Yokogawa Electric: The Quiet Giant of Industrial Automation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the control room of a modern oil refinery at three in the morning. The place is dim and quiet, lit by rows of screens. Each one is streaming a live pulse of the plant: temperatures, pressures, flow rates, chemical balances—thousands of variables that have to stay in range, all the time. The operators aren’t frantic. They’re calm. They trust what they’re seeing, because they have to. In a refinery, a single bad reading or a slow response isn’t an inconvenience. It can be the start of something catastrophic.

And sitting underneath that calm, orchestrating all of it, is a piece of infrastructure most people never think about: a distributed control system. In countless plants around the world, that system comes from a Japanese company most investors couldn’t pick out of a lineup—Yokogawa Electric Corporation.

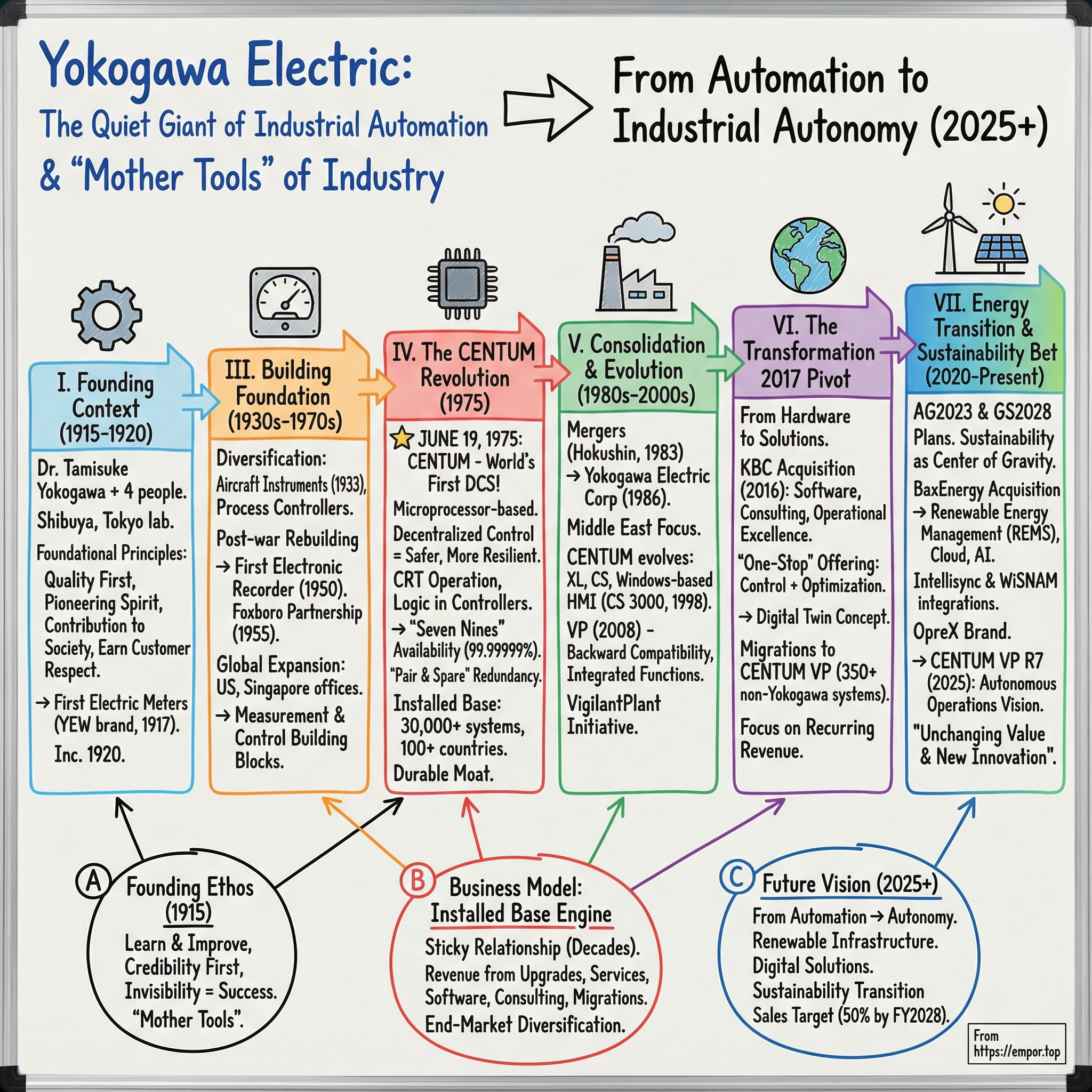

That’s the question at the heart of this story: how did a tiny electric meter research institute founded in 1915—four people, in Shibuya, Tokyo—end up creating the world’s first distributed control system? The kind of technology that quietly runs refineries, chemical plants, and power stations—the physical backbone of modern life.

In 1975, Yokogawa launched CENTUM. Since then, CENTUM has kept evolving as a core monitoring and control system designed around an obsession with reliability, stability, and compatibility—while helping plants push productivity higher. Over the decades, more than 30,000 systems have been deployed across more than 100 countries, serving everything from oil refining and petrochemicals to pharmaceuticals, food, water, electric power, and gas.

Yokogawa is Japanese engineering excellence taken all the way to its endpoint: make it work, make it last, and make it safe. The company claims that since CENTUM’s release, it has achieved real-world availability of 99.99999%—“seven nines.” In plain English, that’s the difference between a plant that occasionally hiccups and a plant that essentially never stops because of its control system. In a market where rivals have been acquired, merged, or simply faded away along with their platforms, Yokogawa is still here. And in 2025, as CENTUM turns 50, Yokogawa is staring down its next shift: from industrial automation toward industrial autonomy.

We’re going to follow this story through a few big arcs. First: the founding ethos—an early philosophy of learning, craftsmanship, and earning customer respect that still shapes how Yokogawa builds. Second: the breakthrough that mattered—a new way of controlling industrial plants that made them safer and more resilient. Third: the strategic evolution—how a company rooted in instruments and hardware pushed up the stack into software, consulting, and services. And finally: the energy transition bet—how Yokogawa is positioning itself not only to serve the industries that built its installed base, but also the renewable infrastructure now being built at global scale.

