Sekisui Chemical: The Hidden Japanese Champion You've Never Heard Of

I. Introduction: The Invisible Giant Behind Your Windshield

Somewhere between your eyes and the road ahead sits a layer you’ve never thought about, but you absolutely rely on. It’s a thin, transparent plastic film—polyvinyl butyral, or PVB—sandwiched inside your windshield. In a crash, it helps keep the glass from exploding into dangerous shards. Every day, it also quietly cuts noise and vibration. And now, as cars turn into rolling computers, that same film is increasingly engineered to support heads-up displays—those floating navigation arrows and speed readouts that appear to hover on the glass.

One company supplies a staggering share of that invisible safety layer. Sekisui Chemical’s High Performance Plastics business makes and sells interlayer films for laminated glass around the world, and it holds roughly half the global automotive market.

That’s the hook: a product nearly everyone uses, made by a company almost no one outside the industry can name.

Sekisui Chemical Co., Ltd. is a diversified Japanese materials company with about $8.5 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue and roughly 27,000 employees. It operates through more than 150 group companies across around 20 countries and regions. In the West, it’s not a consumer brand. But in specialized B2B markets—where qualification cycles are long, quality requirements are unforgiving, and incumbency matters—Sekisui is a quiet force. Alongside interlayer film, it holds leading positions in niches like foam products and conductive particles.

And the story behind those positions is even more interesting than the products themselves.

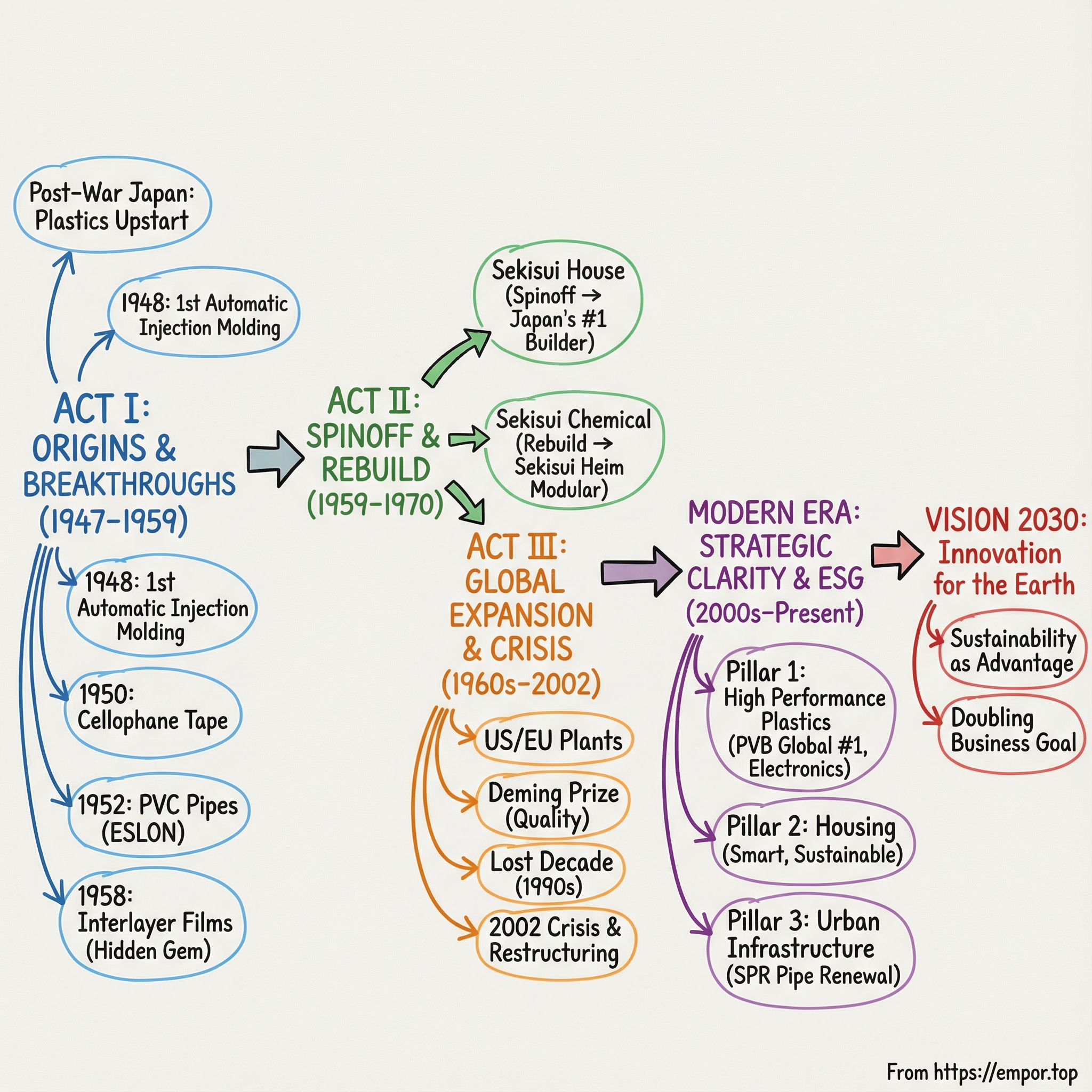

Sekisui begins in the rubble of post-war Japan as a plastics upstart. It becomes a pioneer in modern housing—then spins that business out into what becomes Sekisui House, Japan’s largest homebuilder. That one decision forces the parent company into an identity crisis and, eventually, a reinvention: rebuilding a housing business from scratch while expanding deeper into high-performance materials. Then, during Japan’s lost decade, Sekisui gets pushed to the edge—close enough to failure that it has to choose what it really is. Out of that pressure comes the modern Sekisui: a portfolio of focused businesses built to be number one in narrow global categories, paired with a sustainability posture that, over time, turns into a real advantage.

