JX Advanced Metals: From Copper Mines to Semiconductor Supremacy

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a modern chip fab: a cathedral of stainless steel and filtered air, where engineers build computers by layering matter one whisper-thin film at a time. One of the workhorse steps is sputtering. You take a “target” made of an ultra-pure metal, blast it with argon ions, and the knocked-loose atoms redeposit onto a silicon wafer as a uniform layer only nanometers thick.

Here’s the catch: if that target has the wrong microstructure, or even trace impurities, those defects can turn into particles, shorts, and yield loss. In a business where a single production line can represent billions of dollars of output, “close enough” isn’t close. It’s catastrophic.

Now for the part that sounds almost impossible: one company supplies roughly 60% of the world’s sputtering targets, a quiet choke point in semiconductor manufacturing. And yet outside of process engineers and supply-chain insiders, almost nobody can name them. So how did a 120-year-old Japanese company—one that began by pulling copper ore out of the mountains—end up as a critical supplier to TSMC, Samsung, and Intel?

The public markets got a reminder in March 2025. JX Advanced Metals debuted on the Tokyo Stock Exchange on March 19, rising 6.6% on day one after an IPO that raised about ¥439 billion, Japan’s biggest listing since SoftBank’s blockbuster years earlier. By the close, shares finished at 874 yen, valuing the company at roughly ¥810 billion.

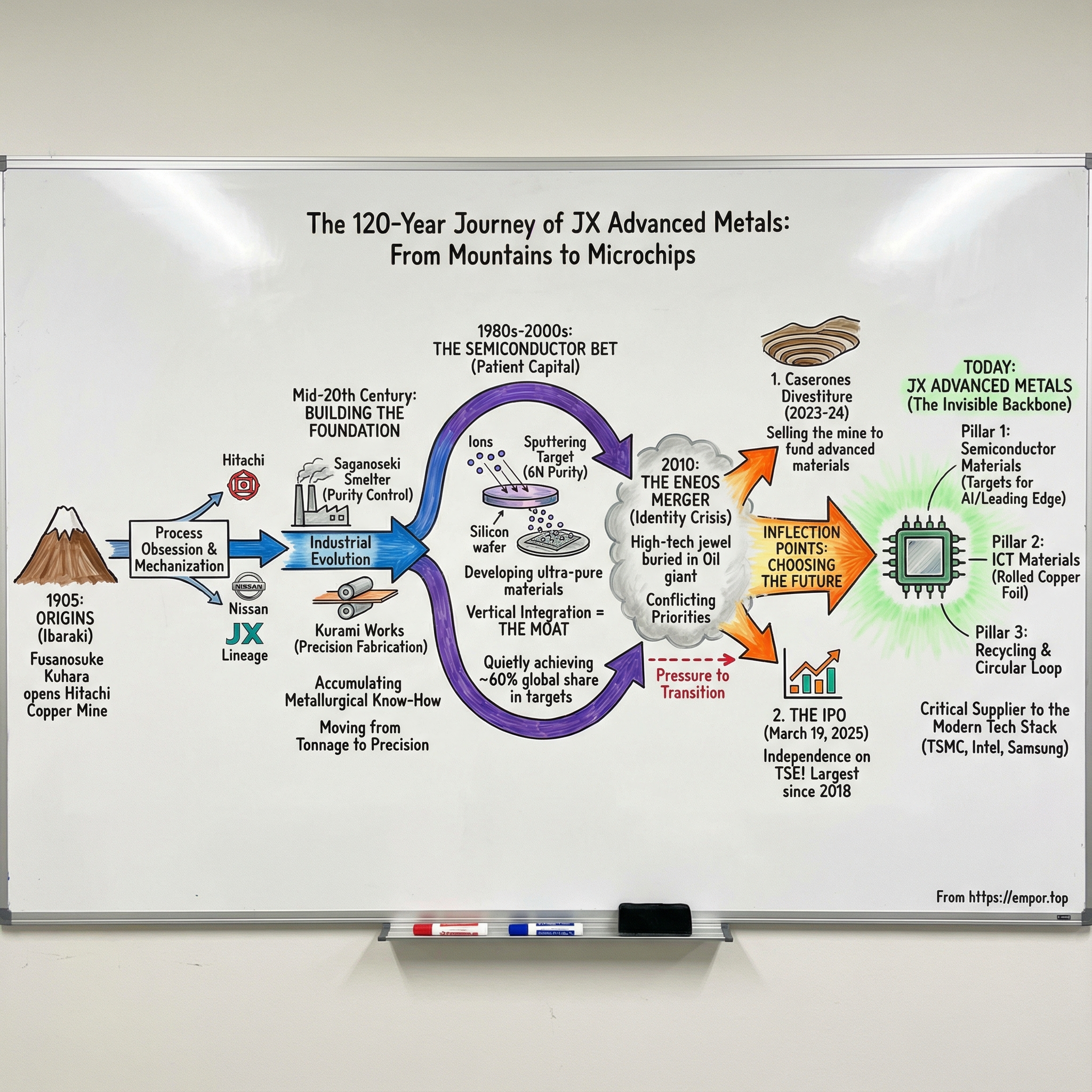

That moment wasn’t the beginning of the story—it was the reveal. Because JX Advanced Metals is the product of a century-long transformation that runs straight through Japan’s industrial history: zaibatsu empires, war-era production, postwar rebuilding, a strange marriage into an oil conglomerate, and then a deliberate pivot away from being a “dig-and-smelt” company toward becoming a technology materials company. Not a business measured in tons and railcars, but in purity, crystal structure, and atoms.

It starts in 1905, with Fusanosuke Kuhara opening the Hitachi Mine. That one mine would end up seeding three household names—Hitachi, Nissan, and what ultimately becomes JX Advanced Metals. The same industrial DNA that built Japan’s heavy manufacturing base would, decades later, be refit for the semiconductor age.

