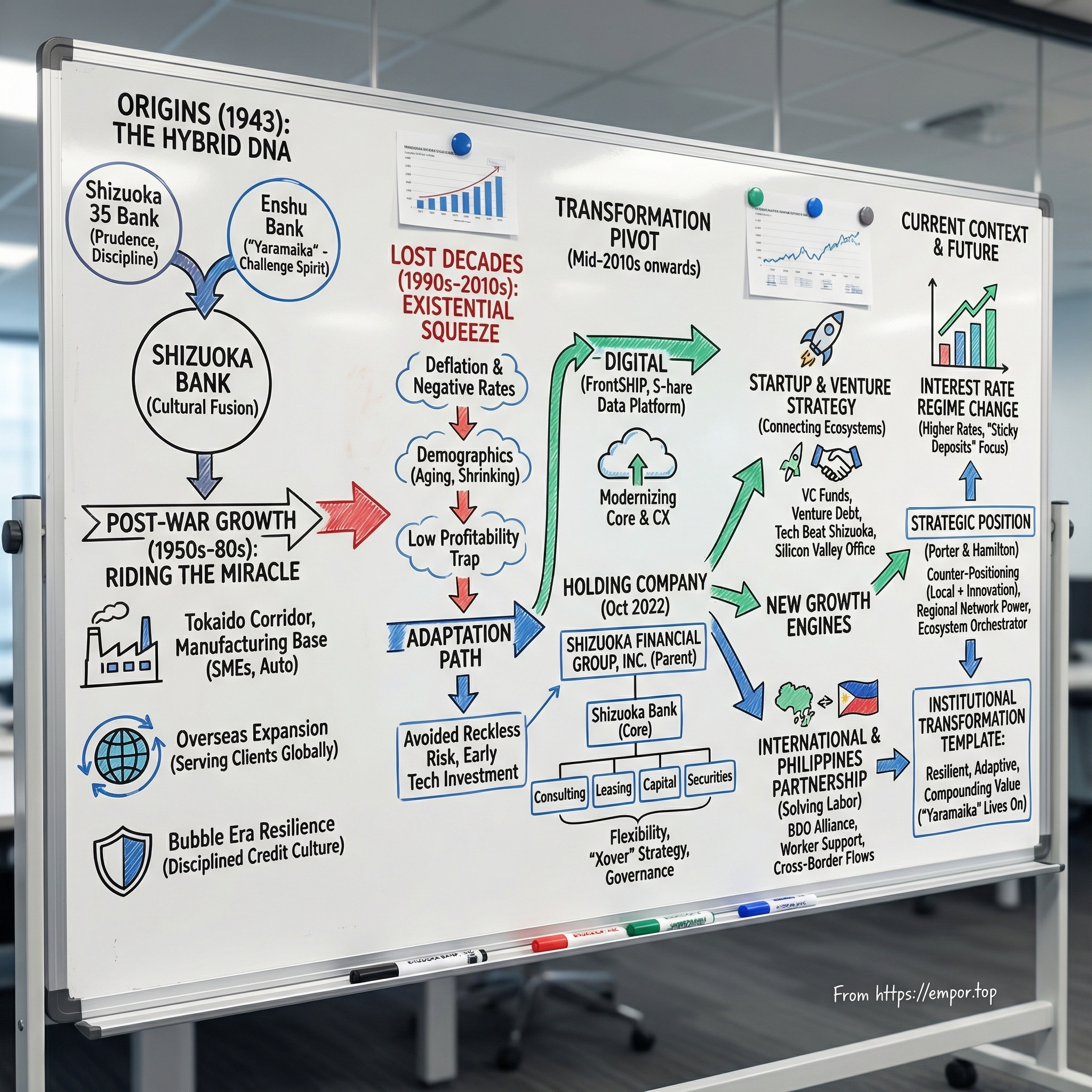

Shizuoka Financial Group: The Quiet Giant of Japan's Regional Banking Renaissance

I. Introduction: A Bank Forged Between Two Japans

Picture early morning in central Japan: sunlight across a bank headquarters, Mt. Fuji anchoring the horizon in one direction, the Tokaido corridor pulling toward Tokyo in the other. From this perch sits one of Japan’s largest regional banking franchises—more than 190 domestic branches, concentrated in the Tokai region between Tokyo and Osaka, plus outposts in Los Angeles, New York, Brussels, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Singapore.

This isn’t a megabank ruling from the glass towers of Marunouchi. It’s Shizuoka Financial Group—the parent company created in October 2022 to coordinate a reinvention that most people don’t associate with a regional lender. The question at the heart of this story is simple, but the answer isn’t: how does a bank born from wartime consolidation turn itself into a digital-forward, startup-investing, globally connected financial group while so many of its peers are fighting just to stay afloat?

The October 2022 shift to a holding company structure made Shizuoka Financial Group, Inc. the parent over 14 group companies, with a clear intent: tighten collaboration across the group and raise corporate value. But this wasn’t a last-ditch gamble. It was a deliberate move made from relative strength—an attempt to buy flexibility in an industry where many competitors had run out of room to maneuver.

To understand how they got there, we have to rewind: back to 1943, then forward through Japan’s post-war miracle, through the long deflationary grind of the lost decades, and into today’s world of demographic decline and a changing interest-rate regime. And threading through all of it is a phrase from local dialect that captures the institution’s posture toward change: “Yaramaika”—“Let’s give it a try!”

This story matters because Japan’s regional banks are under structural pressure. Their business is local by design—individuals, small businesses, community lending—and that model has been squeezed by years of low profitability, prolonged low interest rates, an aging and shrinking population, and the simple reality that a bank can’t easily outgrow the economic vitality of its home region. In that environment, Shizuoka chose a different playbook: pair conservative balance-sheet discipline with aggressive digital transformation—and lean into venture and startup engagement in ways you wouldn’t expect from a traditional regional bank.

What follows is the story of how geography, culture, and strategic timing combined to build one of the most resilient regional banking groups in Japan—and what it can teach anyone trying to understand how legacy institutions adapt, before they’re forced to.

