Obic Co., Ltd.: Japan's Quiet ERP Champion and the 2025 Digital Cliff

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

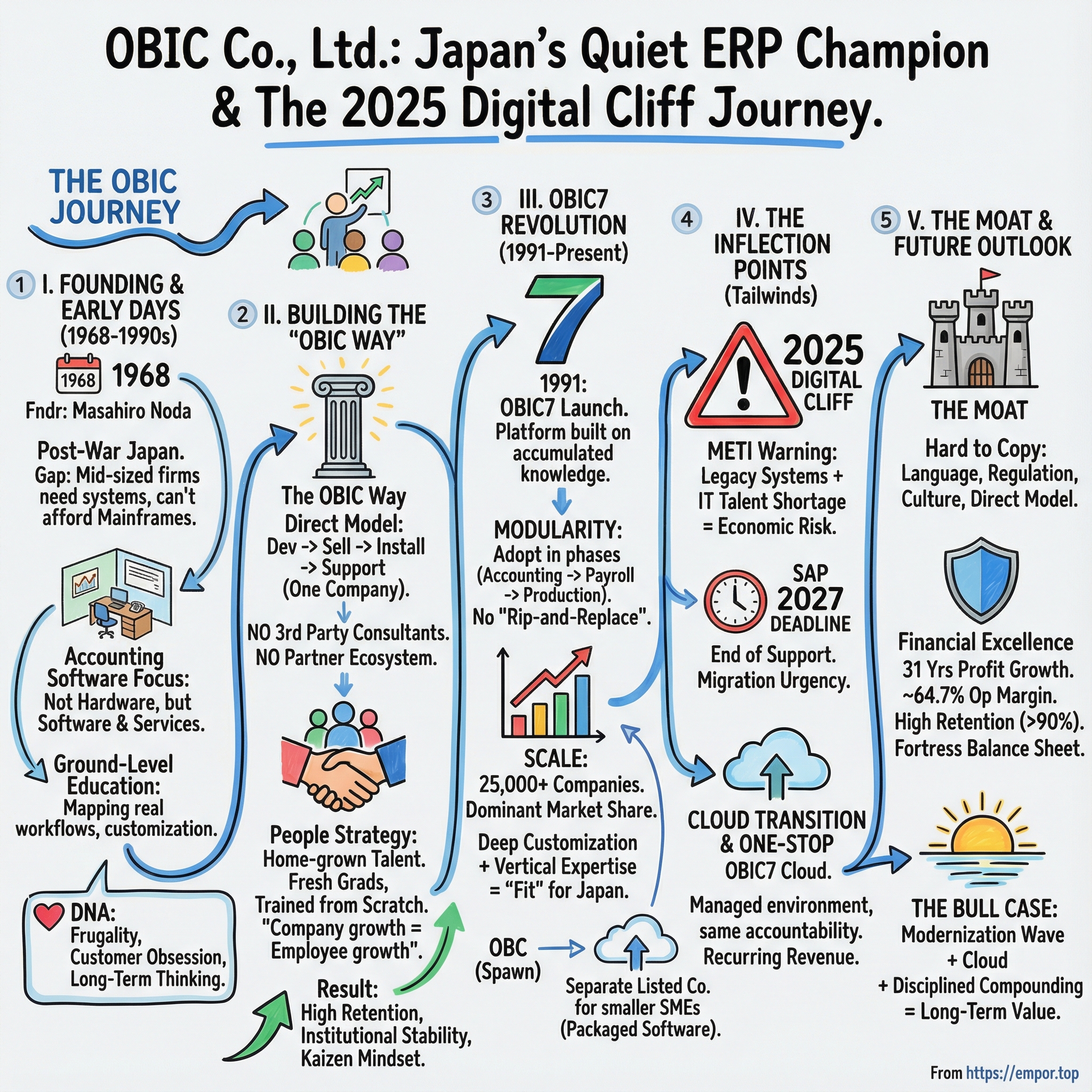

Picture this: a company founded in 1968—when Japan was gearing up to dazzle the world—quietly writing accounting software while the headlines went to Sony and Toyota. Nearly six decades later, that same unflashy firm has become one of the most profitable enterprise software businesses anywhere. And outside Japan, almost nobody knows its name.

OBIC built its empire around a deceptively simple idea: one flagship product, OBIC7, sold, customized, implemented, and supported directly by OBIC itself. It’s ERP, tailored to each customer’s exact needs—and it’s been the default choice for Japan’s mid-sized companies for more than two decades.

Then there are the numbers. In fiscal year 2025, operating income rose 10.5% to JPY78.4 billion—OBIC’s 31st consecutive year of operating profit growth. Margins expanded too, up 110 basis points to 64.7%. Net profit increased 11.4% to JPY64.6 billion. Thirty-one years in a row is the kind of consistency that’s almost unheard of in software, anywhere.

OBIC also runs with a fortress balance sheet: 200.07 billion yen in cash and no debt, for the same 200.07 billion yen of net cash. Pair that with a 77.85% gross margin, and operating and profit margins of 63.36% and 53.30%, and you start to see what’s hiding in plain sight.

But the stat that really gives the game away is retention: customer retention in the high 90s%. That doesn’t happen because of clever marketing. It happens when your software becomes part of how a company actually functions—deeply embedded, trusted, and extremely hard to replace.

And that brings us to why this story matters now.

