Idemitsu Kosan: The Pirate, The Blockade, and Japan's Oil Maverick

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: March 1953. A Japanese oil tanker, the Nissho Maru, slips toward the Iranian port of Abadan while British warships enforce a blockade meant to strangle Iran’s oil exports. Its owner, a stubborn petroleum distributor named Sazō Idemitsu, is betting his company on a move most of corporate Japan thinks is reckless: buying Iranian oil that London insists is stolen property. Two months later, when the ship reaches Kawasaki carrying roughly 22,000 kiloliters of gasoline and diesel, crowds pack the harbor to greet it like a returning champion. The British sue. Japan’s courts refuse to seize the cargo. And one voyage turns a scrappy distributor into a national symbol of postwar resilience.

That’s the legend at the heart of Idemitsu Kosan. Today, it’s Japan’s second-largest petroleum refiner after Eneos—an enormous, modern energy company with refineries across the country. But it’s also something less expected: a materials business, supplying high-performance components for displays and battery technologies. And in one of the great ironies of the energy transition, this oil company has positioned itself as an important partner in Toyota’s push toward all-solid-state batteries.

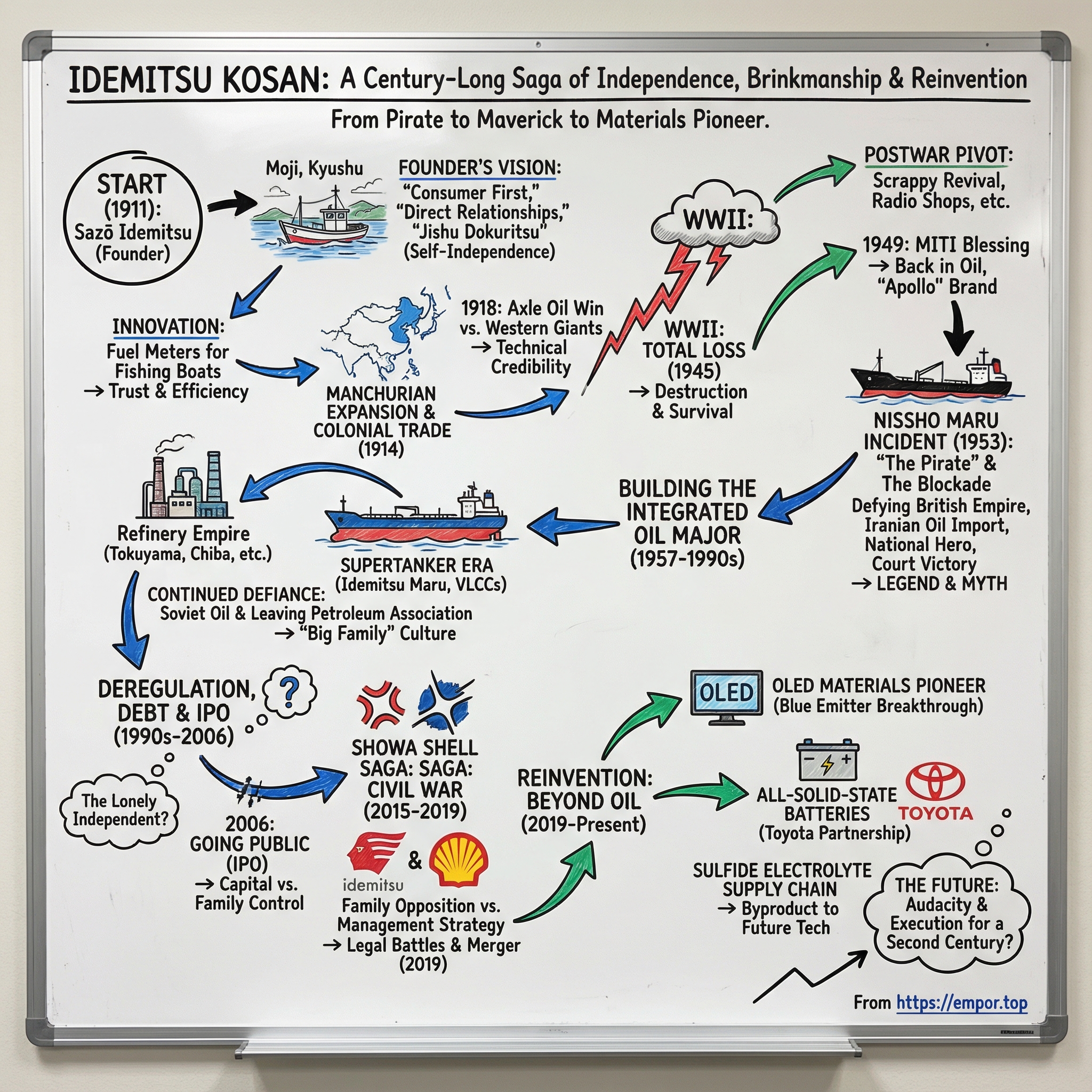

So here’s the question that makes Idemitsu such a great story: how did a company founded in 1911 to sell lubricating oil—starting with humble customers like fishing boats—grow into an industrial pillar, survive total wartime loss, repeatedly pick fights with global powers, endure a very public internal battle between the founding family and professional management, and still find a path to reinvent itself as the world moves beyond oil?

The answer is bigger than one company. It’s about Japan’s deep fixation on energy security. It’s about what founder-led defiance looks like when it hardens into corporate culture. And it’s about the strange way a moral vision—how a company believes business should be done—can become both a competitive advantage and, later, a source of crisis.

Because Idemitsu wasn’t built as a typical maximize-the-spreadsheet enterprise. Sazō Idemitsu founded Idemitsu Shokai in Kitakyushu in 1911 and grew it into what became Idemitsu Kosan. Over more than a century, the company cultivated a philosophy that treated the firm less like a machine for returns and more like an extension of the founder’s beliefs about commerce, human dignity, and Japan’s place in the world. That worldview created unusual resilience. It also planted the seeds for governance conflict that would erupt into the open decades later—by the time the company was public, the Idemitsu family still held roughly 30% and remained influential.

This is the roadmap: we’ll start with Sazō Idemitsu’s early years and the operating innovations that made him dangerous to incumbents. Then we’ll follow the company through collapse and revival after World War II, into the Nissho Maru incident—the moment Idemitsu became myth. From there, we’ll track how it built a vertically integrated oil empire, how deregulation and consolidation tested its independence, and how a modern corporate civil war reshaped the company. Finally, we’ll land in the present, where Idemitsu is trying to turn the byproducts of oil refining into the raw materials of the post-oil economy.

