Kao Corporation: Japan's Consumer Goods Innovator and the Quest for "Kirei"

I. Introduction: The Procter & Gamble of Japan

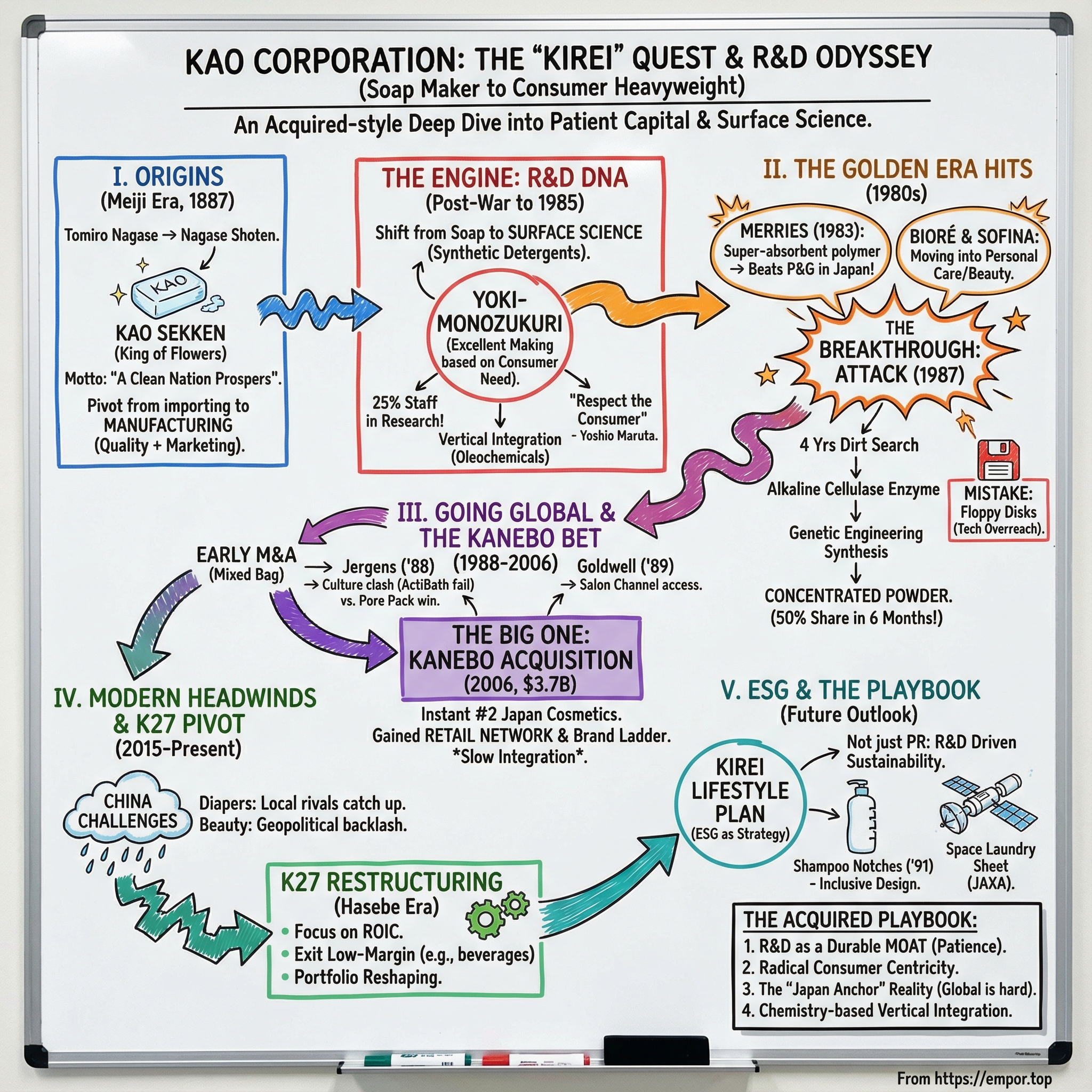

Picture Japan in the late 1980s. Inside Kao’s research labs, a team of scientists was wrapping up an R&D odyssey that didn’t start with chemistry at all. It started with dirt.

For four years, Kao researchers gathered grime samples from around the world—real-world stains from real homes—searching for a microorganism that could do something detergent couldn’t: break down the kind of stubborn residue that clings to cotton fibers. They found their target: a bacterium that produces alkaline cellulase, an enzyme that works in the high-pH environment of laundry. Then came the hard part. Kao spent the next two years using genetic engineering to synthesize that enzyme reliably and at scale.

Out of that six-year effort came Attack, a product that didn’t just clean better—it changed the category. Attack was a concentrated laundry detergent, delivering the same or better performance with a fraction of the volume of conventional detergents. It was lighter to carry home, took up less space on the shelf, and came with an environmental edge at a time when that wasn’t yet standard consumer language. And consumers responded fast: within six months of launch, Attack captured nearly half of Japan’s detergent market—despite being priced higher than many alternatives.

That’s Kao in one product story: patient, science-first, and relentlessly practical about what the customer actually experiences.

Often called the Procter & Gamble of Japan, Kao is a leader in personal care, cosmetics, laundry and cleaning, hygiene products, and more. Its brand roster—Attack, Bioré, Goldwell, Jergens, John Frieda, Kanebo, Laurier, Merries, Molton Brown, and others—puts it in bathrooms and kitchens across Asia, Oceania, North America, and Europe. Alongside its chemical business, Kao generates roughly 1.5 trillion yen in annual sales.

But here’s the deeper point behind Attack: Kao is unusually willing to invest in foundational research that many consumer goods companies would label too slow, too expensive, or too uncertain. The company’s edge isn’t just marketing or distribution. It’s the conviction that if you understand the problem deeply enough—down to biology and surface chemistry—you can build products people will switch for, pay more for, and stick with.