Japan is staring down what its own government has called the “2025 Digital Cliff.” In 2018, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s DX Report warned that unless Japanese companies fully commit to digital transformation, they could face economic losses of up to 12 trillion yen per year as aging legacy systems become too costly and risky to maintain.

The “Cliff” isn’t just about outdated technology. It’s also about people: an impending wave of retirements among experienced IT professionals, colliding with the massive burden of maintaining and rebuilding decades-old systems.

OBIC—rooted in Japan’s business culture, armed with proprietary software, and powered by a direct-sales, direct-support model—looks uniquely positioned to benefit from this once-in-a-generation modernization cycle.

This is the story of how founder-led discipline, cultural fluency, and relentless focus created a quiet software juggernaut—and why the next decade could end up being even more pivotal than the last five.

II. The Founding Story: Japan's Mainframe Era

To understand OBIC, you have to start with Japan in 1968. The post-war economic miracle was in full swing. Factories were humming, exporters were scaling, and a new wave of medium-sized businesses was spreading across the country—big enough to need real management systems, but not big enough to afford them.

That gap was the opening.

OBIC Co., Ltd. was founded on April 8, 1968 by Masahiro Noda and Mizuki Noda. In the beginning, it wasn’t an “ERP company.” It was an accounting software company—focused on the most universal pain point in business: keeping the books, paying people, and staying in control as the organization grew.

The catch was that “business software” didn’t just mean software back then. In 1968, accounting systems required specialized hardware that cost around ¥10 million. Back-office automation lived in the world of mainframes and punch cards—tools reserved for the biggest, most established corporations.

Noda saw what the giants didn’t. Japan’s emerging mid-market—companies with hundreds of employees, not thousands—needed modern systems just as badly. They simply couldn’t pay the toll to enter the mainframe era. So instead of trying to win on hardware, OBIC leaned into software and services that could ride the wave of increasingly affordable computing.

Those early years weren’t glamorous, and that’s the point. OBIC began as a computer services and system integration firm, doing the work up close: sitting with customers, mapping workflows, and learning how Japanese companies actually operated. That ground-level education—what hurts, what breaks, what has to be customized because “that’s how it’s done here”—became a long-term advantage that would compound for decades.

Today, Noda remains Chairman and a 23% holder—still at the center of the company more than five decades later. Masahiro, along with other family members, holds a large stake in the publicly traded business, the foundation of their billion-dollar fortune. But OBIC isn’t a founder story about a big exit. It’s a story about staying, iterating, and accumulating—patiently building value year after year.

That founding DNA—frugality, customer obsession, and long-term thinking—became the cultural bedrock OBIC built everything else on.

III. Building the Model: The "Obic Way"

Walk into OBIC’s headquarters in Chuo-ku, Tokyo, and you’ll find something that feels almost out of place in modern tech: an unwavering, almost monastic commitment to one way of building a software business.

OBIC’s model is simple—by design. One core product, built by OBIC, implemented by OBIC, and supported by OBIC. No third-party consultants. No “partner ecosystem” doing the messy work. One company, accountable end to end.

That simplicity is radical in an industry that usually runs on complexity. In Japan especially, many IT vendors operate like general contractors: they win the client, then delegate everything from hardware to development to a chain of subcontractors. It’s a “contractor of contractors” setup where responsibility gets diluted, projects sprawl, and the customer is often left managing the fallout.

OBIC does the opposite. It develops, sells, and installs its proprietary ERP software, OBIC7, using only its own employees. That tight control over execution directly addresses the biggest fear mid-sized companies have with ERP: implementation failure. And when customers trust you to land the plane, you can build a business that throws off extraordinary economics—like OBIC’s nearly 78% gross margin.

But the most extreme part of the OBIC model isn’t the product strategy. It’s the people strategy.

Since Masahiro Noda founded the company in 1968, OBIC has insisted on keeping operations home-grown: no sales agents, and no mid-career hires. In an industry where lateral hiring is standard and job-hopping is expected, OBIC hires fresh university graduates and trains them from scratch.

This is rooted in one of the company’s core philosophies: “company growth starts with employee growth.” New hires go through extensive training and learn to work in the “OBIC Way,” an approach shaped carefully by Noda over decades. Pay is among the best in the industry, and retention is high: the average OBIC employee is 36 years old and has been with the company for more than 13 years.

“We are like the Chairman’s children,” OBIC staff say. To Western ears that can sound unusual, but it captures the company’s internal logic: OBIC operates like a long-term institution, not a tournament. Loyalty runs both ways, and the expectation is that you’re building a career, not just shipping a project.

OBIC describes the aim of the OBIC Way as discovering “new ideas and innovations every day”—a mindset that echoes kaizen, Japan’s ethic of continuous improvement. The result is something rare in technology: institutional stability that doesn’t calcify. Since 1997, operating margin and operating profit have grown every year—nearly three decades of uninterrupted progress, powered less by flashy reinvention than by relentless, compounding execution.

IV. The OBIC7 Revolution (1991-2000s)

By the early 1990s, OBIC had spent more than two decades doing the unglamorous work: system integration, on-site implementations, and building relationships deep inside Japanese companies. Then it made the bet that would define the next era of the business.

In 1991, OBIC launched its first ERP system, OBIC7. It wasn’t just a new product. It was OBIC’s accumulated field knowledge—turned into a platform. And for Japanese mid-sized companies, it changed what “business management software” could actually be.

