TBEA: The Hidden King of the Global Energy Grid

I. Introduction: The "Nvidia" of the Power Grid

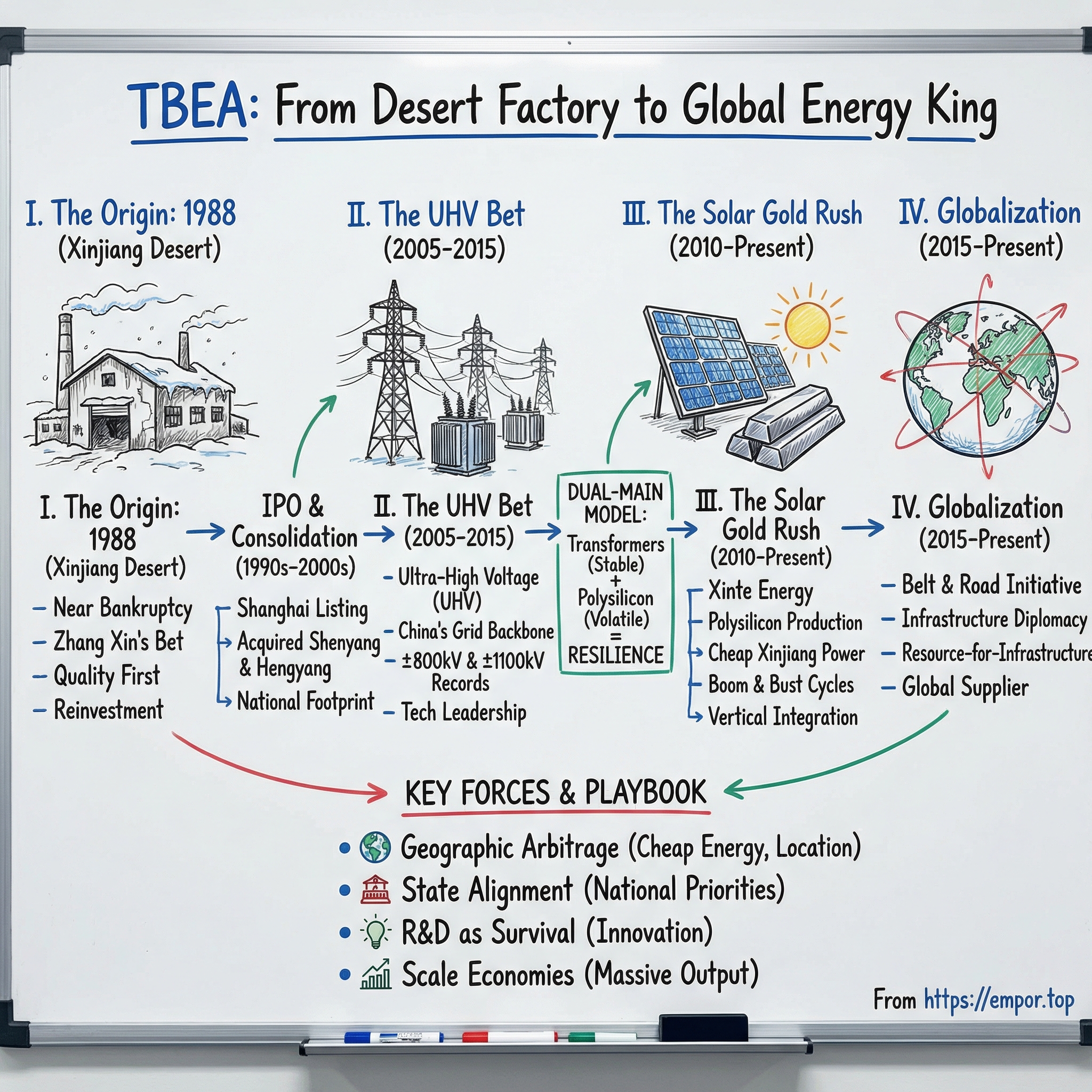

Picture this: a dusty factory floor in the deserts of Xinjiang, China’s vast northwestern frontier, in 1988. Snow has caved in the roof. Workers haven’t been paid in six months. The local government is lining up bankruptcy paperwork. By any normal measure, this is where the story ends.

Instead, it’s where TBEA begins.

Fast forward a little over three decades, and that same enterprise — TBEA Co., Ltd., originally Tebian Electric Apparatus — is sitting at the commanding heights of global energy infrastructure. In 2024, it generated roughly $13.6 billion in revenue and employed more than 30,000 people. It’s become one of the world’s biggest manufacturers of power transformers and electrical equipment — the kind of industrial muscle you only notice when it’s missing.

