Kawasaki Heavy Industries: The 147-Year Journey of Japan's Industrial Architect

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

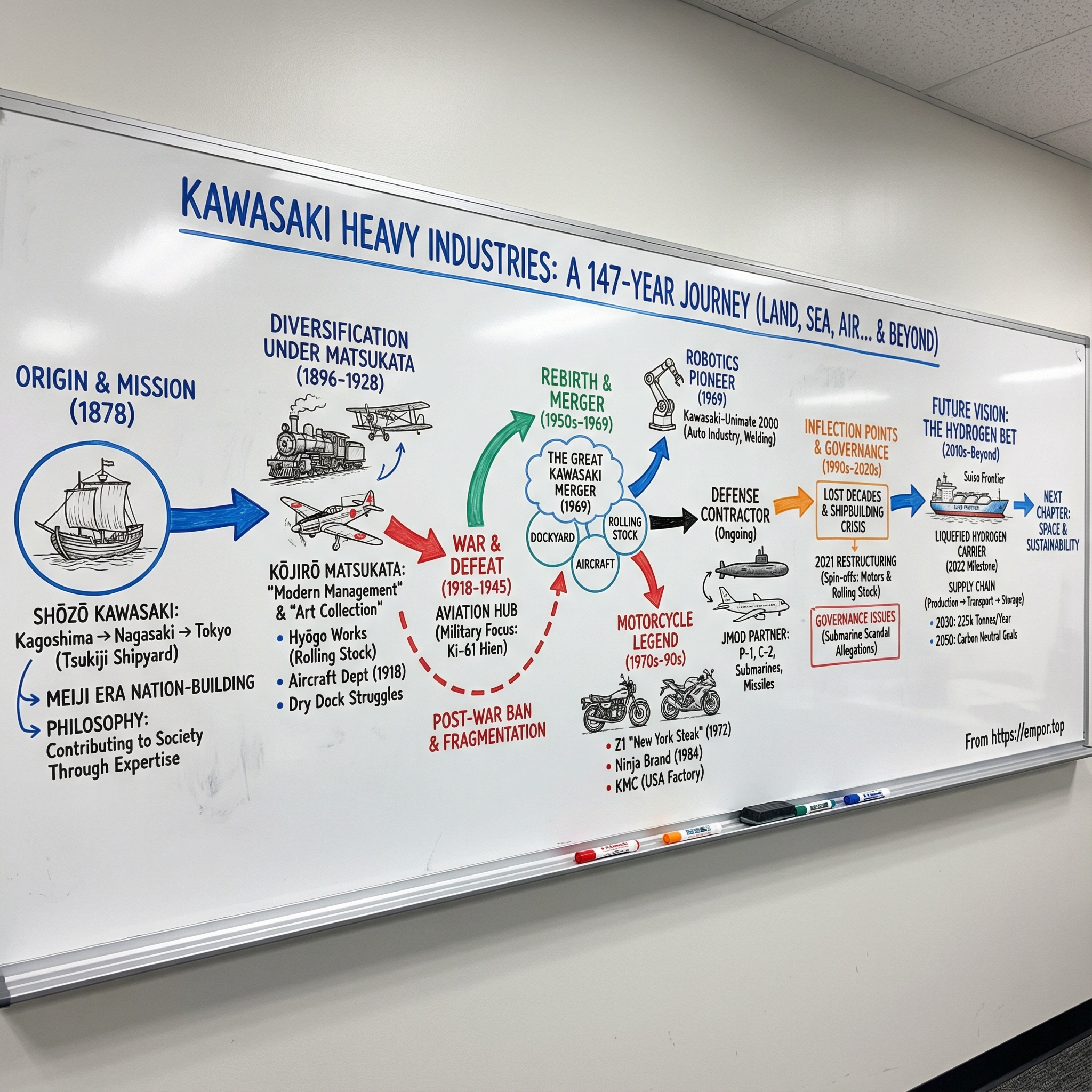

What does a company that builds submarines, Shinkansen bullet trains, Ninja motorcycles, hydrogen carrier ships, and industrial robots all have in common?

At first glance, not much. A submarine slipping beneath the Pacific. A bullet train cutting across the countryside. A motorcycle carving through a canyon. A robot tirelessly welding car bodies on an assembly line. Different worlds, different customers, different physics.

And yet they all carry the same name: Kawasaki.

Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd.—usually just “Kawasaki”—is one of Japan’s iconic industrial builders, active across aerospace, defense, energy systems, industrial equipment, and, most visibly to the rest of the world, motorcycles. On the defense side alone, Kawasaki has manufactured aircraft for the Japanese Ministry of Defense, including the C-1 transport aircraft, the T-4 intermediate jet trainer, and the P-3C antisubmarine warfare patrol airplane. But that’s only one chapter in a much bigger story.

Zoom out, and Kawasaki sits in rare company: one of Japan’s three major heavy industrial manufacturers, alongside Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and IHI—the elite group that helped build modern Japan. The difference is that Kawasaki’s path twists in surprising ways: from nineteenth-century shipyards to twenty-first-century hydrogen carriers, from wartime aircraft production to robots designed for surgery.

So that’s the question we’re chasing: how did a 19th-century shipyard become a conglomerate spanning land, sea, air—and now, space and hydrogen?

