Shionogi & Co., Ltd.: The 147-Year-Old Drug Discovery Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

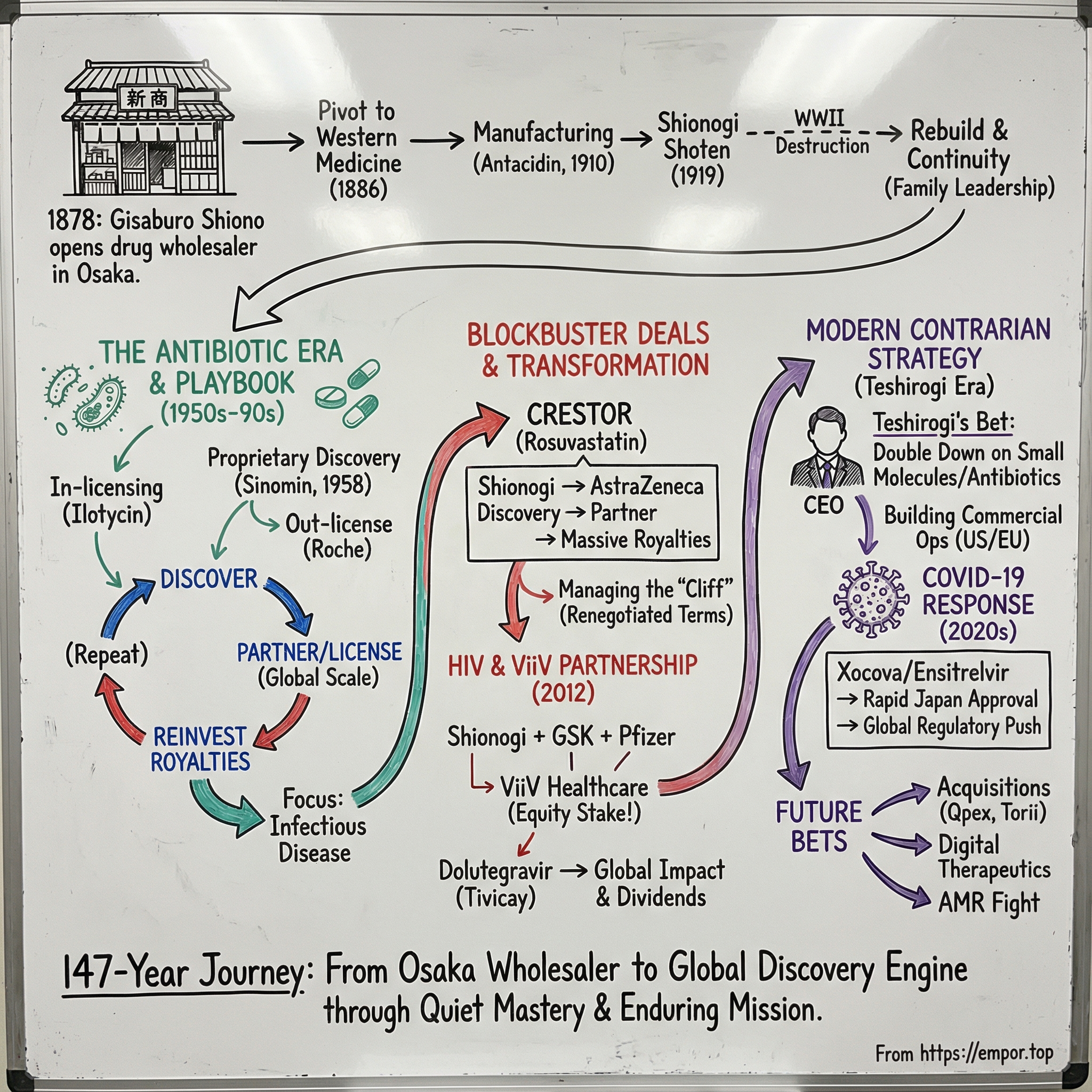

Picture Osaka in the 1870s, rain coming down in sheets, and the narrow streets of Doshomachi—the city’s historic medicine district—packed with merchants moving remedies that had been traded there for centuries. On March 17, 1878, a 24-year-old named Gisaburo Shiono marked his birthday by opening a drug wholesaling business. No celebration. Just a storefront, some inventory, and an instinct for where medicine was headed.

Nearly a century and a half later, that small operation had evolved into Shionogi & Co., Ltd.—a company that would help power some of the world’s most important HIV medicines, race an oral COVID antiviral to approval in Japan, and make one of the most contrarian bets in modern pharma: staying committed to antibiotics and other small-molecule infectious disease drugs while much of the industry sprinted toward biologics, gene therapies, and ultra-premium specialty treatments.

More than 145 years after Shiono Gisaburo Shoten opened in Doshomachi, most people outside Japan still wouldn’t recognize the name Shionogi. But they might recognize what came out of its labs—or what its science enabled. If you’ve heard of Crestor for cholesterol, or Tivicay for HIV, or benefited from the antibiotic wave that reshaped postwar medicine, you’ve been touched by Shionogi’s work, even if you never saw its logo.

This is a story about quiet mastery. A company that repeatedly discovered high-value molecules—and then, instead of building a massive global sales machine, handed commercialization to bigger partners. A company that learned to live with the pharmaceutical equivalent of gravity: patent expirations that can yank the floor out from under a business. And a company that built a playbook around that reality—using licensing, royalties, and disciplined reinvestment to keep its research engine compounding.