OBIC7 wasn’t built around one killer feature. Its advantage was fit. It reflected how Japanese companies really ran: the approvals, the handoffs, the reporting, the edge cases that always show up in real operations and never show up in a generic demo.

At its core, OBIC7 offered an integrated suite covering the back office and beyond—personnel, payroll, working condition management, marketing, and production—along with industry-specific solutions tailored to the realities of each business.

The design choice that made it all work was modularity. OBIC7 let customers adopt the system in phases without breaking everything else. A company could begin with accounting, add payroll later, then bring production management online when the organization was ready—without turning the implementation into a rip-and-replace migration every time it expanded.

That architecture also reinforced OBIC’s biggest strength: focus. With one flagship platform to improve, the company could pour its R&D energy into making OBIC7 more flexible, more reliable, and more deeply adaptable. Over time, that compounding effort produced a system with thousands of customized modules across hundreds of industry verticals.

The result is scale that’s easy to miss if you’re not looking for it: OBIC7 has been deployed across more than 25,000 companies in Japan. It became the default ERP choice for medium-sized corporations for more than two decades—commanding a market share larger than the next two competitors combined. In enterprise software, that kind of dominance doesn’t come from hype. It comes from execution.

By 2000, OBIC extended the product line with OBIC8. But the playbook didn’t change. The strategy stayed consistent: deep customization, vertical expertise, and relentless improvement to the underlying platform.

And here’s the deeper insight: OBIC understood something that global ERP giants struggled with in Japan. Many Japanese corporations didn’t want “shrinkwrap” software. Their processes, hierarchies, and regulatory requirements made out-of-the-box systems from vendors like SAP or Oracle expensive to adapt—and risky to implement. OBIC didn’t treat customization as an add-on. It baked it into the core offering from the start.

That’s why OBIC’s long-running presence in Japan’s ERP market has translated into something far more valuable than market share: an institutional understanding of how Japanese businesses actually work, and what they need from the systems that run them.

V. The Spawn: OBIC Business Consultants (OBC)

While OBIC was building its platform, another story was unfolding alongside it.

In 1980, a 28-year-old CPA named Shigefumi Wada was juggling a lot at once: running a consulting practice for small and mid-sized businesses, working part-time as an auditor, and teaching accounting to aspiring CPA students. And in the middle of all that, he started experimenting with early ERP-style systems—practical tools to help clients get a grip on inventory and production.

That experimentation put him on OBIC’s radar. OBIC agreed to fund Wada, and the result was the creation of an information technology consulting business that would later become OBIC Business Consultants, or OBC—now a separately listed company that fits next to OBIC almost like a missing puzzle piece.

The two names get mixed up all the time, but the distinction matters. OBIC owns 36% of OBC, and they’re both powerhouses in the SME world—but they play very different games.

OBIC sells customizable ERP solutions, and it makes its money through system integration and long-term maintenance support. OBC, on the other hand, sells packaged software: not customizable, but fast to install and easy to roll out. That difference naturally shapes the customer base. OBIC typically serves larger organizations—often in the 1,000 to 2,000 employee range—while OBC focuses on smaller firms, roughly 20 to 1,000 employees.

It’s segmentation done right. OBIC goes after the bigger, more complex transformations where customization is the whole point. OBC wins where simplicity and speed matter most—companies that want a proven system without the cost and disruption of bespoke development.

OBC’s flagship product is Kanjo Bugyo, a back-office accounting system with a top market share among ERP software in Japan. The broader Bugyo brand has become nearly synonymous with SME back-office software, and OBC has leaned into the cultural resonance: “Bugyo” is tied to the spirit of Kabuki theater, and the company says that generational tradition reflects its own commitment to keep taking on new challenges for customers—and its passion for Japanese manufacturing.

The company has remained founder-led. Wada started the business in 1980; his wife, Hiroko, is vice president and a board member. Together they own a significant stake. OBIC remains a major shareholder, and Masahiro Noda serves as chairman of OBIC Business Consultants.

To Western eyes, the cross-shareholding and intertwined governance can look unusual. But in practice, it has created long-term alignment while still letting each company pursue a distinct strategy.

Taken together, OBIC and OBC cover the full spectrum of Japan’s SME market—from the smallest proprietorships all the way up to substantial mid-market enterprises with thousands of employees. And that breadth doesn’t just expand the addressable market. It helps cement both companies’ positions in an economy where trust, continuity, and relationships are often the real differentiators.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #1: Japan's "2025 Digital Cliff"

This is where the story shifts—from OBIC as a steady, disciplined compounder to OBIC as a potential beneficiary of a national emergency.

In September 2018, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) published a digital transformation white paper that quickly became known as the “DX Report.” Its warning was blunt: if Japan failed to modernize, the country could face economic losses of up to 12 trillion yen per year after 2025. METI gave the problem a name—the “2025 Digital Cliff”—and, in doing so, effectively put a deadline on decades of underinvestment.

That number is staggering. But what’s more striking is how plausible the underlying diagnosis is.

METI’s data suggests that around 80% of Japanese companies still rely on legacy systems. Not “legacy” as in “old-fashioned,” but legacy as in systems that have been patched, extended, and kept alive long past their intended lifespan—often running mission-critical operations on technology stacks that date back to a different era.

And the cliff isn’t just about software. It’s about people.