II. Sazō Idemitsu: The Founder's Vision (1911-1940)

The Birth of a Challenger

Sazō Idemitsu was born on August 22, 1885, in Akama village in Fukuoka Prefecture, the second son of an indigo wholesaler. He grew up in Kyushu at a time when Japan was still in the aftershock and adrenaline of the Meiji Restoration—an era obsessed with catching up to the West, industrializing fast, and proving the country belonged among modern powers. Sazō absorbed that national ambition early. But he paired it with something more personal: a stubborn belief in self-reliance.

At first, he wanted to become a diplomat. But his father’s teaching—jishu dokuritsu, “self-independence”—pulled him toward business instead. He enrolled in commercial school in Fukuoka, then continued to Kobe Higher Commercial School (now Kobe University). It was a practical choice, but not a small one. The version of Sazō who would later stare down superpowers didn’t lose the diplomat’s instincts; he simply learned to apply them through commerce.

In Kobe, he studied under a professor named Renkichi Uchiike, and one lecture in particular became the backbone of Idemitsu’s future. Uchiike argued that commerce wasn’t just about taking a cut. In a modern economy, speculative middlemen would fade away. The winners would be the distributors who connected producers to consumers and actually fulfilled a social responsibility.

Sazō took that personally. He later turned it into a guiding idea: put the consumer first. Build direct relationships. Cut out unnecessary intermediaries. The slogans came later—“from producer to consumer,” “large-area retailing,” “consumer-orientation”—but the strategic insight was already there. If you make your customers’ lives meaningfully better, you become hard to dislodge.

Most of his classmates aimed for the safe route: big companies, major banks, elite bureaucratic tracks. Sazō did the opposite. He chose a small Kobe trading firm, Sakai Shoten, that dealt in wheat flour and machine oil. His reasoning was simple: at a large company you only see your slice of the machine; at a small one, you learn the whole job because you have to do everything.

He graduated in 1909, worked in Kobe, and then in 1911—back in Moji, a port city in northern Kyushu—he opened his own oil business: Idemitsu Shōkai, with the backing of a wealthy investor named Jutarō Hida. It began with lubricants, sold as an agent for Nippon Oil. But from the start, it was aimed at something bigger than being a local reseller.

Innovation Through Customer Intimacy

Moji was a smart place to begin. It sat near the Kanmon Straits, a narrow passage packed with ship traffic. And nearby, in places like Shimonoseki, fishing boats were everywhere—hundreds of small operators whose livelihoods depended on fuel.

Sazō didn’t treat them like anonymous demand. He got close to the work. He studied combustion efficiency and noticed a painful mismatch: fishing families were burning expensive paraffin oil, basically kerosene, when cheaper raw light oil could do the job. That price difference wasn’t an academic detail. It was the difference between a good month and a desperate one.

Then in 1923, he did something that sounds obvious today but was radical then: he changed how fuel was delivered. Instead of selling canned fuel, he introduced small tanker vessels equipped with fuel meters, so boats could buy measured quantities efficiently and reliably.

The result wasn’t just a better retail system. It was a better life for customers. Fuel costs fell, trust rose, and word traveled fast along the coast. Before long, Idemitsu Shōkai was supplying diesel oil to roughly 70% of the fishing boats along the Kanmon shoreline.

It also taught Sazō a harsher lesson: in oil, power tends to sit upstream. As a distributor for Nippon Oil, he was exposed to a constant vulnerability. Wholesale prices could change at someone else’s whim, squeezing him whenever it suited them. If he wanted independence, he couldn’t stay a pure middleman forever.

Manchurian Expansion and the Colonial Oil Trade

In 1914, Idemitsu expanded beyond Japan into Manchuria, where the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railway was a major lubricant customer. A branch opened in Dalian, and Sazō tried to break into a market dominated by Western giants—Standard Oil and the Asiatic Petroleum Company (a Shell subsidiary), among others. Over time, the company extended through northern China and into Korea and Taiwan.

Manchuria was where Sazō’s ambition became impossible to miss. This wasn’t just expansion for growth’s sake; it was expansion into hostile territory. Japanese petroleum products faced disadvantages in transportation costs, tariffs, and perceived quality. Many Japanese firms hesitated. Sazō pushed in anyway.

The South Manchuria Railway soon handed him both a crisis and an opening. In early 1918, axles on several hundred freight cars overheated and failed, causing a massive loss—three to four million yen. The railway brought Idemitsu into the investigation and field testing in Changchun, in brutal cold. Four axle oils were tested: products from Vacuum, Standard Oil, Idemitsu’s existing winter oil, and a new sample Idemitsu submitted called “No. 2 winter weatherproof axle oil.”

Only Idemitsu’s No. 2 performed flawlessly. Vacuum’s did the worst.

That win mattered far beyond one contract. It proved Idemitsu could compete on technical performance, not just on distribution hustle. Sazō wasn’t merely moving barrels around; he understood petroleum well enough to tailor products for extreme conditions and beat global incumbents at their own game.

But the political winds shifted. After Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1932, the oil trade became government-controlled, and Idemitsu was forced to scale back. Sazō took the message: you don’t just risk dependency on suppliers. You risk dependency on regimes, regulations, and geopolitics. If the company was going to survive long-term, it needed sturdier foundations.

Vertical Integration Begins

With his sales activities constrained, Sazō started building the next version of Idemitsu—one that could control more of its destiny. He moved beyond pure sales into transportation, launching his first oil tanker, the Nisshō Maru, in 1938. He also stepped into refining through investment in Kyushu Oil Refinery Co. Ltd., and diversified into other products.

The first Nisshō Maru—built in 1938—was the turning point. Owning transportation meant Idemitsu could move oil on its own terms. It reduced vulnerability to squeeze-plays and made the company capable of operating across longer distances and more complicated supply chains. This was the early shape of vertical integration: not just selling petroleum, but controlling the system around it.

In 1940, Idemitsu moved its domestic headquarters from Moji to Tokyo and reorganized as a joint stock company: Idemitsu Kōsan K.K., capitalized at four million yen. The company’s China and Manchuria operations were reorganized into separate regional subsidiaries.

