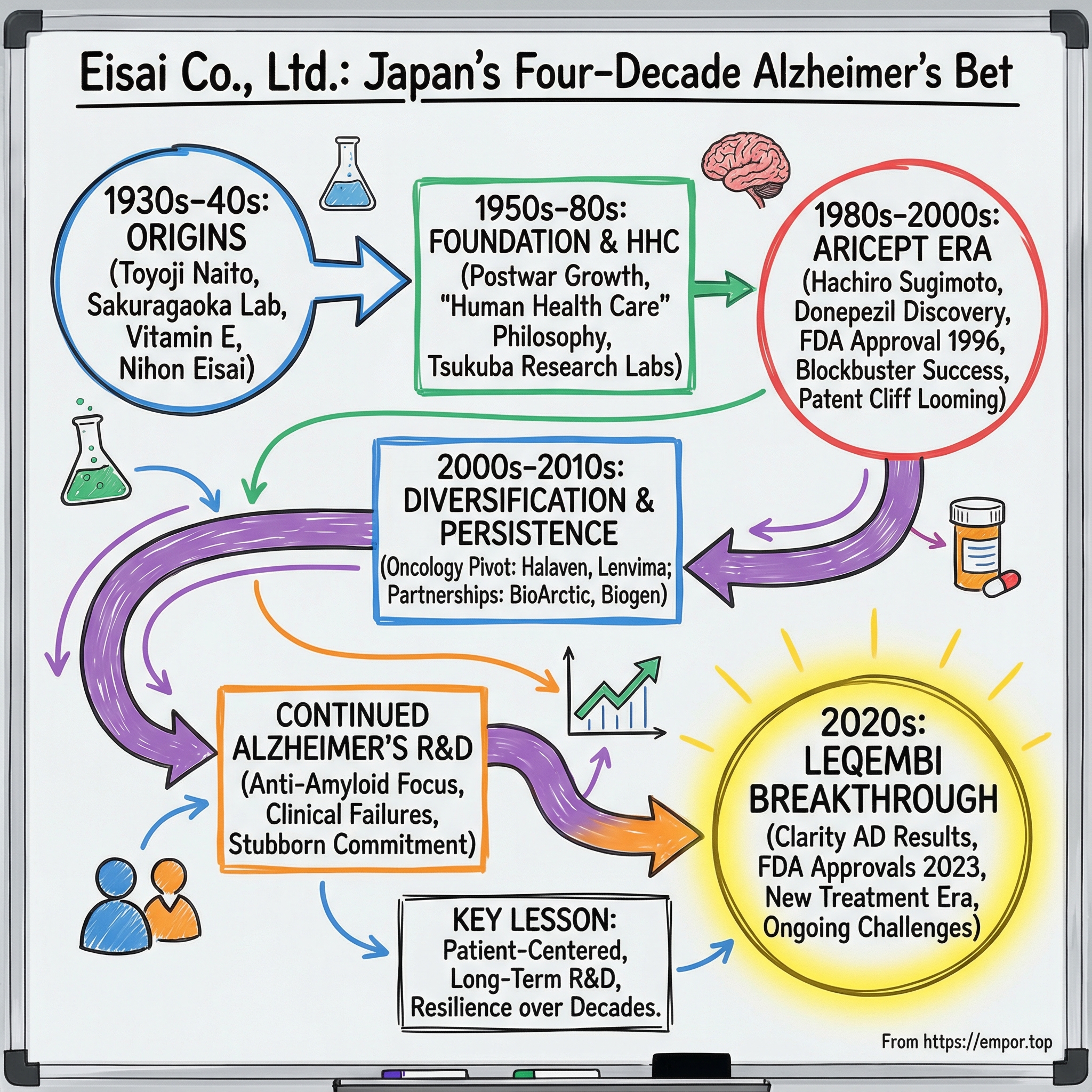

Eisai Co., Ltd.: Japan's Four-Decade Bet on the Alzheimer's Holy Grail

I. Introduction: A Vision Forty Years in the Making

In July 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration did something it had never done before in Alzheimer’s: it converted an accelerated approval into full, traditional approval for a treatment that targets the underlying disease process. The drug was Leqembi.

And the company behind it wasn’t Pfizer. It wasn’t Roche. It wasn’t a Silicon Valley biotech rocket ship. It was Eisai Co., Ltd. — a mid-sized Japanese pharmaceutical company headquartered in Tokyo — hitting a milestone it had been working toward for exactly forty years.

Leqembi’s approval was the payoff on what might be the most patient R&D bet in modern pharma. In the U.S., Leqembi is an amyloid beta-directed antibody indicated as a disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The FDA granted it accelerated approval on January 6, 2023, then traditional approval on July 6, 2023. A six-month regulatory journey at the end — and decades of stubborn persistence before it.

On paper, Eisai can look like any other public company: headquartered in Tokyo, listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, included in the Topix 100 and Nikkei 225, with around 10,000 employees and roughly 1,500 of them in research. But those facts miss the point. Eisai is a family-run company that made an unusually early, unusually deep commitment to the human brain. It built a blockbuster Alzheimer’s franchise, stared down a brutal patent cliff, and then — at the moment most companies would have diversified away — went all-in on the next generation of Alzheimer’s therapies, even as the field argued about whether the science would ever hold up.

