Toyota Industries Corporation: The Forgotten Parent That Built the Toyota Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

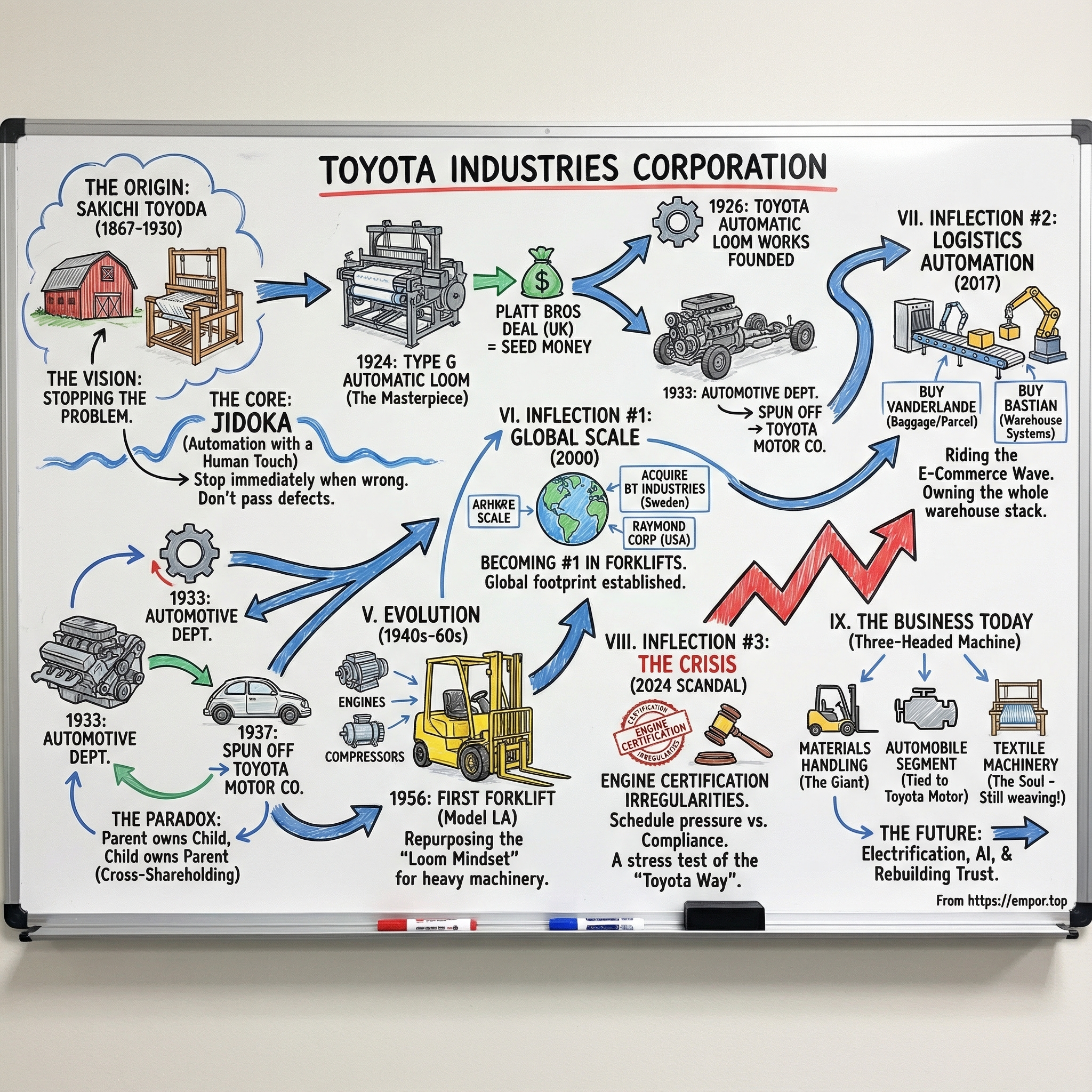

There’s a paradox hiding in plain sight inside the Toyota universe, and it starts with a fact most people miss: Toyota Industries Corporation—originally, and still as of 2024, a maker of automatic looms—is the company Toyota Motor Corporation came from. And along the way, this same “loom company” became the world’s largest forklift manufacturer by revenue.

So how does a business founded to weave fabric in rural Japan end up moving pallets in nearly every warehouse on earth—while also giving birth to one of the greatest automotive empires in history? And maybe the strangest part: why is it still making looms today?

The answer is less a straight line and more a web. Toyota Industries is one of the 13 core companies of the Toyota Group, and the ownership structure alone tells you you’re not in Kansas anymore. Toyota Industries owns 8.48% of Toyota Motor and is its largest shareholder (excluding trust revolving funds). Toyota Motor, in turn, holds 24.92% of Toyota Industries—positioned as a countermeasure against hostile mergers and acquisitions. The parent owns the child, the child owns the parent, and what looks like a corporate oddity is actually a window into how Japan built industrial power: cross-shareholding, stability, and long-term control.

But that structure is just the outer shell. Underneath is something much more important: a culture and a philosophy born on the factory floor—rooted in one inventor’s fixation on stopping problems the moment they appear and eliminating waste before it spreads. That obsession started with fabric. It later shaped manufacturing itself.

In this story, we’ll follow the thread from a barn in Shizuoka Prefecture to the automated arteries of modern commerce—warehouse automation, e-commerce fulfillment, and baggage handling in the world’s busiest airports. We’ll anchor on three big inflection points: the acquisition that vaulted Toyota Industries into the global #1 spot in forklifts, the 2017 leap into logistics automation that set it up for the e-commerce era, and the certification scandal that raised an uncomfortable question—whether the famous “Toyota Way” had been diluted somewhere between looms and engines.

II. The Inventor and His Loom: Sakichi Toyoda's Vision (1867–1930)

The Birth of Modern Japan

Start in 1867: the shogunate is collapsing, the Meiji era is about to begin, and Japan is stepping—unevenly, urgently—into the modern industrial world. In a rural corner of Shizuoka Prefecture, in what is now Kosai City, Sakichi Toyoda is born into a family that knows how to make things with their hands.

