Ebara Corporation: From Japan's First Pump to Powering the Global Semiconductor Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

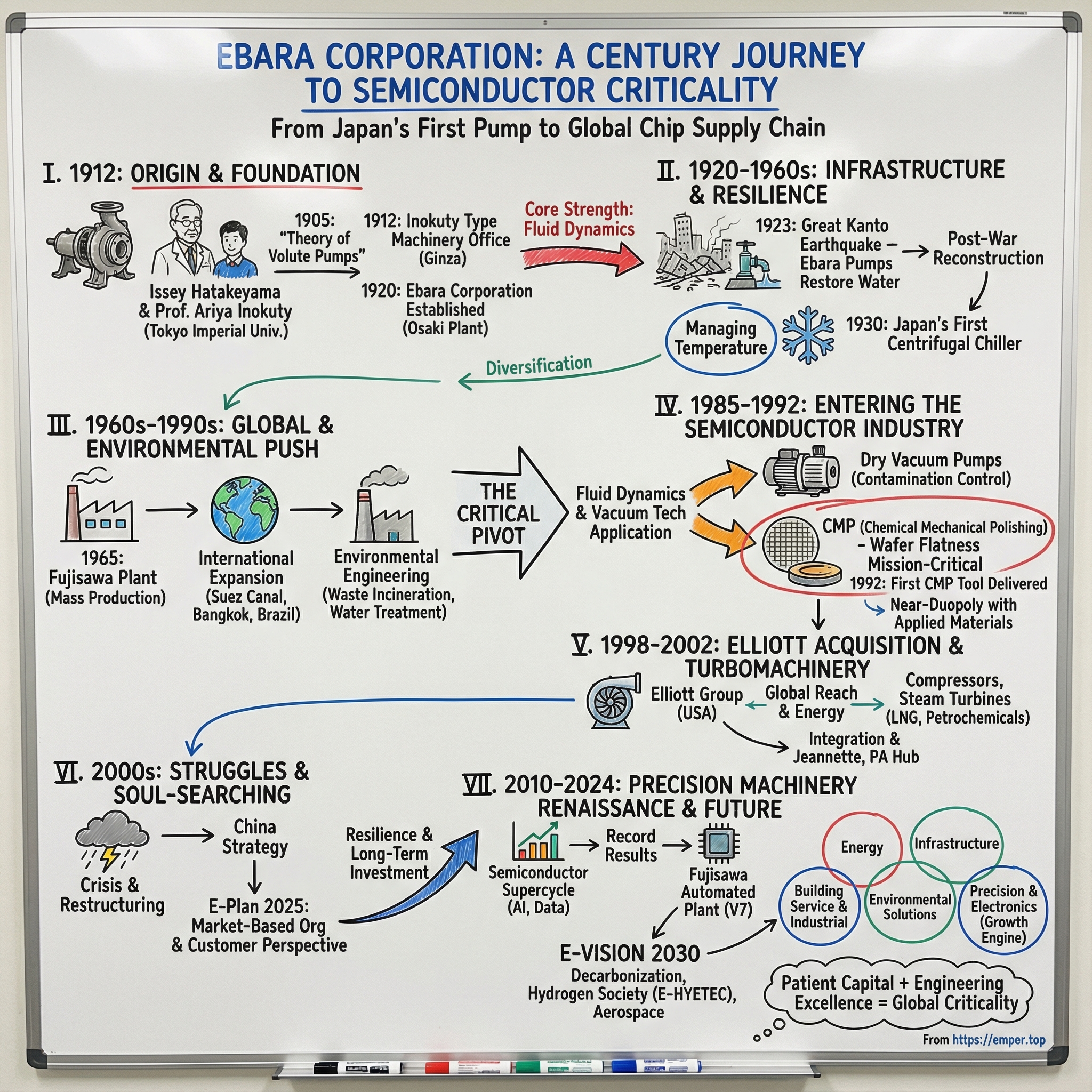

Picture a 113-year-old company most investors have never heard of. Now picture that, without it, your smartphone, laptop, and basically every modern electronic device gets a lot harder to make. That’s Ebara Corporation: a Tokyo-based industrial manufacturer that spends most of its life out of the spotlight, yet sits on a surprisingly important pressure point in the global semiconductor supply chain.

Ebara began in November 1912, founded by Issey Hatakeyama as a pump maker, and was formally established as a corporation in May 1920. Over the century that followed, it grew from a domestic machinery shop into a global enterprise: 111 group companies across Asia, Europe, the Americas, and beyond, with about 20,510 employees on a consolidated basis as of December 31, 2024.

The question at the heart of this story is the kind that only makes sense after you’ve seen it happen: how did a company built on moving water become the world’s second-largest producer of Chemical Mechanical Polishing systems, or CMP? CMP is one of those unglamorous steps that turns out to be mission-critical. It’s how you get semiconductor wafers flat enough, layer after layer, for today’s advanced chips. Ebara’s CMP tools are installed at fabs around the world, quietly enabling the devices we use every day.

That bet has been paying off financially, too. In fiscal year 2024, Ebara reported revenue of ¥866,668 million, up 14.1%, and profit attributable to owners of the parent of ¥71,401 million, up 18.4%. The company notched record results for four consecutive fiscal years—less a sudden breakthrough than the compounding payoff from choices made decades earlier.

Zoom in on CMP and the industry structure gets even more striking. Applied Materials holds roughly 42% of the global CMP market, while Ebara sits at about 27%. Together, they form a near-duopoly in a process that’s essential to manufacturing leading-edge chips. The difference is that Applied is a household name in semiconductor circles—and Ebara, outside Japan, often isn’t.

Our arc runs from a university laboratory in early-20th-century Japan to the cleanrooms of the world’s most advanced semiconductor fabs. Along the way, we’ll see how a deep foundation in fluid dynamics—pumping, pressure control, moving gases and liquids—expanded into vacuum technology, and then into precision machinery capable of polishing wafers to extreme flatness. And we’ll keep coming back to a very Japanese advantage: patient capital, where the timeline is measured in decades, not quarters.

By the end, the themes snap into focus: university research turned into industry, core competencies stretched into unexpected markets, and a traditional industrial company positioning itself—almost invisibly—at the center of the digital age.

II. The Origin Story: A Professor, A Student, and Japan's First Centrifugal Pump (1905–1920)

In the early 1900s, Japan was industrializing fast—but it was still buying too much of the machinery that made modern life possible. Pumps were a perfect example: the unglamorous workhorses that moved water through cities, mines, and factories. Most of the best ones were imported. If Japan wanted to build infrastructure on its own terms, it needed to build the machinery, too.

