Rakuten Group Inc.: Japan's Audacious Ecosystem Gamble

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

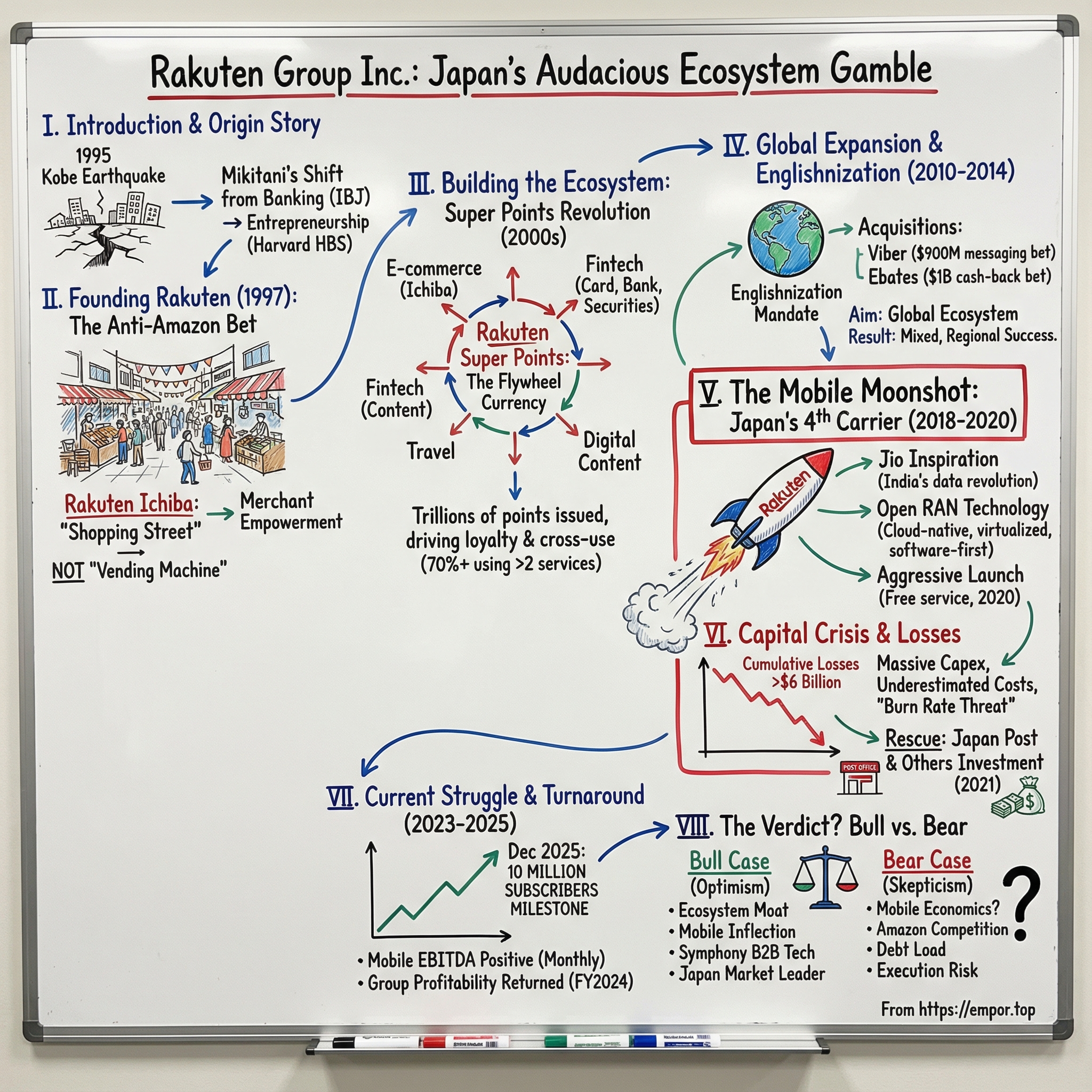

Picture this: one company that wants to be your online shopping mall, your bank, your credit card, your stockbroker, your insurance provider, your travel agent, your mobile carrier, and even your ticket into pro sports. And it wants all of it stitched together by a single loyalty currency: points that don’t just discount a purchase, but quietly nudge where you shop, how you pay, and what you try next.

That company is Rakuten Group Inc. It runs an ecosystem of more than 70 services across e-commerce, fintech, digital content, and communications, and it reaches more than 1.2 billion members worldwide. It’s also one of the boldest—and most controversial—“everything app” experiments ever attempted by a company outside China.

In the U.S., Rakuten often gets called “the Amazon of Japan.” It’s a useful shortcut, but it misses the plot. Amazon is a retailer that expanded into logistics and cloud computing. Rakuten was built as the opposite of a retailer: not a single store, but a shopping street. Mikitani once compared Amazon to “a vending machine; a hyper-efficient supermarket with standardized offerings,” while Rakuten is a bazaar “where the owners of many small shops curate the merchandise and interact personally with customers.” Amazon tends to pull merchants toward Amazon’s brand. Rakuten set out to push power back to merchants—letting them keep their identity, their storefront, and their relationship with customers.

As of December 2025, Rakuten’s market cap sat around $12.94 billion, putting it roughly 1,610th globally. But that tidy number hides a violent ride: from internet darling to a company staggering under the weight of a telecom gamble—one that has racked up more than $6 billion in cumulative losses.

