LY Corporation: Japan's Internet Champion and the Super-App Wars

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s the afternoon of March 11, 2011. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake—the most powerful ever recorded in Japan—hits off the coast of Tōhoku. Cell networks buckle. Calls fail. Texts don’t go through. Families are separated, trying to find one another as a tsunami bears down on the shoreline.

In Tokyo, engineers at NHN Japan, a local arm of South Korea’s internet giant Naver, run into the same problem as everyone else: the usual channels for reaching coworkers and loved ones aren’t reliable. So they do what builders do in a crisis. They start putting together an internet-based alternative—something lightweight, fast, and resilient enough to work when traditional telecom can’t.

Within months, that solution shipped to the public.

It was called LINE.

And from that moment, the story stops being just “a chat app did well.” Because LINE didn’t merely win messaging in Japan—it became a daily habit, then a platform, then critical infrastructure. Combine that with a different Japanese internet icon—Yahoo! JAPAN, the country’s defining web portal from the early days of the consumer internet—and you get LY Corporation: a sprawling ecosystem that touches messaging, media, shopping, advertising, and payments.

Today, LY’s footprint reaches roughly four out of five people in Japan through LINE and Yahoo! JAPAN. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, the company reported revenue of JPY 1.92 trillion, up 5.7% year over year, and operating income of JPY 315 billion, up 51.3%.

But the real hook here isn’t scale for scale’s sake. It’s the ambition behind the consolidation. By integrating these platforms—and the hundreds of services around them—the company set out to build a Japanese internet champion that could stand up to the American giants like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple, the Chinese powerhouses Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, and Japan’s own e-commerce heavyweight, Rakuten.

Structurally, LY is just as interesting as its product footprint. It sits under A Holdings, a joint venture split between SoftBank and Naver. That makes LY a rare experiment in cross-border tech diplomacy: a company that’s deeply Japanese in usage and cultural relevance, but jointly controlled by Japanese and Korean parents—while serving as digital infrastructure for one of the world’s most demanding consumer markets.

That tension sets up the central themes of this story: the Asian super-app playbook, the delicate politics of Japan–Korea tech partnership, the rising importance of data sovereignty as governments scrutinize who controls citizen data, and the perennial challenge of building a national platform in a world dominated by a handful of global incumbents.

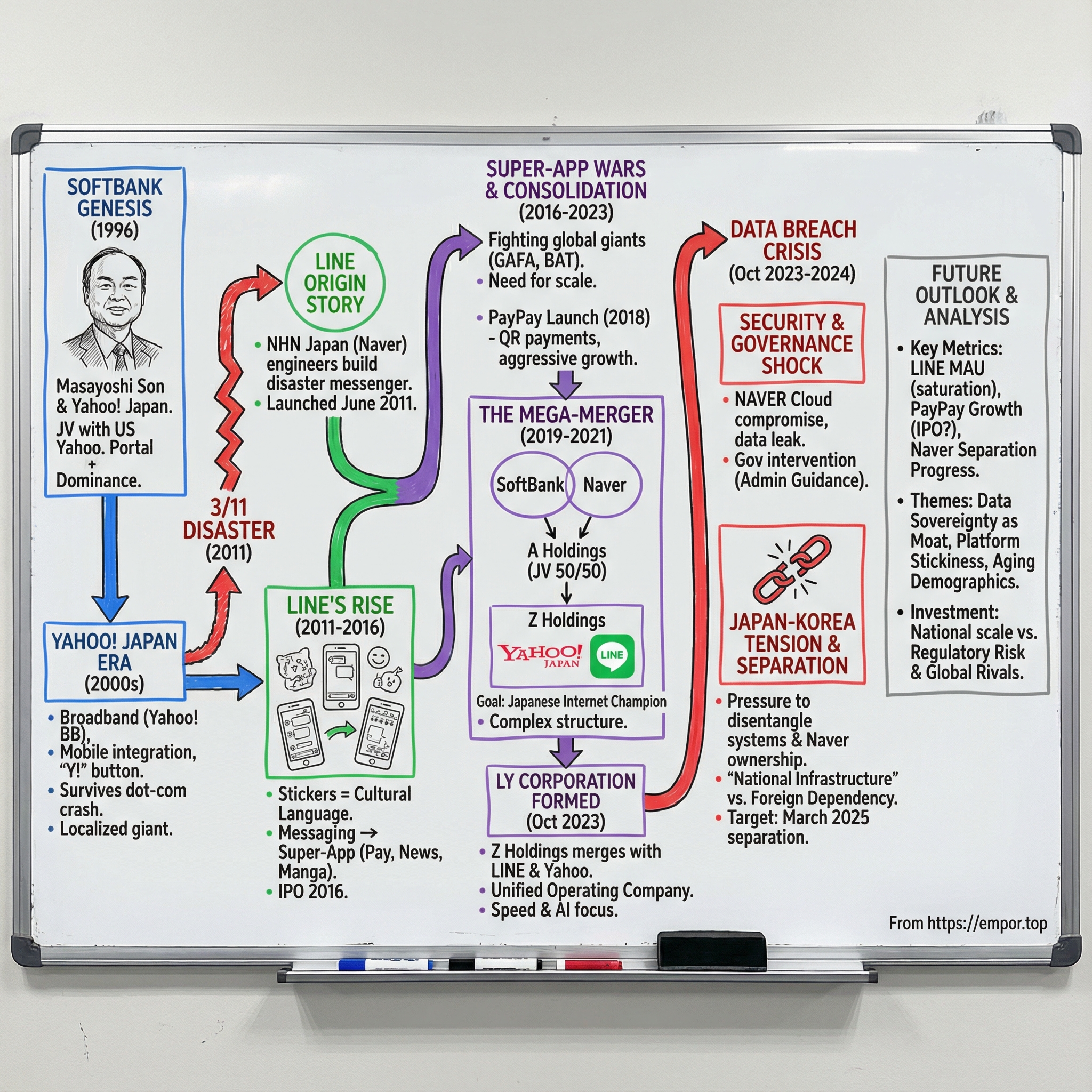

We’re going to move through this saga in four big acts: Yahoo Japan’s founding in 1996 as the country’s first commercial portal, LINE’s birth out of disaster in 2011, the mega-merger that brought the empires together in 2019–2021, and the data-security and governance crisis that has since forced uncomfortable questions about independence, control, and the future of the entire group.

