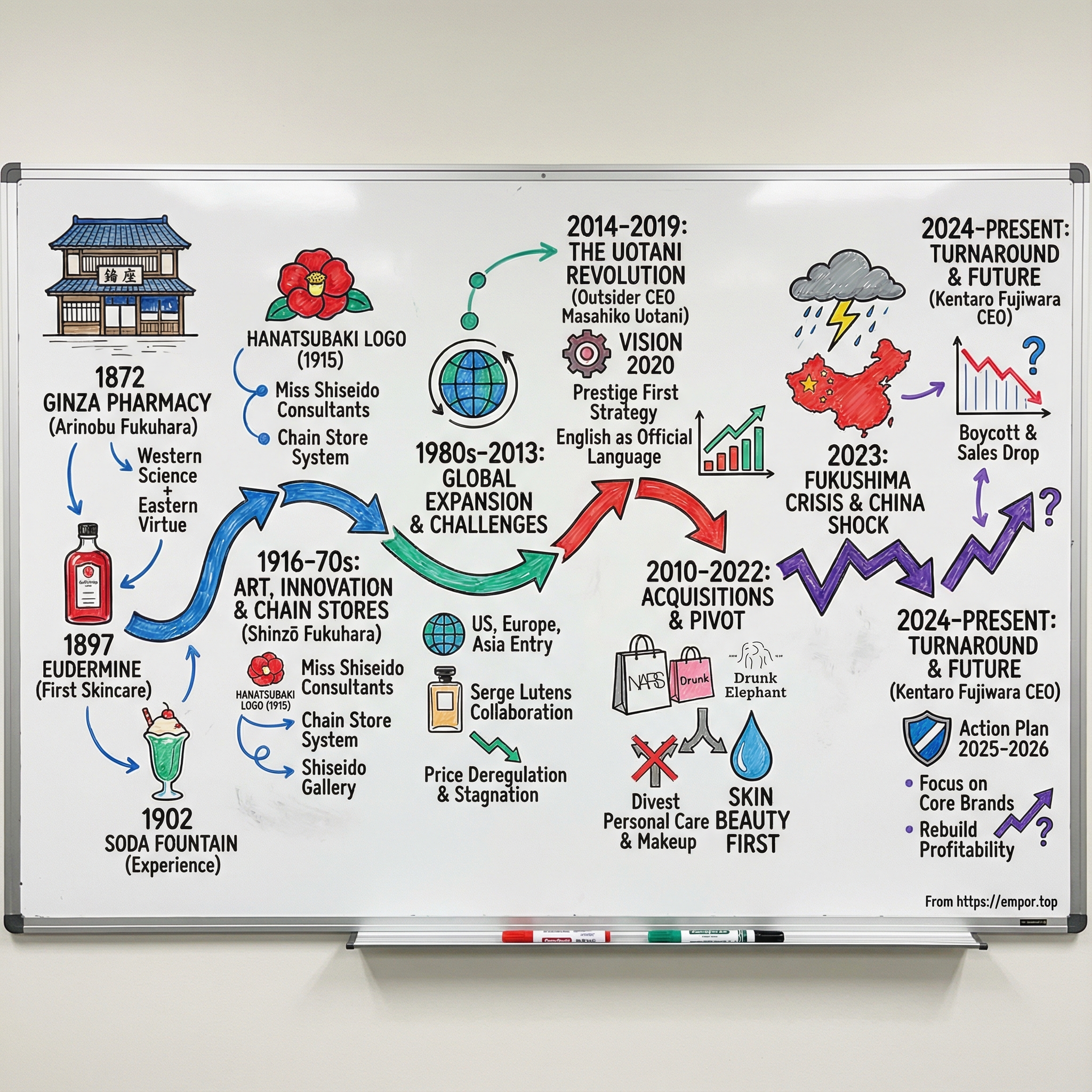

Shiseido: The 150-Year Journey of the World's Oldest Cosmetics Company

I. Introduction: From Ginza Pharmacy to Global Beauty Empire

In the autumn of 2014, something unheard of happened inside the boardrooms of one of Tokyo’s most iconic companies. Shiseido—an institution so steeped in tradition it had always promoted from within—picked an outsider to lead it.

Masahiko Uotani, fresh off a run as CEO of Coca-Cola Japan, was just as stunned as everyone else when the call came. In 150 years, Shiseido had never gone outside the company for its top job. And yet here it was, asking a career multinational executive to take the reins of Japan’s biggest beauty house.

When Uotani became president and CEO in 2014, he didn’t just inherit a portfolio of storied brands. He inherited a mandate. His mission was to remake Shiseido from a Japanese company that happened to sell around the world into a truly global enterprise—still headquartered in Tokyo, but shaped by the speed, diversity, and competitive intensity of the markets it served.

By the time Shiseido marked its 150th anniversary in 2022, it could credibly claim a rare kind of longevity: one of the world’s oldest cosmetics companies, Japan’s largest, and the fifth largest globally. Its skincare, makeup, and fragrances reached consumers in roughly 120 countries. But the leap from a single pharmacy counter in Ginza to a sprawling beauty conglomerate wasn’t a straight line. It was a century-and-a-half of reinvention—through wars, economic shocks, changing tastes, and relentless global competition.

That’s the question at the heart of this story: how did a 19th-century Japanese pharmacy survive all of that to become a modern beauty powerhouse—and what does the company’s latest inflection point mean for its future?

As Uotani put it: “I thought that a company as traditional as Shiseido hiring an outsider for the first time was a big symbol of change in Japan. I knew it wasn't going to be easy, but I felt Shiseido could become more global to be more successful and could act as a showcase to other Japanese companies. That was what motivated me to take the risk.”

That risk—and everything that followed—defines modern Shiseido. From its Meiji-era beginnings, to a global prestige portfolio, to the high-flying acquisition years, to the Fukushima-linked China shock, and now a turnaround under new leadership, this is the story of heritage colliding with disruption in the business of beauty.