It was a maturation moment—a regional challenger becoming a national enterprise. But the timing carried a shadow. Japan was accelerating toward total war, and soon the state would tighten control over industry. Then, much of what had been built would be wiped out.

That same year, as the company grew to more than a thousand employees, Sazō circulated a treatise to the entire workforce: five business philosophies meant to define what Idemitsu was and what it would never become. The principles emphasized respect for fellow human beings, creating value for society, and maintaining a family-like environment inside the company.

This became Idemitsu’s cultural core. Employees weren’t treated as interchangeable labor; they were treated as members of a household with an expectation of long-term commitment. It created extraordinary loyalty and cohesion. It also baked in a kind of rigidity—one that would become harder to manage as the world changed.

III. Destruction and Resurrection: The Postwar Pivot (1945-1952)

Total Loss

By August 1945, Japan was shattered—and Idemitsu Kosan was, effectively, wiped off the map.

The company lost its overseas business in one sweep: Manchuria, Korea, Taiwan. It lost ships. It lost capital. And with petroleum still tightly controlled in the immediate aftermath of the war, Idemitsu wasn’t really an oil company anymore. It was reduced to handling bits and pieces of distribution work through a handful of branches—places like Wakamatsu, Beppu, and Nagoya—while a wave of repatriated staff came home to a company with almost nothing for them to do.

So Sazō did what Sazō always did: he refused to let the organization die.

Idemitsu threw itself into whatever work might keep people employed—recovering oil from the bottoms of former Imperial Navy tanks, repairing and selling radios, printing, farming, making soy sauce and vinegar, even trying its hand in the marine products business. Most of it failed. But that’s not really the point. The point is that Idemitsu’s “big family” philosophy wasn’t a poster on the wall. It was a promise Sazō tried to keep when keeping it was inconvenient and expensive.

One of those detours, though, quietly mattered. The radio repair and sales business expanded into roughly 50 shops in major cities across Japan. It didn’t become a lasting profit engine, but it did something else: it put Idemitsu storefronts in urban Japan and taught Idemitsu people how to run retail. When oil finally came back, that muscle memory—and those locations—could be repurposed.

The MITI Blessing and American Obstacles

The lifeline arrived in 1949. With Idemitsu’s overseas trade gone under the Allied occupation, the company managed to secure the right to distribute petroleum products again. And when the Oil Distribution Public Corporation was abolished, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) selected ten companies to serve as suppliers—names like Standard Oil, Shell, and Caltex.

Idemitsu made the list.

That designation was more than a permit. It was a return to legitimacy, and it gave Idemitsu a path back into international supply. It also triggered a clean break with Nippon Oil, ending the old dependency that had always left Sazō vulnerable to someone else’s pricing power.

By 1952, Idemitsu was importing high-octane gasoline from the United States and selling it in Japan under a new brand name: Apollo. It was a signal to the market that Idemitsu wasn’t content to be a behind-the-scenes distributor anymore. It wanted a consumer identity—its own flag on its own stations.

But the moment Idemitsu started acting like an independent, the squeeze began.

The big U.S. oil companies realized there was more money in supplying Japan directly than in selling to a hungry Japanese upstart who might someday compete with them. So supplies tightened. Idemitsu’s purchases in California were restricted. The company switched to Houston, Texas—then found the door closing there too. Eventually, it managed to source from Venezuela, but the message was unmistakable: to the Western majors, Idemitsu wasn’t a partner. It was an interloper.

And that pressure crystallized the next strategic obsession. If Japan’s economy was going to rebuild, it needed energy. If Idemitsu was going to survive, it needed supply. And neither Japan nor Idemitsu could afford to have that supply controlled by someone else.

The question was where to find oil outside Western control—and who would have the nerve to go get it.

IV. The Nissho Maru Incident: Defying the British Empire (1953)

Setting the Stage: Iran's Nationalization Crisis

To understand what happened next, you have to zoom out to the early 1950s, when oil wasn’t just an input to industry. It was geopolitics, sovereignty, and empire.

In 1951, Iran’s Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, the British enterprise that had effectively controlled Iranian petroleum for decades. Britain treated it as a seizure of British property and hit back with economic sanctions and a blockade designed to make Iranian oil unsellable.

And Britain didn’t just threaten. In July 1952, the Royal Navy intercepted the Italian tanker Rose Mary and forced it into the British protectorate of Aden, arguing the cargo was stolen property. The signal was unmistakable: carry Iranian oil and you might get boarded.

That one interception did what blockades are supposed to do. It scared off the rest of the market. Tanker owners didn’t want a fight with the Royal Navy, insurers didn’t want the risk, and buyers didn’t want the legal trouble. Iranian exports effectively froze.

The United States, under President Harry Truman, backed Britain’s hard line. So for any company thinking about buying Iranian crude, the obstacle wasn’t just British naval power. It was the possibility of retaliation from the broader Western oil establishment.

Iran, meanwhile, was running out of options. Oil revenue was the lifeblood of the economy, and the blockade was strangling it. Mosaddeq needed a buyer willing to defy London. Western majors couldn’t be that buyer. Someone else had to.

Idemitsu's Gamble

That “someone else” turned out to be Sazō Idemitsu—still, in global terms, just a Japanese petroleum distributor from a country that had only recently regained sovereignty. Japan’s occupation had ended in April 1952, but the country was economically fragile and still deeply sensitive to American goodwill. Picking a fight around sanctions and blockades risked British legal action and American displeasure.

But Idemitsu saw what the majors and Japan’s establishment didn’t want to see: a perfect, if dangerous, alignment.

Japan needed affordable oil to power its recovery. Iran needed a customer brave enough to buy. If Idemitsu could make the trade happen, he wouldn’t just secure supply—he’d secure an edge.

Iran eventually agreed to sell at a 30% discount to market price. For Iran, it was the price of desperation. For Idemitsu, it was an extraordinary advantage: cheaper barrels meant he could compete harder at home and build the company faster.

He also needed a ship he could control. In 1951, Idemitsu Kosan received permission from MITI to build a new tanker. It was named Nissho Maru, after an earlier vessel. Built in 1951, this second-generation Nissho Maru—about 18,000 DWT—would soon become famous worldwide for what it did next.

The Voyage

Nissho Maru departed on March 23, 1953 and made it to Abadan without being detected by the Royal Navy. When she arrived, the reception in Iran wasn’t polite—it was celebratory. People filled the streets. The crew was greeted with flowers, sweets, and music.

