Yaskawa Electric: The Company That Invented Mechatronics

I. Introduction: Where Robots Come From

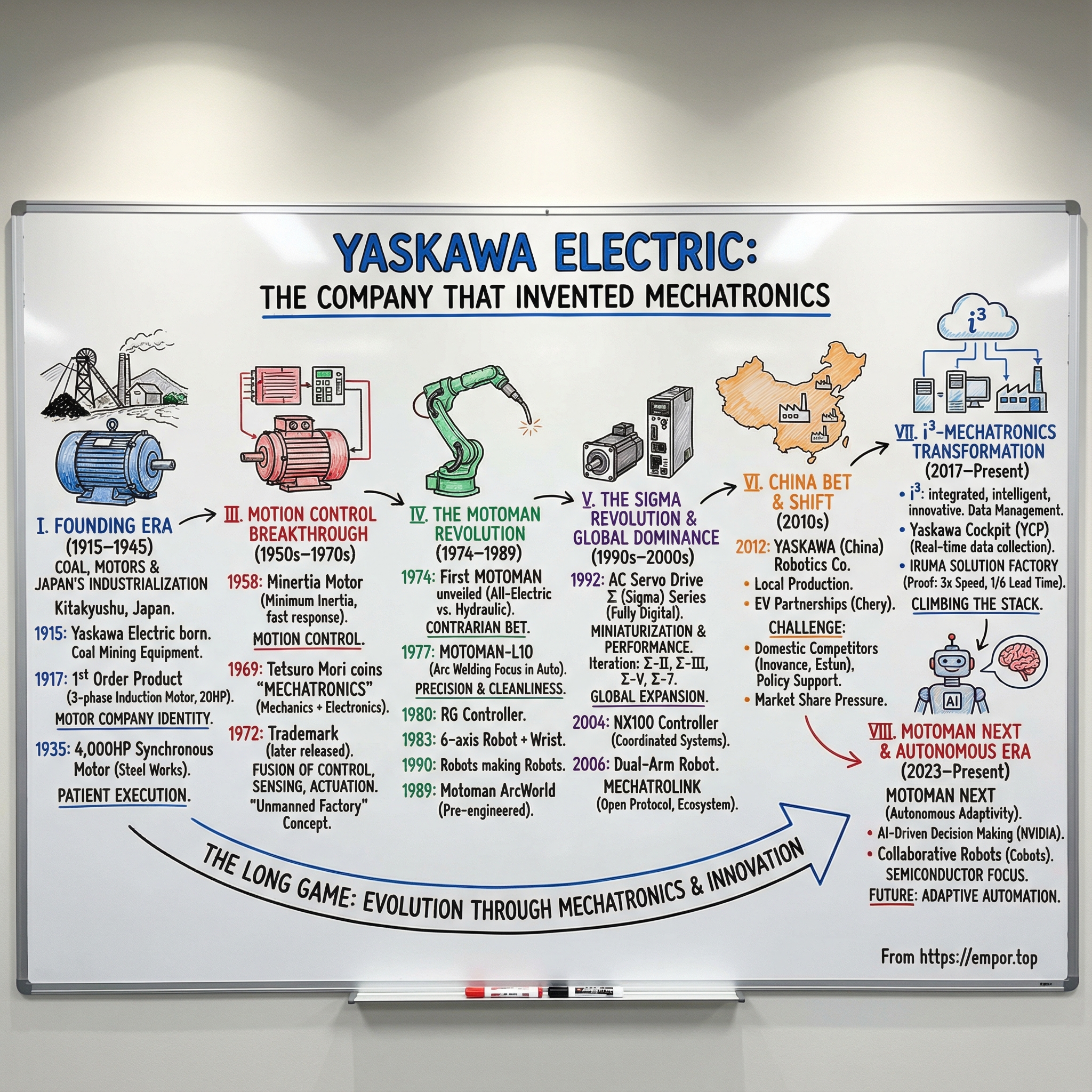

Picture a humid morning in 1969 in Kitakyushu, Japan’s industrial heartland. Inside Yaskawa Electric, a senior engineer named Tetsuro Mori writes a new word on a notepad: “mechatronics.” A mash-up of mechanics and electronics, it captured a simple but radical idea for its time: the future of machines wouldn’t be purely mechanical or purely electrical. It would be the fusion of both—control, sensing, and actuation working as one.

Yaskawa moved quickly to protect the term, applying for a trademark in 1969 and receiving approval in 1972. And then, in a move that still feels unusually generous for a company that could’ve tried to own the category it created, Yaskawa later let the trademark go in the 1980s—choosing not to renew it so the broader industry’s research and adoption wouldn’t be constrained.

That choice is a tell. Yaskawa plays the long game.

