Ibiden: The 112-Year-Old Power Company That Became Nvidia's Secret Weapon

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

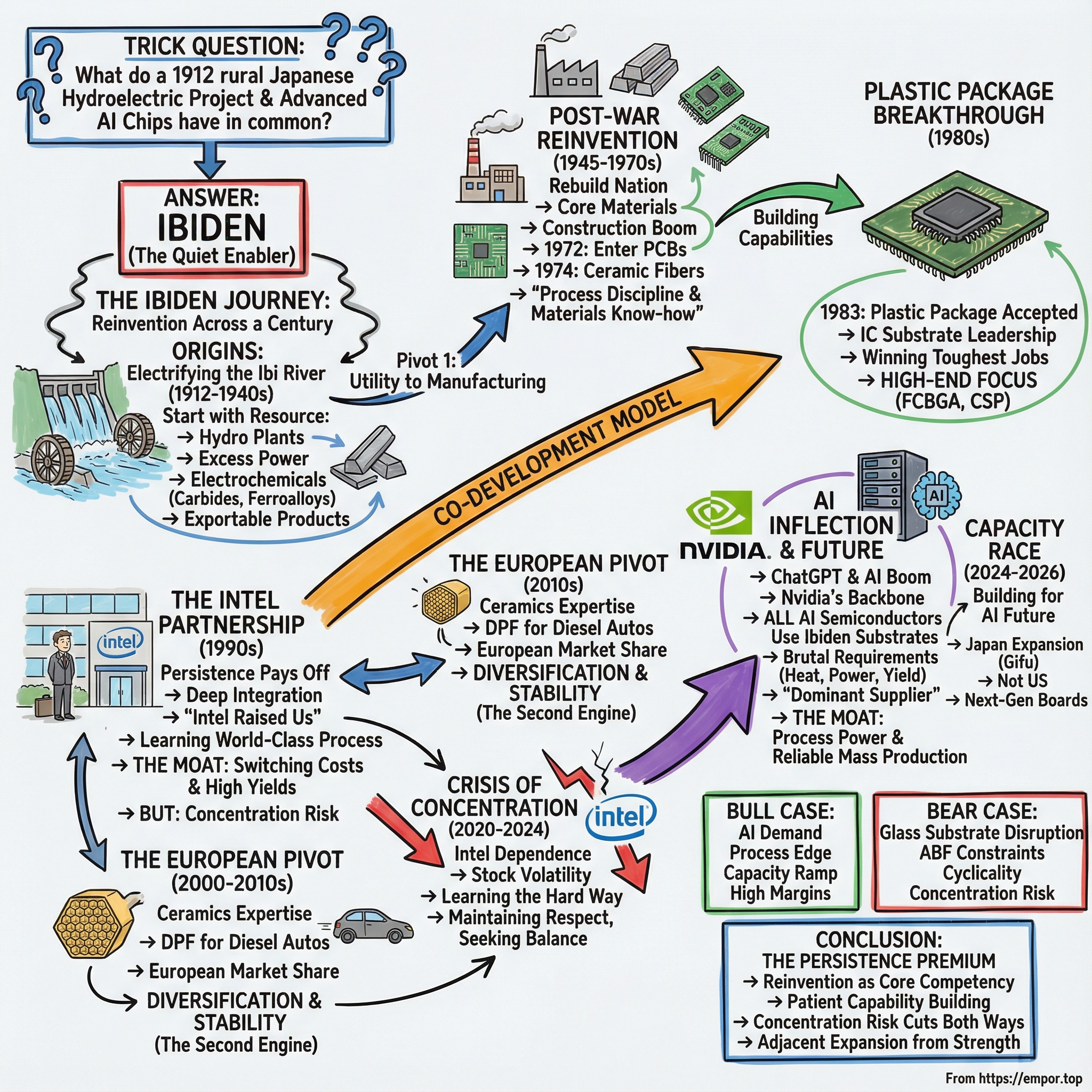

What do a rural Japanese hydroelectric project from 1912 and the most advanced AI chips in the world have in common? The answer is a company most people have never heard of—and yet, without it, a lot of the AI boom of the last couple of years simply wouldn’t have been able to ship.