We’ll tell it in three acts: the post-war origins and early breakthroughs of the 1940s and ’50s; the great spinoff and the long rebuild through the late 20th century; and the modern era—from the 2000s to today—where strategic clarity, global niche dominance, and ESG leadership define the company.

What emerges is a playbook for the Japanese “hidden champion”: not loud, not flashy—just relentlessly good at owning the unglamorous pieces of the world that make everything else work.

II. Post-War Japan and the Birth of Sekisui (1947-1959)

The Ruins and the Opportunity

In the late 1940s, Japan was a country in pieces. Millions were homeless. Millions more—including soldiers returning from the front—needed work. And yet, in the middle of that devastation, the groundwork for a new economy was being poured. Under the Allied occupation and General Douglas MacArthur’s reform program, the old industrial order was broken up. The biggest zaibatsu were dismantled, workers gained new freedoms, and space opened up for new companies to form—and grow fast.

On March 3, 1947, seven founders stepped into that opening and launched Sekisui Inc., the predecessor of today’s Sekisui Chemical. Their mission was straightforward and unusually modern for the time: build a comprehensive plastics business, and use plastics to make everyday life better.

Plastics were still young as an industrial material, but the founders saw what they could become. Japan needed affordable goods, reliable materials, and scalable manufacturing—exactly the kind of environment where a new material platform could take off.

Japan's First: The Automatic Injection Molding Breakthrough

Sekisui didn’t ease into it. Within a year, it was moving at the pace of a company trying to define an industry, not just participate in one. In 1948, it set up plants in Nara and Osaka—and at the Nara plant, it installed Japan’s first automatic plastic injection molding machine.

That milestone mattered for more than bragging rights. It signaled something deeper: Sekisui intended to lead through manufacturing capability and process know-how. In a rebuilding nation starved for everyday products, being able to produce plastic goods at industrial scale wasn’t just a technical win—it was a strategic foothold.

Cellophane Tape and the Practical Innovation Philosophy

One of Sekisui’s earliest “aha” moments came from something almost trivial: envelope tape.

After the war, the company noticed the adhesive tape used on envelopes brought by the U.S. occupation forces. Sekisui’s engineers didn’t treat it as a novelty. They treated it as a clue. They began R&D, and before long, Sekisui achieved practical commercialization—creating Japan’s first cellophane adhesive tape in 1950.

This would become a recurring Sekisui pattern: spot a real-world need, learn from what already works, then engineer a domestic version that can be produced reliably and at scale.

PVC Pipes: Building Japan's Infrastructure

Then came the products that didn’t just serve households—they helped rebuild the country.

In August 1952, Sekisui began full-scale production of rigid PVC pipe under the ESLON brand. These pipes became foundational for modern infrastructure, supporting the delivery of essential services like gas, water, and electricity. Compared with metal, PVC offered durability and corrosion resistance—exactly what you want when you’re laying pipe that should last for decades.

ESLON would go on to become a household name in Japan’s construction and utilities world, effectively shorthand for plastic piping. And the timing couldn’t have been better: Japan’s reconstruction demanded massive infrastructure investment, and Sekisui was positioned with a material solution ready to roll out.

Public Markets and Growing Recognition

By the mid-1950s, Sekisui had enough momentum to do something many industrial companies still hesitated to do: step into public markets. The company listed on the Osaka and Tokyo stock exchanges in 1953 and 1954, opening access to capital for expansion—and taking on the discipline and visibility that came with being public.

Interlayer Films: The Crown Jewel Emerges

The most important seed of this era, though, wasn’t the most obvious one at the time.

In 1958, Sekisui began producing interlayer films—the thin material sandwiched between sheets of laminated glass. It’s what keeps a windshield from turning into a cloud of shards. It also helps with sound insulation, UV protection, and, in today’s cars, enabling advanced features in the glass itself.

Back then, it was just another promising product line in a young plastics company. But that quiet start became the crown jewel. From that 1958 launch, the business grew steadily into what it is today: a global leader in interlayer films, ultimately reaching the world’s top share and becoming central to Sekisui’s modern identity.

By the end of the 1950s, Sekisui had already shown the DNA that would define it for decades: move early, build real manufacturing advantages, solve practical problems, and tie growth to long-lived demand—whether that’s infrastructure, housing, or safety-critical components in vehicles.

III. The Prefabricated Housing Revolution and the Great Spinoff (1959-1970)

Japan's Housing Crisis Creates Opportunity

By the end of the 1950s, Japan’s rebuild had run into a very human bottleneck: there simply weren’t enough homes. The country was urbanizing fast, and traditional construction—carpenters measuring and cutting timber piece by piece on site—was too slow to meet demand at scale.

At the same time, Sekisui was already selling into construction and industry. So when prefabricated housing started to take hold—building components in a factory, then assembling them at the site—it wasn’t a leap into a new world. It was an extension of what Sekisui already believed: if you can industrialize production, you can make quality consistent, costs predictable, and growth possible.

Sekisui’s engineers went looking for inspiration anywhere they could find it. In the early 1960s, one of them visited Disneyland in California, partly to see Monsanto’s plastic “house of the future.” He came back hoping to create a similar concept in Japan. The early attempts didn’t land. Like many first-generation prefab homes, the prototypes lacked the warmth and comfort people associated with a “real” house. As a company spokesperson told Fortune in 1983: “The houses were cheap looking, and people weren’t interested.”

Pivoting to Steel-Frame Success

Sekisui didn’t drop the idea. It iterated.

By improving its designs—adding fiberboard and aluminum panels set into steel frames—the homes started to feel less like experiments and more like products. And then came the pivotal structural move: in 1960, Sekisui set up its housing business as an independent company, Sekisui House Industry, focused primarily on steel-frame housing. In 1961, Sekisui House opened a plant in Shiga and began marketing its Type B, a one-story prefab home.

The spinoff wasn’t a footnote. It was a fork in the road. Sekisui Chemical had taken a business with massive potential and, rather than keeping it as a core internal division, pushed it out into its own company. The next year, that company took the name it still carries today: Sekisui House.

