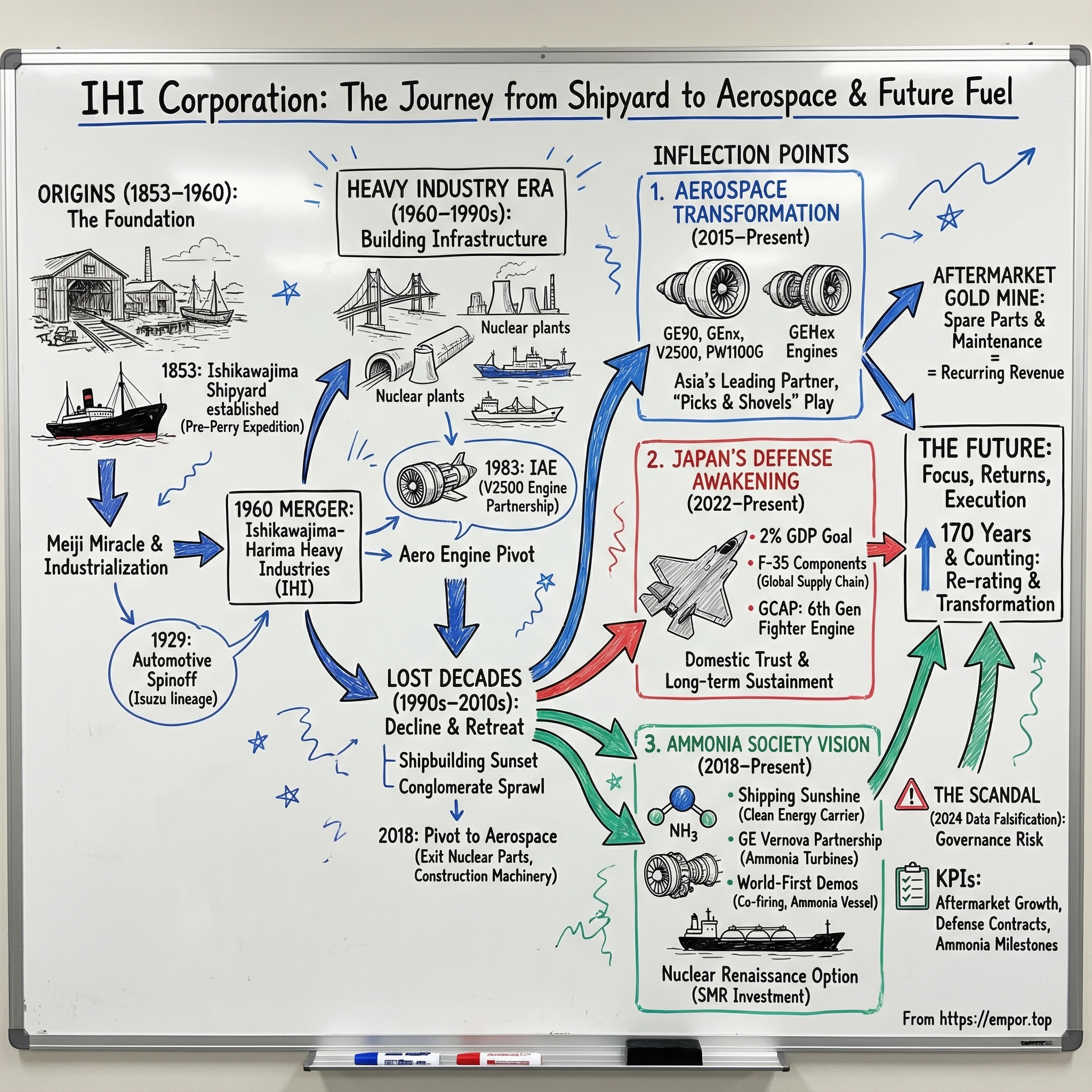

IHI Corporation: Japan's First Industrial Company and the Future of Flight & Fuel

I. Introduction: The Shipyard That Became Asia's Aerospace Powerhouse

In December 2022, Japan crossed a line it hadn’t crossed since World War II. For the first time in the postwar era, it agreed to co-develop a major fighter aircraft with partners that weren’t the United States. The countries were the United Kingdom and Italy. The program was the Global Combat Air Programme, a sixth-generation stealth fighter targeted to enter service by 2035. And the company responsible for the engines—the literal heart of the aircraft—was IHI Corporation.

If you’re outside Japan, there’s a good chance you’ve never heard the name. Yet IHI is now positioned to power one of the most advanced combat aircraft programs in the world, working alongside Rolls-Royce and Italy’s Avio Aero. That raises a simple question with a surprisingly long answer: how does a Japanese shipyard from the 1800s end up at the vanguard of modern aerospace?

IHI’s story begins in 1853 with the establishment of Ishikawajima Shipyard, widely regarded as Japan’s first modern shipbuilding facility. From the start, it wasn’t just building ships—it was helping build modern Japan, repeatedly taking core shipbuilding capabilities and applying them to new frontiers: heavy machinery, bridges, plant construction, and eventually, aero-engines.

Even the timing of its founding reads like foreshadowing. The shipyard was established by the Mito Domain under order from the Edo Shogunate, as Japan braced for the Perry Expedition and the rising pressure to compete with the Great Powers. It was founded one year before Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” arrived in Tokyo Bay and forced Japan to open. The Tokugawa Shogunate saw the storm coming and moved early. Japan needed modern naval capability—fast.

For most of the next 170-plus years, IHI looked like the definition of a Japanese heavy-industry conglomerate. It built ships and engines. It constructed bridges and tunnels. It made turbines, railway systems, turbochargers, industrial machinery, plant equipment, boilers, and space launch vehicles—an empire of metal, fire, and fabrication spread across the economy.

Then, in the 2020s, the plot accelerated. The stock tripled. Japan began a historic defense buildup. The energy transition moved from talking point to capital cycle. And IHI—after decades of seeming like a “does-everything” industrial—suddenly found itself sitting at the intersection of three of the most important forces in the world economy: aerospace, defense, and decarbonization.

In civilian jet engines, IHI became the leading partner in Asia to GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney—the world’s number one and number two jet engine manufacturers. It is Japan’s leading maker of jet engines, with a market share of between 60% and 70%. And on the defense side, it is the primary contractor and manufacturer for aircraft engines used by Japan’s Ministry of Defense.

