Nippon Paint Holdings: The Art of Building a Global Paint Empire

I. Introduction: A Company Transformed

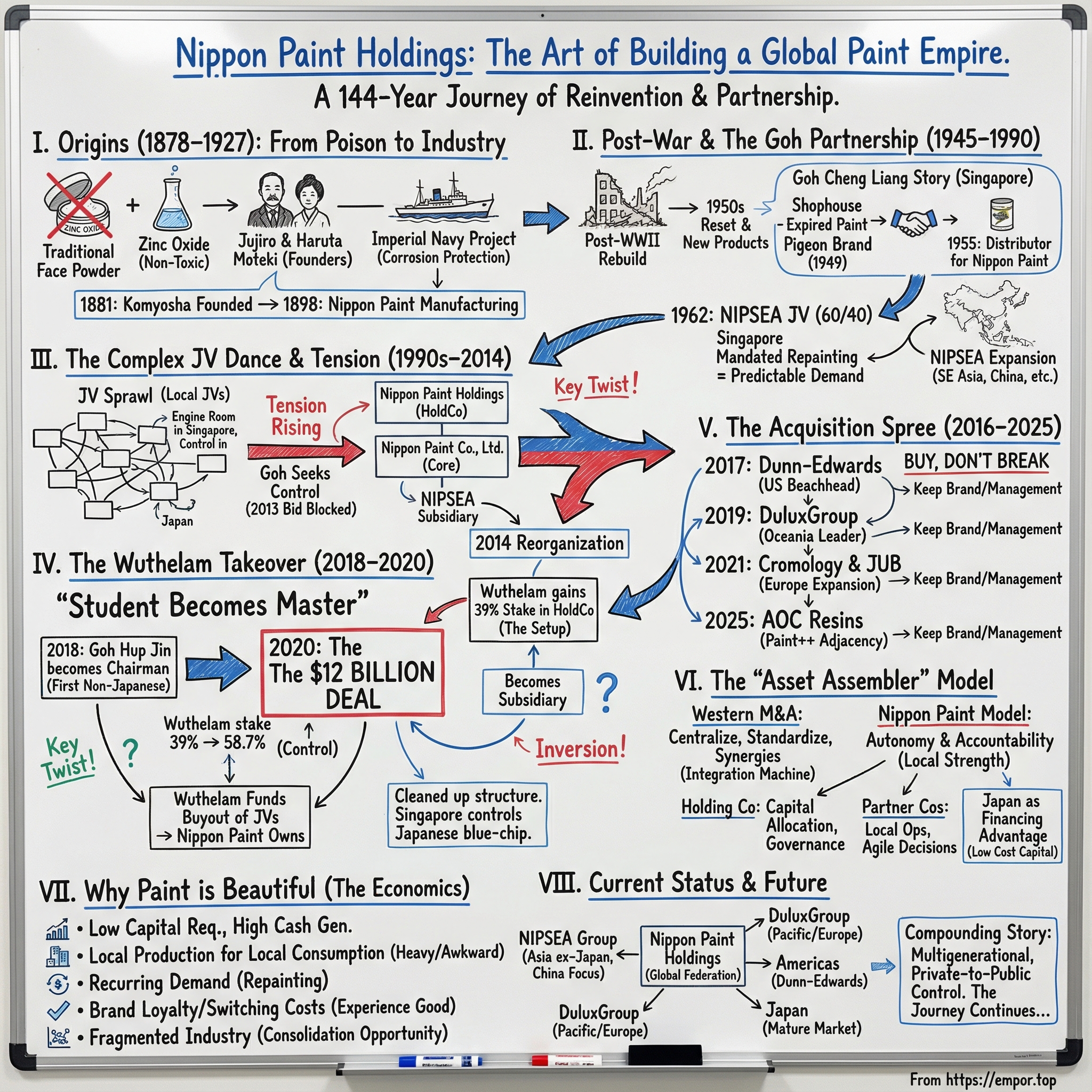

Picture this: an elderly Singaporean businessman, born into poverty in a cramped shophouse room, now holding the keys to one of Asia’s most valuable industrial companies. A century-old Japanese paint maker, once a quiet domestic player, suddenly owning the dominant position across China, Southeast Asia, and Australia. And at the center of it all: a roughly $12 billion transaction that flipped the usual script on how power changes hands in corporate partnerships.

Today, Nippon Paint is a global paint company with operations in over 50 countries. Roughly two-thirds of its sales come from decorative paint—mostly residential, with some commercial mixed in. It holds the leading share in China and several other Asian markets, and it’s a major force in Australia. Elsewhere, it tends to sit comfortably among the top few players.

Its products reach customers through an enormous network of paint and home improvement retailers—around 300,000 distributors worldwide. And while “paint is paint” sounds true until you’re standing in the aisle choosing between a dozen cans, the brand stable here is real: Nipsea, Nippon Paint, Dulux (in Asia, the Pacific, and Europe), British Paints, Betek Boya, Alina, and more.

The central question of this story is deceptively simple: how did a 144-year-old Japanese manufacturer transform itself from a steady home-market business into Asia’s paint emperor?

The answer lives inside one of the strangest long-running corporate relationships in modern business history—one that began with a young Singaporean distributor looking for a product to sell, then evolved over six decades into something rarer: the student becoming the master, and the junior partner effectively taking control.

What makes the story so compelling isn’t just the time span—from early industrial-era chemistry to modern mega-deals. It’s the operating philosophy that emerges along the way. Nippon Paint eventually put a name on it: the “Asset Assembler.” And it’s a direct challenge to the Western playbook.

Where American and European acquirers often buy companies and immediately centralize, standardize, and hunt for “synergies,” Nippon Paint built its empire by leaning into the opposite instinct: acquire great businesses, then keep their local advantages intact. In a category as regional and on-the-ground as paint, that difference isn’t a nuance. It’s the whole game.