II. Shizuoka Prefecture: The Geography That Made the Bank

Before you can understand Shizuoka Bank, you have to understand the ground it stands on.

Shizuoka Prefecture sits on one of Japan’s most important pieces of real estate: the corridor between Tokyo and Osaka. For centuries, the old Tokaido road ran straight through here, linking Edo (today’s Tokyo) with Kyoto. Modern Japan followed the same path. Highways, rail lines, supply chains, and talent flows still funnel through Shizuoka, making it less a “province” and more a connective tissue between the country’s biggest economic engines.

And Shizuoka doesn’t just sit between markets. It produces.

Manufacturing is the story. Shizuoka’s manufacturing economy is large enough to matter at the national level—roughly 5% of Japan’s GDP—and within the prefecture it’s even more dominant, accounting for around 40% of regional GDP. That single fact changes everything for a regional bank. Your customers aren’t only local merchants and households; they’re precision manufacturers, auto and motorcycle supply chains, and export-oriented companies that live and die by global demand.

The industrial mix even shifts as you move across the map. In the east: electrical machinery, paper and pulp, medical products, and transport equipment. In the west: transport equipment again, plus general machinery, chemicals, textiles, and high-end optoelectronics. Shizuoka isn’t a one-industry town scaled up—it’s an entire industrial ecosystem spread across a prefecture.

The western side, anchored by Hamamatsu, is where the culture gets especially interesting. Hamamatsu is one of those places that shows up again and again in the footnotes of Japanese industrial history. It’s where Suzuki, Honda, and Yamaha all trace key roots—global names that started as local experiments. Michio Suzuki founded Suzuki Loom Works in Hamamatsu in 1909, beginning with weaving looms before eventually moving into motorized bicycles and, later, vehicles. That arc—from practical manufacturing to ambitious reinvention—wasn’t an exception here. It was the pattern.

Locals even have a word for it. Enshu, based around Hamamatsu, developed a reputation as the more daring part of the prefecture, and the dialect captured that attitude in one phrase: “Yaramaika”—“Let’s give it a try!”

Zoom out one level and Shizuoka is part of an even bigger machine. Along with Aichi, Gifu, and Mie—about 15 million people in total—this is Japan’s industrial heartland, built on monozukuri: the pride and discipline of “making things.” For Shizuoka Bank, that meant its home market was wired into the national economy in a way many regional banks could only envy.

Then there’s the rest of the portfolio. Shimizu, as a port city, adds maritime commerce and trade. Agriculture contributes world-famous green tea and mandarin oranges. Mt. Fuji brings tourism and an entire service economy in its shadow. That diversity matters because it stabilizes a bank’s balance sheet: deposits and loans spread across manufacturing, trade, agriculture, and services tend to hold up better when any single sector hits turbulence.

There’s one more geographic twist: proximity. Being wedged between Tokyo and Nagoya creates a constant gravitational pull—capital and talent flowing toward the metros. But it also creates a lane for Shizuoka: serving companies that prioritize manufacturing efficiency and supply-chain access over headquarters prestige. That tension—between outflow and opportunity—helped shape a bank that learned early how to compete on relationships, specialization, and resilience, not just on being the biggest name in the biggest city.

In other words: for Shizuoka Bank, geography wasn’t backdrop. It was strategy.

III. Origins: The Wartime Merger That Created a Cultural Hybrid

March 1, 1943. Japan was deep into World War II, and the government was ordering banks to consolidate—less fragmentation, more control, more financing capacity for the war economy. Out of that mandate came the institution that would become Shizuoka’s dominant financial franchise: The Shizuoka Bank, created through the merger of the Shizuoka Sanjyu-go Ginkō (静岡35銀行) and the Enshu Ginkō (遠州銀行).

On paper, it looked like just another wartime mash-up. In practice, it produced something far more durable: a cultural hybrid that would shape the bank for decades.

The two predecessors brought very different instincts to the same balance sheet. “Shizuoka 35 Bank” was rooted in Japan’s national banking system and carried a solid, disciplined corporate culture—methodical operations, careful risk taking, stability first. The kind of banking that plays defense well, because it assumes the future will eventually test you.

Enshu Bank came from the other side of Shizuoka’s personality. Based in Hamamatsu, it grew up alongside the region’s most ambitious companies, in a place where the challenge spirit had already taken root. It served builders and experimenters—customers who needed a bank willing to lean in, not just say no. Its culture reflected the local dialect’s defining phrase: “Yaramaika”—“Let’s give it a try!” That spirit is still described today as part of the bank’s DNA.

A merger like this could have been a slow-motion integration problem: mismatched values, internal friction, decision-making paralysis. But Shizuoka’s version of the story is that the friction became a feature. Leadership later summed it up plainly: the fusion of prudence and challenging spirit forms the DNA of Shizuoka Bank—and that balance became its greatest strength.

You can see how that plays out in real decisions. The Enshu heritage pulls the organization toward new initiatives and new customers; the Shizuoka 35 heritage insists that every leap has a harness. One side pushes for motion, the other for control—and together they create a bank that can try things without betting the franchise.

From there, the institution describes its governing principles as “commitment to the region” and “sound management,” steadily building its history by overcoming the challenges of each era. And the wartime context makes the outcome even more notable: many banks forced into consolidation during this period struggled to integrate and were later swallowed up. Shizuoka not only held together—it compounded.

By October 1961, the bank was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. That public milestone reflected something more important underneath: the merged entity had proven it could operate as one bank, build a branch network across the prefecture, and deepen relationships with the local businesses that would become its long-term moat.

The founding merger didn’t just create a new logo. It set the operating posture the bank would carry forward: loyal to the community, conservative where it mattered, and willing to innovate when others hesitated.

IV. Post-War Growth: Riding the Manufacturing Miracle

The decades after World War II remade Japan. Factories scaled, exports surged, and the country went from rebuilding to leading. Shizuoka Bank sat right in the middle of that story—geographically, yes, but also economically. If Shizuoka Prefecture was going to become one of Japan’s great making-things engines, it was going to need a bank that could fund machines, inventory, and expansion. Shizuoka Bank became that bank.