This story is about three generations of the Naito family. It’s about a chemist, Hachiro Sugimoto, driven by the slow loss of his mother to dementia. It’s about long years of clinical failure that would have broken less determined organizations. And it’s about a corporate idea Eisai calls “human health care,” a philosophy that shaped what the company chose to work on — and what it refused to give up on.

So to understand how Eisai arrived at July 2023, we have to go back to the beginning. To a founder whose life was shaped by circumstances he never chose — and who built a company around the people medicine is supposed to serve.

II. Origins: A Village Boy, A War, and Japan's Pharmaceutical Awakening

On August 15, 1889, in a small village called Ito tucked into a mountain gorge in Fukui Prefecture, Toyoji Naito was born into a family of loggers and farmers. He was the third son and the sixth child. And when he was seven, his mother, Fuji, died.

That loss didn’t just change his childhood. It defined it.

With his mother gone, Toyoji became the one who kept the household moving. He woke before dawn to make breakfast and pack lunches for his father and siblings, then walked more than six kilometers each way to school along mountain paths. When he returned in the evening, he made dinner. He kept that routine until sixth grade, when he made a decision that speaks volumes about both his circumstances and his drive: he graduated from elementary school two years early.

He was clearly capable. But what ultimately set the direction of his life wasn’t academics. It was a physical limitation that, at the time, could have ended his prospects.

When Toyoji turned 20, he took the military enlistment screening test and joined the Japanese Imperial Guard. There, he was found to be unable to close one eye. That meant he couldn’t aim a rifle—an unforgivable flaw for a frontline soldier. So the army steered him into the only role that made sense: medic.

Those two years changed everything. As a medic, Toyoji was immersed in treatment and medicines, and he became fascinated by how drugs were made, distributed, and used. After completing his service in 1911, he returned to Kobe—by now a second home—and took a job at Thompson Trading Co., Ltd., a British-run pharmaceutical trading company.

At Thompson, Toyoji wasn’t just pushing imported products. He visited local wholesalers with carefully prepared promotional materials, including instructions and package inserts he had translated into Japanese. He made the medicines understandable. And slowly, distributors began to trust him and carry what he sold.

It’s a small detail, but it foreshadows something big: Toyoji’s instinct that medicine only works when it reaches people clearly, safely, and with dignity. Even then, he seemed less interested in “moving product” and more interested in building a system that served patients.

The larger context mattered. In that era, Japan’s pharmaceutical industry depended heavily on imported drugs. And when World War I broke out in 1914, that dependence became painfully obvious. Germany—then a global leader in medicine—was now at war, and supply chains fractured. Japan’s vulnerability wasn’t theoretical anymore.

To Toyoji, it looked like both a national problem and a once-in-a-generation opening.

Over the following decades, he traveled abroad to study the pharmaceutical giants of Europe and the United States. What struck him wasn’t just their products—it was their scale, their laboratories, and their commitment to R&D. He became convinced that without serious research capabilities, Japanese firms would remain distributors for overseas makers, never creators in their own right.

So he did something that would define the rest of Eisai’s history. In 1936, using his own savings, Toyoji founded Sakuragaoka Laboratory Co., Ltd., aiming to develop new drugs in Japan, in-house.

The bet paid off quickly. In 1938, Sakuragaoka launched Juvela, Japan’s first commercial vitamin E product, developed from wheat germ oil extract. It was followed by other hits, including a sanitary tampon called Sampon and a medicated talcum powder, La Vende. These weren’t glamorous breakthroughs. But they were proof of something essential: Toyoji had built an organization that could invent, manufacture, and win in the market.

In 1941, he took the next step and established Nihon Eisai Co., Ltd. The timing could hardly have been worse. Japan was sliding toward World War II. But Toyoji pressed forward anyway. By 1944, Nihon Eisai merged with the Sakuragaoka research organization, forming the company that would become Eisai Co., Ltd.

Even the name carried intent. “Eisai” evokes hygiene and sanitation—an expression of Toyoji’s belief that pharmaceuticals exist to protect human health at its most basic level. Decades later, Eisai would formalize that belief into what it called “human health care,” or hhc. But the impulse was there from the beginning.

Because this founding story isn’t just color. It set a pattern: family leadership, long-term thinking, investing ahead of the market, and a stubborn commitment to the people at the end of the supply chain.

Those traits would matter enormously later—when Eisai decided to take on Alzheimer’s, and refused to walk away for forty years.

III. The Vitamin Empire & Postwar Growth: Building the Foundation

The years immediately after World War II were chaos for Japanese industry, and Eisai wasn’t spared. Supply chains were broken, demand was unpredictable, and the country was rebuilding from the ground up. What Eisai did have, though, was something practical and dependable: deep expertise in vitamins, especially vitamin E. That turned into a lifeline. The company pushed through the postwar turbulence and grew quickly on the back of successful products—yet even with that momentum, it still wasn’t obviously ahead of the pack. By the mid-1950s, Eisai was doing well, but it wasn’t yet extraordinary.

So in 1957, Eisai tried to force the next leap. It rolled out its first three-year mid-term plan—a signal that this wasn’t going to be a company content to simply ride the vitamin wave.