By annual sales rankings, Nippon Paint sits in rare air: fourth globally, behind Sherwin-Williams, PPG, and AkzoNobel—and ahead of other giants like Axalta, BASF, and Kansai Paint. But rankings are a snapshot. The more interesting story is momentum: Nippon Paint is the only Asian company in the global top four, and it has been expanding faster than its Western rivals.

The backdrop is a massive, steadily growing market. Global paints and coatings was valued at over $200 billion in 2023 and is expected to keep climbing through the next decade. The center of gravity is Asia Pacific—which is exactly where Nippon Paint is strongest. This is its home court, and over the last decade it hasn’t just played defense. It’s been building a fortress.

So this story has a few big threads that weave together into one outcome. There’s the rags-to-riches arc of the Goh family, from selling basic goods to becoming paint billionaires. There’s the Asset Assembler model, a deliberate rejection of the traditional M&A integration machine. And there’s the final twist: why paint—unsexy, physical, supposedly commoditized—turns out to be one of the most attractive businesses in the world when you understand how it really works.

II. Origins: Lead Poisoning and the Dawn of Japanese Industry (1878–1927)

The story begins not with paint, but with poison.

In Meiji-era Japan, a quiet health crisis was hiding in plain sight. The iconic white face powder used for centuries—the look of classical beauty—often contained lead. Women were getting sick. Some died. And in 1878, an older brother named Haruta Moteki posed a practical, urgent question to his younger brother Jujiro: could he make a safe alternative, in Japan, without relying on imports?

Jujiro was still a student then, studying first at Keio Gijuku and later at Kaisei School, the predecessor to the University of Tokyo. But he took the problem seriously. Out of a sincere desire to help people suffering from lead poisoning, he began producing zinc oxide: a non-toxic white powder.

It was a very Meiji moment. Japan was modernizing at breakneck speed, pulling in foreign science and industrial methods, then trying to adapt them fast enough to stand alongside Western powers. Moteki even gave his new venture an aspirational name: Komyosha, meant to evoke the idea of making society brighter.

And almost immediately, the mission expanded beyond cosmetics.

Jujiro was approached by Heikichi Nakagawa, the chief paint engineer of the Imperial Navy, with a bigger challenge: build a domestic paint manufacturing business. Japan didn’t just want modern ships; it wanted the supply chain that kept them functional. Hulls had to be protected from saltwater corrosion. Equipment had to survive heat, rain, and time. Paint wasn’t decoration. It was strategic infrastructure.

So in 1881, Jujiro and Haruta founded Komyosha, launching what would become the Nippon Paint Group. That same year, they succeeded in producing zinc oxide and developing an original paste-type paint—early proof that Japan could make Western-style coatings with local know-how.

This wasn’t a symbolic partnership, either. Japan’s oldest paint samples were applied in 1881 to a partition screen by Nakagawa himself. He saw Komyosha as a national project: one more piece of the country’s industrial independence.

The early factory reality was brutally manual. From 1881 through 1897, the company used a hand-operated roll mill to knead colored paint. Three workers could produce about 60 kilograms in a day. By modern standards, it’s painfully slow. In context, it was the beginning of an industry.

In 1898, the company was incorporated and renamed Nippon Paint Manufacturing, a step that marked the birth of a full-scale modern paint industry in Japan. Then, in 1927, it became simply Nippon Paint—shorter, more confident, and fitting for a company that had grown into the country’s preeminent paint manufacturer.

By this point, Nippon Paint wasn’t just supplying naval coatings. Japan’s industrial base was exploding—factories, railways, bridges, and the machinery of a modern nation—and all of it needed protection and finishing. Coatings were everywhere, even if no one thought about them.

There’s a straight line from Jujiro Moteki trying to replace toxic makeup powder with zinc oxide to Nippon Paint becoming embedded in Japan’s national development. The surfaces of a rising industrial power were, quite literally, being sealed and strengthened by this company.

But for all that growth, Nippon Paint was still a Japan story. It would take decades before it started to look seriously beyond the home market—and longer still before a chance encounter in Singapore would reshape the company into something much bigger than a domestic champion.

III. The Post-War Expansion and the Goh Cheng Liang Story (1945–1990)

When World War II ended, Japan was rebuilding from rubble. Industry had to restart, cities had to be reconstructed, and companies like Nippon Paint had to claw their way back from near-zero.

The 1950s became Nippon Paint’s reset—and its launchpad. The company introduced new products, including alkyd resin paints that fit perfectly with the surge in residential and commercial construction. In 1954, it also entered a 50/50 joint venture with Bee Chemical. The partnership brought in new technology and, just as importantly, signaled that Japan’s industrial champions were reconnecting with the global economy.

But the most important “expansion” Nippon Paint would make in this era wasn’t a product line or a lab breakthrough.

It was a relationship.

It began with a young Singaporean entrepreneur who had no pedigree, little formal education, and an instinct for opportunity that would eventually reshape Nippon Paint’s future far more than any single innovation.

The Goh Cheng Liang Story: From Fishing Nets to Paint Empire

Goh Cheng Liang was born in Singapore in 1927 and spent his earliest years packed into a single rented room in a River Valley shophouse—seven people sharing one small space. His father had no job. His mother did laundry to keep the family going. It was the kind of childhood that teaches you, early, that nothing is guaranteed.

When the war came, he went where he could survive. He moved to Muar, Johor, and helped his brother-in-law sell fishing nets. Later, he returned to Singapore and tried his hand at selling aerated water. It failed. So he took work in a hardware store—Tan Chong Huat—where he learned the basics of materials, customers, and commerce the hard way, over years on the job.