So that’s the question we’re really here to answer. Can one company build a true super-ecosystem spanning commerce, money, media, and mobile? Or did Rakuten’s mobile moonshot cross the line from visionary courage into an existential threat?

To get there, we’ll follow the story from the rubble of the 1995 Kobe earthquake that pushed a banker toward entrepreneurship, through the global acquisition spree that brought in Viber and Ebates, and into the grinding reality of becoming Japan’s fourth mobile carrier—culminating in the hard-won milestone of 10 million subscribers, achieved even as skeptics insisted the whole thing was doomed from the start.

II. The Founder's Origin Story: Tragedy, Banking, and Harvard

Rakuten doesn’t start with a killer product idea. It starts with a person: a future founder whose worldview was shaped by a rare mix of privilege, international exposure, and sudden loss—then sharpened inside Japan’s elite financial system and an American business school classroom.

A Pedigree of Achievement

Hiroshi Mikitani was born on March 11, 1965, and raised in Kobe, in Japan’s Hyōgo Prefecture. He would later become the founder and CEO of Rakuten, and he’s held a remarkably wide set of roles beyond the company: president of Crimson Group, chairman of the football club Vissel Kobe, chairman of the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, and a board member of Lyft.

His family background reads like a blueprint for ambition. His father, Ryōichi Mikitani, was a professor at Kobe University and served as Chairman of the Japan Society Of Monetary Economics. His mother, Setsuko, also graduated from Kobe University, worked for a trading company, and had attended elementary school in New York.

There’s also a thread of old-world lineage: through his paternal grandmother, Mikitani has said he’s descended from Honda Tadakatsu, one of the famed Four Heavenly Kings of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. His grandmother herself came from a noble family that had fallen on hard times, and she raised Mikitani’s father as a single mother while running a tobacco store.

And then there’s the more modern kind of inheritance: business. Mikitani’s grandfather was active in New York and was a co-founder of Minolta. Ryōichi became Japan’s first Fulbright Scholar to the United States and spent two years teaching at Yale University. From 1972 to 1974, the family lived in New Haven, Connecticut—giving Mikitani an early, unusual familiarity with American life and Western ways of thinking.

That matters because Mikitani didn’t grow up with a purely domestic lens. Long before Rakuten tried to go global, he had already been exposed to a broader world—and it stuck. It’s also where the nickname “Mickey” comes from, the version of himself he would present to the international business community later on.

The Banking Years and Harvard Awakening

Mikitani attended Hitotsubashi University, graduating in 1988 with a degree in commerce. He joined the Industrial Bank of Japan (later part of Mizuho Corporate Bank), one of the country’s most prestigious employers for ambitious graduates. He arrived as Japan’s bubble era was still casting its spell—when finance felt like the center of gravity in the economy, and the best path for a young high-achiever was to climb inside an institution and master the system.

But Mikitani also stepped outside of it. From 1991 to 1993, he took leave to attend Harvard Business School, graduating in 1993. The experience didn’t just add a credential; it gave him a new mental model for how companies could be built and led.

At Harvard, he began to seriously consider entrepreneurship. He later said it was in an HBS classroom that he first thought about starting his own company—and that without Harvard, he might never have taken that path. The case method exposed him to a different kind of decision-making: faster, more individual, more willing to challenge default assumptions than the consensus-driven corporate culture he knew in Japan. He came away with a toolkit for thinking like a builder, not just an operator.

The Earthquake That Changed Everything

Even then, ideas are cheap. What pushed Mikitani from “someday” to “now” was catastrophe.

In 1995, the Hanshin earthquake devastated Kobe—his hometown—and hit him with personal force. His family still lived there. He rushed back to search for a missing aunt and uncle, and found their bodies at a makeshift morgue in a local school. Later, he wrote about the experience in Harvard Business Review: “I realized in those days how tenuous our existence is.”

The earthquake didn’t just break buildings; it broke his certainty about what mattered. Mikitani has said the destruction made him want to help revitalize Japan’s economy. A safe, prestigious banking career suddenly felt like a spectator role in a country that needed rebuilding.

In 1996, at age 31, he left the Industrial Bank of Japan and founded an independent consulting firm called Crimson Group. It wasn’t Rakuten yet—but it was the first irreversible step away from the old path, and toward the company that would try to rewire how Japan shops, pays, and connects.

III. Founding Rakuten: The Anti-Amazon Bet (1997–2000)

The Birth of an Online Mall

When Mikitani decided to start an internet company in early 1997, Japan wasn’t exactly begging for e-commerce. The web was young. Shopping was physical, ritualized, and dominated by institutions that felt immovable: department stores, convenience store empires, and multilayered distribution channels that had been optimized for the pre-digital world.

Still, on February 7, 1997, Mikitani and three co-founders put up $250,000 of their own money and incorporated MDM, Inc. Less than three months later, on May 1, they launched Rakuten Ichiba—an online marketplace that opened with 13 shops and a team of six.

The concept wasn’t “we’re going to become a store.” It was “we’re going to become a place where stores can exist.” Mikitani pictured a hybrid of eBay and Amazon.com: a marketplace built around exchange between buyers and sellers, not a single retailer controlling the shelf.

Two years later, in 1999, the company took the name Rakuten. And in 2000, Mikitani took it public on JASDAQ—turning what began as a tiny online mall into a newly public internet bet.

The name wasn’t just branding. Rakuten means “optimism.” In the middle of Japan’s lost decade, it was a statement of intent: a company built on the idea that the country’s future would be brighter, more connected, and more entrepreneurial than its present.