This is the story of how Japan’s first modern shipbuilder transformed into arguably the most important aerospace company in Asia that most global investors have never heard of. It’s a story about timing and reinvention, about choosing the right partners, and about betting the company’s future on businesses with the highest barriers to entry. It’s also a story about Japan itself—a nation stirring after three decades of economic slumber and reasserting its industrial ambitions.

As we go, a set of themes will keep resurfacing: IHI as the ultimate “picks and shovels” play across defense, aerospace, and the energy transition; a company with exposure to every fighter jet engine in Japan’s fleet; deep partnerships with the world’s leading aerospace primes; and a vision for an “ammonia society” that could reshape how energy is produced, moved, and consumed.

II. Origins: The Birth of Japanese Industry (1853–1960)

The Meiji Miracle's Starting Point

Ishikawajima in 1853 wasn’t a brand name. It was a small island in Tokyo Bay—and a strategic bet.

That year, Lord Nariaki Tokugawa of Mito was appointed by the Tokugawa Shogunate to build a shipyard there. Japan’s feudal leadership could see the pressure building offshore. Western ships were showing up more often in Asian waters, and they weren’t just bigger—they carried a level of firepower and engineering Japan couldn’t afford to dismiss.

The Ishikawajima Shipyard quickly became more than a place to weld steel. It became a proving ground for Japanese industrial capability. Between 1854 and 1856, the yard built the warship Asahi Maru—one of Japan’s early, concrete steps toward modern naval power.

And then Japan did something few nations have ever pulled off. In less than four decades, it moved from isolation to industrial acceleration so fast it rewired the country’s place in the world. IHI’s predecessor wasn’t the whole story of Japan’s modernization, but it was one of the earliest and most visible engines of it.

By 1889, the operation formalized into a modern corporation: Ishikawajima Shipbuilding & Engineering Co., Ltd. It marked a shift that mirrored the Meiji Era itself—Japan translating state urgency into industrial institutions, and industrial institutions into national power.

The Automotive Spinoff Nobody Talks About

Here’s a twist that tends to surprise people: Isuzu traces part of its lineage back to IHI.

In 1929, Harima spun off its automobile section as Ishikawajima Automotive Works, which later became Isuzu through a series of mergers. The global truck brand didn’t emerge from a standalone “car company” story—it grew out of the same heavy-industry ecosystem that was building ships, engines, and machinery.

It also previews a pattern that will show up again and again in IHI’s history: the company’s ability to create world-class industrial capabilities—and, sometimes, to let them drift into separate orbits.

The 1960 Merger That Created a Giant

The modern IHI, as the world knows it, was forged in 1960.

That’s when Ishikawajima Heavy Industries—the successor to the original shipyard—merged with Harima Shipbuilding & Engineering to form Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries. Decades later, in 2007, the company adopted the simpler name IHI Corporation to strengthen its global brand.

This merger wasn’t just corporate housekeeping. It combined two old industrial houses into a single heavyweight—built for scale, breadth, and national ambition. It was the postwar Japanese industrial model at full strength: sprawling portfolios, long-term orientation, and a system of stability that outsiders would later criticize as too insulated from market discipline.

The combined company pushed into a wide range of high-complexity projects—large vessels, standardized multipurpose dry cargo carriers in the 1960s, the world’s first barge-mounted polyethylene plant, and increasingly powerful engines.

Most importantly, this era quietly planted the seeds of what would become IHI’s defining advantage. The company wasn’t only building ships anymore. It was developing jet engines—an expertise that, in 1960, looked like just another line item in a diversified industrial catalog.

In hindsight, it was the beginning of everything.

III. The Heavy Industry Era: Building Japan's Infrastructure (1960–1990s)

Nuclear Ambitions

In postwar Japan, energy independence wasn’t a policy goal. It was an obsession. The country had few meaningful domestic reserves of oil, coal, or natural gas, and the lessons of resource constraint were still painfully recent. Nuclear power promised something Japan wanted more than anything: control.

In 1969, IHI built Mutsu, Japan’s first nuclear-powered ship, using reactors from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. The project was a statement of intent—proof that IHI was willing to take on the hardest engineering problems on the board. Mutsu later became controversial after radiation leakage issues delayed its service for years. But even in that mess, IHI expanded its know-how in nuclear containment and high-spec systems engineering.

That experience would echo decades later, when IHI invested in NuScale Power, the American small modular reactor company. But we’ll come back to that.

The Aero Engine Pivot: IAE and International Partnerships

The most consequential move IHI made in the modern era came in the 1980s, and it wasn’t about going it alone.

Jet engines are one of the most brutal businesses on earth: immense upfront R&D, punishing certification regimes, and a tiny number of customers who never forget a failure. Trying to build a world-class engine program independently would have meant decades of catch-up and an eye-watering bill. Instead, IHI chose a smarter route—become the partner the global giants couldn’t do without.

In 1983, International Aero Engines, or IAE, was founded to develop a new turbofan for the 150-seat single-aisle market: the V2500. It was a multinational collaboration, bringing together Pratt & Whitney in the United States, Rolls-Royce in the United Kingdom, MTU Aero Engines in Germany, and Japan’s participation through the Japanese Aero Engine Corporation, or JAEC—a consortium that included IHI.

JAEC contributed the low-pressure compression system. In other words: not a cosmetic part. A core module, a critical piece of performance and reliability—exactly the kind of workshare that forces everyone else in the program to take you seriously.

The V2500 went on to become a major success: one of the highest-volume commercial engine programs still in production, and one of the most successful in aviation history. More importantly, it did something bigger than sell engines. It put Japan—and IHI—squarely inside the global aerospace supply chain.

And it revealed a playbook IHI would return to again and again: don’t pick a fight with the incumbents. Attach yourself to them, earn the hardest work, and become indispensable.

The Conglomerate Sprawl

At the same time, IHI was still living the full Japanese conglomerate life.

During the 1980s, heavy industry and plant technology became the dominant source of earnings, accounting for close to 70% of the company’s income. But the portfolio wasn’t getting tighter. It was getting broader—almost comically so.