That’s where Ebara’s origin story begins: not in a factory, but in a university.

Issey Hatakeyama, Ebara’s founder, was born in 1881 in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. He came from a wealthy family with deep roots in Japan’s samurai class—his lineage traced back through generations of the Hatakeyama family of Noto Province. That background mattered, not because it guaranteed success, but because it shaped his temperament: duty, persistence, and an instinct to think in long horizons.

Hatakeyama studied engineering at Tokyo Imperial University (today the University of Tokyo), where he came under the influence of Professor Ariya Inokuty. Inokuty wasn’t just another academic. In 1905, he published “The Theory of Volute Pumps,” a systematic explanation of centrifugal pump mechanics that earned international recognition as a standard reference for the field. In other words, Hatakeyama wasn’t learning from a tinkerer—he was learning from one of the world’s authorities on how pumps actually work.

Then came the moment that reads like a startup founding scene a century before Silicon Valley made those stories famous.

After Hatakeyama’s employer, Kunitomo Seisakusho, collapsed, he gathered several colleagues and—on the night of the bankruptcy—went to see Inokuty. He asked for permission to continue the pump work they’d been doing. Inokuty agreed to fully support him. But there was a constraint that would define the early company: Hatakeyama didn’t have the capital to run a plant. So they improvised. Hatakeyama would handle design and sales. Manufacturing would be outsourced.

He moved immediately. He rented the second floor of an industrial magazine company in Ginza and opened the Inokuty Type Machinery Office—the predecessor of EBARA—with Inokuty as Senior Manager and Hatakeyama as Manager. Hatakeyama was 30.

The titles mattered. Inokuty, as a university professor, couldn’t become the representative of a commercial enterprise, so he stayed in an advisory role. The structure was clean and modern: the professor contributed credibility and intellectual foundation; the former student ran the business. It’s the university spin-out model—decades before the phrase existed.

From the beginning, Hatakeyama pushed a simple philosophy that became Ebara’s cultural cornerstone: “Netsu to Makoto,” or “Passion and Dedication.” He wasn’t preaching corporate slogans. He was setting an operating system: bring energy, act sincerely, and focus the company’s engineering talent on meeting society’s needs.

The early business was “asset-light” only because it had to be. With no factory and limited funds, the team survived by selling expertise. They designed pumps, took orders, and relied on outside production. That forced a particular kind of discipline: if you can’t win on scale, you have to win on quality and know-how. Ebara’s later reputation for reliability didn’t appear out of nowhere—it was forged here, when their only defensible advantage was getting the engineering right.

By 1914, the office had grown enough to establish its first self-funded plant in Nippori, Tokyo. Two years later came a breakthrough order: Japan’s largest centrifugal pumps at the time, built for Tokyo’s Asakusa Tamachi pumping station. These were serious machines—massive impellers, massive weight—and they served a serious purpose: supplying water to a rapidly expanding city. It wasn’t just a contract. It was proof that domestically designed, domestically produced equipment could perform at the highest level.

In 1920, the company took the next step into permanence. It was formally incorporated and opened the Osaki Plant in Minami-Shinagawa, Tokyo—Japan’s first facility dedicated exclusively to pump manufacturing. The move marked the transition from a clever engineering office to a true industrial manufacturer, with the ability to scale production and refine its technology over time.

And even the name signaled that permanence. The company became “Ebara,” after the Ebara-gun district where the new factory stood—tying its identity to a place, and to the idea that it was building something meant to last.

Seen from today, the lesson is straightforward: Ebara was born from the pairing of world-class theory and gritty execution. Inokuty gave the company scientific legitimacy. Hatakeyama turned that into products, plants, and customers. The foundation that later supported everything—from infrastructure pumps to semiconductor tools—was laid right here, when “technology transfer” meant a professor, a student, and the decision to bet on Japanese-made machinery.

III. Building Japan's Infrastructure: From the Great Kanto Earthquake to Post-War Reconstruction (1920–1960s)

Ebara had barely finished becoming a “real” manufacturer when Japan put it to the test.

On September 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake ripped through Tokyo and Yokohama and shattered the systems a modern city depends on. The destruction was immense: more than 140,000 people were killed, around 1.5 million were left homeless, and critical infrastructure—especially water—collapsed at the exact moment it was needed most.

For a pump company, this is the definition of a make-or-break moment. Ebara’s equipment went straight into action, and within a day the aqueduct was functioning again. That single detail tells you almost everything about what the company was becoming. In a crisis, reliability isn’t a marketing line. It’s whether a city can get water to fight fires and keep people alive.

The earthquake didn’t just validate Ebara’s engineering. It made the company visible. By the end of the 1920s, Ebara had pushed into the front ranks of Japan’s domestic machinery market, earning trust the hard way: by performing when failure wasn’t an option.

Then Ebara did something that, in hindsight, looks like the start of a lifelong pattern. In 1930, it built Japan’s first centrifugal chiller—moving from “moving water” into “managing temperature,” and proving that its fluency in fluid dynamics could travel. Pumps were the beginning, not the boundary.

As the company grew, it anchored itself physically, too. A new factory opened in Haneda, Tokyo, and by 1938 that facility had become Ebara’s headquarters—plant and nerve center in one—rooted in Tokyo’s industrial heartland.

World War II nearly wiped that out. Bombing raids largely destroyed the company’s main facility, and survival came down to what it could keep running elsewhere. The Kawasaki plant became the lifeboat. In 1945, Ebara shifted all manufacturing there—and within a week of Japan’s surrender, it had restarted pump production. That pace wasn’t just impressive. It was existential. It meant customers could count on Ebara even as the country rebuilt from rubble.

Through the late 1940s and early 1950s, Ebara became part of the reconstruction machine, supplying pumps and related equipment that supported the production of food, iron, and coal—the basic inputs of a recovering economy. Meanwhile, it rebuilt what it had lost, completing the reconstruction of the Haneda plant in 1955.

And then came a new kind of expansion: not just making equipment, but partnering to build systems. In 1956, Ebara formed EBARA-Infilco Co., Ltd., a 50–50 joint venture with U.S.-based Infilco Inc. to advance water treatment technologies. It was a major step beyond pumps into filtration and purification—Ebara moving up the stack from components to full solutions, and doing it through international collaboration.

By the 1960s, the template was set. Ebara’s identity wasn’t only “we make machinery.” It was “we make machinery you can’t afford to have fail.” Water supply, sewage treatment, industrial cooling—these aren’t discretionary purchases, and they don’t politely pause during downturns. The engineering culture that emerged from earthquakes, war, and reconstruction was built around one idea: when infrastructure breaks, you either restore it fast—or you become the reason it stays broken.