The company had been headquartered in Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture since its founding in 1915. Over the next century, it sat at the center of Japan’s industrial transformation—starting in the era of coal and heavy industry, and steadily evolving into something far more precise: the motors, drives, and robots that power modern factory automation.

Today, Yaskawa says it holds the leading global share in AC servo motors and controllers, and that cumulative shipments of its AC servo motors reached 20 million units in 2020. It’s also one of the “big four” industrial robotics companies, alongside FANUC, ABB, and KUKA. Under its MOTOMAN brand, Yaskawa’s robots show up across industries and applications around the world.

Which brings us to the real hook of this story: how did a company that started by serving coal mines in southern Japan become a global automation powerhouse—one that not only built robots, but helped define the very language of the robot age? And now that manufacturing is shifting again, can Yaskawa hold its ground amid intensifying Chinese competition, the ups and downs of the semiconductor cycle, and the coming AI-driven reinvention of industrial robotics?

That’s what we’ll unpack. We’ll follow Yaskawa from its earliest motors to its defining breakthroughs in servo control and robotics, then into the modern era—where “i³-Mechatronics” is the company’s bet on what comes next.

II. The Founding Era: Coal, Motors & Japan's Industrialization (1915–1945)

To understand Yaskawa, you have to start with Kitakyushu. In the early 1900s, this corner of northern Kyushu was Japan’s industrial engine room. Coal mines scarred the hillsides. Steelworks dominated the skyline. The country’s modernization ran, quite literally, on what came out of the ground here.

That’s the world Daigoro Yasukawa built for. In April 1915, with help from his elder brothers, he set up an office in Kurosaki, Kitakyushu—and Yaskawa Electric was born, initially as a maker of equipment for coal mining.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Japan’s industries were electrifying fast, and coal was the fuel behind it all. But mining was brutal and dangerous work. Electric motors changed the equation: they could hoist, ventilate, and move material with less human risk and far more consistency. Yaskawa’s early mission was straightforward—build the machines that made mining safer and more productive.

In 1917, the company delivered its first order product: a three-phase induction motor rated at 20 horsepower. It’s a small detail that matters, because it marks the real beginning of Yaskawa’s identity. From the start, the company wasn’t primarily a “systems” business. It was a motor company—deeply technical, relentlessly focused on turning electricity into reliable, controllable motion. Over the decades, that would evolve into what Yaskawa later called mechatronics: motor technology plus the electronics and control needed to make it precise.

As Japan’s industrial appetite grew, Yaskawa’s motors grew with it. By 1935, it was delivering a massive synchronous motor—4,000 horsepower—for rolling machines at Yahata Steel Works. This was a different class of engineering: not just scaling up, but building the know-how to handle heavy-duty, high-stakes industrial production.

The war years were punishing, but they didn’t erase the company’s long-term ambition. Yaskawa endured World War II and, in 1948, signed its first export contract of the postwar era—an early signal that it wasn’t going to stay a regional supplier forever.

This founding era sets the pattern you’ll see again and again in Yaskawa’s story: patient execution, engineering depth, and a willingness to build the future one layer at a time—starting with the motor.

III. The Motion Control Breakthrough: From Motors to Servo Technology (1950s–1970s)

If the founding era made Yaskawa a motor company, the postwar decades turned it into something much more valuable: a motion control company. A motor converts electricity into rotation. Motion control is the art of telling that rotation exactly what to do—how fast to spin, when to stop, how hard to push, and where to land—over and over, with precision you can build a factory around.

Yaskawa’s big leap arrived in 1958 with the Minertia motor. Even the name is revealing. Long before “mechatronics” entered the vocabulary, Yaskawa was already combining concepts. “Minertia” was their shorthand for “minimum inertia,” a servomotor line designed to start and stop incredibly fast by reducing the rotor’s inertia.

The payoff was dramatic: response speeds that were a hundred times faster than conventional motors of the era. The idea was deceptively simple—make the spinning mass easier to accelerate and brake—and suddenly you can command motion instead of merely producing it. This is the prototype of the modern servo motor, the component that would become Yaskawa’s crown jewel.

Why does that matter in real life? Imagine a robot arm on an electronics line. It has to move quickly to keep throughput high, but it also has to stop exactly where it’s supposed to—no drifting, no overshoot, no wobble—because the part it’s grabbing is tiny and fragile. That kind of precision requires a motor that responds instantly and predictably. Minertia pushed Yaskawa into that world.

Then came the conceptual breakthrough—the one that gave the entire category its name. In 1969, senior engineer Tetsuro Mori coined “mechatronics” inside Yaskawa, as the company was pairing electronic controls with mechanical factory equipment. The word captured what Yaskawa had been building toward all along: manufacturing’s future wouldn’t be mechanical or electrical. It would be both, designed together.

