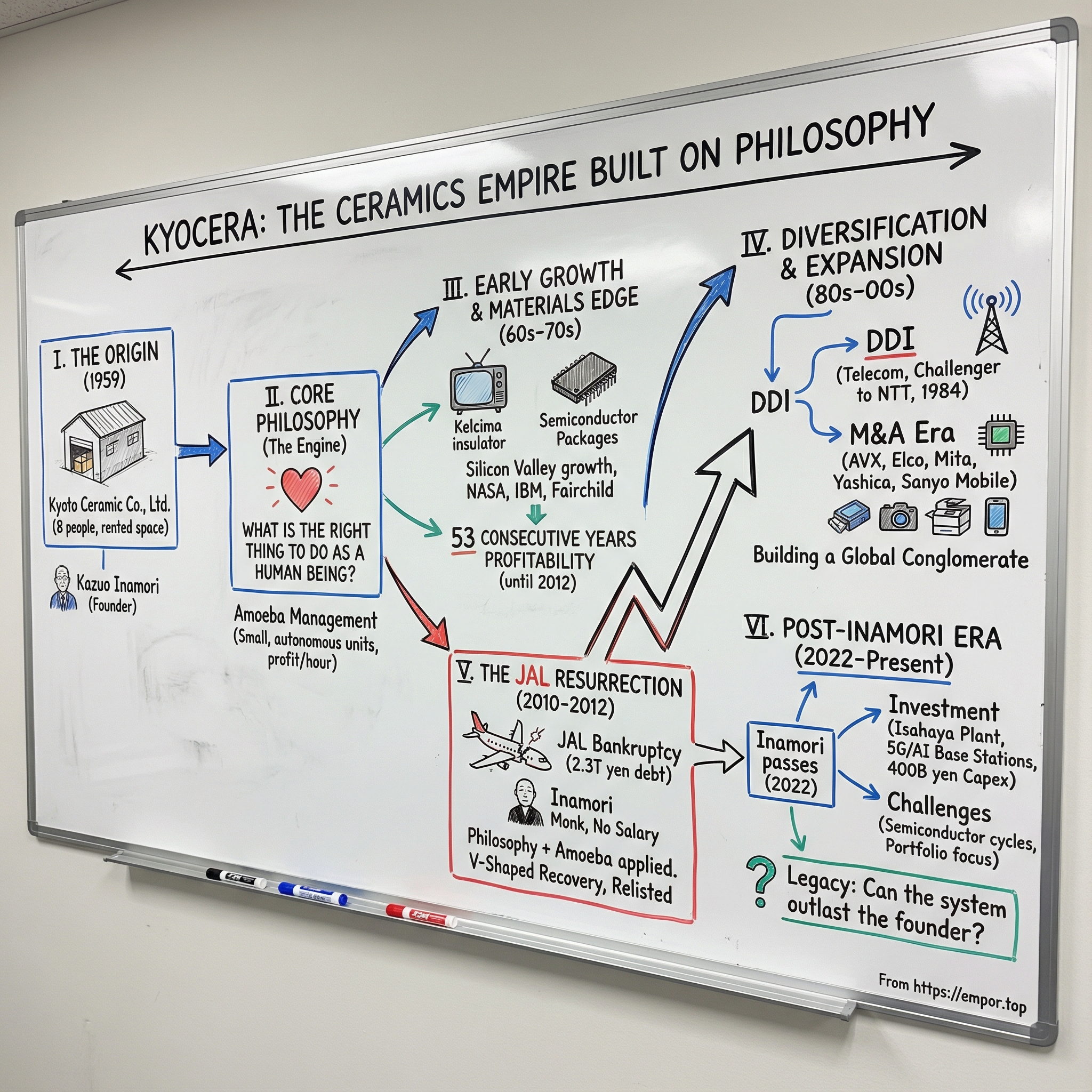

Kyocera Corporation: The Ceramics Empire Built on Philosophy

I. Introduction: The Monk Who Built an Empire

Picture Japan in January 2010. The country’s national airline—an icon of the postwar boom—is collapsing in public. Japan Airlines has filed for protection under the Corporate Rehabilitation Law in what became the largest non-financial bankruptcy in Japanese corporate history. The balance sheet is a crater, with nearly 2.3 trillion yen in debt. The government needs a reset button, fast.

So they turn to someone who, on paper, makes no sense at all: Kazuo Inamori—an ordained Buddhist monk with no airline experience.

Inamori had a reputation for doing things the hard way, the principled way. When he agreed to take the chairman role, he did it without taking a salary, a signal that this wasn’t going to be a typical rescue built on power, perks, and blame-shifting. It was going to be about trust—earned the only way it ever is.

The twist is that the JAL turnaround, as dramatic as it was, was never really an airline story. It was a stress test of an operating philosophy Inamori had been refining for decades—first in a tiny ceramics startup in Kyoto, then across one of Japan’s most consistently profitable companies.

Kyocera posted net income of $1 billion for its fiscal year ending in March 2012. More striking than the figure is what it represented: 53 consecutive years of profitability. Through tech cycles, bubbles, crashes, and Japan’s “lost decades,” Kyocera just kept finding a way to stay in the black.

Today, Kyocera is a sprawling manufacturing and technology conglomerate: industrial ceramics, solar power systems, telecom equipment, office document imaging, electronic components, semiconductor packages, cutting tools, and even medical and dental implant components. It operates through three major segments—Core Components, Electronic Components, and Solutions. Consolidated sales are around 2 trillion yen, and the market values the company at roughly $19 billion.

But the numbers are the outcome, not the explanation. The explanation is the system underneath them—and the man who built that system around a single, disarmingly simple question: what is the right thing to do as a human being?

That question powers three intertwined threads in this story: the materials-science edge that made Kyocera indispensable, the management philosophy that made it resilient, and a founder who became a monk yet never stopped teaching. We’ll follow Kyocera from ceramics startup to global conglomerate, through the creation of KDDI and the resurrection of JAL—and end with the question every founder-led, philosophy-driven company eventually faces: what happens when the philosopher is gone?