The Great Spinoff: Counter-Intuitive Brilliance or Strategic Error?

In hindsight, this is the kind of decision that makes business historians argue for decades.

Sekisui Chemical’s original housing division became Sekisui House. And Sekisui House went on to become Japan’s largest homebuilder—celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2020, and noting that over those decades it had provided more than 2.7 million homes to customers in Japan and globally.

But that success created an uncomfortable question for Sekisui Chemical: if housing was going to be that valuable, why did the parent let it go?

Part of the answer lies in the corporate philosophy of the era. Spinning off a venture could give it freedom to move faster, hire and invest more directly, and build its own culture—while still benefiting from the broader group’s support. The logic was coherent. The consequences were enormous.

And then, almost as a plot twist, Sekisui Chemical made its next move: about a decade after the spinoff, it decided it wasn’t done with housing after all. It created a new housing division—the business that would become Sekisui Heim.

The Birth of Sekisui Heim: Rebuilding from Within

Sekisui Chemical’s comeback in housing wasn’t a quiet, incremental re-entry. It was a rebuild from scratch—and it leaned hard into what Sekisui did best: factory production.

SEKISUI HEIM was designed around unit production, aiming for high efficiency and consistent quality. The company emphasized that this approach delivered high functionality and strong cost performance—right as Japan’s housing market was rapidly shifting toward low-cost, high-quality options. Heim debuted publicly at the 1970 International Good Living Show in Tokyo. Sales began the following year, and by 1974 the business had accumulated more than 10,000 orders. Within three years of launch, SEKISUI HEIM had joined the ranks of major prefab house manufacturers.

Heim also represented a shift in what “prefab” meant. In the early 1970s, the “unit house” entered the market as a new form of prefabricated housing: enclosed in steel frames, using concrete and metal in walls and ceilings, and produced on an assembly line in room-sized segments.

The results were striking. In 1971, Sekisui erected 260 unit homes under the Sekisui Heim name. Each could be assembled in a matter of hours. By 1973, the Musashi and Nara plants were each producing 2,000 unit homes per month.

Innovation During Adversity

This all happened while the company was absorbing real economic pressure. In 1965, Sekisui faced reduced income and omitted dividends after aggressive capital investment collided with a market downturn. Instead of retreating, the company widened its bets in ways that would matter long-term: it launched the Softlon foam business in 1968 and announced the SEKISUI HEIM modular house in 1970.

Looking back, the 1959–1970 period is the moment Sekisui’s modern character starts to show. The Sekisui House spinoff can look, from one angle, like giving away the crown jewels. But Sekisui Chemical’s ability to build a second housing franchise—successfully—demonstrates something harder to quantify and more durable: organizational resilience. Over the last five decades, Sekisui has built 550,000 units in Japan, proving that Heim wasn’t a consolation prize. It became a major force in its own right.

IV. International Expansion and the Interlayer Film Breakthrough (1960s-1990s)

First to America: A Japanese Manufacturing Pioneer

With Heim taking off at home, Sekisui was already doing something else that, for a Japanese industrial company in the early ’60s, was borderline audacious: it went global.

In 1963, Sekisui established Sekisui Plastics Corporation (SPC) in Pennsylvania to manufacture expandable polystyrene paper. It was the first Japanese manufacturing company to set up a production site in the United States. That’s a bigger statement than it sounds like today. This was still an era when most Japanese firms were intensely domestic, building capability at home before thinking about factories abroad.

And Sekisui didn’t stop with one bet. In 1962, it formed Sekisui Chemical GmbH in Düsseldorf. In 1963, it established Sekisui Products, Inc. in New Jersey. That same year, it opened Sekisui Malaysia Company. Country by country, it started laying down a map that looked less like “exports” and more like “we’re going to manufacture wherever the demand is.”

The Interlayer Film Empire Takes Shape

All the while, one product line kept compounding quietly in the background: interlayer film.

Through the 1960s and ’70s, Sekisui’s film business grew steadily, serving automotive and architectural glass manufacturers. No consumer brand. No splashy marketing. Just a safety-critical material sold to customers who cared about one thing above all else: consistency.

Over time, that kind of market builds a very particular advantage. You accumulate process know-how. You learn how to run lines without variation. You earn trust, then deepen relationships because qualification and re-qualification are painful.

And Sekisui kept expanding its footprint to match. Its Mexico plant began operation in 1971, and it became the company’s second-oldest plant for laminated glass interlayer films. That early presence gave Sekisui a durable base in the Americas long before “global supply chain strategy” was a boardroom buzzword.

The Deming Prize: Quality as Competitive Weapon

In 1979, Sekisui Chemical received Japan’s prestigious Deming Prize for quality control.

The Deming Prize isn’t a participation trophy. It’s recognition that a company has embedded quality management into the way it operates—statistical process control, continuous improvement, defect prevention—the whole system. And for interlayer film, those capabilities weren’t nice-to-haves. They were the business.

A defect in windshield film isn’t like a blemish in a disposable package. This is the layer that’s supposed to hold glass together when a car crashes. Automotive customers demanded extraordinary consistency, and Sekisui was building a culture and a manufacturing engine designed to deliver it, year after year.

Computer-Aided Design Transforms Housing

Sekisui’s “factory mindset” wasn’t limited to chemicals and films. In the 1980s, computer-aided design started reshaping the housing business, too.

Customers could sit with a Sekisui sales representative at a computer terminal, start from a standard model, and then modify it—add rooms, expand spaces, adjust layouts—right on the screen. Once the design was set, the order went to a regional factory, where highly automated facilities produced the components. Assembly on-site could happen in a matter of hours.

The underlying idea was simple and powerful: run housing more like an automobile plant. Use assembly lines. Move modules through defined stages. Standardize what can be standardized—then customize at the edges.

