Sumitomo Metal Mining: From Feudal Japan's Copper Empire to Tesla's Battery Supply Chain

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

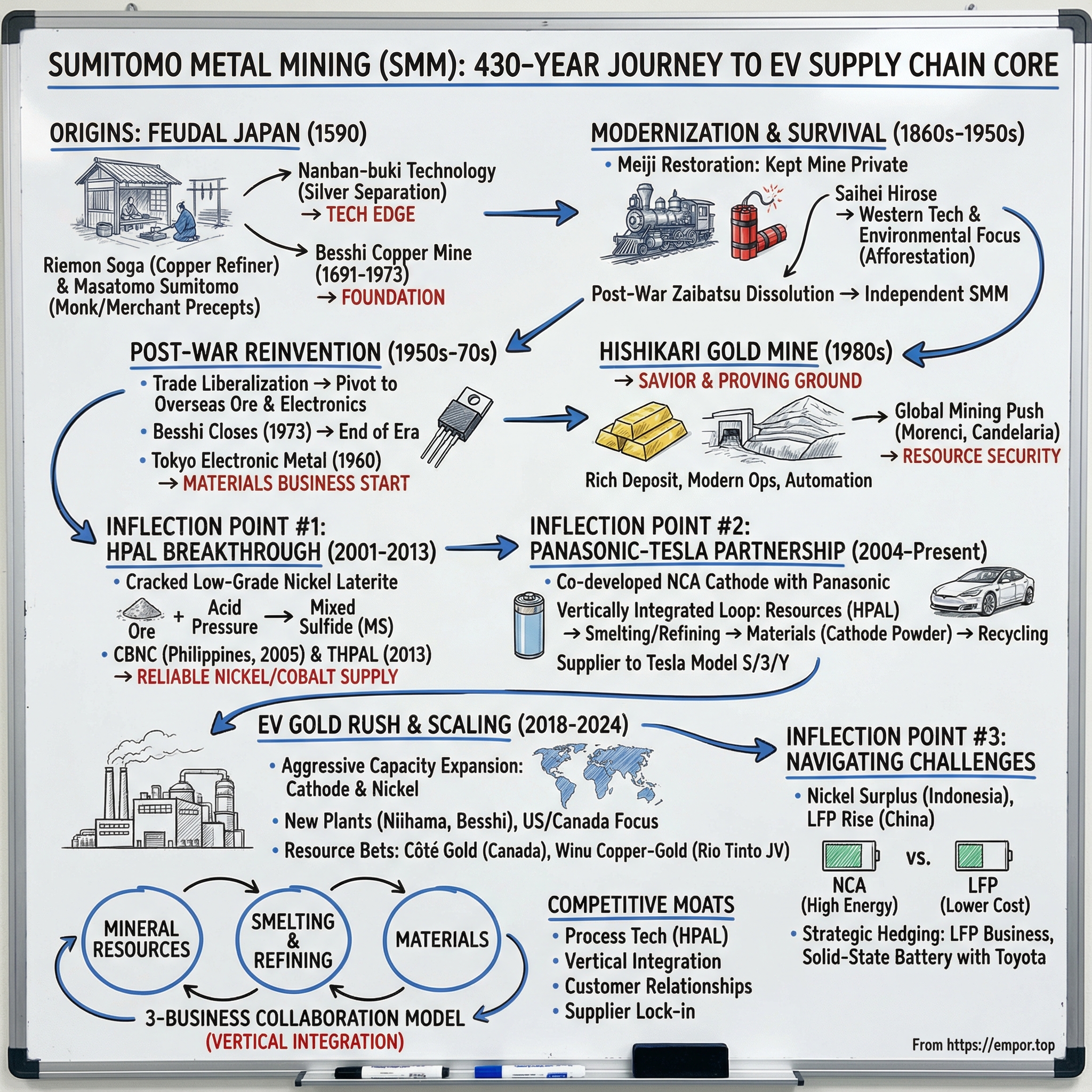

What if I told you the company helping power Elon Musk’s Teslas started with a Buddhist monk who turned copper merchant in 1590—and, in the process, helped create one of the longest-running industrial enterprises on Earth?

This is the story of Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Ltd. (TSE: 5713). For more than 430 years, it’s kept finding the next seam to mine—sometimes literally, sometimes strategically. It began in feudal Japan with copper smelting, grew into zaibatsu-era industrial muscle, survived post-war upheaval and the shutdown of its historic domestic mines, and eventually reemerged as a quiet but critical player in the electric vehicle supply chain.

The throughline is how Sumitomo Metal Mining is built. Its edge isn’t one breakthrough product; it’s a system: three businesses—Mineral Resources, Smelting & Refining, and Materials—designed to work together from ore in the ground to advanced materials in the battery. That end-to-end loop creates a kind of industrial self-reliance: more control over inputs, more ability to scale, and more leverage when the world decides it suddenly needs a lot more of one particular metal.

And right now, the world needs nickel. Sumitomo Metal Mining supplies nickel-based cathode materials for Panasonic’s lithium-ion batteries—the cells used in Tesla EVs. In the energy transition, the critical minerals supply chain is the new oil. And SMM sits unglamorously, but consequentially, near the center of it.

But this isn’t a straight-line “EV boom” story. SMM has warned that the global nickel market is heading into surplus, driven largely by rapid production growth in Indonesia. At the same time, cheaper lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries are taking share—especially in China—pressuring demand for the nickel-heavy chemistries where SMM has historically been strongest. Add in environmental controversy around its Philippine operations, and the modern challenge comes into focus: how does a 400-year-old mining-and-materials company keep its footing as the ground shifts beneath it again?

That’s what this episode is about. We’ll follow SMM through three inflection points: the HPAL technology breakthrough that made low-grade laterite nickel economically usable; the Panasonic partnership that put SMM into the heart of Tesla’s battery ecosystem; and today’s strategic crossroads, as battery chemistry shifts force the company to hedge its bets. Because if you want to understand who wins the EV revolution, you don’t just look at the carmakers—you look at the decades-long, capital-heavy bets that built the supply chain underneath them.