IV. Diversification & Global Expansion: From Pumps to Environmental Engineering (1960s–1990s)

By the 1960s, Ebara had earned its reputation the hard way: build equipment that works, and keep it working when life depends on it. Now Japan’s economy was exploding, cities were expanding, factories were multiplying—and Ebara faced the obvious question. Was it going to stay a pump company, or become something bigger?

The answer started on the factory floor. In 1965, Ebara built the Fujisawa Plant, which established Japan’s first mass-production system for standard pumps. A year later, it began producing refrigeration equipment there as well. Over time, Fujisawa grew into a plant that could turn out a wide range of products—eventually including semiconductor-related equipment that would become indispensable to modern life.

This wasn’t just more capacity. It was a shift in the company’s operating model. Mass production of standard pumps meant lower unit costs without sacrificing quality, which gave Ebara room to compete more broadly—and, crucially, to fund the next layers of engineering sophistication.

Then came the international push. Ebara had already begun taking steps beyond Japan’s borders earlier in the decade: in 1961, it became a key supplier of dredging pumps for the Suez Canal, and in 1964 it established its first foreign sales subsidiary in Bangkok, Thailand. The playbook was cautious but effective: build demand and relationships through sales first, then commit capital to production.

In 1975, that approach graduated into Ebara’s first post-war overseas production facility: Ebara Indústrias Mecánicas e Comércio Ltda. in Brazil (the precursor of EBARA BOMBAS AMÉRICA DO SUL LTDA.). Choosing Brazil—then in a period of rapid growth—signaled something important. Ebara wasn’t just exporting products; it was willing to manufacture where the growth was.

At the same time, Japan’s rapid industrialization brought a darker companion: pollution. The 1960s and 1970s created urgent demand for environmental technology—cleaner air, cleaner water, better waste management—and Ebara’s skill set translated naturally. If you understand fluids, pressure, flow, and systems engineering, you can move beyond “pumping” into “treating.”

One concrete example came out of the group’s research efforts in the 1970s: a flue gas emissions processing system, developed in response to calls for desulfurization of factory emissions. In 1984, Ebara consolidated research operations into a single unit under Ebara Research Co., tightening the loop between R&D and productization. Waste incineration technology, water treatment systems, gas processing equipment—these weren’t side projects. They addressed real social problems and opened up durable new lines of business.

Europe was next. In 1989, Ebara established Ebara Italia S.p.A. (now Ebara Pumps Europe S.p.A.) in Italy as a European production base for standard pumps. Local production meant shorter lead times, better service, and a more credible footing in competitive European markets.

All of this diversification could have turned into a loose collection of businesses. Instead, Ebara pulled it into a more coherent structure in 1994. The company merged with its joint venture partner Ebara-Infilco Co., Ltd., bringing water treatment and environmental engineering fully in-house. The result was a clear three-business structure: Fluid Machinery and Systems, Environmental Engineering, and Precision Machinery.

By the early 1990s, Ebara was no longer defined by pumps alone. It served water utilities, industrial plants, and municipal waste systems—and it was starting to build a foothold in the emerging semiconductor industry. Different end markets, same underlying strengths: fluid dynamics, thermal engineering, and precision manufacturing.

For investors, that created both stability and confusion. Multiple revenue streams helped smooth cycles, but they also made Ebara harder to categorize—and easier to underestimate. The semiconductor exposure that would later become pivotal was still small, and at the time, easy to miss.

V. The Critical Pivot: Entering the Semiconductor Industry (1985–1992)

The decision that would eventually turn Ebara from a respected industrial manufacturer into a key supplier to the chip industry didn’t arrive with fanfare. It arrived the way most enduring industrial pivots do: as a quiet, engineering-led extension of what the company already knew how to do.

By the mid-1980s, Japan sat at the center of global semiconductor manufacturing, especially in memory. And Ebara could see what that meant. Chip fabs weren’t just buying “machines.” They were buying control: of particles, of chemistry, of pressure, of flow—at scales where a tiny mistake could wipe out an entire batch of wafers. That was a world where Ebara’s heritage in fluid dynamics and pumping wasn’t a relic. It was a bridge.

A major step in building that bridge came in the U.S. In 1991, Ebara established Ebara Technologies Incorporated as its North American base for the precision machinery business. ETI had been founded in 1990 and, before that, operated as the vacuum division inside Ebara International Corporation. The structure mattered. Ebara wasn’t dabbling from afar; it was placing people, service, and development closer to the customers driving the frontier.

The technical logic connecting pumps to semiconductors becomes obvious once you see the fab as a controlled environment. Many chipmaking steps depend on ultra-clean vacuum chambers. Any contamination—down to the molecular level—can ruin yield. Maintaining those vacuum conditions requires equipment that can evacuate chambers reliably while handling harsh process gases. That’s where dry vacuum pumps come in: non-contact pumps that don’t use oil or liquid for sealing, which helps prevent backflow and contamination. They’re also simpler to operate day-to-day, since they avoid routine tasks like refilling or replacing sealing fluids. In manufacturing environments obsessed with cleanliness—semiconductors, flat panel displays, LEDs, even solar—dry pumps aren’t a nice-to-have. They’re foundational.

Ebara’s move into dry vacuum pumps was less a leap than a translation. The company took decades of pump engineering and applied it to gases instead of liquids, adapting designs and materials to match semiconductor requirements. Over time, that effort scaled dramatically: Ebara has shipped more than 200,000 dry vacuum pump units worldwide. And it built the support muscle to match, with more than 50 service locations globally—because in a fab, uptime is a product feature.

Then came the bigger bet: CMP, or Chemical Mechanical Polishing.

CMP is the step that makes modern chips possible by making wafers flat—really flat—so that each new layer can be built on top of the last without compounding defects. As chips added more layers and tighter geometries, planarization went from “important” to “non-negotiable.” Ebara began developing CMP systems specifically to support the miniaturization and multilayering of semiconductors. In 1992, it delivered its first CMP tool. In hindsight, that delivery reads like a starting gun for what would become Ebara’s most strategically valuable business.

In CMP, Ebara became known for “dry-in/dry-out” technology. The idea addressed a very practical fab problem: earlier CMP flows handled wafers wet as they entered and exited the system, which added contamination risk and operational complexity. Dry handling throughout simplified the flow and improved performance in the ways fabs care about most—yield, throughput, and repeatability.

Ebara’s CMP lineup would go on to include platforms like the F-REX series, designed for tight planarity control across a range of processes and materials. The details evolve with each generation of chips, but the takeaway stays constant: CMP isn’t a commodity tool, and a supplier that earns trust at the cutting edge can hold that position for a long time.

