Nippon Sanso Holdings: The Quiet Empire Behind Every Industry

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the humming floor of a semiconductor fab in Kumamoto. Robots glide through bright cleanrooms under amber lights, feeding silicon wafers into deposition and etching tools that can cost more than a skyscraper. The entire operation depends on a set of inputs that are easy to overlook because they’re literally in the air: ultra-high-purity gases, delivered flawlessly, 24/7.

Now jump to the other end of the economy. A steelworks like Nippon Steel’s Kashima complex, where blast furnaces run hot enough to turn iron ore into molten metal. Or a hospital ward in Osaka, where medical oxygen is the difference between recovery and catastrophe. Or the Thermos bottle on millions of kitchen counters—keeping coffee hot for hours, thanks to a vacuum that only exists because someone mastered cryogenics and precision materials.

What connects all of these worlds isn’t a famous brand or a Silicon Valley unicorn. It’s a company most global investors have never heard of: Nippon Sanso Holdings Corporation, commonly known as NSHD. It’s a holding company that sits over a family of businesses, including Taiyo Nippon Sanso, a major industrial gas manufacturer, and Thermos, the stainless-steel vacuum bottle maker.

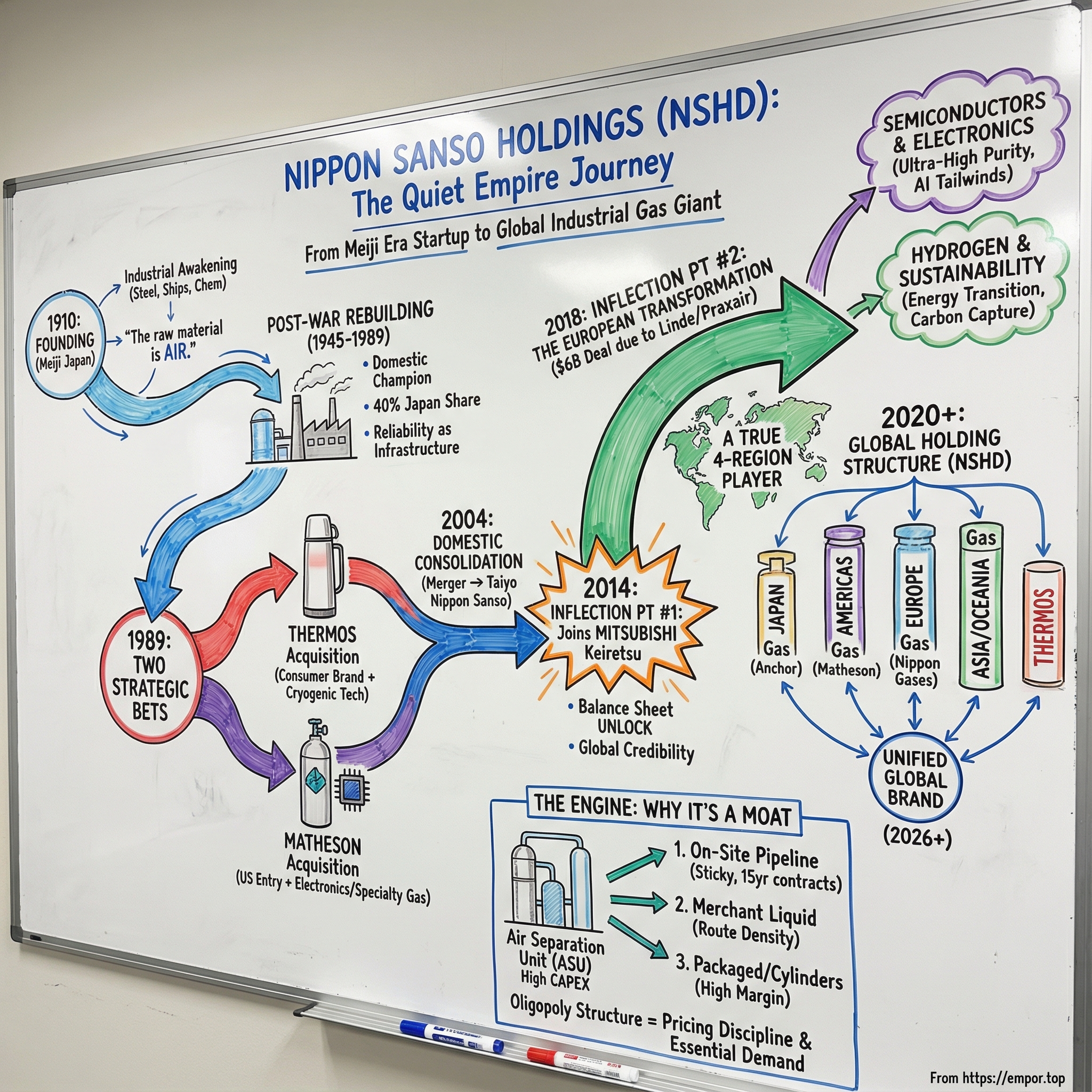

The origin story goes back further than you’d expect. Nippon Sanso was first established in 1910 as the Nippon Sanso joint-stock company—making it one of the oldest industrial gas companies in Asia. Its roots reach into the final years of the Meiji era, when Japan was rapidly reinventing itself from a feudal society into an industrial nation that needed steel, chemicals, ships, and the infrastructure to make them.

What makes NSHD remarkable isn’t just that it survived a century. It’s that it embedded itself into the operating systems of modern industry. Oxygen, nitrogen, and argon aren’t “products” in the way consumers think about products. They’re requirements. They show up in steel, chemicals, electronics, automobiles, construction, shipbuilding, and even food. When a customer runs out, it isn’t inconvenient—it can shut down a production line.

This creates a market structure that’s the opposite of most tech narratives. Industrial gases is highly consolidated, dominated by five giants: Air Liquide, Linde, Air Products, Messer, and Nippon Sanso Holdings. Together, they account for about 80–84% of the market. In an era where investors chase disruption, this is an old-school oligopoly with deep barriers to entry and a business model built around reliability, scale, and long-term relationships.

Today, NSHD is a consolidated subsidiary of the Mitsubishi Chemical Group. It operates across Japan, the United States, Europe, and the Asia-Oceania region, spanning more than 30 countries through its brands, subsidiaries, and affiliates.

