Mebuki Financial Group: A Tale of Two Banks and the Regional Banking Renaissance

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

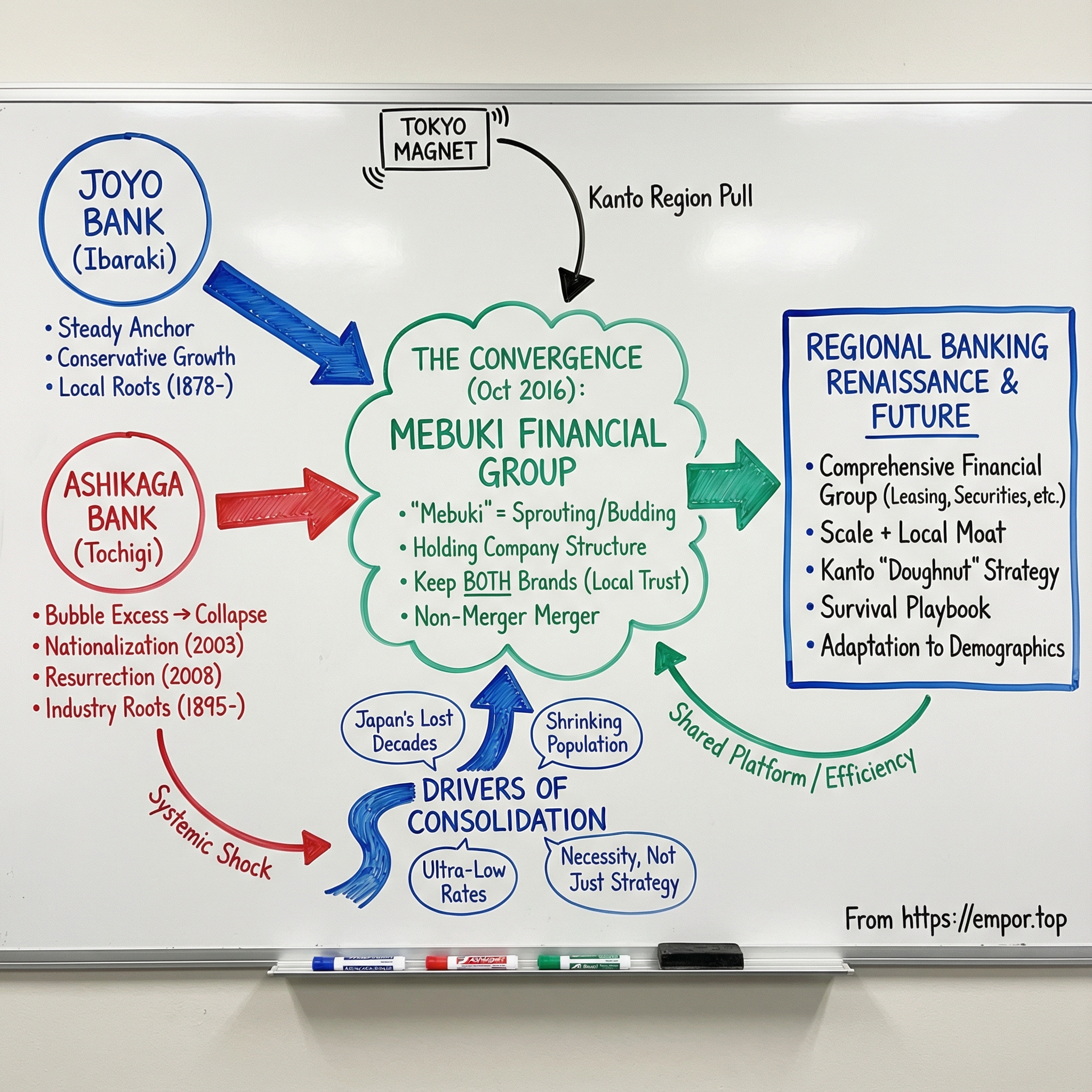

It’s October 2016, and the setting is deliberately unglamorous: a plain conference room in Tokyo, a long table, a few microphones, and two sets of leaders who know exactly what this moment means. Behind them are banners with a single, unfamiliar word: Mebuki. In Japanese, it means “sprouting” or “budding”—the first green push of new life after a long dormant season. For Joyo Bank President Kazuyoshi Terakado and Ashikaga Holdings President Masanao Matsushita, that name was the point. This wasn’t just a deal. It was a statement: a regional banking reboot.

On October 1, 2016, Mebuki Financial Group Inc. began operations as the combined holding company for Joyo Bank Ltd. and Ashikaga Holdings Co. Ltd. In one move, it became Japan’s third-largest regional banking group, behind only Concordia Financial Group and Fukuoka Financial Group.