Over time, “mechatronics” broadened beyond servo control. In the 1970s it centered on servo technology and accessible automation—think everyday systems like automatic doors and auto-focus cameras. In the 1980s, the focus shifted toward embedding microprocessors into mechanical systems to improve performance. In the 1990s, communication technology pushed mechatronics into networks—machines connected to other machines, and eventually to entire production systems.

Yaskawa didn’t just coin the word. In the 1960s, it had already begun commercializing electrically driven automatic equipment with names like MOTO fingers and MOTO arms—early hints of what was coming next. And it proposed an “unmanned factory” concept built around a trinity: detector, controller, and actuator working as one integrated system. At a time when factories still leaned heavily on human labor, that was a genuinely radical idea.

This era set the pattern Yaskawa would keep repeating: create a breakthrough in motors and control, define the philosophy that explains why it matters, then execute patiently for decades. Minertia wasn’t just a successful product. It was the foundation under everything that followed.

IV. The MOTOMAN Revolution: Birth of the Japanese Robot Industry (1974–1989)

By the early 1970s, industrial robotics was starting to feel inevitable. In the United States, the dominant machines were hydraulically driven: strong, but loud, messy, and built for brute force more than finesse. Japan began importing those systems and signing technology partnerships to bring them into local factories.

Yaskawa looked at that landscape and made a very Yaskawa decision: instead of licensing someone else’s hydraulics, it doubled down on what it knew better than anyone—electric motors and control.

It was a contrarian bet. Hydraulics had the reputation, the installed base, and the obvious power advantage. But Yaskawa’s engineers believed the next wave of automation wouldn’t be won on raw strength. It would be won on precision, repeatability, and cleanliness—the exact strengths of electric drive systems.

In 1974, at Japan’s Robot Exhibition, Yaskawa unveiled the first MOTOMAN after two years of development. The moment was bold. The reality, at first, was brutal: it didn’t sell. The market wasn’t ready, and many manufacturers weren’t convinced an all-electric robot could compete with the hydraulic machines they were seeing from abroad.

Yaskawa didn’t flinch. It went back to the drawing board and built the MOTOMAN-L10—an articulated robot modeled on an electric articulated-type machine announced by Sweden’s ASEA (today’s ABB). But Yaskawa added its own strategic twist: rather than trying to fight hydraulics head-on across every use case, it targeted a job where electric would shine—arc welding.

That choice wasn’t random. Yaskawa had spent decades building high-quality components and understanding the demands of manufacturing environments where consistency matters. When MOTOMAN entered the market in 1977, the company leaned into welding applications in automobile factories—especially the push to automate and labor-save processes involving parts like underbody assemblies and mufflers. Arc welding rewarded exactly what electric robots could deliver: smoother motion, cleaner operation, and more consistent results without the overhead of hydraulic infrastructure on the factory floor.

Once the wedge was in, Yaskawa started to compound.

In 1980, it released the RG controller, capable of controlling up to six axes and storing programs for up to 1,000 positions. In 1983, Yaskawa introduced the world’s first six-axis robot with an additional wrist axis—more dexterity, better angles, more complex manipulation.

Over time, Yaskawa kept pushing the “more human” direction too: a seven-axis robot that added an extra degree of freedom beyond the standard six, and a dual-arm robot designed to simulate tasks a person would normally do with both arms.

And then came a moment that said as much about Yaskawa’s culture as its technology. In 1990, Yaskawa became the first company in the world to use its own robots to manufacture other robots. It was the purest expression of the company’s thesis: if this is the future of production, prove it by living in it.

By 1989, Yaskawa had taken the next leap—into North America—paired with a product that made adoption easier: the Motoman ArcWorld series, the first line of pre-engineered weld cells. Instead of every customer needing a custom-designed robotic welding setup from scratch, ArcWorld packaged the concept into something closer to a deployable unit. It lowered the barrier, broadened the market, and helped MOTOMAN scale beyond the biggest manufacturers.

The MOTOMAN era turned Yaskawa’s mechatronics philosophy into something tangible: not just motors and control, but machines that could do work—reliably, repeatedly, at industrial scale. And it laid the foundation for what would come next: servo technology so small, fast, and capable that it would spread far beyond robots and into nearly every corner of modern automation.

V. The Sigma Revolution & Global Dominance (1990s–2000s)

If the MOTOMAN era made Yaskawa a credible robotics company, the Sigma era made it a motion-control company on a global scale. In the 1990s, servo motors weren’t just getting better; they were getting smaller, smarter, and more integrated into everything from machine tools to packaging lines. Yaskawa didn’t just ride that shift. It helped define it.

In 1992, Yaskawa commercialized its AC Servo Drive Σ (Sigma) Series—what the company describes as the first fully digital servo system in the industry. The premise was straightforward and powerful: higher performance and functionality, in a smaller package. And it landed. Customers adopted it because it made machines faster, more precise, and easier to design around.

