JFE Holdings: The Rise of Japan's Steel Colossus

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

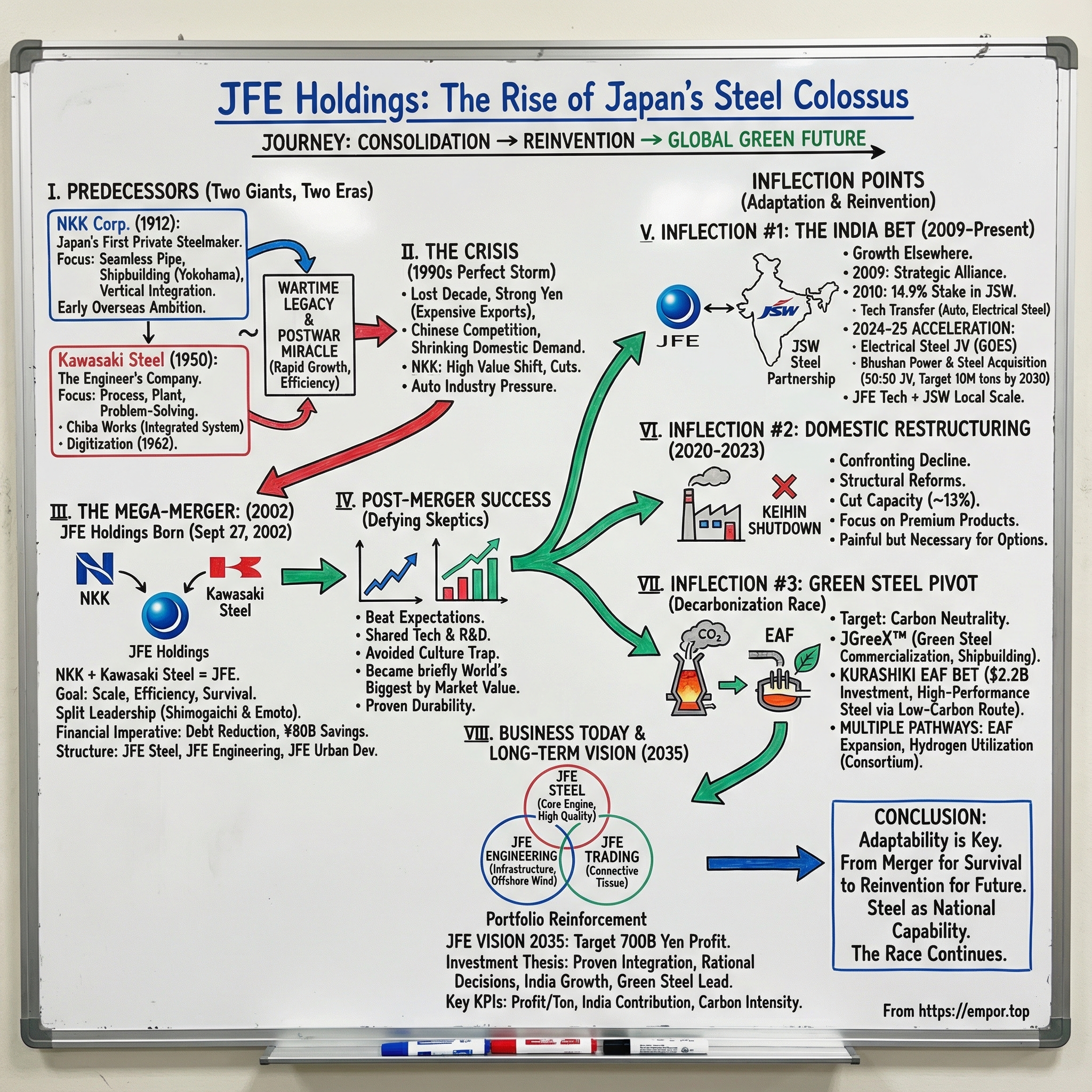

Picture Tokyo boardrooms in the year 2000. Two corporate giants—bitter rivals for nearly a century—sat across from each other as Japan’s economy slogged through its “Lost Decade.” The leaders of NKK Corporation and Kawasaki Steel Corporation were staring down an uncomfortable truth: on their own, neither had the scale or momentum to outrun the storm that was coming—Chinese competition, shrinking demand at home, and a global steel industry that was turning into a brutally efficient commodity business. Together, they might have a fighting chance.

What came out of those talks became one of the most successful industrial mergers in modern Japanese history: JFE Holdings. Today, it controls JFE Steel, the world’s fifth-largest steelmaker, with revenue north of $30 billion. JFE’s market cap sits around $8 billion—small for a company with such an outsized role in the physical world, but that mismatch is part of what makes this story interesting. This is not a software company. It’s a company whose products become bridges, ships, cars, power plants—the stuff civilization is built out of.

Even the name is a mission statement. JFE stands for Japan, Fe—the chemical symbol for iron—and Engineering. Not “cheap steel at any cost,” but steel as national capability: built on manufacturing discipline, process technology, and engineering know-how.

So here’s the question that drives the episode: how did a merger of two struggling 20th-century giants—pulled off in the middle of Japan’s economic malaise—turn into a company that now sits at the front edge of the global race for green steel?

The answer runs through a few big themes. Consolidation as survival—sometimes the only way to win is to stop competing and combine. The end of Japan’s steel miracle—how dominance gave way to reinvention. Decarbonization as a strategic pivot—betting that the industry’s next era will be defined by carbon-neutral production. And the India bet—recognizing that if Japan’s market is stagnating, the future has to be built somewhere else, even if that means partnering and sharing hard-earned technology.

