Mitsubishi Chemical Group: From Zaibatsu Ashes to Green Specialty Pivot

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

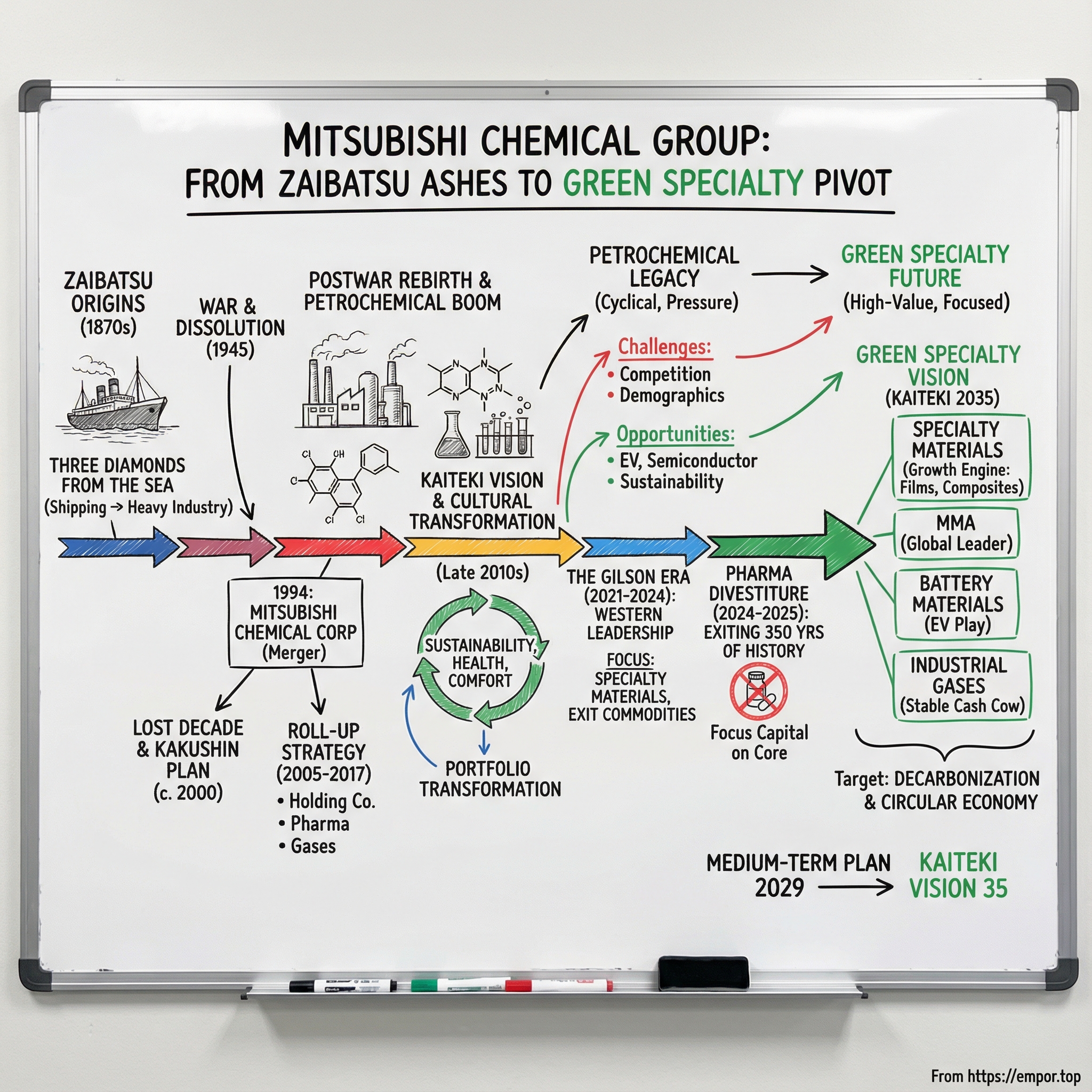

Picture a Belgian executive walking into a Tokyo boardroom in April 2021 and taking the top job at Japan’s largest chemical company. Not a startup. Not a turnaround boutique. A Mitsubishi descendant: an industrial empire whose lineage runs from steamships to wartime manufacturing to the postwar petrochemical boom. His name was Jean-Marc Gilson—and in a country where CEOs are almost always homegrown, he was a genuine outlier: the first foreign-born chief executive of Japan’s largest chemical company. He arrived with a mandate that sounded simple and was anything but: take a 150-year-old institution built on scale and tradition, and reshape it into a faster, more focused, sustainability-led specialty materials company. Three years later, he was gone. The transformation, however, was still very much in motion.

That’s the tension at the heart of Mitsubishi Chemical Group today. It’s big, it’s complicated, and it sits right on the fault line of where the chemicals industry is headed. On one side: commodity petrochemicals—grinding, cyclical businesses facing intense cost pressure and increasingly tough competition, especially from China. On the other: high-value specialty materials—things customers will pay a premium for because they enable the next wave of products, from electric vehicles to semiconductors to better, more sustainable packaging.

The group operates across four core segments. Functional Products makes and sells plastic films and resins. Chemicals produces staples like polyethylene, terephthalic acid, and methyl methacrylate monomers. Industrial Gases supplies the gases that underpin modern manufacturing. And Health Care—its most storied and emotionally loaded business—connects the group to a pharmaceutical heritage that stretches back centuries.

In November 2024, the company put a flag in the ground: KAITEKI Vision 35, paired with its Medium-Term Management Plan 2029. The message was clear. By 2035, it doesn’t want to be a sprawling conglomerate trying to do a bit of everything. It wants to be, in its own words, “Solving social problems and delivering impressive results to customers with the power of materials as a Green Specialty Company.”

So here’s the question that will drive this story: how does a conglomerate born from postwar wreckage—and built up through decades of petrochemical scale and pharmaceutical ambition—actually pull off a shift to focused, high-performance, sustainability-forward materials, at the same time it faces petrochemical decline and prepares to unwind major pieces of its portfolio?

The answer isn’t a single product breakthrough or one heroic CEO. It’s a long chain of reinventions: cultural change inside a Japanese icon, hard decisions about what to keep and what to sell, and a bet that the future profit pool in chemicals won’t come from making more—it’ll come from making smarter.

II. The Mitsubishi Origin Story: Three Diamonds from the Sea

Mitsubishi starts, fittingly, with ships.

In 1870, Yataro Iwasaki launched a small shipping firm with three aging steamships. That modest beginning matters because it set the pattern for everything that came after: take one essential capability, then build the adjacent pieces around it until you’ve constructed an entire industrial ecosystem. After Yataro, it would be his brother, then his son, then his nephew who expanded the business into new fields and helped form what we now think of as the Mitsubishi companies.

But before there was an empire, there was a very improbable founder. Iwasaki Yatarō (1835–1885) wasn’t born into boardrooms. He came from Aki in Tosa Province (today’s Kōchi Prefecture), and while his family had roots in the samurai class, that status had been sold off generations earlier to cover debts during the Great Tenmei famine. His rise wasn’t inevitable—it was scraped together through setbacks, ambition, and a talent for turning relationships into leverage.