The journey from a small oxygen producer in Meiji Japan to the world’s fourth-largest supplier of industrial, electronic, and medical gases is a story of patient capital allocation, well-timed M&A, and a few strategic pivots that changed everything. It includes the surprising link between Thermos and cryogenic engineering, a European deal in 2018 that cost nearly six billion dollars, and an electronics-focused gas business that lines up neatly with the semiconductor boom now reshaping the global economy.

That’s the roadmap. We’ll go from the early industrial awakening that created demand for oxygen, through the post-war surge that made Nippon Sanso a domestic champion, into the Mitsubishi tie-up that unlocked global firepower, and finally the European transformation that turned it into a true four-region player. Along the way, we’ll unpack why industrial gases may be one of the most misunderstood moat businesses in the world—and what comes next as NSHD leans into semiconductors, hydrogen, and sustainability.

II. Industrial Gases 101: Understanding the Business

Before we go back to 1910, we need to understand the trick that makes this whole industry so powerful. Industrial gases look like a commodity business. In practice, they behave like infrastructure.

It’s a global market that tops $100 billion in annual revenue, dominated by an unusually tight club: Air Liquide, Linde, Air Products, Messer (private), and Taiyo Nippon Sanso. Five players, worldwide footprints, and decades of consolidation. That structure matters, because it sets the rules of the game.

On the surface, the product is almost comically simple. Industrial gas companies take ordinary air and separate it into its component parts—mostly nitrogen and oxygen, plus argon and trace gases. Broadly, you can think of the output as two families. Atmospheric gases like nitrogen, oxygen, argon, and rare gases such as krypton, neon, and xenon, made by purifying, compressing, cooling, distilling, and condensing air. And process gases, produced as part of other industrial reactions.

So where does the moat come from, if the inputs are everywhere and the outputs are standardized?

Distribution—and the contracts and infrastructure wrapped around it.

The business splits into three core models, based on how the gas reaches the customer.

On-site is the crown jewel. Here, the gas company builds a dedicated air separation unit, often right next to a customer’s plant, and supplies gas by pipeline. These projects are won through competitive bids—who can build and operate the unit most efficiently and reliably. The payoff is the contract structure: long-term take-or-pay agreements, typically in the 10-to-20-year range, often with a minimum guaranteed return baked in. In plain English: the customer is committing to pay for a baseline volume whether they use it or not.

And once the unit is built, the lock-in isn’t theoretical. It’s physical. Steel, concrete, pipelines, controls, safety systems—an installation that’s deeply embedded in the customer’s process. Switching suppliers is not like changing a software vendor. It’s more like ripping out a power plant.

Merchant is the middle of the market. Instead of a dedicated on-site unit, gas is produced at regional plants and delivered as liquid via tanker truck to customers who are too small for their own ASU but too large to rely on cylinders. This is where route density becomes an advantage: the supplier with the most plants, trucks, and customers in a geography can serve everyone more efficiently.

Packaged gases—cylinders—serve the long tail: labs, hospitals, welding shops, and high-value niches. This is also where you start to see extreme purity requirements and specialty mixes, including for electronics and semiconductor manufacturing. Fewer molecules, far more margin.

There’s one more twist: in this industry, the customer is often the most credible competitor.

Every large buyer faces a choice. Do they outsource and lock in a supply contract? Or do they build and run their own production facilities? That threat creates a natural ceiling on pricing. Push too hard, and the biggest customers start to sharpen their pencils and consider insourcing. But for most of them, the operating complexity, safety requirements, maintenance burden, and scale advantages of the gas specialists usually make outsourcing the rational decision.

Put it all together and you get a rare combination. High barriers to entry. Defensive growth. Essential inputs. Customers that can’t tolerate failure. And competitors that are big enough—and few enough—to behave rationally.

This is the key asymmetry: the value of the gas itself is small compared to the cost of not having it.

If a steel mill loses oxygen, production stops. If a semiconductor fab loses nitrogen, batches of wafers can be ruined. If a hospital runs short on medical oxygen, it’s a crisis. The gas bill is not the scary part. The downtime is. That’s why customers prioritize reliability, safety, and total cost of ownership over squeezing out a tiny discount.

After decades of mergers and acquisitions, the top tier—Linde, Air Liquide, and Air Products—collectively controls close to 70% of the market. Even in downturns like 2008–09, pricing discipline held up better than you’d expect from anything that looks like a “commodity,” because in an oligopoly, nobody actually wins a price war.

And then there’s the capital intensity, which sounds like a drawback until you see what it creates. Building an ASU requires serious upfront investment. But once it’s in place, each incremental unit of volume sold is highly profitable, and utilization drives everything. Fill the plant, and the economics start to compound.

This is the foundation for understanding Nippon Sanso Holdings. The question isn’t whether industrial gases is attractive. The question is how a century-old Japanese company positioned itself inside one of the most structurally advantaged industries in the global economy—and how it used a few pivotal moves to go from domestic champion to global top-five player.

III. Founding Era: Japan's Industrial Awakening (1910-1945)

To understand why Nippon Sanso existed at all, you have to understand Japan in 1910.

The Meiji era was Japan’s great reinvention. In a few decades, the country sprinted from an isolated feudal society—uneasily watching Western powers carve up influence across Asia—into a modern industrial nation-state. Railways, telegraphs, factories, a modern military, a new legal system, new universities. Japan imported ideas and expertise at scale: students sent abroad to study Western science and engineering, foreign specialists brought in to teach and build at home. The state poured money into infrastructure and actively backed the rise of powerful industrial groups.

The national mission had a slogan: fukoku kyōhei—enrich the country, strengthen the army. And as Japan built the industrial base to match that ambition, the demand picture came into focus.

Steel mills expanded. Shipyards launched ever-larger vessels. Chemical plants ramped up explosives and fertilizers. Across all of it ran a quiet requirement Japan couldn’t meet domestically at commercial scale yet: oxygen, nitrogen, and other separated gases.

This is where the founding story of Nippon Sanso begins—less with a grand vision, and more with a very specific financing conversation.

