Daifuku Co., Ltd.: The Hidden Giant Powering Global Automation

I. Introduction: The Invisible Backbone of Everything You Buy

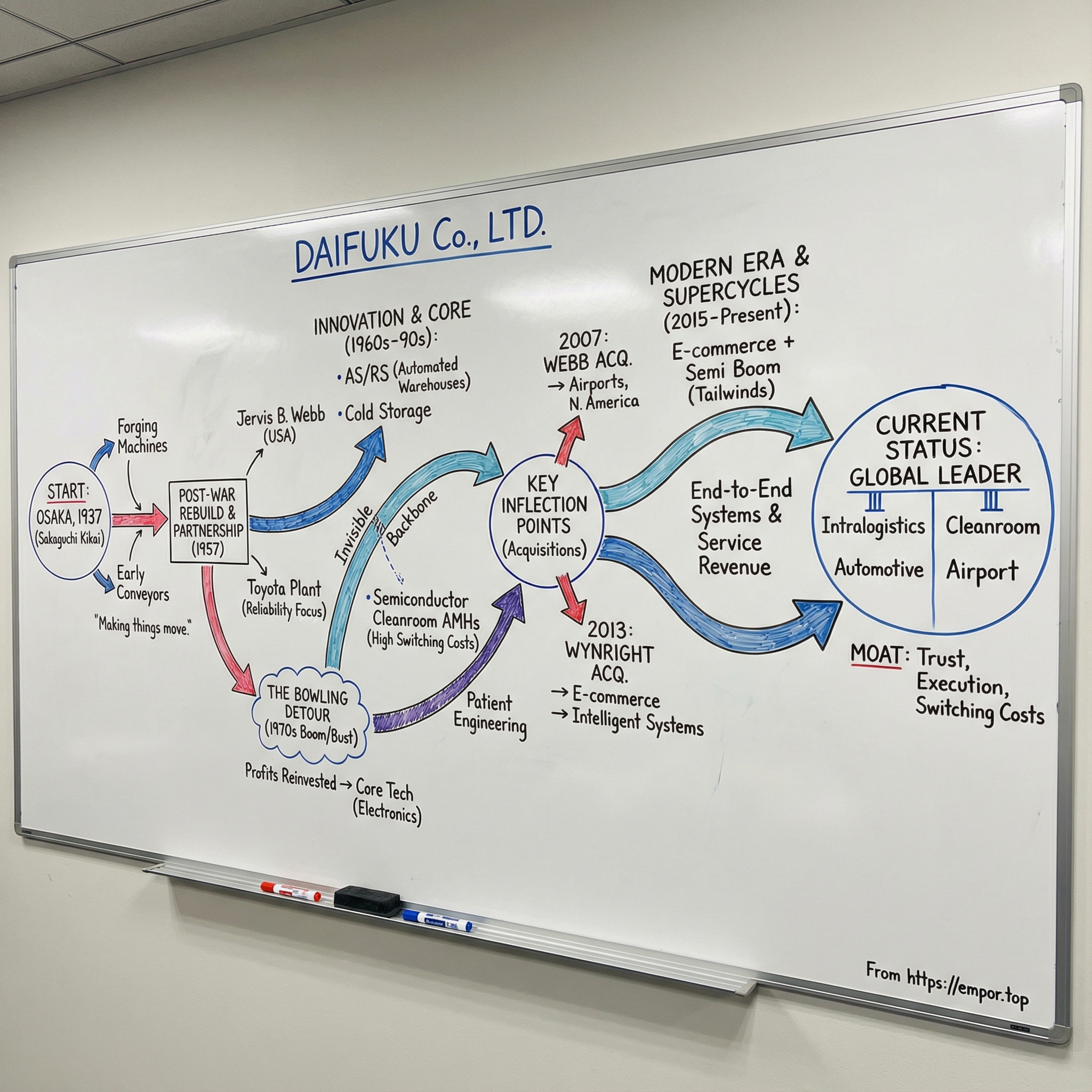

Picture this. A semiconductor wafer carrying the circuitry for the next generation of iPhone processors glides through a nitrogen-purged cleanroom in Taiwan. A few thousand miles away, that future phone, now in a Prime box, races through a fulfillment center in Kentucky. Meanwhile, at Frankfurt Airport, a suitcase disappears into a maze of conveyors and scanners, then reappears on the right flight minutes later.

The common thread isn’t Apple, Amazon, or Lufthansa. It’s a company you’ve probably never heard of: Daifuku.

Daifuku Co., Ltd. is a Japanese material-handling equipment company founded in 1937 in Osaka. By 2017, it was the leading material handling system supplier in the world. And that wasn’t a one-off. According to Modern Materials Handling, Daifuku held the number-one spot for the ninth consecutive year.

Here’s the paradox at the center of this story: Daifuku helps power the most advanced edges of the modern economy—e-commerce fulfillment and semiconductor fabrication—yet it began in Imperial Japan building forging machines for ironworks. Over the decades, it became the quiet specialist in making things move: components inside cutting-edge chip factories, inventory inside enormous distribution centers, and bags inside airport terminals. Today, more than 500 airports around the world rely on Daifuku’s technology and services for baggage handling systems.

So how did a small Osaka machinery shop become the invisible backbone of global logistics? That’s the question we’re going to answer. This is a story about patient Japanese engineering, about making a few key bets at exactly the right time, and about turning decades of accumulated know-how into something that’s very hard to replicate. Along the way, we’ll hit the bowling boom that nearly pulled the company off course, the half-century partnership that eventually became an acquisition, and the supercycles—chips and e-commerce—that made Daifuku feel less like an equipment vendor and more like critical infrastructure.