By the time you get to the 1990s, you can see what Sekisui had really been doing for three decades. It wasn’t chasing headlines. It was building capability—overseas footholds, manufacturing discipline, and hard-won credibility in markets where customers don’t forgive mistakes. And that patient accumulation set the stage for what came next, when Japan’s economy—and Sekisui itself—hit a wall.

V. The Lost Decade and Corporate Crisis (1990s-2002)

Japan's Bubble Bursts

When Japan’s asset bubble burst in the early 1990s, the aftershocks rippled through everything that depended on confidence and big-ticket spending—especially housing. Demand sagged, then stayed down. For Sekisui, which still had meaningful exposure to prefabricated homes, it was the kind of slow-moving macro disaster that doesn’t break you in a quarter. It breaks you over a decade.

By 1998, the pain showed up clearly: a weak housing market pushed Sekisui into a loss. And that loss wasn’t a one-off. The company had enjoyed relative strength earlier in the decade, but by the late ’90s the housing slowdown forced a hard reset. Sekisui rethought what its prefabricated division should even be in a more mature, slower-growing market, and it moved into restructuring mode—refocusing on core operations and shutting down parts of its steel- and wood-based businesses.

Consumer spending stayed weak. Housing development stayed sluggish. And Sekisui’s results reflected it. From 1998 through 2002, the company reported losses.

The Nadir: 2002's Massive Loss

Then came the bottom.

In 2002, after continuing to restructure, Sekisui reported a net loss of ¥52.11 billion—less a single bad year than the moment when years of pressure, write-downs, and difficult decisions finally hit the financial statements all at once.

This was also when the existential questions stopped being abstract. Was prefabricated housing still viable in a mature, declining environment? And with Sekisui House long gone as an independent giant, what exactly was Sekisui Chemical’s identity supposed to be?

Internally, the company described 2001 as the start of an urgent phase: it launched a new company organization system alongside emergency management measures, pushed restructuring, reduced fixed costs and production scale, and implemented an early retirement program.

The Divisional Company Restructuring

Out of the crisis came something Sekisui didn’t have before: enforced clarity.

The company implemented a Divisional Company Organization System, and its operations were reorganized and renamed into three business divisions: the Housing Company, the Urban Infrastructure & Environmental Products Company, and the High Performance Plastics Company.

This wasn’t just boxes on an org chart. It was a strategic redesign. Each division now carried its own profit-and-loss accountability, which meant underperformance could no longer hide inside the overall company. Managers had to face, directly, what was creating value and what was draining it. The goal was focus: exit the weakest areas, protect what was working, and double down on segments where Sekisui could realistically be the best.

Within that structure, each division pushed to sharpen its competitiveness around the company’s emerging direction. In housing, for instance, one theme was environmental performance—offering “zero utility expense” houses equipped with photovoltaic generators.

For anyone looking at Sekisui’s arc, the 1998–2002 period is the crucible. It shows how exposed even disciplined companies can be to macroeconomic collapse. But it also shows what crises can do that good times rarely allow: they force choices. The Sekisui that came out the other side was leaner, more transparent, and far more deliberate about what it wanted to be—and that set up the next era of the company’s strategy.

VI. The Strategic Renaissance: Three Pillars and Global Niche Dominance (2000s-2015)

Strategic Clarity Emerges

After the near-death experience of the early 2000s, Sekisui’s strategy stopped trying to be everything to everyone. It hardened into a simple, almost ruthless idea: pick the right narrow markets, then become number one in them—globally.

The portfolio naturally split into two worlds. On the B2C side, Sekisui stayed in new housing construction. On the B2B side, it doubled down on the kinds of products most people never notice, but whole industries depend on: conductive fine particles, interlayer films for automotive laminated glass, water and sewer pipes, and diagnostic reagents.

The niches Sekisui targeted tended to share the same DNA. Customers faced high switching costs. The technical requirements were specialized. Competition was fragmented. And demand was often pulled forward by forces bigger than any one company—regulation, safety standards, and Japan’s demographics and aging infrastructure.

Interlayer Films: Global Dominance Consolidates

Interlayer film became the flagship of this new Sekisui.

Building on decades of steady improvement—especially for automotive applications—Sekisui grew the business under the S-LEC™ brand into the world’s leading position. And it didn’t try to serve a global customer base from a single “super-plant” back in Japan. It built a footprint that matched how automakers actually buy: close to their factories, with local supply and local support.

By this period, Sekisui had six production bases for the business—Japan, China, Thailand, the Netherlands, the U.S., and Mexico—supported by a network of sales bases around the world.

That’s “local production for local consumption” in practice. For automotive supply chains, it’s not a slogan. OEMs want just-in-time delivery, quick response on quality, and engineers who can sit across the table when something changes. For safety-critical components, shipping from far away and hoping for the best isn’t a strategy.

Medical Diagnostics: The Daiichi Acquisition

Then Sekisui made a move that, on the surface, looks like a left turn from windshields and pipes: healthcare.

In 2008, Sekisui merged its Medical Products Division with Daiichi Pure Chemicals to form the core company of its life sciences business. Daiichi Pure Chemicals brought a portfolio that included clinical test agents, research reagents, fine chemicals, and pharmacokinetic testing, with sales steadily expanding.

Strategically, the deal did two things at once. It reduced Sekisui’s dependence on cyclical end markets like housing and autos. And it let the company apply what it already knew—materials science, polymer chemistry, and manufacturing discipline—to a field where reliability and quality control matter just as much, if not more.

Infrastructure Renewal: The SPR Method

The third pillar wasn’t about building new infrastructure. It was about saving the infrastructure that already existed.

Sekisui moved quickly to address Japan’s aging sewage systems—much of which had been installed during the post-war boom and was now hitting the end of its designed life. One of the company’s key answers was the SPR method, a trenchless rehabilitation approach that restores old pipes to a durable, like-new level without digging up streets—and while maintaining sewage flow during installation.

