Nomura Research Institute: Japan's Hidden Tech Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction: The Invisible Backbone of Japan's Financial System

Picture a weekday morning in Tokyo. The opening bell is about to ring. Screens flicker, phones light up, orders hit the market—and within seconds, an ocean of trades starts moving through the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

To most people, the action is what happens on the surface: the buy, the sell, the price tick. But the market only works because of what happens underneath. Trades have to be processed. Positions updated. Cash and securities moved. Mutual funds valued precisely and on schedule. And powering a stunning share of that “underneath” is a company almost no one outside Japan talks about.

Nomura Research Institute sits in the middle of it. Roughly half of Tokyo Stock Exchange trading volume runs through NRI’s infrastructure platforms, THE STAR and I-STAR. Zoom out and the footprint gets even bigger: more than half of Japan’s daily stock trading, a large chunk of Japanese government bond transactions, and the majority of mutual fund transactions flow through systems operated out of NRI’s data centers—built for reliability, security, and the kind of uptime financial markets demand.

And yet, outside of Asia, NRI is close to invisible.

That’s the paradox that makes this story so fun: Nomura Research Institute, Ltd. is Japan’s largest economic research and consulting firm and a member of the Nomura Group. But if that’s all you think it is, you’re missing the plot. Calling NRI “a research firm” is technically correct in the same way calling Amazon “a bookstore” is technically correct.

By March 31, 2025, NRI had grown to over 16,000 employees globally, and in Fiscal Year 2024 it reported 764.8 billion yen in revenue. The reason it can get that big—and stay that essential—is its unusual hybrid model. NRI pairs high-end research and consulting with the unglamorous, mission-critical work of enterprise IT systems integration. Not as separate lines of business, but as a single machine: insight that turns into operating systems for entire industries.

For investors, the interesting part isn’t that NRI “disrupts” anything. It’s that NRI becomes infrastructure. It embeds itself so deeply into workflows, regulations, and day-to-day operations that replacing it starts to feel less like switching vendors and more like attempting open-heart surgery mid-marathon. That’s why many global securities firms entering Japan—and many domestic wholesale brokerages already there—end up on I-STAR/CORE, the de facto standard.

The arc of this company stretches across six decades, two defining corporate combinations, multiple economic crises, and a strategy that treated “digital transformation” as a practical necessity long before the phrase existed. It’s a case study in how to build switching costs, how to thrive in regulated markets, and how winning in enterprise technology often means playing the longest game in the room.