All of Nvidia’s AI semiconductors now use Ibiden’s substrates. Let that land for a second. A company that began life more than a century ago as an electric power business in a landlocked Japanese prefecture is now a critical enabler of Jensen Huang’s empire. And it’s not a quiet, “maybe someday” role either: CEO Koji Kawashima has said customers are buying essentially everything Ibiden can make, and he expects that demand to hold at least through next year.

Ibiden’s timeline reads like industrial fiction. It starts with electrifying rural communities. It runs through world wars and Japan’s postwar boom. It detours into cleaning up diesel emissions. And then, somehow, it ends up inside the hottest corner of modern computing—helping power the data centers behind tools like ChatGPT, Google’s search systems, and Tesla’s self-driving efforts.

Of course, once an unglamorous but essential chokepoint like this becomes visible, competitors show up. Taiwanese players such as Unimicron Technology Corp. are eyeing the same prize. But as Toyo Securities analyst Hideki Yasuda points out, breaking Ibiden’s grip won’t be easy. The moat isn’t just “we built a factory.” It’s decades of co-development with the best chipmakers in the world, process know-how that drives high manufacturing yields, and a kind of patient persistence that turns long shots into inevitabilities.

So that’s the episode: how does a 112-year-old company put itself at the center of the most important technology wave of our time? The answer runs through a legendary perseverance story, a hard-earned lesson about relying too much on one customer, and a bet that old-world materials expertise would matter in the age of AI.

II. Origins: Electrifying the Ibi River Valley (1912–1940s)

Picture rural Gifu Prefecture in 1912: mountainous, inland, and struggling. Japan was industrializing fast, but that progress mostly flowed around this corner of central Honshu. No major ports. Limited access to raw materials. Not many obvious ways to build an economy.

What Gifu did have was water—cold, fast-moving water pouring out of the mountains and down the Ibi River valley.

In that setting, Ibigawa Electric Power Co., Ltd. was founded in 1912. Its first president was Yujiro Tachikawa, a businessman from nearby Ogaki City. And whether he would have described it this way or not, Tachikawa set a pattern Ibiden would repeat for the next century: start with the resource you actually have, then engineer your way into something the world will pay for.

The timing could not have been worse. The company launched during a recession. Then World War I broke out, and the water wheels it had ordered from Germany suddenly weren’t coming. So the team did the only thing it could do. They raised money wherever they could, adopted a vertical-axis water wheel produced domestically for the first time in Japan, and pushed ahead with construction in an era with no heavy equipment and essentially no automotive infrastructure to lean on.

This is the kind of founding story that survives because it’s true—and because it becomes a cultural template. When the plan breaks, don’t pause. Rebuild the plan.

In 1916, Ibiden completed its first hydroelectric facility, the Nishi-Yokoyama Power Plant, upstream along the Ibi River. More plants followed as the company expanded generation capacity: Higashi-Yokoyama in 1921, Hirose in 1925, Kawakami in 1935, and Nishidaira in 1940.

But there was a catch. Producing electricity is only half the problem; someone has to use it. Hydropower can’t easily “save” surplus output for later, and the surrounding rural economy couldn’t absorb everything those new turbines produced. Excess electricity wasn’t just inefficiency—it was an existential problem.

And it triggered Ibiden’s first great pivot.

Because some water channels couldn’t be adjusted, the company couldn’t smoothly match supply to demand. So, like other hydroelectric operators in Japan, it moved into electrochemical manufacturing—businesses that could soak up power reliably and continuously. Ibiden began producing carbides, taking advantage of nearby lime production areas. Tachikawa then pushed further into ferroalloys and carbon products. In 1918, the company even renamed itself Ibigawa Electrochemical Co., Ltd.—a signal that it no longer thought of itself as “just” a utility.

The logic was simple and brutal: if the region couldn’t consume the electricity, the company would turn that electricity into exportable products.

One early win was carbon used in searchlights. By finding a real outside market—especially one tied to military demand—the company proved it could convert local hydropower into nationally strategic manufacturing.

