AGC Inc.: The 118-Year Journey from Japan's First Sheet Glass to Semiconductor Materials & Biopharma

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a young man—barely twenty-six—on the industrial edge of Amagasaki, Hyogo Prefecture, in 1907. His hands are gritty with sand. His clothes carry the dust of trial runs that didn’t work. This is Toshiya Iwasaki, and he’s doing something Japan has never successfully done at scale: making sheet glass at home.

Around him, modernity is loud. Steam engines wheeze. Chimneys cough smoke into the sky. And rolling through town are shipments of imported Belgian glass—the very product his startup is determined to replace.

Iwasaki loved the challenge. But he also understood the downside. He deliberately kept “Mitsubishi” out of the company’s name. If this failed, he didn’t want the embarrassment splashing back onto his family. That wasn’t modesty. It was risk management from someone born into Japan’s most formidable industrial dynasty.

Because the Mitsubishi zaibatsu—built by his uncle, Yataro Iwasaki—already dominated shipping, mining, banking, and heavy industry. But glass was different. Japan had tried, including through Meiji-era government efforts, and still couldn’t sustain even one viable sheet-glass operation. In 1907, this was a bet against history.

Now jump forward nearly 120 years to December 2025. The company Iwasaki founded is AGC Inc., headquartered in Tokyo—still one of the core Mitsubishi companies, and today the largest glass manufacturer in the world. But calling AGC “a glass company” in 2025 is like calling Apple a phone company or Amazon a bookstore. It’s technically true, and strategically misleading.

AGC is now the world’s largest manufacturer of EUV mask blanks, with more than 59% market share. These are the ultra-precise glass-and-film substrates that sit at the heart of extreme ultraviolet lithography—the process used to make the most advanced semiconductors on Earth. When TSMC, Samsung, or Intel builds leading-edge chips—whether they end up in AI systems like ChatGPT, autonomous vehicles, or frontier research—they’re relying on materials that only AGC and a tiny handful of others can produce.

At the same time, AGC spans five major segments: architectural glass, automotive glass, electronics materials, chemicals, and life sciences. As of June 30, 2025, it had trailing twelve-month revenue of about $13.7 billion. But the real story is where the company believes the next decades will come from: EUV mask blanks, biopharmaceutical CDMO services, and advanced fluoropolymers positioned for a hydrogen-powered future.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: how did Japan’s first sheet-glass maker become a global materials science powerhouse—supplying critical inputs for cutting-edge semiconductors while also operating contract manufacturing for modern biologic medicines?

The answer is a masterclass in corporate survival. It’s a story of repeated brushes with obsolescence—and reinventions that worked. It’s also a story about the trap of commodity businesses: brutal competition, thin margins, and, at times, the temptation to “stabilize” markets through cartel-like behavior. Over and over, AGC escaped that gravity by climbing the value chain into products where performance matters, qualification cycles are long, and customers don’t switch lightly.

