BayCurrent Inc.: Japan's Digital Transformation Play

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

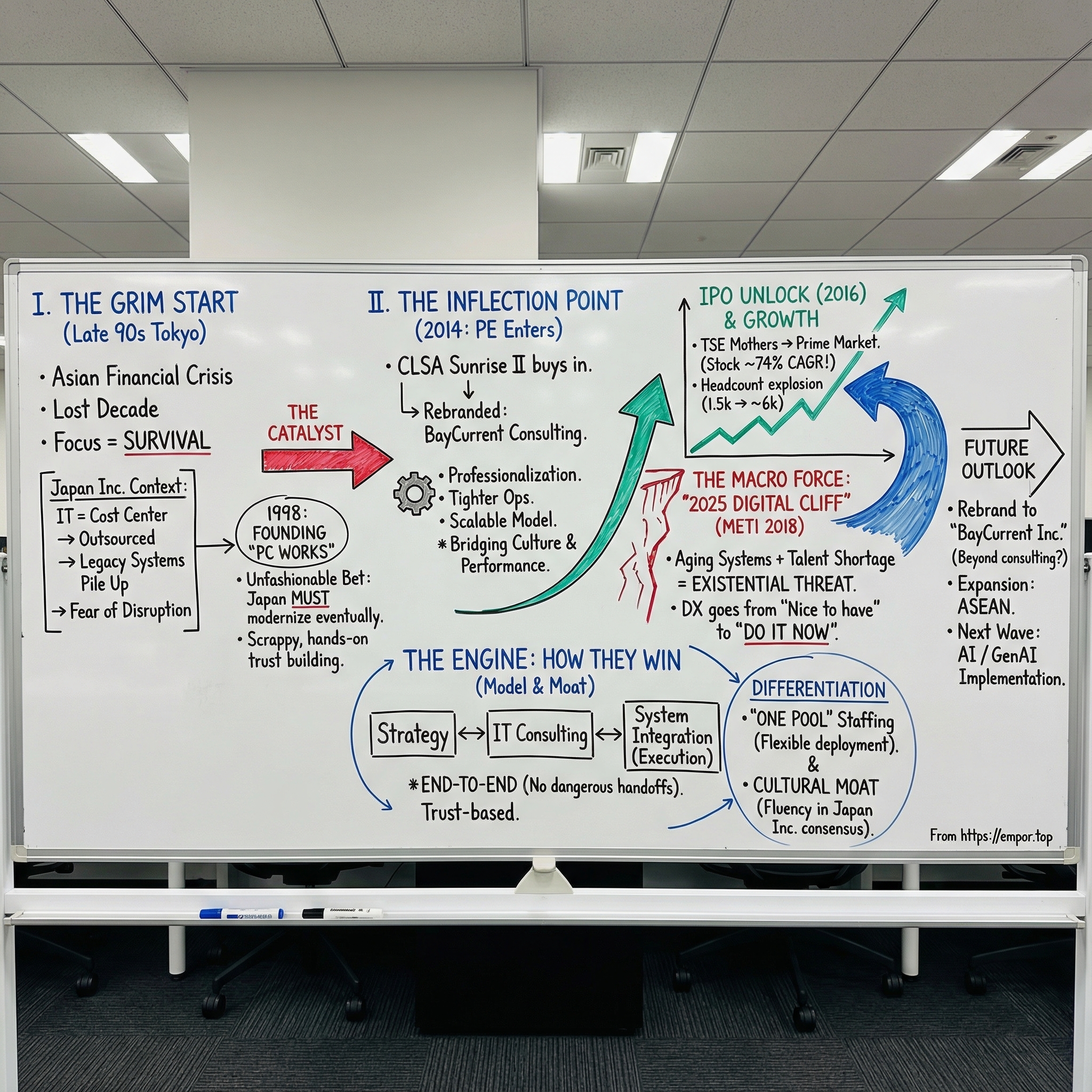

Picture Tokyo in the late 1990s. The Asian financial crisis has just rolled through the region, Japan’s banks are wobbling, and the country is stuck in what would come to be known as the “Lost Decade.” It’s a moment when most companies are focused on one thing: survival.

And in the middle of that uncertainty, a small consulting firm opens its doors in the capital with an unfashionable thesis—Japan’s biggest companies would eventually have to modernize their technology, whether they wanted to or not.

Fast forward to today, and that modest bet has turned into one of Japan’s standout business stories. BayCurrent’s market cap sits around $8.48 billion, supported by roughly $816 million in trailing 12-month revenue and about 152 million shares outstanding. Since its 2016 IPO, the stock has been on a tear—compounding at roughly 74% annually, climbing from ¥192 at listing to the multi-thousand-yen range.

At its core, BayCurrent is a Tokyo-based consulting firm founded in 1998. It sells broad, end-to-end help to major companies: diagnosing management problems, redesigning operations, and—crucially—dragging complex IT environments into the modern era, with enough hands-on capability to actually get implementations done.

The central question is the one you’re probably already asking: how did a small IT consulting outfit, born in Japan’s bleakest economic chapter, become an $8 billion leader by riding Japan’s belated digital awakening?

The answer lives at the intersection of timing and positioning: a deep understanding of how Japan Inc. actually works, a private equity-led transformation that professionalized the business, an IPO that unlocked the next phase of growth, and a looming national forcing function—the “2025 Digital Cliff”—that made digital transformation go from “nice to have” to “do it now.”

