Niterra Co., Ltd.: The Spark Plug Empire Reinventing Itself for a Post-Combustion World

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

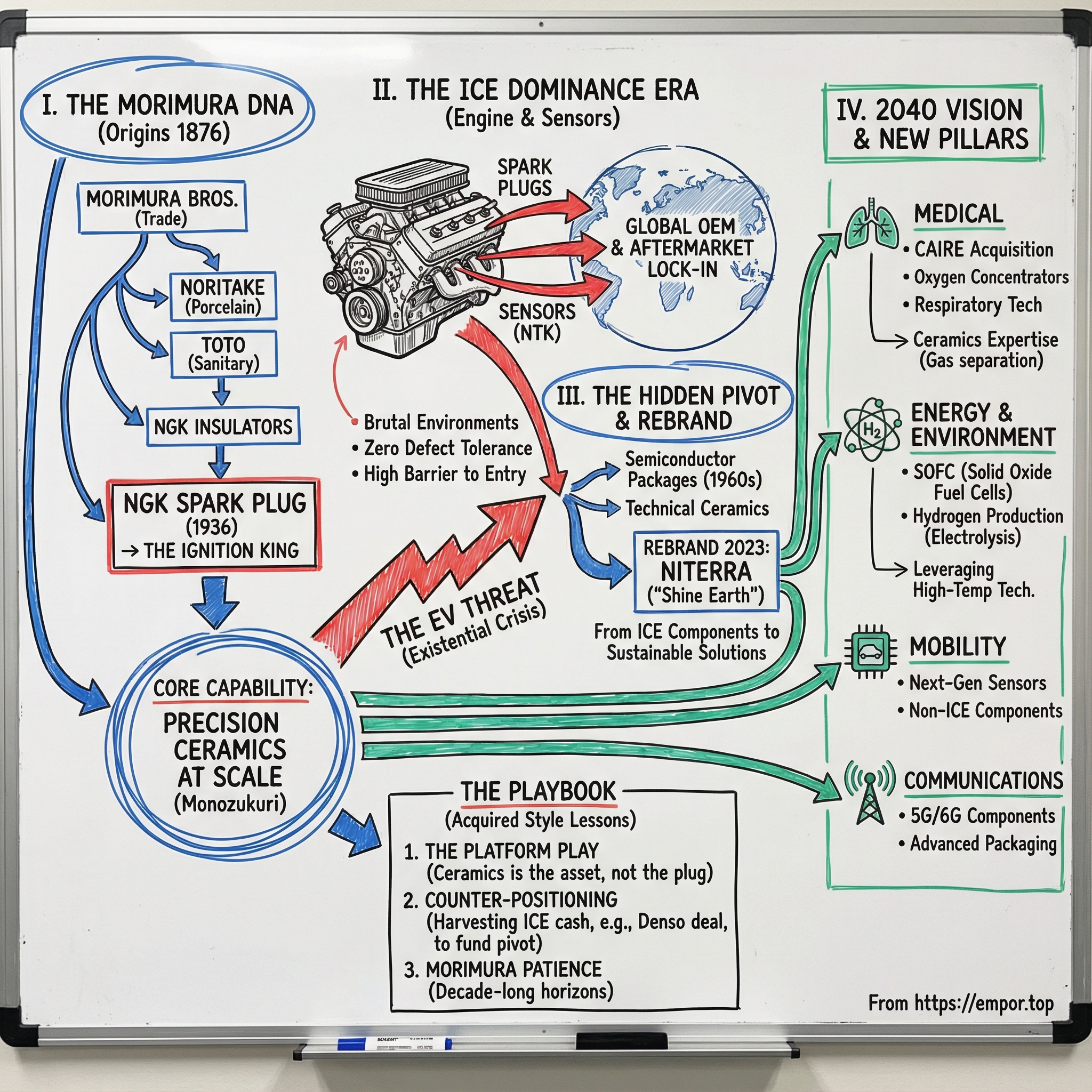

Picture a factory floor in Nagoya in 1937. The air is thick with ceramic dust. A young company, barely a year old, ships its first spark plugs—small, finicky components that have to survive heat, pressure, vibration, and thousands of explosions per minute. Those little ceramic-and-metal parts would go on to ignite Japan’s automotive rise.

Now jump forward nearly nine decades. The same company sits at the center of the global auto supply chain, shipping spark plugs at enormous scale and supplying automakers around the world. And it faces a question that would’ve sounded ridiculous to its early engineers: what happens when the world stops needing spark plugs?

That’s the problem with being great at internal combustion. If your reputation—and your name—are tied to the engine, then the moment the engine’s future looks shaky, you have to change.

Enter Niterra Co., Ltd., formerly NGK SPARK PLUG. In April 2023, the company changed its English-language name to “Niterra,” a coined word combining the Latin niteo (“shine”) and terra (“earth”). It’s a statement of intent: the company wants to be associated with making the earth shine, not with the emissions era.

This wasn’t a cosmetic rebrand. Under the corporate message “IGNITE YOUR SPIRIT,” Niterra has been pushing into growth fields it believes can carry it through the post-combustion transition: mobility, healthcare, environment and energy, and communications. In fiscal 2023 (to March 2024), consolidated revenue totaled 614.4 billion yen (about $4.4 billion USD).

Here’s the twist, though: Niterra isn’t a legacy industrial company waking up late to disruption. Its transformation is the latest chapter in a strategy that’s been forming for decades. Long before “EV transition” became a boardroom cliché, the company had already built businesses that don’t depend on spark plugs at all.

The secret isn’t spark plugs. It’s ceramics.

That’s what makes this story worth a full Acquired-style teardown. We’re going to track three threads. First, how a seemingly narrow capability—precision ceramics manufacturing—became a hidden strategic asset with applications far beyond automotive. Second, what transformation looks like when the core business is both cash-generating and structurally threatened, including a rebrand that had to be timed and executed perfectly. And third, what it says about Japanese industrial DNA—patience, process discipline, and an almost obsessive commitment to quality—that companies born from 19th-century trading houses can keep adapting without losing their identity.

Because despite the company’s global leadership in spark plugs since its founding in 1936, internal-combustion-related products were never the whole business. Over time, Niterra built real scale in sensors and technical ceramics—businesses that fit a world tightening emissions regulations, electrifying drivetrains, and demanding ever more precision components.

The Niterra story forces a set of uncomfortable valuation and strategy questions. How do you price a company when its flagship product is in long-term decline, but its core technology is increasingly valuable? When is a pivot a necessary reinvention—and when is it a distraction? And in a world that worships disruption, what is the advantage of a century-plus heritage that knows how to manufacture the hard stuff, at scale, over and over again?

II. The Morimura Group Origins: The DNA Behind the Company

To understand Niterra, you have to start with an unusually productive corporate family tree. This story doesn’t begin with engines. It begins with porcelain, global trade, and two brothers who believed Japan could win respect the hard way: by exporting products the world actually wanted.

