SMC Corporation: The Invisible Giant of Factory Automation

Introduction: The Hidden Infrastructure of the Modern World

Picture a modern factory floor: a semiconductor fab in Taiwan, an EV battery line in Germany, a pharmaceutical packaging plant in Indiana. Your eyes go to the robots, the conveyors, the precision stages sliding back and forth with eerie smoothness.

But the real muscle behind a surprising amount of that motion is something you can’t see: compressed air. It pushes, grips, turns, lifts. It does the unglamorous work, endlessly, reliably, on every shift.

And if you traced the tubing back to the parts that actually make that air useful—the valves, actuators, regulators, fittings—there’s a good chance you’d find three letters stamped on the hardware: SMC.

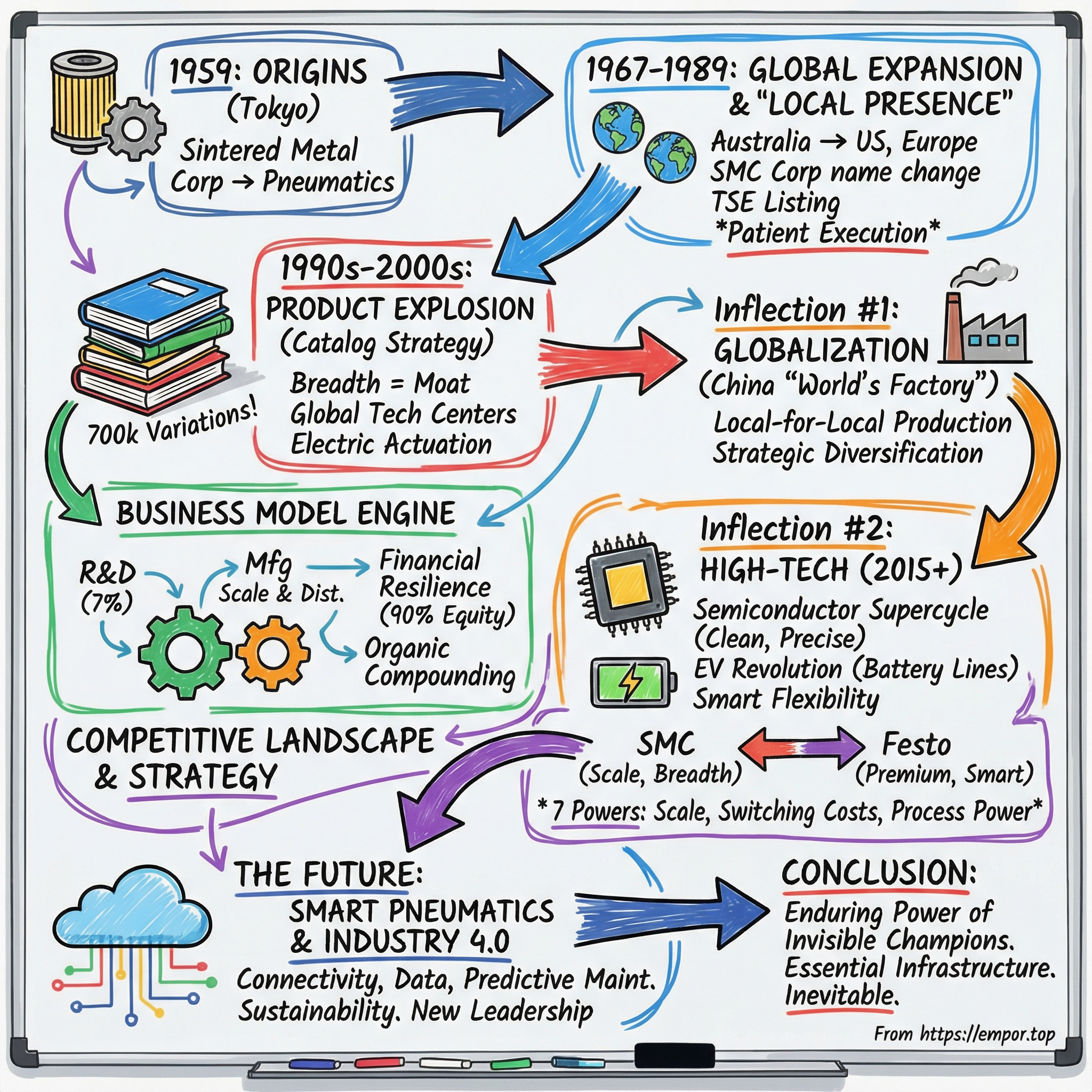

SMC Corporation is a Japanese TOPIX Large 70 company founded in 1959 as Sintered Metal Corporation. It specializes in pneumatic control engineering, the nuts-and-bolts technology that lets industrial automation function day to day. Over decades, SMC expanded from basic pneumatics into increasingly sophisticated automation solutions, and in the process it built a position that’s almost absurd for such a sprawling, competitive market: roughly 30% global share, and about 65% in Japan. In a category where being “big” often means cracking ten percent, SMC became the default choice.

Yet if you ask the average investor—or even most business people—about SMC, you’ll likely get a blank stare. This is a company with a market capitalization above $40 billion, revenue near $5.5 billion, and operations in more than 80 countries, and it still lives almost entirely outside the public imagination. How did a company that started by making air filters become the dominant force in the machinery behind modern manufacturing? And what does that journey teach us about the quiet, compounding power of “boring” B2B businesses?

