Makita Corporation: The Quiet Giant That Invented the Cordless Revolution

I. Introduction: The Teal Blue Mystery

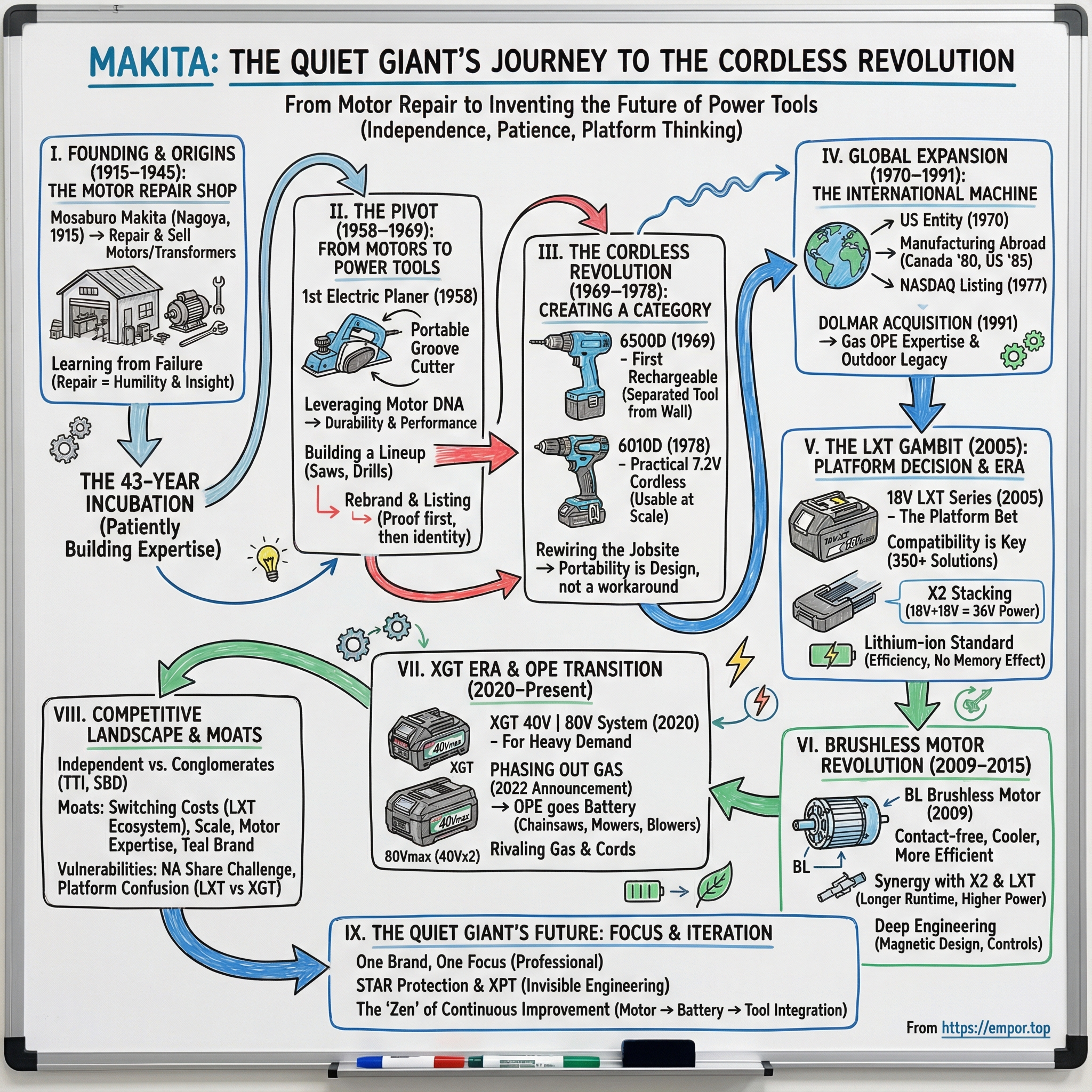

There’s a particular shade of teal that tradespeople everywhere recognize instantly. Not DeWalt’s jobsite yellow. Not Milwaukee’s in-your-face red. This one is quieter. More clinical. The color says: precise Japanese engineering, batteries that play nicely across tools, and a brand that somehow feels both everywhere on the jobsite and oddly absent from the investing conversation.

Makita Corporation began in 1915, when Mosaburo Makita opened a business in Nagoya, Japan selling and repairing electric motors. A century later, Makita is still an outlier in its industry: one of the few largest tool companies that sells only under its own name, with a focus squarely on professional-grade power tools.

That independence matters. In a world of consolidating giants—where Stanley Black & Decker owns DeWalt, and Techtronic Industries owns Milwaukee Tool—Makita has remained stubbornly standalone. No portfolio of sibling brands. No corporate parent. Just Makita.

Which brings us to the central mystery. How did a Japanese motor repair shop, founded as World War I began, become the company that helped invent the cordless tool revolution? And why did it have the discipline to wait decades—forty-three years—before it even made its first power tool?