The Morimura Group traces its roots back to 1876, when brothers Ichizaemon and Toyo Morimura founded Morimura Gumi (now MORIMURA BROS., INC.). Japan was in the midst of the Meiji Restoration, racing to modernize and compete with the West. Ichizaemon, a merchant, watched gold flow out of the country and took to heart the advice popularized by the scholar Yukichi Fukuzawa: bring wealth back by earning foreign currency through exports. So he decided to build an overseas trading business, not just for profit, but as a national project.

That same year, the brothers established operations in New York City. Ichizaemon set up Morimura Gumi in Japan and sent Toyo to New York to open an imported goods store under the Morimura Brothers name. The firm became a bridge for Japanese immigrants, students, and professionals—an early foothold for Japanese commercial life in the United States.

At first, they exported a broad mix: antiques, fans, dolls, miscellaneous goods. But over time, porcelainware grew into a bigger share of the business, and the Morimuras started to see something: demand was there, and quality was the differentiator. In 1889, Ichizaemon and his colleagues visited the World Exposition in Paris and were struck by the beauty and precision of European porcelain.

That trip flipped the ambition from selling porcelain to making it—at world-class standards. In January 1904, Morimura Gumi established Nippon Toki Gomei Kaisha to focus on manufacturing pottery and porcelainware. That company would later become Noritake, still one of Japan’s best-known tableware brands.

Then came the second-order effects—the part that matters for Niterra. The Morimura businesses didn’t just grow; they split and specialized. In May 1917, sanitary ware operations were spun off to form Toyo Toki Co., Ltd. (today: TOTO LTD.). Two years later, in May 1919, TOTO spun out its insulator department to form NGK INSULATORS, LTD.

And now you can see the pattern. Noritake. TOTO. NGK Insulators. Eventually NGK Spark Plug—what we now know as Niterra. A single origin point, Morimura Gumi, spawning multiple category leaders inside a shared theme: ceramics.

This is the key insight. These weren’t random diversifications. Each new company was a different end-market expression of the same underlying capability: precision ceramics. The Morimura approach was not “buy anything that grows.” It was “take one hard-to-replicate craft and keep finding bigger, more valuable problems it can solve.”

That’s why Ichizaemon’s legacy matters. He was known as an honest and dedicated man of commerce, driven both by personal determination and a sense of duty to his country. His path—from trade, to porcelain, to industrial ceramics—created a playbook that would repeat for decades.

And ceramics were the perfect platform. Japan had the raw materials, yes. But more importantly, the discipline required to make fine porcelain—patience, process control, an obsession with defects—translated directly into industrial applications. If you can make a flawless cup, you can make an electrical insulator that holds up under extreme conditions. The materials change; the mindset doesn’t.

Inside that mindset sits a philosophy that later becomes explicit at Niterra. To consistently deliver what customers demanded, Magoemon Ezoe emphasized discipline and a strong sense of participation from employees. That idea—“producing quality products” through the “participation of all employees,” across all workplaces—became part of the company’s inherited operating system, grounded in monozukuri.

Monozukuri is often translated as “the art of making things,” but that undersells it. In the Morimura lineage, it’s craftsmanship scaled into repeatable industrial excellence. It’s why the NGK and NTK names earned trust in automotive: not because spark plugs are glamorous, but because they’re unforgiving. They either work, every time, or your engine doesn’t.

For investors and strategists, this heritage explains something important about Niterra’s behavior today. The company is built to think in decades, not quarters—to accumulate deep technical skill, to protect quality as a principle, and to enter new markets only when it believes it can manufacture its way to leadership. That patience is a strength. It can also be a constraint. And it sets up the central tension of the modern era: when the world shifts fast, can a company designed to master the hard stuff, slowly and perfectly, reinvent itself quickly enough?

III. Founding and Early Years: The Spark That Lit an Industry (1936–1960s)

On November 11, 1936, NGK SPARK PLUG Co., Ltd. was founded in Nagoya with start-up capital of one million yen. A year later, the company was already shipping its first spark plugs. The product was tiny, but the mission was not: build a reliable domestic ignition component for a country racing to industrialize.

The timing was both perfect and perilous. Japan’s automotive industry was scaling quickly in the late 1930s, pushed along by military demand. Spark plugs were essential to every internal combustion engine, and the ability to make them at home—consistently, at quality—mattered.

Production began in April 1937. And from the start, the company made a bet that only made sense if you understood its parentage. Under the firm resolve of its first president, Magoemon Ezoe, NGK would produce plugs using porcelain—one of Japan’s specialties, and a direct inheritance from the Morimura ceramics lineage.

That choice wasn’t just patriotic; it was engineering. Spark plugs are deceptively hard. They have to live inside a combustion chamber where temperatures can soar, gases corrode, vibrations punish, and the whole system demands precise electrical insulation, cycle after cycle. The heart of that problem is the ceramic insulator—the barrier between the center electrode and the metal shell. This is exactly where decades of ceramics know-how, cultivated across the Morimura Group and NGK Insulators, became a real competitive advantage.

By 1937, the company reached a major milestone: mass production of its first NGK-branded spark plugs, aimed primarily at automotive engines. Those early plugs were built around durability and reliable ignition, and they quickly established NGK as a serious player in ceramic-based components for internal combustion.

Then the world changed. The war years disrupted production, but the post-war rebuilding of Japan’s economy—and especially its auto industry—created surging demand. NGK Spark Plug rode that wave. But the important strategic move wasn’t just “make more spark plugs.” Leadership chose to use automotive as the proving ground for something broader: industrial ceramics capability.

That intent became visible in 1949. Backed by its initial public offering that year, the company began launching a wider range of ceramics products under what would become NTK Technical Ceramics. The NTK brand, registered as a trademark at the end of 1950, signaled that NGK was thinking beyond engines even while engines paid the bills.

In 1958, the company began developing ceramic cutting tools and inserts—an expansion that still matters today. The logic was clear: spark plugs delivered volume and manufacturing discipline; technical ceramics opened the door to new applications and diversification.

And by the 1960s, NGK was pushing into a field that would define the next era of industry. After developing glass sealing, metallization, plating, and related process technologies, the company exhibited a 14-lead IC package at an IEEE show in the spring of 1967 and began production that fall. (IEEE stands for The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.)

This was barely a decade after the integrated circuit was invented. Spark plugs were still the bread and butter, but NGK Spark Plug was already building the capabilities that would matter in a semiconductor-driven future.

This is the throughline investors often miss when they look at Niterra today. From the beginning, the company treated automotive less like a destination and more like a platform—a high-volume, high-standard test environment where ceramics technologies could be developed, refined, and then exported into entirely different industries. The spark plug was the wedge. Ceramics mastery was the strategy.

IV. Global Expansion & Technical Leadership (1960s–1990s)

The post-war boom didn’t just lift NGK Spark Plug’s volumes. It pulled the company out into the world. And as it went global, it quietly did something even more important: it widened its definition of “ignition” from a single component to a whole set of ceramic-based technologies that could win inside an automaker’s most demanding systems.

The first big step came in 1959, when NGK built its first spark plug factory outside Japan, in Brazil. That was more than a flag in the ground; it was a declaration that this would be a manufacturing company with global reach, not just an exporter. The pace accelerated from there: a U.S. subsidiary in 1966, then Malaysia in 1973 and Indonesia in 1977.