Because while the world obsesses over the flashy front end of the energy transition — Tesla EVs, CATL batteries, the latest solar panel brand — there’s a quieter truth most people miss: none of it works without the plumbing. The electricity that hits an EV charger. The grid that absorbs a solar farm’s output without collapsing. The transmission corridors that move power from where it’s generated to where it’s actually consumed. These are the invisible arteries of electrification. And TBEA has quietly become a dominant supplier of the hardware that makes them possible.

Inside China, TBEA holds the top rank among domestic transformer manufacturers, with more than 30% share of the national transformer market. Globally, it’s around 8% — putting it in the top tier alongside ABB, Siemens, General Electric, and China XD Group.

But the real twist is that TBEA isn’t just a “transformer company.” Through its subsidiary Xinte Energy, it’s also a major producer of polysilicon — the raw material that solar panels are built from. And it doesn’t stop upstream. Within the broader group, TBEA also manufactures solar wafers, cells, and inverters, creating an integrated renewable energy ecosystem that spans from foundational materials to the equipment that actually moves electrons around.

Think about what that means. TBEA sells the equipment that moves electricity across China’s massive grid — and it produces the material that makes modern solar possible in the first place. In gold rush terms, they’re not just selling pickaxes. They own the mine.

And here’s the part that sounds like it should be a handicap, but isn’t: geography. Being headquartered in one of the most remote places on Earth should have doomed them. Instead, it became a superpower. Xinjiang’s cheap coal-fired electricity creates brutal cost advantages for energy-intensive polysilicon. Its proximity to Central Asia opens doors to Belt and Road infrastructure projects. What looks like isolation on a map becomes strategic position in the real world.

Over time, TBEA has grown into a leading global player in power transmission and transformation, a major base for new polysilicon materials development in China, a large-scale aluminum electronics export base, and a builder and integrator of solar photovoltaic and wind power systems. Its transformer output has reached about 260 million kVA annually, ranking first in the world.

This is the story of how a bankrupt factory in the desert turned itself into an indispensable node in the global energy system — a case study in state alignment, geographic arbitrage, and the ruthless ability to catch China’s industrial waves at exactly the right moment.

II. The Origins: The "Minnow Swallows the Whale"

The winter of 1987 was brutal in Changji, a small city on Xinjiang’s wide, semi-arid plains. At the Changji Transformer Factory — a state-owned plant that had enjoyed a brief moment of glory in the planned-economy era — everything was coming apart. Years of losses piled up. Snow collapsed parts of the facility. Workers went unpaid for six months. The local government started preparing the paperwork for bankruptcy.

In most stories, that’s the ending.

Here, it’s the hinge.

Around this moment, a young technician named Zhang Xin was staring at two futures. One was straightforward: take a better-paying job at the Urumqi Chemical Plant in the regional capital and leave the mess behind. The other was irrational on paper: stay, and try to save a factory that everyone else had already written off. After watching veteran workers struggle through months without wages, Zhang chose the harder path. He stayed.

In 1988, Zhang took over as director of the factory. The outlook was grim — debts had climbed above 700,000 yuan, and liquidation was expected the following year. But Zhang wasn’t just stepping into a management job. He was stepping into China in 1988: the early reform era, when state-owned enterprises were being pushed — sometimes dragged — from command-economy habits into something resembling market competition. For an ambitious young engineer, the smart move was usually to get out. Zhang decided to rebuild from within.

His turnaround playbook was simple, and unforgiving. The first order of business was culture: the factory had to stop producing “good enough” equipment and start producing equipment that could survive in the real market. Zhang imposed a strict quality regime that stunned workers raised on planned-economy complacency. The vibe was unmistakably similar to Haier’s famous moment, when Zhang Ruimin smashed defective refrigerators with a sledgehammer to make the point: quality wasn’t a slogan. It was law.

It worked. The factory stabilized, then returned to profitability. And Zhang didn’t treat the first real money the company saw as something to spend.

In 1992, the business received a two million yuan government reward. Many companies would have distributed it, taken the morale boost, and moved on. Zhang persuaded employees to do the opposite: reinvest it as capital for development. That decision set up a shareholding reform, and in 1993 the company officially rebranded as Xinjiang Special Transformer Manufacturing Co., Ltd. Instead of a one-time windfall, it became fuel — a collective bet that a small desert factory could become something much bigger.

Then came the moment that made the ambition undeniable. On June 18, 1997, TBEA Co., Ltd. listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, becoming the first publicly listed company in China’s transformer industry. The IPO wasn’t just a financing event. It was a declaration: this company in far-western Xinjiang intended to play a national game.

And with public-market capital behind it, Zhang moved fast.