The answer comes down to four themes that keep showing up, decade after decade. First, nation-building. Kawasaki was founded in the Meiji era, when industrial capacity wasn’t just business—it was national strategy. Second, diversification as survival. Time and again, the company hit moments that could have ended it, and time and again it escaped by building something new. Third, technological cross-pollination: aircraft-engine know-how informing motorcycles, precision machinery shaping robots, cryogenic handling experience feeding directly into hydrogen transport. And fourth, the hydrogen bet—Kawasaki’s modern moonshot, and the wager that could define its next century.

II. The Founder's Vision: Shozo Kawasaki & Meiji-Era Japan

In 1837, in the castle town of Kagoshima on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, Shōzō Kawasaki was born to a kimono merchant. He didn’t start out as an industrialist. He started out as a hustler.

At 17, he left home and went to Nagasaki—one of the few windows Japan still had to the outside world—and went into trade. By 27, he was in Osaka running a shipping business. Then the sea did what the sea does: a storm sank his cargo ship, and the venture went down with it.

But the shipwreck didn’t just end a business. It rewired his worldview. Kawasaki came away convinced that Japan’s traditional wooden vessels were losing-tech—slower, less stable, less capable—while Western ships were faster, sturdier, and built for the modern world. Out of a very personal failure came an obsession: Japan needed modern shipbuilding.

To understand why that obsession mattered, you have to understand the Japan Kawasaki grew up in. Under the Tokugawa shogunate’s sakoku policy, the country had been largely sealed off from the world. Then, in 1853, Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” arrived and made isolation impossible. And in 1868, the Meiji Restoration flipped the nation’s priorities overnight: industrialize, modernize, and do it at a pace that matched the West—or risk being dominated by it.

That’s the backdrop for Kawasaki’s founding philosophy. He wasn’t trying to build a shipyard for shipyard’s sake. He was trying to build capability. Later, this would be captured in the idea of “Contributing to the nation—to society—through expertise.”

In 1878, Kawasaki took his first decisive step. With the support of Masayoshi Matsukata—an influential figure from the same hometown who was serving as Vice Minister of Finance—Kawasaki borrowed government land along the Sumida River in Tokyo and opened the Kawasaki Tsukiji Shipyard. The government’s involvement wasn’t charity. In Meiji Japan, a domestic shipbuilding industry wasn’t just economically useful; it was strategically urgent.

That early foundation eventually led to something larger. In 1896, Kawasaki founded Kawasaki Dockyard Co., Ltd. in Kobe. Much later, as the company diversified far beyond ships, it adopted the name Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd.—a label big enough to hold what it had become.

And in the crucial decade between 1886 and 1896, under Shōzō Kawasaki’s private management, the dockyard built eighty new ships, including six steel vessels, such as the 570-ton Tamagawamaru. That detail matters because the industry itself was changing under their feet. Shipbuilding was shifting rapidly from iron to steel, and Kawasaki was learning to ride the wave instead of being crushed by it. In a real sense, the company’s story became tangled up with the story of Japan’s modern shipbuilding industry.

Kawasaki’s real foresight wasn’t simply spotting demand. It was recognizing purpose. From the beginning, this was a business designed as an instrument of national development—and that mission would echo through the next century and a half of reinvention.

III. Matsukata's Transformation: From Shipyard to Conglomerate (1896–1928)

When the First Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1894, Kawasaki’s shipyard was suddenly swamped with repair orders. The boom made something obvious: the business had outgrown the limits of a privately run shop. So, after the war ended, Shōzō Kawasaki made the move to take the company public—and with it, he had to solve the succession problem.

He was nearing 60, and he didn’t have a son ready to take over. Instead, he chose someone with the right mix of trust, talent, and proximity to power: Kōjirō Matsukata, the third son of Masayoshi Matsukata—the same hometown ally who had helped Kawasaki get started.

Matsukata was born in 1865 in Satsuma Province, in today’s Kagoshima Prefecture, and he didn’t come up the traditional way. He studied abroad, including at Yale in the United States and the University of Paris in France. That cosmopolitan education gave him something rare in Meiji-era business culture: a genuine global frame of reference.

In 1896, Matsukata became the first president of the newly formed Kawasaki Dockyard Co., Ltd. He would hold the job for 32 years, until 1928—and in that time he turned Kawasaki from “a shipbuilder” into something much closer to what we’d recognize as a modern heavy-industrial group. He pushed into rolling stock, aircraft, and shipping, and he didn’t just modernize machines. He modernized management, too, implementing Japan’s first eight-hour day system alongside other reforms.

His first big test wasn’t a market shift. It was the ground itself.

Shōzō Kawasaki had planned a dry dock at the Kobe shipyard—a non-negotiable piece of infrastructure if the company wanted to build and service bigger ships. But the site sat on the Minato River delta, and the foundations were so weak that construction turned into an engineering nightmare. After multiple failures, the team adopted a new technique: underwater concrete pouring. The dry dock was finally completed in 1902, six years after work began, after time and costs blew far past the original plan.

For Matsukata, it was an early lesson in what Kawasaki could be: a company willing to wrestle impossible problems into submission—if leadership had the patience and nerve to stay the course.

Then came the pivot that defined his era: diversification, not as a side project, but as strategy.

In 1906, Kawasaki opened the Hyōgo Works and began building locomotives, freight and passenger cars, and bridge girders. The same year, it also began producing marine steam turbines at the dockyard. This wasn’t random expansion. It was a disciplined bet on transferable capability. If you can shape steel for ships, you can shape steel for bridges. If you can engineer propulsion at sea, you can apply that thinking elsewhere. Matsukata was turning Kawasaki’s core skill—heavy, precise manufacturing—into a platform.

And he wasn’t done.

