Kubota Corporation: From Iron Foundry to Global Agricultural Powerhouse

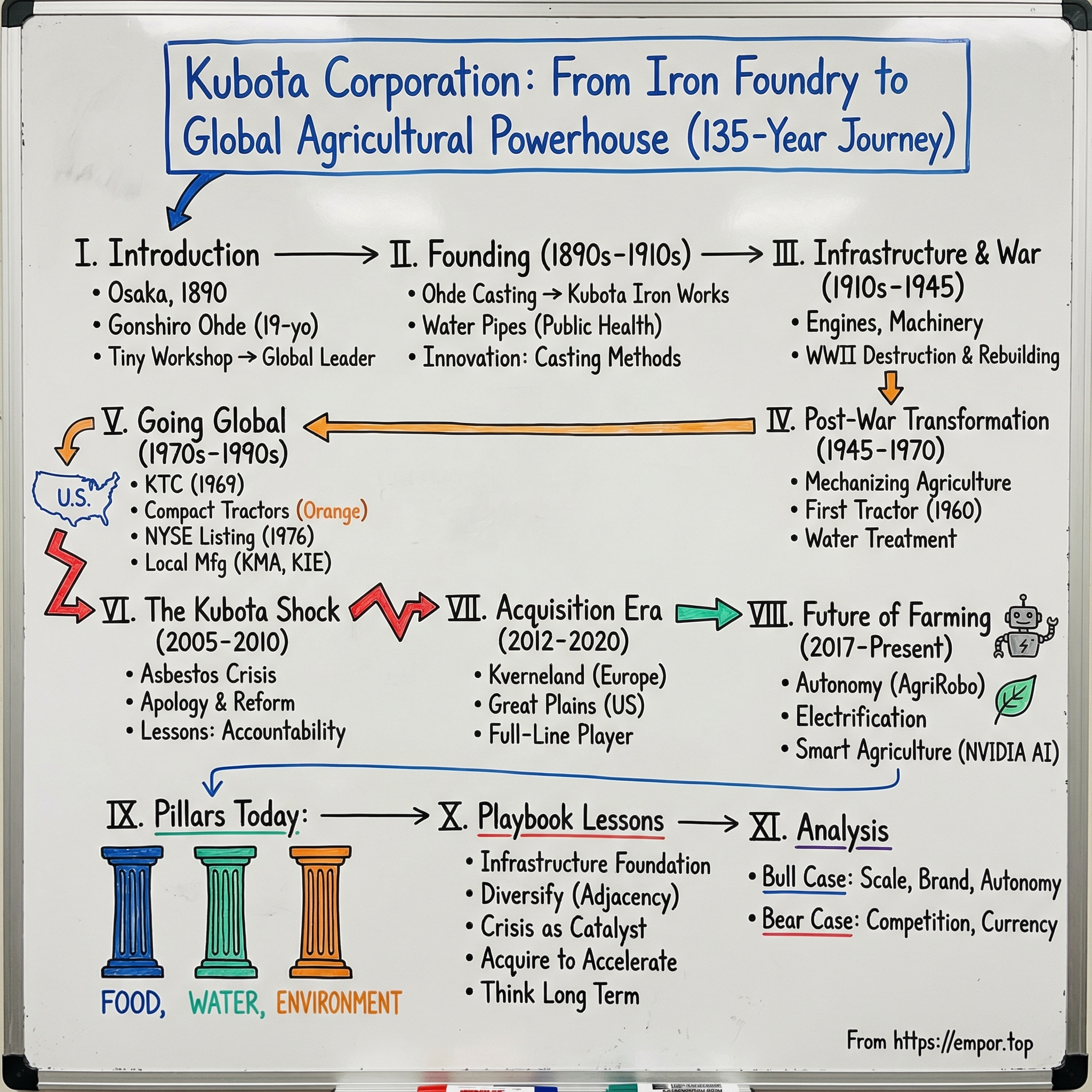

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

In Osaka’s Nipponbashi district—today a bright maze of electronics shops and pop culture—there was once a worn-down tenement house. Back in February 1890, in one cramped corner of that building, a 19-year-old metalworker lit a furnace and started taking jobs. His name was Gonshiro Ohde. History would later know him as Gonshiro Kubota. And that tiny workshop—just 26 square meters—would become the spark for one of the most important industrial companies in modern Japan.

Fast forward to today: Kubota spans 180 companies across 120 countries, with roughly 52,000 employees. It generates about 3.20 trillion yen in revenue, and around 80% of its business now sits outside Japan. Those orange tractors on American hobby farms, the mini excavators on construction sites, the pipes carrying water beneath major cities, the machines harvesting rice across Southeast Asia—all of it traces back to that first furnace in Osaka.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: how did a teenage ironworker’s one-room casting shop in Meiji-era Japan turn into a global leader in tractors, construction equipment, and water infrastructure?

The answer is a 135-year case study in industrial evolution: a company that kept finding the next essential problem to solve. Sometimes that meant building the literal foundations of public health. Sometimes it meant reinventing itself after catastrophe. And sometimes it meant making bold bets—on new markets, new technologies, and acquisitions that changed what the company could be.

In 1976, Kubota became the third Japanese company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, a very public signal that it was serious about becoming global. But that moment only makes sense in context. This is a company that survived the destruction of World War II, helped mechanize Japan’s rice paddies during the postwar economic miracle, endured an asbestos crisis that became national news—the “Kubota Shock”—and today is pushing hard into autonomous, AI-driven farming.

A few threads run through everything Kubota does. First: nation-building through infrastructure. Kubota’s early water pipe business didn’t just make money—it helped cities fight disease and modernize fast. Second: pivoting through crisis. Time and again, external shocks forced change, and Kubota responded by widening its capabilities rather than shrinking its ambitions. Third: acquisitions as acceleration. Buying Kverneland in Norway and Great Plains in Kansas didn’t just add products; it turned Kubota from a specialist rooted in rice farming into a full-line global equipment maker. And finally: the next agricultural revolution. Partnerships like the one with NVIDIA, autonomous tractor programs, and its presence at CES all point toward a future where farms run with far fewer human hands.