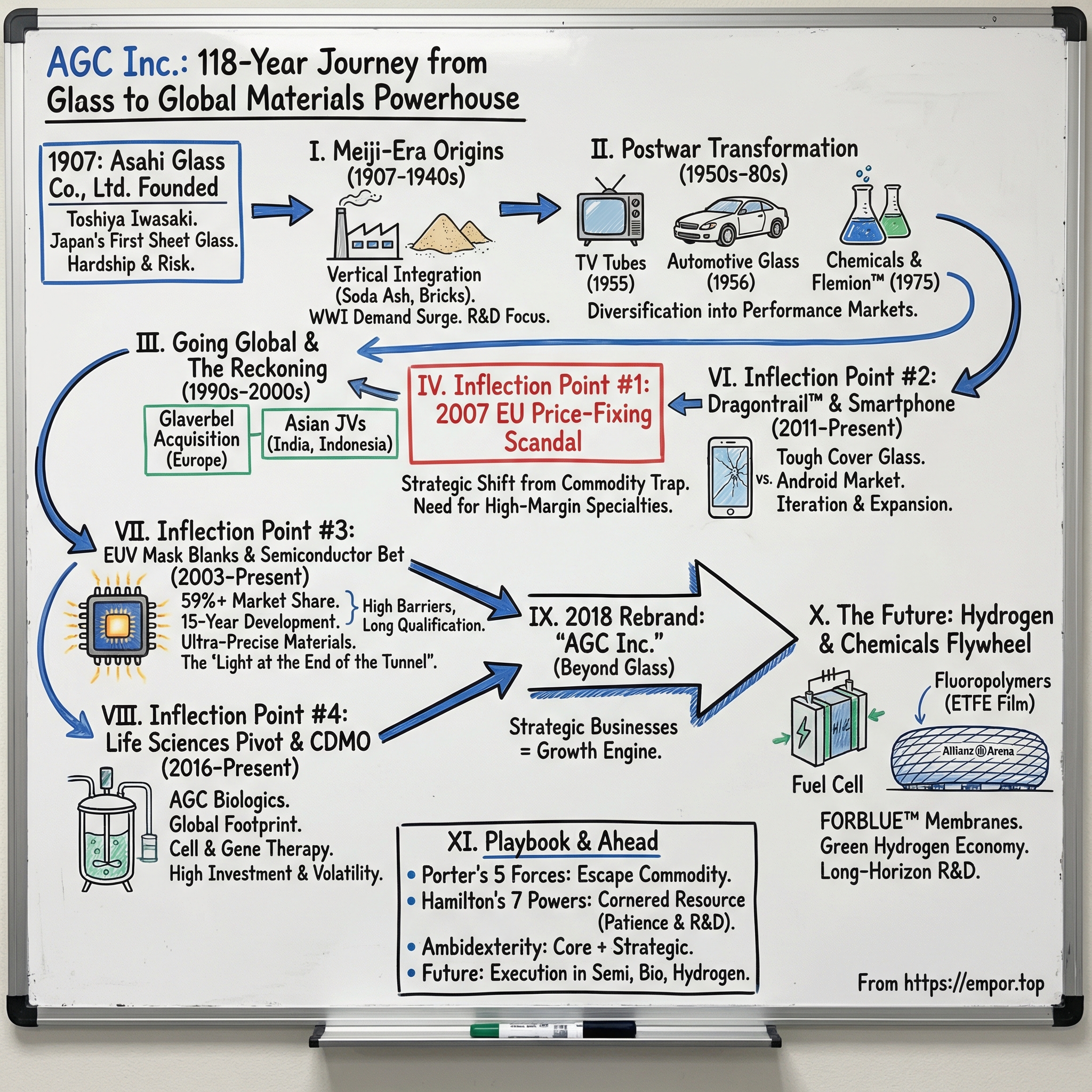

Our roadmap starts in the Meiji era, as Japan races to industrialize and Iwasaki tries to build the nation’s first true sheet-glass operation. Then we’ll follow AGC as it helps construct Japan’s industrial backbone, expands globally, and confronts moments that force reinvention: the 2007 EU price-fixing scandal, the smartphone boom and Dragontrail, the fifteen-year slog to make EUV mask blanks real, and the aggressive push into biopharma manufacturing. We’ll end in the present, where AGC is placing new long-horizon bets—especially in chemicals—on the coming hydrogen economy.

Along the way, we’ll use frameworks like Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton’s Seven Powers to separate the businesses with durable structural advantages from the ones that remain value traps.

It took vision, capital, patience—and occasionally a willingness to admit the old playbook was broken. Let’s start at the beginning.

II. Meiji-Era Origins: The Iwasaki Vision & Mitsubishi Roots (1907–1940s)

To understand AGC, you have to start with the family that made it possible.

Toshiya Iwasaki was born in Tokyo in 1881, into the inner circle of Japan’s most powerful industrial dynasty. His father, Yanosuke Iwasaki—the second president of Mitsubishi—had taken his brother Yataro’s hard-edged shipping venture and scaled it into a sprawling conglomerate.

But Toshiya didn’t grow up acting like a gilded heir. He avoided flashy clothes, visited the local public bath, pushed himself in sports, and was known for an uncommon stamina—he could swim long distances. More importantly, he showed a serious aptitude for science. That combination matters, because it foreshadowed a pattern that would define the company he built: hands-on, technical, and obsessed with manufacturing reality—not just finance.

He doubled down on that identity. He studied applied chemistry at the University of London, then returned to Japan and served in the Russo-Japanese War from 1904 to 1905. That war left a clear lesson for anyone paying attention: industrial self-sufficiency wasn’t a slogan. It was national security.

So when Toshiya looked for a problem worth solving, glass stood out.

Japan was modernizing at breakneck speed, adopting Western building methods that relied on flat glass. Construction was booming. Demand was rising fast. And yet Japan still depended heavily on imports—especially from Europe. The opportunity was obvious, but so was the danger. Glassmaking wasn’t a simple “build a factory and hire workers” industry. It was chemistry, heat, precision, and process control—an unforgiving craft that had already ruined multiple would-be competitors. Even the Meiji government had tried to establish domestic sheet glass production and failed.

That’s the context for what happened next: on September 8, 1907, Toshiya founded Asahi Glass Co., Ltd.—Japan’s first producer of sheet glass. (More than a century later, on July 1, 2018, the company would rebrand as AGC Inc., a signal to the world that it had become far more than “Asahi Glass.”)

Toshiya’s approach differed from earlier attempts in one crucial way: he wouldn’t pretend expertise could be improvised. Belgium was the world leader in flat glass, so he imported the best know-how he could—bringing in Belgian glassblowers to get production started properly. By 1909, it worked. Asahi produced Japan’s first flat glass, and it established a lead in domestic capability that proved hard for anyone else to catch.

That didn’t mean the business was instantly successful. Far from it. The early years were punishing: Asahi ran at a loss for its first seven years. Toshiya refused government aid, but he wasn’t shy about importing technology if it improved quality and output. And while the Mitsubishi family backing gave him staying power, what kept the company alive day-to-day was his intensity. He practically lived at the factory, debating methods with engineers, showing up in the foundry covered in sand and dust. This wasn’t a founder doing photo ops. This was a scientist trying to will an industry into existence.

And the reality of early-1900s Japan made the job even harder. The domestic industrial base was still thin. Reliable suppliers for key inputs didn’t always exist. So Asahi did what many great industrial companies do in their infancy: it vertically integrated out of necessity. In 1916, it expanded its Kansai factory to start producing its own refractory fire bricks for glass furnaces. In 1917, it began producing soda ash, a core ingredient in glassmaking. Later, the chemical side broadened further—caustic soda production began in 1933.

This is one of those “small” early decisions that ends up defining a century. AGC’s chemical business wasn’t born from a boardroom strategy session. It was born from the blunt logic of survival: if you can’t count on the supply chain, build it yourself.

Asahi also pursued process breakthroughs. It introduced the Lubbers glassmaking process from Europe to improve quality and productivity, and Toshiya went further—building a plant in Kyushu to deploy it at scale. That was a gutsy move for a company still bleeding red ink, especially with lenders turning cautious. Even Mitsubishi Bank refused additional credit as losses accumulated.

Then history intervened.

World War I choked off imports from Europe. Suddenly the glass Japan had been buying from abroad wasn’t arriving. Demand didn’t disappear—it simply had nowhere to go. Asahi, having invested in capacity and process during the hardest years, was positioned to catch the surge. The company finally broke into profitability, not because the business got easier, but because it had done the hard work before the market forced everyone else to.

Success didn’t make Toshiya complacent. It made him ambitious. He set out to reduce dependence on imported know-how by building original capability, establishing a research institute to develop new glass technologies and related chemical products. Notably, Asahi published much of the institute’s research, contributing to Japan’s broader industrial development. That choice—building a technical knowledge engine and treating it as a long-term asset—would echo decades later when AGC bet on advanced semiconductor and life sciences materials.

By the 1930s, Asahi had grown into a significant enterprise, and it expanded alongside Japan’s wider industrial push in Asia. It found markets and labor in neighboring China, and as tensions rose toward war, it shifted a substantial portion of its growing glass and chemical operations there—building 17 small plants. By the time World War II was underway, Asahi had roughly four times as many overseas plants as domestic ones.

The war years brought both consolidation and collapse. In 1944, the Japanese government merged Asahi with another chemical firm to form Mitsubishi Chemical Industries Limited—an explicit nod to the company’s deep Mitsubishi ties, which would remain important to its ownership and ecosystem. But the reorganization couldn’t outrun the reality of defeat. After Japan lost the war, Asahi lost its Chinese factories—those 17 plants were gone.