So that’s our roadmap. We’re going to follow how a Meiji-era soap maker became an R&D powerhouse that pioneered concentrated detergents, beat P&G in diapers on its home turf, and then made one of Japan’s biggest cosmetics bets with the Kanebo acquisition. We’ll cover the founding philosophy that still shapes the culture, the innovation engine that kept creating hit products, the messy first attempts at globalization, the modern headwinds—especially in China—and what all of it means for a 138-year-old company trying to stay essential in a very different world.

II. Founding Origins: A Clean Nation Prospers (1887–1945)

To understand Kao, you have to start with the Japan of 1887: a country in the middle of the Meiji Restoration, modernizing fast and importing anything that looked like “the West.” Soap was one of those quiet status symbols. Imported soap was high-quality and aspirational. Domestic soap, when you could find it, often wasn’t very good. And for most households, the imported stuff was simply too expensive.

Tomiro Nagase saw the gap. He opened Nagase Shoten in Tokyo as a dealer in Western sundry goods—soap, cosmetics, household items—serving the growing appetite for modern consumer products. But selling imports also taught him the ceiling on the business: if the best products were priced out of reach, the market would stay limited. So he made a pivot that would end up defining Kao’s entire identity. He moved from importing to making—producing high-quality soap in Japan using imported vegetable oils, including palm and coconut, so he could bring quality within reach.

Nagase wasn’t just trading goods; he was building capabilities. He hired talent, set up a lab, and pushed into the technical foundations of what made great soap: chemistry, color, fragrance. Long before “R&D-driven consumer company” was a phrase anyone used, Nagase was acting like that’s exactly what he was building.

In 1890, the company launched its first soap. Nagase named it Kao Sekken to signal quality and identity at the same time. “Kao” sounds like “face” in Japanese, and the kanji used for “Kao” literally mean “king of flowers.” The product shipped with a motto that was more than a tagline—it was a worldview: “A Clean Nation Prospers.” In Meiji-era Japan, where modernization was a national project, connecting personal hygiene to national progress landed.

That same year, Kao adopted a crescent-moon logo—strikingly similar to Procter & Gamble’s, which had been registered eight years earlier. Coincidence or not, it’s a fun bit of foreshadowing: two soap companies, two crescents, and a rivalry that would echo through the next century.

Nagase also understood something many technically minded founders learn the hard way: quality doesn’t matter if nobody knows it exists. His marketing was unusually aggressive for late-19th century Japan. He ran newspaper ads frequently, put a famous geisha on posters, and even placed billboards along railway tracks—rare at the time. And he built distribution that reached nationwide, something that was almost unheard of in Japan’s consumer markets then.

The formula was set early: make something meaningfully better, then tell the story loudly and get it everywhere. That mix—technical seriousness paired with practical, consumer-facing execution—became a recurring pattern in Kao’s later breakthroughs.

And Nagase left behind a simple cultural anchor. In his will, he wrote: “Good fortune is given only to those who work diligently and behave with integrity.” It’s the kind of line companies love to quote. But at Kao, it also reads like an operating principle—one that would survive leadership changes, new categories, global expansion attempts, and the pressure to chase growth at any cost.

Those early choices—investing in science, committing to reach everyday consumers, and grounding the company in an integrity-first ethic—aren’t just origin-story color. They explain why Kao repeatedly played the long game later, and why its best moments tend to come when it combines deep technical work with a very human question: what would make this better in someone’s daily life?

III. The R&D DNA: From Soap to Surface Science (1945–1985)

World War II left much of Japan’s industrial base in ruins, and Kao—like everyone else—had to rebuild. But the reset did something important: it pushed Kao from being “a soap company” toward becoming something much harder to copy—a surface science company, with know-how that could travel across categories.

In one sense, that shift had already begun earlier. By the end of the 1920s, Kao had developed coconut alcohol-based synthetic detergents. After the war, it moved into heavy-duty detergents. That transition mattered because it changed the nature of what Kao was learning. Soap is about processing natural fats and oils well. Synthetic detergents are about designing molecules on purpose—tuning how they interact with water, oil, fabric, skin, and dirt. Kao was building a capability, not just a product line.

And Kao didn’t dabble in that capability. It committed to it at a scale that’s almost hard to believe: about a quarter of its employees were involved in research, especially in surface technology. That focus started with oils and fats—the building blocks of soap—and then radiated outward. Once you understand how substances spread, cling, repel, dissolve, and stabilize, you can do far more than make bars of soap. Kao’s research base opened the door to finishing products, polishing agents, waxes, insecticides, antiseptics, fungicides, and deodorants.

One in four employees dedicated to research isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s a business model. While competitors might treat R&D as overhead to manage, Kao treated it as the engine. That’s a big part of why, later on, the company could repeatedly launch products that didn’t just compete—they redefined what consumers expected.

In 1976, Kao made the strategy explicit by establishing its Research and Development Division. This wasn’t just an org-chart change. It was Kao saying, in a formal way, that innovation was the foundation of the company. Inside the labs, product development wasn’t siloed; the R&D meetings brought together the people who had to turn science into something you could ship. One large floor of the laboratory served as a shared venue for intense, cross-disciplinary discussion—the kind of setup that made it easier for unexpected connections to turn into new products, and sometimes entirely new businesses.

This R&D machine also had a philosophy attached to it: Yoki-Monozukuri. It means deeply understanding what consumers and customers value, then delivering products, brands, technologies, and solutions that genuinely satisfy them. It’s “monozukuri,” craftsmanship and making, but anchored in “yoki”—good, excellent. The idea is simple but demanding: innovation doesn’t start with what you can make. It starts with what people actually need, and then you earn the right to exist by delivering on it.

As Kao’s technical confidence grew through the 1960s and 1970s, it expanded geographically into Taiwan and ASEAN countries. It also expanded industrially, moving into oleochemicals to complement its main consumer business. That move upstream mattered. By producing more of the chemical building blocks that went into its formulations, Kao gained a level of vertical integration that most consumer goods companies never touch. That brought cost advantages, yes—but more importantly, it deepened Kao’s understanding of its raw materials, which fed back into product performance.