The key to understanding Kubota is that it has never been only one thing. The company builds tractors and agricultural machinery, construction equipment, engines, vending machines, pipe, valves, cast metal, pumps, and systems for water purification, sewage treatment, and air conditioning. From the outside, that can look like sprawl. From the inside, it’s a pattern: pay attention to what society urgently needs, then build the machine—or the pipe, or the engine—that makes it possible.

And it all starts with the founder.

II. Founding & The Vision of Gonshiro Kubota (1890–1910s)

Picture a boy on a hill above Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, staring out at cargo ships and the occasional steam-powered vessel cutting across the horizon. Gonshiro Ohde—who the world would later know as Gonshiro Kubota—was born in Ohama Village on Innoshima, an island in the Seto Inland Sea. Today, it’s Ohama Town in Innoshima, part of Onomichi City in Hiroshima Prefecture.

The Ohde family wasn’t destitute, but they weren’t secure either. They had enough to live, and the parents and their four children got by happily—until the rules of the economy changed beneath their feet. As Japan shifted from paying land taxes in rice to paying in cash, the family’s finances tightened fast. When Gonshiro was seven or eight, he watched his parents struggle and made a promise that would steer his entire life: he would succeed in business and bring laughter back to his home.

That moment didn’t turn him toward the sea—it turned him toward metal. He didn’t dream of becoming a sailor. He dreamed of becoming a blacksmith, a Western-style craftsman who could build the machines that powered the modern world he saw offshore. This was Meiji-era Japan, a country sprinting into industrialization after centuries of isolation. Those steam vessels weren’t just impressive; they were proof that the future belonged to people who could make things.

There was only one problem: Osaka was far away, and his parents refused to let their son go.

So he went anyway. At 14, Gonshiro slipped onto a boat, taking whatever work he could—kitchen help, hauling water—just to earn his passage to the city.

Osaka was not the welcoming land of opportunity he’d imagined. When he arrived in the spring of 1885, the city was in the grip of a severe recession, a downturn tied to the rebound from special procurements for the Satsuma Rebellion and the effects of budget austerity. He went from shop to shop looking for work and got turned away at the door. Some nights, he slept under the eaves of houses.

Right as his small stash of money ran out, he landed at Kuroo Casting. Gonshiro pleaded with the master, Komakichi Kuroo, until he was finally allowed to stay—not as a craftsman, but as a live-in helper: babysitter, cleaner, errand boy. He wasn’t taught the core techniques at first. So he taught himself. He watched while he worked, memorized movements, handled tools and finished products whenever he could, and studied the craft in stolen moments. Over time, the master saw the sincerity and the hunger. Gonshiro was allowed into the first steps of casting—and before long, his skill outpaced veteran craftsmen.

After finishing his apprenticeship, he moved again, determined to learn more and, crucially, to save enough to open a shop of his own. When he left Kuroo Casting, the master gave him a parting gift of 10 yen, bringing Gonshiro’s total to 21 yen and 60 sen. But the going rate to start a casting works was around 100 yen. At Shiomi Casting, he earned 25 sen a day—meaning the dream was still far off. Gonshiro saved relentlessly, and in about a year and a half he hit his target.

In February 1890, still only 19, he rented a corner of an old tenement house and opened Ohde Casting. That furnace in a cramped room was the beginning of what would become Kubota’s story.

The first products were humble: fittings, and weights for scales. But even getting started was a fight. The next summer, in 1891, the landlord told him to leave. Neighbors complained about dust and the fire risk. In the first five years, the business was forced to move three times—hardly the stable foundation of an industrial empire.

And yet Gonshiro wasn’t thinking small. He was fixated on a national problem: water.

At the time, Japan depended on imported pipes for waterworks. People tried to manufacture them domestically, but the technology wasn’t there, and the efforts failed. Gonshiro decided he would figure out how to make cast iron water pipes in Japan—not for a niche market, but “for the sake of the country.” And it turned out to be far harder than he imagined.

This wasn’t just an engineering challenge. Cholera and other waterborne diseases were ravaging cities. Modern water systems—and pipes that didn’t crack, leak, or fail—weren’t a convenience. They were public health infrastructure. Kubota was founded in 1890 when cholera was still a major problem in Japan, and Gonshiro set out to help solve it by supplying safe water through mass-producing water pipes.

His breakthroughs came step by step. In 1897, he developed the joint-type casting method. In 1900, he followed with the vertical round-blow casting method. In 1904, he developed vertical-blow rotary-type casting equipment, and with it, the mass production of iron pipes became possible.

Around this same period, a relationship formed that would reshape Gonshiro’s life. One of Ohde Casting’s customers was Kubota Match Machine Manufacturers. Its master, Toshiro Kubota, had studied German match-carving equipment and built high-precision Japanese machinery, helping drive match exports. Watching Gonshiro pour himself into the seemingly impossible mission of domestic water pipe production, Toshiro took an interest. Over time, he began to look after the young founder—and eventually asked Gonshiro to become his adopted son.

Gonshiro agreed after consulting his siblings, but on one condition: he would be able to continue the water pipe work. He took the Kubota name, and Ohde Casting became Kubota Iron Works.

Out of these early years—sleeping under eaves, teaching himself a craft, being forced to move shop after shop, and chasing a problem bigger than his own business—came the philosophy that would define Kubota for generations: manufacturing that benefits society. Not just making things to sell, but making things that matter.

III. Building Japan's Infrastructure: Pipes, Engines & War (1910s–1945)

By the 1910s, Kubota had become Japan’s premier maker of iron water pipes. But Gonshiro Kubota had already learned the hard lesson that no market climbs forever. Around 1912, as a long recession at the end of the Meiji period set in, cities, towns, and villages began pulling back on new waterworks construction. Demand for iron pipes dropped sharply.

Gonshiro didn’t wait it out. He pivoted.

In 1914, he put lathe casting techniques to work and began manufacturing lathes in a corner of the main plant in Funade-cho. It started small, but the menu of machines steadily expanded—milling machines, boring machines, planing machines—each one strengthening the company’s foundations beyond pipes.