Instead of a disruptive dig-and-replace project, the Spiral Wound process uses a mechanically wound PVC liner to create a fully structural renewal inside the existing pipe. The payoff is obvious to anyone who’s lived through roadwork: far less excavation, lower cost, and dramatically less disruption for communities.

By the mid-2010s, the throughline was clear. Sekisui had turned a crisis-era restructuring into a real operating philosophy: three pillars with clear accountability, leadership positions in global niches, and a set of businesses that were less exposed to any single economic cycle. Interlayer films anchored global scale. Medical diagnostics added a new engine. And infrastructure renewal positioned Sekisui to benefit from a maintenance wave that wasn’t going away anytime soon.

VII. Modern Transformation: Vision 2030 and the Sustainability Pivot (2015-Present)

New Leadership Takes the Helm

In March 2020, Sekisui appointed Keita Kato as President and CEO. It was not a gentle moment to take the wheel. COVID-19 was about to throw global supply chains into chaos and rattle construction markets worldwide.

But Kato wasn’t coming in cold. He had previously led Sekisui’s High Performance Plastics Company—the part of the portfolio where “quality can’t slip” isn’t a slogan, it’s the product. That background mattered, because the next phase for Sekisui wasn’t about a flashy reinvention. It was about disciplined execution: invest, globalize, and make sustainability a competitive edge rather than a nice-to-have.

Vision 2030: Doubling the Business

Sekisui’s long-term plan is called Vision 2030, running through fiscal 2030. The company framed it around a simple premise: social challenges are accelerating—climate, infrastructure, health, mobility—and the winners will be the companies that can innovate through that change, not just endure it.

The vision statement is “Innovation for the Earth.” It’s meant to capture what Sekisui wants to be known for: supporting life infrastructure and creating “peace of mind that continues into the future” by delivering products and services that improve sustainability.

The ambition is big. Sekisui set a target of ¥2 trillion in sales and an operating income ratio of 10% or higher by fiscal 2030, with ESG management positioned not as a side initiative, but as the organizing principle for growth, reform, and new business creation.

Drive 2.0: Accelerating Strategic Innovation

To turn that long-term vision into something operational, Sekisui put forward a medium-term management plan called Drive 2.0. It’s described as the second phase of Vision 2030, built around two themes: “Sustainable Growth” and “Accelerate Strategic Innovation.” The plan spans a three-year window from fiscal 2023 to fiscal 2025 and covers the full Sekisui group.

What stands out isn’t the phrasing—it’s the posture. Sekisui expanded its investment capacity materially, setting an overall investment limit of ¥500 billion. Within that, strategic investment rose to ¥400 billion, more than double the previous mid-term plan, and the cap earmarked for M&A was set at ¥300 billion.

In other words: Sekisui wasn’t just promising innovation. It was reserving the capital to buy capabilities, secure know-how, and expand global sales channels when the right opportunities appeared.

Sustainability as Competitive Advantage

This is also the era when Sekisui’s sustainability story stopped sounding like corporate messaging and started reading like a track record.

The company has been included in the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) World Index for 13 consecutive years. It has also been recognized by CDP for corporate transparency and performance on climate change and water security, earning a place on CDP’s ‘A List’ with a double ‘A’ score based on the 2023 Climate Change and Water Security questionnaires—an outcome achieved by only a small number of companies out of the more than 21,000 scored.

Sekisui paired that recognition with clear targets: zero greenhouse gas emissions from its business activities by 2050, and a 50% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 versus 2019 levels, aligned with the “1.5℃” target.

The takeaway isn’t that Sekisui found religion. It’s that it’s treating sustainability like it treats quality control: as a system, measured and managed over time, because it lowers risk and strengthens trust with customers, regulators, and communities.

Record Financial Performance Despite Headwinds

Even with that long-term investment push, Sekisui has continued to emphasize financial performance and discipline. On October 30, 2025, the company reported mixed second-quarter results: record-high net sales, but profits that fell short of forecasts amid challenging market conditions.

For the full fiscal year 2025, Sekisui’s revised plan projected net sales of ¥1,323.2 billion and operating profit of ¥110.0 billion—up year over year and aiming for record highs despite a tough environment.

Put it together and the 2015-to-present chapter reads like a mature operator leaning into its strengths. A long-term vision anchored in ESG, real money committed to strategic investment and M&A, and steady execution even when external conditions aren’t cooperating. The company is trying to do what it’s always done—own the unglamorous essentials—just on a bigger, more global, more sustainability-driven stage.

VIII. Key Inflection Points: What Changed Sekisui's Trajectory

Inflection #1: The 2001-2002 Divisional Restructuring

The move to three divisions with real P&L accountability rewired how Sekisui ran the company. Cross-subsidies that once blurred performance largely disappeared. Each business could see, in plain numbers, whether it was earning its keep—and leadership could no longer avoid hard calls by averaging everything together.

Inflection #2: The Daiichi Pure Chemicals Acquisition (2005-2008)

In 2008, Sekisui merged its Medical Products Division with Daiichi Pure Chemicals, creating the core company of Sekisui Chemical’s life sciences business.

This mattered because it wasn’t diversification for diversification’s sake. It pulled Sekisui further away from the housing cycle and into a market where quality, process discipline, and chemistry know-how translate directly into trust—and long-term demand.

Inflection #3: Thai Housing JV with Siam Cement Group (2009)

In September 2009, SCGM and SEKISUI CHEMICAL established SCG-SEKISUI SALES CO., LTD. to manage the sales of modular houses and SEKISUI-SCG INDUSTRY CO., LTD. to handle production of modular houses.

For Sekisui Heim, this was a proving ground: the first real attempt to export its factory-built housing playbook. The question wasn’t “can we sell homes abroad?” It was whether the very Japanese system—controlled factory production, standardized modules, tight quality loops—could survive and win in an emerging-market context.