II. The Founder: Kazuo Inamori's Origin Story

In 1945, the firebombs fell on Kagoshima. When the smoke lifted, the Inamori family’s small printing shop was gone. Kazuo Inamori was thirteen, and while the war was tearing apart the world outside, he was fighting something more intimate and terrifying: tuberculosis. The disease had already taken two of his uncles. He genuinely believed he might be next.

That brush with mortality landed early, and it landed deep. Confined to bed, he read widely. A book by a Buddhist monk pulled him toward religion. A neighbor lent him writings by Masaharu Taniguchi, a spiritual thinker, and Inamori tore through them. Years later, he would credit those ideas with shifting his attention from the fear of death to the meaning of how you live.

This was not the polished origin story of a future billionaire. Inamori was born on January 30, 1932, in Kagoshima, Kyushu, the second of seven children of Keiichi and Kimi Inamori. His father ran a modest printing operation, and after the war’s destruction the family slipped into poverty. Kazuo did what kids in struggling families do: he worked.

One of his jobs was selling paper bags his father made on the side. He’d load them onto a bicycle and head into town, walking into shops at random and pitching whoever would listen. It didn’t take long for him to notice the obvious problem: randomness is a terrible strategy. So he did what he’d keep doing for the rest of his life—he built a system. There are seven days in a week; he divided Kagoshima City into seven sections and visited the same section on the same day each week.

It was a small thing. But it was the first glimpse of the pattern: observe reality, simplify it, and then make it repeatable.

His path through education wasn’t smooth. Illness disrupted his studies and he failed entrance exams more than once. Still, he made it through, graduating from Kagoshima University in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in applied chemistry. Then he moved to Kyoto and took a job as a researcher at Shofu Industries.

Shofu was hardly a glamorous destination. It was a struggling manufacturer of ceramic insulators—described as being “on the verge of collapse.” But in that lab, at a company most people would have treated as a dead-end, Inamori hit his first major technical breakthrough.

At twenty-four, he became the first researcher in Japan to synthesize forsterite, an engineered ceramic with key applications in high-frequency electronics. Forsterite’s insulating properties made it crucial for components that would ride the consumer electronics wave—especially televisions, which were about to flood Japanese homes. General Electric had already figured out the formula in the U.S. Inamori proved it could be done in Japan, too.

This should have been the start of a long, safe corporate climb. Instead, it sparked a rupture. Despite his results, he became increasingly frustrated with Shofu’s conservative posture—its reluctance to invest, its slow decision-making, its instinct to protect hierarchy over pushing technology forward. The disagreements weren’t minor, and they weren’t fixable. Eventually, he decided to leave.

When his coworkers heard, several chose to go with him.

In 1959, Inamori and seven colleagues founded Kyoto Ceramic Co., Ltd.—the company that would become Kyocera. They did it with 3 million yen in capital and borrowed working funds that came only because Kazuo Nishieda, a managing director at Miyaki Electric Works, put up his home as collateral. The “headquarters” was a rented corner of a warehouse owned by a power switchboard manufacturer. Eight engineers, scarce equipment, and a balance sheet held together by trust.

On April 1, 1959, they held an inauguration ceremony in a small office on the second floor of the factory. Inamori insisted on the word “ceramic” in the company name—it sounded modern, powerful, and specific. There were five executive officers. It was, by any conventional standard, an unlikely beginning.

But Inamori believed the real founding asset wasn’t the cash or the machinery. It was the people. Starting Kyocera with colleagues who had already shared hardship forced him to ask a question that would echo throughout his career: what should we rely on when we don’t have resources? His answer was the human mind—fickle, yes, but capable of something stronger than money: trust and conviction.

That night, at a modest banquet after the ceremony, he stood and laid out his ambition in plain, almost comically incremental steps. First, he said, they would become the best company in Haramachi. Then the best in Nishinokyo. Then the best in Nakagyo Ward. Then Kyoto. Then Japan. And finally, the best in the world.

From the outside, it sounded absurd—eight men in a rented warehouse talking about global leadership. But Inamori had already stared down illness, war, poverty, and the suffocation of a company that wouldn’t back his ideas. Compared to that, aiming for the world wasn’t arrogance. It was just the next system to build.

III. The Early Years: Building a Ceramics Powerhouse (1959-1979)

Kyocera’s first product was humble, but it hit the market at exactly the right moment: a U-shaped ceramic insulator called “kelcima,” used in television picture tubes. Japan was about to fall in love with TV—especially as the 1964 Tokyo Olympics pushed televisions into living rooms across the country—and every one of those sets needed reliable insulation to work.

From the beginning, Kyocera wasn’t just making parts. It was making the kinds of parts that quietly decide whether an electronics boom actually happens.

Early on, the company manufactured high-frequency insulator components for television picture tubes for Matsushita Electronics Industries (later Panasonic). But Kyocera also reached beyond Japan, producing silicon transistor headers for Fairchild Semiconductor and ceramic substrates for IBM in the United States.

That split wasn’t accidental. Inamori quickly saw a problem: Japan’s domestic industrial landscape, shaped by keiretsu ties and long-standing supplier relationships, wasn’t designed to welcome an independent upstart. And he could feel the risk of being overly dependent on one giant customer like Matsushita. He tried to win orders from other established Japanese manufacturers and largely got nowhere—blocked less by product quality than by the structure of the market.

So he went where the door was open. The United States became Kyocera’s pressure-release valve and its growth engine. Fairchild came first, ordering silicon transistor headers. Then IBM followed with large-volume orders for ceramic substrates. For a tiny Kyoto startup, that kind of validation wasn’t just revenue. It was credibility you could build a company on.

And the timing was perfect. This was Silicon Valley’s earliest era: integrated circuits moving from lab curiosity to commercial reality, computers getting smaller and more powerful, and demand exploding for components that could survive heat, stress, and long duty cycles. Kyocera found itself supplying the picks and shovels of the modern electronics age.

In the 1960s, as the NASA space program, Silicon Valley, and computer technology pushed semiconductors forward, Kyocera developed ceramic semiconductor packages—products that would stay at the heart of the company for decades.