It’s also the story of a CEO willing to be unfashionable. Isao Teshirogi told Bloomberg that Shionogi would buck the industry’s trend toward more complex, more expensive therapies and focus instead on less complex treatments such as antibiotics. In a world where many pharma leaders hunt for the next ultra-high-priced breakthrough, Teshirogi took heat for choosing categories that outsiders called “cheap” or “old.” “People were asking if I was crazy,” he said. Shionogi kept going anyway.

And the results have been hard to ignore. Shionogi earns a large share of its money from royalties rather than direct sales, yet it has posted four straight years of record operating profit and an operating profit margin around 38%—one of the strongest in Japan’s drug industry.

So here’s what we’re digging into: How did a 19th-century Osaka medicine wholesaler become a modern global R&D engine? Why did out-licensing work so well for so long—and where does that model start to creak? And can Shionogi keep winning by doubling down on infectious diseases in an era increasingly dominated by biologics, gene therapies, and AI-fueled discovery?

II. Founding & Early History: From Medicine Wholesaler to Manufacturer (1878–1945)

Gisaburo Shiono didn’t stumble into medicine. He apprenticed in it—learning the wholesaling trade from his father, Kichibei, who ran a drug wholesale business of his own. Then, on March 17, 1878—his 24th birthday—Gisaburo opened shop: Shiono Gisaburo Shoten, in Doshomachi 3-chome 12 in Osaka, right in the city’s historic medicine district.

Osaka was already Japan’s commercial engine, and Doshomachi was where remedies moved. In the beginning, Shiono Gisaburo Shoten did what the neighborhood had done for generations: it supplied local distributors with traditional Japanese and Chinese medicines—herbal and folk remedies that had been widely used for more than a thousand years.

But Gisaburo had a feel for where demand was shifting. In the 1880s, Western medicine started to move from novelty to mainstream. By 1886, just eight years after opening, he made a decisive pivot: he shifted the business toward Western medicines.

That decision was smart—and hard. Western drugs were already coming into Japan through foreign trading houses in Yokohama and Kobe, but they were expensive. Most Japanese wholesalers didn’t know the trading game well enough to negotiate; they paid whatever price the foreign merchants named. Gisaburo found a workaround: he partnered with an experienced businessperson fluent in English, which let him import pharmaceutical products directly from overseas. With that supply chain advantage, he could sell at prices that ordinary patients could actually afford.

Here’s the key: even then, Shionogi’s edge wasn’t only what it sold. It was the system—how efficiently it sourced and delivered. And when competitors caught up and began importing directly too, Gisaburo pivoted again. If trading alone wasn’t defensible, the next step was obvious: make the products yourself.

The shift from wholesaler to manufacturer didn’t happen overnight. It accelerated when Gisaburo’s second son, Chojiro, graduated from the Pharmaceutical Department of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceuticals at Tokyo Imperial University. With Chojiro’s scientific training, Shionogi began conducting full-fledged pharmaceutical research. An early catalyst came from the clinic: a supervising pharmacist heard from a chief pediatric physician at Osaka Prefectural Medical School about a prescription for an antacid agent. Chojiro began manufacturing trials, and the product sold. The result was Antacidin—an anti-indigestion drug that became Shiono Gisaburo Shoten’s first in-house product.

Success with Antacidin gave Gisaburo permission to think bigger. To support real manufacturing, the company built a pharmaceutical plant—Shiono Seiyakusho—in Nishinari-gun, Osaka. This was the moment Shionogi became a pharmaceutical company not just in aspiration, but in structure. The plant began operating in 1910, with Chojiro as director.

From there, the early portfolio took shape quickly. Antacidin established that Shionogi could turn research into product. Digitamin followed as its first cardiac drug. And Shionogi also began importing Salvarsan soon after it was developed overseas, helping bring a treatment for syphilis to Japan.

In 1919, Shiono Gisaburo Shoten and Shiono Seiyakusho merged into a newly formed company named Shionogi Shoten. It was the corporate framework that would carry the business into the modern era.

The company’s logo captured the philosophy it wanted to live by. It was derived from the fundoh, a stylized balance weight traditionally used to weigh medicine on a scale—an emblem of accuracy. But it was also meant to stand for honesty and trust. That wasn’t just branding language. From the beginning, Shiono Gisaburo Shoten treated reliability and trust as its most valuable “capital.”

Then came the stress test of the century. World War II forced a wartime renaming to Shionogi Seiyaku in 1943. In 1945, air raids devastated its main plant and equipment. Overseas offices were lost. Hyperinflation and frozen assets deepened the financial crisis.

And yet, the company didn’t disappear. Like many Japanese firms whose buildings and people were shattered by the end of the war, Shionogi moved immediately to reorganize and restore its product lines. It also had an advantage that mattered in moments like this: continuity. Gisaburo had groomed successors from within the family circle, and leadership stayed consistent through the rebuild. President Yoshihiko Shiono and Senior Managing Director Motozo Shiono—both direct descendants of the founder—guided the company into the mid-1990s.

That kind of family continuity, stretching across more than a century, gave Shionogi something most pharmaceutical companies never get to have: genuine long-term thinking. When leadership is anchored to a founding lineage, patience isn’t a slogan. It becomes culture.