During World War I, Matsukata saw something in Europe that many industrialists still dismissed as a novelty: airplanes. In 1918, he established an Aircraft Department at the Hyōgo Works. Aviation was barely out of infancy—only about 15 years removed from the Wright brothers—when Kawasaki started leaning in. In 1922, the company began manufacturing aircraft and built a dedicated aircraft plant. Kawasaki went on to produce Japan’s first metal aircraft, planting the seed for the aerospace and defense capabilities that would later become central to the company’s identity.

Matsukata’s legacy, though, wasn’t only measured in factories and product lines. It also included something almost startling for a heavy-industrial titan: art.

He was an avid collector, building what became known as the Matsukata Collection—said to total around 10,000 works—assembled at his own expense. Parts of it became the foundation for the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, and his ukiyo-e prints are housed at the Tokyo National Museum. He began collecting in London in the middle of World War I, fueled by the fortune Kawasaki earned from wartime shipbuilding, and he spent the years after 1916 roaming galleries across Europe, acquiring everything from paintings and sculpture to furniture and tapestries.

He was even known to be a friend of Claude Monet. One report says that when Monet invited him to choose whatever he wanted from the studio at Giverny, Matsukata bought 18 paintings. It’s a detail that tells you something essential: Matsukata didn’t see industry as an end in itself. He saw it as a way to build a nation—and, in his mind, perhaps a civilization.

By the time he stepped down in 1928, Kawasaki had evolved from a shipyard into a diversified industrial force spanning ships, rolling stock, aircraft, steel production, and shipping. In an era dominated by zaibatsu-style coordination and financing, Matsukata had positioned Kawasaki to operate across the physical infrastructure of modern life—on land, at sea, and increasingly, in the air.

IV. Aviation & War: Rising with the Imperial Military (1918–1945)

Kawasaki Aircraft Industries was among Japan’s earliest serious aviation players. It began in 1918 in Kobe as a subsidiary within the broader Kawasaki industrial group, and as the world slid toward total war, its biggest customer became the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force. Kawasaki wasn’t dabbling in airplanes. It was building aircraft and aircraft engines at scale, for military use.

What set Kawasaki apart wasn’t just production capacity—it was how deliberately it built a design culture. In 1923, Kawasaki brought in Dr. Richard Vogt, a prominent German aerospace engineer and designer, and kept him for a decade. His job wasn’t merely to draw blueprints. It was to teach Japanese engineers how to think like aircraft designers. Among the engineers trained under Vogt was Takeo Doi, who would later become Kawasaki’s chief designer. Vogt himself would go on to become chief designer at Blohm & Voss in Germany.

That ten-year transfer of know-how mattered. It helped create a generation of engineers who could design aircraft from first principles, not just imitate what they saw abroad—and it positioned Kawasaki to deliver when Japan’s military demand surged.

During World War II, Kawasaki Aircraft manufactured the Type 3-1 fighter Hien, the only liquid-cooled fighter developed in Japan during the war. The Ki-61 Hien, nicknamed “Flying Swallow,” became the emblem of Kawasaki’s wartime aerospace capability—and a significant asset for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force.

But war is a brutal kind of growth strategy: it can expand you quickly, and then leave you stranded. Kawasaki’s broader industrial base was already feeling whiplash from earlier shocks—shipbuilding had slumped after the Allied arms-limitation agreement in 1912, and then the Great Depression in 1929 brought deep financial strain. What came next, though, was more than a downturn.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, the occupation authorities deliberately dismantled the country’s aviation industry. Aircraft factories were converted to other uses, development was banned, and the talent that had been so carefully trained was scattered across other fields. That ban wouldn’t be lifted until March 1954.

For years, Kawasaki’s aerospace business was essentially frozen. And for the company as a whole, the question after surrender wasn’t about strategy or market share. It was simpler than that: could it survive at all?

V. Phoenix Rising: The Three-Way Merger & Modern KHI (1945–1969)

In 1947, Japan’s government rolled out a new shipbuilding agenda—and for Kawasaki, it was oxygen. Orders returned, profits followed, and the company clawed its way back to full operations. By the 1950s, Japan had risen to become the world’s largest shipbuilder, and Kawasaki was riding that wave.

The comeback, though, exposed a problem baked in by the occupation years. Kawasaki’s core businesses had been split into separate companies—Kawasaki Dockyard, Kawasaki Rolling Stock Manufacturing, and Kawasaki Aircraft—each running on its own. That structure made sense for the authorities at the time. For Kawasaki, it meant the company’s natural strengths were scattered across different balance sheets, different leadership teams, and different priorities.

Then Japan hit the high-growth 1960s. Across the economy, companies were merging to scale up and sharpen their competitiveness overseas. Inside Kawasaki, Masashi Isano, president of Kawasaki Dockyard, saw an opportunity to do more than keep up with the trend. He wanted to reunite the company’s fragmented pieces into what he called a “great Kawasaki” enterprise.

The idea was simple, and ambitious: become a comprehensive heavy industrial company, building for land, sea, and air—exactly the direction Kōjirō Matsukata had set decades earlier. This wasn’t a reinvention so much as a return to the company’s original logic: diversify, yes—but do it around a shared engineering core.

On April 1, 1969, it happened. Kawasaki Dockyard absorbed Kawasaki Rolling Stock Manufacturing and Kawasaki Aircraft, and the combined company took a name big enough to fit its footprint: Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd.

