Yokohama Financial Group: Japan's Oldest Banking Heritage and Regional Powerhouse

I. Introduction: The Last Standing Giant of Japanese Regional Banking

Picture Yokohama’s harbor in the late 1860s. Foreign ships sit just offshore. Silk merchants crowd the waterfront. Samurai watch the new arrivals with a mix of suspicion and curiosity. After more than two centuries of relative isolation, Japan was being pulled—fast—into the currents of global trade. And in the middle of that upheaval, where money suddenly had to move as quickly as goods, modern Japanese finance got its start.

The Bank of Yokohama traces its roots back to 1869, when Dai-Ni Bank began operations as Yokohama Bank (横浜為替会社). By that lineage, it stakes a bold claim: the longest history of any Japanese bank. In this case, it isn’t marketing flourish—it’s a reflection of how early Yokohama became Japan’s testing ground for Western-style commerce.

Jump to December 2025 and that same institution—born at the edge of a newly opened nation—has become the biggest regional bank in Japan. And it’s now wearing a name designed to make that identity unmistakable. Formerly known as Concordia Financial Group, Ltd., the holding company renamed itself Yokohama Financial Group, Inc. in October 2025.

On paper, a name change is just stationery and signage. In reality, this one was the capstone of a strategy: nearly a decade of consolidation that turned a set of regional lenders into the country’s leading regional banking group. Today, the group manages more than 20 trillion yen in deposits and 16 trillion yen in loans—scale that puts it firmly among Japan’s most consequential banking players.

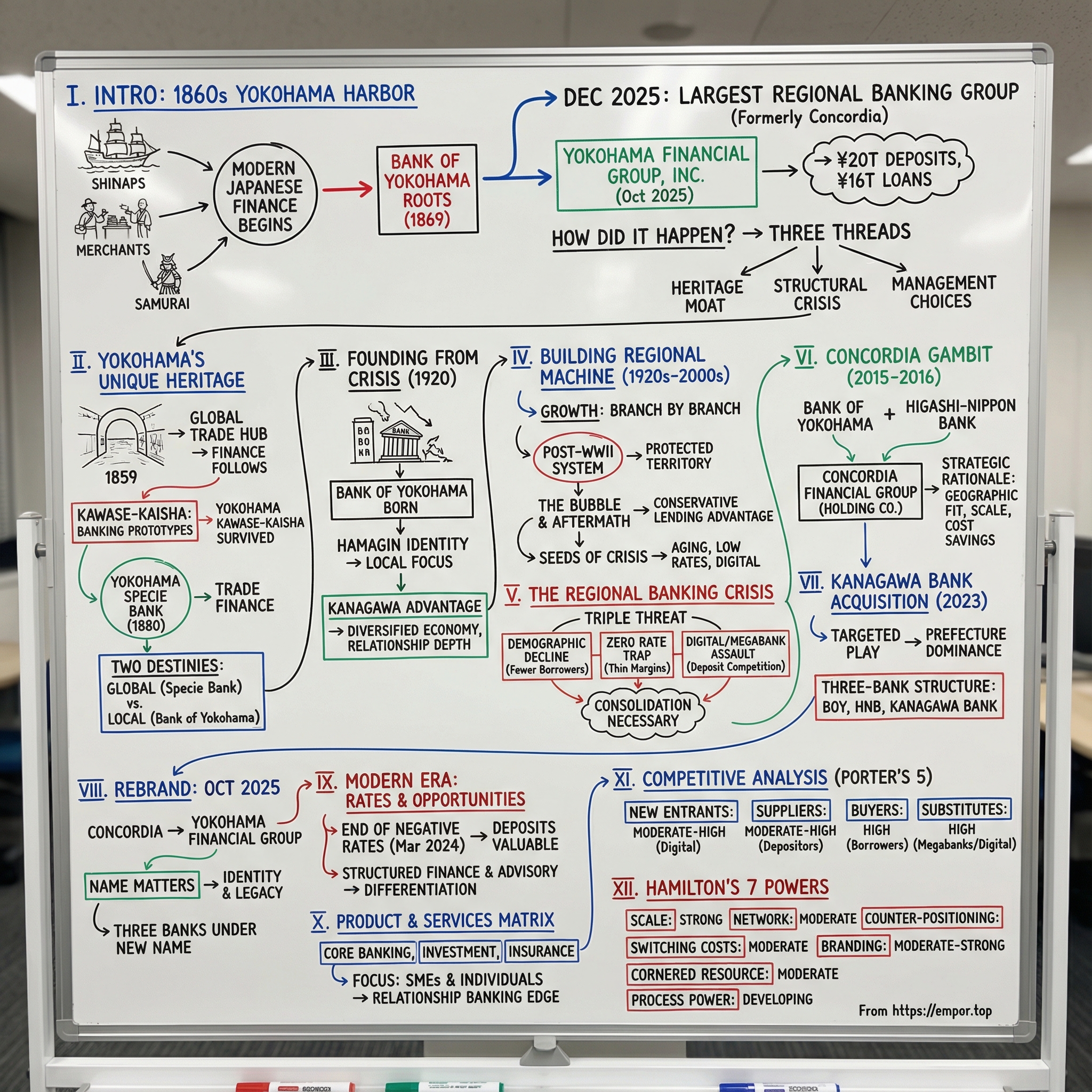

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a regional bank—shaped by crisis, tied to one prefecture, and operating in one of the toughest banking environments in the world—become Japan’s largest regional banking group? And what does its consolidation spree reveal about where Japanese regional banking is headed next?

To answer that, we need to follow three threads at once: Yokohama’s unusual heritage and the moat it created; the slow-moving, structural crisis squeezing regional banks across Japan; and the management choices that turned defensive mergers into an offensive platform. And to really understand it, we have to start where Japanese modern finance did—not in a boardroom, but on the pier.