IHI established IHI Granitech Corporation to advance stone processing for construction. It formed Ishikawajima Systems Technology Company for systems engineering in electronics and computers. It even created Joy Planning Company to operate fitness clubs and sports facilities.

Yes—fitness clubs.

This was the logic of the era: big industrial groups kept expanding into adjacent businesses, partly because growth was expected, and partly because lifetime employment meant you found new work for your people. In hindsight, it’s also what later got labeled “conglomerate disease”—a company doing a little bit of everything, but losing the sharp edge that makes any one business truly great.

IHI even entered real estate development, putting prime idle land around Tokyo Bay to work. Ironically, those holdings would become quite valuable. But value isn’t the same as advantage. And real estate wasn’t where IHI’s unique capabilities lay.

By the end of this period, the company had world-class engineering in pockets—especially in aerospace. But as a whole, it was starting to drift.

IV. The Lost Decades: Decline and Near-Death (1990s–2010s)

Shipbuilding's Sunset

The business that gave birth to IHI nearly 140 years earlier was fading fast. Korean shipyards—and later Chinese ones—were taking share with lower costs and heavy state support. For Japanese builders, this wasn’t a cyclical downturn. It was a structural squeeze.

IHI’s response wasn’t a bold comeback. It was consolidation: a long, slow retreat designed to survive.

In 1995, Marine United was established jointly with Sumitomo Heavy Industries.

It was a pragmatic move, but it also marked a psychological shift. Two storied shipbuilders weren’t teaming up to dominate; they were teaming up to endure.

By 2013, the retreat became unmistakable. IHI Marine United merged with Universal Shipbuilding Corporation, owned by the steel company JFE Holdings, to form Japan Marine United Corporation (JMU), with IHI remaining a shareholder.

That phrasing matters: remained a shareholder. IHI went from being a shipbuilder to owning a stake in shipbuilding.

Then came the next step down the ladder. In March 2020, JMU (49% owned) agreed to merge with Imabari Shipbuilding (51% owned) into a joint venture named Nihon Shipyard. The agreement took effect in January 2021.

Alongside that, Imabari bought 30% of JMU, while IHI and JFE Holdings each kept 35% of JMU’s capital. The combined entity became one of the world’s largest marine engineering and shipbuilding groups—and IHI’s role was, once again, as a shareholder.

Founder, then operator, then partner, then minority owner in a web of joint ventures. The decline of Japanese shipbuilding is a big story, but you can see the whole arc inside IHI’s cap table.

The Conglomerate Discount

As shipbuilding weakened, the rest of IHI didn’t snap into focus. For decades, it traded like a classic Japanese conglomerate: hard to analyze, harder to trust, and perpetually valued below what its assets might have been worth on paper.

The culprits were familiar. Cross-shareholdings that reduced outside pressure. Capital allocation that favored stability over returns. And a portfolio so broad it blurred the company’s identity—great businesses buried inside a structure that made the whole thing feel uninvestable.

Still, there were signs IHI knew where the future was headed. In 2000, it purchased Nissan Motor’s Aerospace and Defense divisions and established IHI Aerospace Co., Ltd. Even as other operations stagnated, IHI was quietly accumulating aerospace capability—signaling that it viewed flight and defense as growth arenas worth leaning into.

And then came the selling.

In 2016, IHI sold all shares of its wholly owned IHI Construction Machinery Limited to Kato Works Company Limited.

Construction machinery was out. More exits would follow.

The 2018 Decision: Betting on Aerospace

In 2018, IHI made one of the most consequential choices of its modern history: it stopped manufacturing nuclear reactor parts and shifted its focus toward aircraft parts. Japan Steel Works became the sole Japanese supplier of reactor parts.

This wasn’t a minor portfolio tweak. It was a bet—especially in a post-Fukushima Japan where nuclear was controversial, but not necessarily finished. Walking away meant giving up a business that could have returned.

But IHI was looking at a different curve: the global aviation fleet. Planes would keep being built, and the engines on those planes would need parts, service, and overhaul for decades. Aerospace didn’t just promise growth. It promised longevity—and recurring revenue.

In effect, IHI was choosing the industries where complexity protects you. Where qualification takes years. Where once you’re designed in, you tend to stay in.

It was the moment IHI began turning from a sprawling heavy-industrial legacy company into something sharper: an aerospace-and-defense specialist hiding inside an old conglomerate shell.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Aerospace Transformation (2015–Present)

Doubling Down on Jet Engines

By the mid-2010s, IHI’s “bet on complexity” started to show its shape. The company wasn’t trying to out-GE GE, or out-Pratt Pratt. It was doing something more realistic, and in aerospace, often more powerful: becoming the partner the giants rely on.

IHI develops, manufactures, and maintains aero engines through joint projects with GE Aerospace, Pratt & Whitney, and Rolls-Royce, as well as through select in-house development. But the real story is where it shows up inside the world’s most important engine programs.

IHI has workshare on engines including the GE Aerospace CF34, GE90, GEnx and Passport 20, plus the V2500 and the PW1100G.

Translated into the real world: IHI has meaningful exposure to engines that power Boeing 777s (GE90), the 787 and 747-8 (GEnx), regional jets (CF34), business jets (Passport 20), and huge swaths of the Airbus A320 family (V2500 and PW1100G). These are not vanity projects. They’re the engines that rack up flight hours every day across the global fleet.

The V2500 itself—born from that international consortium model—was developed through collaboration among Japan, the U.S., the U.K., and Germany, and went on to be installed on Airbus A319, A320, and A321 aircraft.

Inside IHI, the Aero Engine, Space & Defense unit became the sharp end of the spear. It developed and produces the world’s longest low-pressure shaft and low-pressure turbine disks for GE Aerospace’s GE9X, produces multiple components for the GEnx, and is a key contributor to Pratt & Whitney’s PW1000 program.

The GE9X powers Boeing’s 777X, the largest twin-engine aircraft in the world. And when you’re trusted to make something as critical as the low-pressure shaft—especially one described as the world’s longest—you’re not a supplier on the margins. You’re part of the engine’s backbone.

The Aftermarket Gold Mine

Now for the part that makes aerospace such a different economic animal.

Jet engines are like printers: the upfront sale matters, but the real annuity is everything that happens after—spare parts, maintenance, repair, and overhaul. Engines don’t just fly; they get inspected, refurbished, and rebuilt over and over again for years. If you’re designed into the program and qualified for the work, you can live off that installed base for decades.