The timing helped. Japan’s semiconductor dominance in the late 1980s created a strong home market that valued domestically produced, high-reliability equipment. From there, as global capacity expanded, Ebara’s vacuum and CMP businesses grew alongside it.

What makes this pivot so consequential is what happened to the market structure. At the advanced end of CMP—the equipment used in leading-edge, high-volume production—supply concentrated into essentially two companies: Applied Materials in the U.S. and Ebara in Japan. It’s one of the most lopsided bottlenecks in semiconductor equipment. Not because regulators mandated it, but because the barriers are brutal: years of customer qualification, deep process know-how that only accumulates through iteration, and the reality that a failure inside a billion-dollar fab is unacceptable.

For investors, it’s the cleanest example of Ebara’s long-game mentality. The company spent years building vacuum and CMP capability before it mattered at global scale. The payoff didn’t show up on a quarterly chart. It showed up decades later—when semiconductor demand surged and Ebara was already installed, already qualified, and sitting in the middle of a process step the industry couldn’t skip.

VI. The Elliott Acquisition: Becoming a Global Turbomachinery Player (1998–2002)

Even as Ebara’s semiconductor bet was taking shape, the company made a very different move—one that reshaped its energy and industrial equipment capabilities and gave it a truly global manufacturing footprint.

The centerpiece was Elliott, an American turbomachinery specialist with deep roots. Elliott’s modern corporate lineage ran through Carrier Corporation, where it operated as a division from 1957 to 1981. When United Technologies Corporation acquired Carrier in 1981, Elliott Turbomachinery, Inc. was formed. But the brand itself went back further: founded in 1901 as the Liberty Manufacturing Company to make boiler-cleaning equipment based on the patents of William Swan Elliott, it incorporated as the Elliott Company in 1910. By the time Ebara came into the picture, Elliott was a proven name in compressors and turbines, headquartered in Jeannette, Pennsylvania.

Ebara didn’t meet Elliott as a stranger. Their relationship dated back to 1968, when Ebara licensed Elliott technology to build Elliott turbines in Japan. Over the following decades, that licensing arrangement became more than a contract—it became familiarity. Ebara learned Elliott’s designs, how the equipment behaved in the field, and what Elliott’s customers expected. It even manufactured Elliott designs at its Sodegaura plant in Japan. So when the opportunity came to go deeper, Ebara wasn’t buying an unknown asset. It was formalizing a partnership it had effectively been living inside for years.

That opportunity arrived via a leveraged buyout. Elliott’s management team, led by President Paul Smiy, arranged the LBO of Elliott Turbomachinery Company from UTC, backed by investors that included Ebara. From there, Ebara steadily increased its stake, and by 2000 Elliott became a wholly owned subsidiary of Ebara Corporation.

What Ebara got was a turbomachinery platform with global reach. Elliott designs, manufactures, installs, and services rotating equipment: compressors, steam turbines, power recovery expanders, control systems, and steam turbine generator sets. It also supplies the supporting infrastructure—lubrication, seal, and piping systems, protective coatings, spare parts—and the services that keep critical equipment running, from repairs and field service to training and engineered support. The customer list reflects where turbomachinery matters most: petrochemical plants, refineries, oil and gas producers, LNG facilities, ethylene plants, and power generation.

That positioning paid off as LNG demand surged in the early and mid-2000s. As massive liquefaction projects ramped up in places like the Middle East and Russia, demand for Elliott compressors rose with them. The LNG boom turned Elliott’s equipment into a repeat player on the world’s biggest gas projects—the kind where a single train going down can cost a fortune and reliability is the whole game.

Over time, Ebara integrated its Japan-based turbomachinery activities with Elliott under the Elliott Group banner. And the integration didn’t stop with compressors and turbines. Elliott Group ultimately merged Ebara’s cryogenic pumps and expanders business—based in Sparks, Nevada—into its operations in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, where those products are now manufactured.

That integration accelerated later. In October 2017, Elliott Group began integrating the operations of Ebara International Corporation into Elliott. As CEO Michael Lordi put it: “The merger of Ebara International Corporation with Elliott is a good fit. Elliott has been working closely with them for the past year and a half to ensure continuity of expertise, service, and quality for existing and new customers and business partners.” Cryodynamics pumps and expanders moved under the Jeannette roof, and the site’s importance only grew.

Elliott also invested in expanding what it could do there, completing construction of a $60 million cryogenic pumps testing facility near its headquarters. Built on a 13-acre campus with an indoor enclosed test loop, the facility gave Elliott the ability to test a full range of cryogenic pumps and expanders—including large units—year round.

In practical terms, the Elliott acquisition changed Ebara’s map. Jeannette became a major global manufacturing hub, and Ebara broadened its exposure to oil and gas, petrochemicals, and power generation customers worldwide. It also showed a distinct Ebara pattern: disciplined M&A driven by deep prior knowledge, followed by gradual integration over years—not quarters—aimed at preserving what works while steadily compounding the benefits.

VII. The Early 2000s Crisis: Struggles and Soul-Searching

Just as Ebara was stretching itself—into semiconductors on one side and global turbomachinery on the other—the early 2000s delivered the kind of stress test that exposes every weak seam in an industrial company.

From roughly 2000 to 2005, Ebara hit a rough patch in both performance and public trust. Inside the company, the mood turned anxious. Employees openly wondered, “What will happen to the Company?” For an organization built on reliability, that question wasn’t just emotional. It was existential.

The problems came from multiple directions at once. The environmental business, built around large, project-based work, was vulnerable to lumpy timing and delayed decisions. Precision machinery—still early in its semiconductor journey—wasn’t yet operating at the scale of the biggest equipment makers. The Elliott integration expanded Ebara’s global reach, but it also consumed management attention at exactly the wrong time. And in the background, Japan’s broader economic stagnation offered little help on the home front.

Ebara’s answer was restructuring—more than once. In 1996, it reorganized into a management division and four production divisions, including Wind & Hydraulic Power, Environmental Engineering, Precision Electronics, and Information Communications. Then in 2005, it regrouped again into four core divisions: Fluid Machinery & Systems, Environmental Engineering, Precision Machinery, and New and Renewable Energy. The theme wasn’t reinvention for its own sake. It was an attempt to restore clarity—about accountability, priorities, and where capital should go.

At the same time, Ebara looked for growth where growth was unmistakable: China.