By any measure, it was a heavyweight from day one—about 26,000 employees, paid-in capital of 28 billion yen, and projected first-year sales of 200 billion yen. But the real value wasn’t the scale. It was the reconnection. Under one roof, aerospace engineers could share methods with shipbuilders, rolling-stock teams could cross-pollinate with other manufacturing groups, and Kawasaki could pursue projects that demanded multiple disciplines at once.

And almost immediately, that unified Kawasaki produced something that would shape its next era just as much as ships or aircraft ever had: Japan’s first industrial robot.

VI. The Robot Pioneer: Japan's First Industrial Robot (1968–1980s)

Kawasaki’s entry into robotics wasn’t a slow drift into a “new adjacent market.” It was a decisive leap—one that started, improbably, with an American roadshow.

In the late 1960s, Joseph Engelberger—later dubbed “the father of robotics”—came to Japan to evangelize Unimation’s industrial robot, the Unimate. Japan was listening. In June 1968, Kawasaki established an Office for Promoting Domestic Production of Industrial Robots. By October, it had signed a technical license agreement with Unimation. And just a year later, in 1969, Japan’s first domestically manufactured industrial robot rolled out: the Kawasaki-Unimate 2000.

What makes that timeline even more striking is that Kawasaki wasn’t supposed to be the partner.

Unimation initially shortlisted seven Japanese candidates—mostly electrical manufacturers. Kawasaki Aircraft, the predecessor organization inside the newly unified Kawasaki group, wasn’t on the list. But Kawasaki’s leadership saw the match immediately: industrial robots weren’t just electronics. They were precision machines. And Kawasaki had spent decades building exactly that—hydraulic precision components for ship steering systems and aircraft controls, the kind of hardware that could be controlled to micrometer-level accuracy.

So Kawasaki went on offense. Once it learned Unimation was looking for a Japanese manufacturing partner, it visited the company in the United States and pushed hard for a deal. Unimation, for its part, was impressed by Kawasaki’s engineering depth and hydraulic expertise. The negotiations worked. Kawasaki engineers trained in the U.S., studied a sample machine back in Japan, and then built the domestic version themselves. The Kawasaki-Unimate 2000 was the result.

The first customer base was narrow. In 1969, robotic automation in Japan was basically synonymous with the auto industry. But that was exactly the point: Japanese carmakers were scaling at breakneck speed in the middle of the country’s postwar growth boom, and one bottleneck kept showing up on factory floors—welding.

Welding was a classic “3K” job: hard, dirty, and dangerous. Automakers had trouble staffing it, especially as production volumes surged. Kawasaki’s pitch was brutally practical. The robot could do the work of ten experienced welders, run around the clock across day and night shifts, and eliminate the need for roughly twenty workers’ worth of labor while improving consistency and safety. Once car manufacturers saw that in action, they began deploying Kawasaki-Unimates ahead of other industries.

None of this came cheap. The Kawasaki-Unimate 2000 sold for about 12 million yen per unit—an enormous price tag in a world where a new university graduate might earn around 30,000 yen a month. But the math still worked: it wasn’t being compared to a machine. It was being compared to staffing two shifts of hazardous work, every day, with reliable output.

From there, the use cases expanded—welding, handling, painting—and the ramp got steeper. By May 1980, Kawasaki had shipped 1,000 Unimate units. The growth curve tells you how quickly the market woke up: it took nine years to sell the first 500, and then only two more years to sell the next 500.

The moment that truly broke the dam came in 1973, when Toyota and Nissan both decided to use Kawasaki-Unimates for auto body spot welding. When Japan’s two flagship automakers bet on robotics, everyone else followed. And Kawasaki—freshly reassembled into a single company—had just locked itself into the supply chain of the industry that would power Japan’s rise for the next two decades.

VII. The Motorcycle Legend: Ninja, Z1, and the American Dream (1970s–1990s)

If robotics was Kawasaki’s bet on the factory of the future, motorcycles were its proof that heavy industry could also build desire.

Kawasaki’s motorcycle business is one of the cleanest examples of the company’s favorite move: take hard-earned know-how from one domain, and redeploy it somewhere totally different. The company began full-scale motorcycle production more than a half century ago, and from the start the DNA was aerospace. Kawasaki’s first motorcycle engines were built on technical knowledge developed for aircraft engines—precision, reliability, power-to-weight thinking—applied to something you could buy, ride, and fall in love with.

The path to greatness, though, didn’t begin with a clean-sheet superbike. It began with a merger. In 1964, Meguro Manufacturing Company merged with Kawasaki Aircraft Co., Ltd., bringing with it experienced engineers and deep motorcycle craftsmanship. The partnership ended up being almost poetically split along the machine’s most important fault line: chassis and engine. The Z1’s chief chassis engineer, Mr. Togashi, came from Meguro. The chief engine engineer, Mr. Inamura, came from Kawasaki Aircraft. Put those together and you get the formula for a legend—Meguro’s chassis technology paired with Kawasaki’s engine technology.

Kawasaki started lighting the fuse in 1969 with the H1, an “epoch-making” model: a 498 cm3, two-stroke, three-cylinder machine that signaled Kawasaki’s intent. At the time, big motorcycles were still largely a European game, and Europe dominated the U.S. market. But Kawasaki could see the wave forming: exports of large-displacement Japanese bikes were about to take off.

Then came the Z1—the motorcycle that turned Kawasaki from a serious manufacturer into a global performance brand.