Then World War I reshaped Japan’s economy. While Europe’s factories were consumed by war, Japanese industry boomed. In 1917, Kubota delivered a steam engine for cargo boats, a single order that opened the door to ship machinery. From there, the expansion kept rolling: machinery for steel manufacturing, engines for farm machinery and industry, and diesel engines. The goal was straightforward—stabilize the business by building multiple legs under it.

In 1922, Kubota made a move that, in hindsight, reads like destiny. It began producing kerosene-driven engines for agricultural and industrial use. These oil-based engines were Kubota’s first real step into the world of farming equipment—not with a tractor yet, but with the power source that would eventually make tractors possible. The engines quickly gained attention. By 1925, the Kubota Oil Engine was winning gold medals at agricultural expositions. In 1930, the Ministry of Commerce designated it an “Excellent Domestic Product.”

At the same time, Gonshiro had another ambition—cars.

Automobiles were spreading across Japan in the middle of the Taisho period (1912–1926), and he wanted to build something small and affordable for the Japanese market. In 1919, he established Jitsuyo Jidosha Co., Ltd., bought a patent from an American inventor, William R. Gorham, and started manufacturing. But the timing turned brutal. Mass imports of American cars, including Fords, made competing on price and scale nearly impossible.

Still, Kubota’s fingerprints ended up on Japanese automotive history. In 1931, a small car completed a non-stop road test from Osaka to Tokyo and went on sale under the name Datson. The effort continued, but the business couldn’t outrun foreign competition. Ultimately, the shares in the company were transferred to Tobata Casting Co., Ltd.—a company that would later become Nissan Motor Company. Kubota, almost by accident, had played a role in the early story of a future automotive giant.

Back at Kubota itself, 1930 brought a different kind of turning point: the company grew up. What had started in 1890 with roughly 100 yen and a furnace in a rented corner had, over five decades, become a large enterprise. Kubota Limited was incorporated that year, formalizing the structure and ensuring the business could thrive beyond the founder’s direct control.

Then came World War II, and with it, total mobilization. Kubota’s industrial capacity was drawn into the war effort. The Mukogawa plant (now the Hanshin plant) was completed to expand machine tool production. The plant produced items like air compressors and hoist machinery for mines, and its facilities were expanded repeatedly as demand intensified.

And then, in 1945, it all came crashing down. Repeated air raids destroyed the Funade-cho plant. Plants in Ichioka and Tsurumachi, along with the Tokyo branch office, suffered extensive damage. Every other plant was hit to some degree. Japan’s cities burned, its industry fractured, and its people faced hunger.

But inside that ruin was the shape of the next chapter. Out of the wreckage, Kubota was about to find its most consequential mission yet.

IV. Post-War Transformation: Mechanizing Japanese Agriculture (1945–1970)

In the wake of World War II, Japan’s defeat was quickly followed by something just as terrifying: the risk of hunger on a national scale. Poor weather, labor shortages, and a battered economy pushed food supplies to the edge. For ordinary families, it wasn’t an abstract “shortage.” It was whether there would be enough to eat.

Kubota’s answer was to point its factories and engineers toward the fields. The company began research and development in agricultural machinery, and in 1947 introduced a cultivator—an early step into what would become a defining business. From there came a steady march of machines: tractors, rice transplanters, binders, and combine harvesters. Kubota’s agricultural machinery became part of the post-war surge in food production that helped stabilize the country.

This wasn’t just diversification. It was nation-building, again—only this time, not with pipes under streets, but with machines in paddies.

The engineering challenge was uniquely Japanese. Farms were small, fragmented, and often waterlogged. Rice paddies had been worked by hand for centuries, and the machinery that worked on big, dry Western fields didn’t translate. Kubota had to build equipment that was compact enough for tight plots, capable of operating in flooded conditions, and affordable for farmers who couldn’t bet the farm on one purchase.

By 1960, Kubota hit a turning point: it introduced its first tractor. That moment didn’t just add a product line—it signaled that Japan’s mechanization era had truly arrived. And Kubota didn’t treat the tractor as a standalone hero machine. It built a system around the rice cycle itself: specialized equipment for preparation, planting, and harvest. Rice transplanters took on the grueling work of setting seedlings into mud. Combine harvesters automated cutting and threshing. These weren’t simple copies of foreign designs. They were purpose-built innovations for rice agriculture.

Just as important was how Kubota went to market. It didn’t want to be a distant manufacturer that dropped off iron and disappeared. It positioned itself as a partner to farmers, supported by dedicated dealers and a relationship-driven approach. That closeness—earned field by field—would become a real strategic asset when Kubota later tried to win customers far from Japan.

While agriculture was taking off, Kubota’s original calling—water—was evolving too. Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1960s brought a new problem: pollution. Clean water wasn’t enough if the downstream reality was untreated wastewater. Kubota moved quickly, establishing its Water Treatment Business Division and expanding from water supply into sewage and treatment. The mission stayed the same: protect public health by building the systems society needs.

This era also saw Kubota step onto construction sites. The company established Kubota Kenki K.K. and began producing construction equipment, along with marine deck machinery. Compact machines, in particular, fit Kubota’s strengths: small, precise, and built for tight working environments. In 1974, Kubota introduced its own compact mini excavator, helping make groundbreaking work easier and setting the stage for a product category that would later become a global signature.

And quietly, almost in parallel, Kubota began testing the world beyond Japan. Its water pipes had been exported to Asia starting in the 1930s, and would eventually carry water in more than 70 countries. One early milestone captured the company’s identity perfectly: its first overseas order was for a water supply project in Phnom Penh, Cambodia—an international debut that matched the purpose it was born from.

By the late 1960s, Kubota was no longer just an infrastructure company that happened to make engines. It had become the dominant force in Japanese agricultural machinery and a major player in water-related systems. But its leaders could see the ceiling: Japan’s home market was finite. If Kubota was going to keep growing, it would have to go where the farms—and opportunities—were bigger.

The next chapter would take Kubota across the Pacific.