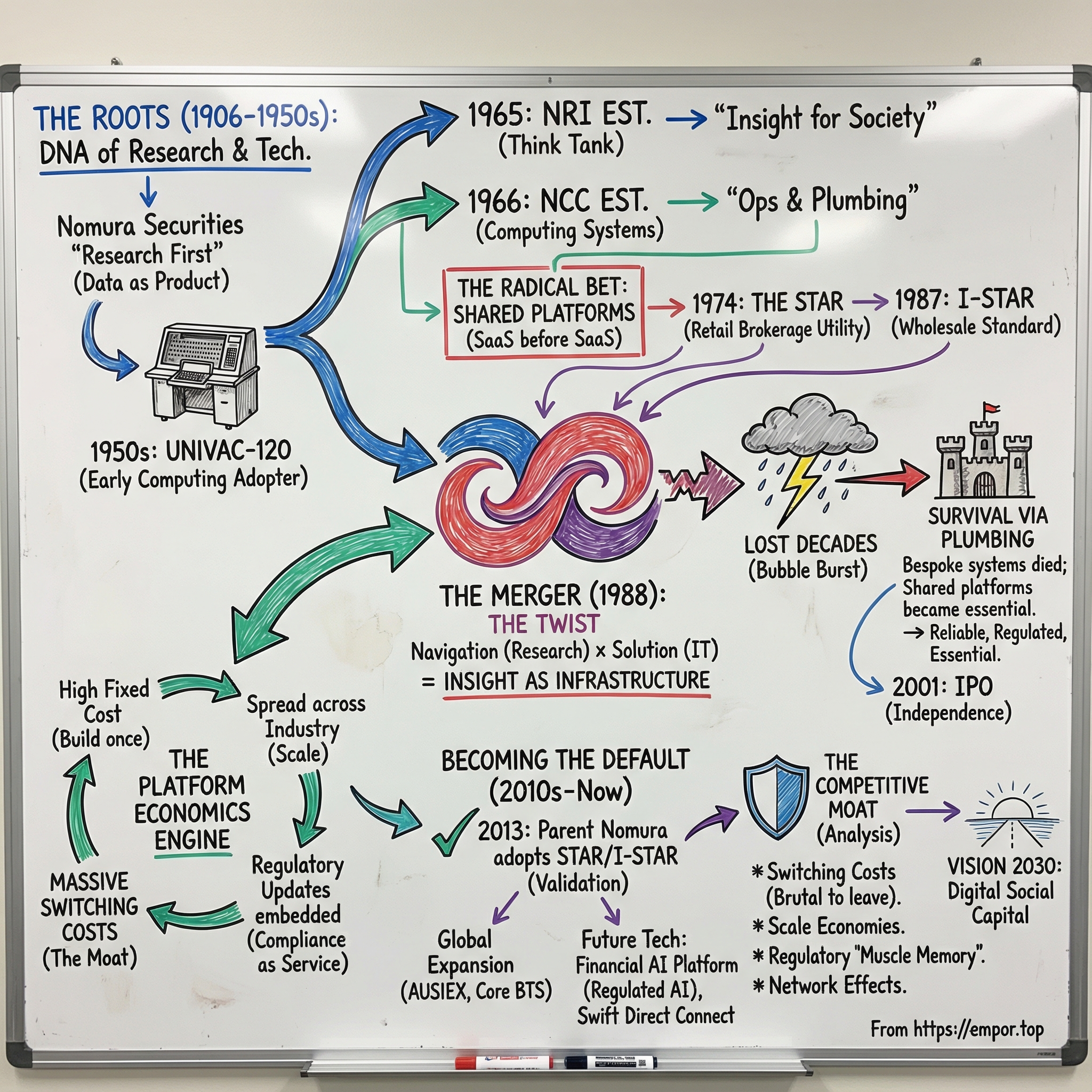

II. The Nomura Origin Story: A Research Obsession Takes Root (1906–1965)

To understand where NRI comes from, you have to start with something that looks, at first, almost old-fashioned: the Nomura family’s conviction that rigorous research isn’t a nice-to-have, it’s the business.

That DNA goes all the way back to 1906, when Nomura Tokushichi Shoten created a dedicated research department—an early, deliberate bet that analysis could be product. That tradition carried forward through Osaka Nomura Bank and, later, Nomura Securities.

Tokushichi Nomura II ran the firm with a simple guiding idea: “putting the customer first.” But in this era, that didn’t mean slogans. It meant building an internal machine for understanding markets better than anyone else. The research group, led by Kisaku Hashimoto, published the Osaka Nomura Business News, a steady stream of trading updates, stock analysis, and economic trend insights. For investors, it was actionable intelligence. For Nomura, it was a reputation moat.

And it mattered because, at the time, a lot of securities business still ran on relationships and intuition. Nomura tried something different: make data and analysis the center of gravity. The result was that their research became essential reading, and that “research-first” identity stuck. Decades later, it would become the cultural foundation for a company that sells not just ideas, but the systems that operationalize them.

Then comes the second thread in the NRI origin story—computing—and Nomura got there startlingly early.

In 1953, Nomura Securities established an Electronic Data Processing Division. It would eventually become the root system for NRI’s IT business. And in the mid-1950s, this group did something historic: it became the first in Japan to use a commercial computer, the UNIVAC-120, for business operations.

It’s hard to overstate how weird and forward-leaning that was. In an economy still heavily dependent on manual bookkeeping, Nomura was experimenting with electronic processing for the kind of work securities firms drown in: confirmations, settlement records, account statements, regulatory reporting. This wasn’t tech for tech’s sake. It was a direct response to an operational truth: whoever could process volume faster, with fewer errors, would win.

Nomura’s early embrace of computing wasn’t a side project. It was the seed of a future advantage—one that would eventually scale beyond Nomura itself.

That brings us to the formal birth of NRI.

In April 1965—timed to commemorate Nomura Securities’ 40th anniversary—Nomura Research Institute was established as Japan’s first full-fledged private think tank, spun out of Nomura Securities’ research department. Unlike many think tanks overseas, it was created as a joint-stock company from day one, shaped by the needs of post-war Japan: rapid industrialization, rising complexity, and a growing demand for institutions that could translate analysis into national economic and corporate capability.

The founding prospectus didn’t hide the ambition. It described NRI as “a new type of research institute that had never existed in Japan before,” with a mission to “promote industry and be of service to society through research studies.”

In other words: research, not as commentary, but as infrastructure for progress.

III. The Dual Birth: Think Tank Meets Computer (1965–1988)

A year after NRI was spun out as a think tank, Nomura quietly set up the other half of the future company.

In January 1966, Nomura Computing Center Co., Ltd. (NCC) was founded. It was later renamed Nomura Computer Systems Co., Ltd. in 1972. The mission was straightforward: take the system development skills Nomura Securities had built in-house and use them to streamline management—not just for Nomura, but for other companies too. It was the same “service to society” idea as the think tank, just expressed in code and operations instead of reports.

The result was an unusual setup: two sibling companies with complementary jobs. The original NRI did research and consulting. Nomura Computer Systems built and ran the pipes—production systems, processing, operations. For roughly two decades, they grew up separately, building different customer bases and different kinds of institutional muscle.

And the computing arm didn’t just build custom systems one client at a time. It went after something far more powerful: a shared platform.