And that’s the origin story you need in your head to understand the AGC that emerges later.

AGC was born from privilege, yes—but forged in adversity. It was led by a scientist-founder who cared about process and materials more than optics. It learned early to make its own critical inputs rather than depend on shaky suppliers. And it institutionalized R&D as a core capability, not a luxury.

Those traits—vertical integration, materials expertise, and patience for hard technical problems—would later become exactly what you’d want if you were going to supply the world’s most advanced chipmaking process… or manufacture the next generation of biologic medicines.

III. Postwar Transformation: TV Tubes, Automobiles & Chemicals (1950s–1980s)

When the war ended, Japan’s industrial base was shattered. But reconstruction moved fast—and nothing rebuilds a country like concrete, steel, and glass. For Asahi Glass, that meant demand came roaring back.

Still, the company’s leadership could see the trap forming. Architectural flat glass was essential, but it was also destined to be a knife-fight business: lots of capacity, lots of competitors, and relentless price pressure. If Asahi wanted durable growth, it needed to take its glassmaking expertise into applications where quality and precision mattered more than price per square meter.

Then Japan’s consumers handed them the perfect tailwind.

In the 1950s, television arrived—and it didn’t just change entertainment, it changed aspirations. Households that had recently lived through deprivation now chased what became known as the “three sacred treasures”: washing machines, refrigerators, and television sets. Demand for TVs exploded, and every TV needed a cathode ray tube. And every cathode ray tube needed specialized glass.

In 1955, Asahi Glass began producing glass bulbs for CRTs, stepping into electronics materials for the first time. It was a pivotal move: instead of selling undifferentiated panes into a crowded building market, Asahi was now supplying a component that had to meet tight specifications, at huge scale, for a fast-growing consumer industry. It was exactly the kind of adjacency a materials company dreams about—close enough to leverage existing know-how, specialized enough to avoid commodity economics.

At nearly the same moment, Japan began its motorization era. Roads expanded, car ownership spread, and the family car went from luxury to expectation. In 1956, Asahi Glass started full-scale production of automotive glass. Like CRT glass, this was another step up the value chain: higher precision, stricter safety requirements, and a customer base that cared deeply about reliability.

These moves weren’t random diversification. They were a coherent strategy before it was fashionable to call it one: stay rooted in the company’s core capability—glassmaking—but climb into end markets where performance and manufacturing discipline created real barriers to entry.

Meanwhile, the chemical business that had started decades earlier as a supply-chain survival tactic kept growing. Asahi’s chlor-alkali operations—producing caustic soda and related chemicals—became substantial. But there was a problem baked into the industry’s standard process at the time: the mercury cell method. It worked, and it was widespread. It also created dangerous pollution.

By the mid-1970s, mercury pollution was no longer something Japan would tolerate. Regulation and public pressure tightened, and Asahi had to respond. In 1975, it developed the Flemion™ electrolysis method, producing caustic soda using ion exchange membranes instead of mercury. The breakthrough solved the pollution problem and reduced power consumption at the same time.

What started as a compliance-driven scramble turned into something far more valuable: a product. AGC launched its ion-exchange membranes in 1975, supplied them to more than 50 countries, and installed them across its own plants. Over time, Flemion evolved through multiple upgrades—from early series through later generations like the F-9010 and F-9060—adding specialized grades for different electrolytic cell types and operating conditions. The result was a strong position across major regions, including the United States, China, India, Europe, and Southeast Asia.

It’s an early glimpse of a pattern that keeps repeating in AGC’s history: constraints force invention, and invention becomes advantage. The mercury problem didn’t end the chlor-alkali business. It pushed Asahi into membrane technology—and out the other side as a leader.

By the 1980s, Asahi Glass had become something much broader than its original mission: a diversified materials company spanning glass, chemicals, and electronics materials. The CRT business, in particular, became enormous as television spread worldwide. But buried inside that success was another hard truth the company would have to face later: even “great” materials businesses can be temporary if they’re tied to a specific technology. CRTs wouldn’t last forever. Flat-panel displays were coming—and when they arrived, CRT glass would eventually disappear with stunning speed.

The period from the 1950s through the 1980s locked in the playbook AGC would rely on again and again: diversify away from commodity economics, invest in R&D to stay ahead, and turn external pressure into technical leadership. It worked here—and it would be tested much more severely in the decades to come.

IV. Going Global: The European & Asian Expansion (1990s–2000s)

By the 1990s, Asahi Glass had become a genuinely global manufacturer, with plants across Asia, Europe, and North America. But the move that really changed the company’s geography—and its identity—actually happened earlier, when it took control of Glaverbel, one of Europe’s most important flat-glass players.

Glaverbel itself was a product of postwar consolidation. It was founded in 1961 in Belgium through the merger of Glaver S.A. and Univerbel S.A. A decade later, in 1972, the French BSN group (today better known as Danone) gained control. Glaverbel restructured, then pushed into glass processing starting in 1974. And in 1981, BSN decided to exit flat glass. That’s when Asahi Glass stepped in and acquired Glaverbel.

For Asahi, it was the difference between exporting into Europe and being Europe. The acquisition turned the company from a primarily Asian producer into a global competitor with real on-the-ground scale. What became AGC Glass Europe was headquartered in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, and grew into the group’s European pillar. It employed around 14,500 people, with an industrial footprint that spanned Europe—float glass lines, automotive glass processing centers, and a dense network of distribution and processing sites stretching from Spain to Russia.

In Asia, the expansion followed a different playbook: partner locally rather than buy outright. In Indonesia, Asahi Glass entered a joint venture in the 1970s with PT Rodamas. Together they established Asahimas Flat Glass in April 1973, producing clear glass using the traditional Fourcault process.

India became an even bigger win. Asahi India Glass Ltd. (AIS) was incorporated in 1984 as a joint venture between the Labroo family, Asahi Glass Co. Ltd. (AGC) in Japan, and Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. AIS grew into India’s largest automotive glass manufacturer and broadened across automotive safety glass, float glass, and architectural processed glass. By 2017, AIS held a 77.1% share of the passenger car glass segment in India.