That’s the roadmap for this story: the scrappy early years, the PE inflection point, the public-market rocket ship, and the macro wave that turned BayCurrent’s capabilities into a must-buy for Japan’s largest enterprises.

And along the way, we’ll keep coming back to the investor questions that matter: What does a moat look like in a people business? How durable is cultural advantage in consulting? And is Japan’s digital transformation the beginning of a long secular shift—or a one-time catch-up cycle that eventually fades?

Let’s dig in.

II. Japan's Unique Business & Technology Context

If you want to understand BayCurrent’s rise, you have to start with a seeming contradiction: Japan is a country famous for engineering excellence—cars, consumer electronics, industrial robotics—and yet, inside many of its biggest corporations, technology has often been treated as something to endure, not something to weaponize.

Part of that comes from how Japan Inc. has traditionally been run. For decades, Japan has been a tough place for investors not because the companies aren’t capable, but because many of them optimized for survival and stability over shareholder returns. Corporate longevity, employee welfare, and stakeholder harmony mattered more than squeezing out efficiency. That mindset shaped everything, including the willingness to overhaul old systems. Big change is disruptive, and disruption is the enemy of stability.

Then there’s the way IT work is organized. In many Japanese companies, IT isn’t built as a core capability. It’s outsourced—often almost entirely—to service providers, with the company keeping only high-level strategy and governance in-house. On top of that, job rotation means the people “running IT” are frequently generalists passing through on a career path, not specialists building deep technical expertise over time. And those outsourced IT providers are often subsidiaries that double as a kind of corporate waiting room—where managers who aren’t moving up in the parent company end up finishing out their careers.

Put those pieces together and you get a nasty flywheel. IT becomes a backwater. High performers avoid it. Leaders treat it as a cost center. Requests get lobbed over the wall for someone else to implement. Systems age, complexity piles up, and modernization becomes harder, riskier, and more politically fraught with every passing year.

This context also helps explain something that surprises outsiders: why global consulting giants—McKinsey, BCG, Accenture, and the Big 4—didn’t simply steamroll Japan the way they did in many other markets. Yes, they’re major competitors in Japan. But the standard global playbook doesn’t always translate. Japanese clients often value long-term, trust-based relationships and expect a deep understanding of how decisions actually get made: consensus-building, careful sequencing, face-saving, and a deliberate pace that’s hard to square with imported frameworks and rotating teams of junior staff.

It also didn’t help that local players could be leaner and more responsive. Without the weight of global headquarters—and without needing to fit Japan into a standardized worldwide model—domestic firms could tailor how they staffed, priced, and delivered work to fit local expectations.

That’s the opening BayCurrent stepped into. It’s been in Japan since 1998, and it built credibility the slow, hard way: delivering modern consulting capabilities while speaking the cultural language of Japan Inc. fluently. Over time, those relationships—and the trust that comes with them—became a quiet but real advantage.

And for investors, this is the crux of the whole story. Japan’s relative “digital backwardness,” paradoxical as it sounds, is the source of BayCurrent’s demand. The only question is the one that always matters with a tailwind: does it disappear quickly once the catch-up starts, or does it persist long enough for a company like BayCurrent to keep compounding into something much bigger?

III. Founding & Early Years: PC Works to BayCurrent (1998–2013)

BayCurrent’s origin story isn’t a mythic garage tale or a founder with a manifesto. It starts with a name that’s almost disarmingly plain: PC Works.

The company was founded in Tokyo on March 25, 1998, with a straightforward mission: consulting, system integration, and outsourcing across management, operations, and IT. And in December 2006, it took on the name it’s known for today, changing from PC Works Co. Ltd to BayCurrent Consulting Co. Ltd.

The timing was brutal. Japan was still absorbing the aftershocks of the Asian financial crisis. Banks were buckling under bad loans. Confidence was thin. Launching a consulting business into that environment either took real conviction—or a willingness to grind.

That early “PC Works” identity mattered. It hinted at a company built less around slide decks and more around execution. While the marquee global firms tended to lead with strategy, BayCurrent grew up doing the unglamorous work Japanese enterprises desperately needed: making complex technology actually work inside complex organizations.

Over time, BayCurrent’s offering broadened into a full-service menu: strategy and business process consulting, IT consulting, and system integration. That meant everything from company and business strategy, M&A and alliances, digital strategy, turnarounds, globalization, innovation, and marketing and sales strategy—down to the practical guts of IT: governance, organizational improvement, cost optimization, architecture, asset evaluation, talent development, and even RFP creation. And then the heavy lifting of system integration: design, development, infrastructure operation, and maintenance.

The client base expanded the same way—steadily, methodically, and across the economy. BayCurrent took on work in high tech, media and entertainment, telecommunications, mobility, healthcare, retail, consumer products and distribution, industrial machinery, banking and payments, capital markets, insurance, energy, materials, chemicals and plants, transportation and logistics, developers, general trading companies, and aerospace and defense.

That breadth wasn’t an accident, and it wasn’t just “nice diversification.” It became an asset. Instead of building a firm around rigid industry silos, BayCurrent accumulated reps across sectors—experience that would later feed directly into its “one pool” staffing approach, where consultants aren’t permanently boxed into a single vertical.