That’s exactly what began to show up in IHI’s numbers. The aerospace division of Japan’s IHI Group saw revenues for the nine months ended 31 December 2024 triple, helped by the sale of spare parts for engines.

Tripled—driven by demand for spare parts. This is the “lifecycle business” investors obsess over: recurring, high-value work that grows as fleets age and flight hours accumulate.

The Aero Engine, Space and Defense unit’s nine-month revenue was Y377 billion ($2.4 billion), up from Y130 billion a year earlier.

And this wasn’t happening in a corner of the company anymore. Overall, the aerospace unit contributed 32.8% of IHI Group’s overall revenues for the nine months ended 31 December 2024. At the Japan Aerospace show in October 2024, the head of the aerospace unit, Atsushi Sato, told FlightGlobal that IHI views aerospace as a key growth area and expects revenue to double by 2030.

A third of company revenue coming from aerospace is already a different IHI than the market was used to. Management saying it can double again is the signal: this isn’t a side business. It’s becoming the center of gravity.

Why IHI Won in Asia

So why IHI? Why not Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, which is bigger? Why not Kawasaki Heavy Industries? What gave IHI the inside track to become Asia’s leading aerospace partner?

Part of the answer is time. IHI has been making jet engine components since the 1950s, and its relationships with GE and Pratt & Whitney span decades. In aerospace, reputation is built in flight hours and failure rates. Trust is earned slowly—and once you have it, it’s incredibly hard for someone else to take it away.

IHI also leveraged its manufacturing base into something airlines and OEMs desperately want: local, high-quality maintenance capability. With experience and production technologies built over generations, IHI provides maintenance across engine types and is considered Asia’s core maintenance center.

That phrase matters. Airlines don’t want to ferry engines halfway around the world for service if they can avoid it. They want a trusted partner nearby, with the tooling, the people, and the certifications already in place. For IHI, this isn’t just service revenue. It’s strategic stickiness.

And the alignment with Western partners runs deeper than “supplier.” In the GE90 program, for example, Snecma of France, Avio SpA of Italy, and IHI Corporation of Japan are revenue-sharing participants.

Revenue-sharing is exactly what it sounds like: IHI participates in the economics of the program as engines sell and as they generate aftermarket demand. When the OEM wins, IHI wins. That’s a very different relationship than simply shipping parts on a purchase order.

The Partnership Model

What’s remarkable is how durable these partnerships have become. In November 2025, the IAE partnership reaffirmed its commitment to developing the next generation of engines, evolving the technologies required for the most advanced and efficient Geared Turbofan (GTF) technology for the next generation of commercial aircraft.

“For more than four decades, IAE has enjoyed an enduring partnership and has delivered and supported two of the most important commercial engine programs in history, the V2500 and the GTF engines,” said JAEC Chairman Tsugio Mitsuoka.

And the V2500’s footprint shows why that matters. The program surpassed 300 million flight hours earlier in 2025, powers approximately 2,800 aircraft, and serves more than 150 operators across passenger, cargo, and military missions.

That’s the installed base. That’s the annuity. And for IHI, it’s proof that the “partner to the giants” strategy didn’t just get them into aerospace. It got them into the compounding part of aerospace—where the engines keep flying, and the cash keeps coming.

VI. Inflection Point #2: Japan's Defense Awakening (2022–Present)

The Historic Pivot

For three quarters of a century after World War II, Japan lived with a kind of unwritten ceiling on defense: about 1% of GDP. Its pacifist constitution, drafted under U.S. occupation, narrowed the country’s military latitude. And the U.S. alliance carried much of the deterrence burden.

Then the world changed faster than the old framework could keep up. China’s rise, North Korea’s missile program, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced a blunt reassessment of what “security” meant in the Indo-Pacific.

In December 2022, then Prime Minister Kishida Fumio codified the shift. In new national security documents, Japan committed to raising defense spending to 2% of GDP by fiscal 2027—following NATO’s now-standard benchmark.

This wasn’t a marginal adjustment. It was a doubling in five years. In yen terms, it translated into a step-change in budgets, procurement, and—most importantly—sustainment.

Japan’s cabinet later approved a Fiscal Year 2025 supplementary budget that included an additional $7 billion, or 1.1 trillion yen, in defense spending. If approved by Parliament, that would bring total FY2025 defense spending to about $70 billion, or 11 trillion yen—pushing Japan above 2% of GDP earlier than the Kishida administration’s original FY2027 goal.

And the target didn’t stop feeling like a target. The U.S. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, Elbridge Colby, has since called on Japan to go further, to 3% of GDP.

For defense contractors, this was the kind of inflection point that only comes around once in a career. For IHI, it was even more specific: Japan’s defense awakening was an engine story.

IHI's Role in Every Fighter Jet

IHI’s position inside Japan’s defense ecosystem is unusually deep. It’s involved in the production and aftermarket for virtually every fighter jet engine flown by the Japan Air Self-Defense Force—meaning it doesn’t just help build the engines, it earns the long tail of keeping them running.

Take the F110, which powers the F-2 support fighter, jointly developed by the United States and Japan. IHI conducted mass production as the prime contractor through a license with General Electric.

But IHI isn’t just a licensed manufacturer. It also builds engines from Japanese original technology. The F3 compact turbofan mounted on the T-4 training jet is one example—and it matters because it signals something rare in modern aerospace: an indigenous engine development capability that didn’t disappear into “assembly only.”

F-35: Manufacturing for the World

In April 2024, IHI took a step that moved it from “Japan’s supplier” to “the program’s supplier.”

On April 26, IHI began shipping Stage 1 Integrally Bladed Rotors to Pratt & Whitney in the United States. These rotors are components for the F135 turbofan engine installed on the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. They were manufactured at IHI’s Soma Aero-Engine Works in Fukushima Prefecture—marking the first time these parts were mass-produced there for the global market.

Eighteen countries participate in the F-35 program. That means this isn’t about supporting Japan’s own fleet. It’s about feeding the supply chain for the world’s most widely deployed advanced fighter.

And the exclusivity is real: apart from Pratt & Whitney, only IHI has the manufacturing capability for these high-value-added rotors. In the defense industrial world, that’s as close as you get to being designed in at the highest tier.