That U.S. presence became the foundation for what’s now Niterra North America, Inc. It started with headquarters in California, then eventually relocated to Wixom, Michigan—right where you’d want to be if your customers are the automakers and suppliers clustered around Detroit.

Europe followed. In 1975, NGK established its first European subsidiary in England. By 1979, it had a dedicated presence in Germany as NGK SPARK PLUG Deutschland GmbH began operating in Ratingen. By the mid-1970s, NGK had manufacturing and sales operations spanning three continents.

But the most consequential expansion during this era wasn’t geographic. It was product.

The sensor business began in 1971, with temperature sensors for catalytic converter overheat alarm devices. Then emissions regulations tightened, and the industry standardized around the feedback fuel injection system: oxygen sensor plus three-way catalyst. In 1982, NGK developed zirconia and titania oxygen sensors and, in doing so, laid the foundation for what would become one of its most strategically important businesses. Around the same time, as catalytic converters spread across markets, NGK incorporated lambda sensors—oxygen sensors—into its portfolio.

This was the move that looks obvious only in hindsight. Oxygen sensors were, at their core, the same kind of problem NGK had always been good at solving: precision ceramics, manufactured consistently, at scale, with near-zero tolerance for defects. Spark plugs and oxygen sensors lived in the same brutal environment. They demanded the same process discipline. They sold into the same OEM relationships.

The difference was their future. Spark plugs are consumables, but they disappear entirely in a full EV world. Oxygen sensors don’t. Any vehicle with an internal combustion engine needs them to manage emissions—and that includes hybrids, which became more important as electrification arrived in phases rather than all at once. As emissions standards tightened globally, sensors became less of an accessory and more of a requirement.

Today, as the world’s largest manufacturer of lambda sensors, Niterra has continued improving oxygen and lambda sensor technology to help maintain an optimal air-fuel ratio. Back in 1982, no one called this a hedge. But that’s exactly what it became: a durable adjacent business, built from the same ceramic know-how, with a broader set of end uses than spark plugs alone.

None of this meant NGK stopped pushing the core product forward. Spark plug technology kept advancing, culminating in the start of NGK iridium spark plug manufacturing in 1997. Iridium-tipped plugs delivered longer life and strong performance in the higher-pressure engines that were becoming more common. By the early 1990s, worldwide production of NGK spark plugs had already crossed the five-billion-unit mark—a reminder of the sheer industrial scale the company had achieved.

And scale alone isn’t what makes an auto supplier powerful. Design-in does. During these decades, NGK deepened relationships with OEMs that would compound over time. NGK became one of the most trusted names in ignition systems, supplying original equipment spark plugs to Asian and American automakers for decades and building a reputation for consistency and OE-level specifications. Regionally, the market settled into familiar patterns: many Japanese manufacturers used NGK as original equipment, while several European brands, including VW, Audi, and BMW, often installed and recommended Bosch.

That’s where the real lock-in lives. Once a plug or sensor is engineered into an engine platform, switching is slow, expensive, and risky. Requalification takes time. Automakers don’t like surprises. Winning that slot tends to mean long runs of stable demand.

Even in the aftermarket—where buyers can choose—NGK’s brand strength showed up. In a 2023 survey of 317 certified automotive technicians, when asked which brand they most frequently install and trust, a majority chose NGK, followed by Bosch, with the remainder split among other brands.

By the end of the 1990s, NGK Spark Plug had achieved something rare: global leadership in its flagship product, plus a second major automotive franchise—sensors—that would only grow in importance as regulation tightened and powertrains evolved. The company’s methodical approach to expansion, local manufacturing, and long-term OEM partnerships wasn’t flashy. It was Morimura DNA in action. And it set up the next act: the moment when “spark plug company” stopped being a safe identity, and started becoming a strategic constraint.

V. The Ceramics Pivot: Building a Hidden Empire

To the outside world, NGK was a spark plug company. Inside the company, leadership was building something broader and, in the long run, potentially more valuable: a ceramics technology platform that could travel into semiconductors, industrial equipment, medical devices, and energy.

It’s true that the automotive franchise became enormous. Founded in 1936 to make spark plugs, the company’s core competence was forged in the automotive field, and over time its Automotive Components business grew into the world’s leading manufacturer of ignition and vehicle electronics parts across both original equipment and the aftermarket.

But the real story is what happened alongside that success.

One branch was semiconductors. Semiconductor packages are the unglamorous protectors of chips—the components that shield delicate silicon from heat and moisture while still carrying electrical signals into circuits that can be thinner than a human hair. These packages sit everywhere modern life sits: smartphones, cameras, and of course cars. As devices connected to the internet multiplied and communications moved toward next-generation standards, this kind of packaging became more essential, not less.

Then came an even more direct intersection with the chip industry: semiconductor manufacturing equipment. In the late 1980s, as chipmakers pushed for higher integration and lower cost, the equipment that made semiconductors started leaning harder on ceramics for one simple reason: ceramics can take punishment. They resist heat. They resist abrasion. They stay stable where other materials warp, degrade, or contaminate processes. Niterra responded by introducing ceramic electrostatic chucks, and in the 2000s it began mass production and expanded sales.

The underlying idea is worth pausing on. These electrostatic chucks are made of bulk ceramics and are designed to hold wafers securely while withstanding plasma and harsh process gases. Built into them are ceramic heaters that enable tight temperature control and high in-plane uniformity—exactly what fabrication demands as semiconductors keep shrinking.

This is the hidden strategic asset most investors miss when they hear the word “ceramics.” Niterra isn’t talking about pottery. It’s talking about engineered materials that survive extreme temperatures, aggressive chemicals, and precision requirements that keep pushing manufacturing to its limits.

The same pattern shows up elsewhere. The cutting tools division, which started back in 1958, became another serious ceramics application. Under the NTK Technical Ceramics banner, the company produces semiconductor-related products, fine ceramics, and products for the medical industry.

And industrial ceramic parts spread into all kinds of use cases. Niterra has offered solutions built from core ceramic technologies, including piezoelectric elements. Piezoelectric ceramics are materials that vibrate when voltage is applied, or generate voltage when pressure is applied—and that simple property opens doors across many fields. The company also produced ceramic bearing balls used in machine tool parts and inverter motors.

If the semiconductor work shows ceramics as the enabler of the digital world, the medical business shows ceramics as a bet on demographics. Niterra began researching medical applications of bioceramics in the 1970s, anticipating the opportunities that would come with an aging population. In 1999, it started selling medical oxygen concentrators.

That move pulled the company into a very different customer and regulatory environment—but it still leaned on familiar strengths: manufacturing discipline, materials expertise, and reliability in mission-critical environments. Over the last 20 years, Dr. Li’s work with both Niterra Japan and Niterra U.S. focused on new technology and business development across energy, environment, and medical devices. He played a key role in the commercialization of Niterra’s oxygen concentrator, solid oxide fuel cell, and biosensor and breath analysis for asthma patient care.