From 1998 through 2013, though, this was still an apprenticeship phase. Without a global brand to open doors, BayCurrent earned trust the hard way: one project at a time. Along the way, it built scar-tissue expertise in the realities of Japan Inc.—legacy systems running on aging technologies, organizations engineered to avoid disruption, and IT functions that often lacked deep specialist talent.

By the end of this era, BayCurrent had a foundation: relationships, delivery capability, and a feel for how to sell change in a country that’s historically been allergic to it. What it didn’t have yet was scale—or a catalyst to turn a solid, relatively quiet consulting business into something much bigger.

That catalyst arrived in 2014, when private equity showed up with a very different vision of what BayCurrent could become.

IV. The PE Inflection Point: CLSA Sunrise II Takes the Wheel (2014)

Every great business has a moment where “steady progress” turns into a different sport entirely. For BayCurrent, that moment came in 2014, when CLSA Capital Partners’ Sunrise II fund stepped in and took control.

The mechanics mattered. In April 2014, a new entity called Byron Holdings was set up. Two months later, in June, Byron Holdings acquired BayCurrent Consulting, and the combined entity then took the BayCurrent Consulting name. That June 2014 transaction is the pivot point: Sunrise II’s investment was completed, and BayCurrent moved from being a solid, relationship-driven consulting firm to being a company run with an explicit value-creation plan.

To understand why this was such a big deal, you have to understand who Sunrise is. Sunrise Capital is CLSA Capital Partners’ Japan-dedicated private equity strategy, built for mid-cap buyouts. Their approach is deliberately hands-on: they can second professionals into portfolio companies, push operational upgrades, and use CLSA’s global network to support growth initiatives, including overseas expansion. Since launching in 2006, Sunrise Capital raised about $1.5 billion and completed investments in roughly 30 companies, counting both initial and follow-on deals.

Sunrise II, specifically, targeted established Japanese mid-caps with clear growth potential. CLSA Capital Partners held the final closing of Sunrise II in October with about $210 million of commitments, raised from a mix of limited partners across the US, Europe, and Japan. This wasn’t “hot money.” It was institutional capital coming with institutional expectations.

So what did BayCurrent get out of it?

The classic private equity playbook showed up fast: tighter operations, better governance, and a much sharper focus on building a business that could scale. But in Japan, that playbook does something else too. It creates a bridge between the habits of Japan Inc.—consensus, stability, incremental change—and the performance demands of public markets, where numbers, accountability, and pace matter.

And that bridge is hard to build in consulting, because consulting doesn’t have factories or software products you can optimize in isolation. The assets walk out the door every night. Value creation means improving the organization itself: making it a stronger platform for talent, raising service quality, and getting more consistent productivity out of the same human-capital base.

The two-year window between the 2014 acquisition and the 2016 IPO became BayCurrent’s intensive “get ready for prime time” phase. Sunrise II worked alongside management to professionalize the firm, strengthen financial controls, and reshape the organization into something that could withstand public-market scrutiny. BayCurrent came out the other side with stronger execution, a more scalable operating model, and—according to management later on—top-level profit margins for the consulting industry.

Just as importantly, Sunrise II left BayCurrent positioned for the wave that was starting to build underneath Japan: digital transformation moving from a buzzword to a mandate. When demand surged after the IPO, BayCurrent would have the operating muscle to capture it.

On September 2, 2016, CLSA Capital Partners announced BayCurrent’s IPO on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Mothers. The offering was completed by Sunrise II—the same fund that had bought in just two years earlier—and it marked the handoff from private equity’s transformation phase to the public-market growth story.

V. The IPO & Public Market Journey (2016–Present)

When BayCurrent went public in September 2016, it wasn’t just a private equity sponsor ringing the bell on a tidy two-year turnaround. The IPO was also a strategic unlock. Japan’s digital transformation was shifting from “someday” to “we can’t keep putting this off,” and BayCurrent needed the one thing consulting firms always need to grow: more capacity. Public markets could fund the next phase of hiring, training, and organizational build-out.

The IPO date was September 2, 2016, and BayCurrent listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Mothers section—the growth market designed for emerging companies. From there, the company climbed the TSE ladder: it moved to the First Section in December 2018, and then to the Prime Market in April 2022 after the exchange’s restructuring.

That path—Mothers to First Section to Prime—reads like a corporate coming-of-age story in Japan. Each step comes with tougher expectations around size, liquidity, and governance. And to Japanese investors, Prime isn’t just another venue. It’s a signal that the company now belongs in the top tier of Japan Inc.

Operationally, the numbers show how quickly BayCurrent scaled once it had public-market oxygen. For the fiscal year ending February 2025, BayCurrent reported 116 billion yen in revenue. As of April 2025, it had 5,904 employees. The company is led by Yoshiyuki Abe, who serves as Member of the Board, Chairman of the Board, and President.

That headcount is the clearest indicator of the machine BayCurrent built post-IPO. In April 2018, the company had 1,528 employees. Seven years later, the workforce was nearly four times that size—an eye-popping expansion in a business where people are both the product and the bottleneck.

Financially, 2024 captured the momentum: revenue rose to 116.06 billion yen from 93.91 billion the year before, while earnings climbed to 30.76 billion yen.