Sigma’s real breakthrough was miniaturization without compromise. With equivalent output ratings, Sigma motors came in at roughly one-third the size and weight of previous models. In a factory, that cascades into everything you care about: more compact equipment, less mass to move, tighter layouts, and more automation packed into the same floor space.

Yaskawa then did what it tends to do: iterate relentlessly. The line progressed through Σ-II in 1997, Σ-III in 2002, Σ-V in 2007, and Σ-7 in 2013—each step improving responsiveness, precision, and integration. Just as important, it created a clear upgrade path: customers could modernize performance over time without treating every generation change like a full rip-and-replace.

Here’s where Yaskawa’s strategy quietly diverged from many of its robotics peers. Yes, it built servo motors for its own MOTOMAN robots. But it also made external sales of servo technology a central pillar—selling into a wide range of OEMs and machine builders across industries. That dual use case mattered. It broadened Yaskawa’s market, diversified its exposure beyond robot cycles, and—maybe most importantly—kept the company close to how real factories were evolving.

As the products spread, so did the company. Yaskawa Electric, founded in 1915 and headquartered in Kitakyushu, expanded into a true global footprint. By the 2000s, it had business hubs in 29 countries, production bases in 12 countries including Japan, and a network of 81 subsidiaries and 24 affiliate companies worldwide. The organization itself grew to support that scale, with 14,709 employees.

On the robotics side, controllers were advancing in parallel. In 2004, Yaskawa introduced the NX100 controller, capable of controlling up to 36 axes. That wasn’t a spec-sheet flex. It was a response to what modern automation cells were becoming: not a single robot doing a single task, but coordinated systems—multiple robots, positioners, conveyors, sensors—all needing synchronized motion.

And in 2006, Yaskawa pushed the form factor of the robot itself with the DA20, a manipulator with two arms. The intent was clear: bring automation into tasks that looked less like repetitive single-tool motion and more like the kind of two-handed work humans do naturally in assembly.

Underneath all of this sat a less flashy, but hugely important investment: interoperability. MECHATROLINK, an open industrial automation protocol originally developed by Yaskawa and now maintained by the Mechatrolink Members Association (MMA), helped make Yaskawa systems easier to connect with equipment from other manufacturers. With more than 2,800 companies registered as MMA members, MECHATROLINK wasn’t just a feature—it was an ecosystem.

This is the compounding engine of the Sigma era. Better servos enable better machines. Better machines expand the installed base. A broader installed base pulls in partners and compatibility standards. And in factories, where equipment is built to run for decades, those choices don’t reset every year. They accumulate—creating long-lived customer relationships, ongoing service and upgrade opportunities, and a moat that’s built as much from integration as it is from pure performance.

VI. Key Inflection Point #1: The China Bet & Global Manufacturing Shift (2010s)

The 2010s forced every industrial automation company to answer the same uncomfortable question: what do you do about China? The country wasn’t just the world’s largest manufacturing base. It was becoming the fastest-growing automation market on Earth—and, increasingly, the birthplace of the competitors you’d be fighting next.

Yaskawa placed its bet early. In 2012, it established YASKAWA (China) Robotics Co., Ltd. (YCR) in Changzhou as its first overseas robot production base. The logic was clear: build where the demand is. Local production meant shorter lead times, lower logistics costs, and a stronger seat at the table as Chinese factories modernized.

And modernize they did. Across China, factory automation demand rose as labor grew scarcer—pressured by demographic shifts like low birth rates and an aging population—and as wages climbed. At the same time, China’s domestic growth strategy pointed investment toward exactly the kinds of industries that eat servos and robots: EV supply chains, 5G infrastructure, and environmental and energy-related buildouts.

Yaskawa also tried to ride the EV wave directly. It teamed up with Chery Automobile to make and sell equipment for electric vehicle production in China, aiming to sell more of its robots and motors into a rapidly expanding market. The partnership included Yaskawa taking a small stake in Chery unit Anhui Ruixiang Industry, though the details weren’t disclosed. The joint venture, Chery Yaskawa E-Drive System Co., was structured as a 45-40-15 partnership between Chery, Yaskawa, and Wuhu Construction Investment Co., the investment arm of the Wuhu city government, with a focus on producing EV motors and control systems.

The broader EV push paid off elsewhere, too. In the automobile market, Yaskawa’s revenue increased thanks to large-scale EV-related projects in South Korea—evidence that its motor and control expertise could travel beyond classic factory automation and into the electrified drivetrain ecosystem.

But the China bet came with a downside that got harder to ignore each year: China wasn’t just a market. It was building its own champions—and policy increasingly favored them. Yaskawa warned that its market share in robots and servo motors would deteriorate in China as government policy supported local factory automation players. Companies like Inovance began taking meaningful share.