This is a story about industrial evolution: about companies that refused to become museum pieces, and leaders who understood that in steel—as in life—standing still is just another way of losing.

II. The Predecessors: Two Giants, Two Eras

NKK Corporation: Japan's First Private Steelmaker

The story of Japanese steel doesn’t start in the glossy, postwar boom years. It starts earlier—back in the Meiji era—when Japan was sprinting to industrialize fast enough to stand toe-to-toe with the West.

In June 1912, NKK (Nippon Kokan) was founded as Japan’s first private steelmaker, led by Motojiro Shiraishi. The initial focus was seamless steel pipe—an unglamorous product until you remember what it enables: industry, energy, and a modern navy. Japan didn’t just need steel. It needed control over steel.

Launching a private steel company in 1912 was a statement. Steel was the kind of industry governments guarded closely, and much of the know-how sat outside Japan. Shiraishi and his backers at the Asano zaibatsu were betting that domestic capability wasn’t optional—that without it, Japan would always be dependent.

They built NKK’s first steel pipe plant in Kawasaki, Kanagawa, on Tokyo Bay. The map mattered. Tokyo Bay gave them efficient access to shipping lanes for raw materials coming in and finished products going out, right next to Japan’s industrial core. And the product choice mattered too: seamless pipe was specialized and high value, the kind of thing you could build a business around even before you had the scale of a national champion.

Then NKK did something that would feel very “Japan Inc.” for the next hundred years: it pulled the rest of the value chain toward itself. In April 1916 it launched the Yokohama Shipyard, using its own steel to build ships. That move—pairing steelmaking with shipbuilding—was early vertical integration in heavy industry: control the inputs, control the manufacturing, control the output.

Decades later, at the height of Japan’s bubble-era confidence, NKK looked overseas. In 1990 it acquired 50% of National Steel in the United States. By 2002, it had sold that stake to U.S. Steel. The arc of that investment—big ambition, hard reality—foreshadowed what NKK would learn the painful way: scale alone doesn’t guarantee success outside your home market, and steel is unforgiving if you misread the cycle.

Kawasaki Steel: The Engineer's Steel Company

If NKK grew out of zaibatsu financing and industrial strategy, Kawasaki Steel came from something more hands-on: shipbuilding.

Its roots trace back to 1878, when Shozo Kawasaki founded a shipyard. For a long time, steel existed there as support—something you made because ships needed it.

Kawasaki Steel became its own company after World War II, during the occupation-led dismantling of Japan’s industrial conglomerates. What had been the Steel Making Department inside Kawasaki Heavy Industries was incorporated as Kawasaki Steel Corporation in August 1950, spun out of the postwar breakup of the Kawasaki Dockyard.

The person who shaped what Kawasaki Steel would become was Nishiyama Yatarō. An engineer by training and temperament, he helped push the separation and then led the company. This mattered. Kawasaki Steel’s identity wasn’t built around finance or trading empires—it was built around process, plant, and problem-solving. Nishiyama believed steelmaking could be continuously improved through technology, and he ran the company like someone who actually meant it.

In the early days it used open hearth furnaces, but in the 1950s it built something far more ambitious: an integrated steel mill at Chiba Works, on reclaimed land in Chiba City. And in 1962, it put the blooming process at Chiba under computer control.

1962 is easy to read past—until you picture what “computer” meant then: room-sized machines, punch cards, and the idea that software could make heavy industry better. Kawasaki Steel was digitizing production control before most manufacturers had even imagined it.

Chiba Works embodied that engineering ambition. Built on land reclaimed from the sea, it concentrated steelmaking into a single, tightly managed system. Materials arrived by ship at dedicated port facilities, moved through blast furnaces and rolling lines, and left as finished steel without the inefficiencies of constant handoffs. It was industrial integration designed not just for scale, but for repeatable quality.

The Wartime Shadow

Both NKK and Kawasaki were deeply involved in wartime production, including military vessels during World War II. That legacy cast a long shadow. In the early occupation years, heavy industry was treated as the backbone of militarism—something to be constrained, even dismantled.

And yet both companies survived, then adapted, then prospered—helped along by the logic of the Cold War, which increasingly saw Japan’s industrial capacity as strategic rather than dangerous.

What followed became the postwar “steel miracle”: rapid reconstruction, booming demand, and Japanese mills that grew into some of the most efficient operations on the planet. But miracles don’t run forever. By the 1990s, the world had changed—demand patterns shifted, competition intensified, and the economics of steel turned brutal. Engineering excellence was still necessary, but it was no longer sufficient.

III. The Crisis: Why Two Rivals Had to Become One

The Perfect Storm of the 1990s

By the early 1990s, the mood inside NKK’s headquarters had shifted from long-range planning to damage control. This was a company built for an era when Japan was growing fast, exporting relentlessly, and rewarding scale. Now it was stuck in a world that had flipped on every assumption.

Global steelmaking had too much capacity. Cheap imports were rising. And the yen strengthened sharply, turning Japan from a great place to make steel into an expensive one. For a product that lives and dies on cost, that combination was brutal.

The currency story, in particular, was a slow-motion squeeze. After the Plaza Accord in 1985, the yen surged. And steel doesn’t have the luxury of high margins or weightless distribution. When exchange rates move against you, you can’t just “price through” it. A coil of steel that made sense when the dollar bought far more yen could suddenly become a loss-maker when that relationship tightened. The fundamentals didn’t change; the math did. And the math stopped working.

