MinebeaMitsumi: The Unsung Giant of Precision Components

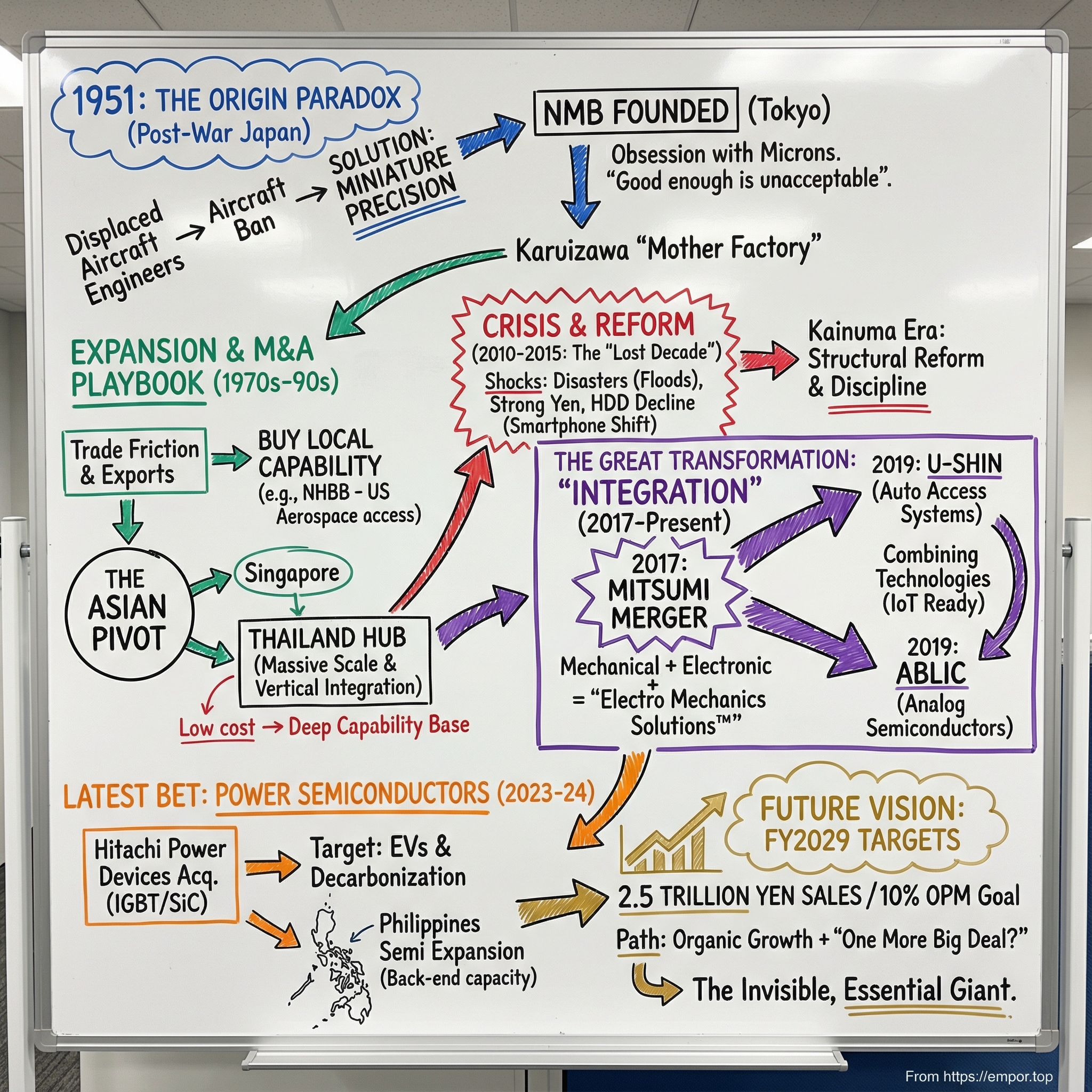

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Here’s the paradox: you’ve probably never heard the name MinebeaMitsumi, and yet you almost certainly interacted with their products today. The tiny motors that make your phone buzz. The bearings buried inside the small electric motors all over a modern car. If you’ve ever flown, there’s a good chance their aerospace-grade bearings were quietly doing their job in the mechanisms that help control an aircraft.

MinebeaMitsumi is the kind of company the modern world runs on but doesn’t see. It holds the world’s largest shares in six product areas, including about 65% of the global market for miniature ball bearings and about 65% in pivot assemblies. On paper, it’s a Japanese multinational manufacturer of mechanical components and electronic devices. In practice, it’s a behind-the-scenes enabler for many of the most demanding industries on Earth.

Financially, the business has been on a serious run. In the fiscal year ending March 2025, net sales reached 1,522,703 million yen (about $10.5 billion), up 8.6% year over year, while operating income rose 28.5% to 94,482 million yen. That momentum sits on top of a bigger arc: over the past fifteen years, MinebeaMitsumi has grown from net sales of 256 billion yen in fiscal 2009 to a company now aiming for 2.5 trillion yen by 2029.

What they make can sound almost absurd in its range. MinebeaMitsumi manufactures more than 8,500 types of miniature and small-sized bearings and claims a global share of more than 60% in that category. At one end of the spectrum is the world’s smallest mass-produced ball bearing, with an outer diameter of just 1.5 millimeters. At the other end are power semiconductors headed for electric vehicles and industrial electrification.

So this is the question that drives the story: how did a post-war Japanese bearing company—founded by displaced aircraft engineers in a modest Tokyo workshop—turn into one of the world’s most essential yet unknown suppliers?

The answer comes down to three threads that keep weaving together over decades: an obsession with precision measured in microns; a disciplined, repeatable M&A playbook that compounds capabilities and scale; and a strategic shift from “we make parts” to what the company calls INTEGRATION—combining mechanical and electronic technologies into solutions competitors can’t easily replicate.

That journey starts in 1951 with a group of engineers whose aviation ambitions were forced to find a new outlet. It runs through a decades-long expansion across Asia and the West. And it leads to today’s push into semiconductors—an ambitious bet that places MinebeaMitsumi squarely in the supply chain of the electric future.

II. Post-War Origins: From Manchurian Dreams to Miniature Mastery (1951–1970s)

In the summer of 1951, in a Tokyo still deep in recovery, a small group of engineers set up shop in Itabashi Ward with a plan that sounded almost backwards for the time. In July 1951, they founded Japan’s first company dedicated to miniature ball bearings.