At the same time that these systems are aging out, Japan has been facing a growing shortage of IT talent. METI has pointed to a widening gap in IT specialists—from a shortfall of 170,000 in 2015 to an estimated 430,000 by 2025. Put those together—older systems plus fewer engineers who know how to maintain them—and you get the nightmare scenario: rising costs, rising risk, and a shrinking ability to change.

A 2021 report from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications captured the trap Japan has fallen into: “ICT investment in Japan has been on the decline from the peak in 1997,” and “80% of its ICT investments are used for maintenance and operation of the current businesses.” In other words, most of the budget goes to keeping yesterday alive. Very little goes to building tomorrow.

For years, corporate Japan has lagged global peers in IT investment. But demographics and productivity pressures don’t negotiate. The country needs modernization, and the government has started treating it like a national priority. In FY2024, METI established the Legacy Systems Modernization Committee under the Priority Plan for the Realization of a Digital Society—explicitly to assess how much legacy tech is blocking digital transformation as the 2025 cliff approaches.

And the spending response has already begun. The Bank of Japan’s Tankan survey shows software investment grew at double-digit rates in 2022 and 2023.

For OBIC—five decades into building the product, the delivery model, and the on-the-ground credibility to modernize Japanese business systems—this isn’t just a tailwind. It’s the kind of environment that creates once-in-a-generation demand.

VII. INFLECTION POINT #2: SAP's 2027 End-of-Support Deadline

If the 2025 Digital Cliff created urgency, SAP’s timeline poured fuel on the fire.

SAP—the biggest ERP vendor in Japan—announced it will end mainstream maintenance for SAP Business Suite 7 core applications at the end of 2027, with optional extended maintenance through the end of 2030. In practical terms, SAP will end mainstream support for SAP ECC (ERP Central Component) on December 31, 2027. After that, companies still running ECC should expect a world with fewer updates, fewer fixes, and more operational risk—unless they pay up for extended support.

That single date forces a decision for thousands of Japanese companies that standardized on SAP years ago. And it’s not an easy one. They can migrate to SAP S/4HANA, which is widely seen as complex, time-consuming, and expensive. They can pay premium fees to keep the old system on life support. Or they can switch platforms entirely.

The kicker is that a large share of customers may still be on ECC when the deadline hits. Many companies, staring at the cost and disruption of an S/4HANA migration, have kept postponing. But postponement doesn’t stop the clock—it just compresses the work into a narrower window.

That’s what makes this wave so powerful. ERP projects are slow by nature. Fresh implementations often take 12 to 18 months, and migrations can run even longer once you factor in integrations, customizations, data, training, and the reality that you can’t just “ship it” when payroll and invoicing are on the line. So as 2027 approaches, the bottleneck isn’t just budget. It’s time, talent, and execution capacity.

For domestic providers, this is a once-in-a-generation opening. And for OBIC—already trusted by Japanese mid-market companies, already built around deep customization, already delivering in Japanese with an end-to-end model—the timing is about as good as it gets.

For many mid-sized Japanese firms, the comparison increasingly isn’t “SAP versus nothing.” It’s “a painful S/4HANA migration” versus “a clean break to OBIC7.” OBIC’s fluency in Japanese business practices, Japanese-language support, and total cost of ownership advantages turn what used to feel like a risky switch into a rational, even attractive, alternative.

VIII. INFLECTION POINT #3: Cloud Transition & One-Stop Solutions

If the Digital Cliff and SAP’s deadlines create urgency, OBIC’s next move determines how it captures it. The company is adapting its model for the cloud era—without giving up the very things that made it dominant in the first place.

At a high level, OBIC operates across three segments: System Integration, System Support, and Office Automation. But the throughline is consistent: OBIC wants to be the single accountable owner of the customer’s core systems. That approach has helped it sustain steady growth in Japan’s ERP market over the past 17 years, and it’s the same philosophy it’s now bringing to cloud.

The OBIC7 Cloud platform is the clearest expression of that shift. It lets customers run OBIC7 in a managed cloud environment—modern delivery, but with the familiar OBIC promise: a tightly controlled implementation and a long-term relationship with the same vendor that built the software.

That matters because the closer Japan gets to the 2025 cliff—the scenario METI warned could translate into enormous annual economic losses if legacy systems aren’t replaced—the more companies want big, end-to-end answers, not incremental fixes. And Japan’s contradiction only makes the opportunity feel larger: a world leader in robotics that still relies on fax machines in everyday business.

Of course, cloud doesn’t come for free. OBIC faces real risks as it migrates. Its reputation was built on highly tailored, service-heavy delivery, and the shift to cloud forces changes in operating rhythm, skills, and how resources get allocated. Done poorly, cloud could dilute the very model that made OBIC trusted.

But done well, cloud sharpens OBIC’s advantage. Offering both the software and the infrastructure means customers don’t have to stitch together an ERP system, a hosting provider like AWS or Azure, and a support organization—and then hope accountability doesn’t vanish when something breaks. With OBIC, they get a full stack: application software, hosting, and support from one provider.

And there’s a financial flywheel here, too. Traditional license sales can be lumpy—big upfront projects followed by smaller maintenance streams. Cloud delivery shifts that toward subscriptions, creating steadier, more recurring revenue and a deeper, more continuous engagement with customers over time. That’s not just a different billing model. It’s OBIC embedding itself even more tightly into the operating fabric of Japanese companies.