At nineteen, Iwasaki left for Edo to study. A year later, his education was derailed when his father was badly injured in a dispute with the village headman. Iwasaki pushed the case, accused a local magistrate of corruption for refusing to hear it, and ended up in prison for seven months. When he got out, he drifted through short stints—including tutoring—before returning to Edo, where he mixed with political activists and studied under Yoshida Tōyō, a reformist voice from Tosa who believed Japan’s future depended on modernization, industry, and foreign trade.

That mentorship turned into an on-ramp. Through Yoshida, Iwasaki found work as a clerk for the Yamauchi government—the ruling house of the Tosa Domain—and eventually earned enough standing to buy back his family’s samurai status. It’s an early preview of what he would do for the rest of his life: move upward by mastering institutions, not just markets.

Even the name “Mitsubishi” is a compact origin myth. In 1873, the business was renamed Mitsubishi Shokai. The word combines mitsu, meaning “three,” with hishi, a water caltrop that became shorthand for a rhombus shape. Put together, it’s often rendered as “three diamonds”—the logo that still sits on everything from ships to chemicals.

What made Mitsubishi different wasn’t that it diversified. It’s how it diversified. Mitsubishi began with shipping, and then systematically pulled upstream and downstream into whatever the shipping business needed. Coal-mining to fuel the ships. A shipyard to repair them. An iron mill to supply materials. Marine insurance to reduce risk and keep profits in-house. It wasn’t random expansion—it was vertical integration before the phrase existed.

The company’s ties to the Japanese government reinforced that flywheel. From 1874 to 1875, Iwasaki was contracted to transport soldiers and war materials. The government purchased ships for the 1874 expedition to Taiwan, and after the campaign those ships were transferred to Mitsubishi. The relationship deepened: Mitsubishi supported the new government and transported troops during the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877. Mitsubishi’s ascent, in other words, ran alongside the rise of the modern Japanese state.

Iwasaki died of stomach cancer in 1885, just 50 years old. Leadership passed first to his brother Yanosuke, then later to his son Hisaya. But the logic of the enterprise—the instinct to keep expanding the system—only accelerated. In 1881, the company entered coal mining by acquiring the Takashima Mine, later adding Hashima Island in 1890, using production to power its steamship fleet. Over time, Mitsubishi diversified into shipbuilding, banking, insurance, warehousing, and trade, and eventually into paper, steel, glass, electrical equipment, aircraft, oil, and real estate. This is how a shipping firm becomes a conglomerate: not by making a single big leap, but by relentlessly filling in the map around its core.

And this is where chemicals enter the story—not as a sudden pivot, but as a byproduct of heavy industry. Mitsubishi’s coal operations fed coking factories that supported steelmaking, and those coking processes produced chemical byproducts. Those byproducts became feedstock. Feedstock became products. Products became a business. Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation was founded on August 31, 1933.

This origin story isn’t trivia. It’s the company’s operating system. The same instincts that built Mitsubishi—vertical integration, adjacency expansion, deep institutional relationships, patient capital—still echo inside Mitsubishi Chemical Group today. And that’s the dilemma. The DNA that made Mitsubishi unstoppable in the age of industrial buildout can become friction in an era that rewards focus, speed, and sustainability. The rest of this story is, in many ways, the company trying to evolve without losing what made it Mitsubishi in the first place.

III. War, Dissolution, and Rebirth: The Zaibatsu's Second Life

The zaibatsu system that helped industrialize Japan also became tangled up in Japan’s military expansion. Mitsubishi’s shipyards built warships. Its aircraft factories turned out the Zero fighter. And its chemical operations supplied the materials that modern war consumes at industrial scale. So when Japan surrendered in August 1945, the American occupation authorities didn’t just see a defeated country. They saw a set of institutions they believed had made the war possible—and they wanted to break them apart.

On October 20, 1945, barely two months after the surrender, the Allied Command ordered the disbanding of the zaibatsu, Japan’s industrial and financial conglomerates. The rationale was straightforward: the occupation viewed the zaibatsu, alongside the military, as ultimately responsible for pushing Japan into war—and as economic powers with an unhealthy, monopoly-like grip on the country. For the people inside these companies, it felt like a sweeping judgment on decades of work. Mitsubishi, in particular, had become a symbol of the old system, and symbols are easy to target.

Koyata Iwasaki—Yataro’s nephew and Mitsubishi’s fourth president—didn’t go quietly. He publicly defended Mitsubishi, insisting the group had long-standing relationships with business partners around the world and that it had done what it believed was necessary for the country. But the decision had been made. Under the occupation’s policy, Mitsubishi as a group was dissolved, and major operating companies were broken into smaller pieces. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi Chemical were each split into three separate entities.

The intent was to weaken Japan’s economic base, much as the Allies initially aimed to do in Germany: reduce the capacity to mobilize industry for war. And for a time, that was the direction of travel. On his deathbed, Koyata Iwasaki maintained he had done his utmost for his country and had nothing to be ashamed of. His cousin Hisaya Iwasaki, president of Mitsubishi Partnership Company at the time, was blunter about the outcome: the company, he said, had been stripped bare.

Then geopolitics changed the plan.

As the Cold War intensified—China’s communist revolution in 1949, then the Korean War in 1950—American priorities shifted. The overriding goal became rebuilding Japan into a stable industrial partner and a bulwark against communist expansion. The harshest edges of the dissolution policy were quietly relaxed. And the former Mitsubishi companies began to do what Mitsubishi companies have always done: find ways to reconnect.

A strange, very modern-sounding episode helped speed that along. In 1952, two men with close ties to the yakuza tried to take control of Yowa Real Estate by buying up shares—taking advantage of a gap between the company’s market value and the value of the real estate it held. They greenmailed, forcing other Mitsubishi-linked companies to buy the shares back at an inflated price. The lesson landed hard: fragmented ownership made even valuable assets vulnerable. Coordination wasn’t just a nice-to-have. It was defense.

In 1954, Mitsubishi Corporation was reformed. Around the same time, the Mitsubishi Friday Club was created—a regular forum for the chairpersons and presidents of major Mitsubishi companies to share information and maintain relationships. By 1964, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries also reemerged. Importantly, this wasn’t a resurrection of the old zaibatsu with a single Mitsubishi headquarters calling the shots. The Friday Club symbolized something different: a group of companies that were nominally equal, bound together by ties, trust, and mutual interest rather than by a family-controlled holding company.

By the time the occupation ended in 1952, the shape of Mitsubishi’s second life was becoming clear. The new Mitsubishi grouping wasn’t a centralized empire; it was a keiretsu—informal policy coordination among presidents, plus a degree of financial interdependence across companies. And the broader Mitsubishi Group that exists today sprawls across hundreds of “group companies,” some of which—like Nikon, Kirin Brewery, and Asahi Glass—don’t even carry the Mitsubishi name.

This postwar rebirth created the organizational template Mitsubishi Chemical Group still operates within. The Friday Club style of coordination—informal, consensus-driven, relationship-based—became both a strength and a constraint. It helped Mitsubishi rebuild quickly during Japan’s economic miracle. But it also baked in an instinct to preserve the whole, to move carefully, and to avoid abrupt breakups. Decades later, that same instinct would collide head-on with the kind of portfolio pruning and cultural change executives like Jean-Marc Gilson would try to force through.