His father, Ikichi, was a farmer and a highly skilled carpenter, the kind of craftsperson neighbors called when something mattered. Sakichi learned the trade early, working as an assistant and absorbing the logic of wood, joints, and tools. But at home, he watched a different kind of work: his mother at a handloom, weaving slowly, carefully, endlessly. Where others saw a familiar rhythm, Sakichi saw a system full of friction—laborious, error-prone, and unnecessarily hard on the person doing it.

Then came a spark from outside the village. Sakichi was deeply inspired by the book "Saigoku risshi hen," published in 1870—a Japanese version of Samuel Smiles’ "Self-Help," translated by Professor Masanao Nakamura. It was a phenomenon in Meiji Japan, reportedly selling more than a million copies, and it carried a powerful idea: ordinary people could change their lives, and their country, through ingenuity and persistence. The book’s stories of inventors and textile machinery didn’t just entertain Sakichi. They gave him a direction.

Japan was also beginning to formalize the very concept of invention. The Patent Monopoly Act of April 1885 encouraged and protected new ideas. For a young man obsessed with making machines better, that mattered. It told him that building something new wasn’t merely tinkering—it was a legitimate path.

The Invention Journey

What followed was not a neat, linear march of progress. It was trial and error, stubbornness, and a willingness to look foolish for a long time.

Sakichi became fixated on the hand looms used by local farm families. If weaving could be made faster and more reliable, it would lift real burdens from real people. So he set up in a barn and went to work—building looms, breaking looms, rebuilding them again. Neighbors began to think he was strange. He didn’t care. The work wasn’t about reputation; it was about solving the problem.

In 1890, at twenty-three, Sakichi traveled to Tokyo to visit the Third National Machinery Exposition in Ueno. It was a showcase of Japanese and overseas machines—metal, gears, motion, power. He didn’t just pass through. He was so captivated that he returned day after day for nearly a month, studying mechanisms until he could explain them. In a world without formal engineering education for someone like him, this was his university.

That autumn, it finally clicked. Sakichi’s first successful invention was the Toyoda wooden hand loom. He received his first patent for it in 1891, at age twenty-four.

It was a practical breakthrough, not a flashy one. The Toyoda wooden hand loom could be operated with one hand instead of two, reduced unevenness in the fabric, and improved efficiency by roughly 40 to 50 percent. But it was still a human-powered tool. And Sakichi could see the ceiling. If he wanted a true leap, muscle wasn’t enough.

The Power Loom Breakthrough

To go further, he needed power.

After years of further experimentation and financial strain, Sakichi reached the next milestone. In 1896, he perfected the Toyoda power loom—Japan’s first power loom built of steel and wood. The shedding, picking, and beat-up motions were steam-powered, and the machine included a weft auto-stop mechanism. It was relatively inexpensive, and it dramatically improved both productivity and quality.

This mattered beyond textiles. Sakichi had done something bigger than build a better loom: he demonstrated that Japanese invention could stand alongside Western industrial technology—and that it could be protected, commercialized, and scaled.

Over his lifetime, he was awarded a total of 45 industrial property rights, including 40 patents and five utility model rights. He also filed eight Japanese patents in 19 countries outside Japan, ultimately obtaining 62 overseas patents. The pattern is the point: he wasn’t chasing a single clever idea. He was building a repeatable discipline of invention.

The Masterpiece: Type G Automatic Loom

Then, in 1924, came the machine that turned everything from “impressive” into “world-class.”

Sakichi invented the Type-G Toyoda automatic loom with non-stop shuttle change motion—the first of its kind. It could replenish thread and change shuttles without slowing down, and it stacked automation features that protected both quality and the people running it: weft break auto-stop, warp break auto-stop, and multiple devices designed around safety and reliability. It delivered top-tier performance in productivity and textile quality.

When an engineer from Platt Brothers—then the world’s leading textile machinery manufacturer—examined the Type G, he called it “the magic loom.”

And the market agreed. To produce the Type G at scale, Sakichi established Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd. in 1926. The company reportedly received orders for roughly 6,000 units in the first year. By 1937, more than 60,000 units had been produced for sale in Japan and exported to China, India, the United States, and other countries.

The Founding

On November 18, 1926, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd. was formally founded by Sakichi Toyoda to manufacture and sell the automatic looms he had invented and refined. The barn experiments had become a real enterprise.

But the most important thing Sakichi built wasn’t just a product line. It was a philosophy embedded in metal and motion: machines should protect quality, expose problems immediately, and stop when something goes wrong. Human attention should be used where it adds value—not wasted babysitting defects.

The Type G loom was the first full expression of that idea. Later, the Toyota world would give it a name. But it started here, with fabric, and with one inventor who couldn’t accept that “this is how it’s always been done.”

III. Jidoka: The Philosophy That Would Change Manufacturing

The Principle

There’s a Japanese word that captures what Sakichi Toyoda was really building: jidoka.

It’s often translated as “automation with a human touch,” but the idea is simpler—and more radical—than it sounds: when something goes wrong, the machine should stop itself. Not later. Not after a supervisor notices. Immediately. Sakichi baked that principle into his automatic looms, and it later became one of the pillars of the Toyota Production System.

You can feel the difference if you picture a textile mill before the Type G. A worker would stand watch as fabric rolled out. If a thread snapped, the loom kept running anyway, quietly producing defective cloth until someone noticed—wasting time, material, and effort.

Sakichi flipped that logic. His looms halted the instant a thread broke. Even better, they made the problem obvious, so the operator could fix the root cause rather than just restarting and hoping for the best. Quality wasn’t something you inspected at the end; it was something you designed into the process.

From there came another Toyoda hallmark: the 5 Whys. When a problem appears, don’t patch it and move on. Ask “why” again and again—five times, as the shorthand goes—until you get past symptoms and find the real source. Then change the system so it doesn’t happen again. Today, the 5 Whys sits at the center of lean problem-solving for a reason: it turns errors into information, and information into improvement.