IHI also completed a facility at its Mizuho Works in Tokyo: a regional depot to maintain F135 turbofan engines, including those used by the Japan Air Self-Defense Force. It’s the first regional depot outside those run directly by F-35 partner nations.

With Australia, Japan now forms one of five global regional depots for F-35 engine maintenance. Over time, F-35 operators across the Indo-Pacific gain a powerful incentive to route sustainment through IHI’s orbit.

GCAP: The Sixth-Generation Fighter Program

Then there’s the program that opened this story.

On 9 December 2022, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy announced they would merge their separate sixth-generation fighter efforts into a single project: the Global Combat Air Programme. It combined the U.K.-led Tempest initiative—developed with Italy—with Japan’s Mitsubishi F-X.

In Japan, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries serves as prime contractor. Mitsubishi Electric handles electronics. And IHI handles the engines.

For a sixth-generation aircraft expected to define air combat well into the middle of this century, “handles the engines” is a starring role. Propulsion isn’t just thrust; it’s range, thermal management, signature control, and power generation for the rest of the aircraft’s systems. If you’re the engine company, you’re shaping the platform.

GCAP also mattered geopolitically. The project marked the first time Japan cooperated with countries other than the United States to meet a major defense requirement. Japan reportedly chose European partners in part because the U.S. was seen as inflexible and unwilling to treat Japan as an equal development partner. For IHI, that opened room to develop cutting-edge propulsion technology in an international collaboration outside the usual constraints of U.S. export control regimes.

And IHI didn’t arrive at GCAP by accident. While Mitsubishi Heavy Industries may be Japan’s primary industrial partner overall, Japan’s fighter engine know-how has long lived inside IHI. The company developed the XF5 turbofan that powered the MHI X-2 Shinshin experimental fighter in the 2010s. It also developed the more advanced XF9 afterburning engine.

“We’ve conducted research and development to allow us to join the upcoming international collaboration with a good presence,” Sato said.

That line is doing a lot of work. It tells you IHI’s real strategy: don’t just participate. Show up with technology serious enough that your partners have to treat you like a peer.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Ammonia Society Vision (2018–Present)

Why Ammonia, Why Now?

Japan’s energy problem is simple to describe and hard to solve: it’s a highly developed economy with very little domestic fuel. It imports nearly all its oil, coal, and natural gas. And after the Fukushima disaster in 2011, much of Japan’s nuclear fleet went offline, forcing the country even deeper into fossil fuel dependence.

Renewables are growing, but geography isn’t doing Japan any favors. The country is mountainous, densely populated, and short on the wide-open land and consistent wind corridors that make massive buildouts easier in places like the U.S. or Australia.

So IHI went looking for an energy carrier that could move clean power across oceans at industrial scale. Their answer is ammonia: a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen that can store energy densely, ship like a commodity, and—if you can burn it properly—produce power without carbon dioxide emissions.

That’s the core of IHI’s “ammonia society” vision. Make ammonia the medium for moving renewable energy from where it’s abundant to where it’s needed. Or, as IHI puts it: “shipping sunshine.”

The GE Vernova Partnership

To make that vision real, IHI needs to do something that sounds straightforward and is brutally hard in practice: combust ammonia reliably in large gas turbines that were designed for natural gas.

On Christmas Day 2023, IHI and GE Vernova signed a joint development agreement to do exactly that. Over the next two years, they planned to develop and validate the combustion technology, with the goal of a commercially available product by 2030.

The aim is ambitious: a gas turbine capable of burning up to 100% ammonia. Under a Joint Development Agreement signed in 2024, the two companies continued developing a new combustor designed to enable GE Vernova’s F-class turbines to run on ammonia under real operating conditions—pressure, temperature, air flow, fuel flow, the whole unforgiving envelope that makes lab demos collapse in the field.

IHI wasn’t starting from zero. The company had already developed a small gas turbine, the IM270, with an output of 2MW that runs on 100% ammonia. The hard part now is scaling that success from a few megawatts to the hundreds of megawatts utilities need.

And the prize isn’t just “new turbine sales.” GE Vernova notes that more than 1,600 F-class turbines are deployed worldwide. If IHI and GE Vernova can deliver a credible retrofit pathway, they aren’t just selling a product—they’re offering a way to decarbonize an enormous installed base without rebuilding the global power system from scratch.

World-First Demonstrations

In April 2024, IHI and JERA put a real-world marker down.

At Hekinan Thermal Power Station Unit 4 in Aichi Prefecture—one of Japan’s largest commercial coal plants—they achieved what they described as the world’s first demonstration of large-volume ammonia substitution at scale. On April 10, the plant successfully operated at its rated one-gigawatt output with 20% of its fuel replaced by ammonia.

The emissions profile was the point. The companies confirmed that carbon dioxide emissions fell by around 20%. Sulfur oxide emissions were down about 20%. Nitrogen oxide emissions were equal to or less than the levels from coal-only operation. And emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas, were undetectable.

In other words: it worked, and it worked cleanly.

IHI’s next steps were straightforward in concept and difficult in execution: use what they learned to push the co-firing ratio beyond 50%, and develop burners that can ultimately support 100% ammonia combustion. The progression matters because it keeps existing infrastructure in play. If ammonia can scale, Japan doesn’t need to scrap its thermal fleet to cut emissions—it can convert it.

The World's First Ammonia-Fueled Vessel

Then IHI took ammonia off the power plant floor and into the water.

The world’s first commercial-use ammonia-fueled vessel, Sakigake—“pioneer” in Japanese—completed a three-month demonstration voyage operating as a tugboat in Tokyo Bay. The vessel was completed on August 23, 2024 by Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (NYK) and IHI Power Systems Co., Ltd. (IPS).

During the demonstration, Sakigake achieved a greenhouse-gas emissions reduction of up to approximately 95% compared with heavy fuel oil. After the voyage, it moved into commercial operations in Tokyo Bay, where it will keep building the kind of practical, operational know-how that new fuels always need before they become mainstream.

IHI built the engine. And in shipping—an industry that’s famously hard to decarbonize—that’s a meaningful proof point.

The Nuclear Renaissance Option

Even as IHI pushed ammonia, it didn’t walk away from nuclear.

