Renesas Electronics: The Phoenix of Japanese Semiconductors

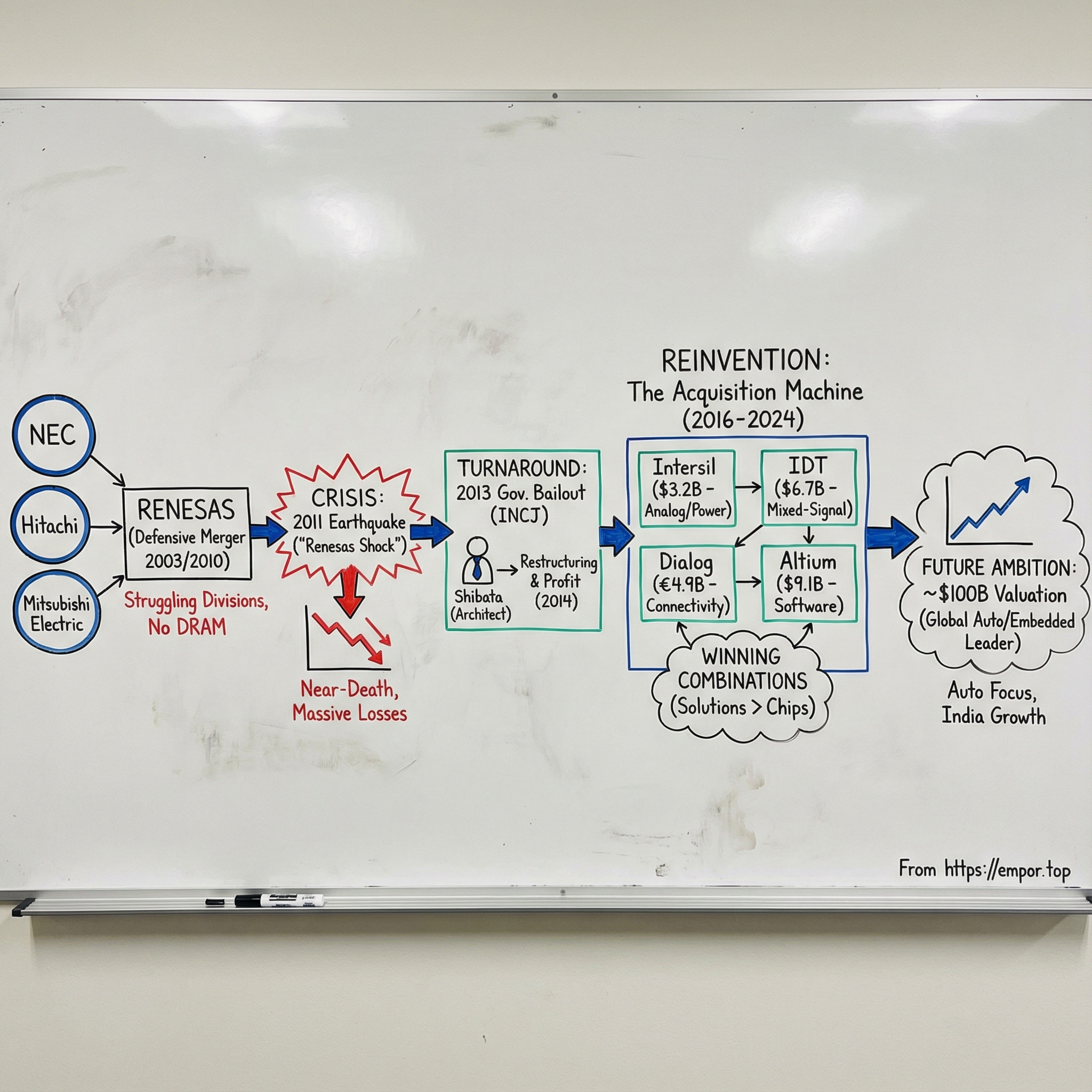

Introduction: From Near-Death to Acquisition Machine

Picture Tokyo, September 2013.

Renesas is a semiconductor giant in name and a mess in reality—bleeding cash, still recovering from the 2011 earthquake’s damage, and watching customers quietly redesign their products to rely on someone else’s chips. The stock has cratered. Analysts are sharpening the eulogies. Then the lifeline arrives: a government-led rescue that effectively puts the company under state control.

And inside that moment—when most turnarounds are still PowerPoint and prayer—Renesas is about to find its architect. A former investment banker, with stints at Merrill Lynch and Central Japan Railway, will help turn this near-bankrupt merger into one of the semiconductor industry’s most aggressive dealmaking machines.

Fast forward a decade. Renesas is no longer a ward of the state. It’s a roughly $35 billion company with a stated ambition to reach around $100 billion in market value by 2030—largely by buying its way into the products and capabilities it can’t realistically build fast enough on its own.

That arc is even more surprising when you remember what Renesas was supposed to be at birth: the consolidation of the chip operations that originated inside NEC, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi Electric. In 2009, the combined business ranked as the world’s No. 3 chipmaker by sales, behind Intel and Samsung. But Japan’s electronics champions—the core customers that had once pulled these companies forward—were losing ground globally. As they declined, Renesas declined with them.

Then came another blow: the March 2011 earthquake damaged a key factory, and automakers—terrified of single-supplier risk—started to diversify away. Renesas soon ceded ground to rivals, including NXP Semiconductors.

So this isn’t just a comeback story. It’s a case study in how mergers can fail to save you, how a crisis can permanently change customer behavior, and how government intervention—rarely celebrated in corporate lore—can sometimes create the breathing room for a real rebuild.

Renesas also mirrors the broader trajectory of Japan’s semiconductor industry: the 1980s golden age, the long erosion as Korean and Taiwanese competitors rose, and the repeated attempt to claw back relevance through consolidation. Renesas itself was born from defensive mergers—plural—and still nearly died.

And yet, today it remains a major force. Renesas was among the world’s six largest semiconductor companies through much of the 2000s and early 2010s. By 2023, it ranked 16th globally in semiconductor sales and second in Japan. In 2024, it ranked second in automotive microcontrollers behind Infineon, and third in the overall microcontroller market behind NXP and Infineon.