IX. The Moat: Why Foreign Competitors Can't Win in Japan

OBIC’s strengths are notoriously hard to copy—especially for international enterprise software companies that have tried, and repeatedly failed, to scale in Japan. The reason isn’t that SAP or Oracle lack engineering talent. It’s that Japan’s corporate reality has sharp edges, and ERP has to fit those edges perfectly. That gives OBIC a highly defensible position in the niche it chose decades ago.

So what are the “corporate idiosyncrasies” that act like natural barriers to entry?

First, language and paperwork aren’t details here—they’re the system. Business software in Japan has to handle the full complexity of written Japanese: hiragana, katakana, and kanji, often mixed with English in the same workflow. It has to support Japanese-era date formats, Japanese naming conventions, and the specific document layouts companies expect. When your ERP is the source of truth for payroll, invoicing, and compliance documents, “mostly works” isn’t good enough.

That’s one reason Japanese companies often prefer ERP developed by domestic vendors. Many employees aren’t fluent in English, and even when a product is translated, it can still feel foreign in everyday use. And culturally, many companies prioritize stability and reliability over having the newest features—especially when the software is running core operations.

Second, there’s regulation. Japan’s accounting standards, tax requirements, labor laws, and industry-specific rules don’t map cleanly onto Western defaults. An ERP system has to reflect those differences and keep up as rules change. That demands constant updates and deep local expertise—not just a localization team, but a vendor that lives inside the regulatory cadence of Japan.

Third, there’s culture. In a 2020 speech, Japan’s then Minister for Administrative Reform, Taro Kono, openly criticized how resistant the workplace could be to modernization. “Why do we need to print out paper?” he asked, pointing to the continued reliance on legacy tools like fax machines. The subtext was even harsher: by sticking to old ways of working and underinvesting in IT capabilities, corporate Japan was holding back its own productivity.

In that environment, OBIC’s delivery model is more than a go-to-market choice—it’s a moat. Since Masahiro Noda founded the company in 1968, OBIC has insisted on keeping operations home-grown: no sales agents, no mid-career hires. The result is a workforce trained inside one system, one culture, and one way of serving customers—people who understand both the software and the context it has to survive in.

Zoom out, and Japan’s IT landscape is unusual among developed economies. Analysts often describe the average Japanese firm as treating IT more like a problem to be managed than a strategic advantage. IT teams can sit low in the corporate hierarchy, receiving directives “thrown over the proverbial wall for IT to execute.”

But that mindset creates an opening: companies don’t just need tools—they need trusted partners who can take ownership of transformation end to end. That’s exactly where OBIC has spent decades positioning itself. And it’s why foreign competitors, even with global scale, so often find Japan to be the market they can enter—but can’t truly win.

X. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Japan isn’t a market where you can drop in a global ERP product, hire a channel partner, and call it a day. International companies routinely struggle to scale in Japan because the “last mile” is the whole game: the language, the workflows, the documentation, the approval chains, and the expectation of deep, ongoing customization.

OBIC sits in a highly defensible niche because it has what new entrants can’t conjure quickly: decades of accumulated modules, industry-specific know-how, a trained direct sales and delivery organization, and relationships built over long implementation cycles. Replicating that would take years of investment and patience—with no guarantee customers would switch.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

OBIC keeps its dependencies unusually low because it builds and delivers essentially everything in-house. It doesn’t need a sprawling ecosystem of third-party consultants, subcontractors, or service partners to make projects work. That self-sufficient setup limits supplier leverage and keeps OBIC in control of both quality and economics.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

OBIC typically serves mid-sized companies, often in the 1,000 to 2,000 employee range. These customers are meaningful, but the business isn’t hostage to any one account.

The bigger factor is what happens after go-live. With customer retention in the high 90s%, the message is clear: once OBIC7 is embedded into payroll, accounting, and core operations, switching becomes painful, risky, and expensive. Buyers may have negotiating power up front, but it fades once OBIC is running the business.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

At the low end of the market, cloud-native startups like freee and Money Forward are growing fast—but they’re built for smaller companies with simpler needs.

OBC’s SaaS offering, Bugyo Cloud, is part of the same broader trend, but only a small portion of customers have fully migrated so far. For the mid-market—where customization, integrations, and industry-specific workflows matter—there still isn’t a clean “plug-and-play” substitute for a system like OBIC7.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

There is competition, but it’s segmented by company size and by how much customization a customer expects. OBIC7 holds a market share larger than the next two competitors combined, and that dominance is reinforced by a model rivals struggle to match: one product, delivered end-to-end, with accountability that doesn’t get diluted across layers of contractors.

XI. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Software has a beautiful economic trick: the big development costs are largely fixed, and each additional customer can add revenue without adding anything close to the same level of cost. OBIC has leaned into that dynamic for years. Revenue compounded at 10.7% annually to JPY121.2 billion in FY25, while operating income compounded even faster at 13.1%—with margins expanding to 64.7% in FY25.

Network Effects: LIMITED

ERP isn’t a classic network-effects business. Your payroll system doesn’t get better because your neighbor uses the same one. But OBIC does benefit from a quieter kind of network effect: the more OBIC-trained people there are, the smoother implementations become; smoother implementations win more customers; more customers justify training even more people. It’s not viral growth—it’s operational momentum.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

OBIC’s model is almost designed as a rebuttal to how enterprise IT is typically delivered in Japan: one product, designed, integrated, and serviced by the same company, without third-party consultants or service providers. In a market built on multi-layered system integrators and subcontractors, OBIC’s refusal to outsource is a strategic stance.