This era also produced the kind of everyday hits that quietly build a household-goods empire: New Beads detergent, Humming fabric softener, Haiter bleach, and Magiclean household cleaners. Different items on the shelf, but all powered by the same underlying competency: how to get substances to behave on surfaces.

Then, in 1971, Kao got a president who embodied this science-first worldview—along with the intensity that often comes with it. Yoshio Maruta became president and pushed the R&D culture even harder. He held a doctorate in chemical engineering, had 16 patents, and during World War II invented a process for producing aircraft lubricant from vegetable oil when petroleum supplies were scarce. He was aggressive and charismatic—and often criticized for a domineering style that didn’t leave much room for open debate.

But Maruta had one principle that cut through everything: respect the consumer. As one of his assistants told Forbes, “You can cheat housewives once, but not twice.”

That line is blunt, even harsh. But it captures the reality of consumer goods. You can buy trial with advertising, but you only earn repeat purchase with performance. Under Maruta, that idea—quality enforced by a deep fear of disappointing the customer—hardened into culture.

By the time Kao reached the mid-1980s, the pieces were in place: a quarter of the workforce tied to research, deep expertise in surface chemistry, upstream chemical capabilities, and a philosophy that started with real consumer needs. That combination would soon produce the kind of breakthroughs—like Attack—that make a company feel inevitable in hindsight.

IV. The 1980s Golden Era: Attack, Merries, and Bioré

If the postwar decades built Kao’s innovation engine, the 1980s were when it started firing on all cylinders. One after another, Kao shipped products that didn’t just sell well—they reset what “good” looked like in entire categories, and locked in leadership positions the company would defend for years.

The run started in personal care and hygiene, where Kao steadily widened from “cleaning the home” to “caring for the body.” Laurier sanitary napkins arrived in 1978. Bioré facial cleanser followed in 1980. Kao stepped into beauty with Sofina cosmetics in 1982, then added Bub carbonated bath additive and Merries disposable diapers in 1983, Bioré U body wash in 1984, and finally the knockout punch: Attack concentrated detergent in 1987.

Sofina is worth pausing on. In 1982, Kao entered the cosmetics market for the first time, and it didn’t tiptoe in. With Sofina, it rapidly rose to the number two position in Japan’s cosmetics market, behind only Shiseido. For a company best known for detergents and household staples, cracking prestige cosmetics that quickly was a signal to the market: Kao’s R&D discipline traveled.

But 1983 delivered the kind of win that makes competitors furious. Merries, Kao’s disposable diaper, outsold Procter & Gamble’s in Japan. P&G had essentially created the modern disposable diaper category and had the budget to outspend almost anyone. Kao won anyway, because it built a product Japanese parents felt was better—especially on what mattered most: babies’ skin. Merries earned its reputation as unusually gentle, thanks to Kao’s development of a highly absorbent polymer that helped reduce diaper rash.

This was the deeper pattern of Kao’s decade. Surface science wasn’t an abstract capability sitting in a lab. It was a practical advantage that showed up anywhere materials met real life—fabric, skin, hair. That’s the moat: not one hero product, but a set of underlying competencies that could keep generating new heroes.

And then, in 1987, Attack arrived and became the decade’s signature story. The backstory reads like a research thriller because it basically was one. Kao spent four years collecting dirt samples from around the world to find a bacterium that produces alkaline cellulase—an enzyme that could break down grime in a way traditional detergents couldn’t. Then it took two more years to synthesize that enzyme through genetic engineering. The payoff was a detergent that was dramatically more concentrated than what consumers were used to.

The market reacted immediately. Within six months, Attack grabbed almost half of Japan’s detergent market. It was priced higher than many alternatives, but people didn’t care—because they could feel the difference. The bottle was smaller and lighter. It fit in cramped Japanese homes. And it delivered performance that made switching worth it.

That concentration had another advantage that Kao understood early: it quietly made the whole system more efficient. Less product meant less packaging and less energy in production and distribution. Sustainability wasn’t the dominant consumer narrative yet, but Attack’s design baked those benefits in from day one—an early example of how “better for the customer” and “better for the environment” could be the same decision.

Attack went on to remain a central brand in Japanese laundry care, with market share over time moving within a wide band—but staying firmly in the leadership conversation for decades after launch.

Not everything in the 1980s was as clean a win. By this point, Kao had expanded far beyond soap and even changed its name to Kao Corporation in 1985. And in the same era, Kao’s surface-technology research tugged the company into a strange direction: electronics. A research project on face powders led to a discovery about dispersing magnetic particles—useful not for skin, but for floppy disks. Kao set up a U.S. subsidiary in 1985, Kao Infosystems Company, to manufacture them.

In hindsight, the floppy disk diversion became a costly misstep. But it’s also revealing. It shows both the reach of Kao’s science—and the temptation to follow that science too far away from the consumer-product problems Kao was best at solving.

From an investor’s perspective, the 1980s are the template for understanding Kao at its best and at its most vulnerable. At its best: deep R&D translated into products people would pay up for, across multiple categories. At its most vulnerable: the same confidence in core technology could justify adjacencies that looked logical in the lab, but didn’t fit the business.

V. The First Global Push: Mixed Results (1988–2005)

By the late 1980s, Kao had proven it could out-innovate almost anyone inside Japan. The problem was that the battlefield was getting bigger—and the giants were showing up at Kao’s doorstep.

Procter & Gamble and Unilever were pushing into Japan with deeper pockets and global playbooks. And the gap in resources was real: in the mid-1990s, P&G was spending about four times what Kao spent on R&D. In fast-growing Asian markets, P&G moved quickly—capturing about half the shampoo market in China and Taiwan—while Kao’s share in those countries tended to sit in the low double digits.