But globalization didn’t just bring new customers. It also made the underlying economics impossible to ignore. Flat glass was, at its core, a commodity business: brutal competition, huge fixed costs, and thin margins. A small set of giants—Saint-Gobain, Pilkington (later acquired by Nippon Sheet Glass), Guardian, and Asahi Glass—dominated the market, and the pressure to “compete” without competing was always there.

Inside the company, the central question was getting sharper: glass might be Asahi’s heritage, but could it really be its future? The flat glass business demanded massive, ongoing investment in float lines, yet struggled to produce attractive returns. And another clock was ticking, too. CRT glass—once a profit engine—was clearly headed toward obsolescence as flat-panel displays took over.

The direction of travel became clear, even if it would take years to execute: shift resources away from commodity glass and toward specialty materials where Asahi’s process discipline and R&D could earn premium economics. That road would eventually lead to things like Dragontrail, EUV mask blanks, and biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

But before the pivot could truly accelerate, the company was about to get shoved—hard—by a scandal that forced a reckoning.

V. Inflection Point #1: The 2007 EU Price-Fixing Scandal & Strategic Reckoning

On November 28, 2007, the European Commission dropped a decision that would have landed like a thunderclap in Tokyo. AGC Flat Glass Europe—still closely associated with its Belgian acquisition, Glaverbel—was named as one of four manufacturers fined as part of a flat-glass price-fixing cartel. The Commission fined the group of companies a combined 486.9 million euros for illegally coordinating price rises.

The Commission’s finding was blunt: in 2004 and 2005, the companies had raised or “stabilised” prices through illicit contacts. Neelie Kroes, the EU competition commissioner at the time, put it in plain terms: the EU would “not tolerate companies cheating consumers and business customers by fixing prices and depriving them of the benefits of the single market.”

This wasn’t some obscure corner of industry, either. Flat glass flows into the construction supply chain through processors—companies that turn basic sheets into double-glazing windows, fire-resistant glass, and mirrors, used everywhere from office towers to private homes. In the European Economic Area, the big four—Asahi, Guardian, Pilkington, and Saint-Gobain—held a combined share of at least 80% of the market. According to the Commission, they didn’t just discuss pricing in the abstract. They organized rounds of price increases, fixed minimum prices and other commercial conditions, and then monitored whether the agreed increases were actually implemented.

And that’s the part that matters strategically: the scandal wasn’t just a legal and reputational disaster. It was a tell.

When a commodity industry reaches for a cartel, it usually means the economics have become so punishing that even the incumbents don’t believe they can win honestly—through better technology, better operations, or better products. It’s less “bad behavior out of nowhere” and more a symptom of a business that’s structurally trapped: massive fixed costs, limited differentiation, and constant pressure to keep furnaces running whether prices are good or terrible.

The Commission’s process showed how serious the case was. Working with Member States’ National Competition Authorities through the European Competition Network, the Commission launched the investigation based on market information and carried out surprise inspections in February and March 2005 at the premises of Asahi’s and Guardian’s European subsidiaries.

Between those two rounds of inspections, Asahi and its European subsidiary Glaverbel—recently renamed “AGC Flat Glass Europe”—applied under the 2002 Leniency Notice. In other words: they cooperated with investigators in exchange for reduced penalties. It was pragmatic, and it was painful. Leniency is not a victory lap; it’s an admission that the old way of competing had crossed a line.

Inside AGC, the implications were bigger than the fine. This was a forcing function. Management had already been living with the uncomfortable truth that flat glass, for all its history and scale, was a brutal business to compound value in. Now the company had a public, high-profile moment that made it harder to hide behind tradition.

So the conclusion hardened: flat glass would remain part of AGC, but it couldn’t remain the core of AGC’s future. The company needed to move faster into higher-margin, higher-barrier specialty materials—businesses where you win by being better at chemistry, process control, and qualification cycles, not by trying to “stabilize” price.

In hindsight, the episode offers a clean lesson. When an industry’s leaders resort to collusion, it’s usually not because they’re blind to the risks. It’s because the underlying economics are unattractive. The real strategic response isn’t to wish for a more disciplined cartel. It’s to transform the portfolio. AGC chose transformation—and the next pivots would prove just how far beyond “glass” the company could go.

VI. Inflection Point #2: Dragontrail & the Smartphone Revolution (2011–Present)

In 2007, Steve Jobs walked onstage and introduced the iPhone. It wasn’t just a new phone. It was a new interface: a big sheet of glass you’d touch thousands of times a day. Corning’s Gorilla Glass protected that first wave, and almost overnight, “cover glass” became its own global battleground.

AGC saw what was happening. If screens were becoming the product, then the material covering those screens was about to matter a lot more than it ever had in the era of keypads and flip phones. In 2011, AGC launched its answer: Dragontrail™, an alkali-aluminosilicate sheet glass designed to deliver the smartphone-era bundle of requirements—thin and light, but tough; resistant to scratches; strong enough to survive daily drops and abuse. On a Vickers hardness test, Dragontrail is rated at 595 to 673.

Just as important as the material itself was how AGC could make it. Dragontrail is manufactured by the float process, a stable, high-throughput method that let AGC scale supply as the cover-glass market expanded worldwide.

The competitive chessboard with Corning shaped how Dragontrail won. AGC didn’t need to pry Apple away from an entrenched incumbent to build a real business. Instead, it leaned into Android manufacturers—especially across Asia—where the market was massive, product cycles were fast, and the value proposition was clear: durable cover glass at a cost profile that fit mainstream and budget devices. Dragontrail also proved well-suited for tablets and in-vehicle displays, where toughness and price discipline matter as much as brand prestige.

Over time, Dragontrail became a meaningful player in the category. It has been described as accounting for roughly 31% of the total market, with strong adoption across Asian smartphone brands. Its chemical composition is cited as offering about 30% higher scratch resistance than standard tempered glass, and it has been reported that around 45% of mid-range devices in Japan and China use Dragontrail as an affordable, durable option. One market research report also indicated demand for Dragontrail grew by 22% in 2024, driven by cost efficiency.

AGC kept iterating. The company told Android Authority that Dragontrail Star 2 was its latest protective glass as of 2024, and it has appeared on devices including the OnePlus 11R and the OPPO Reno 9 series. In 2024, AGC also introduced an ultra-thin Dragontrail Pro aimed at foldable smartphones, reducing thickness by 22%.