The years between the wars were not gentle. Japan endured the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, then financial turmoil and the Great Depression. After repeated crises, Ibiden was placed under the umbrella of Toho Electric Power Co. and later Dainippon Spinners Co., Ltd., as part of a broader management restructuring.

Then geopolitics turned into policy. As Japan entered the second Sino-Japanese War, the government moved to control electric power. In 1942, Ibiden contributed two of its five power plants to a company overseeing Japan’s electricity system. With power generation pulled under state management, Ibiden effectively exited the power supply business and continued on as an electrochemical manufacturer.

In 1940, the company changed its name again—to Ibigawa Electric Industry Co., Ltd. It was the end of the first chapter: the company that began by electrifying a river valley was now, unmistakably, a manufacturing business.

But the most important inheritance from these decades wasn’t a specific product line. It was a way of operating: vertical integration as instinct, comfort with hard engineering problems, and a willingness to pivot without losing the thread of what the company was actually good at. Those traits would become the throughline that carried Ibiden from hydro plants to high-temperature materials—and, eventually, into the semiconductor supply chain.

III. Post-War Reinvention: From Reconstruction to Diversification (1945–1970s)

Japan in 1945 was shattered. Factories were damaged, supply chains were broken, and the country’s priorities were brutally simple: rebuild, rehouse, restart. For a manufacturing company in landlocked central Japan, there was no obvious playbook—only the reality that if you wanted to survive, you had to make what the country needed next.

Ibiden did exactly that. In the postwar years it leaned into core industrial materials: carbides that went into cutting tools, ferroalloys that fed steelmaking, and melamine resins that found their way into construction products. None of this was glamorous. But it was foundational—and it fit Ibiden’s DNA. These were businesses where disciplined process control and materials know-how mattered, and where demand was tied directly to the reconstruction of an entire nation.

Then the ground shifted again. As Japan entered its high-growth era, housing and infrastructure demand surged. Ibiden expanded into building materials in 1960, riding the construction boom of the 1960s as cities swelled and new homes went up by the millions.

And then, in 1972, Ibiden made a move that, on the surface, looked like a hard left turn: it entered printed circuit boards.

Why would a company associated with furnaces, resins, and building products start making the guts of electronics? Because if you squint, it wasn’t a left turn at all. It was the same pattern as the original hydropower-to-manufacturing pivot: take what you’re already unusually good at—materials, heat, precision, repeatable process—and apply it to a market that’s about to get very big.

Electronics was that market. And PCBs were the platform.

A year later, in 1973, Ibiden developed a COB (Chip on Board) technology that allowed an IC chip to be mounted directly onto a printed wiring board. From there, it pushed into flip chip packages and even proposed their use for PC semiconductors because of their electrical performance. This is an early glimpse of what would later become Ibiden’s superpower: not just manufacturing to spec, but working alongside customers to move the spec forward.

In 1974, Ibiden added ceramic fibers—another materials business that didn’t look like electronics, but expanded the company’s capabilities in high-temperature, high-performance manufacturing. Decades later, that would matter far more than anyone in 1974 could have predicted.

This is also the era when Japan became the birthplace of modern IC substrate technology, including BT substrate, and early leaders like Ibiden, Shinko, and Kyocera emerged. Japan’s advantage wasn’t just that it had electronics companies. It was that it had companies that could actually manufacture these components to the standards the next generation of computing would require.

By the early 1980s, the transformation was obvious enough that the old identity no longer fit. The company that began as Ibigawa Electric Power Co., Ltd. adopted the name Ibiden Co., Ltd. in November 1982—short for “Ibigawa Denki,” Ibi River Electric. It was a nod to where it came from, not a description of what it was anymore. By then, Ibiden had become something else: a diversified materials and electronics manufacturer, built through a series of connected moves, each one extending the last.

And that’s the key takeaway from this period. Ibiden didn’t reinvent itself by jumping randomly from trend to trend. It built outward from strengths—process discipline, materials science, and a willingness to enter unglamorous but essential parts of the value chain—until, almost inevitably, it found itself positioned for the semiconductor age.