For Iranians, the ship’s arrival was proof the blockade wasn’t absolute. Someone had finally called Britain’s bluff.

For Idemitsu, it was only halftime. The ship still had to load, sail back across contested waters, and do it without getting intercepted.

Fully loaded, Nissho Maru left Abadan on April 15 under worldwide attention. The return voyage became a careful blend of detours, radio silence, and nerve. On April 26, she took a major detour and went through the Sunda Strait to avoid British destroyers. That same night, she used darkness to slip through the dangerous reefs of the Java Sea. Over the following days she passed through the Gaspar Strait, then reached the South China Sea and ended radio silence to contact Idemitsu.

On May 9, at 9am, Nissho Maru arrived at Kawasaki Port.

International Sensation

By then, the story had already escaped the shipping lanes. Media around the world covered it as an international incident. In Japan, it landed like a thunderclap: an unarmed private company picking a fight with the Royal Navy—the symbol of the British Empire and, at the time, the world’s second-largest naval force.

The framing mattered. This wasn’t presented as a clever sourcing decision. It was David versus Goliath. And it hit Japan at a moment when the country was still shaking off the humiliation and hardship of defeat and occupation. One tanker coming home safely could feel like something bigger than business: a small, clean victory in a world that still felt dominated by others.

Carrying roughly 22,000 kiloliters of gasoline and diesel, Nissho Maru was greeted by welcoming crowds at Kawasaki. And almost immediately, Britain struck back in court. Anglo-Iranian Oil Company sued Idemitsu in the Tokyo District Court, claiming ownership of the cargo.

Victory in Court and Cultural Legacy

Anglo-Iranian asked the courts for a provisional injunction to seize the oil. The Tokyo District Court refused. The Tokyo High Court refused as well. After years of litigation, the British effort failed.

In the near term, the key moment came quickly: the motion for provisional seizure was dismissed on May 27. Anglo-Iranian appealed the same day, but later withdrew the appeal on October 29. Idemitsu had won.

This wasn’t just law; it was politics. The United States did not love the idea of Britain’s oil monopoly, and American oil majors were hardly heartbroken to see Anglo-Iranian challenged. That tacit tolerance mattered. It helped create the political room for Japanese authorities to avoid administrative sanctions even as Britain demanded consequences.

Back home, the Nissho Maru’s arrival became a morale-boosting episode for a country still emerging from the postwar shadow. In the public imagination, it was a “miracle”—a head-on confrontation with a core Allied power, and a rare moment of triumph that made Japan feel, again, like it had agency in the world.

For Sazō Idemitsu personally, it was transformative. The Nissho Maru incident turned him into one of the most popular business leaders in postwar Japan. And in the national narrative, the episode became linked to the broader economic momentum that would soon accelerate into the rapid growth of the mid-1950s.

The Price of Defiance

But victories like this come with a bill.

Yes, Idemitsu bought oil at a steep discount. And yes, the public loved that he had stood up to Britain. But the move also put Idemitsu on a collision course with Japan’s own government and MITI. Acting unilaterally on something with major diplomatic consequences was the opposite of how consensus-oriented postwar Japan preferred its corporations to behave.

Iranian imports eventually ended in 1956, after the major international oil firms reasserted their unity and influence in Iran. Even so, the incident left a lasting mark. It foreshadowed Japan’s later push for direct relationships with oil-producing states and helped fix the Middle East in the Japanese public’s mind as central to the country’s energy future.

And inside Idemitsu, it hardened something that had been growing for decades: a defensive instinct. To protect the company from future pressure—foreign or domestic—Sazō tightened its closed ownership structure even further. Idemitsu would remain closely held by the family and employees, insulated from outsiders who might force it to compromise its independence.

That posture would endure for decades, long past Sazō himself—until the realities of debt and modern capital markets eventually made the walls impossible to keep closed.

V. Building the Integrated Oil Major (1957-1990s)

Refinery Empire

The Nissho Maru incident proved Idemitsu could outmaneuver blockades and superpowers. But it also underlined a harder truth: if you’re only importing and distributing, you’re still at the mercy of whoever controls refining and supply. Idemitsu had won a dramatic battle for barrels. Now it needed an industrial base that made those barrels truly usable, and profitable, inside Japan.

So the company started building.

Idemitsu’s first major step was the Tokuyama Refinery, which opened in 1957. Then came the Chiba refinery in 1963, Hyogo in 1970, Hokkaido in 1973, and Aichi in 1975. In other words: within less than two decades, Idemitsu went from a daring trader-and-distributor into a company with refineries spread across the country.

This buildout wasn’t done in a vacuum. Idemitsu developed with financial backing from the Bank of Tokyo and Tokai Bank, and it paired refining with the other pillar of independence: owning the ships that brought crude in the first place. During this period, Idemitsu’s position in Japan’s oil market rose rapidly, and its refining footprint grew from essentially nothing in the mid-1950s into a meaningful share by 1960.

The point wasn’t just scale. It was leverage. Vertical integration meant Idemitsu could secure crude, move it on its own hulls, refine it in its own facilities, and sell finished products under its own brand. If one part of the chain got squeezed, the company had other places to earn margin—and more control over its destiny.

Tanker Innovation: Pioneering the Supertanker Era

The mid-1950s also brought a second lesson: geography can rewrite economics overnight.

The Suez Canal crisis in 1956 threw global shipping into chaos. When routes through Suez became unreliable, tankers increasingly had to go the long way around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope. That extra distance punished smaller ships. The new math rewarded size: bigger tankers could spread the cost of the voyage over far more cargo.

Idemitsu leaned into that shift early. Starting with the Universe Admiral in 1956, the company moved toward ever-larger vessels. In July 1962, it completed the third-generation Nissho Maru—at the time the world’s largest tanker, with capacity around 139,000 tons—and established Idemitsu Tanker Co., Ltd. to manage its growing transportation arm.

Then, in December 1966, Idemitsu commissioned the Idemitsu Maru, the world’s first 200,000-ton-class VLCC. From 1962 to 1981, Idemitsu completed ten mammoth tankers over the 200,000-ton mark and built a worldwide petroleum transportation network.

This wasn’t just about being flashy on the seas. It was the same logic Sazō had applied since Moji: cut dependence, lower unit costs, and make it harder for anyone—supplier, competitor, or government—to box you in. And as a side effect, Idemitsu’s demand for giant ships helped pull Japan’s shipbuilding industry forward too.

