Trend Micro: The Cybersecurity Survivor from Three Continents

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

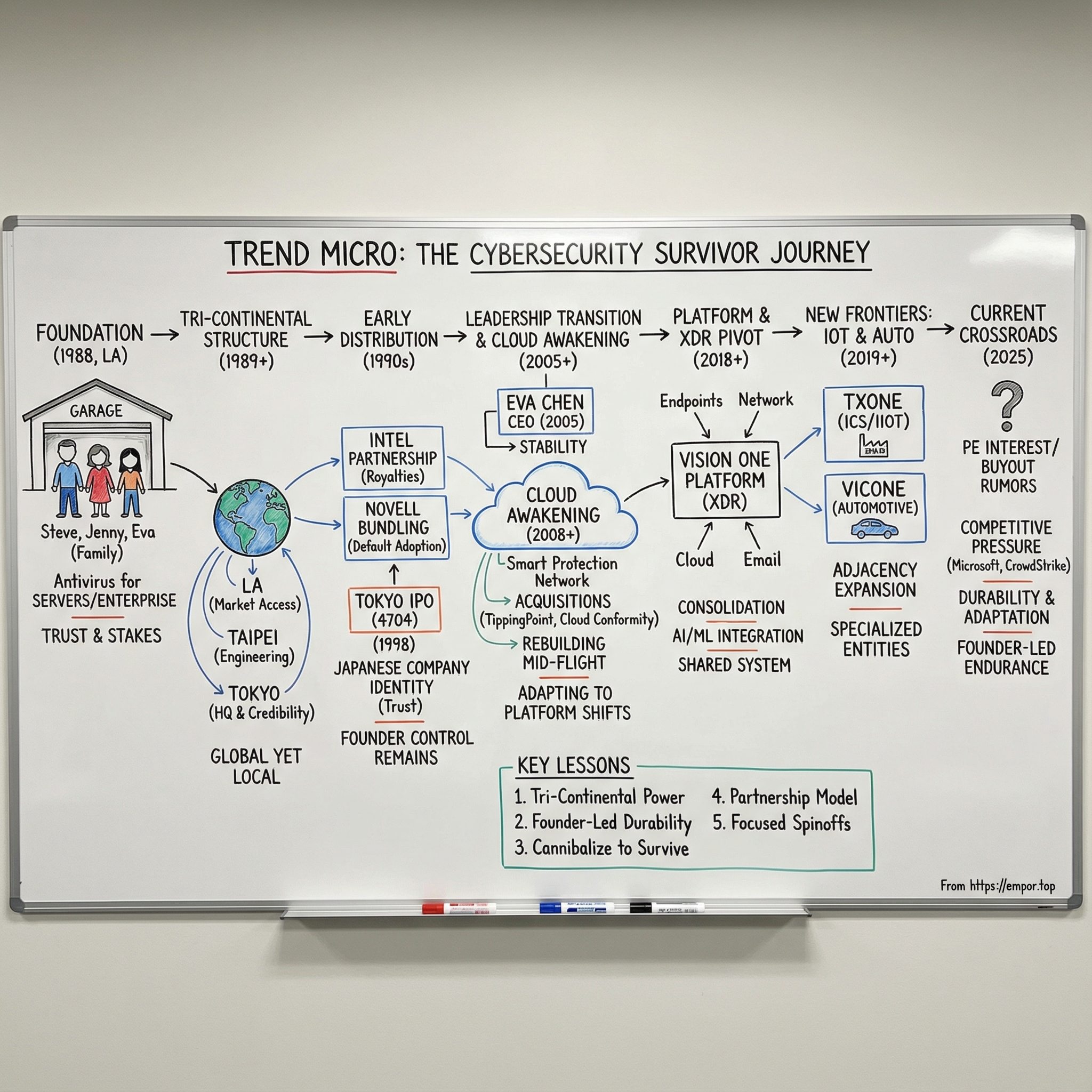

Cybersecurity is a graveyard of former kings. Categories shift, platforms move, buyers consolidate, and yesterday’s “must-have” vendor becomes tomorrow’s distressed asset. And yet, one company has quietly kept showing up—year after year, wave after wave.