Instead of growing slowly, plant by plant, contract by contract, TBEA went straight for consolidation. It did something almost unthinkable for a remote western company: it acquired some of the most important transformer assets in China’s industrial East. TBEA Hengyang Transformer Co., Ltd. and TBEA Shenyang Transformer Group Co., Ltd. became core subsidiaries, giving the company a true national footprint. Shenyang Transformer, founded in 1938, wasn’t just another factory — it was one of China’s oldest industrial enterprises.

It’s hard to overstate how bold this was. A company that had been on the verge of bankruptcy less than a decade earlier was now absorbing venerable institutions in Shenyang and Hengyang — cities that sat deep in China’s manufacturing heartland. It was like a tiny regional bank in Nebraska buying the crown jewels of American finance. Overnight, the deals consolidated the transformer industry and handed TBEA technical depth and credibility it could never have built fast enough on its own.

Zhang’s grip on the wheel only tightened. He became chairman on December 31, 2003, and his long tenure brought something rare in heavy industry: continuity. While many Chinese industrial firms cycled through leadership changes, TBEA kept the same operator running the same playbook.

By the mid-2000s, the transformation was complete. The dying workshop in Changji had become a national champion.

But the next chapter — the one that would turn TBEA from a strong manufacturer into a strategic partner of the world’s largest power grid — was still ahead. China was about to bet on ultra-high voltage transmission, and TBEA was about to bet right alongside it.

III. Inflection Point 1: The UHV Bet (2005–2015)

To understand what TBEA pulled off with ultra-high voltage transmission, you first have to understand China’s core energy problem. It isn’t a lack of resources. It’s a map.

China’s biggest electricity demand sits in the east and southeast — dense coastal megacities and factory belts. A huge share of its energy supply sits far away in the west and northwest: coal in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi; wind across the Gobi; sun on the Tibetan plateau. The country’s growth basically depended on solving one brutal mismatch: how do you move massive amounts of power across two to three thousand kilometers, without losing it along the way?

With conventional transmission, the losses become painful at that scale. Over long distances, a meaningful chunk of electricity bleeds away as heat. For an industrializing superpower, that’s not just inefficient — it’s a constraint.

China’s answer was Ultra-High Voltage, or UHV. Think of it as the bullet train of electricity. Higher voltage means you can move more power farther, with lower losses. And once China decided this was the solution, it went after it with the same intensity it brought to high-speed rail: set records, build fast, and make the technology its own.

State Grid’s UHV buildout culminated in a line that reads like science fiction: a 1.1-million-volt direct current transmission project, capable of moving up to 12 gigawatts — enough to power roughly 50 million households, and far more than the earlier generation of 800-kilovolt lines.

The technical leap here mattered. Before China’s push, the high-water mark for AC transmission voltage was 765 kilovolts. China didn’t just edge past that. It blew through it, first commercializing 800kV systems and then moving to 1,100kV. At those voltages, you’re not iterating. You’re reinventing. Insulation requirements change. Physical clearances change. The electromagnetic environment changes. The transformer stops being a piece of equipment and starts being a landmark.

This is where TBEA made the bet that turned it from “national champion” into “strategic supplier.”

TBEA went all-in on UHV R&D and manufacturing — and it paid off. The company successfully developed China’s first ±800kV UHV DC transformers to pass critical tests, with performance indicators like no-load and load loss, temperature rise, and noise reaching top-tier levels.

Then came projects that forced the technology out of the lab and into the real world. The Hami–Zhengzhou ±800 kV UHV DC Project was China’s first UHV DC project independently designed, manufactured, and built domestically. It was also a flagship “Electricity Send Outside Xinjiang” initiative — moving power from the far west into central and eastern load centers. The line ran about 2,210 kilometers, crossing Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Henan, and it entered operation on January 27, 2014.

And the hardware required was almost absurd in scale. The converter transformers TBEA supplied were roughly 33 meters long, 12 meters wide, and 18.5 meters high. You don’t casually ship something like that across a continent on standard logistics. So TBEA did the obvious thing — once you think like TBEA: it built UHV transformer manufacturing capacity in Xinjiang, close to the western endpoints of these lines, cutting transport costs and complexity. The remoteness that used to look like a disadvantage turned into a manufacturing edge.

The geopolitical and competitive subtext was just as important. TBEA wasn’t only racing domestic peers. It was up against ABB and Siemens — the Western incumbents that had owned the high-voltage playbook for decades.

In the early days of China’s UHV DC push, that dominance showed: converter transformers for initial projects were largely foreign-designed, and assembled in China using imported materials. The implication was clear. China could build the lines, but it was still dependent on others for some of the most critical brains and components.