For investors—and really anyone who cares about how the modern internet gets built—LY is a case study in platform economics, regulation, and what it means to become the default layer for everyday life in a wealthy, aging nation.

Let’s dive in.

II. The SoftBank Genesis: Masayoshi Son & Yahoo Japan (1996-2000)

To understand LY Corporation, you have to start with Masayoshi Son—a founder whose life story is equal parts ambition and endurance.

Son was born in 1957 in Tosu, on the island of Kyushu, to a Korean immigrant family. In a Japan where discrimination against Koreans was common, his family adopted the Japanese surname Yasumoto to try to fit in. It didn’t spare him much. Son later recalled being pelted with stones by classmates in grade school.

That experience didn’t just harden him—it gave him a chip-on-the-shoulder drive that shows up everywhere in SoftBank’s history: a determination to win, and a willingness to take swings other people won’t.

At 16, Son met one of his heroes: Den Fujita, the founder of McDonald’s Japan. In a short, 15-minute meeting, Fujita told him to build a career in computers—the future. Son took the advice literally. He left Japan for California.

In the U.S., Son saw the coming wave. A photo of a microchip in a science magazine convinced him that personal computers were about to reshape society. Back in Japan, he built what he believed the country would need: distribution. He launched the first business to distribute PC software nationwide and called it Nihon SoftBank—his “software bank,” meant to be infrastructure for the information age.

Even early on, he wasn’t optimizing for the next product cycle. He was thinking in decades. Son described himself as a visionary; critics called him reckless. The successes that followed earned him comparisons to figures like Bill Gates, Akio Morita, and Soichiro Honda.

Then came the move that set the table for everything LY would later become.

In 1996, SoftBank formed a joint venture with America’s Yahoo to create Yahoo! Japan. This wasn’t just a brand extension. It was Son betting that Japan needed its own front door to the internet—built for Japanese language, Japanese users, and Japanese commerce.

On January 12, the companies held a press conference to announce the launch. Son served as President and CEO, and the team moved fast. By April, Yahoo! JAPAN’s first service was live: the country’s first commercial search engine.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Japan was still working through the economic hangover of the “lost decade,” but internet adoption was taking off. And Yahoo! JAPAN quickly became far more than search. It became the portal—one place where users could start their day and do everything: Yahoo! Weather, Yahoo! News, Yahoo! Mail, Yahoo! Shopping, Yahoo! Auctions, and more.

Investors rewarded it immediately. Yahoo! Japan listed on JASDAQ on November 4, 1997, with an IPO price of ¥2 million per share.

And then it did something that became pure market legend. In January 2000, Yahoo! Japan became the first stock in Japanese history to trade for more than ¥100 million per share. In just a couple of years, it went from IPO to a symbol of the dot-com era’s exuberance. At the peak, it turned early believers into folklore-level winners.

By 2000, the Yahoo! JAPAN portal was pulling in 100 million page views per day. In practical terms, Yahoo! JAPAN wasn’t just a website—it was the internet in Japan.

Of course, bubbles don’t gently deflate. They pop.

When the dot-com crash hit in 2000, SoftBank’s market value collapsed by 93%. Son’s paper wealth evaporated so dramatically that he spent years carrying the grim distinction of having “lost the most money in history”—more than $59 billion during that crash. At one point, he lost $70 billion of what had been a $78 billion fortune in a single day.

Most founders don’t come back from that—financially, psychologically, reputationally.

Son did. He’d already lived through discrimination and hardship, and he treated the crash as another storm to outlast. Yahoo! Japan was still standing. And in Son’s mind, the next platform shift was already obvious.

If the 1990s were about getting Japan online, the 2000s would be about making the internet fast, cheap, and always on.

Broadband was next.

For anyone trying to understand LY today, this early chapter matters because it explains the company’s underlying operating system. Big bets. Platform infrastructure. And a stubborn resilience through crisis. That same DNA will show up again—in SoftBank’s later mobile push, in the decision to merge with LINE, and eventually in the data-sovereignty backlash that comes with being too essential to daily life.

LY, from the beginning, was never built to think incrementally.

III. Yahoo Japan's Dominance: Building the Internet Infrastructure (2000-2010)

The dot-com crash didn’t just vaporize paper wealth. It also cleared the field. A lot of internet hopefuls disappeared. Yahoo! JAPAN didn’t. And Son wasn’t interested in simply rebuilding a portal business—he wanted to turn Yahoo! into something closer to infrastructure.

In September 2001, SoftBank launched Yahoo! BB, an ADSL broadband service designed around a blunt promise: faster internet for less money. It landed because it was hard to ignore—roughly double the speed at about half the price of what many competitors offered.

This was classic Son. Take one position of strength—Yahoo! JAPAN as the country’s default starting point online—and use it to pull users into the next layer of the stack: the connection itself. The pricing was so aggressive competitors accused SoftBank of dumping, selling below cost to wipe out rivals. SoftBank’s response wasn’t subtle. Employees reportedly stood on street corners handing out free modems to anyone willing to sign up. However messy it looked, it worked. Yahoo! BB became one of Japan’s largest ISPs, and the Yahoo brand got even more deeply woven into daily digital life.

Meanwhile, the portal kept expanding into a full suite of essentials. Yahoo! JAPAN was the most visited website in the country, edging toward near-monopolistic status. By the mid-2000s, it felt less like “a website people liked” and more like the default interface for being online in Japan: shopping, auctions, news, mail—services that turned casual visits into habits.

Then SoftBank went after the next platform shift: mobile.

After SoftBank acquired Vodafone Japan in 2006, Yahoo! JAPAN helped make the mobile business work. Before smartphones, Japanese carriers didn’t just sell connectivity—they controlled the experience through their own custom internet portals. SoftBank Mobile leaned into that reality with a simple piece of product design: phones with a dedicated “Y!” button that jumped straight to the Yahoo! Keitai portal.

It was the right move for the era. Japan’s “keitai” culture had already normalized mobile web browsing, purchases, and messaging on feature phones years before the iPhone. Yahoo! JAPAN positioned itself as the gateway.

So when the smartphone wave finally hit, SoftBank didn’t have to start from scratch. It took an audacious swing: becoming the exclusive provider of the iPhone 3G in Japan, released on July 11, 2008. People lined up outside SoftBank shops across the country.

