Fuji Electric: The Century-Old Japanese Giant Powering the Green Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

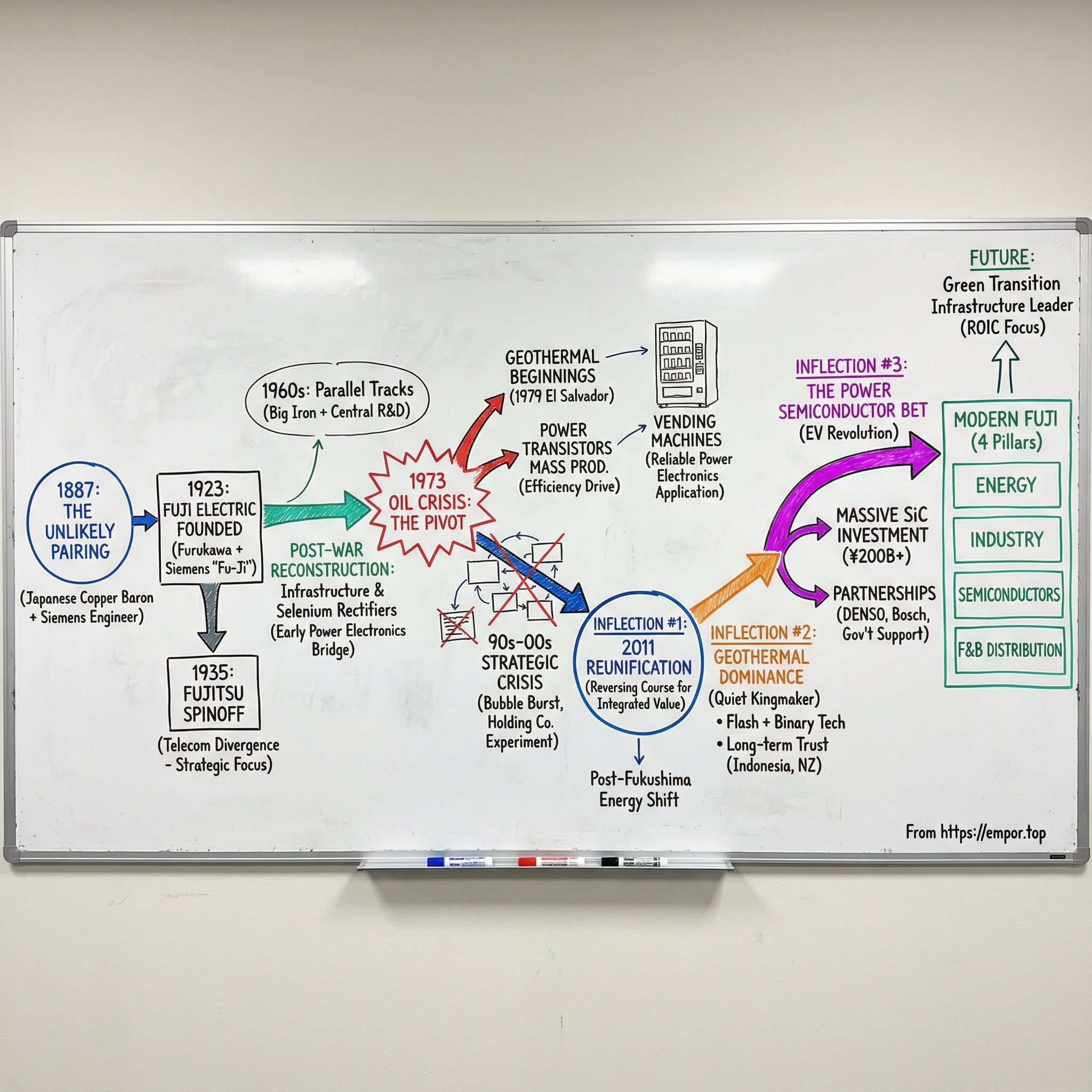

It starts with an unlikely pairing: a Japanese copper baron and a German engineer, crossing paths in the remote mountains of northern Japan in 1887. Out of that one relationship, and the industrial web it created, would eventually come not one but multiple major companies—including Fujitsu, one of Japan’s defining technology giants—and another firm that, a century later, would quietly become a global kingmaker in clean energy.

And here’s the twist: the same company that builds mission-critical hardware for power plants also makes the components inside Japan’s bullet trains—and yes, even the vending machines that line Tokyo’s streets.

That company is Fuji Electric.

Fuji Electric was established in 1923 as a capital and technology tie-up between Furukawa Electric, a spinoff from the Furukawa zaibatsu, and Siemens AG. Even the name carries the origin story: “Fu” from Furukawa and “Ji” from Siemens, reflecting how Siemens is rendered in Japanese. It sounds like Mount Fuji—iconic, unmistakably Japanese—yet it’s actually a compact symbol of an early, deeply cross-cultural partnership.

On paper, Fuji Electric is a diversified electrical equipment manufacturer: pressure transmitters, flowmeters, gas analyzers, controllers, inverters, pumps, generators, ICs, motors, and power equipment. In reality, that bland list hides something far more interesting: a company that has learned how to survive for a hundred years by continually rebuilding itself around the next wave of electrification.