Continued Defiance: Soviet Oil and Leaving the Petroleum Association

By the 1960s, “defiance” wasn’t a one-off chapter in Idemitsu’s history. It was becoming a habit.

When an opportunity emerged to buy crude from the Soviet Union at a steep discount, Idemitsu took it. The discount was huge, and the diplomatic consequences were predictable. The United States was angry enough that it boycotted Idemitsu when purchasing fuel for U.S. military jets in Japan.

Sazō Idemitsu’s response was pure Sazō. He dismissed the boycott as “an odd Christmas gift,” and “utterly negligible.” The quip worked because it reflected his calculation: losing a sliver of business was worth it if the cheaper crude strengthened Idemitsu’s overall competitiveness.

Around the same time, Idemitsu collided with the Petroleum Association of Japan, which had been set up by MITI to restrict production. Rather than play along, Idemitsu left the association entirely.

In Japan’s corporate world, that was a loud statement. Trade groups are where companies signal they belong. Walking out signaled the opposite: Idemitsu would rather stand alone than accept coordination that, in its view, didn’t serve consumers.

The Unique Corporate Culture

The company’s willingness to fight—sometimes with foreign oil majors, sometimes with the Japanese establishment—was tied to something deeper than strategy. It was cultural.

Sazō championed what he called “large regional retail business,” built on the belief that oil should move smoothly from producer to consumer without unnecessary toll collectors in the middle. Inside the company, he paired that idea with the “big family principle”: once someone joined Idemitsu, they were treated not as disposable labor, but as a permanent member of the household. Decisions were meant to be made with the feeling that everyone involved was “both parents and children, older brothers and younger brothers.”

Structurally, the company reinforced that mindset. Idemitsu was organized as a joint stock company with shares held by the Idemitsu family and employees—another layer of insulation from outside influence, and another way to bind the workforce to the company’s fate.

The results were powerful. Employees believed Idemitsu wouldn’t cut them loose in a downturn, because “family” doesn’t do layoffs. In return, they gave the company a level of loyalty and cohesion that helped it push through crises that would have broken a less unified organization.

Sazō became chairman in 1966, retired from that role in 1972, and died in 1981. Leadership had already passed to the next generation: his son, Shosuke Idemitsu, became CEO in 1950 and later served as chairman of the board from 1998 to 2001.

That succession preserved Idemitsu’s philosophy. But it also preserved something else: a durable pattern of family control. And as the industry modernized, deregulated, and consolidated, that pattern would eventually run into the realities of professional management and capital markets.

VI. The Lonely Independent: Deregulation and Industry Consolidation (1990s-2006)

The Changing Landscape

The 1990s didn’t just change Japan’s petroleum industry. They dismantled the rules it had been built on.

Deregulation came in waves. The Special Petroleum Law was abolished. Self-service pumps became legal. And as Japan slid through a long economic slump, demand softened just as the market got more brutally competitive. The industry suddenly looked oversized for the country it served, and consolidation became the default move. One by one, companies paired up to survive.

Idemitsu didn’t.

By the turn of the century, it stood out as the only major refiner that hadn’t merged. And structurally, it still looked like an earlier era: the company was held by the Idemitsu family and employees, insulated from outside shareholders in a way that felt almost anachronistic in a consolidating, capital-intensive business.

There’s an irony here. The deregulation Idemitsu had long argued for—remember Sazō’s willingness to break with the Petroleum Association rather than accept production controls—was now the force squeezing independents the hardest. With protections gone, competition intensified, margins tightened, and scale mattered more than ever.

And Idemitsu had another problem: it had scaled, but it had paid for that scale the expensive way.

By 1997, Idemitsu was Japan’s largest seller of fuel oil, a position built in large part on major capital investments under president Shosuke Idemitsu in the 1980s and early 1990s. The catch was the balance sheet. Those investments left the company deeply in debt, with a speculative credit rating.

So the company did something that, culturally, mattered almost as much as any refinery it had ever built: it brought in a leader from outside the founding family. Akihiko Tembo became the first non-family president, with a mandate to stabilize the finances and professionalize operations—exactly the kind of change that tends to sound reasonable right up until it collides with a founder’s worldview.

The Debt Problem and IPO Decision

For decades, Idemitsu’s closed ownership structure had been a shield. It kept the company independent, protected its “big family” philosophy, and made it harder for outsiders—governments, competitors, or shareholders—to force a change in direction.

But that same structure also boxed the company in. Without public equity, there were only two ways to fund big moves: keep profits and reinvest them, or borrow. By the 2000s, retained earnings couldn’t carry the load, and debt had already been stretched.

At some point, the math stops being a debate about philosophy. It becomes a question of survival.

Relief was always going to require access to capital markets. Company leadership said so plainly at the time: if Idemitsu wanted stable management, it needed the ability to raise money directly rather than rely entirely on bank borrowing.

That logic led to the one step Sazō had designed the company to avoid. An IPO meant outside shareholders. Outside shareholders meant shared control. And shared control meant the founder’s century-old model of independence would no longer be absolute.

Going Public: The 2006 IPO

In 2006, Idemitsu Kosan went public on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The IPO took place on October 24, 2006 and raised 109.4 billion yen—capital management could use to repair the balance sheet and regain financial flexibility.

But it also rewired Idemitsu’s governance.

Before the offering, family and employees had owned the company outright. After it, external shareholders had a real seat at the table. The founding family still held roughly twenty-eight percent—enough to be a blocking minority on major decisions requiring a supermajority, but not enough to control day-to-day strategy.

That split—professional managers running a now-public company, and a founding family still powerful enough to say “no”—would become unstable the moment management pursued a move the family couldn’t accept.

Idemitsu Kosan is listed in the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange and, after absorbing Showa Shell Sekiyu in 2019, became a constituent of the Nikkei 225 index.

VII. The Showa Shell Saga: Family vs. Management Civil War (2015-2019)

The Strategic Rationale for Merger

By the mid-2010s, the Japanese oil business was running into a reality it couldn’t outmuscle: the home market was shrinking. Fuel and lubricant demand was slipping, self-help cost cuts weren’t enough, and every major refiner was staring at the same question—who’s going to blink first, and merge?