This was more than clever machinery. It was a new relationship between humans and machines. Let machines do routine work. Let people focus on exceptions, learning, and redesign. The goal wasn’t to run faster. It was to waste less.

Sakichi is sometimes called the Japanese Thomas Edison. But that comparison almost misses what made him special. Edison built inventions. Sakichi built an operating system for invention—one that would eventually power far more than looms.

The Platt Brothers Deal: Funding the Future

Then came the moment that turned a world-class machine into something even bigger: fuel for the next industry.

The Type G automatic loom didn’t just impress Japan. It got the attention of Platt Brothers & Co., Ltd., the leading textile machinery manufacturer in England. They wanted the rights to make and sell it outside Japan.

In 1929, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works signed a patent rights transfer agreement with Platt Brothers granting production and marketing rights for the Type G in countries except Japan, China, and the United States. For Japan, this was a milestone: a foreign industrial giant paying for a Japanese invention. It was a technological vote of confidence that resonated far beyond one company.

Platt paid £100,000 for those rights—about one million yen at the time. And critically, the deal was negotiated by Sakichi’s son, Kiichiro Toyoda, who traveled to England via the United States to secure it.

That trip mattered for more than paperwork. Along the way, Kiichiro studied automobile plants and machine tools. In England, he saw what happens when an industry loses demand: even a dominant company can start to wither. In America, he saw the opposite—an automotive industry expanding so fast it was reshaping daily life.

He returned with a signed agreement and a reinforced conviction: Japan needed cars.

The Passing of the Founder

Sakichi Toyoda died in October 1930, after a lifetime devoted to invention. But before he passed, he left Kiichiro with a simple directive that read like prophecy: the coming world needed automobiles, and Kiichiro should commit himself to their development.

The timing wasn’t accidental. The proceeds from the Platt Brothers patent deal became the seed money for that push. Kiichiro had closed the agreement on December 24, 1929, and those funds would help finance the work that ultimately led to the founding of Toyota Motor Company in 1937.

And this is where the Toyota Industries story begins to show its repeating pattern: capabilities built in one domain get repurposed for something that looks, on the surface, completely different. Precision machinery becomes engine manufacturing. A loom philosophy becomes the Toyota Production System. And the willingness to bet on transformative technology becomes the constant—whether the product is fabric, forklifts, or something the world hasn’t fully named yet.

IV. The Birth of Toyota Motor: Spinning Off an Empire (1933–1937)

The Automotive Department

The leap from looms to automobiles wasn’t inevitable—and in the early 1930s, it didn’t look especially rational. Japan’s roads were being filled by foreign makers, especially Ford and General Motors, which had set up local assembly and captured much of the market. A loom manufacturer taking them on sounded like a romantic long shot.

But Kiichiro Toyoda didn’t see it as a long shot. He saw it as the next industry Japan had to master.

After traveling through Europe and the United States in 1929 to study modern manufacturing, Kiichiro began researching gasoline engines in 1930. At the same time, Japan’s government was pushing for domestic vehicle production as the war with China escalated and reliance on foreign supply looked increasingly risky. Kiichiro seized the opening. On September 1, 1933, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works established an Automotive Production Division under his leadership.

And then they did what ambitious latecomers always do: they learned by taking the leaders apart.

Kiichiro’s team reverse engineered an American car—famously, a Chevrolet—disassembling and reassembling it to understand what made it work and how it was manufactured. This wasn’t just curiosity; it was a crash course in an industry Japan didn’t yet have the industrial base to support. Automobiles demanded materials, tooling, suppliers, and process discipline on a different level than weaving.

So Kiichiro built that capability piece by piece. In June 1933, ahead of the division’s launch, he sent director Risaburo Oshima to the U.S. and Europe to buy the machine tools they had already identified as essential. He recruited anyone in Japan with credible automotive experience, including Takatoshi Kan, who joined in November 1933, and Shiguma Ikenaga, hired in March 1934.

The strategy was straightforward: get the tools, get the talent, and learn in public.

It worked fast. In 1934, the division produced its first Type A Engine. That engine went into the first Model A1 passenger car prototype in May 1935, and into the G1 truck in August of that same year.

The A1 wasn’t pretending to be a clean-sheet invention. It borrowed heavily from the best in the business: an engine based on a Chevrolet design, a chassis copied from Ford, styling inspired by Chrysler’s Airflow. Kiichiro wasn’t trying to win a beauty contest. He was trying to build a foundation.

And after the first prototypes rolled, Kiichiro drove one to his father’s grave.

It was a quiet gesture, but it captured the whole arc: the loom money had funded the engine work, the loom mindset had shaped the process, and now the son was delivering on the father’s final instruction—build automobiles for the coming world.

The Spinoff Economics

Proving you can build a vehicle is one thing. Building thousands of them, month after month, is another. By 1936, the automotive division had shown enough promise that the next step was obvious—and financially daunting.

Toyoda Automatic Loom Works was licensed under the Automotive Manufacturing Act in September 1936, which came with an obligation to establish true mass-production capability. The plan for the Koromo Plant called for output on the order of thousands of units a month. But building it required far more capital than the loom business could comfortably raise on its own.

So they did what growing companies often do when a new business line starts to dwarf the old one: they split it out.

In 1937, the automobile operation became independent as Toyota Motor Co., Ltd. The name change mattered, too. “Toyoda” literally means “fertile rice paddies,” and the company didn’t want its future tied to an image of old-fashioned farming. “Toyota” was trademarked, and the company began trading as Toyota Motor Company Ltd. on August 28, 1937. Kiichiro’s brother-in-law, Rizaburo Toyoda, became the first president, with Kiichiro as vice president. Toyoda Automatic Loom Works formally transferred automobile manufacturing to the new company on September 29.

The Koromo Plant began operations in November 1938 with roughly 5,000 employees and a production capacity of about 2,000 units per month. The physical layout took cues from large-scale American plants—but Kiichiro pushed the system in his own direction, streamlining flow and experimenting with what would evolve into just-in-time production and, eventually, the Toyota Production System.