Start with geothermal. Since 2000, Fuji Electric has held the world’s largest share of geothermal steam turbine orders, and it has received orders for 84 units in Japan and overseas totaling 3,469 MW. That’s not just “participating” in the energy transition—it’s supplying the turbines that turn heat beneath the earth into reliable, always-on renewable power.

Then there’s semiconductors—the unglamorous, indispensable layer beneath everything electric. Fuji Electric is one of the five major global makers of IGBT power modules, alongside Infineon, Mitsubishi Electric (Vincotech), Semikron Danfoss, and StarPower Semiconductor—a small club that collectively accounts for about 70% of the market. And recently, Fuji Electric signaled how seriously it takes the next chapter: a major investment into silicon carbide power semiconductors, in partnership with automotive supplier DENSO under a government-backed effort to compete in the global race led by Infineon.

This is the story of how a century-old Japanese industrial company reinvented itself—again and again—and why its current position at the intersection of renewable power and next-generation power chips makes Fuji Electric one of the most quietly consequential companies in the modern energy economy.

II. Founding & The German-Japanese Alliance (1923-1935)

The Copper King and the German Engineer

To understand Fuji Electric, you have to start with the Furukawa zaibatsu—and the man who built it.

Ichibei Furukawa was born in Kyoto in 1832 to a lower middle-class family that could only afford him a basic education. He didn’t look like a future industrial titan. But over the following decades, he became one, founding what grew into one of Japan’s major industrial conglomerates, spanning metals, chemicals, and electrical goods.

The turning point came in 1877, when Furukawa took over the Ashio Copper Mine. He didn’t just operate it—he modernized it. He pushed machinery into production, moved faster than peers to adopt electric lights and power in mining, and built some of Japan’s earliest coke ovens. This blend of ambition and technical curiosity earned him a nickname that stuck: the “Copper King of the Meiji period.”

Then, in 1887, the outside world quite literally came to him.

Hermann Kessler, an electrical engineer dispatched from Siemens—then a dominant force in electrical equipment—arrived in Japan to scout opportunities. He made his way to the Ashio Copper Mine, deep in the mountains, where transportation infrastructure was sparse and roads were still incomplete. Kessler studied the mine’s conditions, but more importantly, he talked: about electricity, about modern industrial systems, about what Siemens equipment could do.

Furukawa listened. And that mattered.

Because this wasn’t a one-off sales pitch. It was the beginning of a relationship—and a mindset—that would shape the next half-century of Japanese electrification. The seeds were planted in a remote copper mine. It would take decades for them to bloom into a new company.

The Birth of Fuji Electric

By the early 1920s, Japan was industrializing at full speed—and running into a constraint that shows up in almost every fast-growing economy: infrastructure. Factories, railways, mining, steel, chemicals—none of it scales without reliable electrical equipment. The zaibatsu system could supply capital and coordination, but much of the advanced electrical know-how still lived in Europe, especially at firms like Siemens.

After World War I, the global economy slid into a downturn. Negotiations were heavily scrutinized, and competition was fierce—many companies wanted to be the Japanese partner that brought Siemens technology into the country. Still, Furukawa Electric and Siemens ultimately struck both a capital and technical alliance. On August 29, 1923, they established Fuji Electric Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (now Fuji Electric Co., Ltd.).

The timing was almost absurd.

Three days later, the Great Kanto Earthquake leveled Tokyo and Yokohama. Public infrastructure collapsed, including major telecommunications facilities. A catastrophe—except it also triggered urgent rebuilding, and rebuilding required exactly the kinds of products the new company was designed to make.

Fuji Electric existed to turn technological cooperation into industrial output. About a year and a half after founding, it began production at a new factory in Kawasaki, near Tokyo. The early lineup was a direct response to Japan’s needs: motors, transformers, generators, circuit breakers, measuring instruments—and yes, telephones. In 1930, Fuji started manufacturing mercury-arc rectifiers, and by 1933 it had added porcelain expansion-type circuit breakers.

Then came another partnership that quietly widened Fuji Electric’s trajectory.

A second technical agreement—this time with the German company Voith—led to a production agreement for Voith’s 4,850-horsepower Francis turbines. It was Fuji Electric’s first real step into turbine technology. At the time, that looked like just another industrial product line. In hindsight, it was the start of a capability stack that would eventually make Fuji Electric a global leader in geothermal power generation.

Even this early, you can see the company’s enduring pattern: find the inflection point, partner with the best in the world, and embed that know-how into Japan’s industrial engine—then keep building from there.

III. The Fujitsu Spinoff: Giving Birth to a Tech Giant (1935)

The Strategic Decision That Created a Fortune 500 Company

Fuji Electric was only twelve years old when it made a decision that would echo through Japanese industry for the next century.

As the Furukawa–Siemens partnership pushed Fuji Electric deeper into heavy electrical machinery—turbines, generators, transformers—one part of the company was heading in a very different direction: telephony. So in 1935, Fuji Electric carved out its telephone division and turned it into a standalone company: Fujitsu.

This wasn’t a quick financial engineering move. It was a strategic admission that “electricity” wasn’t one market. Heavy machinery and telecommunications might share engineering roots, but they were diverging fast: different customers, different product cycles, different capital needs, and different talent. Trying to run both under one roof would eventually mean optimizing for neither.