That’s the backdrop for why Idemitsu Kosan and Showa Shell started merger talks in 2015. As Idemitsu President and Representative Director Shunichi Kito put it, “The managerial environment of the Japanese petroleum industry has been getting tougher,” thanks to declining demand over the medium to long term and worsening climate change.

The industrial logic was straightforward. Japan ran one of the largest and most sophisticated refining systems in Asia-Pacific, but domestic energy use was trending down. Capacity was coming out of the system too: between 2023 and 2024, two refineries with a combined CDU capacity of 240,000 barrels per day were permanently closed—about 7% of national capacity. The long-term pressures were obvious: an aging and shrinking population, slower growth, and fiercer competition from petroleum exports elsewhere in Asia. The U.S. EIA forecast Japan’s petroleum product consumption would fall to around 3.3 million bpd in 2024, the lowest level since at least 1980.

In that world, combining Idemitsu and Showa Shell wasn’t about empire-building. It was about survival—rationalizing excess capacity, protecting scale, and buying enough breathing room to invest in new businesses beyond traditional refining.

Family Opposition: The Culture Clash

Except this wasn’t just a merger model and a synergy deck. For Idemitsu, it was identity.

The founding Idemitsu family opposed the deal for a mix of reasons: longstanding friction with Tembo-era professional management, worries that the two companies’ cultures wouldn’t mix, geopolitical concerns (Idemitsu had long been a major importer of Iranian oil while Showa Shell would remain partly owned by Saudi Aramco), and pressure in an industry where rival JX Nippon Oil & Energy was pursuing its own merger with TonenGeneral.

But the emotional core of the opposition was simpler. Idemitsu’s culture had been forged in resistance to foreign control and devotion to the founder’s philosophy. Showa Shell, by contrast, traced its lineage to Royal Dutch Shell—the kind of Western oil major Sazō Idemitsu had spent his career fighting for independence from. To parts of the family, merging with Shell’s Japanese affiliate didn’t feel like a strategic move. It felt like crossing a line.

The geopolitics didn’t help. Japan had relied heavily on Iran for crude imports at various points, including roughly 12% in 2009. Idemitsu’s relationship with Iran went back to the Nissho Maru incident itself, creating a set of historical ties and supply assumptions that sat awkwardly alongside Showa Shell’s connections to Saudi Aramco and other Gulf producers.

So when management pushed forward, the family pushed back—and the process stalled on the basic claim that these two corporate DNAs simply weren’t compatible.

Management Defiance and Legal Battles

The family’s stake—just over 28%—gave it real power, and the opposition was fierce enough to freeze progress. In October 2016, the merger process was effectively suspended. The dispute spilled into court, with the family attempting to block the transaction outright.

In July 2017, the Tokyo High Court rejected the founding family’s claims. The courts’ message was clear: shareholders could object, loudly, but management still had authority to pursue the deal as long as proper procedures were followed.

And management didn’t wait for permission to act.

In December 2016, even as the full merger was bogged down, Idemitsu purchased about 31% of Showa Shell—31.3% of Shell’s stake—after receiving approval from the Japan Fair Trade Commission. Operational partnerships in refining and logistics began in April 2017.

This created an awkward in-between world: Idemitsu had a controlling stake in Showa Shell, but not the family’s blessing to finish the job. Management pushed ahead with joint operations while negotiations continued, turning the “will they, won’t they” merger into a public corporate standoff.

Resolution and the New Giant

The merger had been announced back in 2015. It didn’t actually happen until April 1, 2019.

The breakthrough came when the Idemitsu family agreed—on conditions. Family members would join the board of the merged company. The company would keep the Idemitsu Kosan trade name, and the Idemitsu brand would remain on service stations.

At the time, Tsukioka said the refiner had secured an agreement with the largest shareholders of the founding family, a combined 14.20% stake—enough to carry the consolidation resolution at an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting scheduled for December. Under that agreement, Idemitsu accepted two Idemitsu family candidates for board directorship.

With the governance compromise in place, Idemitsu Kosan—Japan’s second-largest oil wholesaler—and fourth-ranked Showa Shell Sekiyu officially merged, creating a larger player with combined sales above JPY5 trillion (about USD45 billion). The combined refining footprint was positioned to be among Asia’s leaders, with total capacity around 1.1 million b/d.

The consolidation made Idemitsu the country’s second-largest refiner, even though the founding family—still holding just over 28%—had fought it for years.

And the settlement’s shape told you everything about what this battle was really about. Management got the strategic consolidation it said the industry demanded. The family preserved influence through two board seats and, crucially, kept the Idemitsu name at the top of the building. Whether that was a smart compromise or a reluctant capitulation became its own debate inside Japan’s corporate world.

After the merger, major shareholders such as The Master Trust Bank of Japan, Nissho Kosan, and Aramco Overseas Company B.V. held meaningful voting influence. The founding family’s power didn’t come from special voting rights—but from the simple fact that, even in a public company, the Idemitsu name still carried enough weight to negotiate board representation, including a director nominee such as Masakazu Idemitsu.

VIII. Reinvention: From Oil to Advanced Materials (2019-Present)

The OLED Materials Pioneer

Idemitsu’s reinvention didn’t start with the energy transition. It started decades earlier, when the company looked at the volatility of the oil business—especially after the global oil shocks—and decided it needed a second act.

That search led somewhere unexpected: OLEDs. Beginning in the 1980s, Idemitsu began developing OLED-related technology and materials. The work eventually fed into the broader industry push that produced practical full-color OLED displays in the late 1990s—most visibly through products introduced by Pioneer. Over time, Idemitsu’s materials and know-how made their way into the supply chains behind the smartphone era, including technology adapted by Samsung Electronics for its Galaxy line.

The signature milestone came in 1997: Idemitsu became the first company in the world to successfully commercialize a blue-emitting material—something many had long considered effectively impossible.

That mattered because OLED displays don’t work without the full RGB trio: red, green, and blue. And blue was the hard one. It was the emitter that resisted commercialization, the one that held back performance and durability. By cracking blue, Idemitsu proved it could lead at the bleeding edge of materials science—far from the refineries that made its name.

Today, Idemitsu develops, manufactures, and sells high-performance OLED materials designed to improve power efficiency, expand color range, and extend display life. It built production bases not only in Japan but also closer to demand, including in Korea and China, and established a global supply system for major display manufacturers. As the OLED market grew, Idemitsu positioned this business as a platform for next-generation electronic materials, including higher-performance blue emitters.