In those years, you can see the institution’s “two-DNA” culture at work. On one hand, it did the classic regional-bank thing extremely well: it built out a dense branch network across the prefecture and embedded itself in the daily life of communities and local businesses. On the other hand, it consistently acted bigger than a typical regional lender. It pushed into new lines of business early—establishing overseas branches, launching a securities subsidiary, executing share buybacks and cancellations, and even leaning into venture finance. Many of these would later become familiar moves across Japan’s regional banking sector. Shizuoka was doing them while they still felt unusual.

It also built alliances that expanded what it could offer without giving up independence. The bank maintained strong ties to Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group through joint-venture subsidiaries for credit cards and stock brokerage. In practical terms, that meant Shizuoka could bring big-bank-grade products to local customers, while staying rooted in Shizuoka’s relationship-driven model.

And as Shizuoka’s manufacturers went global, the bank followed. International operations began as a very specific kind of customer service: supporting local companies building supply chains and sales channels abroad. Over time, that footprint grew into a presence not just in Japan but also in the US, Singapore, Hong Kong, China, and Belgium. For a regional bank, offices in places like New York, Los Angeles, and Brussels weren’t normal. But Shizuoka’s clients weren’t normal either—they were competing in world markets, and they needed their bank to keep up.

Back home, the relationships deepened through the bubble years of the 1980s. The prefecture’s industrial web—auto parts suppliers, motorcycle component makers, and the countless firms orbiting brands like Suzuki, Honda, and Yamaha—ran on working capital, receivables, and equipment investment. Shizuoka Bank’s familiarity with manufacturing economics, from inventory cycles to capital equipment financing, became a real advantage. It wasn’t just lending into the region; it was underwriting a specific, complex way of doing business.

Then there’s a moment that underscores just how far this “regional” bank had traveled. Shizuoka Bank’s New York branch was located in the New York World Trade Center at the time of the September 11, 2001 attacks—and none of its employees were killed.

A year later, in 2002, rating agency Fitch praised the bank, noting that its “overall performance and strength indicators are superior to any of the major Japanese banks.” Coming on the heels of Japan’s banking crisis in the 1990s, that line carried extra weight. Many banks had been damaged by bubble-era excess, particularly speculative real estate lending. Shizuoka Bank’s more conservative heritage had kept it relatively disciplined, and it came through with its balance sheet largely intact.

By the end of the post-war growth era, Shizuoka Bank had quietly become something rarer than a strong regional lender. It had international reach, deep ties to globally competitive manufacturers, and a credit culture built to survive the hangover after the party.

V. The Lost Decades: Existential Crisis for Regional Banking

When Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1991, it didn’t just end a boom. It kicked off a long, grinding era of deflation and stagnation that rewired the economics of banking. And for regional banks—institutions built to live and die with the vitality of their home prefectures—the next few decades became an endurance test.

The pressures stacked quickly and then never really let up: shrinking demand for loans, an aging population, and a prolonged low-interest-rate environment that steadily squeezed profitability. Regional banks started hunting for “innovative solutions” not as a growth strategy, but as a survival strategy.

The numbers tell you why. Regional banks held about 40% of Japan’s commercial bank assets, but their core problem wasn’t scale—it was structure. Their customer base was aging and shrinking, and most had limited ways to diversify revenue beyond traditional lending.

Then came the interest-rate trap. A bank’s basic engine is the spread between what it pays depositors and what it earns on loans. When the Bank of Japan drove policy rates to zero—and eventually into negative territory—that spread didn’t just narrow. It collapsed. By the time COVID-19 hit, the benchmark rate sat at minus 0.1%. The BOJ didn’t begin raising rates again until 2024, the first hike in 17 years.

At the same time, Japan’s demographic shift hit regional markets hardest. In non-metropolitan areas, subdued economic activity became the norm, not the exception. And in rural communities, many small and medium-sized enterprises—often privately owned or sole proprietorships—began shutting down for a uniquely Japanese reason: there was no successor to take over the business.

That’s the doom loop in its purest form. Fewer people means fewer deposits and fewer borrowers. Fewer businesses means fewer loans and less fee income. And low rates mean thinner margins on whatever business is left. The traditional regional banking model—relationship deposits plus relationship lending—started to fracture.

Even when conditions improved for the sector as a whole, the gap between winners and losers widened. Profitability became more uneven than it had been a decade earlier. And without proactive strategies to deal with demographics, weaker banks risked missing the upside of any interest-rate recovery.

Many responded the only way they knew how: take more risk. More real estate exposure. Bigger securities books. More aggressive lending. In a spread-starved world, that kind of reach-for-yield was tempting—and often painful.

Shizuoka Bank, though, largely resisted that drift. Its conservative heritage acted like a governor on risk-taking. Its base of manufacturing clients offered steadier lending opportunities than regions overly reliant on agriculture or tourism. And crucially, management started treating technology less like an expense to minimize and more like a capability to build—investing in digital transformation while many peers still saw IT as a back-office cost center.

Meanwhile, consolidation loomed over the entire industry. Even before COVID-19, regional banks had begun merging to expand customer bases and improve efficiency. Shizuoka largely stayed out of the merger wave, choosing instead to rely on its own balance-sheet strength and selective partnerships. That decision mattered: it kept the organization flexible, and it left Shizuoka healthy enough to play offense later.

Because in this era, “sound” banks learned a new lesson. When traditional banking stops being reliably profitable, you don’t abandon the core—you extend it. Reinventing the business model, expanding into things the region actually needs, and building new engines like fintech and consulting services became the pragmatic path forward.

That’s the lane Shizuoka chose: broaden the franchise while protecting the discipline that kept it intact. And while many peers slid into a cycle of declining margins and escalating risk, Shizuoka was quietly preparing for the next phase—one where adaptation wouldn’t be optional, but the whole game.

VI. The Digital Transformation Pivot

While many regional banks treated technology like a necessary evil, Shizuoka Bank started treating it like strategy. Beginning in the mid-2010s, the bank kicked off a digital transformation that would become a major reason it stayed resilient while the rest of the sector felt increasingly cornered.