II. Founding & The Meiji Era: Japan's First Western Pharmacy (1872–1916)

Picture Tokyo’s Ginza in September 1872. Japan had just emerged from more than two centuries of isolation, and the Meiji Restoration was in full swing—an era of modernization where “Western” suddenly meant “the future.” Into that swirl of change walked Arinobu Fukuhara, a pharmacist with a rare combination of credentials: roots in traditional Eastern medicine, and training in Western science.

On September 17, 1872, Fukuhara opened Shiseido in Ginza as Japan’s first private Western-style pharmacy. He wasn’t just selling different products; he was introducing a different system—helping establish Japan’s first separation between medical diagnosis and the dispensing of medicine. After serving as chief pharmacist in the Imperial Japanese Navy, he’d seen both the promise of modern pharmacology and the gaps in quality and practice back home. Shiseido was his attempt to raise the standard.

Even the name carried ambition. “Shiseido” comes from the Yi Jing (Book of Changes), commonly interpreted as: “How wonderful is the virtue of the earth, from which all things are born!” In other words: create new value, grounded in nature, that improves everyday life. From the very beginning, the company’s identity was a blend—Western science in service of an Eastern worldview.

That blend showed up in Shiseido’s first breakout innovation. In 1888, Fukuhara introduced a sanitary toothpaste in cake form, replacing the abrasive tooth powders people were used to. It was dramatically more expensive—about eight times the price of ordinary toothpaste—but it was cleaner, more pleasant to use, and quickly caught on. More importantly, it proved that consumers would pay for quality, efficacy, and experience. That lesson would pull Shiseido steadily from medicine toward beauty.

The true pivot arrived in 1897 with Eudermine, Shiseido’s first skincare product. Compared with the medicinal treatments women had been using, Eudermine felt like a new category: a striking, well-designed bottle; a ruby-red liquid; results that spoke for themselves. The name came from Greek—“eu” for good, “derma” for skin—and it marked Shiseido’s transformation from a pharmacy that sold useful goods into a company that could define modern beauty. And Eudermine didn’t just succeed then. It’s still made today, more than 125 years later.

Fukuhara was explicit about what he thought he was building. “Beauty is universal,” he said, “thus the products which serve beauty should also be universal.” It’s a line that reads like a mission statement—and for Shiseido, it became one.

But Fukuhara wasn’t only a product innovator. He was a student of culture. He traveled to the U.S. and Europe to see what modern life looked like up close, and one small detail jumped out at him: American drugstores often had soda fountains. So in 1902, he brought the first one to Japan, installed it in his Ginza pharmacy, and started serving ice cream sodas in imported dishes and glasses.

It sounds like a quirky side hustle. In reality, it was another expression of the same idea: beauty wasn’t separate from lifestyle. The soda fountain turned Shiseido into a destination. People came for a taste of the modern world—and left with a new relationship to the brand. That single fountain grew into the Shiseido Parlour, which still exists today across restaurants, cafés, and food and beverage shops.

Long before Shiseido became a global beauty powerhouse, Fukuhara had already figured out the playbook: take the best of global innovation, adapt it for Japanese customers, and wrap it in an experience people want to return to. By the early 1900s, Shiseido was no longer just a shop in Ginza. It was becoming a cultural institution.

III. Building a Beauty Empire: Art, Innovation & The Chain Store System (1916–1970s)

When Arinobu Fukuhara handed the company to his son, Shinzō, in 1913, he didn’t just pass down a business. He passed down a philosophy—and the freedom to evolve it. Arinobu had brought Western science to Ginza. Shinzō would bring something else: art, design, and modern brand-making.

Fresh from years abroad, including studying pharmacology at Columbia University in New York, Shinzō came back with a conviction that Shiseido shouldn’t merely sell products. It should create a world people wanted to step into. He set up the company’s first laboratory and its design function, and he poured energy into a visual identity that would make Shiseido instantly recognizable. In 1915, the company chose the hanatsubaki—camellia—as its trademark, with Shinzō, a respected photographer in his own right, designing the emblem that would become Shiseido’s signature.

The business followed the brand. In 1916, Shiseido split out its cosmetics operations into a dedicated business and opened a standalone cosmetics shop—an early sign that beauty was no longer just an extension of the pharmacy. Then, in 1917, Shiseido launched Hanatsubaki, a fragrance notable for a simple but powerful reason: it was the first scent created, marketed, and sold in Japan by a Japanese company. Shiseido wasn’t importing modernity anymore. It was producing it.

Over the 1920s and 1930s, the company’s real innovation wasn’t confined to bottles and formulas. It was in how Shiseido went to market. Instead of relying on generic retailers, Shiseido built what became the Shiseido Cosmetics Chain Store System—partnering with shops across Japan and turning distribution into a disciplined, relationship-driven network. This wasn’t just about getting product onto shelves. It was about creating a consistent Shiseido experience, storefront by storefront.

That idea reached its clearest expression in 1934, when Shiseido launched the Miss Shiseido program. From 240 applicants, the company selected nine women to become trained beauty consultants—public-facing experts who could teach, advise, and elevate the brand in person. The training was intense and unusually broad for the time: cosmetic science, dermatology, makeup artistry, public speaking, and even singing and etiquette. In an era when professional pathways for Japanese women were narrow, Shiseido offered something rare: a serious education and a visible, respected role. Miss Shiseido didn’t just sell cosmetics. They built trust—and they turned customers into loyalists.

Three years later, Shiseido added a second engine for loyalty: the Hanatsubaki-kai, or Camellia Club. Launched in 1937, it deepened the company’s direct connection with customers through communications, beauty seminars, and mail-order sales. Long before “CRM” was a term, Shiseido was systematically learning how to stay close to its customers, even when they weren’t in the store.

Shiseido was also formalizing itself as a modern corporation. In 1927, the business was incorporated as Shiseido Co., Ltd., with Shinzō as its first president. In 1928, Shiseido introduced its Western logo, and the Shiseido Parlour reopened—again becoming a sensation, this time by serving Western-style food on silver dishes. Just like the original soda fountain decades earlier, it wasn’t a distraction. It was the point: Shiseido was selling an idea of modern life.