By the numbers, Yokogawa is substantial but not gigantic. As of March 31, 2025, it had trailing twelve-month revenue of about $3.69 billion, a market cap around $6.9 billion, and roughly 19,947 employees. But those stats miss what’s actually interesting here. Yokogawa isn’t defined by size. It’s defined by endurance, technical depth, and the fact that what it builds sits inside systems where failure is unacceptable.

Inside Yokogawa, there’s a phrase that captures the company better than any slogan: “mother tools of industry.” These instruments and control systems are the tools that make all other industrial work possible. When they fail, people can get hurt. When they work—as they almost always do—nobody notices.

That invisibility is Yokogawa’s greatest achievement. It’s also what makes the company such an unusual story to tell.

II. Founding Context: Japan's Industrial Awakening (1915-1920)

It’s 1915, and Japan is in the middle of a national reinvention. The Meiji Restoration has turned the country outward and forward: new factories, new rail, new universities, and a furious race to adopt Western production methods and technology. Electricity is spreading fast. Long-distance transmission is becoming viable. Bigger thermal and hydro plants are coming online. Costs drop. Usage climbs. Power is no longer a novelty—it’s becoming essential to daily life and to industry.

But Japan has a quiet, dangerous dependency sitting at the center of that story: measurement. If you can’t reliably measure voltage, current, and power, you can’t bill correctly, you can’t operate safely, and you can’t scale an electrical grid with confidence. And at the time, Japan didn’t really have a domestic measurement industry. The critical instruments were coming from abroad—names like General Electric, Siemens, and Westinghouse. That wasn’t just expensive. It meant the country’s industrial future rested on foreign-made black boxes.

That’s the gap Dr. Tamisuke Yokogawa stepped into.

He wasn’t a conventional “electronics founder.” He was already a prominent architect in Japan—successful as a scholar and a businessman, and deeply interested in the fundamentals behind the systems that made modern buildings possible: electrical power supply, and newer construction techniques like reinforced concrete using iron frames and steel bars. As he pushed into these modern projects, he ran into a basic obstacle: the instruments he needed simply weren’t available domestically. If Japan wanted to build modern infrastructure on its own terms, it had to learn these techniques and make these tools itself.

So on September 1, 1915, in Shibuya, Tokyo, Yokogawa began as an electric meter research institute. The entire “company” was four people—Dr. Yokogawa, alongside Ichiro Yokogawa and Shin Aoki, plus one more colleague—trying to kick-start a measurement industry from scratch.

From the beginning, Yokogawa wasn’t just a technical project. It was a philosophy.

Dr. Yokogawa told his young team, “You don’t need to worry about profits. Just learn and improve our technology. You must make products that earn us the respect of our customers.” In other words: credibility first. In the measurement business, trust is the product. If your meter is wrong, nothing downstream is safe.

That mindset got distilled into three principles that would become Yokogawa’s foundation: “quality first,” “pioneering spirit,” and “contribution to society.” For a tiny early-stage lab, putting quality ahead of survival-level profit chasing was unusual—almost reckless. But it was also a strategy: in a world where instruments decide whether an electrical system is stable or dangerous, reputation compounds.

Then came the work. The team started by taking apart the imported meters they were trying to replace—learning through detailed study rather than guesswork. One of those early engineers was Shin Aoki, just 26 years old at the time, who would later become Yokogawa’s vice president. He built prototypes and brought them to Tokyo Imperial University and private companies for inspection and evaluation. The goal was simple and brutally hard: match the accuracy and reliability of the best European and American instruments, and do it domestically.

They moved quickly. By 1917, the institute was producing and selling Japan’s first electric indicating instruments—ammeters, voltmeters, and power meters—earning a reputation for accuracy under the YEW brand. What started as a research institute was already turning into a real manufacturing business.

In 1920, that shift became official. After pioneering the development and production of electric meters in Japan, the operation was incorporated as Yokogawa Electric Works Ltd.

And Dr. Yokogawa’s “contribution to society” principle wasn’t just something you printed and forgot. It showed up in how he lived. He was a well-known collector of old Chinese china, and later donated his collection to Japan’s National Museum—an act widely seen as consistent with his view that valuable work should ultimately serve the public. He carried that belief into the company too, saying he didn’t want to hold company shares because he believed the company belonged to society.

That combination—engineering rigor, customer respect as the core metric, and a mission larger than the founders—set the pattern. The instruments came first, then the credibility, then the long relationships. It’s the same logic Yokogawa would follow for the next century as it moved from meters to industrial control systems: build something trustworthy enough to become invisible, because nobody talks about the tool that never fails.

III. Building the Measurement Foundation (1930s-1970s)

The decades between Yokogawa’s founding and CENTUM weren’t a straight line. They were a series of stress tests—economic turmoil, war, reconstruction—each one forcing the company to prove that its early ideals weren’t just slogans.

In the 1930s, Japan’s industrial base was being pulled toward militarization, and Yokogawa followed the demand. In 1933, it began researching and manufacturing aircraft instruments, alongside flow, temperature, and pressure controllers. On paper, that’s “diversification.” In reality, it was Yokogawa stepping out of the narrow world of electric meters and into something much bigger: the measurement and control of real industrial processes.

This was the moment Yokogawa started to look like the company it would become. Not a maker of one instrument, but a builder of the “mother tools of industry”—devices that sit upstream of everything else. Because in a plant, measurement comes before control. Control comes before optimization. And optimization is what makes modern industry viable at scale.

Then World War II ended, and Japan’s industrial landscape was shattered. But the post-war period also opened a new door: the rebuilding effort, plus the influx of capital, ideas, and exposure to Western technology. Yokogawa went public in 1948. In 1950, it developed Japan’s first electronic recorder—a meaningful leap from mechanical recording to electronic systems with higher precision and better compatibility with the control technology that was starting to emerge.

In 1955, Yokogawa took another step that would shape the next era: a technical assistance agreement with Foxboro in the United States. Foxboro was a leader in process control, and the partnership mattered for more than the specific technology it brought in. It connected Yokogawa to global instrumentation know-how and helped set the direction for its deeper move into process control throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

By 1957, Yokogawa was pushing further into advanced electronics with Japan’s first oscilloscope, the OL-51B model. That same year, it established a North American sales office—an early signal that the company intended to play beyond Japan.