So Kao made a logical decision: if the multinationals were coming to Japan, Kao would go to them.

The company’s first serious global push came through acquisitions. In 1988, Kao bought the Andrew Jergens Company in Cincinnati, giving it an on-the-ground platform in the United States. A year earlier, Kao had acquired High Point Chemical Corporation, a specialty chemicals business in North Carolina that supplied raw materials for Jergens’ toiletry and skin-care products—an early attempt at building a vertically connected foothold. Then in 1989, Kao bought a 75% stake in Germany’s Goldwell, a hair-care and beauty business sold through professional hairdressers around the world.

On paper, this was smart. Jergens opened the world’s largest consumer market. Goldwell opened a completely different distribution engine: the professional salon channel, with its own dynamics and loyalty loops.

And for a moment, it looked like the plan was working. Those deals pushed the share of Kao’s revenue coming from outside Japan up to around 20% by the mid-1990s.

But growing revenue outside Japan is not the same thing as building a durable global machine. Kao struggled to build on what it had bought.

One issue was deceptively simple: consumer habits. In 1989, Jergens tried to bring a hit Kao product concept from Japan to the U.S. market—bath tablets called ActiBath. It didn’t land. Americans, broadly speaking, take fewer baths than Japanese consumers and treat bathing differently. ActiBath wasn’t a “bad product.” It just solved a problem many Americans didn’t have, in a ritual they didn’t prioritize. Kao was learning an uncomfortable lesson: world-class R&D can’t substitute for cultural fit.

And even when the product concept was right, the competitive environment was brutal. In the U.S., Kao was going up against P&G and Unilever on their home turf—companies that already owned distribution relationships, shelf space, and mindshare.

Meanwhile, the company was still dealing with the other big bet from the previous era: floppy disks. With acquisitions including West Coast Telecom in Portland and Sentinel Technologies in Massachusetts, plus a new $60 million plant in Plymouth, Massachusetts, Kao Infosystems became, in 1990, the largest North American maker of 3.5-inch floppy disks—while also staying consistently unprofitable. It later branched into CD-ROMs, hard disks, and digital audiotapes, but the losses continued. By 1996 it was still losing money, and the business would eventually be restructured and largely exited.

If ActiBath was a story about cultural misunderstanding, floppy disks were a story about strategic overreach—following a piece of technical insight into an industry where Kao didn’t have the advantage.

Still, Kao didn’t strike out everywhere. In April 1996, it launched the Bioré Pore Pack in Japan. The product was simple and highly visual—a facial strip that pulled out blemishes—and it took off, reaching ¥10 billion in sales in its first year. When it came to the U.S. in the summer of 1997 through Jergens, it quickly became the top product in its category, with $55 million in sales in just the first nine months.

The difference mattered. Pore strips weren’t tied to a uniquely Japanese daily ritual. They delivered immediate, obvious results. You didn’t need a cultural translation layer to understand why they worked.

Outside the West, Kao’s expansion story was generally stronger. In the early 1990s, it was competing alongside P&G and Unilever across Hong Kong, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand. As China and Vietnam opened up, Kao leaned in. Revenue from the region grew at about a 15% annual pace from the early to mid-1990s. Cultural proximity helped: Japanese product quality carried prestige, and grooming and bathing habits were closer to Japan’s than what Kao faced in the U.S.

By the early 2000s, Kao’s global strategy started to tilt again—toward premium, where it could avoid some of the brute-force mass-market spending wars. The acquisitions of John Frieda Professional Hair Care in 2002 and Molton Brown in 2005 fit that shift. In July 2005, Kao bought Molton Brown, a U.K. luxury bath, skin-care, and cosmetics brand, for £170 million ($298 million).

Put it all together and this first global era reads like a company running experiments at scale. Kao learned the hard way that Japan-developed product concepts don’t automatically travel, that diversifying outside consumer goods can get expensive fast, and that competing head-on with the biggest multinationals in mainstream Western categories is a punishing game. But it also found the lanes where it could win: culturally adjacent Asian markets, and premium Western brands where differentiation mattered more than sheer spend.

Those lessons set the stage for what came next—Kao’s biggest bet yet in beauty, and the acquisition that would reshape the company’s trajectory.

VI. The Kanebo Acquisition: Transformative Bet (2006)

In early 2006, Kao placed the biggest bet in its history—and did it in the one arena where it had proven it could play, but hadn’t yet won at scale: cosmetics.

Kao acquired Kanebo Cosmetics Inc. for ¥427 billion (about $3.7 billion). Kanebo Cosmetics was the beauty arm of Kanebo, Ltd., which had become financially troubled. Kao and Kanebo had been in advanced talks two years earlier, but that deal collapsed in early 2004. This time, it went through. Overnight, Kao moved into the top tier of Japanese beauty, becoming the country’s second-largest cosmetics maker behind Shiseido.

The reason this deal matters isn’t just the size. It’s the situation. The bidding process was overseen by The Industrial Revitalisation Corporation (IRC), the government-backed turnaround body that had stepped in after Kanebo went into receivership following an accounting scandal that surfaced two years earlier. That kind of forced sale created a window you almost never see with an asset this valuable: a major cosmetics platform, available at a moment when its parent couldn’t protect it.

And plenty of global players were watching. L’Oréal ultimately dropped out, saying Kanebo didn’t offer enough synergies. Kao didn’t need “synergies” in the abstract. It needed the missing pieces of a beauty empire.

Those pieces were substantial. The acquisition was expected to quadruple Kao’s cosmetics sales to ¥288 billion. But the more strategic prize was reach: Kanebo Cosmetics brought annual revenues of roughly ¥212 billion (about $1.8 billion), operations in around 50 countries, and an extensive retail network.

That retail network was the real unlock. Cosmetics aren’t just made; they’re sold through specialized channels, often with beauty consultants who guide customers and build loyalty. Kanebo had a full sales infrastructure—11 cosmetics sales subsidiaries in Japan and 14 overseas. Kao, by comparison, had only one in Japan and was far more oriented toward drugstore cosmetics. Kanebo also spanned everything from affordable products to luxury, giving Kao a broader ladder than it had built on its own.