The company had already taken a symbolic step two years earlier. In 1955, it dropped “Nihon” from its name, becoming Eisai Co., Ltd. It’s a small change on paper, but it reads like an identity shift: less a domestic maker with a long formal name, more a brand with room to grow.

Then came the moment that can make or break family-led businesses: succession. Eisai handled it cleanly. On May 14, 1966, Yuji Naito took over as president. Japan was entering a period of rapid economic development and growing internationalization, and Eisai used the tailwinds to professionalize and expand. Over the years that followed, it built out a nationwide distribution network, anchored by branches in 12 locations.

But Toyoji Naito’s ambitions weren’t only commercial. He had a broader frustration with the Japanese pharmaceutical industry: too much importing, too much imitation, not enough original science. And he believed the bottleneck wasn’t talent—it was support. Applied research could find funding. Basic research often couldn’t, even when the scientists were world-class.

In 1969, he acted on that belief by establishing the Naito Foundation. Its purpose was straightforward and deeply strategic: give researchers backing for the kind of foundational work that doesn’t pay off quickly, but makes truly original medicines possible. In other words, Toyoji wasn’t just building Eisai. He was trying to help build the ecosystem Eisai would need to thrive in.

The 1970s brought another tailwind. As public awareness of health and safety rose in Japan, vitamin E gained attention as a way to prevent lifestyle diseases and mitigate the effects of aging. Eisai, already confident in its vitamin E pedigree, introduced Juvelux in 1977 and leaned into the moment.

Then, in the early 1980s, Eisai made a move that mattered far more than any single product launch: it began building the company it wanted to become.

In 1981, as the first step in expanding into the United States, Eisai established a local subsidiary, Eisai U.S.A. Inc., in suburban Los Angeles. At the same time, it began laying down serious infrastructure at home, opening major new hubs over the next few years: the Misato Plant in Saitama, the Tsukuba Research Laboratories in Ibaraki, and Eisai Chemical Co., Ltd.

Of those, Tsukuba would matter most. Because in 1983, inside that new research lab, Eisai launched a project that would quietly become the organizing mission of the entire company—one that would eventually reshape Eisai’s future, and push Alzheimer’s treatment into a new era.

IV. The Haruo Naito Era & The Audacious Top-20 Plan

By 1987, Japan’s bubble economy was swelling, “internationalization” was on every executive’s lips, and Eisai was ready to stop thinking of itself as a strong domestic company and start acting like a global contender.

That year, leadership passed to Haruo Naito, the third generation of the Naito family. His father, Yuji Naito, stepped aside, and Eisai entered its next era of long-term planning. At the time, Eisai ranked 30th among pharmaceutical companies worldwide. Haruo’s answer wasn’t to protect that position. It was to outgrow it.

Eisai set a clear, almost provocative target: break into the world’s top 20 drug makers by 2001. Not with a splashy merger. Not by buying its way in. By changing what it was capable of creating.

To get there, the company mapped the next 15 years and kicked it off with what it called the “First Five-Year Strategic Plan.” The point wasn’t the name. The point was the discipline: Eisai was going to run on a clock that measured decades, not quarters.

Haruo Naito’s rise inside the company had been unusually systematic. He joined Eisai in October 1975. By 1987 he was Representative Director and Deputy President. In April 1988, he became Representative Director and President. Along the way, he’d moved through roles tied closely to research and development—R&D promotion, then General Manager of R&D—before taking on the broader executive mandate.

That background mattered, because Haruo brought a very specific belief to the top job: that the people who should sit at the center of a pharmaceutical company’s decision-making weren’t shareholders or regulators, but patients.

In 1989, that belief became doctrine. Eisai formalized its corporate philosophy around “human health care,” or hhc—a commitment to patient-centered innovation, especially for unmet medical needs and the reduction of health disparities.

And in Eisai’s case, hhc wasn’t just a slogan to paste on the wall. It became the internal logic for decisions that would look irrational under a normal corporate lens: staying in diseases other companies were walking away from, investing in hard science with uncertain payoffs, and accepting that some of the most important work would take far longer than any five-year plan could capture.

Haruo pushed that culture into the day-to-day life of the company. Employees were encouraged to spend time with patients—to understand the fear, the frustration, the loss of dignity—and to let that experience shape what Eisai chose to build. Over time, Eisai concentrated innovation where unmet need was most severe, particularly in dementia and oncology.

By 2025, Haruo Naito was still CEO—an extraordinary tenure of more than 35 years. That same year, Eisai announced he had been selected to receive the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star at the 2025 Spring Conferment of Decorations, with the conferral ceremony scheduled for May 9, 2025, at the Imperial Palace.

For anyone trying to understand Eisai, Haruo is the key. His leadership normalized patience inside the company: the willingness to keep funding programs that were unpopular, to absorb criticism in the short term, and to measure success by patient impact as much as financial performance. That mindset would soon collide with the hardest problem in medicine—and the one Eisai had already started to chase.

V. The Aricept Revolution: Creating a Blockbuster from Skepticism

Every pharmaceutical company talks about finding a blockbuster. Very few do. And almost none do it by charging straight into a disease that, at the time, much of the scientific world treated as a dead end.

