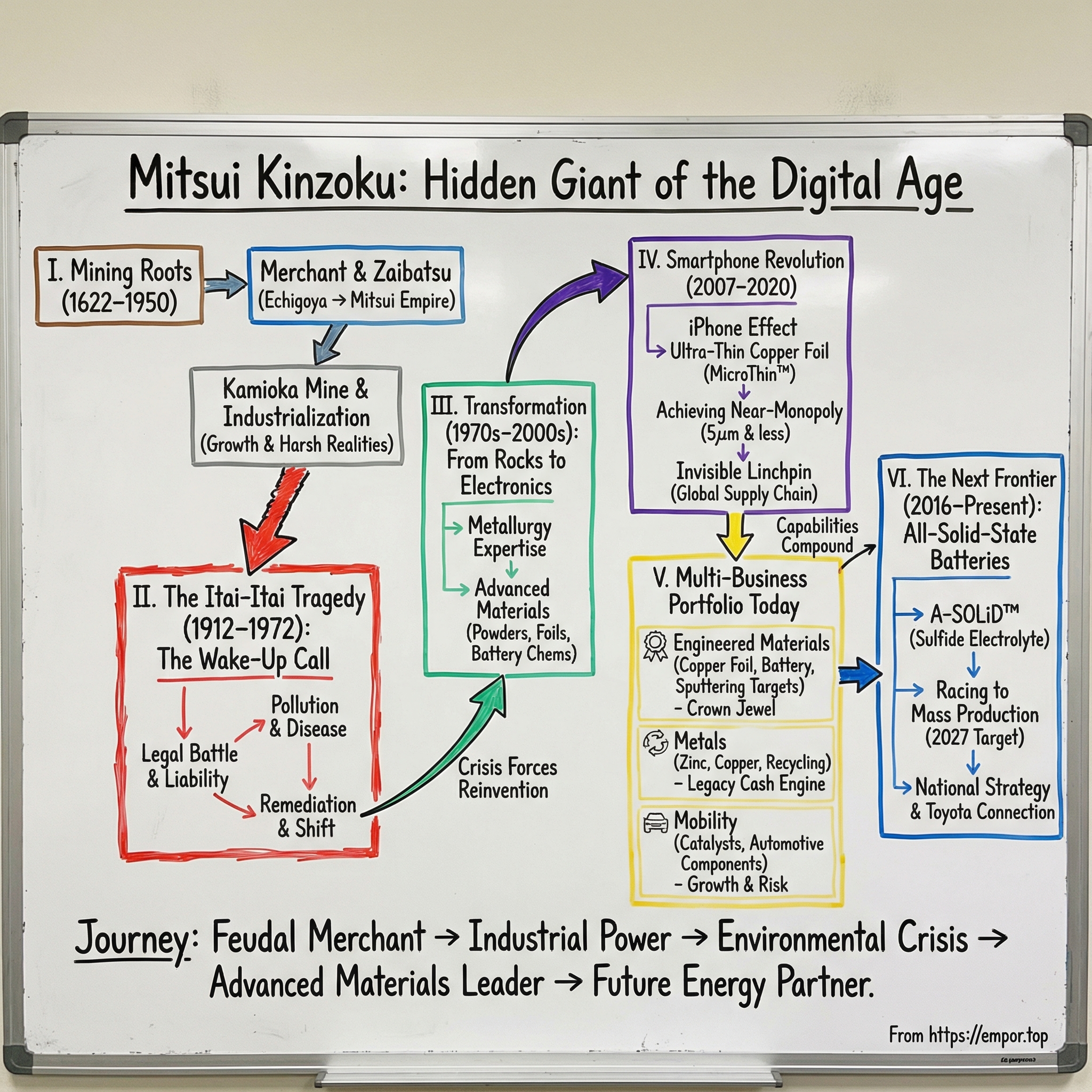

Mitsui Kinzoku: The Hidden Materials Giant Powering the Digital Age

I. Introduction: The Invisible Empire

In the palm of your hand—inside your smartphone, tablet, or laptop—there’s a layer of copper so thin it almost feels unreal: about five micrometers thick, roughly one-fifteenth the width of a human hair. And if you’ve bought a flagship phone in the last decade, there’s a very good chance the ultra-thin copper that helps connect its brain to the rest of the device came from one place: a seventy-five-year-old Japanese company most technology fans have never heard of.

That company is Mitsui Mining & Smelting Co., Ltd., known in Japan as Mitsui Kinzoku. It’s the world’s largest producer of electrodeposited copper foil at five micrometers or less—holding more than 95% of the global market for that ultra-thin category. This isn’t the kind of dominance you see in consumer brands. It’s the quiet, structural kind: the sort that shows up in performance specs, supply-chain risk meetings, and the bill of materials for the most advanced electronics on Earth.

Which makes the real hook of this story almost irresistible: how did a company built on zinc mining—whose roots reach back into Japan’s feudal economy, and whose modern history was later haunted by one of the country’s worst environmental disasters—end up as an essential supplier to smartphones, cutting-edge semiconductor substrates, and increasingly, the chips powering artificial intelligence?

As of March 2025, Mitsui Mining and Smelting had trailing twelve-month revenue of about $4.67 billion. But the point isn’t the size of the number. The point is where the company sits: at the foundation layer of the modern digital world, where importance is measured in micrometers, reliability, and the ability to manufacture at a quality level few others can match.

Today, Mitsui Kinzoku operates across three major segments. Engineered Materials is the star, home to the copper foil business as well as battery materials, sputtering targets, and specialty powders. Metals is the legacy engine—zinc, copper, and precious metals—alongside a growing recycling operation. And Mobility includes exhaust gas catalysts and automotive door components produced through its subsidiary, Mitsui Kinzoku ACT Corporation.

To understand how Mitsui Kinzoku made this leap—from a mining-and-smelting company to a hidden linchpin of the smartphone era, and possibly the EV era—we have to go back. Back through centuries of Japanese commerce and industrialization: from Edo-period merchant houses, to the hard realities of extraction and pollution, to the spotless clean rooms where modern electronics are born. In many ways, Mitsui Kinzoku’s evolution mirrors Japan’s own—reinvention, resilience, and an almost obsessive mastery of the unglamorous materials the modern world can’t live without.

II. The Mitsui Empire & Mining Roots (1622–1950)

The Merchant's Son Who Built an Empire

In 1622, in the castle town of Matsusaka in what’s now Mie Prefecture, Mitsui Takatoshi was born the fourth son of a shopkeeper. The family business was called Echigoya. It wasn’t glamorous: miso sales, pawn lending, the practical commerce of everyday life. Nothing about it screamed “future industrial dynasty”—let alone “supplier to the electronics age.”