Kao’s integration approach reflected that reality. Instead of forcing a quick merger, it kept Kanebo Cosmetics operating independently as a wholly owned subsidiary. The goal was to protect brand identity and retail relationships first, and integrate operations carefully over time.

That “over time” part turned out to be very literal. As Kao pushed forward, it unified its cosmetics operations step by step across five units. A horizontally organized structure linking the brands in operational planning was completed in January 2019. Travel retail operations and beauty research and creation were linked a year later, in January 2020. Then, effective January 2021, Kao completed a strategic shift away from brand management built around individual business units—Sofina, Curél, Kanebo Cosmetics, and others—toward three business groups: Prestige Business, Masstige Business, and Regional Business.

The pace tells you something important about beauty: you can’t integrate it like detergent. In prestige cosmetics, brand equity and the customer relationship are the product. Move too fast, and you don’t create value—you destroy it.

Kao also clarified where it wanted to place its bets. In May 2018, it created a “New Global Portfolio” for cosmetics, selecting eleven strategic brands (G11) to strengthen globally and eight brands (R8) to expand in Japan, drawn from its five major cosmetics units: Sofina, Curél, Molton Brown, Kanebo Cosmetics, and e’quipe.

With Kanebo in the fold, Kao also aimed at what looked like the next great growth engine: China’s booming cosmetics market. Kao planned to add cosmetics to its lineup in China by the middle of the following year. President Takuya Goto framed the logic bluntly: after a decade of trying—and failing to truly break through with detergent, shampoo, and soap—Kao would change tactics and lead with beauty.

That China push would later run into headwinds. But judged on its core intent, Kanebo did what Kao needed it to do: it transformed the company from a promising cosmetics challenger into a real competitor to Shiseido, with a broader portfolio, a global footprint, and the kind of retail muscle beauty requires.

And it offered a final lesson that would keep showing up in Kao’s story: the acquisition headline is the beginning. The real work is the decade-plus that follows.

VII. The Modern Challenges: China Headwinds & K27 Restructuring (2015–Today)

After 2015, Kao ran into the part of globalization that doesn’t show up in the acquisition deck. The company had spent years treating China as the obvious growth engine—the market big enough to move the needle, close enough culturally to play to Japan’s strengths, and fast enough to justify long-term investment. Then the ground shifted under it.

The clearest example showed up in diapers. In its earnings updates, Kao said sales of Merries in China fell as the market shrank and competition intensified. The bigger change was who was winning. Local brands steadily took share, rising from a minority position in the late 2010s to the majority by the early 2020s. Younger parents increasingly preferred domestic labels such as Beaba and Babycare—brands that weren’t just cheaper, but were able to position themselves as premium, too.

Kao had entered China diapers in 2009 and began local production in 2012, and at first it worked. Merries built a reputation for breathability and softness. But once local players matched those attributes, Kao’s differentiation thinned out. Eventually, Kao stopped producing disposable baby diapers in Hefei, Anhui—an unmistakable sign that what had looked like a long runway had turned into a brutal fight for diminishing returns.

Beauty got hit from a different direction, and in some ways a more unsettling one: geopolitics. As China’s economy slowed, business sentiment weakened. Then came the consumer backlash tied to Japan’s discharge into the ocean of treated water from Fukushima Daiichi—water processed using the Advanced Liquid Processing System, or ALPS. Kao reported that cosmetics sales in China fell sharply, citing key opinion leaders voluntarily refraining from activities, constraints on promotional activity, and other knock-on effects from the local reaction.

This is the kind of risk you can’t out-innovate. When consumer demand gets tangled up with national origin, a product can be excellent and still lose.

By 2023, the message was clear: China couldn’t be the single pillar holding up Kao’s international ambitions. In August of that year, Kao revised its Mid-term Plan 2027—K27—framing it around structural reform and growth strategies, while keeping its stated vision of “Sustainability as the only path.” The operational change beneath the slogan was more concrete: Kao began introducing ROIC as a company-wide discipline and committed to “decisively” reshaping the portfolio.

K27 marked a pivot away from growth-at-all-costs and toward capital efficiency and core strength. To improve ROIC, Kao transferred underperforming businesses, including pet care and beverages, and ended local diaper production in China.

The company put it plainly in its announcement about transferring the Healthya beverage brand:

"Kao is accelerating structural reforms to strengthen the competitiveness of our core businesses to achieve the goals of our Mid-term Plan 2027 (K27). As part of the efforts to review and optimise our business portfolio, we have decided to transfer the Healthya brand. We have selected Kirin Group, a leading beverage manufacturer excelling in immunology research, as the best partner to further develop the brand."

Financially, Kao started to show signs that the cleanup was working. In fiscal 2024, net sales rose to 1,628.4 billion yen, up 6.3% year-on-year. Part of that lift came from currency translation, but the company also reported like-for-like growth.

Kao positioned 2023 as the heavy-lifting year—major structural reforms—and 2024 as evidence those reforms were translating into “solid results.” The plan, as Kao described it, was to keep strengthening earning power in fiscal 2025 by enhancing and accelerating Yoki-Monozukuri, but now through the lens of ROIC: build products people truly want, and do it in a way that consistently earns an attractive return on the capital required.

The company’s outlook for fiscal 2025 reflected that same framing: modest net sales growth paired with stronger improvement in operating income and incremental ROIC expansion.

The organizational changes followed. Effective January 2025, Kao rolled out a global restructuring aimed at accelerating K27, including unifying business and sales into a Global Consumer Care Business and clarifying regional responsibilities.