Aricept was Eisai’s breakout—and it started with one chemist and a very personal reason to keep going.

Hachiro Sugimoto wasn’t chasing Alzheimer’s because it was fashionable, or because it looked like a sure thing. His mother developed dementia later in life. When he visited, she would look at him and ask, “Young man, who are you?” He would answer, “Mom, it’s me, your son Hachiro,” and she’d respond, “Oh, you don’t say? My son’s name is Hachiro. You both have the same name.” The cruelty of it wasn’t just the memory loss—it was the collapse of recognition, the way the relationship itself seemed to evaporate.

Sugimoto carried that with him. And it hardened into a mission: as a scientist, he would try to create a drug that could help Alzheimer’s patients, even though Alzheimer’s was already notorious as one of the most difficult diseases to treat.

Eisai began the research that led to donepezil in 1983. Sugimoto led the team. Thirteen years later, in 1996, Eisai received FDA approval in the United States for donepezil under the brand name Aricept—co-marketed with Pfizer. It was the kind of partnership that instantly changed the commercial math: Eisai had the science, Pfizer had one of the most powerful sales forces on earth.

The scientific context matters here. In the early 1980s, the prevailing Alzheimer’s hypothesis centered on acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter tied to memory function that appeared depleted in Alzheimer’s patients. The idea was straightforward: if you could slow the breakdown of acetylcholine by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, maybe you could preserve cognition.

The problem was that the available drugs in that class were a mess. Early acetylcholinesterase inhibitors like physostigmine and tacrine showed modest improvements in cognitive function, but they came with major drawbacks. Physostigmine had poor oral activity, limited brain penetration, and weak pharmacokinetics. Tacrine carried hepatotoxic liability. In other words: a hint of benefit, paired with reasons physicians and regulators would hesitate.

Sugimoto’s team needed something better—effective, tolerable, and workable as a real medicine.

They found their starting point through what looks, in hindsight, like luck. During random screening for compounds that inhibited acetylcholinesterase, they stumbled across a seed compound almost by accident—one that had originally been synthesized for a different purpose. But that “mere coincidence” only mattered because the team recognized what they had and then did the hard part: years of chemistry and iteration to turn a promising hit into a drug.

They pushed the compound forward through chemical synthesis and, by 1985, produced a new lead with higher efficacy. Then came the kind of setback that kills plenty of programs: the pharmacokinetics didn’t cooperate. Low bioavailability threatened the whole effort. But they kept at it, working through the issues until they arrived at E2020—the compound that became Aricept.

Inside Eisai, even that persistence wasn’t guaranteed. Tsukuba Research Laboratories were organized by disease field, with six laboratories total, which created a natural internal competition. Sugimoto’s group sat in the Brain and Nerve Unit in Laboratory II, split into a Chemistry Group and a Biology Group. The Chemistry team synthesized compounds and sent them over for evaluation; the Biology team had limited capacity to test them. Friction was inevitable. Discussions turned heated. Sometimes they were close to arguments.

And then, night after night, a senior leader would drop by.

Haruo Naito—then a senior director at Tsukuba—made a point of stopping in the evenings to encourage the team. It’s a small scene, but it reveals something structural about Eisai: this wasn’t a “come back when you have data” culture. Top management was present in the uncertainty, when morale and conviction mattered as much as technical skill.

FDA approval arrived in November 1996, thirteen years after Eisai started the work. Aricept went on to become one of the most successful Alzheimer’s drugs in history—and it helped propel Eisai into the global ranks it had been aiming for.

It also reshaped Eisai’s business in a way that was both triumphant and dangerous. As of March 2010, Aricept accounted for 40% of Eisai’s revenue. That’s not just a hit product. That’s gravity. It pulled the whole company’s financial future into one orbit—and it meant that when the patents eventually expired, Eisai wouldn’t just face a headwind. It would face a cliff.

Aricept validated Haruo Naito’s Top-20 strategy. Eisai had built something world-class. But it also concentrated risk in the most unforgiving way possible: a single drug, a single franchise, and a countdown clock the company couldn’t stop.

And when that clock started to run out, Eisai’s next decision would determine whether it remained a global contender—or became another cautionary tale of a pharma company that peaked with one blockbuster.

VI. The Pivot to Oncology: Diversification & Acquisitions

By the mid-2000s, Eisai’s leadership could see the problem coming from miles away. Aricept had made the company. But patents don’t last forever, and once generics arrived, the revenue base that had powered Eisai into the global ranks was going to get hit hard. Eisai needed a second engine—fast. The answer was oncology.

This wasn’t a brand-new interest. Eisai had begun in-house oncology research back in 1987, and over time it built up hard-won, proprietary know-how through plenty of trial and error. That work would eventually yield drugs like eribulin (Halaven) and lenvatinib (Lenvima). But the timelines in cancer are long, and Eisai didn’t have the luxury of waiting for the lab alone to refill the pipeline.

So it did what a mid-sized company trying to become a global one often has to do: it bought capability.