II. The Sumitomo Origins: A 400-Year Foundation

Picture Kyoto in 1590. Toyotomi Hideyoshi has consolidated power. Japan’s long isolation from the outside world is still decades away. And in a small workshop, a 19-year-old entrepreneur named Riemon Soga opens a copper refining shop—right as a former Buddhist monk, Masatomo Sumitomo, is being forced into reinvention. His sect has been dissolved by the Tokugawa authorities. The calling that once defined his life is gone, and he needs a new path.

That pivot—part spiritual, part practical—is where the Sumitomo story begins.

Masatomo becomes a bookseller and an apothecary. Not because commerce is the point, but because it’s the vehicle. He wants to keep spreading his late master’s teachings to ordinary people, and he wants work that, in his mind, eases suffering. So he publishes. He sells medicine. And he writes down a set of “founder’s precepts” that the Sumitomo companies still preserve today.

They read less like a business plan and more like a code. Run the house with integrity and sound management. Keep foresight and flexibility. Under no circumstances pursue easy gains or act imprudently. Sell nothing on credit. Don’t buy goods below the market price without knowing their origin—assume they’re stolen. Don’t lose your temper. Don’t speak harshly, no matter what the other party says.

It’s an unusually specific blueprint for a merchant house. And it’s the cultural DNA that will keep resurfacing, century after century, whenever Sumitomo has to make a hard choice.

But the leap from ethics to industrial might comes through Masatomo’s brother-in-law: Riemon Soga, the young refiner. Riemon becomes obsessed with a technical problem that, at the time, separates real fortunes from wasted opportunity. Foreign traders talk about a way to separate silver from copper. Riemon experiments again and again, and eventually lands on a process that becomes known as nanban-buki—a method that separates silver from copper during refining.

The breakthrough mattered because, before nanban-buki, Japan exported copper that still contained valuable silver. In other words: they weren’t just shipping copper. They were quietly giving away silver, too. By pulling those metals apart, Sumitomo could capture far more value from the same ore. That competitive advantage—secured sometime between 1596 and 1615—helped establish a profitable base that wasn’t just about volume. It was about know-how.

Then the family structure locked it in. Riemon’s son, Tomomochi, married Masatomo’s daughter and was adopted into the Sumitomo household. Tomomochi is the builder—the person who turns these pieces into a lasting merchant house. He carries both influences: the technical ambition of his biological father, and the disciplined worldview of his adoptive father. Together, they create a house that is simultaneously values-driven and engineering-minded—a combination that turns out to be incredibly durable.

The pivotal moment arrives a century later, in 1690. Large outcrops of copper ore are discovered on the southern slopes of the Akaishi Mountains in Ehime Prefecture. Sumitomo develops what becomes the Besshi copper mine—and once the first shaft goes in, the business changes shape. This is no longer just about refining copper bought from someone else. Sumitomo shifts into being a true resource company: digging, processing, and scaling an industrial operation from the ground up.

Besshi develops fast. After operations begin in 1691, the mining conditions prove excellent. Within a few years, a community forms around the site, with several thousand people engaged in mining and refining. By the end of that decade, Besshi is producing copper at a scale that puts it among the world’s foremost sources.

Geologically, it’s a monster by Japanese standards: a deposit stretching roughly 1.8 kilometers, running through the mountain at a steep angle, from high above sea level to far below it. Practically, that meant decades of work—and then centuries.

Besshi operates for 283 years, from 1691 until 1973, producing roughly 700,000 tons of copper over its life. During the Edo era, copper is a crucial export, and Japan is one of the world’s largest copper-producing countries. Sumitomo’s output supports the broader economy. Then, from the start of the Meiji era onward, copper becomes a foundational input for modernization and industrialization. Sumitomo, as Japan’s only private mining company, plays an outsized role in supplying it.

And this is where the broader Sumitomo empire starts to form. Mining success pulls in new adjacent businesses. Western technologies boost production further and spark more related ventures. Commercial activity in Osaka grows into finance, then into banking. Warehousing operations spun out of finance become independent. Over time, Sumitomo develops into a modern zaibatsu—anchored by mining, manufacturing, and finance.

This ancient history matters for investors today because it explains how the company makes decisions when the easy path is right there. The Sumitomo Business Spirit—trust, long-term thinking, technological excellence—didn’t appear later as branding. It was baked in from the start. The precepts against “pursuing easy gains” help explain why SMM was willing to spend years refining difficult process technology like HPAL when others gave up. The emphasis on “foresight and flexibility” helps explain why a company known for nickel-rich battery materials is now preparing for a world where LFP could be a bigger part of the mix.

And Besshi itself—continuously operated for centuries by the same company—isn’t just a trivia fact. It’s proof of something rarer: institutional patience. Multigenerational thinking isn’t a slogan at Sumitomo. It’s a demonstrated capability.

III. Modernization & Survival Through Disruption (1860s–1950s)

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 could have been the end of Sumitomo’s copper empire.

The Tokugawa shogunate was collapsing. The old feudal domains were unraveling. And the “han bills” that daimyo had issued—paper that Sumitomo had accepted in good faith through loans—suddenly started to look like Monopoly money. Inside the House of Sumitomo, the crisis got so severe that selling the Besshi Copper Mine was put on the table.

Saihei Hirose, the mine’s manager, refused. Flatly.

And then the bigger threat arrived: the new Meiji government moved to requisition strategic assets like copper mines. Besshi was exactly the kind of resource a modernizing state wanted to control.

Hirose was unusually qualified to fight that battle. He’d lived on the mountain at Besshi from a young age. He’d been into the tunnels himself. He knew what was still under the rock—and he knew the mine’s value wasn’t just the ore body, but the hard-won operational knowledge needed to pull it out safely and profitably.

So when Koichiro Kawada came to requisition the mine, Hirose made a case that mixed principle and pragmatism. Yes, Besshi had operated under the Tokugawa system—but Sumitomo had always managed it independently. And no, it wouldn’t serve Japan to confiscate a complex operation and hand it to people who didn’t know it. Kawada listened. He was impressed. And together, they secured formal approval for Sumitomo to keep operating Besshi under private control.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant. If Hirose loses that argument, the mine is nationalized—and the entire lineage that becomes Sumitomo Metal Mining takes a very different path. Instead, Sumitomo keeps the asset, keeps the expertise, and learns a lesson it will lean on for generations: the right way to navigate the state is not resistance or dependence, but credibility.