And then there’s the part that made BayCurrent impossible for public-market investors to ignore: the stock. Since the IPO, shares have compounded at roughly 74% annually, running from ¥192 at listing to the multi-thousand-yen range. That’s a rare outcome for a professional services firm—especially one competing in the same arena as the global consulting giants.

So what drove it? Three forces reinforcing each other: rapid demand growth as Japanese enterprises finally committed to modernization, profit margins strong enough to stand out in consulting, and a public-market re-rating as investors realized this wasn’t a typical “hours-for-fees” business—it was a scaled platform positioned in the middle of a national catch-up cycle.

Abe also framed the IPO as a governance statement, not just a financing event. He argued that independent management and operations would help BayCurrent keep delivering “superior, customized and unbiased solutions” to clients—without being shaped by private equity’s timelines and preferences.

For investors looking at BayCurrent now, the public-market chapter cuts both ways. It proves just how big the opportunity can be when Japan decides it has to change. But it also raises the bar: after a run like this, the market price assumes BayCurrent can keep executing at an unusually high level, even as the organization scales and the competitive pressure rises.

VI. Japan's "2025 Digital Cliff" – The Macro Tailwind

The single most important force in BayCurrent’s story isn’t something management engineered. It’s a slow-moving crisis inside Japanese corporations—one that the Japanese government itself named, measured, and tried to shock the country into fixing.

In 2018, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, or METI, put a label on the problem: the “2025 Digital Cliff.” Six years later, many companies were still stuck in the same dangerous place—running critical operations on aging systems, knowing the risks, and struggling to move.

METI’s September 2018 “DX Report” laid out the stakes in plain terms. If Japanese businesses couldn’t use modern digital technology to create new business models or even upgrade old ones, Japan could face an economic loss of as much as ¥12 trillion per year after 2025. That’s not a one-time hit. It’s a permanent drag—year after year—as competitiveness erodes.

The diagnosis was even more alarming when you looked at the plumbing. METI cited the Japan Institute Users Association of Information Systems: if trends continued, by 2025, 60% of Japan’s large companies would be operating core systems more than 20 years old. It’s the corporate equivalent of trying to run a modern company on a 2005 computer—except these aren’t personal laptops. They’re the mainframes and backbone systems that handle billing, logistics, customer records, and financial operations.

And METI wasn’t guessing. Even back in 2016, 20% of companies were already running core systems that were 21 years old or more, and another 40% had systems in the 11-to-20-year range. The longer these systems stay in place, the harder they are to replace: custom code no one wants to touch, dependencies that pile up, and internal teams that increasingly don’t remember how the whole thing works.

Then comes the second constraint: people. METI warned that the cliff wasn’t just about technology; it was also about the shortage of ICT engineers needed to modernize it. By 2025, Japan was projected to be short around 360,000 software engineers, with forecasts suggesting the gap could widen further by 2030. In other words, even companies that want to modernize run into the same wall: there simply aren’t enough experienced hands to do the work.

So did Japanese companies respond?

On the surface, yes. METI and Fujitsu surveys in 2020 found that nearly half of small and medium-sized enterprises said they were actively promoting DX across their companies, and large enterprises—those with more than 5,000 employees—reported adoption rates close to 80%. That’s real momentum, and it’s a direct tailwind for firms like BayCurrent.

But momentum isn’t the same as outcomes. More recent analysis suggests that while a large majority of Japanese companies say they are promoting DX initiatives, only about one-third have produced notable results. The gap between intent and execution is still wide.

METI’s actions show it knows that too. In FY2024, the ministry established a Legacy Systems Modernization Committee under its Priority Plan for the Realization of a Digital Society. The committee’s job was straightforward: assess how widespread the legacy-system problem still is, clarify what’s blocking modernization, and study practical measures to break the logjam as the country approached the cliff.

This is where BayCurrent fits perfectly. The opportunity isn’t that companies are unaware. It’s that many of them can’t finish the job on their own. They need outside experts who can navigate the technology, the internal politics, and the realities of Japan Inc.—and then stay long enough to actually implement change, not just recommend it.

Zoom out, and the market data points the same way. The Japan management consulting services market was estimated at $6.83 billion in 2025 and forecast to reach $11.73 billion by 2030, an expected 11.42% CAGR. Demand has been driven by transformation programs across both the public and private sectors—where “DX” isn’t a slogan anymore, it’s a multi-year execution problem.

For BayCurrent, the 2025 Digital Cliff did what decades of good arguments couldn’t: it created urgency. Modernization stopped being optional and started looking existential. And once that switch flipped, every major Japanese corporation needed partners that could deliver both technical change and cultural change—at scale.

VII. The BayCurrent Business Model & Differentiation

So what, exactly, does BayCurrent sell—and why do Japan’s biggest companies keep paying for more?

At a high level, BayCurrent positions itself as a comprehensive consulting firm focused on helping clients solve management issues and drive sustainable development. In practice, that promise lands in a very specific place: the messy intersection of business change and technology change, where strategy is useless if nobody can actually ship the work.

The firm’s services span three connected domains: strategy and business process consulting, IT consulting, and system integration. Strategy and business process consulting covers company and business strategy, M&A and alliances, digital strategy, turnarounds, globalization, innovation, and marketing and sales strategy. IT consulting includes IT strategy, governance, organizational improvement, cost optimization, architecture, asset evaluation, talent development, and support like RFP creation. And then system integration handles what happens after the plan is approved: system design and development, plus infrastructure operation and maintenance.