The starting point wasn’t pretty. Core systems that were, in some cases, more than 40 years old made change slow and expensive. And even worse: the bank’s data lived in silos. Information was scattered across separate systems, which meant getting a clean view of customers, risks, or opportunities was harder than it should have been—exactly the opposite of what you want in an era of thin margins.

So in its 13th Mid-term Business Plan, Shizuoka set a clear priority: “the reform of sales operations using retail channels and IT infrastructure.” That might sound like planning-document language, but the intent was straightforward: modernize how the bank served customers, and rebuild the plumbing underneath it.

A key move was partnering with Fujitsu to implement FrontSHIP, a front-end services platform built for financial institutions. The idea was to upgrade both the in-branch experience and the remote, digital experience at the same time—face-to-face and non-face-to-face channels moving forward in parallel. FrontSHIP was designed to create new customer touchpoints through digital channels and improve the customer experience, rather than simply putting old processes onto a screen.

This was also a competitive necessity. Shizuoka’s view was that branches would still matter for local banks—but digital was changing the battlefield. Fintech players and other non-bank entrants were increasingly winning customer attention through apps, integrations, and partnerships. To keep up, banks needed modern front-end channels, including internet banking that could support open innovation and collaboration with other industries.

Crucially, Shizuoka didn’t frame digital as “branches versus apps.” It framed digital as reach. Things that used to require a trip to a branch could be handled on a smartphone. Customers could choose the channel that fit the moment, without falling into inconsistent service or disconnected systems. That omnichannel approach is table stakes now, but for a regional bank building it early, it was a real differentiator.

FrontSHIP also supported improvements to the bank’s in-branch front office hub system, which had been implemented starting in May 2017, while extending similar services into digital finance channels on smart devices. The goal was equivalence: customers shouldn’t feel like they were getting “the lite version” just because they weren’t sitting across from a teller.

Then came the deeper layer: data.

Leveraging Snowflake’s capabilities, Shizuoka Financial Group built S-hare, a centralized data platform intended to unify the organization’s information. In practice, that meant integrating data from core banking systems, CRM tools, and external datasets, and storing structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data in a single repository—a shared source of truth the bank could actually use.

Once you have that foundation, the payoffs compound. The bank could analyze customer behavior across channels instead of guessing. Models could incorporate richer information. Marketing could become more personalized and more effective, because it finally had the data backbone to support it.

By the time Shizuoka shifted to a holding company structure in October 2022—and adopted the motto “Expanding dreams and prosperity together with our region”—it wasn’t trying to modernize from scratch. It had already built much of the technology base that many regional competitors still lacked.

And that’s the key point: the digital investments weren’t a side project. They set off a virtuous cycle. Better data improved decisions. Better experiences improved retention. Greater efficiency created room to invest again. Step by step, Shizuoka was turning what used to be a back-office cost center into a durable advantage—and proving that even a traditional regional bank could use cloud and data to compete in the digital age.

VII. The 2022 Holding Company Restructuring

By the time Shizuoka finished rebuilding its digital foundation, it was ready for the next move: changing the shape of the organization itself.

On October 3, 2022, Shizuoka made a structural shift years in the making. Through a sole-share transfer, Shizuoka Financial Group, Inc. became the holding company and the wholly owning parent, with Shizuoka Bank positioned as its core operating subsidiary. The transition was carried out subject to shareholder approval at the June 17, 2022 Annual General Meeting and the necessary regulatory approvals.

The “why” wasn’t abstract. Management tied the change directly to the structural headwinds pressing on every regional bank: demographics moving the wrong way, fewer borrowers, and a long-term decline in demand for funds driven by a low birth rate and an aging population. In a business where the old model was steadily being compressed, they wanted a structure that could support new engines of growth.

And this wasn’t just a new corporate nameplate.

Following the incorporation of the holding company, Shizuoka moved to reorganize five key group relationships: four consolidated subsidiaries—Shizugin Management Consulting Co., Ltd., Shizugin Lease Co., Ltd., Shizuoka Capital Co., Ltd., and Shizugin TM Securities Co., Ltd.—plus one equity-method affiliate, Monex Group, Inc.

So why does corporate structure matter so much for a regional bank?

A big part of the answer is regulatory. Japan’s Financial Services Agency revised the Banking Act effective November 2021, explicitly expanding what banks could do beyond traditional lending and deposits. The updated rules allowed banks to engage in ancillary businesses such as consultation services, data analysis, and daily support services for elderly customers. At the same time, Japan began easing its approach relative to international rules, relaxing the business scope in IT-related businesses and in operations that contribute to building a sustainable society and regional revitalization.

A holding company structure turns those permissions into usable strategy. Businesses that can feel cramped, risky, or operationally messy inside a bank charter—management consulting, real estate advisory, IT services, human resources placement—can be housed in dedicated subsidiaries. That makes them easier to build, easier to partner around, and easier to manage without diluting what a bank is supposed to be great at: trust, risk control, and stability.

Shizuoka wrapped the shift in a clear internal narrative. The first medium-term business plan under the new structure was titled, “Xover: Clearing the Way to a New Era,” a statement of intent to push forward in an uncertain environment and co-create value with stakeholders by transcending traditional boundaries between fields and categories—including, as they put it, “future generations.”

The benefits showed up in the mechanics of running the group. The holding company enabled more deliberate capital allocation across the portfolio, and the group pointed to growing contributions from businesses outside the bank itself: profit contributions from group companies other than Shizuoka Bank increased by JPY2.4 bn year over year as cooperation across the group deepened.

But the most underappreciated advantage may have been governance. By separating holding company leadership from day-to-day bank operations, Shizuoka created room for long-term strategic direction to be set at the top, without being constantly pulled into operational gravity. It’s a model Japan’s megabanks adopted long ago. For regional banks, it’s been slower and rarer—which is exactly why, for Shizuoka, it became a quiet inflection point.

VIII. The Startup and Venture Finance Strategy

In an industry that’s wired to avoid surprises, Shizuoka Bank’s move into venture is one of its most distinctive bets—and one of the clearest expressions of that “prudence plus challenge” DNA.