The B2B2C Philosophy—A Deliberate Contrast

From the start, Rakuten’s model was a deliberate rejection of the path the big American players were taking.

Mikitani’s big idea wasn’t logistics. It was empowerment. He wanted small and regional merchants—exactly the businesses most threatened by consolidation—to be able to compete online without giving up their identity. Compared with the clunky “internet malls” run by large corporations at the time, Rakuten offered lower fees, and, more importantly, control: merchants could shape their storefronts and talk directly to customers.

Rakuten even built an internal education program, Rakuten University, to teach shop owners how to succeed online. The message wasn’t “plug into our machine.” It was “we’re your partner.”

In Mikitani’s own framing, Rakuten was a bazaar where shopkeepers curate, explain, and build trust—rather than a standardized, efficiency-first catalog. Early on, merchants paid about $650 per month to set up shop, and they weren’t forced into a rigid template. Mikitani later said Rakuten encouraged merchants to tell personal stories and interact with shoppers because the stores that built a human connection tended to thrive.

That founding choice shaped everything that came after. Amazon would become history’s most efficient retail and logistics engine, pushing hard toward standardization and control. Rakuten bet that Japanese consumers would value relationship, curation, and individuality—and that merchants would fight harder for a platform that treated them like businesses, not inventory suppliers.

In certain categories, it worked extraordinarily well. Rakuten merchants went on to sell more than 10% of all wine sold in Japan, along with everything from food and clothing to art, cars, and even houses. The platform’s looseness wasn’t a bug; it matched a local sensibility that appreciated the character of each shop and the story behind what it sold.

IPO and Ambitious Targets

On April 19, 2000, Rakuten went public on JASDAQ. The timing, in hindsight, was flawless: the dotcom boom was still cresting, and investors wanted exposure to Japan’s internet future. The IPO didn’t just bring in capital—it legitimized Mikitani’s model at the moment it mattered most.

And Mikitani didn’t go public quietly. Even then, he was already doing what would become a trademark: setting huge targets well ahead of current reality—ambition big enough to energize the team, and bold enough to make skeptics roll their eyes.

The key takeaway from this era isn’t that Rakuten “did e-commerce early.” It’s that Rakuten picked a different business model on purpose. It chose merchant empowerment over tight control—accepting lower take rates and a messier customer experience in exchange for loyalty, variety, and a platform that could expand into an ecosystem. That would become a major advantage as Rakuten broadened beyond shopping. It would also become a constraint once Amazon pushed harder into Japan with its ruthless, integrated playbook.

IV. Building the Ecosystem: The Super Points Revolution (2000–2010)

The Loyalty Currency That Changed Everything

If one invention explains why Rakuten could keep standing toe-to-toe with bigger, better-capitalized rivals, it’s this: Rakuten Super Points.

On paper, it launched in 2002 as a simple loyalty program. In reality, it became the connective tissue for everything Rakuten wanted to become: not a single service, but a daily habit. A rewards program that quietly turned into a currency—and then into a moat.

Rakuten has issued trillions of points since the early days of the program. By 2024, the total issued had climbed to over 4 trillion. Each point is worth one yen, and the important part isn’t the accounting—it’s the feeling. Points don’t read like “discounts.” They read like money you already own. And Rakuten worked hard to make sure you could use that “money” almost anywhere inside its world.

Most loyalty programs trap you. Earn here, spend here. Rakuten did the opposite. You could earn points on Rakuten Ichiba, pick up more through Rakuten Travel, stack them through other Rakuten services, and then spend them across the ecosystem without worrying about where they came from. There were no artificial walls—just a single balance that followed you around.

And Rakuten didn’t stop at online checkout screens. With Rakuten Pay, those points became usable in the physical world too—at convenience stores, supermarkets, and a broad swath of everyday merchants. The result was that Rakuten Points started behaving less like “rewards” and more like cash within Japan’s consumer economy, accepted at millions of locations.

The Flywheel Effect

This is where the ecosystem strategy stops being a slogan and starts being a machine.

Every new Rakuten service could plug into an existing points economy on day one. That meant cheaper customer acquisition, faster adoption, and a built-in reason for customers to try something new. Meanwhile, each new service gave people more ways to earn and spend points, which pulled them deeper into Rakuten’s orbit.

You can see the flywheel show up in behavior. The share of shoppers using more than two Rakuten services rose from 64.9% in 2017 to 72.3% in 2019, a clear signal that once customers joined, they tended to broaden their relationship with the company.

Rakuten then added boosters like the Super Point Up program, which increases the points you earn on Rakuten Ichiba based on how many other Rakuten services you use. It’s a simple psychological trick with outsized impact: the more you consolidate your life inside Rakuten, the more Rakuten feels like the cheaper option—whether or not the sticker price changes.

Fintech Expansion—Becoming More Than E-Commerce

The points strategy really snapped into focus when Rakuten moved into financial services, because finance is where frequency lives. You might book travel a few times a year. You might shop online weekly. But you pay for things constantly.

Rakuten Card, launched in 2005, was the perfect wedge. It made points accumulation effortless, and it turned everyday spending into a steady stream of rewards that flowed back into the ecosystem. Over time, Rakuten became Japan’s largest credit card provider—an engine that helped keep customers coming back and kept merchants inside the Rakuten mall happy, because it encouraged repeat purchases.