The Legacy Relationship

The spinoff created two companies that were separate on paper but still welded together by family, philosophy, and business reality. Toyota Motor had been born out of Toyota Industries’ predecessor, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works—the machine maker Sakichi built. Both would become core pieces of the Toyota Group.

And the relationship didn’t fade with time; it hardened into structure. The cross-shareholding persists, creating one of the strangest “parent-child” dynamics in modern corporate history: Toyota Industries remains the largest shareholder in Toyota Motor, while Toyota Motor holds a large defensive stake in Toyota Industries—a circular arrangement designed to keep control stable and hostile takeovers at bay.

For outsiders, the takeaway isn’t just governance trivia. It’s a clue to how the Toyota world actually operates: not as a single monolith, but as a constellation of affiliated companies bound by ownership, supplier relationships, and shared operating principles. Toyota Industries supplies Toyota Motor with critical components like engines and compressors. Toyota Motor provides scale, demand, and the gravitational pull of the Toyota brand.

That system can be incredibly powerful—stable, long-term oriented, and operationally integrated. It can also obscure accountability in ways that, decades later, would become painfully relevant.

V. War, Reconstruction, and Diversification (1940s–1960s)

Wartime Production and Spinoffs

The 1940s forced every serious industrial company in Japan to change shape, and Toyota Industries was no exception. As the country mobilized for war, the government pushed manufacturers to redirect capacity toward military needs—and that pressure accelerated a quiet truth about Toyota Industries: it wasn’t just a loom maker anymore. It was becoming an industrial toolbox.

In 1940, the company spun off its steel production department as Toyota Steel Works Ltd. (today’s Aichi Steel Corporation). In 1944, the Obu plant began operations, producing castings that would later become foundational know-how for engines and heavy machinery. After the war, as Japan rebuilt and companies reorganized for growth, Toyota Industries’ stock was listed on the Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya Stock Exchanges in 1949.

If you zoom out, you can see an early version of the Toyota Group blueprint forming in real time: Toyota Industries would develop a capability until it became strategically important—then formalize it, scale it, and, often, spin it into a specialized company that could go deep. The group wasn’t being designed in a boardroom. It was being shaped on factory floors.

The Forklift Era Begins

Then came what would eventually become Toyota Industries’ defining business—though almost no one would have predicted it at the time.

In 1956, Toyota unveiled the Model LA 1-ton lift truck, its first forklift. A year later, Toyota Industries began producing D-type diesel engines and launched the Model LAT .85-ton towing tractor. By the end of the decade, it was producing the P-type gasoline engine as well.

On paper, forklifts might look like a side quest: a company born in textile machinery, closely linked to an automaker, suddenly building industrial trucks. But in practice, it was a straight line from what Toyota Industries already knew. Forklifts sit at the intersection of precision manufacturing, powertrains, and rugged mechanical reliability—exactly the skills Toyota Industries had been accumulating through looms, engines, castings, and vehicle-related work.

And there was something else, less visible but just as important: philosophy. Reliability isn’t a marketing slogan when your product lives in warehouses and yards, lifting tons all day. It’s process discipline. It’s designing systems that surface problems immediately and prevent defects from compounding. In other words: jidoka, translated from the loom into steel, hydraulics, and engines.

Strategic Expansion

As Japan’s economy surged through the 1960s and into the early 1970s, Toyota Industries expanded in multiple directions at once—deeper into the Toyota supply chain, and outward into adjacent product categories.

In 1971, the company started assembling the Corolla. In 1973, Toyota Industries reached an output of 3,000 units. Then in 1974, it began producing car air-conditioning compressors—one of those product lines that doesn’t sound glamorous until you realize how big it becomes once it’s everywhere.

As automotive air conditioning moved from luxury feature to baseline expectation, compressors turned into a strategic component business. Toyota Industries could serve Toyota Motor at scale, and over time that competency became valuable far beyond a single customer. It was another example of the company’s recurring pattern: master one demanding manufacturing problem, then reuse the capability in the next nearby market.

In 1986, Toyota Industries received the Deming Application Prize for quality control implementation—an external validation that the operating principles Sakichi embedded in his machines had become embedded in the organization itself.

By the late 1990s, Toyota Industries was no longer defined by a single identity. It built engines, compressors, and automotive components. It assembled vehicles for Toyota Motor. It manufactured forklifts for global markets. And yes, it still made textile machinery—not because the loom business was the engine of growth, but because Toyota Industries carried its origin story like a compass. That push and pull between continuity and reinvention set the stage for what came next: the company’s transformation from forklift maker into something much bigger—an end-to-end materials handling and automation powerhouse.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The BT Industries Acquisition – Becoming #1 in Forklifts (2000)

The Strategic Bet

By 2000, Toyota Industries had already proven it could win in forklifts. The problem was the game was changing. Materials handling was consolidating fast, especially in Europe and the U.S., and the winners were becoming the companies with the broadest lineups, the strongest dealer networks, and the ability to serve global customers consistently.

Toyota Industries had strength in Japan and in core lift trucks. But to lock in global leadership, it needed a bigger footprint in the places where it was comparatively weaker—and it needed it quickly.

So it made the defining move of its forklift era. In 2000, Toyota Industries acquired Sweden’s BT Industries, along with BT’s subsidiaries The Raymond Corporation and CESAB. Combined with Toyota Industries’ existing materials handling division, the deal created Toyota Material Handling Corporation—the largest forklift company in the world.

It was a serious swing. The offer valued BT at about SEK 7.7 billion, roughly US $890 million, and included a sizable premium over BT’s recent share price. For Toyota Industries, it was the biggest capital bet it had made up to that point. But the logic was straightforward: Toyota and BT-Rayon weren’t stepping on each other’s toes. They were complementary.

The plan, importantly, wasn’t to bulldoze what BT and Raymond had built. Toyota Industries intended to keep the U.S. brand names and sales channels for Toyota Industrial Equipment and BT-Raymond, preserving what customers already trusted while expanding what the combined company could offer.

The Integration Logic

To understand why this worked, you have to understand what BT brought.