The company has long supplied major components for nuclear power plants, and it positioned itself for a potential nuclear resurgence by investing in small modular reactors. IHI decided to enter the SMR market by investing in NuScale Power, LLC, a U.S.-based developer of SMR technology, committing $20 million.

“Strategic partnership with an innovative SMR technology developer such as NuScale is a great opportunity for us,” said Hiroshi Ide, President and Chief Executive Officer of IHI Corporation. “IHI wants to support the move toward a carbon-neutral economy, and NuScale's technology is safe, clean, reliable and closest to commercialization among its competitors.”

For IHI, SMRs sit in the same mental bucket as ammonia: another pathway to carbon-neutral energy that can coexist with, rather than replace, the rest of the transition. And it ties back to the company’s history—because once you’ve built Japan’s first nuclear-powered ship, you don’t forget how to think in systems where safety, containment, and high-spec engineering are the whole game.

VIII. The Scandal: The 2024 Data Falsification Crisis

What Happened

Just as IHI was starting to look like a re-rated company—defense tailwinds, aerospace momentum, a bold decarbonization narrative—another, very old Japan story reappeared: long-running quality misconduct hiding in plain sight.

After a whistleblower report in February 2024, IHI disclosed on April 24, 2024 that Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism was investigating its subsidiary, IHI Power Systems Co., for falsifying engine data going back to 2003. The scope was staggering: test data for 4,361 engines had been manipulated, affecting customers around the world.

Most of the engines—4,215 of them—were marine engines sold domestically and overseas. Authorities began probing IHI Power Systems plants in Niigata and Ota. And IHI said that 2,058 engines did not meet the specifications set under customer contracts.

This wasn’t a one-off corner-cutting incident. It was a system that ran for roughly two decades.

According to reports attributed to Japanese officials, an employee told investigators that everyone involved in engine test runs knew the data was being falsified. And in IHI’s own interviews with relevant personnel, people described how fuel consumption values were altered to look better or to smooth out variation—then justified as simply continuing what had been done before.

Some interviewees said they were carrying on the procedures of their predecessors. That one line captures the core failure: not just weak controls, but a workplace culture where inherited practice outranked compliance, and where “this is how we do it” substituted for accountability.

Pattern Recognition

The fallout didn’t stay contained at IHI.

IHI’s disclosure helped trigger broader scrutiny across Japan’s industrial manufacturing base. Other companies were pushed to audit their own practices, and Japan’s Transport Ministry found similar issues across the industry. The scandal was cited as part of a wider pattern that later drew in other manufacturers, including Hitachi Zosen and Kawasaki Heavy Industries.

And it didn’t stop with engines. Japan has faced similar irregularities in automotive certification, where Toyota, Mazda, Suzuki, and Yamaha were found to have submitted incorrect or manipulated test data. In June 2024, Japanese Transport Ministry officials raided Toyota’s headquarters, and Toyota suspended production of at least three models.

That context matters because it reframes the IHI episode. It wasn’t just “one bad subsidiary.” It looked like another example of how world-famous manufacturing cultures can still produce world-class products—and also tolerate broken processes for far too long.

For investors, the uncomfortable question was obvious: if IHI Power Systems could run this playbook for decades, what does that imply about the rest of the group? Is the aerospace-and-defense business—the crown jewel—immune from the same cultural drift?

IHI said it identified no safety issues with the engines involved. But even when safety isn’t compromised, credibility is. And in engineering businesses, credibility is a form of capital.

There was, however, one signal pointing the other way: the whistleblower mechanism worked. An employee reported the misconduct, and the report triggered an investigation that forced the issue into the open. That doesn’t erase what happened—but it does suggest that IHI’s governance is changing enough that problems can surface, even when they’ve been normalized for years.

IX. The Hitachi Playbook: Corporate Transformation

Why Hitachi Matters

Hitachi is the most useful recent precedent for understanding what might be happening at IHI, because it answers two questions at once: how much can a century-old Japanese conglomerate actually change—and how long does it take before anyone believes it?

In 2008, Hitachi posted what was then the largest loss in Japanese manufacturing history. It was sprawling, unfocused, and losing money across too many fronts at once. The company made everything from nuclear reactors to consumer electronics, but the portfolio didn’t add up to a coherent strategy.

Then, over the next decade, Hitachi did something that Japanese industrial giants weren’t supposed to do: it chose. It sold off business after business, including its TV and mobile phone operations. It bought assets that reinforced what it wanted to be good at. And it started speaking a language that would have sounded out of place a generation earlier—cash generation, capital discipline, and returns to shareholders.

In its current mid-term management plan, Hitachi says it has grown dividends steadily, citing an annual dividend growth rate of 12% over the past 13 years.

It also leaned into buybacks, repurchasing 300 billion yen of shares across the past two fiscal years, with plans to repurchase another 200 billion yen in fiscal 2024.

Today, Hitachi is widely seen as a “shareholder-friendly” Japanese blue chip. Its stock has meaningfully outperformed the broader market. But the key point isn’t that it worked—it’s that it took a long time, and it required real change, not slogans.

What IHI Is Doing

IHI looks like it’s starting down a similar road—earlier in the process, with less investor trust banked, but with a familiar set of moves.

Portfolio simplification: IHI has been shrinking the parts of the company that no longer fit. Shipbuilding has effectively become a minority stake inside a joint venture structure. Construction machinery has been sold. And it halted nuclear reactor parts manufacturing. The direction is clear: fewer businesses, more focus.

Focusing on high-barrier businesses: instead of trying to be good at everything, IHI is leaning into categories where competitive moats are real. Commercial jet engines are protected by certification, decades-long customer relationships, and massive capital requirements. Defense has similar barriers, plus the stickiness of national procurement and long-term sustainment. These are areas where IHI’s existing position is hard to dislodge.

Expanding lifecycle/aftermarket revenue: the surge in aerospace revenue driven by spare parts isn’t just a nice quarter. It’s the economic model IHI wants more of—recurring revenue from maintenance and repair, which tends to be steadier and higher value than one-time equipment deliveries.

Cross-shareholding unwind and real estate monetization: old-school Japanese conglomerates accumulated cross-shareholdings to cement relationships, not maximize returns. Unwinding those holdings can release trapped capital. The same goes for real estate gathered over generations of industrial expansion—valuable, but often inert on the balance sheet. Turning that into cash can fund growth, strengthen the balance sheet, or eventually flow back to shareholders.