And this isn’t just corporate genealogy. It’s a playbook for building a moat in materials science—where the competitive advantage is earned in metallurgy labs, production discipline, and hard-won customer trust. We’ll follow the choices that mattered: why JX ultimately sold down a major copper mine in Chile to focus on advanced materials, and how a high-tech crown jewel spent years buried inside Japan’s largest oil refiner before finally stepping out on its own.

If you’re a long-term, fundamentals-driven investor, JX Advanced Metals is a rare kind of case study: a newly independent, globally critical supplier with a deep moat, sitting at the center of the AI chip buildout—yet still largely invisible to the public. Let’s dig in.

II. Founding & The Kuhara Era: A Mine That Spawned Giants (1905–1928)

In the winter of 1905, a 35-year-old entrepreneur named Fusanosuke Kuhara walked a copper deposit in Ibaraki Prefecture and saw more than ore. He saw a platform—a place where modern engineering could turn a remote mountain site into an industrial engine.

Kuhara wasn’t a prospector who got lucky. He was part of Japan’s rising industrial class, born in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, into a family of sake brewers with unusually powerful connections. His brother went on to found Nippon Suisan Kaisha, and his uncle, Fujita Densaburō, built the Fujita zaibatsu. Kuhara studied at Tokyo Commercial School (the predecessor of Hitotsubashi University) and graduated from Keio University—training that mattered in a period when “industry” was becoming as much finance and logistics as it was furnaces and shafts.

After school, he joined Morimura-gumi. Then, on the recommendation of former Chōshū leaders such as Inoue Kaoru, he moved into his uncle’s firm, Fujita-gumi (today’s Dowa Holdings). In 1891, he was sent north to manage the Kosaka mine in Akita—one of Japan’s major lead, copper, and zinc operations.

Kosaka is where Kuhara learned the lesson that would define everything that came next: mining is not just geology. It’s process. He brought in new technologies, drove efficiency, and made the operation highly profitable. He wasn’t simply extracting metal; he was building a system for extracting value.

So when Kuhara left Fujita-gumi in 1903, he was ready to do it on his own terms. In 1905, he acquired the Akazawa Copper Mine in Ibaraki and renamed it the Hitachi Copper Mine. Today, “Hitachi” reads like a brand. Back then, it was just a mountainous place name attached to a very aggressive idea: build a modern mine, mechanize it, and scale.

Kuhara moved fast. He opened the Hitachi Mine in 1905 and quickly built it into one of Japan’s four largest copper mines. In 1912, he established Kuhara Mining Co., which soon became one of the country’s leading nonferrous players. The differentiator wasn’t a secret vein of copper. It was Kuhara’s obsession with mechanization at a time when many mines still leaned heavily on manual labor. The results showed up quickly: by 1914, Hitachi had become Japan’s second-largest copper producer, powered by mechanization and improved production techniques.

Then comes the part that feels almost like a corporate origin myth—except it’s real.

Hitachi Mine was deep in the mountains, far from urban life. Kuhara understood that if he wanted stability and scale, he needed an environment where employees could actually live and work with peace of mind. That meant infrastructure: not just for the mine, but for the people around it.

And it meant equipment. Mines break things. Mines need power. Mines need repairs. Kuhara invited engineer Namihei Odaira to join the Hitachi development project. Odaira took a role at the mine, and within the engineering department, a small workshop to repair electrical equipment became indispensable. That repair shop—inside a copper mine—would become the seed of Hitachi, Ltd. The workshop’s origin site in Odairadai was even restored in 1956, a physical reminder of the company’s beginnings.

Sit with that: a maintenance function created to keep a mine running turned into one of Japan’s great industrial conglomerates.

Odaira later pointed to three reasons Hitachi grew: diligent colleagues, support from Kuhara and Yoshisuke Aikawa, and trust from customers. That second name—Aikawa—matters. Because Kuhara’s story isn’t just about building. It’s also about overreaching.

During World War I, Kuhara expanded aggressively, pushing into shipbuilding, fertilizer, petrochemicals, life insurance, trading, and shipping—assembling what became known as the Kuhara zaibatsu. But the post-war depression exposed the strain. The empire was too broad, too fast, and too leveraged. Kuhara couldn’t keep it together in its original form.

So he turned to his brother-in-law, Yoshisuke Aikawa. Aikawa reorganized the business under a holding company called Nihon Sangyō—Nissan for short. Kuhara Mining, the core operation, was effectively transferred to Aikawa during the late Taishō period. Aikawa would later be known as the founder of Nissan Motor.

One copper mine. Three titans: Hitachi, Nissan, and the industrial lineage that ultimately becomes JX Advanced Metals.

That’s the founding legacy here—and it’s more than trivia. From day one, this business treated technology as the lever. Not “we have metal,” but “we know how to turn metal into something more valuable.” In 1905, that meant mechanized mining and modern operations. A century later, it would mean ultra-high purity materials and manufacturing discipline at the atomic level. The throughline is already visible.

III. From Zaibatsu to Reorganization: The Mining Business Evolves (1929–2000)

In 1929, the Nissan Group’s mining division split off to form Japan Mining Co. Over time, through a long series of industry reorganizations, that lineage eventually rolled into what became Nippon Mining Holdings.

What followed was seven decades of Japanese corporate history at its most labyrinthine: war, occupation, dissolution, and reconstruction. The names on the buildings changed. The underlying capabilities—mining, smelting, refining—kept getting sharper.

After World War II, the American occupation moved to break up the zaibatsu that had powered Japan’s wartime economy. Plenty of businesses were dismantled or reshuffled beyond recognition. But mining and metals largely endured. Japan needed raw materials and industrial capacity to rebuild, and these operations were simply too foundational to disappear.

This is where Saganoseki enters the story.