They hadn’t set out to build bearings. They were aviation engineers—men who had worked at the former Manchuria Airplane Manufacturing Company and had come back to Japan after the war. Their ambitions were still pointed at aircraft. But there was a problem: under the American occupation, Japan’s aircraft industry was effectively off-limits. So they faced a stark choice. Either shelve years of aerospace know-how, or find a new arena where that same level of precision could win.

They found it in miniature bearings.

The company launched as Nippon Miniature Bearing Co., Ltd.—NMB—and that label would go on to become one of the most widely stamped marks in the component world. MinebeaMitsumi began by manufacturing miniature ball bearings in 1951 under the NMB name, and over time it grew into the world’s largest manufacturer in that segment.

Focusing on “miniature” wasn’t a cute niche; it was a deliberate strategic wedge. Big bearings already belonged to giants like Sweden’s SKF and Japan’s industrial incumbents. But miniature bearings—typically with outer diameters of 22 millimeters or less—were a different game. Here, performance lives and dies on surface finish and microscopic geometry. A ball that looks perfectly smooth to the naked eye can reveal roughness under magnification, and that roughness becomes friction, heat, wear, noise—failure. To push friction down as far as possible, MinebeaMitsumi fitted its bearings only with ultra high-precision balls polished to nano-level Ra (surface roughness).

This is where the aerospace background mattered. In aircraft components, “good enough” is just another way of saying “unacceptable.” The founders carried that mindset straight into civilian manufacturing: tighter tolerances, stricter process control, and an obsession with repeatability.

As demand grew, they scaled. In 1963, the Company built a new large-scale factory in Karuizawa, Nagano—later the Karuizawa Plant—and in 1965 it shifted all production there. Karuizawa wasn’t just a bigger facility; it became an early version of what MinebeaMitsumi would later formalize as its mother factory approach: Japanese plants as the center for development, manufacturing know-how, and technical training that could be carried elsewhere.

The customers came from the industries rebuilding and modernizing Japan: camera makers needing smooth, reliable motion in shutters and focusing mechanisms; watchmakers chasing smaller and more precise movements; textile machinery manufacturers running equipment at high speed where reliability wasn’t optional. Each customer pulled the same lever—higher precision, higher consistency, higher trust.

By the latter half of the 1960s, that precision was traveling. Around 70% of the ball bearings produced at the Karuizawa Plant were exported to the United States. It was proof that this tiny Tokyo-born company could compete globally on quality. It also set up the next chapter: when exports surge, attention follows—and trade friction, and the strategic need to produce closer to customers.

But the foundation was already in place. Aerospace-grade thinking, applied to the smallest possible component, for the most demanding use cases. That combination—miniaturization plus uncompromising precision—became the company’s core identity, and it would carry through everything MinebeaMitsumi built over the decades that followed.

III. The Original M&A Company: Expansion Through Acquisition (1970s–1980s)

By the early 1970s, Minebea had run straight into a problem that hits every great exporter sooner or later: success attracts scrutiny. Exports to the United States were growing fast, and with that came trade friction. The U.S. government, aiming to protect domestic bearing manufacturers, introduced rules that restricted overseas firms from supplying defense-related products.

Minebea’s response in 1971 was unusually bold for a Japanese manufacturer of the era. Instead of arguing from afar—or hoping the policy winds would change—it bought its way onto American soil, acquiring U.S. REED Instrument Corp., a local subsidiary of Sweden’s SKF. That business became Minebea’s Chatsworth plant in California.

This wasn’t just a factory purchase. It was a mindset shift. Japanese companies in the early ’70s rarely made overseas acquisitions; cultural and financial barriers made deals like this feel almost unthinkable. Minebea did it anyway, because leadership understood a simple truth: if the U.S. market was going to be critical, production had to be local.

Chatsworth became the first proof point of a playbook Minebea would run again and again. Don’t start from zero in a new market. Acquire an operation that already has capabilities, customer relationships, and, most importantly, people who understand the local realities. Speed and know-how beat slow, uncertain greenfield buildouts.

At the same time, Minebea was bumping into a different constraint back home: labor and production capacity. So it began spreading manufacturing across Asia. In 1980, Nippon Miniature Bearings opened manufacturing subsidiaries in Taiwan and Thailand, and it acquired a factory in Singapore to begin manufacturing small-sized ball bearings there as well.

Singapore, in particular, turned out to be more than a cost play. It offered stability, access to fast-growing Asian markets, and a workforce that could support high-precision manufacturing. Over time, it became part of a broader Southeast Asian network that would grow into the backbone of Minebea’s global production system.

Then came consolidation at home. In 1981, Tokyo Screw Co., Ltd., Shinko Communication Industry Co., Ltd., Shin Chuo Kogyo Co., Ltd., and Osaka Wheel Co., Ltd. were merged, and the present name of Minebea Co., Ltd. was established. The deal expanded Minebea beyond bearings, pulling in complementary capabilities in fasteners and precision components and widening what the company could credibly sell.

But the most strategically important move of the decade arrived in 1985: the acquisition of New Hampshire Ball Bearings, or NHBB.

NHBB had been founded in 1946 in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and built its reputation the hard way—by making fully ground miniature ball bearings for defense and aerospace, then expanding into the emerging computer industry. Over time, it developed custom, high-precision solutions for demanding applications across aero engines, airframe control actuation assemblies, landing gear, helicopter rotor systems, space and satellite programs, UAVs, missile systems, medical and dental devices, and more.

For Minebea, NHBB wasn’t just another overseas asset. It was a key that unlocked sectors where Japanese companies faced steep barriers. Aerospace and defense are markets of qualification, trust, and long relationships. NHBB brought specialized expertise and the customer ties required to compete—advantages Minebea could not have built from scratch in any reasonable timeframe.

Today, NHBB operates three domestic manufacturing divisions, employs over 1,400 workers, and serves customers around the world. Its growth has continued to be driven by the same thing that made it valuable in the first place: relentless responsiveness to customer needs.

Step back and the logic of this whole era snaps into focus. Minebea acquired to gain capabilities, geographic presence, and customer relationships that would have taken years—often decades—to build organically. And unlike many serial acquirers that accumulate companies without truly knitting them together, Minebea began developing something rare: a repeatable integration muscle, one that preserved what it bought while steadily applying its own operational discipline and precision manufacturing culture.