Then, after the war, an unlikely opening appeared. The British were auctioning off surplus inventory, including barrels of expired paint. Most people saw junk. Goh saw raw material. He bought the barrels for next to nothing, began experimenting—mixing, adding solvents, making the unusable usable—and turned that scrappy operation into a real product.

In 1949, he launched Pigeon Brand.

By 1955, he opened his first paint shop in Singapore. And a few years after that came the break that mattered: his business became the main distributor of Nippon Paint in Singapore.

That distributor relationship became the seed of a partnership that would eventually span decades and continents. In 1962, the two sides formalized it with a joint venture: Nipsea Management Group, structured with a 60–40 holding. In 1965, Nippon Paint followed through with hard assets, establishing its first manufacturing plant in Singapore.

Singapore’s Secret Weapon: Mandated Repainting

Singapore had a built-in tailwind that most paint companies can only dream of: regulation.

Under Singapore’s Building Maintenance and Strata Management framework, painted exterior walls must be repainted at regular intervals—traditionally on a five-year cycle, later amended in practice to allow longer intervals in certain cases, including a seven-year cycle used for HDB exteriors.

For Goh, this created something rare in a physical, project-driven business: predictability. Paint demand wasn’t just tied to whims, fashions, or one-time construction booms. A meaningful slice of the market was structurally recurring. Buildings didn’t just get painted. They got repainted—again and again—on a schedule.

That kind of certainty helps a distributor do what distributors always dream of doing: build reach and scale with confidence.

The NIPSEA Expansion

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the Nippon Paint–Goh partnership spread beyond Singapore. NIPSEA expanded across Southeast Asia, including moves into Thailand and Malaysia. Later, the Group pushed further afield—into the U.S. in 1975, then China in 1992, and into other Asian countries around 1993.

As the footprint grew, so did the corporate complexity behind it.

In 1974, Goh established Wuthelam Holdings. Over time, it expanded beyond paint into other ventures, including real estate and other businesses, but paint remained the engine. Wuthelam also became the vehicle through which Goh held his stake and influence in the broader Nippon Paint ecosystem.

By this point, Nipsea operated in more than 15 countries outside Japan, with roughly 15,000 employees and factories across 30 locations.

What started as a straightforward “local distributor sells Japanese paint” arrangement had evolved into something far more unusual: an intertwined joint venture structure spanning Asia, where the Singaporean partner owned meaningful stakes in major operating businesses, even as the Japanese company retained control in key places.

It worked—spectacularly—for a long time.

It also planted the seeds of the tension to come.

IV. The Complex Joint Venture Dance (1990s–2014)

By the early 2000s, Nippon Paint and the Wuthelam Group had built one of Asia’s most formidable paint businesses. But the way they’d built it had a hidden flaw.

Over decades, the partnership had turned into an intricate web of joint ventures spread across country after country. Nippon Paint in Japan typically owned the majority of these operating companies. Wuthelam, through the NIPSEA Group, often held large minority stakes and—crucially—was deeply involved in running the business day to day.

On paper, Nippon Paint had control. In practice, the engine room sat in Singapore.

For a long time, that tension didn’t matter, because the machine was printing growth. NIPSEA’s expansion into China in 1992 was perfectly timed with the start of a historic construction boom. As Asia urbanized, demand for paint followed—new apartments, new offices, new infrastructure, all needing to be coated, protected, and eventually repainted. The partnership rode that wave hard.

Then success did what it always does: it changed everyone’s sense of what they deserved.

By the early 2010s, Goh Cheng Liang—by then one of Singapore’s wealthiest businessmen—started to push for a different relationship with his Japanese counterpart. Nippon Paint had worked with Wuthelam for more than 50 years, and in 2013 Wuthelam began efforts to gain majority control of the Japanese company.

In the context of Japanese corporate culture, this was close to heresy: a Southeast Asian partner, originally a distributor, trying to take control of a venerable Japanese manufacturer with more than a century of history.

The relationship was already being renegotiated behind the scenes. In 2006, Nippon Paint tried to increase its stake in 11 of the joint ventures. The partners managed to reach agreement on three. Then the global financial crisis hit, sales slumped, and negotiations on the rest stalled.

Even as talks froze, Wuthelam kept quietly accumulating influence. Its stake in Nippon Paint rose to 14% from 9% by 2008. Then in 2013, when Wuthelam attempted to increase its ownership to 45%, it was blocked.

That failed bid mattered less for what it achieved than for what it revealed. Wuthelam was no longer acting like a minority partner looking for dividends. It was acting like an owner-in-waiting.

The next move came fast. The following year, Nippon Paint offered Wuthelam a path to raise its stake to 39%—but only if Wuthelam agreed to turn the remaining eight joint ventures into subsidiaries of Nippon Paint. It was a trade: less ambiguity in the operating structure in exchange for more power at the top.

The 2014 Reorganization: Setting the Stage

In October 2014, Nippon Paint reorganized into a holding company and adopted its current name. This wasn’t corporate housekeeping. It was a strategic reset designed for a company that had outgrown a Japan-centric structure and needed to manage an increasingly international empire.

The holding company became Nippon Paint Holdings Co., Ltd. A new operating company, Nippon Paint Co., Ltd., was established to run core functions. The stated goal was to improve global management efficiency and strengthen coordination across businesses.

Then came the big structural domino. In November 2014, with the exception of Nippon Paint Indonesia, the NIPSEA Group officially became a subsidiary of Nippon Paint Holdings. After decades of joint-venture sprawl, much of the Asian business was now pulled under the holding company more directly.

The reshuffle also elevated Nippon Paint’s standing in the global hierarchy—helping propel it to number one in Asia and into the top tier worldwide.