In 2003, Ebara announced that its Chinese subsidiary would begin producing waste incinerators capable of generating electricity. It then accelerated manufacturing investments. In 2005, Ebara established Ebara Boshan Pumps Co., Ltd., focused on production and sales of large-scale, high-pressure pumps in China. In 2006, it established Ebara Machinery (China) Co., Ltd., as a base for production and sales of standard pumps.

The China strategy was both opportunity and necessity. China’s infrastructure boom created huge demand for pumps, environmental equipment, and industrial machinery. Building locally lowered costs and put Ebara closer to customers. But it also raised the execution bar: new operating complexity, new competitors, and a market that played by different rules.

Those difficult years forced hard learning. Ebara sharpened its view of which businesses deserved continued investment and which needed tighter discipline. It got better at living with cyclicality in project-driven segments. And most importantly, it kept funding precision machinery even when the near-term results didn’t justify it on paper.

That long view shows up in how Ebara itself explains today’s success. By the end of the last fiscal year, the company had completed the second year of E-Plan 2025, its medium-term management plan toward E-Vision 2030, and it had posted record results for four consecutive fiscal years. Ebara credits part of that performance to E-Plan 2025 initiatives like shifting to a target market-based organization and emphasizing the customer’s perspective. But the more revealing point is what it says next: over a longer horizon, those results reflect the steady work of each business and functional organization over the past 10 to 15 years.

That’s Ebara in a sentence. The company didn’t abandon the hard businesses when they were hardest. It kept investing, kept iterating, and kept improving execution—until the environment finally rewarded the preparation.

For investors, this era is the reminder that the most valuable capabilities often look like underperformers right before they become indispensable. Plenty of industrial companies cut the very investments that would have positioned them for the next upcycle. Ebara didn’t. And when the semiconductor supercycle arrived, it wasn’t scrambling to catch up—it was already qualified, already installed, and ready to scale.

VIII. The Precision Machinery Renaissance: Riding the Semiconductor Supercycle (2010–2024)

By the time the 2010s arrived, Ebara’s “quiet pivot” into semiconductor equipment wasn’t a side quest anymore. The digital economy’s appetite for chips kept climbing, and the investments Ebara had kept making—sometimes painfully, sometimes out of step with the mood of the moment—started to compound.

A lot of that compounding came from doing the unsexy work: capacity, footprint, and operational focus. Ebara strengthened its global network, expanded the Precision Machinery Company’s facilities, and built the Futtsu Plant as a new “mother plant,” completed in 2010. At the same time, it kept pushing its underlying fluid technologies forward—not just to sell more machines, but to develop products and services aimed at real-world needs.

Futtsu mattered because it reinforced Ebara’s traditional businesses at the high end. The plant manufactures large industrial pumps, hydraulic turbines, and fans—giant equipment, with nominal diameters exceeding 4,000 mm. In practice, that meant Ebara could modernize and scale production for legacy product lines while freeing the Fujisawa Plant to lean further into precision machinery and semiconductor equipment.

Then the CMP business started putting up the kind of milestones that signal a category leader. By January 2022, Ebara had delivered 3,000 cumulative CMP systems worldwide. And the timing wasn’t incidental. Semiconductor wiring widths were moving beyond the nanometer scale and into the Ångström era—dimensions so small you’re effectively working at the level of a few atoms. When geometry gets that tight, flatness stops being a nice-to-have. CMP becomes one of the processes that decides whether a fab’s yield is great—or a disaster.

Ebara responded the way it usually does: with manufacturing muscle. In early 2024, it expanded CMP equipment production capacity by boosting domestic output by 30%, aimed at rising global demand for 300MM CMP tools, especially from customers in South Korea and Taiwan. It also announced that 25% of its new production lines would be dedicated to slurry-efficient, low-consumption CMP systems designed for next-generation DRAM and logic chips.

The demand catalyst was the one reshaping the entire semiconductor equipment landscape: generative AI. Training and running large language models, and building the accelerators that power them, requires advanced chips produced at the leading edge—exactly the chips that put the most pressure on CMP performance. As AI demand pulled forward fab investment, Ebara’s precision machinery segment saw a surge in orders that reflected that step-change.

The customer roster tells the story, too. More than 80% of the world’s top 20 chip manufacturers were EBARA customers. When leading fabs like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel spec out new lines, Ebara’s CMP systems and dry vacuum pumps frequently make the cut—not because they’re cheap, but because they’re proven.

Under the hood, Ebara’s semiconductor portfolio is organized into two buckets. The Components Division supplies vacuum exhaust management systems—Dry and Turbomolecular Vacuum Pumps—along with point-of-use abatement systems. The System Equipment Division focuses on wafer processing equipment, centered on CMP, plus advanced electro-plating and bevel polishing equipment used in semiconductor manufacturing.

Dry vacuum pumps, unlike CMP, are a more crowded battlefield. In that market, Atlas Copco (Edwards Vacuum) held approximately 21.8% share in 2025, supported by a strong global network and a broad dry pump lineup. Ebara held about 17.4%, driven by its deep customer base in Asia and long-standing partnerships with Japan-based fabs.

But “more competitive” doesn’t mean less attractive. Vacuum pumps are a service-heavy business: they need regular maintenance and, eventually, replacement. That creates meaningful recurring revenue, and Ebara’s concentration in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan puts it right next to the world’s most important semiconductor manufacturing clusters.

Ebara doubled down on that advantage at Fujisawa. In December 2019, it opened a new automated factory there—Building V7—to produce dry vacuum pumps. The goal was straightforward: revamp production and business processes around automation to strengthen competitiveness and improve profitability. As IoT and AI spread into everything, semiconductor use expanded rapidly in industrial markets, and the demand backdrop for semiconductor manufacturing equipment strengthened with it.

V7 was a signal of intent. In a category where reliability is everything, automation isn’t just about reducing labor cost. It’s about consistency—fewer process variations, tighter quality, and more predictable output at scale.

For investors, this era is the thesis made visible. From early CMP development through the industry’s many cycles to record results by 2024, Ebara kept committing to semiconductor equipment long before it was an obvious winner. The payoff didn’t arrive in a tidy three-year window. It arrived over decades—when the market finally surged, and Ebara was already installed, already trusted, and ready to deliver.

IX. E-Vision 2030: The Modern Transformation (2020–Present)

By the 2020s, Ebara wasn’t just riding a semiconductor tailwind. It was trying to answer a broader question: what does a 100-plus-year-old industrial company become in a decade defined by decarbonization, supply-chain resiliency, and ever more advanced chips?

In 2020, Ebara laid out its answer in a long-term vision called E-Vision 2030. The idea was simple in structure and big in ambition: set a 10-year direction starting in fiscal year 2020, with goals that combine business performance and social impact.