By the end of the 1980s, Minebea was no longer just a Japanese miniature bearing specialist. It had become a multinational manufacturer with real operating depth across Japan, the United States, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand—and the scaffolding was up for the next, even bigger expansion.

IV. The Thailand Pivot & Asian Manufacturing Empire (1980s–1990s)

By the 1980s, Minebea was running into a new kind of ceiling. Singapore had been a smart early move for overseas production, but as the local economy grew, so did costs and competition for workers. Management concluded there was a limit to how far that footprint could scale. So the company did what it had learned to do best: pick the next platform, build early, and commit. It constructed a new plant in Thailand and started production.

That decision became one of the most consequential in the company’s history. What began as a practical response to Singapore’s rising costs turned into the anchor of a manufacturing network that still defines MinebeaMitsumi’s advantage.

Minebea’s Thailand story formally began with the establishment of NMB-Minebea Thai Ltd. in 1982. It started with what the company knew cold—miniature bearings—and then steadily broadened into mechanical and electronic components. Thailand, at the time, offered what Singapore no longer could at the same scale: abundant labor, lower costs, and a government eager to attract foreign investment. But Minebea didn’t treat Thailand as a cheap assembly outpost. It invested as if it were building a long-term capability base.

That investment showed up in how the company organized its engineering. In the “mother factory” system, Japan remained the nerve center: the Karuizawa Plant supported overseas factories with bearings and related products, while the Hamamatsu Factory played that role for electronic devices. But Thailand didn’t stay dependent. The Thai Factory built the ability to respond locally and established an R&D center right on the factory premises—an important signal that this was becoming a full-fledged production and engineering hub, not just a place to run machines.

Over time, the Thai operations scaled into a major pillar of the group. MinebeaMitsumi’s Thai Operations came to account for more than 20% of global production. The company established the Ayutthaya plant in 1980 and expanded rapidly from there. Today, it has a total of 10 bases in Thailand and approximately 30,000 employees.

The workforce scale is striking, and it comes with another distinction: MinebeaMitsumi is the largest Japanese company in Thailand by number of employees. That’s not simply a cost story. It reflects decades of building Thai manufacturing capability to meet the same standards that made the company competitive in the first place.

This is also the period where Minebea’s footprint in Asia becomes inseparable from its market dominance. The company holds the world’s largest shares in six product areas, including ball bearings (about 65%) and pivot assemblies (about 65%). International Asian business accounts for roughly 80% of production and about 50% of sales—evidence that the center of gravity in the company’s operations had shifted.

As the network grew, Minebea doubled down on another defining choice: vertical integration. Rather than outsource critical inputs, it brought more of the supply chain inside its own walls. In motors, for example, most parts—from the shaft and hub to the stator and magnet—are produced in-house. The payoff is control: quality, supply reliability, manufacturing cost, and speed of delivery.

Decades later, the result is a global manufacturing system built around Asia, with Thailand as its cornerstone. As of March 31, 2024, MinebeaMitsumi operated 129 manufacturing plants in 23 countries worldwide, and as of March 2025 the group employed 83,256 people.

The company owns and operates manufacturing plants across Japan, Thailand, China, Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Cambodia in Asia, as well as in North America and Europe.

And that’s the real legacy of the Thailand pivot. It created durable advantages that still compound: scale in ultra-precision manufacturing, a workforce with deep accumulated expertise, vertically integrated supply chains that protect quality and responsiveness, and geographic diversification that makes the whole system more resilient when disruptions hit.

V. The Lost Decade Crisis & Business Structure Reforms (2010–2015)

After spending the ’80s and ’90s building a manufacturing empire across Asia, Minebea hit a stretch in the early 2010s that exposed just how fragile even great operations can be. The first half of the decade stacked headwinds on top of headwinds: major natural disasters in Japan and abroad, soaring rare earth prices, a record-strong yen, and a global economy losing steam.

Then the shocks got painfully specific. The Great East Japan Earthquake rippled through supply chains across the country. In 2011, catastrophic floods in Thailand tore through the country’s industrial belt—including facilities that were central to Minebea’s production network. At the same time, the yen’s surge against the dollar made exports less competitive right when customers were looking for every possible cost reduction.

But the most strategic threat wasn’t a flood or a currency move. It was technology.

Minebea had built meaningful scale in hard disk drive spindle motors. And then the smartphone era arrived, accelerating the world’s shift from spinning disks to solid-state storage. For the HDD ecosystem, this wasn’t a cyclical dip. It was a structural decline. In practical terms: every device that moved to solid-state meant fewer hard drives, which meant fewer motors—putting a core growth engine of Minebea’s business under pressure.

The company’s response centered on business structure reforms, guided by two stated goals: “maximizing incomes per share and raising corporate value” and “solidifying the foundations for the 100th anniversary of Minebea.” In concrete terms, that meant moves like dissolving its motor joint venture to make the business a wholly owned subsidiary, and tightening both its vertically integrated production system and its cross-division collaboration—so product groups weren’t operating as islands.

This wasn’t painless. There was real restructuring. But it also wasn’t a retreat from motors. Management’s insight was that motors weren’t going away—only the demand was migrating. HDD motors might be shrinking, but automotive motors, fan motors for electronics cooling, and a range of industrial applications were growing. The task was to pivot capability toward the markets that were expanding.

A key step was taking full control of the motor operation. Since 2004, Minebea had run Minebea-Matsushita Motor Corporation as a joint venture. By bringing it fully in-house, Minebea gained speed—faster decisions, clearer accountability, and tighter alignment with the rest of the company’s strategy.

The reforms worked. In FY03/2015, Minebea surpassed 500 billion yen in net sales for the first time since its founding—an important marker that the company had not only stabilized, but was back on an upward trajectory.

This period also cemented the leadership era that would define Minebea’s next phase. Yoshihisa Kainuma had become president in 2009, and through these years he pushed to raise the company’s technical prowess and management strength by putting new ideas into practice. His path was unusual for a manufacturing CEO: he joined the company in December 1988, held a law degree from Keio University, and earned a master’s in law from Harvard. That legal training often showed up in the way Minebea approached complexity—disciplined choices, clear structures, and a comfort with the mechanics of deals and integration.