Through the 1960s, the product line broadened into the core building blocks of industrial automation. Yokogawa entered the industrial analyzer market in 1964. It introduced vortex flowmeters in 1969. And in 1974, it accelerated its international footprint with manufacturing and sales offices in Singapore and Europe.

These weren’t random categories. Analyzers, flowmeters, temperature and pressure controllers—this is the sensory system of an industrial plant. But there was still a limitation. They were mostly standalone instruments, each doing its job in isolation. Operators and engineers still had to mentally integrate the readings, and the plant’s overall control approach was still centralized, expensive, and fragile.

The Singapore facility, established in 1974, turned out to be especially important. It wasn’t just another outpost; it gave Yokogawa a foothold in Southeast Asia and a base to grow with the region’s industrialization. Over time, it would also become central to the company’s globalization push.

By the mid-1970s, Yokogawa had what looked like a complete foundation: a broad measurement portfolio, a growing international presence, and a reputation for quality that traced directly back to Dr. Yokogawa’s original insistence on earning customer respect.

But the next step wasn’t going to be another instrument.

It was going to be a new way to run an entire plant.

IV. The CENTUM Revolution: Creating a Category (1975)

June 19, 1975 is one of those dates that doesn’t show up in most history books, but it should. That’s when Yokogawa announced CENTUM—the world’s first distributed control system, or DCS. And fifty years later, CENTUM is still here, now on its tenth generation.

To understand why that announcement mattered, you have to understand what “control” looked like before it.

In the early 1970s, the mainstream approach to process control was the one-loop pneumatic controller. Plants were run by what was called board operation: huge walls of panels packed with indicators, recorders, gauges, switches, and alarm lamps. Each loop had its own dedicated hardware. So if you were operating a large refinery—with thousands of loops—you weren’t “watching screens.” You were walking. Constantly. Reading needles, adjusting setpoints, acknowledging alarms, trying to stitch together a coherent picture of the plant in your head.

The workload was intense. The room was loud with signals. And the margin for error was thin.

But the deeper problem wasn’t the operators. It was the architecture.

Control systems were fundamentally centralized. Critical functions were concentrated in ways that made plants fragile: when a central component failed or had to be shut down, it could ripple through operations. In industries where “down” can mean unsafe, centralization is not just inconvenient—it’s a structural risk.

CENTUM’s breakthrough was a new philosophy: distribute the risk.

Yokogawa saw promise early in microprocessors—still a brand-new technology in those days—and bet that they could change industrial control from an analog and mechanical discipline into something digital and software-driven. CENTUM divided the control system into three functional components: the human-machine interface (an HMI, like a CRT with a keyboard), the controllers, and the control bus that connected them. Then Yokogawa gave that structure a name: distributed control system.

It sounds obvious now, because the whole industry works this way. In 1975, it wasn’t.

With CENTUM, the functions of the instrument panel moved onto the HMI, and board operation evolved into CRT operation. Logic that once had to be physically configured through relays could now be built inside the controller—more flexible, easier to change, and far more scalable.

Most importantly, it made plants safer. With control distributed across multiple processors, failures didn’t automatically cascade. If one controller went down, the impact could be localized to a portion of the plant while the rest kept running. Resilience wasn’t a bolt-on feature. It was the point.

CENTUM kept evolving after that first leap. As one of the first control systems to adopt microprocessors and a non-analog CRT interface, it reinvented itself generation after generation—shrinking in physical footprint while expanding in capability, integrating more production-related functions and information, and scaling to support enormous, complex facilities.

The timing helped, too. The microprocessor era was arriving. Engineers everywhere were exploring what these chips could do. But Yokogawa didn’t just experiment—it shipped. It translated an emerging technology into a mission-critical industrial platform.

And that created a moat that proved brutally durable.

CENTUM has been Yokogawa’s DCS brand since the first generation went to market in 1975. In the decades since, many early competitors in the DCS market were acquired, merged, or disappeared entirely—often taking their control platforms with them. Only a handful of the companies that helped define the category in the beginning are still around.

Yokogawa is one of them, and it built its reputation on a word that matters more than any feature list in industrial control: availability.

Yokogawa says its customers have achieved real-world system availability of 99.99999%—seven nines—since the invention of the DCS. That translates to less than a minute of DCS-related downtime over ten years. It’s an almost absurd claim, and it’s why CENTUM has stayed installed in places where downtime isn’t just expensive—it’s unacceptable.

The mechanism behind that reliability is a design philosophy of redundancy—specifically, Yokogawa’s Pair & Spare approach. In this architecture, each processor module has redundant CPUs running the same computations simultaneously, constantly comparing outputs. If an anomaly is detected—whether from electronic noise or other faults—the system initiates a bumpless switchover to the standby module. Operators may never even notice anything happened, because as far as the plant is concerned, it didn’t.

It’s the kind of engineering that feels excessive until you remember where these systems live: refineries, chemical plants, power stations—places where “close enough” is not a standard.

The market validated CENTUM in the only way that matters in industrial automation: by installing it, keeping it, and refusing to rip it out unless they absolutely had to. Yokogawa’s DCS became known for reliability, stability, and compatibility with previous versions. Over time, more than 30,000 systems were implemented in over 100 countries.

And the longevity wasn’t theoretical. The first-generation CENTUM made an early impact in the steel industry. A CENTUM system installed at NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION in 1982 ran for 33 years, supporting stable production of high-quality products, before it was retired during an upgrade—and even then, the system was donated by the customer.

A 33-year lifespan for a control system is extraordinary. But it fits the world Yokogawa sells into. Plants often operate on multi-decade timelines, and a vendor that can deliver continuity over that horizon doesn’t just win a deal. It becomes part of the plant.

CENTUM didn’t just launch a product line. It introduced a new category that became the industry standard, eventually adopted by every major competitor. But Yokogawa had the first-mover advantage, and it paired it with a relentless obsession: build a control system that’s so stable, it disappears into the background.

That’s how Yokogawa became the quiet giant.

V. Consolidation & Corporate Evolution (1980s-2000s)

CENTUM gave Yokogawa a category-defining product. The next twenty-five years were about turning that advantage into something more durable: a broader company, a bigger footprint in the world’s most important industrial regions, and a control platform that could keep modernizing without forcing customers to start over.

