned, but Isuzu’s position was clear: GM was its largest shareholder, and refusing wasn’t really an option. The attempt went nowhere—Honda had no interest in an alliance with GM. But the episode revealed something Isuzu couldn’t unsee: the power in the partnership didn’t flow both ways. Isuzu depended on GM more than GM depended on Isuzu, and that imbalance would hang over the next decades.

The Duramax Success Story

And yet—when it came to diesel, Isuzu could still make GM look brilliant.

In the late 1990s, the two companies teamed up on a new diesel engine program that became one of the most successful products of the entire alliance. DMAX was announced in 1997 as a 60–40 joint venture run by General Motors and Isuzu. Production began in July 2000 at the Moraine, Ohio facility, where the first engine rolled off the line on July 17.

The product was the Duramax V8: a high-pressure common-rail, direct-injection diesel built for GM’s pickup trucks. The division of labor reflected the reality of the partnership. Isuzu handled the main engine design. GM handled the electronic fuel injection system. Together, they moved at a pace that surprised even GM internally—after a 1997 meeting between GM chairman Jack Smith and Isuzu’s Kazuhira Seki, development was accelerated to meet GM’s timeline. The Duramax went from idea to production in roughly 37 months, one of the fastest new engine programs GM had run at the time.

The result was immediate market impact. GM’s diesel pickup market share jumped to around 30% in 2002, up from roughly 5% in 1999—an outcome tied directly to having a diesel people trusted.

The milestones kept coming. In 2007, DMAX built its one-millionth Duramax V8 in Moraine. In 2017, it hit two million.

The Duramax story is a clean illustration of Isuzu’s core competence: diesel engineering that could meet—or beat—what American manufacturers could deliver on their own. The Duramax 6600 was a 6.6-liter, direct-injection, turbocharged diesel V8, and it quickly earned best-in-class recognition for quietness and smoothness. Not bad for a technology many consumers still associated with clatter and smoke.

Diesel Engine Empire

While GM got a headline product, Isuzu kept building its real empire: diesel engines, everywhere.

During this period, Isuzu became a major exporter of diesel powerplants, supplying engines used by Opel/Vauxhall, Land Rover, Hindustan, and others. By the early 2000s, Isuzu’s identity as a diesel specialist was so central that diesel engines made up about 85% of its total engine production by 2008. Across its long history, Isuzu’s global engine production exceeded 28 million.

This wasn’t a quirky preference. Isuzu understood something fundamental about commercial transport: it runs on diesel math. Fuel efficiency, torque at low RPM, and longevity aren’t features—they’re the economics of the job. While much of the industry treated diesel as a niche, Isuzu treated it as destiny.

GM's Exit

Still, the partnership was fraying.

GM had once owned as much as 49% of Isuzu, but it began cutting that stake down—disappointed by losses at Isuzu, and later pressured by its own financial needs. By 2006, GM sold its final 7.9% stake for $300 million, bringing the 35-year relationship to an end.

The breakup was surprisingly quiet for something so consequential. But for Isuzu, it was a reset: no more big-brother shareholder, no more automatic access to GM’s strategy. Just freedom—along with the responsibility to define what Isuzu would become next.

VI. The US Market Collapse & Strategic Retreat (1998–2009)

Death by Rebadge

Isuzu’s consumer business in America didn’t implode overnight. It drained away—year after year—until the company was basically selling echoes of itself.

Dealers disappeared first. Then the lineup shrank. By 2005, Isuzu’s U.S. light-vehicle range was down to two models: the Ascender, a rebadged GMC Envoy, and the i-series pickup, a rebadged Chevrolet Colorado. In practice, Isuzu in the U.S. was no longer a car company. It was becoming a medium-duty truck distributor with a passenger-vehicle side hustle held together by GM platforms.

The numbers made it undeniable. As of August 2006, Isuzu still had about 290 light-vehicle dealers in the U.S.—and those dealers were selling, on average, roughly two Ascenders per month. That’s not a sales channel. That’s a slow fade.