In May 1974, it launched THE STAR, a joint online back-office system for securities companies. The idea was radical for its time. Instead of every brokerage building—and constantly rebuilding—its own settlement, accounting, and operational infrastructure, they could plug into a common system and share it. Costs got spread across participants. Standards tightened. Reliability improved.

In other words, it was the bones of a SaaS-like model decades before anyone used that label.

THE STAR grew into Japan’s most widely used brokerage system, and it kept evolving. Built from what became known as NRI’s STAR System—an early pioneer in straight-through processing—it has been developed and upgraded continuously for decades. And in securities, where firms live and die by speed and accuracy, “good enough” isn’t good enough. Immediacy is the product.

The economics did the rest. Building a proprietary back-office stack meant big upfront hardware and software costs, plus a permanent team to keep it running and compliant. A shared platform let smaller firms access enterprise-grade capabilities without carrying the full burden themselves. Then the flywheel kicked in: more participants made the platform more valuable, and leaving it became harder and riskier.

That same playbook expanded.

In October 1987, the company introduced I-STAR for wholesale securities firms—covering operations from execution through settlement and accounting, while continually updating for the ever-changing demands of Japan’s securities industry. Since launch, I-STAR has been adopted by more than 100 financial institutions and became the de facto standard for Japan’s wholesale securities back office.

(And the third member of the family, T-STAR for investment trust companies, would arrive later in 1993—completing the trifecta of shared infrastructure that would eventually underpin huge swaths of Japanese finance.)

While the platform strategy was taking shape, the 1980s were also a period of systematic build-out. Nomura expanded its securities systems into three core pillars: a retail securities system for brokerage operations, an investment banking system built for global markets, and an investment information database that sat at the center of the business.

At the same time, the research side started looking outward. Offices opened in New York in January 1967 and London in November 1972, giving NRI a front-row seat to global financial trends and policy shifts. Those outposts would matter more and more as Japanese finance became increasingly international.

IV. The Merger That Changed Everything (1988)

By the mid-1980s, leaders inside both the think tank and the computing arm could see the ground shifting under Japanese corporate strategy. Information technology wasn’t just a back-office efficiency play anymore. It was becoming inseparable from the business itself. And the firms that could connect the “why” of strategy to the “how” of implementation were going to own the future.

That’s the context for the move that created the NRI we know today.

In January 1988, the former Nomura Research Institute, Ltd.—founded in 1965 as Japan’s first full-fledged private sector think tank—merged with Nomura Computer Systems Co., Ltd., the computing company established in 1966 that helped pioneer commercial computer applications in Japanese business. Out of that combination came the present-day Nomura Research Institute (NRI).

On paper, it sounds like a straightforward corporate reorg. In reality, it was a blueprint. The merger fused a research-and-consulting institution with an IT solutions provider, under one roof, with one mandate: don’t just advise—build, run, and continuously improve the systems that make the advice real.

With the merger, NRI became a total provider of research, consulting, IT solutions, and system operations.

And in 1988, that was a genuinely unconventional idea. Consulting and IT services mostly lived in different worlds. One side delivered strategies in decks. The other delivered systems in code. NRI was betting that the value—and the defensibility—came from unifying them.

Inside the company, this philosophy became what NRI calls its “Navigation and Solution” approach: use research and consulting to navigate what the business should do next, then deliver the solution as working infrastructure. It’s the mindset that sits behind platforms like THE STAR, I-STAR, and later T-STAR—systems that didn’t just modernize workflows, but quietly set industry standards across securities and investment trusts.

The merged company inherited two powerful advantages at once. From the research institute: intellectual credibility and an ability to see around corners. From the computing systems company: deep operational expertise and a growing installed base of mission-critical systems. But the most important inheritance was cultural. Both organizations had been shaped by Nomura Securities, which meant they were trained to think in decades, not in billable hours.

That Nomura DNA mattered because financial institutions don’t judge technology vendors on clever features. They judge them on whether the system is there, every day, without drama—and whether the provider shows up when things get complex. In markets, reliability isn’t a KPI; it’s survival. NRI built itself around that reality, and after the merger, it could deliver it end-to-end: insight, implementation, and operations, all bound together.

V. Surviving the Lost Decades: The IPO and Strategic Transformation (1990–2001)

NRI’s 1988 merger happened at exactly the wrong—and right—moment. Japan’s asset bubble was cresting when the new company came together. Within two years, it popped, and the country slid into what became known as the Lost Decades.

A big part of the setup traces back to September 1985 and the Plaza Accord. The yen surged, putting pressure on Japan’s export-driven economy. Policymakers responded with stimulus and rate cuts in 1986 and 1987—moves that helped pour fuel on already-rising land and stock prices. When that cycle broke, it didn’t just bruise Japan’s financial system; it changed its behavior for years.

The “Lost Decade” label was originally the 1990s, but as stagnation dragged on, commentators expanded it to include the 2000s and even the 2010s. From 1991 to 2003, Japan’s GDP grew only about 1.14% annually—a long stretch of low growth that rewired corporate decision-making across the country.