That end-to-end capability is the point. BayCurrent sits in the middle of two worlds that often don’t talk to each other. Pure strategy firms can diagnose and recommend, but typically hand execution to someone else. Pure IT services firms can implement, but often start from a blueprint written by someone else. BayCurrent’s pitch is continuity: the same team that helps define the strategy can stay through implementation, reducing the handoff friction, coordination costs, and information loss that tend to sink multi-vendor transformations.

In Japan, where large programs move through consensus and risk management, that continuity is especially valuable. When the work is complex and politically sensitive, clients often prefer fewer handoffs and clearer accountability.

On top of those three core buckets, BayCurrent markets breadth across themes Japanese enterprises are actively grappling with: AI, transformation, sustainability and GX, strategy and corporate finance, customer experience, digital technology, data analytics, technology innovation, global business, marketing and sales, M&A, supply chain and operations, intelligent automation, talent and organization, cost management, engineering and manufacturing, cloud, digital commerce, infrastructure, security, and managed services.

Delivering that kind of range takes more than a long list on a website. The key organizational choice BayCurrent points to is its “one pool” staffing model. Employee reviews describe an “open pool” system, where consultants can be moved in and out of projects based on the experience level required—an approach that can help allocate more tenured talent to the highest-impact work, while keeping teams flexible as demand shifts.

Management’s logic is that consultants build better judgment by working across industries and service types, rather than being locked into a single vertical. That’s a deliberate contrast to many global consulting firms, where industry specialization is often the path to seniority and influence.

BayCurrent has also invested in being seen as more than a delivery shop. It was among the first Japanese consulting firms to explicitly advocate for digital transformation and to package it into structured, actionable approaches. Through books and articles on DX, sustainability transformation (SX), and customer experience (CX), the firm worked to position itself as a source of ideas—not just a vendor of billable hours.

That posture shows up in the company’s public-facing milestones too, including collaboration with the University of Tokyo, Joji Noritake’s appointment to the Board of Directors of Generative AI Japan, participation in the GX league, and publishing on topics like embedded finance and cloud utilization. Together, those efforts reinforce a consistent message: BayCurrent intends to help shape where Japanese enterprise transformation is going, not merely respond to it.

Thought leadership isn’t charity. It helps win clients who want current guidance, it creates media and speaking opportunities, and it supports recruiting—especially for ambitious consultants who want to work on problems that feel timely and consequential.

Across client types, BayCurrent’s value proposition is consistency and follow-through. Clients cite dedication to results, attention to detail, and an ability to navigate complex financial landscapes—traits that matter when transformations are large, high-stakes, and stretched over years.

For investors, the model can produce attractive economics. At scale, consulting can generate high margins because the primary input is talent, and strong firms can bill far above employment costs. But the constraints are just as clear: hiring enough qualified people, keeping utilization high enough to stay efficient, and maintaining quality as headcount grows fast—because in consulting, the product is only as good as the people delivering it.

VIII. Expansion & Strategic Initiatives

BayCurrent’s growth story is, overwhelmingly, a Japan story. The vast majority of its revenue still comes from domestic clients. But management has been clear that the company doesn’t intend to stay a Japan-only business forever—and the way BayCurrent has been positioning itself suggests it wants to be present wherever Japanese enterprise transformation is headed next.

CEO Yoshiyuki Abe has talked about overseas expansion in practical terms: in a mature home market, moving into ASEAN is the natural next step. And Singapore, in particular, is the obvious beachhead. It’s close to Japan, it functions as a regional hub, and it’s where many Japanese corporates coordinate their Southeast Asia expansion. BayCurrent’s advantage here is straightforward: it already has deep relationships with major Japanese enterprises, so it can follow its clients abroad as they build, buy, and modernize in the region.

At the same time, BayCurrent has been placing markers in the two big transformation agendas reshaping Japanese corporations.

One is digital, and specifically AI. Joji Noritake, a Managing Executive Officer, was appointed to the Board of Directors of Generative AI Japan, a general incorporated association. The other is green transformation: BayCurrent participated in the GX League.

These aren’t just resume lines. They put BayCurrent closer to the center of how Japan is thinking about the future—where policy is going, what standards are forming, and which companies are showing up early. That kind of access and visibility matters in Japan’s relationship-driven corporate environment, especially when clients are trying to make big, risky bets on new technology and new regulatory realities.

Then, in September 2024, BayCurrent made a subtle but meaningful branding move: it changed its corporate name from BayCurrent Consulting, Inc. to BayCurrent, Inc.

Dropping “Consulting” is a signal. It suggests the company sees itself evolving beyond pure advisory work—potentially toward a broader business services platform that could include managed services, technology-enabled delivery, or other offerings that don’t fit neatly into a traditional consulting engagement.

And if there’s a next wave that could rival the DX boom that powered BayCurrent’s post-IPO scale-up, it’s AI and generative AI. Japanese enterprises are now trying to operationalize AI in real businesses, and they’re running into familiar obstacles: limited internal expertise, organizational resistance, and legacy systems that were never built for modern data and AI workloads. BayCurrent’s proximity to the Generative AI Japan ecosystem suggests it expects this to be a major market—and wants to be seen as a credible guide through it.