BT was founded by Ivan Lundquist in Sweden in 1946, originally importing equipment for construction and transport. It moved into production quickly: hand pallet trucks in 1947, then electric trucks in the 1950s. In 1949, BT introduced what became a quiet revolution in European logistics: the pallet system that helped standardize how goods moved. Later known as the EUR pallet, it became the default across much of Europe.

That heritage mattered because it mapped to exactly the segments Toyota wanted to strengthen—warehouse equipment, electric trucks, and European distribution.

Then there was Raymond, which BT had acquired in 1997. Raymond’s story began much earlier, in 1922, when George Raymond, Sr. purchased a foundry in Greene, New York. Over time, Raymond became one of the key innovators in American material handling—deeply embedded with U.S. customers and dealers in the warehouse and distribution ecosystem.

The turning points came in quick succession: BT joined Toyota Industries in 2000, and in 2001 Toyota Motor Corporation’s industrial equipment sales and marketing operation was integrated into the Toyota Industries group. By 2006, the portfolio was brought together under Toyota Material Handling Group.

The integration playbook was classic Toyota Industries: keep what works, standardize what can be standardized, and use scale to improve manufacturing, service, and distribution. Brand identities stayed intact, while operations got tighter. The result was a two-brand, two-channel approach—Toyota and Raymond—that let the combined business cover more of the market without diluting either reputation. Put them together, and in North America, nobody sold more units.

Market Position Today

Two decades later, the shape of the industry makes the bet look even clearer.

The global forklift market is led by a small set of giants—Toyota Industries, KION, and Jungheinrich—together accounting for a large share of worldwide volume. Toyota Industries’ position at the top, with roughly a little under a third of the global market in recent rankings, reflects exactly what the BT deal was designed to create: a lineup that spans the basics like pallet jacks all the way up through heavy industrial trucks, backed by a dense dealer and service network across major regions.

And the broader market dynamics have only reinforced the need for scale. The industry is concentrated, with leading players controlling a majority share, and demand is being pulled by structural forces—especially the growth of e-commerce, the push for more efficient warehouse operations, and tightening emissions standards for industrial vehicles.

So the BT acquisition wasn’t just about buying revenue or crossing a geographic gap. It was about building a structural advantage: global reach, complementary brands, and a product portfolio broad enough to meet customers wherever they were. Once Toyota Industries assembled that platform, it became very hard for anyone else to replicate it.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The 2017 Logistics Automation Transformation

The Double Acquisition

If the BT Industries acquisition made Toyota Industries the world’s biggest forklift company, the moves it made in 2017 aimed at something even larger: owning the automation layer of global logistics.

That year, Toyota Industries acquired Bastian Solutions, a warehouse automation and systems integration company in North America, and Vanderlande, the Netherlands-based leader in automated material handling—best known for airport baggage systems, and increasingly important in parcel and warehouse automation.

These weren’t incremental bolt-ons. Toyota Industries agreed to buy Vanderlande for ¥140 billion—reported in the Netherlands at about US$1.3 billion, or just under €1.2 billion at the time—and closed the transaction on May 20, 2017. Earlier that year, in February, it announced the acquisition of Bastian Solutions LLC, giving Toyota Industries a front-door presence in U.S. warehouse automation to pair with its global forklift footprint.

In other words: Toyota Industries wasn’t just selling the vehicles that move pallets anymore. It was moving up the stack into the systems that choreograph the entire building.

Vanderlande's Strategic Value

Vanderlande was a different kind of asset than Toyota Industries had historically bought. Forklifts are products. Vanderlande was closer to infrastructure: complex, custom, software-heavy systems that run mission-critical operations for customers who can’t afford downtime.

Toyota Industries signed the agreement to acquire Vanderlande from its then-owner, NPM Capital, positioning the deal as a strategic expansion into automated material handling and “total solutions.” The logic was clear: Bastian strengthened North America; Vanderlande anchored airports and parcel, and brought deep capabilities in warehouse process automation across fast-growing verticals like e-commerce, food retail, and fashion.

Vanderlande’s customer penetration underscored why it mattered. By this period, 12 of Europe’s top 20 e-commerce businesses were already using Vanderlande solutions—signals of trust from operators who live and die by throughput, error rates, and uptime.

And the scale was real. In 2022, Vanderlande reported revenues of €2.200 billion, ranking it as the world’s fourth-largest materials handling systems supplier. By 2024, more than 600 airports worldwide were using Vanderlande baggage handling systems, including 17 of the 25 largest airports.

Toyota Industries didn’t just buy a company. It bought an installed base inside some of the most operationally demanding environments on earth.

The E-commerce Thesis

The bet underneath all of this was structural: logistics was becoming core infrastructure for modern commerce, and automation was becoming mandatory.

E-commerce growth had pushed warehouses and parcel networks into a new regime—higher volumes, faster delivery promises, and less tolerance for mistakes. At the same time, the work itself was getting harder to staff and harder to retain. Put those together, and advanced material handling systems stop being “nice to have.” They become the bottleneck you either fix—or you lose.

Toyota Industries said as much in its own framing: changing logistics needs, along with rapid technological progress, were expected to drive growth in automated material handling. And, as Managing Officer of Toyota Industries and the designated Chairman of Vanderlande’s Supervisory Board, Norio Wakabayashi put it, Vanderlande “complements our current offering by providing a full range of integrated automated material handling solutions,” with a strong match across sales and service networks.

The subtext: Toyota Industries had the relationships and service reach from forklifts. Vanderlande had the automation brain and systems integration. Together, they could sell the whole warehouse.

Continued Expansion

And Toyota Industries kept going.

In 2021, it formed T-Hive as its autonomous vehicle software solution, focused on automation across warehouses, manufacturing, and airport logistics using AVs. In 2022, it acquired viastore, adding intralogistics systems, intralogistics software, and supporting services. In 2024, Toyota Industries introduced a new line of AI-powered forklifts designed for aging logistics facilities.