The answer is a six-decade story of patient capital, relentless engineering, and a distinctly Japanese approach to building advantage: show up everywhere, serve customers locally, and never stop iterating.

SMC is a classic “hidden champion,” to use the phrase popularized by management thinker Hermann Simon: a company that dominates its niche while staying invisible to everyone except the people who design, buy, and maintain the systems that keep the world’s factories running.

Today, the SMC group operates offices in more than 80 countries, employs around 23,000 people, and offers an almost comical level of choice—around 700,000 product variations. That catalog depth isn’t trivia. It’s one of SMC’s core moats: whatever problem an automation engineer is trying to solve with air, odds are SMC already makes the exact part that fits.

This is the story of how a small Tokyo manufacturer of sintered metal filters turned itself into the undisputed leader in pneumatic automation. It’s a story about organic growth in an era obsessed with acquisitions, about engineering culture as strategy, and about why some of the most defensible businesses in the world sit in the least glamorous corners of the economy.

The Sintered Metal Origins: Japan's Post-War Industrial Rebirth (1959–1970)

In April 1959, Tokyo was still in the long shadow of the war, but the country’s industrial rebuild was already accelerating into what would become Japan’s economic miracle. In Chiyoda-ku—right in the capital’s political and commercial core—a small company was incorporated with a very specific mission: make and sell sintered metal filters and components using powder metallurgy. Its name was Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Co., Ltd. In English, it would soon trade as Sintered Metal Corporation. Eventually, it would become SMC.

The early days weren’t glamorous. When the company opened its doors, it had eight employees, most of them part-time. There wasn’t even a telephone line in the office. If they needed to make a call, they walked next door to a small print shop and borrowed theirs. But those scrappy logistics hid something more important: the temperament that would define SMC for decades. Founder Yoshiyuki Takada wasn’t building a flashy brand. He was building capability.

Sintered metal parts were obscure to the public, but essential to industry. By compacting metal powders and heating them without fully melting them, you could create components with controlled porosity and consistent strength—perfect for filtration, and broadly useful in heavy industry. As Japan’s automotive and machinery sectors ramped back up, Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo found real demand for durable, precisely made components. More importantly, it began building a reputation for doing the uncelebrated work well: materials, tolerances, repeatability.

Then, in 1961—just two years in—the company made the move that turned it from a niche supplier into the beginning of a platform. It launched its first range of pneumatic components and air line equipment. This wasn’t a simple adjacent product. It was a strategic shift toward the infrastructure of automation.

Pneumatics made sense once you saw what factories were becoming. Compressed air is often called the “fourth utility,” after electricity, water, and gas. It’s safe, it can operate in hazardous environments, it’s clean compared to hydraulics, and it delivers a lot of force for its size. In the 1960s, as Japanese manufacturing modernized and scaled, the demand for reliable pneumatic components surged—and SMC was now pointed directly at that wave.

From there, the product scope widened steadily. By 1964, the company was building out automatic control tools that helped factories run more efficiently. And by 1970, it had started producing actuators—air cylinders—moving closer to the parts that didn’t just manage air, but turned it into motion.

By the end of its first decade, SMC hadn’t just found a market. It had discovered its operating system: precision over hype, reliability over novelty, and constant iteration over big-bang reinvention. It was building something more durable than any one product line—an engineering culture designed to compound.

That foundation—manufacturing know-how, customer intimacy, and an almost stubborn commitment to quality—would matter even more in the next chapter, when SMC started looking beyond Japan.

Going Global: The Methodical International Expansion (1967–1989)

If SMC’s first decade proved it could build great pneumatic components, the next twenty years asked a harder question: could it do that outside Japan?

SMC took its first real step abroad in 1967, setting up an overseas subsidiary in Australia: SMC Pneumatics (Australia) Pty. Ltd. It began through capital participation, and by 1980 it became wholly owned. This wasn’t a splashy move into the biggest market available. It was SMC doing what SMC does: picking a manageable proving ground, learning how to operate across distance and culture, and building confidence before moving on.

Choosing Australia was telling. Instead of rushing straight into the U.S. or Europe, SMC started in a smaller, growing market in the Asia-Pacific region—one where the company could test its playbook with fewer sharp edges. That playbook would become the defining feature of SMC’s international rise.

Over the next decade, the footprint widened. SMC established SMC Manufacturing (Singapore) Pte. Ltd. in 1974. It entered the U.S. with SMC Corporation of America in 1977. Europe followed fast: SMC Pneumatics (U.K.) Ltd. and SMC Pneumatik GmbH launched in 1978, with further expansion in the early 1980s, including SMC Italia S.p.A. in 1981, plus operations in the Netherlands and Belgium that same year, and in Switzerland in 1976.

But the important part wasn’t the dates. It was the philosophy.

SMC didn’t treat overseas markets like places to ship boxes from Japan. It built real local presence: local inventory, local technical support, and local relationships. Decades before “local-for-local” became a management catchphrase, SMC was already executing it. And in industrial components, that difference is everything.

Imagine you’re a procurement manager at an automotive plant in Ohio in the 1980s. A pneumatic cylinder fails on a critical line. Downtime is brutally expensive, and “we’ll ship a replacement from Japan” is not a plan. The supplier that can pull from nearby inventory and send an English-speaking engineer who understands how American plants actually run doesn’t just win the order—they become the default.