V. Going Global: The U.S. & International Expansion (1970s–1990s)

In 1969, Kubota made the kind of decision that changes a company’s trajectory forever. Under a new motto—"Create an environment affluent to human beings"—it established Kubota Tractor Corporation and walked straight into the United States.

On paper, that move looked ambitious bordering on reckless. The U.S. was the world’s most competitive tractor market, dominated by entrenched American brands and built around big, high-horsepower machines. Kubota didn’t try to out-Deere John Deere. Instead, it did something far smarter: it found the gap.

In North America, Kubota essentially created a new market for compact tractors powered by diesel engines. At the time, gasoline-powered equipment was still the mainstream choice for this size class. Kubota’s compact diesels were durable, efficient, and right-sized for a growing set of customers: homeowners with acreage, hobby farmers, and landscaping businesses that needed real capability without a full-size farm tractor. Kubota wasn’t just selling a product. It was defining a category—and painting it orange.

Then the 1970s hit, and the world got messy. The 1973 oil crisis rattled Japan’s export-driven economy and squeezed companies like Kubota from multiple directions: domestic recession, global uncertainty, and rising trade friction. Kubota responded the way it often does—by going wider, not narrower. It expanded its overseas footprint, establishing offices in New York and Düsseldorf in 1975; Jakarta and Athens in 1976; London in 1977; and Mexico in 1982.

And in 1976, Kubota made a statement that it intended to play this game globally. In November, it became the third Japanese company to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange, after Sony and Honda. For investors, it was a signal: this wasn’t a Japan-only manufacturer exporting opportunistically. Kubota was building itself into an international enterprise.

The 1980s added another push. Trade tensions between Japan and the United States made it increasingly important to manufacture locally—and not just to avoid politics and tariffs. Building in-market meant designing in-market. Kubota started shifting production overseas, including the start of compact construction equipment production in Germany and tractor implement production in North America in 1989. It also did something unusually hands-on for a manufacturer expanding abroad: it deployed development engineers into overseas regions, putting them close to dealers and customers so products could be shaped around local realities rather than headquarters assumptions.

In the U.S., that strategy concentrated in Georgia. Kubota built out its American manufacturing presence around two bases in Atlanta, Georgia: Kubota Manufacturing of America Corporation (KMA) and Kubota Industrial Equipment Corporation (KIE). KMA manufactured mowers and utility vehicles, helping Kubota become not just an importer with a sales arm, but a brand with real industrial roots in the market.

This era also produced one of the strangest footnotes in Kubota’s story: 3D graphics chips. In the early 1990s, as computing power surged and “digital” seemed like the future of everything, Kubota set up a subsidiary to develop graphics processing hardware. It didn’t work out. But the point is that Kubota tried. For a company best known for iron, engines, and agriculture, it was a revealing moment—evidence of a corporate culture willing to experiment, even at the risk of looking a little odd in hindsight.

Back on the core business, the bet in America paid off. Kubota became firmly established as a compact tractor brand in the U.S., taking a high share of the market for compact tractors of 40 horsepower and below. By the early 1990s, its position in the category was no longer a surprising success story—it was the new normal, with Kubota holding more than a 40% share of the compact tractor market.

But as Kubota’s global ambitions accelerated, a very different kind of reckoning was quietly building back in Japan—one that would test the company’s values in a way no expansion plan ever could.

VI. The Kubota Shock: Crisis & Redemption (2005–2010)

On June 29, 2005, a front-page article in the Mainichi Shimbun—one of Japan’s major national newspapers—set off an explosion. It reported that asbestos-related disease had taken the lives of workers at Kubota’s former Kanzaki plant in Amagasaki City. What followed became known nationwide as the “Kubota Shock.” For more than a year, asbestos dominated the headlines, with relentless daily coverage and a public suddenly asking: how could this still be happening?

Kubota’s own disclosures only deepened the impact. In its statement that day, the company acknowledged that dozens of people connected to the Kanzaki asbestos-cement pipe plant had died. Kubota reported that 51 former workers had died from mesothelioma—the signature cancer linked to asbestos exposure—and that five nearby residents had also died from the disease.

The scale of the tragedy became clearer over the months that followed. By March 2006, 105 employees from the factory—about 10% of the total workforce—had died of asbestos-related diseases. The Kanzaki plant had manufactured asbestos cement pipes from 1954 to 1975, and asbestos cement housing materials from 1960 to 2001. For decades, deadly fibers had been part of the working environment—and, tragically, part of the surrounding community’s environment too.

And because the company involved wasn’t a fly-by-night operator but a long-established, respected industrial name, the story didn’t stay contained. Kubota’s admissions cracked open the entire issue. Within days, other companies began making their own disclosures, and the Kubota Shock turned into a broader national reckoning over how industrial health risks had been handled—at work sites and beyond their gates.

What happened next would come to define Kubota’s response at least as much as the scandal itself.

Kubota’s president, Daisuke Hatakake, met with residents living near the asbestos factories and apologized. Residents said that while he did not clearly acknowledge a causal relationship between the factory and their illnesses, he expressed a moral responsibility and promised to establish a compensation regime for residents similar to what Kubota offered employees.

Kubota went on to officially apologize to environmental victims near its plant and their families, and set up a compensation scheme for them. The program was voluntary—beyond what was legally required—and, following negotiations, Kubota agreed to pay compensation at levels equal to what victims could obtain through litigation. By June 15, 2022, 398 residents—most of whom had contracted malignant mesothelioma—had been identified.

The consequences rippled outward into government policy. Relevant ministries were forced to disclose information, and they asked a wide range of public and private organizations to verify and disclose their past asbestos use, any asbestos victims at their companies, and the presence of asbestos-containing materials in buildings and facilities.

Out of those measures came sweeping reform. Japan enacted a new “Asbestos Victims Relief Act” in 2006. That same year, the Air Pollution Control Act, the Local Government Finance Law, the Building Standards Act, and the Waste Disposal Act were amended. In 2006, after the Kubota Shock, the Japanese government banned items with more than 0.1% asbestos, and by 2012 all asbestos products were banned. The Kubota Shock also helped drive the Act on Asbestos Health Damage Relief, which provided compensation to people not covered by workers’ compensation.