To expand the core businesses of mining, smelting, and refining, the company built the Saganoseki Smelter & Refinery in Oita Prefecture, one of the largest facilities of its kind in Japan. It still matters today: a major center of the JX Advanced Metals group, and a leading-edge smelter with world-class technology and production capacity.

Saganoseki wasn’t just a big plant. It was a decades-long exercise in process mastery.

In the early 1970s, as copper demand climbed and Japan tightened environmental regulations, the smelter underwent a major renovation. The first phase of expansion and modernization was completed in 1970, including a key upgrade: replacing blast furnaces with a flash furnace. In 1973, a second flash furnace came online. Together, this created a fully modernized seaboard copper smelter, with annual copper concentrate smelting capacity of 240,000 metric tons in copper content.

Over time, Saganoseki became one of the world’s largest and most efficient copper smelters, built around a few signature features: a flash furnace using hot blast at 1,000°C (with or without oxygen enrichment), labor-saving P-S type converters, a distinctive combination of magnetic separation and flotation for converter slag, and a double anode casting machine capable of casting 80 metric tons per hour.

It also implemented a hybrid process that uses the heat generated by ore oxidation during smelting to produce copper anodes with almost no fossil fuels.

On the surface, this reads like industrial trivia. But it’s actually the prequel to the semiconductor era.

Because what you’re really seeing here is the steady accumulation of metallurgical control: how to drive impurities down, how to manage temperatures and chemistry precisely, how to produce consistent quality at massive scale. Those are the same muscles you need later when the product isn’t copper wire, but a material so pure and uniform that a chip fab will trust it on a leading-edge line.

The other quiet shift happened downstream.

With the startup of the Kurami Works in Kanagawa Prefecture, the company made a strong entry into metal fabrication. Outfitted with the latest rolling mills, it produced phosphor bronze and other rolled copper products—and, crucially, learned to compete in a world of small lots, production-to-order, and demanding specs. It wasn’t just “make copper.” It was “make the exact copper product this customer needs, every time.”

That move matters because it changes what kind of business you are.

Mining is a hunt-and-extract game, and the output is a global commodity. Metal fabrication is where know-how starts turning into differentiation, and differentiation turns into pricing power.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Japan’s domestic mines were depleting, and the company faced a strategic crossroads. It could stick to the traditional mining playbook—go abroad, buy resources, chase volume—or it could lean harder into what it was increasingly good at: processing, precision, and advanced manufacturing.

It chose both paths, but the center of gravity was already shifting toward technology. And that decision set up everything that came next.

IV. The Semiconductor Bet: Building an Invisible Empire (1990s–2010s)

The company didn’t stumble into semiconductors at the last minute. It started building an electronic materials business in time for the electronics boom of the 1980s—making sputtering targets for semiconductors, transparent conductive films for liquid crystal displays, and materials for compound semiconductors.

That move sounds incremental. It wasn’t. It was the strategic insight that turned a mining-and-smelting lineage into a quiet force inside the most unforgiving manufacturing industry on Earth. Electronics were scaling fast, performance expectations were rising even faster, and somebody had to deliver the materials that could keep up.

To understand why this bet worked, you have to understand what a sputtering target actually is.

Inside a chip fab, you constantly need to lay down extremely thin metal films—often as interconnect material—on a wafer. You can’t just pour molten metal on it; the heat would destroy the delicate structures already built on the silicon. So instead, you put a disk of ultra-pure metal—the “target”—into a vacuum chamber, bombard it with ions, and knock atoms off the target. Those atoms then deposit onto the wafer as a controlled, uniform film.

In that step, everything comes down to the target. Its purity. Its internal structure. Its consistency from batch to batch. If the target sheds particles or behaves unpredictably, it can ruin yields. And in chipmaking, yield isn’t a metric—it’s the business.

That’s why JX pushed copper targets to 6N purity, meaning 99.9999% or higher. The company developed this level specifically to reduce particulate matter during sputtering. And crucially, it could do this reliably because it controlled the chain end-to-end: resource extraction, smelting and refining, and then target manufacturing. That vertical integration wasn’t a nice story for an annual report. It was the mechanism that let JX ship a “world-standard” 6N target with supply reliability customers could bet fabs on.

As devices demanded lower power and faster processing, fabs needed a widening menu of high-quality targets. JX delivered them through stable processes that ranged from high-volume production to specialized, custom-developed products. And it backed that with manufacturing and service sites across Japan and the world—so it could support customers with technical help, sales coverage, and dependable delivery when schedules were tight.

The company also kept more of the process in-house than most competitors. From forging and rolling through to target manufacturing, it used extremely pure raw materials and controlled properties like grain size and crystal orientation—details that directly affect sputtering performance. The point wasn’t just purity in a lab sense. It was repeatability in a fab sense.

This is the real moat: not a single breakthrough, but decades of accumulated process control, refined into something chipmakers could trust. JX didn’t buy a semiconductor materials business and bolt it on. It grew one out of the same metallurgical discipline it had been compounding since Hitachi Mine and Saganoseki—then aimed that discipline at a market where “close enough” doesn’t survive qualification.

By the 2010s, that compounding showed up in dominance. Goldman Sachs highlighted the company’s leading position, citing a global share in sputtering targets for semiconductors in the mid-60% range, along with a very high share in rolled copper foil for flexible printed circuits—both core franchises.

It’s hard to overstate what that implies. In an era when semiconductor supply chains are treated like national infrastructure, a single Japanese supplier held a controlling position in a material that essentially every advanced chip needs.

And JX wasn’t only shipping virgin material into the system. It ran a full-spectrum nonferrous metals operation—copper and minor metals—spanning resource development, smelting and refining, and then the development and manufacture of advanced materials used in an IoT- and AI-driven world. It also built in recycling from end-of-life electronics and devices, recovering precious and specialty metals and feeding them back into the supply chain. That circular flow strengthened supply security and aligned with the rising pressure for more sustainable industrial processes.