So NKK did what you do when the floor drops out: it tried to climb upward. It shifted toward higher value products—automotive steels, advanced pipes—anything where quality and engineering could buy breathing room. At the same time, it cut hard. The company reduced headcount from 22,214 employees in 1994 to 15,613 by 1998 and rationalized facilities to lower costs.

That kind of downsizing wasn’t just an operational decision. In Japan, where big companies had long been symbols of stability and lifetime employment, it was a cultural rupture. Behind those numbers were careers ended, families disrupted, and a recognition that the old social contract was breaking along with the old economics.

And still, the pressure kept coming. NKK’s overseas push—like the National Steel investment—had tied up capital it now needed at home. China’s steel industry was ramping up fast and exporting cheap volume into global markets. And domestic demand in Japan, once the industry’s bedrock, stagnated with the broader economy.

The Auto Industry Connection

Steel may feel like a commodity, but for Japanese steelmakers, the real battleground was often anything but generic. Their biggest customers were automakers—and the auto sector was changing.

As Japan’s economy slowed in the 1990s, automakers reduced orders and pushed suppliers on price. At the same time, Japanese steel producers faced intensifying competition from South Korean and Chinese mills, which kept tightening the pricing vise. For a steelmaker, that’s a nasty trap: lower volumes raise your unit costs, but customers still demand discounts. Lose share, and the problem compounds.

And unlike many industries, you can’t quickly swap customers or products. Automotive steel relationships are built around exacting specifications—precise grades, repeatable performance, deep integration into vehicle design. That stickiness is great in good times. In bad times, it means you’re exposed to the same customers’ downturns, with fewer easy pivots.

The Decision to Merge

By the end of the decade, “toughing it out” stopped being a strategy. Survival started to look like consolidation.

To remain competitive in a tightening market, Shimogaichi and NKK moved toward a deal with Kawasaki Steel, Japan’s third-largest steelmaker. In 2000 the two companies began sharing transportation and purchasing functions. A year later, they announced plans to merge.

That pre-merger collaboration mattered: it was a way to prove that two rivals could actually work together before committing to something irreversible. Because this wasn’t just a spreadsheet exercise. NKK and Kawasaki had spent decades fighting for the same customers, protecting their processes, and treating one another as the other side of the table. Now they had to align incentives, combine operations, and act like one team—without blowing up from pride, politics, or culture.

Shimogaichi put it unusually plainly: “We felt that NKK and Kawasaki, as they exist now, did not have the sufficient presence to compete successfully.” In the context of Japanese corporate life, that candor was the tell. Publicly admitting you weren’t strong enough—saying it out loud—meant the situation had progressed beyond normal crisis management.

The logic behind what would become JFE Holdings was simple and unsentimental. Global competition was getting fiercer. Scale and efficiency were becoming non-negotiable. Alone, these companies risked drifting into irrelevance. Together, they could build a platform with the size and capabilities to fight the next era of steel.

IV. The Mega-Merger: Birth of JFE Holdings (2002)

The Transaction

By the time the deal came together in 2002, NKK was Japan’s second-largest steelmaker and Kawasaki Steel was the third. On paper, combining them still didn’t topple Nippon Steel—the undisputed domestic heavyweight. But it did create a credible number-two with the one thing both companies had been missing through the 1990s: enough scale to rationalize production, cut costs, and stop bleeding in a market that no longer rewarded fragmented rivals.

In industry terms, this was seismic. The unification of NKK and Kawasaki Steel was the biggest move Japanese steel had seen since the 1970 marriage of Yawata Iron and Steel and Fuji Iron and Steel—the deal that created Nippon Steel. Everyone watching understood what this meant: a once-in-a-generation reset that would reshape the competitive map for years.

JFE Holdings was officially established on September 27, 2002 through a stock transfer that turned both NKK and Kawasaki Steel into wholly owned subsidiaries. Shareholders received one share of JFE Holdings for each share of Kawasaki Steel, and 0.75 shares for each share of NKK—creating a new parent with roughly 570 million shares outstanding.

That exchange ratio carried a message. Kawasaki’s shares converted at full value; NKK’s converted at a discount. The market was effectively voting on relative strength—Kawasaki’s technology and balance sheet were viewed as the sturdier foundation—and NKK shareholders accepted that haircut because the alternative wasn’t a better deal. It was a worse future.

The pitch for the merger was straightforward, and it wasn’t romantic: optimize production across plants, share technology, consolidate R&D, and use the combined footprint to compete more effectively with global rivals.

The Leadership Solution

Then came the question every “merger of equals” tries to dodge and eventually has to answer: who’s in charge?

JFE’s answer was carefully balanced. Shimogaichi became president of the new holding company, while Kawasaki Steel chairman Kanji Emoto took the role of JFE chairman. The arrangement wasn’t just about titles. It was a signal—internally and externally—that this wasn’t a takeover dressed up as a partnership. In a business where pride, legacy, and internal politics can quietly sabotage integration, splitting leadership was a pragmatic way to keep both sides invested in making the combination work.

The Financial Imperative

Beneath the strategy was a simple financial reality: debt. JFE set a goal to reduce interest-bearing debt to 1.80 trillion yen by the year ending March 2006, down from 2.53 trillion yen as of March 2001. Both predecessor companies had borrowed heavily to expand and modernize in earlier eras. Now, the combined company had to deleverage—without starving the business of investment.

The merger’s headline promise was annual savings of 80 billion yen. That number was the deal’s proof point: eliminate duplicate functions, coordinate production schedules across facilities, and use greater purchasing scale with suppliers. In other words, turn two overlapping steel empires into one operating system.