By early 2021, Rakuten Card had surpassed 21 million users in Japan, with annual transaction volume topping 11 trillion yen. Later that year, the number of cards issued passed 23 million. And because points are baked into the experience, a portion of that spending reliably returned to customers in the form of points—fuel for the flywheel.

Around that core, Rakuten built out a full fintech suite: Rakuten Bank, Rakuten Securities, Rakuten Insurance, and electronic money services. The punchline is that points weren’t just a marketing gimmick for Ichiba anymore. They became the shared incentive layer across more than 70 services, including banking, brokerage, travel, and eventually mobile.

Rakuten consistently ranked highly in customer satisfaction in Japan, and it amassed over 100 million members—an astonishing number in a country of roughly 124 million people in 2024.

Points as Investment Vehicle

Then Rakuten pushed the idea into an unexpected place: investing.

Rakuten introduced a feature that let users invest using points, effectively giving people a “trial run” of the stock market without needing to part with cash. It was framed as a kind of mock investment experience—low-stakes, accessible, and especially appealing to younger consumers who might not have spare money to invest.

The concept resonated. Since launch, the program attracted interest from over five million users in Japan, and more than half were 30 or younger. Rakuten Securities also saw an influx of younger users, likely helped by this on-ramp that made investing feel less intimidating.

For anyone looking at Rakuten as a business, this points economy is both its greatest strategic asset and something it has to manage carefully. The upside is obvious: points create switching costs. If you’ve accumulated value and built routines across multiple Rakuten services, leaving is annoying and expensive. But there’s a flip side: points are also a promise—an obligation to provide future goods or services. In good times, that promise powers the ecosystem. In stressed times, it can start to look like a burden.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Englishnization Bet & Global Acquisition Spree (2010–2014)

A Japanese Company Goes English

By 2010, Rakuten’s points-powered ecosystem was working in Japan. The next question was whether it could travel. Mikitani’s answer wasn’t a new product or a new market entry plan. It was a culture shock.

In March 2010, he announced “Englishnization”: within two years, English would become Rakuten’s primary internal language—meetings, emails, documents, everything. In Japan’s corporate world, where hierarchy and subtlety often hinge on the nuances of Japanese, it was a jarring move. Some executives openly ridiculed it. Mikitani didn’t blink. His view was simple: “English is not an advantage anymore—it is a requirement.”

The implementation was as blunt as the announcement. Corporate officers who failed to become proficient were told they’d be dismissed. The backlash was real, and so were the practical obstacles—at the time, only a small portion of Rakuten’s Japanese staff could operate comfortably in English. Rakuten responded by making language training part of the job: free classes, time to study, and a clear message that this was not optional.

By 2012, Rakuten had formally adopted English as its official company language. The point wasn’t to be trendy. It was to make Rakuten recruitable, operable, and acquirable on a global stage—to integrate non-Japanese talent and overseas businesses without forcing everything through translation layers. Over time, that started to show in the numbers: by 2016, nearly 40% of the company’s engineers in Japan were non-Japanese. And the whole experiment became famous enough that it turned into a Harvard Business School case study on language and globalization.

The Global Shopping Spree

Englishnization wasn’t the strategy. It was the enabling move. The strategy was a buying spree.

Rakuten had been dabbling in overseas expansion since 2005, but in 2010 Mikitani sharply shifted focus and began assembling a portfolio of global assets: Buy.com in the U.S. (later Rakuten.com), PriceMinister in France, Canadian e-book platform Kobo (now Rakuten Kobo), the U.S. cash-back leader Ebates (now Rakuten Rewards), and Cyprus-based messaging app Viber (now Rakuten Viber).

The aim was clear: if Rakuten’s advantage in Japan came from tying services together, then buying footholds in commerce, content, and consumer internet abroad might let it recreate the ecosystem flywheel globally. Rakuten wasn’t just purchasing revenue streams. It was trying to purchase distribution, habits, and audiences—then stitch them together with the same kind of loyalty logic that had worked at home. Buy.com and Kobo, each acquired for $250 million (in 2010 and 2012), were early signals that Rakuten was willing to pay up to accelerate the plan.

The Viber Bet

In February 2014, Rakuten announced its biggest acquisition yet: it would buy Viber for $900 million and take 100% of the company.

At the time, Viber was one of the world’s major messaging and VoIP platforms, with around 280 million registered users and over 100 million monthly active users. On smartphones, it offered calling, messaging, and media sharing—exactly the kind of daily, high-frequency consumer surface Rakuten didn’t have outside Japan.

The logic was to capture mobile-first users in regions where Viber was already culturally embedded. Viber became especially strong in parts of Eastern Europe, including being the most downloaded Android messaging app in Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine as of 2016. It also had meaningful adoption in places like Iraq, Libya, and Nepal. By 2018, it had over 70% penetration in the CIS and CEE regions, but only about 15% in North America. In other words: deep, regional traction—just not the global dominance that would be needed to rival WhatsApp.

The Ebates Billion

Then, seven months later, Rakuten went even bigger.

It agreed to acquire Ebates for $1 billion in cash, taking 100% ownership. Ebates, founded in 1999, was a pioneer of online cash-back: it steered shoppers to retailers and split the affiliate economics back with users, creating a sticky habit for deal-minded consumers. The platform had a large retail network—more than 2,600 partners—and about 2.5 million active members at the time. In fiscal 2013, Ebates generated $2.2 billion in gross merchandise value, with $167.4 million in net revenue and $13.7 million in operating income.