In 1983, Yokogawa merged with Hokushin Electric Works. Toward the end of the decade, it also entered the high-frequency measuring instrument business. The merger was a meaningful consolidation inside Japan’s measurement-instrument world: more scale, a wider portfolio, and more R&D muscle under one roof. A few years later, the company’s name caught up with what it had become. In 1986, it changed to Yokogawa Electric Corporation.

In the 1990s, Yokogawa kept widening its reach and its ambitions. It opened an office in Bahrain to oversee its Middle East business, and it pushed into new areas like confocal scanners and biotechnology. The Bahrain move, in particular, was a smart piece of positioning. Gulf producers were pouring capital into refineries, petrochemical complexes, and power infrastructure—exactly the kind of facilities where downtime is intolerable and reliability becomes a deciding factor, not a nice-to-have. Being on the ground mattered.

While the company was expanding geographically, CENTUM was evolving technologically. Through the 1980s and 1990s, Yokogawa developed digital DCS generations such as CENTUM XL and CENTUM CS, bringing more computing power and more automation capability into the platform. One shift in that era signaled where the industry was headed: human-machine interfaces moved toward PCs and the Windows operating system, which Yokogawa adopted as the standard HMI station for CENTUM CS 3000, released in 1998. This wasn’t just a new look for operators. It was Yokogawa aligning the front end of the control room with standardized enterprise computing—an architectural decision that would echo for decades.

The late 1990s also brought the CENTUM CS series into clearer focus. In 1997, Yokogawa launched CENTUM CS 1000, a DCS designed for small to medium-sized plants. Positioned as the successor to the globally best-selling μXL distributed control system, it marked a new starting point for Yokogawa’s systems business: the same CENTUM philosophy, but packaged to fit a wider range of facilities.

Then came another round of corporate build-out. In 2002, Yokogawa acquired Ando Electric. In 2005, it raised its international ambitions another notch with the establishment of Yokogawa Electric International in Singapore—setting up a hub designed to support a more global operating posture, not just a collection of overseas sales offices.

By the mid-2000s, Yokogawa was firmly a global player, with particular strength in the process industries: oil and gas, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and power generation. And the company’s most important competitive feature kept showing up in customer behavior. CENTUM wasn’t something you ripped out. It was something you upgraded. Relationships often spanned decades, with plants moving through multiple generations of CENTUM without needing a full replacement.

In 2008, Yokogawa introduced what it positioned as the next major step: CENTUM VP. It succeeded CENTUM CS 1000 and CENTUM CS 3000, and it did so while emphasizing backward compatibility and consistency with previous CENTUM systems. But VP wasn’t just “the next DCS.” Yokogawa framed it as redefining what a production control system should be: not only controlling and monitoring the plant, but also integrating plant information management, asset management, and operation support into a unified operating environment.

That mattered strategically. The more functions Yokogawa could fold into one platform, the larger its footprint inside each facility became—and the harder it was for a competitor to dislodge it.

Alongside CENTUM VP, Yokogawa launched its VigilantPlant initiative, a broader vision for how modern plants should operate. VigilantPlant aimed to enable an ongoing state of Operational Excellence: personnel who are watchful and attentive, well-informed, and ready to act in ways that optimize plant and business performance—reducing unplanned downtime, improving asset utilization, and adapting more quickly to shifting conditions.

But even as Yokogawa strengthened its position in the traditional automation world, the ground under its best customers was starting to shift. Oil and gas—the industry that had been such a rich source of large, complex control projects—was heading into an era of volatility, tightening regulation, and eventually the energy transition.

Yokogawa’s leadership could see where this led. The company couldn’t simply depend on its installed base and hope the old growth engines kept running. If the next era of industry was going to look different, Yokogawa would have to change with it.

VI. The Transformation 2017 Pivot: From Hardware to Solutions

By the mid-2010s, Yokogawa had a world-class control platform and an enormous installed base. But leadership could also see the trap: if you’re only a hardware and systems supplier, you eventually get pulled into feature checklists, price pressure, and project-by-project selling. The next era of value in industrial automation wasn’t just controlling a plant. It was helping customers run it better.

The move that signaled Yokogawa was serious came from an unexpected place: a British software and consulting firm that specialized in refinery optimization.

In 2016, Yokogawa acquired KBC Advanced Technologies. The deal was expected to close between April and June of that year, for approximately JPY30.8 billion, around $270 million. KBC was a U.K.-based provider of software and consultancy to the global oil and gas industry, focused on operational excellence and profit improvement across both upstream production and downstream refining, including refinery-integrated petrochemical complexes.

What made KBC unusual wasn’t just that it sold software. It sold outcomes. KBC paired process optimization and simulation software with consulting services built around that technology, and it had carved out a well-differentiated position by sitting right at the intersection of engineering reality and management-level decision-making.

Strategically, it was a sharp fit—and a real departure for Yokogawa.

KBC worked across the same kinds of facilities Yokogawa served, but at a different layer. Yokogawa’s world was the control system, the instruments, and the operational layer that keeps the plant safe and stable. KBC’s world was higher up the stack: optimization, simulation, and advisory work that could influence how a refinery is configured, how it’s operated, and where money gets spent. Put the two together, and Yokogawa could offer something broader than a DCS project: a combined portfolio of consulting, packaged software, control systems, and sensors.

That’s why Yokogawa described the combination as a “one-stop” offering—from client senior management on down to field operators, mainly in oil and gas. In plain terms, it was a bid to be present in every important conversation: from the boardroom decisions that determine strategy, to the control room decisions that determine uptime.

This also fit a wider industry pattern. Hardware is essential, but it’s hard to build durable differentiation when competitors can match specs and customers treat purchases as capital projects. Software and consulting come with different economics and stickier relationships: recurring revenue, higher margins, and deeper involvement in how customers actually make decisions. Yokogawa wasn’t just buying a product line; it was buying a new way to compete.

And KBC wasn’t the only piece. In December 2015, Yokogawa had acquired Industrial Evolution, Inc., adding cloud-based data services. Under the Transformation 2017 mid-term plan, the idea was to assemble a full digital stack: Yokogawa’s measurement, control, and information technologies at the base; a secure cloud platform to move and manage data; and KBC’s optimization software and consulting to turn that data into operational improvement. Yokogawa framed it as co-innovation with customers: not just installing systems, but jointly finding value in how plants are run.