By 2007, Isuzu sold just 11,300 vehicles in total, down from 103,937 in 1999. Only about 7,000 of those were passenger vehicles—roughly split between pickups and Ascenders.

This was a stark end for a brand that once felt firmly part of the U.S. import scene. Isuzu had nearly a three-decade run selling affordable, dependable SUVs and trucks, and it even hit a high-water mark in 1986 with 127,630 cars and trucks sold. Names like Amigo, Hombre, and Rodeo weren’t niche trivia then—they were real products with real buyers. But by the mid-2000s, the brand’s identity in the U.S. had been reduced to whatever GM happened to be willing to lend.

Complete US Consumer Withdrawal

On January 30, 2008, Isuzu made it official: it would withdraw completely from the U.S. consumer market, effective January 31, 2009. It would continue to provide parts and support, but it would stop selling light-duty vehicles.

The logic was blunt. Sales weren’t there, and the future of the only two remaining vehicles depended on GM continuing the platforms underneath them. Isuzu told dealers in a conference call, then followed with a press release. The message was essentially: the foundation is crumbling, and we’re not rebuilding it.

And by then, Isuzu had very little left to stand on. It had once operated a joint-venture assembly plant in Indiana with Subaru, but that ended in 2002 amid financial strain. After that, Isuzu’s U.S. consumer business was almost entirely dependent on GM rebadging. GM, meanwhile, had already begun disentangling—selling its remaining roughly eight-percent stake in Isuzu in April 2006 and closing out a 35-year alliance.

The Strategic Pivot: Commercial Only

In a typical corporate obituary, this is where you say Isuzu “failed” in America.

But there’s another way to read it: as a retreat that saved the company from fighting a war it couldn’t win, in a category it didn’t need.

By the late 1990s, Isuzu had already dropped sales of sedans and compact cars in most markets due to plummeting demand, and in much of Asia and Africa it was known primarily for trucks of all sizes. The U.S. consumer withdrawal was brutal for dealers and embarrassing in headlines—but it didn’t touch the core of Isuzu’s business.

Crucially, it did not affect Isuzu’s commercial vehicle or industrial diesel engine operations in the United States.

Isuzu Commercial Truck of America, based in Anaheim, California, had imported its first trucks back in 1984. And years after the consumer exit, there were still over 300 commercial Isuzu dealers across the country serving fleets that cared less about brand image and more about uptime, cost, and reliability.

Because that’s the hidden truth: the U.S. consumer car market was punishing Isuzu with marketing costs, dealer-support overhead, and the endless treadmill of new model development. Commercial trucks were the opposite. Fleet buyers were rational. The product cycle was longer. The value proposition was measurable. And Isuzu, at its best, was built for that world.

So the consumer exit wasn’t just an ending. It was a clearing of the runway. With the distraction gone, Isuzu could concentrate on what it actually was: a commercial vehicle company with diesel in its bones—and a global opportunity that didn’t depend on winning hearts in American suburbia.

VII. Key Inflection Point #1: The Toyota Alliance & UD Trucks Acquisition (2019–2021)

The Volvo-UD Trucks Deal

By this point, Isuzu had cleared the deck. No more chasing consumer attention in the U.S., no more identity crisis about what business it was really in. And then, in December 2019, it made the kind of move that tells you a company isn’t just defending its niche—it’s expanding the map.

Isuzu signed a memorandum of understanding to acquire UD Trucks, the manufacturer long known as Nissan Diesel, from Sweden’s Volvo Group. It wasn’t a minor bolt-on. UD brought real weight in heavy-duty trucks, and it came with 14 years of experience operating inside Volvo’s system—technology, procurement, logistics, production, and sales.

The transaction ultimately valued UD Trucks at JPY 243 billion, or about $2.2 billion. Alongside the acquisition, Isuzu and Volvo signed binding agreements for a 20-year strategic alliance in commercial vehicles—designed to create scale for the next era and to cooperate on technology, both the proven stuff and whatever comes next.

The deal closed on April 1, 2021. And with that, Isuzu stopped being “the light- and medium-duty truck specialist” and became something bigger: a full-spectrum commercial vehicle manufacturer, now with heavy-duty capability in the portfolio.