The questions underneath the Renesas story go way beyond chips: Why do mergers so often fail to create value? When can a government-backed rescue enable, rather than distort, a turnaround? And what’s the real strategic logic of buying what you can’t build—especially when organic growth is structurally harder than it used to be?

The Japanese Semiconductor Golden Age and Decline

To understand Renesas, you have to start with the thing it inherited: the extraordinary rise—and then the long, grinding fall—of Japan’s semiconductor industry. Few industries have ever swung that hard, that fast.

In the 1980s, Japan didn’t just compete in chips. It ran the table. At its peak, Japanese companies accounted for roughly half of global semiconductor revenue. And in memory, they were even more dominant. This wasn’t an accident of timing. It was the product of coordinated industrial policy, relentless manufacturing discipline, and a national obsession with quality.

A defining moment came in the late 1970s, when Japan’s biggest chipmakers—Fujitsu, NEC, Hitachi, Mitsubishi Electric, and Toshiba—formed the VLSI Technology Research Association. Backed by government coordination, the consortium helped push Japan to the front of the DRAM race. By 1980, Japan had developed 256K DRAM ahead of the U.S. Within a few years, the country’s DRAM share surged—peaking at nearly 80% in 1987—with Japanese chips earning a reputation for reliability strong enough to command premium positions with major American computer manufacturers.

By 1989, the scoreboard looked unreal: six of the world’s top ten semiconductor companies were Japanese. NEC, Hitachi, Toshiba, Fujitsu, Mitsubishi Electric, and Matsushita had seemingly conquered an industry the U.S. had invented.

But dominance creates enemies—and sometimes policy.

One of the most important turning points was the 1986 U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement, signed to defuse a heated trade conflict. Among other effects, it pressured Japanese manufacturers to raise prices and opened the door for American firms to claim a minimum foothold in Japan’s domestic market—often described as a 20% target share. It also constrained the kind of aggressive pricing tactics that had helped Japan win in commoditized memory. U.S. DRAM survivors like Texas Instruments and Micron benefited in the latter half of the decade.

Then Japan’s broader economy cracked. When the country’s asset bubble burst around 1990, the semiconductor industry didn’t collapse overnight—but it lost its tailwinds. The “Lost Decade” that followed brought stagnation and balance-sheet repair. Big companies pulled back on investment and R&D just as the global industry was entering an era where staying on the frontier required constant, enormous spending.

And the competitive threats weren’t standing still.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Japanese firms steadily lost ground to South Korean and Taiwanese players that had structural advantages Japan didn’t. Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix scaled massive memory fabs with strong backing and took over the DRAM business Japan had pioneered—turning it into a brutal commodity arena. Taiwan became the manufacturing engine for the new fabless era, with foundries like TSMC and UMC enabling chip designers around the world to innovate without owning factories. Japan, by contrast, stayed largely committed to the integrated-device-manufacturer model—designing and manufacturing under one roof—an approach that became harder to sustain as costs and complexity exploded.

There’s a deeper irony here: Japan had mastered DRAM, but didn’t capture the biggest strategic prize that emerged alongside it—microprocessors and the platform ecosystems built around them. American companies adapted. Intel leaned into microprocessors. Qualcomm and NVIDIA rode the fabless model. Japan’s champions, tied to their manufacturing heritage and exposed to the commoditization of memory, found themselves fighting the last war.

The industry tried to consolidate its way out. In 1999, for example, Hitachi and NEC merged their memory operations into Elpida Memory—an attempt to create a national champion that could survive the memory bloodbath. Elpida struggled for years, filed for bankruptcy in 2012, and was later acquired by Micron.

By the late 2010s, the reversal was stark: Japan’s global semiconductor market share had fallen to around 10%, down from the roughly 50% heights of the 1980s.

This is the world Renesas was born into. Not a world of swagger and expansion, but one where once-proud chip divisions were shrinking, merging, and searching for a way to stay relevant. Renesas wasn’t created as a bold strategic leap forward. It was a defensive move—three struggling conglomerates trying to salvage what they could through consolidation.

The Merger of Necessity: Creating Renesas (2002–2010)

Renesas didn’t appear because Japan’s electronics giants woke up one day with a bold new vision.

It came together in two moves, seven years apart, and both were born from the same uncomfortable reality: the standalone chip divisions inside Hitachi, Mitsubishi Electric, and NEC were getting harder to justify. Costs were rising, margins were thinning, and the old structure wasn’t working. The hope was that scale—finally—would.

Phase 1: Renesas Technology (2003)

On April 1, 2003, Hitachi (55%) and Mitsubishi Electric (45%) combined their semiconductor businesses into a new joint venture: Renesas Technology.

The launch messaging was triumphant. Renesas Technology even described itself as having “officially separated” from its parents and beginning operations as a world-leading system LSI company. But beneath the confidence was something more telling: two industrial titans were admitting that chips, on their own, had become too expensive and too volatile to run as independent empires.

The new company did have real scale. It was one of the largest chipmakers in the world at the time and the leading supplier of microcontrollers, with a huge workforce and a sales target that made it look like a juggernaut.

What it didn’t have—by design—was DRAM.

Both Hitachi and Mitsubishi had already carved out their memory operations, because the DRAM business had turned into a cash-consuming commodity grind. That crown jewel of Japan’s semiconductor era was now radioactive. Much of that separated DRAM effort ended up on a parallel track that fed into Elpida Memory, which later filed for bankruptcy in 2012 and was acquired by Micron.

Renesas Technology’s strategy was to go where Japan still had an edge: microcontrollers, automotive, and system-on-chip products, plus analog devices—areas where deep customer relationships and reliability mattered. The pitch was classic IDM logic: one company, controlling R&D, design, manufacturing, and support end-to-end, delivering “whole product” solutions to embedded customers.

It sounded clean. But it didn’t solve the bigger problem: combining two under-pressure organizations doesn’t automatically produce a healthy one.