Ebara framed the plan around five “material issues,” under a 2030 message: “Technology. Passion. Support our globe.” The priorities included using technology to support a sustainable, environmentally friendly world—ample food and water, and safe, reliable social infrastructure—while also supporting economic development that reduces poverty and enables more abundant lifestyles. On the operations side, it also emphasized reducing CO2 emissions from its own business and expanding renewable energy use on the path toward carbon neutrality.

Then Ebara did something you don’t always see from a Japanese industrial: it put a market-cap target on the table. The company set an indicator of corporate value of 1 trillion yen by 2030. It’s a clear signal that management wanted to talk about shareholder value explicitly, not just as an outcome, but as an objective alongside the company’s broader mission.

The vision also came with concrete headline goals: reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of about 100 million tons of CO2, deliver water to 600 million people, and push semiconductor capability by challenging the 14Å generation of state-of-the-art devices. In other words: environment, infrastructure, and chips—the three arenas where Ebara believes its engineering can matter most.

Turning a 10-year vision into execution requires something more tactical, so Ebara positioned E-Plan 2025 as the three-year operating plan that brings E-Vision 2030 down to earth. Under the theme of “creating value from the customer’s perspective,” the company shifted to a more face-to-face market structure, aiming to strengthen competitiveness in each business area and build on what it achieved under the prior medium-term plan, E-Plan 2022.

For growth, Ebara set a revenue CAGR target of 7% over the E-Plan 2025 period, driven mainly by two growth-area businesses, reflecting management’s confidence—especially in precision machinery and energy.

The financial framing was equally direct. For fiscal year 2025, Ebara forecast revenue of ¥900,000 million, operating income of ¥101,500 million, profit before taxes of ¥100,600 million, and profit attributable to owners of the parent of ¥72,400 million. And for the nine months ended September 30, 2025, it reported orders received of ¥680,162 million, revenue of ¥663,555 million, operating profit of ¥69,541 million, and profit attributable to owners of the parent of ¥44,683 million—all up year-on-year.

Organizationally, Ebara also tightened its structure around markets rather than products. It reorganized into five market-focused segments intended to improve customer orientation: Building Service & Industrial, Energy, Infrastructure, Environmental Solutions, and Precision & Electronics. The goal was to make the company easier to run—and easier to align—around what customers actually buy and why.

What’s most interesting about E-Vision 2030, though, is how it extends Ebara’s engineering into the next frontier without abandoning its roots. Hydrogen is a prime example. As countries moved toward 2050 carbon neutrality targets, Ebara described a role for itself in building a “hydrogen society,” using co-creation across its businesses and with external partners to develop hydrogen-related offerings spanning production, transport, and use.

To support that, Ebara announced it would establish a commercial product test and development center for hydrogen infrastructure-related equipment, E-HYETEC, in Futtsu City, Chiba Prefecture. The center is intended to test performance and develop elemental technologies using liquid hydrogen, with the goal of accelerating the social implementation of liquid hydrogen pumps. Ebara describes it as the world’s first real-scale commercial product test facility using actual liquid hydrogen pumps.

Aerospace is another extension that sounds new, but is still classic Ebara at the core: turbomachinery, precision, fluids. Using its fluid technology, Ebara has supported improvements to JAXA’s engine turbo pumps since the early 2000s, and since 2018 it has provided technical cooperation related to electric pumps.

It’s also partnered beyond the traditional industrial ecosystem. Along with Muroran Institute of Technology and Interstellar Technologies Inc. (IST), Ebara began developing a rocket turbo pump for launches of ultra-compact satellites. In August 2020, it started the CP Hydrogen Business Project, which includes aerospace technology.

Taken together, E-Vision 2030 reads less like a reinvention and more like a disciplined expansion of the same playbook that got Ebara into semiconductors in the first place: find the hardest, most valuable problems in society’s infrastructure—and apply world-class fluid dynamics, thermal engineering, and precision manufacturing to solve them.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: The Five-Company Structure

To really understand Ebara, you have to stop thinking of it as “a pump company that also does semiconductors” and start thinking of it as a portfolio of five businesses—each with its own customers, cycles, and competitive realities.

Those five segments are: Building Service & Industrial (standard pumps, blowers, refrigeration equipment, and cooling towers); Energy (custom pumps, compressors, and turbines for power generation and process industries, including the Elliott turbomachinery business); Infrastructure (specialized pumps and blowers for water, sewage, flood control, and tunnel ventilation); Environment (municipal and industrial waste treatment and related facilities); and Precision & Electronics (semiconductor manufacturing equipment).

Building Service & Industrial is the closest thing to “classic Ebara”—the dependable pumps and cooling equipment that trace all the way back to the company’s origins. It serves commercial buildings, factories, and agricultural operations. Demand tends to be steady, but growth is typically modest, and competition is often local and price-sensitive. And even here, execution matters. The segment recorded an impairment loss on goodwill related to Vansan, a Turkish company acquired through M&A, resulting in a total impairment loss of JPY7 billion. It’s a reminder that even a careful acquirer can misjudge integration, market conditions, or the path to returns.

Energy is where Ebara’s global turbomachinery ambition shows up most clearly. This includes Elliott’s compressors and turbines, alongside Ebara’s custom pumps for power generation and petrochemical applications. But it’s also a segment staring directly at the energy transition. Elliott has acknowledged that its oil and gas base is being challenged by decarbonization trends, and it’s responding with investment in technologies aligned to the new energy focus—hydrogen compression, carbon dioxide compression, and more optimized natural gas pipeline compression.

That mix of “today’s cash flows” and “tomorrow’s direction” is visible in customer wins, too. Last summer, Ebara Elliott was awarded a contract by Bechtel Energy Inc. to supply cryogenic rotating equipment for the Port Arthur LNG Phase 1 project in Jefferson County, Texas, being developed by Sempra Infrastructure. Ebara supplied cryogenic pumps, expanders, boil-off gas compressors, and end flash gas compressors—exactly the sort of high-stakes, uptime-critical equipment Elliott is known for.

Infrastructure is Ebara in its civic-utility role: the pumps and blowers behind clean water delivery, sewage treatment, flood control, and even tunnel ventilation. The tailwind is obvious—aging infrastructure and rising global investment in water systems—but the business comes with long project cycles and the hard constraint of municipal budgets. It’s vital, durable work, but not always fast-moving.

Environmental Solutions is the flip side of that: big, complex systems for waste incineration, industrial waste treatment, and water treatment. The challenge is that this segment is inherently project-based, which means results can swing with the timing of major orders. The environmental business faced a decline due to the timing of large-scale projects, and that’s the reality of a segment where wins are lumpy and schedules can shift.