Still, Dragontrail also highlighted the limits of the position AGC had carved out. Corning remained dominant at the premium end—especially among Western manufacturers—and products like Gorilla Glass and Ceramic Shield set the bar for all-around top-tier performance. Dragontrail, by contrast, built much of its momentum where “good enough, reliably, at scale” wins: the enormous middle of the market.

And AGC didn’t stop at phones. Dragontrail expanded into adjacent use cases, including automotive displays, solar power equipment, and even space-related applications. AGC also emphasized the product’s environmental profile: lead, arsenic, and antimony are not used throughout the manufacturing process for the Dragontrail series, aligning with the company’s broader push to reduce lifecycle environmental burden.

In other words, the smartphone revolution did exactly what AGC hoped: it rewarded specialty glass with real technical differentiation far more than commodity flat glass ever could. But Dragontrail was only the visible part of a bigger shift in electronics materials—one that would soon culminate in a far more consequential bet for the company: EUV mask blanks.

VII. Inflection Point #3: EUV Mask Blanks & the Semiconductor Bet (2003–Present)

If Dragontrail was AGC learning to win in modern electronics, EUV mask blanks were AGC deciding to play at the absolute top of the semiconductor stack.

This was the company’s most consequential long-horizon bet: a development odyssey that took roughly fifteen years and ended with AGC sitting in one of the most strategically important choke points in chipmaking.

AGC started research and development on mask blanks for EUV lithography in 2003. The work didn’t begin because the market was already there. It began because AGC’s underlying capability—advanced synthetic quartz glass and obsessive process control—was good enough to get noticed. International SEMATECH, the U.S.-based semiconductor technology development consortium, recognized AGC’s technology and quality control and asked the company to participate in a project to develop mask blanks. For a materials company, that invitation is everything. It’s how you get pulled into the rooms where new standards are set.

To understand why this matters, a quick detour into what EUV actually changes.

For years, the industry relied on ArF lithography—light with a 193-nanometer wavelength—to pattern circuits on silicon wafers. As chip features shrank to around 20 nanometers and below, that approach increasingly required repeating steps multiple times to print what engineers wanted. It worked, but it made manufacturing more complicated and more expensive.

EUV lithography uses a much shorter wavelength—13.5—which enables those tiny patterns to be formed more directly. Less repetition. Less complexity. More progress.

And inside EUV, the mask blank is a critical starting point. A mask blank is the base substrate plate that becomes a photomask—built by depositing multiple optical films onto an ultra-polished, low-thermal-expansion glass substrate. If the blank isn’t perfect, nothing downstream can fix it. That’s why mask blanks are treated less like a commodity input and more like a precision instrument.

AGC’s ambition here was unusually bold: to be the one mask blanks manufacturer that could do everything, end-to-end—from glass material synthesis, to glass processing and polishing, to film deposition. That vertical integration is rare in this niche, and it’s a major reason the business is so hard to copy.

The development itself was grueling. AGC has described seeing “the light at the end of the tunnel” around 2014. In February 2018, with confidence rising that the technology was finally ready for prime time, the company decided to substantially enhance its supply system. By then, about 15 years had passed since the EUV mask blank effort began—an eternity by consumer tech standards, and pretty normal for advanced materials that sit at the frontier.

Today, the result is striking. The market is extremely concentrated, with AGC holding more than 59% share, and Hoya also among the key players with commercial delivery capabilities. That dominance isn’t just a scoreboard statistic; it reflects how brutally high the entry barriers are. EUV mask blanks are customized for each new generation of chips, which prevents commoditization. And once a chipmaker qualifies a supplier for something this sensitive, they’re reluctant to switch.

AGC didn’t treat this advantage as something to simply enjoy. It treated it like something to scale.

The company has been expanding capacity, with production beginning in January 2024 and a plan for gradual expansion that would lift EUVL mask blank capacity by roughly 30% by 2025 compared with then-current levels. AGC also said it hit its 2025 target of ¥40 billion in net sales for EUV mask blanks in 2024—one year ahead of plan—citing continued growth in semiconductor demand driven by AI.

The market’s growth expectations mirror that confidence. One estimate put the global EUV mask blanks market at about $591 million in 2024, projecting it to reach about $1.36 billion by 2031.

And AGC is already looking beyond EUV into what comes next: advanced packaging, where performance gains increasingly come not just from shrinking transistors, but from how chips are assembled.

Here the company is pushing glass-core substrates, positioned as a potential replacement for today’s organic substrates and polymer films used to mount chiplets—specialized integrated circuits assembled into larger systems. As packages grow larger and more sophisticated, the limitations of organic substrates become more apparent. Glass, as AGC has emphasized, offers properties that matter at the frontier: flatter, smoother, more resilient to heat and warpage, and capable of extremely precise fine-pitch holes.

AGC expects glass substrates to be introduced in the latter half of the 2020s, driven in part by growth in large data centers and AI-related demand. One estimate put the global glass core substrates market at about $195 million in 2024, projecting it to reach about $572 million by 2031.

Stepping back, the EUV mask blank story is the clearest expression of what makes AGC distinct. Many companies talk about long-term innovation. AGC funded it—year after year—through technology cycles, economic cycles, and leadership changes, until it turned into a real industrial position.

In advanced materials, patience isn’t a virtue. It’s the price of admission.

VIII. Inflection Point #4: The Life Sciences Pivot & CDMO Empire (2016–Present)

If EUV mask blanks were AGC’s bet on the cutting edge of computing, life sciences was its bet on the cutting edge of medicine—and it was, in many ways, the more jarring leap. Glass and chemicals are hard. Biologics manufacturing is hard in a totally different way: living systems, unforgiving quality systems, and customers whose stakes are literally clinical outcomes.

Strategically, though, the move had a familiar AGC signature. It’s counter-positioning in its purest form: traditional glass rivals can’t just decide to “follow” into biopharma CDMO. The talent, the regulatory muscle, the facilities, the customer relationships—none of it is adjacent to running float lines.

AGC entered life sciences the way it tends to enter difficult new arenas: by buying its way onto the field, then investing heavily to build a platform. Under its AGC plus approach, the company set an explicit growth ambition—expanding the business from ¥44.9 billion in 2018 to ¥135.0 billion in 2022 and to over ¥200 billion in 2025.