This is modern Japanese finance in miniature: deep tradition, a system still shaped by past crises, and a future constrained by realities no amount of optimism can wish away. Japan’s population is shrinking and aging. Growth has been sluggish. Interest margins have been squeezed for years. In that environment, regional banks have been forced to search for ways to stay relevant—partnerships, integrations, consolidations—anything that keeps them strong enough to serve their communities and stable enough to survive.

Which brings us to the question at the center of this story: how did a once-bankrupt regional bank and its steady neighbor end up joining forces to become one of Japan’s most important regional financial institutions—and what does that journey tell us about survival through Japan’s Lost Decades?

To understand why these two belonged together, you have to understand where they came from. Joyo Bank is the largest regional bank in Ibaraki Prefecture. Ashikaga is the dominant lender in neighboring Tochigi Prefecture. Both sit in the Kanto region, the economic gravity well that includes Greater Tokyo and roughly a third of Japan’s population. Close enough to benefit from Tokyo’s pull, but far enough to feel constantly threatened by it.

Mebuki’s structure was also a clue to the strategy. This wasn’t built to be “just a bank.” The group positioned itself as a broader financial platform—banking at the center, supported by leasing, securities, credit guarantees, and credit cards. That breadth isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s an adaptation to a world where lending alone doesn’t pay like it used to.

From here, the story splits into two origin tales that eventually collide. One is about steady, conservative growth—boring, disciplined, and quietly powerful. The other is about ambition, excess, collapse, and an almost unbelievable comeback powered by government intervention. When they finally come together, they don’t do it through a clean, full merger. They choose something more Japanese and more delicate: a “non-merger merger,” keeping separate brands because in regional banking, trust is local, and identity is an asset.

That’s the roadmap. Two banks. Two histories. One new name meant to signal a fresh start—and a bigger lesson about what it takes to endure when the old playbooks stop working.

II. The Geography: Why the Kanto Region Matters

To understand Mebuki, you have to understand the ground it stands on—literally.

Japan’s prefectural banking system doesn’t map cleanly onto anything in the West. Each of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures has traditionally been anchored by one or more “first-tier regional banks”: local institutions that don’t feel like branch offices of Tokyo giants, but like civic infrastructure. They hold the payroll accounts. They finance the small manufacturers. They sponsor the festivals. Their advantage isn’t a clever product. It’s decades of relationships and trust.

And Mebuki’s home turf is the most important piece of real estate in the country: the Kanto region. Because Kanto includes Tokyo—the capital, the corporate center, the gravitational pull—the region sits at the heart of Japan’s politics and economy. Roughly a third of Japan’s population lives here.

Kanto is seven prefectures: Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, Saitama, Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gunma. Zoom out and you can see why this matters: the Greater Tokyo Area concentrates government, universities, culture, industry, and corporate headquarters at a scale that overwhelms everything around it.

For Joyo in Ibaraki and Ashikaga in Tochigi, that creates a very particular strategic situation—what you might call the “doughnut around Tokyo.” The center of the doughnut is Tokyo itself, where megabanks are strongest. The ring around it—places like Mito and Utsunomiya—still runs on local relationships, and that’s where regional banks can build real moats.

Ibaraki is a good example. It ranks only 24th in size among Japan’s 47 prefectures, but it ranks 4th in usable land area. That translates into agriculture, a more rural population, and the kind of geography that forces banks to keep a big branch footprint. For Joyo, that meant a network that could look inefficient on paper—but it also meant something else: fewer competitors willing to do the slow, local work. The result was dominance at home, with a large share of deposits and loans in Ibaraki.

The “doughnut” logic is simple. Tokyo’s megabanks are great at Tokyo. But they’re not built to replicate relationship banking in the surrounding prefectures—the kind where a small business owner expects their banker to know the family history, understand seasonal cash flows, and pick up the phone when something goes wrong. That preference for local, familiar brands is exactly why banks like Joyo and Ashikaga remained so entrenched.

But there’s a shadow side. The same Tokyo magnet that creates opportunity also pulls people away. As young residents move toward the capital, the population base that sustains local lending, local deposits, and those long relationships slowly thins out.

Hold that tension—between the strength of local moats and the long-term drift toward Tokyo. It’s the backdrop for everything that comes next, and it’s why these regional banks aren’t just financial institutions. In many communities, they’re the system that keeps the local economy running.

III. Origin Story Part 1: Joyo Bank — The Steady Anchor (1878–2000)

In the summer of 1878, Japan was reinventing itself in real time. The Meiji Restoration was still young. The old order was breaking apart, and the country was sprinting to industrialize before the Western powers could define its future for it.