And incumbents can’t simply copy it. SAP, Oracle, and others are deeply intertwined with their partner ecosystems. Those channel partners aren’t just distribution—they’re the delivery engine. Trying to vertically integrate the way OBIC does would mean blowing up the very structure that supports their Japan business.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

ERP sits at the center of the enterprise. Once it’s running payroll, accounting, reporting, and day-to-day workflows, it becomes less like “software” and more like infrastructure. OBIC’s customer retention in the high 90s% is the tell: switching means unwinding years of customization, retraining teams, rebuilding integrations, migrating data, and taking on the risk of operational disruption. Most companies don’t do that unless they absolutely have to.

Branding: MODERATE

In enterprise software, brand isn’t about being trendy. It’s about being trusted. OBIC’s reputation for service quality—and its position as Japan’s leading ERP provider—carries real weight in a business culture that rewards stability, track record, and proven partners.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

OBIC’s most unusual asset may be its workforce. Since Masahiro Noda founded the company in 1968, OBIC has kept operations home-grown: no sales agents, no mid-career hires.

Instead, it hires new graduates, trains them extensively, and steepens them in the OBIC Way. That creates a cornered resource. Competitors can’t easily “buy” OBIC expertise by poaching from the market, because OBIC didn’t build that expertise in the market. It built it inside its own walls.

Process Power: VERY STRONG

OBIC has been running a decades-long compounding machine: continuous improvement that has produced a highly flexible product with thousands of customized modules across hundreds of industry verticals.

Its long-running presence at the top of Japan’s ERP market—sustained over the past 17 years—reflects something rivals struggle to reproduce: deep institutional knowledge of how Japanese industries operate and what customers actually require. That knowledge isn’t written down in a manual. It’s embedded in the product, the delivery process, and the people.

XII. The Masahiro Noda Leadership Philosophy

Masahiro Noda is OBIC’s founder, and he is still at the helm more than five and a half decades later. In a software industry that reinvents itself every few years, that kind of continuity isn’t just unusual—it’s defining.

Noda founded OBIC Co., Ltd. and serves as Chairman at OBIC. He also holds senior roles across the broader group: Non-Executive Chairman of OBIC Business Consultants Co., Ltd., and Chairman of OBIC Office Automation Co., Ltd. The throughline is control and consistency. OBIC doesn’t just sell stability to customers; it’s built on it.

And Noda’s incentives are about as aligned as they get. He remains OBIC’s Chairman and a roughly 23% shareholder—real skin in the game, in a company where long-term decisions actually stick.

By the fiscal year ending March 2023, OBIC reported $672 million in revenue and $403 million in net profit. As of 2024, Noda’s net worth was estimated at $3.3 billion, making him the 11th richest person in Japan. But the more interesting point isn’t the wealth—it’s how it was created: not through a one-time exit, but through decades of disciplined compounding inside a single operating company.

That’s the “Day Zero” mentality you see in a certain class of founder-led Japanese businesses: capital discipline, an owner’s mindset, and a refusal to optimize for short-term optics. These are start-ups that grew old without ever losing the instincts that made them durable. They speak the language of shareholders because, quite literally, they are run by shareholders.

The paradox of OBIC is that a conservative culture produced aggressive profitability. By refusing to chase growth for growth’s sake, maintaining unusually high quality standards, and investing continuously in employee development, Noda built a machine that compounds value year after year.

In Japan, there’s a recognizable cohort of companies that fit this pattern—Fast Retailing, Hikari Tsushin, Nidec, Keyence, Softbank, Pan Pacific, Nihon M&A, Hoya, Zozo, Peptidream, Kobe Bussan, and Sushiro among them. OBIC belongs in that company: founder-led champions that have delivered extraordinary long-term returns.

XIII. Business Model Deep-Dive: The Three Segments

At its core, OBIC runs a three-part business: System Integration, System Support, and Office Automation.

System Integration is the upfront work—designing and building integrated core business systems. System Support is everything that follows—keeping those systems running, improving them, and standing behind them for the long haul. Office Automation supplies general office equipment and computer-related products.

But here’s the part that explains OBIC’s durability: the majority of its revenue comes from System Support.

This last point is crucial: System Support generates the majority of revenue. That’s the recurring engine. It’s what turns OBIC from a project business into a compounding machine.

System Integration: Land

System Integration is how OBIC wins a customer in the first place—building and installing a new OBIC7 implementation. In FY25, this segment made up 42% of sales. It’s the “land” in a land-and-expand strategy: a major, high-stakes deployment that gets OBIC embedded into the customer’s operations.

System Support: Expand

Once OBIC7 is live, the relationship shifts into System Support—maintenance, upgrades, customization, and operational support over time. This is where OBIC’s model really flexes: every successful implementation doesn’t just create a one-time sale, it adds another long-lived account to the support base.

Office Automation: Complementary

Office Automation is the supporting act: selling general office equipment and computer-related products. It’s not the core value driver, but it keeps OBIC close to customers and broadens the relationship beyond software alone.

The beauty of the whole structure is how it stacks. Each new System Integration deal can translate into years—often decades—of System Support revenue. And with customer retention in the high 90s, that base doesn’t churn away. It accumulates.

XIV. Financial Excellence: The Numbers Behind the Story

By the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025, OBIC had reached another milestone: annual revenue of 121.24 billion yen, up 8.65% year over year.