The shift shows up in the mix of who actually sells robots in China. In 2024, 52% of industrial robots sold in China were made by domestic manufacturers, up from 47% in 2023. FANUC remained the largest single player with 11% market share, but Chinese company Estun was close behind at 9.5%.

Inovance is the more direct threat to Yaskawa’s core. Founded in 2003 by former Huawei engineers, it started in frequency converters and servo systems—then entered industrial robots in 2016. In less than a decade, it climbed to become China’s second-largest domestic robot manufacturer, reaching an 8.8% market share in 2024. Its rise was powered by exactly the playbook Yaskawa knows well: motion control depth plus automation integration.

And it wasn’t just robots. Inovance’s servo motors captured 23% of the Chinese market in 2024, surpassing Siemens and Yaskawa—an especially sharp development given how central servo leadership is to Yaskawa’s identity.

Even in the robot counts, the momentum was visible. Estun—the leading domestic maker of multi-axis industrial robots—sold over 17,000 robots in China last year. That was fewer than FANUC and KUKA, but already more than ABB and Yaskawa.

For investors, this is the China story in one frame: Yaskawa was directionally right to localize production and pursue EV partnerships. But China’s rise also created a structural headwind—domestic competitors, backed by policy tailwinds, coming straight at Yaskawa’s strongest product categories in the world’s most important manufacturing market.

VII. Key Inflection Point #2: The i³-Mechatronics Transformation (2017–Present)

China was a reminder that hardware advantages don’t stay exclusive forever. So Yaskawa’s next move was to climb the stack.

Nearly 50 years after Tetsuro Mori coined “mechatronics,” Yaskawa introduced its sequel: i³-Mechatronics. If mechatronics was the fusion of mechanics and electronics, i³-Mechatronics adds a third ingredient—digital data management—built for the Industry 4.0 era.

Yaskawa had been steadily evolving its mechatronics philosophy for decades, but in 2017 it formalized the shift into a global solution concept: i³-Mechatronics. The “i³” stands for integrated, intelligent, and innovative—three ideas Yaskawa positions as the key to solving customers’ management problems, not just their automation problems.

The core idea is simple, but the implications are big. It’s not enough to automate individual “cells” on a factory floor. You also have to manage them—using digital data to understand what’s happening, in real time, across an entire production system. In Yaskawa’s framing, the goal is to run a factory on “numerical values,” not “expert knowledge”: track equipment operation through process data, track production through status data, and turn what used to live in veteran engineers’ heads into something measurable, shareable, and improvable.

That’s the shift from automation as a one-time engineering project to automation as a living system—something you can continuously tune, optimize, and eventually hand off to AI-driven decision-making.

The centerpiece of this software layer is Yaskawa Cockpit (YCP). Yaskawa describes its key features as the “collection, accumulation and analysis” of data through visualization. Practically, that means YCP can connect to a wide range of devices on the factory floor—including equipment from other companies—pulling their data into a common timeline. By aligning time-series data with synchronized timestamps, Yaskawa says it can collect and coordinate information in units of one-millionth of a second.

That microsecond-level resolution is the difference between “we saw a problem after the fact” and “we can trace exactly what happened, when it happened, and what upstream event triggered it.” In modern manufacturing—where tiny timing mismatches can create defects, downtime, or yield loss—time alignment isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the whole game.

And Yaskawa didn’t want this to live as a slide deck. It wanted proof.

So it built the Iruma Solution Factory: a real operating plant where Yaskawa would apply i³-Mechatronics to its own production. The Iruma site had been developing and manufacturing servo motors, servo amplifiers, and controllers for more than 50 years. It already used Yaskawa’s own servos, controllers, robots, and AC drives to advance automation. The new step was to add digital data management on top—turning automation into an integrated system that could adapt more flexibly to changing production needs.

The impact, Yaskawa says, was dramatic. In production of Σ-7 Series AC servo drives, speed and efficiency tripled versus conventional production, and lead time fell to one-sixth of what it had been. i³-Mechatronics was also used to analyze defects, identify root causes, and implement preventive maintenance. Alongside the lead-time reduction, Yaskawa says the number of workers required for assembly dropped to one-third of the prior level.

Since then, Yaskawa has kept pushing this architecture outward into products customers can deploy. In September 2024, it launched the iC9200, a controller designed to control multiple devices—like servos and robots—in a single unit. Yaskawa positions it as a platform to accelerate global i³-Mechatronics adoption, including support for communication networks widely used in Europe and the United States.

For investors, i³-Mechatronics is Yaskawa attempting to build a software and services layer on top of a massive installed base of hardware. The playbook is familiar: sell the robots, servos, and drives—then monetize performance over time through data, analytics, and optimization. The open question is execution. Can Yaskawa turn a century of hardware excellence into durable, recurring software-style economics without losing focus on what made it dominant in the first place?