IV. The Modern Chemical Company Takes Shape (1950s–1990s)

Japan’s postwar boom rewired the entire country. From the 1950s through the end of the 1980s, Japan surged from rubble to industrial superpower—and chemicals sat right in the middle of that story. As factories multiplied and consumer products flooded the market, demand for plastics, synthetic fibers, and industrial materials exploded. Mitsubishi’s chemical operations didn’t just benefit from that wave; they scaled with it, building out petrochemical capacity to supply an economy that couldn’t get enough material.

Out of that era, two core players emerged inside the broader Mitsubishi universe—separate companies at first, but clearly on a collision course.

One was Mitsubishi Kasei Corporation. Its roots went back to the 1930s, and it reentered public markets in June 1950 with a Tokyo Stock Exchange listing—an early marker of how quickly Japan’s industrial base was being rebuilt and recapitalized.

The other was Mitsubishi Petrochemical Co., Ltd., established in April 1956 as a joint venture built for a new reality: chemistry was shifting from coal-derived feedstocks toward petroleum. If the prewar chemical business had grown out of heavy industry and coking byproducts, the postwar future was oil—bigger plants, cheaper inputs, and far more plastic in everything.

Then, in the 1980s, Mitsubishi began adding a different kind of bet to the portfolio: pharmaceuticals. The 1985 acquisition of Mitsubishi Yuka Pharmaceutical brought real capabilities in cardiovascular treatments, including beta-blockers and antihypertensives. It was the start of a pharma footprint that would eventually grow into a meaningful piece of the group before being divested decades later.

The big structural moment arrived in October 1994. Mitsubishi Kasei and Mitsubishi Petrochemical merged to form Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation—instantly positioning it as Japan’s largest chemical concern. Strategically, it was a classic move for the time: combine upstream petrochemicals with downstream specialty products, tighten the links between feedstock and finished materials, and build the kind of vertically integrated platform that Japanese industrial companies believed would be strongest over the long haul.

And even before that merger, Mitsubishi was already pushing outward. In the early 1990s, it established Kasei Virginia Corporation in the United States to oversee production of high-tech products. That U.S. presence mattered—not just as a flag planted overseas, but as a base that would later help serve American customers in demanding industries like semiconductors and automotive materials.

By the mid-1990s, Mitsubishi Chemical had become exactly what Japan’s high-growth era rewarded: a comprehensive chemical giant spanning performance products, industrial materials, and newer frontiers like electronics and battery-related components. It was a model built for scale and breadth. The only problem was what came next: the macro environment that made that model so powerful was about to change—and Japan’s long stagnation would force Mitsubishi Chemical to start questioning whether “bigger” still meant “better.”

V. INFLECTION POINT #1: The Lost Decade & KAKUSHIN Plan (1999–2005)

Japan’s 1990 asset-bubble crash didn’t just knock the wind out of the economy—it changed the weather for an entire generation. What later got labeled the “Lost Decade” stretched on and on, and chemicals felt it with particular force. Demand at home went flat as growth stalled and demographics turned. Meanwhile, the industry was sitting on too much capacity. And across Asia, competition sharpened: newer, lower-cost plants—especially in China—started pushing into markets Japanese producers had once treated as their backyard.

Mitsubishi Chemical entered the late 1990s staring straight at that reality. In 1999, it launched the KAKUSHIN Plan: a hard-edged restructuring program built around plant consolidations, workforce reductions, and tighter operating discipline, with a target of ¥40 billion in annual cost savings. The rhetoric mattered as much as the math. KAKUSHIN translates to “reform” or “revolution,” and the point was explicit: this couldn’t be another round of small optimizations. The company said it needed a “quantum leap” in management reforms to get profitability back on track.

At the same time, the portfolio was getting cleaned up. Pharmaceuticals—already a distinct kind of business inside a chemical giant—were reorganized in 2001, when Mitsubishi combined its drug operations with Welfide Corporation to form Mitsubishi Pharma Corporation, putting development and sales under a dedicated subsidiary. Then in 2002, Mitsubishi sold its agricultural chemicals business, which brought in about $60 million in annual revenue, to narrow the focus back to its core chemical and pharmaceutical operations.

The biggest move came in 2005, and it wasn’t about a product line—it was about the company’s architecture. On October 1, 2005, Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation and Mitsubishi Pharma Corporation created Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Corporation through a stock-for-stock exchange. The new structure separated the operating companies from a parent designed to think in terms of capital allocation and portfolio strategy.

In practice, that holding company became the platform for everything that followed. It gave Mitsubishi a way to buy, merge, and eventually sell businesses without constantly ripping apart the operating core. The transformation wouldn’t fully show up overnight—but the infrastructure for it was now in place.

VI. INFLECTION POINT #2: The Roll-Up Strategy (2007–2017)

The holding-company structure Mitsubishi put in place in 2005 wasn’t just a governance tweak. It was a deal machine. With a parent company sitting above the operating businesses, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings could start stitching together a broader portfolio—one that reached beyond basic chemicals into plastics, pharmaceuticals, and industrial gases.

In October 2007, Mitsubishi Plastics, Inc. became a wholly owned subsidiary of Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings. That same month, the group made an even more consequential move in healthcare: Mitsubishi Pharma Corporation merged with Tanabe Seiyaku Co., Ltd. to form Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation. The new company was listed, and it came with something Mitsubishi couldn’t manufacture on its own—legacy. Tanabe traced its roots back to 1678, making it one of the world’s oldest continuously operating pharmaceutical businesses.

That Tanabe heritage wasn’t just a historical footnote. Tanabe was headquartered in Doshomachi, Osaka—widely seen as the birthplace of Japan’s pharmaceutical industry. The combination gave Mitsubishi real scale in pharma and a portfolio that included treatments across areas like central nervous system disorders, immunology, and metabolic disease.

Mitsubishi also went shopping for picks-and-shovels in the drug supply chain. In 2012, it acquired the Qualicaps Group for $655 million, expanding into pharmaceutical excipients and hard-capsule manufacturing. The logic was clear: even when blockbuster drug pipelines are unpredictable, the infrastructure that delivers medicines—capsules, coatings, and other delivery systems—can be a steadier business.

Then came the move that pulled Mitsubishi into a different kind of industrial economics entirely: gases. In May 2014, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings announced plans to buy a majority stake in Taiyo Nippon Sanso, pointing to rising U.S. demand for nitrogen and other industrial gases tied to the shale gas boom. By November 2014, Taiyo Nippon Sanso became a consolidated subsidiary.

Taiyo Nippon Sanso sat within a broader holding structure—Nippon Sanso Holdings Corporation—which oversaw a group of companies including the industrial gas business and even Thermos, the stainless-steel thermos manufacturer. As part of Mitsubishi Chemical Group, the gases platform operated across Japan, the United States, Europe, and the Asia-Oceania region, with a footprint spanning more than 30 countries through brands, subsidiaries, and affiliates.

And gases mattered because they behaved differently than petrochemicals. Basic chemicals are global and brutally competitive; gases are local, because shipping them far doesn’t make economic sense. That geography creates regional moats and, typically, steadier cash flows. It also positioned Mitsubishi to benefit from durable demand tied to things like semiconductor manufacturing, healthcare, and food processing.