Investors were unimpressed. Rakuten’s shares fell 4.2%, the biggest drop in three months, as analysts questioned whether these high-priced international deals would ever deliver returns that matched the ambition behind them.

And that criticism pointed at the core tension of Mikitani’s playbook. He was willing to spend billions to buy strategic surfaces—messaging, loyalty, e-commerce—on the belief that, eventually, the connections between them would matter more than the standalone financials. Viber plus Ebates alone was nearly $2 billion of bets on scale and network effects.

With hindsight, the results landed somewhere in the middle. Ebates, rebranded as Rakuten Rewards, became a meaningful and profitable contributor in the U.S. Viber didn’t break out globally against WhatsApp and other giants, but it held onto a strong regional franchise. What never fully arrived was the sweeping endgame: a unified, global super-app tying hundreds of millions of users across shopping, messaging, and payments into one Rakuten identity.

And that gap—between the elegance of the ecosystem theory and the messy reality of execution across borders—sets up the next phase of the story, when Mikitani made an even larger, far more dangerous bet closer to home.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Mobile Moonshot—Japan's Fourth Carrier (2018–2020)

The Jio Inspiration

Of all the decisions Mikitani made, none proved more consequential—or more polarizing—than deciding Rakuten wouldn’t just sell phones or partner with a carrier. It would become one.

The spark came from India. In 2016, Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Jio entered the market with a play that looked almost suicidal: build a modern, data-first network from scratch, price service at free or near-free to grab users, and assume scale would eventually make the economics work. Within two years, Jio had amassed more than 200 million subscribers and rewrote the rules of Indian telecom.

Mikitani saw a blueprint. He recruited Tareq Amin, the executive who had run Jio’s rollout, and pushed Rakuten into the race for one of Japan’s scarce spectrum licenses. In 2018, Rakuten won that license, positioning itself as Japan’s fourth mobile carrier alongside NTT DoCoMo, KDDI (au), and SoftBank. By 2019, Rakuten was officially Japan’s newest mobile network operator.

The Open RAN Revolution

Rakuten didn’t want to be “a smaller DoCoMo.” It wanted to build a different kind of carrier—one that looked more like a software company than a traditional telecom.

The ambition was sweeping: a cloud-native network, fully virtualized from the radio access network to the core, built with end-to-end automation. In early February 2019, Rakuten ran one of its first real-world end-to-end tests around its Tokyo headquarters, with Mikitani and the team doing live voice and video calls over Viber on the fledgling network.

Underneath that demo was Rakuten’s technical thesis: Open RAN. Instead of buying a monolithic, single-vendor radio network, Open RAN breaks the system into components—distributed units, centralized units, and radio units—connected by open interfaces. That modularity allows key parts of the network to be virtualized and run on commercial off-the-shelf servers, with software doing more of the work that used to require proprietary hardware. Rakuten positioned its build as the first fully virtualized, cloud-native Open RAN network in the world.

Mikitani framed it as classic Rakuten: another attempt to disrupt an industry by changing the cost structure and shifting power away from incumbents. The promise was stability and scalability through automation—and, crucially, a path to lower operating costs than carriers locked into traditional vendor stacks.

The Commercial Launch

Rakuten Mobile launched full commercial 4G service in April 2020—straight into the COVID-19 pandemic. The timing cut both ways. The world was shutting down, but demand for connectivity was exploding as work, school, and entertainment moved online.

Rakuten’s go-to-market offer was as aggressive as Jio’s: early users got unlimited service free for the first year. It was a headline-grabber and a fast way to build a base. But it also meant the company was carrying the most expensive part of the journey—building a national network—while collecting little to no revenue from many of the customers it was signing up.

The Capital Underestimation Problem

Then came the part that would haunt the entire Rakuten group: the bill.

Rakuten’s early cost expectations turned out to be far too optimistic. Building a mobile network is brutally capital intensive, and the integration burden of a highly disaggregated Open RAN approach proved harder than the marketing story suggested. As analysts at Moor Insights & Strategy put it, Rakuten became the poster child for Open RAN—but underestimated the difficulty of integrating so many moving parts.

The financial drag showed up quickly. Since 2019, the broader Rakuten group accumulated net losses of more than 1 trillion yen (about $6.9 billion) on revenue of 11.8 trillion yen (about $79.7 billion). Rakuten Mobile’s losses also kept rising as it pushed to expand coverage. It reported 54.9 billion yen (about $482 million) in revenue, while losses in the third quarter of 2021 jumped to 105.2 billion yen (around $923 million).

At a strategic level, the problem was simple and brutal: Rakuten had taken a Jio-shaped plan and tried to run it in a market that wasn’t India.

When Jio arrived, India had patchy mobile data, massive pent-up demand, and relatively low customer loyalty. Japan was the opposite. The networks were already excellent, consumers were demanding, and the incumbents were deeply entrenched. In that environment, low prices alone weren’t enough—and Rakuten was learning, in real time, that technical ambition doesn’t reduce the cost of a national rollout. It just changes where the difficulty lives.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Capital Crisis & Japan Post Rescue (2021–2023)

The Strategic Bailout

By early 2021, the mobile bet had pushed Rakuten into a place it hadn’t been before: it needed outside money, and it needed it fast.

The lifeline came from an institution that feels almost mythically “Japan”: the postal system.