Takatoshi left for Edo at fourteen, later joined by his older brother, then got sent back home to Matsusaka. And then he waited. For years. In fact, he waited until his older brother died—twenty-four years later—before he could finally take the reins.

That kind of patience wasn’t incidental. It became a recurring Mitsui trait: long horizons, careful positioning, and a willingness to build steadily until the moment was right.

When Takatoshi did take control, he didn’t just run the shop. He rewired how Japanese retail worked. Instead of custom orders and credit, he stocked goods in advance and sold them directly for cash—an approach that sounds obvious now, but in feudal Japan was a genuine break from tradition. It made buying faster, simpler, and more predictable. And it made Mitsui very wealthy.

From Kimono Shops to Zaibatsu

The leap from merchant wealth to industrial power came after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Japan threw itself into modernization. Mitsui was one of the enterprises that rode that wave—and helped steer it.

Mining entered the picture in a very Mitsui way: opportunistically. The group acquired a mine as collateral on a loan, and it helped that government mines could be bought cheaply in that era. What started as a financial happenstance became a strategic cornerstone. Mitsui’s leaders—often professional managers rather than family—were known for reading political winds, cultivating high-level relationships, and investing boldly when the time came.

By 1889, Mitsui had acquired major coal assets, and Mitsui Mining became one of the oldest and most important affiliates in what was forming into the Mitsui zaibatsu. Coal and nonferrous metals soon became one of the empire’s three pillars, alongside banking and trade. This wasn’t just diversification. It was a system: finance and trading to move money and goods, and mining to generate the steady, hard cash that kept the whole machine fed.

Mitsui’s mines turned into engines of profit, including the Miike operations—and then Kamioka, a mountain deposit rich in zinc and lead, with traces of cadmium, silver, and copper. Kamioka sat deep in the mountains of what’s now Gifu Prefecture. It would become central to this story: one of Mitsui’s greatest commercial assets, and later the source of its darkest chapter.

The Dark Side of Rapid Industrialization

That wealth came with a brutal underside. In that era, Mitsui Mining could—and did—exploit labor from poorly paid women and children, prison convicts, and, at times, prisoners of war. The mines weren’t merely profitable; they provided the dependable income that allowed the broader Mitsui empire to keep branching into riskier, higher-upside industries.

Conditions for miners were grim. Contemporary accounts describe something close to semi-slavery: twelve- to fourteen-hour days, few holidays, and wages that barely covered survival. Men, women, and children worked together, and children were especially valued because they could fit into the narrowest seams underground.

This wasn’t unique to Mitsui. It was the ugly fuel of Japan’s rapid industrialization. And as Japan went to war—first with China in 1894–1895, then with Russia a decade later—the demand for materials surged. Lead, sulfur, iron: the ingredients of munitions and modern warfare. Kamioka ramped production hard to meet that demand, becoming at one point the largest zinc mine in East Asia and the most efficient zinc mine in the world. Its production history stretched back roughly 1,100 years—an ancient resource site now feeding a modern empire.

Mitsui wasn’t just pulling ore out of the ground. It was underwriting Japan’s industrial rise. Mining cash flows helped Mitsui expand into banking, trading, shipbuilding, and manufacturing—an interlocking set of businesses that came to dominate the economy.

Post-War Dissolution and Rebirth

Then World War II ended—and with it, the world that had allowed the zaibatsu to thrive.

Under General Douglas MacArthur and the Allied occupation, Japan’s great conglomerates became targets. The occupiers wanted to break monopolistic power, reduce Japan’s ability to wage war again, and foster competition. Mitsui Mining drew particular scrutiny: it had supplied key wartime raw materials and stood among Japan’s leading producers of coal and nonferrous metals.

In 1950, the company that would become Mitsui Mining & Smelting was created as Kamioka Mining & Smelting Co., Ltd., after Mitsui Mining Company was forced to dissolve. The split severed it from the coal heritage and left it anchored in the Kamioka zinc operations and other nonferrous assets.

But geopolitics pivoted quickly. As the Cold War intensified, American priorities shifted from dismantling Japanese industrial capacity to strengthening it. The U.S. wanted Japan stable and productive—a dependable sentinel in the Far East. The harshest anti-zaibatsu policies faded, and the old cooperative style of Japanese corporate planning began to reassert itself in a new form: the keiretsu.

In 1952, just two years after its creation, Kamioka Mining & Smelting was renamed Mitsui Mining & Smelting Co., Ltd. It had inherited the largest and highest-quality zinc mine in Japan—possibly the best in the Eastern Hemisphere. The company was back under the Mitsui name, connected to the Mitsui keiretsu network of cross-shareholdings and relationships, and focused squarely on nonferrous metals.

It was set up for Japan’s economic miracle. But downriver from Kamioka, another legacy was already taking shape—one that would force Mitsui Kinzoku to reinvent itself in ways nobody could yet imagine.

III. The Itai-Itai Tragedy: Japan's Wake-Up Call (1912–1972)

The Disease That Made People Cry

In the early 1900s, in the farming villages along the Jinzū River in Toyama Prefecture, something horrifying began to surface—first as aches, then as a kind of pain that took over lives. Women who’d spent decades working rice paddies irrigated by the river started to suffer relentless bone and joint pain. Walking hurt. Sitting hurt. Bending hurt. Bones became so brittle they could fracture from ordinary movement. In the worst cases, people became bedridden as their spines compressed and their bodies endured constant agony.

Locals gave the illness its name because they could hear it. “Itai” means “it hurts.” Victims would cry out “itai, itai” as the disease progressed. And so it became known as itai-itai disease—a mass cadmium poisoning that began around 1912.

For decades, nobody could say with certainty what was causing it. In the 1940s and 1950s, medical testing intensified, and early theories pointed to lead poisoning—after all, there was lead mining upstream. But in 1955, Dr. Noboru Hagino and his colleagues began to suspect something else: cadmium.

Hagino’s work had the feel of a detective story, but the clues weren’t subtle. The disease clustered in areas irrigated by the Jinzū River, downstream of where the river passed the Kamioka mines. The geography drew a line from industrial output to human suffering.

The Source of the Poison

In 1961, Toyama Prefecture launched its own investigation. It concluded that Mitsui Mining & Smelting’s Kamioka Mining Station was the source of cadmium pollution—and that the most severely affected communities sat roughly 30 kilometers downstream.

The underlying reason was chemistry and geology. The main zinc ore at Kamioka was sphalerite, and sphalerite is often found alongside greenockite—one of the only major cadmium-bearing minerals. That meant cadmium wasn’t some rare contaminant. It was a routine by-product of zinc mining.