Over time, the group invested more than 30 billion yen across 41 venture capital funds, collectively backing around 1,100 startups. On top of that, the bank extended nearly 32 billion yen in venture debt—growth capital—to about 140 companies.

Step back and that’s the headline: a regional bank headquartered outside Tokyo put roughly ¥62 billion to work in the startup ecosystem through a mix of fund investments and venture lending. That’s not what most people expect from “regional banking” in Japan.

The strategic logic is also more deliberate than it might look at first glance. Traditional small business lending was being squeezed by demographics and slow growth. Startups, by contrast, offered a new kind of customer relationship—one that could start small, but scale into meaningful deposits, lending, and advisory work if the bank got involved early.

And Shizuoka’s approach wasn’t just to write checks. The bank framed its role as connective tissue: partnering with startups and acting as a bridge between emerging technology and the region’s incumbent industries.

That’s especially important because of a geographic imbalance the bank openly acknowledged. Japan’s startup gravity sits overwhelmingly in Tokyo. But Shizuoka’s customer base—manufacturers across the prefecture—needed access to new tools, new processes, and new business models. Shizuoka Bank positioned itself as the connector between those two worlds.

In 2021, it made that ambition concrete by opening a representative office in Silicon Valley. The goal was to strengthen ties with local venture firms and startups, invest in VC funds, and place personnel on the ground to gather information and deepen collaboration—essentially building an on-ramp from global innovation back to regional Japan.

If Silicon Valley was the scouting mission, Tech Beat Shizuoka became the home-field arena. Since 2019, the bank has hosted a large-scale matching event called “Tech Beat Shizuoka.” In 2024 it brought in 139 participating startups, and in 2025 participation rose to around 178.

Organized by the TECH BEAT Shizuoka Executive Committee, the event’s purpose is straightforward: generate innovation through business matching between Shizuoka Prefecture companies and startups. Across nine events, participation has topped 20,000 people, with more than 1,700 business meetings held.

The venture debt program is the other key piece here. Startups are exactly the kind of borrower traditional banking tends to reject: limited collateral, short operating histories, and financials that don’t fit standard underwriting. Venture debt sits in the middle. It provides capital to companies that have already raised equity from sophisticated VCs, giving them runway or financing flexibility without immediate dilution.

All of this points to a deeper goal than “doing VC.” It’s about reshaping the region’s industrial future. These initiatives have been positioned as catalysts for change across legacy sectors—auto parts, construction, agriculture—that are central to Shizuoka’s economy.

And nowhere is that need more urgent than in manufacturing. In Shizuoka Prefecture, manufacturing accounts for roughly 40% of regional GDP, but it’s also facing a structural shift as the auto industry transitions to electric vehicles. According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, nearly half of internal combustion engine components may be replaced in the EV era.

For a bank whose long-time core clients include auto parts makers, that’s not an abstract trend—it’s an existential threat to parts of its customer base. By helping traditional manufacturers connect with startup technologies, Shizuoka Bank is trying to future-proof the region it depends on, while also positioning itself to bank the startups that make it through the gauntlet and emerge as the next generation of winners.

IX. International Strategy and the Philippines Partnership

Shizuoka Bank’s international footprint has always been downstream of its customer base. When your home region is packed with exporters and supply-chain manufacturers, “regional” doesn’t stay regional for long. Over the years, the bank built a presence not only in Japan, but across key overseas markets including the US, Singapore, Hong Kong, China, and Belgium—initially to serve Shizuoka companies as they expanded into global trade and production networks.

But over time, that overseas strategy widened from following clients abroad to solving a newer, more urgent problem for those same clients back home: labor.

In February 2025, BDO Unibank Inc. expanded its partnership with Shizuoka Bank, building on a relationship that began in 2016. BDO said it signed a comprehensive memorandum of understanding to deepen the business alliance—supporting Japanese firms operating in the Philippines’ diverse markets, and creating more pathways for trade and investment between the two countries.

The most striking part of the partnership is how directly it targets Japan’s workforce crunch. As Japan increased its demand for skilled Filipino workers, BDO and Shizuoka Bank positioned the alliance to support overseas Filipino workers heading to Japan—including technical intern trainees, specified skilled workers, and professionals employed in Japan.

That support starts before a worker even boards a plane.

Relocation to Japan requires upfront capital—training fees, travel, and initial living expenses. Historically, many workers covered those costs with high-interest borrowing, often from informal lenders. Through the partnership, Shizuoka Bank and BDO moved to change the default: helping workers access fairer financing, backed by an appropriate guarantee structure, before they come to Japan.

It’s a classic Shizuoka move: start with a regional economic reality and then build a financial product that makes the whole system work better. Shizuoka’s economy is still anchored by manufacturing—machinery, automotive parts, electronics—alongside industries like green tea and fishing. Manufacturers need people. The Philippines has people seeking opportunity. A bank that can responsibly facilitate that flow doesn’t just do something socially useful; it strengthens the operating capacity of the very companies that underpin its home-region economy.

And it fits with Shizuoka Bank’s scale and reach. The bank operates 177 branches and 26 sub-branches, extending beyond Shizuoka Prefecture into Japan’s three major economic hubs—Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya. That network matters because once workers arrive and settle, the relationship can become longer-term banking business: accounts, remittances, savings, and eventually broader financial services as lives and careers take root in Japan.

X. Navigating the Interest Rate Regime Change

After decades of deflation-fighting monetary policy, Japan entered a new era: interest rates started moving up again.

At its December meeting, the Bank of Japan raised its key short-term policy rate by 0.25 percentage points to 0.75%, the highest level since September 1995. It was the central bank’s second hike of the year, following a similar increase in January—another clear step away from the ultra-loose stance that defined modern Japanese banking.

For regional banks that spent years learning how to survive on zero—and even negative—rates, this shift is both a tailwind and a stress test.

On the upside, higher rates should lift the basic engine of banking: earning more on loans relative to what you pay on deposits. Shizuoka Financial Group’s recent results showed that benefit. In FY2024, consolidated net income hit a record JPY74.6 bn, up JPY16.9 bn year over year, supported by steady growth in core earnings.