For a company so intertwined with finance, this could have been fatal. Banks failed. Securities firms merged. Budgets tightened. And when financial institutions get nervous, big technology projects are usually the first thing put on ice. Plenty of vendors that lived off one-off, bespoke builds didn’t make it through.

NRI did, and the reason is the same reason it became infrastructure in the first place: it leaned harder into shared platforms.

Instead of relying primarily on custom systems for individual clients, NRI emphasized shared infrastructure services that spread costs across many participants. In a downturn, firms can delay new builds and cut discretionary spend, but they can’t pause settlement. They can’t “wait until next year” to value mutual funds. The daily machinery of markets still has to run—accurately, securely, and in compliance with regulations.

That shift turned out to be more than a business model tweak. It created something that, in today’s language, looks a lot like recurring revenue protected by brutal switching costs. Once a securities firm was running on THE STAR, leaving wasn’t a normal vendor change. It meant rewiring operations: regulatory reporting, settlement interfaces, compliance workflows, and the countless edge-case processes that only show up at scale. NRI’s systems weren’t just software anymore. They were the operating environment.

Then came the moment that formally separated NRI’s destiny from its parentage.

In 2001, NRI was listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The IPO was a milestone not just because it opened access to public capital, but because it reduced dependence on Nomura Holdings and strengthened NRI’s identity as its own company. While NRI maintained certain capital ties with Nomura Holdings, it was not a subsidiary—and that distinction mattered. It meant NRI could serve firms that competed with Nomura Securities without every deal carrying the shadow of a conflict.

Over time, NRI went on to achieve long-term growth in both revenue and operating profit, with the usual bumps that come with economic cycles. And by April 2015, it celebrated the 50th anniversary of its founding—a quiet marker for a company that had just made it through Japan’s toughest economic era by becoming harder and harder to replace.

VI. Becoming Japan's Financial Infrastructure (2010–Present)

In the decade after the IPO, NRI didn’t chase growth by reinventing itself. It did something more effective: it compounded. It expanded from a critical vendor to something closer to a default setting, using its installed base to add services and deepen integration while the practical barriers to competing—regulatory, operational, and reputational—kept rising.

The symbolic turning point came on January 4, 2013. Nomura Securities updated its core IT system and began operating the STAR brokerage back-office system. That detail matters because Nomura wasn’t just any customer. It was the parent that had originally incubated both halves of NRI’s predecessor companies. And now it was moving onto the shared platform.

NRI announced that implementation of its two ASP back-office systems, THE STAR and I-STAR, had been completed at Nomura. The result: Nomura discontinued its in-house back-office systems for retail markets and street-side settlement of capital markets in Japan.

This wasn’t because Nomura’s homegrown system didn’t work. It was flexible. But it had become expensive to maintain, requiring continuous updates that made the back office more intricate and complex year after year. Eventually, even for Japan’s largest securities firm, the economics flipped.

And that was the real validation of NRI’s model. If the most sophisticated player in the market decided it no longer made sense to carry bespoke infrastructure, everyone else got the message. Shared systems weren’t a compromise. They were the new standard.

On the asset-management side, NRI’s grip was just as strong. T-STAR holds an 80% share in the calculation of the “reference NAVs of open-end funds” published daily in Nikkei. Through T-STAR/TX, NRI supports back-office operations for investment management companies—extending its dominance from securities processing into the daily mechanics of mutual funds.

With Japan’s core platforms firmly entrenched, NRI pushed outward.

In 2016, NRI acquired Cutter Associates. In 2018, it established a subsidiary in India, expanding delivery capacity and strengthening its global footprint.

Then came Australia. NRI’s wholly owned Australian subsidiary reached an agreement to acquire 100% of the shares of Australian Investment Exchange Ltd (AUSIEX) from Commonwealth Bank of Australia. AUSIEX provides trade execution, settlement, and portfolio administration solutions for independent financial advisors and major financial institutions—an attractive position in a growing market. The deal was reported at $85 million in cash, and in May 2021, NRI completed the acquisition, making AUSIEX a wholly owned subsidiary of Nomura Research Institute Australia Pty Ltd.

North America followed via a different play: managed services and IT consulting at scale. In December 2021, Core BTS announced the completion of NRI’s acquisition of the company from Tailwind Capital. Core BTS positioned NRI as a long-term partner to accelerate digital transformation in the U.S. and continue supporting clients with complex technology challenges. After the acquisition, Core BTS began operating more seamlessly alongside its sister companies, NRI America and NRI IT Solutions America (ITSA).

Meanwhile, the next platform era was taking shape: AI, designed for the realities of regulated finance rather than consumer hype cycles.