VIII. Key Inflection Point #3: The MOTOMAN NEXT & Autonomous Robotics Era (2023–Present)

If i³-Mechatronics was Yaskawa climbing from hardware into data, MOTOMAN NEXT is what it looks like when that strategy comes back down to the factory floor as a product.

In December 2023, Yaskawa launched the MOTOMAN NEXT series: five industrial robot models, spanning payloads from 4 kg up to 35 kg. Yaskawa positions the line as the first in the industrial robot industry to bring autonomous adaptivity—robots that can perceive their surroundings, make judgments, and adjust how they work as conditions change.

That claim matters because it targets the stubborn gap in factory automation. Plenty of production has been automated for decades, but there are still “unautomated areas” where humans remain essential: parts with inconsistent states, shapes, and sizes; frequent changes in work order; interruptions and exceptions that don’t fit a rigid script. These are the messy edges of manufacturing, where traditional robots can struggle.

MOTOMAN NEXT is built as a direct challenge to that messiness. The goal is for the robot to understand the situation, decide on an approach, and execute the task in an optimal way—pushing automation into places that used to require human judgment.

Under the hood, Yaskawa tied this next-generation robot platform to the modern AI stack. MOTOMAN NEXT robots are powered by NVIDIA Isaac accelerated libraries and AI models, running on NVIDIA Jetson Orin autonomous control units (ACUs) with Wind River Linux. The intent is straightforward: bring integrated AI processing closer to the robot so it can make decisions locally, enabling higher levels of autonomy.

The platform also broadens the portfolio around a single architecture. Alongside the five industrial robots—NEX4, NEX7, NEX10, NEX20, and NEX35—Yaskawa pairs two collaborative robots, NHC12 and NHC30. Across the lineup, each robot uses the compact YNX1000 controller.

This is Yaskawa’s response to the cobot wave. Instead of treating collaborative robots as a separate category defined mainly by safety features and ease of deployment, Yaskawa is framing the next phase as intelligence and adaptivity: robots that can cope with variability, not just repeatability.

That positioning fits the demand pull in the market. With declining working-age populations, worsening labor shortages, and heightened focus on preventing the spread of infectious diseases, automation demand has broadened beyond automotive into general industry. Yaskawa has pointed to growth in the so-called 3P markets—food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics—and the 3C markets—computers, home appliances, and telecommunications equipment. To meet those needs, it began expanding human-collaborative offerings with products like the MOTOMAN-HC 10 DT, launched in 2018, designed to work alongside factory employees.

Zooming out, the scale behind all of this is no longer hypothetical. Yaskawa announced that cumulative shipments of MOTOMAN reached 500,000 units in February 2021. Since then, shipments have continued to grow, with over 600,000 units now installed globally.

And looming behind the product narrative is an end-market that plays directly to Yaskawa’s strengths: semiconductors. The company’s exposure to the semiconductor industry is one reason it’s expected to outgrow other members of the “big four” robotics group. Sales of semiconductor wafer transfer robots were firm, and as AI datacenter buildouts and reshoring initiatives push more semiconductor capital expenditure, Yaskawa’s clean-room robotics and precision motion control sit in the right place at the right time.

IX. The Business Model & Competitive Moat Analysis

If you want to understand why Yaskawa has stayed relevant across a century of industrial change, you have to look past individual products and into the structure of the business. Two lenses help here: Porter’s Five Forces for the industry dynamics, and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers for the sources of durable advantage.

The Yaskawa Flywheel

Yaskawa’s core advantage starts with vertical integration. It makes the motion-control components that matter most: servo motors, drives, and controllers. Those aren’t just parts; they’re the nervous system of a robot, and the difference between a machine that moves and a machine that moves precisely, reliably, and fast.

That creates a flywheel with a very Yaskawa shape to it. Develop servos and controllers in-house → put them into Yaskawa’s own robots and systems → learn from real-world manufacturing and service → feed that learning back into the next generation of motors, drives, and controllers → sell those components externally into a wide range of applications → collect even more edge-case data and requirements → improve the platform again.