And the bigger picture is even more telling. From FY22 through FY25, revenue grew at a 10.7% CAGR to JPY121.2 billion. Over that same span, operating income compounded faster—up 13.1% annually to JPY78.4 billion—while operating margin expanded by 414 basis points to 64.7%. Net income climbed at a 14.1% CAGR to JPY64.6 billion, with net margin expanding by 469 basis points to 53.3%.

Those are not normal software numbers. Operating margins north of 60% are rare in any industry. For a business that still does meaningful implementation and support work, they’re almost unheard of. It’s the clearest proof that OBIC isn’t just selling software—it’s selling a tightly controlled system of delivery that scales.

Even more impressive: OBIC achieved this without financial engineering. ROE held steady at 15.5% from FY22 to FY25, and it did it with no leverage—just disciplined capital deployment and a machine that reliably turns revenue into profit.

That discipline shows up on the balance sheet. OBIC held 200.07 billion yen in cash and carried no debt, leaving it in a pure net cash position. Over the last 12 months, it generated operating cash flow of 62.79 billion yen against just 2.07 billion yen of capital expenditures, resulting in free cash flow of 60.73 billion yen.

In other words, the earnings are real. Free cash flow conversion is exceptional: most of the operating profit drops straight through to cash, because the business simply doesn’t require heavy ongoing investment in physical assets. And that cash engine has been steadily strengthening, with cash from operations rising from JPY39 billion in FY22 to JPY62.8 billion in FY25.

Looking ahead, analysts expect the compounding to continue. Forecasts call for revenue to grow at a 9.1% CAGR from FY25 to FY27 to JPY144.2 billion, with EBIT growing at a 10% CAGR to JPY94.9 billion and margins expanding another 115 basis points to 65.8% by FY27. Net profit is expected to rise at a 9.1% CAGR to JPY76.9 billion.

XV. Competition Landscape

Zoom out, and Japan’s ERP market is crowded—with familiar global giants, heavyweight domestic IT firms, and a long tail of specialists. Key names include Works Applications, SAP Japan, Oracle Japan, Microsoft Japan, Fujitsu, NEC, NTT Data, Miroku Jyoho Service, OSS ERP Solutions—and, of course, OBIC itself.

The market is also growing quickly. The Japan ERP software market was valued at USD 5.06 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 6.32 billion by 2025. From there, forecasts expect it to keep expanding to USD 14.15 billion by 2030, implying a 17.49% CAGR from 2025 to 2030.

But the more important point isn’t just that the pie is getting bigger—it’s how the competitive battlefield has split into distinct layers.

At one end, there’s the cloud-native wave. Japan’s largest SaaS companies by annual recurring revenue include Rakus, Sansan, Appier, Cybozu, freee, and Money Forward. Many of these are horizontal business platforms, and several overlap with ERP-adjacent territory—especially accounting and finance.

Inside that SaaS cohort, Money Forward competes most directly against freee at the SME level. Move up-market and the competition shifts: for larger mid-sized companies, the set expands to include Yayoi (part of Orix) and OBC’s Bugyo.

This segmentation is the hidden structure of the market. Historically, big corporations could afford to commission customized software and the hardware to run it. SMEs couldn’t, so they gravitated toward affordable, shrinkwrap-style packaged software.

That dynamic still holds, and it’s why the market remains tiered: OBIC is strongest in the mid-market, particularly companies in the 1,000 to 2,000 employee range. OBC skews smaller. And cloud-native players like freee and Money Forward fight hardest for the smallest businesses and startups—where speed, simplicity, and low upfront cost matter more than deep customization.

XVI. Key Risks and Considerations

No business compounds this steadily without real risks lurking underneath the surface. OBIC’s story is unusually clean—but it isn’t risk-free.

Generational Transition Risk: Masahiro Noda is 85 years old. OBIC has been shaped by his philosophy for more than five decades, and detailed continuity planning isn’t publicly disclosed. For any founder-led company, succession is a moment when culture, decision-making, and standards can drift—and that uncertainty matters more here because OBIC’s model is so tightly tied to how it operates internally.

Cloud Transition Execution: OBIC faces a long list of execution risks as it migrates toward the cloud. The biggest is simple: the company’s reputation and economics were built on a tightly controlled, service-heavy delivery model. If cloud delivery changes how projects are staffed, priced, or supported—or if it introduces reliability or security issues—OBIC could end up disrupting the very machine that made it trusted.

Demographic Headwinds: Japan’s ageing, shrinking population is the macro shadow over every domestic growth story. The country’s population peaked at 128.5 million in 2010 and fell to 122.6 million by 2024. In 2024, the working-age population was about 59.6% of the total—the lowest rate among OECD countries. And 2023 government projections suggest the population could decline to 87 million by 2070.

Over time, fewer people can mean fewer businesses—and fewer businesses means fewer potential ERP customers. To keep growing, OBIC will likely need to win share, deepen its footprint within existing accounts, and increase revenue per customer to offset that structural decline.

International Competition: Foreign ERP vendors have historically struggled to crack Japan, but they haven’t stopped trying. Continued pressure from SAP, Oracle, and Microsoft—paired with gradual shifts in corporate attitudes—could narrow the gap and chip away at OBIC’s home-field advantage.

Technology Disruption: AI and automation could change how enterprise software is built, customized, and maintained. If capabilities that currently differentiate OBIC become easier to replicate—or are bundled into broader platforms—the competitive landscape could shift in ways that compress OBIC’s edge.