And if you’re looking at Daifuku through an investor lens, the appeal is straightforward. The moat isn’t a single patent or a flashy consumer brand. It’s trust, execution, and switching costs. When your entire operation depends on systems that have to run essentially all the time—when downtime can ripple through a whole supply chain—you don’t swap out the company behind that system on a whim.

II. The Origin Story: Osaka, 1937

In 1937, Japan was accelerating into an era of heavy industry. Military production was ramping, factories were expanding, and Osaka—already a commercial engine for the country—buzzed with the noise of machines and ambition. In that environment, two engineers, Yoshihiro Doi and Hamao Ueda, spotted a simple, stubborn problem inside factories: making things move efficiently.

On May 20, 1937, they founded the company in Osaka to mechanize the flow of materials on the factory floor. The early products were straightforward but essential—chain and belt conveyors—and from day one, they paired the hardware with installation and maintenance to improve productivity, quality, and safety. They built for durability and modularity, aiming for systems that could be adapted across different industries rather than one-off contraptions.

The company began under the name Sakaguchi Kikai Seisakusho Ltd. It wasn’t a tiny workshop, either: about 150 employees and a factory on a 3,300 m² site in Owada (now Chibune) in Nishiyodogawa-ku, Osaka. And while Daifuku would become synonymous with moving goods, its earliest work reflected the needs of pre-war Japan’s industrial buildup—forge rolling machinery for ironworks, along with air hammers and forging machines. These were the muscular tools of manufacturing, built for an economy that was trying to scale fast.

The “Daifuku” name came later, but the evolution tells you something about the company’s roots and trajectory. It moved from Sakaguchi Kikai Seisakusho to Kanematsu Kiko in 1944, then to Daifuku Machinery Works Co., Ltd. in 1947. The modern name, Daifuku Co., Ltd., has been used since 1984. And that name carries a double meaning: in Chinese it can mean “bring you good fortune,” and inside the company it nods to geography—“Dai” referencing Osaka, and “fuku” referring to Fukuchiyama in Kyoto Prefecture, the second production location at the time.

But the real differentiator wasn’t what Doi and Ueda built. It was how they built the business around it. From the beginning, Daifuku didn’t just ship machines—it bundled design, fabrication, installation, and maintenance into a single offering. In other words, they weren’t trying to be a catalog vendor. They were trying to own the outcome: a factory that moved faster, safer, and more reliably because Daifuku stood behind the system end to end.

The founding vision was almost deceptively modest: mechanize material movement inside factories. At a time when labor was available but output was limited by inefficiency, that focus was a wager that “flow” would become a competitive weapon. They were right. They just couldn’t have known that the same impulse—get the right thing to the right place, at the right time, with near-zero error—would one day underpin airports, e-commerce, and the most advanced semiconductor fabs on Earth.

III. War, Reconstruction & The American Connection (1945-1970)

World War II devastated Japan’s industrial base. But in the wreckage, a new priority took hold: rebuild, modernize, and do more with less. For a company like Daifuku—already obsessed with the mechanics of flow—those years were an unlikely tailwind. Wartime constraints and postwar reconstruction pushed factories to mechanize wherever they could, and the habits formed in the 1940s and 1950s—standardization, frugal engineering, ruthless attention to throughput—became the technical discipline Daifuku would draw on for decades.

Then came the hinge year: 1957.

In 1957, Daifuku entered into a technical affiliation for chain conveyors with Jervis B. Webb International Co., a U.S. company and one of the world’s top conveyor manufacturers. This wasn’t a simple “license and ship” arrangement. It was a technology partnership—American conveyor expertise paired with Japanese manufacturing execution.

Webb’s credentials were formidable. Founded in 1919, the company helped develop the rivetless chain conveyor, a breakthrough that made it possible to move automobile bodies smoothly through assembly and finishing. After Henry Ford adopted the technology in the early 1920s, it became one of the quiet enablers of modern mass production.

And the timing in Japan was perfect. The late 1950s were when Japanese automakers began true mass production. By 1957, domestic output had climbed to roughly 182,000 vehicles—about three times the level in 1955. Webb-type chain conveyors, long proven in the United States, were now arriving in Japan at exactly the moment the industry needed them.

Daifuku quickly put that partnership to work. In 1959, it supplied a Webb conveyor system to Toyota Motor Co., Ltd.’s Motomachi Plant in Toyota, Aichi Prefecture—a new factory built exclusively for passenger cars, and widely seen as a landmark project: Japan’s first modern automobile factory. Construction began in 1957, and the plant was scheduled to start operations at 8:00 a.m. on August 8, 1959.

The night before launch, things nearly went sideways. On August 7, during a trial run, part of the conveyor system didn’t move. It’s the kind of failure that can stain a supplier for years—especially on a flagship facility. Daifuku’s team worked through the night, fixed the issue, and the plant opened on schedule the next morning.

That episode captures something central about Daifuku’s DNA. In this business, you don’t win by promising. You win by showing up, solving the problem, and making the line run.

The Webb relationship endured because it was built on real mutual advantage. Webb manufactured and sold chain conveyor technology that Daifuku credits with materially advancing Japan’s auto industry, and the two companies maintained a close partnership for decades. They also didn’t step on each other’s toes: there was little overlap in customers or offerings, and both saw themselves as system builders with a similar culture.

Looking back, it’s easy to treat 1957 as a historical footnote—a technical affiliation, a successful plant launch. But it was more than that. It was Daifuku learning from a global pioneer, absorbing the playbook, and building the execution muscle that would later let it expand far beyond conveyors. The seeds planted in that partnership wouldn’t fully flower until much later—but the roots of Daifuku’s moat were already taking hold.

IV. The Bowling Detour: A Lesson in Strategic Focus

Every long-running industrial success story seems to have at least one weird chapter. For Daifuku, it was bowling.