This was also the period when the company’s identity caught up with what it had become. In the mid-1980s, Sintered Metal Corporation amended its name to SMC Corporation, a change tied to preparations for a public quotation. It wasn’t cosmetic. It was a signal that the old, narrow description—filters and sintered metal—no longer fit. SMC was now building a broader automation business, and it wanted the name to match.

Then came another milestone: listing on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1989, right at the height of Japan’s asset bubble. In hindsight, it’s the kind of timing that makes you nervous. But SMC’s behavior around the capital markets was consistent with everything we’ve seen so far. It didn’t use a hot market as an excuse to chase aggressive acquisitions or financial engineering. It kept doing what it always did—expand methodically, invest in engineering, and grow organically.

As Pascal Borusiak observed, “the topic of shareholder value” effectively didn’t exist in SMC’s linguistic jargon, despite being a listed company. That mindset—so out of sync with Western quarterly obsession—would matter a lot in the years ahead. When Japan entered its long, grinding “lost decade,” many companies were dragged down by bubble-era overreach. SMC, built on patient execution instead of big bets, had a sturdier foundation.

By the end of the 1980s, SMC had gone from a small Tokyo maker of obscure components to a genuinely global enterprise. And somehow, it had done it without losing what made it work in the first place: an engineering-first culture, an operator’s patience, and a willingness to win market by market, plant by plant, one dependable part at a time.

The Product Explosion: Engineering Breadth as Competitive Moat (1990s–2000s)

By the 1990s, SMC had already proven it could go global. The next move was even more decisive: it turned “pneumatic components” into a platform. This is where SMC’s advantage stopped being about any single valve or cylinder—and started being about sheer, almost impossible-to-copy breadth.

Inside SMC, this became the catalog strategy. On paper, it sounds like a product manager’s fever dream: roughly 12,000 basic models that fan out into around 700,000 variations. But in factories, that breadth is less about bragging rights and more about reducing friction. The hard part of automation isn’t buying a part. It’s choosing the right part, qualifying it, integrating it, documenting it, and making sure it will still be available when you need to service the line years later.

So when an engineer has a new machine to design or a broken line to get running again, the supplier who can say, “Yes, we have the exact configuration you need—and we can help you spec it correctly,” doesn’t just win a purchase order. They win the standard.

This product explosion wasn’t limited to classic pneumatics. SMC continued to expand its range of directional control valves, actuators, sensors, and air line equipment—but it also leaned into electric actuation as it emerged as a viable alternative in certain use cases. Instead of treating electric actuators as a threat to pneumatics, SMC treated them as another knob the customer could turn. Pneumatic, electric, or some hybrid of both—SMC wanted to be the vendor you could keep specifying either way.

By 2000, the results showed up in the numbers: consolidated sales exceeded ¥200 billion, a milestone that reflected not just market growth, but SMC’s growing role as the default supplier for automation builders. That same period also saw launches like the LE Series electric actuator, a signal that SMC could expand beyond its pneumatic roots without losing its reputation for reliability and precision.

The machinery behind this expansion was engineering. And SMC didn’t try to power it from a single headquarters in Japan. It built technical development centers across regions so teams could sit closer to customers, respond faster to local requirements, and design for real-world differences in standards and applications. The effect was simple: product development wasn’t happening in isolation. It was happening alongside the people who would actually use the parts.

That commitment to engineering intensity didn’t fade with scale. SMC grew into a company with more than 500 offices in over 80 countries, around 20,000 employees, and thousands of people in frontline roles—sales staff who could get into plants, and engineers who could translate messy factory constraints into workable solutions.

And by the early 2000s, the flywheel was obvious. Customers kept choosing SMC because it could solve almost any automation problem from one catalog. That volume funded more R&D and more variations. The expanding catalog made SMC easier to standardize on. And every time a plant standardized on SMC, switching became harder—because the fastest path to the next solution was usually… another SMC part.

In November 2023, SMC signaled just how seriously it still took this advantage. The company announced plans to invest 40 billion yen by 2026 to implement a round-the-clock development model at its facilities, aiming to cut product development time in half. It also planned to expand its overseas engineering workforce by 20%, targeting more than 2,000 engineers by 2026—doubling down on the same playbook that built the moat in the first place.

Inflection Point #1: China and the Globalization of Manufacturing (2000s–2010s)

The first decade of the new millennium brought a shift that rewired global manufacturing. China became “the world’s factory,” and suddenly supply chains, production footprints, and plant design standards were being rebuilt around a new center of gravity. For SMC, it was the kind of macro wave you don’t try to predict with a press release. You prepare for it with infrastructure.

SMC’s answer was simple and consistent with everything it had done before: build where your customers build. Over time, key production facilities took shape in China and Singapore, supported by local production across the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Europe, India, South Korea, and Australia. This wasn’t about exporting more boxes from Japan. It was “local-for-local” at global scale—manufacturing, inventory, and support close enough to customers that SMC could be relied on when a line went down and minutes mattered.

China, in particular, was both an opportunity and a stress test of the strategy.

First came the multinationals. When German automotive suppliers, electronics giants, and other global manufacturers set up plants in China, they didn’t leave their expectations behind. They wanted the same reliability, the same parts availability, and the same application support they had in Europe, Japan, or the U.S. SMC’s growing footprint and reputation made it the safe, familiar choice—the supplier that could meet global standards inside a Chinese factory.

Then came the bigger prize: China’s domestic manufacturers moving up the value chain. As Chinese companies evolved from simpler production into more sophisticated automation, they needed better components—and they needed partners who could support real industrial operations, not just sell parts. SMC invested accordingly, establishing branches and production bases across major industrial regions, especially in South and East China. That local presence turned China from a “market we sell into” into a place where SMC truly operated.