Introduced in 1972, the Z1 was an air-cooled, four-cylinder, double-overhead-cam, carbureted, chain-drive motorcycle—exactly the kind of engineering statement that said “we can play at the top.” It helped popularize the inline, across-the-frame four-cylinder layout that became synonymous with the era’s Universal Japanese Motorcycle, the UJM.

Inside Kawasaki, the Z1 project had a nickname: “New York steak.” The idea was simple and wonderfully blunt—if you’re looking at a U.S. menu, that’s the best thing on it. That’s what they wanted the Z1 to be: not just competitive, but the best motorcycle in the world.

Kawasaki originally planned to launch sooner, but when Honda got to market first with the CB750 in 1968, Kawasaki chose patience over pride. It delayed the Z1 so it could increase displacement to 903 cc and position the bike in the 1000cc-class. When it finally arrived, Z1 production began as the most powerful Japanese four-cylinder four-stroke then on the market.

And it didn’t just look fast. It proved it.

In 1972, the Z1 set the world FIM and AMA record for 24-hour endurance at Daytona, covering 2,631 miles at an average speed of 109.64 mph. Around the same time, a one-off Z1 ridden by Yvon Duhamel—tuned by Yoshimura—set a one-lap record of 160.288 mph. The message to the U.S. market was unmistakable: Kawasaki wasn’t visiting. It was arriving.

The bike’s reputation wasn’t built only on track stats, either. The Z1 was awarded MCN’s “Machine of the Year” every year from 1973 through 1976—four straight years of critical dominance that locked in Kawasaki’s image as a builder of high-performance engineering, not just transportation.

Kawasaki didn’t stop at exporting to America. It built in America.

In 1974, Kawasaki Motors Corp. established a motorcycle factory in Lincoln, Nebraska—among the first U.S. manufacturing sites for Japanese motorcycle and automobile makers. In January 1975, the plant began producing the KZ series motorcycles, and that same year it also began producing Jet Ski® watercraft. Kawasaki wasn’t just selling machines into the U.S.; it was embedding itself in the country’s industrial landscape and its leisure culture.

Then, in 1984, Kawasaki minted the name that would become synonymous with speed: Ninja.

Launched with the GPZ900R, the Ninja pushed Kawasaki’s performance reputation even further. The GPZ900R became the first production motorcycle to break the 150 mph barrier and appeared in the Tom Cruise film “Top Gun,” searing Kawasaki into American pop culture. By this point, the identity was set: aggressive, technologically advanced, unapologetically fast. In a company that also built ships and trains, Kawasaki had created a consumer brand that people didn’t just respect—they wanted.

VIII. Defense Contractor: Building Japan's Military Hardware

If the Ninja made Kawasaki famous, defense is what kept Kawasaki formidable.

For decades, the company has played a major role in developing and manufacturing aircraft for the Japan Ministry of Defense (JMOD). That includes the T-4 intermediate jet trainer—flown by the Blue Impulse aerobatic team—and the P-3C fixed-wing anti-submarine warfare patrol aircraft. Today, Kawasaki is the prime contractor for two of Japan’s most important modern platforms: the P-1 Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) and the C-2 transport.

The P-1 is the standout. While many maritime patrol aircraft start life as civilian airframes adapted for military work, the P-1 was designed from the ground up for ocean surveillance and anti-submarine missions. It has no civil counterpart. It also earned a rare distinction: it became the first operational aircraft in the world to use a fly-by-optics control system—an approach with advantages in resisting electromagnetic interference compared to traditional fly-by-wire.

Kawasaki’s aerospace footprint isn’t limited to domestic defense programs. On the commercial side, it participates in international joint development and production projects. With Boeing, Kawasaki manufactures components for the 767, 777, and 787, and it also participates in the joint development effort for the 777X. With Embraer, Kawasaki contributes to production for the Embraer 170/175 and 190/195 families.

Then there’s rotorcraft. Kawasaki manufactures a wide lineup of helicopters, from large to compact, including the BK117—Japan’s first domestically developed rotorcraft. For JMOD, it produces the CH-47J/JA transport helicopter and the OH-1 observation helicopter.

Japan has also awarded Kawasaki Heavy Industries a contract to produce 17 CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift helicopters for the armed forces—five aircraft in the CH-47J Japanese variant and 12 in the extended-range CH-47JA variant.

For Kawasaki, defense brings a kind of stability that consumer markets and commercial cycles can’t. Government procurement is steadier, and the requirements are relentless—forcing continuous advances in manufacturing precision, materials, avionics, and systems integration. Kawasaki, which builds submarines, missile engines, military transport aircraft, and helicopters, has forecast defense unit sales rising to 500 billion to 700 billion yen by March 2031.

That long runway is backed by major R&D contracts, too. In June 2023, Japan’s Ministry of Defense signed a five-year research agreement with Kawasaki Heavy Industries valued at 339 billion yen. The project—titled “Study of Prototype Technologies for the New Anti-Ship Missile”—is scheduled to culminate in a final test launch in fiscal year 2027, marking the end of this research phase.

And the relationship runs both ways. Military programs push Kawasaki to master demanding technologies, and those capabilities can spill into commercial work. Meanwhile, commercial production scale can help drive costs down and keep industrial muscle strong for defense programs. That commercial-defense flywheel has been part of Kawasaki’s playbook ever since it first started building aircraft a century ago.

IX. Inflection Point #1: The Lost Decades & Shipbuilding Crisis (1990s–2000s)

Japan’s “Lost Decades”—the long stagnation that followed the 1991 collapse of the asset bubble—hit heavy industry where it hurts most: long-cycle capital projects, global trade, and pricing power.