Fujitsu was established on June 20, 1935, under the name Fuji Telecommunications Equipment Manufacturing (富士電気通信機器製造, Fuji Denki Tsūshin Kiki Seizō), as a spin-off from Fuji Electric. At the time, the new company started with about 700 employees.

And in hindsight, look at what Fuji Electric let go.

Fujitsu grew into a Japanese multinational information and communications technology equipment and services company, headquartered in Kawasaki, Kanagawa. By 2021, it was the largest IT services provider in Japan and the world’s sixth-largest by annual revenue. Few corporate spin-offs—anywhere—have turned into something that consequential.

The Lesson for Industrial Conglomerates

The Fujitsu spin-off is a clean lesson in corporate self-awareness: sometimes the best way to build long-term value is to separate businesses before the divergence becomes a fight.

Fuji Electric’s leadership could have made the classic conglomerate argument. Both businesses were “electrical.” Both were industrial. Both benefited, at least indirectly, from the Siemens relationship. On paper, keeping them together might have looked like synergy.

Instead, they treated strategy like a choice. They recognized that telecommunications was becoming its own universe—and that forcing it to compete for attention and resources inside a heavy-machinery company would limit its upside. Just as importantly, it would distract Fuji Electric from building the deep, compounding capabilities that would later define it.

That decision also hints at the larger legacy of the Furukawa industrial web. Today, the predominant companies in the Furukawa Group include Fuji Electric, Furukawa Electric, Fujitsu, FANUC, and Advantest—an astonishing lineup of industrial champions, with roots that trace back to Ichibei Furukawa’s copper empire and the German-Japanese alliance that created Fuji Electric in 1923.

IV. War, Occupation & Reconstruction (1942-1960)

The War Years

By the late 1930s, Japan was mobilizing its entire industrial base. Fuji Electric—by then a meaningful supplier of heavy electrical equipment—didn’t have the option to sit on the sidelines.

As the government tightened central control, Fuji Electric was pulled into closer coordination with other Furukawa-related manufacturing interests. The company expanded fast, building new factories in Matsumoto, Fukiage, Tokyo, and Mie between 1942 and 1944. They were brought online immediately, turning out a wide mix of products geared toward the war effort.

Then came the collapse. In the final year of the war, those same factories were heavily bombed. The damage wasn’t cosmetic—it effectively crippled the company’s ability to produce.

When the war ended in 1945, Fuji Electric was placed in government custody while military investigations were conducted. Only after that process could the company begin the slow, staged work of restarting production, repairing facilities, and finding its footing in a shattered economy.

The occupation period was uncertain for nearly every Japanese industrial firm, especially ones with zaibatsu ties. Despite its connections to the Furukawa zaibatsu, Fuji Electric survived—though the old zaibatsu structures themselves were formally dissolved.

Rebuilding Japan's Infrastructure

Reconstruction became Fuji Electric’s next proving ground. Japan needed power, measurement, and industrial equipment—practical things that made factories run and cities work again. Fuji focused on the kinds of products that fit that moment.

Then, in 1954, it found a breakout opportunity. Japanese households were rapidly buying televisions and radios, and those devices required reliable ways to convert alternating current into direct current. Fuji Electric began mass-producing selenium rectifiers—simple, essential components that sat quietly inside the consumer electronics boom.

The timing was perfect. Fuji Electric went from competing in the category to dominating it, capturing roughly 80–90% of the domestic selenium rectifier market.

In hindsight, this mattered for more than the postwar revenue. Selenium rectifiers were an early bridge between Fuji Electric’s heavy-electrical roots and the semiconductor future—a first major step into the world of power conversion components that would, decades later, become one of the company’s defining strategic pillars.

V. Nuclear Ambitions & The Research-Led 1960s

Japan's Energy Problem

By the mid-1950s, Japan’s postwar recovery had turned into something bigger: a sprint toward mass industrialization. But the country had a structural weakness it couldn’t engineer its way around overnight—energy. Japan had limited domestic resources, relied heavily on imported fuel, and while its rivers could support hydroelectricity, hydropower alone couldn’t keep an expanding industrial economy running.

So Japan looked for a new base-load answer. Nuclear power, in that era, promised exactly that: dense energy, stable output, and less dependence on imports. Fuji Electric moved to make sure it wasn’t just watching this shift from the sidelines. In 1956, it joined the Daiichi Atomic Power Industry Group, a consortium of 22 companies formed to bring nuclear generation to Japan through a mix of technology development and licensing.

The outcome was historic: Japan’s first nuclear power plant, the 166-megawatt Tokai Nuclear Power Plant, which went online in 1960.

Dual Development Strategy

What’s striking about Fuji Electric in the 1960s is that it didn’t bet the company on one future. It built two, in parallel.

On one track, Fuji Electric went bigger and heavier—engineering large power equipment like transformers and generators, along with propulsion equipment for ships and trains. On the other, it pushed into the smaller, faster-moving world of electronics, developing diode and miniature circuit technologies that would eventually become central to modern power conversion.

In 1964, Fuji Electric formalized that second track by establishing its Central Research Laboratory. This wasn’t a symbolic move. It marked a shift in posture: from primarily importing and adapting leading-edge technology to building proprietary capabilities in-house.

The company’s physical footprint expanded to match its ambitions. New factories in Chiba, Kobe, and Suzuka came online to manufacture heavy transformers, control systems, switchgears, and motors—each one a reflection of Japan’s soaring industrial demand, and Fuji Electric’s growing role in meeting it.