The Corporate Reorganization

Of course, signing the merger documents was the easy part. The hard part was turning two organizations—two cultures, two ways of running plants, two sets of internal loyalties—into one company that actually behaved like a company.

By April 2003, the structure snapped into place. JFE Steel Corporation became the core steelmaking arm. Alongside it, the group created dedicated entities for engineering (JFE Engineering Corporation), property management (JFE Urban Development Corporation), and research (JFE R&D Corporation).

The design followed a familiar Japanese playbook: a holding company on top, focused on capital allocation and strategy, with operating subsidiaries underneath that could focus on execution.

And the carve-up between the predecessors was telling. JFE Steel was created in 2002 as Kawasaki Steel absorbed NKK’s steelmaking business. At the same time, NKK’s engineering business absorbed Kawasaki Steel’s engineering operations to form JFE Engineering. Also in 2002, NKK’s shipbuilding business was spun off and merged with Hitachi Shipbuilding to form Universal Shipbuilding.

That shipbuilding move mattered because it showed what this merger really was: not an attempt to preserve everything, but a willingness to reshape the portfolio. If an asset didn’t fit—or couldn’t win at scale—JFE was prepared to set it free, even if it came with history attached.

V. Post-Merger Success: Defying the Skeptics

Beating Expectations

In the years right after the merger, JFE Holdings walked into a wall of skepticism. Big industrial combinations are supposed to be messy: bruised egos, incompatible systems, slow decision-making, and a long, expensive integration hangover. Most of the time, the “synergies” stay on PowerPoint.

JFE made the skeptics look lazy.

By 2004—barely two years after it was created—JFE had not only met its integration goals, it had become a model for how to coordinate a megamerger. And in a twist that surprised even people who followed the industry closely, JFE briefly became the world’s biggest steelmaker by market value.

That line matters. Market value is a vote on the future, not just a snapshot of tonnage and mills. Investors were effectively saying: this new company isn’t just larger—it’s better run, more coherent, and better positioned than its rivals. And it wasn’t because JFE had discovered some financial loophole. It was because the core business started performing like a single system instead of two competing empires.

The basic mechanics of why it worked are almost boring—which is exactly why they’re impressive. Kawasaki and NKK shared technologies. They stopped duplicating investments. They cut costs. They consolidated production so the network operated more efficiently, and they gained leverage with suppliers and with demanding customers like automakers and electronics companies. The cost target was clear from the start: cut annual costs by ¥80 billion by 2006.

The technology story was where the merger became more than just an expense-reduction program. Kawasaki Steel’s strengths in automotive grades paired well with NKK’s capabilities in construction materials. Research teams that had once guarded their work inside separate corporate walls could finally collaborate. Instead of two parallel efforts, JFE could focus talent and capital on the same problems—new alloys, better processes, higher-performance products—and move faster than either predecessor could have on its own.

Avoiding the Culture Trap

The most surprising part wasn’t the spreadsheet. It was the sociology.

Two proud organizations, each with a long history and deeply ingrained identity, somehow avoided the kind of culture clash that usually turns mergers into slow-motion civil wars. JFE didn’t erase those identities overnight, but it managed to get them pointed in the same direction.

A few things helped. First, the crisis that forced the deal was real enough that nobody could pretend the old world was coming back. When the alternative is decline, turf battles feel like a luxury. Second, the leadership solution mattered: with top roles split between the predecessor companies, it didn’t feel like a conquest. Third, the early agenda was concrete—cost reduction, debt paydown, operational coordination—so employees had measurable, shared objectives instead of vague integration slogans.

Nearly two decades later, the durability showed. In 2020, JFE Holdings ranked 365th on the Fortune Global 500 list—evidence that this wasn’t a short-lived burst of cost cutting. The merger created a company with staying power.

If you want the portable lessons, they’re straightforward. JFE worked because it solved a real strategic problem: in a steel industry that was consolidating globally, neither company had sufficient scale alone. The governance structure reduced the odds of internal warfare. And management anchored the integration around outcomes you could track, not aspirations you couldn’t.

VI. Key Inflection Point #1: The India Bet (2009-Present)

The Strategic Alliance Begins

By 2009, JFE had solved the merger problem. Now it had to solve the Japan problem.

The country’s steel market wasn’t going to rebound. An aging population and a maturing economy meant domestic demand would likely keep drifting down for years. If JFE wanted growth, it had to find it elsewhere. But “elsewhere” in steel is never a simple map exercise.

China was the obvious giant—but it was also building capacity at breakneck speed, turning itself into both the biggest customer and the toughest competitor on earth. The U.S. and Europe were large, but mature, politically sensitive, and full of entrenched players. India offered something different: huge demographics, fast industrialization, and a steel sector that was still fragmented—and, crucially, still had room to move up the technology curve.

So in November 2009, JFE agreed to partner with JSW Steel, India’s third-largest steel producer, to construct a joint steel plant in West Bengal. Then in July 2010, JFE bought a 14.9% stake in JSW Steel Ltd.

JSW wasn’t a random dance partner. Controlled by the Jindal family, it had what a foreign steelmaker can’t easily manufacture: access to domestic raw materials, deep relationships with regulators, and the local operating muscle to actually get things built. For JFE, the deal was a way into India without the all-or-nothing risk of trying to go it alone.

Even the equity stake felt engineered. At 14.9%, it was big enough to create real alignment, but small enough to avoid regulatory complications that could bog the relationship down. And alongside the capital, JFE started doing what it does best: transferring know-how. It licensed manufacturing technology for automotive steel and electrical steel sheets to JSW—effectively seeding Indian production with Japanese process discipline.