For investors, all of this reads as optionality layered on top of a strong domestic engine. The base case is continued growth as Japan keeps grinding through DX. The upside case is that BayCurrent successfully expands into ASEAN and becomes a go-to partner for AI and GenAI adoption—turning the next technology cycle into another multi-year compounding opportunity.

IX. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see how defensible BayCurrent really is, it helps to step back from the growth chart and look at the competitive physics of the business. Michael Porter’s Five Forces gives us the right lens.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

On paper, consulting looks easy to start. You don’t need a factory, you don’t need patents, and the “inventory” is just people. But in Japan, the real barrier isn’t capital. It’s trust.

BayCurrent’s advantage is narrow but meaningful: it understands Japanese work culture and has cultivated relationships across industries over decades. In a market where long-term relationships and reputation carry outsized weight, that kind of credibility can’t be spun up quickly.

New entrants run into a classic chicken-and-egg problem. Clients want proof you’ve delivered on similar work before. But you can’t build that proof without clients taking a chance on you. Meanwhile, recruiting becomes its own barrier: top talent tends to follow brand, and brand takes years of consistent delivery to build.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Talent): HIGH

In consulting, the “suppliers” are the people who do the work. And right now, they hold the leverage.

Corporate problems have gotten more complex as competition has intensified and market structures have shifted. That raises the premium on high-end expertise. Layer on Japan’s IT talent shortage, and the negotiating power of skilled consultants goes up even more.

BayCurrent isn’t just competing with McKinsey, BCG, Bain, the Big Four, and Accenture. It’s also competing with tech companies, startups, and internal corporate innovation teams that are increasingly well-funded and aggressive about hiring.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

BayCurrent’s buyers are large Japanese enterprises, and individually they have real leverage. They can demand customization, run competitive bids, and push on pricing.

But the 2025 Digital Cliff dynamic changes the tone of negotiations. When modernization feels existential rather than optional, the buyer’s leverage softens. Demand rises, timelines tighten, and “cheapest” becomes less important than “can you actually deliver.”

IDC Japan projected the Japanese consulting market to expand meaningfully through 2025, with digital consulting in particular growing far faster than the overall market. That kind of growth environment tends to support pricing and utilization across the industry—especially for firms that can both plan and execute.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The most obvious substitute is building in-house teams. In reality, most Japanese companies struggle to do it at the required scale and speed—especially given the country’s shortage of IT professionals.

And while there are plenty of “partial substitutes,” each comes with trade-offs. Global consulting firms can be an alternative, but they often lack local cultural fluency. Traditional system integrators can build and run systems, but they’re not always set up to lead business strategy and organization-wide change. That leaves BayCurrent’s integrated strategy-through-implementation approach in a relatively protected middle ground.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is still a brutal arena. BayCurrent competes with MBB, the Big Four consulting arms, Accenture, and domestic rivals. The market tends to sort into tiers: global giants with boardroom access and large delivery engines, and Japanese specialists that lean into cultural fit, speed, and an execution-first posture.

Despite that intensity, BayCurrent’s margins and return on capital suggest it’s doing something better than many peers. In a crowded market, the differentiator that matters most is the ability to own the whole arc of a transformation—from strategy to implementation—so clients don’t get stuck managing handoffs between firms when the work gets hard.

X. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework is a useful way to pressure-test how durable BayCurrent’s advantages really are. Porter tells you what the industry does to you. Helmer asks the more pointed question: what do you have that stays valuable even as competitors react?

Scale Economies: MODERATE

BayCurrent had 5,467 employees, which matters in a consulting business because scale buys you coverage and flexibility. With a bigger bench, you can serve more industries, share knowledge across teams, and staff projects more efficiently—getting the right people onto the right work at the right time.

But there’s a hard ceiling on how far scale takes you. Consulting is still, fundamentally, hours delivered by humans. Unlike software, you can’t copy-paste a project at near-zero cost. Scale helps absorb overhead and build internal capability, but it doesn’t magically change the labor economics of delivery.

Network Economies: LOW-MODERATE

BayCurrent does get a kind of knowledge compounding. More projects create more pattern recognition. That insight improves advice and execution, which helps win more work. And the “one pool” model reinforces this, because learnings can move across industries instead of getting trapped inside vertical silos.

What BayCurrent doesn’t yet have—at least not at the iconic level—is the alumni flywheel you see at firms like McKinsey or BCG, where former consultants end up in senior roles across corporate Japan and generate referrals for decades.

Counter-Positioning: HIGH

If there’s a signature “power” in the BayCurrent story, it’s this one.

Many global consulting firms bring a partner-leverage model, global overhead, and standardized methodologies. Those can be strengths elsewhere. In Japan, they can also be friction—misaligned with how decisions get made, how trust is built, and how large organizations actually move.

BayCurrent’s Japanese-first approach—deep cultural fluency, an integrated strategy-to-implementation model, and flexible staffing through the “one pool” system—creates a position that global players can’t easily mirror without changing how they operate. Some observers also argue that local players can be more cost-competitive and faster-moving precisely because they aren’t carrying global headquarters overhead.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Switching costs in Japanese enterprise work aren’t just contractual—they’re relational and operational.

Over time, BayCurrent accumulates deep knowledge of a client’s systems, internal stakeholders, decision processes, and unwritten rules. In multi-year transformation programs, that institutional knowledge becomes part of the project’s infrastructure. Changing firms midstream often means losing context, resetting trust, and increasing execution risk—costs many clients would rather avoid.