And Shiseido wasn’t shy about placing itself in Japan’s cultural bloodstream. In 1919, it established the Shiseido Gallery—now the oldest existing art gallery in Japan. Shinzō’s love of avant-garde art and photography wasn’t a side interest; it shaped everything from advertising to packaging and positioned Shiseido as a tastemaker, not simply a manufacturer.

Underneath all of that artistry was serious science. In 1939, Shiseido completed its first standalone research and development laboratory, reinforcing that its aesthetic edge would be backed by formulation expertise—an advantage that would matter even more as competition rose.

Then the war came and the story snapped into survival mode. During World War II, Shiseido stopped producing cosmetics and shifted to daily necessities. When the conflict ended, the company restarted where it could: one of its first post-war launches was a red nail enamel called Tsumabeni. And in 1951, De Luxe—its premium cosmetics line that had been halted during the war—returned as Japan’s economy began to recover and consumers started reaching again for small luxuries.

By the late 1940s, Shiseido was also stepping into a new kind of scrutiny—and opportunity. In 1949, its shares were listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange for the first time, bringing public accountability and access to growth capital.

The post-war decades set up the next leap: overseas expansion. Shiseido established subsidiaries in the United States in 1965 and Italy in 1968, followed by France, Germany, and China in 1980. The company was leaving Japan in earnest—but true globalization would take more than opening offices. That deeper transformation wouldn’t arrive for another generation.

IV. Global Expansion & The Fukuhara Dynasty (1980s–2013)

By 1980, Shiseido had spent decades building science, craft, and distribution. What it still lacked—at least outside Japan—was a visual language powerful enough to travel.

So it did something telling: it hired a French image-maker named Serge Lutens.

Lutens wasn’t brought in to tweak a logo. He was brought in to help reinvent how Shiseido looked and felt to the world. Over the next decade, he designed packaging and cosmetics, photographed award-winning campaigns, and helped give Shiseido a distinctly modern, prestige aura that read as both Japanese and unmistakably global.

Shiseido also gave Lutens a major platform in fragrance. In 1982, the company commissioned Nombre Noir. In 1992 came Feminite du Bois—another landmark release. And for the most exclusive expression of this partnership, Lutens conceptualized Les Salons du Palais Royal, a luxurious perfume house created specifically to showcase Shiseido and Lutens scents.

The result was more than a few hit products. It was a French-Japanese aesthetic fusion that became central to Shiseido’s prestige positioning—a bridge between Eastern sensibility and Western sophistication that competitors couldn’t easily copy.

While the brand was sharpening its global image, the family leadership was also tightening the machine. In the late 1980s, Shiseido undertook a three-year reorganization led by President and CEO Yoshiharu Fukuhara, a grandson of the founder. The goal was operational: strengthen the sales network, modernize the organization, and protect Shiseido’s long-held leadership in Japan.

In 1989, Shiseido tried to put language to what it was becoming. It formally set down its “Corporate Ideals,” asking a deceptively simple question: “How, and through what means, should Shiseido be of use to the world?” With consumer lifestyles growing more complex, Shiseido’s answer was to broaden its mission into a “life science” approach—linking beauty and health, and positioning the company as a steward of lifestyle, not just cosmetics.

Then came the shock that hit almost every incumbent consumer brand in Japan: price deregulation. Starting in 1991, Shiseido began losing the retail-level pricing control its model had long relied on. Discount chains spread. Price competition intensified. Revenues and profits came under pressure—made worse by the broader economic stagnation of Japan’s “lost decades.”

The home market, once Shiseido’s anchor, became its weight. By the early 2010s, Shiseido had a deep portfolio—brands like Elixir and Clé de Peau Beauté among them—but growth was elusive. Investment in marketing and R&D had been reduced over time, which weakened brand equity, hurt store sales as consumer purchasing slowed, and created a grim feedback loop: lower demand led to slower shipments, which led to deteriorating profitability, which made it harder to invest for recovery. Even when overseas sales expanded, Japan’s long slide kept the overall company from truly growing. Reigniting Japan wasn’t optional; it was urgent.

By that point, Shiseido looked like an industry laggard—especially at home—with nearly flat growth. And the board reached a conclusion that would have been unthinkable for most of the company’s 142-year history: the turnaround would require an outsider.

That decision set the stage for 2014—and for Masahiko Uotani walking into Shiseido with a mandate to remake it.

V. The Uotani Revolution: Hiring an Outsider CEO (2014–2019)

When Masahiko Uotani walked into Shiseido’s headquarters in 2014, he didn’t come in as a cosmetics lifer. He came in as a brand-builder.

He’d spent 19 years at Coca-Cola, including more than a decade at Coca-Cola Japan as chief marketing officer, then president, then chairman. Before that, he’d done marketing and management stints at Kraft Foods and Lion Dentifrice. He spoke fluent “consumer,” not just “corporate.” He’d studied English at Doshisha University in Kyoto, then earned an MBA in marketing from Columbia Business School.

And he had a very specific view of what he’d been hired to do.

Uotani liked to say his leadership philosophy was shaped in Dale Carnegie classes he took while at Columbia in the early 1980s. He was, by reputation, gregarious and direct—someone who believed you changed a company by changing what people did every day, not by publishing a glossy plan and hoping it stuck.

He built his Shiseido playbook around the company’s reality, then layered on lessons from Coca-Cola. “At the end of the day, Coke’s objective was to get people to smile and laugh—it’s not just a beverage to quench your thirst,” he said. “That is important to keep in mind.” He also pointed to what he’d learned about diversity and talent development: big global brands weren’t powered by org charts; they were powered by people—especially the ones closest to the customer.

In 2015, Uotani put a name on the transformation: VISION 2020, a medium-to-long-term strategy meant to keep Shiseido “vital for the next 100 years.” The headline ambition was to “Be a Global Winner with Our Heritage.” The way to get there was brutally clear: lean into prestige. Shiseido doubled down on high-end skincare, makeup, and fragrance—its Prestige First strategy—while investing in the less glamorous foundations that make a global business run: R&D, supply chain, digital, and IT.