Internally, this required Yokogawa to change what it meant to “deliver.” To better serve customers through solutions that improved efficiency and profitability, the company combined its system construction and lifecycle services with the consulting services KBC brought into the group. That is a different muscle than shipping instruments and commissioning control systems. It means selling expertise, sustaining long programs, and being accountable for results over time.

KBC, as part of Yokogawa, also emphasized a broader set of priorities—placing equal importance on people, the environment, and profits, and positioning its work as part of customers’ sustainability strategies. It described itself as a digital transformation company offering digital oilfield solutions, an asset digital twin, differentiated management and technical consulting, and extensions into real-time data and the process automation domain. Strip away the label, and the core idea is straightforward: use models and real-time operations data together to make better decisions and manage assets more effectively over their lives.

That’s where the digital twin concept became powerful in Yokogawa’s narrative. With a digital twin, a customer isn’t limited to seeing what the plant is doing right now. They can simulate scenarios, test changes before making them in the real world, and use data to improve operating and maintenance decisions. Combined with live plant data coming from control systems like CENTUM, KBC’s simulation and optimization software offered a path from monitoring to foresight.

At the same time, Yokogawa kept reinforcing the other half of the strategy: protect and grow the installed base. It leaned into migrations to CENTUM VP, noting it had successfully migrated over 350 non-Yokogawa systems, with the number steadily growing—systems from Bailey, Foxboro, Emerson, Eurotherm, Hitachi, Honeywell, Siemens, Taylor, Toshiba, and Allen-Bradley PLCs, among others.

That list tells you something important about this market. Many of those platforms were built by companies that have since been acquired, merged, or exited—leaving customers with aging systems and limited support paths. For Yokogawa, that churn created opportunity: be the stable destination, offer a credible upgrade path, and then expand from control into services and optimization.

Transformation 2017 was Yokogawa naming what it believed the future would reward. Hardware would remain non-negotiable—you can’t automate a plant without sensors, controllers, and systems. But the value was shifting toward the layers that help customers optimize operations, reduce energy consumption, predict failures, and navigate tighter regulatory and environmental constraints.

Yokogawa’s bet was that if it could own the reliable core and the intelligence above it, it wouldn’t just keep running the plant.

It would help run the business that depends on the plant.

VII. The Energy Transition & Sustainability Bet (2020-Present)

The 2020s forced an uncomfortable truth onto every industrial automation company: the safest place to stand—serving oil, gas, and heavy industry—was also where the ground was starting to move. Yokogawa’s response was its most ambitious repositioning yet: lean into sustainability and the energy transition, not as a side initiative, but as a new center of gravity.

That shift showed up first in how the company talked about itself. In fiscal year 2021, Yokogawa fundamentally revised its long-term business framework and rolled out a new medium-term plan: Accelerate Growth 2023 (AG2023). The message was clear: the company wanted “sustainable growth through the provision of shared value to society.” Over the three years through fiscal 2023, Yokogawa worked to build a structure centered on addressing broad social issues—part of a longer push toward where it wanted to be as a company in 2030.

Then in May 2024, Yokogawa formalized the next chapter with a new medium-term business plan: Growth for Sustainability 2028 (GS2028), covering the period through fiscal year 2028. GS2028 didn’t replace the earlier plans so much as extend them: more explicit ESG framing, more emphasis on sustainability transitions, and more weight on solutions that help customers modernize, decarbonize, and operate more efficiently.

The clearest “we mean it” moment came in June 2024, when Yokogawa acquired BaxEnergy, a leading provider of renewable energy management solutions (REMS). This wasn’t a small adjacency play. BaxEnergy brought a proven set of tools already adopted by major power companies across Europe. For Yokogawa, it was a way to step directly into the operating layer of renewable energy—where the job isn’t controlling a single plant, but coordinating fleets of assets, often distributed across large geographies.

The strategic logic fit Yokogawa’s history better than it might look at first glance. Industrial automation is about making complex, high-stakes systems behave predictably. Renewable energy operators face a similar reality, just with different physics and different constraints: intermittent generation, grid compliance, and the constant pressure to maximize output while keeping maintenance efficient. BaxEnergy’s REMS spanned that value chain, helping operators manage wind, solar, hydro, geothermal, and more by integrating data from turbines, inverters, and other equipment. BaxEnergy’s platform was also designed to be flexible and scalable—deployable without forcing customers to modify their core IT and business systems. In other words: it met customers where they already were.

BaxEnergy also came with a performance promise: its solutions had demonstrated the ability to enhance plant availability by up to 10%. For renewable operators, that’s the difference between an asset that looks good on paper and one that actually hits economic targets in the real world.

Even the origin story of the acquisition reflects how these deals often happen in practice. BaxEnergy showed up at the Renewable Energy 2023 event in Tokyo in March 2023. That’s where Yokogawa first met BaxEnergy’s team and got hands-on exposure to the technology. From there, the conversation accelerated into a deal that would become one of Yokogawa’s most visible moves of the decade.

And Yokogawa didn’t stop at “renewables software.” It moved to broaden BaxEnergy into a more complete digital platform for the energy transition. Yokogawa announced that it had acquired Intellisync, a provider of cybersecurity and digital transformation solutions, and WiSNAM, a developer of advanced grid control and energy management solutions. Both companies would be integrated into BaxEnergy, strengthening the offering across cybersecurity and grid control and helping Yokogawa build what it described as a digital hub for renewables.

The Intellisync piece mattered for a reason that’s easy to miss if you’ve grown up thinking of power plants as physical infrastructure. Renewable systems are increasingly software-defined, internet-connected, and tightly coupled to grid management. That connectivity creates a bigger attack surface than older, more isolated infrastructure. Intellisync, established in 2017, specialized in cybersecurity as a service and operated a dedicated 24/7 network and security operations center—capabilities that become essential once your “plant” is really a distributed fleet tied into the grid.

With BaxEnergy providing renewable energy management and Intellisync providing cybersecurity, Yokogawa could offer something closer to an integrated operations-and-security package—addressing not just performance and uptime, but also the risk profile of modern energy systems.

By 2025, BaxEnergy was signaling its own expansion inside the larger Yokogawa portfolio. BaxEnergy, a Yokogawa company and a full-service partner to renewable energy power companies, announced the launch of its REMS portfolio. At BaxSummit 2025, the company unveiled a new comprehensive REMS portfolio, positioning itself as a fuller-service partner to renewable operators. The event also included the announcement of BaxEnergy’s entry into the North American market—an important step in expanding beyond its European base.