In 2006, Eisai signed an agreement with U.S.-based Ligand Pharmaceuticals to acquire four oncology-related products—its first real step into building an oncology portfolio and a commercial footprint to support it. The following year, Eisai acquired Morphotek, a biopharmaceutical company focused on antibody drug R&D, with multiple antibody therapeutics for cancer in development.

Then came the big swing: MGI Pharma.

Eisai and MGI announced a definitive merger agreement under which Eisai would acquire all outstanding shares of MGI in an all-cash deal—US$41.00 per share, totaling about $3.9 billion. When the acquisition closed in December 2007, Eisai didn’t just pick up a logo and a mailing address. It gained real oncology products: Dacogen (decitabine), Aloxi (palonosetron), Hexalen (altretamine) for ovarian cancer, and the Gliadel Wafer (carmustine) for brain tumors.

For Eisai, this was a transformative bet—nearly $4 billion spent by a company best known for neurology. But it bought something Eisai urgently needed: an immediate U.S. oncology portfolio, and the specialized commercial muscle to sell cancer medicines in the world’s most important market.

At the same time, Eisai’s internal R&D started to pay off in a way that reinforced the entire strategy. The clearest example was Halaven. Discovered and developed by Eisai, Halaven is a non-taxane microtubule dynamics inhibitor and a synthetic analog of halichondrin B, a natural product isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai. Its FDA approval was based on results from the global pivotal Phase III study EMBRACE.

And the backstory reads like classic drug development insanity: researchers discovered anticancer activity in halichondrin B, a compound found in a black sea sponge off Japan’s coast—but the supply problem was brutal. A collection arrangement was even put in place to harvest the sponge, only for scientists to learn that one metric ton of sponges would yield just 300 mg of the compound. If Halaven was going to exist as a real medicine, it couldn’t depend on harvesting the ocean. The only viable path was synthesis—and after years of work, Eisai got there.

In 2010, Halaven received FDA approval for metastatic breast cancer, becoming the first new chemotherapy option for those patients in years.

But the oncology move that carried the biggest long-term strategic weight came later, through partnership rather than acquisition. In early 2018, Eisai and Merck agreed to a worldwide collaboration to co-develop and co-commercialize Lenvima, an orally available tyrosine kinase inhibitor discovered by Eisai. Around the same time, the companies announced that the FDA had granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation for the Lenvima/Keytruda combination in advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

The deal terms underscored what Eisai had built. Merck would pay Eisai an upfront $300 million, additional option-rights payments and R&D reimbursements, plus milestone payments that—if everything hit—could add up to several billion dollars.

Strategically, it was a clean fit: Eisai brought Lenvima, born at Tsukuba. Merck brought Keytruda, the defining immuno-oncology drug of the era. Together, they created a combination neither company could have fully realized on its own.

From the outside, the oncology pivot can look like “diversification.” From the inside, it was survival planning with intent: Eisai staring down the Aricept patent cliff and choosing to spend aggressively, build quickly, and partner smartly—so the company wouldn’t be remembered as a one-blockbuster story.

VII. The Patent Cliff & The Existential Bet

The Aricept patent expiration wasn’t a surprise. In pharma, you can see the cliff coming years out. What made Eisai different was what it refused to do next: run away from the therapeutic area that had made the company.

Once generics arrived, Aricept’s dominance couldn’t hold. A key rival was a generic version from Ranbaxy Labs, and Eisai did what every experienced drugmaker does in this situation: it tried to stretch the franchise. New formulations and other lifecycle strategies could buy time at the margins.

But they couldn’t change the ending. The revenue decline was coming. The only question was what Eisai would build in Aricept’s shadow.

For most companies, the rational move would have been to back away from neurology—especially Alzheimer’s. By the early 2010s, Alzheimer’s drug development had become a kind of industry graveyard: expensive trials, repeated failures, and growing doubt about the amyloid hypothesis itself—the idea that Alzheimer’s is driven by the buildup of beta-amyloid in the brain. Major pharma companies were taking their losses and moving on.

Eisai chose the opposite path. It doubled down.

And it didn’t do it alone. Eisai’s long-running relationships with research partners became the bridge from the Aricept era to whatever came next.

One of the most important started in 2005, when Sweden’s BioArctic entered into a research collaboration with Eisai. Two years later, the relationship deepened: Eisai signed a license agreement tied to an antibody program that would ultimately lead to lecanemab, a potential disease-modifying approach for Alzheimer’s. Under that agreement, Eisai obtained global rights to research, develop, and commercialize treatments using lecanemab.

BioArctic’s science targeted a particularly toxic form of amyloid beta known as protofibrils. Eisai held the global licensing rights from 2007 onward. Later, together with Biogen, Eisai would take responsibility for commercializing the resulting medicine—Leqembi—worldwide.

Then, in 2014, Eisai expanded its Alzheimer’s development effort again, announcing a collaboration with Biogen Idec to develop and commercialize two of Eisai’s clinical candidates for Alzheimer’s disease: E2609 and BAN2401.

In the partnership, Eisai would serve as the operational and regulatory lead and pursue marketing authorizations worldwide. In major markets like the United States and the European Union, Eisai and Biogen would co-promote after approval. Both companies would share costs, with Eisai booking sales for E2609 and BAN2401 and profits split between the partners.