In the domestic business segment, performance remained solid, driven largely by better yields on domestic lending as yen interest rates rose—helping push net interest income up JPY19.5 bn year over year.

But the other side of rising rates is that customer behavior changes—and not always in ways banks like.

With prices rising, more households have been drawing down savings to cover everyday costs. In Shizuoka—the group’s core market—there’s also capital flowing out toward the Tokyo metropolitan area, in part due to intergenerational asset transfers. At the same time, money has been moving toward high-interest internet banks and into NISA accounts, pulling deposits away from traditional institutions and causing some regional banks to see personal deposits decline.

Shizuoka’s response is one of the clearest expressions of its dual heritage: conservative about what matters, inventive about how to compete. The focus is on cultivating “sticky deposits.” That means prioritizing everyday accounts—payroll, pension deposits, and business accounts—where local presence, service, and long-standing relationships still provide a real edge.

The point is simple: competing on rate alone is a losing game for regional banks. Internet banks can offer higher deposit rates precisely because they don’t carry dense branch networks. Regional banks have to win on relationship—the daily touchpoints, the knowledge of local conditions, the trust built over decades of showing up.

There’s also a subtler tension in this new environment. Even as policy normalization opens the door to higher net interest income, regional banks have often been slower than their urban counterparts to raise loan rates, choosing to support local businesses rather than maximize margins immediately.

That trade-off reflects the founding principle Shizuoka has repeated for decades: commitment to the region. It can mean giving up some short-term upside. But it also reinforces the kind of loyalty that keeps deposits and relationships in place when the cycle inevitably turns again.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To see where Shizuoka Financial Group can really win—and where it can’t—we need to look past any single strategy and zoom out to the forces shaping the whole playing field.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Digital-only banks and fintech companies have lowered the cost of launching basic banking services. As we’ve seen, money has been flowing toward high-interest internet banks and into NISA accounts, training customers to shop around more aggressively than traditional regional banking ever assumed.

There’s also a uniquely Japanese wrinkle: SBI Holdings has been actively investing in regional banks, sometimes looking like a disruptor, sometimes like a potential ally. But even with all this change, banking isn’t a pure software business. Licensing and regulation still matter, and the kind of relationship-heavy, complex commercial banking Shizuoka does—especially with SMEs—still benefits from trust and physical presence. That acts as a real, if imperfect, moat.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

In banking, the primary “input” is money—and the Bank of Japan sets the terms. Capital is largely fungible, and changes in policy drive the industry’s baseline cost structure more than any individual supplier ever could.

On the technology side, vendors like Fujitsu and Snowflake are important partners, but not single points of failure. If one relationship becomes problematic, there are alternatives. Labor is the more meaningful constraint: Japan’s workforce is tightening. Still, Shizuoka’s established regional footprint and existing talent base give it more stability than a new entrant trying to staff up from scratch.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

This one splits cleanly by customer type.

For SMEs in regional markets, choice is often limited. Megabanks generally can’t serve smaller local businesses economically, and online banks don’t have the on-the-ground capability for nuanced underwriting or relationship-based advisory. That gives Shizuoka leverage.

Retail customers are a different story. Depositors have become more rate-sensitive and more willing to move money with a few taps. And as rates rise, the competitive pressure intensifies: the economics improve for banks through higher spreads, but the cost of keeping deposits rises too. Regional banks can be especially exposed here because they rely heavily on retail deposits and don’t have the same diversification and shock absorbers as the megabanks.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The bank no longer competes only with other banks. Direct lending platforms, crowdfunding, and corporate bond markets can replace traditional borrowing in the right circumstances. Payment apps can strip away valuable transaction relationships. And on the investment side, low-cost index funds have pulled asset management toward products that generate less fee income for intermediaries.

This is the unbundling of finance in real time: customers increasingly assemble their financial lives from best-in-class point solutions. That forces banks to defend their role, not assume it.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Finally, rivalry is intense—and structurally so. Japan’s banking market remains fragmented, and profitability has been low for a long time. S&P Global Ratings has flagged that this persistence of low profitability poses a risk to the stability of Japan’s banking system.

Layer on top of that megabanks pushing into regional markets, ongoing consolidation pressure, and a shrinking pool of attractive opportunities, and you get the core dynamic: too many institutions chasing too little high-quality growth. In that environment, strategy matters—but so does starting position. Shizuoka’s challenge is to keep turning its regional strength, digital capability, and diversification into a defensible edge while the competitive vice keeps tightening.

XII. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter tells you how brutal the battlefield is. Hamilton Helmer tells you something even more useful: what, if anything, can actually protect a business from getting worn down over time. So let’s run Shizuoka Financial Group through Helmer’s Seven Powers and see where durable advantage shows up—and where it doesn’t.

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Shizuoka is one of Japan’s largest regional banks, but it’s still a different animal than the megabanks. Where it does get scale is inside its own walls: the holding company structure lets the group share services across 14 entities—technology, compliance, and back-office functions—so each business doesn’t have to rebuild the same infrastructure from scratch. That’s meaningful, but in banking, the deepest scale advantages usually come with a national or global footprint, and Shizuoka isn’t trying to be that kind of institution.

2. Network Economies: MODERATE-STRONG (Regional)

In Shizuoka Prefecture, relationships are an asset class. Deep ties with local SMEs create information advantages that are hard to copy—who’s expanding, who’s struggling, who’s facing succession risk, who can actually execute on a growth plan.

The startup push adds a second network layer. With initiatives like Tech Beat Shizuoka, VC fund investments, and venture debt, the group can become more valuable as a connector the more participants it brings into the ecosystem. More startups and partners mean more matching opportunities, which attracts more startups and partners.

And there’s a third layer: as manufacturing clients expand overseas, the need for international services increases too. The bank’s role as a trusted home-base institution becomes more valuable the farther its customers travel.

3. Counter-Positioning: STRONG

This is where Shizuoka’s advantage gets sharp.