The deal carried real risk. Japan’s incumbents had built their businesses on proprietary handsets and walled gardens, and the iPhone threatened to blow that model up. NTT DoCoMo and KDDI were reluctant to hand that kind of control to Apple. Son wasn’t. He saw the opening and took it—and the payoff was huge. SoftBank’s subscriber base surged, the iPhone became a cultural object, and Yahoo! JAPAN had a clean path onto the new smartphone ecosystem.

By 2010, Yahoo! JAPAN had pulled off a rare feat. It survived the crash, helped build a broadband business, navigated the move from desktop to mobile, and still held onto its position as Japan’s dominant internet portal. In many markets, Google erased the old portal era. In Japan, Yahoo! JAPAN endured.

A big reason was localization and integration. Yahoo! JAPAN wasn’t just a translated version of an American site—it was built around Japanese consumer behavior, business norms, and the shape of the local market. That created real switching costs, the kind you don’t dislodge with a slightly better search box.

And that matters, because the next great Japanese internet platform would win the same way—through local habit and deep integration. It just wouldn’t come from a portal.

It would come from a catastrophe, and it would arrive as a messaging app.

IV. The LINE Origin Story: A Disaster Births a Super App (2011-2016)

March 11, 2011 is one of those dates that doesn’t need context in Japan. A magnitude 9.0–9.1 undersea megathrust earthquake struck off the coast of Tōhoku, lasted about six minutes, and triggered a devastating tsunami. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in the country.

The economic toll was staggering—estimated at $220 billion in damage, making it the costliest natural disaster in history. But the more immediate shock was human: millions lost power, phone lines went down, and the mobile networks that remained were overwhelmed. In the hours when everyone needed to reach everyone else, calls didn’t connect and messages couldn’t get through.

Inside Japan at the time were teams from NHN Japan, the local subsidiary of South Korea’s internet giant Naver. Back home, Naver was often described as Korea’s equivalent to Google: a dominant portal and search engine. NHN Japan ran games and internet services locally. When the earthquake hit, their engineers experienced the communications breakdown firsthand.

Naver/NHN co-founder and chairman Lee Hae-jin later described the spark plainly: in the chaos after 3/11, he kept thinking about a way for employees and families to communicate reliably. And the engineers around him had the same realization. If carrier networks were the bottleneck, the internet could be the bypass.

The technical insight was simple, and it mattered. Even when voice and SMS were jammed, pockets of connectivity still existed—Wi‑Fi in shelters, and some 3G data in places where the network hadn’t fully collapsed. So instead of building on top of carrier infrastructure, they built an app that sent messages over the internet.

Three months after the earthquake, that app launched to the public.

It was called LINE.

LINE debuted in Japan in June 2011, released by NHN Japan. At first it was almost shockingly basic—text messaging and VoIP calling. But the adoption engine wasn’t a clever growth hack. It was memory. An entire country had just lived through the terror of not being able to reach the people who mattered most, and now there was a tool designed for that exact moment.

The result was viral spread at internet speed. LINE reached 50 million users in a little over a year—growth that took Facebook more than three years to approach.

And then LINE found the feature that didn’t just make it useful. It made it culturally native.

Stickers.

A few months after launch, in October 2011, LINE introduced stickers: big, expressive, often animated illustrations that could carry tone and emotion more vividly than text—and more playfully than standard emoji. In a high-context communication culture, that mattered. Stickers weren’t decoration; they were language.

They also became a business model. LINE stayed free at the core and monetized around it—selling sticker packs featuring anime characters, Disney properties, and LINE’s own mascots like Brown the bear. Over time, the sticker ecosystem became its own economy, with creator-driven content and merchandising expanding the brand far beyond the app.

That creator angle turned out to be rocket fuel. In 2014, LINE opened the door for users to design and sell their own stickers through Creators Market. It transformed stickers from a product LINE sold into a marketplace LINE ran—one where artists could build real income and, in some cases, become breakout successes.

But the bigger strategic move was what LINE became next.

Messaging was the wedge. Habit was the moat. And once LINE owned daily communication, it could pull other services into the same orbit. What started as chat and calling steadily expanded into a super-app: a digital wallet (Line Pay), a news stream (Line Today), video (Line TV), and comics (Line Manga and Line Webtoon), alongside other features like music and even securities investment. LINE stopped being “an app you open” and became “where life happens.” Businesses and governments used it too, building custom interfaces to communicate with citizens and customers.

By 2016, LINE was big enough—and central enough—to go public. LINE Corporation executed a dual listing: New York Stock Exchange on July 14, 2016 (EDT), and the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange on July 15, 2016 (JST).

The debut was explosive. Shares surged in Tokyo, valuing the company at about $8.6 billion in what was the year’s biggest tech IPO. In total, the dual listing raised more than $1.1 billion, and the New York listing opened at $42, up 33% from its offer price. Symbolically, listing in New York first was widely read as a statement: LINE wasn’t just a Japanese success story. It wanted to play on the global field.

But the celebration masked two constraints that would define the next chapter.

First, control. Even after the IPO, LINE remained controlled by Naver, whose stake stood at 80.8%. That foreign ownership would later become a flashpoint in Japan—especially once LINE became embedded in everything from commerce to public services.

Second, scale. Globally, LINE was huge, but not huge enough. Its 218 million monthly active users were impressive—and still a fraction of WhatsApp’s billion and Facebook Messenger’s 900 million. WeChat dominated China with hundreds of millions more. LINE’s super-app model worked brilliantly in its core markets—Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, and Indonesia—but it struggled to break out beyond them, especially in Western markets where users tended to prefer single-purpose apps.

Still, the origin story explains why LINE became so hard to displace at home. It wasn’t built as a vanity product or a marketing campaign. It was built as a practical response to a national emergency. That kind of beginning creates trust, and trust creates habit—and habit is what turns a messenger into infrastructure.

By 2025, LINE had 97.0 million monthly active users in Japan, equivalent to 78.6% of the country’s total population.

But even that kind of dominance wasn’t enough to take on the global giants alone.

To do that, LINE would need something bigger than a messenger. It would need an empire to merge with.

V. The Super-App Arms Race: Fighting GAFA and BAT (2016-2019)

By 2016, the board was set. In the U.S., Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple had become the default rails of the consumer internet. In China, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent ran a parallel universe at national scale. And in Japan, even the winners—Yahoo! JAPAN and LINE—were starting to look like regional champions in a world that increasingly rewarded only the biggest platforms.