That strategy showed up clearly in China: Idemitsu announced it had reached full-scale OLED materials production at its Chengdu factory, with shipments set to begin in January 2021.

Along the way, Idemitsu worked across the OLED ecosystem, including efforts alongside companies such as BOE Display, Merck, Sony, LG Display, Mitsui Chemicals, Doosan, and UDC. It also formed a lighting joint venture with Panasonic—Panasonic Idemitsu OLED Lighting (PIOL)—which later dissolved after Panasonic withdrew from the OLED lighting market.

The bigger point is what this business represents inside Idemitsu. OLED materials are chemistry, precision, and manufacturing discipline—capabilities Idemitsu had spent generations building inside petroleum refining, then redeploying into a higher-value arena. It’s revenue that isn’t directly tied to how many liters of gasoline Japan burns.

All-Solid-State Batteries: The Toyota Partnership

If OLED materials were Idemitsu’s proof that it could diversify, solid-state batteries are its bet that it can help define what comes after oil.

Idemitsu began R&D on elemental technologies for all-solid-state batteries in 2001. Toyota started in 2006. And over time, the two converged on the same ambition: make all-solid-state batteries real at automotive scale.

The company’s path into batteries runs through a surprising bridge between old energy and new. In the mid-1990s, Idemitsu identified the usefulness of sulfur components and, building on decades of refining and chemical expertise, succeeded in creating a solid electrolyte. The narrative writes itself: the stuff that comes out of making cleaner petroleum products becomes an input to a new generation of electrified mobility.

Idemitsu established mass production technology for lithium sulfide in 1994. It now operates two small-scale verification facilities, and in October 2024 it started the basic design of a large pilot facility.

Strategically, it’s elegant. Sulfur compounds are generated as part of manufacturing petroleum products. Traditionally, refiners treat them as a problem to manage. Here, they become feedstock—turning a byproduct into a differentiated material business.

Idemitsu and Toyota announced they had entered into an agreement to work together on mass production technology for solid electrolytes, improving productivity and establishing a supply chain, with the goal of enabling mass production of all-solid-state batteries for battery electric vehicles. Through the collaboration, they aim to ensure successful commercialization in 2027–28.

Toyota has said the companies have worked together on materials development since 2013. Toyota also points to the scale of the intellectual-property race: over the past three years it registered more than 8,000 solid-state battery patents, with many assigned jointly with Idemitsu.

Building the Solid-State Supply Chain

Partnership announcements are easy. Supply chains are the hard part. So Idemitsu is doing what an oil major knows how to do: building plant capacity.

The company is building a new large-scale lithium sulfide plant intended to supply raw material for Toyota’s upcoming all-solid-state EV batteries. Idemitsu has announced a facility designed for annual production of 1,000 metric tons of lithium sulfide, targeting mass production by 2027.

This push fits a larger national strategy as well. Japan wants a more domestic, resilient EV battery supply chain and less dependence on overseas production—particularly in China and South Korea. Idemitsu and Toyota’s work sits squarely inside that industrial-policy frame, backed by the idea that batteries are now a national-security technology as much as an automotive one.

Based on more than two decades of development, Idemitsu has built sulfide solid electrolyte technology and accumulated many related patents. In Idemitsu’s telling, solid electrolytes are a key material for an “electrified society,” and all-solid-state batteries could be one of the rare industrial transitions where the old oil economy doesn’t just shrink—it provides feedstock, expertise, and manufacturing muscle for what replaces it.

IX. The Competitive Landscape and Strategic Assessment

Japan's Refining Industry Dynamics

By 2024, Japan’s refining business had settled into a new kind of volatility. It wasn’t just about whether people bought gasoline; it was also about what happened on paper when crude prices moved.

In the six months ended September 30, 2024, Japan’s top three refiners—Eneos Holdings, Idemitsu Kosan, and Cosmo Energy Holdings—each reported a steep drop in net profit compared to the year before, down roughly 40% to 60%. The main culprit wasn’t a collapse in day-to-day operations. It was substantial appraisal losses on oil inventories as crude prices fell.

And yet, the industry didn’t look broken. The refiners stayed profitable, and Japanese players outperformed South Korean rivals because strong domestic margins helped offset weak overseas markets.

Analysts noticed that split. Jefferies’ equity analyst pointed to solid progress in core earnings for Idemitsu and Cosmo versus their guidance, driven by underlying margins that remained strong.

Idemitsu’s own CEO, Shunichi Kito, framed it the same way: even with falling oil prices and sluggish petroleum product markets across Asia, the fuel segment held up thanks to “optimization of [the] domestic supply system.” And the overseas trading business, he said, delivered higher-than-anticipated profits.

This is the reality of Japan refining now: the market is shrinking, but the survivors can still make money—especially when they’re disciplined about supply.

That discipline has shown up in capacity coming out of the system. Eneos permanently shut its 120,000 b/d Wakayama refinery in mid-October 2023. Idemitsu closed its 120,000 b/d Yamaguchi refinery in March 2024. Industrywide, Japan’s total refining capacity fell to about 3.23 million b/d as of June 2024, down from roughly 3.45 million b/d in September 2022, according to Petroleum Statistics of Japan.

At the same time, the strategic messaging across the whole sector has converged. The big three—Eneos, Idemitsu, and Cosmo—have all laid out plans to decarbonize and to diversify away from traditional oil refining into alternatives like renewables and hydrogen.

Competitive Positioning Analysis

Idemitsu’s competitive position is unusual because it’s straddling two very different games: a mature domestic refining market on the one hand, and high-performance materials on the other.

If you look at it through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, you can see hints of multiple advantages:

Process Power shows up most clearly in the materials businesses. OLED materials and sulfide-based solid electrolyte development reflect accumulated know-how that isn’t easy to copy. Idemitsu’s ability to establish mass production technology for lithium sulfide back in 1994—then refine it over decades—creates an operational head start that new entrants can’t simply buy.

Cornered Resource shows up in the Toyota relationship. Having a deep partnership with the world’s largest automaker’s solid-state battery program—reinforced by a joint patent portfolio—creates real switching costs and mutual dependence. Other suppliers exist, but not everyone is woven into Toyota’s R&D and IP the same way.

Scale Economies still matter in the legacy business. The 2019 merger with Showa Shell made Idemitsu the second-largest refining company in Japan, and the combined company controls around 28% of the Japanese refining market.