Branding: MODERATE (Growing)

BayCurrent is well-regarded in IT and digital, but it doesn’t have the instant global brand recognition of McKinsey or Accenture. It has been building credibility through thought leadership—books and articles on DX, SX, and CX—and through the signaling effect of its public-market journey, including its Prime Market listing.

But brand here is still an asset in motion: meaningful and strengthening, not yet an unassailable fortress.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

BayCurrent has operated in Japan since 1998, and it pairs deep industry experience with a client-centric approach aimed at solving clients’ most pressing challenges. In a trust-heavy market, the ability to navigate Japanese work culture—and the relationships built across industries—functions like a narrow moat.

That said, it’s not exclusive. Deep relationships can be built by competitors too, given enough time and sustained investment. The resource is real, but not impossible to replicate.

Process Power: HIGH

BayCurrent’s execution engine may be its most repeatable advantage.

The firm blends strategy with implementation in a way that reduces handoffs, keeps accountability clear, and helps clients actually land change. Combine that with the “one pool” approach to developing and deploying talent and an agile style of service delivery, and you get a set of operating routines that are difficult for competitors to copy quickly—especially in a market where delivery quality and consistency are what clients remember.

XI. The Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

BayCurrent’s rise isn’t just a Japan story or a consulting story. It’s a case study in how compounding works when positioning, execution, and macro timing finally line up.

Timing Meets Preparation

For years, BayCurrent did the unglamorous work: building delivery muscle, earning trust client by client, and putting real infrastructure behind a business that didn’t yet have a sweeping growth narrative. Then Japan’s DX urgency finally flipped from “eventually” to “now,” and BayCurrent was one of the few firms ready to absorb the surge.

This pattern shows up again and again in great businesses and great investments: the winners often look ordinary—right up until the moment the market turns. The hard part is having the patience to keep investing through the quiet years.

The PE Value Creation Model

CLSA Sunrise II is the reminder that private equity can create real value in a people business, not by “financial engineering,” but by upgrading how the machine runs. Operational discipline, tighter governance, and a clearer growth plan helped turn BayCurrent from a solid firm into a scalable one that could withstand public-market scrutiny.

And the timing mattered. The roughly two-year sprint from acquisition to IPO was long enough to professionalize operations without breaking what made BayCurrent work in Japan in the first place. Too short, and the transformation would have been unfinished. Too long, and the firm could have drifted away from the cultural fit that helped it win.

Cultural Moats Matter

BayCurrent’s moat isn’t a patent or a platform. It’s the ability to operate inside Japanese corporate reality—how trust is built, how decisions get made, how consensus forms, and what “good delivery” actually looks like to a Japanese client. That understanding, plus long-earned relationships across industries, creates a narrow but meaningful advantage.

This is also why global consulting giants can struggle in Japan. It’s not a lack of intelligence or frameworks. It’s underestimating how much culture determines what advice gets accepted—and what change actually sticks.

And the broader lesson isn’t limited to Japan: local champions often win for reasons that don’t show up in a spreadsheet. If you only screen quantitatively, you can miss the real source of durability.

The Integration Premium

BayCurrent’s strategy-through-implementation model is valuable because it reduces the failure modes that kill transformations: handoffs between vendors, lost context, misaligned incentives, and the “it sounded great on slides” gap.

When the same firm helps define the plan and then stays to ship it, accountability is clearer, coordination costs drop, and clients often deepen the relationship. In a world where strategy and implementation are frequently split apart, the firms that bridge both tend to earn better work, stickier engagements, and premium economics.

Human Capital as the Product

In consulting, the product goes home every night. Advantage comes from attracting great people, developing them fast, and keeping quality high as you scale—while still billing at levels that make the model work.

BayCurrent’s “one pool” approach is one attempt to balance those pressures. By moving consultants across industries and problem types, the firm can broaden development, stay flexible in staffing, and allocate experienced talent where it matters most. Done well, that can be a recruiting edge and an execution edge at the same time.

Macro Tailwinds + Micro Execution

The 2025 Digital Cliff created urgency and budgets, but it didn’t guarantee BayCurrent would win. Tailwinds draw competitors. What matters is whether the company has the delivery capability and organizational model to convert industry growth into outsized company growth.

For investors, the caution is straightforward: don’t overpay for macro exposure alone. The real question is whether this specific company can consistently take more than its fair share—and keep doing it as the market evolves.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case:

Japan’s digital transformation still looks like it’s in the early innings. By 2025—the very year METI warned could become the “digital cliff”—a large majority of Japanese companies say they’re promoting DX initiatives. And yet only about a third have produced notable results. In other words: awareness is high, spending is happening, but execution is still lagging.

That gap is exactly where BayCurrent thrives.

The underlying constraints haven’t gone away. Legacy systems still need modernization. The IT talent shortage still limits what companies can do in-house. And cultural resistance to big change doesn’t resolve in a quarter or two—it can take years. As long as those frictions persist, demand for outside support stays durable.

There’s also a simple point about firepower. Japanese incumbents are investing in transformation, and many have the balance sheets to fund it. Capital isn’t the bottleneck; capability is. When companies have money to spend but lack the internal talent and operating model to execute, firms like BayCurrent become the bridge between intention and outcome.