That was the fear: not just “we can’t win abroad,” but “we could lose at home.” As Google and others expanded, they weren’t just competing on products. They were collecting data across search, maps, ads, video, commerce—everything. And in a data-driven internet, whoever learns fastest improves fastest.

Put plainly, Japan’s internet was too fragmented to fight company-by-company. Yahoo! JAPAN and LINE had huge reach by Japanese standards. But compared to the two-billion-user ecosystems of the American giants, they were swimming in a different ocean. Same story on R&D: Yahoo! JAPAN and LINE could invest, but they couldn’t match the budget gravity of GAFA. One GAFA executive reportedly dismissed the idea of a Yahoo! JAPAN–LINE combination as “too small in scale to care about.”

That kind of comment stings, but it also clarifies the mission. If size is destiny—if scale drives AI, data advantage, talent, and platform economics—then Japan needed consolidation.

And before the headline mega-merger that would eventually create LY Corporation, SoftBank and Yahoo! JAPAN made a crucial move in a different arena: payments.

SoftBank and Yahoo! JAPAN announced they would launch a new smartphone payment service, PayPay, using barcodes and QR codes in the fall of 2018. To do it, they established PayPay Corporation in June 2018. The pitch was straightforward: make cashless payments feel effortless for consumers and worth it for merchants, and push Japan toward a future it had oddly resisted.

Because Japan, for all its hardware sophistication, was still a cash country. The opportunity wasn’t theoretical—it was sitting in plain sight every time someone paid at a register.

PayPay went after that opportunity the SoftBank way: move fast and buy adoption. The company leaned on aggressive promotions that effectively paid users to try mobile payments, then tried to convert that trial into habit.

The technology foundation mattered too. PayPay’s QR and barcode-based service, launched in October 2018, was developed in collaboration with Paytm, the India-based payments company. That relationship wasn’t random. SoftBank’s Vision Fund had made major bets in Paytm, and here was another Son pattern: import a proven playbook, then scale it hard in a new market.

PayPay’s growth quickly turned it into a central asset in the emerging ecosystem. It reached 38 million users and became Japan’s largest mobile payment app.

At the same time, Yahoo! JAPAN was reshaping itself for what came next. In 2019, the company shifted to a holdings-company structure and changed its corporate name to Z Holdings Corporation.

That wasn’t just a rebrand. It was corporate choreography—creating flexibility for deals, acquisitions, and integration, while separating the consumer-facing Yahoo! JAPAN identity from the entity that could combine with other platforms. Even the name felt like a tell: “Z,” the last letter, positioned as a final form—something built to gather everything under one roof.

By the end of this period, the logic of the next step was hard to miss. Yahoo! JAPAN had reach, commerce, and media. LINE had messaging and daily engagement. PayPay was becoming a wallet that could bind the whole thing together. Japan didn’t just need good products. It needed a single platform constellation big enough to matter.

The stage was set for consolidation.

VI. The Mega-Merger: LINE + Yahoo Japan (2019-2021)

In November 2019, the inevitable finally got put on paper. SoftBank Corp. and Naver agreed to merge Z Holdings (the company that housed Yahoo! JAPAN) with LINE Corporation—and to do it through a brand-new holding company called A Holdings.

Here was the core idea: instead of one side buying the other, SoftBank and Naver would each own 50% of A Holdings. A Holdings, in turn, would control the combined empire—LINE and the major assets inside Z Holdings. It was a merger designed to create a Japanese internet champion, while preserving a delicate balance of power between a Japanese telecom-and-investment giant and a Korean internet titan.

The announcement was both expected and surprising. Expected, because the strategic logic was obvious: Japan’s dominant portal plus Japan’s dominant messenger equals unprecedented reach, data, and distribution. Surprising, because the corporate choreography was dizzying. A Japanese company controlled by SoftBank combining with a Japanese company controlled by Naver meant the new “national champion” would be, by design, jointly governed across borders. That governance would later become more than a boardroom issue—it would become a political one.

The companies framed the move as a direct response to the super-app arms race. The merger, they said, was about competing with the American and Chinese giants—platforms with more users, more compute, more data, and more money to spend on AI than any single Japanese player could match. The plan was to complete the deal in 2020.

The press conference was, in classic Japanese corporate fashion, meticulously staged. Z Holdings CEO Kentaro Kawabe talked about ambition—“We want to become an AI tech company that leads the world from Japan.” Visually, the message was unity: Kawabe wore a bright green tie in LINE’s signature color, while LINE co-CEO Takeshi Idezawa wore one in Yahoo Japan red.

But beneath the symbolism, there was a rare amount of candor. The CEOs openly described a sense of crisis: global platforms were tightening their grip on the internet, and the “winner-takes-all” dynamics meant the strong would likely get stronger. Idezawa put it bluntly: even together, their market value, scale, and R&D budgets were still dwarfed by the global tech giants.

To make the merger work structurally, the deal had to get even more complicated. LINE would be taken private: the plan was to acquire all outstanding LINE shares, options, and convertible bonds. Z Holdings would remain public, but with Yahoo! JAPAN and LINE operating as wholly owned subsidiaries beneath it. And the tender offer for LINE’s remaining shares was set at 5,200 yen—a premium over the prior closing price.

That premium captured something important about leverage in this negotiation. Yahoo! JAPAN had reach, media, commerce, and advertising. But LINE had the most valuable thing in consumer internet: the front pocket relationship. For a huge share of Japan, LINE wasn’t an app—it was the default channel for talking to the people who mattered. Z Holdings didn’t just want LINE’s revenue. It wanted that daily habit.

The strategic rationale went beyond Japan, too. The combined company would get immediate exposure to LINE’s other strongholds in Asia—Taiwan, Thailand, and Indonesia—and during negotiations both sides talked about strengthening the platform at home first, then expanding outward.

On paper, the synergies were obvious. In practice, they were messy. The two groups had overlapping services everywhere you looked: payments, news, e-commerce, and finance. SoftBank’s orbit already included PayPay. LINE had LINE Pay. Yahoo! had its own wallet services. They were simultaneously partners and competitors, and the merger promised cost savings by reducing duplication—like subsidies in payments—while pooling engineering and accelerating investment in AI.

Then there was the governance bet: the 50/50 ownership structure. It looked elegant, like a true partnership. But it also created built-in ambiguity. When everyone owns half, no one is fully in charge—and that can be a feature in peacetime and a bug in a crisis.