And for decades, it was treated like garbage. Until 1948, cadmium had little industrial value, so it was discarded as waste—released into the river system.

Mitsui Mining began discharging cadmium into the Jinzū River in 1910. From there, the pathway was brutally simple: contaminated water irrigated rice fields; people drank the water, ate food grown with it, and absorbed cadmium over time. The company’s success extracting zinc had, in effect, set a slow-moving trap for the communities downstream.

The pollution worsened as Japan’s appetite for raw materials grew. Wartime demand—along with new mining technologies imported from Europe—pushed production higher. From 1910 through 1945, cadmium was released in significant quantities as mining and processing expanded.

In the 1920s, it got worse again. New froth flotation processes boosted zinc output, but they also increased fine tailings—powdered mineral particles that escaped in wastewater and drifted downriver.

The Jinzū River wasn’t an abstract channel on a map. It was daily life: irrigation for rice fields, drinking water, washing, fishing. Downstream residents complained, and Mitsui Mining & Smelting responded by building a basin to store mining wastewater before releasing it into the river. It didn’t work, and by then many people were already sick.

The Landmark Legal Battle

In 1968, Japanese health authorities formally recognized itai-itai disease. It became the first officially acknowledged environmental disease in Japan—turning a local tragedy into a national reckoning with the costs of industrial growth.

That same year, affected residents filed a lawsuit against Mitsui Mining & Smelting. They won at trial in 1971, when the Toyama District Court ruled in the victims’ favor and held the company responsible. Mitsui Mining & Smelting appealed, disputing causality, but the decision was upheld at the Nagoya High Court in 1972.

The case itself was historic: citizens defeating a major corporation in a pollution-related illness suit—an outcome that would shape how Japan thought about corporate accountability. One account describes the lawsuit as being filed by 28 citizens on behalf of around 500 alleged victims, with damages in the aggregate amounting to about one year of the company’s net income.

After the court decisions, Mitsui Mining formally admitted that the disease was caused by its discharge of cadmium into the Jinzū River. The company was obliged to compensate victims and cover recovery costs for contaminated land, and the parties signed a pollution control agreement.

The Long Road to Remediation

Winning in court didn’t end the story. But what followed made the itai-itai case unusual. Instead of dissolving into endless delay, the victims and the company entered into an ongoing system of monitoring and remediation—messy, expensive, and measured in decades rather than news cycles.

Remediation efforts began in 1972 and were mostly complete as of 2012. Cleanup costs were borne not only by Mitsui Mining but also by Japan’s national government and the Gifu and Toyama prefectural governments.

The government’s broader response was sweeping. The Prevention of Soil Contamination in Agricultural Land Law of 1970 ordered planting to be stopped in areas where cadmium levels reached one part per million or more so restoration could begin. Surveys in Toyama started in 1971, and by 1977 about 1,500 hectares along the Jinzū River were designated for soil restoration. Farmers were compensated for lost crops and for lost production in prior years by Mitsui Mining & Smelting, Toyama Prefecture, and the national government.

By 1996, mean cadmium concentrations in agricultural land had returned to background levels—about 0.1 ppb—signaling that outflow had fallen to trivial levels. Annual inspections over more than forty years, conducted under the pollution control agreement, showed cadmium concentrations in the river declining back toward natural levels.

None of this was cheap. Mitsui Mining & Smelting paid for major soil pollution cleanup and for long-term prevention measures—drainage treatment, smoke treatment, and work on closed and abandoned mines—adding up to billions of yen over decades.

And still, the saga didn’t fully close for a long time. Mitsui Mining & Smelting agreed to compensation, including a lump sum for victims, but the judgment’s broader resolution stretched on. The cadmium poisoning case wasn’t fully resolved until 2013—more than forty years after the first court victory.

For anyone studying Mitsui Kinzoku, it’s the sobering part of the origin story: environmental liabilities can outlast leadership teams, strategies, even eras. But it’s also the turning point. By the 1970s, Mitsui Kinzoku could no longer pretend it was simply a mining company extracting value from the ground. The pollution crisis forced a more existential question—what, exactly, was the company’s real capability, if not mining?

The answer would pull Mitsui Kinzoku away from rocks and toward something far more precise: engineered materials for the electronics age.

IV. The Transformation: From Rocks to Electronics (1970s–2000s)

The Diversification Imperative

After the itai-itai verdict, Mitsui Kinzoku’s leadership had to face a hard reality: a company defined by mining was becoming harder to defend—and harder to grow. Domestic ore deposits were finite. Public tolerance for pollution was collapsing. And the remediation obligations weren’t a one-time charge; they were the kind of commitment that would show up on the balance sheet for decades.

So Mitsui had to answer the question the courts and communities had effectively forced on it: if the future can’t be “dig more,” what is this company actually good at?

The answer was hiding in plain sight. Mitsui’s real advantage wasn’t the mountain. It was metallurgy—an institutional understanding of how metals behave, how impurities move, how to control chemistry and structure at tiny scales. The know-how required to refine zinc out of messy ore turned out to be closely related to the know-how Japan’s electronics boom desperately needed: ultra-high-purity metals, specialized powders, and precision materials that could survive the unforgiving demands of semiconductors.

In 1990, Mitsui signaled this shift outwardly by adopting a new corporate logo and becoming known domestically as Mitsui Kinzoku—leaning into “kinzoku,” metals, more than mining. But the real change was internal. Mitsui increasingly positioned itself not as an extractive company, but as a specialty materials company—one that just happened to have a long mining history.

From there, the portfolio moved steadily up the value chain: tantalum and niobium for electronics; copper foil for circuit boards; and sputtering targets, used to deposit microscopically thin metal coatings during semiconductor fabrication. These weren’t commodity products. They were engineered building blocks for industries that cared less about tonnage and more about performance, consistency, and purity.

Building the Copper Foil Business

Copper had long been part of Mitsui Mining & Smelting’s postwar mix. As Japan’s economy surged, “peacetime” demand for metals expanded fast—construction, appliances, and the early rise of the auto industry all pulled more lead and copper through the system. Mitsui got good at not just producing metal, but adapting it into forms customers could actually use.

But the real inflection point was electronics. Printed circuit boards were getting denser. Devices were shrinking. And as miniaturization accelerated, demand surged for copper foil that was not only conductive, but uniform, clean, and manufacturable at scale.

To serve that market globally, Mitsui built a major presence in the United States. Oak-Mitsui Technologies LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Mitsui Kinzoku based in Frankfort, Kentucky, was established in 2003 to develop material solutions for the printed circuit industry.