One of the company’s founders, Takehiko Yamaguchi (founder of what is now Azbil Corporation, formerly Yamatake Shokai, and also connected to what is now NSK Ltd.), wanted to start an oxygen business. He didn’t have the capital to do it alone. So he approached Korekiyo Takahashi—then deputy governor of the Bank of Japan and later prime minister—and laid out the pitch.

It wasn’t a complicated pitch. It was one line: “the raw material is air.”

That sentence did two things at once. It made the opportunity feel inevitable—how could you not want a business whose input is everywhere?—and it hinted at the real trick of industrial gases: take something free and abundant, apply technology and capital, and deliver it reliably to customers for whom “running out” is not an option.

Takahashi was intrigued. With approval from the Bank of Japan’s board members, capital was arranged, and Nippon Sanso Ltd. was established as a partnership company.

Nippon Sanso was first established in 1910 as the Nippon Sanso joint-stock company, and later formally founded as Nippon Sanso Corporation in 1918. That 1918 timing mattered. World War I had reshaped trade flows, and Japanese industry benefited as European producers focused on the war and Asian markets opened up.

The company moved quickly from formation to production. By 1911, oxygen production had begun at its Osaki factory. And over the next couple of decades, it pushed from being a distributor of a new industrial input to becoming a builder of serious domestic capability. In 1935, Nippon Sanso completed its first domestically designed air separation unit—a milestone that signaled Japan’s growing ability to stand on its own industrial technology.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, the company scaled alongside Japan’s heavy industrial engine. Shipyards needed oxygen for welding. Steelworks needed oxygen in huge volumes. Chemical producers needed nitrogen as an input to core processes. Nippon Sanso’s role was rarely visible, but increasingly indispensable: it was infrastructure, delivered as a product.

Then came World War II, and the logic of “essential input” took on a darker meaning.

Industrial gases sit underneath industrial production, and wartime production is industry turned up to maximum intensity. Ships, aircraft, armored vehicles, weapons—nearly all of it touched oxygen or nitrogen somewhere in fabrication, welding, heat treatment, or chemicals. Nippon Sanso became part of Japan’s wartime supply chain not because it was a consumer brand making choices, but because its output was embedded in manufacturing itself.

The war years meant capacity expansion to meet military-driven demand—and then, near the end, devastation. American bombing campaigns tore through Japan’s industrial base. By August 1945, the country’s infrastructure was shattered and the economy was in collapse.

But Nippon Sanso, as an organization, endured. The plants and logistics could be rebuilt. The deeper asset—the know-how, the operating discipline, the understanding of how to supply mission-critical molecules safely and reliably—was still there.

And in the postwar years, that would turn out to be exactly what a rebuilding Japan needed.

IV. Rebuilding Japan: The Post-War Boom (1945-1989)

The Japan of 1945 was a wasteland. Major cities had been burned to the ground. Industrial capacity had collapsed. Food shortages were severe. Under U.S. occupation, the country looked—on paper—like it had been knocked out of the modern economy.

And then something extraordinary happened.

Over the next few decades, Japan engineered the economic miracle: growth so fast and so sustained it turned a defeated nation into the world’s second-largest economy within a generation. If you want to understand how that was possible, you don’t just look at the famous consumer brands. You look at the quiet infrastructure suppliers that made factories run. Companies like Nippon Sanso.

As Japan rebuilt, Nippon Sanso scaled into a domestic powerhouse, becoming a leading manufacturer with around a 40% share of the Japanese industrial gases market—built on a reputation for safe, reliable, high-quality supply.

That kind of dominance wasn’t won with a single breakthrough. It came the way this industry always does: patient investment, technical excellence, and relationships that harden into dependency. When automakers like Toyota and Nissan expanded, they needed gases for cutting, welding, and manufacturing. When steelmakers increased output, they needed oxygen at enormous volumes. As Japan’s electronics industry took off, demand shifted toward higher-purity gases for components and early semiconductor production. The molecules were simple; the requirement was not: deliver them flawlessly.

A key moment came in 1954, when the company established its Kawasaki plant, expanding the production of liquefied oxygen, high-purity nitrogen, and argon. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Nippon Sanso kept widening its footprint across the country, matching Japan’s industrial build-out plant by plant and customer by customer.

Then, in 1971, it did something that put its engineering credibility on the global map. Nippon Sanso completed the world’s first air separation unit that utilized LNG cold energy in Tokyo—capturing the frigid energy released during LNG regasification and using it to help drive the air separation process. It was a clever piece of systems engineering, and more importantly, it signaled that Japanese industrial gas technology wasn’t playing catch-up anymore.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Nippon Sanso was deeply woven into Japan’s relationship-driven industrial system. Long-term supplier partnerships and the broader stability of Japanese capitalism suited industrial gases perfectly. This is a business where trust matters, where safety is existential, and where the real asset is the right to keep supplying a customer year after year.

But as the 1980s progressed, a harder question started to surface inside the company: how does a Japanese champion—strong at home, but mid-sized by global standards—compete with giants like Air Liquide and Linde, whose balance sheets and geographic reach were on a different scale?

In 1989, Nippon Sanso placed two bets that would define the next era.

In 1989 it acquired Thermos Japan and Matheson (compressed gas & equipment).

At first glance, the pairing looked strange: a consumer thermos brand and an American industrial gas player. In reality, it was a blueprint for global expansion plus a hedge into higher-value niches.

Matheson was the strategic spearhead into the United States—and into specialty gases, where purity, handling, and process integration matter far more than volume alone. In 1989, Matheson Gas Products was purchased by Nippon Sanso Corporation. A few years later, in 1992, Nippon Sanso also purchased Tri-Gas of Irving, Texas. The operations weren’t merged until 1999, when the company formed Matheson Tri-Gas, combining industrial and specialty gases with related equipment.

This wasn’t just a geographic foothold. Matheson had deep roots in the gases that underpin modern electronics. Its portfolio supported the rise of the integrated circuit, supplying gases like arsine and phosphine in the industry’s early days, and later delivering the world’s first commercially produced silane—an accomplishment that earned the “SEMMY” Award. In 1989, it wasn’t obvious how central semiconductors would become to the global economy. But Nippon Sanso had just bought itself a front-row seat.

Then there was Thermos.