Zoom out, and you can see the transformation. Toyota Industries was no longer “just” a forklift manufacturer—even if forklifts remained the foundation. It was assembling a full-spectrum logistics automation platform: manual equipment, semi-automated systems like conveyor-based sorting, and fully autonomous operations including mobile robots and automated storage and retrieval.

For investors, the 2017 acquisitions were a bet on two converging pressures: the surge of e-commerce and the growing challenge of warehouse labor. Both trends only intensified after 2017, reinforcing the thesis. But they also quietly raised the stakes for what came next—because when you grow by acquisition, across hardware and software, across regions and regulatory regimes, the hardest part isn’t expanding the footprint.

It’s keeping the culture, quality, and controls strong enough to deserve the trust your systems now sit inside.

VIII. Inflection Point #3: The 2024 Certification Scandal – A Crisis of Culture

The Discovery

In March 2023, the first signs of trouble surfaced. Toyota Industries (TICO) announced it would suspend domestic shipments in Japan after discovering possible regulatory violations tied to engine certifications for its forklift lineup. It acknowledged that two diesel engine models and one gasoline engine model for Toyota forklifts exceeded Japan’s emissions regulations.

At first, it read like a contained compliance issue: a small number of engines, a specific regulatory problem, a fixable mistake.

But it didn’t stay contained. An inquiry led by a special investigation committee convened by Toyota, with results released in late January 2024, suggested the problem ran wider. The committee identified additional current and previously used forklift engines that appeared to be non-compliant—turning what looked like an isolated incident into a pattern.

The Full Scope Emerges

By January 2024, the story had crossed a line that Toyota could not keep inside “industrial equipment.”

The investigation found irregularities in horsepower output testing used for certification of three diesel engine models for automobiles that Toyota had commissioned Toyota Industries to develop. Toyota Industries decided to temporarily suspend shipments of the affected engines, and Toyota Motor also temporarily suspended shipments of vehicles equipped with those engines.

An independent panel concluded Toyota Industries had falsified horsepower output tests for diesel engines used not only in seven Toyota industrial vehicles, but also in three car models. This wasn’t just about forklifts anymore. It was about the integrity of the group’s manufacturing and certification process—full stop.

The Deeper Problem

What made the moment especially damaging was the timing. Toyota Industries wasn’t the only Toyota Group company caught up in certification manipulation. The company itself acknowledged the seriousness: repeated certification irregularities at Toyota Industries, following those at Daihatsu, had “shaken the very foundations” of Toyota as an automobile manufacturer.

That Daihatsu comparison landed because it was fresh. In late 2023, Toyota-owned Daihatsu Motor was found falsifying safety test results, triggering a government order to halt production of its entire lineup. Two major group companies, two different categories of tests—one grim conclusion for the public: this was starting to look systemic.

Toyota Industries President Koichi Ito pointed to a breakdown in governance and coordination: “There was a lack of communication with Toyota Motor and insufficient coordination about testing processes and procedures that should have been followed.”

The independent investigation also suggested motive and responsibility weren’t ambiguous. The misconduct had been ongoing for years, involved multiple levels of the organization, and—according to Hiroshi Inoue, chair of the Special Investigation Committee—was done “to avoid a delay in mass production,” with “responsibility” lying with higher management.

Regulatory Response and Consequences

Regulators responded forcefully. On February 22, 2024, Toyota Industries received a correction order from Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) concerning legal violations in domestic engine certification.

MLIT also imposed an administrative sanction: revoking Type Approval for three models of engines for industrial vehicles. Toyota Industries had reported the violations to MLIT and other Japanese authorities on January 29, 2024, after which MLIT conducted on-site inspections to confirm the facts.

Then came the internal consequences. Toyota Industries announced remuneration would be returned as a form of accountability: the President and a Member of the Board would return 30 percent of monthly remuneration for six months, and Senior Executive Officers would return 20 percent of monthly remuneration for three months. The company said management and employees would focus on creating a “Culture, Mechanism, and Organization/Structure” that enables “honest and correct manufacturing,” as part of a broader revitalization effort.

The scandal also spilled into the United States. Toyota Industries, together with its U.S.-based subsidiaries Toyota Material Handling North America, Inc. and Toyota Material Handling, Inc., was named in a class-action lawsuit filed on September 22, 2024 in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, arising from a certification issue for forklift engines.

On October 31, 2025, the Toyota Industries board approved entering into a settlement agreement with the plaintiffs. The anticipated settlement payment was USD 299.5 million.

And even that didn’t close the book. Toyota Industries stated that investigations by U.S. federal authorities and California state authorities, along with discussions with those authorities, were still ongoing, and that it would continue to address the matters and disclose developments that required public announcement.

Lessons from the Crisis

At a distance, it’s tempting to reduce this to a compliance failure. But the details point to something more uncomfortable: a stress fracture in the operating system.

Toyota Industries builds engines under commission from Toyota Motor. That relationship comes with timelines, performance targets, and the constant pressure of production readiness. According to the investigation, the misconduct happened in part to avoid delays to mass production—exactly the kind of schedule pressure that, if mishandled, can turn “make the date” into an ethical hazard.

The scandal also raised a deeper question about misapplied excellence. The instincts that made Toyota legendary—continuous improvement, just-in-time thinking, an obsession with efficiency—are powerful in manufacturing. But certification is not manufacturing. Verification testing can’t be optimized like a takt time problem. Cutting corners on compliance isn’t eliminating waste; it’s introducing risk.

For investors, the overhang wasn’t only financial—though the U.S. settlement alone was meaningful, and investigations in the U.S. remained ongoing. The bigger uncertainty was trust. Toyota’s brand equity has long been intertwined with the idea of the “Toyota Way” and uncompromising quality. Once customers and regulators start questioning whether test results are real, rebuilding credibility becomes slower, harder, and far more expensive than fixing an engine.

IX. The Business Today: A Three-Headed Machine

Segment Overview

After everything we’ve covered—the looms, the forklifts, the automation land grab, and the certification crisis—Toyota Industries today is best understood as three businesses sharing one operating DNA.

Those three segments are Materials Handling Equipment, Automobile, and Textile Machinery. They behave differently, compete in different arenas, and grow on different timelines. But they’re tightly connected in one crucial way: Toyota Motor is still a major gravitational force.