By 2017, Mitsubishi was ready to simplify some of the sprawl it had created. In April 2017, Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Mitsubishi Plastics, Inc., and Mitsubishi Rayon Co., Ltd. were integrated into a new Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation—bringing performance products, industrial materials, carbon fibers, and basic chemicals back under one roof as Japan’s largest chemical company.

The group also formalized a regional headquarters approach. The idea was to create the organization and infrastructure to actually realize synergies across a global network. Mitsubishi Chemical America and its subsidiaries, for example, brought together decades of operating know-how across industries and technologies, supported by a workforce of more than 4,000 employees across four different countries.

By the end of this roll-up era, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings had built something formidable—and complicated. The portfolio now ranged from polyethylene to pharmaceutical capsules to industrial oxygen. Which raised the uncomfortable question: was this diversification a stronger, balanced platform for the future—or a way to paper over weakening competitiveness in businesses that were getting tougher every year?

VII. INFLECTION POINT #3: The KAITEKI Vision & Cultural Transformation

By the late 2010s, Mitsubishi Chemical was running into a problem that couldn’t be solved with another integration chart or cost-cutting program. Japan’s petrochemical base was aging. Global competition was getting sharper. And the portfolio the group had assembled—impressive as it was—was so broad that it risked becoming a collection of businesses without a single shared direction.

So leadership tried to do something harder than another reorg: give the whole organization a unifying idea. The answer was KAITEKI—an attempt to fuse commercial ambition with a broader social mission, and to use that mission as the compass for transformation.

KAITEKI was defined as “the sustainable well-being of people, society and our planet Earth.” Through three core values—Sustainability, Health, and Comfort—the company said it would create innovative solutions globally in pursuit of KAITEKI, creating “KAITEKI Value today” to “ensure a bright future for tomorrow.” It drew on a familiar Japanese sensibility: balance, harmony, and long-term stewardship. Critics, meanwhile, pointed out the more practical side of any big corporate philosophy—it can also help legitimize painful decisions, including restructuring and portfolio exits.

From 2018 through 2020, those decisions started to show up more clearly. In March 2020, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation became a wholly owned subsidiary of Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings, taking the pharma business private. That move removed public-market constraints and gave the parent more flexibility over what came next—flexibility that would matter a lot when the group later reconsidered whether it belonged in pharma at all.

The parent company also updated its identity. Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Corporation changed its tradename to Mitsubishi Chemical Group Corporation—a signal that this wasn’t meant to be a passive umbrella over semi-independent businesses, but an actively managed group with a single strategic direction.

By this point, the shape of the portfolio was visible in the mix of businesses: petrochemicals were still the biggest piece, followed by performance chemicals and materials, then industrial gases, with healthcare a smaller but significant segment.

Not everything in this era was aspirational. The group also faced controversy tied to regulatory issues involving pharmaceutical data manipulation in 2010–2011, which led to corrective measures. It was a reminder that managing a sprawling conglomerate isn’t just about strategy—it’s about governance, incentives, and consistent standards across very different businesses.

Stepping back, the trade-offs were becoming unavoidable. Petrochemicals in Japan faced structural headwinds—demographics, Chinese overcapacity, and higher energy costs. Pharmaceuticals demanded ever-larger R&D spending with uncertain payoffs. Industrial gases delivered steadier profits, but it wasn’t the kind of business that would redefine the company’s growth story. Specialty materials—carbon fibers, battery materials, advanced films, specialty polymers—were where differentiation and durable growth still looked plausible.

Which set up the real test of KAITEKI: could Mitsubishi Chemical, with all its history and ingrained ways of operating, actually execute a transformation this deep?

That question led straight to the most dramatic personnel decision in the company’s modern history.

VIII. INFLECTION POINT #4: The Gilson Era—Western Leadership in a Japanese Institution (2021–2024)

Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings made a move that almost never happens in big-company Japan. It named Jean-Marc Gilson, a Belgian chemical executive, as CEO effective April 1, 2021, replacing Hitoshi Ochi upon his retirement. Gilson came in from the outside—most recently as CEO of Roquette, the French food and drug ingredients company—and brought a résumé built at Western multinationals, including executive roles at Dow Corning and Avantor Performance Materials. He also had something rare for a foreign chief executive in Japan: lived experience. He’d spent five years working in Japan for Dow Corning.

The appointment landed like a thunderclap. Japanese boards have historically preferred insiders—leaders shaped by the company, the industry, and the country’s consensus-driven way of making decisions. Bringing in a non-Japanese CEO signaled that Mitsubishi believed its challenges weren’t incremental. They were structural.

Officially, the rationale was straightforward. Mitsubishi pointed to Gilson’s track record executing growth strategies and portfolio transformation across specialty chemicals and life sciences. And in context, it fit a broader trend: Japanese chemical companies were beginning to widen the circle—more external directors, more diverse leadership benches, a little more willingness to import global playbooks.

Gilson, for his part, tried to set expectations early. He wasn’t pitching a dramatic abandonment of chemistry. He was pitching a different kind of chemical company. “I am not talking about abandoning the chemical industry,” he told reporters, “but adjusting our portfolio to make sure we have high-value products.” He cited DSM as a reference point—a company that had reshaped itself over the prior decade, shifting away from traditional chemicals toward food, nutrition, and health.

He also addressed the obvious question head-on: could a foreigner actually run a Mitsubishi descendant? Gilson acknowledged the challenge, but argued he wasn’t walking in blind. “I understand it is a big challenge not being Japanese, but I have always been in companies in which I am not a national,” he said. “For me, Japan is not new. I have some understanding of Japanese culture.” His Japanese wife and his prior stint living and working in the country helped, at least at the starting line.

In December 2021, he put his program into a banner phrase: “Forging the future.” Under that management policy, he pushed for growth and operational excellence through globalization of management practices, more disciplined marketing, cost-structure reform, and tighter working-capital management. In other words: bring Mitsubishi’s management operating system closer to what global specialty leaders run—and do it fast enough that performance actually changes.

Then came the most politically charged part: petrochemicals.

At Mitsubishi Chemical, Gilson argued that decarbonization and competitiveness required more than emissions targets. It required portfolio change. He said the firm would exit its carbon products and petrochemical businesses—language that was unusually explicit in Japan, where leaders often avoid definitive statements that could box in future consensus-building.

Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings followed with a plan to separate its petrochemical and carbon-based chemical operations into a standalone business—one it ultimately intended to exit. Gilson framed it not as surrender, but as realism. Japan’s energy costs, he warned, were headed higher “while the world moves toward carbon neutrality.” And he hoped Mitsubishi’s move would catalyze something bigger: that other Japanese chemical players would take similar steps, creating the conditions to consolidate and combine operations.

Importantly, Gilson wasn’t arguing Japan should stop making basic chemicals. He was arguing Japan couldn’t afford to make them the way it always had. He pointed to consolidation stories elsewhere—companies like Braskem in Brazil and LyondellBasell in the U.S.—as examples of how scale and integration can strengthen a national petrochemical sector. The message was: keep the capability, change the structure. “We need to concentrate managerial resources on the creation of a sustainable business model and technology,” he said at the press conference announcing the plan, adding, “Domestic production of basic chemicals is indispensable to national economic security.”