The Toyota-Isuzu-Hino Partnership

The UD Trucks acquisition would’ve been enough for most companies to call 2021 a banner year. Isuzu wasn’t done.

In March 2021, Isuzu, Hino Motors, and Toyota Motor Corporation announced a new partnership aimed at commercial vehicles. The premise was simple and strategically loaded: combine Toyota’s CASE technologies—connected, autonomous, shared, and electric—with the commercial-vehicle foundations cultivated by Isuzu and Hino, and push those technologies into real-world logistics faster.

A month later, in April 2021, the partnership took corporate form. The three companies established Commercial Japan Partnership Technologies (CJPT), created to accelerate implementation and adoption of CASE across the transportation industry and support the push toward a carbon-neutral society. Suzuki and Daihatsu joined in July 2021, broadening the tent and signaling that this was meant to be an industry platform, not a one-off project.

There was capital behind the cooperation, too. Toyota acquired a 4.6% stake in Isuzu, and Isuzu planned to acquire Toyota shares for an equivalent value. In CJPT, Toyota held 80%, while Hino and Isuzu each held 10%, with the joint venture focused on areas like fuel cell and electric light trucks.

The Strategic Significance

Taken together, these 2021 moves were Isuzu reading the room correctly.

The commercial vehicle industry was entering a transformation as profound as anything in Isuzu’s century-long history. Autonomous driving, connected services, and electrification weren’t just engineering challenges. They were investment challenges—problems that demanded software talent, data infrastructure, and capital scale that no single Japanese truck maker could comfortably carry alone.

There was also some history here. Toyota had invested in Isuzu back in 2006 to collaborate on diesel engines, but the two companies ended their capital relationship in 2018. The 2021 partnership revived that connection—this time with Toyota looking to accelerate autonomous and electric capabilities, and Isuzu looking to ensure it wasn’t left trying to fund the future by itself.

The road wasn’t perfectly smooth. In 2022, the partnership hit turbulence when Hino was expelled from the group following a scandal involving falsification of engine data. It forced adjustments, but it didn’t erase the underlying logic: the future of commercial vehicles was going to be built through collaboration, and Isuzu had positioned itself at the center of Japan’s effort to do it.

VIII. Key Inflection Point #2: ISUZU Transformation 2030 (2024–Present)

The IX Plan

If 2021 was Isuzu repositioning its chess pieces, 2024 was Isuzu saying what game it planned to win.

In April 2024, the company unveiled its new mid-term business plan: “ISUZU Transformation – Growth to 2030,” known internally as “IX.” The headline wasn’t a new truck or a new engine. It was a new identity. Isuzu said it wanted to transform itself from a commercial vehicle manufacturer into a commercial mobility solutions company by 2030—one that solves customer and societal challenges through transport.

The plan rests on a simple phrase—“Reliability x Creativity”—and three concrete pillars where Isuzu intends to build new businesses: autonomous driving solutions, connected services, and carbon neutral solutions.

The financial ambition matches the strategic one. By FY2031, Isuzu is targeting net sales of 6 trillion yen and an operating income ratio of 10% or more. To get there, it committed to investing a total of 1 trillion yen in innovation by FY2031, aimed at accelerating carbon neutrality and digital transformation in logistics. And by the 2030s, Isuzu expects these growth areas to generate sales equivalent to 1 trillion yen.

The timeline is explicit, too. From FY2028, Isuzu plans to launch a new Level 4 autonomous driving truck and bus business—moving autonomy from “technology development” into “this is a thing customers can buy.”

The Applied Intuition Partnership

To pull that off, Isuzu went looking for a very different kind of partner.

In August 2024, it announced a strategic partnership with Applied Intuition, a Silicon Valley vehicle software supplier, to jointly develop Level 4 autonomous commercial trucks. The agreement is designed to accelerate development through a partnership strategy spanning up to five years.

This wasn’t autonomy for autonomy’s sake. Isuzu framed autonomous driving solutions as a new business pillar under IX, with the goal of launching Level 4 autonomous truck and bus businesses in Japan and North America in FY2028.