But keeping Besshi wasn’t enough. The mine had to modernize.

At Ikuno, Hirose met the advising French engineer Coignet and saw what Western mining looked like—black powder, new techniques, a different level of productivity. He came back convinced that if Sumitomo wanted to survive, it had to change how it worked underground.

In 1874, he hired a French mining engineer, Louis Larroque, to advise on overhauling Besshi. Larroque produced a detailed report: a Western mining and metallurgical blueprint for reform.

What’s striking is what Hirose did next. He didn’t just outsource competence. He treated the foreign expert as a catalyst. Sumitomo brought in outside know-how, built a plan, and began a decisive reform program in 1876—shifting from mining that relied mostly on manpower to mining that used controlled explosives, including gunpowder and dynamite.

The results were real. By 1897, annual copper output had climbed to about 3,500 tons—roughly six times what it had been three decades earlier.

Then came the problem that industrial success always seems to bring: the cost pushed onto everyone else.

As Besshi scaled, new machinery arrived. A ropeway and railroad tracks were laid. And to match the new volume, refining capacity had to expand too. The refinery that had been up in the Besshi mountains was relocated down to the coast at Niihama.

That decision solved one bottleneck—and created another. Sulfur dioxide gas discharged from the Niihama refinery drifted over surrounding farmland and damaged crops. There was no practical method at the time to recover sulfur dioxide from emissions. Technically, it was a brutal problem. Socially, it became explosive.

Teigo Iba, Sumitomo’s chief administrator, made the call: relocate the refinery again, this time to Shisaka Island in the Seto Inland Sea—offshore, away from fields and villages.

It was an enormous gamble. The construction cost came to around 1.7 million yen, about two years’ net earnings from the Besshi Copper Mine at the time. And the context mattered: the smoke hazard was threatening farmers’ livelihoods, but copper was also central to Japan’s industrial and national ambitions. Walking away from the mine wasn’t realistic.

Iba’s response wasn’t to paper over the conflict with compensation. He insisted on a genuine solution—even if it cut into profits—because the smoke hazard had to be eradicated, not managed.

That decision set a pattern. Long before “ESG” existed as a concept, Sumitomo was making a very Sumitomo choice: absorb the pain internally, keep operating legitimacy externally, and prioritize continuity over convenience.

And it didn’t stop with the move. Sumitomo Besshi also became an early pioneer in environmental measures, launching large-scale afforestation in the mid-Meiji era to restore mountains stripped by logging and damaged by smoke pollution. Over time, the natural beauty of the Besshi mountains was restored.

By the 1930s, Sumitomo had grown into a full zaibatsu spanning industries far beyond mining. And during World War II, the group expanded rapidly. The number of enterprises grew from 40 to 135 firms, and paid-in capital rose from ¥574 million to ¥1.92 billion.

Then Japan lost the war—and the expansion ended overnight.

Under Allied policy, the Sumitomo zaibatsu was dissolved. Many enterprises were left to survive on their own, suddenly separated from the structure that had coordinated them.

Shunnosuke Furuta, the director-general, turned to trade to keep people employed—echoing an earlier era when the family had operated copper shops in places like Kobe and Korea. In a strange way, the move also rhymed with the very beginning: commerce as a stabilizer, like the medicine and book shop Masatomo Sumitomo had built in the 17th century.

Out of that forced unbundling, the Sumitomo group eventually re-formed not as a zaibatsu but as a keiretsu: independent companies organized around The Sumitomo Bank and connected through cross-shareholding.

And within that new order, what emerged was Sumitomo Metal Mining as a distinct public company—no longer a single arm of a family conglomerate, but an independent entity that had to compete on its own merits. The Sumitomo name and philosophy remained. But the game had changed: now there were shareholders, public markets, and a need to prove—quarter after quarter—that a centuries-old mining business could still earn its place in a modern economy.

IV. The Post-War Reinvention: From Copper to Electronics (1950s–1970s)

The 1950s brought a different kind of existential threat. Japan was rebuilding, but the world was also closing in with a demand that would force Japanese industry into open competition.

In 1959, Western nations pushed Japan to liberalize trade and currency controls as part of GATT negotiations. For Japan’s non-ferrous metals industry—built around protected domestic supply—free trade wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was a direct hit. If imports of copper and nickel could flow in without restriction, the country’s higher-cost producers could get squeezed out fast.

SMM had to choose: keep pouring money into domestic mines that were getting harder and more expensive to run, or pivot to the global market for raw materials. The company chose the pivot—and did it quickly.

After decades of relying on ore from Besshi and other domestic operations, SMM decided to halt domestic exploration and copper mine development. It cut back operations at three copper mines and closed two others. In parallel, it accelerated procurement of smelting ore from overseas. The shift shows up starkly in the inputs to its electrolytic copper: unrefined ore and copper metal went from a small slice in the mid-1950s to the vast majority by the late 1960s.

This wasn’t just a sourcing change. It was an identity change. For nearly 300 years, “Sumitomo” and “Besshi copper” were basically the same sentence. Now the company was deliberately winding down the mines that had built the house—because the economics left no room for nostalgia. Domestic operations simply couldn’t match the cost position of large overseas mines.

Trade liberalization also pushed down domestic metal prices, making the commodity business even less attractive. So SMM made a second move: if the bottom of the value chain was turning into a knife fight, it would climb upward. Instead of selling metal as metal, it would process it into forms where performance and quality mattered—and where margins were better.

In 1960, SMM established Tokyo Electronic Metal Co., Ltd. to manufacture electronic materials. Betting on the coming electronics age, it began producing functional materials for components: high-purity germanium for radios, alloy preforms for transistors and integrated circuits, and lead frames for IC applications. Over time, those efforts became SMM’s electronic and advanced materials business—the early foundation of what would later make it relevant to batteries.