While Yokogawa was building out its renewables stack, a second transformation continued in parallel: cloud and industrial IoT. In 2021, the company launched the OpreX Control Care cloud service and acquired Industrial Control Systems, Inc. The direction here echoed the Transformation 2017 playbook: get closer to customers’ ongoing operations, deliver value continuously, and build offerings that look less like one-time projects and more like lifecycle services.

Then, in June 2025, Yokogawa brought its legacy platform into the same “future-ready” narrative. At a press conference on June 3, 2025, the company marked the 50th anniversary of CENTUM—the DCS first introduced in 1975—and used the moment to unveil a strategy focused on autonomous operations, anchored by the release of CENTUM VP R7.

Yokogawa positioned VP R7 around the concept of “Unchanging Value and New Innovation.” The unchanging side was what CENTUM has always sold: reliability, stability, and continuity—now reinforced with robust cybersecurity and a comprehensive engineering and service framework. The new innovation side was about widening the data lens: secure, broad integration across plant equipment, and an expanded scope for autonomy. By leveraging collected data to identify and characterize process-specific phenomena, and by detecting deviations from expected behavior, VP R7 was designed to support deeper operational optimization.

“Autonomous operations” is the endpoint of that story. Yokogawa’s vision is systems that learn and adapt to maintain optimal, safe operations with less human intervention—offering stable operations less affected by external change, optimization beyond human capabilities, and continuous transfer of knowledge and experience.

This wasn’t presented as a purely theoretical future. Yokogawa stated it already had experience integrating an autonomous control AI with CENTUM VP, and that this had been officially adopted to control operations at a chemical plant. For the achievement—reducing environmental impact, lessening workloads, and improving safety—Yokogawa received the Prime Minister’s Prize, the highest award in the 2023 Japan Industrial Technology Awards.

Even corporate governance became part of the narrative arc. In January 2025, Yokogawa received the METI Minister’s Award for Corporate Governance of the Year 2024, recognizing governance practices intended to support strategic growth and long-term sustainability.

And GS2028 put measurable intent behind the repositioning. Yokogawa said it had set focus areas contributing to sustainability transitions for each business segment and had already started activities. As it grew the business, it aimed to increase the ratio of sustainability transition sales from 40% to 50% by fiscal year 2028.

Under the same umbrella, Yokogawa continued to extend the OpreX brand with new offerings, including OpreX Robot Management Core and OpreX Intelligent Manufacturing Hub. Taken together—the renewables software platform, cybersecurity capabilities, cloud services, and a DCS roadmap aimed at autonomy—Yokogawa’s bet for the 2020s was straightforward:

keep being the company that never fails in the control room, while becoming the company customers call when the entire system has to change.

VIII. Business Model Deep Dive

To understand Yokogawa as a business, you have to understand how it actually makes money—and why the economics of industrial automation are so different from most technology markets.

In fiscal year 2024, orders rose to JPY598.6 billion, up 8.0% excluding exchange-rate effects. Sales came in at JPY562.4 billion, up 1.9% on the same basis. The gap between orders and sales matters here because Yokogawa is, in many cases, delivering large projects that roll through revenue over time.

The company’s revenue engine is the Industrial Automation and Control Business. This is Yokogawa’s home turf: everything from the field instruments that measure what’s happening in a plant—flowmeters, pressure transmitters, process analyzers—to the systems that act on that information, like production control systems, programmable logic controllers, industrial recorders, and the software layers that sit on top. The promise to customers isn’t just “we sell you hardware.” It’s “we lower your plant’s lifecycle costs” by helping it run safely, reliably, and efficiently for decades.

Alongside that core sits the Measuring Instruments business, which focuses on things like waveform measuring instruments, optical communication-related measuring instruments, signal generators, and other power, temperature, and pressure measurement tools. The product categories differ, but the philosophy is the same: high-precision measurement as a foundation for critical work.

Put all of this together, and Yokogawa’s product portfolio—systems, software, data acquisition instruments, and field instruments—does something deceptively simple: it connects plant operations to corporate management. And increasingly, Yokogawa pairs the technology with consulting and execution services, giving customers not just tools, but help making timely operating decisions. Geographically, the majority of sales come from Asia, with Japan as a key region.

But the most important economic idea in Yokogawa’s model is its installed base.

Since CENTUM’s debut in 1975, Yokogawa systems have been installed in more than 30,000 facilities across over 100 countries. That footprint is what turns the business from “sell a system” into “own a relationship.” CENTUM VP is positioned around the attributes that make that installed base sticky: high availability, interoperability across the enterprise, an advanced solutions portfolio, and defense-in-depth cybersecurity that has been certified by third parties.

Once you’re embedded in a refinery or chemical complex, you don’t just get paid once. The initial system sale brings hardware revenue, but the real compounding comes afterward: software upgrades, spare parts, maintenance services, consulting engagements, and—eventually—migrations to the next generation. In practice, a control system installed at a major plant can keep generating revenue for 20 to 30 years or more.

Over the last decade, Yokogawa has also made the shift toward recurring revenue an explicit priority. KBC brought software licensing and consulting fees. BaxEnergy added renewable energy management subscriptions. And cloud offerings like OpreX Control Care create ongoing service relationships that look much more like continuous delivery than the old one-time project cycle.

Another stabilizer is end-market diversification. Yokogawa’s systems show up across industries—oil refining, petrochemicals, specialty chemicals, textiles, steel, pharmaceuticals, food, water, electric power, and gas—which helps cushion the company from downturns in any single sector.

Geography matters too, and the Middle East has been especially important. In fiscal year 2024, orders increased significantly, driven by strong results in the region (again, excluding exchange-rate effects). Sales also benefited from foreign exchange and from the delivery of large projects that had been booked through the end of fiscal year 2023.

Finally, capital allocation shows Yokogawa trying to balance investment with shareholder returns. For FY24, the annual dividend was increased by ¥18 to ¥58 per share, and the company announced a share buyback of up to ¥20 billion, with an acquisition period from March 5, 2025 to December 31, 2025.