Oak-Mitsui Inc. became a centerpiece of the effort—developing and producing high-performance copper foils for electronics and, increasingly, for lithium-ion battery applications. With U.S. operations across Hoosick Falls, New York; Camden, South Carolina; and Riverside, California, the business gave Mitsui a direct bridge into global electronics supply chains, not just Japan’s.

The 70-Year Battery Materials Journey

One of the most surprising parts of Mitsui Kinzoku’s reinvention is that it wasn’t purely a post-crisis pivot. The company had been building battery-material capabilities for decades—quietly, steadily, and early.

It began manufacturing electrolytic manganese dioxide for manganese batteries in 1949. It followed with cadmium oxide powder for Ni-Cd batteries in 1958, zinc powder for alkaline manganese batteries in 1972, MH alloy powders for Ni-MH batteries in 1990, and LMO powders for lithium-ion batteries in 2001.

Seen as a timeline, it’s a straight line running through multiple battery eras. While the company’s public identity was dominated by mining—and then by the long shadow of remediation—it was accumulating practical chemistry and manufacturing experience that would become strategically vital once energy storage moved to the center of consumer electronics and transportation.

Mitsui Kinzoku’s battery-materials role also connected it to some of the most important products of modern mobility. The company supplied materials that supported the development of nickel metal hydride batteries used in the Toyota Prius—an early signal that Mitsui would have a place in electrification supply chains long before “EV” became a mainstream obsession.

Mitsui Mining & Smelting also supplied lithium manganese oxide and nickel-lithium, both used in cathodes—the heart of any battery. In other words, while Mitsui was redefining itself as an advanced materials company, it was also steadily positioning itself inside the future demand curve.

The Strategic Logic of Transformation

From the outside, Mitsui’s shift from mining to advanced materials can look like a leap. Up close, it reads more like a disciplined climb.

First came refining and purification—still metals, but with higher margins and tighter process control. Then came specialty powders and compounds engineered for specific industrial needs. And finally, those materials turned into precision components for electronics and batteries, where performance and reliability mattered more than sheer volume.

It wasn’t fast, and it wasn’t trendy. It required long-term investment in R&D while relying on cash flow from legacy businesses to fund the climb. The Mitsui keiretsu network helped too, offering stability, relationships, and a corporate environment built for long horizons. Patience wasn’t just cultural—it was strategic.

By the turn of the millennium, Mitsui Kinzoku had largely completed its metamorphosis. It was no longer primarily a mining company that also made advanced materials. It was an advanced materials company that still carried mining in its DNA.

And that set the stage for the company’s defining act in the next era: building near-total dominance in ultra-thin copper foil, right as the smartphone and semiconductor revolutions hit full speed.

V. The Smartphone Revolution: Ultra-Thin Copper Foil Dominance (2007–2020)

The iPhone Effect

On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs walked onto a stage in San Francisco and introduced the iPhone. Within a year and a half, the smartphone didn’t just win the consumer market. It rewrote the rules of electronics design.

But the real shockwave ran through an invisible layer of the supply chain. As phones became thinner, faster, and more packed with compute, the boards inside them had to carry more signals through less space. That meant finer circuit lines. And finer circuit lines meant thinner, more precise copper foil than the industry had ever needed at scale.

Here’s the catch: at five micrometers or less—around one-fifteenth the width of a human hair—copper foil stops behaving like a sturdy industrial material and starts behaving like something you could crumple with a breath. It wrinkles. It tears. It’s maddeningly hard to handle in manufacturing.

Mitsui Kinzoku’s workaround was deceptively simple: don’t try to handle the ultra-thin foil on its own. Support it.

Its MicroThin™ product is an ultra-thin electrodeposited copper foil bonded to a thicker carrier foil that provides mechanical strength during processing. The carrier stays on through handling and lamination, and then, after the foil is laminated to a resin film or similar substrate, the carrier can be peeled away—leaving the ultra-thin copper in place without ever having to treat it like a standalone sheet.

MicroThin™ was adopted in semiconductor package substrates for smartphones and in HDI substrates for high-end smartphones. It enabled circuit patterns that conventional approaches couldn’t reliably achieve—exactly when the smartphone era made those patterns non-negotiable.

Achieving Near-Monopoly

Once the market made ultra-thin foil with a carrier essential, the next question became: who can actually manufacture it, consistently, at scale?

For most competitors, the answer was: not many. Mitsui Kinzoku pulled into a position so strong it barely resembles normal industrial competition. By the late 2010s, it held more than 90% of the global market for this ultra-thin copper foil-with-carrier category, and in late 2017 the company announced plans to boost monthly production capacity by nearly 50% by November 2018.

That dominance wasn’t just about having the idea first. It was about being able to execute the process with extreme consistency. One of the hardest requirements is controlling the release strength—the adhesion between the ultra-thin foil and the carrier—so it stays bonded through manufacturing but peels cleanly at the right moment. And it has to be uniform across an enormous roll: more than a meter wide and stretching for thousands of meters.

This is the kind of manufacturing advantage that doesn’t show up in a consumer product launch. It shows up when a customer runs a high-volume production line and everything simply works—over and over again.

Mitsui Kinzoku produced foils as thin as 1.5 μm up through 5 μm, and kept pushing toward even thinner products, tracking the semiconductor industry’s relentless appetite for miniaturization.

The Broader PCB Copper Foil Market

Mitsui Kinzoku’s near-monopoly is specific to the ultra-thin “with carrier” niche. Zoom out to the broader copper foil market for printed circuit boards, and the landscape looks more like an oligopoly. Fukuda, Mitsui Kinzoku, Furukawa Electric, and JX Nippon Mining & Metal together account for an estimated 40% of global production.

The market itself has continued to expand with rising demand for electronics across everything from rigid and flexible PCBs to higher-speed applications. Innovation has largely flowed in a few directions: thinner foils (often under 12µm) for high-density interconnect boards, better performance for faster communications like 5G and data centers, and manufacturing processes with a lighter environmental footprint.

Global Expansion

As electronics manufacturing surged across Asia, Mitsui Kinzoku moved to stay close to its customers—especially in China. To develop new customers and capture needs early, the company established a copper foil marketing department within Mitsui Kinzoku Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. It became Mitsui’s third marketing base in China, following Mitsui Copper Foil (Hong Kong) Co., Ltd. and Mitsui Copper Foil (Suzhou) Co., Ltd.

The demand story didn’t stop with smartphones. In Q4 2022, Mitsui Kinzoku announced an expansion of copper foil production capacity in Japan, aimed at keeping up not only with mobile devices but also with rising demand tied to advanced chips.