In Ibaraki Prefecture, just northeast of Tokyo, local merchants and landowners did something practical in the middle of all that upheaval: they built financial institutions that could turn local savings into local progress. Two small banks were established that year—Goju Bank and Tokiwa Bank. Decades later, on July 30, 1935, they merged. The result was Joyo Bank.

Early on, these weren’t “banks” in the glossy modern sense. They were community machines: places where farmers, shopkeepers, and small manufacturers parked their money—and where that money, in turn, got loaned back into the region. Financing a rice polishing operation. Helping a merchant expand. Supporting the kind of incremental growth that doesn’t make headlines but builds an economy.

That local-first DNA never really left. Joyo Bank is headquartered in Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and it grew into one of Japan’s larger regional lenders, with branches across the Kanto region. Over time, it also established outposts beyond its home base—branches in places like Miyagi, Fukushima, Chiba, Saitama, Tokyo, and even Osaka—and a representative office in Shanghai.

But the more revealing part of Joyo’s story isn’t where it went. It’s how it behaved.

For much of its first century, Joyo was the kind of bank you’d call conservative—steadily expanding, building a wide branch network throughout Ibaraki, and largely resisting the temptation to chase fast growth for its own sake. In a prefecture with lots of usable land, strong agricultural production, and a dispersed population, that branch footprint wasn’t just a strategy; it was the cost of doing business. And it reinforced the bank’s identity as local infrastructure.

Even when Japan entered the go-go years, Joyo’s version of “expansion” stayed relatively measured. During the 1980s and 1990s, it opened representative offices in major global markets: London (1982–2000), New York (1987–2002), Hong Kong (1994–1999), and Shanghai (established in 1996). In the end, only Shanghai remained.

That restraint mattered. When Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1990 and the bad loans started surfacing, Joyo’s more conservative lending meant it came through in far better shape than banks that had gorged on speculative real estate.

One place where Joyo did push—quietly, early, and with purpose—was Tokyo. It began expanding its Tokyo corporate business in 1965. And by the year ended March 2016, about half of its corporate loans came out of Tokyo.

But this wasn’t a regional bank trying to reinvent itself as a Tokyo player. It was something more disciplined: Joyo following its customers. As Ibaraki-based companies expanded into the metropolitan area, Joyo wanted to stay their bank, even as their zip codes changed.

That distinction—deepening existing relationships rather than chasing shiny new ones—became one of Joyo’s defining traits. And later, it would become one of the core pieces of logic behind why teaming up with Ashikaga could actually work.

Because through Japan’s Lost Decades, while plenty of institutions found themselves buried under problem loans, Joyo kept doing what it had always done: stay close to home, lend carefully, and play the long game. In regional banking, “boring” isn’t an insult. It’s survival.

IV. Origin Story Part 2: Ashikaga Bank — Rise, Fall, and Resurrection (1895–2008)

A. The Glory Days

Ashikaga Bank was founded in 1895, in Tochigi Prefecture—Joyo’s neighbor to the north. If Joyo’s identity was shaped by rural Ibaraki and patient, community-first banking, Ashikaga’s roots were tied to something different: industry.

Tochigi sat close enough to Tokyo to benefit from the capital’s growth, but far enough to build its own economic engine. As rail links strengthened in the early twentieth century, manufacturing took hold. Ashikaga financed the factories, backed local employers, and built a commanding position as Tochigi’s go-to lender.

By the 1980s, it had become one of Japan’s standout regional banks, offering the full menu you’d expect: deposits and loans, foreign exchange, investment and securities-related services, factoring, and more. It was big, it was deeply embedded in the region, and it had the confidence that comes with being the default institution for an entire prefecture.

Then came the late-1980s bubble—and with it, the most dangerous kind of tailwind: easy money plus a belief that prices only went one direction. Stocks and real estate surged. The Nikkei hit its peak in 1989. And across Japan’s banking system, the same idea took hold: land was scarce, Japan was booming, and property values wouldn’t meaningfully fall.

Ashikaga leaned into the moment. Like many of its peers, it expanded aggressively, extending credit to real estate developers and speculative projects that looked safe only because the market had stopped pricing risk.

B. The Bubble Bursts and the Lost Decade

In late 1989, the Bank of Japan moved to cool things down, sharply raising inter-bank lending rates. The air came out of the bubble fast. The stock market fell hard. Asset prices followed. And what had looked like solid collateral on bank balance sheets turned into sand.

Japan’s downturn dragged on for years. Equity prices plunged in the early 1990s, and land values kept sliding through the decade into the early 2000s. Banks that had lent freely against rising real estate suddenly found themselves holding loans secured by assets worth far less than anyone had assumed.

For Ashikaga, that was the nightmare scenario. It had meaningful exposure to real estate-backed lending, and as borrowers struggled, non-performing loans piled up. The bank’s problem wasn’t just losses—it was time. Every year the economy stayed weak, the chances of “growing out” of the hole got smaller.