TBEA’s success helped change that equation. Its participation in “±800kV DC converter transformer independent development and engineering application” was later recognized with a second prize in the 2020 National Science and Technology Progress Award. By then, TBEA had accumulated a long list of national-level science and technology awards — a signal of how central this work had become to Chinese industrial strategy.

The march continued. In March 2008, TBEA Shenyang Transformer Group completed the design of a 1,000 kV transformer — a key component for UHV transmission. And as UHV moved beyond classic AC/DC into more advanced architectures, TBEA kept pace: in 2017 it successfully developed the world’s first UHV flexible DC transmission converter valve; in 2018 it won the bid for China Southern Power Grid’s Wudongde project; and in 2020 that project entered production smoothly.

At the top of the pyramid sits the Changji–Guquan UHVDC transmission line: the world’s first operating 1,100kV UHVDC line, owned and operated by State Grid, also setting records for distance and transmission capacity.

Commercially, the implications were huge. By becoming a key supplier to China’s UHV buildout — one of the largest infrastructure programs ever undertaken — TBEA locked in a foundation business with stability and scale. Supplying state-prioritized grid projects isn’t like selling commodity hardware into a fragmented market. It’s long-cycle, high-spec, policy-backed demand.

A pivotal inflection point came when TBEA delivered ±1100 kV UHV converter transformers for China’s West–East power transmission backbone. It wasn’t just shipping equipment anymore. It was moving into the role of full-stack partner — spanning power transmission and, increasingly, broader new-energy solutions.

And it established a pattern that would repeat again and again: TBEA didn’t wait for national priorities to arrive. It invested ahead of them, then showed up as the company the grid operators couldn’t do without.

IV. Inflection Point 2: The Solar "Gold Rush" (2010–Present)

After UHV, Zhang Xin made a pivot that, in hindsight, looks almost inevitable — and in the moment looked like a completely different game. Moving electricity was a great business. But supplying the raw material for new energy could be even better.

The key insight was about physics, not finance. Polysilicon — the ultra-pure silicon that becomes solar cells (and, in other contexts, feeds the semiconductor world) — is brutally energy-hungry to make. Producing one kilogram can take something like 50 to 80 kilowatt-hours of electricity. In most places, that power bill is exactly what prevents you from being globally competitive.

Xinjiang is not most places.

With abundant coal and some of the cheapest electricity rates on the planet, Xinjiang turned polysilicon from “expensive specialty chemical” into “industrial-scale manufacturing opportunity.” And for TBEA, it was the same geographic trick they’d already pulled in UHV: take what looks like remoteness and convert it into cost advantage.

That’s the origin story for Xinte Energy, the TBEA-controlled platform that became the group’s spearhead in solar materials. Xinte poured huge money into capacity. One expansion plan alone called for about 8.799 billion yuan, with roughly a year and a half of construction time. By the end of 2020, Xinte had built up around 72,000 tons per year of polysilicon capacity, ranking third in China behind GCL-Poly and Yongxiang. That mattered in a country that, in 2020, produced roughly 396,000 tons of polysilicon — a figure that was still growing year over year.

This wasn’t diversification for its own sake. It was geographic arbitrage at industrial scale. Xinjiang let TBEA manufacture giant grid hardware close to western grid connection points — and it also gave Xinte the electricity economics to compete in one of the world’s most power-intensive commodities.

And once you’re on the right side of the cost curve, you don’t dabble. You scale. Xinte’s polysilicon division later announced plans to invest roughly RMB 17.6 billion to expand capacity by another 200,000 metric tons.

Of course, solar has never been a smooth ride. The industry’s defining feature is its boom-and-bust cycle — and from 2011 to 2013, it got ugly. A global price war, driven by overcapacity, wiped out dozens of companies. Big names like Suntech went bankrupt. In a downturn like that, the question stops being “who has the best technology?” and becomes “who can stay alive long enough for the cycle to turn?”

TBEA could, because it had something most solar players didn’t: a cash-generating core business that wasn’t tied to solar pricing. Transformers and grid equipment kept selling. The infrastructure machine kept running. And that steady cash flow became a shock absorber while the solar materials side took hits.

Then the cycle swung the other way. Demand surged, and Xinte argued it couldn’t make polysilicon fast enough. It pushed shareholders to back a plan to massively expand capacity by mid-2024, pointing to strong order demand from customers like LONGi and JA Solar and claiming sales visibility for several years, even with an additional 100,000-ton facility in Inner Mongolia on the way.

By the early 2020s, Xinte had become one of the global “Big Four” polysilicon producers, alongside Tongwei, GCL, and Daqo New Energy. TBEA had done it: it captured one of the tightest upstream bottlenecks in the solar supply chain.