The tragedy didn’t end when the news cycle moved on. Among the Kubota plant’s workforce, 252 people had developed asbestos-related diseases and 228—about 90%—had died by December 2022. Even years later, new victims continued to be diagnosed because asbestos-related diseases can take decades to appear.

So how did Kubota survive a reputational catastrophe this severe? It did it by accepting responsibility, establishing compensation mechanisms with real teeth, and incorporating the lessons into its corporate culture. The Kubota Shock could have been the moment the company was defined by its worst chapter. Instead, it became a turning point—one that forced Kubota to confront what it owed not just to customers and shareholders, but to workers, neighbors, and the communities its factories touched.

VII. The Acquisition Era: Kverneland, Great Plains & Becoming a Full-Line Player (2012–2020)

Even as Kubota worked to rebuild trust after the Kubota Shock, its leadership was also preparing the next reinvention. The company had a strong position in compact tractors and deep expertise in rice farming. But if it wanted to compete with the global giants—John Deere, CNH Industrial, and the rest—it couldn’t just be great at one slice of agriculture. It needed to become a full-line equipment maker: tractors plus implements, in every major farming system, across the world.

The first big leap came in 2012, with the acquisition of Kverneland Group. Kverneland’s story begins in 1879, when Ole Gabriel Kverneland built a small forge in Kvernaland, outside Stavanger, Norway. He called it “O.G. Kvernelands Fabrik” and started by making scythes. Ole Gabriel was an inventor as much as a blacksmith—he designed a water-powered spring hammer, then scaled into early mass production, turning out thousands of scythes a year.

Over the following century, Kverneland evolved into something much bigger. Starting in the mid-1990s, it expanded rapidly through acquisitions of well-known implement manufacturers. By the time Kubota bought the company and took full ownership in May 2012, Kverneland had assembled a wide portfolio and a European manufacturing and distribution footprint that would have taken Kubota decades to replicate from scratch.

The acquisition instantly changed what Kubota could offer outside Japan. Kverneland brought implement brands such as Underhaug bale wrappers, Taarup disc mowers and hay tools, Maletti rotary harrows, Accord seeding machines, the Dutch Greenland Group’s fertilizer spreaders and grass machinery, and RAU field sprayers. Put simply: Kubota went from “tractor company” to “tractor-plus-implements” in Europe almost overnight.

And Kubota wasn’t buying Kverneland for a quick flip. As Kverneland’s Løyning put it: “Unlike our previous investor who was looking for short-term returns, Kubota sees Kverneland Group's potential for growth and profitability in the long-term.” That long-horizon mindset—patient capital, steady integration, and investment rather than extraction—would become the pattern.

It also opened the door to a more modern vision of farming equipment: not just machines, but systems. Kubota and Kverneland began working closely on “Tractor + Implement” smart solutions such as TIM (Tractor Implement Management) and telematics, pushing joint development in automation and digitalisation.

Then, four years later, Kubota made an even louder statement—this time in North America. In 2016, it agreed to acquire 100% of Great Plains Manufacturing for approximately US$430 million, subject to provisions in the agreement. This wasn’t a cold start. Kubota already had an alliance with Great Plains’ turf and landscape implement division, Land Pride, going back to 2007. The acquisition turned that partnership into a platform.

The scope mattered. The deal included all five Great Plains divisions—Great Plains Ag Division, Great Plains International, Land Pride, Great Plains Acceptance Corporation, and Great Plains Trucking—along with multiple facilities in Kansas and a manufacturing plant in Sleaford, England.

Great Plains itself had an origin story with classic Midwest grit. It was founded in 1976 by Roy Applequist, who started by building a new grain drill for the U.S. Central Plains and grew the business into a leader in tillage tools and seeding equipment. In April 2016, the company marked 40 years since that first drill. Applequist, still serving as chairman, would help guide the transition with Kubota.

Just as important as what Kubota bought was how it planned to run it. The company emphasized it wouldn’t bulldoze what made Great Plains work: “Kubota says for the foreseeable future, all five of Great Plains divisions will continue to operate as they have with their infrastructure intact and with respect to the distinctiveness of the brands, trademarks and operational strengths.”

Inside the Kubota orbit, leaders could see the strategic picture snapping into place. Dai Watanabe, President and CEO of Kverneland Group, said the Great Plains acquisition would create positive synergies on implements and “significantly strengthen our joint position as a Global Provider of Intelligent and Efficient Farming System.”

That wasn’t just optimism. It was real product logic. With Kverneland’s European hay tools and Great Plains’ seeders and tillage equipment suited to North American farming methods, Kubota could finally offer a more complete lineup—one that looked like a full farming system instead of a single orange machine.

At the same time, Kubota was making another move it had to make: going upmarket in tractor horsepower. Rice farming had made Kubota great, but dry-field farming is the larger global opportunity—there is thought to be roughly four times more agricultural land devoted to dry fields than to rice. Expecting global population growth and rising food demand, Kubota chose to enter that market. After years of testing, it completed development of the large M7001 tractors for dry-field farming in 2014, began mass production at a new plant in France, and earned strong reviews at an international trade fair.

The product march continued. M7 Series Gen 2 tractors were offered in ratings from 128 to 168 horsepower, powered by Kubota’s V6108 Tier 4 engine. Then came the M8 Series—180 and 200 horsepower models powered by Cummins B6.7 Performance Series engines. These became Kubota’s largest tractors ever, built for commercial livestock and row-crop production markets in North America and Europe.

And Kubota didn’t bet on a single geographic playbook. In India—the world’s largest tractor market—it pursued scale through partnership. The company invested in Escorts Limited, a leading local manufacturer, to deepen its presence in an intensely competitive market with huge growth potential.