III. Post-War Transformation & The Antibiotic Era (1945–1990s)

The postwar period didn’t just rebuild Shionogi. It reinvented it. The company went from a Japan-focused manufacturer to a serious player in one of medicine’s most consequential arenas: infectious disease. By 1953, Shionogi had planted a flag there—and it never really left.

The first steps were pragmatic. In 1952, Shionogi secured exclusive manufacturing and marketing rights in Japan for Ilotycin, an antibiotic discovered by Eli Lilly. A year later it launched Popon-S, a multivitamin supplement that became a major product at home. These weren’t flashy scientific moonshots, but they mattered. They taught Shionogi how to work with Western pharmaceutical companies, how to manufacture at scale, and how to operate in categories where quality and trust were non-negotiable.

Then came the turn that would define Shionogi’s identity: proprietary antibiotics. In 1958, it launched its first sulfa drug under the name Sinomin, and the early success did something powerful inside the organization—it proved that Shionogi could originate products, not just produce them. In 1959, Shionogi introduced its own sulfonamide antibiotic and soon out-licensed it to Roche.

That one move became a blueprint. Discover the molecule, do enough work to prove it, then hand global distribution to a partner that already had the muscle. It wasn’t the most glamorous route, but it was efficient—and it let Shionogi keep compounding what it was best at: discovery.

Over the following decades, the antibiotic franchise grew into a calling card. Shionogi developed Shiomarin, the world’s first oxacephem antibiotic. And in 1989, it launched Flumarin, an internally developed antibiotic that quickly rose to a top position among the world’s antibiotics. Inside Japan, Shionogi became widely known as an antimicrobial and antibiotics company—an identity most drugmakers would later abandon.

Because by then, the antibiotic business was turning into a paradox. The medical need was enormous, but the market dynamics were brutal: resistance was rising, growth was slowing, and much of Big Pharma began backing away from the category. Shionogi’s answer wasn’t to quit. It was to partner.

In 1988, Schering-Plough began marketing a new oral antibiotic developed by Shionogi. Deals like that expanded reach, but they also made something clear: Shionogi could invent excellent medicines, yet it didn’t have the global commercial infrastructure to push them everywhere on its own.

So the company did what disciplined, long-horizon operators do. It focused. It identified priority therapeutic areas and concentrated resources on infectious diseases, pain treatment, and metabolic diseases—less a spray-and-pray pipeline and more a deliberate allocation of R&D firepower.

By the early 1990s, roughly one-fourth of Shionogi’s employees were involved in R&D in some form. And the effort was showing up in results: from the mid-1980s to the end of the decade, sales climbed meaningfully, and net income rose as well.

More importantly, the shape of Shionogi’s modern playbook was now visible. Stick with infectious diseases. Build deep relationships with global partners. Keep investing through cycles that scare others away. That foundation set the stage for the company’s next act—the one that would put Shionogi’s science into medicine cabinets around the world.

IV. The Crestor Deal: How Out-Licensing Created a Blockbuster

If you want the cleanest example of Shionogi’s playbook—discover big, partner bigger, reinvest relentlessly—rosuvastatin is it. The molecule that became Crestor didn’t just turn into a blockbuster. It rewired Shionogi’s entire trajectory.

Shionogi discovered rosuvastatin and, crucially, owned the ’314 substance patent covering its active ingredient, rosuvastatin calcium. That patent wasn’t a footnote—it was the asset. But Shionogi also knew what it wasn’t: a company built to commercialize a global cardiovascular drug on its own.

So Shionogi did what it had learned to do over decades. It advanced the drug through mid-stage trials, then teamed up with AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca got the rights to sell Crestor everywhere except Japan, and Shionogi got what it valued most: a way to turn its research into global scale without building a global sales machine.

Because the unglamorous truth of pharma economics is that launching worldwide is an industrial operation. It takes a massive sales force, regulatory capabilities across dozens of countries, and marketing budgets that can rival what it cost to discover the drug in the first place. For a mid-sized Japanese company, trying to build that infrastructure from scratch could have swallowed the very R&D engine that made the molecule possible.

The outcome was exactly what Shionogi was optimizing for. Crestor became one of the world’s best-selling statins, and the royalty stream reshaped Shionogi’s financial profile. Crestor sales reached $4.5 billion in 2009, and in 2014 some analysts predicted it could climb as high as $8.6 billion. For Shionogi, that kind of success doesn’t just boost a year’s earnings—it funds a decade of research.

But every blockbuster comes with a timer attached. The key substance patent for Crestor was set to expire on January 8, 2016. And in pharma, that date isn’t a calendar event—it’s a cliff edge. When generics arrive, revenue can drop fast.

Shionogi had been preparing for years. Its medium-term business plans explicitly aimed to manage the “Crestor Cliff,” the expected fall in royalty income after patent expiry, while positioning the company for the next phase of growth.

As generic challengers lined up, AstraZeneca and Shionogi fought to defend the ’314 patent. Multiple generic manufacturers filed applications, triggering a wave of patent infringement lawsuits. At one point, AstraZeneca’s stock jumped more than 10% after a U.S. District Court judge upheld the effort to keep generics off the market before 2016.

The court ultimately found that “no inequitable conduct was committed by any Shionogi employee” and that the ’314 patent was “non-obvious and properly reissued.” The decision prevented the FDA from issuing final approvals for the generic applications before the patent expired.