The “value unlock” story here is still new. It’s only been a few quarters since this shift has started to show up clearly, and markets don’t hand out trust quickly—especially to a company with IHI’s messy history. That’s exactly why the comparison to Hitachi matters: once these transformations become undeniable, the stock is usually already repriced. The opportunity, if it exists, tends to live in the uncomfortable middle—when the strategy is changing, but the reputation hasn’t caught up yet.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers: The Competitive Analysis

Aerospace & Defense: A Fortress Business

Threat of New Entrants (Very Low): In jet engines, “competition” isn’t a clever design and a factory. It’s decades of engineering scars, a mountain of certification work, and reliability proven over vast numbers of flight hours before airlines, militaries, and regulators will trust you. IHI has been building this muscle since the 1950s. A startup can’t shortcut that timeline, and an emerging-market entrant can’t buy credibility overnight.

Supplier Power (Moderate): Aerospace and defense depend on specialized materials and tightly controlled components, so suppliers do matter. But IHI’s scale, long program lives, and long-running relationships help balance the equation. And once a supply chain is qualified for a given engine program, it tends to stay in place—because changing anything is slow, expensive, and risky.

Buyer Power (Moderate): Airlines can negotiate hard when they’re buying aircraft and engines. But the balance shifts after delivery. Once an airline commits to a given engine type, it’s locked into a world of approved parts and certified maintenance. Switching isn’t like swapping vendors; it effectively means changing aircraft strategy, training, spares, tooling, and operations. That reality protects the ecosystem that IHI sits inside.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): For commercial aviation at scale, there is no true substitute for jet engines today. Electric propulsion is still confined to small aircraft concepts, and hydrogen faces major storage, infrastructure, and engineering hurdles. Over the time horizon that matters for today’s installed base, the turbine engine remains the center of gravity.

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate): The engine market is an oligopoly, dominated by GE Aerospace, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, and Safran. But IHI’s position is unusual: it competes less by trying to dethrone them and more by embedding itself alongside them, program by program, module by module. That changes the nature of rivalry. For IHI, the fight is usually for workshare, quality, and trust—not for the final brand on the nacelle.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Switching Costs (Strong): Switching costs are the quiet superpower of aerospace. Airlines standardize around engine families for maintenance efficiency, and once an engine wins a slot on a major aircraft program, it tends to stay there for decades. IHI’s workshare on platforms like the V2500 and PW1100G translates into a long runway of recurring revenue as those engines age and cycle through overhaul.

Scale Economies (Moderate): Volume matters in manufacturing: higher throughput drives learning curves, spreads fixed costs, and improves unit economics. IHI benefits from being the leading Asian partner integrated into major global programs, though it’s still smaller than the Western prime OEMs.

Network Effects (Limited): This isn’t software; there’s no classic “more users attracts more users.” But there is an indirect compounding effect. The more programs IHI is embedded in, the more credible it becomes as a partner on the next program—because it brings proven processes, certified capabilities, and a track record customers can underwrite.

Counter-Positioning (Strong): IHI’s strategy—be indispensable rather than confrontational—creates a kind of counter-positioning. In theory, primes could try to internalize more of the work. In practice, bringing complex workshare in-house would introduce cost, risk, and disruption into programs where reliability is everything. The partnership is often the rational equilibrium.

Cornered Resource (Moderate): In defense, domestic trust is a resource. Japan’s Ministry of Defense needs suppliers it can rely on for decades, through geopolitical shocks and supply-chain stress. IHI’s long history and deep integration into Japan’s defense-industrial base give it a legitimacy that is difficult for an outsider to replicate.

Process Power (Developing): In ammonia combustion, IHI is trying to build process power: hard-earned, organizational capability that improves with time and iteration. A decade of investment and real-world demonstrations create a learning advantage—but it’s still early, and success depends on scaling from “works” to “works at utility scale, reliably, economically.”

Branding (Limited): IHI isn’t a consumer brand, and in aerospace the brand that matters most is performance, reliability, and program trust. IHI’s name carries weight in Japan and among industry insiders globally, even if it’s largely unknown to the public.

Key Risks

Customer Concentration: IHI’s aerospace engine business is deeply tied to its partnerships with GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney. That concentration is a strength when the relationships are healthy—and a serious vulnerability if priorities shift, disputes arise, or workshare changes.

PW1100G Issues: IHI has a 15% workshare in the PW1100G program for the Airbus A320neo family. That engine has faced durability problems that have driven heavy maintenance requirements. More maintenance can boost aftermarket demand, but it can also create reputational risk and, depending on outcomes, potential financial exposure.

Governance Concerns: The 2024 data falsification scandal at IHI Power Systems raised uncomfortable questions about controls and culture. The key issue going forward isn’t just what happened—it’s whether IHI can prove the problem was contained, addressed, and not mirrored elsewhere in the group.

Japan-Specific Risks: IHI’s defense upside is tightly linked to Japanese government policy and spending. A reversal in Japan’s security posture seems unlikely in the current environment, but the dependency is real—and it concentrates political risk.

Technology Risk in Ammonia: The ammonia vision is bold, but scaling is unforgiving. Ammonia has handling challenges because it’s toxic, its economics are uncertain, and its role in energy systems depends on policy, supply chains, and cost curves that may move slower than hoped. Even if the technology works, commercialization at utility scale could take longer than IHI expects.

XI. The KPIs That Matter

If you want to follow IHI like a long-term fundamental investor, don’t get lost in the sprawl. Watch three simple scoreboards that tell you whether the transformation is actually working.

1. Aerospace Aftermarket Revenue Growth

The lifecycle business is where IHI earns its best money. Not just building parts for engines, but keeping engines flying: spare parts, maintenance, repair, overhaul.

So don’t just track “aerospace revenue.” Track what it’s made of. How much is tied to new equipment deliveries, and how much is coming from spare parts and maintenance? If the aftermarket portion keeps growing quarter after quarter, that’s the clearest signal that IHI’s installed base is turning into recurring cash flow.

Management has said it expects aerospace revenues to double by 2030. That’s the benchmark. Everything else is noise.