Thermos was sold to Nippon Sanso Corp. of Japan for $134 million in 1989. Sanso also manufactured its own premium-priced thermoses, which would later be sold under the Nissan Thermos brand name.

To outsiders, the deal could look like a conglomerate detour. But the logic was hiding in plain sight: cryogenics and vacuum technology. Industrial gas handling is built on controlling extreme temperatures and preventing unwanted heat transfer. Vacuum insulation is the same problem, packaged for consumers.

In fact, Nippon Sanso had already proven the connection. In 1978, it succeeded in developing the world’s first stainless steel vacuum bottle. So when it acquired Thermos, it wasn’t randomly buying a consumer brand—it was taking a globally recognized name and pairing it with technical capabilities it already had.

The acquisition also had a global dimension. In 1989, the Thermos operating companies in Japan, the UK, Canada, and Australia were acquired by Nippon Sanso K.K. Later, Taiyo Nippon Sanso also acquired Thermos GmbH in Langewiesen, Germany, which still held 15 original patents. That part of the Thermos story had been stuck behind the Iron Curtain since 1945, but German reunification opened the door to foreign investment.

By the end of 1989, Nippon Sanso wasn’t just a domestic industrial gas supplier anymore. It had planted a flag in the U.S. through Matheson—especially valuable in specialty and electronics gases—and it had taken control of a consumer business with real technical synergy in Thermos.

The timing, however, was brutal. Japan’s bubble economy was about to burst, and the country would enter the long stagnation of the “lost decades.” If Nippon Sanso wanted to keep growing—and turn those 1989 bets into a true global platform—it would need to get even more strategic about scale, consolidation, and eventually, partners with deeper pockets.

V. The Merger That Reshaped Japan: Taiyo Nippon Sanso (2004)

The 1990s were brutal for Japanese business. When the bubble burst, asset prices cratered, banks were buried under bad loans, and deflation seeped into the economy. The model that looked unstoppable in 1989 suddenly looked fragile.

For Nippon Sanso, that meant something very specific: the home market stopped being a growth engine. But in an industry defined by massive fixed costs, that also created an opening. When demand flattens, scale matters more. Smaller gas companies feel the squeeze first, because you can’t “right-size” an air separation unit. The economics push everyone toward the same conclusion: consolidate or fall behind.

That’s exactly what happened in 2004. Nippon Sanso Corporation merged with Taiyo Toyo Sanso Co., Ltd., and the combined company took a new name: Taiyo Nippon Sanso Corporation. The merger officially took effect on October 1, 2004.

The logic was straightforward and powerful. It brought together Japan’s two biggest industrial gas players into a single domestic champion with national coverage, deeper customer relationships, and a distribution network no remaining local competitor could match. The combined company held around 40% of Japan’s industrial gases market, and the competitive dynamics at home shifted overnight.

After the merger, the playbook was consistent: build capability and extend the footprint through targeted acquisitions.

In Japan, the company moved to strengthen specific product lines. In 2007, it integrated Japan Carbonate Co., Liquefied Carbon Dioxide Co., Ltd., and related carbon dioxide operations under Japan Liquid Charcoal Holdings.

Internationally, the focus was on expanding the platforms it already had. In the U.S., its Matheson Tri-Gas subsidiary kept rolling up regional assets and capacity. Matheson acquired additional air separation units in 2004, then added businesses including Linweld in 2006, Polar Cryogenics in 2007, and a string of smaller acquisitions through 2008 and 2009—culminating in the purchase of Valley National Gases in 2009 and ETOX in 2009.

Beyond the U.S., Taiyo Nippon Sanso pushed deeper into Asia. In 2010, it acquired a majority stake in K-Air Specialty Gases, marking the start of operations in India and agreeing to build its first air separation unit there. In 2012, it acquired Leeden Ltd. to establish a stronger base in Malaysia and Singapore.

Step by step, each deal did one of three things: add geography, add customers, or add technical capability. And in a business where route density, installed infrastructure, and long-term relationships compound over time, that’s how you build a durable platform when organic growth is limited.

But there was still a ceiling. Even as Taiyo Nippon Sanso got bigger and more global, it was competing in an oligopoly against companies with vastly larger balance sheets—Air Liquide, Linde, and Air Products. It could win plenty of tactical battles, but the biggest prizes would increasingly require a different kind of firepower.

That’s where the story turns next. In 2014, Taiyo Nippon Sanso found the strategic partner that would change what it could realistically attempt—and what it could win.

VI. Inflection Point #1: Joining the Mitsubishi Keiretsu (2014)

On 13 May 2014, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings announced an agreement for Taiyo Nippon Sanso to become an affiliate of Mitsubishi Chemical, a core company within the Mitsubishi group. Mitsubishi Chemical later increased its stake in Taiyo Nippon Sanso to 50.5%. On November 12, 2014, Taiyo Nippon Sanso became a consolidated subsidiary of Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings.

This wasn’t just a shareholder reshuffle. It was a strategic unlock.

To see why, you have to understand what “Mitsubishi” actually means in Japan. The Mitsubishi keiretsu is one of the most powerful business networks in the country—spanning banking, trading, automotive, electronics, real estate, and heavy industry. Its roots go back to 1870, when Yataro Iwasaki founded a shipping company that grew into a modern conglomerate.

For Taiyo Nippon Sanso, joining that orbit changed three things at once.

First: balance sheet. Industrial gases is an infrastructure game, and infrastructure gets expensive fast. Competing for major assets against Air Liquide, Linde, and Air Products isn’t just about operational capability—it’s about firepower. With Mitsubishi behind it, Taiyo Nippon Sanso could credibly pursue far larger international M&A than it ever could as a standalone mid-sized Japanese champion.

Second: adjacency. Mitsubishi’s footprint in chemicals, electronics materials, and pharmaceuticals lined up neatly with the places where industrial gases matter most. Gases are essential inputs in chemical production. Electronics-grade gases sit at the heart of semiconductor manufacturing. Medical gases are foundational to healthcare. The relationships were already there; now Taiyo Nippon Sanso could plug into them.

Third: credibility. In big cross-border deals—especially in industries where customers and regulators care deeply about safety and continuity—who you are matters. Showing up as part of the Mitsubishi Group signaled permanence, capital strength, and long-term commitment.