Phase 2: NEC Electronics Joins (2010)

Seven years later, the Hitachi–Mitsubishi combination still wasn’t enough. So the industry tried again.

NEC had already spun off its semiconductor operations into NEC Electronics in November 2002. Then, in April 2010, NEC Electronics merged with Renesas Technology to create Renesas Electronics.

This was the moment Renesas became a true national champion: the microcontroller, analog, and system-on-chip portfolios of NEC, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi Electric, folded into one company. By revenue, it was estimated to be the fourth largest semiconductor company in the world. In microcontrollers, it was the global leader.

And yet, if you looked inside the organization, it wasn’t a clean “1 + 1 + 1 = 3” story. It was three large Japanese corporate cultures trying to become one operating system. Decision-making was still built around committee consensus. The similarities between the organizations didn’t smooth integration; they often made the differences sharper. And in that environment, clear accountability was hard to create—exactly what you need when you’re trying to turn around a struggling business.

The Failed Mobile Bet

As if integration wasn’t hard enough, Renesas also decided it needed a big swing in mobile.

In December 2010, Renesas Mobile Corporation was formed by combining Renesas’s mobile business with assets acquired from Nokia’s wireless modem unit. The ambition was straightforward: ride the growth of smartphones and become a serious player in mobile chips.

But the timing was brutal. The smartphone era was consolidating around players with massive scale and tightly integrated platforms, and Renesas couldn’t get to profitability fast enough. By 2013, it transferred LTE assets to Broadcom. By 2014, the subsidiary was dissolved.

It wasn’t just a failed bet. It was an expensive distraction at the exact moment Renesas needed focus, speed, and discipline most.

Catastrophe: The 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and "Renesas Shock"

Renesas had barely finished merging three corporate lineages into one company when nature delivered a stress test no integration plan could survive.

In March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck. And for Renesas—already stretched thin—the quake didn’t just damage buildings. It exposed a single point of failure that the global auto industry didn’t fully realize it had.

The Naka Factory Crisis

Renesas’s Naka factory in Hitachinaka, Ibaraki Prefecture, was hit hard. Years later, employees and executives still referred to the event by the name it earned inside the industry: the “Renesas Shock,” the disruption that crippled a key automotive chip supplier and helped bring global auto production to a halt.

At Naka, the destruction was brutally practical. Electrical and gas lines were severed. Clean room tools were knocked out of alignment and tossed around. And even if you had the parts and people to fix everything, getting them there was its own problem—trains were down, roads were disrupted, and gasoline was scarce.

This wasn’t just any plant. Naka was a flagship facility, famous in the industry: when it opened in 2000, it was the first 12-inch wafer fab in the world. It produced automotive microcontrollers—chips that didn’t have quick drop-in replacements, and that sat at the heart of vehicles’ electronic systems.

Naka accounted for roughly 15 percent of Renesas’s wafer output. After the quake, the company managed to shift about 60 percent of production to other sites. That helped—but it wasn’t nearly enough to prevent a shockwave.

Global Supply Chain Ripple Effect

The ripple didn’t stay in Japan.

Modern cars depend on thousands of electronic components, and Renesas microcontrollers were embedded everywhere—engine management, safety systems, and countless other functions. Under the lean, just-in-time philosophy pioneered by Toyota, the system was efficient… right up until it wasn’t. There was almost no buffer inventory anywhere in the chain.

Carmakers around the world discovered they were relying on Renesas for critical chips—and that one of the most important production sites was suddenly offline. The “Renesas Shock” spread through the industry as assembly lines in North America, Europe, and Asia slowed or stopped, not because factories couldn’t build cars, but because they couldn’t get one small component that everything else depended on.

The Remarkable Recovery

What followed was a recovery story that became legend in manufacturing circles—an all-hands, around-the-clock mobilization that showed what coordinated industrial urgency looks like.

Early assessments suggested Naka would take six months to restart, and even that estimate was considered aggressive. Instead, Renesas pulled off the near-impossible: the fab was back online in about three months, with production restarting in June.

At the peak, Renesas said roughly 2,500 people per day were working on the recovery, running an enormous number of tasks in parallel. Help poured in from across the ecosystem—engineers from equipment suppliers, and even competing companies that deferred their own orders for hard-to-acquire tools and supplies so Renesas could get what it needed faster. In total, the effort involved tens of thousands of people supporting repairs, restoration, and replacement of damaged machinery.

The Cost of the Disaster

Renesas later estimated that in the three months after the earthquake it lost 11.9 billion yen (about $156 million at the time), largely due to damage at Naka.

But the deeper cost wasn’t what hit the income statement. It was what changed in customers’ minds.

The quake forced a rethink of supply chain risk—especially the doctrine that inventory was “evil” and should be minimized at all costs. Automakers began reevaluating how much redundancy and buffer stock they needed to survive the next unforeseeable catastrophe.

And critically for Renesas, the industry’s response was durable: even after Naka came back, customers had learned a lesson they couldn’t unlearn. They diversified away from single-source dependence. Renesas recovered operations with heroic speed, but it didn’t fully regain the market position it lost in the aftermath—ground that rivals like NXP captured, and that Renesas would later have to fight to win back by other means.

The Existential Crisis and Government Bailout (2012–2013)

The earthquake recovery was real. But it also hid something more dangerous: Renesas had gotten the lights back on, yet the business underneath was still broken. Operationally restored. Strategically weakened. And now trapped in an industry that doesn’t hand out second chances.

The Company in Free Fall

Renesas was barely a year removed from stitching together the merger—and had just taken a big swing in mobile—when 2011 hit with a one-two punch: the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, plus flooding in Thailand. The company survived the immediate chaos. Then it had to face what the chaos revealed.

In 2012, Renesas launched a sweeping restructuring across its global organization—manufacturing, sales, everything—spanning roughly 20 countries. The goal was blunt: rebuild the company into something that could actually generate profit.