Toyota Industries’ automobile and engine products are sold primarily to Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC). In FY2024, net sales to TMC accounted for 12.8% of Toyota Industries’ consolidated net sales, meaning Toyota Motor’s vehicle sales can materially influence Toyota Industries’ results. And the ownership loop still reinforces that relationship: as of March 31, 2024, TMC held 24.7% of Toyota Industries’ voting rights.

Materials Handling Equipment (The Cash Cow)

If Toyota Industries has a center of financial gravity today, it’s materials handling.

Through the Toyota Material Handling Group, Toyota Industries is a global market leader in equipment that keeps warehouses, factories, and distribution networks moving. The lineup spans traditional lift trucks and pallet jacks to automated guided vehicles, end-to-end warehouse solutions, and automation offerings—sold under brands including Toyota, Raymond, and Aichi.

What’s notable is how the segment has evolved from “selling vehicles” to selling capability. Toyota Industries has aimed to sustain leadership by pairing steady product development with partnerships and integration across its automation stack. In 2025, it launched more than 22 new electric forklift models and new lithium-ion battery solutions for next-generation trucks, positioned around efficiency and sustainability. At the same time, it increased R&D investment and continued to deepen collaboration—such as with Vanderlande—to push further into logistics automation.

The prize is large and getting larger. The global material handling equipment market was valued at USD 72.06 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 255.09 billion by 2034, reflecting an expected CAGR of 13.5% over the period. The takeaway isn’t the precision of any forecast—it’s that the world is building more logistics capacity, and more of it will be automated.

Automobile Segment

Toyota Industries’ automobile segment is the other side of the company’s modern identity: vehicle assembly, engines, and a growing set of components—especially compressors and electronic parts.

This is also the segment most entangled with Toyota Motor. In FY2025, net sales to TMC accounted for 12.9% of consolidated net sales, again underscoring how much Toyota Industries’ performance can ride on Toyota Motor’s production and sales cycles.

And this is where the certification scandal still casts a shadow. On January 29, 2024, Toyota Industries announced legal violations in domestic engine certification, and on February 22, 2024, it received a correction order from Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). The company reported its recurrence-prevention measures to MLIT on March 22, 2024, and said it has been pursuing company-wide efforts since then while seeking guidance from the ministry.

The message Toyota Industries has emphasized is a return to basics: delivering “safe and secure quality products” and continuing to contribute to society. In context, that’s not marketing copy. It’s the core promise the Toyota name is built on—and the one the scandal put at risk.

Textile Machinery (The Soul)

Textile machinery is the smallest segment today, but it’s the one that explains the whole company.

In the most recent results cited here, the segment totaled 93.3 billion yen in sales, up 9.0 billion yen, or 11%, driven mainly by increased sales of weaving and spinning machinery. Operating profit was 8.0 billion yen, up 0.2 billion yen, or 3%.

But the real significance of the segment isn’t its size. It’s what it represents. Nearly a century after Sakichi Toyoda founded the business to manufacture automatic looms, Toyota Industries still builds textile machinery. That continuity keeps a living link to the company’s origin, preserves deep expertise in precision mechanical systems, and quietly reinforces the philosophy that started it all: build quality into the machine, surface problems immediately, and never accept defects as inevitable.

X. Investment Thesis: Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case

If you want the optimistic read on Toyota Industries, it comes down to a handful of advantages that are hard to manufacture from scratch.

Global Materials Handling Leadership: Toyota Industries sits at the top of the forklift industry, with roughly 28–30% global share, and it’s used that position as a base camp to climb into logistics automation. Scale matters here. It buys you lower unit costs, more leverage in procurement, and—maybe most importantly—an installed base and service footprint that competitors can’t replicate quickly. The BT Industries and Vanderlande moves didn’t just add revenue; they stitched together a full offering, from manual lift trucks to highly automated systems.

E-commerce Tailwind: The world keeps building logistics capacity, and e-commerce keeps pushing it to modernize. Every new fulfillment center, parcel hub, and automated baggage system is a reminder that “moving goods” has become a form of infrastructure—and Toyota Industries sells the machines and systems that make that infrastructure run. This isn’t a one-cycle demand bump; it’s a structural shift that still has runway.

Electrification Opportunity: Forklifts are already moving toward electric, and Toyota Industries is positioned to benefit from that transition. The forklift market is predominantly electric today, with electric power sources representing about 66% of the market. That shift plays into Toyota Industries’ broader competencies, including electrification know-how developed through its automotive components work—like electric compressors and battery-related systems.

Cross-Shareholding Protection: The Toyota Group structure can be a strategic asset. The mutual ownership between Toyota Industries and Toyota Motor creates stability that a standalone industrial company doesn’t get: alignment on long-term investment, a more defensible ownership base, and a deeply integrated customer-supplier relationship. It helps protect against hostile takeovers, while also supporting steady demand for key automotive components.

Bear Case

The cautious view starts with a simple point: when you’re this deeply embedded in critical infrastructure—and in a high-trust brand—mistakes compound.

Certification Scandal Overhang: The regulatory and legal tail risk is still not fully measurable. Toyota Industries has said that “investigations by the US federal and California state authorities concerning engines for US forklifts, as well as discussions with those authorities, are still ongoing.” The USD 299.5 million settlement may close one chapter, but it doesn’t guarantee the story ends there. Additional enforcement actions could still emerge, and the reputational impact can linger longer than the fines.

Keiretsu Governance Questions: The same structure that creates stability can blur accountability. The certification issue raised uncomfortable questions about oversight inside the Toyota Group—and whether schedule pressure, coordination gaps, and unclear ownership of compliance processes created an environment where problems could persist. Investors have to wrestle with the trade-off: cross-shareholding can align incentives, but it can also soften scrutiny.

Competition from Chinese Manufacturers: The next competitive wave is coming from China. Hangcha and Anhui Heli are pushing aggressive pricing and increasingly capable electric products, and they’re expanding internationally through distributorships across Europe, MENA, and South America. That’s especially threatening in the more “commodity” parts of the forklift market, where differentiation is thinner and margin pressure shows up fast.