That list sounds scattered until you see the connective tissue. Spark plug insulators, semiconductor packages, electrostatic chucks, oxygen concentrators, fuel cell components: different markets, same underlying capability. Each new product line didn’t just add revenue potential; it deepened the company’s process knowledge and widened the set of industries where that knowledge could compound.

Niterra’s technology base reflects that breadth. It has developed specialized capabilities across the full arc of making advanced ceramics: blending materials down to nano-level particle sizes, shaping complex geometries, firing at high temperatures, and detecting “invisible” matter. Those technologies were refined through years of manufacturing and, while rooted in ceramics, were built to travel—supporting work in environment and energy, mobility, medical care, and communications.

Viewed this way, the “ceramics pivot” isn’t a side story. It’s the structural reason the company has options as the auto world changes. Spark plugs generate cash. The ceramics platform generates new paths forward—paths that are hard for competitors to copy, because the advantage isn’t any one product. It’s the accumulated ability to manufacture the hard stuff, reliably, at scale.

VI. The Existential Threat: EVs and the ICE Sunset (2010s)

By the mid-2010s, the mood in the auto world had shifted from “someday” to “soon.” Tesla’s Model S made EVs feel aspirational, not just responsible. China put real money behind adoption. European regulators started talking about timelines and bans. For a company whose English name literally contained the words “Spark Plug,” the message wasn’t subtle: the product that built the empire was tied to a technology the world was preparing to move beyond.

And if you strip the debate down to first principles, the math is brutal. Battery-electric vehicles don’t have combustion chambers. No combustion chamber means no ignition cycle. No ignition cycle means no spark plugs. Period. In a world steadily transitioning toward EVs, demand for Niterra’s signature product doesn’t just get competitive—it becomes structurally challenged.

That said, the story was never as binary as the headlines made it sound. Electrification arrived in phases, and the messy middle mattered. Hybrid vehicles, unlike full EVs, still have internal combustion engines. They still need spark plugs. In many cases, they need better ones—designed for frequent stop-start cycles and different operating conditions than a traditional engine sees.

That nuance showed up in the market. The Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. hybrid sales surged in 2024, growing faster than EVs. For Niterra, that wasn’t a footnote. It was a key extension of the runway. In places where charging networks lagged or consumer confidence in EV range stayed uneven, hybrids became the pragmatic bridge technology—and bridges, by definition, get built before the destination is finished.

In Europe and North America, the pattern was particularly clear: tighter emissions control pushed automakers and consumers toward “greener” options, but infrastructure constraints kept hybrids attractive. The result was a longer transition curve than the most aggressive EV forecasts implied.

Then there was the second leg of the stool: sensors. Oxygen sensors don’t disappear in a hybrid world—they become even more mission-critical. Hybrids constantly switch between electric and combustion operation, which demands tight fuel and emissions management whenever the engine is on. That played directly to Niterra’s strengths in ceramics-based sensing technology, giving the company a meaningful hedge even as spark plugs faced long-term decline.

On paper, the spark plug market itself still looked healthy in the near term. Industry estimates put the global market at a little over four billion dollars in the early 2020s, with expectations of gradual growth through the decade. But the more important point wasn’t the market size—it was where the durability came from.

Because the real cushion wasn’t new-car production. It was the installed base. Even as automakers shifted future lineups toward electrification, the existing global fleet of internal combustion vehicles would keep running—and keep needing maintenance—for years. The aftermarket, driven by replacement cycles as vehicles age, represented a long tail of demand that pure “new sales” EV projections often underweighted.

Still, Niterra’s leadership wasn’t going to confuse a long tail with a growth plan. Managing a business that declines slowly is still managing decline. The question wasn’t whether the company needed to change. It was whether it could turn its inherited advantage—80-plus years of ceramics process power—into new engines of growth.

In 2020, the company made its intent explicit with its 2040 Vision, “Beyond ceramics, eXceeding imagination,” and its 2030 Long-Term Management Plan, “NITTOKU BX.” Together, they framed the mission: use what made NGK great—materials expertise, manufacturing discipline, and reliability—to build businesses pointed in the opposite direction from spark plugs, where demand was accelerating and the company’s advantages could compound.

The strategic question was now unavoidable: transform, or die. Niterra chose transformation—but not by wandering into unrelated markets. The next chapter would be about finding new places where ceramics, sensing, and high-reliability manufacturing weren’t legacy skills. They were the ticket in.

VII. The Transformation Strategy: NITTOKU BX & The 2040 Vision (2020–Present)

A. The Rebrand: From NGK Spark Plug to Niterra

In corporate strategy, names matter. And a company with “SPARK PLUG” on the letterhead has a definitional problem when its future lies somewhere else.

By the early 2020s, management was staring at an uncomfortable reality: the English-language name NGK SPARK PLUG no longer described where the company needed to go. Worse, especially in Europe and the U.S., the name pulled attention back to the ICE business and made it easier to miss the company’s broader portfolio—and its desire to be seen as part of the solution on sustainability, not a relic of the emissions era.

So, after the 122nd Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders on June 24, 2022, the company announced a major change: it would rename the group in English to “Niterra,” effective April 1, 2023, the start of the next fiscal year. The rebrand was positioned as a reflection of what the group already was—an ignition, sensor, and technical ceramics specialist—and what it was trying to become next.

Crucially, this wasn’t a burn-the-bridges move. “Niterra” became the group name, but the iconic product brands stayed. NGK and NTK continued as the front-facing brands for their respective businesses, preserving decades of trust with automakers, distributors, and technicians.

This was smart brand architecture: remove the strategic constraint at the top, keep the hard-won equity at the product level.

“‘Niterra’ is a key milestone in the transformation which we are undergoing,” said Damien Germès, President & CEO of NGK SPARK PLUG EUROPE GmbH. “In the coming generations, it will be necessary to think even more about sustainability and what is good for the earth.”

B. The Four Pillars Strategy

The name change was the headline. The real work was the operating plan behind it.

In 2020, the company laid out its roadmap in the 2030 Long-Term Management Plan, NITTOKU BX, paired with its 2040 Vision, “Beyond ceramics, eXceeding imagination.” The idea was straightforward: focus investment and execution on four domains—environment and energy, mobility, medical, and communication—and use that focus to reshape the business portfolio over time.

To make that more than a slide, Niterra had already been building the machinery for reinvention. Starting in 2018, it created three Venture Labs—internal innovation hubs meant to incubate new products and businesses before the core started to shrink.

Then, on April 1, 2023, the organizational structure changed in a way that matched the strategy. The group aligned around the new identity—Niterra—and subsidiaries followed suit, including Niterra North America, Inc., reflecting years of preparation to expand beyond the automotive and ICE orbit.

The shift wasn’t just organizational; it was philosophical. Niterra introduced an in-house company system meant to clarify accountability and speed up decisions. A Global Strategic Headquarters was tasked with promoting groupwide management and maximizing business value according to each business’s position, under a policy of Dokuritsu-Jiei. Portfolio management tightened, including the use of hurdle rates by segment—an explicit attempt to treat businesses like capital allocations, not legacy entitlements.

And the most important sentence in the whole transformation plan was about money: cash generated by the ICE business would be used to fund growth and new businesses, while maintaining a baseline of financial soundness.