The logic was straightforward. The pharmaceutical world was shifting toward biologics, gene therapies, and cell therapies. These products are complex to develop and even harder to manufacture, and many drug companies prefer to outsource parts of that work to specialists. That is exactly what a CDMO is built for.

From there, AGC Biologics assembled a global footprint. It operated across the U.S., Europe, and Asia, with sites in Seattle, Washington; Boulder and Longmont, Colorado; Copenhagen, Denmark; Heidelberg, Germany; Milan, Italy; and Chiba and Yokohama, Japan. By this point it employed more than 2,600 people worldwide.

The company also pointed to real operating history: over three decades, it said it had worked with more than 250 customers across more than 400 projects, undergone more than 90 successful regulatory inspections, and supported 25 commercial product launches. Those launches included lentiviral vectors for a CAR-T therapy from Autolus Therapeutics and a gene therapy from Orchard Therapeutics.

And AGC didn’t just buy capacity. It built it.

The Copenhagen expansion captured the posture: big, long-term investment to become a scaled, trusted manufacturer. The new facility at the Copenhagen site opened after four years of work, backed by a major investment—reported as €200 million (about $239 million). It included a new manufacturing hall and eight new 2,000-liter single-use bioreactors, doubling the site’s manufacturing capabilities. Completed in June 2024, Copenhagen became the largest site in AGC Biologics’ network, with both mammalian and microbial manufacturing and process development.

Japan, meanwhile, was positioned as the next major frontier. AGC Biologics planned to begin cell therapy process development and clinical manufacturing services on July 1, 2025, at AGC Inc.’s Yokohama Technical Center—expanding the reach of its Global Cell and Gene Technologies Division. The point wasn’t just another building; it was geography and responsiveness. With cell therapy manufacturing available in three continents, AGC could better serve customers developing autologous and allogeneic products across markets. This work at the technical center was also framed as a lead-in to a new Yokohama manufacturing facility expected to be operational in 2027. As Santagostino put it, AGC Biologics wanted to become the CDMO of reference in Japan.

But this is where the story turns more complicated.

The CDMO business, especially in cell and gene therapy, proved more volatile than the growth projections implied. The broader biopharma environment shifted, and customers slowed R&D investment and stretched timelines for moving treatments forward. In that context, AGC Biologics announced a restructuring in late 2024, including layoffs effective November 22, 2024. A WARN alert indicated reductions across multiple U.S. sites: 68 employees at the Longmont CGT facility, 17 at the Boulder mammalian plant, and 10 in Bothell, Washington. The company described the driver plainly: fluctuation over the prior 12 to 18 months in the global biopharmaceutical business environment, which had negatively impacted CDMOs and other manufacturers.

By 2025, Santagostino described a “rational realism” taking hold among customers—after years that swung between exuberance and pessimism. With CGT overcapacity, he characterized the environment as a buyers’ market: customers more selective, contracts harder to win, and a shakeout likely, with some CDMOs going out of business. In that framing, buyers increasingly wanted partners with financial stability, a track record, and real technical depth.

AGC’s answer to that pressure was to lean into differentiation—especially through its Milan Center of Excellence. AGC Biologics positioned Milan as the hub for its cell and gene therapy division, with 30 years of experience, nine commercial approvals, and hundreds of successful GMP batches. It held commercial manufacturing authorizations from both the FDA and EMA for viral vectors and cell therapies. The company also highlighted recent momentum: over the prior 12 months, it cited two FDA commercial approvals (Lenmeldy™ and Aucatzyl®) and organic business growth of over 20% despite a declining market.

Financially, the segment showed the classic profile of an expansion-heavy business. Life Science net sales for the fiscal year reached ¥141.2 billion, up ¥14.4 billion, an 11.4% increase from the previous fiscal year. But operating profit moved the other direction: an operating loss of ¥21.2 billion, driven in part by upfront expenses tied to capacity expansion in the biopharmaceutical CDMO business.

So life sciences became AGC’s biggest near-term question mark. It demanded massive up-front investment, it was entering a period of industry-wide overcapacity, and it was not yet profitable. And yet the long-term demand case—more biologics, more advanced therapies, more outsourcing—remained powerful.

The open question wasn’t whether the market would exist. It was whether AGC could execute well enough, fast enough, in an industry where it didn’t have the kind of century-deep operational muscle memory it had built in glass and chemicals.

IX. The 2018 Rebrand: From "Asahi Glass" to "AGC Inc."

On July 1, 2018—after 110 years in business—Asahi Glass Company formally became AGC Inc. The name change wasn’t a facelift. It was a declaration: this company’s identity had outgrown the word “glass.”

The origin story still mattered. Founded in 1907, the company produced Japan’s first domestically made architectural flat glass two years later. And when World War I disrupted imports of key materials—raw inputs, furnace bricks—the company responded the way it always had: it brought critical production in-house. That instinct to control the hard parts of the supply chain didn’t just keep Asahi alive in its early decades; it set the pattern for how AGC would later approach semiconductors and biotech.

By the mid-2010s, management wanted the outside world to see what the company had already become inside. In 2016, AGC announced a long-term strategy called “What We Want to Be in 2025,” under former CEO Takuya Shimamura. The plan drew a bright line between “core businesses” and “strategic businesses.” Core meant the stable earnings engine—architectural glass, automotive glass, and chemicals. Strategic meant the next wave: mobility, electronics, and life sciences, where AGC would actively concentrate management resources.

The examples were telling. In mobility: chemically strengthened automotive glass for instrument panels. In electronics: EUV exposure mask blanks. In life sciences: a CDMO business that runs everything from process development to manufacturing. These weren’t small adjacencies. They were bets that AGC could take its real skill—materials science, process control, manufacturing discipline—and win in industries with far higher barriers than commodity glass.

That worldview is also reflected in who now runs the company. Yoshinori Hirai has been President, Director, and CEO since 2021. Before that, he served as Director, General Manager, Executive Officer, and Chief Technology Officer. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Engineering in 1987, became vice president of Optrex (a liquid crystal panel subsidiary) in 2008, and later led AGC’s business development office in 2011 before taking on the CTO role in 2016.