By March 2021, the integration moved forward under the new structure. SoftBank and Naver each held 50% of A Holdings, and A Holdings held a majority stake in Z Holdings—the public company that operated Yahoo! JAPAN and LINE as core subsidiaries.

For investors, this was the paradox of the deal: extraordinary reach wrapped in extraordinary complexity. The integration challenges were predictable—two giant ecosystems, duplicated products, and years of technical debt—but there was a deeper risk embedded in the structure itself. The combined organization inherited a sprawling technology footprint, stitched together across companies, countries, and systems.

And that sprawl didn’t just make execution harder.

It made the attack surface bigger.

That detail would matter a lot sooner than anyone wanted.

VII. LY Corporation: The Final Merger (2023)

For the two years after the 2021 deal closed, Z Holdings was essentially a federation. LINE Corporation and Yahoo! JAPAN sat underneath it as separate subsidiaries, each with its own history, systems, and ways of working. That kept the peace during the transition—but it also meant many of the promised synergies stayed stuck on slides. Too many decisions still had to travel through too many corporate layers, and overlapping teams often ended up solving the same problems twice.

By 2023, Z Holdings was ready to collapse the org chart. The company announced it would merge with its wholly owned subsidiaries—Yahoo! JAPAN and the messaging giant LINE—to revamp operations and speed up decision-making.

On October 1, 2023, Z Holdings merged with four subsidiaries—LINE Corporation, Yahoo! Japan Corporation, Z Entertainment Corporation, and Z Data Corporation—to form a single operating company: LY Corporation.

The timing mattered. If the 2019–2021 mega-merger was about scale, the 2023 merger was about speed. The company wanted to move faster on AI and personalization, where execution depends on tight coordination across products and data. The holding company structure had done its job; now they needed one company that could actually act like one.

The new name was a tell. “LY” fused the two legacy crowns—L for LINE, Y for Yahoo. But it was also meant to signal a fresh identity: not “Yahoo with LINE attached,” and not “LINE with a portal,” but a unified platform that could design services end-to-end across communication, media, commerce, and payments.

And they didn’t waste time trying to prove the point. The AI ambition was real. By the end of 2024, LY had implemented 32 AI-driven use cases aimed at boosting engagement and reducing friction in everyday interactions. That showed up in features like AI-generated summaries in Yahoo! JAPAN Search and AI talk suggestions in LINE—small touches, but the kind that compound when you control both the front door (search and news) and the conversation layer (messaging).

Financially, the early read on the unified structure was encouraging. In the fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, LY reported revenue of 1,917.4 billion yen, up 5.7% year over year, and adjusted EBITDA of 470.8 billion yen, up 13.5%—record highs for the fifth consecutive year. The growth was driven by stronger results in Strategic, helped by PayPay (including PayPay Corporation and PayPay Card Corporation), and by Media, where account ads continued to expand.

For investors, the reorganization also made the story easier to underwrite. LY now presented itself through clearer business lines—Commerce (including ZOZOTOWN), Media (advertising across LINE and Yahoo surfaces), and Strategic (PayPay and financial services)—with distinct growth engines and accountability.

Commerce remained the biggest piece. In FY2024, it generated JPY 848.3 billion in revenue, up 2.6% year on year.

But even as the company finally simplified its structure and sharpened its narrative, a different kind of integration problem was about to explode—one that had nothing to do with product overlap or org charts, and everything to do with trust.

A crisis was brewing that would threaten to unwind the Japan–Korea partnership at the heart of LY Corporation.

VIII. The Data Breach Crisis: A Turning Point (2023-2024)

LY Corporation officially came into being on October 1, 2023. Eight days later, an intruder was already inside.

In the breach notification letters LY sent to affected individuals, the company said the intrusion occurred on October 9 and was detected on October 17, 2023. LY’s investigation concluded that attackers first compromised a South Korea-based affiliate, NAVER Cloud, after malware infected a subcontractor employee’s computer. From there, the attackers exploited a shared personnel-management environment and common authentication—exactly the kind of “convenience link” that looks harmless on an org chart and catastrophic in a post-incident report.

The scope was sobering. LY disclosed that 440,000 items of personal data were leaked, including users’ age group, gender, and partial service usage histories. The incident also exposed about 86,000 data items related to business partners—email addresses, names, and affiliations—and more than 51,000 employee records.

But the bigger story wasn’t just the count. It was what the incident revealed about how the Japan–Korea partnership actually functioned under the hood.

Japanese regulators seized on the same conclusion: the merged organization had leaned too heavily on Naver’s technology. The ministry’s analysis criticized the cybersecurity practices and architecture connecting LINE and Naver, including a shared Active Directory and what it described as NAVER Cloud’s extensive access into LINE’s network.

The ministry’s guidance also laid out the failure mode in plain language. Authentication services had been shared in a way that left former LINE staff information inside a shared Active Directory. Some of those former staff later returned as contractors. Attackers obtained unauthorized access to credentials through NAVER Cloud, and NAVER did not detect the intrusion—meaning LINE had no warning it was exposed until after the fact.

Then the response escalated—fast, and in a very Japanese way.

This wasn’t treated as a routine cybersecurity remediation plan. It became a question of national infrastructure. After the breach, Japan’s government ordered LINE and NAVER to disentangle their systems, following an incident that exposed data for more than 510,000 users. In March 2024, the Japanese government ordered LINE and Naver to separate their systems, and Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications issued administrative guidance to LY Corporation twice on April 16, 2024.

That guidance was unusually pointed. It criticized information-security practices and governance at both LINE and NAVER, demanded a comprehensive review, and required quarterly progress reports. It also pushed a clear technical outcome: LINE should disentangle its technology from NAVER and keep only minimal essential connections. Separate authentication had to be implemented. The shared Active Directory had to go.

And then came the part that made this bigger than cybersecurity.

The ministry’s guidance went beyond systems and into structure, effectively raising the question of whether a Korean company should remain a co-owner of such a central piece of Japanese digital life. The situation escalated to the point where, in March, Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications began pushing for Naver to sell its stake in A Holdings. If SoftBank were to acquire an additional stake in A Holdings, it would control LY.

At that point, it stopped being a corporate issue and started looking like a diplomatic one. Industry officials said the Line Yahoo–Naver issue had escalated into a Japan–Korea diplomatic matter, making it difficult for the companies to navigate. In mid-May, Seoul’s presidential office said it would respond resolutely if Tokyo took any “unfair” measures against Naver.