That’s the story we’re going to tell. Along the way we’ll hit the themes that define Makita’s strategy: platform thinking long before anyone used that phrase; the nerve it takes to bet an entire lineup on battery voltage; the tradeoffs of staying independent in a conglomerate era; and the massive shift now underway as outdoor power equipment moves from gas engines to batteries.

Today, Makita’s tools are sold in around 50 countries, and the company runs 10 manufacturing facilities across 8 nations, including one in the United States. With more than a century of motor engineering behind it—and decades of cordless experience—Makita keeps doing what it has always done: quietly iterating until the product feels inevitable.

By the end, you’ll see why some of the most consequential “platform” decisions of the last hundred years weren’t made in Silicon Valley boardrooms. They were made in Japanese factories, by engineers who understood that the electric motor—humble as it seems—might be one of the most important platform technologies of the twentieth century.

II. Founding & Origins: The Motor Repair Shop (1915–1945)

The year was 1915. Woodrow Wilson was in the White House. The Great War was ripping through Europe. Japan, meanwhile, was riding a wartime export boom. And in Nagoya—an industrial city with machinery humming and demand climbing—a 21-year-old named Mosaburo Makita placed a very specific bet: electricity was only going one direction.

On March 21, 1915, he opened a small shop in Nagoya selling and repairing electric equipment—especially motors. The business was called Makita Denski Seisakusho, and it looked nothing like the global tool giant it would become. It was modest, hands-on, and intensely practical.

To understand why this made sense, you have to picture Japan at the time. Electrification was spreading fast. Factories were moving away from steam and toward electric power. Homes and businesses were adding lighting and new equipment. But early electric machinery was finicky. When a motor failed, productivity stopped cold. The winners weren’t just the companies that sold hardware—they were the ones that could keep it running.

That’s where Mosaburo’s instincts were dead-on. He focused on repairing and selling lighting equipment, motors, and transformers, stepping into a growing market where reliability mattered as much as invention. He came from a timber-merchant family, which meant he understood the trades and the rhythms of working life. But he didn’t stay in the family lane. He leaned into electrical technology, effectively choosing the future over tradition.

The early team was tiny: Mosaburo, Jujiro Goto—a 17-year-old worker—and a recent elementary school graduate. Three people. Barely a company at all. And yet this was the foundation of everything Makita would later be known for: craftsmanship, durability, and a quiet obsession with what happens after a tool leaves the factory.

Because for years, Makita didn’t win by manufacturing shiny new products. It won by taking broken motors apart. Repair work forces humility. You see the weak points. You learn what fails first. You get a front-row seat to the gap between how something is supposed to work and how it actually behaves in the field. For a future power tool company, that’s not just useful—it’s a world-class education.

By the mid-1930s, the little repair business was doing something that sounds almost implausible: exporting. In 1935, Makita began exporting electric motors, and in the 1930s it exported generators to Russia. For a company that started on a workbench in Nagoya, this was an early signal that Mosaburo wasn’t building a local shop. He was building an industrial player.

In 1938, the business incorporated as Makita Electric Works, Ltd., another step toward scale and permanence.

Then history intervened. As World War II intensified, Nagoya became a target. In April 1945, Makita relocated its plant to Anjō City—smaller, less exposed, and about 30 kilometers away—to avoid air raids. It was a move made for survival, not efficiency. And it mattered: Anjō is still where Makita’s headquarters sit today.

Zoom out, and the most striking thing about 1915 to 1945 isn’t what Makita launched. It’s what it didn’t. For decades, it stayed in the motor world—repairing, selling, learning—without touching the category it would eventually define.

That long runway matters. Makita’s “incubation period” stretched from its founding in 1915 to its first power tool in 1958. Forty-three years. In modern business terms, that kind of patience feels almost alien. But in Makita’s story, it’s the point: the company didn’t rush to be early. It worked to be right.

And when you’ve spent decades living inside the electric motor—seeing how it fails, how it survives, and how it can be made better—eventually you start to realize something: the motor isn’t just a component. It’s a platform. Put it in the right form factor, and you can change how the world works.

III. The Pivot: From Motors to Power Tools (1958–1969)

Imagine running a company that has spent four decades doing one thing: repairing and building electric motors. It’s steady work. It kept you alive through war. It even got you into export markets. And then someone says, “What if we stop being the company behind the machine… and become the company people hold in their hands?”

That’s the leap Makita took in the late 1950s. And true to form, it didn’t start by chasing what was popular in the West. It started with what it understood—deeply—about craftsmanship and precision.

In 1958, Makita became the first company in Japan to manufacture and sell electric planers.

It’s an unintuitive choice if your mental model of power tools begins with drills and circular saws. But in Japan, woodworking had its own gravity. Traditional hand planes, called kanna, were central to the trade, and the standard for finish work was unforgiving. Makita’s first big power-tool bet wasn’t about flash. It was about accuracy, feel, and control—exactly the kind of product a motor company with repair-shop humility would build.