It was a well-timed bet. Japan’s electronics industry was about to become a global force, and SMM put itself in the supply chain not as a brand-name manufacturer, but as the company providing the specialized materials those manufacturers couldn’t do without. The transformation—from a mining house to an advanced materials supplier—was underway.

Then came the most symbolic milestone of all. In 1973, Besshi closed, ending an operating run that began in 1691. Over its life, Besshi produced hundreds of thousands of tons of copper and stood as one of Japan’s major sources, second only to the Ashio Copper Mine.

And when the Sazare mine followed in 1979, it marked the end of nearly 300 years of domestic mining operations at SMM. From the outside, it could have looked like a finale: the old copper empire finally shutting its gates.

But that’s not what was happening. The closures were real—but so was the strategy behind them. Even as the ancestral mines wound down, SMM was building the capabilities and relationships to source resources globally and to make higher-value materials. The company wasn’t ending its story. It was repositioning for the next chapter.

V. Rebirth Through Hishikari: The Gold Mine That Saved the Company (1980s)

Just eight years after shutting Besshi, SMM caught a second wind—this time in gold.

In 1981, a new deposit was discovered at the Hishikari Mine in Kagoshima Prefecture, on Kyushu. By 1985, the mine was producing. And it wasn’t just “a new domestic mine.” It was one of those rare finds that can change a company’s trajectory.

Hishikari’s ore was exceptionally rich, averaging around 20 grams of gold per tonne—several times the grade commonly seen at major gold mines globally. Over time, Hishikari proved itself not as a flash-in-the-pan discovery but as a long-lived, steady producer. It became the only operating gold mine in Japan, and the largest in the country producing gold on a commercial scale.

That scale shows up most clearly in the historical comparison. Japan has famous old mines like Sado Kinzan, but their output was spread over centuries. Hishikari, in a few decades, produced far more gold than most people would associate with modern Japan at all.

Strategically, Hishikari did something even more important than generate earnings: it put SMM back in the mineral resources business and kept the company’s mining muscle alive. As SMM’s overseas ambitions grew later on, the engineers trained and seasoned at Hishikari weren’t just operating one mine—they were preserving institutional expertise that could be deployed across a global portfolio.

Hishikari also became a proving ground for modern mining practices. The mine operated with an emphasis on environmental consciousness and local contribution—one example being the high-temperature underground water encountered during mining, which was provided free to nearby hot spring resorts. And it kept modernizing. In December 2022, Hishikari commissioned AutoMine® Lite on a Toro™ LH307 underground loader, becoming the first Japanese underground mine to use Sandvik’s automated loading technology—aimed at higher productivity, improved safety, tighter cost control, and more transparent operations in the mine’s small cross-section tunnels.

But even a gold mine like Hishikari couldn’t solve the bigger structural issue SMM faced in the 1980s: Japan’s non-ferrous producers were increasingly dependent on overseas ore, and prices for many metals remained depressed. If SMM wanted long-term resource security, it had to go where the ore was.

That brings us to Morenci.

In 1986, SMM acquired an interest in the Morenci copper mine in Arizona—an asset known for its quality and longevity, with copper production already spanning more than a century. For SMM, this wasn’t just an investment. It was the company stepping back into mining at global scale, and it became the starting gun for a broader overseas push.

That push accelerated in the early 1990s. SMM acquired a production interest in the Candelaria copper mine in Chile in 1992, then took an equity stake in the Northparkes copper and gold mine in Australia the following year. Over time, it built a wider set of copper and gold positions abroad—particularly in Chile, where it held stakes in operations including Candelaria, Quebrada Blanca, and Ojos del Salado.

By the end of the decade, the shape of modern SMM was becoming unmistakable. The company’s three-business model was crystallizing into a system: Mineral Resources to secure raw materials through mine investments, Smelting & Refining to process those inputs with hard-won technical capability, and Materials to turn refined metals into high-value products customers couldn’t easily substitute. Each segment reinforced the others—and together, they formed a vertically integrated engine that would soon matter enormously in a world about to rediscover the strategic value of nickel.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #1: The HPAL Breakthrough (2001–2013)

This may be the most important strategic move in SMM’s modern history—and most investors have never heard of it.

The problem looked straightforward on paper, and brutal in practice. The world has lots of nickel locked up in laterite, or nickel oxide, deposits. They’re abundant. They’re widespread. And for a long time, they were almost economically useless. Traditional smelting worked best on sulfide ores. Laterites demanded a different approach: chemistry, pressure, acid, and process control at a level that turned many projects into money pits.

That approach had a name: High Pressure Acid Leach, or HPAL. It was developed in Cuba in the 1950s, and for decades it carried a reputation as “great in theory, disastrous in execution.” Other operators tried to commercialize it and ran into the same issues again and again: corrosion, poor yields, runaway costs, and endless ramp problems.

SMM decided to try anyway.

In 2001, SMM began building a new nickel refining facility on Palawan in the Philippines: Coral Bay Nickel Corporation, or CBNC. The goal was simple to state and hard to pull off—use HPAL to extract nickel and cobalt from low-grade laterite ore and do it reliably at scale.

CBNC started up in 2005. And then SMM did the thing that had stumped much of the industry: it ramped. The first production line went into operation in April 2005 and reached full capacity that same year. By 2007, CBNC was running at its nameplate capacity—about 11,000 tons per year of nickel—an outcome that stood out sharply against HPAL plants built around the same time that struggled for years to hit design performance.

In plain terms: SMM cracked HPAL.

It’s hard to point to one magic ingredient, but the recipe is consistent with Sumitomo’s long-running pattern. Centuries of smelting and refining experience meant the company had deep process engineering instincts. Patient capital meant it could invest through the inevitable complexity. And the three-business model—resources, refining, and materials—meant SMM wasn’t just building a plant. It was building a system that could secure ore, process it, and feed it into higher-value products.

With CBNC proving the concept, SMM scaled it. By 2006, it was already planning to double capacity. The second line was completed in 2009, and production eventually exceeded expectations—reaching about 24,000 tons per year of nickel by 2014.

Then came the second major build: Taganito HPAL Nickel Corporation, or THPAL, located on Mindanao in the Philippines. THPAL commenced operations in October 2013. The project was executed with a total investment outlay of US$1.3 billion, and SMM brought in partners: Mitsui & Co. and Nickel Asia Corporation.