The compounding effect is the key. Pure robot companies that buy motors don’t get the same component-level learning. Pure motor companies that don’t build end systems don’t see the full-stack problems customers are trying to solve. Yaskawa gets both.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Industrial robotics isn’t a market you stroll into. The barriers aren’t just capital and factories; they’re decades of accumulated application know-how, safety certification, reliability engineering, and global support infrastructure. But China has shown how those walls can be lowered in specific markets when policy and scale align. Inovance is a good example: founded in 2003 by former Huawei engineers, it started with frequency converters and servo systems, entered industrial robots in 2016, and still climbed rapidly to become China’s second-largest domestic robot maker. Government-backed competitors can compress timelines that would otherwise take a generation.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

This is where Yaskawa’s structure shines. Because it produces its own servo motors, drives, and controllers—the strategically critical components—supplier leverage is muted. Yaskawa isn’t hostage to a third party’s pricing, roadmap, or delivery constraints in the way many integrators and robot-only players can be.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Big customers have influence, especially automotive OEMs that buy at scale and can run competitive bids. But once robots, servos, and controllers are designed into a line, the cost of switching is painful: retooling, reprogramming, validation, retraining, downtime. In semiconductors, the buyer side looks different—fabs demand extreme precision and uptime, and there are simply fewer credible options at the top end of performance.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

The substitute for automation is human labor, and the trend line is not friendly to humans as the “default” solution. Aging populations, tighter labor markets, and rising wages make robots and motion control more attractive over time. COVID-19 also reinforced a lesson manufacturers already knew but didn’t always act on: labor-dependent production carries operational risk.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Industrial robotics is brutally competitive at the top. The market is dominated by four major brands—FANUC, KUKA, ABB, and Yaskawa—and each has a distinct historical strength: ABB in control systems, KUKA in system integration and robot manufacturing, FANUC in numerical control systems, and Yaskawa in servo motors and motion control.

Yaskawa’s robot characteristics reflect its origin story. Because it started with the motor, it built its robotics platform around motion performance and stability—traits that translate into strength under load and at speed. That helps explain why Yaskawa has been well-positioned in heavy-duty applications, including large portions of the automobile industry.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Yaskawa introduced Japan’s first all-electric industrial robot under the MOTOMAN brand in 1977, and over the decades it shipped nearly 500,000 units worldwide. That scale matters because it spreads R&D and platform development across huge volumes, and it supports a global footprint that can optimize production regionally.

Network Effects: MODERATE

MECHATROLINK, the open industrial automation protocol originally developed by Yaskawa and now maintained by the Mechatrolink Members Association (MMA), brings ecosystem gravity. With more than 2,800 member companies, compatibility expands the universe of devices that can plug into Yaskawa-oriented systems. These are real network effects, though still more modest than what you’d see in pure software platforms.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Yaskawa has long treated external sales of servo technology as a central strategy, not a side hustle. Many competitors primarily keep servo tech in-house to differentiate their robots. For them to match Yaskawa’s position, they’d risk undermining their own robotics advantage. That’s classic counter-positioning.

Switching Costs: STRONG

Once a factory standardizes on a control environment and layers in tools like i³-Mechatronics and Yaskawa Cockpit, the costs to switch stack up fast. It’s not just hardware replacement; it’s process qualification, engineering workflows, operator training, spare parts strategy, and years of accumulated familiarity. In industrial settings, inertia isn’t a metaphor. It’s a moat.

Branding: MODERATE

MOTOMAN is a well-known name in industrial automation, even if B2B equipment branding doesn’t behave like consumer markets. Yaskawa has also reinforced its identity over time, including updating its corporate logo and image around its 100-year milestone to signal continuity and evolution.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Yaskawa didn’t just participate in mechatronics; it coined the term and even trademarked it (before later releasing the trademark). More importantly, it has decades of accumulated motion-control IP and application knowledge—hard-won expertise that doesn’t compress easily, even for fast followers.

Process Power: STRONG

Yaskawa can point to its own factories as proof. In producing Σ-7 Series AC servo drives, it reported triple the speed and efficiency of conventional production and lead time cut to one-sixth. That’s process power you can sell with credibility, because it isn’t theoretical. It’s how Yaskawa builds Yaskawa.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The bull case for Yaskawa is a story about tailwinds that aren’t going away—and a company that’s built to surf them.

First, the global labor shortage isn’t a blip. It’s structural. Across developed economies, working-age populations are shrinking, and manufacturers are under pressure to do more with fewer people. That demand has already expanded well beyond automotive into general industry, and it tends to persist even when the macro gets choppy. If labor is the constraint, automation becomes the release valve.

Second, semiconductors play directly to Yaskawa’s strengths. Compared with other members of the “big four” robotics group, Yaskawa is more exposed to semiconductor manufacturing—an end market where precision motion control and reliability aren’t “nice to have,” they’re table stakes. As major economies pour money into domestic chip capacity, the opportunity isn’t just more robots. It’s more high-spec robots and high-end servo systems—the part of the market where Yaskawa tends to be strongest.

Third, the EV transition creates new categories of factory demand. Battery electric vehicles don’t just reshuffle what gets built; they reshuffle how factories get built. Yaskawa has already moved to position itself, including partnerships like the one with Chery, to sell motors, control systems, and automation into that expanding production footprint.