And the urgency is distinctly Japanese. Studies have shown truck drivers accounted for 34.3% of overwork-related deaths. In response, Japan revised its Labor Standards Law, capping annual work hours at 3,300 hours, including breaks. The concern is that fewer legal hours will collide with an industry already staring down a projected 36% decline in drivers by 2030. This is “The 2024 Problem,” and it’s not abstract—it threatens supply chains.

In that context, the promise of highway and hub-to-hub autonomy isn’t futuristic. It’s a pressure-release valve. Isuzu said the partnership would help enable commercialization of these operations in Japan, and noted that its heavy-duty trucks powered by Applied Intuition’s software are already operating on public roads in Japan today, with a safety operator.

Electrification and Sustainability

Autonomy is one leg of the transformation. Carbon neutrality is the other.

Under IX, Isuzu is pursuing what it calls a multi-pathway approach, working with various partners to promote carbon neutrality across its business. The company’s goal is to add carbon-neutral products to all product categories by 2030, and to support the shift to a carbon-neutral society by introducing price-competitive battery-electric vehicles and building the surrounding ecosystem. One example is the EVision Cycle Concept, a battery-swapping solution meant to make EV operations more practical for commercial fleets.

Isuzu has also begun turning that strategy into product. The first D-MAX EV has entered mass production. Production of the left-hand drive model for Europe has started, with shipments to major European markets planned for the third quarter of 2025. Production of the right-hand drive model is scheduled to begin at the end of this year, with sales expected to begin in 2026 in the UK.

IX. Thailand: The Crown Jewel and Global Manufacturing Hub

The Five Million Milestone

To understand Isuzu’s global business model, you have to understand Thailand.

What started as a manufacturing foothold in the 1960s grew into something much bigger: Thailand became the center of gravity for Isuzu’s pickup truck business—the place where the D-MAX isn’t just built, but scaled for the world.

Isuzu began building vehicles in Thailand in 1963 through the Isuzu Assembling Plant. In 1966, it established Isuzu Motors (Thailand) and put down deeper roots with manufacturing in Samut Prakan Province. Then the machine really started turning: in 1974, IMCT began manufacturing pickup trucks for the Thai market.

From there, volumes climbed steadily. Over 56 years and 11 months of production, IMCT reached a cumulative five million pickup trucks built. Exports began in 1999—first to Australia, then outward to other overseas markets. And in 2002, Isuzu made a decisive shift: pickup production for export was fully relocated from Japan to Thailand.

That’s when Thailand stopped being “a” plant and became the mother plant—supplying Isuzu pickups to more than 100 countries and regions.

The scale is substantial. IMCT operates two assembly plants—the Samrong Plant in Samut Prakan Province and the Gateway Plant in Chachoengsao Province—together capable of producing 385,000 vehicles per year, supported by about 6,000 employees.

Thailand is also one of the world’s biggest battlegrounds for one-ton pickups, and for Isuzu it has been the cornerstone market. In fiscal 2022, Isuzu sold roughly 340,000 units globally. Of those, the D-MAX accounted for around 180,000 units in Thailand—about a 45% share.

Why Thailand Dominates

Thailand’s rise as the “Detroit of Asia” for pickup trucks isn’t an accident—and it fits Isuzu perfectly.

The Thai government has long offered favorable tax treatment for pickup trucks compared to passenger vehicles, which helped create massive domestic demand. Thailand’s location at the center of ASEAN makes it a natural export hub. And after decades of Isuzu investment, the country developed exactly what high-volume auto manufacturing needs: a mature supplier base and a workforce trained around the rhythms and requirements of Isuzu production.

That combination made Isuzu’s Thailand bet one of its most successful. By 2002, the company had shifted its pickup production base from Fujisawa, Japan, to Thailand—an implicit statement that this wasn’t just a low-cost alternative. It was the strategic heart of the business.

Even so, dominance doesn’t mean permanence. The D-MAX has continued to lead model-by-model in Thailand, but competition has intensified. In 2023, its share moved from 21.4% to 16.4%, and its sales advantage over its main rival, the Toyota Hilux, narrowed—from 36,000 units to 12,700. The market itself has also been under pressure, with economic weakness and EV competition weighing on demand.