Just as important, he changed how the company was organized. Shiseido moved to a global matrix that linked regions and brand categories, built around a “Think Global, Act Local” philosophy. Regional headquarters weren’t just execution arms anymore; they were given real responsibility and authority to win in their markets.

But the most radical changes weren’t in the strategy deck. They were cultural.

When Uotani arrived, he said there was only one woman on the management team. He pushed hard to change that. Over time, the board became far more gender-balanced, and leadership grew more international in its composition. His view was blunt: if Japanese companies wanted to compete globally, they needed different types of talent, not just more of the same.

Language became a forcing function. If you want people of different nationalities to work together, he believed, you can’t run the company in a way that silently excludes them. So in 2018, he worked to make English the common language at Shiseido headquarters. Management meetings would be conducted in English. Presentations would be in English. It was symbolic, yes—but also practical: it made “global” something you had to live, not just claim.

Even as he modernized Shiseido, Uotani insisted the company needed anchors—its non-negotiables. He described five strands of Shiseido DNA. At the top: Japanese aesthetic, as a true differentiator. Right alongside it: technology and science. “Whatever we do at Shiseido, it is always grounded in science,” he said. To him, this wasn’t just about winning market share. It was about what Shiseido should stand for: enriching people’s lives, not simply selling them products.

Then, unexpectedly fast, the results started showing up.

Shiseido surpassed one trillion yen in net sales in 2017—three years ahead of its VISION 2020 target. In 2018, operating profit rose past 100 billion yen, hitting another milestone ahead of schedule. That year, net sales climbed strongly, and operating profit jumped sharply as well, pushing Shiseido’s operating margin into double digits for the first time—reaching 10.1% and clearing the company’s 10% target early.

Uotani credited not just the plan, but the selling of the plan. He went back to that Dale Carnegie instinct: persuasion isn’t a memo; it’s a thousand conversations. “In order to get there, I had to communicate why I came up with this idea,” he said. “I spoke to everyone. I went to the front lines, talking to beauty advisors… You can’t just show up and go, ‘Hi, I’m your CEO and can you tell me about the strategic issues we’re facing.’”

By the end of the decade, he’d delivered what the board hired him to do: Shiseido wasn’t just a venerable Japanese company with overseas sales. It looked and operated far more like the global prestige group it aspired to be—sharper in its focus, more modern in its culture, and newly relevant to a younger generation through an emphasis on beauty tied to health and wellbeing.

And that set up the next chapter: once you’ve rebuilt the engine, the temptation is to step on the gas.

VI. The Acquisition Era: NARS, Drunk Elephant & Portfolio Building (2010–2021)

In the second half of the 2010s, Shiseido started to look less like a venerable Japanese incumbent and more like a modern prestige roll-up. The VISION 2020 plan was working, profits were up, and Uotani had momentum. So he did what many newly confident CEOs do: he went shopping—using acquisitions to plug portfolio holes fast, especially in the U.S.

Some of those bets came earlier. In 2010, Shiseido took Bare Escentuals private for $1.7 billion, gaining bareMinerals and a direct line into the American prestige makeup customer. Then in 2016, it added Laura Mercier and Buxom for $248 million—more bets on the same thesis: U.S. prestige makeup was where the growth and influence were.

Years later, Shiseido would reverse course. In August 2021, it announced it would transfer bareMinerals, BUXOM, and Laura Mercier to a company owned by private-equity firm Advent International. Advent paid $700 million—far below what Shiseido had paid to assemble the trio. That gap is the clearest signal of how much the market had shifted, and how much those “strategic” assets no longer fit the company Shiseido was becoming.

But the defining deal of the era didn’t come from makeup. It came from “clean” skincare.

In October 2019, Shiseido announced it would acquire Drunk Elephant for $845 million, at a valuation of 8.5 times sales. It was a loud statement of intent: Shiseido wanted a meaningful position in a fast-growing segment where it didn’t have one. Marc Rey, then CEO of Shiseido Americas, framed it plainly at the time—the clean beauty market was expanding quickly, and Shiseido was missing it.

Drunk Elephant had the kind of brand story acquirers love. Founded in 2012 by Tiffany Masterson, it built a following around what it called the “suspicious six,” avoiding ingredients like essential oils, drying alcohols, silicones, chemical sunscreens, fragrance and dyes, and Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS). It rode the clean beauty wave with playful marketing and products that felt premium but accessible. Uotani called it “one of the fastest-growing prestige skincare brands in history.”

Then came the hangover. On Monday, Shiseido published its first quarter 2025 earnings and disclosed that sales at Drunk Elephant had fallen 65 percent. The same brand that had once embodied Shiseido’s bid for relevance with younger consumers had become a very public problem—one that would haunt the company’s strategy and leadership decisions in the years ahead.

Not all of Shiseido’s buying was about brands. It also made smaller, tactical moves to upgrade its capabilities. In January 2017, Shiseido acquired MATCHCo, a Palo Alto-based digital startup often described as “AI for beauty,” built around skin-matching technology that helped consumers find the right foundation shade using a smartphone camera.

Shiseido also tightened its grip on the prestige image it had built over decades. Having partnered with Serge Lutens since 1980, the company moved to purchase the Serge Lutens brand outright. Shiseido’s rationale was that ownership was the best way to preserve and promote the brand’s concept, “Rare and Lux,” while continuing to build on Lutens’ distinctive creative legacy.

By the end of this period, Shiseido’s portfolio looked like a global prestige group’s toolkit: its core Japanese heritage brands like Shiseido, Clé de Peau Beauté, and Elixir; Western prestige names including NARS and Drunk Elephant; and fragrance houses like Issey Miyake, Narciso Rodriguez, and Serge Lutens.