The partnership also signaled something important about Eisai’s reputation in the field. Biogen didn’t frame Eisai as a convenient co-developer. It framed Eisai as the rare company that had actually delivered in Alzheimer’s before: “Eisai is a pioneer in successfully developing and commercializing AD treatments. This history, combined with their strong scientific heritage, geographical reach and unwavering commitment to the AD community, makes Eisai an excellent collaboration partner to help drive our mission.”

This is Eisai at its most instructive. With an existential threat approaching as Aricept’s patents expired, the company could have protected margins, cut risk, and slowly drifted into the second tier of global pharma. Instead, it used the credibility Aricept had earned—scientific, regulatory, and commercial—to bring world-class partners into the next generation of Alzheimer’s therapies.

It was a bet that would take another decade to pay off.

VIII. The Leqembi Journey: A Four-Decade Quest Realized

When Eisai and Biogen released their Phase 3 results in September 2022, the Alzheimer’s world didn’t just lean in. It did a double take.

Their Clarity AD study hit its primary endpoint and key secondary endpoints. Analysts at Evercore ISI called it a “major surprise,” and in context, that wasn’t hype. It was disbelief giving way to recognition that something in Alzheimer’s had finally moved from theory into evidence.

The trial enrolled 1,795 people with early Alzheimer’s. Participants received either lecanemab—an antibody designed to clear amyloid-beta aggregates—or placebo, given intravenously twice a month. After 18 months, lecanemab slowed cognitive decline by 27% versus placebo, with statistical significance that left very little room for wishful thinking.

After decades of high-profile failures, an anti-amyloid therapy had, at last, produced clear clinical benefit in a large, rigorous trial.

Then the regulatory machinery started to turn—fast, by Alzheimer’s standards.

LEQEMBI, a humanized immunoglobulin gamma 1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody directed against aggregated soluble (protofibril) and insoluble forms of amyloid beta (Aβ), received accelerated approval on January 6, 2023, and launched in the U.S. on January 18, 2023. That accelerated approval was based on Phase 2 data showing LEQEMBI reduced Aβ plaque in the brain—a defining biological feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

But the milestone that mattered most arrived six months later. On July 6, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration converted Leqembi (lecanemab-irmb) to traditional approval after determining that the confirmatory trial verified clinical benefit. Leqembi became the first amyloid beta-directed antibody to make the jump from accelerated approval to traditional approval for Alzheimer’s disease.

The FDA approved the supplemental Biologics License Application (sBLA) supporting traditional approval of LEQEMBI (lecanemab-irmb) 100 mg/mL injection for intravenous use, making LEQEMBI the first and only approved treatment shown to reduce the rate of disease progression and to slow cognitive and functional decline in adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

And the approval wasn’t just a regulatory technicality. The clinical readout translated into daily life. In Clarity AD, LEQEMBI reduced clinical decline on CDR-SB by 27% at 18 months compared to placebo. On a key secondary endpoint, the AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment (ADCS MCI-ADL)—as assessed by caregivers—patients on LEQEMBI showed a statistically significant 37% benefit. In plain terms, that meant more ability to function independently: dressing, feeding themselves, and staying engaged in community activities.

Coverage, though, would determine whether this breakthrough reached patients—or stayed a headline.

After traditional approval, Medicare broadened coverage for Leqembi. CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure framed it as both access and learning: “CMS today affirms our commitment to help people with Alzheimer’s disease have timely access to innovative treatments that may lead to improved care and better outcomes… With FDA’s decision, CMS will cover this medication broadly while continuing to gather data that will help us understand how the drug works.”

Then came the rest of the world.

Lecanemab has been approved in the U.S., Japan, China, South Korea, Hong Kong, Israel, UAE and Great Britain for the treatment of MCI due to AD and mild AD dementia. Europe took longer. Eisai requested a marketing license for lecanemab, faced an initial rejection from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and then navigated a series of additional reviews and delays as the application moved through other committees. Ultimately, on April 15, 2025, the European Commission approved it—granting a marketing authorisation valid throughout the EU.

For investors, Leqembi was the validation of a four-decade commitment to Alzheimer’s research. But validation isn’t the same thing as commercial success—which brings us to the realities of the launch.

IX. The Controversy & The Trade-offs: What Leqembi Means

Leqembi is not a cure. And to understand what Eisai has actually achieved here—and what it hasn’t—you have to separate “first” from “finished.”

In the Phase 3 Clarity AD trial, Leqembi delayed cognitive decline by about 5.3 months compared to placebo after 18 months of treatment. That benefit shows up in the headline number too: a 27% slowing of decline versus placebo over the same period. For families living inside Alzheimer’s, those months can be the difference between recognizing loved ones a little longer, staying independent a little longer, and holding onto daily routines that the disease steadily strips away.

But the limits matter just as much as the milestone. Leqembi doesn’t stop Alzheimer’s. It doesn’t reverse it. And it doesn’t help everyone. It’s administered twice a month through intravenous infusion, and it asks patients and health systems to commit to a long, monitored course of treatment for a benefit that, while meaningful, is still measured in months.

The harder conversation is safety.