That same year, Makita developed a portable electric planer, and it worked—not just at home, but overseas. Exports to Australia, in particular, helped validate that this wasn’t a niche Japanese solution. It was a professional tool with global demand. That success became the catalyst for something bigger: Makita rebranded itself as a power tool company and took a listing on the stock exchange.

The sequencing matters. Makita didn’t rebrand first and hope the products caught up. It built something that proved itself in the market, then used that proof to change its identity and fund the next chapter.

Also in 1958, Makita released its second power tool: a portable groove cutter. There isn’t much documentation on it today, and images are scarce, but its role in the story is clear. Makita wasn’t dabbling. It was building a lineup, shifting its center of gravity from motors as components to motors as the heart of a tool ecosystem.

By 1962, circular saws and electric drills joined the catalog—the industry’s foundational categories. But the real advantage wasn’t the categories. It was what Makita brought into them.

Those 43 years of motor work weren’t just a prelude; they were the differentiator. Repairing motors teaches you what breaks first. Building generators teaches you power density, efficiency, and heat management. When Makita started making tools, it carried that hard-earned knowledge directly into durability and performance—the traits professionals actually pay for.

You can even see the lineage. The original planer is widely regarded as a forerunner to today’s familiar 3 ¼-inch format. Put a modern Makita planer next to that early design and the family resemblance is obvious: not just in shape, but in the priorities embedded in it—compactness, precision, and a bias toward the jobsite.

Post-war reconstruction only amplified the opportunity. Japan and the broader region were rebuilding fast, and demand for portable electric equipment surged. Makita’s leadership saw the opening: there was room on the shelf for tools built from top-tier materials, designed for people who used them all day—not occasionally on weekends.

And that became a defining choice. Makita didn’t position itself as a consumer brand trying to win on price or gimmicks. It aimed straight at professional credibility—a posture that would shape the company for decades.

This is what a great pivot looks like. It doesn’t discard the past. It weaponizes it. Makita didn’t stop being a motor company when it started making tools. It simply asked a bigger question:

What else can we power?

IV. The Cordless Revolution: Creating a Category (1969–1978)

April 1969. Neil Armstrong was a few months away from walking on the moon. And halfway around the world from that spectacle, Makita was about to change something far more everyday: how work happens when there isn’t an outlet nearby.

That month, Makita introduced the 6500D, widely recognized as the world’s first rechargeable power tool. It wasn’t “cordless” the way we picture it now. The drill was connected by a cable to a rechargeable battery pack. But that technical caveat is exactly what makes it such a big moment: Makita had separated the tool from the wall.

For the first time, portability wasn’t a workaround. It was the design.

Before this, job sites had to plan around electricity. Extension cords became part of the workflow. Generators, outlet access, and “how far can we reach?” shaped where people worked and what was practical. The 6500D hinted at a different future: the tool goes where the worker goes.

There’s an important nuance here. Black and Decker had released a battery-powered drill earlier—the C-600 in 1961—but it was built for specialized industrial and aerospace use, not the general tradesperson. Makita’s 6500D was the first rechargeable power tool broadly available to working professionals.

And yes, by today’s standards, it was rough. Heavy metal housings. Inefficient motors. Low-capacity batteries. It was more proof-of-concept than polished product. But it worked well enough to teach Makita what mattered, and what still needed to be solved.

Then Makita did what Makita always does: it iterated patiently.

After a full decade of design, testing, and investment in R&D, Makita introduced its first 7.2V cordless drill in 1978. Power and runtime improved. Charging got faster. Tool life got longer. In other words, the idea became usable at scale.

That 1978 tool was the 6010D, built around a rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery mounted in the handle. It shipped in a distinctive green molded plastic case and went on to become a familiar sight on work sites through the 1980s, joined by other cordless tools. Makita’s battery-powered screwdrivers became essential kit for many tradespeople. And for a time, “Makita” itself became a generic name for this kind of cordless tool.

That’s category creation. Not because the ads were clever, but because the product rewired the job.

Once a drill no longer needed the grid, everything downstream changed. Work could start before a building’s electrical system was even installed. Tasks moved to rooftops, scaffolding, tight framing, and anywhere an extension cord used to be a constraint. The gains were small in the moment—seconds here, minutes there—but compounding across countless tasks and job sites.

Makita didn’t just improve a tool. It helped move the entire industry from “powered” to truly portable. And from that point on, there was no going back.

V. Global Expansion: The International Machine (1970–1991)

By the early 1970s, Makita had done the rarest thing in tools: it hadn’t just made a good product, it had cracked open a new way of working. Now it faced a different kind of problem—one that isn’t solved by engineering alone.

How do you take a Japanese manufacturer global in an era before email, before cheap flights, and before “international expansion” came with a playbook?

Makita’s answer was to build an international machine—fast.

In 1970, Makita opened the Okazaki Plant, a modern mass-production facility that could support real scale. That same year, it planted the most ambitious flag possible: the United States. Makita established Makita U.S.A. in New York City, then built out sales and service bases in major hubs like Chicago and Los Angeles.