Fourth, i³-Mechatronics is a real attempt to change the economics of the business. Hardware is great—until it gets competed away. A hardware-plus-software model can mean stickier customers, more services pull-through, and the possibility of better margins over time, even if unit growth isn’t spectacular. The question is execution, but the direction is strategically sound: climb the stack, and keep value as the market commoditizes.

Fifth, MOTOMAN NEXT hints at a larger market than traditional robotics has been able to reach. Even today, many production tasks remain “unautomated” not because robots can’t move, but because real work is messy—parts vary, setups change, and humans constantly make small judgments. If adaptive, AI-enabled robots can handle more of that variability, the addressable market expands from repeatable tasks to judgment-heavy work. That’s the kind of step-change that can remake growth curves.

The Bear Case

The bear case is just as clear: China and cyclicality.

The biggest structural risk is China. Yaskawa has warned that its market share in robots and servo motors will deteriorate there as policy favors local factory automation champions—and those champions keep getting better. This isn’t a “bad quarter” problem. It’s an industrial policy reality, with competitors like Inovance taking share in exactly the categories Yaskawa cares most about.

You can see it in the market mix. In 2024, a majority of industrial robots sold in China were made by domestic manufacturers, up from the prior year. That trend doesn’t have to go to 100% to hurt. Even steady incremental gains by domestic players can pressure pricing, limit growth, and gradually erode foreign incumbents’ position in the world’s most important manufacturing market.

Second, semiconductors—one of the bull case pillars—also create earnings volatility. When chipmakers pause capital spending, orders and revenue can soften quickly. Yaskawa has already experienced periods where revenue fell from the prior fiscal year, and operating profit declined as the semiconductor recovery proved less robust than hoped, despite cost-reduction efforts.

Third, currency adds another layer of noise. Yaskawa reports in yen, but sells globally. Movements in the dollar, euro, and yuan can swing reported results in ways that don’t always reflect underlying operational performance.

Fourth, the collaborative robot market is getting crowded. In China, domestic manufacturers are particularly strong in cobots, supplying the overwhelming majority of the local market. At the same time, AI-first entrants are trying to redefine what “easy automation” means. If the market shifts from classic industrial robotics toward more software-defined, vision- and AI-driven systems, incumbents have to evolve quickly—or risk being boxed into mature segments.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For long-term investors, two operating signals tell you most of what you need to know:

-

Orders by Region — Watch China versus the Americas and Europe. If growth outside China holds up while China stays sluggish, that’s Yaskawa successfully de-risking its geography. If weakness spreads globally, the story shifts from “China headwind” to “cycle and competitiveness.”

-

Motion Control Segment Operating Margin — This is where Yaskawa’s core advantage should show up. If margins expand, it suggests pricing power, mix improvement, and possibly early evidence that i³-Mechatronics is creating higher-value software and services pull-through. If margins compress, it’s often a sign of price pressure—especially from Chinese competitors—in the servo and drive stack.

Financial Snapshot

In 2024, Yaskawa Electric reported revenue of 537.68 billion yen, down from 575.66 billion yen the previous year. Earnings were 56.99 billion yen, up year-on-year.

As of 31-Aug-2025, Yaskawa Electric’s trailing twelve-month revenue was reported at $3.6B, and its market capitalization was $6.17B.

Recent quarters have been mixed. Yaskawa cited softer-than-expected orders, driven in part by adjustments in semiconductor-related capital investment in South Korea and a temporary wait-and-see pause in investment during the U.S. presidential election—enough to prompt a revision to its annual forecasts.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

Two housekeeping items matter for interpreting results. First, Yaskawa’s fiscal year ends in February, which can make calendar-year comparisons messy. Second, it reports under IFRS, and its segment disclosures have shifted, including PV inverter products being reclassified from System Engineering to Motion Control in fiscal 2024.

No major legal or regulatory overhangs are disclosed in the information here, but geopolitics remains a background risk—especially as Japan-China trade relations continue to sit under periodic strain.

The Long View

Yaskawa is, at its core, a company that has managed to reinvent its products without abandoning its identity. It started with motors for coal mines, helped define mechatronics, built one of the world’s major robotics franchises, and is now trying to fuse industrial hardware with data and AI.

The investment question is whether it can pull off three transitions at once: diversify growth beyond China, keep pace with AI-enabled robotics and the expanding definition of automation, and evolve from a hardware-centric business into one with meaningful software and services upside.

Yaskawa’s history argues in its favor. Patience, technical depth, and an unusually consistent focus on motion control have carried it through more than a century of industrial change. The uncertainty is whether that playbook holds in a world where Chinese competition can scale at unprecedented speed, and where AI is compressing product cycles.

Still, Yaskawa sits in a rare position. It isn’t just a participant in modern manufacturing—it helped name the era. If i³-Mechatronics and MOTOMAN NEXT are the next expression of that legacy, the company will remain a major force in how the world makes things for a long time to come.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music