Then, in July 2018, the company widened its aperture beyond copper. JX acquired the outstanding shares of Germany’s TANIOBIS, one of the world’s leading suppliers of tantalum and niobium powders and related products used in capacitors, semiconductor materials, and surface applications.

TANIOBIS, together with other group capabilities like Tokyo Denkai Co., Ltd., expanded what JX could reliably supply: metal powders for capacitors and semiconductor materials, high-purity oxides for SAW devices and optical lenses, chlorides for semiconductors, and additives used in superalloys. It was another step toward being a one-stop, high-trust supplier of the obscure materials that modern electronics quietly depend on.

Strategically, the logic was simple. If you’re going to be world-class at copper targets, you don’t stop at copper. You move into the adjacent “must-work” materials that fabs and component makers consume alongside it—and you bring the same playbook: purity, process stability, and supply reliability.

Looking back, the defining feature of this era wasn’t a flashy pivot. It was patient capital allocation. JX spent decades building semiconductor materials capability before the world started talking about chip supply chains like they were geopolitics. When that moment arrived, the company wasn’t scrambling to catch up. It was already embedded.

V. INFLECTION POINT #1: The ENEOS Merger & Identity Crisis (2010)

In 2010, Nippon Mining Holdings and Nippon Oil merged to form JX Holdings—what eventually became today’s ENEOS Holdings—bringing the metals business that would later be called JX Advanced Metals under an energy supermajor’s roof.

Mechanically, the deal was straightforward. On April 1, 2010, the new holding company was established through a joint share transfer by Nippon Oil Corporation and Nippon Mining Holdings. Strategically, it also made sense on the surface: Japan’s petroleum industry was consolidating as domestic fuel demand weakened, and combining a refining-and-distribution giant with a resources-and-metals giant promised scale, stability, and diversification.

ENEOS quickly became enormous. By the early 2010s it employed tens of thousands of people globally, ranked among the world’s largest companies by revenue, and sat inside the Mitsubishi Group orbit through Nippon Oil’s corporate lineage.

But inside that scale, something awkward happened. A high-tech semiconductor materials business—small compared to oil in revenue, but growing fast and earning attractive margins—ended up living inside a company whose center of gravity was oil refining: capital-intensive, cyclical, and increasingly defined by long-term decline.

That mismatch wasn’t philosophical. It was operational. Every capital allocation meeting implicitly asked the same question: do we prioritize sustaining and transforming the energy business, or do we pour more into a materials franchise riding the digitization wave? Managing both under one roof meant permanent trade-offs.

Over time, the tension became public. ENEOS began talking openly about the energy transition—renewables, hydrogen, and a world moving toward carbon neutrality—while also acknowledging the broad shocks hitting industrial planning: COVID-19, geopolitical risk, slowing growth, and rising expectations around sustainability goals. In its long-term vision, the group framed its mission as balancing “the stable supply of energy and materials” with the realization of a carbon-neutral society.

And then came the logical conclusion. According to a Nikkei report, ENEOS considered spinning off its metals unit, JX Nippon Mining & Metals, and also weighed listing it—because there was little overlap with the core refining business, and because petroleum demand was expected to shrink.

ENEOS ultimately described the decision in portfolio terms: to build the business mix required by its long-term vision, it needed to deploy management resources with a longer time horizon. After evaluating potential synergies between its growth priorities and the metals business—and recognizing the fundamental differences in business characteristics—it concluded that listing shares of JX Nippon Mining & Metals was the best path to sustainably raise corporate value for both sides.

For investors, this era is a classic conglomerate lesson: when a high-growth, technology-driven business sits inside a parent facing secular decline, both get distorted. The parent can’t fully commit to its transition because it leans on the subsidiary’s earnings. The subsidiary can’t invest as aggressively as it should because its budget competes with the parent’s urgent, existential priorities.

Once ENEOS recognized that structural mismatch, the story could move again. And it did—through two more inflection points: a major mining divestiture, and then an IPO that finally made the advanced materials business legible on its own terms.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Caserones Divestiture—Choosing Your Future (2023-2024)

Four thousand meters above sea level in Chile’s Atacama Desert sits the Caserones Copper Mine. It’s a massive open-pit operation—and for JX, it became the symbol of two things at once: the ambition to be a serious global resource developer, and the willingness to walk away from that identity when the future demanded it.

JX secured the mining rights to the Caserones copper deposit in 2006. Then came the long, unglamorous middle: feasibility studies, stripping, and construction. In 2013, the mine began producing refined copper using the SX-EW method. Full-scale copper concentrate production followed in May 2014.

None of this was easy. Caserones sits in steep terrain at over 4,000 meters, where altitude turns everything—labor, logistics, equipment, even schedules—into a harder problem than it looks on paper. The operation also had to push through weather issues and the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. But by the early 2020s, the mine had reached stable operation and improving productivity. In November 2022, it hit a major milestone: cumulative production reached one million tons of copper content.

In other words, after years of investment and struggle, Caserones was finally doing what it was supposed to do.

And then JX sold control.

In July 2023, Lundin Mining Corporation entered into a binding agreement with JX Nippon Mining & Metals and its subsidiaries to acquire 51% of SCM Minera Lumina Copper Chile (Lumina Copper), the subsidiary that operates Caserones. The deal included $800 million in upfront cash consideration and $150 million in deferred cash consideration payable in installments over six years after closing. Lundin also received the right to acquire up to an additional 19% interest for $350 million over a five-year period beginning on the first anniversary of closing.

The “why” wasn’t subtle. JX put it directly in the language of its JX Nippon Mining & Metals Group Long-Term Vision 2040: it aimed to move from a process industry-type firm to a technology-based firm, and to become a global company that contributes to society through advanced materials. As part of that shift, it had been reviewing its asset portfolio—and decided to transfer its shares in MLCC to Lundin.