This was not the easy route. The U.S. was the home turf of electric power tools, with fierce competition from entrenched American manufacturers. But that’s exactly why the move made sense. If Makita could earn credibility in the biggest, most competitive tool market in the world, it could earn it anywhere.

Then the expansion accelerated. Through the 1970s, Makita widened its footprint across major Western markets—setting up operations in places like France, the UK, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. The cordless momentum mattered here: success with early rechargeable tools didn’t just sell drills; it created demand for the rest of the lineup, and it justified building local presence instead of relying on distant exports.

The timeline reads like a company trying to get everywhere before the window closes. In 1971, Makita established Makita France S.A. In 1972, Makita Electric (U.K.) Ltd. In 1973, Makita (Australia) Pty. Ltd., and Makita Power Tools Canada Ltd. That same year, Makita listed on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange using Continental Depositary Receipts—another signal that this wasn’t “exporting.” This was committing.

By 1977, Makita stock was trading on NASDAQ. For a Japanese power tool maker, that was a statement: we’re here, we’re serious, and we want American investors along for the ride.

The company’s next move was even more consequential: it started making tools abroad. In 1980, Makita opened its first overseas factory in Canada. In 1985, it followed with U.S. manufacturing in Buford, Georgia. Proximity to customers was one benefit, but the bigger logic was resilience. The 1980s brought trade tension and political pressure around Japanese exports into the U.S. Building in North America helped Makita keep growing without being trapped by the geopolitics of the moment.

While competitors fought for shelf space and jobsite mindshare, Makita also kept doing the quieter thing it had always done: improving how products get made. In the 1980s, it pushed computer-controlled automation to raise productivity and quality—investments that rarely make headlines, but show up years later as cost structure, consistency, and reliability.

Then, in 1991, Makita made a move that looked surprising if you only thought of it as an electric tool company. It acquired Sachs Dolmar GmbH, a German chain saw manufacturer, later renamed Dolmar GmbH in September 1991.

Dolmar wasn’t a random bolt-on. It was a historic name in outdoor power equipment, with roots going back to Germany in 1927 and a reputation tied to professional-grade gasoline chainsaws. So why buy into gas, when Makita’s identity was increasingly electric?

Because Makita wasn’t just building drills and saws anymore. It was building a professional tool company with ambition to own the entire jobsite—and the outdoors around it. The Dolmar acquisition strengthened Makita’s outdoor power equipment lineup and gave it a serious legacy position in the 2-stroke world.

Decades later, that footprint still mattered. On August 20, 2024, Makita’s Germany plant reached cumulative production of 10 million units—an output line that traces directly back to the 1991 acquisition.

1991 also brought a symbolic shift. Makita changed its name from Makita Electric Works to Makita Corporation and introduced a corporate identity program. The rebrand wasn’t cosmetic. It was a declaration that the company had outgrown its origin story. It wasn’t just motors. It wasn’t even just electric tools. It was now a broad professional equipment platform.

Makita’s European presence continued to deepen as well. It had come to the UK in 1972, manufacturing tools from Telford. Later, in 1995, Makita established its Milton Keynes headquarters as a European base.

By the early 1990s, Makita had transformed from a Japanese exporter into a multinational with real operations in the markets that mattered most. The teal blue tools were no longer just shipping from Japan—they were increasingly built closer to the customer, in factories spread across countries including Brazil, China, Japan, Mexico, Romania, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Canada, and the United States.

And that global footprint set the stage for what came next. Because once you’re everywhere, and cordless is the future, the fight stops being about any single tool.

It becomes a war over the battery platform.

VI. The LXT Gambit: The Platform Decision That Defined an Era (2005)

Every great business story has a moment where a seemingly technical decision becomes strategic destiny. For Apple, it was the App Store. For Amazon, it was AWS. For Makita, it was a choice about batteries—and it landed in 2005.

By then, cordless tools weren’t new. The industry had already spent decades on nickel-cadmium (NiCd) and nickel-metal hydride (NiMH): batteries that were heavy, gradually lost capacity, and came with quirks like the dreaded “memory effect” that could quietly sabotage performance over time. Cordless existed, but it still felt like a compromise.

Lithium-ion promised to flip that tradeoff. Lighter. More energy-dense. Faster charging. No memory effect. But it also came with a catch: lithium-ion wasn’t a drop-in upgrade. It demanded new electronics, new safety systems, and new manufacturing discipline. In other words, adopting it meant rebuilding the foundation under your entire cordless lineup.

And that forced the strategic question every tool company had to answer: what voltage becomes your standard?

Makita’s answer was 18V—and it didn’t dabble. On October 3, 2005, Makita launched its LXT Series featuring 18V lithium-ion battery technology, aimed squarely at professional users. Makita was the first to introduce 18V lithium-ion cordless tools, and that decision became one of the most defining in the company’s history.

The bet paid off. Today, the LXT System has grown into the world’s largest compatible 18V slide-style battery platform, with more than 350 solutions.

But the real genius wasn’t just picking 18V. It was what Makita did next: it treated 18V as a platform, not a product cycle.