II. The Birth of Modern Japanese Banking: Yokohama's Unique Heritage

The Port That Changed Everything

The Port of Yokohama officially opened to foreign trade on June 2, 1859. Over the Meiji and Taisho periods, it exploded into a hub for raw silk exports and technology imports—a place where Japan’s old economy met the modern world, face to face.

And that’s the key to why modern banking took root here first, instead of in the much bigger commercial centers of Edo (Tokyo) or Osaka. Yokohama had been a small fishing village until Commodore Matthew Perry and his U.S. Navy ships forced the shogunate to open ports to foreign trade. The Tokugawa leadership chose Yokohama precisely because it seemed contained—isolated enough to keep “disruptive” foreigners away from Japan’s core arteries.

It didn’t work out that way. The defensive choice became an accelerant. Yokohama turned into Japan’s front door to the West, and then into a proving ground for modernization itself. Some of the “firsts” that symbolized this new era showed up here early: Japan’s first daily newspaper (1870), gas-powered street lamps (1872), and the country’s first railway.

Where trade flows, finance follows. Foreign banks, including HSBC, established a presence in Yokohama by 1866 to help fund Japan’s fast-growing international commerce. But that created an obvious problem for a nation trying to control its own destiny: if your trade runs through foreign banks, your economic lifeline does too. Japan needed domestic financial infrastructure, built for this new kind of economy.

The Kawase-Kaisha: Prototypes of Modern Banking

Right after the Meiji Restoration, merchants in major trading centers began experimenting with prototypes of modern commercial banks known as kawase-kaisha. These institutions were authorized to issue banknotes, and the Yokohama kawase-kaisha stood out because it was built to serve a very specific engine: the booming foreign trade pouring through the port.

In practice, the kawase-kaisha lived in an awkward middle ground. They weren’t traditional money-changers, but they weren’t fully Western-style banks either. They had to operate amid volatile exchange rates—especially the constant tension between silver and gold—while fighting counterfeiting and navigating a government still in the middle of consolidating power.

Most of them didn’t survive. In fact, all of the kawase-kaisha went out of business except one: the one in Yokohama.

That survival wasn’t an accident. It reflected the kind of commercial sophistication that had formed around the port. Yokohama’s merchants were learning, in real time, how international trade actually worked: how to manage currency risk, how to price uncertainty, and how to build relationships with foreign counterparties. Those capabilities became an enduring advantage.

Around the same time, Japan was also trying to formalize the system. In 1870, Hirobumi Ito—then a senior Ministry of Finance official who had been sent to the United States to study American monetary and banking systems—submitted a proposal recommending a monetary and banking system based on the gold standard.

The Yokohama Specie Bank: A Parallel Tale of Financial Innovation

If Yokohama was Japan’s financial laboratory, the clearest proof is a second institution born in the same city: the Yokohama Specie Bank (横浜正金銀行). Founded in 1880, it went on to dominate Japan’s trade finance market for decades.

From day one, it carried a uniquely Yokohama DNA: a hybrid of private initiative and state involvement. The bank was created through collaboration between private individuals and the Japanese government. Early management came from private investors, while bureaucrats appointed by the Okura-sho (the Finance Ministry) sought to exert control.

The results were enormous. By the 1920s, the Yokohama Specie Bank handled nearly half of Japan’s foreign exchange transactions tied to exports and imports. By 1929, it was Japan’s largest and most profitable bank aside from the Bank of Japan. Eventually, it was reorganized and rebranded as the Bank of Tokyo—one of the predecessor entities of MUFG Bank, now one of Japan’s megabanks.

So why bring up a different bank in the middle of Yokohama Financial Group’s story? Because it shows what Yokohama produced: deep expertise in the machinery of modern finance, built under pressure, in the one place in Japan where global trade was unavoidable.

But it also highlights the fork in the road that Yokohama’s financial institutions took. While the Specie Bank built itself around international trade finance and ultimately fed into a megabank lineage, the institution that would become the Bank of Yokohama leaned the other way. It anchored itself in the local economy—manufacturers, merchants, and the small businesses that made up the fabric of Kanagawa Prefecture.

Two banks, same birthplace, two very different destinies. And that contrast points to one of the enduring truths of banking: scale helps, but it isn’t everything. Focus, relationship depth, and a real understanding of the customer base can be just as powerful—especially when the world turns against you.

III. Founding from Crisis: The Birth of Bank of Yokohama (1920)

When Banks Collapse, New Institutions Rise

The Bank of Yokohama was founded in 1920 to serve customers in Kanagawa Prefecture and southwestern Tokyo. But it wasn’t born out of ambition. It was born out of cleanup.

In the years after World War I, Japan’s economy swung hard. The wartime export boom had inflated balance sheets and encouraged banks to lend aggressively. Then the boom faded. As the economy contracted, the weak spots showed up fast: loans that looked safe in good times turned sour, and several banks in the Yokohama region collapsed.

So the solution wasn’t to start from scratch. It was to consolidate what was left.

Bank of Yokohama emerged as a stronger, better-capitalized institution built from the wreckage of those failures. In a moment when depositors had just learned, painfully, what instability looked like, “solid” wasn’t a branding message. It was the product. And from the beginning, the bank’s mission was simple: be the dependable financial spine of the local economy.

The Hamagin Identity

Locals call it Hamagin (浜銀) for short—a small nickname with a big signal. “Hama” evokes the port and shoreline; “gin” means bank. Together, it says: this is Yokohama’s bank.

Headquartered in Yokohama, the bank operated mainly in Kanagawa Prefecture and southwestern Tokyo. That focus could have looked limiting next to the national ambitions of Tokyo-based banks. But Bank of Yokohama leaned into it. It didn’t try to be everywhere. It tried to be indispensable where it was.