Inflection #4: European Interlayer Film Capacity Expansion (2015-2018)

Between 2015 and 2018, SEKISUI CHEMICAL decided to expand European production of interlayer film for laminated glass with a new film line at its plant in Roermond, and a new resin line at its plant in Geleen, both in the Netherlands. The total cost of this expansion was approximately 20 billion yen, with operations scheduled to begin on the new film line in the second half of fiscal 2019 and on the new resin line in the first half of fiscal 2020.

This wasn’t just “more capacity.” It was a strategic move to meet growing European demand—especially for higher-function films, including HUD-compatible products—while also strengthening control over a critical input by adding PVB resin production.

Inflection #5: Vision 2030 and ESG Pivot Under New Leadership (2020)

In 2020, the combination of new leadership and Vision 2030 pushed ESG from “important” to foundational. The point wasn’t optics. It was giving the company a coherent way to invest, prioritize, and execute long-term—even as COVID-19 disrupted the short-term operating environment.

Intellectual Property as Moat Defense

Sekisui also treats intellectual property like a strategic asset worth fighting for, not a legal footnote.

On April 17, 2025, SEKISUI CHEMICAL announced it had obtained judgments in its favor from the District Court Munich I in patent infringement litigation against Kuraray Europe GmbH. The judgments found that sound-insulating wedge products manufactured and sold by Kuraray Europe infringed European Patent No. 2017237 and European Patent No. 3208247 owned by SEKISUI CHEMICAL, relating to the sound insulation property of a PVB interlayer.

Sekisui has been explicit about the posture behind that win: it regards intellectual property rights as an important management resource, and it will take strict action when it determines those rights have been infringed.

IX. Business Deep Dive: The Three Pillars

High Performance Plastics Company

This is the engine room of modern Sekisui: the crown jewel interlayer film business, plus electronics materials, foams, and other specialty chemicals.

The interlayer film story is still evolving. As the shift to new energy vehicles accelerates, laminated glass is spreading beyond the windshield to side and roof glass, too. Repairs are also rising. Put that together, and demand for interlayer film is expected to grow to the point where it can outpace the number of cars produced.

What’s driving the next wave isn’t just more glass—it’s more sophisticated glass. Higher value-added interlayer films, like wedge-shaped film for heads-up displays, along with design-oriented films and products that improve sound and heat insulation, are expected to grow at 5% or more annually as automakers push for better safety, comfort, and energy efficiency.

At the same time, Sekisui is leaning into semiconductors. The company has decided to increase production capacity of SELFA®, its high-adhesion, easy-removable UV tape used in advanced semiconductor manufacturing processes, at its Musashi Plant. It is also establishing a new R&D base in Taiwan to strengthen evaluation and analysis capabilities for semiconductor-related materials.

From there, Sekisui plans to widen the footprint: it will consider establishing additional bases in Korea, the U.S., and other countries to expand its electronics-related semiconductor materials business, starting with that Taiwan R&D hub.

Housing Company

Sekisui’s housing business runs on the same principle as its materials businesses: move critical work into the factory, control quality, and build to spec. It uses modular construction—steel-framed and wooden systems—produced in factory settings with comfort, safety, and environmental performance designed in from the start.

Internationally, Thailand is the template. Sekisui has a factory there and plans to develop the Thai market while expanding into neighboring countries.

Back in Japan, the housing pitch is increasingly about energy and intelligence, not just structure. Built around a three-part set—a large-capacity solar generation system, the consulting-style HEMS Smart Heim Navi, and an e-Pocket storage battery—Sekisui offers its “smart energy life,” designed to push both power generation and energy savings to a higher level.

Urban Infrastructure & Environmental Products

This pillar is the “keep the country running” business—and it gets more important as infrastructure ages.

Sekisui provides repair, rehabilitation, and renovation methods for aging systems, especially sewerage. Its approach rehabilitates pipes by lining the inner surface with rigid PVC materials in a spiral shape, extending lifespans without digging up roads. That means shorter construction periods and far less industrial waste, like excavated soil and sand.

It’s also a business with a powerful tailwind: Japan’s aging infrastructure isn’t a short-term cycle. It’s a long-duration, highly visible demand driver likely to extend for decades.

X. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Interlayer film is the kind of business that looks simple until you try to make it. Sekisui has been producing it since 1958, which means the advantage isn’t just technology—it’s decades of accumulated process knowledge. New entrants run into two walls immediately: the need to spend heavily on production lines, and the reality that automotive customers won’t buy anything until it survives years of qualification testing. In a safety-critical component, you don’t get to “move fast and break things.”

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

A lot of chemical feedstocks are relatively commoditized, which normally gives suppliers leverage. Sekisui blunts that by integrating backward into PVB resin production, including at its Netherlands facilities. That reduces reliance on third parties for a key input and improves control over quality and supply.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Automakers are large, concentrated buyers, and they negotiate like it. But they can’t squeeze suppliers the way they might in a non-critical part. Windshield performance is directly tied to safety, and a failure is catastrophic—so “cheapest” is never the only filter. On top of that, switching suppliers is expensive and slow because it requires requalification, which raises the real cost of walking away from an incumbent.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

There’s no practical substitute that does the same job in automotive safety applications. Laminated glass with a PVB interlayer is effectively mandated by regulation, and PVB’s combination of shatter resistance, UV blocking, and noise reduction is hard to replicate with alternatives at scale.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

In practice, the market behaves like a duopoly, with Kuraray as the other heavyweight. And this is not a “gentleman’s competition.” Patent litigation shows both sides treat IP as core territory. Increasingly, the fight is less about price and more about innovation: HUD-compatible films, acoustic films, and heat-blocking products that help automakers differentiate their vehicles.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Sekisui’s global network provides real geographic scale—production close to customers, supported by local operations. Interlayer film isn’t as purely scale-driven as commodity chemicals, but the learning curve advantage compounds when you’ve been running lines for decades.

Network Effects: LOW

These are industrial materials sold into supply chains, not platforms. Network effects don’t really apply.