It’s worth pausing on why ceramics mattered so much. “Fine ceramics,” as Kyocera calls them, are engineered materials that do what metals and plastics can’t. They hold their shape. They resist corrosion. They tolerate extreme temperatures. They can insulate, or conduct, or manage heat—depending on how they’re formulated and processed. If you’re trying to protect delicate circuitry while moving heat away from it, the material isn’t a detail. It’s the whole game.

Inamori didn’t learn that in a business book. He learned it hands-on, back when he synthesized forsterite at Shofu and saw how the right formulation could unlock entirely new applications. Now he was industrializing that insight—turning materials science into a repeatable advantage.

Kyocera’s push into America soon became physical, not just commercial. In July 1969, it established a U.S. company—Kyocera Corporation’s first subsidiary outside Japan. By 1971, Kyocera International, Inc. had acquired facilities in San Diego and began producing ceramic semiconductor packages, becoming the first Japanese-parented technology enterprise with manufacturing operations in the State of California.

Then came the 1970s, and with them, a new phase: diversification. In the mid-1970s, Kyocera began expanding its material technologies into a wide range of applied ceramic products—solar photovoltaic modules; biocompatible tooth- and joint-replacement systems; industrial cutting tools; and even consumer items like ceramic-bladed kitchen knives, ceramic-tipped ballpoint pens, and lab-grown gemstones.

On the surface, it looks like a company trying everything at once. But the pattern was consistent: Kyocera kept taking one core capability—advanced ceramic materials and precision processing—and redeploying it into markets where those capabilities were scarce and valuable. Different products, same underlying engine.

Still, one move late in the decade marked a shift in kind, not just degree. Inamori wanted to broaden Kyocera beyond ceramic packaging and components, and that ambition helped drive a deal for Cybernet, a Japanese manufacturer of citizens-band radios and audio equipment. In 1979, Kyocera acquired electronic equipment manufacturing and radio communication technologies through an investment in Cybernet Electronics Corporation. This wasn’t just “ceramics, but somewhere else.” It was a step toward finished products and communications—toward becoming something larger than a materials company.

By the end of the 1970s, Kyocera had stretched from eight employees in a rented corner of a warehouse to a multinational business with manufacturing on multiple continents. The technical foundation was in place. The ambition was no longer theoretical.

But the thing that would make Kyocera truly distinctive—the philosophy and the management system that could hold all this growth together—was still being built.

IV. The Kyocera Philosophy & Amoeba Management: A Radical Operating System

What happens when a 27-year-old engineer with no management training suddenly finds himself running a company? Most people would reach for a business textbook. Kazuo Inamori went in the opposite direction—back to first principles.

He became a business owner at twenty-seven with no training or experience in business management. He spent plenty of nights awake, replaying decisions and trying to figure out how to choose correctly. Eventually, he landed on a rule simple enough to use under pressure and strict enough to keep him honest: ask, “What is the right thing to do as a human being?”

That question became the foundation of everything that followed. From the beginning, Inamori tried to anchor Kyocera in the basic moral lessons he’d absorbed as a kid—don’t be greedy, don’t cheat people, don’t lie, be honest.

To Western ears, it can sound almost too clean. Management is supposed to be complex—strategy frameworks, competitive analysis, financial engineering. Inamori’s view was that companies usually don’t break because they lack cleverness. They break because they lose their moral center. Greed invites corner-cutting. Dishonesty destroys trust. Self-interest corrodes teamwork. Get the ethical foundation right, he believed, and the business outcomes get a lot easier.

Over time, he codified these ideas into what became known as the Kyocera Philosophy, built around “pursuing what is right for humankind.”

A tribute in the Financial Times captured what made it unusual: “Long before stakeholder capitalism and the need to serve employees along with investors became vogue in the west, Inamori's management philosophy had centred on his belief that companies should focus on the livelihood and wellbeing of employees instead of simply pursuing profits.”

But philosophy without a mechanism is just a poster on a wall. Inamori needed a way to make those principles show up in the day-to-day—on the factory floor, in sales meetings, in cost decisions. In 1963, just four years after Kyocera’s founding, he built the mechanism.

He called it Amoeba Management.

The concept is straightforward: divide the company into small, autonomous groups—amoebas—and treat each one like a tiny business. Each amoeba has a leader, a defined mission, and responsibility for its own results. The metaphor comes from biology: amoebas can split, merge, and adapt as conditions change. That’s what Inamori wanted Kyocera to do as it grew.

In practice, amoebas are generally groups of 5 to 50 people, though they can range more widely. They can expand, divide, or disband as needed. They’re measured as profit centers, and profit is tracked with a deliberately simple metric: “profit per hour,” calculated as (sales minus cost) divided by working hours. The point wasn’t accounting elegance. The point was visibility—making profitability understandable and actionable for the people actually doing the work.

This was radical for its time. In the early 1960s, management orthodoxy still leaned heavily hierarchical: information flowed up, decisions flowed down. The idea that frontline teams should understand profit, set targets, and run their own unit would have sounded like chaos.

Inamori thought the opposite. Under the Amoeba system, the management philosophy is entrusted to each amoeba leader. Even if that leader has limited experience, they function as the true manager of the unit—creating plans, executing them, and learning the disciplines of management early. Upper management still approves direction, but the operating rhythm is pushed down into the smallest practical teams.

The goal was something Kyocera called “Management by All.” Employees weren’t meant to be passengers in someone else’s plan. They were meant to participate in running the company by taking responsibility for the performance of their own amoeba—aligning their work to shared goals, building a real sense of ownership and achievement.

Of course, there’s an obvious question: if every amoeba is optimizing for its own profit, what stops the company from turning into internal warfare?

This is where Inamori insisted the philosophy wasn’t optional. The amoebas only worked because they were bound together by shared values and constant communication—interactive meetings, coordination across units, and an emphasis on company-wide purpose so no group “wins” by hurting another. Kyocera’s motto, “Respect the divine and love people,” was a signal of how seriously it took the human side of the system. It’s rare to see the word “love” in the literature of a global corporation for a reason.

Importantly, Amoeba Management wasn’t a toolkit like time-motion studies, cost-cutting programs, or statistical process control. It rested on a different premise: that progress comes from people—their imagination, their initiative, and their ability to turn ideals into reality—if you design the organization to let that happen.