From the start, the promise was compatibility. LXT batteries would work across LXT tools, so each new purchase made the rest of your kit more valuable. The tradesperson logic is simple: the tool is the fun part, but the batteries are the investment. Once you’ve built a stack of batteries and chargers, switching brands isn’t just expensive—it’s disruptive.

Makita leaned into that reality. The company had been thinking in platforms long before “platform strategy” became business-school vocabulary. Back in 1987, Makita’s cordless lineup counted a couple dozen tools. By the LXT era, that ecosystem exploded into the hundreds, tied together by a shared battery standard.

That’s platform economics in its purest form. Every battery increases the value of every tool you already own. Every tool makes your battery investment feel smarter. And with each purchase, the switching costs quietly compound.

Then came the next strategic problem: power-hungry applications. If you stick to one battery platform, what do you do when competitors start pushing higher-voltage systems?

Makita’s answer was elegant: don’t fragment the platform—stack it.

LXT X2 products run on two 18V LXT batteries for maximum power, speed, and run time. Combine two batteries and you get 36V of power, while staying inside the same ecosystem. Instead of asking customers to start over with a new battery type, Makita asked them to add a second battery for the toughest jobs. Your existing investment still mattered.

Around the same time, Makita began putting lithium-ion technology into tools like the TD130D in 2005, marking a clear shift away from the older NiCd and NiMH era. The industry broadly followed, and lithium-ion became the standard for modern cordless tools because the advantages were simply too large to ignore: higher efficiency, longer runtime, and lighter weight.

The LXT launch didn’t just add a better battery. It set a template: commit early, build wide, protect compatibility, and let the ecosystem do the locking in. While other companies would churn through platform resets, Makita gave professionals something rare in tool land—confidence that buying in was a safe bet, job after job.

Developed with professional users in mind, the LXT System became Makita’s one-battery solution: premium power and run time across a growing lineup of tools designed to solve problems on commercial jobsites, consistently, without forcing customers to rebuild their kit every few years.

VII. The Brushless Motor Revolution (2009–2015)

If LXT was Makita’s strategic lock on the jobsite, brushless motors were the performance breakthrough that made the platform feel inevitable. And, again, Makita pushed early.

Look at the company’s own cadence and you can see the pattern: first cordless back in 1978, then the 18V LXT lithium-ion system in 2005, then a major leap in 2009 with the industry’s first 18V brushless motor impact driver. And in 2012, Makita doubled down on platform continuity with its first tools powered by two 18V lithium-ion batteries.

To understand why brushless mattered so much, you have to look at what it replaced.

Traditional electric motors use carbon brushes to deliver power to the spinning armature. Those brushes wear down. They create friction. They throw off heat. And over long days on a jobsite, they become a hard ceiling on both efficiency and tool life.

Brushless flips the architecture. Makita’s brushless motors eliminate carbon brushes entirely and run contact-free, using electronic controllers instead. That means less heat, less waste, and a motor that can run cooler and more efficiently for longer life.

For cordless tools, the payoff is dramatic: longer runtime on the same battery, higher usable power, and motors that simply last. And for a professional who’s pulling the trigger all day, those gains aren’t theoretical. They show up as fewer battery swaps, less downtime, and fewer tools dying early.

Makita wasn’t new to brushless, either. The company had introduced brushless tools for assembly work back in 2003, then brought brushless to contractors in 2009 with that impact driver. In other words, it didn’t just invent a feature and slap it on the shelf. It learned the tech in one environment, then deployed it where it mattered most: the trades.

This is where Makita’s motor DNA really pays off. Building a great brushless motor isn’t only about removing brushes. It’s about magnetic design, electronic control, and thermal management—exactly the kind of deep, unglamorous engineering Makita had been accumulating since 1915.

And then, in 2012, Makita made the complementary move that kept everything tied together: X2. Instead of telling customers, “Here’s a higher-voltage system, start over,” Makita built high-demand tools that run on two standard 18V LXT batteries. More power when you need it, without breaking compatibility.

Brushless made the tools better. X2 made the system smarter. Together, they turned LXT from a big lineup into an ecosystem that could stretch into heavier applications—while keeping the same batteries at the center of the relationship.

VIII. The XGT Era and the OPE Transition (2020–Present)

By 2020, the cordless world was running into a ceiling. The 18V class had gotten astonishingly good, but the most demanding jobs kept asking the same question: is this enough power without going back to cords or gas? Competitors were pushing harder, too—Milwaukee was scaling up with M18 FUEL, and DeWalt was marketing FlexVolt as a bridge to higher output.

Makita’s response was simple, and very un-Makita in one important way: it introduced a new battery platform.

Makita launched the XGT 40Vmax line in 2020.

XGT is a new 40V | 80V max system of cordless equipment and tools. XGT outpowers, outsmarts, and outlasts the rest.

In the UK, Makita began launching 40V Max XGT products from June 2020, positioning the system as a direct answer to a broader shift across the industry: batteries replacing other power sources in bigger and bigger machines.