In that environment, a practice took hold across the system: banks kept lending to borrowers that couldn’t really repay, because forcing a default would mean recognizing losses immediately. Researchers later dubbed this “ever-greening”—rolling over loans and restructuring them on paper to avoid admitting the underlying reality. The effect was to keep failing companies alive as “zombies,” and to leave the banks themselves drifting in the same half-alive state.

Government support helped prevent a sudden collapse. Institutions received capital infusions, benefited from cheap central bank funding, and were allowed to postpone the recognition of losses. But the longer it went on, the clearer the cost became: a banking sector that was stable enough not to die, yet too impaired to fully do its job.

Ashikaga was heading toward the cliff.

C. The Nationalization Drama (2003)

By 2003, the situation stopped being manageable. External auditors concluded Ashikaga was insolvent—a blunt, public verdict that left the government with an ugly choice: let a major regional lender fail, or step in and own the fallout.

The Koizumi government chose intervention. It announced it would take over Ashikaga Bank in the country’s first bank nationalization in five years.

On December 1, 2003, Ashikaga Bank was nationalized under Article 102, Paragraph 1, Item 3—commonly called the Item 3 Measure. This was not the kind of tool regulators used casually. Item 3 was the last resort, applied when systemic risk couldn’t be contained through less extreme measures.

The Deposit Insurance Corporation acquired all shares, effectively placing the bank under state control. Politically, it was combustible: Ashikaga wasn’t an abstract financial institution. In Tochigi, it was the financial lifeline for small and mid-sized businesses—the payroll accounts, the working capital lines, the quiet engine behind the local economy. The fear wasn’t just about one bank; it was about what a failure would do to the prefecture.

To stabilize markets, the Bank of Japan also moved quickly, telling financial institutions it would inject 1 trillion yen into the short-term money market to cushion the broader system from the shock.

Ashikaga had become a national issue.

D. The Turnaround Years (2003–2008)

Nationalization didn’t mean instant recovery. It meant triage.

Under special crisis management and supported by public funds, Ashikaga operated under a new management team tasked with one job: clean up the bad loans and make the bank viable again. The plan was executed within the constraints of government control, which insiders described with a phrase that captured the frustration of the era: the bank was “swimming with its hands tied.”

It took four and a half years. Ashikaga couldn’t chase growth; it had to rebuild trust, rebuild its balance sheet, and rebuild its discipline.

Then came the handoff back to the private sector. The bank was sold via a limited tender to a financial consortium led by a Nomura Holdings subsidiary. For Nomura, it was a major domestic move—and a first serious attempt to prove that a failed bank could be revived and run as a competitive institution again.

On July 1, 2008, the consortium acquired all outstanding shares from the Deposit Insurance Corporation of Japan. That same day, special crisis management ended as the DICJ transferred its holdings to the new owners.

Ashikaga emerged leaner, cleaner, and fundamentally changed. The bubble-era confidence was gone, replaced by a hard-earned sensitivity to risk—and a determination, forged in near-death, not to repeat the mistakes that put it on the brink in the first place.

V. The Forces Driving Consolidation: Why Two Banks Had to Become One

By the early 2010s, Joyo and Ashikaga had very different backstories—but they were running into the same wall.

Masanao Matsushita, Ashikaga’s president, put it plainly: the decision to merge with Joyo came down to a shrinking local economy and relentlessly low interest rates. The math of regional banking was getting worse every year, and no amount of pride in local independence could change that.

First came the demographics. Japan’s population was set to fall across nearly the entire country by 2035, and the pain wouldn’t be evenly distributed. Rural areas would be hit hardest—exactly the places regional banks were built to serve. As younger people left for Tokyo, the ring around the capital slowly lost the very customers that generated deposits, loans, and the next generation of business relationships.

Then came the rate environment. Ultra-low—and at times negative—interest rates crushed the traditional banking model. When the spread between what you pay depositors and what you earn on loans gets squeezed thin enough, the “boring” business of taking deposits and making loans stops being boring and starts being brutal.

And hovering over all of it was competition. The megabanks were never going to become hometown institutions, but technology let them reach into regional markets more effectively than before, targeting the best corporate clients while leaving regional banks with the harder, lower-margin work.

As one senior economist at Japan Research Institute observed, regional banks were suddenly forced to think differently about growth. In a world shaped by negative rates, deposits could feel like dead weight. But as the rate cycle shifted, deposits looked valuable again—something you might even pursue through M&A to improve margins and stabilize earnings.

Against that backdrop, consolidation started to look less like an industry trend and more like an inevitability. Japan’s banking system was crowded to the point of absurdity, with dozens of regional banks competing in a country whose population—and loan demand—was heading the other direction.