And the results were hard to argue with. By the fiscal year ending March 2012, Kyocera reported net income of $1 billion—its 53rd consecutive year of profitability.

Fifty-three straight years in the black. Through oil shocks, bubble collapses, currency swings, and brutal semiconductor cycles that crushed less resilient competitors.

Very few companies can make that claim. Fewer still can trace it back to an operating system designed by a young engineer, learning management in real time, guided by a single question: what is the right thing to do as a human being?

V. The DDI/KDDI Story: Challenging the Giant (1984-2000)

Amoeba Management was built to keep Kyocera coherent as it grew. But in the mid-1980s, Inamori did something that didn’t look like “coherence” at all. He stepped outside the company’s core, straight into the path of a national champion.

In 1984, Japan deregulated its telecommunications industry. Until then, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone, NTT, had effectively owned the entire domestic phone system. Deregulation cracked the door open. Inamori didn’t just walk through it—he tried to kick it off its hinges.

That same year, he founded Daini Denden (DDI). Even the name was a provocation: “Daini Denden” roughly means “Second Telegraph and Telephone.” A second NTT. A challenger, explicitly and unapologetically.

Kyocera entered the telecom business by taking an equity stake in the venture—DDI began as a joint effort between Kyocera, Mitsubishi, Sony, and Secom. It launched in 1984 as the 2nd Telegraph and Telephone Planning Co., Ltd., then in 1985 simplified its name to 2nd Telegraph and Telephone Co., Ltd., with the English name DDI. From day one, it put Kyocera in direct competition with one of the most powerful incumbents on earth.

This was audacious to the point of sounding reckless. NTT wasn’t merely a company with customers; it was the country’s communications infrastructure, shaped by decades of investment and protected by deep political ties. If you wanted to build a competing long-distance network, you didn’t just need capital. You needed a way around the fact that the wires already belonged to someone else.

DDI’s workaround was as unglamorous as it was ingenious. Lacking NTT’s cable network, it built a long-distance system using microwave communications—towers relaying signals across Japan’s mountains, carrying calls through the air instead of through copper. What started as necessity became an advantage: DDI could expand without waiting for permission to touch the incumbent’s infrastructure.

The obvious question is why Inamori bothered. Kyocera’s ceramics business was already succeeding. Semiconductor packaging and components were profitable. Why pick a fight with a monopoly?

Because, to Inamori, this wasn’t only business. It was ethics applied to markets. He believed competition was good for society—that lower phone costs and better service would help Japan’s economy and ordinary households. If challenging NTT improved the country’s communications, then the fight itself was worth it, even if the outcome wasn’t guaranteed.

DDI grew fast. By 1993 it had become the clear number-two telephone company in Japan, and that year it went public. After the IPO, Kyocera retained a 25% stake.

In other words: this wasn’t a side project. It was a serious platform.

Then the industry shifted again. In the 1990s, mobile took off, and Japan’s telecom landscape became crowded and fragmented. That fragmentation created inefficiencies, and consolidation started to feel less like strategy and more like gravity.

In 2000, DDI merged with KDD and IDO to form KDDI. The combined company brought together three different strengths: DDI’s assault on domestic long-distance, KDD’s roots in international communications, and IDO’s position in mobile. The new entity finally had the scale to be a real counterweight to NTT. Over time, it grew into Japan’s second-largest telecommunications services provider—and a giant in its own right.

For Kyocera, the DDI-to-KDDI arc proved something fundamental about what Inamori was building. Kyocera wasn’t going to be “a ceramics company that occasionally diversifies.” It was going to be an Inamori company—willing to commit capital, enter unfamiliar arenas, and take on entrenched power when he believed the outcome served a larger purpose.

And that telecom bet didn’t just reshape an industry. It became a meaningful asset for Kyocera, with gains later boosted by the sale of KDDI shares and the resulting tax adjustments. More importantly, it revealed the pattern that would define Kyocera’s next era: if Inamori could see a way to apply his philosophy and operating discipline to a new field, he wouldn’t hesitate to expand the empire.

VI. The Acquisition Era: Building a Global Empire (1989-2018)

By the late 1980s, Kyocera had proven it could grow organically and it could build new platforms from scratch, like DDI. Now came the next move: buy its way into scale and new capabilities, then try to “Kyocera-ize” what it bought.

The strategy was simple in theory and brutally hard in practice. Kyocera would acquire businesses adjacent to its ceramics and electronics base, then apply the Kyocera Philosophy and Amoeba Management to improve performance. If the operating system really was as powerful as Inamori believed, it shouldn’t matter whether the factory was in Kyoto, California, or a small town in Europe.

Kyocera began building the scaffolding for a truly global company. A 1988 reorganization established head offices in Asia, the United States, and Europe. Then, in 1989, it spent $250 million to acquire Elco Corporation, a U.S. maker of electrical connectors with operations that extended into Europe.

Elco was an early lesson in culture shock. The integration started rough. Many of Elco’s senior managers left after disagreements with Inamori. His hands-on approach and values-driven management style collided with American executives who were used to different incentives, more autonomy, and a less philosophical view of what a company owed its employees.

But Kyocera didn’t retreat. It doubled down—this time with a deal that fit the core much more cleanly.

In 1991, Kyocera acquired AVX Corporation for $560 million. AVX, headquartered in South Carolina with multiple factories in Europe, made multilayer ceramic and tantalum capacitors used across electronics and semiconductors. This was classic Kyocera: not a brand-driven consumer product, but a critical component where materials science and manufacturing discipline mattered.

The combination worked. Kyocera helped drive cost improvements, and together the two companies could offer customers a broader menu of components. Over the first half of the 1990s, AVX’s revenues rose sharply and profits grew severalfold. In August 1995, Kyocera took about a quarter of AVX public in an IPO, generating more than $300 million in profit.

If the Elco deal showed how messy integration can get, AVX showed what Kyocera looked like when the pieces locked: the same underlying capabilities, scaled globally, with a management system that could actually travel.

And then Kyocera kept expanding—sometimes in ways that looked completely unrelated until you traced the thread.