Strategically, XGT was a different move than X2. X2 had been the elegant “stay in the same ecosystem, just add a second 18V battery” solution. XGT, by contrast, was a clean-sheet platform with its own tools, batteries, chargers, and accessories—built around larger battery cells and upgraded electronics to support heavier industrial applications.

And Makita didn’t stop at 40V max. It extended the same idea the company had already taught customers with X2: if one battery platform is good, two can be a lot better.

80V max (40V max X2)Two batteries mean more power! Makita-built brushless motors, along with two 40V max XGT Batteries, deliver the power and performance required for heavy-load applications. By using two 40V max XGT Batteries, you get 80V of power within one system. The increased power and performance allow XGT Cordless Equipment and Tools to rival corded tools and gas equipment.

That last phrase—rival gas equipment—is the tell. Because at the same time Makita was scaling up power for the jobsite, it was also leaning into a second, even bigger transition: outdoor power equipment.

For decades, chainsaws, blowers, mowers, and trimmers lived in the world of small engines. Loud, smoky, maintenance-heavy. But batteries and motors were getting good enough to make an alternative not just viable, but attractive—especially for pros dealing with fuel costs, noise complaints, and emissions rules.

Makita already had a head start here. It built what it describes as the world’s largest professional cordless outdoor power equipment system powered by 18V lithium-ion slide-style batteries, with more than 60 OPE products available in the 18V | 36V LXT System. In March 2022, Makita U.S.A. framed that expansion around rising demand for “greener” alternatives to gas.

“Over the past several years demand for cordless OPE has dramatically increased across the spectrum, from pro landscapers to homeowners, and to the dealers who serve them,” said Mario Lopez, director of product development, Makita U.S.A., Inc. “Pro landscapers are paying more for fuel while experiencing resistance to the noise and emissions of gas equipment, so they are seeking cordless equipment.”

Regulation only adds momentum. California and other states have begun banning or restricting gas-powered outdoor equipment due to emissions concerns, turning what used to be a preference shift into something closer to an inevitability.

Here’s the twist: Makita wasn’t new to gas. It had bought into that world on purpose when it acquired the Dolmar brand in 1991, gaining real chainsaw heritage and a professional outdoor lineup. But over time, Makita rebranded Dolmar saws as Makita—and then made the most definitive statement possible about where it thinks the market is going.

Makita announced it would stop making gas products in 2022. In a press release dated November 2, 2020, the company stated it would end production of engine products such as engine trimmers and engine chain saws.

That’s not a product decision. It’s a strategy. Makita is effectively saying the future of outdoor equipment is battery-powered, and it’s willing to walk away from its engine legacy to get there.

The expanding LXT System reflects that bet, with 18V and 36V options across lawn mowers, string trimmers, blowers, chain saws, brush cutters, pole saws, and more—positioned as lower-noise, lower-maintenance, zero-emissions replacements for gas equipment. And now, with XGT pushing higher output for heavier applications, Makita’s thesis is clear: the motor-and-battery stack that started inside a drill is on track to take over the yard, the park, and the entire landscape crew’s trailer.

IX. The Competitive Landscape: Battle of the Battery Platforms

The power tool industry today looks a lot like the smartphone wars did a decade ago. Nobody wins on a single device. You win on the operating system—the ecosystem. The tools are the apps. The batteries are the OS. And once a crew has standardized on one platform, switching isn’t just expensive. It’s disruptive.

It’s also a big, growing market. The global electric power tools market was estimated at about $48 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach roughly $72 billion by 2034. Plenty of brands show up in that arena—DeWalt, Milwaukee, Bosch, Makita, and many others—but the more interesting story is how differently the key players are built.

DeWalt isn’t a standalone company. It sits inside Stanley Black & Decker, alongside a long list of other brands and product lines. Milwaukee is also not independent—it’s owned by Techtronic Industries, the Hong Kong-based group that acquired Milwaukee in 1995 and has since scaled it into a powerhouse.

And TTI isn’t just “Milwaukee’s parent.” It’s a portfolio. Alongside Milwaukee, TTI also operates Ryobi in North America and several other regions, plus brands like Empire Level and Homelite. Through a licensing agreement, it also operates RIDGID cordless power tools that are sold exclusively at Home Depot.

Makita is the outlier. It’s one of the few largest tool companies that sells only under its own name. No sister brands. No “good-better-best” ladder across multiple logos. Just one badge, one identity, and a focus on professional-grade power tools—especially cordless.

That structural difference matters more than it sounds. Stanley Black & Decker has to spread attention, shelf strategy, and R&D across DeWalt, Craftsman, Black & Decker, and dozens of other priorities. TTI has to balance Milwaukee’s professional positioning with Ryobi’s consumer/DIY scale. Makita, by contrast, concentrates its resources on making one brand credible with pros, everywhere.

The scale gap is real, though. TTI booked record sales of $14.6 billion in 2024. Makita reported revenue of 741.391 billion yen, about $4.764 billion, in 2023, down about 3% from 2022. Put simply: TTI is much larger on the top line. But it’s also a broader machine, with multiple brands and segments pulling in different directions.