And there was one more consequence that would prove decisive later: as part of this new arrangement, Wuthelam ended up with a 39% stake in Nippon Paint Holdings. It was meant to align incentives and cool the conflicts that came from the old structure.

But if you’d watched how Goh Cheng Liang built his empire—one patient step at a time—you could see the new equilibrium for what it was.

Not an ending.

A setup.

V. The Wuthelam Takeover: When the Student Becomes the Master (2018–2020)

In March 2018, Goh Hup Jin—Goh Cheng Liang’s son and the operational leader of the Wuthelam Group—was appointed chairman of Nippon Paint Holdings. He wasn’t a ceremonial pick. He was the family’s point person, shaping strategic direction and managing the shareholder relationship from the Wuthelam side.

It was a changing of the guard. For the first time in Nippon Paint’s long history, the chairman wasn’t Japanese. The Singaporean family that had once been “just” the distributor was now sitting at the head of the table.

Behind the scenes, it was also a near miss. In 2018, the relationship between the two sides came close to spilling into a full proxy fight as Goh Hup Jin pushed to reshape the board. In March, shareholders approved the appointment of 10 directors, including six proposed by Wuthelam. The message was clear: Wuthelam wasn’t asking for influence anymore. It was taking it.

Goh Cheng Liang, though officially retired, remained the architect of the family’s approach. In a rare 1997 interview with The Business Times, he explained why he preferred private control to public-company compromise. “My personal philosophy is I never want to go public,” he said. “First, I’m not a professional manager. Second, these professional managers who come and join me, I don’t know how to handle them, I don’t know how to drive them.”

That mindset—control over consensus—makes the next act easier to understand. As long as someone else held the reins at the holding-company level, the Gohs were still, in a sense, working inside someone else’s house. And Goh Cheng Liang had never been comfortable in that role.

The $12 Billion Deal of 2020

Then came 2020, and the partnership’s long-running contradictions were finally resolved—at full scale.

Nippon Paint Holdings struck a 1.29 trillion yen (about $12 billion) deal with Wuthelam Holdings to create what they described as a dominant paints and coatings company in Asia. The transaction was designed to lift Wuthelam’s stake in Nippon Paint Holdings from 39% to 58.7%.

The mechanics were as clever as they were consequential. Wuthelam would take control by buying new shares in Nippon Paint. Nippon Paint would then use most of that cash to buy out the joint ventures the two groups had built together across Asia—covering markets including China, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand. It also included Nippon Paint buying Wuthelam’s wholly owned Indonesian business for about $2 billion.

In other words, Wuthelam effectively funded the cleanup of the very JV structure that had made the relationship so complicated for decades. Nippon Paint emerged owning the Asian operations outright, and Wuthelam emerged as the controlling shareholder at the top.

What made it even more striking was the timing. This was one of Asia’s largest transactions of 2020, agreed in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic—when most companies were focused on survival, not rewriting their corporate DNA.

By the end of it, Wuthelam had formally taken control of Japan’s largest coatings maker—an inversion of the usual regional power dynamic. For decades, Japanese industrial giants expanded into Southeast Asia. Here, a Singaporean family ended up controlling the Japanese blue-chip. The student had become the master.

The stated intent was to unify the Asian businesses to pursue “more ambitious moves” and deliver shareholder returns. But the deal did something deeper: it reduced conflicts. Because Nippon Paint Holdings now held the Asian businesses directly, minority shareholders no longer had to worry about value being trapped inside joint ventures or negotiated through related-party arrangements. Control moved to the holding company, and the operating structure became far cleaner.

Years later, the family’s ascent showed up plainly in wealth rankings. In Forbes’ 2025 list of billionaires, Goh Cheng Liang was named the richest Singaporean, with an estimated net worth of $13 billion.

And then, the final note in a remarkable arc. Goh Cheng Liang—born into poverty, builder of a paint empire, and one of Singapore’s wealthiest men—died in August 2025 at age 98.

His eldest son, Goh Hup Jin, called his father “a beacon of kindness and strength,” adding: “We are very fortunate to have had him show us how to be a good person – he taught us to live life with compassion and humility.”

VI. The Acquisition Spree: Building an Empire (2016–2025)

While the Wuthelam takeover was working its way through boardrooms and balance sheets, Nippon Paint was doing something else in parallel: it was shopping.

Not in a “collect logos” way. In a very specific way. Find strong local champions, buy them, and then… don’t break them. Let them keep their brands, their operators, and the on-the-ground habits that actually win in paint.

That playbook shows up clearly in the deals that defined the last decade.

Dunn-Edwards (2017): The American Beachhead

In 2016, Nippon Paint entered into a merger agreement with Dunn-Edwards Corporation, one of the United States’ largest independent manufacturers of architectural, industrial, and high-performance paints. The terms weren’t disclosed, but the transaction closed in early March 2017, after which Dunn-Edwards became a wholly owned subsidiary of Nippon Paint (USA) Inc.

The messaging was telling. Nippon Paint said it would maintain the Dunn-Edwards brand and its range of products. Dunn-Edwards’ CEO, Karl Altergott, emphasized continuity: “We will continue business as usual as Dunn-Edwards, producing our superior paint and maintaining our culture that we’ve embraced for 91 years.” The upside, he said, was resources—more technology, more support, and the backing of a “financially strong global leader.”

From Nippon Paint’s side, the rationale was straightforward. “We’ve wanted to expand our architectural paints in the U.S. and have been searching for the right partner,” the company’s president and CEO said.

Nationally, Dunn-Edwards was small in the context of the overall U.S. decorative paints market. But regionally, it mattered—especially in California, where it was estimated to hold a meaningful share, with additional strength in neighboring areas. That concentration made the deal what Nippon Paint needed: not instant U.S. dominance, but a credible beachhead with a real brand and a real distribution footprint.