It’s not hard to see the throughline. Hirai is a scientist-CEO, much like founder Toshiya Iwasaki was a technically minded founder. Across a century, AGC kept returning to a similar leadership profile: people who understand the underlying physics and chemistry well enough to place long, expensive bets—and stick with them.

That pattern has earned AGC a reputation for what management thinkers call “ambidexterity”: the ability to keep the core business healthy while simultaneously building the next one. The idea—popularized by Stanford Graduate School of Business professor Charles A. O’Reilly—became attached to AGC strongly enough that the company was featured as a case study at Stanford. As Hirai put it, “Although we have not been consciously practicing organizational ambidexterity, it is true that we have continued the challenge of taking on new businesses since the company was founded.”

In 2021, the company formalized the approach under its long-term management strategy “Vision 2030.” The structure stayed consistent: core businesses as a long-term, stable base, and strategic businesses as the growth engine, with an explicit goal of reshaping the portfolio into what AGC viewed as the “optimal” mix. And in February 2024, AGC followed that with a new medium-term plan, AGC plus-2026, covering 2024 through 2026, as the successor to AGC plus-2023.

The message—especially to investors—was straightforward. AGC wasn’t asking to be valued like a glass company anymore. It was positioning itself as a materials science company that still happens to have major glass operations, alongside semiconductor materials, specialty chemicals, and biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

X. The Chemicals Flywheel: Fluoropolymers, FORBLUE & the Hydrogen Economy

If the 2018 rebrand was AGC saying “we’re not just glass,” the chemicals business is one of the clearest proofs. What began in the 1910s as a practical necessity—making soda ash and caustic soda because the supply chain wasn’t reliable enough—grew into a sophisticated fluoropolymers franchise. And in the 2020s, that franchise started to look less like a legacy division and more like a bridge to a new energy system.

You can see the fluoropolymer story in one of the most famous pieces of modern architecture in Europe: the Allianz Arena in Munich. Designed by Herzog & de Meuron and completed in May 2005, the stadium became the first in the world with a fully color-changeable exterior—an entire facade that can glow in the home team’s colors and transform the building into a living billboard.

That effect is made possible by AGC Chemicals Europe’s Fluon® ETFE FILM. The Allianz Arena is one of the world’s largest membrane-structure soccer stadiums, with about 66,500 square meters of ETFE film used across its surfaces. The material kept the structure lightweight and enabled advanced design elements like large curved surfaces. And because light can be controlled through the film—its transparency and diffusion—multicolored lighting from behind can wash the whole shell in red, blue, or white.

ETFE’s appeal isn’t just aesthetics. It has strong resistance to heat, chemicals, and weathering, helping the facade remain intact and functional even years later. It also allows through more than 90% solar transmission—enough natural light that grass can grow under the film—reducing the need for artificial lighting and improving the environment for spectators.

But as iconic as the stadium is, it’s not the endpoint. It’s a clue to what AGC can do when it applies deep chemistry and manufacturing know-how to demanding applications. And that brings us to the next act for the chemicals business: hydrogen.

As decarbonization accelerated and interest in a “hydrogen society” grew, demand increased for green hydrogen production plants powered by renewable energy. Scaling green hydrogen broadly still came with hard problems—stabilizing output amid fluctuating renewable supply and driving down costs—but AGC had a piece of the solution: fluoropolymer ion exchange membranes.

Its product line here is the FORBLUE™ S-SERIES, designed for polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) water electrolyzers. In PEM electrolysis, membranes aren’t a nice-to-have; they’re one of the core performance components. AGC positioned FORBLUE™ S-SERIES as enabling strong voltage performance and stable, long-term operation—exactly what large-scale green hydrogen production needs.

And AGC backed that bet with capacity. The company announced it would build a new production facility for FORBLUE™ S-SERIES at its Kitakyushu Site in Tobata-ku, Kitakyushu City. The plan called for an investment of approximately 15 billion yen, with the facility scheduled to begin operation in June 2026. After further expansion, AGC aimed to reach about 30 billion yen in FORBLUE™ S-SERIES sales in fiscal 2030.

As Yasushi Yamaki, senior manager of the FORBLUE Division at AGC Chemicals Company, put it: “The demand for PEM water electrolyzers could expand to dozens of times its current level after 2030.”

What makes this feel like a true AGC “flywheel” is where the capability came from. These membranes and dispersions draw on deep expertise in polymer design, membrane technology, and membrane film production—skills honed over more than 50 years in the chlor-alkali business. In other words, a technology AGC developed in the 1970s to replace mercury-based caustic soda production evolved into a platform that could matter in the 2030s energy transition.

This is the compounding advantage of industrial R&D done right. The knowledge embedded in materials, processes, and quality systems doesn’t show up overnight—and it can’t be copied quickly, either. AGC’s chemicals business is what it looks like when a century-old manufacturing company turns its past constraints into future options.

XI. Playbook: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

At this point in the story, AGC isn’t one business. It’s a portfolio of very different businesses living under one roof—and they behave very differently under pressure. The easiest way to see that is to run them through two lenses: Porter’s Five Forces for industry structure, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers for durable competitive advantage.

EUV Mask Blanks: A Near-Monopoly

Start with the crown jewel. EUV mask blanks are, structurally, the best business AGC has ever built.

Porter makes the picture pretty stark:

-

Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW. The bar is extreme: manufacturing defect-free blanks demands sophisticated deposition, inspection, and metrology equipment, plus years of process learning. The catch is that the same concentration that protects profits also creates fragility—there just aren’t many suppliers if anything goes wrong.

-

Buyer Power: LOW. Chipmakers need EUV capability for leading-edge production, and EUV needs reliable mask blanks. In this category, quality comes first. Price comes later.

-

Supplier Power: MEDIUM. Inputs and equipment matter, but AGC’s end-to-end approach—glass material synthesis through coating—blunts dependence on any single upstream supplier.

-

Threat of Substitutes: VERY LOW. For sub-7nm class manufacturing, there isn’t a clean alternative to EUV lithography, which means there isn’t a substitute for EUV mask blanks as an enabling component.

-

Competitive Rivalry: LOW-MEDIUM. The market is tiny and concentrated. AGC holds about 59% share, with Hoya around 34%—together accounting for the vast majority of global supply.