Then came the part that reminds you why this industry is infamous.

Starting in early 2023, polysilicon prices collapsed. What had been around RMB 235 per kilogram in February 2023 fell to roughly RMB 32 per kilogram by late August 2024 — an implosion of more than 85%. The pain was universal at the top: according to Bernreuter Research, the world’s four largest polysilicon producers — Tongwei Solar, GCL Technology, Daqo New Energy, and Xinte Energy — all posted net losses in the first half of 2024.

This wasn’t a normal downturn. It was the industry’s most brutal slump yet, the same boom-bust math from 2011–2013 returning at a much bigger scale. A shortage-driven price peak near US$39/kg in 2022 had triggered massive expansion across China. By the end of 2024, capacity had ballooned to roughly 3.25 million metric tons, and China accounted for more than 93% of global polysilicon output — even higher for solar-grade material.

In that environment, even low-cost producers had to make defensive choices. TBEA said its polysilicon operations were running at about a 25% operating rate, and it guided for roughly 15,000 to 16,000 tons of output in the fourth quarter, arguing that — at current prices — it was more economical to hold production there.

Financially, the downturn hit exactly where you’d expect. TBEA’s 2024 earnings forecast called for net profit of about CNY 3.9 billion to CNY 4.3 billion, down from the prior year. Xinte Energy, listed in Hong Kong, forecast a 2024 loss of about CNY 3.8 billion to CNY 4.1 billion, attributing it to the sharp drop in polysilicon prices. On a consolidated basis, TBEA reported 2024 operating income of 97.87 billion yuan, essentially flat year over year, while net profit fell to 4.13 billion yuan, down 61% — driven mainly by heavy losses in polysilicon.

And here’s the point: the crash exposed the risk of Zhang Xin’s strategy, but it also validated the design.

Yes, Xinte bled. But TBEA stayed profitable because the transformer business is a different animal — infrastructure-driven, policy-backed, and far less cyclical than a commodity priced in a global glut. In the bad years, that division is ballast. It keeps the ship upright when the solar cargo shifts violently.

This is the dual-main model in its purest form: steady grid equipment funding — and stabilizing — a volatile, high-stakes bet on the materials that power the energy transition.

V. Globalization: The Belt and Road Blueprint (2015–Present)

By the mid-2010s, China’s domestic grid buildout was no longer an endless frontier. The easiest growth was behind it. So TBEA did what a China-scale industrial champion does when the home market starts to mature: it went looking for the next map problem to solve.

The Belt and Road Initiative, launched by Xi Jinping in 2013, gave that outward push both a political tailwind and a practical playbook. TBEA began showing up not just as an exporter of equipment, but as a builder of entire national power systems.

It landed marquee contracts in Central Asia, including a roughly $500 million State Grid construction project in Tajikistan and a roughly $580 million north–south grid construction project in Kyrgyzstan — described as the largest energy deal at the time between China and Kyrgyzstan.

From there, the footprint widened. TBEA has said it provided energy equipment to more than 70 countries, spanning markets as varied as Russia, Brazil, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

But the more interesting part isn’t simply that TBEA sold transformers abroad. It’s how the deals were structured.

In many Belt and Road markets, the limiting factor isn’t demand for power infrastructure. It’s the ability to pay for it. That’s where TBEA’s international playbook starts to look less like “equipment exports” and more like “development finance, packaged as engineering.”

Tajikistan is the clearest example. In exchange for building major energy infrastructure in the capital — including the Dushanbe-2 combined heat and power plant — TBEA received mining rights. Reports say that after TBEA built combined heat and power capacity in Dushanbe in 2016, Tajikistan’s President Emomali Rahmon granted the company exclusive rights to operate two gold mines, with TBEA operating them until it recouped its investment, cited at $332 million. Separately, in 2015, TBEA was granted a mining license to develop the Upper Kumarg and Eastern Duoba gold deposits in the Sughd Region, also tied to the Dushanbe-2 project.

This is the resource-for-infrastructure swap in its pure form: a country without easy access to capital markets pays with what it does have — natural resources — and the contractor effectively underwrites the project by taking the upside through operating rights.

TBEA has run versions of this play across a wider set of markets. In Ethiopia, it was contracted to develop the transmission line from the Gilgel Gibe III Dam to Addis Ababa in 2009. In Zambia, it signed a $334 million EPC contract in 2010 with ZESCO to build 330 kV high-voltage transmission lines.

It also built an on-the-ground manufacturing presence. Through TBEA Energy (India) Pvt Ltd. in Karjan, Gujarat, the company manufactures transformers, solar equipment, and cables aimed at India and export markets across Africa and the Middle East.