Toyota Motor Concentration Risk: Toyota Industries is not independent of Toyota Motor’s fortunes. With nearly 13% of consolidated sales going to Toyota Motor, shifts in Toyota’s production, product mix, or execution around the EV transition create downstream risk. When a major customer is also part of your ownership structure, “concentration” doesn’t disappear—it just wears a different outfit.

Competitive Positioning Analysis

Porter’s Five Forces is a useful way to pressure-test the materials handling business—not because it predicts the future, but because it forces clarity.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. Capital intensity, dealer networks, and service infrastructure create real barriers, especially in mature markets. But Chinese manufacturers have shown they can break into developed markets faster than incumbents expect.

Supplier Power: Low. Toyota Industries’ scale gives it purchasing leverage, and its ability to build or control key components—like engines and electric drive systems—reduces dependency.

Buyer Power: Moderate. Large logistics customers can negotiate hard, especially on fleet pricing. But equipment reliability, uptime, and the cost of switching suppliers constrain how far buyers can push.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising. In some environments, automation and robotics can reduce the need for traditional forklifts. The substitute isn’t another forklift—it’s a different way of moving goods.

Competitive Rivalry: High. The top players fight on features, durability, total cost of ownership, and service responsiveness—and increasingly on who can deliver integrated, end-to-end solutions instead of just selling machines.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers offers another lens—less about industry structure, more about durable advantage:

Scale Economies: The global footprint and purchasing volume translate into cost advantages and operational leverage.

Network Effects: Limited direct network effects, but a large dealer and service network creates an indirect advantage through coverage and responsiveness.

Counter-Positioning: The integrated “equipment + automation + service” stack is difficult for pure-play forklift makers to match quickly without doing the same kind of acquisitions Toyota Industries already completed.

Switching Costs: Parts, service contracts, operator training, and fleet standardization create real friction for customers considering a change.

Branding: The Toyota name carries weight in industrial markets. The certification issues have tested that trust, but the brand remains a meaningful asset.

Cornered Resource: The relationship with Toyota Motor—both as customer and technology partner—is unusually hard for competitors to replicate.

Process Power: Toyota’s manufacturing and quality methodologies remain a deep reservoir of know-how, even if the recent scandal showed that “having the system” and “living the system” are not always the same thing.

XI. What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

If you’re following Toyota Industries from here, the story won’t be told by a single quarter. It’ll show up in a few telltale signals—where the growth is coming from, whether the automation bet is compounding, and whether the certification crisis is truly being put behind them.

1. Materials Handling Equipment Segment Revenue Growth vs. Market Growth

This is the company’s engine today. The most important question isn’t whether Materials Handling is growing—it’s whether it’s growing faster than the forklift market itself.

A clean way to track that is to compare segment revenue growth (ideally adjusting for currency) against industry shipment and volume data, like the figures published by WITS (World Industrial Truck Statistics). If Toyota Industries is outpacing the market, that suggests share gains and durable strength in products, pricing, and distribution. If it’s lagging, the usual culprits are worth scrutinizing: competitive pressure, mix shift, or a weakening service and dealer advantage.

2. Vanderlande Order Intake and Backlog

Forklifts made Toyota Industries a leader. Automation is the bet that could redefine what it is.

Vanderlande sits at the center of that move, and its order intake is the closest thing you’ll get to an early signal on whether customers are still leaning into big automation projects. Backlog matters too—it’s a measure of revenue visibility and future workload.

If e-commerce growth cools or major logistics players tighten capital spending, automation tends to feel it quickly. So this is the place to watch for early cracks—or for confirmation that the secular tailwind is still doing what Toyota Industries bought Vanderlande to capture.

3. Legal and Regulatory Developments Related to Certification Issues

This remains the shadow over everything else. Until U.S. federal and California state investigations fully conclude, certification-related risk is still material, and it isn’t limited to fines.

The practical watch list here is straightforward: (a) additional government penalties or consent orders; (b) new or expanded class-action litigation; (c) customer contract cancellations or compensation demands; and (d) any sign the issue extends beyond the engines already identified.

A clear resolution would lift a meaningful overhang. Adverse findings—or evidence of broader scope—could do the opposite, turning what was framed as a fixable breakdown into a longer-term governance and trust problem.

XII. Conclusion: A Century of Reinvention

Toyota Industries embodies one of the great industrial paradoxes: it has stayed itself by constantly changing. A company born in a barn, obsessed with making hand weaving less punishing, ended up building the machinery that moves the world’s goods—first with forklifts, then with the automation systems that now run warehouses and airports, and increasingly with software that coordinates everything in between.

What never changed was the operating philosophy. Sakichi Toyoda’s breakthrough wasn’t just the loom—it was the idea behind it: jidoka, intelligent automation that stops at the first sign of abnormality so defects don’t multiply. Pair that with relentless waste elimination and continuous improvement, and you get a playbook that scales from fabric to factories to modern logistics.

That’s why the certification scandal landed so hard. It wasn’t only a regulatory failure; it felt like a violation of the company’s origin story. The open question now is whether those failures were a temporary break from the Toyota Industries way—or evidence that the culture that produced it has thinned under the weight of scale, complexity, and pressure.

For investors, the appeal is clear: Toyota Industries sits at the center of structural growth in materials handling and logistics automation, with a leading competitive position and a global footprint that’s difficult to replicate. The cross-shareholding relationship with Toyota Motor adds stability and tight integration with one of the world’s most important automotive ecosystems. But the governance and trust issues raised by the certification failures aren’t theoretical anymore, and they deserve ongoing scrutiny.

The next chapter will be defined by response, not rhetoric. Sakichi built a company on the principle that when something goes wrong, you stop—immediately—and you fix the root cause. The scandal revealed what happens when an organization keeps running when it should have stopped. Whether Toyota Industries can truly rebuild the culture, mechanisms, and organizational structure it has promised will determine if the next century lives up to the first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music