Trend Micro is now a global cybersecurity business with more than $1.7 billion in revenue and over 7,000 employees. But the interesting part isn’t the scale. It’s what that scale represents: endurance in a market that has chewed up the companies that invented the category.

Look at the wreckage. Symantec’s enterprise security business ended up sold to Broadcom in 2019. McAfee went through Intel, lost massive value under that ownership, and was ultimately spun out to private equity. These weren’t niche players. They were antivirus royalty—brands so synonymous with security that people used the names as shorthand for the whole concept.

And yet Trend Micro remains.

It’s an American-Japanese cybersecurity company with R&D spread across 16 locations on every continent except Antarctica. It’s also been consistently recognized by Gartner, including being positioned in the Leaders’ Quadrant of the 2024 Gartner Magic Quadrant for Endpoint Protection Platforms, and it has been named a Leader in that category 19 times in a row since 2002.

So here’s the central puzzle: how did a company founded by Taiwanese entrepreneurs in Los Angeles, headquartered in Tokyo, and listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange under ticker 4704 survive for more than 35 years in one of tech’s most brutal, fast-evolving arenas—while its biggest rivals were traded, carved up, and repackaged?

Part of the answer sits in leadership. Eva Chen, a co-founder, has been CEO since 2005. Steve Chang, the founding CEO, remains chairman. Trend isn’t run by rotating professional managers or financial engineers. It’s still founder-led—an increasingly rare advantage in enterprise software, and especially rare in cybersecurity.

That sets up the themes we’ll follow: a family business model operating inside enterprise tech; a set of platform transitions from client to server to cloud to XDR; a tri-continental operating structure that is weird on paper but powerful in practice; and the discipline to keep adapting in a market where every decade brings an extinction-level event.

II. The Founding Story: A Family Startup in LA

Los Angeles, 1988. Personal computers are spreading from hobbyist corners into actual business workflows. Most executives still think of computing as an internal tool, not a connected risk surface. And “computer virus” is a phrase more people have heard in science fiction than in boardrooms.

That’s when Steve Chang, his wife Jenny Chang, and Jenny’s sister Eva Chen founded Trend Micro. From day one, this wasn’t a conventional startup. It wasn’t just co-founders—it was family. Trust ran deep. So did the stakes.

The company was funded with proceeds from Steve Chang’s earlier sale of a copy protection dongle to Rainbow Technologies. Chang wasn’t a first-time founder swinging at a trend. He had engineering chops and business experience. He worked at Hewlett-Packard, then founded AsiaTek, a Taiwan-based UNIX software design company.

Chang was born in Pingtung, Taiwan. He earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Fu Jen Catholic University in 1977, then moved to the U.S. and completed a master’s degree in computer science at Lehigh University in 1979. After returning to Taiwan, he worked for Hewlett-Packard and led sales operations across seven counties and cities in southern Taiwan.

Inside the founding trio, the roles were complementary. Steve was the market-spotter and relationship-builder. Jenny ran operations and helped shape the culture. And Eva Chen was the technical force. Since co-founding Trend Micro in 1988, she has been central to shaping the company’s security technology. Before becoming CEO, she served as executive vice president from 1988 to 1996 and CTO from 1996 to 2004.

Eva holds dual master’s degrees in business administration and management information systems from the University of Texas, plus a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Chen Chi University in Taipei. Philosophy might sound like an odd credential for a cybersecurity leader—until you remember what security actually is: reasoning about systems, adversaries, constraints, and first principles.

Trend Micro began commercial operations in May 1989, just as the world started discovering what networked computing would really mean. In November 1988—months after Trend was founded—the Morris Worm tore through the early internet, infecting an estimated 6,000 computers, roughly 10% of the machines online at the time. It was one of the first proof points that connectivity wasn’t just a feature; it was a vulnerability multiplier.