And the company kept iterating on the core technology. In March 2024, it unveiled a new approach to improved peelability in its ultra-thin copper foils—an important signal in a category where “good enough” isn’t good enough, and leadership depends on staying ahead of customers’ next manufacturing bottleneck.

The Invisible Giant

This is the counterintuitive truth Mitsui Kinzoku embodies: in modern technology, the most strategically powerful companies often aren’t the ones with household names.

Apple, Samsung, and Nvidia capture attention. But they—and their manufacturing ecosystems—depend on specialty suppliers whose products rarely get mentioned and cannot easily be replaced. Copper foil is used across smartphones and computers, home appliances, automobiles, and even construction. It’s one of those foundational materials that quietly holds modern life together.

And that’s what makes Mitsui Kinzoku so fascinating. A company with overwhelming share in a critical, hard-to-replicate input can be more defensible than a brand fighting for share in the finished-product market. It’s dominance measured not in billboards, but in micrometers—and in the unforgiving reality that if you can’t get this material right, the device doesn’t ship.

VI. The Multi-Business Portfolio Today

Engineered Materials: The Crown Jewel Segment

If Metals is the company’s origin story, Engineered Materials is the modern Mitsui Kinzoku—where decades of metallurgical know-how get turned into high-performance ingredients for electronics. This is the highest value-added part of the portfolio, spanning ultra-thin copper foil, battery materials, specialty powders, and PVD materials used in semiconductor manufacturing.

In sales terms, functional materials make up the largest slice of the business, at roughly four in ten yen of revenue. That bucket includes electrolytic copper foil, battery materials, and ceramic products. It’s also where the company’s best economics tend to live, because customers here aren’t buying “metal.” They’re buying performance, consistency, and manufacturability at microscopic scales.

On batteries, Mitsui Kinzoku supplies cathode materials for both NiMH and lithium-ion batteries from its Takehara facility in Japan. It’s also working on silicon-based anodes to boost lithium-ion performance. And this isn’t just lab work in beakers: the company maintains a full lithium-ion cell pilot line, capable of producing and testing 18650 cells, so it can validate materials in real battery formats, under real conditions.

Beyond batteries and copper foil, the segment includes sputtering targets—the feedstock used to deposit ultra-thin metal films during semiconductor fabrication—and ultra-fine powders for electronic materials. Different products, same underlying theme: helping customers keep shrinking devices while pushing speed, power efficiency, and reliability in the opposite direction.

Metals: The Legacy Cash Engine

Even after the pivot to advanced materials, Mitsui Kinzoku never stopped being a serious metals company. Non-ferrous metals still contribute roughly three in ten yen of sales, spanning zinc, gold, silver, zinc alloys, and recycling services. This is the company’s historical foundation, and it still throws off the steady cash flows that help fund the rest of the portfolio.

Kamioka, the mine tied so tightly to Mitsui’s rise—and to the itai-itai tragedy—ended active mining operations in 2001–2002. In one of the stranger twists you’ll ever find in corporate history, the site later found a second life as an underground neutrino observatory used by the University of Tokyo: a former industrial workhorse turned world-class physics research facility.

But the metals business didn’t disappear with Kamioka. Mitsui Kinzoku sources ore globally, while continuing to run smelting and refining operations in Japan. Increasingly, it also uses recycling of nonferrous and precious metals as feedstock—an approach that fits modern environmental priorities and reduces reliance on primary mining.

Mobility: Automotive Components and Catalysts

Mobility is the third pillar, accounting for roughly one-eighth of sales. It’s essentially two businesses under one roof: exhaust gas catalysts, and automotive door components.

Catalysts are materials that accelerate chemical reactions without being consumed themselves. In the automotive world, that means helping detoxify exhaust—exactly the kind of “invisible” technology that becomes mandatory as regulations tighten globally.

In the U.S., Mitsui Kinzoku operates through MKCA, Mitsui Kinzoku Catalysts America, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary headquartered in Frankfort, Kentucky. Established in 2013, it serves as one of the core production sites for the company’s catalysts division.

The other half of Mobility runs through Mitsui Kinzoku ACT Corporation, an automotive equipment manufacturer focused on door-related products. ACT operates end-to-end—planning, development, and manufacturing—across everything from door components to power-assisted door systems.

By the company’s own account, one in five cars on the road worldwide uses products made by Mitsui Kinzoku ACT. It’s a global business, with operations across North America, Europe, and Asia, built around a reputation for quality and technical capability.

At one point, this business was separated from Mitsui Mining & Smelting and relaunched under the Mitsui Kinzoku ACT name—giving it more strategic autonomy while still staying connected to the parent company.

Geographic Distribution

Geographically, Mitsui Kinzoku’s sales are still concentrated where electronics are designed, built, and assembled. Japan accounts for just over half. The rest is heavily Asia-weighted: China is roughly 14%, India just under 10%, and other Asian markets make up another meaningful chunk. North America is smaller, with the remainder spread across other regions.

That footprint is both logical and revealing. The company’s highest-margin products feed the electronics supply chain, and the electronics supply chain lives in Asia. But it also means exposure—especially to China—is simultaneously a growth engine and a risk factor as geopolitics pushes customers to rethink where the world’s most critical technologies get made.

VII. The Next Frontier: All-Solid-State Batteries (2016–Present)

Betting on Battery's Future

In November 2016, Mitsui Kinzoku made a big move that barely registered outside industry circles: it announced it had developed an Argyrodite-type sulfide solid electrolyte for all-solid-state batteries. This wasn’t a minor tweak to an existing chemistry. It was Mitsui planting a flag in what many researchers believe could be the next major step-change in energy storage.

The company’s material is branded A-SOLiD™, an Argyrodite-type sulfide solid electrolyte designed for high lithium-ion conductivity and strong electrochemical stability. Mitsui framed the effort in the language you’d expect from a modern materials champion: carbon neutrality needs better rechargeable batteries, and better batteries start with better materials.

All-solid-state batteries matter because they swap the liquid electrolyte used in conventional lithium-ion cells for a solid material. In theory, that trade unlocks the features the market has been chasing for years: higher energy density, faster charging, improved safety, and longer life. For EVs, proponents argue it could eventually mean dramatically longer range—sometimes described as exceeding 1,000 kilometers on a single charge—alongside faster and safer charging.

On the technical front, Mitsui has described its sulfide-based solid electrolyte as achieving high lithium-ion conductivity on the order of 10⁻³ S/cm. And it hasn’t treated the electrolyte as a standalone science project. The company has been working to verify positive and negative electrode active materials whose electrochemical properties and powder characteristics fit this electrolyte, with the goal of building high-energy-density all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries that also deliver environmental resistance, safety, and strong input/output characteristics.