And even after the big divestitures, the company kept refining the mix. In December 2023, Shiseido announced it would acquire Dr. Dennis Gross Skincare, strengthening its medical-aesthetic skincare portfolio—an emphasis on clinical credibility that, in hindsight, also looked like a hedge as Drunk Elephant started showing real signs of strain.

Shiseido had assembled an impressive collection. The harder question was the one that comes after every acquisition spree: could it manage all of this as one coherent company—and would the pieces still make sense when the market turned?

VII. The Strategic Pivot: Divestitures & "Skin Beauty First" (2020–2022)

Then COVID hit—and the rules of the game changed overnight.

Through 2020, the pandemic didn’t just disrupt sales. It exposed the pressure points in Shiseido’s model. Consumer priorities shifted, traffic disappeared, and a business built on high fixed costs—justified by high gross margins—suddenly looked far less forgiving. Shiseido responded by taking a hard look at what had become structural issues: improving profitability in the Americas and EMEA, reducing reliance on inbound tourism in Japan, and rebuilding the cost base for a world where demand could swing violently.

In that sense, COVID became less a temporary shock and more a catalyst. Shiseido announced a broader ambition to become a “personal beauty and wellness” company, and that meant reshaping the portfolio—selling what no longer fit, and concentrating resources where the company believed it could win long-term.

The biggest signal came in 2021, when Shiseido began exiting its mass-market and personal care exposure. It sold its personal care business and mass-market brands to FineToday, a decisive step back toward what Shiseido wanted to be: a premium cosmetics and skincare company, not a broad consumer products conglomerate.

Then came the makeup reset.

Shiseido agreed to sell bareMinerals, Buxom, and Laura Mercier to Advent International, which formed a new vehicle for the deal. The transaction price—$700 million—was far below the roughly $2.1 billion Shiseido had paid to buy those brands in 2010 and 2016. On paper, it was a painful reversal. In management’s framing, it was the cost of focus: shedding slower-growth assets to free up capital and attention for categories with better tailwinds.

Masahiko Uotani put a diplomatic point on it: “While bareMinerals, Buxom and Laura Mercier have been a core part of our portfolio and have benefitted from Shiseido's stewardship to date, we believe Advent is uniquely positioned to continue supporting all three brands alongside their talented teams moving forward.”

Advent’s newly created New York-based Orveon ultimately acquired the three brands from Shiseido Americas. The deal was announced on August 25, 2021 and closed on December 6, 2021. With it came a real organizational shift: the brand teams moved over, along with about 350 employees in corporate support functions.

And makeup wasn’t the only divestiture. In 2021, Shiseido also sold its personal care business to a company held by British equity firm CVC Capital Partners—another move that tightened the company’s center of gravity around prestige.

All of this flowed into a new operating plan. Shiseido’s medium-term strategy, WIN 2023 (covering 2021 to 2023), was positioned as the first step toward its 2030 vision of becoming a “Personal Beauty Wellness Company.” WIN 2023 called for structural reforms aimed at reaching a 15% operating margin, along with continued portfolio restructuring to improve competitiveness and resilience.

But the takeaway was simpler than any strategy name: Shiseido was choosing skin beauty over makeup.

Uotani set an explicit target—by 2023, he wanted about 80% of sales to come from skincare, up from roughly 60% at the time. The bet was that Shiseido’s heritage in skincare science, paired with premium positioning, would be more defensible than fighting for share in an increasingly crowded, trend-driven makeup market.

For a company that had just spent the late 2010s buying its way deeper into Western makeup, it was a clear pivot. And it set Shiseido up for the next phase of the story—because just as the portfolio was getting cleaner and more focused, a completely different shock was about to hit its most important market.

VIII. The Fukushima Crisis: Geopolitical Shockwave (2023)

In the summer of 2023, a crisis hit that would jolt Shiseido off course—and it had nothing to do with formulas, marketing, or execution.

It started with Fukushima.

As Japan prepared to release treated water from the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear plant, Chinese social media lit up with allegations—largely unproven—that the discharges were hazardous to health. A viral boycott campaign took shape almost overnight. Chinese users began compiling lists of Japanese brands to avoid, and on Weibo, a hashtag around the issue drew roughly 300 million views.

For Shiseido, this wasn’t a reputational headache in a small market. China was its biggest market, representing close to 30% of total sales. And investors immediately treated the boycott like a direct hit to earnings power. In the aftermath of the discharge news, Shiseido suffered its largest weekly stock drop in nearly 10 months: down 6.8% as of August 28.

The claims driving the boycott weren’t backed by evidence. Some observers flagged the backlash as a surge of Chinese nationalism. And the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency concluded that Japan’s plan was safe, saying the controlled, gradual discharge “would have a negligible radiological impact on people and the environment,” according to IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi.

None of that mattered in the moment. The boycott moved faster than any official reassurance.

Shiseido wasn’t alone. Kosé and Pola Orbis also reported negative growth in China tied to the issue. But Shiseido—because of its scale and its exposure—felt it most. After Japan began the discharge on August 24, and China responded by banning all Japanese seafood imports, the consumer backlash spread to Japanese personal care brands as well. In September, Shiseido’s online sales in China fell 32%, according to Chinese data groups Feigua and Moojing.

The episode echoed an earlier playbook: in 2012, a territorial dispute had already shown how quickly diplomatic tension could spill into consumer behavior. This time, Shiseido had even more at stake. Kentaro Fujiwara, then Shiseido’s president and COO, acknowledged the boycott’s impact on performance. By then, Shiseido’s share price had fallen about 20% since early June amid rising concern over China—at a time when China accounted for about 26% of Shiseido’s revenue.

Analysts at Mizuho Securities warned that fear of contamination could create permanent customer loss, even though Shiseido had no production sites near Fukushima and did not use seawater in its cosmetics production. The perception problem had detached from the operational reality.

Inside the company, leadership tried to project calm. Fujiwara said Shiseido viewed the setback as temporary: “We assume the reluctance to buy Japanese products after the release of the treated water will normalise by the first quarter of 2024. We will continue to closely monitor changes in the market environment.”