One of the most important outcomes of this era was strategic diversification. Japan became a smaller share of overall revenue, settling around a quarter, while China grew to roughly a fifth and the United States to just under that. The point wasn’t the exact split. It was resilience: SMC was now anchored across the world’s three most important manufacturing economies, rather than tied to the cycle of any one.

And China wasn’t the only story. Through the 2000s and 2010s, new manufacturing hubs gained momentum across Asia—India, Vietnam, and Southeast Asia more broadly—and SMC followed its customers there too, using the same playbook: show up locally, and commit for the long term.

Europe got its own version of that commitment in 2012, when SMC inaugurated its first European Central Factory in the Czech Republic. It was a straightforward move with outsized impact: build closer to European customers, shorten lead times, and serve the region from inside the region.

By the end of this period, SMC had navigated one of the biggest shifts in industrial history since the post-war boom: the globalization of manufacturing. Plenty of companies rode that wave by chasing export volume. SMC rode it by building capability—plant by plant, region by region—so wherever factories moved, SMC already felt local.

Inflection Point #2: The Semiconductor Supercycle & EV Revolution (2015–Present)

If China tested SMC’s ability to scale with globalization, the next wave tested something harder: could a company built on “boring” pneumatics stay essential as manufacturing tilted toward the most demanding technologies on earth? The semiconductor boom and the EV revolution gave SMC a clear opening—but only if it kept evolving.

Semiconductors and pneumatics don’t sound like natural cousins until you step inside a fab. Chipmaking is a game of ruthless control: position the wafer with extreme accuracy, keep temperatures stable, and eliminate contamination so thoroughly it feels almost imaginary. In that world, motion systems still need actuators and valves—and they need them to be clean, reliable, and repeatable. That’s where SMC keeps showing up.

And SMC didn’t just lean on “classic pneumatics.” It pushed deeper into thermal management, where the requirements are just as unforgiving. Its thermo-chiller lineup became increasingly important as fabs expanded. Products like the HRZ-F series were developed specifically for semiconductor applications and carry industry-standard approvals. The HRW series handled cooling and temperature control across processes like wafer etching and cleaning—exactly the kinds of steps where drift and instability are unacceptable.

HRZ recirculating chillers were built with high-tech manufacturing in mind, conforming to SEMI equipment standards across areas like safety, environment and health, ergonomics, and voltage sag immunity. Cooling capacity spans the range most toolmakers actually need, from 1 to 10 kW.

Supporting this kind of customer also means controlling how your components are made. SMC manufactures and assembles high-purity components in an ISO 5 clean room—capabilities that matter for semiconductor equipment, and that also extend into areas like food-grade products for the food industry.

Then came the other monster demand wave: electric vehicles.

EVs are often framed as a battery story—and on factory floors, that translates into a battery-manufacturing arms race. SMC designed a wide range of products specifically for secondary battery production. Secondary batteries are rechargeable batteries, commonly used in EVs, and building them at scale requires specialized automation in harsh, finicky conditions.

Battery lines deal with lithium compounds, corrosive electrolytes, and delicate copper and aluminum foils, often in controlled low-dew-point environments. SMC’s 25A- series variations were developed with those constraints in mind: materials compatible with secondary battery applications, able to operate in low dew point conditions, and designed to eliminate copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) where possible. The point isn’t the naming. The point is that SMC wasn’t repackaging old parts—it was engineering around the real pain points of a new kind of factory.

That mindset showed up in pace, too. In 2023, SMC released 16 new products for the secondary battery industry, with additional products already in production and more in design. It’s a familiar pattern: when SMC sees a category becoming strategic, it responds the way it always has—by widening the catalog until it becomes the easiest option to standardize on.

The business results reflected the tailwinds. In 2024, SMC recorded revenue growth of 8.2%, with profit up 9.5%, suggesting it was not only benefiting from demand but also operating efficiently as it scaled.

And while chips and batteries were driving growth, SMC also pushed into the next layer of industrial value: making components smarter.

Industry 4.0 and smart factories don’t eliminate valves and actuators—they change the expectations around them. Customers want visibility, data, and the ability to predict failures before they become downtime. SMC leaned into that shift with its Smart Flexibility approach, built around helping customers make machines “Industry 4.0-proof” by combining automation expertise with close, hands-on collaboration.

Under its Smart Field Analytics offering, SMC aimed to provide granular operational data that helps customers pursue sustainability, cost savings, and efficiency. The practical promise is straightforward: enable predictive maintenance across the floor, and reduce the risk of unplanned downtime that can ripple into missed shipments and disrupted production.

Taken together, this wasn’t a departure from SMC’s identity—it was an extension of it. The company that built a moat by offering every variation of the right part was now adding a new dimension: not just the component you need, but the insight layer that helps you run it better.

Inflection Point #3: IP Wars and Defending Market Position

Market dominance has a way of attracting two things: serious challengers, and copycats. And in a components business—where a tiny spec can be the difference between a smooth-running line and a costly shutdown—those battles often show up as fights over claims, labeling, and intellectual property.

SMC’s most visible public clash in recent years was with AirTAC. On December 25, 2020, SMC filed a case against AirTAC in the Tokyo District Court seeking damages and other remedies. SMC argued that AirTAC had used misleading indications of quality—specifically, incorrect information about the effective cross-section area and Cv value for some of AirTAC’s solenoid valves—and that this constituted unfair competition.