That meant deep familiarity: not just knowing the industries in the region, but knowing the actual businesses. Who was expanding. Who was struggling. Which suppliers mattered. Which customers paid on time. It was banking built on memory.

The Kanagawa Advantage

Kanagawa turned out to be an unusually good place to build a regional bank. It sits right next to Tokyo—close enough to benefit from the country’s biggest economic engine, but distinct enough to have its own industrial identity. Yokohama’s port remained a commercial artery. Manufacturing clustered along the coastal industrial zones. And as Tokyo expanded, suburban residential growth filled in the map.

That mix mattered. A diversified regional economy meant a more resilient banking base. When one sector cooled, another often picked up. And because the bank was concentrated in one area, it could see shifts early. Its loan officers weren’t reading about local conditions in a report—they were living inside them.

This is the part that’s easy to miss if you only look at banking as a commodity business. In regional Japan, relationship banking isn’t a soft concept. It’s a structural advantage. A lender who has worked with a local owner through multiple cycles—who understands how the business really runs, and how the local ecosystem fits together—can make credit judgments that outsiders struggle to match, whether they’re a megabank across town or a digital bank with a slick app.

And that relationship depth, built over decades in Kanagawa, became the foundation Bank of Yokohama would eventually scale into something much bigger.

IV. Building the Regional Banking Machine (1920s-2000s)

For most of the 20th century, Bank of Yokohama didn’t grow through dramatic bets or splashy deals. It grew the way regional banks are supposed to grow: branch by branch, relationship by relationship, cycle by cycle. These were the decades when the bank built the habits and operating muscle that would matter later—when the easy era ended and survival started to depend on scale, efficiency, and trust.

The Post-WWII Regional Banking System

After World War II, Japan’s banking system settled into something like a regulated ecosystem with clear lanes. City banks—the ancestors of today’s megabanks—chased big corporates and international business. Trust banks specialized in asset management. Long-term credit banks focused on industrial financing. And regional banks like Bank of Yokohama became the default financial partner for local households and small and medium-sized businesses.

That structure created an enormous, quiet advantage: territory. Regional banks operated with a kind of protected home field. Megabanks had bigger targets and less reason to fight for smaller clients, and regulation made it hard for new competitors to break in.

Within that world, size still mattered. First-tier regional banks—those with the largest balance sheets—could run their operations more efficiently and build broader revenue streams than smaller rivals. As the biggest regional bank, Bank of Yokohama had the room to invest in people and systems that others couldn’t, even before profitability pressure became the industry’s defining problem.

The Bubble and Its Aftermath

Then came the late 1980s. Japan’s asset bubble inflated values across real estate and equities, and banks faced a temptation that looked, at the time, like common sense: lend into the boom.

When the bubble collapsed, that temptation turned into a reckoning. Some regional banks were dragged down by loans tied to speculative property deals. Others got through the period by staying disciplined—by lending based on cash flows and real business fundamentals, not the assumption that prices would keep rising.

Bank of Yokohama’s culture leaned conservative, in large part because it was built around relationship banking. When your loan officers know the owner, the supplier network, and what the factory actually produces, it’s harder to get swept away by paper valuations. And the bank’s bread-and-butter focus on SMEs—rather than a heavy reliance on large, headline corporate deals—helped buffer it from the most extreme excesses of the era.

The Seeds of Crisis

But even as Japan worked through the aftermath, the next threat was already forming. Japan became a super-aged society in 2007, and its population started shrinking in 2011—two milestones that would haunt regional banking for years. Fewer people meant fewer new borrowers, fewer businesses, and less economic dynamism in many local markets.

At the same time, the interest-rate environment kept grinding downward. As lending margins thinned, the core business model of regional banks—take deposits, make loans, earn the spread—began to look less like a machine and more like a trap. And the old “protected territory” idea started to erode as megabanks pushed outward and digital banks began to offer customers an alternative that didn’t require a branch visit.

This is where the story shifts. The pressure wasn’t a sudden shock; it was a slow-motion squeeze. And the real question wasn’t whether regional banks would need to change. It was how fast they could move before the math caught up with them. Bank of Yokohama’s leadership began thinking about consolidation well before it became the industry’s default answer.

V. The Regional Banking Crisis: Understanding the Structural Challenges

The Triple Threat

By the mid-2010s, the squeeze on Japan’s regional banks stopped being a vague concern and became something you could name. Analysts called it a “triple threat”: demographic decline, ultra-low interest rates, and digital disruption. Any one of those headwinds would have forced banks to adapt. All three, at once, went after the foundations of the regional banking model.

Loan demand was shrinking. The population was aging and, in many places, literally disappearing. And the interest-rate environment—already low for years—kept grinding down toward zero, thinning margins to the point where even well-run banks struggled to earn a decent return. Under that kind of pressure, “innovative solutions” weren’t a growth strategy. They were a survival plan.

The Demographic Reality

Start with the part no bank can fix: the customer base itself.

In non-metropolitan Japan, subdued economic vitality has become a chronic condition. Rural communities are increasingly defined by one painful pattern: small and medium-sized enterprises, often family-run or sole proprietorships, shutting their doors because there’s no successor to take over. As that happens, the demand for loans declines year by year—not because banks won’t lend, but because there are fewer viable borrowers left to lend to.

And the economic cost adds up. Estimates looking out to 2025 suggested that over a decade, the lack of successors could translate into millions of jobs lost and a major hit to GDP as SMEs close rather than transition to the next generation.

For a regional bank, this isn’t abstract macroeconomics. Each closure is a balance-sheet event. A business relationship that might have lasted decades—deposits, working capital loans, equipment financing, payments, and fee-generating services—doesn’t transfer. It vanishes. The succession problem grew so widespread that Japan had more than a million businesses without successors, a quiet crisis hiding in plain sight.

The Zero Rate Trap

Now layer on the second threat: the price of money.