Counter-Positioning: HIGH

Many traditional chemical companies win by pushing volume in commoditized plastics. Sekisui wins by doing the opposite: specializing in demanding, niche applications that require tight process control, deep application engineering, and close customer collaboration. That’s a difficult pivot for a commodity player to make without disrupting its own economics.

Switching Costs: HIGH

Once an automotive supplier is qualified, it’s “sticky.” OEMs invest years validating materials and processes, and switching introduces risk they don’t want—especially in safety-critical glass. On top of that, products often become customer-specific over time, which creates real dependency.

"We want to continue to play a decisive role in shaping the future of mobility and position ourselves as a trendsetter with innovative solutions for comfort, safety and sustainability in the automotive industry."

Branding: MODERATE

S-LEC is not a consumer brand, but it doesn’t need to be. In engineering-driven B2B markets, brand is shorthand for trust, reliability, and “this will pass qualification.” Within that world, the name matters.

Cornered Resource: HIGH

Sekisui’s edge is partly trapped in the walls: institutional know-how built over 60+ years of R&D and production experience. Its patent portfolio reinforces that advantage, and it has shown it will defend those rights in court when needed.

Process Power: VERY HIGH

The company’s Deming Prize heritage isn’t trivia—it’s evidence of a culture built around manufacturing excellence. And that capability shows up across the portfolio, from high-spec film production to factory-built housing. Sekisui’s superpower is doing the unglamorous work of process discipline, over and over, until it becomes a moat.

XI. Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case

EV Transition Accelerates Interlayer Film Demand

As cars electrify, they’re also turning into bigger glass boxes. Panoramic roofs are becoming common. Side and roof glass are increasingly laminated. And because EVs don’t have engine noise to hide the world outside, automakers lean harder on acoustic insulation—another job for interlayer film. Layer on the spread of heads-up displays, and the amount of high-performance film per vehicle rises. Under those conditions, demand can grow so much that it doesn’t just track car production—it can outgrow it.

Japan Infrastructure Renewal Is Secular Tailwind

Japan’s post-war infrastructure is aging into a once-in-a-generation repair cycle, and sewer systems are right in the blast radius. Sekisui’s SPR method is built for this moment: trenchless rehabilitation that keeps sewage flowing while renewing pipes from the inside. Compared with dig-and-replace, the economics and the community impact are simply better. And because this is about decades of accumulated wear, it’s not a short cycle—it’s a long, steady tailwind.

Semiconductor Materials Provides New Growth Vector

Sekisui’s electronics-related materials have found traction with customers, especially in advanced semiconductors used for AI and high-speed communications, and in power semiconductors for automotive applications. The company expects this market to expand meaningfully through 2030—its own estimate pegs it at roughly $1 trillion by then, about double the size of 2023. If that plays out, it gives Sekisui a second major growth engine alongside interlayer films.

ESG Leadership Creates Competitive Advantages

Sekisui’s sustainability posture isn’t a new marketing layer—it’s a long-running operating system. Thirteen consecutive years in the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices World Index signals consistency and discipline, and it also matters financially: it can broaden the pool of investors who are allowed—or required—to own the stock, while reinforcing trust with customers and regulators.

Underappreciated Outside Japan

For a company with global operations and leadership positions in several niches, Sekisui is still largely invisible to international investors. It’s not Toyota or Sony. That obscurity can be an opportunity: as the global footprint, end-market tailwinds, and niche dominance become more widely understood, the company may get “re-rated” simply by being discovered.

The Bear Case

Japan Housing Demographics Remain Challenging

Japan’s population is shrinking, and that’s the kind of headwind you can’t out-innovate away. Renovation, retrofits, and energy-smart upgrades can soften the impact, but the core reality is that new-build demand faces structural pressure over time.

Automotive OEM Concentration Creates Customer Risk

Interlayer film is a high-stakes, relationship-driven business—and the customer list is concentrated. A handful of global automakers drive a large portion of demand. If Sekisui were to lose a major relationship, the impact on the business could be significant.

Yen Weakness/Strength Creates Translation Volatility

With substantial overseas operations, currency moves flow directly into reported results. Even when the underlying business is steady, exchange rates can make performance look better or worse than it really is—and for non-yen investors, there’s an extra layer of FX risk.

Competition from Kuraray and Potential New Entrants

The barriers to entry in interlayer film are real—qualification cycles, process know-how, and capital requirements. But Kuraray is a formidable rival, and over time Chinese manufacturers may climb the learning curve. As patents expire, parts of the moat could weaken, shifting competition toward execution and innovation.

Energy Cost Exposure

This is still a chemical company, and chemical processing consumes a lot of energy. Japan’s energy costs have remained elevated in the post-Fukushima era. Any additional shocks could compress margins, especially in businesses where pricing can’t immediately reset.

XII. Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Sekisui is executing the strategy we’ve been talking about, there are three signals worth watching.

1. High Performance Plastics Segment Operating Margin

This is the profit engine—and it houses the crown jewels: interlayer films and electronics materials. When the operating margin here moves, it usually isn’t noise. It’s telling you whether Sekisui is maintaining pricing power, shifting the mix toward higher-value products like HUD and acoustic films, and holding its ground in a market where Kuraray is the constant rival.

2. Products to Enhance Sustainability Revenue

Vision 2030 isn’t just a slide deck; Sekisui actually tracks sales from what it defines as “Products to Enhance Sustainability.” The company’s goal is to get that category to over 1 trillion yen in net sales by 2030. The closer it gets, the clearer the proof point that ESG isn’t just reputation management—it’s becoming a measurable growth driver.

3. Overseas Revenue Percentage

Sekisui’s next chapter is, in large part, about becoming meaningfully more global. The company has said it plans to accelerate overseas expansion across its domains and, by fiscal 2030, aims for a roughly even split: one trillion yen of sales in Japan and one trillion yen overseas. Today, overseas revenue is still the smaller share. If that percentage rises steadily, it’s a sign that the historically Japan-centric parts of the portfolio are successfully scaling abroad.