That is unusual clarity. The spark plug business wasn’t framed as a shameful past to abandon, or a melting ice cube to strip for parts. It was framed as the funding engine for the pivot.

Financially, the company reported that both sales revenue and operating profit hit record highs, and that performance targets for its medium-term management plan were achieved one year ahead of schedule. It also reported revenue growth from ¥455.9 billion to ¥485.7 billion, alongside operating profit rising from ¥87.9 billion to ¥103.3 billion.

The revenue mix showed both the challenge and the path forward. Automotive components still made up the majority of revenue, while a smaller but strategically critical segment—component solutions, including semiconductors, medical devices, and industrial ceramics—represented the growth vector. Regionally, sales were spread across major markets including the U.S., Germany, Japan, and China.

The plan, in other words, wasn’t to flip a switch. It was to manage the decline curve of ICE-related products while steadily shifting the company’s center of gravity toward businesses where ceramics, sensing, and high-reliability manufacturing are not a legacy advantage—they’re the whole game.

VIII. The Medical Pivot: Acquiring CAIRE and Betting on Healthcare

If the rebrand was the public signal that Niterra was serious about life beyond engines, the medical push was the proof. It’s the cleanest case study of the company’s transformation logic: take capabilities forged in brutal automotive environments—materials science, precision manufacturing, reliability—and redeploy them in a market where demand is growing for completely different reasons.

This didn’t start with a splashy deal. Niterra (then NGK SPARK PLUG) had been developing and selling medical-use oxygen concentrators in Japan since 1999. Over time, “medical” moved from an interesting adjacency to an explicit priority. Under its midterm policy of “Accelerating Current & New Businesses,” the company targeted three areas where it expected growth: environment and energy, next-generation automobiles, and medical. The message was consistent: keep advancing the core technologies built in automotive and technical ceramics, but start placing bigger bets where the future is pulling.

The step-change came in 2018 with the acquisition of CAIRE. On September 28, 2018, NGK SPARK PLUG signed an agreement to acquire CAIRE, Inc. and related companies for about $133.5 million. The deal brought in a set of oxygen-focused businesses: CAIRE in the United States, Chart BioMedical Limited in the United Kingdom, and Chart BioMedical (Chengdu) Co., Ltd. in China—leaders in respiratory-industry oxygen products, with oxygen concentrators at the center. Their portfolios extended beyond concentrators into liquid oxygen systems and oxygen generation systems used in hospitals and other institutions.

CAIRE itself had been part of Chart Industries’ biomedical segment, and it wasn’t a science project. It was already a global manufacturer of medical oxygen concentrators and other oxygen delivery equipment for people with respiratory conditions.

What made the acquisition feel “Niterra-like” is that it wasn’t framed as a leap into something unrelated. The strategic logic ran straight through the company’s existing strengths. Oxygen concentrators rely on molecular sieve technology—different from spark plugs, sure, but still rooted in the kinds of materials, process control, and quality discipline that Niterra had spent decades perfecting in sensors and ceramics. In other words: not a random diversification, but a transfer of core competence into a market with long-term tailwinds.

In the company’s own words, the acquisition “has proven to be a wise investment,” strengthening its global oxygen-related products business while CAIRE benefited from Niterra’s global value chain.

Then, unexpectedly, the world tested that thesis at full scale.

COVID-19 triggered a surge in demand for respiratory care equipment and put oxygen supply into the center of public health. NGK SPARK PLUG’s 2018 move suddenly looked less like a diversification initiative and more like business foresight, with CAIRE playing a meaningful role in oxygen supply equipment during the pandemic response.

The company didn’t stop at one deal. It expanded CAIRE’s diagnostics footprint in 2020 with the acquisition of Spirosure Inc., now CAIRE Diagnostics, and again in 2023 with the acquisition of MGC Diagnostics.

Zoom out, and you can see the medical playbook taking shape: pick a market where Niterra’s technical strengths actually matter, buy scale to establish a real position, plug it into the group’s manufacturing and distribution capabilities, and then broaden the platform through follow-on acquisitions and product development.

For investors, it’s a classic two-sided story. The opportunity is obvious: healthcare is structurally growing and far less tied to automotive production cycles. The risk is just as real: Niterra is competing in a field where regulatory expertise and established medical-device distribution networks can be decisive—and where incumbents have been learning those lessons for decades.

IX. The Hydrogen Bet: SOFCs and the Energy Transition

If the medical pivot is Niterra playing offense in a market with clear, near-term demand, its solid oxide fuel cell work is something else entirely: a longer-dated wager on how the world powers itself when carbon gets priced out.

At the center is the SOFC, or solid oxide fuel cell. In plain terms, it’s a device that generates electricity by reacting hydrogen with oxygen. Run the chemistry in the opposite direction—using electricity to split water—and you get hydrogen and oxygen. That “two-way street” is what makes solid oxide technology so intriguing: it can sit at the intersection of power generation and energy storage.

Niterra has been in this game for a while. In 2007, it developed a 1 kW-class SOFC power generation system. Later that year, it also developed a practically sized, lithographic SOFC that demonstrated a world-leading power generation output density—more than double that of conventional models at the time.

This is where the company’s ceramics story stops being a metaphor and becomes the whole point. SOFCs operate at brutal temperatures—roughly 700 to 1,000°C—and they depend on ceramic electrolytes that conduct oxygen ions while resisting degradation over time. Making those ceramics consistently, at high quality, isn’t an “energy startup” skill. It’s a precision manufacturing problem. And it looks a lot like the problem Niterra has been solving for decades in oxygen sensors and other ceramic-based components.

The structure of the bet is also very Morimura Group. Morimura SOFC, a majority-owned subsidiary of the Niterra Group, emerged from a collaboration across the family tree. Noritake, TOTO, NGK Insulators, and NGK Spark Plug (now Niterra) jointly concluded a memorandum of understanding to establish a joint venture for SOFC. In September 2019, the Morimura Group announced that these four companies were working together to form Morimura SOFC Technology Company.

That pooling matters. Each company brought its own SOFC-related technologies, and by combining them they could share development costs and accelerate commercialization. The ambition was clear: build high-efficiency power generation systems that work even at small scale, with applications spanning residential, commercial, and industrial use—and position SOFC as one tool to address energy and environmental challenges across those settings.

Then came an even more strategic step: reversibility. In 2024, Niterra announced a reversible SOC (Solid Oxide Cell) system—technology designed to both produce hydrogen through electrolysis and generate electricity from hydrogen. In other words, one cell stack that can switch between SOEC mode (making hydrogen by steam electrolysis) and SOFC mode (making electricity via fuel cell operation). Niterra described it as a reversible SOC system built on the SOC it already had under development, combining hydrogen production and power generation in a single-cell stack.

And in 2025, the company signaled it wanted to move faster. Niterra announced a partnership with AVL to develop and industrialize green hydrogen production technology. AVL brings expertise in energy and mobility system integration; Niterra brings decades of ceramic-based electrochemical technology experience, built in the automotive world through products like spark plugs and oxygen sensors. The partners’ goal is to scale and commercialize SOEC technology, which they argue can convert electricity into hydrogen more efficiently than conventional electrolysis approaches such as alkaline, PEM, or AEM.