The most common side effects in Leqembi’s labeling include headache, infusion-related reactions, and amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA—a known risk with this class of anti-amyloid antibodies. ARIA can show up as temporary swelling in the brain (ARIA-E) and can also be accompanied by small areas of bleeding in or on the surface of the brain. Often ARIA causes no symptoms and is only seen on imaging, but it can produce symptoms like headache, confusion, dizziness, vision changes, and nausea. In rarer cases, ARIA can be serious and life-threatening, including severe brain edema associated with seizures and other serious neurological symptoms. Intracerebral hemorrhages can occur with this class of medications and can be fatal.

This is why monitoring is not optional. Earlier detection through imaging can identify ARIA-E—brain swelling or fluid buildup—before it becomes dangerous. ARIA-E is often asymptomatic, but serious and life-threatening events, including seizure and status epilepticus, can occur, and there have been deaths. The Alzheimer’s community has been aware of this risk alongside the drug’s promise from the beginning.

Europe’s regulatory process put these trade-offs under a microscope.

On July 25, 2024, the EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a negative opinion on Leqembi, recommending that the European Commission refuse marketing authorization. The CHMP’s view came down to the cost-benefit balance: in its assessment, the difference in CDR-SB scores between Leqembi and placebo in Clarity AD wasn’t large enough to justify use given the risk of serious adverse events.

Eisai didn’t walk away. It came back with a revised application that excluded higher-risk patients. After re-examining its initial opinion, the CHMP shifted in November—recommending Leqembi, but only for a narrower subgroup of patients with one or no copy of ApoE4.

Meanwhile, the launch itself has been bumpier than the historic approval might suggest.

Eisai lowered its sales outlook, and the commercial ramp has been slower than many expected—particularly in the U.S. Eisai said it now expects Leqembi sales of JPY 42.5 billion for the period, down from the JPY 56.5 billion it had announced earlier. Even as international markets have shown more momentum, U.S. sales have continued to lag, and the EU’s July 2024 negative opinion added fuel to ongoing skepticism about whether the benefits “counterbalance” the safety risks.

The reasons aren’t mysterious—they’re operational.

Leqembi isn’t a prescription you pick up at a neighborhood pharmacy. Patients need access to infusion centers every two weeks. They need regular MRI scans to monitor for ARIA. Physicians need familiarity with a safety profile that requires vigilance and clear protocols. In other words, Leqembi doesn’t just require a drug label and reimbursement. It requires an ecosystem—and that ecosystem is still being built.

For investors, that’s the lesson in plain sight. Scientific validation doesn’t automatically become commercial scale. There’s often a wide gap between what a therapy can do in a controlled clinical trial and what it can do inside real healthcare systems—with real capacity constraints, real patient selection, and real risk tolerance.

X. Current Strategy, Competitive Position & Investment Considerations

The Current Business Model

Eisai now runs the company around two pillars: neurology and oncology.

Financially, 2024 was a year of growth. Eisai reported revenue of 789.40 billion, up from 741.75 billion the year before, and earnings of 46.43 billion, up 9.49%. In another set of reported figures, total revenue rose 4% year over year to 400 billion JPY, while operating profit increased 23.6% to 34.4 billion JPY—helped by a sharp increase in global LEQEMBI performance.

Strategically, oncology is the stabilizer. The franchise—most notably the Merck partnership around Lenvima—brings recurring revenue and keeps Eisai tied into one of the most important commercial ecosystems in modern pharma.

Neurology is the differentiator. Leqembi is the flagship, but Eisai also has established products like Dayvigo for insomnia. In a field where many large competitors have stepped back after years of failure, Eisai’s willingness to stay in the fight has become a competitive position in itself.

Competitive Dynamics

The Alzheimer’s market is no longer a one-company story. In 2024, Eli Lilly’s Kisunla (donanemab) received FDA approval, putting a direct competitor into the same new, infrastructure-heavy category Leqembi helped create.

And importantly: Lilly has faced many of the same rollout realities. The company has described slow uptake, with Kisunla bringing in $8 million in the fourth quarter and about 800 prescribers so far. As Lilly Neuroscience president Anne White put it on an earnings call, “The true challenge here is health healthcare systems’ readiness.”

That’s the tell. If a pharma giant with massive commercial scale is still running into friction, then the constraint isn’t Eisai’s sales execution. It’s the system: infusion capacity, MRI access, clinic workflows, and the operational burden of monitoring.

Bull Case

Eisai’s optimistic case rests on a few powerful tailwinds:

First-mover advantage in disease-modifying Alzheimer’s treatment. Leqembi reached the market ahead of key competitors, giving Eisai a head start building treatment pathways, training clinicians, and plugging into the infusion-and-imaging infrastructure that this entire category requires.

Pipeline depth in Alzheimer’s. Eisai completed a lecanemab subcutaneous bioavailability study, and subcutaneous dosing is being evaluated in the Clarity AD (Study 301) open-label extension (OLE). Separately, since July 2020, Eisai’s Phase 3 AHEAD 3-45 study has been ongoing in preclinical Alzheimer’s—people who are clinically normal but have intermediate or elevated levels of amyloid in the brain. A subcutaneous option could make treatment far easier to deliver. A preclinical indication, if it ever becomes real, would expand the market dramatically.