From the start, Trend’s vision centered on antivirus software. But the key nuance is where it focused. Trend leaned into security for servers and small businesses—an enterprise-leaning posture—while many competitors chased mass consumer distribution through retail shelves.

That single decision would echo for decades. While others built brands for individuals, Trend built relationships with IT departments. And in enterprise software, relationships are the moat.

III. The Tri-Continental Architecture: LA to Taipei to Tokyo

Then Trend Micro did something that looks almost irrational if you’re expecting a Silicon Valley script.

Instead of staying in California, raising venture capital, and aiming straight for NASDAQ, the founders moved headquarters to Taipei shortly after establishing the company. The logic was practical and sharp: Taiwan offered deep engineering talent and lower costs, and it was geographically positioned for Asia’s fast-growing markets. Meanwhile, Trend maintained U.S. sales operations to stay close to Western customers.

Today you’d call that a distributed global model. In 1989, it was just… unusual.

Then came the defining move. In 1992, Trend Micro took over a Japanese software firm to form Trend Micro Devices and established headquarters in Tokyo.

Why Japan? In the early 1990s, Japan was the world’s second-largest economy, and its enterprise market was enormous, demanding, and famously sticky. Winning Japanese corporate customers was hard. But once you were in, you often stayed in—sometimes for decades—because those vendor relationships were built slowly and protected fiercely.

Trend’s early history saw these strategic relocations stack on top of each other: founded in Los Angeles, headquarters moved to Taipei, then Japan through acquisition, then headquarters in Tokyo. Over time, this became more than geography. It became identity.

By positioning itself as a Japanese-headquartered company, Trend could sell into Japanese enterprises as a “local” provider, with local support and executive presence. That’s a fundamentally different risk profile for a buyer than “an American startup with a distributor.”

The result was a three-part machine: Japanese corporate credibility, Taiwanese engineering execution, and American market access. Trend’s R&D ultimately spread even further—16 locations across every continent except Antarctica—while the head office stayed in Tokyo and North American headquarters remained in Cupertino.

Operationally, it meant Trend could show up differently depending on the customer. A Japanese bank could meet executives in Tokyo. A U.S. tech buyer could engage the Cupertino organization. Engineering could run fast in Taiwan. And the company developed a kind of resilience you don’t get when all your weight sits in one economy, one culture, or one market cycle.

It wasn’t a business-school case study. It was immigrant founders building around their real networks and realities—moving across borders the way they already knew how to.

IV. The Intel Partnership & Early Distribution Mastery

In the early 1990s, antivirus wasn’t won by whoever had the best detection engine. It was won by whoever could get installed.

Trend Micro didn’t have Symantec’s consumer brand or McAfee’s enterprise reach. Instead, it made a decision that would define its go-to-market for years: let giants carry the distribution.

Trend made an agreement with Intel under which it produced an anti-virus product for local area networks sold under the Intel brand. Intel paid royalties to Trend Micro for sales of LANDesk Virus Protect in the U.S. and Europe, while Trend paid royalties to Intel for sales in Asia.

That deal did three things at once. It gave Trend instant credibility. It gave Trend distribution without building an expensive direct sales machine. And it created a royalty-driven revenue base that could fund product development.

Then, in 1993, Novell began bundling Trend’s antivirus product with its network operating system. At the time, Novell NetWare was the backbone of corporate networks. Bundling didn’t just create exposure—it created default adoption. It made Trend part of the network stack, not just a product you’d remember to buy later.

In 1996, the agreement evolved again: Trend could globally market ServerProtect under its own brand alongside Intel’s LANDesk brand. Trend was earning the right to stand on its own name—without giving up the distribution advantages that got it there.

Intel, Netscape, Novell, SCO, and Sun Microsystems were among the companies selecting Trend’s server-based virus protection as part of their premier offerings. That list reads like a time capsule of computing’s power centers—and it shows how Trend used partnerships as a substitute for brute-force sales scale.