DuluxGroup (2019): The Landmark Oceania Deal

Dunn-Edwards gave Nippon Paint a foothold. DuluxGroup gave it a new pillar.

In 2019, Nippon Paint Holdings agreed to acquire Australia’s DuluxGroup Ltd. for A$3.8 billion (about $2.7 billion) in cash. The prize wasn’t just paint. DuluxGroup brought the country’s top sales channel for paints and coatings, plus a broader set of adjacent categories—sealants, adhesives, garage doors, cabinets, and architectural hardware.

At the time, Nippon Paint framed the deal as part of keeping pace with consolidation in a global industry where the largest players were getting larger. On 21 August 2019, the acquisition was implemented via a Scheme of Arrangement, and Nippon Paint Holdings acquired 100% of DuluxGroup’s shares.

Just as importantly, Nippon Paint didn’t try to “Japan-ify” Dulux. Dulux kept its name. It kept its leadership team. It operated as a division within Nippon Paint, adding Australia and New Zealand to a footprint that already spanned Asia, Europe, and the U.S.

This deal also made the company’s acquisition philosophy impossible to miss: buy the leader, keep the brand, keep the management, and let them run. No forced headquarters integration. No cultural reset. No ripping out the capabilities you just paid for.

Since joining Nippon Paint Group, DuluxGroup continued pursuing acquisitions—over 30 of them, spanning both strategic moves and smaller bolt-ons—alongside organic growth initiatives. The company has also maintained the No.1 market share in Australia for decorative paints, both in volume and value terms.

European Expansion: Cromology and JUB

After Dulux, Europe came into focus.

Nippon Paint expanded into the region through additional acquisitions, including the 2021 purchase of Europe’s Cromology Holding and its subsidiaries. DuluxGroup, drawing on the growth playbook it had built in the Pacific, moved to accelerate expansion through Cromology—described as the fourth-largest player in the European decorative paints market—and JUB, a leader in Central European decorative paint markets.

Again, the pattern held: local strength first, then scale—without trying to run Paris or Ljubljana from Tokyo.

AOC Resins (2025): The Latest Major Acquisition

Then Nippon Paint pushed beyond paint itself—into “Paint++,” the adjacencies it sees as the next frontier.

The company signed an agreement to acquire LSF11 A5 TopCo LLC and its subsidiaries, collectively known as AOC, for €2.1 billion (about $2.3 billion). AOC is a global specialty formulator based in the United States and Europe, focused on composite resins and materials used across industries including automotive, construction, and marine.

Nippon Paint positioned the deal squarely inside its Asset Assembler approach: expand through value-added businesses that fit the broader coatings ecosystem. Yuichiro Wakatsuki, director and co-president of Nippon Paint, said, “This acquisition enhances our global presence and product offerings in the specialty chemicals sector.”

The transaction was expected to close in the first half of 2025, subject to customary conditions and approvals. On March 3, 2025, Nippon Paint Holdings announced it had completed the acquisition and payment procedures for all equity interests in AOC, making it a subsidiary.

Zoom out, and the arc is clear. A company that once looked like a primarily Japan-centered manufacturer now holds dominant positions across Asia-Pacific, with expanding platforms in the Americas and Europe—and a growing appetite for adjacencies that make the whole system bigger than “just paint.”

VII. The "Asset Assembler" Model: A New Way to Do M&A

If there’s one idea that explains why Nippon Paint’s dealmaking looks so different from everyone else’s, it’s the “Asset Assembler” model. It’s the company’s explicit rejection of conventional Western M&A orthodoxy—and the operating philosophy that makes the whole empire-building strategy work.

In Nippon Paint’s own words, the point is “Maximization of Shareholder Value (MSV)” through “strong growth with limited risk,” by emphasizing “autonomy and accountability” at each partner company while assembling businesses in paint and adjacencies. They eventually gave that approach a name: the Asset Assembler model.

How It Differs From Western M&A

Paint is intensely local. Decorative coatings, in particular, follow a simple reality: local production for local consumption. Customers care about brands they know, colors that match local tastes, contractors they trust, and distribution networks that are built city by city.

So Nippon Paint argues it makes little sense for a holding company to centrally control and standardize partner companies across the Group. Instead, the goal is for partner companies to learn from one another and generate synergies as a Group—without flattening what made each business great in the first place.

That’s the inversion of the typical Sherwin-Williams or PPG playbook. In the Western model, the acquirer buys a target and then integrates hard: consolidate back offices, standardize systems, cut overlaps, and capture “synergies” by eliminating redundancy.

Nippon Paint’s bet is that, in this category, the bigger synergy is preservation. Buy a business with a great management team, then don’t replace it with headquarters bureaucracy. Buy a brand with deep local loyalty, then don’t bury it under a global brand architecture. The acquisition is the point; forced integration is the risk.

Autonomy & Accountability: The Operating Principles

The model runs on a tight pairing: autonomy and accountability.

Nippon Paint describes it this way: give management teams at each partner company a high degree of discretion, then hold them accountable for outcomes. That combination is meant to drive fast, agile decision-making while keeping enough control at the Group level to ensure performance. The company also positions this balance as central to attracting and retaining strong talent—and as a driver of sustainable EPS compounding.

Governance-wise, the holding company keeps a few levers. Decisions on appointing and dismissing partner company CEOs, along with financial strategy, sit with the holding company’s management team as the Group’s top decision-makers. Outside of that, partner companies pursue their own initiatives, with the expectation that the Group benefits from shared learning and cross-pollination rather than top-down mandates.

In practice, it means the holding company stays lean. The operators—the people actually building the businesses—remain inside the partner companies. The center’s job is to allocate capital, create the conditions for knowledge sharing, and enforce accountability.