The flow of material at Taganito shows why this mattered strategically. THPAL produces a mixed nickel-cobalt sulfide—mixed sulfide, or MS. That MS is shipped to Japan, where SMM’s Niihama Nickel Refinery and Harima Refinery process it into products like electrolytic nickel, electrolytic cobalt, and nickel sulfate. In other words, HPAL didn’t replace SMM’s legacy strengths. It plugged into them, feeding the downstream refining and materials businesses with a stable stream of nickel and cobalt that could not be produced economically with traditional methods.

THPAL’s initial commercial production level was around 30,000 tons per year, and as global automakers pushed harder into EVs, the project’s targeted eventual capacity was revised upward to 36,000 tons per year.

The ownership structure made the split clear. CBNC was wholly owned by SMM. THPAL was majority-owned: SMM at 75%, Mitsui at 15%, and Nickel Asia at 10%.

Zoom out, and the significance is bigger than any single plant. HPAL gave SMM access to nickel resources that much of the industry couldn’t touch. It created a barrier to entry measured not just in money, but in hard-earned operational know-how. And it positioned SMM to do something that would soon matter far more than “nickel production” as a category.

Because once electric vehicles arrived and the world started demanding high-energy-density batteries, the question wasn’t just who could make cathode materials. It was who could secure the nickel behind them. And thanks to HPAL, SMM could source that nickel from deposits other companies had written off.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Panasonic-Tesla Partnership (2004–Present)

This is how a 400-year-old mining company became essential to the electric vehicle revolution.

In 2004, the head of Panasonic’s battery research center came to Sumitomo Metal Mining with a very specific ask: help us build a higher-energy cathode for lithium-ion cells. The two companies formed a venture to develop and commercialize a new chemistry: NCA, short for lithium nickel-cobalt-aluminum oxide.

Panasonic’s choice of partner wasn’t random. Lithium-ion batteries don’t just need “nickel.” They need nickel refined to a high standard, then engineered into a cathode powder with tight performance specs and consistency at scale. SMM was Japan’s largest nickel refiner, and it already had the materials-processing sophistication to do more than ship commodity metal. It could help invent, then manufacture, the cathode itself.

The timing was perfect. In 2013, Tesla and Panasonic signed a major lithium-ion battery cell agreement, expanding on an earlier deal from 2011. NCA became the cathode chemistry at the center of that relationship because it delivered what Tesla cared about most: energy density, the thing that turns into driving range.

There’s a tradeoff baked into the chemistry. Nickel-rich cathodes like NCA can store more energy, but they rely on costly inputs like nickel and cobalt. LFP, by contrast, tends to be safer and cheaper because it uses more abundant materials, but typically holds less energy. For Tesla’s early push, NCA’s upside was the point.

That demand forced SMM to scale. The company invested about US$48 million to expand production capacity of lithium nickel oxide from 300 tons per month to 850 tons per month to support Panasonic’s increased cell production for Tesla’s Model S.

The expansions didn’t stop there. Under its three-year business plan, SMM increased output of NCA materials for lithium-ion cathodes from about 1,850 tons per month to 2,550 tons per month, aiming to support the supply chain for Tesla’s next wave, including Model 3. The pattern was straightforward: Panasonic built the cells, SMM supplied the nickel-based cathode material, and as Tesla volumes grew, SMM kept enlarging the upstream pipe—ramping lithium nickel oxide to 850 tons per month in 2014, and later expanding further.

This is where SMM’s structure becomes the story. The advantage isn’t only that it can make cathode powder. It’s that it can feed that materials business with its own upstream capabilities. Nickel intermediates are processed into nickel sulfate. A stable supply of that sulfate supports consistent, high-quality battery material production. And because SMM’s smelting and refining operations sit inside the same corporate system, it can optimize material properties and deliver the traceability battery customers require.

The HPAL investments from the previous chapter slot directly into this one. SMM owns Coral Bay Nickel Corporation (CBNC), which has operated an HPAL plant in southern Palawan since 2005. The nickel-cobalt mixed sulfide produced at CBNC is exported to SMM’s plants in Japan and processed into products used for battery materials and more. Over time, SMM’s battery materials were adopted not only by Tesla, but also by Toyota for in-car batteries.

This is the payoff: decades spent building HPAL capability, operating in the Philippines, and pushing materials science forward translated into a position where SMM wasn’t merely supplying nickel. It was supplying the precise cathode materials Panasonic specified for Tesla—and doing it with control from raw material through refining to finished cathode.

And then SMM pushed the logic even further. Since 2017, it has operated a business to recover and recycle copper and nickel from end-of-life lithium-ion batteries and manufacturing scrap, turning them back into raw material for cathode production.

That effort has continued to deepen with Panasonic Energy. The two companies collaborated on a recycling initiative designed as a closed loop: end-of-life products are reprocessed into raw materials and then reused in the same type of product—automotive batteries. The initial focus is nickel, with plans to extend beyond 2026 to other key cathode materials, including lithium and cobalt. Panasonic Energy has set a target of reaching 20% recycled cathode material content in its automotive batteries by 2027.

VIII. The EV Gold Rush: Scaling for the Electric Future (2018–2024)

By the late 2010s, EV demand stopped being a science project and started looking like an industrial land grab. For SMM, that meant one thing: build capacity before you get bottlenecked.

The company, which supplies nickel-based cathode materials for Panasonic’s lithium-ion batteries used in Tesla EVs, laid out an aggressive ramp. It aimed to lift cathode materials capacity to around 7,000 tonnes per month by 2025, up from roughly 5,000 tonnes, and then to 10,000 tonnes per month by 2027.

To do that, SMM moved from incremental expansion to new-plant thinking. It began building a cathode materials plant in Niihama, western Japan, to add 24,000 metric tons per year of capacity in 2025 on top of an existing 60,000-ton base. And it didn’t hide the ambition: the long-term plan called for annual capacity to reach 120,000 tons by March 2028 and 180,000 tons by March 2031.