And yet, even with Thailand’s light commercial vehicle market sluggish since 2023, Isuzu has continued to hold a high share—watching closely, and waiting for the cycle to turn.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE

Building commercial trucks isn’t like launching a consumer gadget. You need enormous up-front capital, factories that can hit industrial-grade quality at scale, dealer and service coverage across countries, and the ability to clear a maze of safety and emissions regulations.

Isuzu also has a barrier that’s hard to fake: a century of diesel and commercial-vehicle know-how, plus the parts-and-service infrastructure fleets depend on. In trucking, the product isn’t just the truck. It’s the promise that someone can keep it running for years.

But the industry’s transition to EVs cracks the door open. New entrants like BYD and other Chinese manufacturers can bypass a lot of internal combustion history and compete on batteries, software, and cost. And even with delays, Tesla’s Semi shows that outsiders are still aiming at the heart of freight.

So the real question isn’t whether Isuzu’s moat existed. It’s whether that moat carries over to an electric, software-heavy future—or whether diesel mastery becomes baggage.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

In the diesel era, many components have gradually become more interchangeable as the technology matured. Isuzu’s position is stronger than most because it’s not just a buyer of engine technology—it’s a producer, and historically a supplier to other manufacturers. That vertical integration gives it leverage that pure assemblers don’t have.

EVs change the balance. Batteries and key electric components introduce supply chains where long-standing relationships matter, and where the industry is still consolidating around a smaller set of critical suppliers. Isuzu’s partnerships—especially with Toyota and Volvo—help here by adding scale and procurement muscle, but the dependency risk is still higher than it was in a diesel-dominated world.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Commercial customers buy like CFOs, not like car enthusiasts.

Fleet operators obsess over total cost of ownership: fuel, maintenance, downtime, resale value, and even how easy a truck is for drivers to live with. That makes buyers sophisticated and price-sensitive, and it limits how much pricing power any manufacturer can sustainably hold.

For Isuzu, that’s a double-edged sword. It helps because the company’s brand is built on measurable strengths—reliability and efficiency. But it also means loyalty is conditional. If a competitor delivers better economics, fleets can and will switch.

There are some switching costs—driver familiarity, maintenance routines, parts stocking, and shop training—but they’re rarely strong enough to create true lock-in.

4. Threat of Substitutes: HIGH (Long-term)

Over the long run, the substitute threats are real and expanding: electric trucks from rivals like Tesla, BYD, and Daimler; autonomy-enabled delivery models; and, in some corridors, shifting freight to rail or sea.

In the near term, diesel still has structural advantages in heavy-duty work where range, payload, and refueling speed matter—and where charging infrastructure isn’t ready to replace liquid fuel at scale. But the direction of travel is clear, and timelines are compressing.

Isuzu’s multi-pathway stance—battery electric, fuel cell, and improved diesel—is essentially an admission that no one can perfectly call the winning energy mix yet. The threat isn’t one single substitute. It’s that the definition of “the best way to move freight” is changing.

5. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife fight, and the competitors are well-funded.

In Japan, Isuzu faces Hino (Toyota-backed, despite the recent scandal fallout), Fuso (Daimler), and it now owns UD Trucks—adding scale, but also creating internal complexity in managing overlapping segments. Globally, it’s up against giants like Daimler, Volvo, PACCAR, and TRATON, plus increasingly formidable Chinese OEMs including FAW and Dongfeng.

And the GM relationship is a reminder of how quickly partners can become competitors. Isuzu and GM co-developed midsize pickups for Asia—work that fed directly into vehicles like the Isuzu D-MAX and the international Chevrolet Colorado. But as strategies diverged, the partnership ended. In commercial vehicles, collaboration is common. So is the moment it stops being convenient.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Isuzu’s scale isn’t the kind most consumers notice, because it’s concentrated in the unglamorous categories that keep economies running. Take the ELF: by the time you’re selling millions of units of a workhorse platform across well over a hundred countries, you’ve earned a set of cost advantages that smaller competitors simply can’t copy.