VI. The Oil Crisis Pivot: Energy Efficiency & Geothermal Beginnings (1970s-1980s)

The 1973 Shock That Changed Everything

In 1973, the oil crisis landed in Japan like a hard stop. For a country with virtually no domestic oil, the shock wasn’t just about higher prices—it was about vulnerability. And for companies that made the guts of industrial society run, it forced a new question: what does “electrification” look like when energy itself is scarce?

For Fuji Electric, this became a strategic pivot point. The company pushed hard into energy saving and “new energy” technologies, adding solar cells and fuel cells to its development pipeline. But the most important signal came from a market that barely existed at the time: geothermal.

Fuji Electric received its first order for overseas geothermal power generation equipment, and the company later traced the emergence of the geothermal market to 1979, when it delivered turbines for a geothermal project in El Salvador. From there, Fuji Electric built credibility as a geothermal steam turbine generator supplier, particularly for projects in California in the United States.

Power Electronics Breakthrough

The same oil shock that made geothermal attractive also supercharged something even more foundational: power electronics—the behind-the-scenes technology that turns electricity into usable, efficient motion, heat, and control.

In 1975, Fuji Electric began manufacturing power transistors—one of the first companies in the world to produce them at scale. These components made it possible to convert and control power far more efficiently, directly aligning with what the post-crisis world suddenly demanded: get more output from every unit of energy.

The Five-Division Structure

By the late 1980s, Fuji Electric had grown into a diversified conglomerate split into five major groups. The electric machinery group handled plants and heavy machinery. The systems group covered instrumentation, information systems, and mechatronics, including robots and data processing equipment. The standard machinery and apparatus group made programmable controllers, heavy motors, and magnetic devices. The electronics group produced large diodes, transistors, circuits, computer components, and measuring equipment. And then there was the vending machine and appliance group, building vending machines and large refrigerator display units.

That last category can sound like a detour—until you think about what a modern vending machine actually is. It’s refrigeration, power conversion, sensors, and control systems wrapped into a box that has to run reliably in public, year after year. In other words, it sits right at the intersection of the capabilities Fuji Electric had been compounding for decades.

And in Japan—where vending machines are part of the streetscape—Fuji Electric became a major player. According to the Japan Vending Machine Manufacturers Association, the company holds about 30% of Japan’s vending machine market.

VII. The Lost Decades & Strategic Crisis (1990s-2003)

Japan's Bubble Burst

When Japan’s bubble economy popped in 1990, it didn’t just take down real estate prices and stock portfolios. It froze the gears of Japanese industry.

For a diversified industrial conglomerate like Fuji Electric, the impact was immediate and compounding. Capital spending dried up. Customers stretched out replacement cycles and delayed big projects. And a strengthening yen made exports harder to win.

At the same time, a new constraint was starting to move from the margins to the center: pressure to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Energy efficiency and cleaner power weren’t just “nice to have” anymore—they were becoming a strategic requirement.

The New Vision 21 Plan

Fuji Electric’s first big response was the New Vision 21 Plan in 1991, a reorganization into eight business segments meant to bring focus and discipline to a sprawling portfolio. But the lost decade kept grinding on, and the structure didn’t fully solve the underlying problem.

So the company tried again. In 1999, Fuji Electric restructured into four main divisions. By 2000, it clawed its way back to profitability after three years of losses.

But the bigger question still hung in the air: how do you generate real growth when your home market feels stuck in slow motion?

The Holding Company Transformation

In 2003, management made a more drastic move—changing the company into a holding structure. The parent was renamed Fuji Electric Holdings Co., Ltd., with core operating companies including Fuji Electric Systems Co., Ltd. and Fuji Electric FA Components & Systems Co., Ltd.

The idea was straightforward: stop trying to manage everything as one monolith. Separate the slower-growth traditional businesses from the higher-growth electronics and semiconductor businesses, and let each get the right strategy, the right investment pace, and the right accountability. In theory, a holding company would mean clearer capital allocation, sharper focus, and faster decisions.

In practice, it was a sign of something deeper: Fuji Electric was looking for a structure that could help it reinvent itself—again—under the harshest economic conditions Japan had seen in generations.

VIII. Key Inflection Point #1: The 2011 Corporate Reunification

The Decision to Reverse Course

What happened next says something quietly profound about Japanese industrial management: sometimes the most strategic move is admitting the last one didn’t deliver.

In 2011, Fuji Electric reversed the holding company structure it had created in 2003. Fuji Electric Holdings Co., Ltd. merged with Fuji Electric Systems Co., Ltd., and the company returned to a single operating identity under the name it uses today: Fuji Electric Co., Ltd. The structure that once promised sharper focus and cleaner accountability lasted less than a decade.

The reason for the reversal gets to the heart of what makes Fuji Electric different. The company’s edge isn’t just that it makes power semiconductors, or that it builds power electronics systems. It’s that it does both—and that the two get better together.

When semiconductors and systems are developed in one integrated organization, Fuji Electric can connect chip-level design to real-world operating conditions. It can simulate how high voltage and large waveform variation at switching ripple through the semiconductor and into surrounding circuits. Split those teams apart, and you don’t just add organizational friction—you dull the feedback loop that turns hard-won field knowledge into better devices, and better devices into better systems.