Nickel, of course, had to keep up too. SMM set a long-term target to raise annual nickel output capacity to 150,000 tons, from 82,000 tons.

All of that required a very un-Sumitomo-sounding thing: speed. SMM said it would triple capital expenditure over the next three years to expand nickel output and battery materials capacity. The plan called for 494 billion yen (about $4.3 billion) of capex over three years, compared with 164 billion yen in the prior three-year period.

A key piece of that spending was a 47 billion yen (about $424 million) investment aimed squarely at nickel-based cathode materials. The stated goal was the same ramp: approximately 7,000 tonnes per month by 2025, then 10,000 tonnes per month by 2027. The expansion included new facilities in Besshi, Ehime Prefecture, and increased precursor material capacity at the Harima refinery, with completion expected in 2025.

And yes—Besshi. The name is doing work here. The same region tied to the copper mine that built Sumitomo’s industrial foundation is now where SMM is placing a modern battery materials bet. Heritage, repurposed as infrastructure.

SMM also started looking outward, exploring cathode materials production in the United States. The timing wasn’t subtle: the Inflation Reduction Act had turned battery supply chains into industrial policy, and SMM signaled it would follow the rulebook as it evolved.

"Where and when to increase our production capacity next time depends on each country's regulations and laws," managing executive officer Katsuya Tanaka told an analyst meeting. "We are examining the impact from any changes to laws and regulations, including the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)."

While all of that was happening on the materials side, SMM kept doing the other half of the vertically integrated playbook: add to the resource base.

In Canada, Iamgold and SMM reached commercial production at the Côté Gold mine in northeastern Ontario’s Sudbury District. Iamgold operated the open-pit mine and held a 60.3% majority stake, with SMM owning the remaining 39.7%. The mine was expected to run for around 18 years, with average annual production of about 365,000 ounces, including higher output in the first six years averaging 495,000 ounces. Commercial production was declared after the operation consistently processed at 60% of its nameplate throughput capacity of 36,000 tonnes per day for 30 consecutive days.

Then, in December 2024, SMM struck a major new partnership with Rio Tinto. The two companies signed a term sheet to form a joint venture for the Winu copper-gold project in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia. Rio Tinto would continue developing and operating Winu as managing partner, while SMM agreed to pay $399 million for a 30% equity share—$195 million upfront, plus $204 million in deferred consideration tied to milestones and agreed adjustments.

Winu, discovered by Rio Tinto in 2017, was positioned as a low-risk, long-life copper-gold deposit, with potential to expand beyond the initial development.

The deal also fit an existing relationship: SMM and Rio Tinto had worked together before, including the joint management of the Northparkes copper mine in New South Wales since 2000. And it supported a stated long-term aim for SMM: producing 300 kilotons of copper per year, backed by stakes in assets like Quebrada Blanca in Chile, Morenci in Arizona, and Cerro Verde in Peru.

Put it all together and you can see the 2018–2024 strategy clearly. SMM wasn’t just betting on EVs by selling more material. It was trying to widen the entire pipeline—more mines, more nickel capacity, more cathode plants, and more geographic options—so it could keep supplying the battery supply chain even as regulation, customer requirements, and global competition tightened the screws.

IX. INFLECTION POINT #3: Navigating the EV Slowdown & LFP Challenge (2023–Present)

SMM’s current crossroads is the flip side of everything that made the EV buildout look so attractive just a few years ago. When you’re upstream in the battery supply chain, you don’t just ride demand. You also absorb oversupply.

And nickel is suddenly staring at exactly that problem.

The global nickel market has been heading into surplus, driven overwhelmingly by continued expansion in Indonesia. Industry forecasts pointed to the surplus widening in 2025 versus 2024 as Indonesian output, especially in low-grade nickel pig iron, kept rising. Looking further out, the expectation was for the market to stay in surplus for a third consecutive year in 2026, with Indonesia again the key driver and high-grade nickel supply also increasing.

For a company like SMM—built to secure nickel and turn it into premium battery materials—that’s a real tension. Cheaper and more abundant supply can help if you’re a buyer. But if you’re a producer and refiner, a glut is what pressures prices, margins, and investment returns.

Even on the demand side, where the long-term narrative still points up and to the right, SMM has been notably cautious. While the company projected that global nickel demand for batteries would rise in 2025 versus 2024, it also warned that the EV environment looked “quite difficult” outside China, and that demand growth could come in below expectations.

Then there’s the bigger structural shift: battery chemistry.

Growth in nickel demand slows dramatically if the fastest-growing battery type doesn’t use nickel at all. Lithium iron phosphate, or LFP, has been taking share because it’s cheaper and doesn’t require nickel or cobalt. The International Energy Agency estimated LFP accounted for roughly two-thirds of EV sales in China in 2023. That’s not a cyclical blip. That’s a different playbook.

Seen through that lens, SMM’s response looks less like a pivot and more like a survival trait—one that echoes the company’s own cultural wiring around foresight and flexibility.

China adopted LFP early and today manufactures the vast majority of the world’s LFP batteries. Against that backdrop, SMM set up an LFP project department in October to speed up development and prepare for a market where nickel-rich cathodes aren’t the only game in town.

It also made the move tangible. Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Osaka Cement agreed to transfer Sumitomo Osaka Cement’s LFP battery materials business to SMM, including the battery materials research group and SOC Vietnam Co., Ltd., with a business transfer contract concluded. In other words, SMM didn’t just announce interest in LFP. It bought its way into real capability.

That matters because SMM is already Japan’s largest supplier of nickel-rich, ternary cathode materials like lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide—NCA, the chemistry central to the Panasonic-Tesla ecosystem. Now it’s building a second leg in iron phosphate, including the LFP cathode plant in Vietnam that it acquired through that transfer. The goal is straightforward: keep expanding battery materials in line with global growth, no matter which chemistry wins share.

SMM has also been lining up technology partners. It confirmed Nano One as a key partner as it advances its LFP strategy, citing positive results from development work and trials, economic modeling, and IP review. The two companies planned to expand collaboration to pursue LFP production opportunities with target strategic customers, backed by Nano One’s proprietary One-Pot LFP process.