And then, just as the market was bracing for the hard part—execution—Gilson’s tenure ended.

In December 2023, Mitsubishi announced that Gilson would step down by April 2024, to be succeeded by Executive Vice President Manabu Chikumoto. The company said Chikumoto had “deep business expertise and is widely connected” in the industry. Investors reacted quickly: shares fell sharply on the news.

Outside observers were startled. “The departure of Gilson after three years is a surprise,” said Takato Watabe, an analyst with Morgan Stanley MUFG Securities. He noted that Mitsubishi had indicated further details on petrochemical joint ventures would come within the year—yet with Gilson leaving, “we think that these efforts are starting from scratch.” Mitsubishi also said it would unveil strategies under the new management structure in fall 2024.

Gilson’s own tone was steady. In a New Year’s message to employees, he said, “I am genuinely proud of the collaborative efforts we have put into [our strategy], and in fact the transformation efforts are bearing fruit in terms of performance.” He added that he was “committed to facilitating a seamless transition” through the end of March.

After leaving Mitsubishi, Gilson became President and CEO of Westlake in July 2024. His Mitsubishi chapter ran from April 2021 to April 2024—brief, by Japanese standards, especially for a change agent hired to rewrite a portfolio.

So what explains the short tenure? Analysts floated familiar possibilities: cultural friction with consensus-building, frustration with the pace and politics of petrochemical consolidation, or disagreements over capital allocation and how far, and how fast, Mitsubishi should go. The company’s public messaging emphasized the need for leadership able to “directly address” key management issues—including the restructuring of Japan’s petrochemical industry—hinting that in the most delicate negotiations, being an outsider may have shifted from advantage to handicap.

Either way, the agenda didn’t disappear with Gilson. Mitsubishi Chemical Group still described its key management issues as: (1) carbon neutrality and circular economy initiatives, (2) industry restructuring in the Japanese petrochemical business, (3) growth of the Specialty Materials business, and (4) further portfolio reform.

IX. INFLECTION POINT #5: The Pharma Divestiture—Exiting 350 Years of History (2024–2025)

If Gilson’s tenure was about forcing Mitsubishi Chemical Group to confront what it couldn’t keep doing, the next move was about confronting what it couldn’t keep owning.

In February 2025, Bain Capital announced it had signed a definitive agreement to acquire Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation in a carve-out transaction from Mitsubishi Chemical Group Corporation. The deal valued the business at about 510 billion yen, roughly $3.3 billion, and was led by Bain’s Private Equity teams in Asia and North America together with its Life Sciences team.

This wasn’t just another portfolio tidy-up. It was one of the most significant pharma transactions in Japanese history—and the cleanest possible break with a legacy that ran deep. Tanabe’s roots traced back to 1678. Its headquarters sat in Doshomachi, Osaka, the birthplace of Japan’s pharmaceutical industry. For Mitsubishi Chemical Group, selling it meant walking away from a business with centuries of identity attached to it.

Operationally, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma focused on discovering and developing drugs that addressed unmet medical needs, with priority therapeutic areas including immunology and inflammation, vaccines, central nervous system disorders, and diabetes and metabolic disease.

Mitsubishi Chemical Group said it planned to use the proceeds to reduce debt and reinvest in its core materials businesses. The transaction also transferred ownership of additional pharma subsidiaries Medicago and Alpha Therapeutic Corporation to Bain. Bain, meanwhile, framed the deal as a platform-building opportunity: it aimed to support Tanabe Pharma in building out a more innovative drug development engine and bringing new therapies to Japan and overseas.

“We believe there are promising signs for growth and untapped opportunities in Japan’s life sciences industry as government and regulators have launched several initiatives to accelerate the development and approval of innovative medicines in the Japanese market,” said Ricky Sun, a partner at Bain Capital Life Sciences.

Mitsubishi’s own explanation was equally direct, and telling. “We carefully explored the best owners for Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma to achieve future growth, and we have reached a conclusion that promoting a growth strategy under Bain Capital, which has extensive investment experiences in healthcare, is the best option,” the conglomerate said.

The deal was expected to close in the third quarter of 2025, subject to customary closing conditions, regulatory clearance, and shareholder approvals.

Then came the symbolic final cut. At a board meeting, it was resolved that the company name would be changed to Tanabe Pharma Corporation effective December 1, 2025. Dropping “Mitsubishi” wasn’t a branding tweak; it was the public marker that a 350-year-old institution was no longer part of Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s future.

The strategic logic was clear, even if it was painful. Management concluded that further growth in pharmaceuticals required continuous, additional investment to enhance R&D capabilities—investment it couldn’t justify while also trying to reshape its core chemicals portfolio. Better, in their view, to let an owner built for healthcare deploy the capital and focus the business demanded.

After shareholders approved the absorption-type split agreement at Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s Ordinary General Meeting on June 25, 2025, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and its subsidiaries and affiliates were classified as discontinued operations.

The divestiture reshaped what Mitsubishi Chemical Group was. The proceeds created room to deleverage and fund the specialty materials push. And going forward, the company became a simpler, more comparable story: more materials and industrial gases, less healthcare—easier to analyze, but also more exposed to the cycles and hard choices still embedded in basic chemicals.

X. The "Green Specialty Company" Vision: KAITEKI 2035

By the time Mitsubishi Chemical Group sold Tanabe Pharma, it wasn’t just slimming down. It was making room for a new identity. The company had already put that identity into words a few months earlier.

In November 2024, Mitsubishi Chemical Group announced KAITEKI Vision 35 (KV35) alongside a new Medium-Term Management Plan 2029 designed to make it real. KV35 is explicitly a backcasting exercise: start with what the world might demand by 2050, decide what kind of company MCG wants to be in 2035, then work backward into today’s priorities.

Anchored to the group’s purpose—“leading with innovative solutions to achieve KAITEKI, the well-being of people and the planet”—MCG defined five business focus areas: building a stable supply platform for green chemicals; eco-conscious mobility; advanced data processing and telecommunications; food quality preservation; and technology and equipment for new therapeutics.

Plan 2029 covers FY2025 through FY2029. It’s positioned as both an interim milestone and a concrete action plan on the path to KV35.

This wasn’t MCG’s first attempt to use KAITEKI as a strategic compass. The company had previously set KAITEKI Vision 30 by imagining 2050 in concrete terms and identifying social issues it could help solve, then backcasting to what it needed to build. But four years later, the world looked meaningfully different: the pandemic, faster-moving climate risks, and rising geopolitical tensions all made supply chains, energy, and industrial policy feel less theoretical and more urgent. The chemical industry’s own marching orders—carbon neutrality and circular-economy contribution—only got louder. Against that backdrop, leadership revisited KAITEKI Vision 30 and refreshed the vision and strategy for 2035.

MCG wasn’t alone. Japan’s big chemical producers were, broadly, trying to pull off the same pivot: away from the old model of integrated petrochemicals and sprawling portfolios, and toward specialties with clearer differentiation. Across the industry, companies were shedding noncore assets, exiting weaker businesses, and concentrating investment in areas seen as structurally growing.