IV. The Plastic Package Breakthrough & Rise to IC Substrate Leadership (1980s)

By the early 1980s, the global semiconductor industry had a problem hiding in plain sight. Chips kept getting faster and more complex, but actually connecting them to the rest of the computer was becoming a bottleneck. The old approach—ceramic packages—worked, but it was expensive, and it didn’t scale gracefully as pin counts climbed.

The industry needed a cheaper, more scalable way to package chips without sacrificing performance. Ibiden’s opening was plastic.

In 1983, Ibiden’s plastic package was accepted by major IC makers worldwide. That moment mattered. It wasn’t just a new product; it was proof that Ibiden could manufacture at the quality levels semiconductor leaders demanded—and do it at production scale.

That’s harder than it sounds, because an IC package substrate has to do several jobs at once. It has to route signals between the chip and the circuit board. It has to survive heat—lots of it—over and over again, across thousands of thermal cycles. It has to protect the silicon from contamination and humidity. And it has to hold its shape while doing all of the above, because warping by even a tiny amount can ruin the entire assembly.

Underneath all that is the core physics problem that makes substrates a choke point in the first place:

Nanometer wiring on an IC chip does not directly interconnect with micrometer wiring on a printed wiring board. An IC package—essentially a high-precision board designed to sit between them—bridges those two worlds while also protecting the chip from dirt and humidity. It’s the translation layer between the nano-scale universe on silicon and the larger-scale world of the motherboard. Ibiden’s business was becoming that translation layer, and it kept building more value as chips improved.

Then the global industry shifted. As semiconductor manufacturing migrated to South Korea and Taiwan, the packaging substrate business moved with it. New competitors entered, scaled quickly, and went after the middle and low end of the market. Japanese companies, facing different cost structures, largely stepped back from commodity segments and concentrated on the hardest, highest-end products—things like FC BGA and FC CSP.

For Ibiden, that wasn’t a retreat. It was a bet: if you can win the toughest substrate jobs, customers will stick with you, because qualifying a new supplier is slow, expensive, and risky.

And the toughest substrate jobs sat under CPUs. CPU substrates are big, layered, high-density, tight-tolerance pieces of engineering. Get them right and you earn a reputation as a premium supplier. Ibiden did—and by doing so, it positioned itself for the next era.

Because once you’re a trusted high-end substrate partner, the next step isn’t just shipping parts. It’s co-developing the future with the company designing the chip. And that’s exactly what happened next, in a relationship that would define Ibiden for decades: Intel.

V. The Intel Partnership: The Story of Persistence (1990s)

In the semiconductor world, the origin story of Ibiden’s Intel relationship gets told like folklore. Not because it’s flashy—but because it’s so stubbornly, almost unbelievably human.

In the early 1990s, Koji Kawashima—who would later become Ibiden’s CEO—was seconded to Ibiden’s U.S. operation in Santa Clara. And instead of trying to win Intel with a pitch deck and a formal procurement process, he did something far simpler and far harder to fake: he showed up.

Day after day, Kawashima waited outside Intel’s offices and stopped engineers and executives as they came and went, asking for feedback on Ibiden’s products. Not once. Not for a week. Every day, over time, until “the Japanese substrate supplier down the street” turned into a real working relationship.

That persistence mattered because the timing was perfect.

Intel in the early 1990s was shifting to flip-chip Ball Grid Array (FCBGA) packaging for Pentium processors—a change that sounds incremental until you realize what it meant for suppliers. FCBGA enabled far higher pin counts than earlier approaches, which was essential as processors became more complex. But it also demanded better substrates: more layers, finer features, tighter tolerances, and stronger thermal performance, all produced at massive scale with extremely high yields.

Intel didn’t just need capacity. It needed a partner that could live inside its standards.

Ibiden became that partner. Over time, it wasn’t simply shipping parts to Intel; it was embedded in Intel’s product development loop. When Intel designed new processors, Ibiden engineers worked alongside Intel to make sure the packaging could actually deliver what the silicon promised. That co-development model is the real moat in substrates—because the substrate isn’t a generic component. The substrates, which help transmit signals from semiconductors to the circuit board, need to be tailored for each chip. And customers often consult with Ibiden early in development for exactly that reason.