It had already moved into optics by acquiring Yashica in 1983, along with Yashica’s licensing agreement with Carl Zeiss. Kyocera went on to manufacture cameras under the Kyocera, Yashica, and Contax names, leaning on that Zeiss association to compete in a quality-obsessed market.

In another left turn, Kyocera introduced an early portable, battery-powered laptop computer, sold in the U.S. as the Tandy Model 100. It had an LCD screen and could transfer data via telephone modem—primitive by today’s standards, but a real signal that Kyocera was willing to place bets at the edge of what “electronics company” could mean.

The 2000s brought a much bigger push into office equipment and solutions. In January 2000, Kyocera acquired photocopier manufacturer Mita Industrial Company, Limited, creating Kyocera Mita Corporation, headquartered in Osaka with subsidiaries in more than 25 countries. Mita had fallen into bankruptcy in the late 1990s; Kyocera saw a familiar opportunity: buy a struggling operation, then try to rebuild it with discipline and philosophy. In 2012, the business was renamed Kyocera Document Solutions.

Mobile handsets became another major pillar. In February 2000, Kyocera acquired the terminal business of Qualcomm and became a significant supplier of mobile phones. Then, in 2008, it took over Sanyo’s handset business, consolidating Kyocera’s position further.

The buying didn’t stop there. Kyocera also built out its cutting tools business through acquisitions, including SGS Tool Company, which it acquired in March 2016 for $89 million.

By the time this acquisition era matured, Kyocera had become what Inamori had been hinting at since that small banquet in 1959: not a single-business success story, but an empire of related capabilities. Ceramics and semiconductor components sat alongside telecom equipment, document solutions, cutting tools, solar cells, and more.

That diversity brought resilience—downturns in one segment didn’t have to sink the whole ship. But it also created a new problem: complexity. Managing businesses as different as artificial joints and mobile phones is hard for any company.

Kyocera’s bet was that it had something most conglomerates don’t: a unifying operating system. As each acquisition came in, employees were taught the same principles that had guided the company from the start, and teams were reorganized into amoebas that could be measured, improved, and held accountable. The organizational chart could change. The businesses could change. The rules were supposed to stay the same.

And in the next chapter, those rules would face their most extreme test—not in a factory or an electronics market, but in a collapsing national airline.

VII. The Japan Airlines Resurrection: The Monk Who Saved an Airline (2010-2012)

This is the story’s centerpiece—where Inamori’s philosophy stopped being a fascinating corporate oddity and became a life-or-death operating system, tested in public on Japan’s most visible broken company.

The immediate trigger for JAL’s collapse was the global financial crisis of 2008. But the crisis only exposed what had been accumulating for years: deep structural weakness. JAL had built itself around a fleet and a network that didn’t match real demand. It flew a lot of large, inefficient jumbo jets and then fought to fill them—even after heavy discounting. In a market shaped by politics and legacy expectations, supply often exceeded demand. The planes took off anyway.

And JAL wasn’t just any airline. Founded in 1951, it became a symbol of Japan’s postwar rise. It expanded rapidly, then privatized in 1987, carrying all the prestige of a flagship carrier—but also the burdens. After Japan’s 1980s bubble burst, risky investments in overseas resorts and hotels dragged on earnings. Pension and payroll costs swelled. And JAL maintained unprofitable domestic routes that politics made difficult to cut.

By January 2010, the end arrived: protection under the Corporate Rehabilitation Law, nearly 2.3 trillion yen in debt, the largest business failure in Japan outside the financial sector. JAL had already been rescued repeatedly—four government bailouts since 2001—and none of them fixed the underlying machine.

So the government made a choice that sounded, frankly, absurd. It asked Kazuo Inamori to lead the turnaround.

Inamori was 77. He’d been ordained a Buddhist monk for thirteen years. He had no airline experience. He’d publicly criticized JAL’s lack of cost discipline, once saying its executives were too inept to run a vegetable shop. And now, at the moment of maximum humiliation, Japan was handing him the keys.

Inamori agreed under one condition: he would take no salary. He framed the job as service—an obligation to the employees and to society, not a career move and certainly not a payday.

And when he walked into JAL, he didn’t bring an airline playbook. He brought the only two things he truly believed in: the Kyocera Philosophy and Amoeba Management.

First came the values. Inamori created a plain-language JAL Philosophy modeled on Kyocera’s, so everyone—pilots, mechanics, cabin crew, back office—shared the same “why” and the same behavioral expectations. The point wasn’t slogans. It was to reset the center of gravity away from entitlement and toward responsibility, honesty, and customer focus.

Then came the mechanism. JAL had historically looked at income and costs at the network level, which made it easy to hide the truth. A route could be bleeding cash, and nobody on the ground would feel it, because the losses disappeared into the aggregate.

Inamori refused to run the airline that way. He insisted on understanding profitability route by route, flight by flight. He pushed seminars and training—especially for senior staff—to build real management intuition and cost awareness, not just operational competence.

He also adapted Amoeba Management to aviation. He reorganized the company into small units, each responsible for improving its own results. The goal wasn’t internal competition for its own sake. It was to give people line-of-sight between their decisions and the airline’s survival: maximize revenue where you can, cut waste where you must, and treat profitability as a daily discipline rather than an annual surprise.

Inamori later explained that stable airline operations require exactly this kind of management accounting system. He reworked the amoeba model so it could function inside an airline, with the result that profitability information for JAL’s routes and flights became available the very next day—far more granular, and far faster, than what many airlines were used to.

The change was cultural as much as operational. People inside JAL described a pre-bankruptcy organization with weak cost awareness and diluted responsibility. Under Inamori, that shifted dramatically. He was famously impatient with hierarchy and blind obedience to rules. Instead, he pushed authority and accountability downward and told employees to think like leaders on the frontline. The carrier, he believed, had neglected customers. Fixing the numbers without fixing that mindset would only recreate the same disaster later.

Then came the part that made the world pay attention: it worked.

JAL’s results improved with startling speed. After years of deficits, it became the world’s most profitable airline, posting an operating profit of 188.4 billion yen in the fiscal year after the restructuring. In September 2012—just two years and eight months after bankruptcy—JAL relisted on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

The turnaround became a proof point that even skeptics couldn’t dismiss. Inamori’s philosophy wasn’t merely a Kyocera cultural artifact. Paired with a rigorous, transparent accounting system and relentless frontline accountability, it was portable—capable of reviving a huge, complex organization in one of the most unforgiving industries on earth.