XVII. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For anyone tracking OBIC over the long run, the story shows up in a handful of simple signals. Three KPIs matter most:

1. System Support Revenue Growth Rate: This is OBIC’s recurring engine—the part of the business that turns a one-time implementation into years of dependable cash flow. If this line keeps growing steadily, it usually means two things are still true: customers are sticking around, and OBIC is expanding what it does inside existing accounts. A sustained slowdown here would be an early warning that the flywheel is losing momentum.

2. Operating Margin: At 64.7% in FY25, OBIC is operating in rarified air. The question now is whether it can hold that level while funding a real cloud transition—new infrastructure, new delivery models, new demands from customers—without giving back the economics that make the company so unusual.

3. New Customer Acquisition (System Integration Deals): System Integration is the front door. Each new implementation is how OBIC “lands” an account that can later turn into long-lived System Support revenue. The pace of new wins—especially from SAP migrations and companies finally moving off legacy systems ahead of the Digital Cliff—will tell you whether OBIC is capturing the modernization wave or merely watching it go by.

XVIII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The “2025 Digital Cliff” is the kind of forcing function enterprise software companies dream about: a national deadline wrapped in a national productivity problem. METI’s warning—up to JPY 12 trillion in annual losses if legacy systems aren’t modernized—has turned digital transformation from a “nice-to-have” into a board-level mandate.

And it’s not just talk. The Bank of Japan’s Tankan survey shows software investment grew at double-digit rates in 2022 and 2023, a signal that budgets are finally starting to move.

In that environment, OBIC’s position looks unusually strong. Its strengths are difficult to replicate, especially for international vendors that struggle with Japan’s corporate idiosyncrasies—language, regulatory detail, and the expectation of deep, ongoing customization. OBIC isn’t trying to be everything to everyone; it’s built to win a specific customer profile in a specific market, and it has decades of process and product advantage baked in.

Then comes the second catalyst: SAP’s deadline. As mainstream maintenance ends for SAP ECC in 2027, companies that have delayed migration decisions will be forced to act. Many will choose S/4HANA. But for mid-market Japanese firms looking for a practical alternative—one that fits how Japanese operations actually run—OBIC7 becomes a very credible “clean break” option.

Underneath it all, the financial engine remains disciplined. ROE held steady at 15.5% from FY22 to FY25, and analysts expect it to rise to 16.2% by FY27—suggesting OBIC can keep compounding even as it funds a cloud-era evolution of the model.

The Bear Case

The biggest macro risk is simple and unavoidable: Japan is shrinking. Over time, a smaller working-age population tends to translate into a smaller economy, fewer growing mid-sized companies, and a tighter ceiling on the domestic addressable market—no matter how powerful the modernization tailwinds feel in the near term.

Then there’s execution risk around cloud. OBIC’s edge has been its tightly controlled, service-heavy delivery model—tailored implementations, deep customer involvement, and end-to-end accountability. Moving more of that into cloud changes how projects are delivered, what skills the workforce needs, and how resources get allocated. If the organization resists change or the transition introduces operational friction, OBIC could face real disruption in the very engine that made it reliable.

Competition is also shifting. Cloud-native players are growing fast. freee, in particular, has prioritized sales growth and invested aggressively, becoming a leader in cloud accounting for SMBs and the fastest SaaS company in Japan to reach ARR 10 billion. Today, freee and Money Forward mostly fight at the smaller end of the market—but their natural path is upmarket. If they keep climbing, OBIC’s mid-market stronghold could eventually face pressure.

Finally, there’s the risk that the Digital Cliff doesn’t hit with the force the government expects. 76.8% of Japanese companies say they’re promoting DX initiatives, but only about one-third have achieved notable results. If companies keep postponing the hard work—despite the reports, the committees, and the deadlines—the “cliff” could end up functioning more like a talking point than a true demand shock.

XIX. Conclusion: The Power of Patience

OBIC Co., Ltd. is a reminder of something the tech world tends to forget: the biggest outcomes don’t always come from the loudest companies. Sometimes they come from the ones that keep showing up—year after year—doing the same hard things with discipline.

For more than half a century, OBIC compounded value the unsexy way: by shipping one core platform, owning implementation end-to-end, and investing relentlessly in its people and process instead of chasing dramatic pivots. Since 1997, operating margin and operating profit have grown every year—nearly three decades of steady, compounding improvement that looks a lot like kaizen in corporate form.

Now the environment around OBIC is changing fast. Japan’s “2025 Digital Cliff” is turning legacy modernization into an urgent national project. SAP’s end-of-support timeline is forcing thousands of ERP customers to make decisions they’ve deferred for years. And cloud adoption is shifting expectations toward managed, one-stop solutions—the exact kind of accountable, full-stack relationship OBIC has always sold.

OBIC fits that rare category: a start-up that grew old without losing its founder’s mindset. It speaks the language of shareholders because it’s led by one.

The open question is whether OBIC can convert this once-in-a-generation demand wave into the next chapter of its compounding story—while executing a cloud transition without diluting what made it trusted, and eventually navigating leadership succession in a company so shaped by Masahiro Noda.

But if there’s one thing OBIC’s history suggests, it’s this: betting against patient, disciplined execution—especially when the market finally catches up to it—has usually been a losing trade.

In an era obsessed with disruption and hypergrowth, OBIC offers a different lesson. Sometimes the most powerful strategy is doing one thing exceptionally well, for an exceptionally long time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music