Once a chip program is built around a particular substrate architecture, switching suppliers midstream is painfully expensive and risky. So the deeper Ibiden got into Intel’s roadmap, the harder it became to replace—creating powerful switching costs that protected Ibiden for years.

The upside was enormous. At one point, Intel accounted for roughly 70% to 80% of Ibiden’s chip package substrate revenue. That kind of concentration doesn’t happen unless a supplier becomes mission-critical. Intel effectively “raised” Ibiden’s substrate business—accelerating its learning curve, pulling it into increasingly demanding programs, and forcing it to industrialize leading-edge packaging techniques at scale.

But the same fact that made Ibiden formidable also made it fragile. When one customer dominates your economics, their stumbles become your stumbles. That vulnerability would show up much later, as Intel struggled through competitive and execution challenges and Ibiden’s exposure became a problem the market couldn’t ignore.

Kawashima has captured the duality neatly: “Intel raised us and opened doors,” he has said, while also emphasizing that “Intel will always remain an important customer.”

In retrospect, the deepest value of the Intel era wasn’t just revenue. It was capability. Years of working on leading-edge CPU packaging taught Ibiden how to build the exact kinds of substrates that the AI era would later demand: large, high-layer-count, high-precision boards that can handle brutal heat and signal integrity requirements. So when Nvidia’s GPUs became the center of gravity in computing, Ibiden arrived with something few others had: the process maturity to manufacture these substrates at scale, with yields good enough to matter.

For anyone trying to understand Ibiden today, this chapter is the key. Intel made Ibiden big. Intel also taught Ibiden what “world-class” actually means. And it left the company with a question it would eventually have to answer: how do you keep the benefits of deep partnership without letting customer concentration become destiny?

VI. The European Pivot: Diesel Particulate Filters & the Ceramics Renaissance (2000–2010s)

While semiconductors were turning Ibiden into a global specialist, another transformation was gathering momentum in the background—one that traced back to a decision the company made in 1974, when it got into ceramic fiber technology. At the time, it looked like just another materials business. A few decades later, it would become a second engine.

The catalyst was Europe. Diesel cars were everywhere, prized for fuel efficiency. But diesel exhaust also carries particulate matter—fine soot that’s dangerous to breathe and increasingly unacceptable to regulators. As European emissions standards tightened, automakers needed a practical way to trap that soot at scale.

Enter the diesel particulate filter, or DPF. A DPF is built like a honeycomb: exhaust gas flows through channels that are alternately sealed at opposite ends, forcing the gas through porous walls. The soot stays behind. Then, periodically, the system has to “regenerate”—burning off the accumulated soot at very high temperatures.

That high-heat moment is where Ibiden’s materials know-how mattered. Silicon carbide, a ceramic Ibiden knew how to work with, has very high thermal conductivity and can survive the punishing temperatures involved in regeneration. In other words: a problem Europe urgently needed to solve happened to match a capability Ibiden had spent decades building.

The business quickly became real, and then big. Ibiden set up manufacturing in Europe to be close to its customers, establishing Ibiden DPF France SAS in 2002. It followed with a second European production center in 2004, creating IBIDEN Hungary Ltd. in Dunavarsány, about 25 kilometers south of Budapest.

By then, this wasn’t an experiment. Europe produced around 6 million light diesel vehicles annually, and Ibiden was building an industrial footprint to serve that scale. Ibiden DPF France SAS alone represented a 60 million euro investment, with the Courtenay site designed to reach 300,000 filters per year per production line.

Over time, more than 10 million private cars in Europe were equipped with diesel particulate filters developed by Ibiden. The company built up a commanding position—about a 50% market share in Europe—meaning roughly half of the DPFs used in European vehicles came from a Japanese company that started as a hydroelectric utility.

Hungary became a centerpiece of that growth. The plant ran continuously, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It employed more than 1,700 people and produced around 2.4 million DPFs per year—about 200,000 a month—made from ceramic raw materials imported from Japan.

Strategically, this mattered for a reason that has nothing to do with tailpipes. It gave Ibiden balance. When Intel’s business swung—as semiconductors always do—Ibidden had a large automotive ceramics revenue stream smoothing out the ride. Different end markets, different customers, different cycles.