XIII. Regulatory and Risk Considerations

Automotive Safety Regulations

The interlayer film business exists because regulators decided windshields shouldn’t turn into knives in a crash. Laminated glass requirements are, at their core, policy-driven. If those mandates were ever relaxed—unlikely, but not impossible—demand would take a hit.

The flip side is more plausible: safety rules tightening over time. As standards evolve, especially around pedestrian protection and overall vehicle safety, laminated glass could expand beyond the windshield into more vehicle surfaces, pulling more interlayer film into each car.

Environmental Regulations

Not all plastics are viewed equally by regulators, and PVC often attracts scrutiny in certain jurisdictions. That matters because parts of Sekisui’s infrastructure business—like the SPR pipe rehabilitation method—use rigid PVC materials as liners.

If restrictions on PVC production or use were to tighten meaningfully, Sekisui could face higher compliance costs, limits on adoption in some markets, or pressure to redesign materials and processes.

Acquisition Integration Risk

Sekisui set aside up to ¥300 billion for M&A under Drive 2.0, explicitly to buy technology, know-how, and global sales channels. That’s the upside. The risk is that acquisitions don’t integrate cleanly—systems don’t mesh, talent walks out the door, or the expected synergies never show up.

Sekisui’s history in building and combining businesses offers some reassurance. But the bigger the deal, the more unforgiving the integration becomes.

Governance Considerations

Japanese corporate governance has improved a lot in recent years, but it can still feel different from Western norms—especially for international investors used to more aggressive shareholder alignment.

Sekisui has moved in the direction of reform: clearer divisional accountability and steps like adding outside directors. Still, Japan-specific practices—like cross-shareholdings and the broader consensus-driven governance culture—can remain a source of concern, depending on how far and how fast the company continues to evolve.

XIV. Playbook Lessons: What Sekisui Teaches About Hidden Champions

Lesson 1: Niche Dominance Creates Defensible Moats

Sekisui’s roughly 50% share in automotive interlayer films is the cleanest proof of the hidden-champion playbook. Pick something specific, unglamorous, and mission-critical—then get so good at it that the market stops feeling competitive. To most people, “film inside a windshield” doesn’t even register as a product category. To automakers and glass makers, it’s safety, quality, and trust—and once you’re qualified, you don’t casually switch.

Lesson 2: Crisis Catalyzes Transformation

Sekisui didn’t arrive at its modern strategy through a whiteboard exercise. It got there the hard way. The losses from 1998 through 2002 forced the company to stop drifting and start choosing: restructure, assign real divisional accountability, rationalize the portfolio, and focus on the businesses where it could actually win. In calmer times, those calls are easy to postpone. Under pressure, postponement stops being an option.

Lesson 3: B2B Businesses Can Sustain Premium Returns

Consumer brands get the spotlight, but Sekisui is a reminder that the best businesses often live upstream, inside supply chains. Specialty B2B materials can earn premium returns for reasons that don’t show up in a billboard: switching costs, process know-how that’s accumulated over decades, and deep customer intimacy built through co-development and qualification. When your product is safety-critical, “good enough” isn’t good enough—and consistency becomes pricing power.

Lesson 4: ESG Leadership Reflects Operational Excellence

Sekisui’s sustainability standing reads less like a marketing campaign and more like an operating capability. The companies that score highly over long periods tend to be the ones that can measure what matters, manage long horizons, and coordinate across stakeholders without losing focus. In other words, the same organizational muscles that win Deming Prizes and run tight factories also show up in credible climate and water performance.

Lesson 5: Japanese "Hidden Champions" Merit International Attention

Sekisui isn’t an outlier in Japan—it’s an example. The country is full of firms that lead the world in narrow categories most outsiders never think to look for. They’re often unknown to Western investors, yet they can combine exactly the traits long-term, value-oriented investors care about: defensible niches, conservative financial posture, and multi-decade execution. The opportunity is simple: sometimes the best global businesses aren’t the loudest ones.

XV. The Investment Verdict

Sekisui Chemical is the Japanese hidden champion in its purest form: world-class in narrow, unglamorous niches; quietly diversified across multiple end markets; and run with the kind of manufacturing discipline that turns “boring” into durable.

At the center sits the interlayer film franchise. It’s hard to overstate how good this business is when it’s run well: roughly half the global automotive market, deep process know-how built over decades, and switching costs that are structural, not marketing-driven. And the tailwinds are real. As EVs push designs toward more glass, better acoustics, and features like heads-up displays, the amount of sophisticated film per vehicle tends to rise.

Around that core, Sekisui has built ballast. Housing offers a platform for smart, energy-oriented homes. Urban infrastructure rehabilitation is positioned for the slow, unavoidable reality of aging pipes. Medical diagnostics adds a different demand curve—less cyclical, more driven by long-term healthcare needs. The mix won’t make Sekisui feel like a pure-play on any one theme, but that’s the point: it’s a portfolio designed to keep compounding through cycles.

The risks aren’t trivial. Japan’s demographic headwinds weigh on housing. Automotive customers are concentrated, and that concentrates relationship and execution risk. Currency moves can distort reported results even when operations are steady. But these are the kinds of risks you can model, manage, and watch—not existential flaws.

Vision 2030 gives investors a clean scorecard: ambitious growth goals, a push toward higher profitability, and a willingness to invest heavily—including through M&A—to secure technology and global reach. Whether Sekisui hits every target is less important than whether the direction is consistent: more global, more specialized, and more weighted toward businesses where quality and trust create pricing power.

For investors who want exposure to Japanese manufacturing excellence, the EV supply chain, infrastructure renewal, and credible sustainability leadership—without paying the “famous brand” premium—Sekisui Chemical deserves a serious look.

That invisible layer between your eyes and the road ahead will stay invisible. The company behind it doesn’t have to.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music