Domestic banks—and especially regional banks—were hit hard by Japan’s ultra-low interest-rate environment. Banking math is simple: borrow short (deposits), lend long (loans), and live on the spread. When rates fall toward zero, that spread compresses. When rates go negative, the whole mechanism starts to feel upside down. A prolonged low-interest-rate environment, with a narrow interest margin, turns the core business of banking into a grind.

Japan’s negative rate regime began in 2016. For years, banks operated in a world where traditional lending was structurally less profitable. The Bank of Japan’s goal was clear: push money out into the economy by making it unattractive to sit on reserves. But for many regional banks, the problem wasn’t willingness. It was opportunity. Conservative lending cultures met shrinking local markets, and there simply wasn’t enough quality loan demand to put deposits to work without taking on unacceptable risk.

The Digital and Megabank Assault

The third threat was competitive—and it broke the old rules.

For decades, regional banking in Japan benefited from a kind of informal segmentation. Megabanks focused on large corporates and global business, while regional banks dominated households and local SMEs. By the 2010s, that separation was eroding fast. Megabanks pushed deeper into retail and regional corporate clients. Digital banks arrived without branch networks, and competed on experience, rates, and product design.

The result was a new fight over the cheapest, most important raw material in banking: deposits. Regional lenders were increasingly struggling to boost them. By March 2025, deposit growth at regional banks was barely moving, while megabanks were growing faster over the same period.

Digital banks added a different kind of pressure. They attracted customers with simpler interfaces, more generous deposit terms, and securities-linked products that felt modern compared to traditional branch-first banking. The warning from the market was blunt: regional lenders needed to improve services and keep customers from shifting to digital banks and megabanks, both of which were expanding their digital offerings with a focus on retail.

This is the backdrop for everything Yokohama Financial Group did next. Consolidation wasn’t just a clever way to get bigger. It was a response to a set of threats that, left unchecked, could make “regional banking” a shrinking category. The real question wasn’t whether change was necessary. It was whether moving first—and moving decisively—could turn defense into advantage.

VI. The Concordia Gambit: Creating Japan's Largest Regional Bank Holding Company (2015-2016)

The Bold Move

With the triple threat bearing down on the industry, Bank of Yokohama did something most regional banks only talked about: it moved first.

In 2015, it announced a merger with the smaller Higashi-Nippon Bank to create Concordia Financial Group, positioning the new entity as Japan’s largest regional bank holding company. Then, on April 1, 2016, the two banks completed their business integration through a statutory joint share transfer—an approach approved at an extraordinary shareholders meeting on December 21, 2015.

The mechanics mattered. This wasn’t a clean “one bank swallows another” merger. Instead, a new holding company—Concordia Financial Group—sat on top, with Bank of Yokohama and Higashi-Nippon Bank becoming wholly owned subsidiaries beneath it. That structure let both banks keep their names, their branches, and—most importantly in regional banking—the customer relationships and local credibility they’d spent decades building.

The Strategic Rationale

The official logic was straightforward: integrate business and management under one roof to unlock synergies across customer bases, expertise, and capabilities, and aim to become the leading regional bank in Japan.

But the practical rationale was even clearer. The pairing fit geographically. Bank of Yokohama was dominant in Kanagawa Prefecture and southwestern Tokyo. Higashi-Nippon Bank was stronger in other parts of the greater Tokyo area, including Gunma Prefecture. Put together, the group got broader coverage and a more diversified customer base—without a ton of redundant branches stepping on each other.

And then there was scale. In a world where margins were being squeezed and compliance and technology costs only moved one way, size wasn’t vanity—it was a defense mechanism. By combining back-office functions, sharing technology investment, and spreading regulatory overhead across a larger base, the new group could pursue cost savings that would have been hard for either bank to achieve alone.

The Name: "Concordia"

The name choice was its own kind of strategy. According to Kataoka, “Concordia” was selected to emphasize harmony and integration within the new organization. It was meant to feel balanced—more partnership than takeover.

But that neutrality came with a downside. Kataoka later acknowledged that “Concordia” didn’t clearly communicate what the group actually was at its core: a Yokohama-based regional financial institution. The word may have signaled unity, but it didn’t tap into the brand gravity Bank of Yokohama had built over more than a century.

Early Results and Challenges

Concordia Financial Group was incorporated in 2016 and headquartered in Tokyo. And like any bank integration, it came with the hard parts: aligning cultures, stitching together technology systems, and calming customers who hear the word “merger” and immediately worry about disruption.

This is where the holding company structure earned its keep. Because Bank of Yokohama and Higashi-Nippon Bank continued operating under their existing identities, customers saw fewer sudden changes. Behind the scenes, the group could coordinate strategy and consolidate functions, while out front it could preserve the local touch that regional banking runs on.

For investors, the question was whether the synergies would show up fast enough—and whether the combined entity could outgrow an industry that, structurally, wasn’t growing at all. Early signals were encouraging. But the real test was still ahead, as demographic decline and new competition continued to tighten the vise.

VII. The Kanagawa Bank Acquisition: Completing Regional Dominance (2023)

The Deal

Seven years after the Concordia formation, the group made its next big move—this time, not to broaden its map, but to tighten its grip at home.

On February 3, 2023, the Bank of Yokohama agreed to acquire a 94.05264% stake in The Kanagawa BANK, LTD. from a group of sellers for ¥8.5 billion. The terms were straightforward: ¥1,716 per common share, and ¥10,008 per preferred share.

The tender offer launched on February 6, 2023, and closed on April 4, 2023.

Compared to the Higashi-Nippon integration, this was a simpler, more targeted play. Kanagawa Bank was smaller, and it operated primarily within Kanagawa Prefecture—Bank of Yokohama’s home turf. So this wasn’t about expansion. It was about consolidation.