IX. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Industrial control is one of those markets where “just build a better product” isn’t enough. Yokogawa has been doing this since 1915, is headquartered in Musashino, Tokyo, and operates at global scale with more than 19,000 employees and presence across more than 60 countries. But the real barrier isn’t size. It’s trust.

In mission-critical process industries, new entrants face a wall of hard-earned credibility. Refineries, chemical plants, and pharmaceutical facilities don’t buy control systems the way companies buy software. They buy them the way they buy safety. Regulatory requirements are complex, safety certifications are rigorous, and customer qualification cycles can stretch for years. A vendor has to prove, repeatedly, that it won’t be the reason a plant trips offline—or worse.

That said, the entry points are shifting. Cloud-native and software-first players can start higher up the stack, in areas like optimization, monitoring, and industrial analytics, without immediately challenging the core DCS. Companies like Nominal, Phaidra, and Inductive Automation may not rip out CENTUM in a refinery tomorrow, but they can win greenfield projects and begin to commoditize slices of the automation value chain over time.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Yokogawa’s supplier risk is relatively contained. It manufactures many critical components in-house, especially around CENTUM, and most standard electronic parts are commoditized with multiple sourcing options. Scale helps on purchasing, but the bigger advantage is control: vertical integration reduces dependency on any single vendor and lowers the odds of a supplier becoming a strategic bottleneck.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

The buyers here are some of the toughest on the planet: major oil and gas companies, chemical producers, and large industrial operators with sophisticated procurement teams. They have leverage.

But DCS purchasing power has limits, because the product sits in the “can’t fail” category. Price matters, but it’s rarely the deciding factor. Switching costs are enormous: integration work, operator training, engineering change control, and recertification—often inside plants designed to run for decades. For customers who’ve operated CENTUM for years, the platform is embedded not just in hardware and software, but in procedures, training programs, and institutional knowledge.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MEDIUM

There’s no real substitute for a DCS in large-scale, continuous process operations. You can add edge compute, you can add cloud analytics, you can modernize the supervisory layer—but a refinery or petrochemical plant still needs deterministic control with reliability designed for industrial reality, not consumer uptime.

Where substitutes do show up is at the edges. PLC-based systems compete in simpler or lower-end applications, and cloud-native architectures can take share in smaller, modular, or batch-oriented environments. Over time, those approaches can nibble at pieces of what traditional DCS vendors used to own end-to-end—but they haven’t replaced the DCS in the core use cases that define Yokogawa’s installed base.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is intense, but it’s not chaotic. The top suppliers—ABB, Emerson, Honeywell, Siemens, and Yokogawa—account for a large share of the DCS market, and the battles tend to be fought on major project awards, lifecycle support, and trust, not on who can discount harder.

Yokogawa also faces a broad competitive set across adjacent categories. Its competitors include Siemens, ABB, Honeywell, Emerson, Schneider Electric, Atos, Rockwell Automation, Bosch, Eaton, Endress+Hauser, Danfoss, Hitachi, Azbil, Tektronix, United Technologies, 3M, Alstom, Hubbell, and FANUC.

The fight is ultimately about who customers believe will still be standing—and still supporting the platform—ten, twenty, and thirty years from now. Yokogawa’s strengths have historically been deepest in Asia and the Middle East, and in oil and gas–heavy process environments where reliability and lifecycle cost beat flashy feature sets.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Moderate. Yokogawa benefits from spreading R&D and product development across a large installed base and global manufacturing footprint. But it competes with giants like Siemens and Honeywell, which can amortize development costs across even larger revenue pools.

Network Effects: Limited in the classic “social network” sense, but meaningful ecosystem effects. A bigger CENTUM footprint means more trained engineers, more system integrators, more proven interfaces, and more third-party tooling that knows how to live alongside it. In industrial automation, that ecosystem depth behaves like a quiet network effect.

Counter-Positioning: Yokogawa’s “quality first” culture and extreme reliability posture function as counter-positioning. It’s hard for competitors to credibly match “seven nines” availability without adopting the same kind of engineering conservatism, redundancy philosophy, and quality discipline—changes that can conflict with how their organizations are optimized to ship and scale.

Switching Costs: Extraordinarily high. Yokogawa has successfully migrated over 350 non-Yokogawa systems, and that fact cuts both ways: it highlights a growth opportunity for Yokogawa, but it also reveals the central moat of the category. Migrations require major engineering effort—hardware replacement, software reconfiguration, operator retraining, and often regulatory re-certification. Customers don’t switch casually.

Branding: Strong where it counts, invisible where it doesn’t. Yokogawa isn’t a household name, but inside industrial automation, the name signals reliability and engineering seriousness—the kind of reputation that influences plant managers and automation engineers far more than consumer brand awareness ever could.

Cornered Resource: Deep institutional knowledge. Fifty years of CENTUM-era process control experience—plus the broader century-long measurement heritage—means Yokogawa has seen an enormous range of plant configurations, edge cases, failure modes, and operational constraints. That accumulated learning is difficult to replicate quickly, even with capital.

Process Power: Real, and unusually defensible. Yokogawa’s Pair & Spare architecture and rigorous quality processes aren’t just features; they’re repeatable organizational capabilities. Consistently delivering near-continuous availability across thousands of installations requires manufacturing discipline, engineering controls, and field-service execution that many competitors struggle to match at the same level of reliability.

X. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to track whether Yokogawa’s strategy is working in real time, three indicators matter more than almost anything else:

1. Orders-to-Sales Ratio and Order Backlog

Yokogawa is a project-driven, capital-goods business. That means orders tend to show up first, and revenue follows later—sometimes months later, sometimes years. In fiscal year 2024, orders were JPY598.6 billion (up JPY43.5 billion, or +8.0%, excluding exchange-rate effects), while sales were JPY562.4 billion. That spread matters: it suggests demand is healthy and backlog is building. For investors, this ratio is one of the cleanest early signals of where reported revenue is likely headed next.

2. Recurring Revenue Mix and Software Growth

Transformation 2017 wasn’t about selling more boxes. It was about moving up the stack into solutions—software, consulting, and services that are higher margin, more predictable, and harder for competitors to displace. The question to keep asking in the numbers is simple: how much of Yokogawa’s revenue is becoming recurring?