But the numbers were ugly. For the year ended March 31, 2012, Renesas posted a net loss of 62.6 billion yen. And the broader pattern was worse: in the first three years after Renesas Electronics was formed, there was more or less no profit in the business at all.

By the fiscal year ending March 31, 2013, the company was forecasting a loss on the order of 150 billion yen, on revenue of about 880 billion yen. It was also preparing for drastic measures—loan deals secured in early October were meant to fund a planned reorganization that included large layoffs, retreats from manufacturing and certain markets, and potentially the sale or closure of as many as half of its domestic manufacturing sites. The plan contemplated as many as 12,000 job cuts—around 30% of the workforce.

This wasn’t just cyclical pain. Renesas was being squeezed from every direction at once: stronger global competitors, customers who had permanently diversified away after the quake, and a post-merger organization that still hadn’t fully fused into a single company. The losses weren’t just bad. They were unsustainable.

Enter INCJ: The Government Rescue

At that point, the story stops being a normal corporate turnaround and starts looking like industrial policy.

The Innovation Network Corporation of Japan, or INCJ—a taxpayer-funded fund established in 2009 to promote new industries and take on long-term risk—stepped in to lead a bailout. One catalyst was the threat of a takeover attempt by U.S. private equity firm KKR & Co. Japanese policymakers feared Renesas’s technology—and its role in the domestic auto supply chain—could end up in foreign hands.

This wasn’t framed as charity. It was framed as national interest. Renesas supplied critical components to Japan’s automotive ecosystem, and the government wasn’t eager to watch that capability move under private equity control.

The proposed package was massive: INCJ planned to invest 150 billion yen in exchange for roughly a two-thirds stake, while a group of about 10 companies would invest an additional 50 billion yen.

Those companies weren’t random. They included major customers and industrial pillars—Toyota Motor, Nissan Motor, Denso, Keihin, Panasonic, Nikon, Yaskawa Electric, and Canon. Their participation did two things at once: it signaled confidence that Renesas was still worth saving, and it ensured those customers had skin in the game.

Renesas, for its part, said it would direct 60 billion yen of the support toward R&D and capital spending tied to its core microcontroller business—essentially, protecting the part of the company that still had a defensible moat.

The deal culminated on September 30, 2013, when Renesas issued shares through a third-party allotment to INCJ and the other investors. INCJ’s ownership ratio rose to 69.15%. Renesas wasn’t just rescued. It was, in effect, nationalized.

Enter Hidetoshi Shibata: The Turnaround Architect

Money bought time. But time only matters if you use it well—and INCJ didn’t just bring capital. It brought a new operating philosophy, and a new kind of executive.

In November 2013, Hidetoshi Shibata joined Renesas as Executive Vice President and CFO. He served on the board from November 2013 to May 2016, and later returned to the board in March 2018.

Shibata wasn’t a traditional semiconductor lifer. Before INCJ, he had served as a Managing Director there, playing a key role in the restructuring and investment effort that revitalized Renesas. And before that, his résumé zig-zagged in a way that almost sounds like a character outline: Central Japan Railway, where he helped lead a large-scale re-engineering project—and even obtained a license to drive Shinkansen bullet trains—then private equity, then Merrill Lynch Japan.

His career path included Central Japan Railway (1995–1999), MKS Partners / Schroder Ventures KK (2001–2007), Merrill Lynch Japan Securities (2007–2009), and INCJ (2009–2013). He earned an engineering degree from the University of Tokyo and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

From Shinkansen to Wall Street to government turnaround fund to a collapsing chipmaker—unusual, yes. But it meant he could speak both languages Renesas desperately needed: operational discipline and financial reality.

When he arrived, Renesas was in crisis. And as EVP, board member, and CFO, he would be one of the leaders driving the structural reform—personnel cost reductions, reorganizing production sites, and forcing the company to make decisions it had spent years avoiding.

The Path to Profitability

The restructuring that followed wasn’t subtle. Renesas cut more than 7,000 jobs in a single year and committed to selling or shutting eight of its 18 Japanese plants within three years.

Then, in 2014, something happened that hadn’t happened before: Renesas recorded its first-ever profit.

That same year, the company made another hard call and withdrew from the 4G wireless business, leading to the consolidation of Renesas Mobile Communication. Soon after, it sold its display driver unit to Synaptics.

But the turnaround wasn’t just about cost. It was about focus. Renesas began exiting businesses where it couldn’t win and doubling down on the places where it still had an edge—especially automotive and industrial microcontrollers, where deep relationships and engineering credibility still mattered.

By 2016, Renesas had stabilized. The bleeding had stopped. But stability wasn’t the endpoint. The company needed growth—and organic growth in its core markets was hard, slow, and brutally competitive.

So Shibata and his team prepared to do something radically different: stop trying to build their way out, and start buying their way forward.

The Acquisition Machine: Shibata's Strategic Masterstroke (2016–2024)

By 2016, Renesas had done the hard, unglamorous work: stabilize the patient, stop the bleeding, and get back to profitability. The next question was harder.

How do you grow in semiconductors when your core markets are competitive, your customers want complete systems, and the gaps in your portfolio would take years to build from scratch?

Renesas’s answer was to stop thinking like a traditional Japanese IDM and start acting like a modern platform company. If it couldn’t build the missing pieces fast enough—analog, power, connectivity, software—it would buy them. And then it would stitch them into a single story customers could actually use.

From 2016 onward, Renesas launched one of the most ambitious acquisition campaigns in the industry, aimed squarely at becoming a global embedded solution provider, not just a microcontroller vendor.

Intersil (2017): $3.2 Billion

The first major move was Intersil.

Renesas agreed to acquire Intersil for $22.50 per share in cash, valuing the company at about $3.2 billion. Intersil, based in San Jose, specialized in power management and precision analog—exactly the categories Renesas needed to sit alongside its microcontrollers and SoCs.

The deal, which closed in February 2017, did more than add products. It brought Renesas into the heart of U.S. analog engineering, with talent and customer relationships that would have been slow to develop organically.

And it set the pattern: buy category-leading building blocks, then turn them into “solutions” customers can adopt quickly.