In early 1970s Japan, bowling wasn’t a niche hobby. It was a national obsession that had been building since the early 1960s and peaked around 1972, when as many as 10 million people played. And right in the middle of that consumer craze was a company best known for moving parts around factories.

The scale was wild. Between 1960 and 1972, Japan installed more than 120,000 bowling lanes. By 1972, the country had about 124,000 lanes—second only to the United States at 130,000. In a little over a decade, Japan had nearly matched America’s bowling footprint.

Daifuku became a major supplier of the machines that made those lanes actually work. One of the most famous installations was the Shinagawa Bowling Center in Tokyo, a 120-lane behemoth that was the largest bowling alley in the world at the time. At the opening ceremony, Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda’s daughter rolled the first ball. Then, more than a hundred players released their balls simultaneously—and all the pin-setting machines snapped into motion at once. People who were there called it “a truly magnificent and thrilling spectacle.”

As strange as it sounds, the move made technical sense. A pinsetter is basically a compact material-handling system: retrieve objects, sort them, and put them back precisely, over and over again. Daifuku’s core skill wasn’t “conveyors.” It was repeatable motion, reliability, and automation. Bowling just happened to be a consumer-friendly packaging of the same engineering DNA.

And for a moment, it worked almost too well. In fiscal 1972, bowling machines made up 72% of Daifuku’s net sales—more than two-thirds of the entire company.

Then the boom ended, fast. By the mid-1970s, the market had turned and the bowling craze collapsed. Lane count fell from about 124,000 to 23,000. It was a breathtaking reversal.

Daifuku took the hit—sales and profits dropped sharply—but the aftermath is what makes this detour so instructive. Instead of chasing the next fad, the company used the profits it had already banked to strengthen its foundation: securing a large factory site in Hino, Shiga Prefecture, which became its current mother factory, and making upfront investments in computers and electronics. When the bowling wave receded, Daifuku moved back to its core: material handling systems.

That’s the lasting lesson of the bowling era. It proved Daifuku’s capabilities could travel—today you see the same pattern in semiconductors and airports. But it also showed something rarer: the discipline to take an unexpected windfall, reinvest it into long-term capability, and walk away when the market stopped making sense.

Bowling machines also had one operational advantage: unlike made-to-order systems, they could be produced on a plan. But that “managerial merit” only exists as long as demand holds. The moment demand evaporated, the planning advantage vanished with it—and Daifuku learned, in the most dramatic way possible, why it ultimately preferred infrastructure markets over consumer trends.

V. The First Major Inflection: AS/RS and Semiconductor Cleanrooms (1966-1990s)

Even as bowling machines dominated Daifuku’s revenue in the early 1970s, the company was quietly building something far more enduring. The automated warehouse business—the engine that would eventually become its largest segment—really began in the mid-1960s.

In 1966, Daifuku introduced its first Automated Storage and Retrieval System, or AS/RS. It was the start of a long, steady climb into a category where trust is earned the hard way: by keeping mission-critical facilities running, year after year. Over the decades, Daifuku delivered more than 34,000 AS/RS cranes worldwide—an installed base that speaks to both scale and staying power.

The early milestones mattered because they weren’t incremental. In 1966, Daifuku delivered the Rackbuil System—essentially a rack-supported building with an AS/RS—to the Electric Motor Department of Matsushita Electric Industry, widely regarded as Japan’s first automated warehouse. They also began unmanned operations with a stacker crane called Rack Master, which managed storage positions using X, Y, and Z coordinates and could be operated with a computer. Then, in 1969, Daifuku delivered Japan’s first fully automated, computer-controlled Rackbuil System to the Nobeoka Plant of Asahi Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.

To understand why this was such a leap, you have to remember what warehouses looked like at the time. Single-story buildings were the norm. Loading, unloading, and storage were largely manual. Inventory lived in ledgers and slips. The idea that a warehouse could be tall, dense, computer-managed, and largely unmanned wasn’t just a better process—it overturned what “warehousing” meant.

Then came the cold.

In 1973, Daifuku delivered its first refrigerated AS/RS as demand for frozen foods grew. This system automated storage and retrieval in a warehouse as cold as −40°C. Daifuku designed and deployed freezer-capable AS/RS technology that could operate at that temperature, and while its standard product line was later rated to −30°C, the company continued to offer customized solutions capable of reaching −40°C when required. Shortly after that first installation, Daifuku built a large-scale refrigerated AS/RS with 20 storage and retrieval machines—one that remains in operation today.

That detail is the point. A system installed in the 1970s still running isn’t just “good engineering.” It’s a strategic asset. When customers choose an automation backbone for a warehouse or factory, they aren’t making a one-time equipment purchase. They’re choosing a long-term partner—and Daifuku built its reputation on systems that last.

But the most transformative shift arrived in the 1980s, when semiconductor manufacturing began scaling and cleanroom requirements got brutally strict. Demand for cleanroom transport systems increased rapidly, and Daifuku leaned into what would become its most technically demanding business: cleanroom automated material handling systems, or AMHS.

Daifuku’s cleanroom AMHS automates transport inside semiconductor and flat panel plants around the world. The work sounds simple—move wafers and delicate components from tool to tool—but the constraints are extreme. The system has to produce minimal dirt, keep vibration low, and deliver top-tier reliability. In recent years, technologies like nitrogen purging and air flotation supported the industry’s push toward smaller, more advanced semiconductors and sharper flat panel displays.

One of the most interesting parts of this story is how Daifuku got there. The overhead monorail system Cleanway evolved from TELELIFT, a system originally used to convey medical records in hospitals, books in libraries, and documents at airports. It’s a masterclass in adjacent innovation: take a core capability—reliable, precise overhead transport—and harden it for a new environment until it can survive the cleanest, most demanding factories on Earth.