Megabanks generally can’t serve small regional SMEs economically; their cost structures and operating models aren’t built for it. Digital banks can win on convenience and rate, but they don’t have the physical presence or relationship depth needed for complex advisory and underwriting. And many conservative regional banks simply don’t want to play in venture capital, startup engagement, or venture debt the way Shizuoka has.

This is the space Shizuoka has carved out: trusted and local enough to do relationship banking, but ambitious enough to expand into new models that incumbents avoid.

Corporate Philosophy to "expand dreams and affluence with our community" shows our attitude as a financial group that was born and has grown in the region to aim to coexist and co-prosper with the local community.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

Shizuoka’s “sticky deposits” idea isn’t just good tactics—it’s switching-cost strategy. Everyday accounts like payroll, pension deposits, and business accounts are embedded into routines. Once you’re running your financial life through a bank, moving isn’t just a click; it’s a project.

For SMEs, the glue is even stronger: loan covenants, working capital facilities, payment processing, and years of accumulated institutional knowledge. And in multi-generational family businesses, switching costs are emotional as well as practical—relationships aren’t easily replaced.

The weak spot is retail: digital channels make comparison and switching easier than they used to be, which is why Shizuoka keeps emphasizing accounts tied to daily life, not just savings.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Shizuoka Bank’s brand carries roughly eight decades of regional trust. It’s not a national name, but within Shizuoka Prefecture it signals stability, local commitment, and a deep understanding of the region’s manufacturing economy.

Corporate Philosophy to "expand dreams and affluence with our community" shows our attitude as a financial group that was born and has grown in the region.

That said, this is regional brand power, not the kind of brand that automatically travels across Japan.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

If you want a true “can’t be replicated quickly” asset, this is it. The bank’s local knowledge—how the manufacturing ecosystem fits together, which firms supply whom, which businesses are quietly thriving, which are vulnerable because of succession challenges—builds over decades. New entrants can bring money and software. They can’t conjure that map of relationships and risk overnight.

7. Process Power: EMERGING

Shizuoka’s digital transformation and centralized data platform create the possibility of process power: better decision-making, faster product iteration, and lower cost to serve. The venture debt program also forces the bank to develop specialized underwriting processes that most traditional lenders never build.

As they continue their digital transformation journey, Shizuoka Financial Group stands as a testament to how traditional businesses can leverage the power of data and cloud technology to thrive in the digital age. But process power has to prove itself through repeated cycles. The ingredients are here; the durability will be measured over time.

XIII. The Strategic Playbook: Lessons for Institutional Survival

Shizuoka Financial Group’s story isn’t just a Japan story or a banking story. It’s a playbook for how an incumbent survives when the industry math turns against it.

Lesson 1: Cultural Fusion Creates Resilience

The 1943 merger didn’t just create scale. It created balance. Shizuoka Sanjyu-go Bank brought discipline and a bias toward stability. Enshu Bank brought the “Yaramaika” instinct to try things first and iterate fast. Eight decades later, that productive tension still shows up in the strategy: innovate, but don’t gamble the franchise.

The broader lesson is simple: in a transformation, you don’t want cultural uniformity. You want a system where prudent people and ambitious people are forced to build the future together.

Lesson 2: Geography Can Be Strategy

Shizuoka’s location between Tokyo and Osaka, plus an economy anchored by manufacturing, gave it a customer base with real productive activity behind it—not just consumption, not just real estate cycles. That matters for a regional bank. It shapes the quality of borrowers, the stability of deposits, and the kinds of services customers actually need.

The takeaway: stop treating geography as a constraint and start treating it as an edge. If your region has a distinctive economic engine, build the institution around serving it better than anyone else can.

Lesson 3: Transform Before You’re Forced To

A lot of legacy organizations modernize only once the pain becomes unbearable. Shizuoka moved earlier. It rebuilt its digital foundation while it still had the profitability and bandwidth to do it well. The holding company shift wasn’t a rescue maneuver; it was a way to unlock flexibility before flexibility became existential. The venture and startup push wasn’t “Plan B.” It was a new growth lane built alongside the core.

In declining or maturing industries, timing is everything. The best transformations aren’t reactive. They’re done while you can still choose your own terms.

Lesson 4: Regional Banks as Ecosystem Orchestrators

Shizuoka’s most interesting reinvention is role-based: from lender to connector. The group has positioned itself as a bridge between startups and regional companies—bringing new technologies to legacy industries, and bringing real customers and real use cases to emerging companies.

That shift matters because it reframes the value of a regional bank. In a world where “just lending” gets commoditized, being the institution that can convene partners, match talent and technology, and help a region adapt can become the most defensible service of all.

Lesson 5: The “Sticky Deposits” Insight

As rates rise, competing on price becomes a trap. Internet banks can offer higher rates because they don’t carry the same physical footprint. Shizuoka’s answer has been to compete where a regional bank still has an unfair advantage: everyday relationships.

Payroll accounts, pension deposits, and business operating accounts aren’t just balances; they’re habits. They’re workflows. They’re trust. And when a bank wins those daily touchpoints, it earns something more durable than a promotional rate.

The principle is timeless: don’t fight on the battlefield your competitors designed. Fight on the one your strengths make winnable.

XIV. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bear Case

Japan’s demographic headwinds aren’t cyclical. They’re structural, and they’re getting worse. The country’s population is projected to decline across virtually every prefecture by 2035, with rural areas hit hardest. Fewer working-age people means fewer new households, fewer entrepreneurs, fewer borrowers—and a smaller base of deposits to fund the system. For regional banks, that’s not a temporary slump. It’s the backdrop.

Even Shizuoka’s greatest historical advantage—its manufacturing-heavy economy—comes with a new kind of risk. The shift to EVs threatens to make large swaths of internal combustion engine components less relevant over time. If a meaningful portion of Shizuoka’s auto parts ecosystem gets stranded by that transition, some of the bank’s core lending relationships could face real stress.

Higher interest rates, meanwhile, are a double-edged sword. They can lift margins going forward, but they also expose the legacy of the low-rate era. Bond portfolios built when yields were near zero can carry unrealized losses as rates rise. If the bank—or the system—turns out to be more interest-rate sensitive than expected, the “return of margins” could arrive with unexpected balance-sheet volatility.