Japan as Financing Advantage

There’s another edge that quietly makes the Asset Assembler model easier to execute: Japan.

Nippon Paint points to Japan’s stable currency and perceived safety, plus enduring relationships with financial institutions, as a foundation for low funding costs. By taking advantage of persistently low interest rates in Japan, the company believes it can maintain an advantage over Western companies that face meaningfully higher borrowing costs.

In an acquisition-driven strategy, that matters. When you’re funding deals over and over, the cost of capital is a competitive weapon. Cheaper financing gives Nippon Paint more flexibility on price and structure—and more room to generate attractive returns once the asset is inside the Group.

The "Paint++" Strategy

The Asset Assembler model isn’t limited to paint. Nippon Paint’s plan is to push into adjacencies—what it calls “Paint++”—by expanding from paint and coatings into neighboring categories that share customers, channels, or technical capabilities.

Adjacencies include things like adhesives, sealants, building products, and specialty chemicals. AOC, for example, fits that expansion and is likely to be allocated to the Adjacencies Business segment, which accounts for 11% of total sales and already includes adhesives and sealants.

The opportunity is large because paint itself is still fragmented: the top ten global players control less than half of total sales, leaving room for consolidation. But Nippon Paint sees an even bigger field next door. The adjacencies market is roughly three times the size of paint and coatings, and it’s also fragmented—meaning the same “assemble great local businesses without breaking them” approach can be applied to an even wider map.

Nippon Paint frames the end goal as exceptional growth: targeting 10–12% organic EPS growth, with additional upside from M&A that contributes to EPS from year one after acquisition. And it’s explicit about what comes first. The two-part returns approach is: expand the base of EPS growth through M&A rather than optimize for short-term shareholder returns, and reserve cash flows as dry powder for future deals.

In other words, the Asset Assembler model isn’t just how Nippon Paint buys companies.

It’s how it stays hungry—without losing the local advantages that made those companies worth buying.

VIII. Why Paint is a Beautiful Business

To sophisticated investors, “paint company” can sound like the definition of dull. But paint has a set of economic traits that would make the best businesses in the world nod in recognition: it doesn’t take much capital to run, demand reliably comes back around, local players are naturally protected, and the best brands earn real pricing power. Here’s why.

Low Capital Requirements, High Cash Generation

Paint is a low-capex business. Once you’ve built the plants and set up distribution, you’re not constantly pouring money into enormous new facilities just to stay in the game. That has a powerful knock-on effect: operating profit can grow faster than revenue, because incremental volume doesn’t require massive incremental investment.

Nippon Paint makes this a central part of its pitch. Across the Group, partner companies tend to run with low-cost operations and high cash generation precisely because the industry doesn’t demand heavy ongoing capital spending. Capital expenditures are largely aimed at sustaining growth, with the burden of investment relatively small and concentrated mostly in maintenance.

Put paint next to other industrial sectors and the contrast gets obvious fast. Semiconductors require relentless reinvestment. Automakers need sprawling plants and constant tooling upgrades. Even many consumer goods businesses carry heavier manufacturing complexity. Paint, by comparison, is deceptively simple—and that simplicity turns into cash.

Local Production for Local Consumption

Paint is also a “local production for local consumption” business for physical, unavoidable reasons. It’s heavy, awkward to ship, and not especially valuable per unit weight. That makes long-distance imports uneconomic in most cases, which means local manufacturing matters.

This reality creates natural protection. Competitors can’t just export their way into a market from across the world and win on cost. And it’s one reason Nippon Paint’s decentralized approach fits the category: the markets are highly localized, with local preferences, local channels, and local operating rhythms. If paint is local, the best management decisions tend to be local too.

Recurring Demand Tied to Fundamental Drivers

Paint demand tracks the fundamentals of modern life: buildings, transportation, and infrastructure. Residential and commercial construction needs coatings. Cars and trains need coatings. Bridges, roads, and public assets need coatings.

And unlike many construction-related products, paint doesn’t end with the first sale. Paint wears out. Weather and time do their work. Every surface eventually needs repainting. As the stock of built environment grows with population and urbanization, the base of “things that will need repainting” grows right along with it—creating a recurring demand engine that compounds quietly in the background.

Brand Loyalty and Switching Costs

If paint is so physical and standardized, why doesn’t everyone just buy the cheapest can on the shelf?

Because paint is an experience good: you only learn the truth after it’s on the wall and you’ve lived with it. If it doesn’t cover well, fades, peels, or looks uneven, the fix isn’t trivial. It’s time, labor, disruption, and frustration.

That dynamic creates real loyalty. Homeowners gravitate toward brands they trust. Professional painters take it even more seriously—because they’re putting their reputations on the line with every job. They know what applies consistently, dries predictably, and still looks good years later. Switching to an unknown brand isn’t just a cost decision; it’s a risk decision.

The Industry Structure

Paint is also big—and still surprisingly unconsolidated. The global paints and coatings market was valued at just over $200 billion in 2023 and is expected to keep growing through the next decade. Asia Pacific is the largest region, which matters because it’s exactly where Nippon Paint is strongest.

Even at the top, the industry remains fragmented. The global rankings shift—Sherwin-Williams and PPG trade places at the top, with AkzoNobel close behind—but the bigger point is structural: even the top ten players together control less than half the market.

That fragmentation is the oxygen for Nippon Paint’s strategy. In an industry where local brands and local routes to market matter so much, there will always be strong regional champions—and therefore ongoing opportunity for a disciplined acquirer that knows how to buy without breaking what it bought.

IX. Business Segments and Geographic Footprint Today

By 2024, Nippon Paint wasn’t just “expanding.” It was operating at scale, across wildly different markets, with a portfolio that looked more like a federation than a single centralized company.