It also revealed Ibiden’s innovation model in its purest form. The company didn’t invest in ceramic fiber technology in 1974 because it foresaw European emissions policy decades later. It built capabilities adjacent to what it already understood, then stayed ready for the moment the world needed those capabilities. That patience—capability first, application second—became a competitive advantage.

Of course, nothing lasts forever. As the auto industry shifts away from diesel, this line of business faces real headwinds; electric vehicles don’t need particulate filters. But the two-decade run did its job. The ceramics business generated the time, stability, and resources that helped Ibiden keep investing in its other future—one that would soon move from CPUs to the center of the AI boom.

VII. The Crisis of Concentration: Intel Dependence & Stock Volatility (2020–2024)

For decades, the Intel partnership looked like the cleanest kind of win. Ibiden went from a regional Japanese manufacturer to a world-class substrate supplier. Its engineering capabilities ratcheted up. Its factories stayed busy. If you looked at the arc of the relationship, it was easy to assume the story would just keep compounding.

Then the narrative cracked.

At its peak, Intel made up roughly 70% to 80% of Ibiden’s chip package substrate revenue. By the fiscal year ended in March, that share had fallen to around 30% as Intel struggled through a difficult turnaround—one that ultimately included the ousting of CEO Pat Gelsinger. As the market repriced what that meant for Ibiden, the company’s stock fell by about 40% over the year.

Intel’s challenges in recent years have been widely discussed: losing process leadership to TSMC, ceding data center momentum to AMD, watching Apple move off Intel chips, and facing repeated execution hurdles even after launching an aggressive comeback plan. But for Ibiden, the issue wasn’t the headlines. It was the math. When your biggest customer is under pressure, your volumes and your margins feel it—fast.

That showed up in Ibiden’s own results. In October, the company lowered its profit outlook after sluggish demand for components used in general-purpose servers outweighed growth tied to AI servers. And it wasn’t just Ibiden. Fellow Japanese substrate maker Shinko Electric Industries also revised down its outlook, pointing to the same dynamic: generative AI was surging, but demand in standard servers—outside AI data centers—remained weak.

Ibiden also trimmed its fiscal 2024 (April 2024 to March 2025) forecast. Revenue expectations were cut to around ¥370 billion, and operating profit was revised down to about ¥40 billion. The underlying message was straightforward: the hoped-for rebound in IC packaging substrates, especially for PCs and standard servers, was coming more slowly than expected.

Investors weren’t overreacting. Customer concentration risk isn’t an abstract finance concept—it’s what happens when a single relationship becomes big enough to pull your whole company’s results, and then that customer hits turbulence. Ibiden lived the upside of that dynamic for years. Now it was living the downside.

But here’s the twist: the same concentration that created Ibiden’s vulnerability also forged its edge.

Thirty years inside Intel’s packaging universe didn’t just produce revenue. It produced capability. It trained Ibiden to build exactly the kind of high-end, high-layer, high-precision substrates that the AI era would later demand. In other words, Intel didn’t just buy substrates from Ibiden; it helped shape what Ibiden could do.

That’s why Kawashima’s posture toward Intel stayed notably respectful even as Ibiden diversified toward Nvidia and other customers. He continued to describe Intel as an essential, “treasured” customer, and he expressed confidence in Intel’s recovery. Strategically, that’s not sentimentality—it’s realism. You don’t burn bridges in an industry built on long qualification cycles and co-development. And Intel’s foundry ambitions could make it even more relevant to the next generation of chipmakers.

Kawashima has also argued that Intel could play an important role in Washington’s push to rebuild advanced semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S., particularly if foreign chipmakers remain reluctant to transfer their latest technology stateside.

So the Intel chapter lands with a tension every great component supplier eventually faces: deep partnership can be your fastest path to world-class capability—and your most dangerous single point of failure. Ibiden’s job in the 2020s was to keep the former, while eliminating the latter.