IDT (2019): $6.7 Billion

Two years later, Renesas went bigger.

It agreed to acquire Integrated Device Technology (IDT) for roughly $6.7 billion, at $49.00 per share. IDT expanded Renesas’s reach into analog mixed-signal chips for data sensing, storage, and interconnect—components that sit behind the growth of data centers and communications infrastructure, and that help diversify the business beyond pure automotive and industrial.

The acquisition was completed in March 2019.

But the most important impact wasn’t just the product roadmap. It was internal.

As one Renesas leader put it, bringing in Intersil and IDT “opened the eyes” of colleagues who had spent their entire careers inside Renesas. Integrating American companies forced Renesas to adopt simpler, industry-standard practices in areas like IT systems and business processes—because without that, every new acquisition would devolve into slow, case-by-case negotiations over how the company should operate.

In other words: if Renesas wanted to keep buying, it had to become a company that could absorb what it bought.

Dialog Semiconductor (2021): €4.9 Billion

Then came Dialog.

Renesas and Dialog Semiconductor reached agreement on a recommended all-cash acquisition of Dialog’s entire share capital, valuing it at about €4.9 billion (roughly $5.9 billion). Dialog, headquartered in the UK, was known for low-power mixed-signal chips and connectivity—Bluetooth and Wi‑Fi especially—critical ingredients for IoT and battery-powered embedded devices.

Renesas framed Dialog as the next step in turning its portfolio into a complete embedded offering: low-power mixed signal, connectivity, flash memory, battery and power management, and configurable mixed-signal solutions—plus a broader global go-to-market footprint.

And out of the Renesas–Dialog integration came one of the company’s signature commercial ideas: “Winning Combinations.” More than 35 pre-validated bundles of “Embedded Computing + Analog + Power + Connectivity,” positioned as ready-to-implement designs that reduce integration risk and speed customers to market.

Altium (2024): The Software Play

In 2024, Renesas made its most strategically ambitious move—and it wasn’t a semiconductor company at all.

Renesas completed the acquisition of Altium Limited, a global leader in electronics design systems. The definitive agreement was announced on February 15, 2024. Under the terms of the Scheme, Renesas Electronics NSW Pty Ltd, an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Renesas, acquired all outstanding shares of Altium for A$68.50 in cash per share, for a total equity value of approximately A$9.1 billion (about 887.9 billion yen).

Altium makes PCB design software—the tools engineers use to design the circuit boards that chips like Renesas’s ultimately live on. Founded in 1985 in Australia, Altium grew into one of the most widely used names in PCB software globally.

Renesas disclosed that Altium brought in about $263 million in revenue, with a 36.5% EBITDA margin and 77% recurring revenue.

The strategic intent was clear: this wasn’t about filling a chip gap. It was about moving upstream into the design workflow—creating a system design and lifecycle management platform that could integrate design data, standardize processes, and improve component lifecycle management, enabling faster, more seamless digital iteration.

Altium CEO Aram Mirkazemi took on the role of Senior Vice President and Head of Renesas’ Software & Digitalization, while concurrently serving as CEO of Altium.

The "Winning Combinations" Strategy

Across these deals, Renesas kept reinforcing a single go-to-market idea: make it easier for customers to build complete systems with Renesas parts.

“Winning Combinations” were the proof point—pre-tested, pre-validated product bundles that combined microcontrollers, analog, power, and connectivity into designs engineers could implement with less integration pain.

That matters because automotive and industrial systems aren’t getting simpler. They’re getting more software-defined, more sensor-heavy, and more electrically complex. Engineers don’t just want a great standalone MCU. They want a design that works, ships, and passes qualification.

By packaging proven combinations, Renesas reduced customer risk, accelerated time-to-market, and made its portfolio stickier.

Additional Acquisitions

Alongside the headline deals, Renesas also made a string of smaller acquisitions designed to fill specific technology gaps.

It continued its expansion through 2023 and 2024 with acquisitions including Panthronics and gallium nitride chipmaker Transphorm, along with Altium.

Other acquisitions included Celeno Communications (Wi‑Fi technology), Reality AI (machine learning for embedded systems), and Steradian Semiconductors (radar sensors for automotive applications). Each one added a focused capability—another piece of the broader push to sell integrated embedded solutions, not isolated components.

Shibata's Leadership and the Exit of INCJ (2019–2023)

From CFO to CEO

By the time Renesas’s acquisition engine was spinning up, the company’s internal power structure had already shifted.

Hidetoshi Shibata, who had joined in November 2013 as Executive Vice President and CFO, became CEO in July 2019. The transition was formal and sudden: following the resignation of then-CEO Bunsei Kure effective June 30, 2019, Renesas named Shibata Representative Director, President and CEO, effective July 1.

It was a clean handoff at the top, but the subtext was clear. Renesas was no longer in emergency triage mode. It was moving into its next phase—growth—and Shibata was the person most associated with the playbook that had gotten it there.

After helping drive the structural reforms that stabilized the business, Shibata was instrumental in leading the acquisitions of the U.S.-based Intersil and Integrated Device Technology—two deals that didn’t just add revenue, but filled critical capability gaps for the company’s future.

And his ambitions didn’t stop with those integrations. Five years into his tenure as chief executive officer, the former Merrill Lynch banker pointed to growth opportunities like new business in India and AI-enabling microcontrollers, with an eye toward doubling annual revenue to a record $20 billion by the end of the decade.

The INCJ Exit: Mission Accomplished

Then came the final step in Renesas’s transformation: the government stepped away.

INCJ—the state-backed fund that had rescued Renesas in 2013—sold all of its remaining shares. The exit marked the end of a decade-long relationship that began with a bailout and ended with a functioning, profitable, globally competitive company.

“On the momentous 10-year mark of INCJ’s investment, we have achieved the milestone of INCJ selling all of our shares,” Shibata said. “We appreciate INCJ’s investment and support to date. INCJ greatly contributed to laying our foundation for growth. We are committed to accelerate our next phase of growth, aspiring to become the leader in embedded semiconductor solutions.”