So when Joyo Bank and Ashikaga Holdings moved to join forces, it wasn’t just to become bigger for the sake of being bigger. Yes, scale helped: shared back-office systems, bigger budgets for technology, more sophisticated risk management. But the real prize wasn’t efficiency. It was resilience.

In an overbanked country with shrinking markets and thinning margins, the logic of combining was simple: build enough scale to withstand the squeeze—or get squeezed out.

VI. The 2016 Merger: Creating Mebuki Financial Group

A. The Deal Structure

By the time Joyo and Ashikaga were ready to make it official, the blueprint was clear: a stock swap, and a new joint holding company that would sit above both banks.

On October 1, 2016, that plan became real. Mebuki Financial Group began operations as the holding company, and Joyo Bank came under its umbrella. But this wasn’t the classic “winner absorbs loser” merger. The structure was intentionally more careful than that.

Instead of forcing two very different institutions into a single legal bank overnight, they created Mebuki Financial Group and kept Joyo Bank and Ashikaga Bank operating as distinct entities beneath it. Same parent. Separate banks. Separate identities.

B. The Strategic Logic: Why Keep Both Brands?

Keeping both brands wasn’t a side effect. It was the strategy.

When S&P Global Market Intelligence asked why they didn’t just merge the banks outright, the answer was blunt: they didn’t consider a merger.

On paper, that sounds like they were walking away from the easiest efficiencies. But in regional banking, efficiency is only half the game. The other half is trust—and trust is local.

There also wasn’t much practical duplication to cut. The two networks barely overlapped, and they made it clear they weren’t planning a branch cull. Ashikaga had eight branches in Ibaraki, and Joyo had eight in Tochigi—enough to serve customers across the border, not enough to justify ripping out one network in the name of “synergy.”

The deeper point was simple: in relationship banking, the brand on the door is the relationship. For customers, switching names can feel like switching banks. And risking that kind of friction would undermine the very asset they were trying to protect.

C. What "Mebuki" Means

Even the name was chosen to carry that message.

Mebuki (めぶき) means “sprouting” or “budding”—the first sign of growth pushing up through the soil. It was a clean, forward-looking label that didn’t force either side to surrender its legacy. And for Ashikaga, a bank that had nearly died under the weight of its own bad loans, the metaphor landed especially well.

The group wrapped it in a clear philosophy: “Together with local communities, we will continue to build a more prosperous future by providing high-quality, comprehensive financial services.”

In other words: this wasn’t about building a Tokyo powerhouse. It was about building a stronger local platform.

D. The Tokyo Question

Of course, once you create a large regional banking group in the Kanto orbit, everyone asks the same question: is this really a regional consolidation story—or is it a backdoor move into Tokyo?

The company’s answer was explicit. While some regional banks had been opening Tokyo branches to chase real estate-related lending, Mebuki said this integration wasn’t aimed at targeting the Tokyo market. Their customers in Ibaraki and Tochigi already did business in Tokyo—and in nearby Saitama and Chiba. The goal was to support those existing customers as they expanded, not to go hunting for new ones in the capital.

That distinction mattered because it defined the risk posture. Following customers is very different from chasing a market.

And Ashikaga’s own numbers reinforced the point. It had roughly ¥500 billion in corporate loans in Tokyo, but that balance had been shrinking. The bank had been deliberately pulling back as spreads fell and margins compressed.

VII. The Modern Era: Building a Comprehensive Financial Group (2016–Present)

After the integration, Mebuki’s ambitions quickly widened beyond the classic regional-bank playbook of deposits in, loans out. The point of the holding company structure wasn’t just to sit on top of two banks. It was to build a broader financial group that could earn money even when lending margins were thin.

One clear example was leasing. Mebuki moved to strengthen that business by folding Joyo Lease Co. Ltd. and the leasing division of Ashikaga Credit Guarantee Co. Ltd. into Mebuki Lease, consolidating capability that had previously been split across the legacy organizations.

Today, the group runs as a cluster of specialized businesses: Joyo Bank and Ashikaga Bank at the core; Mebuki Lease for equipment and asset financing; Mebuki Securities (formerly Joyo Securities) for capital markets services; Mebuki Credit Guarantee for loan guarantees; and Mebuki Card for credit card services. The strategy is straightforward: serve customers through more of their financial lives, and earn more fee-based revenue that isn’t dependent on interest spreads.

By fiscal year 2024, that diversification was showing up in results. Net income attributable to owners of the parent rose ¥14.8 billion year over year, up 34.2%, to ¥58.2 billion—the highest full-year profit since the business integration.