NRI is set to launch the NRI Financial AI Platform in the first half of 2025, built to meet financial institutions’ demands around data privacy, security, and data sovereignty. To do it, NRI plans to integrate Cohere Inc.’s LLM, Command R+, through the Oracle Cloud Infrastructure Generative AI service. The focus is practical: accuracy with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), multilingual support for global operations, and tool use to automate complex tasks—combined with NRI’s financial business data and IT solutions to improve transparency, avoid hallucinations, and keep data secure and private.

And NRI has been upgrading the plumbing, too. In March 2024, it announced that its post-trade solution, I-STAR/GX, began offering a direct connection to Swift. The connection was provided to Tokai Tokyo Securities Co. Ltd, and NRI described it as the first case in the world where a post-trade system directly connected to Swift without a pre-prepared interface. The industry noticed: I-STAR/GX was later awarded “Best Cutting-Edge Solution” at the FTF News Technology Innovation Awards 2025, recognizing that same “first direct connectivity” milestone.

The pattern across all of it is consistent. NRI doesn’t win by flashy disruption. It wins by becoming the safest, most embedded way for markets to keep functioning—then exporting that capability, one carefully chosen expansion at a time.

VII. The Business Model: Platform Economics at Scale

To really understand NRI, you have to understand how it’s organized—and why that structure is so unusual.

NRI operates across four segments: Consulting, Financial IT Solutions, Industrial IT Solutions, and IT Platform Services. Consulting covers management and systems consulting. Financial IT Solutions spans the core plumbing of securities, banking, and insurance. Industrial IT Solutions brings the same systems-and-operations playbook to sectors like distribution, healthcare, manufacturing, and services. And IT Platform Services sits underneath everything—IT infrastructure, system management, and advanced technology solutions that keep the whole machine running.

In other words, NRI isn’t “a consulting firm” that happens to do IT, or “an IT vendor” that happens to publish research. It’s built to do both, end-to-end.

Financial IT Solutions is the center of gravity. It’s NRI’s largest division, contributing roughly half of consolidated revenue, and it houses the platform businesses that made the company indispensable to Japanese finance in the first place.

Those platforms are why NRI became the de facto standard for mutual fund accounting and sales management in Japan. They give financial institutions something deceptively simple: a shared, scalable system that stays compliant, stays accurate, and stays up—day after day, through every market cycle.

And the platform model has the kind of economics that enterprise infrastructure businesses dream about. The hard part—building and operating the core infrastructure—has already been done. When a new customer joins THE STAR or I-STAR, revenue grows faster than costs. You need incremental capacity and support, but you don’t need to rebuild the engine. Over time, that’s how platforms quietly expand margins: not through flashy reinvention, but through reuse.

The real moat, though, is where the platform meets regulation.

Finance runs on rules, and those rules change constantly. Japan’s Financial Services Agency updates regulations on an ongoing basis, and every change has downstream consequences for how institutions report, reconcile, settle, and manage risk. If you run your own proprietary system, you don’t just “comply” once—you carry the permanent obligation to interpret every update, implement it correctly, test it, and deploy it without breaking daily operations.

If you’re on NRI’s platforms, that burden shifts. NRI builds the regulatory change once, integrates it into the platform, and every participant benefits. Compliance becomes a shared service.

That’s where the lock-in becomes less about software and more about capability. Leaving the platform isn’t just swapping vendors. It’s rebuilding an entire in-house function: the people, processes, and technical muscle required to track and implement regulatory changes in near real time, reliably, and without incident. Very few institutions want that job back.

Across NRI, Financial IT Solutions represents the majority of its work with broker-dealers, asset managers, banks, and insurers. And it all traces back to the company’s underlying DNA: research and analysis on one side, and system design, construction, and operation on the other—bound together in what NRI calls “Navigation x Solution.”

VIII. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

NRI’s position is protected by the kind of barriers you don’t see in flashy tech markets: time, trust, regulation, and sheer operational gravity.

Start with the installed base. Since launching in 1987, I-STAR has been adopted by more than 100 financial institutions and became the de facto standard for Japan’s wholesale securities back office. Even if a new entrant had the engineering talent and the funding, copying the software would be the easy part. Replicating decades of integrations, operational know-how, and institutional confidence would take years—if not longer.

Then there’s the infrastructure reality. Running financial-grade systems means data centers designed for extreme security, reliability, and continuity. That’s enormous upfront investment before you’ve won a single meaningful client.

But the biggest barrier isn’t capital or code. It’s regulatory muscle memory. NRI’s teams don’t just read the rules; they’ve lived through how those rules evolved, how they’re interpreted in practice, and what changes tend to come next. They’ve built relationships with regulators that help inform product development. A new entrant can hire experts, but it can’t fast-forward through decades of accumulated context.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Like every major IT services business, NRI runs on talent. And Japan faces a persistent shortage of skilled IT professionals, particularly in newer disciplines like AI, cybersecurity, and cloud architecture. An aging workforce and a limited pipeline of younger digital talent make hiring and retention a real constraint.