INCJ had been reducing its stake in stages from 2017 onward, shrinking its ownership to 7.38% as of November 13, 2023. After the final sale, its ownership fell to 0.00%.

Financially, it was a win for the fund. INCJ’s gains largely came from acquiring about 70% of Renesas in 2013, then steadily selling down its position. In November, it offloaded almost all of its remaining 6.65% stake for $1.8 billion.

Strategically, it was even more meaningful. The INCJ investment became one of the clearest examples of a government-backed turnaround in modern Japanese corporate history: patient capital that gave Renesas room to restructure, then a gradual exit that brought in international institutional investors and returned Renesas to the public markets as a “normal” company again.

Cutting Ties with the Past

If INCJ’s exit ended the bailout era, the next wave of share sales ended something even older: Renesas’s founding identity.

In January 2024, NEC and Hitachi sold all of their remaining holdings in Renesas. In February 2024, Mitsubishi Electric—one of the original parent companies—sold the rest of its stake as well, ending the capital relationship with all three founders.

The timing wasn’t accidental. Hitachi and NEC were selling into a strong market, part of a broader trend of Japanese companies unwinding long-held cross-shareholdings.

Hitachi expected to receive $896 million for its Renesas stake, and NEC expected to receive $1.2 billion.

But the symbolism mattered more than the proceeds. With the founding shareholders fully out, Renesas was no longer a stitched-together chip division carried on the balance sheets of Japanese conglomerates. It was an independent company with a global shareholder base—and, for the first time in its life, a strategy that wasn’t defined by where it came from.

The Automotive Semiconductor Battleground

For all of Renesas’s reinvention—bailout to buyout machine—its most important arena is still the same one that nearly broke it in 2011: automotive.

Cars are where Renesas built its reputation, where qualification cycles are long and sticky, and where “good enough” usually isn’t. It’s also where the competitive knives are sharpest, because the prize is enormous: as vehicles electrify and become more software-defined, semiconductors move from supporting cast to headline act.

The Competitive Landscape

The automotive chip market is concentrated, and the leaders are entrenched. IDC reported that the top five vendors captured over half the market in 2023. Infineon led with 13.9% share, followed by NXP at 10.8% and STMicroelectronics at 10.4%. Texas Instruments and Renesas also held meaningful positions, at 8.6% and 6.8%, respectively.

That ranking matters because it hints at how the market is segmented by “who owns what” inside the vehicle. Infineon has been strongest in chassis and safety applications. NXP has leaned into gateway and in-vehicle networking. Renesas has been particularly associated with cockpit domains. And ST has focused more on body applications.

The other key shift is in microcontrollers themselves—the category Renesas has historically dominated. With strong growth in its AURIX and related product lines, Infineon’s automotive MCU share rose rapidly. In 2022, it trailed only Renesas. In 2023, it surpassed Renesas for the first time to take the top spot.

So even before you add new entrants, the incumbents are already taking share from one another, and the old hierarchy isn’t guaranteed.

The Automotive Semiconductor Boom

Here’s the structural tailwind: vehicle volumes aren’t growing much, but silicon per vehicle is.

Between 2024 and 2030, global automotive growth is expected to be modest—around 2% CAGR. But the automotive semiconductor market is forecast to grow far faster, expanding from $68 billion in 2024 to $132 billion in 2030.

The simplest way to feel that change is controller count. A battery-electric vehicle can require more than 300 controllers, compared with roughly 70 in an internal combustion vehicle. That alone implies a very different world for microcontrollers and the surrounding ecosystem of power, sensors, networking, and safety components.

Electrification drives demand for power electronics and battery management. ADAS adds cameras, radar, and heavier processing. Connectivity features pull in networking and cybersecurity. The vehicle is turning into a rolling electronics platform, and every new feature tends to add chips, not subtract them.

Rising Threats from China

Then there’s the wildcard: China.

A domestic content mandate targeting 25% by 2025 is already reshaping buying behavior and supply chains. Analysts point to a growing roster of local challengers: Horizon Robotics, SiEngine, and Black Sesame aiming at cockpit and ADAS chips; BYD Semiconductor and StarPower expanding in SiC and IGBT. Chinese OEMs are also pushing vertical integration. Nio, for example, designed its own 1,000 TOPS domain controller on TSMC’s 5nm node.

On the manufacturing side, SMIC is building four 12-inch fabs for 28/40nm automotive production—nodes that are highly relevant for many automotive MCUs and other long-life chips.

This is why China represents both the biggest threat and the biggest uncertainty for Renesas and its peers. If Chinese automakers increasingly design their own silicon or standardize on domestic suppliers, the addressable market for global vendors shrinks—at least in the world’s most dynamic auto market.

Renesas's Defensive Position

Renesas isn’t walking into this fight empty-handed.

In Japan, companies like Renesas, Rohm, and Denso have remained strong in legacy MCUs, sensors, and SiC, rebuilding momentum after the pandemic-era shortage. As Pierrick Boulay of Yole Group put it: “Renesas is regaining market, while Rohm and Denso are growing in SiC MOSFETs for EV inverters.”

Renesas’s edge has long been relationships and reliability—deep ties with Japanese automakers, a broad MCU portfolio, and a strong position in cockpit and infotainment domains. The acquisition campaign layered in the pieces modern automakers increasingly want alongside the MCU: analog, connectivity, and power management. That matters because the battle isn’t just for one chip socket anymore. It’s for more of the bill of materials—and for the system-level design wins that come with offering more complete solutions.

But the pressure is real and multi-front. Infineon is winning share at the top of the automotive stack. NXP is formidable in networking and gateways. And in China, the competitive landscape is shifting under everyone’s feet—driven not just by technology, but by policy, capacity, and increasingly ambitious OEMs.

Today's Renesas: Strategy, Operations, and Future Vision

Current Financial Position

By the end of 2024, Renesas looked nothing like the company that needed a state rescue a decade earlier. But it also wasn’t immune to the realities of a cyclical industry.