Over time, the contract tally added up. TBEA has said it executed nearly $6 billion in ongoing contracts across Belt and Road countries, giving it a first-mover advantage in markets where being early often determines who becomes the default supplier.

And even amid the polysilicon downturn at home, the overseas equipment business showed momentum. In 2024, TBEA reported export contracts of $1.2 billion, up more than 70% from the prior year.

Still, this kind of expansion doesn’t come with clean edges.

In Kyrgyzstan, the selection of TBEA to rebuild the Bishkek power plant became politically charged. Reporting described how the Chinese embassy in Bishkek “recommended” choosing TBEA, and how a major Chinese loan was tied to that decision. The project later became entangled in controversy over allegedly inflated costs and corruption accusations against local officials. When the plant suffered a breakdown in 2018 shortly after reopening, preliminary investigations indicated the failure occurred in a section that had not been rebuilt by TBEA — but by then, the reputational damage and political fallout were already real.

That’s the Belt and Road trade-off in one story: the opportunity is access. The risk is that the business is never only business.

TBEA’s globalization phase shows the company operating in a gray zone where commercial objectives, host-country politics, and Chinese state strategy overlap. For TBEA, that can unlock projects competitors can’t touch. For everyone involved — including investors — it also means the company inherits the geopolitics that come with being, in effect, part of China’s infrastructure diplomacy.

VI. The Playbook: Lessons from the Desert

TBEA’s rise — from a half-collapsed factory in Changji to a company that builds the backbone of grids and feeds the solar supply chain — isn’t luck. It’s a repeatable playbook. And once you see it, you start noticing the same moves show up again and again.

The "Dual-Main" Business Model

At first glance, TBEA looks like a corporate chimera: transformers and transmission equipment on one side, polysilicon and solar materials on the other, plus utility-like assets and engineering projects layered in. You almost can’t evaluate it as one business; it naturally pushes you toward a sum-of-the-parts way of thinking.

But the pairing that matters most — transformers and polysilicon — is more deliberate than it looks. These businesses share one key advantage: both get structurally better when your electricity is cheap. Yet their cycles couldn’t be more different. Grid equipment is infrastructure-driven and comparatively steady. Polysilicon is commodity-driven and violently cyclical.

Put them together, and you get a self-balancing system. When polysilicon is booming, it pulls the group’s growth forward. When polysilicon collapses, the transformer business keeps generating cash and keeps the whole machine standing. In other words: the stable business funds the volatile one — and, just as importantly, gives it the patience to survive the downcycles that wipe out weaker competitors.

Geographic Arbitrage

TBEA’s location should have been its curse. Instead, it became the cornerstone of its cost advantage.

Xinjiang’s low labor costs and, more critically, ultra-low power prices turned energy-intensive manufacturing into a home-field game. In places like Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, electricity prices have been cited around 0.25 yuan per kilowatt-hour — the kind of number that changes what’s economically possible. With that power advantage, leading players have pushed cash costs down to under 30,000 yuan per ton.

And this isn’t a “nice-to-have.” For polysilicon, it’s existential. Electricity is such a large share of the cost structure that paying 0.50 yuan/kWh instead of 0.25 can be the difference between being profitable and being forced to shut down. TBEA didn’t just build a polysilicon business in Xinjiang. It built it in one of the few places where the economics can still work when the market turns ugly.

State Alignment

A huge part of TBEA’s story is that it rarely fights the tide. It swims with it — in near-perfect synchronization with China’s industrial priorities.

In the 2000s, China needed a stronger, more modern grid, and UHV became a national mission. TBEA leaned in and became a key supplier. In the 2010s, China pushed to dominate solar manufacturing, and TBEA scaled polysilicon through Xinte. In the 2010s and 2020s, Belt and Road created a pipeline for overseas grid-building, and TBEA showed up with the equipment, the engineering, and often the financing structure to win.

That alignment doesn’t just create demand. It amplifies competitive advantage. TBEA’s large-scale manufacturing capacity lets it produce at low cost and bid aggressively, especially in developing markets where high-voltage equipment is needed and price matters.

R&D as Survival

For a heavy-industry company, TBEA has treated R&D not as a line item, but as a survival trait.

In an industry where competitors often spend only a small share of revenue on research, TBEA kept pushing higher — and it shows in the output. Within its flexible transmission work, the company has been authorized 115 patents and software works related to converter valves and valve control systems, including 52 invention patents. Over years of development, it has accumulated more than 100 patents and software copyrights in this area.

That sustained R&D commitment is what made the UHV breakthroughs possible — the difference between being a manufacturer of “big metal boxes” and being a technology leader with real barriers to entry.