In other words, the holding company structure didn’t just reorganize Fuji Electric. It accidentally pulled apart one of the company’s most important compounding advantages.

The Post-Fukushima Energy Landscape

The timing turned out to matter, too. In 2011, the Tōhoku earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster didn’t just shock Japan—they rewrote the country’s energy playbook. Nuclear power, which had supplied roughly 30% of Japan’s electricity, suddenly became politically untenable. The immediate need wasn’t theoretical. Japan needed alternatives, and it needed efficiency.

In that environment, Fuji Electric’s geothermal capability became more than a niche strength. Japan sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire, with significant geothermal resources that had long been underutilized. After Fukushima, geothermal development began to accelerate—and Fuji Electric was one of the few players with the experience and equipment to meet that demand.

Strategic Partnerships

Reunification also made it easier to pursue partnerships with a single, coherent strategy instead of a patchwork of subsidiary agendas. The company already had a signal example: in 2008, Fuji Electric FA Components & Systems Co., Ltd. had merged with Schneider Electric Japan, Ltd., underscoring Fuji Electric’s global ambitions in industrial automation. Under a unified corporate structure, moves like that could be integrated more cleanly into the broader strategy—and, crucially, tied back to the company’s core strengths in power electronics.

IX. Key Inflection Point #2: The Geothermal Global Dominance Strategy

Building an Unassailable Position

Fuji Electric’s dominance in geothermal power didn’t happen by accident. It was built the hard way: decades of investment, incremental engineering gains, and patient relationship-building with customers operating in some of the most remote, unforgiving places on earth.

One project became the calling card. In May 2010, Fuji Electric completed the world’s largest single-unit geothermal power station at the time: Nga Awa Purua in New Zealand. Its 140 MW output was enough to supply electricity for roughly 450,000 households.

Nga Awa Purua also showcased just how far Fuji’s turbine technology had come. The plant featured the largest single-shaft geothermal turbine in the world, built around an advanced design with a triple-pressure inlet and double-flow high- and low-pressure sections. Even the physical scale underscored the point: last-stage blades stretched to about 31 inches.

This wasn’t just a record for the brochure. It was proof—delivered in steel and megawatts—that Fuji Electric could take on the toughest geothermal specs and win. And that credibility mattered in every competitive bid that followed.

The Indonesia Strategy

If New Zealand was the statement project, Indonesia became the sustained campaign.

Indonesia holds the world’s second-largest geothermal resources, and Fuji Electric turned that potential into a position of real influence. Over time, it delivered 19 steam turbines to geothermal power plants in the country—about a 50% share of the market.

A representative example is the Muara Laboh Geothermal Power Plant in West Sumatra. It’s a flash-type facility with 85 MW of generation capacity, located deep in mountainous terrain—around five hours by vehicle from the nearest airport. It began commercial operation in December 2019, supplying power for about 420,000 households across western Sumatra.

Projects like Muara Laboh highlight what geothermal actually demands from suppliers. These aren’t neat, accessible construction sites. They’re often volcanic regions with brutal logistics, aggressive groundwater chemistry, and extreme operating conditions. Getting equipment there is hard. Keeping it running for decades is harder.

The Unique Competitive Advantage

Geothermal power generation largely comes in two technology families: flash systems and binary cycle systems. Fuji Electric’s differentiator is simple, and rare: it has both a product lineup and a track record in both.

That matters because geothermal resources aren’t uniform. Higher-temperature fields tend to favor flash systems. Lower-temperature resources often need binary cycle systems. If you can only do one, your market is limited. If you can do both, you can credibly bid on almost any geothermal project—and tailor the solution to the site rather than forcing the site to fit your equipment.

Durability and Long-Term Relationships

Geothermal is a long game, and Fuji Electric has played it like one.

Many geothermal plants using Fuji Electric equipment have operated for 30 years or more after initial startup—an outcome the company attributes to steam turbine design and manufacturing technologies built up over decades of experience.

That kind of longevity compounds into advantage. It proves reliability to customers who are committing capital for multi-decade assets. It creates long-running service and maintenance relationships. And it builds trust that often turns into the most valuable deal of all: the next order, when a utility expands capacity or upgrades a site.

X. Key Inflection Point #3: The Power Semiconductor Bet

The EV Revolution and Power Semiconductor Opportunity

If geothermal is Fuji Electric’s “quiet dominance” story, power semiconductors are its next big swing.

The shift to electric vehicles is the largest transformation the auto industry has seen in a century, and it runs on a deceptively unsexy set of components: power semiconductors. Every EV needs power electronics to translate battery power into motor motion, and small efficiency gains here show up as real-world range, heat, and reliability.

Fuji Electric entered this moment with real credibility. In IGBT power modules for industrial use, it holds a top-three position globally. The market is concentrated: the five largest manufacturers—Infineon, Mitsubishi Electric (Vincotech), Fuji Electric, Semikron Danfoss, and StarPower Semiconductor—collectively account for about 70% of supply, with Infineon alone at roughly 30%.

But IGBTs are only the foundation. The bigger bet is silicon carbide.

The Massive Investment Commitment

According to Nikkei, Fuji Electric plans to invest JPY200 billion (about US$1.4 billion) into its semiconductor business over the three fiscal years from 2024 through 2026.