2. Japanese Defense Contract Value

Japan’s defense build-up is a once-in-a-generation demand shock for the domestic industrial base, and IHI sits in the propulsion layer where sustainment tends to compound.

As the defense budget climbs toward 2% of GDP—and possibly beyond—the question isn’t whether spending rises. It’s whether IHI consistently captures it. The best way to see that is through the value of defense contracts, the defense order backlog, and the split between new production and the long-tail work: maintenance and aftermarket support.

And then there’s GCAP. Watch the milestones: contract awards, development progress, and test achievements. Those are the early signals of whether the engine role IHI “won” in 2022 turns into real revenue later.

3. Ammonia Technology Commercialization Progress

Ammonia is the biggest swing—and the least proven. The technology story is compelling, but commercially, this is still early.

So the KPI here isn’t excitement. It’s milestones. Look for the 2027 target for commercializing the 2MW ammonia gas turbine. Watch progress on the GE Vernova partnership’s large-scale combustor development. And most importantly, look for actual commercial orders for ammonia co-firing equipment.

If those orders arrive, ammonia could meaningfully change IHI’s growth profile. If they don’t, it stays what it is today: a significant R&D bet with an uncertain payoff.

XII. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

Japan’s defense awakening is not a one-budget-cycle story. After roughly seven decades of keeping military spending on a tight leash, Japan is now in catch-up mode—and catch-up, in defense, tends to run for a long time. IHI sits in a particularly advantaged spot inside that spend: it’s the dominant supplier of fighter jet engines to Japan’s military, it earns the long tail of maintenance and overhaul, and it has a marquee role on GCAP. If Japan is going to spend more on airpower, IHI is positioned to touch a meaningful portion of those yen.

At the same time, commercial aviation continues to normalize after the pandemic. Boeing and Airbus together have backlogs stretching years into the future. Those aircraft need engines, and engines need high-spec components that can’t be swapped on a whim. IHI’s workshare across many of the most important engine programs gives it exposure not just to new aircraft production, but to decades of aftermarket demand once those engines enter service.

Then there’s ammonia. If IHI’s “ammonia society” vision actually scales, it puts the company in the middle of a very rare thing: a new global fuel infrastructure cycle. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry projects the country could need 30 million tons of ammonia annually by 2050 for power generation alone. If ammonia co-firing and ammonia-capable turbines become a mainstream decarbonization path, IHI’s early lead in combustion technology could translate into real leverage—selling equipment, winning retrofits, and potentially licensing know-how.

Finally, the market could simply start believing the transformation. If IHI keeps simplifying the portfolio, unwinding cross-shareholdings, monetizing non-core assets, and returning capital to shareholders, the valuation can change even without heroic operating assumptions. The story investors have historically told themselves—“sleepy Japanese conglomerate”—gets replaced with a different one: a focused aerospace, defense, and energy-technology company. That kind of narrative shift is what drives multiple expansion.

The Bear Case

The most obvious risk is that the 2024 data falsification scandal wasn’t a contained subsidiary problem—it was a symptom. If similar issues were ever discovered in aerospace or defense, the damage would be far larger. In safety-critical industries, trust is everything, and credibility can disappear faster than it was built.

A second risk is that IHI gets pulled into the downside of its partnerships. The PW1100G has faced durability issues, and if those problems drag on, the financial and reputational fallout could widen. That could mean additional provisions, friction with Pratt & Whitney, and—if airlines lose confidence in the platform—slower future engine demand that offsets any near-term maintenance upside.

Ammonia is also a classic “works in engineering, struggles in economics” trap. The technology may prove viable, but still fail commercially: green ammonia could remain too expensive, scale-up could be harder than expected, or safety and public acceptance could limit deployments—especially near dense population centers where much of the power demand sits.

On defense, the risk is macro and political. Japan has serious fiscal constraints and a very high debt-to-GDP ratio. If bond market pressure or domestic politics forces austerity, even a national security-driven budget could slow, and that would dull one of IHI’s biggest tailwinds.

And finally, there’s the uncomfortable concentration risk at the heart of the aerospace story. IHI’s position has been built through deep, long-running partnerships—especially with GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney. If either OEM chooses to internalize workshare, shift program priorities, or reallocate future content, IHI could find that relationships it assumed were durable were, in fact, conditional.

XIII. Conclusion: 170 Years and Counting

IHI Corporation is back at a familiar place in its history: another turning point.

The company that helped Japan build its first modern ships now makes critical modules for some of the most advanced aircraft engines in the world. The shipyard that emerged from fear of foreign domination now sits inside Japan’s modern defense posture. And the sprawling heavy-industry conglomerate that once seemed content to do everything is trying, at last, to become excellent at a few things that really matter: aerospace, defense, and energy technology.

The transformation isn’t finished. The 2024 data falsification scandal was a blunt reminder that old habits can live for decades inside large organizations. The ammonia vision is still a bet—technically impressive, commercially not yet proven at scale. And the “value unlock” story is new enough that skepticism is rational, especially given how IHI historically treated shareholders.

But the pieces that could make this a genuine re-rating are already visible. IHI has real workshare on many of the world’s most important commercial jet engine programs. It has begun manufacturing high-value engine components for the F-35 supply chain serving operators across the world. It holds the engine role on GCAP, Japan’s most ambitious next-generation fighter effort and a rare collaboration outside the U.S. orbit. And it has put down early markers in ammonia combustion, with demonstrations that moved beyond slides and into operating assets.

“Within IHI, aerospace is a growing business, so the group is shifting human resources and investment to this area,” Sato said.

That, ultimately, is the question: can IHI execute? Can it take 170 years of accumulated engineering capability and pair it with the capital discipline and governance that modern markets demand—especially in a Japan that is, slowly, learning to reward focus, returns, and accountability?

In a way, IHI’s arc mirrors Japan’s. Extraordinary industrial talent, forged under external pressure, now being redirected from twentieth-century heavy industry toward twenty-first century systems—airpower, energy security, and decarbonization. The Black Ships that haunted the founders in 1853 have been replaced by stealth fighters and ammonia turbines.

And in the middle of those megatrends are the picks and shovels IHI knows how to build: engines that keep aircraft in the air, and turbines that—if ammonia truly scales—could help rewire how power is generated. Whether it becomes a great investment comes down to the same three things that always decide these stories: execution, timing, and how long the tailwinds last.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music