The A-SOLiD™ Advantage

Mitsui positions A-SOLiD™ as a way to overcome key drawbacks of conventional lithium-ion batteries—particularly around safety and performance tradeoffs—by using sulfide-based solid electrolytes engineered for environmental resistance and high input/output characteristics. The company has also said the material has earned a strong reputation in the market.

What makes Mitsui especially interesting here is breadth. It isn’t only developing the electrolyte; it has also been developing and manufacturing cathode and anode active materials for lithium-ion batteries, and says it can customize those materials for all-solid-state designs. That “system” view—electrolyte plus electrode materials—gives Mitsui the ability to tune the chemistry as an integrated package, not just ship one ingredient and hope the rest works around it.

There’s evidence this work has already made its way into real products. Maxell’s all-solid-state battery uses materials developed in collaboration with Mitsui Mining & Smelting. Maxell has reported long-life performance enabling storage and charge/discharge cycles for more than ten years, and high-temperature resistance above 100 degrees Celsius.

Racing Toward Mass Production

As with most battery breakthroughs, the hard part isn’t making a promising material once. It’s making it reliably, safely, and cheaply—over and over, at industrial scale.

Back in November 2016, Mitsui Mining said it aimed to commercialize an electrolyte made with lithium sulfide for solid-state lithium-ion batteries as early as 2020. At the time, Kiyotaka Yasuda, a director at the company’s engineered materials sector R&D center, pointed to the growing expectations that all-solid-state batteries could deliver longer range, greater safety, and faster charging.

That 2020 timeline turned out to be ambitious. But the push didn’t stop. Mitsui has said demand for A-SOLiD has been rising as customers in Japan and abroad accelerate development toward commercialization for EVs and other applications. To respond, the company decided to carry out a “second enhancement” of capacity within an existing building, increasing the production capacity of its mass-production testing facility to roughly three times its prior level.

Then, in September 2024, Mitsui Kinzoku announced a bigger step: it would construct a new plant for the initial mass production of its sulfide-based solid electrolytes, A-SOLiD™, a category it identified as a key growth area.

The timing is telling. Mitsui noted that some customers were planning to launch EVs equipped with all-solid-state batteries around 2027, and that the prospect of its electrolytes being adopted as key materials was growing. The new initial mass production plant is planned for the Ageo area of Saitama, with operations scheduled to begin in 2027.

Japan's National Solid-State Battery Strategy

Mitsui’s solid-state bet isn’t happening in isolation. It lines up with a broader Japanese industrial push to regain leadership in batteries—a field Japan helped pioneer through early lithium-ion commercialization in the 1990s, but where Chinese and Korean players later scaled manufacturing and seized share.

In 2024, METI approved four R&D projects related to all-solid-state batteries, including projects involving Toyota, Idemitsu, Mitsui Kinzoku, and TK Works, aimed at materials development and breakthroughs in production technology. METI also announced the Battery Supply Assurance Program in March 2024, including subsidies totaling US$2.24 billion to cultivate Japan’s local EV supply chain and support all-solid-state battery technology.

Industry analysts have argued that Japan holds the world’s largest portfolio of all-solid-state battery-related patents and has been steadily building out a supply chain in hopes of reaching mass production.

For Mitsui, this backdrop matters. It’s external validation that solid-state is not just a corporate moonshot—it’s a national priority. And Mitsui is positioned alongside Toyota and Idemitsu as one of the entities receiving explicit government support.

The Toyota Connection

Toyota has targeted 2027–2028 for a market launch of battery electric vehicles using all-solid-state batteries. That schedule closely matches Mitsui’s planned 2027 start for its initial mass production plant.

Idemitsu has been working on R&D for all-solid-state battery elemental technologies since 2001, while Toyota began in 2006. Their collaboration has focused on sulfide solid electrolytes, widely viewed as a promising path to high capacity and output for BEVs. Sulfide solid electrolytes are often described as soft and adhesive to other materials—traits that can be advantageous in mass production.

Mitsui doesn’t disclose specific customer relationships. But it has indicated that automobile manufacturers are assumed to be the supply destination for products from the initial mass production plant. In other words: Mitsui is building for the EV launch window.

R&D Strategy and Future Bets

Solid-state batteries are the headline, but they’re not the only frontier Mitsui is funding. Its stated vision toward 2030 includes commercializing projects from its current R&D subjects and existing business units, with key areas that include next-generation semiconductor chip mounting and bio-manufacturing using algae. The company is also collaborating with the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi on green hydrogen production technology.

It’s a familiar pattern in Mitsui Kinzoku’s history: never depend on a single product cycle. Build capabilities that compound, then place multiple long-range bets so the company isn’t trapped waiting for one technology to break its way.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Strategy Lessons

The Reinvention Playbook

Mitsui Kinzoku’s arc—from a mining-and-smelting company tied to one of Japan’s most infamous pollution disasters to a critical supplier for modern electronics—offers a useful playbook for reinvention. A few principles stand out:

Build on core competencies, but be willing to change what they’re for. Mitsui didn’t throw away metallurgy. It re-aimed it. The same deep know-how that helps you separate zinc from stubborn ore—controlling chemistry, impurities, and microstructure—can also help you make copper foil clean and consistent enough for semiconductor packaging. The application changed. The underlying skill stayed.

Patient capital enables transformations that take decades, not quarters. Mitsui’s battery-materials story didn’t begin with EV hype. It started in 1949 with electrolytic manganese dioxide, and it kept going—through multiple generations of battery chemistries. By the time lithium-ion became dominant and solid-state emerged as the next frontier, Mitsui wasn’t starting from scratch. It was cashing in on a long, compounding learning curve.

Environmental crisis can force the strategy conversation you’d otherwise postpone forever. The itai-itai tragedy created a brutally clarifying question: if mining is no longer socially acceptable, politically defensible, or economically sustainable on its own, what is this company actually here to do? Mitsui’s eventual answer—specialty materials, electronics components, and a much heavier emphasis on environmental responsibility—didn’t just change product lines. It changed identity.

The Power of "Boring" Businesses

Mitsui Kinzoku is also a reminder that the most valuable positions in technology aren’t always flashy. Materials companies rarely get headlines, but they can end up owning the hardest parts of the stack.

Technical barriers make for durable moats. Mitsui didn’t win ultra-thin copper foil by out-marketing anyone. It won by solving manufacturing problems that are easy to describe and brutally hard to execute—like making foil at microscopic thicknesses, then getting it to release cleanly from a carrier, reliably, at scale. It’s the kind of advantage competitors can’t simply “copy” from a spec sheet.