That focus matters. Isuzu didn’t try to be everything to everyone. By staying centered on commercial vehicles instead of spreading itself across passenger cars, it concentrated its volume, learning, and purchasing power into the segments where scale actually compounds.

Thailand is the cleanest example. By turning a single manufacturing hub into the global export base for pickups sold across 100-plus countries, Isuzu didn’t just lower costs. It created the kind of repeatable, high-volume system where every incremental improvement has global impact.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Trucks don’t get consumer-style network effects where “everyone uses it so I should too.” But they do get something close: service density.

A commercial vehicle is only as valuable as its uptime, and uptime depends on parts availability, trained technicians, and a dealer network that can handle repairs fast. As Isuzu’s installed base grows, it becomes more rational for dealers to invest in Isuzu capability—and that, in turn, makes Isuzu more attractive to the next fleet buyer. It’s not viral growth, but it is a reinforcing loop.

Isuzu’s connected-vehicle efforts could deepen this over time. If platforms like the GATEX system under the IX strategy become widely adopted for fleet data, maintenance planning, and operations, the value of being “inside” that ecosystem could rise with every additional vehicle on it.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG (Historical)

Historically, Isuzu’s biggest strategic edge came from zigging while others zagged.

While competitors chased the broadest possible consumer lineup, Isuzu leaned hard into diesel and commercial applications. That commitment looked narrow at times, and its passenger-car retreat was undeniably painful in the short term. But it also freed the company to become exceptional at the one thing fleets actually pay for: dependable work at predictable cost.

The open question is whether Isuzu can find a modern version of that same move. Autonomous trucking might be the next counter-positioning opportunity. Or it might reward software-first players in a way that makes legacy manufacturing excellence less decisive than it used to be.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Fleet buyers can switch truck brands, but it’s not frictionless.

Changing platforms means retraining drivers, updating maintenance routines, stocking different parts, and retooling service relationships. For large operators replacing vehicles on multi-year cycles, those costs are real—but usually manageable.

Where Isuzu benefits is in the less-visible switching cost: trust. Fleet managers know what reliability feels like in day-to-day operations, and they know what failure costs. Moving away from a proven platform to an unproven one can create operational risk that doesn’t show up neatly in a purchase price comparison.

5. Branding: STRONG (in Commercial)

Isuzu’s brand power doesn’t look like Toyota’s or Ford’s. It isn’t built on consumer aspiration. It’s built on reputation among the people whose paychecks depend on vehicles starting every morning.

Among diesel owners and fleet operators, Isuzu engines are widely regarded as durable and hard to kill. The common shorthand is “bulletproof,” and the confidence comes from lived experience—engines that, with regular maintenance, often run for hundreds of thousands of miles.

That doesn’t translate into mainstream consumer awareness, but for Isuzu it doesn’t have to. The brand premium is narrow, but it’s meaningful exactly where the company plays: commercial buying decisions driven by uptime and long-term economics.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Isuzu’s deepest “resource” isn’t a patent or a mine. It’s accumulated diesel engineering capability—decades of institutional knowledge that’s difficult to replicate quickly.

The Duramax story is a good illustration. GM had enormous resources, yet chose to partner because Isuzu’s diesel expertise could deliver what GM wanted on the timeline it needed. That’s a real edge, and it’s been built over generations.

The uncomfortable part is the transition. Diesel mastery doesn’t automatically become battery mastery, and it doesn’t automatically become autonomy mastery. Electric powertrains and autonomous systems pull from different talent pools and reward different engineering cultures.

7. Process Power: STRONG

Isuzu has spent decades refining how to build commercial vehicles efficiently and consistently—process discipline that shows up in quality, productivity, and cost structure. Thailand, again, is the proof: a mature system that’s been optimized over years of high-volume production.

But process power has a boundary. Traditional manufacturing excellence doesn’t guarantee leadership in a software-intensive world where iteration speed, data, and validation loops can matter as much as factory throughput.