Even the productivity story echoed that. Research has found that while JAL’s total factor productivity fell sharply with bankruptcy, it recovered rapidly afterward and rose to exceed ANA’s, with evidence suggesting the interventions had a positive impact on productivity growth.

If Amoeba Management could survive jet fuel, unions, thin margins, and public scrutiny—where couldn’t it survive?

VIII. The Spiritual Journey: Becoming a Buddhist Monk

In 1997, at age 65, Kazuo Inamori did something that baffled the Japanese business establishment: he stepped away from active management and became a Zen Buddhist monk.

He was ordained at Enpukuji Temple in Kyoto, taking the monastic name Daiwa. But this wasn’t a rebrand or a corporate flourish. Inamori didn’t use religion as decoration. He treated it as practice. In September 1997, he became a lay priest at Enpukuji—formalizing a spiritual direction he’d been moving toward for years.

To outsiders, it looked like a sharp turn. To anyone who had listened to him, it felt inevitable. The same thread ran through everything: “Do what is right as a human being.” The insistence that a company exists for more than profit. The belief that work is, at its core, a training ground for character.

Inamori’s thinking can be understood in two layers. The first is a values system—a deep conviction shaped by early brushes with mortality, and influenced by traditions like Zen Buddhism and a samurai-like stoicism that treated material success as secondary to purpose. The second is what he built on top of those values: rules, routines, and management tools designed to make that inner conviction visible in daily decisions. Inamori wasn’t content to believe the right thing. He wanted an organization that could do it.

This bigger mission showed up clearly in philanthropy. In 1984, he established the Inamori Foundation, and with it the Kyoto Prize—an international award recognizing “extraordinary contributions” to science and civilization, and to the enrichment of the human spirit. One of its signature projects, first presented a year later, was designed to honor fields he felt the Nobel Prizes didn’t fully cover: advanced technology, basic sciences, and arts and philosophy.

He also became, in effect, a public teacher. Inamori published more than 60 books in Japanese, selling more than 19 million copies across 21 languages. He was no longer just a founder with a quirky management system. He was a philosopher-author with a following.

And he didn’t keep the lessons inside Kyocera. Beginning in 1983 and continuing until 2019, he served as principal of Seiwajyuku, a private management school that grew to 104 locations, including 48 outside Japan. Through it, he taught his philosophy to over 14,000 business owners and entrepreneurs—people whose companies had no formal tie to Kyocera, but who came looking for the same thing: a way to run a business without sacrificing the soul.

It’s important to get the direction of influence right. The spiritual practice didn’t emerge because Kyocera succeeded. Inamori didn’t “discover” Buddhism after building an empire. The impulse to ask what’s right—and to treat that as the center of management—was there early. Formal ordination was simply the moment his private trajectory became public.

And then, in one of history’s great plot twists, the government asked him to come back.

In January 2010, at age 77, Inamori was pulled out of retirement to help save Japan Airlines. He became president as JAL entered bankruptcy protection on January 19, 2010, and led the restructuring that ultimately allowed the airline to relist on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2012.

Even after that, he kept teaching and writing. Kazuo Inamori (January 30, 1932 – August 24, 2022) was a Japanese philanthropist, entrepreneur, Zen Buddhist priest, and the founder of Kyocera and KDDI. He died at his home in Kyoto on August 24, 2022, at age 90—leaving behind a rare legacy: builder of major companies, architect of an operating philosophy, and a teacher whose influence extended far beyond his own corporate walls.

IX. Recent Inflection Points: 2010s to Present

On August 24, 2022, Kazuo Inamori died peacefully at his home in Kyoto. He was 90. His passing closed a chapter in Japanese business history—and opened the inevitable question for any company built around a founder’s worldview: what happens when the philosopher is gone?

Kyocera’s answer, at least so far, has been continuity. The Amoeba Management System remains in place. The Kyocera Philosophy Handbook is still distributed to employees. And that deceptively simple standard—“do what is right as a human being”—still serves as the company’s internal compass.

But surviving as a set of rituals is different from surviving as a living operating system. The real test isn’t whether the handbook exists. It’s whether the instincts it trained into people still show up when the trade-offs get hard.

And the trade-offs have gotten hard.

Kyocera has been navigating an uneven recovery. Orders improved in key automotive components, but semiconductor and information-and-communication markets stayed sluggish as customers worked through inventory adjustments. The result: momentum, but not a clean rebound.

Still, Kyocera has continued to invest through the cycle—particularly in the areas where its original advantage, fine ceramics, is becoming more valuable again.

In April 2023, Kyocera reached an agreement to acquire about 37 acres of land for a new smart factory at the Minami Isahaya Industrial Park in Isahaya City, Nagasaki Prefecture. President Hideo Tanimoto attended the signing ceremony at the New Nagasaki Hotel. Kyocera decided on the plant in December 2022, after concluding that rising demand would require more production capacity—even as it continued reinvesting in existing factories in Japan and overseas.

The planned investment is about 62 billion yen, a clear signal that Kyocera intends to build, not just wait.

The thesis behind the factory is straightforward: the world is asking more of electronics every year. Devices keep shrinking. Semiconductor technology keeps advancing. Smartphones and communications gear keep getting more capable. 5G base stations and data centers keep multiplying. Cars are turning into rolling computers, with ADAS and EV systems pushing demand for more robust components. To serve that pull, Kyocera is designing the new facility to manufacture fine ceramic components used in semiconductor-related applications, along with semiconductor packages, targeting the start of production in 2026.

By August 28, 2024, the plan moved from paperwork to dirt. Kyocera held a groundbreaking ceremony to begin construction at Minami Isahaya, following the land purchase agreement it had concluded in April 2023. The aim was the same: strengthen manufacturing capacity to meet rising demand.

At the same time, Kyocera has been trying to shape the next layer of communications infrastructure—again taking aim at the “societal plumbing” of technology, just as Inamori did with DDI decades earlier.