Then Shionogi executed the next move: not science, but dealcraft. In 2014, AstraZeneca and Shionogi extended the global license agreement and modified the royalty structure, effective January 1. The new terms extended royalty payments beyond the 2016 patent expiry all the way through 2023, including a fixed minimum annual royalty to Shionogi from 2014 through 2020 in the low hundreds of millions of dollars.

In other words, Shionogi traded some upside before the patent expiration for durability after it. The cliff didn’t disappear—but it became a slope.

And inside Shionogi, there was an interesting, very human side effect. The company later acknowledged that the strong earnings performance after the Crestor Cliff boosted confidence—but also seemed to dull urgency. The revised royalty agreements didn’t strengthen the underlying business; they mainly shifted the center of gravity from Crestor to the HIV franchise of dolutegravir-based drugs. Even as profits held up, there was a creeping sense that the company had “beaten” the cliff simply because the numbers looked good.

It was a rare admission, and an important one: royalties can buy time. They can’t replace innovation. Shionogi still needed the next engine—and it was already building it.

V. The ViiV Healthcare Partnership: Shionogi's HIV Masterpiece

If Crestor proved Shionogi could win by out-licensing, the ViiV Healthcare partnership showed something even rarer: Shionogi could design the deal so it didn’t just get paid, it got to participate.

ViiV Healthcare is a British multinational pharma company focused on HIV treatment and prevention. It was formed in November 2009 as a joint venture between GSK and Pfizer, with both companies moving their HIV assets into the new entity. In 2012, Shionogi joined.

Here’s what made this different. Shionogi didn’t simply hand over rights and wait for a royalty check. It traded commercial rights for ownership. By December 2023, ViiV’s ownership was 76.5% GSK, 13.5% Pfizer, and 10% Shionogi.

That change sounds subtle, but it rewired the incentives. Shionogi wasn’t just a licensor anymore—it was a shareholder. So when ViiV grew, Shionogi benefitted two ways: royalties on the medicines it helped create, and dividends tied to ViiV’s overall success.

The molecule at the center of this was dolutegravir, commercialized as Tivicay. Discovered in Shionogi’s labs, dolutegravir became one of the defining HIV medicines of the last decade. ViiV Healthcare’s Head of R&D put it plainly: “Our 20-year relationship with Shionogi has been incredibly successful, producing what are arguably two of the most important HIV medicines of the last decade. Dolutegravir is now taken by 17 million people globally.”

And the impact didn’t stay confined to wealthy markets. Through licensing agreements with the Medicines Patent Pool, generic dolutegravir has reached tens of millions of patients in low- and middle-income countries.

Financially, the franchise became central to Shionogi’s post-Crestor life. Tivicay and three combination treatments marketed by ViiV accounted for about a third of Shionogi’s 364 billion yen ($3.4 billion) in revenue in the last financial year.

The partnership also didn’t freeze in time. ViiV later announced an exclusive collaboration and license agreement with Shionogi for S-365598, a third-generation investigational integrase strand transfer inhibitor that could support ultra long-acting HIV regimens. Under the terms, ViiV would make an upfront payment of £20 million to Shionogi, an additional £15 million upon achieving a clinical development milestone, and then pay royalties on net sales.

That “long-acting” piece matters. Daily pills work, but they can be emotionally and logistically hard—daily reminders of living with HIV, concerns about disclosure, and the grind of perfect adherence. Longer-acting regimens have the potential to ease that burden.

For Shionogi, this fits the identity it’s been building for decades. With more than 60 years of infectious disease R&D experience, it continues to work alongside ViiV, and it has positioned “Protect people from the threat of infectious diseases” as a key material issue—committing to comprehensive initiatives across the three major infectious diseases: HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria.

The broader lesson is the same one Crestor hinted at, but upgraded. If you don’t want to build global commercialization yourself, you can still capture meaningful upside—if your science is differentiated enough to negotiate for a seat at the table, not just a slice of the revenue.

VI. CEO Isao Teshirogi & The Contrarian Strategy

In April 2008, Isao Teshirogi became President and CEO of Shionogi, succeeding Motozo Shiono—a direct descendant of the founder. It was a quiet but meaningful handoff: less family stewardship at the top, more professional management, while keeping the same research-first DNA.

Teshirogi didn’t come in to “manage the portfolio.” He came in to push. Under his leadership, Shionogi drove global R&D and expanded its international business. After hitting the quantitative targets of its Shionogi Growth Strategy 2020 plan, first set in fiscal 2014, the company updated those targets in October 2016—and then reached them ahead of schedule.

What made Teshirogi stand out, though, wasn’t just execution. It was his willingness to take the unpopular side of the argument.

As much of the industry chased biologics, gene therapies, and ever-higher-priced specialty drugs, Teshirogi made a bet that looked almost backwards: double down on small molecules, especially in infectious disease. That’s not the sort of story that usually wins applause on quarterly earnings calls. Big Pharma is built to hunt big-margin therapies, and investors tend to reward the companies that do.

Still, there were hints that a contrarian approach could work. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, made its own pivot—finalizing an asset swap with Novartis and stepping away from pricier cancer treatments to focus more on areas like vaccines and consumer health.

Teshirogi’s contrarian philosophy wasn’t just talk. Early in his tenure, he made a move that would shape Shionogi’s future: buying its way into U.S. commercial capability. In 2008, Shionogi acquired Sciele Pharma, a specialty pharmaceutical company based in Atlanta, to build a stronger overseas sales foothold for products discovered in-house. In 2011, Shionogi merged Sciele with its smaller existing development organization in New Jersey, creating Shionogi Inc.—with a clear mandate to bring Shionogi innovation to U.S. patients.