The drivers weren’t mysterious, but they were meaningful. As domestic interest rates rose, the gap between what the group earned on loans and what it paid on deposits improved. Fee income increased as customers used more services. Securities income benefited from the way the group managed its portfolio. Put together, it was a reminder of why Mebuki wanted to be a “financial group,” not just two banks sharing a name.

Shareholders felt it too. The total amount of shareholder returns scheduled for the fiscal year was ¥45.5 billion, also the highest level since integration. And profit from customer services increased by ¥2.6 billion year over year, continuing a steady rise since FY2019 and nearly doubling compared with immediately after the integration in FY2016.

In other words, the slow work of building a combined platform—and waiting for real synergy to show up—was finally paying off. Ordinary profit increased by ¥19.7 billion to ¥82.8 billion, helped by wider interest margins and strategic adjustments in the securities portfolio.

Looking ahead, Mebuki laid out its next set of goals: an expected ordinary profit of ¥100 billion in FY2025, net profit attributable to owners of the parent of ¥70 billion, and enhanced shareholder returns, including a plan to increase annual dividends per share to ¥24. Longer term, it aimed for a consolidated ROE of 9.0% or more by FY27—an explicit attempt to translate regional scale and diversification into sustained profitability.

VIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE

Japanese banking is not an easy industry to break into. The regulators demand rigor, the capital requirements are high, and in regional banking especially, the real barrier isn’t money—it’s time. To win meaningful share, a newcomer has to earn trust from local households and small businesses, relationship by relationship, over years.

Still, a new kind of entrant is creeping in through the side door. Fintech firms and neo-banks can onboard customers cheaply and meet simple needs without a dense branch network. They’re not built to replace the full regional bank relationship overnight, but they can skim off profitable activity. The regional banks that do best in this environment will be the ones that modernize without breaking the community-rooted model that makes them valuable in the first place.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For banks, “suppliers” are mostly depositors and capital providers. In Japan’s still-low-rate world, depositors don’t have many compelling alternatives, so their leverage is limited.

The bigger pressure points are more operational. Technology vendors can have some sway as banks ramp up digital transformation, and Japan’s tightening labor market is making talent more expensive, especially as demographics squeeze the workforce. But overall, supplier power remains manageable.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

In Ibaraki and Tochigi, Mebuki benefits from the kind of market position most banks can only dream about: roughly 40% share in each prefecture. For everyday banking, that creates real pricing power, and for many smaller businesses, the alternatives aren’t plentiful.

But the leverage flips as you move upmarket. Larger corporate customers can compare offers and play regional lenders against Tokyo megabanks, pushing prices down at the high end. And individual depositors, while important in aggregate, have limited bargaining power when deposit rates are close to minimal.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Substitutes are rising—just not always where people expect. Digital payments reduce how often customers need a traditional bank touchpoint. Direct lending platforms remain early in Japan, but they represent a long-term challenge to the classic loan-and-deposit model.

At the same time, the core of Mebuki’s franchise—relationship-based lending to SMEs—is hard to digitize away. A factory owner in Tochigi doesn’t just need an interest rate. They need a banker who will show up, understand the equipment, grasp the cash-flow seasonality, and make judgment calls that don’t fit neatly into an algorithm.

5. Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry is intense, and it’s getting sharper. Regional banks, especially smaller ones, are generally in a weaker position than the three megabanks when it comes to passing higher funding costs on to borrowers, because they’re expected to support local businesses. As one warning put it, “They [regional banks] are now facing a growing threat from megabanks and digital banks.”

Competition comes from every angle: megabanks reaching into regional corporate lending, regional peers consolidating into stronger groups, and years of margin pressure that have made price competition hard to avoid. In an industry where products can look similar and price is difficult to defend, the fight shifts to relationships, service, and scale—and the intensity stays high.

IX. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Putting Joyo and Ashikaga under one roof did what consolidations are supposed to do: it created scale in the unsexy places that matter—back office, technology, and risk management. With one of the largest asset bases among regional banking groups, Mebuki can spread fixed costs more effectively than smaller rivals.

But the group also chose to leave some efficiency on the table. By keeping two banks and two brands, it limited how far it could push classic merger synergies.

2. Network Economies: MODERATE

The adjacency of the two franchises is the network. If you’re a business that operates in both Ibaraki and Tochigi, you can now treat the region like a single footprint, even if the signs on the branches still say Joyo and Ashikaga.

And the network isn’t just geographic. Banking plus securities plus leasing plus cards means more ways to stay connected to the same customer. More touchpoints. More opportunities to solve problems. And, over time, more reasons it’s inconvenient to leave.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

This is where Mebuki looks most defensible. Its regional, relationship-driven model is fundamentally different from the megabanks’ national and global orientation.