Where this gets especially sharp is North America. For the fiscal year ending March 31, 2024, Makita North America generated 96.111 billion yen in revenue from external customers, about $617.5 million—down from 121.685 billion yen, about $781.8 million, the year prior. In other words, a meaningful step down in a market that is still Makita’s third largest overall.

Over the same period, North America’s share of Makita’s total sales slipped, moving from roughly the mid-teens as a percentage of company revenue to closer to the low teens. That’s the competitive battleground: the region where Milwaukee’s aggressive marketing and Home Depot distribution have helped it capture mindshare—and where Makita, despite its heritage and product depth, has had a harder time holding position.

Europe tells the other half of the story. For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024, Europe represented Makita’s largest share of revenue—over 48% of the total. Nearly half the business, in one region.

So Makita’s geographic mix has become both its strength and its challenge. The company is dominant in Europe, but the battery platform war is fiercest in North America—and the players there have scale, retail leverage, and marketing engines that are hard to match.

X. Technology Deep Dive: The Innovation Engine

By now, Makita’s strategy is clear: pick a battery standard, build an ecosystem around it, and use compatibility as a moat. But ecosystems don’t hold together on branding alone. They hold together on the unsexy stuff—controls, sensors, seals, and the invisible engineering that keeps a tool alive when a jobsite is doing its best to kill it.

One of Makita’s core advantages here is STAR Protection Computer Controls. It’s communication technology that lets the tool and battery exchange data in real time, monitoring conditions during use and protecting against overloading, over-discharging, and overheating.

That last one isn’t optional. Lithium-ion packs deliver incredible power density, but they demand discipline. Push them too hard, too hot, or too long, and you don’t just shorten battery life—you risk serious safety issues. STAR Protection is Makita’s way of making sure the tool doesn’t win a short-term power battle at the expense of long-term reliability.

Then there’s the physical world. Jobsites aren’t lab benches. They’re dust, rain, slurry, grit, and the occasional “it fell off the ladder but we kept going.” That’s what Makita Extreme Protection Technology, or XPT, is built for: a series of integrated seals engineered to channel away dust and water for added durability and longer tool life.

These features can sound like marketing until you remember who Makita sells to. Professionals don’t buy “features.” They buy fewer failures. They buy mornings that don’t start with a dead tool, a cooked battery, and a trip back to the truck.

With the 40V range, Makita extends that philosophy into what it describes as a new, unique smart system designed to optimize battery performance and charge times. It’s another layer of digital communication—between battery and charger, and between battery and tool—built to help protect against overheating and over-discharge.

Taken together, this is the through-line: Makita’s real product isn’t any single drill or saw. It’s the integration between motor, battery, tool, and charger. And that integration reflects decades of accumulated expertise—understanding how motors behave under load, how batteries degrade over time, and how control systems can keep performance high without sacrificing safety or lifespan.

XI. Business Model & Distribution Strategy

Makita’s global reach is built on something you normally associate with consumer giants, not jobsite brands: a dense, disciplined network for manufacturing, sales, and support—built to keep pros productive.

From its headquarters in Anjō, Japan, Makita expanded into one of the world’s most successful power tool manufacturers, with branches and subsidiaries across nearly every major economy. Its products are sold in more than 160 countries.

What’s even more striking is where those tools are made. Makita manufactures in Japan, China, Romania, Thailand, the United Kingdom, Brazil, the United States, and Germany—and about 90% of its production happens outside Japan.

For a Japanese company, that’s a loud strategic signal. Makita didn’t just become a global exporter. It became a global manufacturer, putting production closer to demand to reduce shipping friction, respond faster to local market needs, and sidestep the kinds of tariffs and trade pressures that can suddenly turn “made far away” into a disadvantage.

Makita’s distribution strategy is equally intentional. While some competitors lean on exclusivity—like TTI’s relationship with Home Depot for Ryobi and RIDGID—Makita sells through multiple channels: home improvement retailers, professional tool distributors, and industrial suppliers. That wider channel mix gives it reach, but it also fits Makita’s brand posture: built for pros, but available wherever pros actually buy.

In the U.S., Makita’s hub is Makita U.S.A., Inc. in La Mirada, California, which supports an extensive distribution network across the country. And the product range reflects the same “own the whole workday” ambition you see in its battery platforms: industrial power tools, power equipment, pneumatics, cleaning solutions, and the accessories that keep all of it running.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Moats and Vulnerabilities

Step back and run Makita through a few classic competitive frameworks, and you get a company with real, earned advantages—and a handful of pressure points that matter more now than they did a decade ago.

Competitive Advantages:

The biggest moat is switching costs. Makita’s LXT System has become the world’s largest compatible 18V slide-style battery platform, with over 350 solutions. Once a contractor has built up a stack of batteries and chargers—often 10 to 20 batteries, representing a serious investment—the economics push hard toward staying put. Switching brands isn’t just buying a new drill. It’s re-buying your entire power infrastructure.