Fifteen years after Kainuma’s appointment as CEO, the contrast was stark. In the fiscal year ended March 2024, the company posted record-high consolidated results for the 11th consecutive year, with net sales of 1,402.1 billion yen and operating income of 73.5 billion yen. Back in the fiscal year ended March 2009, those numbers were 256.2 billion yen in sales and 13.4 billion yen in operating income. In other words: a business that had been forced to reinvent itself during the early 2010s emerged with results more than five times larger over the longer arc.

And that’s what makes this “lost decade” so important to the story. It didn’t just test Minebea’s resilience—it changed how the company thought. The danger of relying too heavily on one end market. The value of vertical integration when supply chains break. The necessity of evolving the portfolio before the world forces you to.

Those lessons set the stage for what came next: a more aggressive, more deliberate transformation—powered by bigger deals, broader capabilities, and a push beyond components into integrated electro-mechanical solutions.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Mitsumi Electric Merger (2017)

By the time the 2010s reforms were working, Minebea had already lived through one identity shift. Back in October 1981, after a series of mergers, it had simplified its name to Minebea Co., Ltd. But the far bigger reinvention came decades later. On January 27, 2017, Minebea acquired Mitsumi for $500 million—and with that deal, it became MinebeaMitsumi.

This wasn’t a bolt-on acquisition. It was a statement that the company was no longer content to be “the bearing and motor people.” Mitsumi Electric Co., Ltd., founded in 1954, brought a different DNA: consumer-electronics components at global scale. After the merger, Mitsumi became a subsidiary of the combined company, and the portfolio suddenly widened in a way that changed what Minebea could be.

Mitsumi was best known as an OEM supplier of electronic components and peripherals—products like computer input devices, floppy and optical disc drives, and parts that ended up inside everything from laptops and servers to the Famicom Disk System. It had been a Tokyo Stock Exchange-listed company, a Nikkei 225 constituent, with subsidiaries spanning Asia, Europe, and North America. And for many consumers, the most visible reminder of Mitsumi’s reach was simple: video game console controllers.

For Minebea, though, the value wasn’t nostalgia. It was capability. Mitsumi brought connectors, sensors, optical devices, semiconductor devices, high-frequency components, power source components, and smartphone camera modules. Minebea, with its roots in machined components like ball bearings—and later rod end bearings and pivot assemblies for aircraft—had already expanded into motors, lighting devices, measuring components, and other electronic devices. Put together, the combined company wasn’t just bigger; it was broader in a way that opened new strategic lanes.

Management described the intent clearly: this business combination aimed to turn Minebea into a genuine solutions company by realizing synergies of integration, and to drive a further improvement in corporate value as an Electro Mechanics Solutions™ company.

That trademarked phrase mattered because it captured the logic of the deal. MinebeaMitsumi would combine Minebea’s ultra-precision machining with Mitsumi’s electronics to support the coming age of IoT—where the most valuable hardware isn’t just precise, it’s intelligent and connected.

The most telling detail is what almost happened next. When the integration with Mitsumi began, Mitsumi’s analog semiconductor business was initially on the table as a potential divestiture. Looking back, the company recalls holding two joint management meetings—both teams staying over at a hotel—where analog semiconductors were discussed as a candidate for sale. But Mitsumi’s team delivered what Minebea considered an excellent presentation, and leadership chose the opposite path: make a firm commitment to the semiconductor business, and even begin discussing future M&A candidates.

That choice would echo through everything that followed. A business that looked optional in 2017 became a foundation for where MinebeaMitsumi wanted to go.

Execution mattered too. The company emphasized enhancing cost competitiveness and cash-generation capacity by optimizing its manufacturing structure and production bases—classic Minebea discipline applied to a newly expanded set of technologies.

And out of the merger came the philosophy MinebeaMitsumi would keep repeating in all caps: INTEGRATION. Not “we now sell more parts,” but “we can combine them.” A motor paired with sensors and semiconductors becomes a smart actuator. Precision mechanical components fused with electronics and control technology become systems customers can’t easily source from one traditional supplier.

MinebeaMitsumi said it would continue introducing new value through Electro Mechanics Solutions™ in a world where everything is connected via IoT, combining technologies across ultra-precision mechanical components, motors, sensors, semiconductors, and wireless communication—and fusing machines and electronics with control technology.

In other words, after 2017 the company’s trajectory changed. The central question wasn’t only “How small can we make a bearing?” It became: what can we build when mechanical precision and electronic intelligence live under the same roof?

VII. Inflection Point #2: The 2019 Acquisition Spree—U-Shin & ABLIC

With Mitsumi integrated and the company newly confident in its “Electro Mechanics Solutions” identity, MinebeaMitsumi didn’t slow down. It sped up—using M&A to plug two of the biggest gaps in its portfolio: deeper automotive exposure and real semiconductor depth.

The first move was U-Shin.

Founded in 1926, U-Shin was an established name in automotive access products—key sets, door latches, door handles, and the systems that tie them together. On April 10, 2019, MinebeaMitsumi acquired 76.2% of U-Shin’s voting rights, making it a subsidiary. A few months later, as of August 7, 2019, it moved to 100% ownership.

On the surface, door handles and latches might not sound like the future. But in modern vehicles, “access” is where mechanical reliability meets electronics and software—keyless entry, anti-theft systems, and ever-more sophisticated authentication methods. U-Shin also brought an R&D footprint across the U.S., India, Germany, and France, giving MinebeaMitsumi both customer proximity and engineering capacity in the heart of the global auto industry.

MinebeaMitsumi laid out the plan for U-Shin plainly: turn around the European business, generate synergies, and use automotive devices as the center of gravity to expand into home security units. The core advantage, as the company described it, was all-in-one know-how—from development and design through production—for systems that span mechanical structures, electronic technology, and software. In other words: exactly the kind of “integration” MinebeaMitsumi wanted to be known for.

Then came the semiconductor leg of the one-two punch: ABLIC.

On December 17, 2019, MinebeaMitsumi’s Board approved the acquisition of shares in ABLIC Inc., making it a subsidiary. The company entered into a share agreement to acquire ABLIC from Development Bank of Japan Inc. and Seiko Instruments Inc. for ¥34.4 billion.

ABLIC’s roots went back to 1968, beginning with the development of CMOS ICs for quartz watches. Over decades—first as a semiconductor division under SII—it built a lineup defined by low power consumption, low-voltage operation, and ultra-small packaging. By the time MinebeaMitsumi acquired it, ABLIC had become a semiconductor manufacturer with a large catalog of differentiated products.