In March 2021, Rakuten announced at a joint press conference—Mikitani standing alongside the president of Japan Post Holdings—that Japan Post would invest 150 billion yen in exchange for more than an 8% stake. It was Rakuten’s first major capital tie-up of this kind, and it instantly made Japan Post Holdings the company’s third-largest shareholder after the Mikitani family.

The round didn’t stop there. Tencent and Walmart—both tied to Seiyu Group, which Rakuten partially owned—also took stakes of 3.65% and 0.9%. In total, Rakuten said it planned to raise 242 billion yen by issuing new shares to Japan Post Holdings, Walmart, and an investment firm backed by Tencent.

But the money was only half the story. The deeper logic was strategic: Rakuten had digital reach—more than 70 services and over 100 million members in Japan—while Japan Post had something Rakuten didn’t and Amazon did: physical infrastructure everywhere. Post offices in essentially every community. A shipping network that already covered the entire country. Real-world touchpoints that could become pickup and return locations, customer service counters, and even Rakuten Mobile sign-up sites.

Alongside the investment, the two groups signed a business alliance agreement spanning logistics, mobile, and digital transformation. They also flagged future collaboration in financial services, including cashless payments and insurance, and in e-commerce through joint work on product sales.

It was, in other words, a rescue package that doubled as an ecosystem upgrade: cash to keep building the network, and a nationwide partner to help Rakuten compete in the very places Amazon was strongest.

The Mounting Losses

The problem was that a bailout doesn’t change the physics of telecom.

Even after the capital infusion, losses kept piling up. Since 2019, Rakuten had accumulated cumulative net losses of more than 1 trillion yen on revenues of 11.8 trillion yen. And the pressure didn’t really let up: in the first half of 2025, it booked a net loss of about 102 billion yen on sales of 1.16 trillion yen.

Inside the company, the risk was becoming obvious. Mobile was consuming cash quickly enough that it threatened the crown jewels—the profitable e-commerce and fintech businesses that had funded Rakuten’s rise. To keep going, Rakuten leaned on multiple rounds of fundraising, including bond issuances and asset sales, buying time while it tried to push the mobile business toward something resembling sustainability.

Rakuten Symphony: Selling the Technology

So Rakuten tried to create an escape hatch: if building the network in Japan was this expensive, could the underlying technology become a product?

That became Rakuten Symphony, a Rakuten Group company that sells B2B services to the telecom industry—built on the same cloud-based, virtualized network architecture Rakuten used for its own rollout. The pitch was straightforward: Rakuten had already done the hard thing, and now it could help other operators build “next-generation” networks without repeating the pain.

The flagship proof point was Germany’s 1&1. 1&1 chose Rakuten Symphony as a long-term partner to build Germany’s fourth mobile network—framed as Europe’s first Open RAN-based commercial mobile network. Under the “1&1 O-RAN” banner, 1&1 began offering Fixed Wireless Access in December 2022 and later expanded to mobile services, describing the result as Europe’s first fully virtualized 5G Open RAN network, launched in just 28 months.

For investors, Symphony landed as both hope and warning at the same time. Hope, because if Open RAN and cloud-native networks become the default, Rakuten could be early enough—and credible enough—to build a valuable global software-and-services business. Warning, because Rakuten was also trying to sell technology to the same telecom industry it was fighting in Japan, and that inherent conflict shrinks the list of customers willing to buy.

VIII. The Current Struggle: A Tale of Two Businesses (2023–2025)

Mobile: The Turnaround Takes Shape

For years, Rakuten Mobile’s subscriber numbers were the easiest punchline in the entire Rakuten story. The network was late, the experience was uneven, and the incumbents were entrenched. But by 2024 and 2025, the trajectory finally started to bend in Rakuten’s favor.

On December 25, 2025, Rakuten Mobile announced it had surpassed 10 million total subscribers—reached five years and eight months after its full-scale commercial launch in April 2020. Not a Jio-style overnight coup, but real momentum all the same.

The cadence shows how long the climb was, and how it gradually picked up speed: 6 million subscribers by late December 2023, 7 million by mid-June 2024, 8 million by mid-October 2024, 8.5 million by late February 2025, 9 million by early July 2025, and then 10 million by late December.

Rakuten credits a broad set of initiatives aimed at different customer segments, along with improving coverage and day-to-day performance. New subscriptions at Rakuten Mobile stores rose by about 20% year-on-year, and the company continued to position the Rakuten Saikyo Plan—its unlimited data offering—as the simple, all-in alternative in a market full of caveats.

Just as importantly, the network stopped being the obvious weak link. In the October 2024 Japan Mobile Network Experience Report, Rakuten Mobile ranked first among Japanese operators for 5G upload and download speeds. The report put average 5G upload speeds at 27 Mbps and downloads at 176.5 Mbps, with Rakuten ahead of the next competitor on upload speed by 21 Mbps.

Financial Milestones Achieved

Subscribers are one thing. The bigger question has always been whether mobile would ever stop dragging the rest of Rakuten underwater. In 2024, Rakuten started to put markers on the board that suggested the answer might finally be “yes.”

For fiscal year 2024, Rakuten reported consolidated revenue of 2.3 trillion yen, up 10% year-on-year, extending what it described as 28 consecutive years of revenue growth. More notably, it said it hit all three financial targets it set at the start of the year: consolidated full-year Non-GAAP operating income profitability, monthly EBITDA profitability for Rakuten Mobile, and self-funding at the group level.

In December 2024, Rakuten Mobile’s standalone monthly EBITDA turned positive for the first time since it entered the mobile network operator business. Management framed that as a key inflection point, because it corresponded with a meaningful narrowing of mobile’s losses.