AVL’s Owner and CEO, Prof. Helmut List, put the strategic rationale plainly: “SOEC is becoming increasingly important in the production of green hydrogen due to its efficiency advantage. The collaboration with Niterra is an important step in advancing the scaling of this key technology – with the clear goal of sustainably reducing industrial CO₂ emissions.”

In a way, the symmetry is perfect. Niterra built a world-class position in oxygen sensors—devices that measure oxygen in exhaust so engines can burn cleaner. Now it’s using that same ceramic and electrochemical foundation to target the infrastructure of a possible hydrogen future, including hydrogen production using solid oxide electrolysis cells.

But this is also the most uncertain bet in the portfolio. Medical devices and semiconductor-related ceramics can produce tangible revenue in the nearer term. Hydrogen infrastructure is a multi-decade thesis. If hydrogen becomes a major energy carrier, Niterra’s SOFC and SOEC capabilities could become disproportionately valuable. If it doesn’t scale, the returns may be limited—and the payoff timeline may test the patience even a Morimura-descended company is famous for.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

On paper, spark plugs look like a simple product. In reality, this is a category ruled by a handful of veterans who’ve spent decades earning the right to ship parts that sit inside a combustion chamber.

The competitive set is familiar: Denso, NGK, Bosch, BorgWarner, and Federal-Mogul. They dominate because they’ve built the things that matter most in auto supply: trusted brands, global distribution, and deep R&D. Denso and NGK, in particular, have long held frontrunner positions.

And the barriers to entry are brutal. Precision ceramics isn’t something you learn in a year; it’s accumulated know-how built over generations. OEM qualification takes years, with exhaustive testing and certification, and the cost of building a true global manufacturing network weeds out anyone without serious capital. Then there’s brand: “NGK” is effectively shorthand for “spark plug” in many shops. That kind of mindshare is a moat a newcomer can’t buy quickly.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

The core inputs—alumina and other ceramics materials, plus precious metals and rare earths—can generally be sourced from multiple suppliers. Niterra’s scale gives it leverage in purchasing, and its vertical integration in key steps of ceramic production further limits how much influence suppliers can exert.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

In OEM, the buyers are concentrated and sophisticated. Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen, and other major automakers negotiate hard on price and terms.

But they can’t treat every part like a commodity. Once a supplier is designed into an engine platform, switching becomes slow, expensive, and risky—requalification takes time and extensive testing. In the aftermarket, the power balance shifts: it’s more fragmented, and Niterra has more room to hold pricing through distributors and end customers.

4. Threat of Substitutes: HIGH (and Rising)

For spark plugs, the substitute isn’t another brand—it’s an entirely different drivetrain. Battery-electric vehicles eliminate ignition systems altogether.

The mitigating reality is that the transition is uneven. Hybrids keep spark plug demand alive, and the global installed base of internal combustion vehicles will require replacement parts for a long time. Meanwhile, sensors face a different substitution profile: they’re less exposed than spark plugs, and sensing needs persist across hybrids and in certain EV-related systems.

5. Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is a tightly contested market dominated by the usual suspects: Denso, NGK, Bosch, BorgWarner, and Federal-Mogul. Regional preferences shape the battlefield—NGK tends to dominate Asian OEMs while Bosch is deeply entrenched with European brands—but rivalry remains intense, especially in mature markets. In the aftermarket, where switching is easier, price competition can get particularly aggressive.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

This is where Niterra looks like a classic industrial fortress. At its plant in South Africa alone, it produces 22 million spark plugs annually. Across the global network, annual production capacity exceeds 1 billion units, shipped to more than 160 countries from 29 facilities worldwide.

That footprint spreads fixed costs across enormous volume and drives real cost advantage. The proposed acquisition of Denso's spark plug and sensor business would further increase scale.

2. Network Effects: WEAK

There aren’t meaningful network effects in traditional components manufacturing. Still, there are small hints of data-driven flywheels: Niterra’s integration with TecAlliance, an automotive aftermarket data platform, and the broader trend toward connected diagnostics could create modest network-like benefits over time.

3. Counter-Positioning: EMERGING

Here’s the tension: many competitors have been shifting away from ICE components toward electrification. Niterra’s approach has been to keep extracting value from combustion-related products while, at the same time, building new legs in areas like hydrogen and medical.

DENSO, for example, has stated it will continue to focus resources on electrification and clean energy, including hydrogen, aiming for sustainable growth. Against that backdrop, Niterra’s continued commitment to the combustion ecosystem—paired with long-range bets like SOFC—functions as a form of counter-positioning. The idea is that if others exit too early, Niterra can harvest the transition period while funding the next portfolio.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

In OEM supply chains, switching costs are real. Qualification takes years, and changing a component that lives inside an engine is not something automakers do lightly.

The same dynamic shows up in consumer behavior, too. There’s a simple rule of thumb many technicians follow: stay as close to your OEM plugs as possible. Use the same brand and type your car maker specified, because that’s what the engine was designed to work with. That habit reinforces stickiness and makes share shifts slower than outsiders often assume.

5. Branding: STRONG

NGK is one of the most trusted names in ignition. That brand recognition runs deep with technicians, distributors, and automotive professionals globally.

Importantly, it doesn’t have to stay trapped inside spark plugs. Under the broader NTK umbrella, the credibility built in the garage can transfer into adjacent categories—especially those sold through similar channels.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Niterra’s advantage isn’t a patent you can read—it’s a capability you have to live. Founded in 1936 as a spark plug manufacturer and tracing its roots back through the Morimura Group to 1876, the company sits on more than a century of ceramics lineage.

That accumulated ceramics expertise is a cornered resource: tacit manufacturing knowledge, institutional memory around quality control, and deep technical skill across ceramics applications. Competitors can invest, but replicating that full stack takes time—and, more importantly, repetition.

7. Process Power: STRONG

This is the Morimura inheritance made operational. The monozukuri philosophy—producing quality products through the participation of all employees—has been passed down through generations and embedded into how the company runs.

Precision ceramics manufacturing is extraordinarily difficult to copy. Materials science, process control, quality systems, and a culture that treats defects as unacceptable compound into an advantage that persists across products, cycles, and decades.

XI. The Competitive Landscape: Niterra vs. The World

Zoom in on spark plugs and exhaust-gas sensors, and the market has long looked like an oligopoly. Three names dominate the conversation: Niterra (through its NGK and NTK brands), Denso, and Bosch. Each has real technical depth, entrenched OEM relationships, and distribution that’s been built over decades.

Denso is Niterra’s most direct Japanese peer. Headquartered in Kariya, Aichi Prefecture, Denso became independent from Toyota Motor in 1949 and grew into one of the world’s broadest auto-parts suppliers. Spark plugs, ignition coils, filters, and sensors are just a slice of a much larger portfolio—which matters, because it shapes how Denso thinks about what to keep, what to exit, and where to redeploy capital.