Kawasaki’s shipbuilding business got an early jolt of optimism in the mid-1990s. In 1995, it reached an agreement with China to produce the largest containerships ever. That deal helped Kawasaki post better-than-expected profits in 1996.

But the lift didn’t last. Soon after, the business slid into a prolonged decline, and Kawasaki had to confront a harsh reality in global shipbuilding: the battlefield had shifted from engineering excellence to cost. Korean and Chinese shipyards could build at significantly lower prices, and in a market that was rapidly commoditizing, Japan’s traditional edge—quality, reliability, technological sophistication—stopped being enough to win orders on its own.

Losses continued into the early 2000s, and Kawasaki went looking for a structural fix. It formed a joint venture with Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries Co., a move meant to steady the business amid the downturn. But by the end of 2001, the agreement was terminated. After that, the pattern became uneven—profits and losses swinging as conditions changed.

The message was clear: shipbuilding alone could no longer carry the company the way it once had. Diversification wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was survival—and the urgency of that pressure set up Kawasaki’s next major moves: the 2021 restructuring that spun off motorcycles and rolling stock, and the hydrogen bet that would come to define its vision for the future.

X. Inflection Point #2: The 2021 Restructuring—Breaking Up to Stay Together

On October 1, 2021, Kawasaki Heavy Industries announced a restructuring that, in plain English, sounded like the opposite of the 1969 merger: it would spin off the Motorcycle & Engine business and the Rolling Stock business into separate companies. At the same time, it would fold the Ship & Offshore Structure business into Energy System & Plant Engineering.

The rationale wasn’t that Kawasaki was abandoning its “one company, many industries” identity. It was that the company had become so broad—and its markets so different—that a single decision-making cadence no longer fit.

KHI builds everything from ocean-going vessels to high-speed trains, and it’s also pushing into fields like hydrogen infrastructure and healthcare robotics. But the motorcycle and engine operation is different from the rest of the portfolio in one crucial way: it’s the only mass-production, consumer-facing business in the group. Consumer products live and die by speed—by timing, brand, and rapid iteration. And Kawasaki openly said the spin-off was meant to speed up decision-making and better align products and services with customer needs.

In other words: the bikes needed to move like a consumer company, not a heavy-industry committee.

So Kawasaki Motors, Ltd. became the dedicated home for that business, with more freedom to act quickly while still carrying the Kawasaki brand. And when it made sense, it could still tap the parent company’s deep engineering bench.

After the restructuring, Kawasaki described its operations across six business segments: Aerospace Systems; Rolling Stock; Energy Solution & Marine; Precision Machinery & Robotics; and Powersports & Engines—covering motorcycles, off-road vehicles, Jet Ski personal watercraft, and general-purpose gasoline engines—alongside the rest of its industrial portfolio.

XI. Inflection Point #3: The Hydrogen Bet—KHI's Moonshot for the 21st Century

Kawasaki’s push into hydrogen started in 2010. And true to form, it wasn’t a single product or a small R&D effort—it was a supply-chain play. The company set out to develop the key technologies needed to make hydrogen work at scale, from production to transportation, storage, and utilization, working alongside partner companies.

Because the problem isn’t “Can you make hydrogen?” The problem is: can you move it.

Hydrogen is the lightest element, which is great for physics and terrible for logistics. As a gas at normal pressure, it’s so low-density that you’d need absurdly large volumes to carry meaningful energy. The workaround is to liquefy it—cool it to about -253°C and shrink the volume dramatically. But then you inherit a new, brutal constraint: keep it that cold, reliably, across an ocean.

In early 2022, Kawasaki hit a milestone the industry had been waiting for. The world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier completed its first international voyage to Victoria, Australia. The ship—Suiso Frontier, “hydrogen” in Japanese—loaded hydrogen into its 1,250 cubic-meter tank, kept it at cryogenic temperature, and returned safely to Kobe by the end of February. The voyage covered more than 9,000 kilometers and served as a pilot project proof point: this could be done.

“You need all the technologies—from liquefiers, loading system, storage tanks, trailers and more—to establish a hydrogen supply chain,” said Motohiko Nishimura, Executive Officer and Deputy General Manager of Kawasaki’s Hydrogen Strategy Division. “But the one thing missing in the world until now was a carrier ship. With the Suiso Frontier, we have demonstrated that liquefied hydrogen can be transported like natural gas for mass use.”

Under the hood, the key is the tank. To keep liquid hydrogen stable during a voyage, Suiso Frontier used a vacuum-insulated, double-wall cargo tank—essentially a cryogenic thermos scaled up to industrial size. And this is where Kawasaki’s history starts to look less like a collection of unrelated businesses and more like a machine designed to compound know-how. The insulation and handling technologies drew on decades of LNG carrier experience, plus more than 30 years dealing with cryogenic liquefied hydrogen as rocket fuel.

That combination is rare. Shipbuilders understand ocean transport. Aerospace teams understand cryogenic hydrogen. Kawasaki had both.

Nishimura described the next step as already underway: moving from a pilot ship to a commercial-scale liquefied hydrogen carrier by the mid-2020s, with the aim of commercial operations in the early 2030s. The planned ship would scale dramatically—up to a 160,000 cubic-meter tank, roughly 128 times larger than Suiso Frontier, capable of holding around 10,000 tonnes of liquefied hydrogen. In a full commercial phase, the plan envisioned importing 225,000 tonnes of liquefied hydrogen to Japan per year through a single supply chain.