It didn’t go smoothly at first. A hoped-for anti-obesity drug candidate, expected to be marketed in the U.S., was shelved, and Shionogi accelerated a reform of its U.S. business model and structure. In 2011, it effectively restarted the operation as Shionogi Inc. with new management. Then, in 2013, it launched Osphena—its first global new chemical entity that Shionogi Inc. filed, got approved, and introduced.

That sequence matters. It showed the cost of expanding globally—but also Teshirogi’s pragmatism. When the plan broke, he didn’t keep pretending it was fine. He rebuilt the operating model and moved forward with something Shionogi could actually execute.

Europe followed a similar buildout. In 2012, Shionogi Europe opened in London. In 2013, the company added affiliates in Italy and Spain. It registered Shionogi BV in the Netherlands in 2017, and in 2018 opened a German affiliate in Berlin. By 2020, Shionogi had added its fifth European office, in France.

In 2022, Shionogi established a new European headquarters on Herengracht in Amsterdam.

Piece by piece, this created something Shionogi historically didn’t have: real commercial infrastructure outside Japan. And that infrastructure would matter—because once you commit to being more than a licensor, you need the capability to launch, supply, and support products yourself, not just invent them.

VII. The COVID-19 Bet: Ensitrelvir/Xocova

When SARS‑CoV‑2 appeared in early 2020, Shionogi’s long, stubborn focus on infectious disease suddenly stopped looking old-fashioned and started looking like preparation. The company moved fast, teaming up with Hokkaido University to go after one of the virus’s most attractive targets: its main protease.

Ensitrelvir is a SARS‑CoV‑2 main protease inhibitor created through joint research between Hokkaido University and Shionogi. The virus relies on an enzyme called the main protease (3CL) to replicate; ensitrelvir aims to shut that replication down by selectively inhibiting the protease.

In Japan, the drug is known as Xocova. It received emergency regulatory approval in November 2022, and then full approval in March 2024, for the treatment of COVID‑19.

The timing mattered. Japan’s emergency authorization came during the Omicron wave, when vaccines had reduced severe disease but infections were still widespread. Shionogi positioned ensitrelvir as the first antiviral to show both improvement in clinical symptoms and an antiviral effect in a vaccinated population infected with the Omicron variant.

Getting beyond Japan, though, was harder—and that’s where the story turns from pure R&D speed into regulatory endurance. Outside Japan, ensitrelvir remained investigational, with availability in Singapore via a Special Access Route application in 2023. It also moved into review with the European Medicines Agency for COVID‑19 post-exposure prophylaxis and treatment.

In the United States, the strategy centered less on treatment and more on prevention. SCORPIO-PEP became the headline: a global Phase 3 study evaluating a COVID‑19 oral antiviral as post-exposure prophylaxis—and Shionogi says it met its primary endpoint.

Shionogi reported that ensitrelvir significantly reduced the risk of symptomatic COVID‑19 in people exposed at home. Among 2,041 household contacts who tested negative at screening, 2.9% of participants receiving ensitrelvir developed symptomatic COVID‑19 by day 10, compared with 9% in the placebo group.

That dataset became the foundation for the U.S. regulatory push. Ensitrelvir was granted Fast Track designation by the FDA in 2025 for post-exposure prophylaxis of COVID‑19 following contact with an infected individual. Shionogi noted that COVID‑19 continued to be a public health threat in the U.S., with thousands of hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths each week.

In September 2025, Shionogi announced that the FDA had accepted a New Drug Application from Shionogi Inc. for ensitrelvir for the prevention of COVID‑19 following exposure. The FDA set an action date of June 16, 2026 under PDUFA. The NDA was supported by the global, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 3 SCORPIO-PEP study. If approved, Shionogi said ensitrelvir would be the first and only oral therapy for the prevention of COVID‑19 following exposure.

Back in Japan, Shionogi also filed additional applications in 2025: one for post-exposure prophylaxis, and another for COVID‑19 treatment in pediatric patients aged six to under 12 years.

Xocova captures both sides of Shionogi in one arc. On the one hand: the company could discover and develop a novel oral antiviral quickly and win approval at home. On the other: breaking into highly regulated Western markets meant playing by different evidentiary standards—and waiting through longer review timelines. If Shionogi clears that bar, the post-exposure prophylaxis indication could open a meaningful new commercial lane in a world where Pfizer’s Paxlovid has dominated.

VIII. Recent Strategic Moves & Future Bets

The last few years have been Shionogi in motion—big, opinionated moves that expand its footprint without abandoning the thing that made it matter in the first place: infectious disease.

The Qpex Acquisition and U.S. Research Expansion

Shionogi Inc. entered into a definitive agreement to acquire Qpex Biopharma, a privately held clinical-stage company focused on antimicrobial R&D. After the deal, Qpex became a wholly owned subsidiary. Isao Teshirogi framed the logic plainly: bacterial resistance remains one of the biggest threats to global health, and Qpex’s pipeline—including xeruborbactam—and its capabilities would accelerate Shionogi’s efforts to develop new antibiotic treatments to address antimicrobial resistance.