For a megabank to truly compete here, it wouldn’t be a matter of opening a few branches or running a marketing campaign. It would require changing how it operates—how it evaluates credit, how it staffs and incentives bankers, how it spends time with smaller clients. That kind of shift clashes with the megabanks’ core strategies and capabilities.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

For SMEs, “switching banks” isn’t like switching phone carriers. It’s unwinding covenants and guarantees, rebuilding years of relationship history, and re-documenting how the business actually works.

Then there are the daily operational hooks: payroll, cash management, treasury services. Once those are embedded, moving is painful. The exception is the simplest product—basic deposit accounts—which are easier to move if customers feel a reason to.

5. Branding: STRONG (Locally)

In regional banking, brand isn’t about national awareness. It’s about whether a family business owner trusts the name on the door.

Joyo has nearly 150 years of presence in Ibaraki. Ashikaga carries something rarer: a resurrection story that signals endurance and hard-earned discipline. In their home prefectures, those brands communicate stability and local commitment in a way a generic national brand often can’t.

The downside is obvious: step outside their core regions and that brand power fades quickly.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Decades of lending to the same communities creates an asset that doesn’t show up cleanly on a balance sheet: deep, practical knowledge of local businesses and local cycles. Credit histories on regional borrowers, learned behaviors, and long-running relationships with local government, institutions, and business groups—those are advantages competitors can’t replicate overnight.

Still, parts of it are more fragile than they look. Relationship managers can be hired away, even if rebuilding trust takes time.

7. Process Power: EMERGING

Mebuki’s process advantage is still forming, but you can see the outline. Joyo’s conservative approach and Ashikaga’s post-crisis risk discipline create a blended playbook: careful underwriting, sharper attention to risk, and an institutional memory that’s been stress-tested.

At the same time, the work isn’t finished. Digital transformation remains a continuing investment, and sustainability and ESG considerations are becoming a bigger part of how lending decisions get made across the group.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Lesson 1: The Power of the "Non-Merger Merger"

Mebuki’s holding company structure is a playbook for consolidation in a relationship business. By keeping two brands, the group protected the thing that actually drives regional banking: local trust. At the same time, it could still combine the unglamorous parts—back-office functions, systems, and technology spend—where scale really matters. It’s a deliberate trade: leave some headline “efficiency” on the table in exchange for preserving the intangible assets that make the franchise work in the first place.

Lesson 2: Resurrection is Possible—With the Right Intervention

Ashikaga’s arc—from nationalization to becoming a core pillar of Japan’s third-largest regional banking group—shows that a bank can come back from failure, but only with the right sequence of moves. It took decisive government action that protected depositors while wiping out shareholders, a new management team with a clear mandate, the time and room to clean up the balance sheet, and then a return to private-sector discipline and capital through Nomura’s involvement. None of those steps alone would have been enough. Together, they made a reboot possible.

Lesson 3: Regional Focus as Competitive Moat

Even in an era of digital disruption, local banking is still, stubbornly, local. Megabanks can win on price and polish, but they have a harder time replicating what regional lenders accumulate over decades: real knowledge of local industries, local cycles, and local people. Mebuki’s stated goal—provide loans and help existing customers in Ibaraki and Tochigi expand across the region—captures the strategy. It’s not about chasing strangers in Tokyo. It’s about staying indispensable to the customers who already trust you.

Lesson 4: Conservative Banking Has Merits

Joyo’s “boring” culture turned out to be a competitive advantage. By resisting the bubble-era temptation to chase speculative lending, it avoided the kind of catastrophic damage that takes decades to undo. That restraint is what allowed Joyo to become an acquirer rather than a rescue case. In banking, the compounding is asymmetric: big mistakes don’t just set you back, they can end you. The winners are often the institutions that simply refuse to blow themselves up.

Lesson 5: Navigating Demographic Decline Requires Diversification

Japan’s demographic trajectory forces regional banks to evolve. If the population shrinks and traditional lending growth stalls, you can’t rely on spread income alone. Mebuki’s push into securities, leasing, credit guarantees, and advisory-style services isn’t a side business; it’s an adaptation. And the group’s openness to welcoming other banks in the future is an unspoken admission of what the whole story has been pointing to: the consolidation wave isn’t over.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The optimistic thesis for Mebuki starts with a simple fact: the integration is showing up in the numbers. In fiscal year 2024, consolidated net income reached ¥58.2 billion, the highest full-year profit since the business integration.

The second pillar is macro—and it’s the kind of macro Japanese banks have been waiting a generation for. After decades of near-zero rates, the Bank of Japan began moving toward normalization. For a traditional bank, that matters immediately: when rates rise, the spread between what you earn on loans and what you pay on deposits has room to widen again.