On a group basis, both Non-GAAP operating profit and IFRS operating profit were positive in fiscal year 2024—the first time since 2019. Profit before tax also moved into the black, with a surplus of 16 billion yen, the first since fiscal year 2018.

For fiscal year 2025, Rakuten’s stated goal was to expand consolidated Non-GAAP operating income profitability and deliver full-year EBITDA profitability for Rakuten Mobile.

The Ecosystem Businesses: Still Strong

Even in the worst years of the mobile saga, Rakuten’s core thesis was that the rest of the ecosystem could keep producing cash and loyalty—long enough for telecom to mature. In 2024, those underlying businesses continued to look like Rakuten’s real foundation.

Rakuten Ichiba kept expanding its merchant base, including internationally. Overseas-affiliated merchants surpassed 1,000, with gross merchandise sales growing at a double-digit rate and contributing to overall growth on the platform. In Japan, Rakuten Ichiba held roughly a 27% market share and generated close to 6 trillion yen in domestic GMS in 2024—scale that keeps it central to Rakuten’s identity and its points-driven flywheel.

In the Internet Services segment, revenue reached 1.28 trillion yen in fiscal year 2024, up 5.8% year-on-year. Non-GAAP operating income rose to 85.1 billion yen, up 29.8%, delivering growth in both revenue and profit. Rakuten also said its International Business Unit—overseas Internet Services—achieved full-year profitability, contributing to the segment’s profit increase.

Fintech remained a pillar, too. Rakuten Securities posted steady growth across key metrics as its customer base expanded. Even after introducing zero-commission trading for Japanese stocks in October 2023, the company said it grew both revenue and profit by broadening revenue sources and keeping marketing spend under control. Accounts reached 11.93 million by the end of December 2024, up 17% year-on-year, and surpassed 12 million in January 2025.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case Analysis

The Bull Case

The optimistic view of Rakuten rests on a few big ideas—each of which, if it holds, makes the whole story look less like overreach and more like a long game.

Ecosystem Moat: Rakuten has built something rare: a tightly integrated consumer ecosystem that spans e-commerce, financial services, telecom, and digital content, all stitched together by a single loyalty currency and a shared membership base. The power isn’t any one product. It’s the closed loop. Earn points in one place, spend them somewhere else, and get rewarded for doing more of your life inside the Rakuten universe. Over time, that turns into real switching costs: if your points balance, credit card, securities account, and mobile plan all live under one roof, leaving isn’t just “downloading a new app.” It’s unwinding a lifestyle.

Mobile Inflection: After years of painful losses, Rakuten Mobile has started to look less like a reckless experiment and more like a business entering its second act. Group profitability still isn’t a given, but mobile’s improving metrics and clearer strategy suggest the disruptive model may finally be settling into something sustainable. If Rakuten can get to durable profitability in telecom, the narrative flips—from “capital destruction” to “patient investment that created a fourth pillar of the ecosystem.”

B2B Technology Platform: Rakuten Symphony is the wildcard. The market can look at it as a side project, but the bull case sees it as monetizing the hardest thing Rakuten has done: building a modern, cloud-native network. Symphony has leaned into India’s growth story and says it aims to collaborate with telecom operators, enterprises, and governments. With more than 3,000 experts in the country and an India Global Innovation Lab in Bengaluru focused on telecom and AI research, Rakuten is trying to turn its mobile scars into a sellable platform. If Open RAN becomes the default architecture for 5G and eventually 6G, Rakuten’s early credibility could matter—a lot.

Japan Market Position: Even after everything, Rakuten Ichiba is still a heavyweight in Japanese e-commerce, maintaining roughly a 28% market share. It draws more than 100 million shoppers and positions itself not just as a place to list products, but as a partner that helps merchants build and grow. In the bull view, that merchant-centric model—paired with points and fintech—keeps Rakuten durable at home, even as the global internet consolidates.

The Bear Case

The skeptical view is simpler: Rakuten may have built an impressive ecosystem, but the cost of mobile—and the reality of competition—could keep it from ever paying off.

Mobile Economics: The fundamental question hasn’t changed: can a fourth carrier in a mature, saturated market ever produce returns that justify the billions poured into it? Japan’s incumbents entered the fight with scale, spectrum, and infrastructure advantages that are difficult to overcome. Losses have narrowed and the path to profitability is more visible than it used to be. But the bear case is that telecom doesn’t end with a cinematic upset. It ends with grind—modest share, relentless capex, and economics that never quite clear the bar Rakuten needs.

Amazon Competition: In e-commerce, the threat never sleeps. Amazon Japan’s traffic is enormous—hundreds of millions of monthly visits as of August 2024—and its share of online spending is massive. The bear argument is that Amazon has become the default setting for online shopping in Japan, and it wins with logistics, selection, and convenience. Rakuten can fight with points and merchant relationships, but Amazon can keep squeezing the market with scale Rakuten can’t easily match.