The acquisition, completed in 2023, brought Qpex’s internally discovered pipeline into Shionogi—most notably an investigational beta-lactamase inhibitor—and deepened Shionogi’s bench in antimicrobial discovery.

Then came a signal that Shionogi wasn’t just buying assets; it was planting roots. The company announced it would establish its first discovery laboratory in the U.S., in San Diego, positioning it closer to one of the world’s densest clusters of drug discovery talent. Shionogi made the announcement during a BIO panel discussion alongside industry and public health leaders, tying it directly to what it sees as an urgent global need for more antimicrobial innovation.

The stakes are hard to overstate. Antimicrobial resistance has been projected to cause up to 10 million deaths per year worldwide by 2050 if left unchecked, with annual treatment costs estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Shionogi’s point, implicitly, is that it has been in this fight for more than 60 years—and intends to stay one of the few large pharmaceutical companies still willing to do the work.

The Japan Tobacco Pharmaceutical Acquisition

In May 2025, Shionogi resolved to take on Japan Tobacco’s pharmaceutical business via a company split, acquire all issued shares of Akros Pharma Inc. through Shionogi Inc., and launch a tender offer for Torii Pharmaceutical to make it a wholly owned subsidiary.

In practical terms, Shionogi agreed to acquire Torii Pharmaceutical shares from Japan Tobacco through a tender offer and other means, while also purchasing Japan Tobacco’s U.S. pharmaceutical company, Akros. The total transaction value was estimated at roughly 150 billion to 160 billion yen, or about $1 billion.

Teshirogi described the deal as a way to “evolve our strengths as a drug-discovery pharmaceutical company,” calling it “a nearly ideal partnership” at a Tokyo press conference.

By September 1, 2025, Shionogi completed the acquisition of Torii, making it a wholly owned subsidiary through a sequence of steps: the tender offer, a stock consolidation, and the purchase of remaining shares held by Japan Tobacco. Shionogi positioned the move as a way to strengthen its standing in the industry by making use of Torii’s specialized knowledge in dermatology and related therapeutic areas.

The Ping An Joint Venture: A Learning Experience

Shionogi also tried a different kind of expansion play in China. Ping An-Shionogi Co., Ltd.—a joint venture between Ping An and Shionogi—launched in Shanghai as a “Healthcare as a Service” platform, aiming to combine Ping An’s healthcare ecosystem and digital technology with Shionogi’s drug R&D strengths across research, development, production, and sales.

But the partnership didn’t reach its full ambitions. The companies agreed to amicably dissolve the joint venture business, while Shionogi said it would continue working to contribute to patients and healthcare in China and Asia. As part of the unwind, Shionogi Hong Kong would acquire the 49% stake held by Ping An Life in Ping An-Shionogi Co., Ltd.

Even so, Shionogi noted real progress came out of the collaboration. The joint ventures advanced certain Shionogi-originated drugs. And on the AI-for-drug-discovery goal in China, Shionogi said the collaboration produced significant results: by combining Ping An’s AI technology with Shionogi’s drug discovery expertise, multiple development candidates were generated.

Digital Therapeutics

Finally, Shionogi has been pushing beyond pills entirely. The company announced it submitted a marketing approval application in Japan for SDT-001, a prescription digital therapeutic app for pediatric patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). SDT-001 was developed by Akili and is the Japan-localized version of Akili’s AKL-T01—marketed as EndeavorRx in the United States—which has already been authorized by the U.S. FDA as the world’s first prescription digital therapeutic for improving attentional functioning in pediatric ADHD patients aged 8 to 17.

The app—referred to as ENDEAVORRIDE—is designed to engage children through smartphones and tablets and is expected to improve symptoms by activating the brain’s prefrontal cortex. It’s built on Akili’s Selective Stimulus Management Engine core technology, using optimized dual-task activities tailored to each patient.

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Shionogi’s 147-year journey isn’t just a history lesson. It’s a set of repeatable moves—choices the company made again and again—that explain how an Osaka-based drugmaker kept finding ways to matter in a brutally cyclical industry.

The Out-Licensing Model

Shionogi built a disciplined pattern: do the hard part in-house—discover the molecule, develop it far enough to prove it works—then hand commercialization to a global giant built to launch at scale. It’s not a compromise. It’s a strategy rooted in self-awareness. Shionogi consistently played to its strength—drug discovery—while avoiding the cash burn and organizational complexity of building a massive worldwide sales force.

The upside is straightforward: capital efficiency, lower downside risk, and relentless focus on the discovery engine. The downside is just as real: you give up a lot of the economic jackpot. If Shionogi had kept worldwide rights to Crestor, the revenue could have been far larger—but so would the investment, the operational risk, and the potential for a costly global stumble.

For long-term investors, this model only works if the pipeline keeps coming. Shionogi managed that for decades—moving from antibiotics, to a statin blockbuster, to the HIV integrase franchise, to an oral COVID antiviral. But the moment the discovery engine slows, the whole machine starts to look fragile.

Navigating Patent Cliffs

Shionogi’s handling of the Crestor Cliff is a reminder that surviving patent expirations isn’t just about replacing revenue—it’s about managing psychology inside the company. After Crestor’s peak, the combination of renegotiated royalty terms and strong earnings helped Shionogi land the transition. But the company later acknowledged an uncomfortable truth: success bred confidence, and confidence sometimes dulled urgency.