Put differently: after years of a much steadier investment pace—around JPY40 billion per year through fiscal 2023—Fuji Electric is dramatically stepping on the gas. This isn’t incremental capacity. It’s a declaration that SiC is central to the next era of the company.

The DENSO Partnership and Government Support

Fuji Electric isn’t trying to make this leap alone—and Japan’s government doesn’t want it to.

Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) announced subsidies of up to JPY70.5 billion (about US$470 million) for a SiC power semiconductor production collaboration between DENSO and Fuji Electric. The joint project is valued at JPY211.6 billion, with the government covering roughly one-third of the total investment.

The division of labor is clear. DENSO will produce SiC substrates and epitaxial wafers, while Fuji Electric will manufacture SiC epitaxial wafers and the power semiconductors themselves. DENSO is expanding facilities in Kōta, Aichi Prefecture, and Inabe, Mie Prefecture. Fuji Electric is upgrading its Matsumoto factory in Nagano Prefecture. The project targets annual wafer production capacity of 310,000 by May 2027.

Strategically, it’s a clean fit. DENSO brings deep relationships across the automotive supply chain. Fuji Electric brings decades of device and power-electronics manufacturing know-how. Together, they’re trying to secure a domestic, scalable SiC pipeline—materials through devices—at the exact moment the global market is tightening.

The Robert Bosch Collaboration

Then, just days ago, Fuji Electric announced another partnership—this time with Robert Bosch GmbH, one of the world’s most important automotive suppliers—to collaborate on SiC power semiconductor modules for EVs with package compatibility.

The key idea is mechanical exchangeability. Fuji Electric and Bosch aligned the main dimensions of their respective SiC power modules so automakers can integrate either module into an inverter housing with significantly reduced mechanical effort. That preserves the flexibility of multi-sourcing—critical in a supply-constrained world—without forcing customers into expensive redesigns every time they change suppliers.

This is standard-setting disguised as engineering. If your module fits the housing, and the housing becomes the default, you’re not just selling components—you’re shaping the rules of the market.

The SiC Expansion Plans

All of this ladders up to a single goal: shift Fuji Electric’s semiconductor mix toward SiC as demand rises across EVs and solar energy applications.

Fuji Electric aims to grow SiC modules from about 1% of semiconductor sales today to 20% by March 2027. If it pulls that off, it doesn’t just add a product line—it changes what the semiconductor segment is, and what it can become in the next decade.

XI. The Modern Fuji Electric: Business Portfolio & Strategic Direction

The Four-Pillar Structure

After a century of reinvention—heavy electrical equipment, early semiconductors, geothermal dominance, and now SiC—Fuji Electric today looks surprisingly coherent. The company runs four core segments.

Energy is the “big iron” side: geothermal, hydroelectric, and thermal power generation, plus fuel cells, substation equipment, power storage systems, and energy management systems. Industry is the factory-floor nervous system—things like inverters, measuring instruments, sensors, and drive and measurement control systems. Semiconductors is the device layer underneath it all, supplying power semiconductors for industrial and automotive applications. And then there’s Food and Beverage Distribution, which covers vending machines and retail systems—the consumer-facing expression of the company’s power electronics and reliability obsession.

Recent Performance

That portfolio is well-matched to the world Fuji Electric finds itself in: rising energy demand, a growing mandate for energy efficiency, and accelerating electrification across heavy industry. Fuji Electric has leaned into expanding its plant and system businesses, while also pushing productivity improvements at production sites using digital technology.

The results have followed the strategy. Recent performance has been supported by strength in the Energy and Industry segments, with capital investment holding up in power, manufacturing, and data centers—driven by green transformation spending and rising electricity demand tied to generative AI and broader digitalization.

The 2023 Organizational Realignment

Fuji Electric also adjusted its internal structure to better match the moment. To strengthen its positioning in the energy transition, it integrated the Power Electronics Energy Business Group with the power generation business—thermal, geothermal, hydro, and alternative energy—to create a new Energy Business Group.

The logic here is straightforward: customers don’t buy the energy transition in parts. A renewable project might require turbines, power electronics, storage, and grid connection equipment. By aligning these capabilities under one umbrella, Fuji Electric is setting itself up to sell an integrated solution—not a catalog of components.

Management Targets

In the FY2026 Medium-Term Management Plan announced in May 2024, the company adopted profit-focused management as its basic policy. It set key targets for fiscal 2026, including an operating profit ratio of 11% or more, a ratio of profit attributable to owners of parent to net sales of 7% or more, ROE of 12% or more, and ROIC of 10% or more.

Fuji Electric also acknowledged a reality that changes the math for every capital-intensive manufacturer: the cost of capital is rising. While it estimated its WACC at around 8% when it formulated the plan, it recognized that this has increased by about 1% as Japan shifted into a world with interest rates. The response, it said, is to run each segment with a sharper focus on capital efficiency.

That ROIC emphasis is a notable signal. Japanese industrial companies have long been criticized for chasing scale and market share at the expense of returns. Fuji Electric’s explicit commitment to clearing its cost of capital—and updating the hurdle rate as financing conditions change—reads like a company trying to pair its engineering ambition with tighter, more modern capital discipline.

XII. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Strategic Positioning

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

On both of Fuji Electric’s most important playing fields—geothermal turbines and power semiconductors—the “startup in a garage” story just doesn’t apply.