Oncology diversification. The Merck partnership and Eisai’s internal oncology capabilities reduce the company’s dependence on any single neurology outcome.

Japanese corporate governance advantages. Eisai’s family control and unusually long-tenured leadership have enabled multi-decade research commitments that would be difficult for more short-term, market-driven organizations to maintain.

Bear Case

The risks are just as real:

Leqembi commercial underperformance. If capacity and monitoring requirements remain bottlenecks, Leqembi could stay stuck below blockbuster scale even with strong clinical validation.

Safety concerns. ARIA is not an abstract issue—it’s the central risk of this drug class. High-profile adverse events could chill adoption, and the EU’s initial negative view underscored how differently regulators can judge the same risk-benefit trade.

Competition. Lilly is a formidable competitor with greater commercial reach. And more entrants could follow, potentially with better convenience, improved efficacy, or cleaner safety profiles.

Pricing and reimbursement. The roughly $26,500 annual list price creates access and affordability pressure, even if it’s lower than many specialty drugs. In Europe, even with EU-level authorization, reimbursement is decided country by country, which can turn “approved” into a long, fragmented march toward actual patient access.

Key person risk. Haruo Naito has led Eisai for more than 35 years. Succession is inevitable, and a change at the top could shift the culture that has historically rewarded patience, persistence, and long-cycle bets.

Key Metrics to Watch

For anyone tracking Eisai, a few indicators matter more than almost anything else:

-

Quarterly Leqembi patient starts and the cumulative number of patients on treatment. In the early years of a launch like this, patient counts can tell you more than revenue. They reveal whether access pathways are opening up—and whether the infrastructure is finally catching up to the science.

-

R&D spending as a percentage of revenue, especially in neurology. Eisai’s identity has been built on sustained research investment through difficult cycles. If that commitment meaningfully weakens, it would signal a strategic shift.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

Europe’s process made one thing clear: this drug class will live under intense regulatory scrutiny.

The most common side effects with Leqembi include infusion-related reactions, ARIA-H (small bleeds in the brain), and headache. ARIA-E—fluid accumulation or swelling in the brain—can also occur. Restrictions reflect that risk: Leqembi must not be used in people with inadequately controlled bleeding disorders, those receiving anticoagulant treatment, or when pretreatment MRI shows previous bleeds in the brain.

These constraints reduce the eligible patient pool. But they also point to the path regulators are trying to force the market down: narrower selection, tighter monitoring, and, ideally, a safer real-world profile—at the cost of simplicity and scale.

XI. Conclusion: The Patience Premium

Eisai’s story breaks the usual pharmaceutical playbook. A mid-sized Japanese company, led by the same family across three generations, stayed on one of medicine’s most punishing frontiers for forty years—through skepticism, failed trials, and an industry that kept declaring Alzheimer’s a dead end. And in 2023, that persistence produced Leqembi: the first traditionally approved treatment shown to slow cognitive and functional decline by targeting the underlying disease process.

Was it worth it?

From the patient’s perspective, yes. For people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, Leqembi represents an option that simply didn’t exist before. The clinical benefit is measured in months, not miracles—about five additional months of delayed decline over an 18-month period in the Phase 3 study—but in a disease defined by steady loss, months matter. They can mean more time recognizing loved ones, more time managing daily life, more time being yourself.

From the investment perspective, the answer is messier. Eisai’s breakthrough hasn’t automatically translated into runaway stock performance. The launch has been slower than many expected, and the path to true blockbuster revenue is still constrained by the real world: infusion capacity, MRI access, careful patient selection, and a safety profile that requires vigilance.

But that may be the wrong yardstick for what Eisai actually built.

Because the real payoff of a forty-year commitment isn’t just one antibody. It’s the accumulated capability: deep expertise in Alzheimer’s biology, hard-earned credibility with regulators, durable partnerships, and the beginnings of an end-to-end treatment ecosystem. The subcutaneous formulation work, the preclinical trial program, the next wave of neuroscience efforts—those don’t appear out of nowhere. They come from the same institutional muscle that began at Tsukuba in 1983 and never fully let go.

And that brings us back to Eisai’s organizing idea, in Haruo Naito’s own words:

Since assuming the position of Representative Director and President of Eisai Co., Ltd. in 1988, I have established that patients are the main figures in healthcare. By having our employees spend time with the patients to understand their anxieties, and driven by a strong desire to relieve them somehow, we have been promoting the creation of innovations to meet unmet needs, particularly in the dementia and oncology areas. With a strong belief in delivering these new treatments to patients who need them regardless of the healthcare system or income level of each country, I have worked to improve access to medicines in countries including developing and emerging nations.

Those lines explain why Eisai stayed in Alzheimer’s when others left. It wasn’t stubbornness for its own sake. It was a choice to build around patients, even when the business case looked fragile and the science looked controversial.

Whether that philosophy survives a leadership transition, whether it can reliably produce returns that match more conventionally managed peers, whether Eisai’s model is repeatable or a once-in-a-generation exception—those questions are still open.

What isn’t open is the central lesson of the story. In pharmaceutical R&D, the world is full of smart strategies and elegant theories. Sometimes the rarest advantage is simpler: the willingness to keep going after everyone else has stopped.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music