And competition isn’t slowing down. Digital-only banks and fintechs keep training customers to expect better UX and better rates. Megabanks continue pushing outward into regional markets. In that world, Shizuoka’s branch network is both an asset and a liability: it anchors trust and relationships, but it also carries a fixed-cost base that digital competitors simply don’t have.

The Bull Case

The same moves that look defensive on the surface are also what make Shizuoka one of the best-positioned regional banks in Japan. The 2022 holding company restructuring wasn’t just corporate housekeeping—it created a platform for exactly the diversification the industry needs, giving the group more freedom to build businesses adjacent to traditional banking. And it’s already showing up in results: FY2024 consolidated net income reached a record JPY74.6 bn, up JPY16.9 bn year over year, on steady growth in earnings from core businesses.

The venture and startup strategy adds something most regional banks don’t have: optionality. Shizuoka has supported around 1,100 startups through VC fund investments, and it has extended venture debt to companies that don’t fit traditional underwriting. If even a small share of those startups becomes enduring companies, Shizuoka has an early seat at the table—relationships that can turn into decades of lending, fees, and treasury business.

And while manufacturing faces disruption, it also has the motivation—and in many cases the balance sheet—to invest its way into the next era. The banks that win here won’t be the ones that merely lend. They’ll be the ones that help clients transform: connecting them to new technologies, supporting M&A and partnerships, and structuring capital solutions that match a changing industrial reality. For Shizuoka, that kind of support doesn’t replace relationships—it makes them harder to unwind.

Finally, interest-rate normalization could be a structural tailwind, not a brief sugar high. After decades of margin compression, even modest rate increases can have outsized impact on profitability. And management has already been leaning into that momentum: the group revised its forecast consolidated net income upward by JPY5.0 bn, and also revised dividend per share upward by JPY6, citing steady progress in core earnings—centered on net interest income.

In other words: the bear case is that Japan’s regional banking math keeps getting tougher. The bull case is that Shizuoka has quietly built more ways to win than “regional banking math” alone.

XV. Key Metrics for Ongoing Monitoring

If you’re watching Shizuoka Financial Group from the outside, there are three signals that tell you whether the strategy is working—or whether the headwinds are winning.

1. Net Interest Margin Trend

In a world where Japan’s interest-rate regime is finally shifting, net interest margin is the clearest scoreboard. Track it quarter to quarter to see whether Shizuoka is actually capturing the upside from higher rates—repricing loans fast enough—without giving it all back through higher funding costs. This spread between what the bank earns on lending and what it pays for deposits is the simplest, most fundamental engine of bank profitability.

2. Core Deposit Ratio

The “sticky deposits” strategy only matters if the deposits really stick. The clean way to test that is to monitor how much of the deposit base comes from everyday accounts—payroll, pension, and business operating accounts—versus more rate-sensitive savings. If core deposits start sliding, it’s usually the earliest warning that competition from internet banks and megabanks is pulling customers away.

3. Non-Banking Subsidiary Contribution

The holding company structure is only valuable if it changes the earnings mix. Group companies other than Shizuoka Bank increased their profit contribution by JPY2.4 bn year over year, and that’s exactly what management wants: more growth coming from consulting, leasing, securities, and other adjacent businesses. Over time, the key metric is the share of consolidated profits generated outside the bank itself—because that’s the best measure of whether diversification is becoming a real second engine, not just an organizational chart.

XVI. Conclusion: A Template for Institutional Transformation

Shizuoka Financial Group’s story pushes back on the easy narrative that Japan’s regional banks are destined for slow decline. Across eight decades—through war, boom, bust, deflation, and now a shifting rate regime—the institution has shown that strategy, culture, and well-timed reinvention can bend even brutal industry math.

It starts in 1943, with a wartime merger that accidentally created a better-designed bank for an uncertain world. Shizuoka Sanjyu-go Bank contributed discipline and ballast—the instincts that kept speculation from becoming a franchise-threatening habit. Enshu Bank contributed the challenger’s mindset—the local “Yaramaika” spirit that made trying new things feel natural rather than dangerous. Put together, they formed an organization that could innovate without losing control of risk.

Then came Japan’s lost decades, when the core economics of regional banking began to fail. Shizuoka didn’t escape the pressure—but it responded differently. It stayed anchored in credit discipline while others reached for yield. It invested in technology while many competitors treated IT as a cost center. And it gradually reimagined what a regional bank could be: not just a lender, but a connector—linking local companies to capital, capability, talent, and new technology.

The 2022 shift to a holding company structure was the institutional version of that same instinct. It wasn’t a rescue move. It was a way to create room—organizationally and strategically—to build businesses that don’t fit neatly inside a traditional bank charter. From venture investments to international partnerships to modern data and digital platforms, the group used that flexibility to widen its options without abandoning the core.

Without losing sight of the essence of being a "regional financial institution that is essential to the community," we will strive to further deepen the relationship of trust with our customers through group-wide efforts to provide solutions to all the issues faced by the community and our customers.

None of this makes the road ahead easy. Demographics won’t reverse on optimism. Manufacturing disruption will create both winners and losers among the bank’s long-time clients. Digital-first competition will keep raising customer expectations. And higher interest rates, while helpful for margins, also bring new balance-sheet and funding dynamics that banks haven’t had to manage in a generation.

But Shizuoka enters that future from a position of strength rather than fragility: record profits, a more diversified earnings mix, a modernizing technology foundation, and—most importantly—a cultural DNA that has proven it can adapt repeatedly without losing its identity.

For investors, the bet is straightforward: that institutional resilience can be an edge, and that a well-managed regional bank can still compound value even as the industry consolidates and the country ages. The outcome isn’t guaranteed. But if any regional bank has earned the benefit of the doubt in navigating Japan’s structural transformation, it’s Shizuoka.

And it comes back to that old Hamamatsu phrase, still echoing inside a modern financial group: “Yaramaika”—“Let’s give it a try.” Not as recklessness. As disciplined optimism. In an industry where most stories end in consolidation or retreat, Shizuoka Financial Group is trying to write a different ending.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music