Balance Sheet Stress: Years of mobile investment have strained the balance sheet. Rakuten’s total debt-to-equity ratio stands at 470.22%, a reminder that even if operations improve, leverage limits strategic flexibility. The capital situation may be calmer than the peak-crisis moments, but the bear case is that the margin for error is still thin.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis: - Threat of New Entrants: Low in e-commerce (Rakuten’s scale and ecosystem create barriers), Moderate in mobile (spectrum scarcity limits new carriers) - Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate (technology vendors have alternatives, but Rakuten’s scale provides leverage) - Bargaining Power of Buyers: High (consumers can easily compare prices and switch between platforms) - Threat of Substitutes: High (Amazon, Yahoo Shopping, direct-to-consumer brands) - Competitive Rivalry: Intense across all segments

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework: - Network Effects: Strong in the points ecosystem (more services means more ways to earn and spend, which increases stickiness) - Switching Costs: Moderate to Strong (points balances and multi-service integration create real friction) - Counter-Positioning: Once strong (merchant-empowerment versus Amazon’s centralized model) but weakening as competitors borrow similar tactics - Scale Economies: Weak (Rakuten lacks Amazon’s logistics scale; mobile remains a scale-driven game) - Cornered Resource: Limited (Viber’s regional strength; the Japan Post partnership) - Process Power: Moderate (Rakuten has learned how to integrate services into a working ecosystem) - Brand: Strong in Japan, limited globally

X. What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

If you want to track whether Rakuten’s story is bending toward a clean turnaround—or just a temporary reprieve—there are three numbers that tell you the most, the fastest.

1. Rakuten Mobile ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) and Subscriber Net Adds

Rakuten Mobile’s ARPU in Q4 FY2024 rose modestly quarter-on-quarter, reaching 2,856 yen. The company attributed the lift to higher data ARPU, more advertising revenue per user, and the start of charging fees for certain optional services.

The tension to watch is straightforward: can Rakuten keep adding subscribers without sacrificing the economics that make mobile sustainable? Telecom disruptors often buy growth with pricing that permanently damages unit economics. Here, the tell is whether Rakuten can keep healthy subscriber momentum while nudging ARPU up toward the 3,000-yen range.

2. Cross-Service Usage Rate

Rakuten’s ecosystem only works if customers behave the way the flywheel predicts: once they join, they keep adding services. The company has pointed to cross-use metrics as a signal that this is happening, including a cross-use percentage that reached 72.3% for users engaging with multiple Rakuten services.

This is the ecosystem’s vital sign. If more people are using two or more services, Rakuten gets stickier, churn gets harder, and customer acquisition gets cheaper. If that number slips, it suggests the opposite: fragmentation, weaker loyalty, and less leverage from points. The bar to beat, going forward, is whether Rakuten can push this toward the mid-70s.

3. Consolidated Operating Profit (Non-GAAP)

After years of red ink, Rakuten returned to consolidated operating profitability in FY2024. Non-GAAP operating profit improved year-on-year to 7,048 million yen.

The key now is durability. One profitable year matters, but what matters more is whether Rakuten can keep this positive as mobile continues its slow shift from heavy losses toward break-even. If consolidated profitability holds and strengthens, the narrative changes: the “two Rakutens” problem—profitable ecosystem versus loss-making mobile—starts to look less like a structural flaw and more like a chapter Rakuten is finally closing.

XI. Conclusion: The Verdict on an Audacious Gamble

Rakuten doesn’t fit neatly into a single box. It’s a company that built one of the world’s most effective loyalty ecosystems, then tried to turn that advantage into something even bigger: a full-stack digital life in Japan, anchored not just by shopping and finance, but by the one service that touches your pocket all day long—mobile.

That ambition came with a price. Rakuten pioneered a cloud-native, Open RAN-style network and proved a fourth carrier could be built in Japan. It also endured years of bruising losses—more than $6 billion cumulatively—as the cost of building nationwide coverage collided with the reality of a mature, highly competitive telecom market.

And still, by December 25, 2025, Rakuten Mobile hit 10 million subscribers. Not an overnight Jio-style land grab, but a real milestone that would have sounded far-fetched when the service was struggling and the red ink was at its worst. Mobile profitability is no longer a fantasy. It’s visible. It’s just not guaranteed.

Meanwhile, the original Rakuten—the ecosystem business—kept doing what it has always done: printing cash and reinforcing habits. E-commerce and fintech remained the foundation, generating operating profit and keeping the points flywheel turning.

So the debate doesn’t go away; it just gets sharper. Can Rakuten hold its roughly 27% share of Japanese e-commerce as Amazon keeps pushing? Does Rakuten Symphony become a real B2B platform business, or a compelling demo in search of enough customers? And in mobile, can Rakuten keep growing subscribers while steadily improving unit economics, instead of trading one for the other?

The honest verdict on Mikitani’s telecom moonshot is that it was both visionary and reckless. It was audacious enough that most boards would have killed it on the first slide. It came close to breaking the company. But it also may have created a fourth pillar that strengthens the entire ecosystem—because if Rakuten can own the connection, it can influence everything that travels over it: payments, shopping, media, and loyalty.

For investors, that’s the tension. The bear case is easy to understand because it’s written in years of losses and balance-sheet strain. The bull case is harder to model, but potentially more powerful: an integrated ecosystem that becomes harder and harder to leave as more of daily life runs through it.

Mickey Mikitani named his company “optimism.” Nearly three decades later, that optimism has been stress-tested by competition, crises, and self-inflicted wounds. Yet Rakuten is still here—still expanding the ecosystem, still pushing the thesis that one company can weave commerce, money, and connectivity into a single consumer relationship.

Whether that ultimately translates into great shareholder returns remains unresolved. But the attempt itself—the scale of the bet, and the stubbornness required to survive it—makes Rakuten one of the most compelling business stories of the internet era.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music