Meanwhile, Trend’s product line tracked the broader platform shift happening in enterprise computing. Early sales were primarily desktop programs like PC-cillin/Virus Buster, introduced in Japan in 1991. As companies moved from stand-alone PCs to client-server networks, Trend introduced LANprotect in 1993, its first server application. As the internet expanded enterprise exposure, InterScan VirusWall arrived in 1996 to scan at the internet gateway in real time.

Under Steve Chang’s leadership, Trend grew rapidly. Revenue expanded from about $10 million in 1994 to $454 million by the end of 2003, and the company grew to more than 2,000 employees across more than 30 countries.

It wasn’t the flashy Silicon Valley model. It was disciplined distribution strategy, compounding partnerships, and a willingness to hitch Trend’s wagon to each era’s dominant platform.

V. The Tokyo IPO & Becoming a Japanese Company

In 1998, Trend Micro listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange under ticker 4704. The path there mattered: an initial public offering on Japan’s over-the-counter market in August 1998, then American Depositary Shares on NASDAQ in July 1999, and later a listing on the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in August 2000.

For a company founded in Los Angeles, choosing Japan as the primary public home looked counterintuitive. But strategically, it was surgical.

Listing in Tokyo helped cement Trend’s identity as a Japanese enterprise vendor—not just a company with a Japan office. That identity mattered in enterprise procurement across Asia. It also opened access to Japanese institutional capital and embedded Trend inside Japan’s business ecosystem.

Trend Micro Incorporated is listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange Prime Market and is part of the Nikkei 225 futures universe. That’s not just prestige; it brings visibility, coverage, and structural ownership from index-linked capital.

The timing also couldn’t have been better. The late 1990s and early 2000s were the perfect storm for security awareness: dot-com boom IT spending, Y2K urgency, and headline-grabbing email viruses like Melissa and ILOVEYOU turning “antivirus” into a board-level concern.

Trend later delisted its depository shares from NASDAQ in May 2007, leaving Tokyo as its home base. The burdens of dual compliance—especially after Sarbanes-Oxley—weren’t worth it. And by then, Trend didn’t need the symbolism of NASDAQ to be taken seriously.

Founder control remained a steadying force. Steve Chang stayed chairman and the largest individual stockholder, and while the details of any special voting structure aren’t publicly detailed, the combination of founder leadership and meaningful ownership strongly suggests continued founding-family influence over strategy.

That influence would matter as the rest of the industry entered an era of consolidation, roll-ups, and financial engineering.

VI. The CEO Transition: Eva Chen Takes Command

Every founder-led company eventually faces succession. Trend’s solution was to keep continuity, but shift the center of gravity.

In 2004, Steve Chang split the responsibilities of CEO and chairman. In January 2005, co-founder Eva Chen became CEO. She had been CTO since 1996 and before that executive vice president since the company’s early years. Chang stayed on as chairman.

This wasn’t a board installing a new operator. This was the technical co-founder—someone who understood the threat landscape and the product architecture—taking the helm. Under her leadership as CTO, Trend developed a series of industry firsts, from security products to security management strategies that helped establish the company globally.

Chen has been recognized widely, including being named among the Top 100 Women in Cybersecurity (2020), ranked among the Top 10 High-Flying Women in Technology by V3 Magazine (2012), included in Forbes Asia’s 50 Power Businesswomen list (2012), and receiving the Cloud Security Alliance Industry Leadership Award (2012).

More importantly, the leadership model didn’t change every few years. Eva Chen has now led Trend Micro for two decades. In a sector where leadership churn is common—and where private equity ownership often triggers cost cutting and instability—that kind of continuity becomes a competitive asset.

“Our founders have set the tone, the culture, and our road to innovation, building a strong team of passionate people who work together to make the world safe for exchanging digital information, today, and in the future.”

Soon after, Trend began targeted acquisitions to fill capability gaps. In May 2005, Trend acquired U.S.-based antispyware company InterMute for $15 million, integrating its SpySubtract program into Trend’s offerings by the end of the year. In June 2005, Trend acquired Kelkea, a U.S.-based developer of antispam software, including MAPS and IP filtering tools that helped service providers block spam and phishing.