But the financial consequences forced action. Shiseido revised its core operating profit forecast sharply. In the third quarter, sales in both China and travel retail fell around 10% after the discharge began. The company curtailed marketing and suspended promotions—essentially choosing to wait out the storm rather than spend heavily into a hostile environment.

The deeper damage wasn’t just one bad quarter. It was what the crisis revealed.

Shiseido’s strategy had become increasingly dependent on two places where it had the least control: China, and travel retail. Japan was improving, but the company’s growth engine sat offshore. When geopolitics intervened, there was no lever to pull that could fix it quickly.

IX. The Drunk Elephant Hangover & Current Turnaround (2024–Present)

By the time Shiseido entered 2025, it wasn’t just dealing with a tough market. It was also changing captains.

Kentaro Fujiwara, who had been President and COO, was promoted to CEO effective January 1, 2025. He succeeded Masahiko Uotani, who retired at the end of December 2024 after nine years leading the group.

Uotani’s decade-long mission was clear from day one: take Japan’s largest beauty company and turn it from a Japanese firm that sold products worldwide into a global enterprise headquartered in Tokyo—one that actually reflected the dynamism and diversity of the markets it served. And he didn’t leave the handoff to chance. Shiseido described Fujiwara’s rise as the culmination of a carefully managed, five-year succession plan that began in 2019, with the two executives working closely to engineer what the company called a “successful leadership transition.”

Fujiwara was also not a stranger to the company’s most important pressure point: China. He became Chairman of the Board and President of Shiseido China in 2016, then moved up to China Region CEO and Senior Executive Officer in 2020. In November 2022, he was formally designated a CEO candidate and took on the President and COO role—essentially stepping into the operating cockpit while Uotani prepared to exit.

But the timing couldn’t have been harsher. Fujiwara inherited a company coming off a steep profit collapse.

For the year ending December 31, 2024, Shiseido posted operating profit of ¥7.58 billion, down from ¥28.13 billion the prior year—a 73.1% decline. Sales rose 1.8% on a reported basis, but slipped 1.3% organically versus 2023.

The drivers were exactly where you’d expect after 2023’s geopolitical shock: China and travel retail. Shiseido said China’s cosmetics market stayed in a prolonged downturn, pressured by weaker consumer spending, rising household savings, and worsening economic sentiment. Like-for-like, Shiseido’s China business declined 4.6% to ¥249.95 billion. The country’s housing market remained fragile and confidence low, and Hainan’s duty-free retail market continued to struggle.

Then there was Drunk Elephant—once the symbol of Shiseido’s move into modern, “clean” prestige skincare, now a very visible drag. In Shiseido’s FY2024 results, Drunk Elephant sales fell 25% amid intense competition. Shiseido put 2024 net sales for the brand at just over $135 million, and noted that consumer purchase recovery was slower than expected.

Inside Shiseido’s own reassessment, the critique was pointed: a “lack of targeting based on clear customer understanding,” “unclear brand values,” and a “lack of differentiation from competitors through breakthrough innovation.” The company said it remained committed to the brand, and that in 2025 it would focus on strengthening Drunk Elephant’s marketing and clarifying its target consumer base to drive a turnaround.

The consumer reality wasn’t helping. A weakening economic climate had teens—and their parents—trading down from products like the Protini peptide moisturiser, priced at $69. Even the founder’s role looked less stable: Puck News reported that Tiffany Masterson, who founded the brand in 2013, was stepping back from day-to-day duties as chief creative officer.

So Fujiwara’s first job wasn’t inspiring a new vision. It was stopping the bleeding—and rebuilding the structure underneath the brands.

Shiseido moved to cut costs and reset its operating base, including offering early retirement to about 1,500 employees as part of its business transformation plan, Mirai Shift Nippon 2025. It also planned structural reform costs exceeding ¥4 billion in Q3 2025 tied to office downsizing in the Americas. The Americas business, which recorded losses exceeding ¥10 billion in 2024, was described as making steady progress toward returning to profitability by 2026.

Strategically, Shiseido framed the response through “Action Plan 2025–2026,” announced in late November 2024, layered on top of its broader medium-term direction, “SHIFT 2025 and Beyond.” On November 29, Fujiwara laid out the agenda for the next two years: identify the brands that deepen customer ties, strengthen those brands, and re-examine the business structure so the company can operate with a more resilient, higher-profit model in a volatile world.

That brand focus was explicit. Shiseido narrowed attention to the “Core 3”—Shiseido, Clé de Peau Beauté, and NARS—and the “Next 5”: Anessa, Narciso Rodriguez, Issey Miyake, Elixir, and Drunk Elephant.

Not everything was going wrong. Japan, in particular, stood out. Shiseido’s net sales in Japan grew 10%, and the company expected similar growth the following year, supported by tourist purchases. It also pointed to progress in Japan and Europe, where it said selection and concentration were producing a virtuous cycle of growth and improved profitability—an approach it aimed to expand globally to improve regional profit balance and establish a more durable earnings base.

In other words: Shiseido’s turnaround playbook under Fujiwara is not another acquisition spree. It’s the opposite—fewer bets, clearer brand roles, a tighter cost base, and a push to rebuild profitability in the places where the company had lost it.

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Competitive Position

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

Beauty has become one of the easiest major consumer categories to break into—and one of the hardest to truly win.

In the last decade, direct-to-consumer playbooks and social media have lowered the barrier dramatically. A new founder can contract out formulation and manufacturing, spin up a Shopify storefront, and build demand through TikTok, Instagram, and creator partnerships without ever touching a department store counter. Brands like Drunk Elephant (pre-acquisition) and Glossier proved that a sharp point of view plus digital distribution can outrun legacy advantages—at least long enough to matter.

But getting started isn’t the same as scaling. The moment a brand tries to move from internet momentum to durable global business—especially in physical retail—it runs into the old constraints again: working capital, inventory discipline, international distribution, regulatory know-how, and marketing budgets that can sustain attention after the algorithm moves on. That’s where incumbents like Shiseido still have real structural advantages.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW TO MEDIUM

On the supply side, cosmetics companies buy from a wide ecosystem: ingredients, packaging, and contract manufacturing. Much of it is relatively commoditized, which typically gives large brands negotiating leverage.