So the bet embedded in IX is that Isuzu can keep its manufacturing advantage—and pair it with partners and capabilities that help it compete in the parts of the stack where its historic strengths don’t naturally extend.

XII. Financial Position and Key Performance Indicators

Recent Financial Performance

For all the talk of strategy—alliances, autonomy, electrification—the scoreboard is still the financials. And in the most recent results, you can see both Isuzu’s resilience and the pressure points that come with being a global, cost-sensitive industrial business.

In the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Isuzu reported annual revenue of 3.24 trillion yen, down 4.46% year over year.

Profit fell by 64.0 billion yen versus the prior fiscal year. Management attributed the decline to weaker overseas unit sales and higher materials and other costs, which more than offset the benefits from price realization.

The first half of fiscal 2026 (the six months ended September 2025) showed a mixed picture. Revenue in Japan was 661.3 billion yen, up 11.9% from the same period a year earlier, while revenue in the rest of the world was 976.0 billion yen, up 1.4%. Operating profit came in at 104.6 billion yen, down 21.1% year over year, pressured by foreign exchange effects, a weaker destination mix in overseas markets, the impact of U.S. tariffs, and higher material costs.

Operationally, volumes were up. Total vehicle sales in Japan and overseas for the six months ended September 30, 2025 increased by 33,613 units, or 13.6%, to 280,364 units. Vehicle unit sales in Japan rose by 3,009 units, or 8.3%, over the same period.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you’re trying to understand whether Isuzu’s story is just “a great truck company navigating a tough cycle,” or “a great truck company successfully reinventing itself,” three KPIs do most of the work:

1. Thailand Market Share: Thailand is the crown jewel. Share in the pickup market is a real-time signal of brand health and competitive position in Isuzu’s most important volume arena. The recent slide from 21%+ to the mid-teens is something to watch closely, even as the company emphasizes profitability over chasing volume.

2. Commercial Vehicle Unit Sales by Region: Isuzu’s risk and upside are both geographic. Tracking unit sales across Japan, Thailand/Asia, and other regions tells you how concentrated the business is—and where growth is (or isn’t) showing up. The IX plan targets 850,000+ units by FY2031, and getting there requires sustained growth in an environment that isn’t making it easy.

3. New Business Revenue Contribution: This is the transformation litmus test. Under IX, Isuzu is aiming for 1 trillion yen in revenue from autonomous driving, connected services, and carbon-neutral solutions in the 2030s. Today, that contribution is still near zero. If that number starts to move meaningfully, it’s a sign Isuzu is building a second engine—not just modernizing the first.

XIII. The Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Japan’s “2024 Problem”—the driver shortage colliding with new overtime restrictions—turns autonomous trucking from a shiny future concept into a practical necessity.

The reforms that took effect in April 2024 capped truck-driver overtime at 960 hours per year. The intent is clear: improve safety and working conditions. The consequence is also clear: fewer drivable hours in a system that was already stretched.

Nomura Research Institute projected that by fiscal 2030, Japan could face a major shortfall in truck drivers—on the order of a third fewer drivers than needed. Freight demand, meanwhile, is expected to hold roughly steady, slipping only slightly from fiscal 2020 to fiscal 2031. In other words, the work doesn’t disappear, but the labor does.

That’s the backdrop for why Isuzu’s Applied Intuition partnership and its Level 4 ambitions matter. If autonomy can reliably move freight in a market like Japan—tight infrastructure, strict regulation, intense operational requirements—then it becomes something the logistics system will eventually pay for. The company that makes autonomous trucking real, not theoretical, could earn an outsized position in a supply chain that needs relief.

There’s also a more old-fashioned bull argument: resilience. Isuzu has lived through currency swings, recessions, and the end of its long GM relationship without an existential crisis, largely because it sits in commercial replacement cycles. Fleets still replace vehicles. Parts and service still matter. Uptime still wins bids. That’s a steadier foundation than consumer fashion.

And strategically, Isuzu has stacked the deck with partners: Toyota for advanced technologies, Volvo’s alliance alongside the UD Trucks acquisition for heavy-duty scale and capabilities. Together, those relationships give Isuzu a way to fund and build the next era without simply handing over the steering wheel.