In February 2008, Trend acquired Identum for an undisclosed sum. Identum, originally founded within and later spun out from the University of Bristol cryptography department, developed ID-based email encryption software. Trend initially explored licensing the technology, then decided to buy the company outright. Identum became Trend Micro (Bristol), and its encryption tech was integrated into existing products.

This was the pattern under Eva: not empire building for its own sake, but selective moves to expand what Trend could protect—and how.

VII. Inflection Point #1: The Cloud Awakening

Every durable tech company eventually faces the same terror: the platform moves.

Trend Micro’s core strength for years had been server security in on-premise enterprise data centers. But once cloud computing took off—AWS launched commercial services in 2006, and by 2010 the migration was unmistakable—Trend’s core market was starting to evaporate, or at least relocate.

This wasn’t a minor product shift. It threatened the environment Trend was designed for, the buyers Trend sold to, and the architecture Trend had spent decades refining.

Trend adapted by doing what it had done before: attach itself to the new platform leaders rather than trying to resist the shift. The company develops enterprise security for servers, containers, cloud environments, networks, and endpoints. Its cloud and virtualization security products provide automated protection for customers of VMware, AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform.

In June 2008, Trend introduced the Smart Protection Network, a cloud-client content security infrastructure that delivered global threat intelligence to protect customers from malware, phishing, and other web, email, and mobile threats. In 2012, Trend added big data analytics to improve behavioral identification of new threats.

In October 2015, Trend agreed to buy TippingPoint from HP Inc. for $300 million. This included the Zero Day Initiative, a major bug bounty program that became part of Trend Micro Research’s work on vulnerabilities and emerging threats.

That matters because cloud security isn’t just about policy and configuration. It’s about seeing what’s coming next. ZDI gave Trend a wider lens into vulnerabilities, often before they became widespread incidents.

In October 2019, Trend acquired Cloud Conformity, a Cloud Security Posture Management company. In November, it announced Cloud One, a suite of security products for organizations building platforms in the cloud. The message was simple: don’t fight the cloud—secure it.

This is the hard part for any incumbent: you have to rebuild the business while the old one is still paying the bills. Trend had to keep legacy customers protected while building cloud-native capabilities that might ultimately cannibalize the legacy base. It was rebuilding the plane mid-flight.

Plenty of competitors didn’t make this transition cleanly. Broadcom’s approach to acquired software—often centered on slashing costs—can lift margins but risks slowing support and innovation, creating headaches for customers running multiple products. Trend, by contrast, stayed independent, kept investing, and made it through the cloud era without getting dismantled.

VIII. Inflection Point #2: The Platform Consolidation & XDR Pivot

By 2018, the security problem wasn’t just threats. It was tool sprawl.

Enterprises were running dozens of security products, each with its own console and alerts. Security teams were drowning in noise and struggling to connect signals across endpoints, email, networks, and cloud workloads. The buyer demand became clear: fewer vendors, more integration, better outcomes.

Trend’s response was to consolidate its own portfolio into platform-shaped products. Apex One launched in October 2018, with SaaS generally available in November 2018 and on-premises in February 2019. It evolved from Trend Micro OfficeScan and aimed to deliver endpoint security through a single agent.

But the bigger shift was XDR. Extended Detection and Response integrates endpoint, network, cloud, email, and identity protection into a unified system—centralized visibility, better detection, automated response, and faster investigation. Instead of isolated tools, XDR correlates signals across multiple layers so security teams can catch complex attacks earlier and reduce dwell time. It often leverages AI, machine learning, and automation to improve detection precision and orchestrate actions.

In 2022, Trend launched Trend Micro Vision One, integrating multiple security solutions into a single platform for comprehensive threat detection and response. The platform saw a customer growth rate of 150% within its first year of release.

Trend later positioned the next generation of the platform as a step change: stronger attack surface risk management, cross-layer protection across hybrid environments, next-generation XDR, and generative AI enhancements.

Underneath it all sits Trend’s threat intelligence engine: 16 research centers globally, hundreds of threat researchers, and the Zero Day Initiative feeding intelligence into the platform.