AirTAC International Group, founded in Taiwan in 1988 and headquartered in Ningbo, is a major global supplier of pneumatic equipment, spanning actuators, control components, air preparation products, and accessories. In other words: exactly the territory SMC dominates.

The dispute is revealing because it gets at the recurring problem for premium industrial suppliers. When low-cost competitors lean on aggressive pricing, they can also be tempted to lean on aggressive marketing—performance claims that look great on paper, even if they don’t hold up in practice.

In the AirTAC case, the court found that the advertising at issue was inaccurate and that it amounted to an act of unfair competition by misleading customers as to quality. AirTAC had already taken certain measures, but SMC’s view was that obtaining a formal court decision around unfair advertising and product labeling mattered—not just for SMC, but to protect customers and reinforce a fair competitive environment in the market.

SMC’s courtroom track record wasn’t limited to Asia, either. In the U.S., the International Trade Commission ruled against a Colorado-based company that claimed SMC Corporation and SMC Corporation of America violated 19 U.S.C. Section 1337 through unfair practices in import trade. On March 8, 2011, the ITC reversed an earlier administrative law judge decision, found a Norgren, Inc. patent invalid as obvious, and terminated the investigation with a finding of no violation.

Zoom out, and the takeaway isn’t that SMC “wins lawsuits.” It’s what these disputes say about the real moat. Yes, there are patents. Yes, there are legal defenses. But the harder-to-copy advantage is the sixty-plus years of engineering knowledge—embedded in generations of employee expertise and in the operational ability to design, manufacture, and support a catalog that reaches into the hundreds of thousands of variations.

And when competition heats up, SMC doesn’t rely on lawyers alone. It relies on motion. Continuous innovation and sustained R&D investment mean competitors are aiming at a moving target. By the time someone copies what SMC ships today, SMC is already iterating toward what customers will need next.

The Competitive Landscape: SMC vs. The World

After the lawsuits and the copycats, the obvious next question is: who’s actually across the table from SMC in the global market?

SMC competes with a familiar mix of industrial heavyweights and niche specialists—companies like Festo, Keyence, and intelliSAW. On Comparably, SMC ranks 1st versus its competitors in Employee Net Promoter Score, a small but telling indicator of internal health in a business where execution compounds over decades.

Zooming out to the market leaders, the top tier in pneumatic components is generally some combination of SMC, Festo, Parker Hannifin, Emerson Electric, and Bosch Rexroth. Together, they account for roughly 40% of global share—meaning even the “giants” are fighting in a world that’s still fragmented, with lots of smaller players below.

The most instructive head-to-head is SMC versus Festo: Japan’s scale machine versus Germany’s premium engineer.

Festo is also family-owned, and it’s SMC’s closest true global peer. It supplies pneumatic and electrical automation to roughly 300,000 customers across factory and process automation, spanning more than 35 industries. With about 20,600 employees, more than 250 branch offices, and operations in around 60 countries, Festo reported turnover of roughly €3.45 billion in 2024.

Broadly speaking, their geographic centers of gravity are different. SMC has the edge in Asia—especially Japan and China—while Festo’s historical stronghold is Europe, with a meaningful presence in North America as well.

Festo’s leadership has been blunt about how it sees the contrast. As Festo’s CEO told EE Times: “The difference between SMC and Festo is like the difference between black and white. SMC has a good price and reasonable quality even at massive volumes.” For years, that was the story: SMC’s volumes, driven by competitive pricing, kept it ahead. Festo’s current claim is that it’s narrowing the gap by leaning harder into “smarter” automation—robotics, programmable logic controllers, and broader assembly-line systems.

That framing is, of course, self-serving. But it highlights a real strategic split.

Festo has deliberately staked out the premium, innovation-forward posture: controlled pneumatics, AI integration, and smart manufacturing. It also backs that story with unusually high R&D intensity. Last year, Festo invested 8.8% of turnover in research and development (up from 7.7% the prior year), expanding its portfolio across electric and pneumatic automation, control technology, and digital solutions including software and AI.

SMC’s counterpunch isn’t a slogan—it’s structure. SMC brings superior scale, a broader catalog, and pricing power that comes from sheer volume and execution. It sits at around 30% global market share, and it continues to invest heavily in R&D as well—about 7% of revenue—while using its breadth and availability to stay the default choice for engineers who need the right part quickly and reliably.

Then there’s Parker Hannifin, which creates a different kind of competitive pressure. Parker is a diversified motion and control conglomerate, spanning hydraulics, filtration, aerospace, engineered materials, and pneumatics. That breadth creates scale, but it can also dilute focus. SMC’s narrower concentration—pneumatics and closely related automation—lets it go deeper in the domain and build a catalog and support model that’s hard to match when pneumatics is only one business line among many.

Finally, the low-cost challengers. Emerging Asian competitors, especially AirTAC, compete primarily on price. They’ve gained share in cost-sensitive applications and in developing markets. But for higher-end customers—where uptime matters, qualification cycles are painful, and a component failure can cost far more than the component itself—SMC’s quality reputation, catalog depth, and global technical support network tend to win out.

Business Model Deep Dive: The Anatomy of Market Dominance

SMC’s business model is worth slowing down for, because it’s a masterclass in how you build a durable edge in industrial components—and keep it.