Strategic Logic: The Prefecture Play

Bank of Yokohama already owned more than 7% of Kanagawa Bank’s shares. The logic of going the rest of the way was clear: deepen cooperation, streamline overlap, and bring another local institution inside the same strategic umbrella.

The group later expanded to include Bank of Kanagawa. And with the Kanagawa Bank acquisition, the group moved toward near-complete dominance of its home prefecture. The three-bank structure—Bank of Yokohama, Higashi-Nippon Bank, and Kanagawa Bank—gave it broad coverage across the greater Tokyo region, while removing a competitor from the market that mattered most.

Industry Context

This deal didn’t happen in isolation. By 2023, regional bank consolidation in Japan was accelerating, pushed along by the same forces that drove the Concordia creation in the first place: prolonged low interest rates, demographic decline, and a steadily worsening profitability outlook for smaller lenders.

Around the same time, Hachijuni Bank and Nagano Bank—both based in Nagano Prefecture—reached a final agreement to merge their operations. The year before, Fukuoka Financial Group announced it was aiming to make the Fukuoka Chuo Bank a wholly owned subsidiary. Moves like these were stacking up, one after another, as restructuring became the industry’s default response.

The government, too, was encouraging mergers, offering a conditional subsidy of up to ¥3 billion to lenders that agreed to merge. The tone had shifted decisively: what once might have looked like uncomfortable consolidation was increasingly treated as necessary triage.

“I don't think there's a single regional bank president who isn't thinking about consolidation,” said Toyoki Sameshima, an analyst at SBI Securities in Tokyo.

For investors, Kanagawa Bank was a signal. Yokohama Financial Group wasn’t just an early mover that happened to land the biggest platform—it was still building, still stacking advantages, and still acting like the endgame would reward the groups with the most scale, the strongest home-market position, and the fewest distractions.

VIII. The October 2025 Rebrand: From Concordia to Yokohama Financial Group

The Name Change Decision

By early 2025, the group had done the hard, unglamorous work of consolidation. The holding company structure was stable. The three banks were operating in sync. The next step wasn’t operational—it was narrative.

On January 29, 2025, Concordia Financial Group’s board resolved to change the company’s trade name, with the change contingent on shareholder approval of amendments to the Articles of Incorporation at the 9th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders in June 2025.

A few months later, in October, Concordia Financial Group officially became Yokohama Financial Group.

The timing wasn’t accidental. The group was entering its ninth year. In other words: the integration era was over. It was time to stop sounding like a merger and start sounding like an institution.

Why Names Matter in Banking

Management’s stated aim was simple: use the stronger name recognition of “Yokohama” to solidify the brand and enhance the group’s regional contribution.

Internally, they framed it as a mission accomplished. The Group believed “Concordia” had fulfilled its role—signaling harmony and integration during the early, sensitive years of combining banks. But as a permanent identity, it had a problem: it didn’t tell anyone, in Japan or overseas, what this organization actually was.

“Yokohama” does. It’s one of Japan’s largest cities, the country’s first major international port, and a symbol of modern commerce. By putting that name on the door, the group wasn’t just refreshing a logo. It was anchoring its story to a place—and to a legacy.

In conjunction with the start of a new medium-term management plan, the group said it would change its name to Yokohama Financial Group to take the Group to the next stage and “leap into the future.”

The New Structure

Under the new name, the structure stayed the same: a regional financial group built primarily around three banks—The Bank of Yokohama, Ltd., The Higashi-Nippon Bank, Limited, and THE KANAGAWA BANK, Ltd.—with their main operating bases in Kanagawa Prefecture and Tokyo.

Bank of Yokohama remained the flagship. It also remained the footprint: 632 domestic offices, plus five overseas offices in Shanghai, Singapore, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and New York.

The advantage of the three-bank setup was that it let the group have it both ways. It could share infrastructure, talent, and know-how across the platform, while preserving the local identities and customer relationships that regional banking still runs on.

And for investors, the rebrand carried a quiet message. Companies that think they’re managing decline don’t usually bother to invest in clarity and identity. Changing the name to Yokohama Financial Group suggested something else: management believed this was a franchise worth building—not just defending.

IX. The Modern Era: Interest Rate Normalization and New Opportunities

The End of Negative Rates

In March 2024, the Bank of Japan did something it hadn’t done since 2007: it raised short-term interest rates, moving them up from -0.1% to a range of 0% to 0.1%. With that, Japan ended the world’s only negative interest-rate regime—and closed the book on eight years of banking in a world where the basic mechanics of lending had been turned inside out.

For regional banks, this was a genuine regime change. During the negative-rate era, deposits could feel like dead weight: plentiful, expensive to service, and hard to put to work profitably. Now, with rates rising, deposits snapped back into being what they used to be: the cheapest fuel in the banking system.

That’s why regional banks began racing to shore up their ability to attract and retain deposits ahead of further hikes. The twist is that higher rates don’t just expand the opportunity; they also raise the stakes. Regional banks depend heavily on retail deposits, which can be quick to move when customers start shopping for yield. Megabanks, with broader funding options and larger capital buffers, have more room to absorb that volatility. For smaller regional lenders, a rapid shift in rates can turn deposit competition into a real vulnerability.

The Competitive Dynamics Intensify

Once rates started moving again, a competition that had been mostly dormant suddenly woke up.

Investors began looking across Japan’s dozens of listed smaller banks and seeing the ingredients for more consolidation: a tougher operating environment, valuations that made deals easier to justify, and management teams under pressure to secure stable funding. Internet-based banks, meanwhile, kept growing, offering customers a deposit experience that felt faster, simpler, and increasingly competitive.

As one industry voice put it: “It is getting harder to attract deposits and I think that’s one of the changes that would prompt banks to consider consolidation.”