These are businesses where competence is earned the slow way: decades of field experience, hard-won manufacturing know-how, and a track record that customers can trust with assets expected to run for generations. Fuji Electric can point to geothermal plants using its equipment that have operated for 30 years or more, which is the kind of proof no newcomer can manufacture quickly.

Then there’s the cost to even get in the game. Semiconductor manufacturing is brutally capital-intensive, and the DENSO–Fuji Electric silicon carbide effort alone represents well over a billion dollars of investment. And even if you can spend the money, customers don’t switch easily. In mission-critical energy infrastructure and automotive-grade semiconductors, qualification cycles can take years, and reliability is non-negotiable.

In geothermal specifically, Fuji Electric’s ability to deliver both flash and binary cycle systems is another barrier. A new entrant would need years of engineering development and project experience to match that breadth—and without it, they simply can’t bid credibly on a large portion of projects.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

If there’s a pressure point in the semiconductor story, it’s upstream: materials.

Silicon carbide wafers are a constrained input across the industry, and Fuji Electric—like everyone else—competes for limited supply, often against larger players with massive purchasing power.

But Fuji Electric is not entirely at the mercy of the market. Its vertical integration helps, and the DENSO partnership is explicitly designed to improve supply chain security by building domestic capacity for substrates and epitaxial wafers. That doesn’t make supplier power disappear, but it does reduce the odds that growth plans get throttled by shortages.

Fuji Electric also benefits from deep engineering capability in manufacturing, which gives it more flexibility to qualify and work with multiple equipment and materials suppliers rather than getting locked into a single point of failure.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Fuji Electric sells to buyers who are both sophisticated and large: utilities, industrial OEMs, and automotive supply chains. These customers have procurement leverage, and they push hard on price.

Still, this isn’t a category where “cheapest wins” is a reliable strategy. When a utility is committing to a geothermal plant expected to operate for 30-plus years, the purchase decision isn’t just about initial cost—it’s about uptime, serviceability, and confidence that the supplier will be there for the full lifecycle. In those moments, technical credibility and field performance matter as much as the quote.

And once the equipment is installed, switching gets even harder. Long-term service relationships become a form of lock-in: maintenance, upgrades, and eventual replacement tend to favor the original supplier that knows the installed base best.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE TO HIGH

In semiconductors, substitutes are real—just not uniform.

Gallium nitride is advancing quickly and competes in certain applications and voltage ranges. But for high-power automotive use cases, silicon carbide remains the leading choice today, especially where efficiency and thermal performance translate directly into vehicle range and reliability.

On the energy side, geothermal competes for renewable investment against solar and wind, and solar in particular has become dramatically cheaper over the past decade. That has captured a huge share of global renewable growth.

But geothermal has a defensive advantage that’s hard to replicate: baseload reliability. It delivers steady output regardless of weather or time of day. As grids add more intermittent renewables, the value of always-on generation rises—meaning geothermal’s role can become more important, not less.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

In power semiconductors, rivalry is intense and global. The IGBT ecosystem includes many well-capitalized competitors, with Infineon as the clear leader at roughly 30% market share, alongside major Japanese and international players such as Mitsubishi Electric, Toshiba, and others across Europe, the U.S., and Asia. This is a market where technology cycles are fast, customers demand continuous improvement, and scale matters.

Geothermal is a different kind of competitive landscape—smaller, more specialized, and shaped by long project timelines. Fuji Electric’s leadership position, including a large share of orders since 2000, signals real dominance, but it’s not alone. Companies such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Toshiba, and Ormat Technologies remain meaningful competitors, and bids are often decided on a mix of engineering fit, risk tolerance, and long-term service capability.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Fuji Electric benefits from manufacturing scale, though it doesn’t match the sheer semiconductor scale of the largest global leaders. Its more distinctive scale advantage comes from its integrated model: developing power semiconductors alongside the power electronics systems that use them, which creates internal learning and reuse that pure-play competitors can’t fully replicate.

Network Effects: Limited in the traditional sense. That said, the Bosch partnership around package-compatible SiC modules is a potential wedge: if compatibility becomes a de facto expectation, it can create network-like momentum around a shared standard.

Counter-Positioning: In geothermal, Fuji Electric’s ability to offer both flash and binary cycle systems gives it a bidding flexibility that one-technology competitors lack. For rivals, matching that breadth isn’t a simple product launch—it requires years of engineering depth and reference projects across both approaches.

Switching Costs: High. In geothermal, plants are long-lived assets with decades-long service relationships. In automotive semiconductors, qualification cycles are lengthy and integration is often customer-specific, making supplier changes slow and expensive.

Branding: Limited. Fuji Electric isn’t a consumer-facing brand, and its customers tend to buy on performance, reliability, and track record rather than marketing-driven perception.

Cornered Resource: Historically, foundational capabilities came from the Furukawa Group network and the early Siemens technology partnership. More recently, the government-supported DENSO collaboration effectively improves access to capital and upstream materials capacity for SiC—an advantage in a supply-constrained moment.

Process Power: One of Fuji Electric’s most durable advantages. By integrating semiconductor development with power electronics system design, it builds feedback loops between device behavior and real operating conditions—process knowledge that’s hard for siloed organizations to match.

XIII. Investment Considerations: Key Risks and KPIs

Bull Case

Fuji Electric sits in a rare “right place, right time” intersection of long-cycle, structural trends.