Semiconductor cleanroom systems became strategically valuable for three reasons. First, the requirements are unforgiving; few companies can meet the contamination, vibration, and reliability standards consistently. Second, switching costs are enormous—changing the AMHS provider in a fab isn’t like swapping a vendor; it risks disruptions to production lines worth billions of dollars. Third, the buyer base is concentrated among manufacturers who demand proven performance, not promises.

Daifuku emerged as the global leader in the AMHS market by specializing in highly automated, integrated systems for major semiconductor manufacturers. Its cleanroom solutions are designed to be reliable, scalable, and precise, with an eye toward future needs like wafer size expansion. And through ongoing R&D—using tools like AI and digital twins—it pushed predictive maintenance and system efficiency further, reinforcing the same theme that’s been present since those early conveyor days: in material handling, the winners are the ones who make the whole system run.

For Daifuku, that meant the cleanroom business wasn’t just a new product line. It was a moat—built on technical difficulty, long lifecycles, and the kind of customer relationships you only get when failure is not an option.

VI. Key Inflection Point #1: Acquiring Jervis B. Webb (2007)

For fifty years, Daifuku and Jervis B. Webb operated as something rare in industrial America and Japan: true long-term partners. They shared technology, served largely different customers, and stayed independent.

In 2007, that changed. Jervis B. Webb Company announced an agreement to sell 100 percent of its outstanding shares to Daifuku, and the transaction closed in December 2007.

In a real sense, the student became the owner. Daifuku acquired the U.S.-based company that had helped shape its early conveyor know-how—and in the process gained a major foothold in a new, mission-critical category: airport baggage handling systems, primarily in North America.

Daifuku’s rationale was straightforward and very on-brand: expand overseas, and do it in a way that improves execution near customers. The acquisition supported Daifuku’s three-year business plan launched in April 2007, which emphasized strengthening and expanding its global presence. As Katsumi Takeuchi, Daifuku’s president and CEO at the time, put it: “The complementary and supportive cultures of Daifuku and Webb will strengthen operations for both companies and help us grow internationally.” Daifuku had long believed production and procurement should sit close to the customer; Webb made that strategy far more tangible in the United States.

Webb also arrived with advantages Daifuku couldn’t simply build overnight: a strong brand reputation in the U.S., deep labor resources across North America and offshore, and long-standing customer relationships.

And while the headline was “Daifuku buys its partner,” the deeper story was that Webb had become more than an automotive conveyor company. Over time, it expanded into airport baggage handling systems, automatic guided vehicles, and automated storage systems. So this wasn’t just Daifuku buying a legacy conveyor business—it was Daifuku buying an expansion platform.

That platform mattered most in airports. In April 2010, Daifuku announced a three-year plan called “Material Handling and Beyond,” explicitly committing to airport baggage handling as a core business. Then, in April 2011, the Group acquired Logan Teleflex, a baggage handling systems and services provider with strength in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

The strategic logic is easy to see when you think about what baggage handling actually is: warehouse automation under harsher conditions, with higher public visibility. It’s conveyors, sortation, scanners, and software—except the “warehouse” is a live airport, and the “customers” are airlines and passengers who notice instantly when something breaks. These are long-lived infrastructure systems with predictable upgrade cycles, heavy service requirements, and massive switching costs. No airport wants to be known for lost bags, and no airport wants to rip out a working system unless it absolutely has to.

Daifuku ultimately became a leading provider of end-to-end baggage handling solutions, supporting projects from conception and installation through maintenance. More than 500 airports around the world depend on its technology and services to move bags reliably behind the scenes—and to keep the passenger experience on track out front.

Over time, Daifuku’s airport business grew into a three-continent footprint through specialized subsidiaries across North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific. It also broadened the scope of what it could deliver: baggage handling equipment, operation and maintenance, and self-service baggage check-in systems.

For investors, the Webb acquisition is a clean example of Daifuku’s pattern at its best: buy something that fits the core competency, expands the addressable market, and reinforces the moat through service and switching costs. And crucially, Daifuku didn’t try to “fix” Webb with a heavy-handed integration. It kept substantial autonomy where it mattered, while still capturing the advantage of shared engineering capability and a broader global customer base.

VII. Key Inflection Point #2: Wynright Acquisition & Value Innovation 2017 (2013)

If Webb gave Daifuku airports and a much deeper bench in North America, Wynright was the move that positioned it for the next wave: e-commerce fulfillment.

On August 15, 2013, Daifuku Webb and Wynright reached a definitive agreement for Daifuku Webb to acquire privately owned Wynright. Under the terms of the deal, Wynright would operate as a wholly owned subsidiary.

Wynright wasn’t just another conveyor company. It was a U.S.-based provider of what the industry likes to call “intelligent” material handling: conveyor and sortation systems, voice- and light-directed picking, warehouse controls and execution software, robotics, mezzanines, and the physical structures that turn a big empty box into a working fulfillment operation.

The deal fit neatly into Daifuku’s new corporate management plan, Value Innovation 2017, which had begun in April 2013. The plan’s ambition was simple on paper and hard in practice: grow sales, lift operating margins, and become the kind of partner customers depend on for full solutions, not just equipment.

Wynright had credibility in exactly that role. Founded in 1972, it had built a reputation helping large, fast-growing customers use space more efficiently and improve productivity—practical, operational know-how that matters when you’re designing facilities that have to work from day one.