JFE later summarized the relationship like this: "Since we signed the strategic comprehensive alliance agreement with JSW in 2009, we have engaged in various collaborations and partnerships including capital participation; licensing of manufacturing technology for automotive steel and non-oriented electrical steel sheets; and a joint venture for the manufacturing of grain-oriented electrical steel sheet. Our relationship is now entering a new phase."

The 2024-2025 Acceleration

For more than a decade, the partnership was steady and deliberate. Then, in 2024 and 2025, it hit the accelerator.

The spark was electrical steel—specialized grades that sit at the center of electrification, from power transformers to EV motors. India’s build-out in power infrastructure and electrification created demand for exactly the kind of high-spec, hard-to-make products where JFE could contribute more than capital.

In February 2024, JFE Steel and JSW established JSW JFE Electrical Steel Private Limited, a joint venture for the production of grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES), aiming to build an integrated GOES manufacturing system in India. Around the same time, JFE Steel and JSW announced the acquisition of thyssenkrupp Electrical Steel India.

GOES is not commodity steel. It’s one of the most technically demanding materials in the industry, because its internal crystal structure has to be tightly controlled to reduce energy loss in transformer cores. Only a small number of producers globally can consistently meet the specifications required for power-grid equipment. Setting up GOES production in India wasn’t just “adding capacity.” It was a move to anchor the partnership in a premium, defensible product line tied directly to India’s long-term infrastructure build.

JFE Steel and JSW Steel also decided to significantly expand capacity across their electrical steel joint ventures—both structured as 50:50 grain-oriented electrical steel sheet manufacturing and sales companies. Together, they planned to invest about 120 billion yen.

That level of investment sent a clear message: this wasn’t a trial run. It was an attempt to build world-class capability in-market, at scale, with both partners fully committed.

The December 2025 Game-Changer

Then came the move that turned “strategic alliance” into something much bigger.

On December 3, 2025, JFE Steel and JSW reached an agreement for JFE to invest INR 157.5 billion (approximately JPY 270 billion) to transfer Bhushan Power & Steel Limited’s integrated steel facility in Odisha, India into a 50:50 joint venture. BPSL comes with an iron ore mine and an integrated steelworks in eastern India, with crude steel production capacity of 4.5 million tons per year.

And they weren’t buying it to keep it as-is. To meet India’s growing steel requirements, the joint venture planned to expand crude steel production at the site to 10 million tons by 2030.

JFE will invest INR 15,750 crore in two phases to acquire its 50% stake. For JSW, this fits into a much larger ambition: with a vision of reaching 50 million tonnes per annum of steelmaking capacity in India by FY2031, it sees enormous long-term potential in the market.

Zoom out, and the logic snaps into focus. Japan is a shrinking steel story; India is a growth one. Partnering with JSW lets JFE plug into that growth without taking on the full execution risk of building from scratch in a complex, unfamiliar environment. JFE brings technology and capital. JSW brings local scale, raw materials, and the operating and regulatory machinery to make the plan real.

For JFE, the India bet is an answer to the question hanging over much of Japanese industry: what do you do when your home market can’t carry your future? This partnership—patient at first, then increasingly decisive—shows what that answer can look like.

VII. Key Inflection Point #2: The Keihin Shutdown & Domestic Restructuring (2020-2023)

Confronting Decline

If India was JFE’s growth story, 2020 brought the part of the story every industrial company tries to postpone: the moment you have to downsize at home.

A pile-up of forces hit at once. Steel demand from manufacturers slumped as the U.S.-China trade war rippled through supply chains. Raw material prices climbed, pushed up by China’s increased steel output. And in Japan, demand wasn’t just soft—it was shrinking.

JFE Steel President Yoshihisa Kitano put it bluntly: "We are facing an unprecedented and extremely challenging operating environment due to slumping steel demand from manufacturing industries hit by the U.S.-China trade war and rising prices of raw materials driven by China's increased output of steel."

The subtext was even harsher. This wasn’t a temporary dip that you could ride out by waiting for the cycle to turn. Domestic demand was declining structurally. Chinese overcapacity kept resetting global prices. And the old playbook—keep the furnaces hot, spread fixed costs across volume, protect share—stopped making sense.

The financial hit made that reality impossible to ignore. JFE forecast an impairment loss of about 220 billion yen on production facilities in Chiba and Kawasaki, and it predicted a record 190 billion yen net loss.

There’s something symbolic about where those impairments landed. Chiba Works had once been a jewel of Kawasaki Steel’s postwar rise—a showcase of what Japanese manufacturing could do. Writing those assets down wasn’t just accounting. It was an admission that plants built for a different era were now dragging the company into the red.

The Historic Keihin Shutdown

JFE’s response was a set of structural reforms built around a simple idea: stop running Japan like it’s still the growth market. The company said it would shift its operating configuration from eight blast furnaces to seven, and reorganize production to focus more deliberately on the products where it could still win.

The headline move was Keihin. JFE Steel shut down the second blast furnace and related equipment in the Keihin area, cutting domestic crude steel capacity by around 4 million tons—about 13%.

That’s not a trim around the edges. Blast furnaces aren’t something you mothball for a quarter and restart when demand returns. Shutting one down means walking away from massive, long-lived equipment, unraveling a web of logistics and suppliers, and displacing highly specialized workers whose skills were built over decades.

And then came an even starker marker of finality: the company closed the last operating blast furnace at the enterprise, citing reduced domestic demand and intensifying competition from Chinese producers.