The hardest piece to unwind, though, was still petrochemicals.

Manabu Chikumoto, who took over as CEO in April 2024, described the problem in plain terms: “To ensure the sustainability of the petrochemical business while making the necessary investments in energy conservation and greener raw materials in Japan under the challenging environment, we need to create a stronger and larger petrochemical company.” He added that MCG was “holding discussions with various companies, both upstream and downstream, based on fairness,” and that it hoped to show “a certain direction” on petrochemical restructuring.

That sense of urgency came from the fundamentals. Domestic demand has been pressured by Japan’s shrinking and aging population, while global competition has intensified. Over the past two years, profit declines across Japanese petrochemicals pushed companies to take steps on their own: Mitsui closed a polypropylene plant at its Chiba facility; Asahi Kasei pursued a restructuring that included exiting some commodity chemical and other businesses with total annual sales of about $700 million; and Sumitomo Chemical moved to restructure dozens of business units, including its polyolefin operation in Japan. But even the leaders inside these companies increasingly acknowledged that one-by-one fixes wouldn’t be enough. Some voices in the industry began calling for more coordinated solutions, including ethylene production cooperatives in eastern and western Japan.

Inside MCG, the response was laid out in its Basic Materials & Polymers strategy: shift toward a business model oriented around domestic demand for derivatives, optimize capacity, and tilt the mix toward higher value-added products. It also called for cost reductions and for passing costs through into pricing. A central element was restructuring the West Japan cracker to establish a new olefin supply structure based on derivative demand, while promoting GX—green transformation.

And this is where the story tightens. While petrochemicals were being boxed into a smaller, more disciplined role, specialty materials were being positioned as the growth engine. Management pointed to the kinds of businesses where Mitsubishi could earn its keep: advanced films used in semiconductors, carbon fiber composites for electric vehicles, battery materials for energy storage, and specialty polymers for more sustainable packaging.

The bet is straightforward. The execution is not. Mitsubishi Chemical Group now has to pull off a pivot toward these higher-value, more differentiated materials at the exact same time it manages the slow grind of petrochemical decline—and tries to reshape the Japanese petrochemical industry in a way that’s viable for a carbon-constrained future.

XI. Core Business Deep Dive: What They Actually Make

To understand Mitsubishi Chemical Group as a business, you have to get past the logo and the legacy and look at what it actually sells. Because “chemicals” here doesn’t mean one thing. It’s a sprawling menu that runs from commodity building blocks to the high-tech materials that quietly make modern life possible.

Specialty Materials: The Growth Engine

If there’s a center of gravity in the new Mitsubishi story, it’s Specialty Materials. This is where the company has been trying to earn better pricing, build defensible positions, and ride structural growth markets instead of GDP.

Within the segment, three areas stand out. Advanced Films & Polymers has benefited from stronger pricing and rising demand in barrier packaging. Advanced Solutions has also improved price positioning, supported by the completion of large-scale water treatment equipment projects used in semiconductor manufacturing. Advanced Composites & Shapes has seen growing demand for high-performance engineering plastics—materials chosen because they outperform alternatives, not because they’re the cheapest option.

One of the clearest examples is carbon fiber reinforced plastic, or CFRP. Mitsubishi Chemical supplies CFRP to help reduce vehicle weight, a big lever for improving efficiency. The group produces PAN-based carbon fiber using acrylonitrile as a raw material, and pitch-based carbon fiber made from coal tar. The advantage it emphasizes is vertical integration: it handles manufacturing and sales all the way from raw materials to the carbon fiber itself, to intermediate materials, and on to CFRP. Over time, it has also built know-how not just in making fiber, but in material design and molding and processing—capabilities that matter when you’re selling into applications like automotive, aerospace, and sports equipment.

That strategy showed up in a small but telling deal move. On January 10, 2024, MCG acquired additional shares in C.P.C. S.r.l. from its subsidiary Mitsubishi Chemical Europe GmbH. C.P.C. manufactures and distributes CFRP automotive components. Mitsubishi Chemical Group had owned 44% of C.P.C. since 2017 as an equity-method affiliate; the additional purchase made C.P.C. a wholly owned subsidiary.

MMA: The Hidden Global Champion

One of Mitsubishi’s less obvious strengths is in methacrylates—specifically methyl methacrylate, or MMA, the building block behind acrylic products. Mitsubishi Chemical America’s Methacrylates Division describes itself as the global leader in the manufacture and sale of methacrylate products, with manufacturing, sales, and distribution affiliates spanning EMEA, the Americas, and Asia Pacific. It positions the business as both the muscle and the engine behind many well-known acrylic-based products.

MMA is also a consolidated global market. Key players include Mitsubishi Chemical, Rohm, Dow, Sumitomo Chemical, and LGMMA, among others, with the top five holding roughly 70% share. Asia-Pacific is the largest market at about 60%, with North America and Europe together making up about 40%.

Mitsubishi has been leaning into that position with new capacity and technology. In September 2023, the group set up an MMA production facility in Japan, aimed at strengthening its global leadership. Then in February 2024, Mitsubishi Chemical America announced plans for a new MMA plant in the U.S., with a final investment decision expected in the second quarter. The proposed facility, called the MCA Geismar Site, is planned to produce 350,000 tons per year using the Alpha process technology, with a potential start-up in 2028.

Alongside expansion, the company has also highlighted work on PMMA recycling technology and bio-based MMA monomers—framing the methacrylates business not just as a scale play, but as part of its sustainability and circular-economy push.

Battery Materials: The EV Play

Mitsubishi Chemical Group pitches its automotive offering as a portfolio built for demanding applications: carbon fiber, composites, high-performance engineering plastics, and films, among others. The thread running through all of it is the same idea as Specialty Materials broadly: products that win because they enable performance.

In batteries, the company is a leading provider of formulated electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries in automotive applications. Its Sol-Rite electrolytes are formulated in organic solvents with functional additives designed to significantly improve battery performance.

Industrial Gases: The Steady Cash Cow

If Specialty Materials is the growth engine, industrial gases are the stabilizer. Nippon Sanso Holdings Corporation is a consolidated subsidiary of Mitsubishi Chemical Group, and one of the major global suppliers of industrial gas, with operations across Japan, the United States, Europe, and the Asia-Oceania region.

Under that umbrella, Taiyo Nippon Sanso manufactures and sells gases like oxygen, nitrogen, and argon for factories and other industrial uses. In North America, the operating entity is MATHESON, which is also the largest subsidiary of Nippon Sanso Holdings.

Nippon Sanso Holdings is described as one of the top four suppliers of industrial gases globally and the largest in Japan, and it remains connected to Mitsubishi through the broader Mitsubishi keiretsu structure.

XII. Financial Performance and Portfolio Transformation

All of this strategy talk only matters if it shows up in the numbers—and in fiscal year ended March 31, 2025, you can see the first signs of the new Mitsubishi taking shape.

Sales revenue came in at ¥4,407,405 million, slightly up from ¥4,387,218 million the year before. The bigger story was profitability: gross profit rose from ¥1,146,824 million to ¥1,279,594 million, and core operating income climbed to ¥298.4 billion—up 43.4% year over year.