This shift has been closely associated with CEO Yoshihiro Hasebe, who became President and CEO in January 2021. Kao described his agenda as pushing beyond conventional business models—using digital technologies, improving employee engagement, and raising operational productivity—in service of the company’s “Protecting Future Lives” ambition. He also played a central role in shaping and launching K27 in 2023, including the structural reforms intended to build what Kao calls “Global Sharp Top” businesses. Before becoming CEO, Hasebe served in roles including President of Research and Development and Senior Vice President of Strategic Innovative Technology, after joining the company in April 1990.

For investors, the takeaway from this era is sobering but useful. Geographic concentration risk can show up fast, and from directions you can’t model cleanly. “Premium” doesn’t protect you when local competitors learn quickly and market dynamics change. And in consumer goods, political risk isn’t abstract—because when the product is tied to national identity, the demand curve can bend overnight.

VIII. The ESG Leadership Pivot: Kirei Lifestyle Plan

In April 2019, Kao launched what would become a defining piece of its modern identity: the Kirei Lifestyle Plan—an ESG strategy meant to tie sustainability to the same thing that made Kao dangerous in the first place: product innovation people can feel.

“Kirei” is one of those Japanese words that doesn’t translate cleanly into English. It can mean clean, beautiful, well-ordered—sometimes all at once. Kao leaned into that ambiguity on purpose. For the company, “kirei” isn’t only about appearance. It’s also about how you live and what you leave behind: creating beauty for yourself, for others, and for the world around you.

The plan laid out 19 leadership actions aimed at a more sustainable, desirable way of living. And it came with a big 2030 ambition: Kao said it wanted to empower at least 1 billion people to enjoy more beautiful lives, and to have 100% of its products leave a full lifecycle environmental footprint that science says the natural world can safely absorb.

This wasn’t positioned as a feel-good side project. Kao paired the narrative with targets—especially on decarbonisation. In its progress reporting, Kao described updated goals that aim to make the company carbon-free by 2040 and carbon-negative by 2050. The company received certification for a 2.0°C target from the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) in 2019, and later amended its target to align with SBTi’s 1.5°C standard.

Some of the work is unglamorous, but it’s where consumer goods companies either get serious or get exposed. Take palm oil—one of Kao’s key raw materials. Kao said it was aiming to build traceability through the supply chain, all the way down to oil palm plantations, as part of sustainable procurement.

There’s also the external scorekeeping. CDP, which runs global disclosure and evaluation programs around climate change and water management, has continuously selected Kao for its A List across climate change, forest, and water since 2020.

And then there’s ethics and governance—less visible in a shampoo aisle, but central to how a 130-plus-year-old company keeps trust. The Ethisphere Institute’s list of the World’s Most Ethical Companies has included Kao continuously since the list began in 2007.

What’s very Kao about all of this is that the ESG story doesn’t stay confined to policy documents. It loops back into product and technology.

In 2021, two Kao products—the 3D Space Shampoo Sheet and the Space Laundry Sheet—were chosen to be sent to the International Space Station with JAXA in 2022. Space is obviously not Kao’s core market. But the selection is a signal: the company’s formulation and materials know-how can work in extreme constraints, and the halo effect is the kind of earned publicity you can’t simply buy with ad spend.

The more telling example, though, is one that predates the Kirei Lifestyle Plan by decades—and arguably shows the same worldview more clearly than any ESG slogan.

In 1991, Kao added a raised mark to shampoo bottles so people could identify them by touch. It developed the idea in cooperation with a school for the blind, responding to requests from visually impaired consumers. The utility-model patent application centered on two functional choices: the notches created tactile recognition, and placing them on the rear and vertically preserved the bottle’s look while not getting in the way of manufacturing steps like labeling. The notched bottles debuted in October 1991, and the approach went on to become an industry standard in Japan.

It’s a small design change with an outsized message: Kao’s best innovations often come from taking “the consumer” literally—including consumers most companies forget to design for.

For investors, the ESG pivot inevitably raises the hard question: is this a durable competitive advantage, or an expensive set of obligations? Kao’s argument is that sustainability forces better innovation—that constraints, properly used, produce superior products. Whether that ultimately shows up in long-term outperformance is still debated. But the company’s history does give the claim some weight: when Kao treats a real-world problem as an R&D problem—and then ships a practical solution—it tends to create value that lasts.

IX. Playbook: Business & Innovation Lessons

Kao’s 138-year history is full of product stories, but underneath them is a remarkably consistent playbook for building durable advantage in consumer goods.

R&D as Core Competency

Attack is the clearest expression of how Kao thinks. Four years collecting dirt samples from around the world. Two more years synthesizing the enzyme. Most consumer-goods companies would call that timeline unrealistic. Kao treated it as the cost of doing something that couldn’t be faked.

The payoff wasn’t just a better detergent. It was a step-change product that captured nearly half the market within six months and stayed a leader for decades. That’s not “continuous improvement.” That’s R&D as a moat. Competitors can copy features over time, but replicating the scientific depth and institutional patience behind them is far harder.

The Yoki-Monozukuri Philosophy

“Yoki” means good or excellent. “Monozukuri” means making—craftsmanship, but also the discipline of production. Kao’s version, Yoki-Monozukuri, is essentially an excellent creation process that’s good for everyone involved and enriches lives.

In practice, it’s a different operating system than the classic Western consumer playbook of speed-to-market and marketing-driven optimization. Kao starts with close consumer observation and pushes for quality first. That often means fewer launches, but the wins tend to matter more.

Consumer Centricity from Day One

Kao’s consumer focus isn’t a modern slogan—it’s been there for generations. Beginning in the 1930s, the company held workshops to interact with customers, then offered new lifestyle suggestions based on what it learned.

And sometimes that mindset produces innovations that look small but change behavior at scale. The shampoo bottle notch is the perfect example: Kao responded to requests from visually impaired consumers by adding a tactile mark so people could identify shampoo by touch. It made the product better for people most companies weren’t designing for—and then became a broader standard that helped everyone.