Strategically, ABLIC strengthened MinebeaMitsumi where it mattered most: analog semiconductors. Its specialties included lithium-ion battery protection ICs, Hall effect magnetic sensors, and EEPROMs. Just as important, ABLIC had been winning designs in growth markets like automotive devices, medical devices, and IoT and wearable products—exactly the domains MinebeaMitsumi was targeting after the Mitsumi merger. The company emphasized that the two portfolios complemented each other, and that the acquisition would create multiple synergies.

Even the deal mechanics signaled momentum. DC Advisory advised MinebeaMitsumi on the ABLIC acquisition after also advising on the initial U-Shin acquisition—a small detail, but a telling one: MinebeaMitsumi was now running repeatable, institutional M&A.

Underneath both deals was the framework that increasingly organized the entire company: the “Eight Spears.” The idea was simple and disciplined—identify the product areas where MinebeaMitsumi could bring its super-precision processing and mass production strengths, where the products wouldn’t be easily eliminated from the market, and then create new value by combining and integrating them. Analog semiconductors, positioned as one of those spears, mattered because they function as a gateway to IoT technologies—one of the areas the company was explicitly prioritizing—so MinebeaMitsumi intended to keep expanding its analog semiconductor business by broadening the portfolio and entering new application markets.

At the center of it all was Yoshihisa Kainuma, serving as Chairman, President, CEO & Chief Operating Officer of MinebeaMitsumi, and also Chairman of U-Shin and Chairman of ABLIC.

This wasn’t acquisition for acquisition’s sake. U-Shin gave MinebeaMitsumi a system-level foothold in automotive access and security. ABLIC gave it the analog semiconductor building blocks for battery-powered, sensor-rich, connected devices. Together, they pushed the company further along the path it had set in 2017: not just making parts, but integrating them into solutions that are hard to replicate—and even harder to replace.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The Semiconductor Bet—Hitachi Power Devices (2023–2024)

After ABLIC, MinebeaMitsumi’s semiconductor push had a clear next step: move from “the chips that sense and protect” into “the chips that move power.” The most ambitious move in that direction was the acquisition of Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device.

Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device had been established in October 2013, formed by integrating Hitachi and Hitachi Haramachi Electronics. It specialized in high-voltage, low-loss power semiconductor technologies—the kind of devices that sit in the brutal, high-heat, high-reliability environment between electricity and motion. Its three core product categories were IGBT and silicon carbide (SiC) devices, high-voltage ICs, and diodes.

Hitachi Ltd., based in Tokyo, agreed to transfer all shares of the subsidiary to MinebeaMitsumi. The transaction amount wasn’t disclosed publicly, though it was estimated to be around 40 billion yen.

The deal was expected to close by the end of March 2024. Then, on May 2, 2024, MinebeaMitsumi announced that it had completed both the acquisition of shares and the acquisition of business. Hitachi Power Devices was renamed Minebea Power Semiconductor Device Inc.—a quick signal that this wasn’t going to be held at arm’s length. It was going to be folded into the machine.

Strategically, the fit was straightforward. The company’s IGBT and SiC products were aimed at the decarbonization markets where demand was climbing fast: EVs, inverters for wind power generators, and railroad applications. Meanwhile, its high-voltage ICs served industrial and home appliance applications—helping improve system efficiency and reduce noise through motor control technology and software.

MinebeaMitsumi highlighted the technical depth it was buying: technologies like high-voltage SiC, high-voltage IGBT, SG (side gate)-IGBT for EVs, high-voltage ICs, and diodes for alternators—backed by strong development capabilities in power semiconductors.

But the bigger claim was about positioning. MinebeaMitsumi described the combination as a move that would accelerate industry reorganization and create an “all-Japan” group that could rank among the world’s top 10 in the growing power transistor field for IGBT and SiC. Kainuma also framed it as a milestone for the company’s broader semiconductor journey: adding Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device’s sales to MinebeaMitsumi’s existing base would take the group past 100 billion yen in semiconductor sales, a level he noted the company had reached within about six years.

What’s most revealing is how Kainuma explained the philosophy behind the bet. MinebeaMitsumi wasn’t trying to become a broad, everything-to-everyone semiconductor giant. His approach was deliberately bounded: because semiconductors were not the company’s main business historically, it wasn’t going to wager the company’s fate on them. The strategy, instead, was to find niche areas and aim for high margins.

He also characterized the deal as the final target in the “first act” of MinebeaMitsumi’s semiconductor M&A strategy. In the internal framework the company had been building since 2017, there had been four candidates. One deal didn’t happen. The last remaining fit—aligned with the original concept—was Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device.

From Hitachi’s side, the logic was that the subsidiary could grow further and enhance corporate value more effectively inside MinebeaMitsumi—particularly because MinebeaMitsumi positioned analog semiconductors as a core business and had already collaborated with Hitachi Power Devices for many years. Under the MinebeaMitsumi umbrella, the plan was to strengthen the high-voltage, low-loss technology edge, expand production capacity, and improve manufacturing efficiency—so it could ship more high-value products at larger scale.

There was also a key portfolio gap this acquisition filled. Up to that point, MinebeaMitsumi had been working to expand its IGBT business, but largely on the chip side. Module fabrication technology—and the back-end packaging processes and capacity that go with it—weren’t fully in place. With the acquisition completed, MinebeaMitsumi gained those back-end process technologies and production capabilities for packaging and module fabrication.

Stepping back, it’s hard to overstate why this matters. Power semiconductors sit at the center of electrification. Every EV needs them to convert and control energy from battery to motor. Wind turbines and solar inverters depend on them, too. So do rail systems and industrial infrastructure. By bringing Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device into the group as Minebea Power Semiconductor Device Inc., MinebeaMitsumi placed itself directly in the flow of the electric and green energy transitions—right where the world’s demand curve is bending upward.

IX. The Product Portfolio: Understanding the "Eight Spears" & Market Dominance

Seventy years after its founding, MinebeaMitsumi looked nothing like the company that started in a Tokyo neighborhood making tiny bearings. Along the way it moved into electronic devices and components, then reshaped itself through the integrations of Mitsumi Electric, U-Shin, and ABLIC. The result is a portfolio that’s hard to find anywhere else in the industrial world: ball bearings, motors, sensors, access products, and now semiconductors—built to work together.