Inside Kawasaki, this isn’t framed as a side bet. Group Vision 2030 positions energy and environmental solutions as a focus field, with new businesses like hydrogen and large-scale CO2 capture as a primary growth scenario aligned with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target. Hydrogen, in particular, sits at the center of the company’s growth and transition plan.

The ambition is sweeping. Kawasaki has targeted transporting 225,000 tonnes of liquefied hydrogen to Japan in 2030, and using 45,000 tonnes at a planned hydrogen power plant to supply electricity to its domestic sites. It has also set a goal of expanding hydrogen-related sales—carrier ships, power generation equipment, and licensing fees—to 300 billion yen in 2030, and 2 trillion yen by 2050.

And it’s not just ships. In September 2025, Kawasaki Heavy Industries announced it would begin selling large-class gas engines capable of 30% hydrogen co-firing—described as a world first—another move aimed at turning hydrogen from a strategic vision into usable infrastructure.

None of this is guaranteed. Hydrogen production is still expensive. Demand is still uncertain. And serious competitors around the world are racing toward the same prize. But Kawasaki has been here before: building new infrastructure markets before they’re obvious, scaling complex supply chains, and leaning on a deep bench of hard-won engineering. If hydrogen becomes a pillar of the global energy system, Kawasaki wants to be one of the companies that built the pipeline—literally and figuratively.

XII. Robotics Renaissance: From Factories to Hospitals

In 1969, Japan’s first domestically manufactured industrial robot—the Kawasaki-Unimate 2000—rolled off the line at Kawasaki’s Akashi Works. It was the peak of Japan’s rapid-growth era, when factories couldn’t hire fast enough and automation went from curiosity to necessity. More than half a century later, Kawasaki’s robot business no longer stops at welding lines and paint booths. It’s pushing into places where the stakes are human, not industrial.

In 2013, Kawasaki and Sysmex Corporation formed Medicaroid Corporation as a joint venture to take advanced robotics into healthcare. Development of a new surgical robot system began in 2015. Over the next several years, Medicaroid built five prototype platforms—iterating on both mechanical movement and software control—until the clinical-use system was completed in 2020. They named it hinotori.

Hinotori means “phoenix” in Japanese, a reference to Osamu Tezuka’s famous manga in which the mythical bird’s feathers can heal injuries and disease. The ambition fits the name: hinotori™ was developed as a robot-assisted surgery system designed to reproduce the surgeon’s delicate, precise movements—exactly the kind of “sensitive motion” that separates good outcomes from great ones. It’s also a classic Kawasaki combination: decades of robot technology and mechanical control from heavy industry, paired with Sysmex’s network and expertise in the medical field. Medicaroid has said it will keep developing new functions and services aimed at enabling more patient-friendly, minimally invasive surgery.

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare approved the hinotori system in 2020, and that same year it was used in clinical practice for the first time. The system includes distinctive design choices, including 8-axis robotic arms and a docking-free design—features intended to improve operating-room efficiency and reduce setup time.

Medicaroid also began laying the groundwork for international expansion. In 2015, it established a base for overseas operations in the United States. In 2020, it set up its first European presence with Medicaroid Europe GmbH. Regulatory approvals followed in Asia—Singapore in September 2023 and Malaysia in August 2024—helping drive adoption at leading medical institutions in the region. In November 2024, the first overseas surgery using the hinotori™ system was successfully performed: a robot-assisted radical prostatectomy.

And while surgical robotics is the headline-grabber, Kawasaki hasn’t stopped evolving its industrial lineup, either. duAro is a dual-arm SCARA robot designed to work collaboratively in the same space as people. The Successor system is built around a different idea: capturing the movements of expert engineers through remote collaboration, so skills can be transferred from veterans to newer workers via the robot.

Then there’s Kaleido—a humanoid robot Kawasaki unveiled at the 2017 International Robot Exhibition. It’s still in development, but the direction is clear: robots designed not just for factories, but for human environments—where the use cases could range from disaster response to elderly care to infrastructure maintenance in places that are difficult or dangerous for people to reach.

XIII. Current Challenges & Governance Issues

There’s also a darker, harder-to-tell part of the Kawasaki story: governance. A company can spend a century building credibility in national infrastructure and defense, and still put it at risk in a matter of headlines.

Kawasaki Heavy Industries has been implicated in a scandal, reported by local media, involving allegations that slush funds were used to purchase goods and provide meals for Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) submarine crew members. Kawasaki—one of the companies responsible for constructing and maintaining parts of the JMSDF submarine fleet—was alleged to have generated these funds by manipulating subcontractors and fabricating false transactions.

Reporting has put the scale at roughly 1.7 billion yen over six years, created through bogus subcontractor transactions, with a portion allegedly used for personal items and meals for Maritime Self-Defense Force members. Other reports also describe a smaller pool—about 600 million yen over six years through March—tied to fraudulent practices related to submarine maintenance and repair work.

What makes the allegations especially unsettling is the timeline. Kawasaki is reported to have begun fictitious transactions with subcontractors at least 40 years ago, suggesting the issue wasn’t a one-off failure, but potentially a long-running pattern.

At the same time, Japan’s Ministry of Defense has moved toward imposing a “suspension of designation” on Kawasaki Heavy Industries, which would prevent the company from bidding on projects. That action is tied to separate allegations of falsified fuel-efficiency data for diesel engines used in Maritime Self-Defense Force submarines. The anticipated suspension period has been reported as about two and a half months.