This is the hedge in plain terms. If LFP keeps gaining, SMM wants to be in the flow of that volume. If nickel-rich chemistries continue to dominate long-range and high-performance vehicles, SMM’s NCA franchise remains a powerful position. The company is trying to avoid being trapped in a single chemistry while still defending the one it’s best at.

But the most consequential forward-looking move may be in a third direction entirely: what comes after today’s lithium-ion.

Sumitomo Metal Mining and Toyota Motor Corporation entered into a joint development agreement aimed at mass production of cathode materials for all-solid-state batteries to be installed in battery electric vehicles. The two companies had been conducting joint research since around 2021, focusing on a key technical challenge: cathode material degradation over repeated charge and discharge cycles. Using SMM’s powder synthesis technology, they developed what they described as a highly durable cathode material suitable for all-solid-state batteries.

All-solid-state batteries replace the liquid electrolyte with a solid electrolyte. The promise is a classic “better on every axis” pitch: smaller size, higher output, and longer life—potentially translating into longer driving range, shorter charging times, and higher output in BEVs. Toyota has said it is aiming to launch BEVs with all-solid-state batteries in 2027–28. SMM, drawing on more than two decades supplying cathode materials across EV applications, said it aims to supply the newly developed cathode material and move toward mass production.

If that timeline holds and the chemistry works at scale, it would put SMM in a familiar position: not the household-name brand on the product, but the materials supplier quietly enabling the leap.

Finally, there’s a geopolitical wrinkle that could shape how this all plays out. As one industry observer put it, demand for nickel-rich conventional EV batteries could rebound over the longer term if China restricts exports of LFP technology. China’s dominance in LFP manufacturing is an advantage—but it can also become a constraint if technology access tightens. If that happens, non-Chinese automakers and supply chains may lean harder into nickel-rich alternatives in Western markets.

For SMM, that’s the pattern repeating again: commodities swinging, technology shifting, and policy reshaping markets. The company’s challenge is to keep its nickel advantage—but not be defined by it.

X. Competitive Moats and Strategic Analysis

So what actually protects SMM’s position in an industry that’s changing fast?

Process technology is the first and most obvious moat. HPAL was supposed to be the cautionary tale of the nickel world: promising on paper, brutal in practice. SMM was the first company to make High Pressure Acid Leach work in commercial production, recovering nickel and cobalt from low-grade laterite ores and turning that “unusable” material into feedstock for electrolytic nickel and, ultimately, battery materials. Plenty of competitors attempted HPAL and stumbled; SMM turned it into a repeatable operating capability. That kind of process know-how is hard to copy because it’s not just patents or equipment—it’s years of plant learning.

The second moat is vertical integration, and it’s the one that keeps showing up across SMM’s history. The group’s core advantage is a comprehensive model that links three businesses—Mineral Resources, Smelting & Refining, and Materials—into a single internal system. SMM can go from resource development, to refining, to advanced materials production under one roof. In battery materials especially, that coordination matters: quality specs are unforgiving, and supply consistency is everything. This “three-business collaboration model” isn’t just a corporate org chart—it’s how SMM de-risks inputs, controls chemistry, and scales.

Third: customer relationships. The Panasonic partnership started in 2004, and SMM’s cathode materials have been flowing into Tesla vehicles since the Model S era. In batteries, switching suppliers isn’t like swapping out a commodity part. It requires extensive qualification, long testing cycles, and a willingness to take real operational risk. That creates stickiness. Once you’re in—and you’re performing—customers don’t move casually.

Fourth: supplier lock-in, but in the reverse direction. SMM reduces procurement risk by securing nickel ore through equity stakes in mining operations. With positions in assets like Morenci, Cerro Verde, Quebrada Blanca, and now Winu, it isn’t betting everything on a single region or operator. That diversification doesn’t eliminate commodity risk, but it does lower the odds of being squeezed on raw materials at exactly the wrong moment.

One way to summarize all of this is through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework:

- Process Power: HPAL expertise and cathode manufacturing capability create cost and quality advantages that are difficult for competitors to replicate.

- Scale Economies: As cathode materials capacity scales toward 180,000 tons annually by 2031, fixed costs can be spread more efficiently across volume.

- Switching Costs: Battery makers face significant qualification costs and supply chain risk if they change cathode suppliers.

- Counter-Positioning: SMM’s willingness to invest for long periods—developing HPAL, building out Philippine operations, and scaling materials—reflects a patience that more financially constrained competitors may struggle to match.

Zoom out again and you can pressure-test the business with Porter’s Five Forces:

- Supplier Power: Moderate, and partially offset by SMM’s equity stakes in mining operations.

- Buyer Power: Concentrated. Panasonic is a major customer, which creates dependency—but also reinforces partnership and long-run integration.

- Threat of Substitutes: Rising. LFP batteries are the obvious substitute pressure on nickel-based cathodes, even as SMM works to hedge.

- Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. HPAL and long qualification cycles create barriers, but capacity can still be built by well-funded players.

- Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Chinese competitors are scaling aggressively, and Indonesian production growth continues to reshape the global nickel landscape.

But even with moats, there are real risks that sit underneath the story.

Environmental controversy is one. Civil society organizations have raised concerns about pollution at SMM’s Philippine operations, including an allegation that “it is deeply regrettable that your company along with allied businesses have failed to take effective measures to address the ongoing pollution of toxic heavy metals in the waters that flow out of the nickel mining site related to your operation for over a decade.” SMM disputes these characterizations, but the reputational and regulatory exposure is worth watching closely.

Nickel price exposure is another. Even with HPAL’s operating advantages, SMM’s profitability still moves with nickel prices—and those prices have been pressured by supply growth, particularly from Indonesia.

And finally, customer concentration. The Panasonic/Tesla relationship has been enormously valuable, but dependence on a small number of large customers ties SMM’s near-term results to specific product cycles, regional EV demand, and the evolving chemistry choices of a few key players.

XI. Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you want to follow whether SMM’s big bets are paying off, you don’t need a dozen metrics. You need three—because they sit right at the junction between strategy and reality.