Helmer’s Seven Powers explains why this position is so valuable—and so hard to dislodge:

-

Switching Costs: VERY HIGH. Each new chip generation drives customization, qualification, and risk. Customers don’t casually swap suppliers when a mistake can disrupt production.

-

Scale Economies: SIGNIFICANT. The capex and know-how required to get to reliable yield create an advantage that compounds with volume.

-

Counter-Positioning: PRESENT. Traditional flat-glass competitors can’t simply “decide” to enter. The capabilities, tooling, and customer qualification cycles are from a different universe.

Flat Glass: A Commodity Trap

Now flip to architectural and automotive glass—the businesses AGC was born in.

-

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM. Building float capacity is expensive, but the technology is mature and regional players can still show up.

-

Buyer Power: HIGH. Construction buyers and automotive OEMs are intensely price sensitive, and switching costs are limited.

-

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. Saint-Gobain, Guardian, Nippon Sheet Glass, and AGC fight in a market where keeping furnaces full often matters more than winning on differentiation.

This is why the 2007 scandal was such a revealing moment. When an industry is structurally trapped, the temptation becomes “stabilizing” the market—because straightforward competition tends to destroy value.

CDMO Business: Promising but Unproven

Life sciences sits in the middle—attractive long-term, messy short-term.

-

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM. Facilities are expensive and technical execution is hard, but capital is available and talent can be recruited.

-

Buyer Power: MEDIUM. Customers need reliability and compliance, yet they typically have multiple CDMOs to choose from—especially in periods of overcapacity.

-

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM-HIGH. It’s a fragmented market with a constant fight for contracts, and cyclical swings in biotech funding can quickly change the balance of power.

Key Competitive Advantage: Cornered Resource

Across these businesses, AGC’s most important advantage is less about any one product and more about a repeatable capability: identifying fields with long runways and then investing patiently for 10 to 20 years in the materials science required to win.

That long-horizon R&D discipline—kept alive through economic cycles and leadership transitions—functions like a cornered resource. Many competitors can spend money. Far fewer can sustain technical programs long enough to reach a position of overwhelming advantage.

Financial Performance and Valuation

AGC’s market capitalization is about $6.62 billion, with a dividend yield of 4.05%. In yen terms, that’s roughly ¥1.11 trillion.

The company reported a loss attributable to owners of the parent of ¥94 billion, down ¥159.8 billion, driven by other expenses including Life Science-related impairment losses and losses tied to the transfer of the Russian business in the first half.

For 2025, AGC guided to net sales of ¥2,150 billion and operating profit of ¥150 billion.

KPIs to Monitor

If you want a simple scoreboard for whether the transformation is working, watch three things:

-

EUV mask blank sales growth — This is the most defensible, highest-quality business in the portfolio. Sustained growth here validates the semiconductor bet.

-

Life Sciences segment operating margin — It’s been negative amid build-out and market turbulence. A credible path to profitability is the clearest signal that AGC can execute in CDMO at scale.

-

Strategic business revenue as a share of total — Management is explicitly trying to rebalance toward higher-margin, higher-barrier businesses. This ratio tells you whether that shift is actually happening.

XII. What Lies Ahead: Investment Considerations

By the end of 2025, AGC is a complicated investment story for a simple reason: it’s an 118-year-old company trying to finish a multi-decade escape from commodity glass and into businesses where materials science creates real leverage.

The bull case is easiest to tell through three bets.

First: EUV mask blanks. AGC sits in a rare position—supplying one of the most qualification-heavy, failure-intolerant inputs in advanced chipmaking, right as AI demand is pulling the semiconductor industry forward. Management’s view is straightforward: the semiconductor-related market should keep expanding, driven by AI, and AGC intends to grow by pushing further into the high-end segment.

Second: hydrogen. AGC’s investments in fluoropolymer ion exchange membranes are a call option on the buildout of green hydrogen infrastructure. If PEM electrolyzers scale the way hydrogen advocates expect, membranes become a critical bottleneck component—and AGC wants to be ready with industrial capacity.

Third: culture. AGC has a proven willingness to fund long R&D arcs and stick with them. That patience—combined with deep process control know-how—lets it pursue opportunities that many quarter-to-quarter competitors struggle to justify.

The bear case also has three pillars, and they’re just as real.

First: the legacy base still matters. Flat glass and automotive glass remain fundamentally competitive, price-driven businesses. They throw off volume, but the economics can be unforgiving.

Second: life sciences is still in the “show me” phase. AGC has built a real footprint, but profitability has been elusive, and the CDMO market—especially in cell and gene therapy—has been dealing with overcapacity and uneven customer demand.

Third: complexity. The portfolio is strategically coherent—materials science everywhere—but the structure can still read like a conglomerate. That can make it harder for investors to see, value, and underwrite the strongest businesses on their own merits.

One recent event looms over the numbers: the exit from the Russian business. AGC reported a loss attributable to owners of the parent of ¥94 billion, driven primarily by Life Science-related impairment losses and losses tied to the transfer of the Russian business.

There’s also a regulatory variable worth keeping on the radar: PFAS regulation. As a major fluoropolymer producer, AGC faces risk if restrictions broaden to cover industrial applications of fluorinated materials. AGC’s role in semiconductors and hydrogen-related systems may help, but investors will want to track how regulators draw the lines—and how quickly.

Stepping back, the transformation from Asahi Glass to AGC Inc. is still in progress. The company is living between two identities: a century-old glass manufacturer, and an emerging materials science platform. The outcome depends on execution in the strategic businesses. Can EUV mask blanks keep scaling with demand? Can life sciences move from expansion to sustained profitability? Can hydrogen-related products win meaningful share as the market develops?

What’s not in dispute is the staying power. Very few companies operate continuously for 118 years. Fewer still reinvent themselves across multiple technological eras—from Meiji-era flat glass, to television tubes, to automotive safety glass, to smartphone cover glass, to EUV-era semiconductor materials, to biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

In his later years, Toshiya Iwasaki devoted more and more time to Zen Buddhist meditation. A sign—“Now meditating”—often hung outside the door to his personal quarters. It’s tempting to see that same temperament echoed in the company he started. In a world obsessed with quick payoffs, AGC still runs on long cycles: fifteen-year development programs and decade-long portfolio shifts. The investor’s question is whether that patience ultimately compounds shareholder value—or whether it simply preserves a legacy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music