For the year ended December 31, 2024, Renesas reported consolidated non-GAAP revenue of 1,348.5 billion yen, down 8.2% year over year. The main driver was weaker demand in Industrial, Infrastructure, and IoT. Automotive revenue moved the other direction—helped in part by yen depreciation—which mattered because it reinforced what the company has been betting on: cars as the steadiest growth engine in its portfolio.

Profitability, though, told the bigger story. Renesas delivered a gross profit margin of 56.1% and an operating profit margin of 29.5% in 2024—numbers that would have sounded like science fiction back in the restructuring years. The mix shift toward higher-value solutions, plus tighter operational discipline, has made Renesas structurally different from the old “merged divisions” it started as.

The takeaway from the 2024 results is a familiar semiconductor pattern: industrial demand softened, automotive held up. But underneath that cycle is the enduring consequence of the turnaround—Renesas built a business that can generate substantial profit even when one of its major end markets cools.

Market Recognition

The public markets noticed.

In December 2022, Renesas received the “Outstanding Asia-Pacific Semiconductor Company Award” from the Global Semiconductor Alliance. Then, in April 2023, it was added to the Nikkei 225—alongside Oriental Land and Japan Airlines—driven by high liquidity.

Renesas described 2023 as a year when its presence in the stock market kept expanding. Its shares were selected as a Nikkei 225 constituent, and its market capitalization nearly doubled from the beginning of 2023.

Inclusion in the Nikkei 225 wasn’t just another line in an investor deck. It was a symbolic marker that Renesas had crossed a threshold: from a company defined by bailout math and restructuring plans into one of Japan’s core public-market names again.

The $100 Billion Vision

Shibata’s next target is even more audacious than the turnaround: make Renesas bigger, more global, and more essential to the next generation of embedded computing.

Five years into his CEO tenure, he pointed to two growth vectors in particular—new business in India and AI-enabling microcontrollers—as paths to doubling annual revenue to $20 billion by the end of the decade. In parallel, he has talked about tripling the company’s valuation to around ¥16 trillion to ¥17 trillion, roughly the neighborhood of a $100 billion market cap by 2030.

That ambition implies a continuation of the same playbook that got Renesas here: some organic growth, more portfolio expansion, and deeper penetration into applications where customers want complete, validated solutions—not just a standalone chip. It also implies geographic expansion beyond Renesas’s historical strongholds, with India highlighted as a major opportunity.

And notably, Japan is back in the semiconductor game as a policymaker. In less than three years, Tokyo committed to investing ¥4 trillion in semiconductors and other advanced tech, including as much as ¥15.9 billion to cover a third of the cost to expand capacity at three Renesas plants.

The support looks different now. It’s not an emergency rescue designed to keep the lights on. It’s incentive-driven industrial policy aimed at capacity, resilience, and self-sufficiency—and that creates real tailwinds for a domestic champion like Renesas.

Bull Case, Bear Case, and Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

Renesas came out of its near-death years looking like a different company. The bull case isn’t one magic product. It’s a set of reinforcing strengths that, together, make the turnaround feel durable.

Automotive semiconductor tailwinds look structural, not cyclical. Even if global vehicle production only crawls forward, the amount of silicon inside each car keeps climbing. Electrification adds power management and control. ADAS adds sensors and processing. Connectivity adds more compute and more networking. Renesas sits right in the middle of that complexity, with a portfolio that can show up in more places in the vehicle—and capture more revenue per vehicle—than a pure-play microcontroller vendor ever could.

The acquisition strategy has actually worked. Serial acquirers often trip over integration: overlapping product lines, incompatible systems, talent loss, culture clash, and “synergies” that never show up. Renesas has, so far, done the hard part well—absorbing Intersil, IDT, and Dialog, and turning that expanded catalog into a coherent go-to-market story through its “Winning Combinations” approach. The point isn’t just that Renesas sells more parts; it’s that it can sell customers pre-validated combinations that reduce integration risk and speed time-to-market.

Japanese automaker relationships still provide a defensible base. Toyota, Honda, and Nissan remain global-scale customers. Renesas’s long history and deep qualification footprint with these OEMs gives it a kind of stability that’s hard to replicate quickly—especially in automotive, where trust, reliability, and long program cycles matter as much as specs.

Altium adds strategic optionality. This is the most “non-Renesas” acquisition it has made, which is exactly why it’s interesting. Moving into design software offers new ways to monetize the ecosystem and, potentially, to make Renesas more “default” in the design flow. If that stickiness works, it can widen the moat in a way that’s difficult for a chip-only competitor to match.

The Bear Case

The risks are real, and they’re not the kind you can hand-wave away with a few good quarters.

Chinese competition is getting stronger fast. Players like BYD Semiconductor and Horizon Robotics are building serious automotive chip capabilities, backed by policy and domestic demand. If Chinese automakers increasingly insource key silicon or standardize on local partners, Renesas could see its growth opportunity in the world’s largest auto market narrow—especially in segments where “good enough” is acceptable and scale matters most.

Market share pressure from Europe isn’t theoretical anymore. Infineon has already overtaken Renesas in automotive MCU share and continues to invest aggressively. NXP and STMicroelectronics are formidable in their own strongholds, and all three are chasing the same design wins. In a market where qualification is slow and sockets are sticky, losing share can take years to win back.

Acquisition-driven growth has natural limits. Each deal gets harder: larger organizations, more systems to unify, more culture to integrate, and less tolerance for distraction. Altium is also a meaningful step into software—an area outside Renesas’s historical center of gravity. If the company can’t translate its M&A discipline into a software context, the integration risk rises.

And, of course, semiconductor cyclicality doesn’t disappear. Automotive can be steadier than consumer electronics, but Renesas still has significant exposure to Industrial, Infrastructure, and IoT—markets that behave like classic semis cycles. The 2024 revenue decline was a reminder: even a well-run Renesas can’t opt out of demand swings.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier power is moderate. Renesas still runs its own fabrication footprint, which provides some insulation, and it also relies on external relationships—such as long-term supply agreements like its arrangement with Wolfspeed for SiC wafers. But like every chip company, it remains exposed to equipment suppliers, constrained materials, and the broader realities of manufacturing supply chains.