The South Korean government emphasized it was in close contact with Naver amid Japan’s apparent attempt to exclude the company from joint management of LINE. “We have been continuously communicating and cooperating with Naver since the end of last year. We respect Naver’s managerial decisions and are providing support and communication. What is most important is ensuring that our companies do not suffer disadvantages when they invest or conduct business overseas.”

LY’s own response signaled just how seriously it took the pressure. Japan’s LY Corp., operator of LINE, said it planned to sever technological and system ties with Naver Corp. by the end of the year—accelerating a timeline it had previously set for 2026. At a shareholders’ meeting, CEO Takeshi Idezawa said, “We now aim to complete our system separation with Naver Cloud by the end of this year. We expect to end our relationship with Naver in almost all services in Japan.”

Industry watchers noted that this kind of separation typically takes years, and that moving to do it in roughly half a year looked like a message as much as an implementation plan—a way to demonstrate resolve to the Japanese government.

LY has also stated it is undertaking a fundamental separation of its systems and network connections from Naver and Naver Cloud by the end of March 2025, and that this effort includes reviewing its capital ties with Naver.

For investors, this incident repriced the entire risk profile of the company. The 50/50 ownership structure that looked elegant in 2019 suddenly looked fragile in 2024. In effect, Japanese officials were treating a Korean co-owner as an unacceptable dependency inside critical Japanese infrastructure.

And the implications don’t stop at LY. As more governments treat data control as a national-security issue—echoing debates in the U.S. over TikTok—cross-border tech ownership faces a sharper test. Observers drew comparisons between Japan’s “administrative guidance” and U.S. legal action forcing a sale or ban of a Chinese-controlled app, arguing Japan needs more agile legislation to protect user information and establish data sovereignty.

As of late 2025, the ownership question still wasn’t fully resolved. Naver—an equal partner with SoftBank in the joint venture that controls LY—apologized for the security breach that prompted Japan’s administrative guidance, saying it would “continue to put top priority on Naver shareholders and on raising the corporate value of Naver and LINE Yahoo.”

The crisis was still moving. And for anyone trying to understand LY’s future, the checklist now runs beyond product execution and quarterly results. It includes Tokyo–Seoul relations, evolving regulatory demands, and whether LY can actually deliver on the hard promise it just made: to untangle a cross-border, deeply interwoven tech stack—without breaking the very services that made it indispensable in the first place.

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Lesson 1: The Super-App Thesis in Asia

Super-apps didn’t “win” in Asia because Asian consumers are somehow more open to bundling. They won because the market conditions made bundling the path of least resistance.

When LINE arrived, Japan already had a long history of feature phones that felt like miniature ecosystems—messaging, games, payments, and content all living behind carrier portals. So when smartphones took over, the natural evolution wasn’t “download fifteen apps.” It was “move the old integrated life onto a new device.” LINE slotted perfectly into that transition: first as the place you talked to people, then as the place you did more and more.

Over the next decade, LINE entrenched itself in Japan much like KakaoTalk did in South Korea and WeChat did in China, while also becoming a mainstream daily app in markets like Thailand and Taiwan.

The West evolved in the opposite direction. App stores made it frictionless for specialized apps to bloom, and consumer habits formed around best-of-breed tools: WhatsApp for messaging, Venmo for payments, Amazon for shopping, Instagram for social. Once those habits set, it became brutally hard for any one app to credibly replace the whole bundle.

The investor takeaway is straightforward: LY’s realistic growth runway is mostly inside the footprint it already owns. The upside is less about conquering new geographies and more about deepening monetization in Japan—where LINE and Yahoo! JAPAN already sit at the center of everyday behavior.

Lesson 2: Merger Integration Complexity

The breach put a spotlight on an uncomfortable truth about “synergies”: integration often happens faster on the org chart than it does in the architecture.

SoftBank and Naver didn’t join forces to create a spreadsheet. They were trying to assemble an Asian tech heavyweight. But the combined organization leaned heavily on Naver’s technology, and the shared Active Directory at the center of the incident is a textbook example of an integration shortcut—keeping connective tissue in place because it’s expedient, even when it blurs security boundaries that should never be blurred.

If that shortcut existed in authentication, it’s reasonable to assume other shortcuts existed elsewhere, too. And in a business as sprawling as LY—with hundreds of services and multiple legacy stacks—every shortcut increases the attack surface.

The lesson for anyone evaluating tech mergers is that “integration” isn’t branding and reporting lines. It’s rebuilding the underlying systems so they operate with clean separations, modern controls, and clear ownership. That work is expensive, slow, and unglamorous. But the alternative can be far more costly—financially, operationally, and politically.

Lesson 3: Data Sovereignty as Competitive Moat

Japan’s response revealed what LINE had quietly become: infrastructure.

LINE is the country’s dominant communication app, with a user base in the tens of millions. Yes, it was developed under a South Korean parent. But its Japanese identity was forged in the aftermath of 2011, when people learned—in the most visceral way—that an internet-based messenger could be the difference between silence and contact.

When a platform is used not just for chatting, but for government notifications, disaster communications, healthcare-related touchpoints, and payments, it stops being “just a company.” It starts looking like critical national plumbing. And once you’re plumbing, regulators don’t just care whether you grow—they care who controls you, where the data sits, and how dependent your systems are on overseas affiliates.

That creates a double-edged dynamic. The risk is obvious: regulatory intervention, ownership pressure, mandated system separation. But there’s also protection in becoming essential. Companies that reach infrastructure status in wealthy countries often end up operating behind new kinds of moats—rules and norms that make it harder for foreign competitors to displace them, even if those competitors are bigger globally.

Lesson 4: Platform Stickiness Through Necessity

LINE didn’t stay dominant because it had the best features. It stayed dominant because it became a default behavior—and then wrapped itself around daily life.

Payments, news, official accounts, business communications, public institution outreach: all of that widened LINE from “messenger” into “utility.” It kept the app relevant across ages and use cases, and it ensured that opting out didn’t just mean losing a chat thread. It meant losing access to how your workplace, your city, your child’s school, or your favorite stores communicate.

But the deepest moat is emotional, not functional. LINE’s origin as a tool that worked when other channels didn’t created trust competitors can’t manufacture. During a crisis, reliability imprints. Years later, that imprint becomes switching cost.