The early numbers told the story. By 2025, deposit growth at regional banks was running at just 0.9%, while megabanks were growing deposits at 2.7%. In a rising-rate world, that gap matters, because deposits aren’t just a balance-sheet line item anymore—they’re a strategic asset.

Yokohama's Differentiation: Structured Finance and Advisory

In that environment, Yokohama Financial Group’s playbook has been to lean into something most regional banks struggle to build at scale: specialized, higher-value corporate finance.

Among regional banks with the highest market capitalization, Concordia has ranked top in PBR and second in ROE. A major driver has been its push into structured finance, especially in Kanagawa and Tokyo—markets full of businesses facing succession questions, ownership transitions, and capital restructuring needs.

“To support these clients, we’ve been strengthening our internal capabilities and expertise to offer tailored structured finance solutions,” Kataoka said. The idea is straightforward: invest in talent, build repeatable know-how, and deliver solutions that are more advisory than transactional—aiming for higher returns while keeping risk in check.

It’s also an evolution in the regional banking model. Traditional lending rises and falls with interest margins. But advisory work—succession planning, capital restructuring, and M&A support—creates fee-based revenue that isn’t as dependent on where rates settle. And it builds directly on what Hamagin has always been good at: long relationships, deep local knowledge, and being close enough to the customer to see the real problem before it becomes a crisis.

X. The Product and Services Matrix

Core Banking Services

Zoom in close enough, and Bank of Yokohama looks like a bank. It offers the familiar menu: everyday accounts, savings, and term deposits; credit and debit cards; and a full spread of lending—consumer loans, housing, renovation, auto, education, and business financing. Add in life and annuity insurance, foreign exchange, and credit guarantees.

On the investment side, it provides trust services, asset management, mutual funds, and trading in government, local, and government-guaranteed bonds.

None of that is unusual on its own. Every regional bank in Japan can check most of these boxes. The difference for Yokohama Financial Group is less about what’s on the menu and more about how it’s delivered: at scale, through a dense local footprint, and guided by customer relationships that have been built over decades.

Who They Serve

Yokohama Financial Group provides banking products and services to small and medium-sized businesses and individuals in Japan and internationally. Beyond traditional deposits and loans, the group also offers securities, leasing, information, research, and venture capital services, delivered through a network of branches, sub-branches, ATMs, and representative offices.

This is where the old regional banking model still earns its keep. Relationship banking—deep, lived knowledge of local businesses—remains the group’s core advantage. In a world of algorithmic underwriting and digital-first banking, there’s still real edge in a loan officer who knows the owner, has walked the factory floor, and understands how the local supply chain actually works.

Beyond Traditional Lending

The shift toward fee-based services isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s a response to the central problem of modern banking in Japan: when interest margins compress, a bank that depends mainly on lending gets squeezed.

So Yokohama Financial Group has been leaning harder into advisory services, asset management, and transaction fees—revenue streams that can be steadier than the lending spread.

And there’s a deeper strategic twist here. The SME succession crisis is a threat to the group’s customer base—but it also creates demand for exactly the kind of high-touch help regional banks are positioned to provide. The business succession of SMEs is directly linked to the survival of regional economies, which makes supporting these transitions an essential duty of regional financial institutions as a way of protecting their own business foundations.

When the group helps a business find a successor, structure a transaction, or navigate a generational handoff, it isn’t just preserving loan demand. It’s keeping entire relationships alive—deposits, payroll, payments, financing, and the advisory work around it—while earning fees for a service that digital banks and distant megabanks struggle to replicate.

XI. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

As rates rose, deposits went from being abundant and underappreciated to being the cheapest, most contested fuel in the system. That shift opened the door wider for new competitors—especially internet-based banks that don’t need to build a branch network to win customers.

Digital banks can come in lean. They can lead with attractive deposit rates, clean mobile experiences, and narrowly focused products built for specific customer segments. And while regulation still matters in banking, the old sense of “protected territory” has weakened. Customers can now move money with a few taps, and new players can scale distribution without physical presence.

But there’s a ceiling to how fast newcomers can climb. Full-service banking—especially lending to local SMEs—still runs on judgment, context, and trust built over years. A fintech can launch a savings product quickly. It can’t manufacture decades of relationship history with a regional business community overnight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Depositors): MODERATE-HIGH

In this story, the “suppliers” are depositors—and right now, they have leverage.

Regional lenders have been struggling to boost deposits, and in a rising-rate world, customers have alternatives: higher-yielding products, government bonds, and digital banks willing to compete aggressively on rates and convenience. Even if many customers don’t move, the fact that they can forces banks to pay attention.

Regional banks are also structurally more exposed than megabanks. Megabanks have more diversified funding sources and bigger capital buffers. Regional lenders, by contrast, often depend heavily on retail deposits—funding that can become more rate-sensitive as customers start shopping for yield.

Yokohama Financial Group’s scale helps. With more than 20 trillion yen in deposits, it can access broader funding channels and compete more effectively than smaller peers. But the negotiating position still tilts toward depositors in today’s environment.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Borrowers): HIGH

Borrowers—SMEs and individuals—also have more choice than they used to.

Megabanks are no longer staying neatly in their old lane of large corporate clients. They’ve been pushing into regional corporate lending and retail. Digital lenders compete on speed and convenience. Government-backed programs add yet another source of financing.

That leaves regional banks defending their edge where it’s always been: relationships and local knowledge. A business owner who has worked with the same bank for decades may weigh reliability and understanding more than slightly better terms elsewhere. But that loyalty gets tested when competitors can offer meaningfully better pricing, faster approvals, or a smoother experience.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Banking’s traditional profit pools are being chipped away by substitutes on multiple fronts.

Payments are increasingly captured by mobile apps and digital wallets, pressuring transaction fee income. Larger companies can bypass banks through capital markets, including corporate bonds. Smaller borrowers have more options too, from fintech lenders to peer-to-peer platforms. And on the savings side, investment platforms and robo-advisors give customers alternatives to letting money sit in a standard deposit account.