VII. Analysis: Powers & Forces

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework makes TBEA’s edge easier to see, because it forces you to separate what’s merely “big” from what’s actually defensible.

Cornered Resource (Strongest Power): Xinjiang’s ultra-cheap coal-fired electricity. In polysilicon, power cost isn’t a line item — it’s the game. TBEA gets access to industrial power prices that competitors in the US or Europe simply can’t match, and that advantage is geographic. A German or American rival can’t just “execute better” and magically buy 0.25 yuan/kWh electricity. This is structural.

Scale Economies: TBEA’s transformer output has reached about 260 million kVA annually, ranking first in the world. That kind of scale matters in heavy manufacturing. It improves procurement leverage on copper, steel, and specialized components, and it spreads fixed costs — plants, tooling, engineering — across a bigger base, pushing down the per-unit cost.

Process Power: Building world-leading ±1100kV UHVDC converter transformers isn’t something you copy from a spec sheet. It’s accumulated know-how: design, manufacturing, testing, logistics, and on-site commissioning at the edge of what physics allows. That capability creates real barriers, because it can’t be bought quickly. It’s earned over decades of project reps — and those reps are scarce.

State Affiliation (Unlisted but Crucial): This isn’t a formal Helmer “power,” but it functions like one. TBEA’s deep alignment with Chinese industrial priorities and its working relationship with the state ecosystem give it privileged access to the largest single buyer of power equipment on Earth — and to the projects that matter most.

Through Porter’s Five Forces, you get the flip side: where the pressure points are.

Buyer Power (High): TBEA sells into a customer set dominated by giants: State Grid, China Southern Power Grid, major utility developers, and state-linked or government customers across Belt and Road markets. At home, State Grid is the center of gravity — a near-monopsony in practice. That concentration is a blessing because it creates massive, policy-backed demand. It’s also a constraint, because pricing power sits heavily with the buyer. For the domestic transformer business, TBEA is, to a meaningful extent, tied to one customer’s capex cycle.

Supplier Power (Low): Most key inputs are commodities — copper, steel, and silicon feedstock — and TBEA is a huge purchaser. That typically keeps suppliers from having much leverage.

Threat of Substitution (Medium): The long-term “substitute” for massive transmission buildouts is more distributed generation — rooftop solar, local storage, microgrids — which could reduce the need for giant UHV corridors. But TBEA’s hedge is built into its structure. If the world decentralizes generation, TBEA still participates upstream through polysilicon and other solar value chain exposure. If the world stays centralized, TBEA sells the grid hardware.

Competitive Rivalry (Moderate): UHV equipment is not a free-for-all; it’s closer to an oligopoly. Domestically, TBEA competes with players like Tianwei Baobian Electric and China XD Group. Globally, ABB and Siemens are credible incumbents. But in many markets — especially price-sensitive ones — TBEA’s cost structure and scale give it room to win.

Threat of New Entry (Low): The barriers are stacked: massive capex, deep engineering complexity, long qualification cycles, and relationship-heavy selling into conservative utility buyers. You don’t wake up one day and decide to start a ±1100kV transformer business from scratch.

VIII. The Bull & Bear Case

The Bull Case

The cleanest version of the TBEA bull case is simple: the world is rewiring itself.

Electricity demand is rising not just because more people want more power, but because entire categories of consumption are shifting onto the grid. Transportation is moving from gasoline to charging. Industry is reshoring and retooling. And the newest load is the most relentless of all: data centers, supercharged by AI.

In the U.S., data center electricity demand is projected to grow at a roughly mid-teens annual rate from 2024 to 2030. In China, State Grid has signaled it expects data center power demand to double by 2025. However you slice it, this is the same story told in different accents: a grid that was “big enough” is suddenly not big enough.

That reality is already turning into capital spending. When State Grid unveiled a plan to upgrade China’s power networks totaling about 4 trillion yuan, shares of Chinese grid-equipment companies jumped. The operator also indicated fixed-asset investment would rise by roughly 40% through 2030 versus the 2021–2025 period.

For TBEA, that’s oxygen. Every data center needs a high-quality grid connection. Every EV needs charging infrastructure. Every new solar or wind base needs the ability to push power into the network without tripping it. That translates into transformers, transmission equipment, and increasingly the ultra-high-voltage backbone that makes China’s west-to-east power flow possible.

And this isn’t just a China story. In 2024 alone, more than $80 billion was invested in power grid infrastructure, including UHV lines designed to connect remote generation with coastal demand centers. If you believe electrification is a multi-decade theme, then the “plumbing” budget tends to follow.