The effects showed up quickly in deal activity.

In 2014, it acquired Continental Carbonic Products, Inc.

In 2013, MATHESON acquired Continental Carbonic Products Inc., an Illinois-based manufacturer and supplier of dry ice and liquid carbon dioxide operating 31 branch locations and eight production facilities. The deal made the company the largest independent supplier of dry ice in the United States.

And the pace only picked up from there. Across 2015 and 2016, Taiyo Nippon Sanso pushed into Thailand and Australia, and added deals in China and the United States. The company was no longer just waiting patiently for good opportunities to wander by—it was deliberately assembling a global platform.

Still, the biggest moment enabled by the Mitsubishi tie-up hadn’t arrived yet. That came in 2018, when the Linde–Praxair merger triggered regulatory divestitures—a once-in-a-generation opening. And this time, Taiyo Nippon Sanso would have the backing to act.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The European Transformation (2018)

In industrial gases, truly era-defining moments are rare. 2018 was one of them.

That’s when Germany’s Linde AG and America’s Praxair combined to form Linde plc—an all-out behemoth that would sit at the top of the industry. Praxair itself traced its roots back to 1907 in the U.S., originally founded as Linde Air Products Company. Put the two together, and you didn’t just get another merger. You got the world’s largest industrial gas company by a wide margin.

But a merger that big can’t happen on ambition alone. It needs regulators to sign off. And in Europe in particular, regulators demanded divestitures: if Linde and Praxair wanted to become one, they had to sell off meaningful chunks of overlapping businesses.

This is where Taiyo Nippon Sanso saw the opening.

Praxair agreed to divest the majority of its European businesses to Taiyo Nippon Sanso Corporation for 5 billion euros (around $5.83 billion) in cash, contingent on the Praxair–Linde merger closing and the necessary regulatory approvals. In other words: the deal only existed because regulators forced it into existence.

Yujiro Ichihara, President and CEO of Taiyo Nippon Sanso, framed it in exactly the terms you’d expect from a company that had been waiting decades for a shot like this: “With this acquisition, we are seizing a unique opportunity to enter the European market and establish a truly global footprint through the purchase of highly attractive assets in all the key geographies in the European Union. We look forward to growing these highly profitable businesses and welcoming the experienced and dedicated Praxair European team to TNSC.”

The subtext was even more important than the quote. Before 2018, Taiyo Nippon Sanso was still, in global terms, Japan-first—strong at home, meaningful in the U.S. through Matheson, and expanding across Asia-Oceania. Europe, the world’s other major industrial hub, was the missing pillar. This deal didn’t just add a region. It completed the map.

On July 5, 2018, Taiyo Nippon Sanso signed the share purchase agreement to acquire Praxair’s European businesses. The scope was broad: industrial gas operations across Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Belgium; carbon dioxide businesses in the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, and France; plus helium-related businesses.

The acquisition price was €4,913m, approximately ¥634.7bn and $5,559m.

And the size wasn’t just headline-grabbing—it was transformative. The acquired businesses generated about $1.52 billion in annual sales in 2017 and came with around 2,500 employees. Taiyo Nippon Sanso wasn’t buying a small beachhead. It was buying a working European platform: customers, plants, routes, and people who already knew how to run the machine.

One particularly strategic element was helium. Helium shows up in high-value, hard-to-substitute applications like MRI machines and semiconductor manufacturing. And as global supplies grew tighter and more constrained, having helium operations wasn’t just about incremental revenue—it was about positioning and supply security.

Taiyo Nippon Sanso made clear the deal depended on the Praxair–Linde merger closing. It also said it would fund the acquisition with cash on hand and loans, with no plans for equity financing. That choice only makes sense in context: Mitsubishi ownership had expanded what the company could borrow and, just as importantly, made it believable that it could absorb a deal of this size.

By December 2018, the acquisition was complete. And just like that, Taiyo Nippon Sanso went from “global, but not really” to something much closer to a peer of the Western giants: a four-hub industrial gas company spanning Japan, the United States, Europe, and Asia-Oceania.

VIII. The Modern Company: Global Architecture (2020-Present)

In 2020, the company renamed itself Nippon Sanso Holdings Corporation and shifted to a holding company structure.

That change wasn’t just a new name on the letterhead. A holding company model gave NSHD a cleaner way to run what it had become after 2018: a genuinely global set of businesses with different customers, different regulators, and different competitive realities—while still steering them toward one strategic direction.

Operationally, the group is organized into five segments: Japan Gas, United States Gas, Europe Gas, Asia and Oceania Gas, and Thermos.

Each segment runs as a real business, with its own management team and operating priorities. The holding company sits above them, allocating capital, setting targets, and making sure the whole system moves together.

Japan remains the anchor. Under the Taiyo Nippon Sanso brand, the company is a leading manufacturer with around a 40% share of the Japanese industrial gases market, supplying safe, reliable, high-quality industrial gases nationwide—building on capabilities it has been developing since 1910.

In the United States, the engine is Matheson Tri-Gas, Inc. Headquartered in Irving, Texas, Matheson supplies industrial gases, medical gases, specialty and electronic gases, propane, and a wide range of gas-handling equipment and services. It operates at scale, with more than 300 retail, plant, and warehouse locations across the country, and it serves customers through every major delivery model: cylinders, bulk, and pipeline.

Matheson’s U.S. footprint is built around a large production and distribution base that includes dozens of air separation units, helium transfill sites, acetylene plants, nitrous oxide plants, carbon dioxide plants, and hundreds of retail facilities, depots, fill plants, and manufacturing sites.

In Europe, the former Praxair assets now fly a new flag: Nippon Gases. The business stretches from Scandinavia to the Iberian Peninsula and operates across 14 countries. It’s one of the leading industrial and medical gas companies in the region, with over 3,400 employees, serving more than 150,000 customers and over 390,000 homecare patients.

Across Asia-Oceania, NSHD has built a footprint spanning India, Southeast Asia, China, and Australia—positioning itself in the fastest-growing industrial region in the world, where new manufacturing capacity and infrastructure continue to drive demand.