Translated into plain English: JX was choosing to be a technology company, not a mining company.

The logic was also financial and strategic. The company said the move would help it concentrate further on businesses centered on advanced materials, reduce exposure to the volatility of the resource business, and strengthen its long-term earnings base.

Then, in 2024, the second step landed. JX Advanced Metals agreed to sell an additional 19% stake to Lundin for $350 million, reducing its ownership to 30% and increasing Lundin’s to 70%. This followed the initial 51% sale in 2023, which had included a call option for Lundin to acquire that additional 19% within one to five years.

By the end of the process, JX had effectively monetized most of the asset—roughly $1.3 billion in value for 70% of a mine it had spent years bringing to life—while keeping a 30% stake. That remaining stake still mattered: copper remained essential to JX’s smelting operations and to the broader materials supply chain it depended on.

Internally, this wasn’t just a sale. It was a transition driven by hard-earned experience—especially the cost and complexity of Caserones. With a minority position retained, JX could secure access to key metals while redirecting capital and management focus toward the business it believed would define its future: advanced materials, including sputtering targets for semiconductors.

For anyone trying to understand the move, the takeaway is optionality. Mining demands huge, lumpy bets and lives at the mercy of commodity cycles. Semiconductor materials is a game of continuous improvement, long qualification cycles, and technical lock-in. By selling down Caserones while keeping a meaningful minority stake, JX converted a volatile, capital-intensive asset into fuel for technology investment—without fully walking away from resource security.

This was the courage to divest: letting go of an asset right as it reached peak operational stability, because the strategy said the center of gravity had to move elsewhere.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #3: The IPO—Independence at Last (March 2025)

After selling down Caserones and making its priorities unmistakable, the next step was inevitable: get the advanced materials business out from under the oil giant and let the market price it on its own merits.

On March 19, 2025, JX Advanced Metals listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market. The IPO raised about ¥439 billion, making it Japan’s biggest listing since SoftBank’s 2018 blockbuster. In its first day of trading, the stock jumped roughly 6%.

Investors weren’t just buying “a metals company.” They were buying a supplier embedded in the supply chain of the world’s most important fabs. JX Advanced Metals provides key materials used in chipmaking, selling to customers that include TSMC and Intel—right as the industry was pouring capital into advanced AI-focused semiconductors.

The transaction also made the parent company’s motivation plain. ENEOS sold shares at ¥820 each, priced at the top end of the marketed range, and the overallotment option was exercised. ENEOS had been explicit about what it wanted from this: more cash for shareholder returns and, more importantly, funding to accelerate its shift toward decarbonization—hydrogen, synthetic fuels, and the broader energy transition.

The company’s own framing captured the trade: ENEOS would be able to move faster on strategic investment and portfolio transformation, while JX Advanced Metals would gain a management structure built for highly specialized, rapid decision-making, with a capital structure suited to its business characteristics—and more room to invest in R&D and capacity.

Internally, the listing was treated as a finish line. As of March 19, 2025, with the shares officially listed, JX Advanced Metals concluded it had achieved the purpose of its IPO preparations and dissolved the IPO Office.

The timing helped. The offering landed during a choppy moment for markets, with investors digesting trade-war uncertainty, tariff concerns, and recent weakness in tech and chip stocks tied to questions about AI spending. And yet demand for the deal still came through—an indication that, even with macro noise, the market understood the durability of JX’s position in a category where qualification cycles are long and switching is painful.

Financially, the company’s reported revenue had declined versus the prior year—a reflection of the Caserones divestiture and the broader strategic refocus. The point wasn’t to maximize tonnage anymore. It was to concentrate on higher-value semiconductor materials and build a business that could grow earnings through technology and process advantage, not commodity exposure.

For long-term investors, that’s what makes the IPO more than a corporate event. It marked the moment JX Advanced Metals stopped being a high-tech crown jewel buried inside an oil refiner and became, at last, a standalone company—free to allocate capital, pursue acquisitions, and invest in R&D with one clear north star: advanced materials for the semiconductor era.

VIII. The Business Today: Anatomy of a Hidden Champion

Today, JX Advanced Metals is a Japanese non-ferrous metals company that still has ENEOS as a major shareholder. It operates across the full arc of the metals value chain: resource development, smelting and refining, advanced materials manufacturing, and recycling.

But the important point isn’t that it “does metals.” It’s what kind of metals business it chose to become.

At the center of the company is a portfolio of advanced materials made from copper and rare metals that are indispensable to semiconductors and telecommunications. In practice, that boils down to a few product categories that sit directly inside modern electronics, and where JX has earned unusually strong positions.

The business runs across three interconnected pillars, each reinforcing the others:

Semiconductor Materials is the crown jewel. JX holds roughly 60% share in sputtering targets, the ultra-high-spec metal disks used to deposit thin films in chipmaking. These targets are not generic commodities; they’re precision-engineered inputs that have to perform reliably in the most yield-sensitive manufacturing environment in the world. JX supplies targets made from copper, tantalum, tungsten, and specialty alloys, and its customer list spans essentially every major semiconductor manufacturer.

The technology stack here is all about reducing particles, maintaining film uniformity, and supporting higher-power processes. For example, JX uses powder sintering to produce tungsten targets at 5N purity (99.999% or above) and very high density, enabling both high quality and scalable production. And as high-power sputtering becomes more common, it also sells diffusion-bonded products that increase bond strength between the target and the backing plate—improving thermal resistance and stability in demanding conditions.

ICT Materials is the quieter monster business. This segment includes rolled copper foil for flexible printed circuits—the substrate that makes bendable electronics possible in smartphones, wearables, and countless other devices. JX’s global share here is around 80%, even more dominant than its position in sputtering targets. If sputtering targets are a choke point for leading-edge chip production, rolled copper foil is a choke point for the physical connectivity of modern devices.