For investors, the point is to look beyond downloads and monthly active users and ask a harder question: how painful is replacement? A platform people use reflexively, for critical communication, in coordination with institutions, is a fundamentally different asset than one competing primarily on features or price.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

By 2025, LINE had effectively locked up Japan’s messaging layer, with roughly 97 million monthly active users. Engagement wasn’t just high; it was habitual—on Android devices, people opened LINE hundreds of times a month. That kind of frequency matters, because it turns “an app” into a reflex.

Messaging is one of the clearest examples of network effects in the consumer internet. You don’t pick a messenger because it’s marginally better. You pick it because everyone you care about is already there. Which means a challenger doesn’t just have to build a better product—it has to convince entire social graphs to move together. With LINE at near-saturation in a country of about 123 million people, that’s an almost impossible coordination problem.

The barrier gets even higher when LINE becomes institutional. Municipalities using LINE for emergency notifications and healthcare services aren’t just choosing a channel—they’re embedding it into public workflows. A new entrant would have to replicate not only features, but trust, compliance, and years of integrations.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

If the breach chapter taught anything, it’s that infrastructure dependencies become leverage. The fact that a compromise of NAVER Cloud could cascade into LINE’s environment highlighted real supplier power—especially when systems, authentication, and operations are intertwined across company boundaries. LY’s urgent push to separate from Naver systems underscored that this wasn’t a theoretical dependency; it was an operational one.

AI is the other supplier story. By the end of 2024, LY had rolled out 32 AI-driven use cases across its platforms. As AI shifts from “nice-to-have features” to core product differentiation, whoever provides the models, compute, and tooling holds more negotiating power—whether that’s internal teams or external partners. The more LY’s products depend on AI, the more strategically sensitive those relationships become.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW TO MODERATE

For individual users, bargaining power is close to zero. LINE is free, and switching doesn’t look like “download a new app.” It looks like “convince your friends, family, workplace, and local institutions to come with you.”

But LY doesn’t get paid by most users. It gets paid by advertisers, and advertisers do have options. Digital advertising is crowded and performance-driven, with Google and Meta setting the benchmark and plenty of other channels competing for budgets. Yahoo! JAPAN’s advertising business has to win on measurable outcomes—price, targeting, and conversion—not just audience size.

Enterprise customers sit in the middle. Businesses using LINE Official Accounts do get meaningful value from the channel, but they also have alternatives for reaching customers. With more than 3 million active Official Accounts in Japan, that base is both a revenue engine and a reminder: if pricing gets out of line or the product degrades, some portion of that activity can shift elsewhere.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

In pure messaging, substitutes exist, but network effects blunt them. The real substitution pressure shows up in the “super-app” perimeter—every additional vertical LY enters is another arena where best-of-breed specialists can take shots.

PayPay competes with alternatives like Rakuten Pay, Suica, and credit cards. Yahoo Shopping runs into Amazon Japan and Rakuten. News competes with traditional publishers and global platforms. And across entertainment and content, specialized players can focus all their resources on doing one job better while LY spreads attention across dozens of services.

That’s the trade-off of the super-app strategy: it creates ecosystem value, but it also means you’re never in just one fight.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry is intense across almost every category LY touches. In e-commerce, Amazon Japan and Rakuten are relentless. In search, Google holds significant share despite Yahoo! JAPAN’s legacy dominance. In payments, competitors like Rakuten Pay, Merpay, and traditional financial institutions contest PayPay’s position.

Japan’s market does offer one advantage: global giants don’t always localize perfectly. But that doesn’t reduce rivalry—it just means much of the fiercest competition comes from strong domestic players who understand local behavior as well as LY does.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: LY benefits from scale in advertising, infrastructure, and content distribution. A larger audience can improve targeting, and fixed costs spread more efficiently. The catch is that these scale benefits are real but still smaller than what the largest global platforms can bring to bear.

Network Effects: This is the crown jewel. LINE’s network effects are brutally hard to attack. People join because their contacts are there, and they stay because the network is there. In messaging, that loop becomes a wall.

Counter-Positioning: LY’s super-app approach is a form of counter-positioning—an integrated ecosystem versus single-product specialists, and a domestically tuned platform versus globally standardized ones. It has worked far better inside Japan than as an exportable model.

Switching Costs: Beyond the social graph, LINE stacks practical switching costs: Official Accounts that businesses would need to rebuild elsewhere, PayPay points and linked payment setups, and content purchases like stickers and subscriptions. Any one of these is small. Together, they add up to real friction.

Branding: LINE and Yahoo! JAPAN are not just well-known; they’re culturally embedded. LINE’s characters and sticker culture helped turn a utility into a brand people feel. That translates into trust and lower customer-acquisition cost relative to newcomers.

Cornered Resource: LY’s most valuable cornered resource is the depth of its relationship with Japanese consumers. Across communication, shopping, and payments, the company touches an unusually broad slice of daily life, generating data that can power personalization and targeting at a scale few domestic competitors can match.

Process Power: This is the weak link. The merger integration period and the breach exposed gaps in governance, security boundaries, and execution discipline. Until those processes mature—especially around systems separation and risk management—process power won’t be a reliable moat.

Competitive Dynamics

Put it together and you get a company with an exceptionally strong position in messaging and engagement, and more contested ground everywhere else. LY is at its best when it can leverage the ecosystem—using one surface to drive another, and the wallet to bind it together. It’s at its most vulnerable in domains where global scale matters most, like AI infrastructure and cloud, and in verticals where specialists can out-focus an integrated platform.

Against Rakuten, LY has clear advantages in messaging and media distribution, but it faces a more concentrated e-commerce competitor. Against the global giants, LY’s edge is local tailoring and institutional embed—while the giants’ edge is unmatched investment capacity in AI, cloud, and hardware.

XI. Key Metrics to Watch

If you’re tracking LY Corporation from here, you can ignore most of the noise and keep your eyes on three signals that tell you whether the flywheel is still spinning—and whether the biggest risk overhang is actually clearing.

1. LINE Monthly Active Users in Japan

LINE had 97.0 million monthly active users in Japan in early 2025. LINE’s own advertising guides show that base grew by about 1 million between January 2024 and the start of 2025.

At this point, Japan is close to tapped out. So the story isn’t “can LINE add more users?” It’s “can LINE avoid losing them?” Any meaningful decline would be an early warning sign. Just as important is engagement per user—how often people open the app, how long they spend, and how much they message. In a saturated market, engagement is the real growth lever.