And then there’s Thermos—the consumer-facing business that still looks unusual inside an industrial gas portfolio, but fits the group’s deeper technical roots in cryogenics, insulation, and precision manufacturing. Thermos K.K. has production bases in Malaysia, China, and the Philippines, plus a sales subsidiary in South Korea and affiliated companies in places including China, the United States, and Germany. Through these regional hubs, it ships vacuum-insulated bottles and other household products to more than 120 countries.

By March 31, 2025, Nippon Sanso Holdings reported trailing 12-month revenue of $8.58B and a total workforce of 22,202 employees.

For the fiscal year from April 1, 2024 to March 31, 2025, the company reported positive profit growth despite a challenging macro environment. Shipment volumes of core air separation gases—oxygen, nitrogen, and argon—held steady year over year, while overall group shipment volumes dipped slightly. The bigger story was execution: disciplined price management helped absorb cost pressure, and ongoing productivity initiatives continued to lift operational efficiency and financial performance.

The most telling move, though, wasn’t in the income statement. It was in identity.

Nippon Sanso Holdings announced it would unify the brand and logo for its industrial gas business globally and roll out the change in stages. Until now, the group operated around the world with a shared symbol mark but region-specific branding. To raise recognition as a single global player—among customers, regulators, employees, and investors—and to support sustainable growth, it decided to standardize the industrial gas businesses under one name: NIPPON SANSO, with a globally consistent logo.

Announced in 2025 and planned for implementation starting in April 2026, the rebrand is a signal that the integration arc that accelerated with the 2018 European acquisition is reaching its logical endpoint. NSHD isn’t content to be a collection of strong regional subsidiaries with different names. It wants to show up everywhere as one company—one platform—operating at global scale.

IX. Semiconductor & Electronics: The High-Margin Future

If there’s one storyline that explains where Nippon Sanso Holdings wants to go next, it’s electronics—specifically, the semiconductor supply chain that now sits at the center of global industrial policy.

The group has been explicit about it: under its NS Vision 2026 plan, expanding the electronics business is a priority. And the push is being led primarily by Taiyo Nippon Sanso, the Japan-based operating company that’s seeing strong demand from semiconductor customers.

The reason is simple, and a little mind-bending. Semiconductor manufacturing doesn’t just require clean rooms. It requires clean everything. The air, the piping, the valves, the storage vessels, the delivery systems—and the gases themselves. In deposition, etching, and doping, these gases aren’t “inputs” so much as they are part of the process physics. And the tolerances are brutal: impurities at tiny levels can ruin wafers, waste expensive tool time, and shut down production.

That’s why this niche commands premium economics. The global semiconductor specialty gas market was valued at about $11.5 billion in 2024 and is expected to grow to roughly $24.2 billion by 2034—driven by more fabs, more complexity, and more demand for the highest-purity materials.

Nippon Sanso comes into this with real heritage. Its U.S. subsidiary, Matheson, has deep roots in semiconductor gases going back decades. In 1981, Matheson became the first commercial producer of silane, earning a “Semmy” Award from the Semiconductor Equipment and Materials Institute. That early credibility mattered: in semiconductors, once you’re qualified and trusted, you don’t get swapped out lightly.

And the company’s electronics ambition isn’t limited to molecules in a cylinder. Taiyo Nippon Sanso positions itself as a full-solution provider for the silicon and compound semiconductor worlds. It supplies gases, mixture gases, and related liquid and solid materials with demanding specifications—high purity, tight tolerances, and customer-specific requirements. It also provides the systems around the gases: purification, handling, and the equipment that makes a fab-grade supply safe and reliable.

That “whole stack” approach is the point. Commodity gases can be a scale game. Electronics gases are a capability game. When you’re not just delivering product, but designing and supporting the supply system that feeds a fab, you move from vendor to embedded partner—and the relationships get stickier and the margins get better.

Zoom out, and the tailwind is hard to miss. AI is pulling forward demand for advanced chips. Governments are subsidizing domestic manufacturing for resilience and national security. New fabs are being built across Asia, the United States, and Europe—and every one of them needs ultra-high-purity gases and sophisticated delivery infrastructure from day one.

That’s the strategic appeal for NSHD. The bulk industrial gas business is the steady foundation: long contracts, predictable cash flow, infrastructure economics. Electronics is the higher-growth layer on top—where technical differentiation, qualification cycles, and customer lock-in can turn “air, separated” into one of the most valuable materials in the modern economy.

X. Sustainability & Future Positioning: Hydrogen and Beyond

Semiconductors may be the high-margin headline, but NSHD is also building for a second, slower-moving wave: the energy transition, and the way it will reshape what heavy industry needs from its gas suppliers.

To frame that push, the company laid out a medium-term management plan called “NS Vision 2026 – Enabling the Future,” covering fiscal years 2023 through 2026. The plan focuses on five priorities: sustainability management, exploring new businesses toward carbon neutrality, total electronics, operational excellence, and DX initiatives.

Hydrogen sits near the center of that “carbon neutrality” ambition, and for good reason. For industrial gas companies, hydrogen is one of the biggest long-term prize pools on the board. Today, hydrogen is largely used in refining and chemicals, and much of it is produced from coal or natural gas—meaning it comes with significant CO2 emissions. The promise of low-emissions hydrogen—produced with renewable or nuclear power, or paired with carbon capture— is that it can decarbonize sectors where electrification is difficult, like heavy industry and long-distance transport.

In industries like steelmaking, chemicals, refining, electronics, power generation, and glass, hydrogen can function as a practical path toward lower emissions. It can fully replace natural gas in some combustion processes, or it can be introduced gradually through blending systems that allow plants to start reducing carbon without redesigning everything overnight.

NSHD is trying to make itself useful in that future by staying close to the projects where decarbonization becomes real infrastructure.

In the U.S., its operating company Matheson entered into a gas supply agreement with 1PointFive to provide oxygen for the carbon capture, utilization, and sequestration company’s first Direct Air Capture (DAC) plant in Texas. Matheson plans to invest in and establish an air separation unit to supply oxygen to “Stratos,” 1PointFive’s DAC plant under construction in Ector County. The oxygen is used in the DAC process to help produce a pure stream of CO2, which is then sequestered in geologic reservoirs. Stratos is expected to begin operations in mid-2025 and, when fully operational, capture up to 500,000 tons of CO2 per year—positioned as the world’s largest DAC plant.