Materials & Recycling is the foundation that makes the first two pillars harder to copy. This is where the company smelts and refines metals, produces and recovers a broad set of non-ferrous outputs, and feeds material back into the system through recycling. On an annual basis, JX Metals produces 450,000 tonnes of copper, seven tonnes of gold, 200 tonnes of silver, 0.6 tonnes of platinum, and 2.7 tonnes of palladium.

This breadth is also why the company can credibly talk about a “closed loop” at industrial scale. As one industry observer, Zipfel, puts it: “We do resource development, mining, R&D work to maximise the output volume and quality of our concentrates, refining, and we offer final products to the market, for example electronics and semiconductor manufacturers.” In his view, enabling a closed loop for copper and other important technology metals at this scale is “pretty unique.”

That push shows up in operations. JX has aimed to develop its sites into global hubs for nonferrous metal recycling by improving transportation efficiency and expanding its ability to accept recycled materials. At Saganoseki, the company has been upgrading preprocessing technologies so it can smelt and refine larger volumes of recycled feedstock—which often arrives mixed with plastics and other impurities that have to be separated before the metal can be recovered.

There’s also a credibility marker here. On December 15, 2022, the Saganoseki Smelter & Refinery and Hitachi Refinery, operated by JX Metals Smelting Co., Ltd., received The Copper Mark. The assurance process began in March 2022 and included an independent third-party assessment against environmental, human rights, community, and governance criteria. The result: JX became the first refinery operator in Japan to be granted the Copper Mark.

All of this ties back to the moat. Vertical integration isn’t a slogan here—it’s an engineering and quality system. JX can control purity and consistency from smelting through to the finished sputtering target, and that end-to-end visibility is difficult to match.

The company has also been tightening that chain in key rare metals. In April 2022, Tokyo Denkai Co., Ltd. became a wholly owned subsidiary, adding technology and capacity for smelting and refining high-melting-point metals. Tokyo Denkai manufactures ingots used for tantalum sputtering targets and had already been an important partner to JX’s Thin Film Materials Division. Combined with the TANIOBIS business—particularly powdered tantalum for sputtering targets—bringing Tokyo Denkai fully in-house further strengthened the group’s vertically integrated supply chain and the resilience of supply for these products.

The adjacent growth bets are clearly in view, too. “Together with JX Advanced Metals, we recognize significant growth potential in the fields of atomic layer deposition (ALD) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for the next generation of semiconductors,” explains Kazuhiko Iida, Chairman of the TANIOBIS Group. “By expanding our capacities in Goslar, we want to strengthen our market position, and respond flexibly to increasing requirements. We see great potential in the chloride sector in particular – both for JX and for TANIOBIS.”

Geographically, JX’s footprint spans Japan, Germany, the United States, Taiwan, and Chile, putting manufacturing and support close to the places where advanced semiconductors are actually built.

For investors, the cleanest way to understand the company is as a picks-and-shovels play on the semiconductor boom. Chip architectures change. Winning chip companies rotate. But the manufacturing stack still relies on thin films and sputtering—and when fabs need targets they can qualify and trust, JX is one of the first calls.

IX. Playbook: Strategic & Business Lessons

JX Advanced Metals is a case study in how industrial companies survive—not by chasing the next trend, but by steadily moving up the value chain until the market can’t function without them. Here are the lessons that show up again and again in this story:

The 120-Year Pivot: The most important shift JX made wasn’t from “mining to semiconductors.” It was from seeing itself as a resource company to understanding its real edge: metallurgy. Mines run out. Commodity cycles swing. But the ability to purify, process, and precisely manufacture metals can be redeployed into entirely new product categories—if you have the discipline to do it.

Niche Dominance Strategy: JX didn’t try to win every corner of materials. It went after the places where specs are brutal, customers are conservative, and switching is painful. Semiconductor-grade sputtering targets are the perfect example: qualifying a new supplier takes years, and the downside of getting it wrong is measured in yield loss and ruined production runs. Once JX is qualified and embedded, it’s not just a vendor—it’s part of the process.

Vertical Integration as Moat: JX’s end-to-end control—from upstream metals processing to finished targets—reads like old-school industrial strategy. In semiconductors, it becomes a modern competitive weapon. When performance hinges on trace impurities and repeatability, owning the chain isn’t mainly about margin. It’s about being able to guarantee what you ship, batch after batch, under the most unforgiving customer standards in manufacturing.

The Courage to Divest: Selling down Caserones after it finally reached stable operation is the kind of move that looks irrational if you’re optimizing for tradition, scale, or pride. It makes perfect sense if you’re optimizing for the next decade. JX chose to monetize a high-quality, hard-won mining asset to fund the business it believed would compound faster: advanced materials. That’s disciplined capital allocation—and a willingness to break with identity.

Patient Capital: This dominance didn’t appear overnight. JX spent decades building semiconductor materials capability long before it became a headline issue or a geopolitical talking point. It invested through cycles, downturns, and corporate reshuffles. Then the world hit a moment—AI buildouts, leading-edge fabs, supply-chain scrutiny—where those capabilities went from “nice business” to “critical infrastructure.”

Corporate DNA Preservation: Through mergers, spin-offs, and reorganizations, the core technical skill stayed intact. The company kept compounding the same underlying know-how—purification, process control, fabrication discipline—across generations. That continuity is rare, and it’s a big part of why the moat is so hard to copy: the advantage isn’t a patent. It’s accumulated capability.

If you’re looking for similar opportunities as an investor, the pattern to watch for is straightforward: deep technical moats in overlooked niches, products with high qualification and switching costs, a long history of capability-building, and leadership willing to trade short-term comfort for long-term positioning.

X. Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into semiconductor-grade materials is brutally hard. Yes, it takes money—JX invested more than $90 million from 2021 to 2023 to expand sputtering target capacity—but capital is only the entry ticket.