Start with the engine: R&D. SMC has consistently invested about 7% of revenue into research and development. That’s a big number for a components company, and it puts SMC in the same weight class as best-in-industry peers like Festo. More importantly, the goal isn’t just to polish existing parts. This is what funds expansions into new product categories and new technologies—so SMC can keep meeting customers where manufacturing is going, not where it used to be.

Then there’s the system that turns that engineering into market share: manufacturing and distribution. SMC built a global engineering network, with technical facilities not only in Japan, but also in the United States, Europe, and China. On the commercial side, it has roughly 400 marketing and sales offices across 81 countries. In a business where downtime is the enemy, that footprint is a product in itself. It means inventory nearby. It means support in the local language. It means being able to respond when a line is down and someone needs an answer now, not after a week of emails across time zones.

Financially, SMC plays a different game than most Western industrial companies. It sits on an unusually strong balance sheet—around 90% equity capital—which gives it real self-funded flexibility. If it needs to double or triple production lines, it can move quickly with its own resources. That kind of stability supports long planning cycles and steady investment through downturns. It’s a fortress balance sheet built from decades of retained earnings and minimal debt, and it fits neatly with the Japanese preference for resilience over leverage.

All of that shows up in the margin profile. With global scale driving manufacturing efficiency, a premium reputation supporting pricing discipline, and direct relationships that reduce reliance on third-party distribution, SMC generates operating margins that most component makers can only dream about.

But the most revealing part of the model might be what SMC hasn’t done: acquisitions.

In an industry where competitors like Parker Hannifin have used M&A as a primary growth lever, SMC has largely stayed organic. It’s a global corporation that still carries the culture of a family business—deliberate, engineering-led, and built for the long term. That discipline avoids the integration messes, cultural collisions, and expensive write-offs that so often come with industrial consolidation. And over decades, that “boring” choice has turned out to be one of SMC’s most powerful advantages.

Strategic Framework Analysis: Why SMC Wins

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers is a useful lens here, because it forces you to answer the only question that matters: what advantages does SMC have that competitors can’t simply copy by trying harder?

Start with Scale Economies. SMC’s roughly 30% global market share isn’t just a leaderboard stat—it changes the physics of the business. Pneumatic and automation components come with big fixed costs: tooling, precision manufacturing, quality systems, and the engineering effort to design and validate products that won’t fail on a production line. When you can spread those costs across enormous global volume, you can price competitively, invest more, and still earn great returns. Smaller players can’t match that combination for long.

Then there are Switching Costs, and they’re sneaky. On the surface, a valve is a valve. In reality, once a factory standardizes on a supplier, it accumulates an entire layer of hidden lock-in: engineers trained on a specific catalog, parts lists built into machine designs, maintenance teams stocked with spares, and local support relationships that can get a line back up fast. For high-stakes applications, switching isn’t just “find a new part.” It’s qualification, testing, documentation, and risk—exactly the sort of pain customers avoid unless they have a compelling reason.

Counter-Positioning shows up in how SMC has grown. SMC’s dominance came largely through organic expansion—patient, engineering-led compounding. For acquisition-driven industrial conglomerates, copying that model is hard in a very specific way: it would require changing incentives, time horizons, and operating culture. It’s not that they can’t invest in engineering—it’s that doing so at SMC’s cadence often conflicts with the expectations that come with quarterly targets and M&A playbooks. SMC’s founding-family influence and Japanese corporate culture make that long-term posture easier to sustain.

Finally, Process Power is the quiet killer. Making one great component is hard. Making an ecosystem of them—hundreds of thousands of variations—reliably, repeatably, and at global scale is a different game. That capability is the accumulation of decades: continuous improvement, manufacturing routines, quality discipline, and institutional knowledge embedded in people and systems. You can’t buy that off the shelf, and you can’t replicate it quickly, no matter how much money you throw at it.

Porter’s Five Forces tells a similar story, just from the outside-in.

The threat of new entrants is low. The catalog breadth alone is a wall, and the capital required to build global manufacturing and support infrastructure makes it worse. Add the stickiness of customer relationships, and “new entrant” becomes an uphill battle before you even ship your first product.

Supplier power is relatively contained because SMC’s key inputs—aluminum, steel, plastics—are largely commodities. They matter, but they aren’t rare, and SMC can diversify sourcing to reduce disruption risk.

Buyer power is limited by fragmentation and by reality: these components are small on the bill of materials, but huge in their impact on uptime. Customers negotiate, of course, but they don’t want to gamble with a production line to save a little money.

Substitutes do exist, especially electric actuation in certain use cases. But SMC has taken the obvious hedge: sell both, and let customers choose the right tool for the job.

Rivalry is real—Festo, Parker, and others are formidable. But at the top end of the market, competition tends to be about differentiation, reliability, and support, not pure price warfare. And that plays directly into the strengths SMC has spent decades compounding.

The Future: Industry 4.0, Smart Pneumatics, and the Next Frontier

SMC’s future strategy isn’t about abandoning pneumatics. It’s about making pneumatics feel as modern as the factories they power.

That’s where smart pneumatics comes in. The basic idea is simple: take the valves, actuators, and air preparation systems that already run across factory floors, and layer in sensors, connectivity, and analytics. Suddenly, components don’t just move air—they generate real-time operational data. And for manufacturers, that data is valuable for three very practical reasons: reducing energy waste, minimizing downtime, and enabling predictive maintenance before a small issue becomes a line-stopping failure. As sustainability has moved from a nice-to-have to a board-level priority, energy-efficient smart pneumatics has become an increasingly important part of the automation toolkit.