The pressure is sharpest where the service is a commodity: basic accounts, standard loans, routine transactions. The more a bank can shift the relationship toward advice and tailored solutions, the harder it becomes for substitutes to win on pure convenience or price.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Regional banking in Japan has become a knife fight. As one quote puts it, “They [regional banks] are now facing a growing threat from megabanks and digital banks.”

Megabanks are expanding into regional markets. Digital banks are capturing attention—and deposit growth. Smaller regional banks are fighting to stay profitable. And even consolidation cuts both ways: it reduces the number of competitors, but it also creates fewer, larger, more capable rivals.

Yokohama Financial Group’s size is a real advantage here. It can invest in technology, product, and talent at levels many regional peers can’t match. But scale doesn’t end competition—it just changes the terms. The group still has to earn loyalty with service quality and protect its moat the old-fashioned way: by staying closer to customers than anyone else can.

XII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

At this point, Yokohama Financial Group is operating on a balance-sheet scale that very few regional players can match—more than 20 trillion yen in deposits and 16 trillion yen in loans. Bank of Yokohama is the largest regional bank in Japan, and that size is not just a bragging right. It changes the physics of the business.

In banking, scale buys you real operating leverage. The expensive stuff—core banking systems, digital channels, cybersecurity, data infrastructure—doesn’t get cheaper because you’re small. But it does get cheaper per customer when you’re large. The same is true of compliance. As regulation has grown more complex, the fixed cost of meeting it has climbed, and spreading that cost across more revenue matters.

This is the quiet logic behind the group’s consolidation strategy: build enough scale to compete on cost and capability, while still keeping the local trust and relationship depth that regional banking depends on.

Network Economies: MODERATE

Banking isn’t a social network, but it does have its own kind of network effect—especially in a tight economic ecosystem like Kanagawa.

When a bank has long-standing relationships with a large share of the region’s businesses, it can do more than lend. It can connect: introductions between suppliers and customers, referrals to professional services, even identifying partners or acquisition targets for companies trying to grow or solve succession issues. Those connections create value, and value tends to compound back into more relationships.

That said, the network effect here has limits. A business can bank anywhere and still trade with anyone. And while the group’s three-bank structure creates cross-selling opportunities, network economies aren’t the primary engine of advantage the way they are for platform businesses.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

There’s a real form of counter-positioning in the contrast between Yokohama Financial Group and digital-first banks.

Yokohama’s model is built on deep local knowledge, branch presence, and long-term customer relationships—investments that pure digital banks deliberately avoid. For a digital bank to replicate that kind of relationship banking, it would have to add the very cost structure it was designed to escape. In that sense, Yokohama is positioned in a place where digital competitors can’t easily follow without breaking their own model.

The caveat is that megabanks complicate the picture. They can pair strong digital capabilities with significant relationship depth, which blunts how protective this counter-positioning can be.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching banks isn’t like switching streaming services, especially for businesses.

For SME customers, changing banks can mean renegotiating credit facilities, redoing documentation, updating payment instructions with customers and suppliers, and losing the continuity of a banker who understands the company’s history and cycles. The more complex the relationship—multiple loan lines, treasury needs, long operating history—the higher the friction.

Retail customers face lower switching costs. Moving a simple savings relationship is easier, and digital interfaces make it easier still. But Yokohama Financial Group’s emphasis on SME relationships pushes its customer base toward the stickier end of the spectrum.

Branding: MODERATE-STRONG

The rebrand to “Yokohama Financial Group” wasn’t cosmetic. It was a bet that the name itself is an asset.

“Yokohama” carries immediate recognition, and within Kanagawa Prefecture the Bank of Yokohama brand has been built over more than a century. Even the nickname Hamagin signals something important: this is an institution people identify with, not just use.

In banking, trust is the product you’re really selling. Strong regional branding helps win new customers—especially businesses that would rather borrow from a known local institution than an unfamiliar alternative—and it helps keep existing customers from leaving when competitors offer slightly better terms.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

If Yokohama Financial Group has a cornered resource, it’s not a patent or a mine. It’s memory.

Decades of customer history, credit performance, and local context—combined with the institutional knowledge in relationship managers and loan officers—create an information advantage. Knowing how a business actually behaves through cycles, how its management operates, and how it fits into the local supply chain can be hugely valuable for underwriting and advisory work. And it’s not something a new entrant can copy quickly.

This advantage is “cornered” mostly against newcomers. Megabanks can build similar knowledge over time, but doing it at the same intimacy and density in a specific region takes sustained investment.

Process Power: DEVELOPING

Putting three banks under one holding company creates the opportunity for process power: better risk management, more consistent credit decisioning, stronger customer service routines, and more scalable digital delivery.

From the outside, it’s hard to prove how far that advantage has already been built. But the ingredients are there. When a group has scale, a concentrated footprint, and a clear need to operate more efficiently than smaller peers, process improvement stops being a side project. It becomes a competitive weapon.

XIII. Investment Considerations

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking Yokohama Financial Group as a long-term investment, two signals matter more than almost anything else because they tell you whether the whole strategy is actually working.

Net Interest Margin (NIM): In a world where interest rates are finally moving again, NIM becomes the clearest read on whether the group can turn “rate normalization” into real earnings. The key dynamic to watch is repricing speed: can loan yields move up before deposit costs do? With deposit competition intensifying, that spread is the difference between a tailwind and a mirage.

Cost-to-Income Ratio: The consolidation story only pays off if scale turns into efficiency. Cost-to-income is the simplest scoreboard for that: how much profit you keep for each yen of revenue you generate. If the ratio keeps improving, it’s evidence the integration is producing the cost synergies it promised. If it slides the other way, it suggests the group is losing the efficiency race—either to internal complexity or to margin pressure from competition.