Zoom in and you see a company operating in uneven conditions, but managing through them. In the first quarter of the fiscal year ending March 2025, the environment continued a moderate recovery overall, though demand differed by region and industry. Compared to the same quarter in the prior year, sales revenue rose 6.4% to ¥1,129.4 billion, and core operating income increased 62.6% to ¥82.6 billion.

But the numbers also come with a big caveat: pharma. As Mitsubishi moved its pharmaceutical business into discontinued operations ahead of the Tanabe divestiture, year-over-year comparisons started to get distorted. In the first quarter of FY2026, sales revenue fell 13.4% to ¥880.7 billion versus the prior-year quarter—largely reflecting the change in what counted inside the continuing group, not a sudden weakening in the remaining businesses.

And that gets to the point. Mitsubishi is deliberately changing what it is. Under its portfolio transformation program, the company said it planned to restructure an additional 30 businesses from 2024 to 2029, representing about $2.7 billion in annual sales. The plan included stepping away from noncore operations like triacetate fiber, and continuing to reduce petrochemical capacity—less about shrinking for its own sake, and more about clearing space for the “Green Specialty” future it says it’s building.

XIII. Bull Case: The Green Specialty Transformation

The bull case for MCG is that it can actually pull off what KAITEKI Vision 35 promises: shrink the drag of commodity petrochemicals, and let higher-value, harder-to-replicate specialty materials become the company’s profit engine. If that happens, a few parts of the portfolio look especially well positioned.

Global MMA Leadership: Mitsubishi is a global leader in MMA, backed by proprietary Alpha technology. MMA demand tends to rise and fall with big end markets like construction, automotive, and electronics. The market itself is expected to grow steadily through the next decade, and Mitsubishi’s story here isn’t just scale—it’s cost-competitive production plus work on recycling capabilities that matter more as customers and regulators push for circularity.

Carbon Fiber and Composites Vertical Integration: In carbon fiber and composites, Mitsubishi’s advantage is the “full stack”—from raw materials to finished components and, importantly, into recycling. The group frames this as a closed-loop model aimed at supporting a circular economy. And the timing is favorable: as EV adoption grows and “lightweighting” becomes a design requirement, carbon fiber composites can command premium pricing because they enable performance, not because they’re cheap.

Industrial Gases Stability: Nippon Sanso Holdings gives MCG something most chemical companies crave: steadier cash flows with less direct exposure to the worst of commodity cycles. It’s also geographically diversified and tied to structural demand drivers like semiconductor manufacturing. In the bull case, this business acts as the ballast—helping fund specialty investments while the rest of the portfolio is being reshaped.

Battery Materials Positioning: MCG’s battery materials business plugs into the EV value chain in a different way than carbon fiber. It is a leading provider of formulated electrolytes for automotive lithium-ion batteries, with Sol-Rite electrolytes designed with functional additives to improve battery performance. If the shift to electrification keeps compounding, this is a clean way to participate without needing to win the entire battery pack.

Japanese Petrochemical Consolidation: Finally, the “less exciting” part of the bull case may be the most important near-term: petrochemicals get less bad. There’s precedent that rationalization works. Japan’s ethylene capacity fell meaningfully in the mid-2010s after closures, and industry profitability improved. Mitsubishi and Sumitomo, for example, saw profits roughly double between fiscal 2016 and 2017 in large part because petrochemical profitability strengthened. If MCG can be a catalyst for the next wave of consolidation, it can turn a structural headwind into something closer to a managed runoff—freeing capital and management attention for the specialty push.

XIV. Bear Case: Execution Risk and Structural Challenges

The bear case for Mitsubishi Chemical Group isn’t that the vision is wrong. It’s that the world MCG operates in can be unforgiving—and transformation is hard even when everyone agrees it’s necessary. Here are the risks that could keep KAITEKI Vision 35 from turning into shareholder returns.

Petrochemical Decline Is Structural: The restructuring of Japan’s petrochemical industry is still early, and the competitive gap keeps widening. China has been adding massive new ethylene capacity plant after plant, and those newer facilities often come with structural advantages—cheaper feedstocks, lower labor costs, and newer, more efficient assets. For Japanese producers with aging domestic infrastructure and higher costs, this isn’t a temporary downturn; it’s a permanent squeeze.

Cultural Resistance to Change: Gilson’s exit after only three years put a spotlight on a question investors had from day one: can a Mitsubishi descendant truly execute Western-style portfolio rationalization at speed? The consensus-driven Japanese management model helped rebuild and scale the postwar group—but it can also slow decisions, soften accountability, and make it harder to push through painful restructuring when every stakeholder needs to be brought along.

Specialty Materials Competition Intensifying: Even in the “good” businesses, nothing is guaranteed. Carbon fiber competes with lower-cost alternatives like glass fiber and even metals in applications where premium performance isn’t required. Battery materials can face pricing pressure, especially if electric vehicle demand grows more slowly than expected. Semiconductor-related materials benefit from powerful secular tailwinds, but the end markets are still cyclical—meaning earnings can swing hard.

Complex Conglomerate Discount: Even after the pharma sale, MCG is still a multi-business group with very different economic profiles under one roof. That complexity can weigh on valuation. Investors who want exposure to specialty materials may prefer simpler, pure-play companies, and the market may continue to apply a discount for a structure that’s harder to analyze—and harder to manage.

China and Geopolitical Risk: MCG sells into China and competes against Chinese producers. That creates two layers of exposure at once: demand risk if geopolitical tensions disrupt customer behavior, and supply-chain risk if trade frictions or export controls complicate materials and equipment flows.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis: - Supplier Power: Moderate. Commodity petrochemical feedstocks are largely priced by global markets, but some specialty inputs can tighten and become constrained. - Buyer Power: Mixed. Commodity chemicals often face powerful buyers with leverage, while specialty products—especially those embedded in automotive and semiconductor supply chains—can command better pricing once qualified. - Competitive Rivalry: Intense in petrochemicals; more favorable in certain specialty niches where differentiation matters. - Threat of Substitutes: High in some applications (for example, glass fiber replacing carbon fiber in non-critical uses), lower in others (like formulated electrolytes that are tuned to specific performance requirements). - Threat of Entry: Low in MMA, where scale and proprietary technology matter; more moderate in specialty materials where new entrants can emerge, even if qualification takes time.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Assessment: - Scale Economies: Stronger in MMA and industrial gases; less pronounced across many specialty materials. - Network Effects: Absent. - Counter-Positioning: The Green Specialty pivot is an attempt at this, but the advantage isn’t proven yet. - Switching Costs: Moderate where customer qualification creates friction. - Branding: Limited, given the realities of B2B chemical markets. - Cornered Resource: The Alpha MMA technology stands out as a real proprietary asset. - Process Power: Potentially present in carbon fiber through vertical integration, but it has to translate into durable margins to truly count.

XV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s “Green Specialty” pivot is actually happening, three signals do most of the work.

1. Specialty Materials Core Operating Income Margin: This is the cleanest read on whether the shift toward higher-value materials is showing up where it counts—profitability. If Specialty Materials can steadily lift margins toward the kind of double-digit level that specialty businesses are expected to earn, it means differentiation is turning into real pricing power and better mix, not just nicer slide decks.