That relationship escalated quickly. In March 2020, Kubota acquired a 10% stake in Escorts Limited for ₹1,042 crore through preferential allotment. In November 2021, it raised its stake from 9.09% to 14.99%. In June 2022, Kubota increased its stake to 44.80% following an open offer and subscription to new shares, and the company was renamed Escorts Kubota Limited. Kubota’s stake then increased to 53.50% after the cancellation of shares held by the Escorts Benefit and Welfare Trust.

By 2020, the direction was unmistakable. Kubota was no longer just a compact tractor specialist with dominance in rice-country machinery. Through acquisitions and deliberate product expansion, it was assembling the profile of a true full-line global player—equipped to serve farmers from Japanese paddies, to Kansas wheat fields, to India’s vast tractor market.

VIII. The Future of Farming: Autonomy, Electrification & Smart Agriculture (2017–Present)

At the Japan World Exposition in Osaka in 1970, Kubota rolled out a concept it called the “Dream Tractor”—a glimpse of what mechanized farming might become. Fifty years later, for its 130th anniversary, Kubota unveiled a successor that felt like science fiction with a purpose: the X tractor, or “cross tractor.”

The X tractor was a fully electric concept designed not just to drive, but to think. Kubota said it could autonomously navigate both standard fields and rice paddies using GPS, cameras, and other onboard sensors guided by AI. It was also envisioned as an always-on farm manager—monitoring weather and crop growth and deciding when to head out for jobs like seeding, tilling, or harvesting. Technical specifics were kept light, but Kubota described a power setup that combined lithium-ion batteries with solar panels. The message was clear: autonomy and electrification weren’t side projects. They were the next platform.

And while the X tractor itself was a concept, the program behind it was already moving into the real world. Kubota’s AgriRobo autonomous technology effort began shipping in Japan in 2017, starting with the SL60A, and expanding into the 100-horsepower class by 2020. Kubota framed this as a roadmap with three steps—and by the mid-2020s, it was already deep into Step 2: “automation and unmanned operation under monitoring by people.”

In 2024, Kubota reached a milestone it had been building toward for years: it introduced what it described as the world’s first combine harvester that could harvest rice and wheat automatically with no one riding onboard. With that, Kubota said it had completed a full lineup—tractors, combine harvesters, and rice transplanters—capable of unmanned operation. In rice farming, it positioned itself as the only manufacturer offering that complete unmanned lineup.

But Step 3—true, completely unmanned operation—raises the hardest problems: perception, decision-making, and safety in messy, unpredictable environments. Kubota’s answer was to bring in a partner whose entire identity is computation. In October 2020, Kubota announced a strategic partnership with NVIDIA, the California-based semiconductor company known for GPUs and AI computing platforms. Kubota’s interest wasn’t “cloud AI” in the abstract. NVIDIA’s end-to-end AI platform approach fit the kind of autonomous systems Kubota was trying to build: machines that sense the world, interpret it, and act—reliably, in real time.

By then, Kubota’s autonomous product lineup had already broadened. After Step 1, “automated steering with a farmer onboard,” it moved into Step 2, where machines can work without a rider while being monitored by people. Tractors came first, then rice transplanters and combine harvesters, all under the “AgriRobo Series” name. By 2024, around 700 machines in that series had shipped and were in use across Japan.

Kubota’s ambition wasn’t limited to Japan, either. For European markets, it developed autonomous AgriRobo tractors designed to switch between manual, remote, and autonomous operation. The pitch was practical: drive the tractor down the road like normal, get to the field, then activate autonomous mode so the machine does the work. Kubota also highlighted remote operation features, including the ability for a farmer to control two tractors at once using a tablet, a dedicated remote controller, or an in-cab screen.

Autonomy is only one half of the bet. The other is power. Kubota has also been researching zero-emission agricultural machinery—improving conventional power sources while developing electric drive and fuel-cell battery approaches. Farming equipment has a tougher job than passenger vehicles: higher horsepower demands, longer duty cycles, and harsh field conditions. Still, Kubota’s testing and iteration—particularly in Europe, shaped by real-world agricultural needs—produced meaningful progress. In one example Kubota shared, a small tractor could handle about half a day’s work on roughly an hour of charging.

By late 2024, Kubota’s push into robotics was getting recognized on the world stage. Kubota North America announced it had earned a “Best of Innovation” honor in the CES Innovation Awards 2025 for the Kubota KATR: a compact, four-wheeled, multifunctional robot designed for demanding off-road work in agriculture and construction.

The KATR’s signature feature is stability. It uses a system that adjusts four hydraulically actuated legs to keep a cargo deck level on uneven ground, including hills and slopes. Kubota described a proprietary algorithm processing sensor data in real time and commanding the legs to extend or retract to maintain that level platform. Four independent motors provide the traction and control to navigate difficult terrain.

At CES 2025, Kubota used that momentum to tell a bigger story. Under the theme “Smart Innovation for You,” its exhibit positioned automation, AI, and sustainability as tools to tackle the linked challenges of food, water, and the environment—across agriculture, construction, and residential equipment.

And the urgency behind all of this isn’t theoretical. It’s demographic. Japan’s commercial farming population—about 10.46 million in 2000—was projected to fall to about 3.23 million by 2025. Over the same period, the share of farmers aged 65 and older was expected to rise from about 28% to 47%. Japan is simply the leading indicator; similar dynamics are playing out across developed economies. In that context, autonomous machinery stops being a shiny feature and starts looking like the only way to keep fields in production with fewer human hands.

IX. Kubota's Three Pillars: Food, Water & Environment Today

Step back and Kubota starts to look less like a company with too many product lines, and more like a company built around three needs society never outgrows: food, water, and the environment. Tractors and construction equipment help grow and move what the world needs. Pipes and water treatment systems keep cities healthy. And the “environment” work is what ties the whole mission together in an era where sustainability and infrastructure are inseparable.

Start with the business that made Kubota in the first place: water. Kubota technology is used in over 80% of the advanced water purification facilities that provide safe, drinkable tap water in Japan. That’s not just market share—it’s a century-plus of trust, engineering know-how, and hard-won relationships with municipal governments.

The company remains deeply entrenched in its original waterworks footprint: about 60% of the water pipes in Japan, and about 80% of the treatment equipment in advanced water purification facilities. It’s a legacy position that tends to produce stability—demand tied to essential services, replacement cycles, and long-term public investment.