Precision & Electronics is the growth engine. This is where Ebara sells the equipment that fabs rely on: CMP systems, dry vacuum pumps, gas abatement systems, and ozonized water generators. The same traits that made Ebara trusted in infrastructure—performance, reliability, and the ability to support equipment in the field—translate extremely well here. And while semiconductors are the headline, Ebara’s precision products also extend into adjacent industries like solar cells, pharmaceuticals, broader manufacturing, and research and development applications.

Put together, the segment mix is both a strength and a complication. Precision & Electronics can grow quickly and earn premium economics when the semiconductor cycle is strong. Infrastructure and Environment can provide ballast, but with slower growth and, in Environment’s case, more volatility. Energy has scale and global reach, but is navigating a world shifting away from fossil fuels. Building Service & Industrial brings steadiness, but lives in mature markets where incremental gains are hard-earned.

Ebara’s footprint reflects that multi-business reality. With more than 19,000 employees, the company has established 117 group companies across all five continents. That global presence helps it serve customers where they operate, while also creating manufacturing redundancy and local access that matter in heavy industry.

For investors, the central tension is straightforward: Ebara has meaningful semiconductor exposure, but it doesn’t look like a pure-play semiconductor equipment company. The diversified structure can obscure the value of precision machinery—but it can also cushion the downside in a way pure-plays often can’t.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Ebara’s 113-year history isn’t just an industrial timeline. It’s a playbook for how durable advantages get built—quietly, patiently, and with a bias toward engineering reality over business-fashion narratives.

The Power of University-Industry Connection: Ebara began as a direct bridge from academic insight to commercial execution. Dr. Ariya Inokuty’s globally recognized work on centrifugal pumps didn’t just inspire a product; it gave the young company a foundation that was hard for competitors to copy, because it came from first principles. The broader lesson is simple: when a company is born from real research—not just incremental tweaks—it can start life with a depth advantage that compounds for decades.

Core Competency Leverage: Ebara is a case study in how “one thing” can turn into many—if the one thing is deep enough. Its mastery of fluid dynamics and precision engineering expanded in a logical chain: moving liquids with pumps, then handling gases with compressors, then creating ultra-clean vacuum environments, and eventually building tools used inside semiconductor fabs. Along the way, it broadened into chillers, fans, compressors and turbines, waste treatment plants, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Different end markets, same underlying physics—and the same culture of manufacturing precision.

Patient Capital: The semiconductor journey didn’t pay off quickly. It took decades of steady investment before it became a major engine of results. Many companies—especially those managed to short-term metrics—would have scaled back long before CMP and vacuum equipment matured into strategic assets. Ebara’s own framing is telling: when it talks about recent record performance, it credits not a single turnaround move, but the cumulative efforts of its organizations over the last 10 to 15 years. Patient capital doesn’t just preserve projects. It preserves the option for those projects to become indispensable.

Quality Obsession: “Netsu to Makoto”—passion and dedication—wasn’t a slogan pasted onto annual reports. It became a quality culture, and in Ebara’s markets, quality is the strategy. Infrastructure customers can’t afford pump failures. Semiconductor fabs can’t tolerate downtime. In both cases, performance and reliability aren’t features; they’re the product. Ebara’s reputation for high-quality technologies and services across water, air, and the environment created the kind of trust that turns vendors into long-term partners.

Strategic M&A Discipline: The Elliott acquisition shows what disciplined M&A can look like when it’s built on decades of shared work. Ebara didn’t buy Elliott as a cold, spreadsheet-driven expansion. It had lived with Elliott’s technology and products through long-term licensing collaboration, which reduced the classic acquisition risks: cultural mismatch, operational surprises, and paying for capabilities that don’t hold up under new ownership.

Put all of that together and you get the through-line of the entire company: Ebara has been able to keep contributing to society—and solving the problems of the era—because customers continued to choose it for the same combination it started with: reliable technology, deep engineering capability, and a founding spirit that still shapes how the work gets done.

XII. Analysis: Competitive Position & Strategic Moats

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

At the leading edge of semiconductor manufacturing, CMP isn’t a market with “a few competitors.” It’s effectively a two-supplier world. For the most advanced production lines—at process nodes below 14nm—CMP tools are essentially supplied by Applied Materials in the U.S. and Ebara in Japan.

That structure exists for a reason. The moat is built out of time. CMP performance depends on process knowledge that only accrues through years of iteration alongside customers. And even if a new entrant had the engineering talent, fabs don’t move fast when the downside is catastrophic. Qualifying a new tool takes years of proven performance, and the cost of a failure inside a billion-dollar fab makes customers extremely reluctant to take risks. Add in the capital required to build automated CMP manufacturing capacity—hundreds of millions of dollars—and “just entering the market” becomes close to impossible.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Ebara relies on specialized suppliers for key precision-machinery components, while maintaining more vertical integration in its traditional businesses. Its scale helps in negotiations, but in semiconductor equipment, certain critical components can become constrained during demand spikes—especially when the whole industry is trying to ramp at once.

Bargaining Power of Customers: MODERATE

On paper, Ebara’s customers are the most powerful buyers in the world: major fabs like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel. They buy in volume, they negotiate hard, and they have the engineering sophistication to push suppliers relentlessly.

But CMP is where buyer power runs into a wall. With supply concentrated in two companies controlling the vast majority of the market, alternatives are limited. And because qualifying equipment is expensive and slow, switching costs are real. Once a tool is proven and integrated into a process flow, customers tend to stay with it—less out of loyalty than out of operational necessity.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

CMP remains a non-negotiable step in advanced chip manufacturing. No other production-scale approach has emerged that delivers comparable planarization quality. The same is broadly true for dry vacuum pumps: fabs still need clean, stable vacuum environments for critical process steps. Until semiconductor manufacturing changes at a fundamental level, substitution risk stays low.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE TO HIGH

A duopoly doesn’t mean peace. It means the fight concentrates.

Applied Materials holds roughly 42% of global CMP share, while Ebara sits around 27%. With only two serious players at the cutting edge, competition is intense: R&D pace, uptime, contamination control, service response times, and the ability to ramp capacity all matter. Applied’s larger scale brings R&D and manufacturing advantages; Ebara’s long-standing relationships—especially in Japan and broader Asia—and its regional presence create real counterweights.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Ebara clearly benefits from scale in standard pumps, built around mass manufacturing systems like Fujisawa. But semiconductor equipment is a different game. Volumes are lower, and advantage comes less from unit cost and more from engineering performance, reliability, and execution in the field.