It also changed the shape of Daifuku in North America. Wynright designed and manufactured systems for apparel and footwear, cold storage commerce, e-commerce, and food and beverage. Its lineup ranged from truck and container loading and unloading equipment to palletized trailer loading and robotic truck loading, plus robotic storage and retrieval systems, racks, conveyors, AS/RS, carousels, and replenishment products. In other words: not a single product, but a toolkit for building modern distribution and fulfillment centers.

The timing couldn’t have been better. E-commerce was accelerating, and the logistics world was being forced to re-learn how to move goods. Shipping pallets to stores is one kind of operation. Shipping individual orders to homes is a completely different one—more picks, more sortation, more speed, less tolerance for error. Wynright’s strength in high-velocity order fulfillment gave Daifuku a front-row seat to that transition.

After Wynright joined the group in October 2013, Daifuku began seeing orders for manufacturing and distribution systems increase outside Japan. In North America, Wynright contributed to earnings. Earnings were also supported by projects elsewhere, including a large order from the e-commerce and cosmetics sectors in South Korea.

Over time, the Wynright acquisition became a foundation for broader capability-building in the region: strengthening integration and conveyor manufacturing, and then investing further into areas like AMR and AGV, warehouse software (WMS and WCS), and micro-fulfillment.

For investors, Wynright is a clear example of Daifuku’s playbook. Instead of trying to organically develop e-commerce fulfillment expertise from scratch—slowly, expensively, and with plenty of execution risk—Daifuku bought a proven platform with real customer relationships and folded it into the larger Daifuku system. The payoff was speed: accelerated entry into a market that was taking off right as the deal closed.

VIII. The E-Commerce & Semiconductor Supercycle (2015-Present)

From about 2015 onward, Daifuku caught two of the biggest tailwinds in the global economy at the same time: e-commerce scaling into a default way people buy things, and semiconductors entering an era of relentless capacity expansion. For a company whose entire craft is moving physical objects with near-zero error, it was the perfect moment to look less like an industrial supplier and more like infrastructure.

A big part of why Daifuku benefited so directly is that it doesn’t just sell equipment. It shows up as the systems partner. Daifuku designs and integrates the full material-handling stack around its core products—automated storage and retrieval systems, pallet racks, conveyors, sortation, automated guided vehicles, and the software layer that tells everything where to go, when to move, and how to recover when something goes wrong. That end-to-end posture let it translate decades of factory know-how into the warehouse and distribution world, right as e-commerce demand pushed operators to automate faster and at larger scale.

That shift is visible in the business mix. Intralogistics—systems for e-commerce and distribution—became Daifuku’s largest segment, powered by customers racing to build automated fulfillment centers that can ship faster and rely less on increasingly scarce labor.

The results followed. Fiscal 2022 marked Daifuku’s third consecutive year of record revenue, reaching 590 billion yen (US$4.55 billion). The drivers weren’t mysterious: a large order backlog rolling in, strong sales into semiconductor manufacturing, expansion in retail and commerce, and higher service revenue as the installed base kept growing.

Semiconductors were the other engine. The cleanroom business rode powerful capex cycles, and by fiscal 2024 Daifuku was still seeing strength in orders—helped by cleanroom systems demand in Asia and airport systems in North America. In the same period, operating income, ordinary income, and net income attributable to shareholders all set new highs for three years in a row, with net income margin reaching the 10% range for the first time.

What’s just as important as the demand is what Daifuku did operationally to capture it. The company kept expanding its ability to build close to customers. In the United States, Daifuku planned to double production capacity for intralogistics systems by the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, aiming to grow sales and share by leaning into local self-sufficiency. In India, Daifuku Intralogistics India Pvt. Ltd. built a new manufacturing plant in Hyderabad, launching full-scale operations in April 2025 and expanding production space to about four times its previous capacity.

Underneath all of this is a quieter, more durable shift: monetizing the installed base. Multi-year operations and maintenance contracts, software sold in modules, retrofit cycles that tend to come every five to ten years, and cross-selling upgrades—adding shuttles or AMRs to an existing conveyor-heavy site—are what turn a one-time project into a long-lived revenue stream. As e-commerce warehousing recovered after 2023, airport upgrade cycles stayed active, and semiconductor AMHS orders rebounded alongside AI-driven and advanced-node investment, those levers helped support both new orders and aftermarket prospects.

This is why services and software matter so much in Daifuku’s model. As the company’s installed base grows, aftermarket and service naturally become a larger piece of the business. Strategically, that recurring revenue smooths the cycle and deepens customer lock-in, because the relationship doesn’t end at commissioning—it continues through uptime guarantees, performance tuning, and the next round of upgrades.

For investors, this era highlights the advantage of Daifuku’s portfolio. Demand doesn’t move in a straight line—e-commerce spending can cool, semiconductor capex can swing, and airports modernize on their own timelines. But Daifuku is exposed to all of them. When one cycle softens, another can strengthen. The result is a company that still participates in big growth waves, but with less reliance on any single one.

IX. Modern Operating Model & Business Segments

To understand Daifuku today, you have to stop thinking of it as a single “automation company” and start thinking of it as four businesses that reinforce each other.

The biggest is Intralogistics—warehouse and distribution automation for retailers, manufacturers, and the e-commerce economy. Next is Cleanroom, where Daifuku moves wafers and panels through semiconductor and flat panel factories. Then Automotive, the company’s original proving ground for production-line systems. And finally Airport Technologies, where baggage handling turns Daifuku’s core competency—moving items reliably through complex networks—into public-facing infrastructure. Regionally, North America and Japan lead, with meaningful operations across Europe, the Middle East and Africa, and Asia outside Japan; China tends to be more cyclical.

What unifies those pillars is breadth. Daifuku sells into e-commerce, retail, wholesale, transportation, warehousing, food, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, energy, medical, and rail—anywhere that “stuff” has to move with speed and precision. The product set reflects that: manufacturing and distribution systems, semiconductor and flat panel production line systems, automobile production line systems, airport technologies, and even car wash machines.