Kubota has kept pushing the edge of what those systems can do. It has produced ductile iron pipes with a diameter of 2.6 meters—the world’s largest—and developed what it describes as the world’s first earthquake-resistant ductile iron pipes. Those products support water infrastructure not only in Japan, but overseas as well. More broadly, Kubota’s pipes are respected worldwide for durability and performance, and today they support infrastructure in more than 70 countries.

Food is the pillar most people recognize, because it’s the one painted orange. In agricultural machinery, Kubota holds leading positions across multiple categories and regions. In North America—its largest market by sales—the company established itself early as a pioneer and leader in subcompact tractors (under 40 horsepower), beginning with its first overseas tractor distribution company in 1972. In Asia, Kubota leans into what it does best: rice farming machinery, with leading tractor and crawler combine harvester shares in Japan and across ASEAN.

And “food” at Kubota also includes the equipment that builds the world around farming: construction machinery. The company has held the leading global share in mini excavators for about two decades, and it has the second-highest share in compact track loaders in North America. Kubota was one of the first mini excavator makers to export overseas, and that early global push helped earn the category an excellent reputation worldwide.

In the U.S., Kubota’s story has largely been the story of compact equipment. Its market share has grown dramatically, especially in the under-40-horsepower segment. Estimated market share of the compact tractor segment today is around 25%, a rise powered by the increasing popularity of compact tractors on small farms, acreages, and specialty operations.

That matters because the market itself has shifted toward Kubota’s sweet spot. Data from the Association of Equipment Manufacturers show that 65% of tractor sales today come from the under-40-horsepower segment. If most of the volume is in that class, being the dominant brand there isn’t a niche—it’s a strategic advantage.

All of this stacks into a business model that’s geographically diversified. The idea is simple: when one region softens, others can offset. In North America, revenue for construction machinery is expected to be steady, even as tractor revenue is shrinking. In Europe, sales are not expected to recover, but are expected to stabilize compared to the previous year. Meanwhile, in Asia, sales are projected to increase year over year as the region is expected to recover from drought.

The financial results show both the resilience and the reality of running a global heavy equipment manufacturer. In 2024, Kubota reported consolidated revenue of ¥3,016,281 million, a slight decrease of 0.1% year over year. Operating profit fell by 4% to ¥315,636 million, representing a 10.5% margin—still a double-digit operating margin in a tough, capital-intensive business.

But there are near-term headwinds. Operating profit is expected to decrease due to the appreciation of the yen—currency moves matter when roughly 80% of revenue comes from overseas. And additional tariffs being discussed in the U.S. have not been factored in; if implemented, Kubota has indicated there is a possibility of a profit decrease of up to JPY10 billion.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Kubota’s 135-year journey is a masterclass in how an industrial company can keep reinventing itself without losing its identity. If you strip away the product names and the geography, a handful of patterns show up again and again.

Lesson 1: Infrastructure as Foundation

Kubota’s start in water pipes wasn’t just “the first product.” It was the training ground. When you’re making components for public infrastructure, there’s no room for sloppy tolerances or “good enough.” That manufacturing discipline became portable—it carried forward into engines, tractors, and construction equipment.

Just as powerful were the early customer relationships. Supplying municipal water systems meant working closely with governments on long timelines and essential budgets. Those stable, recurring relationships helped fund the next wave of expansion. And underneath it all was the mission: build what society needs. That sense of purpose wasn’t marketing copy; it was the company’s operating system.

Lesson 2: Diversify Through Adjacent Technologies

Kubota didn’t diversify by throwing darts. Its growth followed a chain of adjacency: iron casting to pipes, pipes to engines, engines to tractors, tractors to construction equipment. Each step reused skills, supply chains, and engineering instincts from the previous one.

That’s why Kubota could expand while staying coherent. Even the rare detours—like the 1990s experiment with graphics chips—didn’t turn into a permanent identity crisis. When the fit wasn’t right, it pulled back and returned to what it could compound.

Lesson 3: Crisis as Transformation Catalyst

The asbestos scandal that became the Kubota Shock could have permanently defined the company in the public mind. Instead, Kubota’s response—apologies, compensation programs, and a willingness to be held accountable—became a turning point.

That doesn’t erase the tragedy. But it does show something important: companies that survive existential crises often do so by getting brutally clear about their values. Comfort rarely forces that kind of clarity. Catastrophe does.

Lesson 4: Acquire to Accelerate, Not Replace

Kubota’s M&A playbook has been unusually disciplined. With Kverneland and Great Plains, it didn’t treat acquisition like assimilation. It preserved brand identities, kept expertise close to where it was created, and emphasized continuity instead of corporate takeover theater.

As one Great Plains leader put it: “Great Plains is still Great Plains. We are still the same company with the same mission statement, the same roots we have always had. And we have a commitment to stay that way.” That posture reduces the integration risk that kills so many deals—and it protects what you actually bought in the first place.

Lesson 5: Think in Centuries, Not Quarters

A company that’s been operating for more than a century tends to invest differently. Mr. Yuichi Kitao, President and Representative Director of Kubota Corporation, tied that long view back to the founder’s principles: “On the occasion of our 130th anniversary, it would be amiss of us to not remind ourselves of our founding principles and that ‘there will be no growth without innovation.’”

Kubota’s advantage isn’t just that it plans for the next year. It’s that it’s willing to build capabilities—technology, dealer networks, trust with governments, manufacturing excellence—that can take decades to mature. Over time, those investments don’t just pay off. They compound.

XI. Bull Case, Bear Case & Competitive Analysis

The Bull Case

If you want the “why this could keep working for a long time” argument for Kubota, it starts with durable advantages that stack on top of each other.

In compact tractors and mini excavators, Kubota benefits from scale economies. When you’re building at high volume, you get cost advantages that smaller competitors struggle to match. And Kubota’s scale isn’t just in finished machines—it’s in engines. The company makes more than 2,000 engine models, which helps with purchasing leverage and spreads R&D costs across a huge base.