Customer expectations are shifting accordingly. Buyers no longer just ask, “Does it work?” They ask, “Can it be monitored? Can it be controlled digitally? Can it plug cleanly into our smart factory stack?” To meet those demands, pneumatic systems need built-in intelligence—sensors, connectivity, and standardized interfaces like IO-Link that let components talk to the rest of the machine and report what’s happening in real time.

The sustainability story fits neatly with how SMC already thinks about product design. Smaller, lighter components use less raw material, take less energy to manufacture, and often consume less energy in operation once installed on a machine. SMC has increasingly framed that as a core benefit: helping customers cut emissions while also improving efficiency and lowering operating costs.

All of this ladders up to an unusually clear ambition. By expanding global market share through what it sees as its “comprehensive strengths,” SMC has stated a goal of becoming the world’s No. 1 automatic control equipment manufacturer and reaching sales of 1 trillion yen—about $7 billion at current exchange rates. It’s a big target, and hitting it would require both continued share gains and a growing overall automation market.

Geography is a major part of that runway. Emerging industrial economies still offer room to expand, and the Asia-Pacific region remains the center of gravity for global manufacturing. In 2024, Asia Pacific accounted for 48.3% of the global pneumatic components market, driven by its vast manufacturing base, rapid automation adoption, and government-backed smart factory initiatives. China, in particular, has been a force multiplier: it accounts for over 30% of global industrial robot installations, and each robot typically uses on the order of a couple dozen pneumatic components. In other words, as factories add robots, the “invisible” layers of automation—air systems and the parts that control them—often scale right alongside.

Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case for SMC starts with a simple observation: it sits in a piece of the industrial stack that doesn’t go away. Factories can change what they make—chips, cars, medicines—but they still need reliable motion, control, and repeatability. SMC’s roughly 30% global share, and its even stronger position in Japan, is the result of advantages that have been accumulating for decades: scale economies, an unmatched catalog, deep customer relationships, and an engineering culture that keeps compounding instead of chasing shortcuts.

The second pillar is demand. Automation keeps moving forward, not backward, as labor gets more expensive and customers demand higher quality and tighter tolerances. On top of that are two waves that have been particularly good to SMC. The first is semiconductors: new fabrication capacity requires a huge amount of supporting equipment, and that equipment needs clean, dependable pneumatic infrastructure. The second is EVs—especially the battery-manufacturing buildout—where SMC has already invested in specialized components designed for the realities of secondary battery production.

Then there’s the global machine SMC has built to serve all of this. Operating in more than 80 countries isn’t just a map statistic; it’s the mechanism that makes SMC “feel local” to customers almost anywhere. Close collaboration, local technical support, and the ability to adapt products to real-world plant needs are exactly what turn a supplier into a default standard.

Finally, there’s financial resilience. With a balance sheet built on near-90% equity capital, SMC can keep funding organic expansion and R&D, absorb downturns, and invest through the cycle without being forced into painful decisions by lenders or capital markets.

The Bear Case is real too—and it mostly comes down to exposure, cycles, and succession.

Start with geopolitics. China is an important market for SMC, at roughly a fifth of revenue, and that creates a meaningful vulnerability if tensions escalate between China and Japan’s Western allies. Tariffs, trade restrictions, or broader regional instability could hit demand or disrupt operations in a way that’s difficult to offset quickly.

Competition is another pressure point. Low-cost Asian players continue to push into the category, especially where the application is more commoditized and buyers are willing to trade performance and service for price. SMC’s quality and support help protect it at the high end, but there’s always risk at the margins—particularly if “good enough” keeps improving.

Then there’s cyclicality. Industrial automation is ultimately tied to manufacturing capital expenditure, and capex gets postponed when confidence drops. Even with diversification across industries and geographies, SMC can’t fully escape the reality that customers slow down in uncertain economic periods. Over a long horizon, electric actuation is also a potential substitute in certain applications, especially where precision, programmability, and integration advantages justify the higher cost.

Currency can complicate the picture for global investors as well. A weak yen can flatter reported results, while a strengthening yen can create translation headwinds, even if the underlying business is performing well.

And finally: leadership. Yoshiyuki Takada, SMC’s founder, remained intensely involved for decades—showing up every day and making key decisions even into very old age. His son, Yoshiki Takada, spent 30 years as Managing Director in America, building SMC Corporation USA, before returning to Japan. Yoshiyuki Takada retired at 93, and he passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 20, 2024.

The founder’s passing closes a defining chapter. The transition to second-generation leadership has been smooth so far, but the bigger question is what comes next: whether SMC can preserve the distinctive culture—patient, engineering-led, relentlessly execution-focused—that built its moat in the first place, as the company moves further beyond the era of its founder.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to track whether SMC is still compounding the way it always has, there are three signals that matter most.

China revenue growth is the fastest read on two things at once: how well SMC is executing in its most important growth market, and what’s happening in the broader automation cycle inside the world’s manufacturing hub. Management commentary on order trends in China often provides the earliest hints that demand is either accelerating—or rolling over.

R&D intensity—R&D spending as a percentage of revenue—is the clearest window into whether SMC is still feeding its moat. Staying at roughly 7% signals the company is continuing to expand the catalog, iterate on core products, and push into new use cases. A meaningful dip would be a warning sign: less “build for the next decade,” more “optimize for the next quarter.”