Cloud infrastructure vendors also have some leverage as NRI expands cloud-based offerings. Providers like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Oracle have pricing power and strategic importance. That said, NRI isn’t a small customer. Its scale gives it negotiating strength, and its own data center capabilities provide a credible alternative when it needs one.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW to MODERATE

When you’re the default platform for post-trade operations, buyer power looks very different. NRI supports broker-dealers’ core post-trade functions with deep operational expertise, and its systems sit directly in the path of settlement, reporting, and daily processing. That creates a relationship that’s less “vendor” and more “shared operating environment.”

The switching costs are the point. Moving off THE STAR or I-STAR isn’t a procurement decision—it’s a rebuild. You’d have to redesign workflows, retrain teams, reconstruct regulatory reporting, and accept meaningful operational risk during the transition. That’s why switching is rare: the downside is immediate and concrete, while the upside is uncertain.

Still, buyer power isn’t zero. Very large clients like Nomura Securities have leverage because of their scale, their long history with NRI, and the reality that they do have alternatives—at least in theory, and sometimes in specific areas.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

Fintech has reshaped plenty of finance, but mostly at the surface layer: consumer apps, digital onboarding, trading interfaces, robo-advice. Those products compete for customers. NRI competes at the plumbing layer—settlement, clearing, reconciliation, regulatory reporting—where failure isn’t an inconvenience, it’s a crisis.

Japan’s market structure also matters. The country’s financial practices and settlement systems are specific and complex, and they demand highly specialized, deeply tested solutions. THE STAR and I-STAR earned their status by being reliable, compliant, and scalable in that environment. A shiny new front end doesn’t replace the machinery underneath.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition is real, especially in broader IT services. Gartner’s 2023 market share data, published in August 2024, ranked NTT Data as the top player in Japan’s domestic IT services market, with revenue of 1.611 trillion yen and an 11.0% share.

NRI also faces global competitors like Accenture and IBM, and domestic peers like Fujitsu. But rivalry is muted where NRI is strongest: specialized financial platforms and the ability to combine advisory work with system implementation and operations. Founded in 1965, NRI built a model that links research and consulting directly to production systems—helping clients manage risk, improve efficiency, and keep up with changing market demands. In the parts of finance where trust and continuity matter most, that integration is a differentiator that’s hard to attack head-on.

IX. Hamilton's 7 Powers: Sources of Competitive Advantage

Scale Economies: STRONG

NRI’s shared infrastructure businesses are built to do one thing exceptionally well: spread massive fixed costs across a wide customer base. Data centers, security, always-on operations, long-lived software, and the teams that keep everything compliant aren’t cheap. But once they’re in place, every new institution that joins THE STAR, I-STAR, or T-STAR adds revenue with far less incremental cost than building a bespoke stack from scratch.

That’s how NRI turns “plumbing” into a compounding business. THE STAR alone has become the de facto standard for retail securities back-office operations, especially among mid-sized and large brokerages, and it manages a huge share of individual securities accounts in Japan. When your product is the default, scale doesn’t just improve margins—it reinforces the standard.

Network Effects: STRONG

FundWeb is a good example of how NRI’s ecosystem advantage shows up in practice. It’s a network solution that connects BESTWAY and T-STAR/TX, and it holds a similar market share—another sign that, in Japan, NRI’s platforms don’t just serve participants; they connect them.

The dynamic is simple: the more securities firms that run on THE STAR, the more it becomes the common language of the industry. Interoperability improves. Operational patterns standardize. Asset managers benefit because they can connect to distributors already using the same platform. And for new entrants, plugging into the existing ecosystem is far easier—and less risky—than trying to build alternative infrastructure.

These network effects get extra leverage in Japan’s relationship-driven business culture. Institutions prefer counterparties whose processes and systems are compatible. NRI’s dominance makes its platforms the path of least resistance for firms that want to operate smoothly inside Japanese finance.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

If there’s one power that explains NRI’s durability, it’s this one.

Financial institutions don’t “use” NRI’s systems the way a company uses a software tool. Over years of production operation, their core processes wrap themselves around the platform: custom workflows, reporting formats, staff training, internal controls, and day-to-day operating routines. The system becomes the environment.

Regulatory change makes the lock-in even stronger. Firms on NRI platforms benefit from updates that track ongoing rule changes. If you leave, you’re not just migrating technology. You’re rebuilding the capability to interpret regulations, implement changes, test them safely, and deploy them without disrupting daily operations—all while taking on the transition risk that compliance could slip.

In finance, that risk isn’t theoretical. It’s existential.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

NRI’s “Navigation and Solution” model—research-led consulting paired directly with implementation and operations—puts it in a lane most competitors aren’t structurally built to enter.

The company itself is a product of that combination: the former Nomura Research Institute (Japan’s first full-fledged private comprehensive think tank) and Nomura Computer Systems, Inc. (a pioneer in using commercial computers for business purposes) merged to form today’s Nomura Research Institute, Ltd. That heritage is why NRI can move from “here’s what you should do” to “here’s the system that makes it real,” across management consulting, IT consulting, system integration, and development for financial and retail clients.