Then there’s the dealer network, which functions like a flywheel. More dealers means service is closer and easier. That convenience matters a lot in agriculture and construction, where downtime is expensive and the nearest technician can be the difference between a minor issue and a ruined week. Better service availability drives more sales, which makes the brand more attractive to dealers, which expands the network again.

Once customers are in, switching costs do the rest. A farmer or contractor who standardizes on Kubota equipment builds familiarity, training, and working relationships with local dealers. And as Kubota expands its lineup of matched tractors and implements, the ecosystem becomes stickier—switching brands can mean switching attachments, learning new interfaces, and rebuilding the whole support setup.

And of course, there’s brand. The orange paint is recognizable for a reason. Decades of reliability in compact equipment have made Kubota a default choice for many buyers, supporting loyalty and, in some cases, price premiums.

The bull case, though, isn’t just “they’re good at what they already do.” It’s that Kubota is early, credible, and shipping product in the next wave: autonomous and electric agricultural machinery. By 2024, around 700 machines from the AgriRobo series had shipped and were working on farms across Japan. If labor shortages keep worsening and environmental requirements keep tightening, “smart agriculture” shifts from optional to necessary—and Kubota is positioned to capture outsized value as the market turns.

There’s also the India upside through Escorts Kubota, which gives Kubota exposure to the world’s largest tractor market with local manufacturing and distribution already in place. The Yamuna Expressway Industrial Development Authority (YEIDA) has allotted around 200 acres to Escorts Kubota Limited for a planned ₹4,500 crore manufacturing unit. Formed in 2019 as a partnership between India’s Escorts and Japan’s Kubota, the venture is moving ahead with plans to produce tractors, engines, farm machinery, and construction equipment.

The Bear Case

Now the “what could go wrong” version. Look at Kubota through Porter’s Five Forces and the weak points become clearer.

The threat of new entrants is low in traditional heavy equipment—this is capital-intensive, regulated, and distribution-heavy. But autonomy changes the shape of the battlefield. If software, sensors, and AI become the primary differentiators, disruption could come from unexpected places: technology companies, automotive players, or well-funded startups that don’t carry legacy product lines.

Buyers have leverage too, especially at the top end. Large agricultural operations and fleet buyers can negotiate hard, and price competition in compact tractors has intensified as Korean and Indian manufacturers push further into the segment.

Supplier power shows up most clearly in the high-horsepower category. Kubota’s use of Cummins engines in the M8 series—rather than Kubota’s own engines—highlights that at the upper end of the lineup, Kubota can face real dependency on key partners.

There are also substitutes and shifts in the ownership model. Electrification could, over time, commoditize parts of the powertrain and reduce differentiation. And if rental or sharing models expand, that can reduce the total addressable market for outright ownership.

Finally, competitive rivalry is intense and well-funded. John Deere’s scale—and its R&D investment in precision agriculture and autonomy—creates constant pressure. CNH Industrial and AGCO are investing heavily too, and they’re not standing still in the same “connected farm” direction.

On the nearer-term operational side, Kubota faces a compact tractor market that is expected to be sluggish, with continued severe price competition. The North American residential market, a key driver of compact equipment demand, is also sensitive to interest rates and housing conditions.

And then there’s currency. Kubota earns nearly 80% of revenue overseas but reports in yen. When the yen strengthens, reported margins and earnings can get squeezed even if the underlying business holds steady.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking Kubota’s trajectory, two metrics tell you a lot, fast:

-

North American Compact Tractor Market Share: The compact segment accounts for about 65% of U.S. tractor unit sales, and Kubota holds around a 25% share. If that number meaningfully moves, it’s a signal that something fundamental is changing—product competitiveness, dealer strength, or pricing pressure. Dealer inventory levels and retail sales data from the Association of Equipment Manufacturers can offer early clues.

-

Overseas Revenue Ratio and Operating Margin: With about 79% of revenue coming from outside Japan, the mix matters—but so do the margins attached to it. If the overseas ratio rises while margins stay stable, that’s healthy expansion with pricing discipline. If the overseas ratio rises while margins fall, it can indicate heavier competition and price concessions.

XII. Conclusion: The Next 135 Years

In Kubota’s corporate archives, there’s a photograph from around 1890: a young Gonshiro Kubota standing with his family outside the modest workshop where it all began. There’s no way he could have pictured what that tiny casting works—started with 100 yen and a furnace in a rented corner—would become: a global company whose machines and infrastructure touch everyday life for millions, from Japanese rice farmers to American acreage owners to communities drinking water delivered through Kubota-built systems.

Kubota made it through world wars, economic shocks, and a reputational crisis that became national news. And it didn’t survive by standing still. It kept moving—pipes to engines, engines to tractors, tractors to compact construction equipment, and now into autonomy, robotics, and AI. The products changed. The mission stayed remarkably consistent: build things that matter, and build them for the benefit of society.

As Kubota moves deeper into its second century, the pressures ahead are real. Climate change threatens crop yields. Farming populations are aging and shrinking. Competition to own the future of autonomous equipment is heating up. And geopolitics keeps injecting uncertainty into global supply chains.

But these pressures are also the opening. The technologies Kubota is pushing—autonomous tractors, electrification and hydrogen power, AI-enabled precision agriculture—are aimed straight at the world’s biggest constraint: producing more food with fewer hands and a lighter footprint. And the company’s long-earned expertise in water and environmental infrastructure positions it to keep doing what it has done since the beginning: help communities build healthier, more resilient systems.

For investors, the real question is simple: can Kubota keep adapting the way it always has? Its history argues yes—but the next era won’t be won on legacy alone. It will take the same ingredients that propelled a 19-year-old founder from a tenement workshop to industrial scale: relentless innovation, patience to build for the long term, and a stubborn commitment to solving essential problems.

The orange tractors will keep working across fields and properties around the world. The pipes will keep carrying water beneath cities. And back in the workshops and labs, Kubota’s engineers will keep trying to earn the next chapter—one that began 135 years ago with a teenager, a furnace, and an idea that manufacturing should serve society.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music