What Management Gets Right

Two years earlier, Kataoka surprised the market by making a pledge that’s still unusual among Japanese regional banks: targeting a price-to-book ratio (PBR) of 1.0.

“Given our high proportion of foreign institutional investors, we have held ongoing discussions about how to improve corporate value and raise return on equity (ROE),” he explained.

That framing matters. Most regional banks talk primarily about stability and regional mission. Yokohama’s leadership is signaling something else: an awareness that capital is optional. Investors can choose megabanks, insurers, global banks, or just buy the index. If you want to keep earning the right to exist as an independent public company, you have to show you can compound value.

Among regional banks with the highest market capitalization, Concordia ranked top in PBR and second in ROE. And the group’s push into structured finance and succession-related advisory reinforces the point: it’s a strategy built to produce fee income and higher-value corporate relationships, not just more low-margin loans.

Key Risks

Demographic Headwinds: No management team can out-execute Japan’s population math. Rural populations are expected to shrink materially by 2035. Even with perfect execution, a bank tied to regional economies faces the possibility that its addressable market simply gets smaller.

Competition for Deposits: The post-negative-rate environment turns deposits into a prize again—and that prize is getting harder to win. By 2025, deposit growth at regional banks slowed to 0.9%, well behind megabanks at 2.7%. If that persists, funding costs rise, pricing power weakens, and loan growth becomes harder to sustain.

Integration Execution: A three-bank structure can be a strength, but it’s also operationally heavy. Culture mismatches, technology integration, and the day-to-day coordination tax can quietly eat the scale benefits that looked obvious in the deal deck.

Interest Rate Sensitivity: Rising rates can lift NIM, but they can also trigger churn. If customers start actively shopping for yield, deposits can move faster than banks are used to. Asset-liability management becomes the knife edge: manage it well, and higher rates help; manage it poorly, and the same rates can destabilize funding.

The Bull Case

Yokohama Financial Group built the biggest regional banking platform in Japan right as scale became the defining advantage. The end of negative rates offers a structural lift to profitability. Its emphasis on structured finance and succession advisory creates more differentiated, higher-margin revenue than plain-vanilla lending. Its Kanagawa and greater Tokyo footprint keeps it anchored to one of Japan’s most economically resilient regions. And JCR’s AA/Stable long-term issuer ratings for Concordia Financial Group, Bank of Yokohama, and Higashi-Nippon Bank add a layer of confidence around financial stability.

The Bear Case

Regional banking in Japan is still fighting structural decline, and there’s a plausible world where consolidation can only slow it, not reverse it. Even with recent improvements, profitability across regional banks has become more uneven than it was a decade earlier. If the interest rate upcycle benefits stronger players disproportionately, weaker banks may end up squeezed—forced to either pull back on lending or reach for risk.

At the same time, relationship banking—Yokohama’s historical moat—could become less differentiating as digital tools improve underwriting, marketing, and customer acquisition. Megabanks and digital banks may keep taking share in deposits and lending, leaving regional banks competing over a smaller pool. And looming behind all of it is the hardest variable to handicap: Japan’s long-term growth trajectory itself.

XIV. Conclusion: Heritage as Strategy

The story of Yokohama Financial Group is, in the end, a story about heritage—and about refusing to treat heritage as a substitute for strategy.

Heritage gave the franchise its moat: more than a century of relationship-building that can’t be rebuilt on a spreadsheet, local knowledge that doesn’t travel well, and a reputation that newcomers can’t shortcut. It’s why the Bank of Yokohama can credibly claim one of the longest lineages in Japanese banking, tracing its roots back to 1869.

But heritage doesn’t pay the bills by itself. Japan’s regional banking math has been changing for years: fewer borrowers, tighter margins, and more competition for deposits and attention. Yokohama’s leadership seemed to see that earlier than most, and they acted while others debated.

Look at the sequence. The creation of Concordia Financial Group in 2016 built a platform big enough to absorb the fixed costs of modern banking. The Kanagawa Bank acquisition in 2023 tightened control of the home market, turning overlap into coordination. Then, in 2025, the group dropped “Concordia” and put “Yokohama” on the masthead—making the identity as clear as the footprint. Together, those moves tell a coherent story: get the scale to invest in capability, without giving up the relationship depth that makes a regional bank more than a commodity lender.

There’s also a bigger point here that sits behind the balance sheet. In Japan, regional banks and regional revitalization are joined at the hip. When a local bank helps a business survive a succession crisis, finance an expansion, or navigate a restructuring, it isn’t just protecting its own loan book. It’s helping decide whether that local economy keeps functioning.

Will Yokohama Financial Group’s strategy work? The honest answer is: it depends. Interest rates will move. Demographics will keep grinding. Digital banking will keep improving. Competitors will keep pressing. Some of those variables management can influence; many it can’t.

What does seem clear is that Yokohama Financial Group has set itself up as well as any regional bank in Japan realistically can. It leads the sector in scale, sits in one of Japan’s most economically resilient regions, and has shown a willingness to make shareholder-facing commitments while still leaning into what regional banking does best.

For students of business history, it’s a case study in turning legacy into leverage. For long-term investors, it’s a way to own Japan’s regional banking story through its strongest platform. And for anyone trying to understand where Japanese finance is headed, it’s a clean signal of the direction of travel: consolidation, specialization, and a fight for relevance in a world where the old rules no longer protect you.

The port of Yokohama opened in 1859, and modern Japanese commerce followed. More than a century and a half later, a bank born from that same city’s transformation is still financing the lives and livelihoods of Kanagawa. That kind of continuity, in an era that rewards novelty, is rare. Whether it lasts another century will come down to the same thing that created it in the first place: adapting fast enough to keep earning trust.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music