Shiseido’s scale adds to that advantage. Its supply network includes 13 production bases, with seven located outside Japan. That footprint lets it produce closer to demand, adjust to regional needs, and maintain the high-quality standards associated with Japanese manufacturing—while giving it more flexibility and bargaining power across suppliers than a smaller brand could ever match.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

If suppliers are fragmented, buyers are empowered.

Consumers have more choice than ever, and they’ve become far more informed. Reviews are instant. Ingredient breakdowns are searchable. Influencers can create a hit overnight—or kill momentum just as fast. Loyalty is thinner, experimentation is constant, and switching costs are basically zero.

Then there’s the channel power. Retailers like Sephora and Ulta aren’t just points of sale; they’re gatekeepers. Shelf space, end caps, sampling, and promotional placement all come with trade terms that brands have to accept if they want scale. And e-commerce only intensifies the dynamic: when every competing product is one click away, “I’ll try something else” becomes the default behavior.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

The underlying demand for beauty and self-improvement is durable. But what counts as “beauty” keeps changing—and that creates substitutes.

At one end, there’s skinimalism: fewer steps, fewer products, less consumption. At the other end, there’s the steady normalization of aesthetic procedures—injectables, lasers, and other in-office treatments that can replace what consumers once tried to solve with creams and serums. For premium skincare brands built on complex, multi-step routines, both trends can pressure growth, even if overall interest in looking and feeling good remains strong.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is where the fight gets brutal.

Shiseido competes with global giants like L'Oréal, The Estée Lauder Companies, Procter & Gamble (P&G), Unilever, and Kao. These companies have massive budgets, deep distribution, and the ability to place bets across every price point and channel.

L'Oréal is the archetype: broad portfolio, relentless marketing, heavy R&D, and increasingly sophisticated use of technology. It has also pushed further into adjacent categories, including moves tied to dermatology and aesthetics, and it has been actively integrating AI for personalization and content creation. Estée Lauder, meanwhile, has historically been one of the strongest operators in prestige skincare, makeup, fragrance, and hair care, powered by a curated set of luxury brands and deep appeal with high-end consumers.

And the last few years have shown how different strategies create different outcomes. Between 2021 and 2024, L'Oreal SA, The Estee Lauder Companies Inc. and Shiseido Company, Limited diverged meaningfully. L'Oréal strengthened its leadership with geographic balance and steady performance across channels, especially e-commerce and owned retail. Estée Lauder saw a sharp profitability hit in FY2023–24, exacerbated by heavy exposure to travel retail and Asia, which then triggered leadership changes and a greater push into digital channels. Shiseido, as we’ve seen, got caught in the same China-and-travel-retail crosswinds—without L’Oréal’s scale cushion to absorb the shock.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework: Shiseido's Competitive Advantages

Brand Power: Shiseido has strong brand equity in Japan and across much of Asia, where heritage can still command premium pricing. In Western markets, that power is weaker, and the brand often doesn’t carry the same cultural meaning.

Scale Economies: Shiseido benefits from scale in manufacturing and R&D, but it doesn’t have the overwhelming scale advantages of the very largest global players, particularly L'Oréal.

Network Effects: Absent. Cosmetics isn’t a platform business.

Counter-Positioning: In theory, Shiseido’s Japanese aesthetic and skin-science identity could stand apart from Western competitors. In practice, it has been difficult to translate that differentiation consistently outside Asia.

Switching Costs: Very low. Consumers can substitute products easily.

Cornered Resources: This is a real strength: 150 years of heritage, cultural assets, and deep skincare research capabilities that competitors can’t recreate quickly, if at all.

Process Power: Shiseido’s manufacturing discipline and quality standards provide process advantages, though the gap has narrowed as global manufacturing capabilities have improved.

Key KPIs for Tracking Shiseido's Performance

For investors monitoring Shiseido’s turnaround, three metrics matter most:

-

China and Travel Retail Revenue Growth: These segments have been the biggest drivers of volatility. If they stabilize and return to growth, it’s the clearest sign that external pressure is easing and execution can start to show through.

-

Core Operating Profit Margin by Region: The turnaround is ultimately a profitability story. Region-by-region margin improvement is the cleanest way to see whether structural reforms are working, especially in the Americas, where performance has been weakest.

-

Core Brand Growth Rate (Shiseido, Clé de Peau Beauté, NARS): These are the foundation. Their organic growth rate, excluding currency effects, shows whether Shiseido’s focus on fewer, stronger bets is actually translating into durable demand.

XI. Bull Case, Bear Case & Investment Considerations

The Bull Case

The optimistic case for Shiseido is that the company is finally getting its footing again—starting at home.

First, Japan has become a genuine bright spot. The domestic business delivered about 10% growth for two consecutive years as the post-COVID recovery matured, and it exceeded its profit targets. In a period when China and travel retail have been anything but predictable, Japan has started to look like the stabilizer Shiseido can build from.

Second, the structural reforms appear to be translating into real operating leverage, at least in Japan. The company delivered ¥28.1 billion in core operating profit there—well above its 2024 target of ¥20 billion-plus—and positioned that performance as a stepping stone toward ¥50 billion in 2025. If that trajectory holds, it would be proof that “selection and concentration” isn’t just a slogan; it’s a working operating model.

Third, the argument goes, China may be closer to the bottom than the top of the pain cycle. Shiseido reported sales increasing for the first time in five quarters, and the year-over-year decline in travel retail improved to a single-digit percentage. Management remained cautious about 2025, but the key point for the bull case is simple: conditions stopped deteriorating, and early signs of stabilization started to show.

Fourth, Shiseido still has real brand engines. Even with Drunk Elephant struggling, the core portfolio continued to resonate. In the first half of the year, NARS posted growth—up 7% in Q2 and 2% for the first half overall—and Clé de Peau Beauté grew 3% in both Q2 and the first half. For a group built on prestige, that matters: it suggests the “Core 3” can still pull demand even when the macro picture is messy.