For the Keihin region—Kawasaki and the surrounding communities—this landed like an ending. Steel production there traced back to NKK’s founding in 1912. Generations had organized their lives around those mills. The shutdown wasn’t only a corporate restructuring. It was the close of a century-long chapter in Japanese industrial history.

JFE expected the reforms to contribute about 85 billion yen to annual profit. In a way, that figure echoed the company’s origin story: it was the same order of magnitude as the cost-savings promise that helped justify the 2002 merger. Once again, survival came down to taking fixed costs out of the system and reshaping the footprint to fit reality.

Strategic Implications

The Keihin shutdown exposed a hard truth about mature industries: sometimes the most strategic move is admitting what you can’t be anymore.

JFE couldn’t out-China China on commodity steel. It couldn’t justify overcapacity in a market that was steadily shrinking. And it couldn’t keep pouring capital into facilities that no longer earned their keep.

But by making the cut, JFE also bought itself options. Less drag at home meant more room—financially and organizationally—for what came next: scaling in India and investing in the technologies that could define the next era of steel. In that sense, the restructuring wasn’t surrender. It was a reallocation—turning a painful contraction into the foundation for a different kind of future.

VIII. Key Inflection Point #3: The Green Steel Pivot & Decarbonization Race

The Challenge

Steel is one of the most carbon-intensive things humans make at scale. The classic blast furnace recipe is brutally effective—use coal to strip oxygen out of iron ore—but it comes with a built-in consequence: huge volumes of CO2. As countries, regulators, and customers commit to decarbonization, steelmakers face a choice that’s less about PR and more about physics: reinvent the process, or get squeezed by carbon taxes, restrictions, and buyers who simply won’t accept high-emissions materials.

JFE has been unusually direct about what that reinvention entails: "Developing processes to mass produce high-performance steel with zero CO2 emissions is essential for a sustainable world. Huge R&D and equipment replacement costs will be inevitable as JFE executes strategies targeting carbon neutrality. Society must decide how these costs should be shouldered, including government support."

That’s not just a mission statement. It’s a warning label. Decarbonizing steel isn’t a “lean initiative.” It means betting on technologies that aren’t yet proven at full commercial scale, ripping out and replacing long-lived equipment, and spending enormous sums before the new processes are fully efficient. And it also means politics: JFE’s mention of government support reflects a reality everyone in heavy industry understands but doesn’t always say out loud—no single company can finance this transition alone.

JFE also put public stakes in the ground. It targeted an 18 percent emissions reduction in 2024 and above 30 percent in 2030. Its CO2e emissions targets were 47.6 million tonnes for 2024 and 40.7 for 2030.

For steel, those aren’t incremental improvements. Emissions are intertwined with the core production route. Hitting numbers like these requires more than tweaking operations—it requires changing how the steel is made.

JGreeX: Green Steel Goes Commercial

The pivot wasn’t only R&D and long-dated promises. JFE pushed “green steel” into the real world with JGreeX™, its reduced-carbon steel offering.

The proof point was symbolic and fitting: the world’s first dry bulk carrier made entirely with JFE Steel’s JGreeX™ green steel launched, and when the vessel entered service in September 2024 it was expected to be the first to receive the “a-EA (GRS)” designation, indicating a hull structure made of green steel materials.

Shipbuilding is a harsh test. It’s one thing to sell a low-carbon product in theory; it’s another to meet shipyard demands for strength, weldability, and reliability at scale. For a company with deep historical ties to shipbuilding, this milestone was JFE making a statement: green steel can be real steel.

And JFE didn’t keep it confined to Japan. In February 2024, JFE Steel started selling JGreeX™ green steel to Hock Seng Hoe, a leading steel wholesaler in Singapore.

Singapore matters here not because it makes steel, but because it moves it. It’s a distribution hub for Southeast Asia. Selling through a major wholesaler gave JFE a fast lane to regional customers without having to build an entirely new go-to-market machine.

The Kurashiki Electric Arc Furnace Bet

If JGreeX was the commercial front door, Kurashiki was the heavy machinery in the back.

JFE’s largest swing in decarbonization is a new electric arc furnace (EAF) project at its Kurashiki works in western Japan. JFE Steel committed a $2.2 billion investment in carbon-neutral steel production, backed by a government grant of up to $690 million. The plan is to build an EAF with 2 million tons of annual capacity and use it to produce advanced products—including electromagnetic and high-tensile sheets—that conventional arc furnaces have struggled to make. It also fits squarely into the Japanese government’s broader effort to decarbonize high-emission industries.

After Japan’s subsidy decision on April 9, 2025, JFE made the institutional decision to move forward with the Kurashiki innovative Electric Arc Furnace as the government-backed project.

The underlying technology shift is fundamental. Blast furnaces start with ore and rely on coal chemistry. Electric arc furnaces melt steel—often scrap—using electricity. If that electricity is low-carbon, the emissions profile can drop dramatically. The catch is quality: the steels that matter most for modern industry—electromagnetic steels for motors and transformers, high-tensile steels for safety-critical automotive parts—have historically been blast furnace territory.

So Kurashiki is a real bet: not just on decarbonization, but on cracking the hardest part of the problem—making high-performance steel through a low-carbon route. If it works, JFE gets a powerful first-mover advantage. If it doesn’t, the costs are measured in billions, not in bruised egos.

Multiple Technology Pathways

One thing JFE did right is not treating decarbonization like a single-lane road. Instead of wagering the company on one breakthrough, it pursued multiple pathways in parallel.