Bosch is the other pole of the triangle. Founded in Germany, it’s a global automotive technology heavyweight, and Bosch plugs have long been especially common on European vehicles—helped along by deep relationships with European OEMs and the gravitational pull of “buy local” supply chains.

On the ground, this competition often looks less like a global free-for-all and more like regional gravity. Japanese and Korean vehicles frequently lean toward NGK or Denso. Many German and other European vehicles tend to skew toward Bosch (and other European brands like Beru or Hella). In the U.S., you’ll also see familiar domestic names like Autolite, Motorcraft, and ACDelco show up in garages and parts stores. Brand trust, OEM fitment, and installer habit carry enormous weight in this category.

Then, in September 2025, the structure of the industry shifted.

DENSO CORPORATION announced that its Board of Directors had resolved to transfer its Spark Plug and Exhaust Gas Sensor business—oxygen sensors and air-fuel ratio sensors—to Niterra Co., Ltd., with the two parties agreeing to sign a business transfer agreement following a board meeting on September 1, 2025. Niterra, for its part, announced the acquisition of Denso’s spark plug and exhaust gas sensor business for JPY180.6bn in cash.

If completed and integrated as described, the deal dramatically increases Niterra’s already-massive presence in a category where scale and OEM confidence are everything. Post-acquisition, Niterra is expected to control roughly 60% of the global spark plug market—a market valued at about $3.5 billion in 2024 and projected to grow over time, driven largely by hybrid adoption and continued internal combustion demand in developing markets. Put differently: by absorbing Denso’s share, Niterra turns leadership into something closer to inevitability.

The logic for both sides is unusually explicit. In the push toward carbon neutrality, electrified vehicles are expected to become more widespread. At the same time, powertrain diversification will continue because energy infrastructure and fuel needs vary dramatically by region. Against that backdrop, the companies positioned the transfer as a way to strengthen internal combustion product capabilities by combining technologies and manufacturing know-how—while freeing Denso to concentrate resources on electrification and clean energy.

Strategically, it’s a defining moment for Niterra’s transition-era playbook: doubling down on ICE-linked components while others step away. It’s counter-positioning in its purest form. The bet is that hybrids and the long tail of internal combustion—especially outside the richest markets—will last long enough to throw off meaningful cash. And a dominant position in spark plugs can translate into pricing power and efficiency, even if the category is slowly moving toward decline.

For Bosch, the implications are equally clear. It remains a major force, particularly in Europe, and continues investing in spark plug technology. But it now faces a competitor with even more scale, broader scope across plugs and sensors, and an increasingly consolidated position in a market where trust and manufacturing depth matter as much as innovation.

XII. Current State & Recent Developments

Today, the company sits in an interesting place in public markets: Niterra’s market capitalization is about $6.4 billion, on trailing twelve-month revenue of roughly $4.28 billion. It’s big, global, and profitable—but still priced like a business investors expect to be in transition.

Operationally, the footprint is exactly what you’d expect from the world’s ignition incumbent. Niterra operates 33 bases in Japan and 59 overseas, with more than 16,000 employees worldwide.

In Europe, the company has continued to modernize how it shows up. In May 2024, Niterra moved its EMEA Regional Headquarters in Ratingen to Balcke-Dürr-Allee 6, in the newly redeveloped Schwarzbach Quarter—part of a broader push aligned with sustainability goals and new ways of working.

Even as it works to change what the company is, Niterra hasn’t abandoned what made the NGK name famous: performance credibility. Its motorsport relationships keep the brand in high-stakes environments where “failure” is public and immediate. Niterra supplies the Scuderia Ferrari Formula 1 team. It was also the exclusive spark plug supplier for the IndyCar Series from 2007 to 2011, and since 2012 it has supplied Honda-powered IndyCar teams.

Financially, momentum has been strong. Operating profit rose 21% year over year, driven by price increases and the continued weakening of the yen. Shareholder returns moved up with it: the full-year dividend was raised from the prior forecast of 160 yen per share to 164 yen per share, based on a 40% payout ratio. And for FY2024, the company expected both revenue and operating profit to set new record highs.

The biggest near-term swing factor is still the Denso transaction. Subject to regulatory approvals, it would be the most significant catalyst on the horizon. The business transfer is expected to take place only after competition law authorities in all relevant countries and regions sign off, and after all other conditions are met.

Underneath the headlines, the long-arc investments keep moving. In hydrogen, the company and its partners have continued to push on solid oxide electrolyzer (SOEC) technology, aiming to develop, scale up, and industrialize it. The promise, as Niterra positions it, is meaningfully higher energy efficiency in converting electricity into hydrogen compared with approaches like alkaline, PEM, or AEM.

Meanwhile, the transformation portfolio keeps gaining weight. The medical business continues to build out diagnostics through CAIRE and its acquisitions. And the semiconductor-related ceramics business has benefited from sustained demand for precision components used in chip manufacturing—an area where Niterra’s “make the hard stuff reliably” advantage travels well beyond automotive.

XIII. Playbook: Strategic & Investment Lessons

1. The Platform Company Play

Niterra is a great example of a platform company hiding in plain sight. Spark plugs weren’t just the product—they were the volume engine that forced the company to get world-class at precision ceramics manufacturing, quality control, and global production. Once you can do that reliably, you can take the same skill set into other categories that reward extreme reliability: semiconductor components, medical devices, and energy systems. The bigger lesson is that the “main” business isn’t always the endgame. Sometimes it’s the training ground and the funding source that makes the next set of businesses possible.

2. Ceramics as Hidden Strategic Asset

If you only look at Niterra as a spark plug company, you miss what it actually owns: a hard-to-replicate ceramics capability that travels across industries. Spark plugs, oxygen sensors, semiconductor packages, oxygen concentrators, and solid oxide cells look unrelated from the outside. Inside Niterra, they rhyme. They all require materials expertise, tight process control, and manufacturing discipline in unforgiving environments. That’s why the key asset here isn’t a single product line—it’s the underlying technology platform.

3. The 50-Year Hedge

Niterra’s resilience didn’t start when EVs became fashionable. The company began building semiconductor packaging capability back in 1967, and it developed oxygen sensor technology in 1982—decades before anyone was making slide decks about the “EV transition.” That’s what long-term thinking looks like in practice: a set of adjacent bets that don’t seem urgent at the time, but become existentially valuable later. Today’s transformation isn’t a frantic pivot away from Tesla. It’s the speeding up of diversification that started generations ago.

4. Japanese Industrial Group Dynamics

The Morimura Group adds another layer to the story. Instead of one company trying to do everything, the model is to spawn related, specialized leaders—and still collaborate when the problem is big enough. The SOFC joint venture is the perfect example: multiple Morimura-linked companies sharing R&D costs, pooling know-how, and accelerating commercialization together. That kind of “family tree” structure creates knowledge transfer and strategic flexibility that a standalone company would struggle to replicate.

5. Identity vs. Strategy

The change from NGK SPARK PLUG to Niterra shows how identity can quietly become a constraint. A name isn’t just branding—it shapes how employees see the mission, how customers categorize you, how investors value you, and how future talent decides whether you’re building the next decade or defending the last one. Sometimes the boldest strategic move is admitting that yesterday’s identity has become too small for tomorrow’s strategy.