In 2024, Nippon Paint reported revenue growth of 13.6% and profit growth of 11.2%. For 2025, the company forecast 6.2% revenue growth and 5.5% profit growth.

In its earnings report for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2024, Nippon Paint Holdings said revenue rose 13.6% to ¥1,638,720 million, driven by strong sales in key markets—especially China.

From there, the business breaks down into a few major engines.

NIPSEA Group (Asia ex-Japan)

This is still the crown jewel: the Asian platform that Goh Cheng Liang helped build over six decades, now running at a scale that would’ve been unthinkable back when it started as a Singapore distribution relationship.

As NIPSEA Group CEO, Wee Siew Kim has guided the group through annual profit growth of over 10% since FY2009. His focus within the broader Nippon Paint Group has been to oversee worldwide operations and maximize EPS by growing both revenue and profitability.

China remains the biggest market inside NIPSEA, supported by decades of urbanization and construction. Even with cyclical concerns around China’s property market, Nippon Paint’s view is that the core demand driver still holds: a growing middle class that wants better housing, and an enormous existing base of buildings that need to be maintained.

DuluxGroup (Pacific & Europe)

DuluxGroup’s business continued to grow, with total revenue up 11.8% year-on-year to JPY 248.8 billion. Operating profit rose 15.6% year-on-year to JPY 33.0 billion, driven by higher revenue, despite higher SG&A expenses tied to inflation.

Australia remains the profit engine, with the Dulux brand holding premium positioning and market leadership. In Europe, the footprint is anchored by Cromology in France and JUB in Central Europe—operations that were still, at this point, described as being in integration mode.

Americas

In the Americas, Nippon Paint’s position looks very different: smaller overall, but strategically important.

The segment includes two distinct businesses. In decorative paint, Dunn-Edwards is still modest nationally, with around a 2.5% share of the overall U.S. market. But it’s much stronger where it counts for them—estimated at about 12% in California, and roughly 10–20% in neighboring areas.

The U.S. remains both an opportunity and a challenge. Sherwin-Williams and PPG dominate distribution, and Nippon Paint doesn’t have the kind of owned store network those competitors use to lock in contractors and pull through volume.

Japan

Back home, the picture is mixed.

Japan’s shrinking population puts a ceiling on new construction demand. But paint doesn’t live or die on new buildings alone. The existing building stock still needs upkeep, and Japan’s aging infrastructure requires ongoing maintenance.

Operationally, Nippon Paint said Japan saw revenue from automotive coatings increase, supported by a recovery in automobile production. Industrial coatings revenue was largely unchanged, as the benefit of pricing flow-through was offset by softer market conditions.

Distribution Model

Underneath all of this is the part that doesn’t show up in a factory tour, but decides who wins: distribution.

Nippon Paint products are sold through paint and home improvement retailers, with roughly 300,000 distributors globally. That network—built market by market, over decades—functions like a moat. It’s hard to buy quickly, hard to copy, and once it’s in place, it turns paint into exactly what you want any physical product to become: reliably available, familiar, and default.

X. Competitive Dynamics and Strategic Assessment

The Global Competitive Landscape

Nippon Paint may be the standout Asian consolidator, but it’s playing a global game against three giants with very different weapons.

At the top sits Sherwin-Williams, the industry’s scale monster. In 2024 it posted record net sales of $23.10 billion, and as of March 31, 2025 its trailing twelve-month revenue was $23.03 billion—still the clearest marker of who sets the pace in coatings.

Sherwin’s real edge isn’t just size. It’s control of distribution. With more than 4,800 company-owned stores, Sherwin doesn’t have to fight for shelf space. It owns the shelf. That vertical integration lets it capture retail margin and maintain direct, daily relationships with professional painters—the people who decide what gets rolled onto walls.

Then there’s PPG, another American heavyweight, with about $18.2 billion of revenue in 2024. PPG is less about owned retail and more about breadth: industrial, architectural, automotive—coatings everywhere. It’s a long-established force in Europe, with around a 13% share, and it keeps leaning into innovation, sustainability, and product development to stay relevant across diverse end markets.

Akzo Nobel—AkzoNobel—is the Dutch counterweight. Headquartered in Amsterdam and operating in more than 150 countries, it competes across consumer and performance coatings and ranks as the world’s third-largest paint manufacturer by revenue, behind Sherwin-Williams and PPG.

Nippon Paint’s challenge, and its advantage, is that it doesn’t try to copy any one of these models. Instead, it has built a federation of strong local businesses—especially across Asia—then used that base to expand outward.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Paint looks simple until you try to break into it. Brands are earned slowly through years of consistent performance. Distribution is built one contractor, one retailer, one city at a time. Scale lowers cost, and incumbents already have it. A new entrant typically has only one lever—price—and that’s a painful lever to pull in an industry where profits depend on discipline.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

Key inputs like titanium dioxide, resins, and solvents are widely sourced, but they’re prone to volatility. When raw material prices jump, paint makers can often pass costs through—just not instantly. That lag can compress margins in the short run, even for well-run companies.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Low to Moderate

For homeowners, paint is mostly purchased on trust: brand reputation, the advice of the person behind the counter, or the contractor’s recommendation. Pros are more cost-conscious, but they’re also reliability obsessed—because a bad product costs them time, rework, and reputation. Industrial buyers negotiate harder, but they also demand consistency and technical performance, which limits how “commodity-like” the transaction can become.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

For most surfaces that need protection and decoration, paint is still the default. There are specialized coatings and alternative finishes in certain applications, but there’s no broad replacement that makes traditional paint obsolete.