The Bear Case

Isuzu’s greatest strength could become its biggest exposure: diesel.

The company’s identity and engineering heritage are built on diesel expertise, but the long-term direction of regulation and customer preference points toward electrification. Isuzu’s multi-pathway approach buys time and flexibility, but if the world moves faster than expected—especially in urban delivery and regulated markets—diesel-centric advantage can turn into stranded competence.

Then there’s concentration risk. Thailand is a crown jewel, but it’s still concentration. If the Thai pickup market stays weak for longer, or if low-cost competitors—especially from China—take meaningful share, Isuzu’s most important profit engine takes the hit. And because Isuzu has intentionally stepped away from North American consumer vehicles, it doesn’t have an easy “flip the switch” diversification option if Southeast Asia turns against it.

Autonomy is another risk, even if it’s also the opportunity. Building Level 4 trucking is expensive, and Isuzu is smaller than the best-capitalized players in the space, from Tesla to Daimler and others. The Applied Intuition partnership helps, but partnerships can change, priorities can diverge, and Isuzu has limited ability to replicate that capability fully in-house if the relationship ever weakens.

And there’s a sobering footnote to the Isuzu–GM era: according to financial filings, Isuzu wound down its investment in DMAX in May 2022, leaving the company wholly owned by GM. So even the Duramax chapter—Isuzu’s most visible North American diesel win—no longer creates an ongoing upside for Isuzu shareholders.

Material Regulatory and Legal Considerations

Commercial vehicles sit directly in the crosshairs of emissions regulation, and that pressure is only increasing. Euro 7 standards in Europe, California’s Advanced Clean Trucks mandate, and Japan’s carbon neutrality targets all force heavy R&D spend and fast execution. Falling behind isn’t just a margin problem—it can become a market-access problem.

And the sector has seen how quickly compliance issues can spiral. Hino’s engine data falsification scandal, and its subsequent expulsion from CJPT, is a reminder that reputational damage in commercial vehicles isn’t limited to bad press—it can fracture partnerships and derail strategy. Isuzu hasn’t faced similar allegations, but the lesson remains: in this industry, regulatory credibility is a core asset, and losing it can be catastrophic.

XIV. Conclusion: The Quiet Giant's Next Century

Isuzu is heading into its second century as something rare in the auto industry: a company that chose to be a specialist, stayed a specialist, and built global importance without becoming a global household name. It walked away from the world’s biggest consumer-car stage, stopped trying to win attention, and doubled down on what it could be best at—commercial vehicles and the economics of uptime.

Now it’s doing something even harder. The company that made its name on diesel durability is trying to lead through a transition defined by software, electrification, and automation. The IX plan is the clearest signal yet that Isuzu doesn’t see this as a product refresh cycle. It sees it as a reinvention—moving from “we build trucks” to “we run logistics mobility,” with autonomy, connected services, and carbon-neutral platforms as the new growth engine.

That creates the core question hanging over the story: can Isuzu evolve into a commercial mobility solutions company without losing the trait that made it trusted in the first place—reliability? The optimist’s view is that reliability is exactly the brand you want in autonomy and fleet electrification, because the stakes are higher and the buyers are unforgiving. The skeptic’s view is that the next moat will belong to software-native players who treat trucking less like manufacturing and more like compute on wheels.

Either way, Isuzu’s record is unusually consistent. Its history has rewarded focus over sprawl, execution over hype, and deep relationships with commercial customers over mass-market brand building. Those habits could be a compounding advantage in the decade ahead. Or they could be the wrong toolkit for a world where the bottleneck shifts from engines and factories to data and autonomy stacks.

For investors, the bet is straightforward: physical logistics remains non-negotiable in a digital economy. Goods still have to move, and fleets still have to run. The open question isn’t whether trucks matter. It’s whether Isuzu’s way of building—and increasingly, operating—them can stay ahead of the transition risks.

And if that sounds like a long wait, it fits the company. Isuzu has never tried to win the next quarter. It’s always played for the next era.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music