The modified royalty agreements didn’t strengthen the underlying business on their own—they largely shifted the royalty center of gravity from Crestor to the dolutegravir-based HIV franchise. That shift was powerful, and it worked. But it also created a temptation to believe the problem was solved because the numbers looked good.

The lesson is simple: dealmaking can soften a cliff, and a new franchise can replace it—but neither can substitute for rebuilding the next wave of innovation. Shionogi’s updated plans reflected that reality, channeling resources into areas where it had real edge, with the goal of sustainable growth as a drug-discovery company, not a royalty-harvesting one.

The Infectious Disease Focus

If you want the most contrarian part of Shionogi’s strategy, it’s this: it kept showing up in infectious disease even as much of Big Pharma walked away—especially from antibiotics.

The economics are famously punishing. Antibiotics are expensive to develop, but once launched they’re often used sparingly because stewardship demands it. Lower usage means lower revenue, which makes it harder to justify continued commercialization, which then discourages new R&D. It’s a vicious loop—and it’s why many large pharmaceutical companies have exited the category.

Shionogi’s answer has been to keep building anyway, while pushing for policy change: post-market incentives, and value assessment frameworks that reflect what a new antibiotic is actually worth to society.

Cefiderocol is one example of how that commitment shows up in the real world. It is currently marketed in 25 countries and regions, including Japan, Europe, the United States, and Taiwan, and is described as the first and only siderophore cephalosporin antibiotic for the treatment of serious Gram-negative infections.

The bet Shionogi is making is that health systems will eventually be forced to price antibiotics like the strategic assets they are. If that happens, Shionogi wants to be one of the few companies still standing with the capabilities—and the pipeline—to capture the upside.

Japanese Pharma Culture

Shionogi’s family lineage—founder Gisaburo Shiono, and descendants leading the company into the 1990s—created something rare in pharma: institutional patience. When leaders can think in decades rather than quarters, different choices become possible. You can stick with tough categories. You can reinvest royalty windfalls instead of treating them as permanent. You can play a longer game.

That cultural advantage matters even more when you compare it to the pressures many Western pharmaceutical companies face: activist investors, quarterly expectations, and constant demands for immediate returns. Shionogi’s Japanese roots didn’t eliminate those realities, but they did provide insulation—and that insulation helped it keep making the kinds of long-horizon bets that defined its history.

X. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Strategic Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low where Shionogi is deepest. Drug discovery demands huge R&D spend, regulatory muscle, and—most importantly—time. You can’t fast-follow your way into decades of infectious disease know-how, and Shionogi has been building that muscle for more than 70 years.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Pharmaceutical ingredients and manufacturing are specialized, and that can give suppliers leverage. But Shionogi has been nudging toward more control, and the Torii acquisition adds integration in areas that matter.

Buyer Power: High, and getting higher. Governments and large payers are increasingly aggressive on pricing, and antibiotics are especially squeezed. Even when the medical value is obvious, the reimbursement reality can be brutal—and that’s a real structural headwind for Shionogi’s infectious-disease-heavy mix.

Threat of Substitutes: It depends. In HIV, entirely new approaches—like gene therapies—could eventually change the landscape. In antibiotics, substitution is less about “a better alternative” and more about “the old one stopped working.” When resistance rises, the substitute for today’s standard of care is often the next novel antibiotic.

Competitive Rivalry: Mixed. In infectious disease, rivalry is muted simply because so many big players left. In broader pharma, the fight is constant. Shionogi’s most relevant matchups are indirect but real: Gilead on HIV (through ViiV’s competition) and Pfizer in COVID antivirals.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate. Scale helps in trials, regulatory operations, and global launches—areas where Shionogi historically leaned on partners. The company’s edge has been figuring out where it needs scale and where it can borrow it.

Network Effects: Limited in classic pharma. But Shionogi’s stake in ViiV creates a loose analogue: ViiV’s success strengthens its ecosystem, which in turn makes it a more attractive home for future HIV innovations that Shionogi helps originate.

Counter-positioning: Strong. Shionogi’s commitment to infectious disease—especially “unfashionable” small molecules—looks like textbook counter-positioning. The larger companies that walked away can’t easily come back without admitting they were wrong and absorbing economics their investors may not tolerate. Teshirogi has essentially said as much: chasing cheaper therapies “wouldn’t be popular with investors” at many Big Pharma companies.

Switching Costs: High in practice. Once hospitals and physicians get comfortable with a drug’s profile—especially antibiotics, where resistance patterns and institutional protocols matter—switching isn’t frictionless.

Branding: Moderate. Shionogi isn’t a household name, but within infectious disease circles, credibility is its brand—and credibility travels.

Cornered Resource: Real. Shionogi’s decades of infectious disease data, compound libraries, and accumulated expertise form an asset that isn’t easily bought or copied.

Process Power: Possible, but hard to prove from the outside. The consistency with which Shionogi has generated licensable molecules suggests there’s something repeatable in how it discovers and advances drugs—even if we can’t fully see the machinery.

Bull Case

The bull case is essentially: Shionogi’s next act works, and the old acts keep paying.

-

Ensitrelvir FDA approval would open a meaningful new revenue stream if the post-exposure prophylaxis indication is approved on the FDA’s June 2026 action date. And if that happens, Shionogi argues it would be the first and only oral therapy for preventing COVID-19 after exposure.

-

HIV franchise durability: Dolutegravir is now taken by 17 million people globally, and Shionogi’s third-generation integrase inhibitor collaboration is designed to extend that value well beyond the current lifecycle.