Invisible supply-chain positions can be the most defensible. Consumer brands can swap suppliers for lots of components. But when a part is both mission-critical and difficult to manufacture—like five-micrometer copper foil—the supplier list gets very short, very fast. The less visible the component, the more painful it often is to replace.

Moving from commodity to specialty changes the economics. “Copper is copper” until it isn’t. The shift from mining and basic metals into engineered foil and advanced materials moved Mitsui away from commodity pricing and toward specialty pricing—where customers pay for consistency, yield, and process reliability, not just pounds of metal.

Navigating Catastrophe

The itai-itai case isn’t just history. It’s a long-running lesson in how corporate responsibility can reshape a business.

Long-term remediation leaves a mark on culture. Decades of cleanup obligations don’t feel like a normal corporate initiative. They change how an organization thinks about risk, process control, and environmental impact—especially in a world where customers and regulators increasingly demand evidence, not promises.

Stakeholder relationships can last longer than any strategy. The pollution control agreement forced ongoing engagement with affected residents and communities for years. What began as an adversarial relationship had to evolve into something more functional, because monitoring and remediation aren’t one-and-done problems.

Treating environmental obligations as investments can open unexpected doors. The mindset and capabilities built around pollution prevention and remediation can translate into adjacent areas—like exhaust catalysts and other materials that sit at the intersection of regulation, performance, and sustainability.

The Keiretsu Advantage

Mitsui Kinzoku’s membership in the Mitsui keiretsu adds another layer to how it was able to play the long game:

Patient capital from affiliated shareholders. Cross-shareholding structures can dampen the constant demand for immediate results, making it easier to fund long-horizon programs—like battery materials—without abandoning them when the market cycle turns.

Built-in relationships that can steady a company during transitions. Ties across the Mitsui Group helped provide stability while Mitsui Kinzoku climbed from legacy metals into higher-value materials.

Information flows across industries. When your network spans trading, finance, manufacturing, and technology, you’re more likely to spot shifts early—not because you can predict the future perfectly, but because you’re exposed to more signals than a standalone specialist would be.

IX. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Forces and Hamilton's Powers

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In standard PCB copper foil, the competitive set is already narrow. Fukuda, Mitsui Kinzoku, Furukawa Electric, and JX Nippon Mining & Metal collectively account for an estimated 40% of global production—an oligopoly built on scale, specialized equipment, and years of manufacturing refinement.

But the closer you get to Mitsui Kinzoku’s ultra-thin niche, the more “low” turns into “almost impossible.” This isn’t just a capital problem. It’s a repetition problem: keeping thickness, uniformity, and handling characteristics stable across rolls that run for thousands of meters, at micrometer-scale tolerances, batch after batch. That kind of capability comes from decades of accumulated process knowledge—knowledge that doesn’t transfer neatly through hiring or buying equipment.

Most innovation in the category is about staying manufacturable as requirements tighten: better peel control, improved surface properties, and stronger dimensional stability as circuits get denser. Environmental rules and hazardous-material restrictions add another hurdle, pushing producers toward cleaner, more sustainable processes. Substitutes—like aluminum foils or other conductive materials—remain limited threats, largely because copper’s conductivity and entrenched standards are hard to dislodge.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Mitsui Kinzoku buys key inputs on global markets—copper, precious metals, and rare earth elements for catalysts—where multiple suppliers exist and pricing tends to behave like a commodity. That keeps supplier power from becoming overwhelming.

At the same time, Mitsui isn’t purely at the mercy of spot markets. Its own mining history provides some vertical integration, and long-term supply relationships—such as with copper sources in the Philippines—help dampen supplier leverage and reduce volatility.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE TO HIGH

On the demand side, the customer base is concentrated. Smartphone giants, semiconductor substrate makers, and major chip fabricators can push hard on pricing and terms—especially in categories where multiple suppliers can meet the spec.

But ultra-thin copper foil is different. When Mitsui Kinzoku is effectively the only supplier that can deliver a critical material reliably at scale, buyer power hits a ceiling. Customers may be large, but the switching options are small—so the leverage shifts back toward the supplier, particularly when the material is tied directly to yield and product performance.

In other words: in commodity-like lines, buyers have more power; in specialty lines where alternatives don’t really exist, they have less.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For many applications, substitutes like aluminum foil exist in theory, but performance tends to be inferior, and standards are built around copper. In advanced semiconductors and ultra-thin applications, viable substitutes effectively don’t exist today—especially when you need a material that can be processed at scale without sacrificing conductivity and reliability.

Battery materials carry a different kind of substitution risk. Technology shifts can change what the market needs. Solid-state batteries, for example, could reduce demand for some materials used in today’s lithium-ion designs. Mitsui’s hedge is that it’s investing in that future too, through its work on solid-state electrolytes.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

Rivalry is real, but it’s not a chaotic free-for-all. Production is concentrated among a small set of major players, with the top ten manufacturers accounting for an estimated 75% of global output. Mitsui Kinzoku, Furukawa Electric, and Solus Advanced Materials are consistently ranked among the top three, each producing over 15 million square meters per year.

The competition is fiercest in technology and qualification wins, not pricing. Oligopolies tend to avoid destructive price wars, because everyone understands what that would do to returns on massive fixed investments. The real battles are fought through capability: thinner foils, better performance, new applications, and the ability to meet tighter tolerances at volume.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economies: Substantial. Ultra-thin copper foil manufacturing requires heavy fixed investment in specialized equipment, and unit costs improve with volume—advantages that favor established producers.

Network Effects: Weak. Customers don’t buy copper foil because other customers buy copper foil. The closest analogue is an ecosystem effect: once manufacturing lines and process windows are tuned to a supplier’s material, that supplier becomes the default.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate. Mitsui’s ability to span multiple pieces of a future solid-state battery stack—electrolytes plus electrode materials—looks meaningfully different from single-product component suppliers. Matching that posture would require competitors to broaden scope and reallocate investment.

Switching Costs: High in specialty products. Qualifying a new copper foil supplier for advanced semiconductor packaging can take months or years. Switching risks yield loss, delays, and product failures—costs that usually dwarf any small price difference.

Cornered Resource: Strong. Mitsui’s accumulated manufacturing know-how for ultra-thin foil behaves like a cornered resource: it can’t be purchased off the shelf, and replicating it takes time competitors may not have.

Process Power: Very strong. The ability to control release strength—uniformly, across huge rolls more than a meter wide and stretching for thousands of meters—is the signature of process power. It’s not one breakthrough; it’s organizational learning embedded in equipment, procedures, and workforce skill.

Branding: Weak in the consumer sense. But there is an “industrial brand”: a reputation for quality, reliability, and predictable performance that spreads engineer-to-engineer and becomes baked into specifications.