2. Portfolio Transformation Sales (JPY): Management’s portfolio-reform goal is changes equivalent to JPY400 billion in sales revenue by FY2029, and it has already resolved changes equivalent to JPY360 billion. The key here is follow-through. Track whether “resolved” becomes “done”—completed divestitures, exits, and restructurings—because this is the metric that separates hard choices from plans that never leave the conference room.

3. Net Debt to Core Operating Income Ratio: The Tanabe proceeds should help deleveraging. But the specialty push still needs investment, and petrochemical restructuring can be cash-hungry in the short term. This ratio tells you whether MCG is buying itself enough financial room to maneuver. Roughly speaking, below 3x signals a healthier capital structure; above 4x starts to limit flexibility and raises the stakes of execution.

XVI. Myth vs. Reality: Testing the Consensus Narrative

Myth: MCG is primarily a petrochemical company.

Reality: Petrochemicals get the headlines because they’re cyclical, politically sensitive, and tied up in Japan’s broader industrial policy. But they’re only about a third of revenue. Industrial gases are closer to a quarter of sales and tend to carry better margins. And the center of the company’s strategy—the part management keeps trying to feed with capital and attention—is specialty materials. With pharma leaving the picture, the mix tilts even further toward materials and gases.

Myth: The Gilson departure signals failed transformation.

Reality: Gilson didn’t arrive to run business as usual—he arrived to set a new direction and start cutting away what didn’t fit. He put portfolio rationalization on the table and pushed the organization toward a clearer “Green Specialty” identity. His successor, Manabu Chikumoto, comes with deep petrochemical expertise, which may matter more in the next phase: the slow, negotiation-heavy work of Japanese industry consolidation. The agenda didn’t disappear. The face at the front of the room changed.

Myth: Japanese chemical companies cannot compete globally.

Reality: The global competitiveness question isn’t evenly distributed across the portfolio. In methacrylates, MCG is the world’s largest producer, backed by proprietary technology. In industrial gases, Nippon Sanso Holdings sits among the top four global suppliers. Where the pressure is most intense is commodity petrochemicals—businesses where scale advantages have shifted toward newer, lower-cost capacity, especially in China. In specialties, Mitsubishi’s problem is less “can we compete?” and more “can we stay focused enough to keep winning?”

Myth: Carbon neutrality goals are greenwashing.

Reality: There’s real activity behind the rhetoric, even if the economics are still being written. Asahi Kasei, Mitsui Chemicals, and Mitsubishi Chemical have been advancing a joint feasibility study on carbon neutrality for ethylene production facilities in western Japan. MCG has also been investing in bio-based materials, recycling, and production efficiency. The open question isn’t whether the company is trying. It’s whether these efforts can scale into businesses that make money—not just promises that sound good.

XVII. Competitive Positioning and Industry Context

Mitsubishi Chemical Group isn’t trying to reinvent itself in a vacuum. Every major chemical player is staring down the same forces—decarbonization, shifting global capacity, and the blunt reality that commodity chemicals are getting harder to make money in. One useful way to see what MCG is up against is to line it up against the companies it most often gets compared to.

Versus BASF (Germany): BASF is bigger and more globally diversified, but it’s wrestling with a familiar problem: legacy petrochemical assets under pressure, especially in Europe. Both companies are trying to tilt toward specialties. The difference is geography. MCG’s home-field advantage is Asia; BASF’s is Europe and the Americas.

Versus Dow (United States): Dow’s modern shape is the product of simplification—splitting from DuPont and shedding specialty-heavy pieces. That has left Dow with a cleaner, more focused portfolio and generally higher profitability. MCG, by contrast, is still living with conglomerate complexity. That complexity can be a drag. But if the specialty pivot works, it can also become a strength—more ways to win, and more internal cash generation to fund the transition.

Versus LG Chem (Korea): LG Chem has pushed hard into the battery and EV value chain, with a sharper, more concentrated bet. That focus can drive speed, but it also raises concentration risk if a single end market slows. MCG’s bet is broader across advanced materials—arguably a more diversified platform, but one that has moved at a slower pace.

Versus Linde/Air Liquide: In industrial gases, Nippon Sanso Holdings goes up against two of the global giants: Linde and Air Liquide. It’s at a scale disadvantage in many regions, but it has a strong position in Japan—and a focus in areas like semiconductors where reliability, proximity, and long-term contracts can create real defensibility.

Versus Other Japanese Chemical Companies: MCG’s transformation is also part of a wider domestic wave. Japan’s chemical leaders have been shedding noncore assets, exiting weaker sectors, and trying to concentrate investment in higher-growth areas like advanced materials and environmental technologies. MCG is bigger than most of its local peers, but it faces the same structural headwinds. If the industry can find a coordinated path to consolidation, everyone could benefit. If companies optimize for themselves first, it risks turning into a prisoner’s dilemma—where rational moves individually still produce an irrational outcome for the sector.

XVIII. Looking Forward: The Road to 2035

“Solving social problems and delivering impressive results to customers with the power of materials as a Green Specialty Company.” That’s Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s specific vision for 2035—and it’s ambitious enough that the next decade will decide whether it becomes a real operating identity or stays a well-crafted slogan.

A few forces could meaningfully accelerate the transformation.

Potential Catalysts for Upside: - Real consolidation in Japan’s petrochemical industry that rationalizes capacity and improves pricing discipline - Electric vehicle adoption accelerating faster than expected, lifting demand for carbon fiber and battery materials - A strong semiconductor capex cycle that pulls through industrial gases and specialty materials - Bio-based materials reaching cost competitiveness, making “sustainable” something customers will consistently pay up for

And just as clearly, a few shocks could knock the story off course.

Potential Catalysts for Downside: - Chinese overcapacity spilling beyond commodities and into specialty markets, pressuring prices and margins - An EV demand slowdown that reduces volumes in carbon fiber and battery-related materials - Industrial gases becoming more competitive through new capacity, aggressive pricing, or both - Missteps in the portfolio transformation—selling the wrong assets, holding the wrong ones too long, or failing to improve execution in the businesses that remain

Stepping back, Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s story has always been one of adaptation. New businesses keep emerging at the edge of political and social change, and Mitsubishi has repeatedly found ways to ride that edge: from Yataro Iwasaki’s steamships, to wartime materials production, to postwar rebuilding, to the petrochemical boom, and now to the green transition.

What’s different this time is the constraint. For long stretches of its history, growth came from adding capacity, adding adjacency, and adding businesses. Now, the path forward is just as much about subtraction—exiting, restructuring, and focusing—as it is about invention.

Standing still isn’t an option. Decarbonization, digitalization, circular-economy requirements, and relentless competition—especially from China—aren’t cyclical headwinds. They’re the new baseline. Mitsubishi Chemical Group has laid out a coherent plan for navigating that baseline. The open question is whether management can turn that plan into durable results.

A company that began with three aging steamships has already survived dissolution, occupation, and multiple economic rewrites. Getting to 2035 as a true Green Specialty materials leader may be its hardest reinvention yet—and for shareholders, the one with the most at stake.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music