Buyer power is moderate to high. Automotive OEMs and top-tier suppliers are sophisticated buyers with scale and leverage. And since the quake, the industry has leaned hard into multi-sourcing. That structural move toward redundancy weakens any one supplier’s negotiating position, including Renesas’s.

The threat of substitutes is moderate. This doesn’t just mean “a competing chip.” It can also mean a different architecture, a different integration approach, or a customer deciding to design the function in-house. As OEMs and big tier-ones experiment more with vertical integration, substitution risk rises—particularly in high-volume applications.

The threat of new entrants is low to moderate. Automotive semiconductors are difficult: heavy R&D, strict reliability requirements, long qualification cycles, and relationship-driven design-ins. But China is the exception that proves the rule. With government support and a vast domestic market, new entrants can emerge faster than traditional industry logic would predict.

Competitive rivalry is high. Infineon, NXP, STMicroelectronics, Texas Instruments, and a growing set of Chinese competitors are all targeting the same growth pools—automotive electrification, ADAS, and industrial automation—and they’re willing to invest aggressively to win.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale economies exist, though they’re not the kind foundry-scale advantage that reshapes an industry. Renesas benefits from manufacturing scale relative to smaller peers, and its acquisitions helped broaden scale in analog and mixed-signal categories.

Network effects are modest. “Winning Combinations” can create a kind of ecosystem pull—more reference designs, more reuse, more familiarity across engineering teams—but it’s not a platform network effect in the consumer-internet sense.

Counter-positioning is limited. Renesas largely plays the same broad IDM game as key competitors like Infineon and NXP, rather than attacking from a structurally different model.

Switching costs are moderate to high. Automotive qualification and long design cycles create real friction. But customers have become more disciplined about maintaining multiple qualified suppliers, which caps how high those switching costs can go in practice.

Branding is limited, in the traditional sense. These are components, not consumer products. The “brand” is really a reputation for reliability, roadmap credibility, and engineering support.

Cornered resource still matters, but it’s not permanent. Renesas’s deep relationships with Japanese automakers and its accumulated automotive IP are valuable. The question is whether those advantages erode as competitors deepen their own relationships and as the center of gravity in automotive shifts globally.

Process power is one of the strongest arguments for Renesas. The company has shown it can execute large acquisitions and integrate them into a coherent strategy. That capability—repeated, institutionalized M&A integration—can become a durable advantage because it’s hard to copy quickly, even for well-funded rivals.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you’re tracking whether Renesas’s reinvention continues to work, a few indicators matter more than the rest:

-

Automotive revenue growth rate — This is the clearest read on whether Renesas is capturing the structural rise in semiconductor content per vehicle. The key is not just growth, but growth that outpaces underlying vehicle production.

-

Non-GAAP gross margin — Margins reveal whether Renesas is improving mix, holding pricing power, and integrating acquisitions effectively. The mid-50% range Renesas achieved is a meaningful signal of how different the business looks versus the pre-turnaround era.

-

Design win announcements and backlog — Automotive is a long game. It can take years for a design win to turn into volume production, so design win momentum is one of the best leading indicators of future revenue and share trajectory.

Conclusion: The Phoenix Narrative

The Renesas story resists a single, clean label. It’s a cautionary tale about the limits of defensive mergers. It’s proof that a government-enabled rescue can create the breathing room for a real turnaround. And it’s still unfolding as a case study in acquisition-driven reinvention.

A useful contrast sits right next to it in Japanese chip history. On February 27, 2012, Elpida filed for bankruptcy. With liabilities of 448 billion yen (about $5.5 billion), it was Japan’s largest bankruptcy since Japan Airlines collapsed in 2010.

Elpida—the DRAM business that Hitachi, NEC, and Mitsubishi Electric had carved out years earlier—followed one path: the commodity-memory grind, collapse, and eventual absorption by Micron. Renesas, built from the non-DRAM remnants of those same corporate parents, followed a different path: state-backed survival, ruthless restructuring, and then a deliberate strategy to buy the capabilities it couldn’t afford to build slowly.

The Renesas that emerged from the INCJ era hardly resembles the merger-of-necessity that entered it. Today’s company is meaningfully more global and more diversified, with U.S., U.K., and Australian acquisitions layered onto its Japanese base. And the Altium deal signals something even bigger than portfolio breadth: an ambition to move upstream into the software and design workflow, not just ship the chips that go on the board.

But the phoenix story isn’t a victory lap. The uncertainties are real. Can Renesas defend itself as Chinese competitors get stronger in the world’s most important auto market? Will Altium produce the strategic leverage its price implies? And can a company born from Japanese conglomerate culture consistently operate as a fast, globally distributed organization with major American and European footprints?

Zoom out and the backdrop matters. Japan’s semiconductor sector is far smaller than it was in the 1980s, but it still sits in a critical position in the global supply chain—especially in the equipment and materials that make modern chip manufacturing possible.

The country’s remaining strongholds are telling: semiconductor manufacturing equipment (Tokyo Electron, SCREEN, Advantest), wafers (Shin-Etsu, SUMCO), NAND flash (Kioxia), and power devices (Renesas, Rohm).

In that landscape, Renesas has become one of Japan’s clearest semiconductor success stories—arguably the most consequential turnaround of the modern era. Whether it keeps flying will come down, as always, to execution: competing in a tougher market, integrating what it buys, and navigating a world where geopolitics increasingly shapes supply chains.

For anyone who studies corporate transformation, the lessons are unusually durable: mergers don’t create value by themselves; government intervention can enable rather than distort when it’s structured for discipline and exit; culture has to change alongside strategy; and sometimes the fastest route to growth is buying what you can’t build.

And yes—the former bullet train engineer turned investment banker turned semiconductor CEO has already authored one of the more remarkable chapters in recent Japanese business history. The next ones, aimed at roughly $20 billion in revenue and a $100 billion valuation, are still unwritten.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music