Vertical Integration Through Chemistry

Kao’s move into oleochemicals and specialty chemicals gave it a level of vertical integration that’s unusual for a consumer company. Yes, that can mean cost advantages and supply security. But the bigger benefit is competence: Kao deepened its understanding of the underlying materials that make products work.

When your edge comes from chemistry—not just sourcing and branding—the bar for competitors rises. You’re not only choosing ingredients; you’re learning how to engineer performance.

The Acquisition Integration Challenge

Kao’s acquisition history is a reminder that buying a business is easy compared to making it work.

Jergens, acquired in 1988, struggled to become a platform for Kao’s strengths in the U.S. Cultural differences—like bathing habits—made some product ideas hard to translate, and competition from P&G and Unilever made organic growth punishing.

Kanebo, acquired eighteen years later, showed a different integration philosophy. Kao kept Kanebo operating independently, protecting brand identity and retail relationships. Integration moved gradually over roughly fifteen years, aiming to preserve what made Kanebo valuable while connecting operations where it made sense.

The Diversification Cautionary Tale

Then there’s the floppy disk venture—a case study in how a real technical insight can still lead you into the wrong business. The science was legitimate: surface-technology work in cosmetics produced a method for dispersing magnetic particles, which turned out to be useful in data storage. But manufacturing and selling information-technology products demanded capabilities far from Kao’s consumer-goods core. Even after becoming North America’s largest floppy disk maker, the business never became profitable.

For investors, the throughline is capital allocation discipline. Kao has shown a willingness to exit businesses that don’t meet the bar—pet care, beverages, and local diaper manufacturing in China. When the company sticks to that discipline, it keeps resources aimed at the domains where Kao’s real advantage is hardest to copy.

X. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Forces and Strategic Powers

To see where Kao can win—and where it’s structurally fighting uphill—you need two lenses. One is the shape of the industry it operates in. The other is the set of advantages Kao has spent more than a century building.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low-Medium

In Japan, getting into Kao’s categories at scale is still hard. Decades-long distribution relationships, household-name brands, and manufacturing scale create real friction for new players. Kao also tends to hold a number one or number two position across many of its home categories, which makes the incumbency advantage very real.

But that protection fades outside Japan. In emerging markets, distribution is less locked up, local brands can scale quickly, and “Japanese quality” premiums can erode once domestic competitors close the performance gap. China’s diaper market is the cautionary tale: local players steadily learned, improved, and took share.

Supplier Power: Low

Kao’s supplier risk is cushioned by something most consumer companies don’t have: vertical integration into oleochemicals. The company produces many of its own material inputs, which reduces dependence on any single supplier and deepens control over formulation-critical components.

For commodity inputs like palm oil, Kao still sources globally. But it has also aimed to build traceability through the supply chain, down to plantations, as part of sustainable procurement. That work does double duty: it supports ESG commitments, and it gives Kao better visibility into a key input that can otherwise become a blind spot.

Buyer Power: Medium-High

Retail is concentrated, and that concentration shifts leverage toward the buyer. Large retailers can push for promotions, better shelf placement economics, and price concessions—classic consumer-goods gravity.

Kao has also had to manage a more price-conscious consumer in Japan, which is particularly painful when you’re selling products that are meaningfully premium, like Attack.

E-commerce complicates the picture. In theory it can reduce retailer gatekeeping; in practice, Kao hasn’t been one of the most aggressive consumer giants in direct-to-consumer, so the power shift doesn’t automatically flow to Kao.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium

Private label is the ever-present alternative in mature markets. At the same time, newer brands that lead with “natural” or “clean” positioning can pull consumers who care about ingredient transparency and sustainability.

The good news for Kao is that this isn’t an alien battleground. Its sustainable-innovation efforts and proprietary technologies like Bio IOS give it a credible way to compete for those consumers, rather than simply getting undercut by the next label with better storytelling.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a knife fight, globally. Kao competes against companies like P&G, Unilever, L’Oréal, and Shiseido—players with massive scale, entrenched distribution, and the ability to outspend.

The historical benchmark makes the point starkly: in the mid-1990s, P&G spent about four times as much as Kao on R&D. It then captured about half the shampoo market in China and Taiwan, while Kao’s shares in those markets were far smaller. Kao can’t brute-force its way to global share in every category, so it’s forced into choice: where to play, and how to win without matching the spending arms race.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

In Japan, Kao’s scale is meaningful and self-reinforcing. Leadership positions support sustained R&D investment—Attack’s multi-year development arc being the extreme example of what Kao will fund when it believes the prize is category-defining.

Outside Japan, scale is thinner. Kao doesn’t have the global manufacturing and distribution footprint of P&G or Unilever, and that limits unit-economics advantages in many markets.

Network Effects: Low

Most consumer packaged goods simply don’t have true network effects. The closest Kao gets is in professional channels: Goldwell’s salon business has a kind of stickiness, because salons invest in training and relationships. That can create durability, but it still isn’t the flywheel you see in software or platforms.

Counter-positioning: Moderate-High

Kao’s sustainability emphasis and its “quality at a fair price” posture create a real form of differentiation—neither pure luxury nor a race to the bottom. That positioning can be awkward for larger incumbents to copy without disrupting their existing product ladders.

And culturally, Yoki-Monozukuri is a different operating system from the Western consumer-goods playbook. Whether it becomes a lasting advantage or stays a distinctive internal philosophy depends on execution, but it clearly shapes how Kao prioritizes and builds.

Switching Costs: Low-Medium

For most consumers, switching shampoos or detergent is easy. The cost is low, and the effort is minimal.

Still, efficacy and trust create a soft switching cost: if a product reliably works, many consumers don’t bother experimenting. And in the professional salon channel, Goldwell benefits from higher switching costs because relationships and training matter.

Branding: High in Japan, Moderate Globally

In Japan, Kao’s brands have multi-generational presence. That kind of heritage creates emotional familiarity that a new entrant can’t manufacture quickly.