Finally, the leadership transition lowers a classic turnaround risk: chaos at the top. Shiseido framed the shift from Uotani to Fujiwara as the result of a deliberate five-year succession plan, with both executives working closely to execute a controlled handoff. In the bull case, that planning buys the company time and focus—exactly what you need when the playbook is cost cuts, brand prioritization, and operational cleanup rather than growth at any cost.

The Bear Case

The bearish view starts with an uncomfortable conclusion: Shiseido is paying for a big strategic swing that didn’t work.

First, Drunk Elephant increasingly looks like a major acquisition mistake. After Shiseido bought the brand as a modern, fast-growing prestige skincare play, it ran into years of pressure—culminating in the brand losing momentum with the very young consumers who helped fuel its hype. The “Sephora teens” phase faded, and Drunk Elephant has been left trying to win back a clearer core customer.

At the same time, the turnaround is getting more tangible—and more painful—in the U.S. In a difficult first quarter, Shiseido began layoffs at its U.S. unit without disclosing specific figures. Internal communication described “a significant reduction in headcount affecting multiple businesses, functions and locations.” The near-term focus is blunt: fix U.S. commercial performance, reset Drunk Elephant, and concentrate resources on the most profitable brands.

Second, China remains the strategic vulnerability that won’t go away. Japan can grow, but China is still the most important overseas market—and geopolitics can still interrupt demand with little warning. Even without another boycott-style shock, rebuilding brand equity in mature, competitive markets is hard, especially as local Chinese brands keep getting stronger.

Third, competitive pressure is rising, not falling. Shiseido has been more exposed to Asia-Pacific, and it saw flat to declining revenue after 2022 as China’s recovery lagged and Japanese consumption weakened at different points. Meanwhile, L’Oréal extended its lead in scale and profitability. Estée Lauder and Shiseido both entered strategic reset phases—meaning they’re fighting on execution and efficiency while the category leader keeps compounding advantages.

Fourth, “turnaround mode” is itself a risk. It means the previous strategy didn’t deliver the intended results, and the fixes now require more action, more restructuring, and more time. Shiseido has acknowledged that both its 2024 performance and its 2025 outlook are not yet at the level it would expect for a long-term global beauty leader—implying that the gap still has to be closed through additional operational moves, not just a cyclical rebound.

Material Risks & Regulatory Considerations

Beyond the operating debate, there are practical risks investors have to price in.

Shiseido operates globally across regulatory regimes that govern ingredients, advertising claims, and manufacturing standards. On top of that, tariffs have re-emerged as a potential swing factor. Shiseido flagged increased global tariffs implemented by U.S. President Donald Trump in April as a “potential downside risk,” and said it was revisiting procurement sourcing, manufacturing footprint, and other countermeasures to reduce the impact of higher levies.

The company also reduced its dividend to support structural reform investments. After reviewing the situation, Shiseido decided to cut the year-end dividend for 2024, with CEO Fujiwara previously explaining the rationale.

Myth vs. Reality

Myth: Shiseido is a pure-play Japanese beauty company. Reality: The heritage is Japanese, but the business is global. Roughly 60% of revenue comes from outside Japan, making Shiseido a multinational that happens to be headquartered in Tokyo.

Myth: The Drunk Elephant acquisition was primarily about clean beauty. Reality: Clean beauty was part of the story, but the strategic logic was also about gaining scale and relevance in U.S. prestige skincare—an area where Shiseido lacked a major foothold.

Myth: The Fukushima water crisis was the primary cause of Shiseido's China problems. Reality: Fukushima accelerated and intensified trends that were already underway. China’s cosmetics market was cooling under domestic economic pressure, while competition from local brands had been rising for years.

XII. Conclusion: Heritage Meets Disruption

Shiseido is at a crossroads Arinobu Fukuhara could never have imagined when he opened a Western-style pharmacy in Ginza more than 150 years ago. The company he built on scientific rigor and a distinctly Japanese sense of beauty became a global prestige group. Now it’s fighting on multiple fronts at once.

Masahiko Uotani’s tenure proved Shiseido could change. In the span of a few years, it shifted from an insular Japanese institution into something that looked and operated far more like a modern global competitor. But the story of the 2020s has been less about momentum and more about exposure: COVID reshaped demand, travel retail stopped behaving like a dependable growth engine, and China—so central to Shiseido’s recent success—became a source of volatility.

What hasn’t changed is Shiseido’s most unusual advantage: heritage that still means something. A century and a half of continuous operation. Deep skin-science credibility. And a cultural identity that resonates across Asia in a way few Western companies can replicate.

But heritage doesn’t fix everything. It doesn’t solve an $845 million acquisition that has lost its spark. It doesn’t neutralize geopolitics. And it doesn’t make the competitive landscape any kinder—especially with L’Oréal continuing to widen the gap at the top of global beauty.

That’s why 2025 matters. Under the “Action Plan 2025–2026,” Shiseido is trying to do something unglamorous but essential: execute faster, tighten financial discipline, and build a business model that can keep producing profits even when the market turns against it.

The open question is whether Kentaro Fujiwara can make that real. He brings deep China experience and intimate knowledge of Shiseido’s operations—exactly what you’d want in this moment. The early signals in Japan have been encouraging. The signals in the Americas, especially around Drunk Elephant, have been far more troubling.

For investors, Shiseido is a bet on whether one of the world’s oldest beauty companies can translate what it has always had—trust, craft, and science—into what the modern market demands: sharp positioning, disciplined execution, and consistent global profitability.

In the end, Shiseido’s story has always been about the productive tension between tradition and transformation. Fukuhara’s original synthesis—Western science with Eastern aesthetics—created something enduring. Whether today’s leadership can pull off a new synthesis, one that bridges heritage and disruption, Asia and the West, skin-science credibility and brand desire, will determine whether Shiseido’s next 150 years live up to its first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music