For Kawasaki, this isn’t just bad press. It’s a direct operational threat. Defense contracts are a pillar of the business, and government procurement runs on trust. If these practices truly persisted for decades, the fix won’t be a single apology or a compliance memo—it will require sustained, visible change in the culture and controls inside the defense-related operations.

XIV. Financial Performance & Investment Thesis

By the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, Kawasaki Heavy Industries was showing the upside of being diversified in exactly the right directions. The company reported total revenue of ¥2,129,321 million (about $12.5–13 billion USD), up from ¥1,849,287 million the year before. Management attributed the jump to favorable exchange rates and strong results in Aerospace Systems and Precision Machinery.

Kawasaki also kept an upbeat tone looking forward, forecasting revenue of 2,160,000 million yen and business profit of 130,000 million yen for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025.

The big structural tailwind here is defense. With global defense spending projected to surpass $2 trillion by 2030, Kawasaki’s government-backed work can function like a durable franchise—especially in a world where replacing prime contractors isn’t as simple as switching suppliers. In that context, it’s notable that Kawasaki’s EBIT was reported to have grown from ¥62.06 billion in 2020 to ¥119.95 billion in 2025.

Japanese defense policy is also shifting. Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi planned to raise defense spending to 2% of GDP by the end of March 2026, up from about 1% in March 2023—accelerating the timetable to deter China’s territorial ambitions in East Asia. Her government was expected to begin work on a new defense plan the following year. After Takaichi took office in October, “plans have become clearer and more concrete, and the level of predictability has increased,” Kawasaki President Yasuhiko Hashimoto said during a press briefing.

The Bull Case:

Kawasaki has real moat characteristics through its defense relationships—effectively a government franchise with high barriers to entry. In some areas, it is the only manufacturer of certain Japanese military platforms, creating switching costs that are close to impossible. You can’t just swap out a submarine builder on short notice.

Then there’s hydrogen. If the bet works, Kawasaki ends up positioned near the center of what could become a multi-trillion-dollar global industry. Its early lead in liquefied hydrogen transport technology, combined with decades of LNG carrier experience, is a capabilities stack that would take competitors years to reproduce.

Finally, Kawasaki’s cross-divisional synergies are more than a slogan. This is one of the few conglomerates where technology genuinely moves between units in ways that create advantage: cryogenic rocket-fuel experience informing hydrogen logistics, aerospace engine know-how feeding motorcycle development, precision control expertise strengthening robotics. That kind of “process power” is hard for pure-plays to match.

The Bear Case:

The submarine scandal points to governance weaknesses that may not be contained to one set of contracts. The uncomfortable question for investors is whether internal controls are consistently strong across the organization.

Hydrogen, meanwhile, remains unproven at commercial scale. Demand projections are tied to policy decisions across many governments, and the timing and size of a hydrogen transition are still uncertain. Kawasaki is investing heavily into a future that may take years to pay off—or may not pay off at all if other decarbonization paths win.

And the powersports business has its own transition risk: an aging customer base, plus the challenge of moving toward electric propulsion without losing the performance edge that defines the Kawasaki brand.

Key Performance Indicators to Track:

For long-term investors evaluating Kawasaki, three KPIs matter most:

-

Defense order backlog growth: Defense contracts have long lead times. Backlog is the cleanest window into future revenue and the health of the most stable segment.

-

Hydrogen business revenue milestone achievement: Kawasaki has stated targets of ¥68 billion in 2025, ¥140 billion in 2026, and ¥400 billion by 2030 from hydrogen. The gap between targets and reality will tell you whether the moonshot is becoming a business.

-

Aerospace Systems segment margin: This is the highest-margin segment and the one most exposed to Japan’s defense buildup. Margins here capture both execution and competitive position.

XV. Conclusion: Land, Sea, Air—and Now Hydrogen

The story of Kawasaki Heavy Industries is, in a lot of ways, the story of industrial Japan itself. From Shōzō Kawasaki’s first shipyard in 1878 to Suiso Frontier’s milestone voyage in 2022, the company kept changing shape without losing its center: using engineering to solve problems big enough to matter at the level of a nation.

Kawasaki began on a borrowed stretch of government land along Tokyo’s Sumida River, with a simple philosophy: “contributing to the nation and to society through expertise.” Over the decades, that idea traveled remarkably well. It showed up in shipbuilding as Japan industrialized, in aviation as the world militarized, in rolling stock as the country modernized, in robots as factories chased productivity, and now in hydrogen as the energy system tries to reinvent itself.

That thread is why Kawasaki’s portfolio—submarines, bullet trains, motorcycles, surgical robots, hydrogen infrastructure—doesn’t feel like a random grab bag when you zoom out. It’s patient, strategic diversification built on a shared set of capabilities: heavy manufacturing, precision control, and systems integration.

But the last chapters of this story also make the point that technical excellence isn’t enough. The governance issues around submarine-related work are a reminder that trust is part of the product—especially in defense, where the customer isn’t just buying hardware, but reliability and integrity. If Kawasaki wants to keep building the infrastructure of national security and the next energy era, it has to prove it can operate with the same discipline ethically that it has always shown mechanically.

For investors, that’s the tension. Kawasaki has real strengths: durable defense relationships, genuine engineering depth, and a credible early position in a potential hydrogen supply chain. But it also carries risks that can’t be waved away with a strategy deck. The next decade will show whether hydrogen turns from moonshot to material business, whether the scandal is contained or cultural, and whether Kawasaki can keep earning its place as one of Japan’s industrial architects—on land, at sea, in the air, and now, in the molecules that might power the next century.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music