Competitive Position Summary

Mitsui Kinzoku’s strength depends on where you look:

- Ultra-thin copper foil: Near-monopoly, extreme barriers to entry. This is the fortress.

- Standard copper foil: Oligopoly market with steady competition and disciplined behavior.

- Battery materials: Strong foundation and credible momentum, but outcomes depend on how battery technology evolves.

- Automotive catalysts: Solid participant today, facing long-term pressure as EVs reduce demand for exhaust-related systems.

- Door components: Large presence in a defined niche, with meaningful scale but limited pricing power.

X. Key Performance Indicators and Investment Considerations

Critical KPIs to Monitor

If you’re trying to understand whether Mitsui Kinzoku is compounding its advantages—or quietly losing them—there are three things worth watching.

1. MicroThin Ultra-Thin Copper Foil Volume Growth

This is the company’s clearest scoreboard. Ultra-thin foil with a carrier is where Mitsui has the deepest moat, and it’s where demand should track the most valuable electronics trends: denser smartphones, more advanced semiconductor packaging, and faster communications infrastructure.

The practical way to monitor it isn’t through marketing claims. It’s through signals of real industrial pull: production capacity utilization, announced expansions, and whether those expansions actually come online on schedule. Mitsui has indicated capacity expansion plans running through 2030. If those plans accelerate, it suggests customers are pulling harder than expected. If they slip, it may signal a demand reset—or execution strain.

2. A-SOLiD Solid Electrolyte Production Milestones

Solid-state is the big option value in the story: the thing that could make Mitsui more than “the copper foil company,” and turn it into a critical EV-era supplier as well.

The milestones to watch are straightforward: - The initial mass production plant schedule (planned to start operations in 2027) - Evidence of customer adoption (the kinds of announcements suppliers can make without breaking confidentiality) - Whether production volumes ramp in a believable, industrial way - How Mitsui’s sulfide electrolyte stack looks versus competing approaches, including oxide electrolytes and semi-solid designs

Because this is a platform bet, timing matters. If the 2027 start date slips meaningfully, or if major customer prospects move in another direction, it would change how you underwrite the opportunity.

3. Engineered Materials Segment Operating Margin

Engineered Materials is where Mitsui earns its right to exist in the modern era. The segment’s margin is a shorthand for a lot of things at once: pricing power, product mix, manufacturing yield, and whether competitors are closing the gap.

If margins compress, it can mean the business is drifting toward commodity dynamics, or that the company is spending heavily to keep its lead. If margins expand, it’s usually a sign the specialty strategy is working—more high-value products, better mix, and sustained differentiation.

Bull Case

The optimistic view of Mitsui Kinzoku isn’t based on a single miracle. It’s based on multiple demand curves bending in the same direction.

Smartphones and semiconductors keep pushing complexity, keeping MicroThin volumes high and factories full. Even if smartphone unit growth slows, the compute intensity per device keeps rising—and advanced packaging for AI and high-performance chips becomes a new driver beyond phones.

All-solid-state batteries finally cross from promise to product, and Mitsui becomes a meaningful supplier of solid electrolytes. The industry’s current EV launch window around 2027–2028 creates a visible catalyst. If real-world performance improvements land the way proponents hope, adoption could move faster than today’s cautious timelines imply.

Japan’s national battery push provides tailwinds, with METI-backed projects and subsidies lowering some development risk and reinforcing the strategic priority of a domestic supply chain.

Mitsui’s broader battery-materials capabilities matter. It isn’t approaching solid-state as a single-ingredient vendor. The ability to develop electrolyte and electrode materials with an integrated mindset can be an advantage when customers care about how the whole cell behaves, not just one component spec.

Bear Case

The risk case is just as real—and it mostly boils down to what happens if the future arrives slower, or arrives differently than expected.

Smartphone saturation limits growth, and the core copper foil business matures. If upgrade cycles lengthen and volumes plateau, Mitsui can still be dominant and yet feel stagnant.

Solid-state commercialization slips, or the market shifts toward other designs where Mitsui’s sulfide electrolyte doesn’t become the default. In that world, years of investment may produce a smaller payoff than the headline narrative suggests.

Competition—especially from China—intensifies. Chinese producers have been expanding capacity quickly, and policy support for domestic supply chains could compress pricing or reduce opportunities in some markets.

Mobility faces structural pressure as EV adoption rises. Exhaust catalysts have a long runway, but not an infinite one. The key question is whether growth in battery materials and engineered products can outpace any decline in combustion-linked demand. Mitsui has already seen volatility tied to the performance of Japanese automakers in China—customers for ACT and catalysts—at the same time China’s EV shift has been accelerating.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

Mitsui’s history makes one point impossible to ignore: environmental liabilities don’t obey normal corporate timelines. The itai-itai case was formally resolved in 2013, but it stands as proof that remediation and accountability can stretch across generations of leadership.

Today’s risks are different, but they’re not trivial. Materials manufacturing can involve hazardous substances, and tighter rules around waste, emissions, and wastewater treatment can raise costs and force process changes. In a business where consistency and yield are everything, “cleaner” often means “more complicated,” at least in the short term.

Currency and input-cost exposure also matters. With a large share of sales in Japan and significant cost structures in yen, profitability can swing with exchange rates. The yen has weakened sharply at times—nearing 160 yen per dollar—yet higher energy and input costs can offset some of the benefit. Metal prices, foreign exchange, and energy costs can cut either way, and they can overwhelm operating improvements in any single quarter.

The Waiting Game

Mitsui Kinzoku’s story, more than anything, is a story about time horizons.

Its battery materials business has been built over generations. Its copper foil leadership was earned through long stretches of incremental engineering, not one breakthrough. And its solid-state battery bet—begun in 2016—still sits in that uncomfortable middle zone: promising enough to justify investment, but not yet close enough to mass adoption to feel inevitable.

That creates the central investment question: does the current valuation pay you for the wait?

Ultra-thin copper foil throws off value today. Solid-state electrolytes could be transformational, but they require years of continued execution before meaningful revenue arrives. Mitsui is, in many ways, a living example of what Japanese industrial policy often praises as patient capitalism. Whether that patience gets rewarded will be decided by factory ramp schedules, qualification cycles, and customer roadmaps—not by headlines.

What’s hard to dispute is the strategic positioning. Mitsui sits at critical junctions of the modern economy: the copper inside advanced devices, the materials inside next-generation batteries, and the process capabilities that make both manufacturable at scale. In an era defined by supply-chain fragility and technological competition, those are the kinds of positions that can quietly become priceless—even when the company holding them remains unknown to the people using the products it enables.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music