The company has begun full-scale development of an AI-powered 5G virtualized base station, with the stated goal of commercialization. Kyocera plans to use its telecommunications and virtualization technologies to run base station functionality on general-purpose servers using the NVIDIA GH200 Grace Hopper Superchip. The pitch is that AI can improve performance, reduce power consumption, and simplify operations and maintenance.

Kyocera also says its approach could allow multiple telecom operators to share a single base station—reducing how many sites need to be deployed, lowering capital spending and electricity costs, and making it easier to expand 5G coverage.

All of this sits inside an aggressive growth plan. Kyocera has targeted 2 trillion yen in sales for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2023, and set a longer-range goal of 3 trillion yen in sales by the fiscal year ending March 31, 2029.

To support that, it has outlined record capital expenditures of 400 billion yen over the three years from fiscal 2024 to fiscal 2026, including new buildings for expected long-term demand and a “scrap and build” approach to expand capacity at existing facilities.

But there’s another side to the story: focus. Alongside investment, management has signaled it’s willing to shrink the company where it sees limited upside. Kyocera has said it will consider selling operations totaling about 200 billion yen in sales that it views as having constrained growth potential. President Hideo Tanimoto told Nikkei the company was positioning such businesses as non-core and would like to sell them within the fiscal year ending March 2026, as it streamlines amid sluggish demand in areas including automotive electronic parts.

This is what the post-Inamori era looks like in practice: keep the philosophy, keep building where the long-term pull is real, and get more ruthless about what doesn’t belong. The open question is whether Kyocera can do all of that while preserving the thing that made it Kyocera in the first place—an operating system designed not just to make money, but to make decisions it can live with.

X. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate-High)

Kyocera fights on very different battlefields at the same time. In specialty ceramics—especially semiconductor packages and the fine ceramic components that go into chipmaking equipment—it competes from a position of real strength. This is where decades of materials science turn into a moat: deep process know-how, consistent quality at scale, and the ability to manufacture demanding products like large, multi-layered organic packages and high-performance ceramic packages with tight temperature uniformity and precision processing.

That advantage matters because semiconductors are one of Kyocera’s biggest end markets, and demand for new, higher-performance components is expected to grow over the medium to long term as chips keep getting more advanced.

But in businesses like document solutions and mobile handsets, the story is different. These are mature, crowded markets where price pressure is constant and differentiation is harder. Kyocera tends to win there less through consumer-style brand pull, and more through operational reliability and vertical integration—being able to build critical parts in-house and deliver products that are tough, consistent, and cost-competitive.

Threat of New Entrants (Low in core ceramics, Moderate elsewhere)

In Kyocera’s core, the barriers are punishing. Advanced ceramics are not a field where a well-funded newcomer can show up and “catch up” quickly. Starting with Inamori’s early work on forsterite, Kyocera expanded into a vast range of ceramic materials—roughly 200 formulations—spanning alumina, silicon nitride, silicon carbide, sapphire, zirconia, cordierite, aluminum nitride, mullite, steatite, cermet, and more. That body of knowledge is the product of decades of experimentation, failure, refinement, and industrial learning.

Semiconductors add another layer of protection: qualification. Customers won’t risk their yields, uptime, or reputations on unproven components. New suppliers often face years of evaluation and testing before they earn meaningful production volume.

Outside that core—particularly in more consumer-facing or commoditized segments—the barriers are lower, and the threat of new entrants rises accordingly.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low)

Kyocera has long insulated itself here by making a big chunk of what it needs. It produces its own ceramic powders, controls key processes like sintering, and manages downstream assembly. That vertical integration reduces dependence on suppliers, limits pricing pressure from upstream vendors, and gives Kyocera tighter control over cost and quality.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate)

On paper, Kyocera’s major customers—semiconductor leaders and automotive OEMs—are concentrated and powerful. They negotiate hard, and they can be relentless about cost.

In practice, the power balance is softened by risk. For precision components, switching is expensive and dangerous: a failure can mean defective chips, manufacturing downtime, or recalled vehicles. Add in long qualification cycles, and “just switching suppliers” becomes a slow, high-friction decision. That stickiness gives incumbents like Kyocera meaningful protection.

Threat of Substitutes (Low in ceramics, Higher in consumer segments)

Where Kyocera’s ceramics operate at the extremes—high heat, high wear, high frequency, harsh chemical environments—there’s often no true substitute. Metals and plastics can’t consistently match engineered ceramics in those demanding applications.

Other segments are less protected. Document solutions face ongoing digital substitution as paper usage declines, and mobile handsets are intensely substitutable, with competition dominated by larger global brands.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies (Strong)

Kyocera’s scale shows up in manufacturing cost and consistency—advantages smaller competitors struggle to match. The planned Isahaya smart factory is a continuation of that play: build capacity and process sophistication ahead of demand. With major capital spending planned over the next few years, Kyocera is effectively saying that scale will be decisive in the next cycle, not optional.

Network Effects (Limited)

Kyocera isn’t a platform business. Its components don’t become more valuable simply because more people use them. Customer relationships matter, but they don’t compound in the classic network-effects way.

Counter-Positioning (Moderate)

Kyocera’s management model is its own kind of counter-position. Amoeba Management and the Kyocera Philosophy aren’t tactics competitors can simply copy-paste. Adopting them would require deep organizational change—accounting systems, incentives, leadership development, daily operating rhythms—and most companies won’t pay that cultural price unless they’re in crisis. That reluctance leaves Kyocera with an advantage that’s less visible than technology, but hard to replicate.

Switching Costs (Strong in precision components)

Kyocera has supplied ceramic packages since the 1960s, and those packages end up embedded in a wide range of semiconductor and electronic devices: image sensors, accelerometers, gyroscopes, microprocessors, LEDs, fiber-optic communication modules, radio-frequency power transistors, MMICs, crystal devices, and SAW devices.

Once a package is designed into a device, changing suppliers can mean redesign work and extensive re-qualification. That process is costly and slow—exactly the kind of friction that makes established suppliers hard to dislodge.

Branding (Limited)

Kyocera’s brand carries weight in B2B—engineers and procurement teams know what it stands for—but it doesn’t command a broad consumer premium outside Japan. In many of its most important markets, Kyocera wins on performance and reliability more than on name recognition.