The real barrier is accumulated know-how and customer trust. JX has been compounding metallurgical expertise for over a century, and semiconductor fabs don’t “try” new suppliers lightly. Qualification cycles typically run 12 to 24 months, and the failure mode is existential: one impurity issue can cascade into contamination, yield loss, and massive financial damage. That’s why new entrants don’t just compete with existing suppliers. They compete with the industry’s bias toward proven, already-qualified materials.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

JX is unusually insulated from supplier pressure because it’s vertically integrated. It operates smelting and refining, which gives it more control over high-purity inputs than a typical downstream materials company. Acquiring TANIOBIS extended that control into tantalum and niobium, and retaining a 30% stake in Caserones preserves an element of copper supply security.

Supplier power still shows up where the raw materials are inherently concentrated—especially for certain rare earths and specialty metals, with heavy geographic concentration in places like China. JX counters that risk through diversified sourcing and investments such as the Mibra Mine in Brazil for tantalum.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-LOW

The customers here are giants—TSMC, Samsung, Intel—with serious purchasing leverage. But that leverage hits a wall called switching costs.

Changing a sputtering target supplier isn’t a procurement exercise; it’s a manufacturing risk event. It means long testing cycles, process tuning, and yield verification. And it carries the downside fabs fear most: contamination, yield loss, and disruption to production ramps.

That reality is why JX’s roughly 60% market share matters. It’s not just scale—it’s technical lock-in backed by qualification history. Buyers may negotiate, but they pay for reliability because the cost of failure dwarfs the cost of the material.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

For interconnect deposition in leading-edge chips, sputtering remains the workhorse. Industry roadmaps are largely committed to it for years, and there’s no clean replacement that offers the same combination of performance and manufacturability at scale.

Other deposition methods like CVD and ALD aren’t direct substitutes; they serve different use cases and require different source materials. Importantly, JX is positioned to participate there too through the TANIOBIS business, which supplies materials used in those next-generation processes.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

This is not a winner-take-all monopoly, but it isn’t a fragmented commodity market either. Roughly a dozen global players control more than half of total output, with companies like JX Nippon, Honeywell, and Praxair among the leaders.

And competition isn’t primarily fought on price. It’s fought on quality, consistency, and the ability to support customers when things go wrong. In chipmaking, material cost is small compared to wafer processing cost—and microscopic compared to the cost of yield problems. So fabs optimize for performance and stability, not the lowest bid.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: STRONG

Scale is a meaningful advantage in this business because the fixed costs are relentless: R&D, quality systems, analytical equipment, and global support. JX’s market position lets it spread those costs across more volume than most rivals.

Its long-running investments in industrial capability support that advantage. At Saganoseki, upgrades over decades increased flash smelting furnace capacity dramatically from the original baseline. Aging and degradation over time required replacement and modernization, and facility modifications—including gas treatment for off-gas—were made to support the higher capacity.

Network Effects: WEAK

This isn’t a platform business. A target supplier doesn’t get more valuable because more customers use it. The “network” here is reputation and qualification history, not a self-reinforcing user loop.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

Legacy mining companies can’t easily pivot into semiconductor-grade materials. The capabilities, tolerances, and customer expectations are fundamentally different.

And the conglomerate structure matters too. When a high-growth, high-spec materials business sits inside an oil-focused parent, it’s easy for management to underinvest, undervalue, or misunderstand it. That dynamic created room for a focused, stand-alone JX Advanced Metals to be managed like what it actually is: a technology materials company.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the heart of the moat. Qualification cycles commonly take 12 to 24 months. Any change in material risks contamination and yield impact. Even if a competitor offers a lower price or a marginally better spec, fabs still have to weigh transition risk—one of the most expensive categories of risk in manufacturing.

Once JX targets are qualified on a production line, displacement tends to require overwhelming proof and a customer willing to accept the operational risk of change.

Branding: MODERATE

JX isn’t a consumer brand, but in the world that matters—process engineers, yield teams, procurement—its reputation carries weight. “JX quality” effectively means predictable performance and dependable supply in an industry that prizes those traits above almost everything else.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

A century of purification and processing expertise isn’t something a competitor can rush into existence. JX also benefits from deep relationships across the semiconductor ecosystem, including with equipment makers—relationships that influence how processes are designed and tuned in the first place.

That strategic direction is explicit in the JX Nippon Mining & Metals Group Long-Term Vision 2040, which treats rare metals essential to advanced materials as a core domain alongside copper. TANIOBIS and the broader group have been expanding in functional tantalum powders and other advanced materials as part of that push.

Process Power: VERY STRONG

JX’s advantage isn’t just that it can make targets—it’s that it can make them consistently, at scale, with uniform properties, including for large-format targets. That reliability comes from manufacturing disciplines built over decades: high-purity and alloying technology, tight structure control, and comprehensive quality assurance backed by advanced analysis and evaluation equipment.

The company pairs that with technical service and a global footprint of processing plants that support flexible delivery and business continuity. Put it together, and you get the hard-to-copy capability that matters most in this category: the ability to repeatedly deliver ultra-high-purity targets—up to 6N purity—while controlling grain structure and orientation in ways fabs can trust.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Semiconductors are moving into what some analysts are calling a “giga cycle”: not just a normal upturn, but a synchronized surge across compute, memory, networking, and storage, pulled forward by AI. Creative Strategies frames it as a restructuring of the economics of the entire stack at once. And the headline implication is big: after a roughly $650 billion global semiconductor market in 2024, multiple forecasts now point toward the industry approaching the trillion-dollar level by the late 2020s, with AI doing most of the heavy lifting.

That matters for JX because its best products aren’t optional in a modern fab.

In a world where leading-edge nodes keep shrinking, 3D NAND keeps stacking, and advanced packaging keeps getting more complex, thin-film deposition remains a core workhorse process. That keeps demand growing for high-purity sputtering targets—the kind where materials science, not just metal supply, determines yield.