On EAFs, JFE Holdings planned a broader expansion: projects in Kurashiki (including high-quality steel sheet, with EAF refurbishment from 2027 to 2030) and Sendai (upgrading an existing furnace in 2024). These were expected to reduce annual emissions by 2.6 MtCO2 and 0.1 MtCO2, respectively. In 2025, JFE Holdings also planned to build a small new EAF in Chiba, expected to reduce CO2 emissions by up to 0.45 MtCO2.

And alongside the EAF track, JFE joined what amounts to Japan’s “moonshot” effort for steel: a consortium with Nippon Steel, Kobe Steel, and the Japan Research and Development Center for Metals, commissioned under NEDO’s Green Innovation Fund Project “Hydrogen Utilization in Iron and Steelmaking Processes.” JFE Steel decided to construct facilities at East Japan Works (Chiba district) to run demonstration tests.

Hydrogen is the most ambitious route—potentially transformational, but deeply difficult. In theory, hydrogen can replace coal in the reduction process and leave water as the byproduct. In practice, producing truly green hydrogen at the scale steel requires, and adapting ironmaking to use it reliably, remains a frontier engineering challenge. By joining a consortium, JFE is sharing costs and risk with its domestic peers while keeping a seat at the table if hydrogen becomes the winning pathway.

For JFE, this green steel pivot is both a growth opportunity and a high-stakes defense. The winners will capture customers who need low-emissions supply chains. The losers will face rising costs, tougher regulations, and dwindling access to premium markets. JFE’s multi-pathway strategy doesn’t eliminate the risk—but it buys something precious in heavy industry: options.

IX. The Business Today: Portfolio & Competitive Positioning

The Three-Pillar Structure

After all the big swings—mergers, shutdowns, and a full-on decarbonization pivot—JFE today is best understood as three businesses that reinforce each other: steel, engineering, and trading.

JFE Steel is the core. It produces and sells a wide range of steel products and raw materials, and it’s where most of the group’s revenue and profit are made. JFE Engineering builds and operates industrial and infrastructure projects across energy, the urban environment, recycling, steel construction, and industrial machinery and systems. And JFE Shoji is the connective tissue: it purchases, processes, and sells steel products, steelmaking raw materials, and nonferrous metal products—helping move volume, manage supply, and stay close to customers.

That structure isn’t an organizational chart as much as it is a legacy. NKK and Kawasaki weren’t “pure-play” steelmakers; they were heavy-industry ecosystems. The steel business remains the engine, but the engineering and trading arms add steadier cash flows and real strategic leverage—capabilities that would be hard to rebuild from scratch.

On the steel side, JFE Steel is one of the world’s major producers, with annual crude steel output of 23.2 million metric tons. In a world that makes more than two billion tons of crude steel a year, JFE isn’t trying to be the biggest by sheer volume. Its edge is where the industry gets harder: product quality, demanding customer relationships, and the process technology needed to consistently deliver higher-grade steels.

As of March 31, 2025, JFE employs approximately 61,300 people on a consolidated basis. That number is meaningfully lower than the combined workforce that came together in 2002, reflecting two decades of productivity gains, automation, and restructuring—culminating in moves like the Keihin shutdown that deliberately shrank the domestic footprint to match reality.

In Japan, JFE Steel is the country’s second-largest steel manufacturer after Nippon Steel. That rivalry has shaped the domestic industry for decades. Nippon Steel remains the heavyweight, but JFE has built strong positions in product categories where the winner is decided less by scale and more by capability—especially automotive steels and electrical steels.

Shipbuilding and Engineering

JFE’s shipbuilding and engineering threads run straight back to the company’s origins in integrated heavy industry—steel that turns into structures, vessels, and infrastructure.

On shipbuilding, JFE’s path is a story of consolidation inside consolidation. Universal Shipbuilding was created in 2002 when NKK merged its shipbuilding unit with Hitachi Zosen’s. Then, in 2012, JFE combined that shipbuilding business with Marine United Inc. of IHI to form Japan Marine United Corporation.

That means shipbuilding today sits with JFE as participation rather than ownership. Japan Marine United is a joint venture with IHI, giving JFE continued exposure to shipbuilding markets without having to carry the full volatility of a famously cyclical business on its own balance sheet.

Meanwhile, JFE Engineering has been leaning into where the world is going, not where it’s been. It completed construction of a monopile manufacturing plant in Kasaoka, Okayama Prefecture, with operations commencing in April 2024. Monopiles are the massive foundational structures that offshore wind turbines stand on.

It’s an almost perfect example of JFE’s broader story: old-school steel and fabrication expertise, redeployed into new demand. Offshore wind requires huge, heavy, precisely manufactured components—exactly the kind of work an engineering-centric industrial group can win if it’s willing to pivot.

X. Long-Term Vision: JFE Vision 2035

The Ambitious Target

JFE Holdings’ long-term plan, JFE Vision 2035, sets a clear north star: reach consolidated business profit of 700 billion yen. It’s an audacious number—and it’s meant to be. In a company defined by heavy assets and long cycles, a target like that isn’t a hope. It’s a commitment to remake how the machine earns.

Translated into plain English, that goal would mean a step-change from where JFE has been in recent years. And it doesn’t come from one magic lever. It comes from everything you’ve just heard in this story working at the same time: India turning into real growth, green steel moving from pilot projects to profitable volume, domestic restructuring continuing without breaking the organization, and premium product categories doing what they’re supposed to do—protect margins even when the cycle turns ugly.