But the heart of the company is still the same. The ball bearing business remains the crown jewel.

MinebeaMitsumi holds the top share in the global market for miniature and small-sized ball bearings—the kind with an outer diameter under 22 millimeters. In that category, it holds about 60% of the market. These are small parts with big consequences, quietly underpinning huge swaths of global manufacturing.

In automotive miniature ball bearings specifically, MinebeaMitsumi holds roughly 18% share. And this is where the demand curve has been bending upward. Electrification changes what “good” looks like in a vehicle: higher efficiency, less noise, tighter packaging, and more electric motors doing more jobs. That pushes automakers toward bearings that can handle high-speed rotation while staying quiet and reliable.

MinebeaMitsumi has been inside automotive systems since the early days of fuel injection, and it still holds the top global share of bearings for throttle body applications. Even here, the company’s advantage shows up in small engineering details—like developing a dedicated rubber seal with a special lip structure, because in the real world, performance often comes down to keeping contamination out and consistency in.

As EVs spread, the requirements get even tougher. MinebeaMitsumi developed a high-performance ball bearing aimed at quiet, smooth EV operation. It used optimized materials and advanced approaches like ceramic balls, a heat-resistant cage, and non-contact seals to enable high-speed rotation, faster motor response, and stronger resistance to electric corrosion. Ceramic balls cut inertia, helping acceleration and responsiveness, while the rigid heat-resistant cage helps maintain stability at high speeds.

All of that only matters if you can ship it—at scale, with consistency.

That’s where MinebeaMitsumi’s other enduring advantage kicks in: vertical integration paired with mass production. Ultra-precision machining can win you the spec sheet, but it doesn’t win you the market unless you can deliver a steady supply, year after year. And in many machines, bearings aren’t “a part.” They’re dozens of parts. Reliability and supply continuity become as important as micron-level tolerances.

Of course, MinebeaMitsumi doesn’t compete in a vacuum. The EV bearing market includes heavyweight rivals like Timken, NSK, Schaeffler, SKF, and NTN, each pushing innovations in lightweight materials, ceramic bearing technology, and precision engineering to improve performance and efficiency.

Meanwhile, the semiconductor business—once discussed internally as something that might be sold—has turned into a core growth pillar. MinebeaMitsumi now positions itself as an integrated precision components manufacturer: developing, making, and selling mechanical and electronic devices ranging from bearings and motors to sensors and semiconductors, all anchored by its ultra-precision machining DNA. That includes global market-leading products like its miniature ball bearings—and semiconductor products like 1-cell protection ICs for lithium-ion batteries.

X. The Kainuma Era: Leadership & Strategic Vision (2009–Present)

By the time MinebeaMitsumi started talking about INTEGRATION as its defining idea, it already had a leader who’d spent decades learning the company from the inside out.

Yoshihisa Kainuma joined the Company in December 1988. Over the years, he cycled through a long list of senior roles—running businesses, overseeing operations, and leading sales efforts across regions, including Europe and the Americas. He eventually served as Senior Managing Director, Managing Director, Senior Managing Executive Officer, Director of the Information Motor Business, Deputy Chief Director of Business, Chief Director of European American Regional Sales, Deputy Chief Director of Operation, and Chief Director of Operation.

That range matters. MinebeaMitsumi is a company where execution is strategy. The person at the top has to understand factories, customers, and global complexity—not just spreadsheets. Kainuma’s résumé reads like a deliberate tour through every part of the machine.

He became CEO in 2009, and the company’s posture became notably more aggressive and more systematic—especially on M&A. Since Kainuma took office, MinebeaMitsumi completed 23 M&As, effectively turning dealmaking into a core operating capability rather than an occasional event.

His background also shaped the style of leadership behind that pace. Kainuma’s legal education—unusual in a manufacturing CEO—showed up in the way MinebeaMitsumi approached big decisions: disciplined logic, careful structuring, and a comfort with complex transactions that many industrial companies avoid.

But the Kainuma era wasn’t only about what he bought. It was also about what he built next: a leadership bench and a succession path.

In a message written in the voice of the Company’s new President, MinebeaMitsumi described a transition to a new management structure. Under it, the former Representative Director, Chairman & President (CEO & COO) Yoshihisa Kainuma moved to Representative Director, Chairman CEO, while the former Senior Managing Executive Officer and CFO took on the role of President, COO & CFO. The President noted that Kainuma raised the idea early in the year, and that it came as a surprise—an honest signal that this shift wasn’t merely cosmetic, but a real handoff designed to prepare the next generation.

The Company framed the intent clearly: Kainuma had led with strong, centralized leadership, but now wanted to cultivate the next team under a new structure—without taking his hands off the wheel entirely.

The timing is not accidental, because the goals are enormous. MinebeaMitsumi set long-term targets of 2.5 trillion yen in net sales and 250 billion yen in operating income by the fiscal year ending March 2029. It also pointed to a nearer milestone—planning for 1.5 trillion yen in net sales in the fiscal year ending March 2025—and described the 2029 target as achievable.

To get there, the Company emphasized two ideas: first, it needed to sustain a 10% operating margin, a benchmark in the electronic components industry; second, it believed organic growth could take it to around 2 trillion yen in sales by 2029. The remaining gap to 2.5 trillion yen, it said, would likely require another major deal—something on the scale of the 2017 business integration with Mitsumi Electric.

That’s the Kainuma-era vision in a single sentence: build a company that can compound through both operational excellence and repeatable, high-conviction M&A—then ensure it can keep doing so beyond the founder-like CEO who engineered the run.

XI. Global Footprint & The Philippines Semiconductor Bet

By now, MinebeaMitsumi wasn’t just exporting precision parts to the world. It had become a global market leader in miniature ball bearings and high-precision components used across telecommunications, aerospace, automotive, and electrical industries—and it was building the kind of footprint you need if you want to be indispensable to all of them at once.

In that map, the Philippines has emerged as a strategic platform for the company’s semiconductor expansion—especially for the back-end work that turns wafers into shippable, customer-ready devices. MinebeaMitsumi received approval for a Global South Subsidy from the Japanese government to expand its semiconductor facilities in Cebu. The program was designed to strengthen supply chains for semiconductors and other priority industries, and MinebeaMitsumi’s inclusion was a clear signal that Japan viewed this capacity as strategically important. In parallel with a letter of intent signed in December 2023, the company also established a Global Support Center in the Philippines to train Filipino workers for deployment across its facilities worldwide.