In theory, a traditional consulting firm could add deep IT delivery, or an IT services firm could add high-trust strategic research. In practice, it’s hard. It threatens existing business models, forces new operational disciplines, and demands credibility that takes years to earn. Most rivals find it easier to stay in their lane.

Branding: MODERATE

NRI is rated “A” by S&P Global Ratings Japan, and inside Japan, the brand carries weight. Being the country’s first private think tank, then proving itself as a trusted operator of mission-critical financial systems, creates a reputation that’s difficult for newer entrants to replicate.

Outside Japan, the story changes. NRI is still less widely recognized globally, and expansions into markets like North America and Australia require building awareness from a lower base—even when the underlying capability is world-class.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE to STRONG

NRI’s installed base is more than market share. It’s a stockpile of hard-to-copy assets: relationships built over decades, institutional knowledge of how Japan’s financial system actually runs, and the operational data and experience that come from being embedded in the daily flow of the industry.

That compounding effect extends to talent. Engineers who understand both Japanese financial regulations and enterprise-scale systems are scarce. NRI employs many of them, and that mix of domain and technical expertise is not something competitors can quickly hire their way into.

X. Key Performance Indicators: What Investors Should Track

If you’re underwriting NRI as a long-term compounder, you don’t need a hundred metrics. You need a few that tell you whether the flywheel is still spinning—and whether the moat is getting deeper or quietly eroding. Three are especially worth anchoring on:

1. Financial IT Solutions Revenue Growth Rate

This is the engine room. Financial IT Solutions is where NRI’s core advantage shows up most clearly, and it’s also where the economics should be the best.

The headline growth rate matters, but the mix matters just as much. Within this segment, platform revenue—recurring, subscription-like payments tied to shared infrastructure—should be the steady backbone. Project-based work can be lucrative, but it’s inherently lumpier and more cyclical. The key question is whether platform revenue is becoming a larger share of the segment over time. If it is, predictability improves, and the business starts to look even more like “infrastructure with upgrades” than “services with projects.”

If growth stalls for long stretches, it can signal the obvious risks: market saturation, competitive pressure, or weaker ability to sell additional services into the installed base.

2. Operating Profit Margin Trend

In a platform business, margins are the story—because they’re where you see scale economies turn into actual financial output.

NRI has posted strong profitability metrics, including a return on equity of 22.63% and a net margin of 12.96%. The expectation, over time, is that the platform model supports resilient or even expanding margins as fixed costs get spread across more customers and more volume.

If margins compress meaningfully, it usually means something changed: pricing pressure, higher operating costs, or new investment that isn’t paying back yet. It’s also useful to compare profitability across segments. Financial IT Solutions should generally lead, because it has the most defensible position. If margins in Industrial IT Solutions or Consulting start closing the gap, that could be great news—but it could also be a warning that the core is losing some of its edge.

3. Customer Retention and Platform Utilization Metrics

NRI’s real asset isn’t just market share—it’s continuity. The whole model depends on long-term relationships and deep operational embedding.

NRI doesn’t always disclose churn or utilization in fine detail, but investors should pay attention to whatever proxies are available: transaction volumes flowing through the platforms, adoption and usage trends for THE STAR, I-STAR, and T-STAR, and signs of account expansion inside existing clients. Any credible hint of rising customer departures should be taken seriously, because switching is hard—and if customers are choosing to switch anyway, something has gone very wrong.

Platform participation is a useful read as well. More institutions on the platforms suggests continued penetration. Higher revenue per institution suggests NRI is successfully expanding what it does for customers already inside the ecosystem.

XI. Bull Case: The Untouchable Franchise

The optimistic thesis for NRI rests on a few pillars—and they all rhyme with the same idea: once you become the plumbing, you stop competing like a normal company.

Permanent Infrastructure Status: NRI’s systems are so embedded in Japan’s financial stack that they’re starting to look less like “vendor software” and more like a utility connection. For existing customers, there aren’t many credible alternatives—and even fewer that feel worth the operational risk. The result is an installed base that can generate steady, predictable revenue through cycles, because the market can slow down, but settlement and accounting don’t get to take a quarter off.

Global Expansion Runway: NRI is dominant at home, but still relatively modest on the global stage. That’s what makes the recent moves interesting. Core BTS in North America, AUSIEX in Australia, and the broader buildout of international operations create growth paths that don’t depend on Japan’s market expanding. Just as important, NRI can take what it’s learned operating mission-critical systems in one of the world’s most demanding financial environments and bring that credibility to global institutions that do business in Asia.

AI and Digital Transformation Opportunity: NRI plans to use its Financial AI Platform to roll out new solutions in three areas where AI can matter immediately in regulated finance: supporting sales operations, supporting compliance operations, and pushing back-office work toward more advanced, more autonomous processing. NRI also plans to pair the platform with hands-on support from its data scientists and AI experts so customers can apply it safely and effectively in real financial workflows.