Industry Rivalry: High but Rational

Competition is intense, especially in mature markets like the U.S. and Europe. But it’s not a race to the bottom. The industry has generally shown pricing discipline—more chess than street fight—which helps preserve attractive economics.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Moderate. Manufacturing scale helps, but paint’s “local production for local consumption” reality limits how much a global footprint translates into a single global cost curve.

Network Effects: Limited. Paint doesn’t become more valuable because more people buy it.

Counter-Positioning: This is where Nippon Paint stands out. The Asset Assembler model—buy great local operators and don’t smash them into a standardized headquarters machine—runs against the integration-first logic many Western peers use to justify acquisitions. For a company like Sherwin-Williams or PPG, copying it would mean changing the story they tell their shareholders about why deals work.

Switching Costs: Real, especially for professionals. Painters build muscle memory around how products spread, cover, dry, and look weeks later. Switching introduces risk—and risk is expensive when your labor is the biggest cost on the job.

Branding: Strong. Brands like Dulux and Nippon Paint can command premium pricing because trust matters in an experience good where the penalty for disappointment is a redo.

Cornered Resource: Not in the classic sense, but Nippon Paint’s access to low-cost Japanese capital functions like one. Competitors can’t easily replicate the same yen-denominated funding advantage.

Process Power: Potentially high. If the Asset Assembler approach consistently produces better acquisition outcomes—especially in a category where local execution is everything—then it becomes a repeatable system, not a one-off strategy.

Bull Case for Investors

-

Dominant Asian Position: Nippon Paint has the leading seat in the world’s largest paint region. If Asia continues to urbanize and upgrade housing stock, demand should outpace global averages.

-

Proven M&A Machine: The company has repeatedly found targets and brought them into the Group while preserving what made them valuable. The market remains fragmented, leaving a long runway.

-

Low-Cost Capital Advantage: Japan’s financing conditions have given Nippon Paint structural flexibility—especially meaningful when global rates are higher.

-

Cash Generative Business Model: Paint’s low-capex profile means a large portion of earnings can translate into free cash flow that can fund dividends, buybacks, or more deals.

-

Counter-Positioning Moat: The Asset Assembler model may be difficult for rivals to copy without undermining their own integration logic and investor expectations.

Bear Case for Investors

-

China Concentration Risk: A meaningful share of profits comes from China. If property market weakness persists, demand could soften.

-

Controlling Shareholder Risk: The Goh family controls nearly 60% of shares. Minority investors benefit when incentives align—and suffer if they don’t.

-

Acquisition Execution Risk: The strategy relies on continued deal success. Overpaying, misjudging a market, or mishandling an acquired business can destroy value.

-

Currency Exposure: A weaker yen can flatter reported results; a stronger yen can swing the other way.

-

Valuation: Shares trade at a premium to some Western peers, implying growth expectations that must be delivered.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Nippon Paint, two KPIs matter most:

-

Earnings Per Share (EPS) Growth: The company explicitly manages for “sustainable EPS compounding.” The key question is whether it can hit its 10–12% organic growth target and layer on M&A that’s accretive from year one.

-

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC): In an acquisition-heavy model, this is the truth serum. Watch whether returns on acquired assets clear the cost of capital within a few years—and whether the ROIC trend holds up as deal cadence continues.

XI. Conclusion: The Paint Emperor's New Clothes

The Nippon Paint story quietly breaks a few “rules” that most business narratives take for granted.

First, it blows up the idea that old industrial companies in shrinking home markets are destined to fade. Nippon Paint is 144 years old and headquartered in Japan—often treated as the case study for demographic decline and economic stagnation. And yet, it remade itself into a global growth company by leaning into where demand was rising, and by treating its home base as a financing and governance platform rather than a ceiling.

Second, it challenges the Western orthodoxy on M&A. In much of corporate America and Europe, acquisitions are sold on “integration” and “synergies”—standardize the systems, consolidate the functions, cut the overlap. Nippon Paint’s most important insight has been that paint is local. So instead of trying to turn every acquisition into a branch office, it has spent the last decade buying excellent businesses and letting them remain excellent—keeping brands, keeping leadership, and using the holding company to allocate capital and enforce accountability, not micromanage operations.

Third, it’s a reminder that business innovation doesn’t only come from software or from elite management theory. The Asset Assembler model didn’t arrive fully formed from a slide deck. It emerged from the strange, decades-long reality of a cross-border partnership between a Japanese manufacturer and a Singaporean distributor—one that forced both sides to learn how to grow without fully merging, and to build trust without surrendering autonomy.

That makes the Goh family’s role worth one last pause. This was a multigenerational, compounding story: from a one-room Singapore shophouse to controlling one of Asia’s largest industrial companies. After Goh Cheng Liang’s death, his stake passed in a rare succession move that skipped a generation, leaving six grandchildren as billionaires through inherited holdings in the paint empire.

And for all the scale and power in that outcome, the man at the center of it remained, by the accounts of those who knew him, intensely private. He loved time with his grandchildren. He enjoyed boating, fishing, good food, and travel. Friends and family remembered him as humble, with a sharp sense of humor—and a lifelong preference for building quietly rather than performing loudly.

For long-term investors, Nippon Paint is as intriguing as it is complicated. The Asian competitive position is real. The deal machine appears durable. Japan’s low-cost capital has been a structural advantage. And if the Asset Assembler approach keeps working as the company pushes further into Paint++ adjacencies, the runway may be longer than it looks.

But the trade-offs are equally real: meaningful China exposure, a controlling shareholder with outsized influence, and a valuation that assumes the compounding continues.

What isn’t in doubt is the achievement. Nippon Paint didn’t just grow. It found an unconventional way to grow—through patience, partnerships, and a disciplined refusal to “fix” what wasn’t broken. It built an empire the unglamorous way: one market at a time, one acquisition at a time, one coat of paint at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music