Market researchers put numbers around that tailwind. One estimate values the semiconductor-used high-purity sputtering target materials market at about $780 million in 2023 and projects it could more than double over the next decade, driven by rising semiconductor output and demand from AI, IoT, and 5G. Another estimate puts the copper sputtering target market at roughly $1.4 billion in 2024, also expecting strong growth over the coming decade. You don’t need to believe any single forecast to see the direction: more wafers, more layers, tighter tolerances, and a broader mix of advanced materials.

This is where JX’s positioning becomes unusually powerful. With roughly 60% share in sputtering targets and a deep technical moat built around purity, structure control, and reliability, JX is set up to capture an outsized portion of the industry’s growth. In categories where qualification is painful and failure is expensive, a supplier with proven performance can often translate rising demand into not just more volume, but durable pricing and attractive profitability.

The other bull factor is structural: independence. Post-IPO, JX can allocate capital like a focused technology materials business—pursuing capacity expansion, stepping up R&D, and potentially using acquisitions to deepen its position in adjacent “must-work” materials—without competing against ENEOS’s energy-transition spending priorities.

And the application driver behind all of this is still accelerating. IDC expects AI and high-performance computing to remain major growth engines, pushing more investment into advanced chips, leading-edge nodes, and the packaging ecosystem that surrounds them. If that holds, JX sits in a very rare place: a picks-and-shovels supplier to the most capital-intensive manufacturing buildout in the world.

Bear Case

The biggest risk is concentration. A small handful of top-tier customers—TSMC, Samsung, Intel—account for a significant share of the industry’s leading-edge output, and therefore a meaningful share of demand for the highest-end targets. If any of those relationships weaken, or if procurement strategies shift, the impact on JX could be material.

There’s also a broader industry dynamic worth taking seriously: even in a boom, value doesn’t spread evenly. While AI is driving massive investment, the economic gains can concentrate among a relatively small group of winners. Some analyses argue that most of the industry’s economic profit has been captured by a thin slice of players, while the long tail sees squeezed returns. If that pressure pushes customers to become more aggressive on pricing, dual-source more intensely, or vertically integrate certain materials, it can create headwinds even for a category leader.

Geopolitics is another overhang. Semiconductor supply chains have become a front line in US–China tensions. Export controls, tariff regimes, and national industrial policies can reshape customer footprints, qualification decisions, and cross-border flows of critical materials—often quickly, and not always rationally from a pure business standpoint.

Then there’s input cost risk. JX sells precision-engineered products, but it still lives in a metals universe. Volatility in raw materials like tantalum and titanium can pressure margins, especially when price moves faster than contractual pass-through mechanisms.

Competition, particularly from China, is the slow-burn threat. Today, many competitors still lack JX’s process depth and qualification history at the high end. But sustained investment—plus the strategic importance of semiconductor self-sufficiency—means capability gaps can narrow over time.

Finally, cyclicality never disappears. Even if the “giga cycle” narrative proves directionally right, the semiconductor industry is still prone to corrections. If capex pauses, inventories build, or demand normalizes faster than expected, volumes can fall and pricing pressure can rise. In that scenario, JX’s results could weaken even if its long-term moat remains intact.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For ongoing monitoring of JX Advanced Metals, investors should track:

-

Semiconductor Materials Segment Operating Margin: A simple proxy for whether the moat is holding in the place that matters most. Expansion suggests pricing power and/or improving efficiency; compression can signal competitive pressure or input-cost drag.

-

Sputtering Target Volume Growth vs. Industry Wafer Starts: A practical way to monitor share and embedment. Over time, a leader like JX should roughly track, and ideally outperform, the underlying growth in semiconductor production.

-

R&D Intensity (R&D Spend / Semiconductor Materials Revenue): This is a technology business disguised as a metals business. Sustained investment in purification, new materials, and process control is what keeps customers qualified and competitors behind. A meaningful decline can be an early warning sign.

Together, these measures triangulate the core question for the stock: is JX converting its technical position into durable economics—and investing enough to keep that position as the industry evolves?

Conclusion

From a copper mine in rural Japan in 1905 to the invisible backbone of the global semiconductor supply chain, JX Advanced Metals is industrial evolution in its cleanest form. The company Fusanosuke Kuhara built by mechanizing mining and mastering smelting didn’t just survive Japan’s last century of upheaval. It learned, compounding process control until “metals” stopped being a commodity story and became a precision story—products measured in purity, microstructure, and atoms.

The March 2025 IPO isn’t a victory lap. It’s the moment the company’s incentives finally match its reality. For the first time in decades, JX Advanced Metals can be run and valued as what it actually is: a technology materials business. Decisions about capacity, R&D, and acquisitions no longer have to compete with the priorities of an oil refiner navigating secular decline and the energy transition.

The investment thesis is simple. As semiconductor manufacturing expands—pulled forward by AI, data centers, and ever more demanding devices—the suppliers of qualified, hard-to-replace materials become increasingly important. JX sits in a rare position: roughly 60% share in sputtering targets, earned over decades and reinforced by the harshest moat in this industry—long qualification cycles and brutal switching costs. Vertical integration and metallurgy know-how aren’t marketing lines here; they’re why fabs trust the material.

None of this makes the business risk-free. A handful of customers matter enormously. Geopolitics can reshape supply chains faster than engineers would like. China is investing to close capability gaps. And semiconductors still cycle, even in an AI-led buildout.

But zoom out and the shape of the story is hard to miss. Every advanced processor, every cutting-edge memory device, every AI accelerator still depends on thin films deposited with materials that have to work perfectly, every time. JX has spent more than a century building the capability to deliver that reliability.

One hundred twenty years from mine to microchip. That’s the JX Advanced Metals story—and now, as a standalone company, it’s finally positioned to write the next chapter on purpose.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music