1. Cathode Materials Production Volume and Capacity Utilization

This is the clearest read on near-term execution. SMM has been building toward cathode materials capacity of 84,000 metric tons in 2025, with longer-term targets of 120,000 tons by March 2028 and 180,000 tons by March 2031. What matters isn’t the ambition on the slide—it’s how much of that nameplate capacity actually runs.

When output tracks capacity, it signals both strong demand and operational discipline. If utilization stays low for an extended stretch, it’s a warning sign: either the EV market isn’t pulling as hard as expected, or the company built ahead of demand.

2. HPAL Operations Performance (CBNC and THPAL Output)

HPAL is SMM’s edge—but only if it works day after day. Coral Bay Nickel Corporation (CBNC) in Palawan, which SMM fully owns, and Taganito HPAL Nickel Corporation (THPAL) in Mindanao, which SMM owns 75% of, are the backbone of its nickel supply chain.

So the basics matter: production volumes, operating costs, and whether the plants run smoothly or suffer disruptions. Any operational hiccup flows downstream into SMM’s ability to supply cathode materials competitively. And because these assets sit in a region where permitting, scrutiny, and local impact are always part of the equation, environmental and regulatory developments there are worth tracking alongside throughput.

3. Nickel Battery Demand Growth Rate

The final KPI is the demand backdrop SMM can’t control, but has to forecast correctly. The company projected global demand for nickel used in batteries would rise to around 520,000 tons in 2025 from about 470,000 tons—roughly 10% growth.

SMM updates this in its semi-annual market outlook presentations, and it’s a useful gut check: is the battery market expanding the way SMM expects, or is it slowing, shifting chemistry, or simply growing somewhere else? When projections and reality diverge, it’s often the earliest signal that the EV transition is playing out differently than the capacity plans assume.

XII. Myth vs. Reality

Myth: SMM is primarily a mining company.

Reality: Mining is only one leg of the stool. SMM is built around a three-business model—Mineral Resources, Smelting & Refining, and Materials—designed to reinforce each other from ore to finished battery cathodes. In FY 2024, it operated at the scale of a major industrial company, with roughly US$11 billion in sales and more than US$21 billion in assets. And strategically, the center of gravity has been shifting toward materials: SMM is Japan’s largest supplier of lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide battery materials, and its cathode business increasingly defines where the company places its biggest bets.

Myth: SMM's nickel business faces inevitable decline due to LFP adoption.

Reality: LFP is real pressure—but it’s not a death sentence. SMM is trying to keep its nickel-rich NCA franchise strong while building an LFP option for a market that’s clearly diversifying. It has confirmed Nano One as a key technology partner as it advances its LFP cathode strategy, and it’s also pursuing a longer-dated upside: solid-state battery development with Toyota, which could bring nickel-rich chemistries back into an advantage position if the technology scales.

Myth: SMM is just a commodity supplier to battery makers.

Reality: SMM isn’t only selling metal into someone else’s product. The Tesla NCA technology is owned by Panasonic and Sumitomo Metal Mining—because SMM co-developed the cathode chemistry. That makes it a technology partner with manufacturing capability, not a price-taker shipping interchangeable commodity inputs. In batteries, that difference matters: it creates deeper integration, longer qualification cycles, and relationships that tend to stick.

Myth: The 400-year history is just marketing fluff.

Reality: The history isn’t the point; the habits are. Sumitomo’s founder’s precepts emphasized “integrity and sound management,” “foresight and flexibility,” and warned that “under no circumstances” should the house “pursue easy gains or act imprudently.” You can see that mindset in the modern strategy: SMM was willing to invest years—and absorb the pain—required to make HPAL work when many shorter-term-focused competitors walked away. In this business, that kind of institutional patience isn’t a slogan. It’s an operating advantage.

XIII. Looking Forward

SMM is at one of those moments where its entire history feels like prologue. A company that began with a Buddhist monk’s reinvention in 1590, survived the Meiji-era upheaval, outlived the zaibatsu dissolution, and then found itself supplying the EV boom now has to navigate the next turn: a battery market that’s evolving fast, and a minerals market that’s swinging from scarcity fears to surplus realities.

On paper, the company is trying to answer that uncertainty with a clear plan and a big swing. Its 3-Year Business Plan 2027 (FY2025–FY2027) sets out an ambitious target: profit before tax of ¥140 billion by FY2027. To get there, SMM expects to put serious capital to work, with cumulative capital expenditures, investments, and financing projected at ¥437 billion over the period.

The most “could-change-everything” piece is its partnership with Toyota on all-solid-state batteries. The focus isn’t just lab breakthroughs; it’s the unglamorous work that determines whether a technology actually ships—improving performance, quality, and safety of cathode materials, while also driving costs down to something mass production can tolerate. The ambition is bold: achieving the world’s first practical use of all-solid-state batteries in BEVs, which Toyota has targeted for 2027–28.

At the same time, SMM is widening its bet on the other essential metal of electrification: copper. The Winu copper-gold project with Rio Tinto gives SMM a stake in a deposit positioned as long-life and low-risk. And copper’s role is hard to overstate. Every part of electrification leans on it—renewable power systems, EV drivetrains, charging infrastructure, and the grid upgrades that make all of that usable at scale. If the energy transition is real, demand for reliable copper supply is, too.

What ties these moves together isn’t just strategy slides. It’s the Sumitomo Business Spirit—the long-term mindset that’s been stress-tested for more than four centuries. That’s the thread running from early smelting innovations, to costly environmental fixes, to HPAL persistence, to today’s hedging across battery chemistries and critical minerals.

For investors, SMM is a way to get exposure to the EV transition through a company with real process advantages, a vertically integrated supply chain, and the patience to make decade-long bets. The near-term headwinds are real: nickel oversupply pressure and the rise of LFP. But SMM is building optionality—HPAL leadership to keep its nickel edge, an LFP foothold so it’s not trapped in one chemistry, a solid-state pathway with Toyota, and a growing copper portfolio for the broader electrification cycle.

Whether it’s helping power Tesla Model 3s today or supplying cathode materials for Toyota’s solid-state EVs later this decade, the story keeps rhyming: a centuries-old company, still following a set of precepts written by a monk, still trying to stay ahead of the next shift in what the world needs.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music