The bet here was structural: stop selling a collection of products, and start selling a shared system. Vision One wasn’t just a new SKU. It was a new architecture—and a new way to compete in a market that was increasingly rewarding platforms over point solutions.

That shift showed up in adoption. Industry consolidation and demand for AI-powered security drove platform growth, with over 780 new customers year-to-date and more than 10,000 customers in total leveraging Trend’s enterprise platform.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The IoT & Automotive Bet—TXOne and VicOne

While much of the cybersecurity world kept its eyes on endpoints and cloud workloads, Trend looked outward—to where computing was spreading next.

Factories. Utilities. Cities. Vehicles.

Trend Micro and Moxa executed a letter of intent to form TXOne Networks, focused on the security needs of Industrial Internet of Things environments: smart manufacturing, smart city, smart energy, and more.

Founded in 2019 as a joint venture between Trend Micro and Moxa, TXOne evolved into an individual brand focused on adaptive ICS/IIoT cybersecurity solutions for the operational technology environment.

The timing made sense. Industrial environments were getting connected, but much of the equipment had been designed long before security was part of the requirements. IT and OT teams historically ran separate networks with different constraints. Many devices weren’t built to be patched easily—sometimes not at all—making traditional IT security approaches a poor fit.

TXOne later announced the closing of a $70 million Series B round led by TGVest Capital, bringing total raised to $94 million. TXOne reported it was on track to continue more than 100% growth for three consecutive years.

Then Trend placed a second bet: automotive.

With more than 400 million connected cars predicted to be on roads globally by 2025, Trend announced VicOne, dedicated to security for electric vehicles and connected cars. VicOne offers cybersecurity software and services designed for automotive manufacturers and suppliers, built to match the specialized demands of modern vehicles. As a Trend Micro subsidiary, it draws on Trend’s decades of security experience and threat intelligence.

Regulation added fuel. VicOne aligns with ISO/SAE 21434 and UN R155, which requires automakers to implement cybersecurity management systems and conduct ongoing security monitoring for connected vehicles. In other words: this isn’t “nice to have.” It’s becoming table stakes for selling cars in major markets.

Trend also brought its research credibility into the automotive world through its Zero Day Initiative platform. At Pwn2Own Automotive 2025, Sina Kheirkhah of Summoning Team was crowned Master of Pwn, with researchers from 13 countries discovering 49 unique zero-day vulnerabilities over three days.

According to the forthcoming VicOne 2025 annual report, automotive-related vulnerabilities published in 2024 reached 530—nearly double the level seen in 2019. The rise signals what the industry already feels: the attack surface is growing fast, and the systems are getting more complex. Cyberattacks in 2024 caused damages exceeding $22 billion.

It’s also worth noting the structural choice Trend made here: TXOne and VicOne weren’t just new product lines. They were carved out as focused entities. That gave them room to build specialized teams, pursue their own customers, and move with startup speed—while still leveraging Trend’s threat intelligence and credibility.

X. The Current Crossroads: PE Circling & The Future

As of late 2025, Trend Micro sits at another kind of inflection point—not a platform shift this time, but an ownership and identity question.

Rumors have circulated again that Trend Micro is being eyed for acquisition, roughly six months after reports in August 2024 that the company was potentially exploring a sale.

Reuters reported that Advent International, Bain Capital, EQT AB, and KKR have expressed interest in recent weeks in taking Trend Micro private, valuing the company at approximately JPY 1.32 trillion (about $8.54 billion), citing unnamed sources familiar with the matter.

From a private equity perspective, the appeal is obvious: stable enterprise revenue, a well-known brand, and deep customer relationships. If it happens, it would be among the larger leveraged buyouts in recent months.

But the skepticism is just as clear. One analyst warned that MSPs and resellers relying on Trend’s endpoint and cloud portfolio should prepare for disruption, describing a familiar private equity playbook: cost cuts, management changes, and acquisitions designed to dress up growth before selling the asset again. “Nothing good will come of this,” the analyst said.