The broader bet is straightforward: AI in finance won’t be won by whoever demos the flashiest chatbot. It will be won by partners that can deliver useful automation while meeting strict requirements around security, data sovereignty, and regulation. NRI’s reputation for reliability—and its long-standing relationships—put it in a strong position to be that partner when budgets shift from experimentation to production.

Demographic Tailwinds in Services: Japan’s aging population adds a quiet, structural tailwind. As workforces shrink, financial institutions still have to maintain service levels, accuracy, and compliance. That pressure increases the value of automation and operational efficiency—the exact kind of unglamorous, high-impact work NRI has spent decades getting right.

XII. Bear Case: The Risks and Concerns

All of that said, infrastructure businesses don’t lose by getting “out-innovated” in a demo. They lose when the world around them shifts in a way that makes the old assumptions stop being true. A prudent bear case for NRI is less about a single knockout blow and more about a handful of slow-moving risks that can compound.

Japan Market Ceiling: Japan’s financial services market is mature, and consolidation is a fact of life. Fewer banks and securities firms eventually means fewer net-new platform customers. If NRI can’t grow internationally fast enough to offset a saturating home market, the outcome isn’t dramatic—it’s simply slower growth.

Technology Disruption Risk: NRI’s moat looks formidable today, but platform transitions have a way of rearranging the leaderboard. If cloud-native offerings from global hyperscalers become credible replacements for what NRI runs in its own environments, the basis of competition could shift. And while regulation has historically been a barrier that favors incumbents, generative AI could make parts of compliance and documentation work easier—reducing the complexity that helps keep new entrants out.

Key Customer Concentration: Nomura Securities is still a meaningful customer. If that relationship weakened—or if Nomura ran into financial trouble—NRI’s results would feel it. When you’re built around long-term, high-trust relationships, concentration risk isn’t theoretical. It’s real exposure.

Talent Shortage Intensification: Japan is projected to face a shortage of 220,000 IT professionals by 2025, with demand especially strong in AI, cybersecurity, and cloud computing. NRI’s product is reliability, and reliability comes from people as much as from architecture. If NRI can’t hire and keep the engineers it needs, quality can slip and innovation can slow—exactly the wrong combination in a business that competes on trust.

Currency and Macro Risks: Most of NRI’s revenue is yen-denominated. For foreign investors, even great operating performance can look mediocre if the yen weakens. On top of that, a severe financial crisis hitting Japanese banks and markets could shrink IT budgets across NRI’s customer base—especially for new projects, expansions, and upgrades.

Regulatory Change Risk: Part of NRI’s advantage is that regulation is complex and constantly evolving—customers lean on NRI to keep systems compliant without breaking operations. If regulation ever became meaningfully simpler, that dependence would weaken. It may be unlikely, but it’s one of the few scenarios that directly attacks a core pillar of the moat.

XIII. The View From Here: Where NRI Stands Today

As 2025 draws to a close, NRI looks less like a “company” in the ordinary sense and more like a fixture in Japan’s financial system—one that earned its place the slow way. It started as a research department, became a think tank, merged with a computing pioneer, and then spent decades turning that hybrid into something Japan’s markets now rely on. Not through hype, but through patient execution and long-lived relationships.

That’s the context for its next chapter. NRI frames its long-term direction as “NRI Group Vision 2030,” built around the corporate statement “Dream Up the Future.” The ambition is to stay ahead of the times by converging business and technology, looking beyond DX, and helping build what it calls “Digital Social Capital.”

The playbook to get there looks familiar: expand capabilities and footprint through targeted acquisitions. In 2021, NRI acquired Planit as part of its Vision 2022 strategy. It continued to broaden its presence in New Zealand by acquiring Qual IT and SEQA, and later added Shift Left in the UK as part of its Vision 2030 strategy.

Zoom out, and the strategic priorities haven’t really changed—just the playing field has widened. Defend and deepen the Japanese financial infrastructure franchise. Grow internationally through a mix of acquisition and organic development. And keep investing in AI and digital transformation capabilities that will shape the next era of competition in enterprise technology.

In the market today, NRI carries a market cap of $22.30 billion, trades at a price-to-earnings ratio of 32.24, and has a beta of 0.72.

For investors, that combination is the point: NRI is a Japanese technology business with real moats, operating in a niche where scale and switching costs can last a very long time. The valuation reflects that—more like a high-quality infrastructure compounder than a typical “services” story.

So the real question isn’t whether NRI is good. It’s whether the moat stays intact. If its platforms remain the irreplaceable plumbing of Japanese finance, today’s multiple may look reasonable over a multi-year horizon. If technology shifts or regulatory change meaningfully reduces switching costs, that premium can compress fast.

Either way, NRI is exactly the kind of business long-term fundamental investors should spend time on: hard to replicate, deeply embedded, and serving customers who can’t easily walk away. The returns will depend on entry price and patience—but the underlying business quality is difficult to ignore.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music