But the constraints are just as real:

Declining Core Market is the biggest one. Refined fuel consumption in Japan is projected to keep falling, averaging -1.7% annually between 2024 and 2033. The petroleum business still supplies the vast majority of current revenue—yet it’s facing a structural downshift that no amount of execution can fully reverse.

Limited Global Scale is the second. Even as Japan’s number two, Idemitsu is still a regional player globally. Japan’s refineries were designed primarily for domestic demand, and many struggle to compete internationally against newer, larger, and more complex facilities in places like China, South Korea, and India.

Technology Execution Risk hangs over the “after oil” strategy. Solid-state batteries are not proven at mass automotive scale yet. Experts continue to warn that adoption will take time because of raw material sourcing challenges, complex manufacturing processes, and high production costs—even if the underlying technology is promising.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For long-term investors trying to gauge whether Idemitsu’s reinvention is becoming real, two indicators matter more than most:

Non-Fuel Revenue Mix: how much of total revenue is coming from advanced materials like OLED and solid electrolytes, plus power generation and other non-petroleum businesses. That mix is the clearest signal of whether the company is actually building a post-refining future. In current disclosures, these are largely captured under the “High Functional Materials” and “Power & Renewable Energy” segments.

Refining Utilization Rate: as domestic fuel demand declines, the question becomes whether Idemitsu can run a smaller refining footprint efficiently and profitably. Utilization—and the operational discipline behind it, including maintenance efficiency and avoiding unplanned outages—acts as a leading indicator for how well management is right-sizing the legacy engine without letting it turn into a drag.

X. Risks, Myths, and Investment Considerations

The Myth of the Oil-to-EV Pivot

There’s a version of this story that’s almost too neat: the swashbuckling oil refiner that reinvented itself into an EV materials champion, right on cue for the energy transition.

It makes for great copy. It’s also not how corporate reality usually works.

Yes, the solid-state battery opportunity with Toyota is real. But in the context of Idemitsu’s overall business, it’s still an early-stage bet. Even if Toyota successfully commercializes all-solid-state batteries on its intended timeline and Idemitsu becomes a meaningful supplier, it would still take years for those materials revenues to rival what refining and fuel sales generate today. In the meantime, Idemitsu has to do something very hard: run a mature, shrinking cash engine without letting it decay, while simultaneously funding and scaling the next engine. Plenty of companies have tried that two-speed transformation. Many don’t pull it off.

And the competitive pressure isn’t theoretical. The solid-state race has multiple credible players. CATL and BYD—already giants in today’s battery market—have signaled ambitions to introduce next-generation battery technology around 2027. SAIC MG, meanwhile, launched a new MG4 in August and described it as “the world’s first mass-produced semi-solid-state” electric vehicle. If Chinese competitors reach commercial scale first, Idemitsu and Toyota’s advantage could narrow quickly—especially if the market coalesces around alternatives like semi-solid solutions before true all-solid-state becomes mainstream.

Governance Overhang

The Showa Shell fight didn’t just reshape Idemitsu’s balance sheet and refining footprint. It exposed something investors can’t ignore: governance at Idemitsu isn’t purely managerial, even after the IPO and even after the merger.

The founding family still has substantial ownership and board representation. That means future strategic decisions—another merger, a spinoff, a major shift in capital allocation—could reopen the same fault lines that dragged the Showa Shell deal out for years. Even if management is right on the business logic, it may not be able to move at the speed the market expects.

Regulatory and Geopolitical Considerations

Idemitsu operates in an industry where government influence is never far away. In Japan, petroleum—and now batteries—sits squarely inside METI’s energy security framework.

That cuts both ways. The same policy agenda pushing Japan to build more domestic battery capacity, and to reduce dependence on supply chains centered in China and South Korea, helps explain why Idemitsu and Toyota’s supply-chain plans have momentum. Toyota and Idemitsu are among several leading Japanese companies investing heavily in domestic battery production, supported by a broader national effort to build resilient local capability.

But support can become a dependency. If industrial policy priorities shift—toward different battery chemistries, different domestic champions, or different geopolitical assumptions—Idemitsu’s favored positioning could change. In a company shaped by geopolitics from day one, the external environment still matters as much as the internal execution.

XI. Conclusion

Idemitsu Kosan’s story is, in many ways, the story of modern Japanese industry: Meiji-era ambition, wartime collapse, postwar rebuilding, high-growth expansion, bubble-era excess, and then decades of slower demand and forced consolidation. At every turn, Idemitsu responded less like a typical incumbent and more like an organization with a distinctive internal compass—set early by its founder’s defiant independence, reinforced by a family-like corporate culture, and expressed through a repeated willingness to try what others considered unthinkable.

The Nissho Maru voyage in 1953 wasn’t just a clever supply deal. It was a declaration: a resource-poor, newly sovereign Japan didn’t have to accept the energy rules written by empires. That same instinct showed up again and again—when Idemitsu took discounted Soviet crude and shrugged off U.S. anger, when it walked away from industry coordination it saw as anti-consumer, and, much later, when professional management pushed through the Showa Shell merger over the founding family’s resistance.

Now the question is whether that identity—so effective in an era defined by supply squeezes, cartels, and national energy insecurity—can also win in an era defined by decarbonization.

Idemitsu’s partnership with Toyota on all-solid-state batteries is a real and credible bridge into the next energy system, but it’s also a bet with meaningful execution risk, and the field is getting crowded. The OLED materials business is proof that Idemitsu can do advanced materials at world-class levels—but it still sits alongside a legacy engine that dominates the company’s scale and exposure.

As of November 2025, Idemitsu Kosan’s market capitalization stands at $9.1 billion. In that single number is the whole tension of the company: Japan’s second-largest refiner in a structurally declining domestic market, paired with a materials portfolio that has genuine technological edge, a potentially pivotal role in Toyota’s battery supply chain, and governance dynamics that can slow or complicate controversial strategic moves.

Idemitsu once sent a lone tanker into contested waters to break a blockade. Today, the blockade isn’t a navy. It’s the steady, unavoidable long-term decline of fossil fuel demand in a decarbonizing world. Whether Idemitsu’s next generation can match Sazō Idemitsu’s audacity—and translate it into execution—will decide whether this maverick stays a historical legend, or becomes something rarer: an oil company that truly earns a second century.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music