Then comes the next wave. AI and generative AI don’t replace the DX agenda—they add to it. As the technology matures, enterprises will need help turning experimentation into real implementation: data foundations, process redesign, governance, security, and change management. That’s another multi-year consulting opportunity layered on top of the legacy modernization cycle.

International expansion adds further optionality. If BayCurrent can follow Japanese clients into ASEAN—and eventually win local clients there too—the company’s opportunity set expands beyond Japan’s mature economy.

And because BayCurrent has operated with premium margins and strong cash flow, it can keep reinvesting in the core inputs that matter in consulting: recruiting, training, thought leadership, and capability development. If managed well, that becomes a reinforcing loop—better talent wins better work, which funds even better talent.

Bear Case:

The biggest risk is concentration. BayCurrent’s customer base is primarily in Japan, so a Japan-specific slowdown would hit harder than it would for globally diversified firms like Accenture.

That lack of geographic diversification matters because consulting demand is cyclical at the margin. A broad economic slowdown in Japan—or a downturn concentrated in key client industries—could quickly translate into delayed projects, smaller budgets, and slower hiring, with limited offset elsewhere.

The second risk is the talent market itself. Consulting is a labor business, and Japan is short on modern IT professionals. If competition pushes wages up faster than BayCurrent can pass costs through to clients, margins compress. This is especially important given how quickly BayCurrent scaled its workforce—from 1,528 employees in 2018 to more than 5,900 by 2025. Growing that fast can strain onboarding, training, and culture, and in consulting, quality is the product.

Competitive intensity could also rise. If global consulting giants like Accenture, Deloitte, or McKinsey decide to make Japan an even higher strategic priority, their resources and brand pull could pressure BayCurrent in both client acquisition and recruiting. BayCurrent’s cultural fit is an advantage, but it isn’t an unbreakable moat.

And finally, even with the DX imperative, enterprises under financial stress can still cut or defer consulting spend. Transformation may be strategically important, but in a downturn it can get pushed out—especially when projects are large, disruptive, and politically complicated.

If BayCurrent’s rapid hiring results in too many less-experienced consultants relative to demand, project execution could suffer. The “open pool” staffing model works best when the pool has enough seasoned talent to deploy to high-stakes work; if that balance shifts, client outcomes—and retention—could follow.

XIII. Epilogue & Future Outlook

As 2025 draws to a close, BayCurrent is back at the familiar edge of a new chapter. It already made the hard leap—from a small IT consulting firm founded in the Lost Decade to a multi-billion-dollar public company built around Japan’s long-delayed modernization. The question now isn’t whether BayCurrent “works.” It’s what, exactly, it becomes from here.

One clue came before the cliff date itself. In September 2024, the company changed its name from BayCurrent Consulting, Inc. to BayCurrent, Inc. Dropping “Consulting” reads like intent: a signal that the business may not want to be defined forever by billable hours alone, and that its ambitions could expand into broader business services, technology products, or other models that scale differently than traditional project work.

Meanwhile, the urgency that powered the last decade hasn’t disappeared just because the calendar flipped closer to 2025. In FY2024, METI established the Legacy Systems Modernization Committee as part of the Priority Plan for the Realization of a Digital Society. The point was straightforward: get an updated view of how widespread legacy systems still are, clarify what’s blocking modernization, and develop measures to push Japanese companies through the logjam as the Digital Cliff approaches.

That matters because it suggests the DX agenda has institutional momentum. Government attention is staying on the problem, which in turn keeps pressure on enterprises to fund and execute multi-year modernization programs. For BayCurrent, that’s a durable tailwind.

Then comes the next wave, and it’s already arriving: artificial intelligence. As Japanese enterprises move from “digitalization” toward AI-enabled operations, they’ll need partners who can do two things at once—understand the technology and understand how change actually gets implemented inside Japan Inc. BayCurrent’s proximity to the Generative AI Japan ecosystem, including Joji Noritake’s role in its governance, signals that the company wants to be early to that shift, not late.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch:

For investors tracking BayCurrent from here, a few indicators will tell you whether the engine is still compounding—or starting to strain:

-

Revenue per consultant (productivity): This is the simplest way to see whether growth is healthy. If headcount rises faster than revenue, it can mean utilization is slipping or the firm is having trouble matching the right talent to the right work.

-

Employee growth versus revenue growth: BayCurrent has scaled aggressively. The key is whether the organization can keep quality and training intact while it grows. If revenue per employee holds steady or improves, scaling is working. If it deteriorates, it’s a warning.

-

Operating margin: In a people business, margins are the report card. Compression can mean pricing pressure, rising labor costs, or internal execution issues. Stability suggests BayCurrent is still keeping its delivery machine sharp.

In the end, BayCurrent is a story about Japan—its unusual approach to IT, its cultural resistance to disruption, and the enormous catch-up effort now underway. For investors, the open question is the same one that hangs over every “secular tailwind” narrative: is this the start of a long, multi-cycle transformation, or a burst of modernization that eventually looks more like normal business spend?

Nobody can know for sure. But the company that began as PC Works in 1998, remade itself under private equity in 2014, and found escape velocity as a public company after 2016 has shown it can evolve with the moment. And in a market where cultural fluency and delivery follow-through still decide who wins, that adaptability may be the most valuable asset BayCurrent has.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music