You can see that tailwind across the industry. By September 2024, regional banks’ net interest income was up 9.0% year-on-year as rates rose. If the rate upcycle continues, regional lenders like Mebuki are positioned to benefit.

Third is geography. Mebuki’s footprint sits in the Kanto region, the country’s economic core. Being anchored in Ibaraki and Tochigi, while still close enough to Tokyo’s orbit to follow customers and capture activity across the broader metro area, gives it exposure to one of the most resilient and economically active parts of Japan.

Fourth is culture and risk. Ashikaga’s crisis didn’t just leave scars—it left discipline. Combined with Joyo’s historically conservative approach, Mebuki has a risk posture that can offer real downside protection when conditions turn.

And finally, there’s execution: the group has been hitting medium-term plan targets ahead of schedule, reinforcing the idea that this isn’t just a “two banks under one umbrella” story anymore, but a platform that’s starting to behave like one.

Stepping back, there’s also an investor angle: regional banks remain, in our view, underappreciated and undervalued—exactly the kind of corner of the market where “alpha” can still exist if fundamentals keep improving.

Bear Case

The pessimistic thesis is less about Mebuki specifically and more about the physics of Japan.

Demographics are the biggest headwind. A shrinking, aging population doesn’t just reduce loan demand over time—it can also change the deposit base. As retirees draw down savings, regional banks can face slow, grinding pressure on funding and local economic vitality.

Then there’s disruption. Even if relationship banking remains sticky, customer expectations are changing. Fintech players can skim profitable slices of activity, and megabanks can outspend regional banks on technology. Mebuki has invested, but the budget gap is real—and digitally savvy customers are the most willing to move.

There’s also concentration risk. Regional banks live and die by SMEs and local real estate. If the economy weakens or credit conditions tighten, that focus can become a vulnerability, particularly in markets where growth is already scarce.

Finally, competition is intensifying. Japan has been consolidating its banking system for decades, and now the pressure is shifting down to the regional tier. Mebuki isn’t the only group trying to build scale, and as more regional banks pair up, the fight for the best customers can get sharper, not softer.

KPIs to Watch

For investors tracking Mebuki’s story from here, three metrics matter most:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): As Japan’s rate environment continues to evolve, NIM tells you whether Mebuki is actually capturing the spread between lending yields and deposit costs. If this doesn’t move the right way in a rising-rate world, it’s a warning sign.

-

Fee Income Ratio: Mebuki’s whole “financial group” strategy depends on earning more from fees—securities, leasing, cards, and services—so it’s less dependent on rate cycles. A rising fee contribution is proof the diversification plan is working.

-

Loan Growth in Core Prefectures: Growth in Ibaraki and Tochigi, relative to the local economy and competitive pressure, is the health check for the core franchise. If loan volumes steadily decline, it suggests erosion where Mebuki is supposed to be strongest.

XII. Conclusion: The Regional Banking Renaissance

Seen from late 2025, Mebuki Financial Group looks like something Japan’s regional banking sector doesn’t produce often: a clear, working example of reinvention.

Two institutions with fundamentally different DNA—Joyo, disciplined and conservative; Ashikaga, nearly wiped out and rebuilt the hard way—found a structure that let them combine strength without forcing a false sameness. They got bigger, but they didn’t ask customers to give up the names they trusted. In a business where trust is the product, that decision mattered.

None of that makes the future easy. Japan’s demographics still lean against every regional lender. Digital transformation isn’t a one-time project; it’s an ongoing expense and a moving target. Competition keeps tightening as megabanks push outward and regional peers look for their own partners.

And yet, Mebuki is a reason to be at least cautiously optimistic. It shows that regional banks can gain scale without stripping away the local character that makes them defensible. The holding company “non-merger merger” offers a template other banks can copy. And management has left the door open to doing this again—welcoming additional banks into the group as consolidation continues.

Most importantly, Mebuki is evidence that regional banking can still work in Japan, even after decades that trained everyone to doubt it. Joyo’s century-plus of relationships. Ashikaga’s institutional memory of what happens when risk discipline disappears. A footprint in the Kanto ring around Tokyo, close enough to follow customers but still rooted in hometown economics. Those are advantages you don’t reproduce quickly—and you don’t download them.

For long-term, fundamentals-driven investors, Mebuki is one way to participate in the next phase of Japan’s regional banking consolidation—at a moment when the sector may finally be shifting from mere survival toward something closer to relevance again.

And the name says what the strategy is trying to do: Mebuki—new growth, sprouting after a long season. The open question is whether that bud becomes sustained growth, or a brief bloom before the deeper winter of demographic decline.

That answer will take years. But the story so far is already a statement: tradition can adapt, scars can become discipline, and in Japan’s regional economies, local roots can still support a renaissance.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music