Operating margin trends tie it all together. Margins capture pricing power, manufacturing efficiency, and the temperature of competition all in one number. SMC has long operated at a level that most industrial component companies can’t touch. If margins compress, it may point to tougher pricing, higher input costs, or more aggressive rivals. If they hold steady—or expand—it suggests SMC’s scale and product breadth are still tightening the grip.

Lessons for Investors and Founders

SMC’s six-decade climb—from a tiny sintered-filter shop to the quiet backbone of global automation—leaves a handful of lessons that are easy to miss if you only study glamorous categories.

The power of "boring" B2B: SMC lives almost entirely outside consumer awareness, yet it became one of Japan’s most valuable industrial companies by selling essential components that factories can’t function without. For investors, it’s a reminder that the most exceptional compounding machines are often hiding in unsexy niches—where reliability, distribution, and customer trust matter more than hype cycles.

Breadth as strategy: SMC’s roughly 700,000 product variations aren’t just “a big catalog.” They’re a lock-in mechanism. When customers want a one-stop supplier that can cover the weird edge cases, the custom configurations, and the next revision of the line, breadth becomes a competitive weapon that pure efficiency—or a single great product—can’t replicate.

Organic growth discipline: In a world where industrial leaders often buy their way into new categories, SMC shows the other path: patient, methodical, organic expansion. That choice helped it avoid the integration headaches, cultural collisions, and expensive write-offs that so often come with aggressive M&A—and it let the company keep its operating system intact.

Engineering culture as moat: Over decades, technical capability doesn’t just add up—it compounds. SMC’s advantage is embedded in the people who know how to solve messy real-world factory problems, the processes that can reliably produce an enormous range of variants, and the institutional muscle memory to keep improving year after year. Competitors can spend money; they can’t instantly buy that accumulation.

Patient capital advantage: Founding-family ownership, combined with a Japanese long-term orientation, gave SMC the freedom to plan in decades instead of quarters. When you’re not constantly managing to a short-term narrative, you can pursue strategies—like relentless catalog expansion and global local presence—that are harder for shorter-horizon competitors to justify.

Local-for-local wins: SMC didn’t become global by shipping boxes from Japan. It won by becoming “local” almost everywhere—inventory close by, engineers on the ground, support in the customer’s language, and manufacturing where customers build. As supply chains regionalize and uptime expectations only get stricter, that playbook looks less like a historical quirk and more like a durable advantage.

SMC’s culture shows up in external validation too. Forbes, in partnership with Statista, ranked SMC among the "World’s Best Employers 2024." That kind of recognition isn’t the point—but it’s a useful signal. In a business where knowledge and execution compound, being able to attract and keep great engineers and operators becomes its own flywheel.

What to Watch

A few forces will do most of the work in determining what SMC looks like over the next several years.

First is the semiconductor capex cycle. After the post-shortage investment surge, the industry moved into a consolidation phase. Whenever the next upcycle arrives—and however large it is—will show up quickly in SMC’s semiconductor-related business, because fabs and toolmakers don’t just buy “chips.” They buy infrastructure, equipment, and the supporting components that keep ultra-precise processes stable.

Second is EV battery manufacturing, which is turning into its own automation universe. The pace of EV adoption matters, but so does where the battery plants get built and how quickly SMC can become a standard supplier inside those new lines. If semiconductors are about extreme cleanliness and control, batteries are about scale, materials constraints, and uptime—different pain, same need for reliable automation components.

Third is the competitive chess match with Festo. Both companies are investing in smart manufacturing capabilities, but from different starting points. The open question is whether SMC’s structural advantages—scale, catalog breadth, global availability—will matter more in an Industry 4.0 world than Festo’s push to lead on “smart” innovation.

And then there’s the most human variable: post-founder governance. Yoshiki Takada has been promoting a style of communication that’s more open, more direct, and in some ways more international. For a company that lived inside traditional structures for decades, that’s a meaningful shift, and the culture of cooperation inside SMC is changing a lot right now.

Whether that evolution strengthens SMC’s edge—or slowly sandpapers down the distinctive traits that built it—will become clearer with time. The move from founder-led to professionally managed is a high-stakes passage for any family enterprise, and SMC is living through that transition in real time.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Invisible Champions

SMC represents something that’s getting harder to find in global business: market dominance built the slow way. Not through roll-up acquisitions, not through financial engineering, and not by catching a single once-in-a-generation wave early. SMC got here through decades of patient execution—showing up, iterating, and compounding advantage in a category most people never think about.

The pneumatic components industry will never be a headline business. Compressed air doesn’t have the glamour of AI, and it’s not as culturally resonant as EVs. But the irony is that both of those “future” industries still rely on very physical, very unglamorous infrastructure. Every smart factory still needs motion. Every EV battery line still needs gripping, positioning, and control. And in a surprising number of cases, those jobs are done by the same quiet cast of parts SMC has spent a lifetime perfecting.

For more than sixty-five years, SMC has stuck to a simple mission: contribute to automation and labor savings in industry. The mission isn’t poetic, but the execution has been extraordinary—engineering depth, relentless reliability, and a long-term mindset strong enough to survive cycles, competition, and shifting manufacturing geographies. If anything, SMC’s obscurity is the point. It’s a measurement of where its attention went: not toward the spotlight, but toward the factory floor.

In an era of celebrity CEOs and viral products, SMC offers a different blueprint for winning: build something essential, build it to a standard people trust, be local everywhere your customers operate, and keep doing it long enough that the advantage becomes structural. It won’t make you famous. But as SMC proves, it can make you inevitable.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music