In India, Matheson received an award to supply hydrogen and co-product steam for 20 years to Numaligarh Refinery Limited (NRL), a public sector affiliate of the Government of India. Under the arrangement, Matheson will invest in and establish a large, multi-feed hydrogen plant to supply up to 132 kNm3/hr (285 tons/day) to NRL’s refinery units at Numaligarh in Assam.

Alongside energy transition projects, NSHD also has a steadier growth engine: medical gases. Aging populations and expanding healthcare capacity globally continue to support demand for oxygen therapy, anesthesia gases, and related medical applications—business that tends to be stable and complements the cyclicality of heavy industry.

Put it together, and you get the next chapter of the strategy. NSHD wants the durability of classic industrial gases—long contracts, embedded infrastructure, high switching costs—while layering in exposure to secular growth themes like semiconductors, hydrogen, carbon capture, and healthcare.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

At this point in the story, the question isn’t whether Nippon Sanso Holdings is “important.” It clearly is. The real question is what kind of competitive environment it operates in—and whether the advantages we’ve been describing are structural, or just the result of good execution.

Two frameworks help make that concrete: Porter’s Five Forces for industry structure, and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers for durable competitive advantage.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Industrial gases looks simple until you try to start one.

To compete in bulk supply, you need to build air separation units—projects that require huge upfront capital. Then you need the physical distribution system: trucks, depots, filling stations, cylinder handling, maintenance, and safety infrastructure. And beyond the hardware, you need the hardest part: years of operational credibility. Customers don’t “trial” a new gas supplier the way they might trial a new software tool. Safety and uptime are existential.

Specialty gases can require less heavy plant investment than bulk, but the barrier just moves. You’re now competing on chemistry, purification, packaging, and qualification cycles with customers who may take months—or years—to approve a new supplier. Either way, the door is mostly closed.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For the core atmospheric gases, the main input is air. It’s free, and nobody can corner it.

The meaningful cost input is energy, especially electricity to run the separation process. But the industry’s contracts are typically built to handle this, with energy pass-through provisions that reduce margin volatility when power prices spike.

In specialty gases, the input chemicals and precursors matter more. But scale becomes its own advantage here: the major players buy more, negotiate better, and tend to have more resilient supply chains.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Buyers care about two things: reliability and safety, and the total cost of ownership.

The gas bill is rarely what keeps an operations manager up at night. The real fear is downtime—ruined wafers, halted steel production, disrupted hospital care. That makes customers surprisingly insensitive to small price differences, because the cost of failure is so much larger than the cost of supply.

That said, large industrial customers do have leverage at the point of negotiation, especially for new contracts. But once the supplier’s infrastructure is installed—pipelines, on-site units, integrated controls—the leverage shifts. Switching becomes expensive, slow, and risky. Smaller customers, meanwhile, are fragmented and usually served by local oligopolies, which limits their negotiating power.

4. Threat of Substitutes: VERY LOW

There’s no substitute for oxygen in steelmaking, nitrogen in semiconductor manufacturing, or argon in welding. These aren’t optional materials; they’re the process.

That creates near-perfect inelasticity. Demand may fluctuate with industrial cycles, but the underlying need doesn’t go away.

5. Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-LOW (Oligopolistic)

This is an oligopoly, and it behaves like one.

The market is dominated by five global players: Air Liquide, Linde, Air Products, Messer, and Nippon Sanso Holdings. Together, they control the vast majority of global share. Linde, Air Liquide, and Air Products sit at the very top, with a combined position that’s difficult for anyone else to match.

The result is an industry where pricing is typically disciplined. Price wars would be self-inflicted damage: everyone has high fixed costs, everyone has long-lived assets, and nobody benefits from racing to the bottom. Even during downturns like 2008–09, the leaders held margins better than you’d expect from something that, at first glance, looks “commoditized.”

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Industrial gases is built for scale.

Air separation units are capital-heavy, but once built, the incremental cost of supplying additional volume is low. Profitability is highly sensitive to utilization: fill the plant, and the economics compound.

Scale also shows up in distribution—denser route networks cut delivery costs—and in corporate advantages like shared procurement and R&D across a global footprint.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

There aren’t classic network effects here; one customer doesn’t inherently make the product better for another.

But there is something adjacent: integration depth. As the gas supplier becomes more embedded in a customer’s operations—pipelines, controls, safety systems, engineering support—the relationship becomes harder to unwind. The “network” is really an ecosystem of installed infrastructure and operating routines.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

The business models of the major players are broadly similar. There isn’t a disruptive new entrant with a fundamentally different approach that incumbents can’t copy without harming themselves. Advantage comes more from execution and footprint than from a radically different playbook.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

This is one of the industry’s defining powers.

On-site plants and pipelines create physical lock-in. Safety certifications, process integration, and supply contracts add layers of friction. And in electronics and specialty gases, qualification cycles can take so long that switching suppliers isn’t just costly—it can be operationally unrealistic on a meaningful timeline.

5. Branding: MODERATE

In the core gas businesses, brand is secondary to reliability and safety. Customers don’t buy oxygen because the logo looks good; they buy because the oxygen shows up, every time, without incident.

But NSHD is unusual because it also owns Thermos, a consumer brand with real global recognition. That doesn’t drive the industrial gas moat, but it does mean the group has an island of true consumer brand power inside a mostly invisible B2B empire.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

There isn’t one single resource that only Nippon Sanso possesses. But the accumulated assets—technical know-how, long-term customer relationships, and installed infrastructure—function like a resource that’s very difficult to replicate quickly.

Helium adds another layer here. With global helium supply constrained, having helium-related operations can create real advantage in availability and reliability for high-value end uses.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

This is a business where decades of operational learning matters.

Running plants safely, maintaining purity standards, designing delivery systems, managing logistics, preventing incidents—these are process-driven advantages that improve over time and are hard to transplant. They matter even more in specialty and electronics gases, where process capability directly determines whether you can meet customer specifications at all.

Key KPIs for Monitoring Performance

If you’re tracking Nippon Sanso’s performance from here, two metrics tell you the most, the fastest:

1. Core Operating Margin by Segment: This is the clearest read on pricing discipline, cost control, and whether each geographic hub is getting stronger.