Cornered Resource (Strong in materials expertise)

Kyocera’s most defensible resource is the accumulated know-how it has built over more than six decades: ceramic formulations, processing techniques, and application engineering that keep evolving alongside the semiconductor industry. This isn’t a single patent or a secret recipe—it’s a compounding body of learning that competitors can’t quickly buy or imitate.

Process Power (Strong)

Finally, there’s the thing that ties the whole story together. Amoeba Management, practiced consistently for decades, creates a kind of institutional muscle: fast response to market shifts, continuous cost improvement, and a system that develops leaders throughout the organization. It’s not flashy. It’s not easily visible from the outside. But it’s one reason Kyocera has been able to operate across cycles—and across wildly different businesses—without flying apart.

XI. Investment Considerations: Key KPIs and Risk Factors

For long-term fundamental investors, two metrics are especially telling if you’re trying to separate short-term noise from whether Kyocera’s underlying machine is still working.

1. Core Components Segment Profit Margin

This is the heartbeat of Kyocera’s identity: fine ceramics and the precision components that sit underneath semiconductors and other high-reliability industries. Demand from chips, EVs, and 5G can lift revenue over time, but margins tell you something more important—whether Kyocera is keeping its pricing power and manufacturing edge, or merely shipping more volume at lower quality of earnings.

And right now, the margin line matters because this segment has been pressured by inventory adjustments. Watching how quickly and how cleanly profitability rebounds is a real-time test of Kyocera’s operational discipline.

2. Consolidated Free Cash Flow Yield

Kyocera is in an investment-heavy phase, including its plan for 400 billion yen of capital expenditures over three years. In that context, free cash flow relative to the company’s market value is the reality check. Are these investments translating into durable cash generation, or just bigger factories and bigger depreciation?

Kyocera’s history—more than five decades of consecutive profitability—argues for serious capital discipline. Free cash flow is where that claim either continues under new leadership or quietly breaks.

Bull Case

If the semiconductor cycle turns into sustained secular growth, Kyocera’s core strengths get pulled forward. Forecasts cited for key component categories point to steady expansion: connectors at about 4% CAGR, MLCCs around 10%, timing devices roughly 5%, and polymer tantalum capacitors about 7%. If growth like that plays out, the new capacity Kyocera is building should land into a rising demand curve, and returns on that investment could look very good.

There’s also a management argument for the bull case. The JAL turnaround was the ultimate demonstration that Inamori’s operating system can travel. If Kyocera’s current leadership can preserve the philosophy while staying adaptive, the company’s advantage may be less about any single product and more about how it runs itself.

Finally, the AI-powered 5G virtualized base station initiative offers a plausible next act. If it works, it would build on Kyocera’s telecom lineage and engineering depth—and give the company a new growth lane tied to critical infrastructure.

Bear Case

The near-term risk is simple: the semiconductor and information-and-communication markets could stay soft longer than expected as inventory adjustments drag on. Kyocera’s own outlook has suggested those adjustments were expected to continue into fiscal 2025, with recovery anticipated in the latter half. If that recovery slips, earnings power can look weaker for longer—even if the long-term thesis remains intact.

There’s also a harder-to-model risk: culture. Inamori didn’t just design the system; he embodied it. Kyocera has institutionalized the philosophy, but a philosophy without its founder can fade from a lived standard into a historical artifact. If that happens, the company’s most unusual “moat” weakens.

And then there’s portfolio drag. Document solutions face a long, structural headwind as the world uses less paper. Mobile handsets are a brutal arena dominated by larger players. If these businesses underperform, they can weigh on consolidated results—especially given how much of Kyocera sits inside the broad Solutions segment.

Material Risks

Geopolitical exposure: Meaningful operations and sales in China leave Kyocera exposed to trade tensions and supply-chain disruption.

Currency volatility: As a Japanese exporter, swings in the yen can materially affect reported earnings.

Technology transitions: Semiconductor packaging is evolving fast—chiplets and advanced substrates could reshape where value sits. If Kyocera fails to stay at the front edge, today’s product advantages can erode.

Post-founder leadership: Over time, leadership will inevitably shift to executives who never worked directly with Inamori. Whether the philosophy remains an active operating discipline through that transition is one of the biggest long-term uncertainties.

XII. Conclusion: A Philosophy Tested by Time

So what do you take away from Kyocera’s 65-year run—from eight engineers in a rented corner of a warehouse to a global manufacturer that kept making money through cycles that wiped out supposedly stronger competitors?

First: philosophy, in this story, isn’t decoration. The Kyocera Philosophy and Amoeba Management weren’t posters in a hallway. They were an operating system—one that turned “do what is right as a human being” into daily decisions about cost, responsibility, and teamwork. Fifty-plus consecutive years of profitability doesn’t happen by accident, and it doesn’t happen on charisma alone.

Second: materials science compounds. Kyocera didn’t “find” advanced ceramics; it built them, refined them, and kept expanding the playbook—formulation by formulation, process by process, application by application. That kind of advantage isn’t something a newcomer can buy quickly with capital or a few key hires. It’s accumulated learning, and it’s slow to copy.

Third: diversification is both a shield and a burden. Kyocera’s spread—components, devices, document solutions, cutting tools, telecom—helps it absorb shocks when any one market turns down. But breadth also creates complexity. Without a way to coordinate, measure, and develop leaders across wildly different businesses, a conglomerate becomes a collection of unrelated problems. Kyocera’s bet has always been that Amoeba Management is what keeps the whole thing from flying apart.

And finally: succession is the real exam for any founder-built, philosophy-driven company. Inamori designed Kyocera to outlast him. Now the question is whether the philosophy remains a living discipline—or gradually turns into a historical artifact that’s repeated, but not practiced. That answer will matter not just to Kyocera’s shareholders, but to anyone who believes culture can be engineered to endure.

Kazuo Inamori’s ceramics empire stands as one of postwar Japan’s most unusual business achievements: proof that a company can pursue ethical purpose without forfeiting commercial success—and that, in the long run, a moral center might be a competitive advantage.

The next chapter will tell us whether that advantage was Inamori himself, or the system he left behind.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music