Electric vehicles are pulling more and more value into power semiconductors. Grid decarbonization is reopening the case for geothermal as dependable, always-on renewable generation. And industrial automation keeps expanding the demand for inverters, sensors, and power electronics—the systems layer that turns electricity into controlled, productive work.

The other part of the bull case is simply endurance. A 100-year operating history doesn’t guarantee anything, but it does prove Fuji Electric can survive discontinuities—and, at a few key moments, use them to get stronger. Management has been willing to make unusually consequential calls: letting the telecom business go as Fujitsu, unwinding the holding-company structure when it got in the way, and now committing to a dramatically higher level of semiconductor investment to chase silicon carbide.

Geothermal leadership adds an element many semiconductor stories don’t have: a foundation business that can generate stable revenue plus long-running service relationships. If the SiC expansion works, it doesn’t just add growth—it potentially changes the company’s profile from “durable industrial” to “durable industrial with a high-growth semiconductor engine.”

Finally, the SiC push isn’t happening in a vacuum. METI subsidies lower the financial burden and de-risk part of the buildout, while partnerships with DENSO and Bosch bring supply-chain leverage, customer proximity, and collaboration on the product roadmap.

Bear Case

The most obvious risk is competitive gravity. Infineon’s lead in power semiconductors is real, and hard to dislodge—more scale, more capital, and deeper automotive entrenchment. Fuji Electric doesn’t need to “beat Infineon” to win, but it does need to carve out enough share and pricing power in SiC to justify the investment ramp.

Demand timing is the next pressure point. Machine tool-related demand has shown only a modest recovery, and demand tied to electrified vehicles has continued to plateau. If EV adoption slows, or if Chinese competitors take share faster than expected, Fuji Electric could end up with world-class capacity—and underwhelming returns.

Geothermal is also not a hypergrowth market. Solar and wind have captured most of the last decade’s renewable investment, and while geothermal is growing, the total addressable market remains smaller. Fuji Electric can dominate a niche and still find that the niche has a speed limit.

Then there are the “Japan-based global manufacturer” risks. Currency swings in the yen can whipsaw competitiveness and reported results. And while the vending machine and food distribution business can be a steady earner, it faces a long-term demographic drag in Japan as the population declines and consumer behavior shifts.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

Semiconductor Segment Operating Margin: Fuji Electric is targeting operating margins of 10% or more across all segments by fiscal 2026. Whether the semiconductor segment moves toward that level will be a practical read on whether SiC scale is translating into real profitability, not just volume.

SiC Revenue as Percentage of Semiconductor Sales: The company’s stated goal is to reach 20% by March 2027. Tracking how quickly SiC becomes meaningful inside the segment is one of the cleanest indicators of whether the strategy is taking hold.

Geothermal Order Backlog: Geothermal projects have long lead times, so backlog matters. A healthy, growing backlog is effectively future revenue already spoken for—and a sign that Fuji Electric is continuing to win in the market it helped define.

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

Japanese industrial policy is now an active part of the semiconductor landscape. That’s a tailwind in the form of subsidies, but it can also create constraints: programs can change, and subsidy terms can influence capital allocation decisions and timelines, including in the METI-backed DENSO collaboration.

On the financial statements, goodwill and intangibles from prior acquisitions are worth monitoring. Fuji Electric has operated with a relatively conservative balance sheet, including an equity ratio of around 50%, which provides resilience if a cycle turns.

Finally, cross-shareholding ties within the Furukawa Group still matter, even as Fuji Electric has been reducing them over time. The unwind can boost results in periods when sales of those holdings create gains—one example being cross-shareholding sales that contributed to a ratio of profit attributable to owners of parent to net sales of 8.2%—but it’s important to separate those one-time effects from underlying operating performance.

Conclusion: A Century-Old Company at Another Inflection Point

Fuji Electric’s story is, at its core, a story about reinvention. It began as a 1923 joint venture that fused Japanese capital with German engineering. It made the rare, world-class strategic call to spin out its telecom business as Fujitsu. It survived bombing, occupation, and reconstruction. It used the oil crisis to pivot hard into efficiency and power electronics. And it patiently turned an “odd” energy niche—geothermal—into global leadership.

Now it’s placing its next big bet: silicon carbide power semiconductors.

This moment may be the most consequential since the company’s founding, because the transitions are all happening at once. Automotive powertrains are moving to EVs. Electricity generation is shifting toward renewables. And industry is being forced—by cost, policy, and physics—toward deeper electrification and higher efficiency. Fuji Electric sits in the narrow overlap of all three.

Execution is the whole game from here, especially in semiconductors, where competitors are larger, faster, and fighting for the same constrained supply chains. But if you’re looking for exposure to the infrastructure layer of the clean energy transition, Fuji Electric is unusually well-positioned: a century-long record of adapting to structural change, real leadership in a critical niche market, and a management team willing to make big moves—then reorganize when those moves get in the way.

Ichibei Furukawa, the copper king who set this industrial web in motion, couldn’t have imagined a world of EV inverters and SiC wafers, or geothermal turbines supplying baseload renewable power. But he likely would have recognized the traits that carried the company here: a willingness to adopt new technologies, the patience to compound hard capabilities over decades, and the ambition to shape industries rather than simply sell into them.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music