That scope isn’t powered from a single headquarters. Daifuku runs through a network of 61 consolidated subsidiaries worldwide, organized around the regions and product lines where local engineering, manufacturing, and service matter most.

The result is a genuinely global footprint and real market share. Daifuku holds an estimated 15% of the worldwide material handling system market. Sales skew toward Asia-Pacific, at roughly 45% of the total. The U.S. is a priority market, contributing 40.7 billion yen in net sales—25% of the company total—in the first quarter of fiscal year 2025. Europe is also important, especially in automotive and airport projects.

But the most important shift in the modern model isn’t where Daifuku sells. It’s how it gets paid after the initial system goes live.

Service deserves its own spotlight. Multi-year operations and maintenance contracts, software sold in tiers and modules, retrofit cycles that often arrive every five to ten years, and cross-selling opportunities all help turn a big, one-time project into recurring revenue. Daifuku wins new customers with technical credibility and proven delivery, then keeps them through performance-guaranteed service agreements where uptime is the product.

Zoom out, and the operating model is simple: design, manufacture, and integrate an end-to-end system—then monetize the installed base through installation, maintenance, spare parts, and software. Daifuku positions itself as a turnkey partner across consulting and design, in-house manufacturing, the software layer (WMS, WCS, SCADA), system integration, installation, and round-the-clock lifecycle support.

That integration creates the compounding advantage. Customers get single-source accountability when the system has to work. Daifuku gets deeper relationships, earlier insight into expansions and upgrades, and a service business that grows as the installed base grows. Better service leads to more trust, more trust leads to more system wins, and every new system seeds more service revenue.

For investors, this is the modern Daifuku in one line: market leadership across multiple end markets, with a growing mix of software and service that increases predictability and supports stronger margins.

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Daifuku sits in a part of the industrial world that people often assume is a race to the bottom: big projects, lots of steel, plenty of competitors. But when you look at the structure of the industry—who can realistically compete, how often customers switch, and what “failure” actually costs—the picture changes. Porter's Five Forces helps explain why Daifuku can earn attractive returns in markets that, from the outside, look commoditized.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into Daifuku’s core markets is harder than it looks. End-to-end warehouse automation projects typically require $2–4 million of capital per site, which alone filters out most would-be entrants.

But the real barrier isn’t just money. It’s time and credibility. Daifuku’s reputation for continuous improvement and long-term reliability has been built over roughly six decades, across thousands of live systems. That creates an advantage you can’t shortcut with a clever pitch deck.

And in cleanroom and semiconductor AMHS, the walls are even higher. Customers want certifications, proof, and a track record in environments where contamination and vibration can ruin yield. That kind of trust takes years to earn—and one bad installation can end a supplier’s chances for a decade.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Daifuku relies on specialized components, but it isn’t trapped by a single dominant supplier. Its global scale gives it purchasing leverage, and regional manufacturing helps reduce supply chain exposure.

There are also practical geopolitical considerations. Some products and components sourced from outside the United States are subject to U.S. tariffs, but most intralogistics, automotive, and airport systems for the U.S. market are produced domestically, which limits the impact and gives Daifuku more control over cost and delivery.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-LOW

Daifuku’s customers are sophisticated and large, so they can negotiate. But their leverage collapses at the moment reliability enters the conversation—because in these environments, downtime isn’t an inconvenience. It’s a headline, a missed SLA, a production loss, or a cascading failure across an entire network.

That’s why buyers demand proven reliability of 99.5% or higher. And it’s also why switching costs are so punishing. Once an automation backbone is installed, “changing vendors” can mean shutting down a fulfillment center or disrupting a semiconductor fab. Even blue-chip customers like TSMC, Intel, Toyota, and Amazon have limited alternatives when they need someone who can deliver, integrate, and keep the system running.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

The most obvious substitute is labor. But in many markets, labor is becoming the weak link—too expensive, too scarce, too volatile. Material handling systems have increasingly been viewed as social infrastructure, a response to structural labor shortages and the productivity ceilings of manual operations.

Robotics startups—especially in AMRs—can substitute for pieces of the workflow in specific niches. But the hard part isn’t a single robot doing a single job. It’s orchestrating an entire facility: the mechanical layer, the controls, the software, the exception handling, and the service support. That integrated capability is where substitutes tend to fall short.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-HIGH

This is still a competitive market. In 2024, KION Group, Daifuku, and Symbotic together accounted for about 22% of global revenue, which suggests a field that’s moderately consolidated at the top, with plenty of competition underneath.

In warehouse automation, Daifuku competes with major players like Dematic (KION Group), Swisslog, and Honeywell. New entrants keep pushing robotics and AI-forward approaches—but the bar is high. Customers want software innovation and proven hardware reliability in the same package, delivered at scale. That combination generally favors established integrators with deep reference bases.

And increasingly, rivalry shows up in software and AI: how well a system can optimize flows, predict failures, and adapt in real time. On that dimension, Daifuku’s strength in integration and whole-system optimization is a meaningful advantage—not just in selling the initial system, but in keeping it indispensable over its entire life.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's Seven Powers

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers offers another lens on what makes Daifuku so hard to dislodge. If Porter explains the shape of the playing field, Helmer helps explain why Daifuku keeps winning on it.

Scale Economies: STRONG

Daifuku’s scale shows up in the unglamorous places that decide who makes money in heavy industrial systems: procurement leverage, the ability to spread R&D across a large revenue base, and dense service coverage that lowers the cost of supporting customers in more geographies. Scale also funds the next turn of the flywheel—more investment in new capabilities, more reference projects, and a broader footprint to deliver and maintain complex systems.