On the polysilicon side, the optimistic view is cyclical: today’s brutal downturn is the setup for tomorrow’s shakeout. When prices collapse, marginal players lose money first, then lose financing, then eventually lose the ability to keep operating. Survivors regain leverage. TBEA’s advantage is that it sits among the lowest-cost producers, largely because Xinjiang power is so cheap. If the industry has to shrink to heal, the bet is that TBEA is one of the companies still standing when it does.

The Bear Case

Three risks loom large:

Geopolitical Risk: Xinjiang is both TBEA’s cost engine and its biggest headline risk. Under the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), goods linked to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region can be blocked from entering the United States, and polysilicon is explicitly among the high-risk sectors Congress has focused on. A May 2021 report by Sheffield Hallam University’s Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice identified TBEA’s involvement in state-directed “poverty alleviation” and surplus labor transfer programs, citing Chinese state media and corporate disclosures describing requirements for firms to absorb transferred laborers in exchange for approvals and incentives.

Even if TBEA’s direct exposure to U.S. customers is limited, the practical danger is broader: reputational damage, tighter compliance requirements, and supply-chain contagion that can make global customers and partners reluctant. In the energy transition, “cheap” isn’t enough if your product can’t cross borders.

Polysilicon Overcapacity: The solar materials side is still trapped in a glut. By the end of 2024, polysilicon inventories had reportedly built up to around 400,000 metric tons, and spot prices in China fell below about $4.50 per kilogram—beneath the cash costs of most producers. In that kind of market, even advantaged players can bleed. TBEA’s low-cost position improves its odds, but it doesn’t repeal commodity math—especially when prices hover below $5/kg and losses are already visible, as Xinte’s 2024 results showed.

State Grid Dependency: The other concentration risk is closer to home. TBEA’s domestic transformer business remains heavily tied to State Grid of China. If Chinese infrastructure spending slows—because of fiscal pressure, demographic drag, or a policy pivot—TBEA’s core cash engine takes the hit. And because State Grid is such a dominant buyer, there’s only so much TBEA can do to diversify that exposure quickly.

IX. Key Metrics to Track

If you want a simple dashboard for how TBEA is really doing, it comes down to three numbers — one for the stable engine, one for the volatile bet, and one for the company’s escape hatch from domestic dependence.

1. Power Transmission Equipment Gross Margin: This is the pulse of TBEA’s core business — the transformer and grid-equipment segment that’s supposed to be steady. In a healthy world, you’d expect this to sit in the high-teens to low-twenties. If it starts sliding, that’s usually your first warning sign that competition is intensifying or State Grid is squeezing pricing harder than usual.

2. Polysilicon Unit Cash Cost (yuan/kg): In the downcycle, this is survival. When polysilicon prices collapse, the winners aren’t the ones with the best PowerPoint — they’re the ones with the lowest cost per kilogram. The key question is whether TBEA can keep its cash cost below the market clearing price, and whether it’s still pushing that cost curve down quarter after quarter.

3. International Contract Value: This is the diversification story in one line. If TBEA is serious about reducing its reliance on State Grid, the overseas order book has to keep growing — Belt and Road projects, emerging-market grids, EPC work, and exports. A rising contract pipeline signals momentum and widening reach. Flat numbers suggest the global expansion narrative is losing traction.

X. Conclusion: What TBEA Reveals About Modern Industrial China

TBEA is a near-perfect case study of modern industrial China: heavy manufacturing at extreme scale, deep state alignment that works as both tailwind and tether, a ruthless focus on the supply-chain choke points that actually matter, and a knack for turning “middle of nowhere” geography into an economic weapon.

Zhang Xin’s arc — from a young technician deciding not to walk away from a collapsing factory to the long-serving chairman of a global grid-and-energy company — tracks the broader story of China’s reform era. TBEA rose by riding national priorities rather than fighting them, while still keeping enough strategic freedom to build a second engine in solar materials and resources.

Now the model gets stress-tested again. The polysilicon slump is squeezing profits. Geopolitics, especially anything tied to Xinjiang, can shut doors in global markets no matter how competitive the cost curve looks. And as China’s grid buildout matures, the “obvious” domestic growth of the last two decades won’t be as effortless to repeat.

Still, the strategic position is hard to ignore. The world is electrifying, and electrification is, by definition, a grid story. China is building renewables at a staggering pace, and it’s also building the transmission backbone to make those renewables usable at scale. TBEA sits right at that intersection: it supplies the hardware that moves power, and through Xinte, it supplies one of the most important raw materials that helps generate it.

In other words, when the energy transition gets discussed as brands and breakthroughs, TBEA is the part people forget. The infrastructure layer. The industrial plumbing. The unsexy components you only notice when they fail — and the ones that quietly determine how fast the rest of the future can arrive.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music