6. The Conglomerate Discount vs. Optionality

Niterra now lives in the classic tension that diversified industrial companies can’t escape. Investors often discount what they can’t easily model, especially when the portfolio spans very different businesses. Management, meanwhile, argues that the mix creates real optionality: a set of shots on goal that share the same core capabilities. The Denso deal intensifies that tension. It makes Niterra even more dominant in spark plugs and sensors, at the exact moment it’s also trying to build credibility in healthcare and hydrogen. That’s not a simple story to value—and that complexity can cut both ways.

7. Counter-Positioning in Declining Markets

As competitors like Denso step away from ICE-related components, Niterra is leaning in—consolidating share while others redeploy capital to electrification. The bet is threefold: that internal combustion (especially hybrids) lasts longer than consensus expects, that scale and concentration can create real pricing power even in a mature category, and that the cash flows from legacy products can finance the transformation. It’s a contrarian playbook. If EV adoption timelines stretch, it can look brilliant. If the shift accelerates faster than expected, the same strategy can turn into a very expensive commitment.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull case hangs on three big ideas: hybrids last longer than expected, ceramics gives Niterra real “options,” and management executes the transition without blowing up the cash engine.

Start with the simple reality: EVs don’t need spark plugs, but hybrids do. And hybrids aren’t just “ICE cars with a battery.” They put different demands on combustion engines—more frequent start-stop cycles, different heat ranges, tighter emissions control. That creates room for specialized plug designs that support cleaner, more efficient operation.

If hybrids remain a meaningful share of global auto sales deep into the 2030s and toward 2040—as many automaker roadmaps still imply—then Niterra’s ICE-linked businesses have more runway than the harshest EV curves suggest. In that scenario, the Denso deal is a classic transition-era land grab: consolidate an industry that’s slowly shrinking, use scale to drive cost and manufacturing advantages, and potentially gain pricing power even as volumes eventually taper.

The second pillar is what this whole story has been about: ceramics. Niterra’s ceramics platform isn’t one bet, it’s a portfolio of them. Semiconductor manufacturing equipment benefits from ongoing chip demand and the need for precision components. Medical oxygen concentrators ride structural tailwinds from aging populations and respiratory care needs. And the solid oxide fuel cell and hydrogen work is the longer-dated call option: if hydrogen scales as an energy carrier, the payoff could be disproportionately large.

Finally, there’s execution. So far, management has looked steady rather than flashy: record revenues and profits, medium-term plan targets achieved ahead of schedule, and a stated intent to use ICE cash flows to fund growth areas without abandoning financial discipline. If that continues, the transformation can be funded internally, not through a desperate scramble.

Bear Case

The bear case is the mirror image: EV adoption accelerates, the new businesses don’t scale fast enough, and the “double down on plugs” move becomes an expensive anchor.

There are already warning signs in demand volatility. Recent data points to a meaningful drop in global spark plug unit consumption in 2024, after peaking in 2023. Even if the exact drivers are mixed—replacement timing, macro conditions, shifting mix toward EVs—the takeaway is uncomfortable: the core category can turn faster than a long-cycle manufacturer would like.

If EV adoption speeds up materially—because batteries get cheaper, regulation tightens, or consumers simply move faster—then Niterra’s ICE profit pool could shrink quicker than its transformation timeline. Under that faster-transition scenario, the Denso acquisition risks looking like a smart industrial move made in the wrong decade: more exposure to a declining category just as the decline steepens.

Then there’s execution risk in the pivot itself. Healthcare devices and hydrogen systems are not “adjacent automotive.” They’re competitive arenas with different purchasing dynamics, different regulation, and different go-to-market requirements. Niterra brings manufacturing excellence, but scale economies and brand trust in spark plugs don’t automatically translate into durable advantage in medical or energy. If the company misjudges product-market fit, regulatory complexity, or competitive pressure, the returns on transformation investment could disappoint.

Finally, a near-monopoly position in spark plugs after the Denso acquisition invites scrutiny. Regulators could impose conditions that reduce the deal’s strategic value, delay integration, or limit how much pricing and scale benefit Niterra can actually capture. Competitors may also fight the combination in key jurisdictions, creating uncertainty at exactly the moment the company wants stability.

Key KPIs to Monitor

For investors trying to track whether the transformation thesis is working, three signals matter most:

-

Non-automotive revenue as percentage of total: This is the clearest scoreboard for portfolio shift. If this number doesn’t rise over time, “transformation” is mostly narrative. If it climbs steadily, the center of gravity is actually moving.

-

Operating profit margins by segment: The bet isn’t just that new businesses grow; it’s that they’re quality growth. Segment-level margins tell you whether diversification is building a stronger earnings base—or just adding revenue without real economic power.

-

Hybrid vehicle production volumes (industry-wide): Hybrids are the bridge that keeps plugs and sensors relevant. If global hybrid production holds up or accelerates, the bull case gets time. If hybrids roll over faster than expected as EVs take share, the bear case arrives early.

XV. Conclusion: The Art of Corporate Reinvention

Niterra is a case study in how a legacy industrial company can face technological disruption without trying to cosplay as a startup. The move isn’t to abandon the past. It’s to correctly identify what the company was actually good at all along—and then aim that advantage at the next set of problems.

The company’s own framing captures it well: “Our history, which began in 1937 with the manufacture of spark plugs, has always involved meeting the challenges of solving society's problems in response to the changing times. Having inheriting our commitment to technology and quality from the DNA of the Morimura Gumi, we will continue to rise to the challenge of creating new value and becoming a truly indispensable company through innovative manufacturing that opens up a path to the future.”

That sentiment matters because the spark plug was never “just a part.” It was a training regimen. A component that had to survive extreme heat, corrosive gases, vibration, and constant stress forced NGK—now Niterra—to master precision ceramics and relentless quality control. And that mastery, accumulated over nearly 90 years and rooted in the Morimura Group’s much longer ceramics lineage, is what now lets Niterra credibly play in semiconductor components, healthcare equipment, and solid oxide technology for a lower-carbon energy system.

The transformation, though, is still in progress. Automotive components still bring in the vast majority of revenue. The hydrogen economy remains a long-dated thesis, not a guaranteed payout. Medical devices are a tough arena with entrenched competitors and different rules of the road. And the Denso business transfer, as strategically compelling as it is, carries real uncertainty until regulators sign off.

So investors betting on Niterra aren’t just buying a “pivot.” They’re betting that management can run a two-speed company: keep harvesting and defending a massive ICE-linked franchise, while simultaneously building new legs that can stand on their own.

But the central question—what happens when your core product becomes obsolete?—has at least been met with strategic clarity. Spark plugs may fade. The capability that made them great doesn’t.

In a world obsessed with disruption, Niterra is a reminder that some of the most durable advantages aren’t flashy. They’re built on factory floors. They live in process discipline and tacit know-how. They compound quietly for decades—until a company that once put “SPARK PLUG” in its name can rename itself for a future where spark plugs don’t define it.

It was never really about the spark plug.

It was always about making the earth shine.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music