Network Effects: LIMITED

This isn’t a software platform where each new user directly makes the product better for every other user. But there is a quieter ecosystem effect: every new installation expands the installed base that drives services, upgrades, spare parts, and future expansions. Just as importantly, those installations create credibility. In this category, references travel fast, and proven performance becomes a kind of compounding asset.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Daifuku sits in an uncomfortable middle that’s actually a defensive position. Its integrated hardware-software-service model is hard for a pure equipment vendor to match because integration and controls are the hard part. And it’s hard for a software-first startup to match because manufacturing, installation, and on-site support are the hard part. Being strong across the whole stack creates protection from both sides.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the core of the moat. Daifuku has systems that have operated reliably for decades. Replacing an automated warehouse backbone, a cleanroom AMHS, or an airport baggage handling system is not like swapping a supplier. It can mean pausing operations, retraining staff, revalidating performance, and taking on integration risk that no operator wants to explain to their board.

In many cases, the switching cost isn’t just high—it’s prohibitive. For mission-critical infrastructure, the risk and disruption of change can outweigh even the original price tag of the system.

Branding: MODERATE

Daifuku isn’t a household name, but within material handling it carries real weight. Holding the top global ranking for nine consecutive years reinforces that reputation. Still, this is a B2B market where “brand” is mostly shorthand for something more specific: track record, uptime, and the confidence that the system will work under pressure.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Daifuku’s most valuable resource isn’t a mine or a patent. It’s accumulated engineering knowledge—earned through decades of designing, installing, and maintaining systems that have to perform in the real world.

That expertise runs deep in automated storage and retrieval. Daifuku built its first AS/RS in 1966 and, over time, became the market leader with tens of thousands of stacker crane installations. Over more than half a century, the same customer needs have kept showing up—reducing footprint, improving storage density, saving labor, improving pick accuracy, and increasing throughput—and Daifuku has built institutional muscle around delivering those outcomes.

Process Power: STRONG

Daifuku’s “product” is the process: consult, design, manufacture, install, integrate the controls and software, and then support the system for years. Done well, that end-to-end model becomes its own advantage because it’s difficult to copy and even harder to execute consistently.

Competitors can build components. Daifuku has spent decades refining the full lifecycle machine—how to deliver complex projects, keep them running, and then expand, retrofit, and optimize them over time. That operational discipline is process power, and it’s a big reason Daifuku keeps turning one project into a relationship that lasts.

XII. Bull Case: The Infrastructure of Everything

The bull case for Daifuku is that it sits underneath a set of long-running, non-fad shifts in the real economy. Not “a hot new robotics trend,” but the slow, structural forces that keep pushing companies to automate—and then keep them paying for that automation for years.

Labor scarcity is accelerating automation adoption. In warehouses and factories across developed markets, labor is harder to hire, harder to retain, and more expensive every year. Japan’s demographic decline is the extreme case, but the pattern shows up elsewhere too: tight labor markets in the U.S. and Europe keep raising the value of reliable automation. In that environment, Daifuku benefits from being the proven partner when operators decide they can’t scale with people alone.

E-commerce penetration still has room to grow. Even after years of rapid adoption, e-commerce is still only about 15–20% of retail sales in most developed markets. As that share rises, the physical infrastructure has to expand with it: more fulfillment centers, more sortation, more automation to hit delivery speed targets without exploding labor costs. And it’s not just Amazon. Every major retailer is trying to build Amazon-like capabilities, which means more demand for the kind of end-to-end systems Daifuku delivers.

Semiconductor capacity expansion is structural. The semiconductor buildout isn’t just a cycle; it’s policy and strategy. The CHIPS Act in the U.S., subsidy programs in Europe and Japan, and continued investment in Taiwan and Korea all point toward sustained fab construction. And every new fab needs an AMHS that can move wafers reliably in ultra-clean conditions—exactly Daifuku’s specialty. As leading foundries like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel expand capacity, that front-end AMHS demand tends to follow.

Airport modernization cycles are predictable and large. Airports don’t rebuild baggage systems every year. They do it in big, multi-year programs—often tied to terminal renovations, new construction, and capacity upgrades. In North America, a lot of infrastructure is aging at the same time passenger volumes keep rising, which translates into sustained baggage handling investment. Daifuku is positioned as one of the beneficiaries of that long replacement and upgrade cycle.

Service revenue provides earnings stability. The best version of this business isn’t “sell a system and walk away.” It’s install the system, then earn for years through multi-year service contracts, software, parts, and upgrades. As Daifuku’s installed base grows, that aftermarket revenue can compound—adding predictability to what would otherwise be a more lumpy, project-driven model.

Regional manufacturing reduces risk. Daifuku has also been pushing capacity closer to the customer, especially in the United States. That matters because it reduces supply-chain complexity and helps insulate the business from tariff risk. For the U.S. market, most intralogistics, automotive, and airport systems are produced domestically—supporting both delivery reliability and margin control.

XIII. Bear Case: Cyclicality and Competition

The bear case for Daifuku is that, for all its moats and mission-critical positioning, it still lives in the real world of capital budgets, competitive disruption, and macro shocks. This is what can go wrong.

Capital expenditure cyclicality is unavoidable. Daifuku ultimately sells systems that customers buy when they’re expanding. When those customers pause, Daifuku feels it. E-commerce fulfillment center construction slowed materially in 2022–2023 as retailers worked through post-pandemic overcapacity. Semiconductor capex is even more famously lumpy. When either of those engines cools, order intake can drop quickly.