Progress here shows up in growth in software licensing, consulting, and subscription-style offerings—especially through businesses like KBC and BaxEnergy. If the mix keeps shifting away from one-time hardware and project revenue and toward ongoing software and services, that’s Yokogawa successfully changing its economic model, not just its messaging.

3. Sustainability Transition Sales Ratio

Yokogawa has put a specific stake in the ground: it plans to increase the ratio of sustainability transition sales from 40% to 50% by fiscal year 2028. This is one of the most important “strategy becomes measurement” metrics in the story. It’s a direct read on whether Yokogawa is actually repositioning toward the energy transition—renewables, decarbonization, and efficiency—rather than simply continuing to ride its legacy base in oil and gas.

XI. Risk Factors and Regulatory Considerations

It’s easy to get swept up in the elegance of the strategy—CENTUM as the reliable core, software and services moving up the stack, renewables as the next growth engine. But in a business that sits at the heart of critical infrastructure, the risks aren’t abstract. They’re structural, and they deserve to be stated plainly.

Material risks warrant explicit acknowledgment:

Energy Transition Timing Risk: Yokogawa is walking a tightrope. Its biggest installed base still lives in fossil-fuel-heavy industries, but its long-term growth narrative increasingly depends on renewables and sustainability-oriented work. If the transition accelerates faster than expected, legacy customers could pull back on capital spending before Yokogawa’s newer businesses scale enough to compensate. If the transition slows or stalls, the company’s investments in BaxEnergy and adjacent capabilities may deliver less than hoped.

Competitive Displacement Risk: The DCS market is stable until it isn’t. Cloud-native automation platforms and software-first architectures could gradually chip away at traditional DCS value—especially in greenfield projects, where buyers aren’t constrained by legacy systems and decades of procedures. Yokogawa can keep winning migrations in brownfield plants, but the long-term threat is that new facilities may be designed around different assumptions, shrinking the advantage of CENTUM’s historical architecture.

Currency and Geographic Concentration: Yokogawa’s footprint is global, but meaningful revenue concentration in Asia and the Middle East exposes it to regional economic cycles and geopolitical volatility. On top of that, currency swings—particularly in the yen—can materially affect reported results. The company specifically cites foreign exchange movements, including the U.S. dollar, the euro, Asian currencies, and Middle Eastern currencies, as factors that can influence business forecasts.

Acquisition Integration Risk: A major part of Yokogawa’s transformation has been built through acquisitions—KBC, BaxEnergy, Intellisync, and WiSNAM—and the strategy only works if these businesses integrate well and the promised synergies show up in reality. There’s evidence this can be difficult. Yokogawa recorded impairment losses tied to goodwill from acquisitions, including U.S.-based consolidated subsidiaries PXiSE Energy Solutions, LLC and Yokogawa Fluence Analytics, Inc., and Germany-based Yokogawa Insilico Biotechnology GmbH, after results came in below the original business plans. In other words: the company has already had to write down deals when performance didn’t match expectations.

Cybersecurity Liability: As control systems become more connected, the stakes of cybersecurity rise. Yokogawa has invested in security capabilities, but a successful cyberattack on a customer installation could create serious reputational damage and potential liability—even if the root cause isn’t solely within Yokogawa’s products. In mission-critical environments, customers don’t just remember who caused the breach. They remember whose system was running when it happened.

XII. Conclusion: The Invisible Infrastructure of Modernity

Yokogawa Electric Corporation represents a particular kind of excellence: the kind that works so consistently you stop noticing it’s there. When a refinery runs smoothly year after year, nobody thinks about the control system vendor. When a pharmaceutical plant hits precise specifications batch after batch, regulators don’t send thank-you notes to the automation supplier. In this world, credit is silent. Blame is loud.

For 110 years, Yokogawa has built its business around preventing the loud moments. And for more than 50 of those years, CENTUM has kept evolving as a core system for plant operations—defined by reliability, stability, and continuity. By strengthening how plants monitor, control, and respond, Yokogawa has helped customers improve productivity, reduce energy consumption, and run safer operations.

The investment case comes down to a few compounding advantages that fit together. First is the installed base: more than 30,000 CENTUM systems, spread across more than 100 countries, embedded in facilities that are designed to operate for decades. That installed base isn’t just history—it’s an annuity of upgrades, services, parts, and migrations. Second is the brand promise that matters most in industrial control: “seven nines” availability. In environments where downtime can become danger, that reputation is real differentiation. Third is the strategic pivot: Yokogawa has been moving up the stack into software, consulting, and solutions, and positioning itself for the sustainability and energy transition work that customers increasingly must do.

The trade-off is that none of this is automatic. Investors have to weigh execution risk in the company’s transformation strategy, competitive pressure from both familiar giants and cloud-native challengers, and exposure to industries facing long-term structural change—especially fossil fuels. If Yokogawa wants to be valued more like a software and solutions company, it has to keep proving it in the numbers: recurring revenue growth, integration success, and sustained margin improvement.

Kunimasa Shigeno, President and CEO of Yokogawa, put the company’s ambition this way: “Industries around the world are undergoing a major transformation to build a more sustainable society. Expectations for control technology are higher than ever, ranging from the ever-present need for enhancements to safety and efficiency and for progress to be made in digitalization and decarbonization. CENTUM is now evolving beyond the boundaries of a traditional DCS and growing into a versatile solution that addresses diverse business needs.”

It’s a fitting arc. What began in 1915 as a small institute trying to free Japan from dependence on imported electric meters became a company that helps run the world’s most complex industrial systems. Dr. Tamisuke Yokogawa’s original idea—earn customer respect through technology, and build products that contribute to society—didn’t disappear as the company scaled. It became the thread connecting a century of instruments, control systems, and now software-driven operational intelligence.

The quiet giant keeps doing what it has always done. In control rooms around the world, operators trust CENTUM to carry them through another shift. In refineries, chemical plants, power stations, and pharmaceutical facilities, Yokogawa sits in the background as part of the invisible infrastructure of modern life. And in Musashino, Tokyo, a 110-year-old company is preparing for its next transition: from automation toward autonomy, from a fossil-heavy installed base toward renewables, and from hardware projects toward solutions.

The story isn’t finished. But for investors looking for exposure to the systems that keep industrial civilization running, Yokogawa offers something rare: a century-long track record of durability, a culture built around “quality first,” and a strategy that’s explicitly designed for the world that comes next.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music