The company put a public marker down on April 10, when it held a groundbreaking ceremony for a new building at the Cebu Mitsumi Danao Plant. The facility is positioned as a flagship site to boost analog semiconductor back-end capacity, supported by the Global South subsidy program. Cebu isn’t new for MinebeaMitsumi—since its establishment in January 1989, the plant has expanded steadily. It now employs about 20,000 people and produces a wide range of MinebeaMitsumi products, including semiconductors, camera actuators, and connectors.

The expansion isn’t just about adding square footage. Building No. 14, under construction at the Cebu Plant, is planned to include an approximately 8,000 square meter clean room on its second floor. Starting in 2027, MinebeaMitsumi expects to gradually launch a high-productivity line there for cutting-edge, thin semiconductor packages.

And the Philippines is only one piece of a broader Southeast Asia buildout. MinebeaMitsumi has said it plans to invest nearly 50 billion yen to build a factory in Cambodia and to increase solar power output at its plants in Thailand.

All of it fits the same macro trend: the geopolitics of semiconductor supply chains are pushing manufacturers to diversify away from China. Japan’s Global South initiative is designed to accelerate that shift, and the Philippines stands out as a practical partner—an English-speaking workforce, established electronics manufacturing infrastructure, and trade relationships that make global shipping and customer qualification easier.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In MinebeaMitsumi’s world, “starting up” isn’t really a thing. Ultra-precision manufacturing is an accumulated advantage—decades of process tweaks, tacit know-how, and hard-earned yield improvements that don’t transfer quickly. Even if a new entrant had the ambition, the upfront requirements are daunting: specialized machinery, tightly controlled production environments, and rigorous inspection and testing.

Then there’s the gate that matters most: qualification. In aerospace and automotive, you don’t win by showing a good sample. You win by proving reliability over time, through long validation cycles and demanding specifications. For something like an aerospace bearing supplier, customers need confidence measured in thousands of flight hours. That timeline alone keeps most would-be challengers out—and it keeps incumbents in.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Suppliers have leverage in areas like rare earth materials for motors and certain specialty steel alloys. But MinebeaMitsumi has spent decades building a counterweight: vertical integration. By producing many key inputs in-house, the company reduces exposure to supplier pricing and availability shocks. And for metals that are closer to commodities, there are generally multiple sourcing options.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

MinebeaMitsumi sells to some of the most powerful buyers on the planet—smartphone leaders like Apple, major automotive OEMs, and aerospace primes. They buy in volume, they negotiate hard, and they can push for aggressive pricing.

But leverage cuts both ways. Once a component is qualified and designed into a product—especially in safety-critical or high-reliability applications—switching becomes slow, risky, and expensive. That “designed-in” status creates real stickiness, even when buyers have the scale to demand concessions.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For most use cases that require precise rotational motion, ball bearings are simply the answer. Substitute technologies like magnetic bearings or air bearings exist, but they live in narrow, specialized niches. And in many of MinebeaMitsumi’s end markets, components aren’t just important—they’re mission-critical. Failure isn’t an inconvenience; it’s a serious event. That reality keeps substitution pressure low.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition is real and well-funded. In EV-related bearings, MinebeaMitsumi faces heavyweight rivals like Timken, NSK, Schaeffler, SKF, and NTN. Price pressure exists, especially in high-volume applications.

But MinebeaMitsumi’s position in miniature bearings gives it a defensible edge. In this corner of the market, quality, consistency, and reliability often matter more than shaving a fraction off unit cost—and the company’s scale and process discipline make it difficult for competitors to match both performance and supply at the same time.

XIII. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: STRONG

MinebeaMitsumi holds the world’s largest share in six product areas, including miniature ball bearings at roughly 65%. That kind of dominance doesn’t just look good on a slide—it changes the math of the business. High volume spreads fixed costs, improves purchasing leverage, and funds continuous investment in equipment and quality. Layer on the company’s scaled Asian manufacturing footprint and its deep vertical integration, and those scale benefits compound across the entire value chain.

Network Effects: WEAK

This isn’t a platform company, so classic network effects don’t really apply. The closest analogue is the way its product portfolio reinforces itself: bearings, motors, sensors, and semiconductors can be combined into integrated solutions, making MinebeaMitsumi more valuable to customers who want fewer suppliers and tighter integration. But that’s still a different dynamic than the self-reinforcing growth loops of a true network business.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Many Western competitors—SKF and Timken are good examples—built their operations, tooling, and sales engines around larger industrial bearings. MinebeaMitsumi’s edge comes from living at the other end of the spectrum: miniature, ultra-precision components where tolerances and consistency matter more than brute size. For a large-bearing incumbent to follow it there in a serious way would mean reshaping its business and potentially cannibalizing what already works. MinebeaMitsumi’s INTEGRATION approach adds another layer of separation: it’s not just selling a component, it’s combining mechanical and electronic capabilities into offerings that generalists struggle to match.

Switching Costs: STRONG

In the markets MinebeaMitsumi serves, switching suppliers is rarely a quick procurement decision. Aerospace qualification can take years, and automotive qualification runs on similarly long, unforgiving timelines. When parts are built to tight specifications—and then designed into a customer’s product and validated at scale—changing suppliers introduces risk to performance, reliability, and production schedules. That creates real lock-in, even when customers have bargaining power.

Branding: WEAK-MODERATE

MinebeaMitsumi isn’t a household name, and in a B2B components business, that’s normal. But within engineering and procurement circles, brand still matters—especially when failure is expensive. The NMB name carries credibility in bearing specifications, and the company’s reputation for quality and reliability functions as a practical form of brand equity in industrial sales.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Some of MinebeaMitsumi’s advantage is rooted in assets that can’t be easily copied. Decades of experience and relationships in Thailand have created a manufacturing base with deep, learned capability—not just headcount. The company’s founding DNA—aircraft engineers forced to channel aerospace precision into civilian components—still shows up in its culture and standards. And the accumulated know-how in ultra-precision machining is the kind of resource competitors can’t simply buy; it has to be earned over time.