Competition is intensifying. Warehouse automation is attracting serious innovation and serious capital. Newer competitors are pushing robotics- and AI-driven approaches, and companies like Symbotic and Amazon Robotics are investing heavily in next-generation systems. Daifuku’s advantage today is integration and execution at scale—but if the industry’s center of gravity shifts toward architectures where a different stack wins, the edge can narrow.

Currency exposure creates volatility. Daifuku reports in yen but earns a substantial portion of revenue overseas. That means exchange rates can move the story around even when operations are steady. Yen appreciation, in particular, can reduce reported revenue and squeeze margins from international business.

China risk is meaningful. Daifuku has meaningful exposure to Chinese semiconductor and display manufacturing. Geopolitical tension, export controls, and a weaker Chinese economy can all translate into delayed fab investment—or projects that simply never happen—hitting one of Daifuku’s most specialized segments.

Margin pressure from commoditization. Not every part of material handling stays bespoke forever. As certain systems become more standardized, pricing pressure rises and margin can compress. You can see the intensity of that fight in how competitors respond: Germany’s KION Group, for example, has been trimming fixed costs by about EUR 160 million annually as it battles margin erosion and increasing price pressure from Asian entrants.

Valuation assumes growth persistence. Daifuku’s stock trades at a premium to many industrial peers, reflecting an expectation that these structural tailwinds—automation, e-commerce, chips—keep delivering. If growth slows, or if competition forces margins down, investors can get hit twice: weaker earnings and multiple compression on top of it.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators: What Matters Most

If you’re following Daifuku as a business—not just a story—there are a few numbers that matter more than almost everything else. They tell you what demand looks like before it shows up in revenue, whether the company is successfully turning projects into recurring relationships, and where profitability is really coming from.

1. Order Intake and Book-to-Bill Ratio

This is the clearest leading indicator of Daifuku’s health. In this world, revenue is often the echo of decisions customers made months ago. Large automation projects usually take time to design, build, install, and commission, so orders tend to become revenue roughly 6 to 18 months later.

That’s why investors watch book-to-bill so closely—orders divided by revenue. Above 1.0 means backlog is building and demand is outpacing shipments. Below 1.0 means the company is living off existing backlog. In the most recent results referenced here, Daifuku reported order intake of ¥594.7 billion, up 5.8%, a sign that demand remained healthy.

2. Service Revenue as Percentage of Total Revenue

Daifuku’s long-term quality as a business shows up in how much of its revenue comes after the initial installation. A higher service mix generally means deeper customer lock-in, steadier earnings, and better resilience when new project cycles slow down.

Services and aftermarket have been becoming a larger share of the business. And while peer benchmarks often land in the 25–40% range from services, the key is the direction over time: is Daifuku steadily shifting more of its revenue base toward maintenance, parts, software modules, and upgrades?

3. Operating Margin by Segment

Daifuku isn’t one business with one margin profile. It’s four, and they behave differently: Intralogistics, Cleanroom, Automotive, and Airport. Looking at segment operating margins helps you see what consolidated results can hide—mix shifts, competitive pressure in one area, or outsized profitability in another.

Cleanroom tends to be the standout because the technical requirements are extreme and switching costs are enormous. Watching those segment margins over time helps answer the real question: is Daifuku’s moat strengthening where it matters most, or are competitive dynamics starting to bite?

One consolidated milestone to keep in view: net income margin reaching the 10% range for the first time. It’s a meaningful step—especially for a project-heavy industrial business—but the important question is whether it holds through the next downcycle.

XV. The Investment Thesis: Building the World's Supply Chain

Daifuku sits in a rare sweet spot of the global economy: it’s the company behind the motion that makes modern commerce feel effortless. Its systems help keep iPhone components moving through TSMC’s fabs, parcels flowing through Amazon-scale fulfillment centers, and luggage finding the right carousel in airports around the world.

That’s what makes the investment case so compelling. Daifuku isn’t betting on a single product cycle. It’s positioned underneath a set of long-running tailwinds: labor scarcity that keeps pushing warehouses and factories toward automation; e-commerce growth that demands faster, denser fulfillment infrastructure; semiconductor expansion that requires cleanroom-grade AMHS; and aging airport infrastructure that has to be modernized to handle rising passenger volumes.

Daifuku, founded in 1937 and headquartered in Osaka, is the world’s largest provider of material handling systems. It designs, manufactures, and integrates automation that moves, stores, and controls physical goods across industries. The company spans cleanroom systems for semiconductors and electronics, distribution center and warehouse automation, airport baggage handling, and automotive production lines. And crucially, Daifuku doesn’t just ship equipment—automated storage and retrieval systems, conveyors, sorting systems, automated guided vehicles—it layers in the software, maintenance, and lifecycle support that turn machines into end-to-end systems customers can actually run.

The moat isn’t one secret invention. It’s the hard-to-copy accumulation of engineering know-how, customer trust, and switching costs that are almost baked into the job. When downtime can ripple through a supply chain, and when systems are expected to run reliably for decades, buyers stop optimizing for the lowest bid. They optimize for the vendor they believe will deliver, integrate, and keep it running.

The risks are real. Customer capex is cyclical. Competition is rising, especially from robotics- and software-driven entrants. Currency swings can distort results. And geopolitical uncertainty—particularly around China—can hit demand in sensitive segments like semiconductors. But if you’re willing to ride those cycles, Daifuku offers something few companies do: exposure to the physical infrastructure of the digital economy, the machines that move atoms while software moves bits.

Since 1937, Daifuku has kept pushing the craft forward—developing new products, expanding into new environments, and taking on the unglamorous challenges that make global industry run a little smoother.

From a small Osaka machinery shop making forging equipment for ironworks to the invisible backbone of global logistics, that’s the Daifuku story: patient capability-building, smart opportunism, and the compounding value of doing difficult, mission-critical work well for a very long time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music