-

Antibiotic opportunity: Antimicrobial resistance is projected to become catastrophic—up to 10 million deaths per year worldwide by 2050. If reimbursement and incentive programs catch up to the societal value of new antibiotics, Shionogi is positioned to benefit as one of the few companies still investing.

-

Torii acquisition synergies: More domestic reach and added capabilities in dermatology help diversify the business and reduce reliance on a small number of royalty streams.

-

Financial strength: The company’s annual dividend has now increased for 13 consecutive years—an indicator of confidence, discipline, and cash-generation capacity.

Bear Case

The bear case is the mirror image: concentration risk plus the reality that pharma clocks always run out.

-

HIV patent cliff exposure: A key HIV drug and three combination medicines are expected to face generic competition in nine years. That’s a real earnings hole, and replacing it fully is hard—even with a strong pipeline.

-

COVID-19 antiviral market saturation: Paxlovid is entrenched, and as COVID becomes endemic, demand may not support another blockbuster-scale entrant—even with a differentiated prevention positioning.

-

Antibiotic economics: The need is enormous, but the business model is still fragile. Stewardship limits volume, and pricing power is often constrained, even when the drug is lifesaving.

-

Geographic concentration: Heavy dependence on Japan, plus significant exposure to HIV-related royalties, leaves Shionogi vulnerable to policy changes, competitive shocks, or partner dynamics.

-

R&D productivity concerns: Not every bet pays off. The shelved anti-obesity candidate is a reminder that even disciplined discovery organizations miss—and if miss-rate rises, the whole out-licensing-and-royalty machine has less to run on.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to judge where Shionogi goes from here, you don’t need a hundred metrics. You need a few that tell you whether the company’s core engines are still firing—and whether the next one is actually coming online.

-

Royalty and Dividend Income from ViiV Healthcare: This is the pulse check on Shionogi’s most important partnership. In the three months ended March 31, 2025, payments from ViiV Healthcare to Shionogi totaled £331 million. Watch the trend quarter to quarter, and watch ViiV’s grip on the HIV market—because this stream is what makes Shionogi’s unusually royalty-heavy model work.

-

Xocova/Ensitrelvir Sales and Regulatory Progress: This is the clearest read on Shionogi’s ability to build a meaningful, self-commercialized product outside the traditional out-licensing playbook. Track the regulatory milestones—especially the FDA’s action date in June 2026—along with pricing in markets where it’s approved and real-world utilization. If ensitrelvir scales globally, it becomes Shionogi’s next owned growth driver.

-

Overseas Business Revenue Growth: Shionogi’s overseas business has hit a record high for four consecutive terms, driven by stable growth of cefiderocol. The thing to watch here isn’t just the product—it’s the capability. Track cefiderocol’s expansion across markets like China, Australia, Taiwan, and Korea as a proxy for whether Shionogi can consistently commercialize globally, beyond Japan, without relying entirely on a partner to do the heavy lifting.

XII. Conclusion: What This Company's Story Reveals

Shionogi’s 147-year run—from a storefront in Osaka’s medicine district to a behind-the-scenes force in global HIV care—reads like a case study in doing the hard part, then letting someone else do the loud part. Time and again, it discovered high-value molecules and chose partnership over empire-building. It turned patent cliffs into managed descents through negotiation and timing. And it kept placing bets on infectious disease even when the rest of the industry decided the category wasn’t worth the trouble.

Under President and CEO Isao Teshirogi, Shionogi has leaned into a simple idea: stay a drug-discovery company first. The philosophy the company points to—trustworthiness, contribution to society, and delivering medicines essential to health—sounds lofty, but in Shionogi’s case it maps directly to its operating choices. It explains why royalties matter so much. It explains why the company keeps showing up in antibiotics and antivirals. And it explains why, when it wants global reach, it so often prefers to build alliances rather than build an empire.

The strategic question for the next decade is whether Shionogi can pull off another transition—this time, from heavy dependence on HIV royalties to a more diversified global business—without losing the focus that made it great. The Torii acquisition, ensitrelvir’s expansion path outside Japan, and the third-generation HIV program with ViiV are all moves in that direction. Together, they’re a bid for something Shionogi historically avoided: more control over its own destiny.

Financially, Shionogi reported a slight increase in revenue and profit for fiscal year 2024, and it forecast significant growth for fiscal year 2026—signals that management believes the next phase has real momentum. Whether that momentum holds will depend on execution: regulatory outcomes, commercialization capability, and the ability to keep the discovery engine productive.

For investors, the bet is basically twofold. First: that infectious disease expertise will only get more valuable in a world defined by pandemic risk and antimicrobial resistance. Second: that a research-driven, mid-sized company can keep competing by being indispensable to larger partners—without needing to become one of them.

And zooming all the way back out, that might be the most enduring part of the Shionogi story. Since 1878, it has tried to harness science to tackle difficult diseases—and to translate that science into medicines people actually use. The products have changed completely, from early stomach remedies to modern antivirals and precision HIV regimens. But nearly 150 years after Gisaburo Shiono opened his shop in Doshomachi, the core promise has stayed remarkably consistent: supply the best possible medicines to protect patients’ health.

In an industry that’s often accused of drifting away from patients as the incentives get bigger and the science gets flashier, that kind of continuity—paired with real innovation—may be Shionogi’s most distinctive asset of all.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music