2. PayPay User Growth and Transaction Value

By mid-2025, PayPay reported more than 70 million registered users and over 4 million participating merchants. It processed billions of transactions a year across everyday categories like retail, dining, transportation, and utilities.

This is LY’s clearest growth engine. The key is not just sign-ups, but the mix of registered users versus active users, the pace of transaction value growth, and the path to profitability. SoftBank’s FY2024 investor materials described PayPay as “approaching break-even on a consolidated basis” after years of heavy incentives to buy adoption.

The other looming catalyst is the planned PayPay IPO. That will put a public-market valuation on the asset and force more disclosure. Investors have floated valuations in the multi-trillion-yen range, with 2 trillion yen often framed as a baseline and expectations that it could go higher.

3. Naver Separation Progress and Ownership Evolution

This is the one that can’t be modeled cleanly in a spreadsheet. The regulatory and geopolitical risk tied to Naver’s 50% ownership still hangs over the entire group. So watch the quarterly updates on system separation, any movement in the ownership structure, and the temperature of Japan–South Korea relations around the issue.

LY has said it aims to complete system separation from Naver by March 2025. If that slips—or if the technical reality proves harder than the commitment—regulators may escalate again. If the separation actually lands, it removes a major overhang and lets the investment case return to what it was supposed to be: execution, monetization, and platform leverage inside Japan.

XII. Bull and Bear Cases

Bull Case

LY Corporation sits on top of something incredibly rare: Japan’s everyday digital rails. LINE reaches roughly four out of five people in the country, and PayPay has become the default on-ramp for mobile payments. In a wealthy market where trust and habit matter more than novelty, that kind of position is hard to replicate—and even harder to dislodge.

The planned PayPay IPO adds a second catalyst. PayPay reported 68.38 million users and 347% EBITDA growth in FY2024, and taking it public would give the group more financial flexibility and a clearer market price for one of its most important assets. If the IPO lands at a $20+ billion valuation, it would crystallize a lot of value that’s currently bundled inside LY.

The next tailwind is simply that Japan still pays like it’s 2005. Cashless payments only recently cleared 40%, far behind South Korea and China at 80%+. If Japan keeps moving toward that level, PayPay’s opportunity doesn’t need to be invented—it expands naturally with the country’s behavior. In that world, PayPay’s addressable market doesn’t inch forward; it effectively steps up.

Then there’s AI. LY has a uniquely Japanese dataset spanning communication, media consumption, shopping intent, and payment behavior. If it can turn that into better personalization—ads that perform, search that answers, shopping that converts—it can create product advantages that global competitors can’t easily localize from the outside.

Finally, the breach, paradoxically, could end up strengthening the story long term. A painful security event tends to force the unglamorous work to finally get funded and finished. If system separation from Naver is completed, LY clears a major governance overhang and moves toward simpler, more clearly Japanese-controlled infrastructure.

Bear Case

The biggest risk isn’t a competitor—it’s the state. Regulatory and geopolitical pressure remains elevated, and government scrutiny of the Naver relationship could force changes that aren’t optimized for business performance. If LY has to accelerate separation faster than its engineering reality allows, costs go up and execution risk rises.

At the same time, LY fights heavyweights in every arena it touches. Amazon keeps taking e-commerce share. Google remains the default in search. Meta’s platforms pull younger users’ attention. Each of these players can focus on one core business while LY has to spread capital and management attention across a broad ecosystem.

LINE, meanwhile, is at saturation. From October 2024 to January 2025, active users were basically flat. That’s not a crisis—but it changes the growth equation. If the user base can’t expand, revenue growth has to come from better monetization, which is harder work than simply adding new users.

PayPay is another two-sided risk. Yes, it’s scaled fast—but much of that scale was bought with aggressive promotions and subsidies. The open question is whether PayPay’s unit economics hold when incentives normalize, especially as competition in cashless payments stays intense.

And then there’s the slow-moving headwind you can’t promo your way out of: Japan’s demographics. An aging, shrinking population means fewer users over time. LY’s strength is also its concentration—Japan is the core of the business—but that focus leaves little diversification against a structural decline in the home market.

XIII. Investment Considerations

LY Corporation is a rare public-market package: a platform company with real network effects, operating at national scale, while also sitting directly in the path of regulation and geopolitics.

On the upside, the strengths are hard to argue with. LINE is the default messaging layer in Japan. PayPay has become a leading mobile payments on-ramp. And across LINE and Yahoo! JAPAN, LY is woven into everyday routines—communication, news, shopping, and advertising—creating the kind of habit and switching costs that most consumer tech companies can only dream about. Layer on decades of accumulated data, and you can see why management keeps pushing the “Japanese champion” narrative: if you’re going to build an ecosystem that can defend itself, this is what it looks like.

But the risks are just as real—and they’re not the kind you can fix with a better feature roadmap. The governance structure still ties the company to Naver, and that connection has already triggered unusually direct intervention from the Japanese government. Competitive pressure also doesn’t go away just because LY is big domestically. In search, e-commerce, and advertising, it’s still up against global giants and focused local rivals. And over everything sits Japan’s demographic reality: a mature, aging market where growth increasingly has to come from monetization and efficiency, not new users.

In the market today, LY carries a market capitalization of $21.3B and trailing twelve month revenue of $12.6B. The stock trades at relatively modest multiples versus global tech peers—partly because many of its businesses are mature, and partly because the ownership and regulatory overhang is still very much unresolved. The core underwriting question is simple: does that discount truly compensate you for the unique political and operational risks that come with being national infrastructure?

If you’re watching for what could change the narrative, the catalyst list is clear. The PayPay IPO—both timing and valuation—could crystallize value and reset expectations. The system separation from Naver, targeted for March 2025, is the other big one; it’s not just a cybersecurity milestone, it’s a test of whether LY can actually untangle critical systems without damaging service quality. And then there are the signals you can track every quarter: engagement trends on LINE, adoption and usage intensity on PayPay, and any concrete movement in ownership restructuring.

For long-horizon investors, LY is a bet on Japan’s ability—and willingness—to keep domestic control over its digital rails, and on management’s ability to execute while regulators are actively rewriting the boundaries of what “acceptable” ownership and infrastructure look like. The opportunity is enormous. The question is whether the company can earn the right to capture it before politics forces the structure to change on someone else’s timeline.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music