Process Power: STRONG

This is the company’s signature. MinebeaMitsumi’s advantage isn’t a single patent or a one-time breakthrough—it’s decades of compounding process improvement that enables repeatable manufacturing at extremely tight tolerances. The mother factory system is a key part of that: Japan develops and refines the know-how, then transfers it to high-scale production across Asia with consistent standards. Those processes are hard for competitors to see from the outside, and even harder to replicate at scale—exactly what makes process power so durable.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators and Investment Considerations

If you’re trying to understand whether MinebeaMitsumi’s story is still compounding the way management says it will, there are three KPIs that do a lot of the work.

1. Operating Margin Progression

The company has been explicit that boosting earnings power and profit margins is the critical management challenge. For the fiscal year ended March 2024, operating income was 73.5 billion yen, and the operating margin on a pro-forma basis was a modest 5.2%.

The stated goal is to reach a 10% operating margin by fiscal 2029—nearly double where it stood. This isn’t just a finance target. It’s a scoreboard for whether INTEGRATION is actually producing higher-value products and whether acquisitions like Mitsumi, ABLIC, U-Shin, and Hitachi Power Devices are being absorbed into a more efficient whole. The simplest way to check progress is to watch the margin trend quarter by quarter and see whether it’s moving in the right direction.

2. Ball Bearing Market Share in EV Applications

MinebeaMitsumi holds about an 18% share in miniature ball bearings for the automobile sector—a strong position in a market that’s being reshaped by electrification.

As vehicles add more electric motors and demand quieter, higher-speed, higher-reliability components, bearings become an even more strategic part of the bill of materials. The question isn’t whether EVs grow. It’s whether MinebeaMitsumi can defend—and ideally expand—its share as platforms transition and competitors fight for the same designs.

3. Analog Semiconductor Revenue Growth

Semiconductors are the biggest growth opportunity in the portfolio, and also where execution risk is highest. Management has set an ambitious objective: to build an analog semiconductor business that exceeds 300 billion yen.

This KPI is a reality check on whether the company can turn its semiconductor expansion—especially the integration of Hitachi Power Semiconductor Device—into scale, momentum, and durable profitability, rather than just a bigger list of products.

XV. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

MinebeaMitsumi sits in a rare sweet spot: essential, everywhere, and almost never noticed. The EV transition doesn’t disrupt that position—it amplifies it. EVs pack in more motors than internal combustion cars, and those motors need precision bearings. The power electronics that make EV drivetrains work need power semiconductors. And as vehicles move toward keyless entry and smarter security, “access” becomes a tight blend of mechanical reliability and electronics. In that world, MinebeaMitsumi’s core advantage—the ability to combine bearings, motors, sensors, and semiconductors into integrated offerings—starts to look less like a nice-to-have and more like a structural edge.

From there, the company’s fiscal 2029 targets—2.5 trillion yen in sales and 250 billion yen in operating income—become a plausible outcome rather than a stretch slogan. Management believes organic growth can take the business to roughly 2 trillion yen, with one more major, Mitsumi-scale deal filling the remaining gap. If MinebeaMitsumi can also prove that INTEGRATION translates into sustainably higher margins, the market could reward it with a higher valuation multiple as confidence in the story catches up to the operational progress.

Bear Case:

The biggest swing factor is semiconductors. MinebeaMitsumi is expanding into a field where the incumbents are deep-pocketed specialists, and power devices are a brutally competitive arena. Kainuma’s framing is telling: because semiconductors are not the company’s historical main business, it isn’t going to wager the company’s fate on them. That caution is sensible—but it’s also an implicit admission that this move carries real execution risk, especially as competition from European and Chinese players continues to intensify.

Then there’s profitability. The company’s operating margin has been sitting around the mid-single digits, which reflects the reality of cost-sensitive, fiercely contested end markets. Getting to a 10% margin by 2029 requires multiple things to go right at once: cost reductions, a better product mix, and real synergy capture from large, complex integrations. Any misstep—whether in ramping new semiconductor capacity, integrating acquisitions, or winning the right high-value designs—could push the timeline out and keep returns muted.

Finally, the manufacturing footprint cuts both ways. Thailand has been a massive source of scale and capability, but with more than 20% of production tied there, it also creates concentrated exposure to regional disruption. Expansion in places like the Philippines and Cambodia helps diversify risk, but the company still carries meaningful operational dependence on Southeast Asia.

XVI. Conclusion: The Hidden Champion's Next Chapter

MinebeaMitsumi is a distinctive kind of industrial company: a hidden champion that reached global scale while staying almost completely invisible to end customers. And if you listen to how leadership talks about the future, the ambition isn’t to become famous. It’s to become even more essential.

Even as the company grows, the argument is that its edge doesn’t have to change: the group’s strengths, its speed, and its belief that “passion” is what shapes the future. The idea is simple—set targets that feel uncomfortably high, push toward them relentlessly, and build an organization that can move as one. That’s the spirit behind the corporate slogan: Passion to create value through difference. In that framing, the fiscal 2029 goal—2.5 trillion yen in net sales and 250 billion yen in operating income—isn’t just a number. It’s the outcome of a culture that’s trained to take on hard problems.

From the dreams of displaced Manchurian aircraft engineers in 1951 to a global precision-components powerhouse in 2025, MinebeaMitsumi navigated seven decades of disruption, competition, and geographic reinvention. A hard disk drive motor business that once looked like a threat became a lesson in how fast end markets can change. In its place came the tailwinds of electrification and decarbonization. And a company once defined almost entirely by ball bearings expanded into motors, sensors, semiconductors, and access solutions—without letting go of the ultra-precision manufacturing DNA that made it valuable in the first place.

That sets up the strategic question for the next chapter: can MinebeaMitsumi expand deeper into semiconductors while maintaining the manufacturing excellence and operational discipline that got it here? The company has shown it can acquire and integrate. But power semiconductors are a different arena—more capital-intensive, more technologically unforgiving, and filled with well-funded global competitors, not just fragmented niches waiting to be consolidated.

Kainuma’s own management philosophy points to what he believes will matter most: sustainability. Over roughly fifteen years, the focus was on scale—because scale, if executed well, can drive higher profits and improve earnings per share. At the same time, the company leaned into INTEGRATION: not simply collecting businesses and product lines, but combining the group’s resources to create new value customers can’t easily source elsewhere.

MinebeaMitsumi now sits at the intersection of multiple secular growth trends: electric vehicles, renewable energy, advanced automation, and connected devices. Whether it can convert that position into sustained profit growth—and prove that INTEGRATION translates into durable economics—will determine whether the next chapter can match the extraordinary trajectory of the last fifteen years.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music