2. Electronics Segment Revenue Growth: NSHD is explicitly positioning electronics as its premium growth engine. This metric is the scoreboard for whether that strategy is actually translating into momentum in its highest-value market.

XII. Bull Case and Bear Case

Bull Case

If you’re building the bull case for Nippon Sanso Holdings, it starts with a simple idea: this company sits inside one of the best-structured industries on the planet.

Industrial gases is an oligopoly. A small handful of players control the vast majority of global share, and the product is so essential—and so operationally embedded—that customers mostly optimize for reliability and safety, not the last basis point of price. That combination of concentration, mission-critical demand, and high switching costs tends to produce something rare in industrial businesses: pricing discipline and margin stability.

The second pillar is the electronics and semiconductor tailwind. As fabs proliferate and processes get more complex, the need for ultra-high-purity gases and tightly engineered delivery systems rises with them. The specialty gas market for semiconductors was about $11.5 billion in 2024 and is expected to roughly double over the next decade. Nippon Sanso has legitimate right-to-win here: Matheson brings deep semiconductor heritage, and Taiyo Nippon Sanso’s capabilities in advanced electronics applications, including MOCVD-related technologies, position the group to benefit as that demand compounds.

Third, there’s the next wave of industrial demand: hydrogen and carbon capture. These are still early markets, but they’re the kind of markets industrial gas companies are built for—long-lived projects, infrastructure-heavy, and anchored by long-term contracts. NSHD’s oxygen supply contract supporting a Direct Air Capture plant and its long-term hydrogen supply award in India are signals that it’s already placing chips on the table.

Fourth is the Mitsubishi relationship. Being inside the Mitsubishi orbit doesn’t just add a nameplate—it adds credibility, relationships across industrial Japan and beyond, and the balance sheet flexibility to pursue meaningful M&A when assets become available.

Finally, there’s Thermos. It’s small compared to the gas empire, but it adds diversification and a consumer-facing profit stream with global reach—plus it reinforces the group’s technical roots in insulation, materials, and cryogenics.

Bear Case

The bear case is less about whether industrial gases is a great business, and more about whether Nippon Sanso can consistently win against even bigger, better-capitalized rivals.

The first concern is scale. NSHD is meaningfully smaller than the top tier—Linde, Air Liquide, and Air Products. In 2023, Linde had about 66,000 employees and nearly $33 billion in revenue, while Air Liquide and Air Products reported sales of about €29.4 billion and $12.6 billion, respectively. At roughly $8.6 billion in revenue, Nippon Sanso is closer to a quarter of Linde’s size than a true peer. In a capital-intensive, R&D-driven industry, scale can translate into lower costs, broader customer access, and faster innovation.

Second, despite the European expansion, Japan still represents a large part of the mix. And Japan isn’t an easy backdrop: an aging population and a mature, slower-growth economy can limit the pace of domestic demand expansion.

Third is energy. Air separation is power-hungry by nature. Contracts often include pass-through mechanisms, but energy volatility can still create real earnings noise—especially when markets move faster than contract structures can absorb.

Fourth, electronics is attractive precisely because it’s hard—and it’s cyclical. The long-term trajectory is compelling, but semiconductor downturns can compress volumes and delay customer projects in the short term, putting pressure on the segment NSHD most wants to grow.

Fifth, there’s execution risk in global integration. Bringing together disparate regional operations under a unified brand and operating approach is difficult in any industry; doing it in a safety-critical, regulator-heavy infrastructure business is even harder. The planned 2026 brand transition is strategically sensible, but it adds complexity during the rollout.

Layer on top of all that the macro uncertainty the company itself flagged—geopolitical risk, trade tensions, energy volatility, inflation, and potential tariff changes under the new U.S. administration—and the near-term operating environment can still surprise you in ways the long-term thesis doesn’t fully capture.

XIII. Conclusion: The Gas Professionals

From a small oxygen producer founded in the final years of the Meiji era to a global industrial gas company with real scale across four regions, Nippon Sanso Holdings’ story is what patient advantage-building looks like in the real economy.

Since its foundation as Nippon Sanso Ltd. in 1910, the group has framed its mission the same way: creating social value through gas solutions that raise industrial productivity, support human well-being, and contribute to a more sustainable future. Internally, it calls its people “The Gas Professionals,” united around a simple goal: “Making life better through gas technology.”

What’s striking is how unflashy the path was. There was no single invention that changed everything. No sudden reinvention into something else. Instead, the company compounded—decade after decade—through consistent execution, disciplined capital allocation, and opportunistic M&A when the industry presented openings. Thermos in 1989. A U.S. platform through Matheson. A domestic reshaping merger in 2004. The balance-sheet unlock of Mitsubishi in 2014. And then the defining leap into Europe in 2018, when regulators forced the market to make room.

The result is the company we see today: the Nippon Sanso Holdings Group as the world’s fourth-largest supplier of industrial, electronic, and medical gases, operating across Japan, the U.S., Europe, and Asia & Oceania, covering more than 30 countries and regions.

For long-term fundamental investors, the appeal is not mystery—it’s structure. Industrial gases is one of those rare businesses where essential demand meets high switching costs and rational competition, and where long-term contracts turn infrastructure into cash flow. NSHD adds a second layer: real optionality. Electronics gases align with the semiconductor build-out. Hydrogen, carbon capture, and medical gases align with the energy transition and aging societies. Those themes can grow without breaking the core durability of the business.

As the company itself put it: “This evolution demonstrates the growing momentum and power of the Nippon Sanso brand across the continents and our Team's focus on delivering the same safe, high quality, value-added products and services in support of our Customers worldwide.” Founded in 1910, Nippon Sanso carries more than 115 years of experience in gas technologies that enhance industrial productivity and human well-being. The name and logo will evolve as the group unifies globally, but the operating promise stays the same: safety, reliability, and continuous improvement.

The next chapter is being written now—in semiconductor fabs across Asia, hydrogen plants in India, direct air capture facilities in Texas, and in everyday industrial operations where the most important inputs are the ones you never see. Whether Nippon Sanso can pull off deeper global integration, keep winning in electronics, and secure a durable role in the energy transition will determine whether the next 115 years are as consequential as the first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music