Globally, Kao is more uneven. Its acquired brands—Kanebo, John Frieda, Molton Brown—are meaningful in their niches, but they don’t add up to the kind of universally recognized brand architecture that P&G or L’Oréal can lean on across categories and countries.

Cornered Resource: High

If Kao has a “secret weapon,” it’s not one hero brand—it’s capability. Surface chemistry and biotech-driven R&D, plus proprietary technologies like Bio IOS, create an institutional advantage that doesn’t reset each product cycle.

Kao has maintained an unusually high share of employees in R&D for decades, which compounds into know-how and problem-solving depth. This cornered resource isn’t any single patent. It’s the organization’s accumulated ability to understand surfaces—fabric, skin, hair, dirt—and then engineer performance that consumers can feel.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re tracking whether Kao’s strategy is working, two metrics matter most:

-

Like-for-Like Sales Growth by Region: It removes currency noise and shows actual momentum. Watch Japan for stability, Asia outside China for scalable growth, and China for whether the business can regain footing.

-

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC): K27 makes ROIC a central discipline. Kao has explicitly targeted improvement off the level it achieved in fiscal 2024. The direction here is the tell on whether restructuring is truly turning into better capital efficiency, not just cleaner narratives.

XI. Myth vs. Reality: Evaluating the Investment Thesis

By this point in the story, it’s tempting to compress Kao into a few clean narratives: “Japan’s P&G,” “a beauty powerhouse after Kanebo,” “R&D as an unstoppable engine,” “China as the obvious next leg.” Each has a kernel of truth. Each also hides the sharper edges investors actually have to underwrite.

Here’s how the big myths stack up against reality.

Myth: Kao is a Global Consumer Goods Company

Reality: Kao has spent decades pushing outward, but it’s still anchored heavily in Japan. Overseas sales are less than half of revenue, and the most consistent profitability has tended to come from Japan and parts of Asia. In other words, Kao looks less like a fully global peer to P&G or Unilever, and more like a dominant Japanese champion with selective international businesses that work when the fit is right.

That isn’t inherently bad—focus can be an advantage. But it does mean geographic concentration risk is real, and it shows up fast when a key region turns.

Myth: The Kanebo Acquisition Transformed Kao Into a Cosmetics Powerhouse

Reality: Kanebo undeniably expanded Kao’s cosmetics footprint and gave it the channels and brand ladder Kao didn’t have. But “bigger” isn’t the same as “fixed.” The beauty business has been volatile, and the numbers reflect the strain: cosmetic sales fell 3.7% on a like-for-like basis, and operating profit was negative JPY7.9bn. China weakness and the complexity of operating prestige beauty at scale have kept the segment from reaching the potential the deal implied.

Kanebo made strategic sense. The harder truth is that the transformation has been slower and more difficult than the headline suggested.

Myth: Kao’s R&D Advantage Translates Automatically to Market Success

Reality: Kao’s science advantage is real—but it’s not a magic wand. The floppy disk venture and the ActiBath miss in the U.S. are reminders that great technology doesn’t guarantee product-market fit. Consumer habits, rituals, and channels matter just as much as formulation.

The best way to think about Kao’s R&D is as a durable edge that compounds when applied with discipline—when Kao is solving a problem it understands deeply in a market it truly knows.

Myth: China Represents Kao’s Most Important Growth Opportunity

Reality: In recent years, China has looked less like a growth engine and more like a volatility amplifier. Local competition, shifting market structure, and political risk have combined to erode Kao’s position. The restructuring moves under K27 signal that management is already revising the old assumption that China could carry the global story.

If Kao has a clearer growth runway, it may be in markets where it has stronger footing—Southeast Asia and India—rather than in a China thesis that now requires far more humility.

Bull Case Summary

- Strong positions in Japan generate stable cash flow that can fund R&D and selective international expansion

- Deep surface-science capabilities create a real competitive advantage that strengthens over time

- K27’s restructuring is designed to concentrate effort on higher-return opportunities

- ESG leadership could align well with consumer preferences moving toward sustainability

- Premium positioning in parts of Asia benefits from rising middle-class consumption

- A long track record of dividend growth—36 consecutive years—signals financial discipline

Bear Case Summary

- Heavy reliance on Japan caps growth as the population ages and the market matures

- China headwinds may persist due to structural competition and political risk

- Beauty profitability has remained difficult even after the Kanebo acquisition

- Scale disadvantage versus P&G and Unilever makes global category wars expensive

- Premium pricing is vulnerable in downturns as consumers trade down

- Yen volatility creates meaningful currency translation risk

Regulatory and Accounting Considerations

Kao adopted IFRS in 2016, bringing its reporting in line with international standards. On governance, the company has an eight-member board with four inside directors and four outside independent directors, alongside a five-member Audit & Supervisory Board made up of two full-time members and three outside independents.

On the softer—but still meaningful—signals, Kao has been continuously selected for the World’s Most Ethical Companies list since it began in 2007, which offers some reassurance around governance culture and compliance discipline.

The main risks worth monitoring are straightforward and recurring:

- Currency translation impacts, given significant yen exposure

- Raw material volatility, particularly palm oil and petrochemicals

- Regulatory shifts affecting cosmetics and chemical products in key markets

- Further deterioration in China demand or operating conditions

Kao is, at its core, a distinctive model: a science-driven consumer goods company built on Japanese manufacturing excellence and unusually deep research capabilities. Over more than a century, it has shown it can turn fundamental R&D into products that genuinely change behavior. The investor question is narrower—and harder—than the mythology: can that model keep producing attractive returns as Kao navigates global scale disadvantages, China volatility, and shifting consumer behavior?

Tomiro Nagase’s line still hangs over the entire story: “Good fortune is given only to those who work diligently and behave with integrity.” Kao has never lacked diligence or integrity. The next chapter is whether those virtues, paired with sharper capital discipline, translate into durable advantage in 21st-century consumer goods.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music