To fund that transformation, JFE’s Eighth Medium-term Business Plan (FY2025–2027) allocates 1,840 billion yen to capital investment and strategic initiatives over three years. That spending level is the tell. JFE isn’t talking about change. It’s paying for it.

The Investment Thesis

For long-term investors looking at JFE Holdings, the story is unusually clean for an industrial company: there’s a credible plan, clear proof points, and very real ways it can go wrong.

The Bull Case: JFE already pulled off what most heavy-industry mergers don’t—an integration that actually worked. It then showed it can make painful, rational calls when the math demands it, like the Keihin shutdown. The JSW partnership gives JFE a path into the world’s most important incremental steel market without having to run India alone. And if its green steel push succeeds—especially in high-performance grades—JFE could earn a defensible position in a world where customers increasingly demand low-emissions materials.

The Bear Case: Steel is still steel. The industry faces chronic overcapacity, stubborn margin pressure, and relentless competition, especially from Chinese producers. Decarbonization is not only expensive; it’s technologically uncertain, and the returns may not justify the capital. Japan’s home market continues to shrink, forcing more restructuring over time. And even great operators can’t hedge away every macro variable—currency swings can still reshape profits overnight.

If you map this onto Porter’s Five Forces, the shape of the battlefield becomes familiar. Buyers are powerful—automakers and major manufacturers negotiate hard. Rivalry is intense. Entry barriers are high, but that doesn’t help much when the biggest competitors already exist and keep adding capacity. Substitutes are a real, growing consideration in some applications as alternative materials improve.

And through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, JFE’s strengths and weaknesses pop. Its real advantage is process power: a century of manufacturing expertise and continuous improvement that shows up in quality, yield, and product consistency. It also benefits from switching costs—once your steel is qualified into an automaker’s platform or an electrical application, changing suppliers is painful. But JFE doesn’t enjoy the same scale economies as the largest Chinese players, and it faces persistent pressure from competitors betting on different pathways to decarbonization and cost.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want to know whether JFE Vision 2035 is becoming real, there are a few indicators that matter more than the headline targets.

Profit per ton of steel shipped: This is the simplest scoreboard for whether JFE is actually moving up the value chain and running the network efficiently. If profit per ton rises over time, it’s a sign the product mix and cost structure are improving. If it stagnates or falls, the strategy is leaking—either through pricing pressure, higher input costs, or failure to shift away from commodity exposure.

India revenue and profit contribution: India is JFE’s primary growth narrative. What matters is whether the partnership and joint ventures translate into meaningful earnings power, not just announcements. As the ventures scale through the second half of the 2020s, this becomes a direct test of whether JFE can export its strengths—technology, product capability, operational discipline—into a market that’s growing fast but is operationally complex.

Carbon intensity per ton of crude steel: In the decarbonization era, this becomes a competitive stat, not a sustainability report stat. JFE’s ability to cut emissions while still making demanding, high-performance steel is the heart of the green steel bet. If this metric doesn’t trend down in a sustained way, the company risks falling behind in premium markets even if volumes hold up.

Risks and Regulatory Considerations

The risks are the ones you’d expect for a global steelmaker making big bets at the same time.

JFE remains exposed to China-driven trade shocks and pricing disruption. It faces execution risk on major projects, including the Kurashiki EAF investment. In India, regulatory shifts or policy changes could alter the economics of joint ventures that look attractive on day one. And currency volatility can materially move yen results for a business tied to globally priced commodities and internationally competitive exports.

There’s also a quieter risk that shows up in the footnotes before it shows up in the headlines: impairment. Steelmaking is capital-intensive, and the value of long-lived assets can change quickly when demand shifts or decarbonization timelines accelerate. With blast furnace facilities in particular, future writedowns are a real possibility if the world moves faster than expected. Investors should pay close attention to the assumptions behind these valuations—and to what auditors choose to emphasize in annual reports.

Conclusion

JFE Holdings exists because two proud rivals—NKK and Kawasaki Steel—chose survival over pride in the middle of Japan’s toughest economic stretch. The merger that created JFE in 2002 had plenty of ways to go wrong: culture wars, integration chaos, and a strategy that never moved past the press release. Instead, it became one of the rare megamergers in heavy industry that actually worked—and kept working.

But the victory lap didn’t last forever. JFE is now staring down a different, arguably harder set of problems. Japan’s steel demand continues its long decline. Chinese supply continues to pressure global pricing. And decarbonization isn’t a side project—it’s an economic force that can turn once-world-class blast furnace assets into liabilities faster than anyone would like to admit.

JFE’s answer has been to move on multiple fronts at once: expand in India through its deepening partnership with JSW, reshape the domestic footprint through painful moves like the Keihin shutdown, and spend aggressively on green steel technologies—especially the electric arc furnace pathway—before customers and regulators force its hand.

None of these bets are guaranteed to pay off. Carbon-neutral, high-performance steelmaking still has major technical and cost hurdles at full commercial scale. India offers enormous growth, but it also comes with regulatory and operational unpredictability. And shrinking the domestic base, while rational, can reduce the slack and redundancy that used to cushion Japanese steelmakers in downturns.

Still, the through-line of this story is not certainty—it’s adaptability. JFE’s leadership has repeatedly shown it’s willing to make unglamorous, irreversible decisions before circumstances make them unavoidable. The same clarity that pushed two rival empires into one company now powers its push overseas and its race to decarbonize.

And in the end, that may be what the name JFE really signals: Japan, iron, and engineering—not steel as a commodity, but steel as capability. If the industry is about to be remade, the companies most likely to survive are the ones that can reinvent how they make the material the modern world still can’t live without.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music