Operationally, Trend’s recent financial performance showed strength. In November, Trend said third-quarter net sales rose 6% to 68.1 billion yen, operating income jumped 42% to 14.8 billion yen, and operating margin rose to 24%. Trend also reported fiscal year 2024 results showing 8% and 10% year-over-year growth for the fourth quarter and full year, respectively. Platform adoption drove enterprise net sales up 10% YoY and enterprise ARR up 7% YoY, surpassing $1.3 billion. Operating margin improved to 18% in 2024, with operating income up 48% YoY.

For FY2025, Trend projected consolidated net sales of 288,600 million yen (about $1,874 million) and operating income of 60,300 million yen (about $391 million).

But the market around Trend has gotten even tougher. CrowdStrike, Microsoft, Palo Alto Networks—and increasingly Cisco and Zscaler—are all converging on the same platform-driven buyer. As one analyst put it: enterprises want a more holistic approach, including network-centric detection and response, and the list of competitors Trend faces is broader than it used to be.

Another assessment was harsher: that Trend is losing ground to Microsoft and CrowdStrike on endpoints, and could be surpassed in cloud by Microsoft, Palo Alto Networks, and CrowdStrike by the end of 2025—meaning Trend no longer fits the profile of a public cyber company.

Trend is adapting, especially around AI and partnerships. It extended platform strategy to enhance AI security and protect sensitive data in high-performance computing environments with NVIDIA and GMI Cloud, and it joined the Coalition for Secure AI alongside Amazon, Google, NVIDIA, Microsoft, IBM, and others.

Still, a deal isn’t guaranteed. Sources noted Trend could choose to remain independent, and that its exploration began after receiving acquisition interest in 2024.

So the ending isn’t written. But the through-line is clear: after 37 years, three continents, multiple platform migrations, and a long list of competitor casualties, Trend Micro’s survival instincts are the one thing you should never bet against.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategy Lessons

Lesson 1: The Power of the Tri-Continental Structure

Most technology companies grow from one culture and one base. Trend Micro grew as a three-part organism: U.S. for market access, Taiwan for engineering, Japan for enterprise credibility and sticky revenue.

Being listed in Tokyo gave Trend a unique identity in Asia that U.S.-first competitors couldn’t easily replicate. When Symantec or McAfee sold into Japan, they were American companies with Japanese subsidiaries. Trend was a Japanese company with American operations. In enterprise buying, that difference can decide who gets trusted.

Lesson 2: Founder-Led Durability

Eva Chen has been central to Trend since 1988 and CEO since 2005. Twenty years of CEO continuity is extraordinary in tech, and almost unheard of in cybersecurity. It builds institutional memory, customer trust, and long-term product thinking.

“Our founders have set the tone, the culture, and our road to innovation…”

That kind of continuity means customers aren’t constantly relearning the company’s priorities every time leadership changes.

Lesson 3: Platform Transitions Require Cannibalizing Yourself

From PC to server, server to virtualization, virtualization to cloud, and point products to XDR platforms—each shift threatened the previous revenue base. Trend survived by investing ahead of the curve even when it risked disrupting existing business lines. That’s painful, but it’s the price of staying relevant.

Lesson 4: The OEM/Partnership Model

Trend used partnerships as a force multiplier—Intel royalties, Novell bundling, and later the same posture with VMware and the cloud hyperscalers. Rather than insisting on owning every distribution channel, Trend repeatedly found the dominant platform and aligned with it.

Lesson 5: Adjacency Expansion via Spinoffs

TXOne for industrial environments and VicOne for automotive are adjacency bets with focus. Separate entities can move faster, build specialized capabilities, and even raise outside capital—while still borrowing Trend’s threat research foundation.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces:

1. Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Security software can be built with relatively low upfront capital, but credibility is harder. Trend’s long-standing enterprise track record—such as its repeated Gartner recognition—creates real barriers. Reputation, integrations, compliance, and threat intelligence take years to assemble.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Trend’s key inputs are talent and cloud infrastructure. Hyperscalers are partners as much as suppliers. Talent scarcity is real, but it hits everyone.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Large enterprises can negotiate and switch. The push toward holistic platforms intensifies competitive pressure from vendors Trend historically didn’t face as directly. But switching security systems is still disruptive and risky, which keeps switching costs meaningful.

4. Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Hyperscalers increasingly bundle security into broader enterprise agreements. Microsoft Defender being effectively “free” with Microsoft 365 is a structural threat to standalone security vendors.

5. Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

XDR and endpoint protection are crowded with strong players—Palo Alto Networks, Microsoft, CrowdStrike, SentinelOne, and Trend Micro among them. CrowdStrike has the growth narrative, Palo Alto is consolidating, Microsoft bundles at scale. Trend competes in the middle of all that.

Hamilton's Seven Powers:

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Trend’s global research footprint and ZDI feed threat intelligence into its platform, and more customers generally improves detection. But Microsoft and CrowdStrike operate at even larger scale, limiting Trend’s relative advantage.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Smart Protection Network benefits from aggregated threat data, but enterprise buying doesn’t create the kind of reinforcing adoption loops seen in consumer platforms.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK NOW (was stronger)

Trend’s server-first enterprise focus was once distinct. Now, nearly every major competitor is enterprise-focused.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Security tools are deeply embedded into enterprise environments. Replacement is disruptive and risky, though cloud standardization may reduce friction over time.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Trend’s long-term credibility is meaningful, but newer leaders like CrowdStrike have captured more modern mindshare.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK

ZDI is valuable, but not exclusive in a world with many bug bounty and vulnerability research programs. Talent is mobile.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Decades of institutional knowledge in enterprise security, threat response, and customer operations create real capabilities, even if they’re not patentable.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

For investors tracking Trend Micro’s trajectory, three metrics matter most:

1. Enterprise Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) Growth

In Q4 2024, enterprise ARR grew 7% year over year and surpassed $1.3 billion. ARR is the heartbeat of the enterprise business: it reflects both retention and expansion amid fierce competition.

2. Platform Attach Rate

Trend reported a 37% platform attach rate in the quarter, driven by platform adoption and module expansion. This is the measure of whether customers are consolidating onto Vision One—or staying fragmented across point tools.

3. Operating Margin Trajectory

Operating margin improved to 18% in 2024, and Q3 margin reached 24%. Margin expansion matters both as a sign of operational discipline and because it can raise Trend’s attractiveness to acquirers—without necessarily guaranteeing long-term product investment.

Material Risks & Regulatory Considerations

Private Equity Overhang: With major firms reportedly expressing interest around a potential buyout, uncertainty itself becomes a risk. A PE transaction could introduce cost-cutting, leadership turnover, customer disruption, and talent loss.

Competitive Displacement: Trend faces intense pressure from Microsoft and CrowdStrike in endpoint security and from Microsoft, Palo Alto Networks, and CrowdStrike in cloud. Better-capitalized rivals can outspend and out-bundle.

Currency Risk: As a Japan-listed company reporting in yen with significant global revenue, currency moves can obscure underlying performance.

Hyperscaler Bundling: When security becomes an included feature in broader cloud and productivity contracts, standalone vendors lose pricing power across the industry.

Conclusion

Trend Micro’s story isn’t a tale of meteoric growth. It’s something rarer in tech: durability.

In an industry that has dismantled nearly every early pioneer, Trend has stayed founder-led, consistently profitable, and strategically adaptive—moving from PCs to servers, from servers to cloud, and from point products to platforms.

Eva Chen, co-founder and CEO, summed up the company’s momentum: “Our strong Q4 performance is proof that our enterprise cybersecurity platform is unlocking unprecedented value for our customers, and this is just the beginning.”

Whether Trend remains independent, goes private, or finds a different path forward, the underlying lessons are timeless: diversify across cultures and markets, build distribution through partnerships, keep leadership continuity, and be willing to cannibalize your past to earn your future.

Trend Micro may never be the most exciting stock in cybersecurity. But it has been one of the sector’s stalwarts—and in a business where survival is the exception, that may be the most impressive achievement of all.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music