Scale helps, too. Makita operates 10 manufacturing facilities across 8 nations, and its tools are sold in roughly 50 countries. That global footprint isn’t just about reach; it supports cost advantages and consistency in battery and motor production.

Then there’s the brand. Makita’s teal blue is jobsite-famous, and it still carries a specific meaning: professional-grade, durable, and engineered with care.

Finally, there’s process power—Makita’s deepest, hardest-to-copy advantage. More than a century of motor engineering has created institutional knowledge in motor design, battery integration, and manufacturing efficiency that only comes from decades of iteration. Plenty of companies can copy features. Fewer can copy a hundred years of accumulated “we’ve seen this fail before” experience.

Competitive Vulnerabilities:

The most visible weakness is North America. Makita’s tools aren’t absent because they’re bad—they’re absent because the company hasn’t matched competitors on marketing, partnerships, and retail presence. Milwaukee, in particular, has been aggressive, and Makita has struggled to keep the same level of mindshare on modern jobsites.

There’s also a platform risk in XGT. Unlike DeWalt’s FlexVolt approach, which offers backward compatibility with 20V batteries, XGT is a separate ecosystem. XGT tools don’t run on LXT batteries. That forces customers to make a cleaner, harder choice: double down on LXT, or start building a second battery world.

And the competitive field is tightening from below. Stanley Black & Decker, Bosch, and Techtronic Industries still dominate the premium tiers, but they’re facing growing pressure from agile Chinese entrants using regional assembly and aggressive pricing. Brands under companies like Chervon, including EGO and Skil, have been gaining ground with compelling tools at lower price points.

XIII. Investor Playbook: Lessons and KPIs

The 43-Year Incubation Thesis: Makita’s story is a reminder that “speed” isn’t the only path to advantage. The company spent decades building deep motor expertise before it ever shipped a power tool. That patience created the know-how that later showed up as durability, efficiency, and credibility with professionals. Sometimes the edge comes from depth, not haste.

Platform Before "Platform": Long before anyone talked about platform strategy, Makita was already living it. It built a battery ecosystem where each new tool made the batteries more valuable, and each new battery made the next tool purchase easier to justify. By 1987, Makita already had 25 tools running on compatible batteries. The broader lesson travels well: compatibility, standards, and continuity can be just as powerful as raw product specs.

The Single-Brand Independent Strategy: In a category dominated by conglomerates, Makita shows the upside of staying independent. Unlike Stanley Black & Decker or TTI, it doesn’t have to juggle internal brand competition or split attention across wildly different customer segments. It gets to concentrate—one brand, one identity, one job to do: earn and keep professional trust.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch:

For anyone tracking Makita going forward, two metrics matter more than most:

-

Outdoor Power Equipment Revenue Growth Rate: The gas-to-battery shift in outdoor equipment is one of the biggest category transitions Makita has ever had the chance to ride. If Makita’s strategy is working, OPE should grow faster than the core power tools business for years. Strong relative growth here would be the clearest proof that the pivot is landing.

-

North American Market Share Trend: North America is still the biggest battlefield in power tools—and it’s where Makita has been under the most pressure. Stabilizing share, or better yet clawing it back, would be a real signal that Makita is regaining jobsite mindshare against Milwaukee and DeWalt.

XIV. The Quiet Giant at a Crossroads

There’s something almost zen about Makita’s corporate personality. No splashy campaigns. No celebrity partnerships. No constant reinvention for the sake of headlines. Just a steady drumbeat of improvements in motors, batteries, and the small design details that make a tool feel right after eight hours on a jobsite.

For more than a century, Makita has kept coming back to the same core idea: perfect the electric motor, then put it to work in more and more demanding places. That through-line runs cleanly from a 1915 repair-and-sales shop in Nagoya to the company’s modern cordless lineup, including high-output tools like 80V max (40V max X2) equipment. Different eras, different form factors, same obsession: portability, reliability, and control.

But Makita is not coasting. The challenges are real. Milwaukee has won the mindshare of a generation of American contractors. Makita’s decision to run both LXT and XGT creates a harder choice for customers, and sometimes simple confusion. And with Europe representing such a large share of revenue, Makita is more exposed to regional economic swings than it would be with a more balanced global mix.

And yet, Makita has an advantage that’s easy to overlook in a world of sprawling tool empires: unity. One brand. One identity. One core customer. Instead of managing internal competition across a portfolio, Makita can concentrate resources and attention on a single integrated system—tools, motors, batteries, chargers, and support designed to work together.

So the question for the next decade isn’t whether Makita can engineer. It’s whether focus keeps compounding into advantage, or starts to look like a constraint. As the industry consolidates and platform wars intensify, does independence become isolation? Or does Makita’s patient, engineering-first culture keep producing the kind of durable, category-shaping progress that made it a cordless pioneer in the first place?

If its history tells us anything, it’s that Makita won’t try to win this moment with noise. It will do it the way it always has: by making motors, making tools, and making them better—one iteration at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music