Network Effects: There aren’t classic network effects here. But Ebara does have something adjacent: an installed base. Dry vacuum pumps, in particular, create ongoing service demand and durable customer relationships that can deepen over time.

Counter-Positioning: Ebara’s diversified structure can look like a drawback next to pure-play semiconductor equipment companies. But it also creates a portfolio effect: steadier infrastructure-oriented businesses alongside a higher-growth precision machinery engine. That mix can make the company more resilient across cycles, even if it’s harder for the market to value cleanly.

Switching Costs: In semiconductor fabs, switching costs are built into physics and risk. Qualification takes years. Once a tool is validated, customers typically keep it in place for the life of the line, because changing equipment means re-proving performance at enormous cost.

Branding: In Ebara’s markets, brand doesn’t mean consumer awareness. It means trust. Reliability and technical excellence are the brand—and those attributes support premium pricing and reduce friction in winning new placements.

Cornered Resource: In CMP, Ebara’s dry-in/dry-out technology and the intellectual property around it function as a true cornered resource. But the bigger “resource” is less legal and more experiential: decades of process knowledge built through real deployments, failures, fixes, and incremental improvements that competitors can’t simply buy.

Process Power: Ebara’s advantage also shows up in how it manufactures. Automated facilities, quality systems, and repeatable production discipline—built over a century—translate into equipment customers trust to run at the edge. That kind of process power is slow to build and hard to copy.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For monitoring Ebara going forward, two KPIs are especially worth tracking:

-

Precision Machinery Order Growth: In equipment businesses, orders are the leading indicator. Strength here signals future revenue and captures how the semiconductor cycle is flowing through Ebara’s highest-value segment.

-

Operating Margin by Segment: Segment mix drives the whole story. Precision machinery tends to carry the highest margins, while infrastructure and environmental work can be more competitive and project-driven. Watching margins by segment is one of the cleanest ways to see whether Ebara is strengthening—or losing—its position in each business.

XIII. Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case: AI Supercycle Creates Sustained Demand

The bull case for Ebara starts with a simple idea: the world is going to need a lot more chips, and the chips it needs are getting harder to manufacture.

Semiconductor demand is rising across smartphones, AI, autonomous driving, and the broader digitization of industry. And as AI models scale, they pull the entire manufacturing stack toward more powerful chips built at the leading edge. Those leading-edge nodes, in turn, require more CMP steps—and that’s the flywheel for Ebara. More layers, tighter tolerances, more polishing, more demand for the tools that can do it reliably at scale. If fab investment keeps expanding globally, Ebara’s CMP and vacuum pump businesses should rise with it.

The second leg of the bull case is geography. The industry is diversifying beyond the historic centers of Taiwan and South Korea, with capacity growing in the United States, Europe, and Japan. That shift favors suppliers that can deliver not just hardware, but uptime and service across regions. Ebara’s global footprint and service infrastructure position it to follow customers as manufacturing spreads.

Then there’s optionality—especially hydrogen. Ebara plans to construct a new equipment testing and development center for hydrogen infrastructure in Futtsu City, Japan, intended to support the build-out of domestic and international hydrogen supply chains. The facility will run performance tests and develop elemental technologies using liquid hydrogen. If hydrogen becomes a major energy carrier, Ebara’s capabilities in liquid hydrogen pumps could become a meaningful new growth vector.

Finally, there’s valuation. Ebara often trades at a discount to pure-play semiconductor equipment companies despite having real exposure to one of the most concentrated, hardest-to-enter niches in chipmaking. The diversified structure can obscure the value of Precision & Electronics. For patient investors, that opacity can be the opportunity.

Bear Case: Cyclicality, Competition, and Transition Risk

The bear case begins where it always does in semiconductor equipment: the cycle still matters.

Even if AI creates a powerful long-term tailwind, it doesn’t repeal boom-and-bust dynamics. Equipment spending has historically fallen hard during downturns, and Ebara’s precision machinery business could see orders drop meaningfully in the next pullback. The key risk isn’t whether a downturn happens—it’s whether it hits before the current wave of capacity additions has fully played out.

Competition is another real threat. Applied Materials, with a significantly larger share of the CMP market, has scale advantages in R&D and manufacturing. As chip geometries push deeper into the angstrom era, the engineering challenges get harsher, and the premium on sustained innovation rises. If Applied extends its technology lead, Ebara could feel pressure in the highest-value placements.

There are also discrete, company-specific risks. On January 31, 2025, the Company and its two Indian subsidiaries received an arbitration claim from Kirloskar Brothers Limited (KBL) and Kirloskar Ebara Pumps Limited (KEPL). KBL and KEPL allege that the business of the Company and the two Indian subsidiaries breached non-competition obligations under the joint venture agreement. The arbitration is pending and represents legal risk that could affect Ebara’s operations in India.

The Energy segment carries its own transition risk. Elliott has acknowledged that its oil and gas base is being challenged by green transition and decarbonization trends. While Elliott is investing in areas like hydrogen and carbon dioxide compression, the path between the old world and the new can be messy—potentially pressuring revenue and margins in the meantime.

And then there’s geopolitics. Ebara has deep exposure to Asian fabs, which has been a strength, but could become a vulnerability if U.S.-China tensions further constrain semiconductor trade. Export control rules already add friction. Further escalation could narrow Ebara’s addressable market or complicate customer deliveries.

The Balanced View

The most grounded way to see Ebara is as an essential infrastructure company with real semiconductor upside.

Its products sit beneath modern life: water systems, energy and industrial machinery, environmental solutions, and the precision tools that enable advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Those end markets behave differently across cycles, which can make Ebara more resilient than a pure-play chip equipment supplier. At the same time, Precision & Electronics gives Ebara exposure to one of the strongest growth engines in the global economy.

The risks are real—and they’re mostly the kinds of risks that come with playing in hard arenas. Cyclicality will happen; the question is whether Ebara keeps investing through downturns without losing position. Applied Materials will keep pushing; the question is whether Ebara continues to earn trust at the cutting edge. The energy transition will reshape demand; the question is whether Elliott’s capabilities map cleanly onto what comes next.

Ebara’s history argues it can manage that balance. It has survived earthquakes, war, economic stagnation, and repeated technological resets. The cultural through-line has been remarkably consistent. The company’s founding spirit—“Netsu to Makoto,” passion and dedication—started with Issey Hatakeyama walking to his professor after a bankruptcy and asking for one more chance to keep the work alive. A century later, it shows up in automated factories and mission-critical tools running inside the world’s most advanced fabs.

The open question isn’t whether Ebara can execute in the next quarter. It’s whether it can keep doing what it has always done: carry its strengths forward, take on the next hard set of problems, and keep compounding for the long run.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music