VIII. The AI Inflection: From Intel's Partner to Nvidia's Backbone (2022–Present)

The pivot that may have saved Ibiden started before most of the world had a name for what was happening. When ChatGPT lit the fuse in late 2022, Ibiden was already deeply embedded in Nvidia’s supply chain, building the substrates that sit under the GPUs now synonymous with the AI boom. Decades of patient capability-building had put the company in exactly the right place at exactly the right time.

And then demand hit.

Ibiden is the dominant supplier of chip package substrates used in Nvidia’s most advanced semiconductors—and CEO Koji Kawashima has been candid that the company may need to accelerate capacity expansion just to keep up.

“Dominant supplier” isn’t a tidy analyst phrase here. All of Nvidia’s AI semiconductors now use Ibiden’s substrates. The chips that train and serve the biggest models in the world rely on a component made by a Japanese company that started out building hydroelectric plants.

AI semiconductors already account for more than 15% of Ibiden’s sales, on revenue of around ¥370 billion ($2.3 billion). And that share is expected to rise. Demand for AI servers has been so strong it has exceeded expectations, with revenue tied to AI server-related products in fiscal year 2024 projected to be roughly three times fiscal year 2023.

So why Ibiden? Why can’t Nvidia simply dual-source this to any competent substrate maker?

Because “competent” isn’t enough at this end of the market.

These substrates have to survive the brutal realities of AI packaging: high power, high heat, and extremely tight dimensional tolerances. They form the foundation of the chip package, supporting components such as memory, and they need to resist thermal deformation. If the substrate warps, delaminates, or drifts out of spec, you don’t just lose performance—you can lose the entire package.

Analysts have argued that those requirements make it hard for new entrants to meet Nvidia’s standards. AI and high-performance computing are pushing the substrate industry toward larger sizes and higher layer counts. Ibiden’s own data shows that the ABF substrates used for AI data center chips are much larger than those used for traditional PC chips—meaning the manufacturing difficulty scales up, too.

The heat story alone tells you why this is unforgiving. Nvidia’s H100 can draw around 700 watts. That kind of power density is relentless, and it turns packaging into a stress test: the substrate has to stay stable while carrying signals and withstanding repeated thermal cycles.

That’s where Ibiden’s moat shows up—not as a buzzword, but as yield. As Toyo Securities analyst Hideki Yasuda put it: “Nvidia’s AI chips need sophisticated substrates, and Ibiden is the only one that can mass produce them at a good production yield.” He added that Taiwanese competitors likely won’t be able to take much share.

Yield is everything in this business. Making a handful of advanced substrates in a lab is one thing. Mass-producing them, repeatedly, with high quality and predictable output, is another. It takes years of process learning, tight control across dozens of steps, and the kind of manufacturing muscle memory you only earn the hard way.

And importantly, Nvidia isn’t Ibiden’s only door into the future. Ibiden’s customer list includes Intel, AMD, Samsung Electronics, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., and Nvidia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Many of these customers pull Ibiden in early, because substrates aren’t off-the-shelf parts. They’re co-designed around each chip, to transmit signals from the semiconductor to the circuit board in exactly the way the architecture requires.

That matters strategically because it shows Ibiden’s diversification is real. The company is no longer defined by a single anchor customer. It now sits across the industry’s power centers—and is positioned to supply whoever wins.

And “whoever wins” is the point. Over time, Nvidia may face pressure from application-specific chips from Marvell and Broadcom, and from in-house silicon efforts at companies like Google and Microsoft. Kawashima’s view is that Ibiden can serve those customers too. Even if the logos change, the core reality remains: advanced AI chips will still demand advanced packaging, and the design and materials needs are likely to stay broadly similar.

Ibiden isn’t betting that one company will own AI forever. It’s betting that, no matter who designs the chips, the world will need substrates that only a few companies on Earth can reliably make.

IX. The Capacity Race: Building for the AI Future (2024–2026)

AI substrate demand is now so far ahead of supply that Ibiden’s customers are negotiating for capacity that, in a very literal sense, hasn’t been built yet.

Ibiden is constructing a new substrate factory in Gifu Prefecture in central Japan. The plan is for the site to come online at about 25% of capacity around the last quarter of 2025, then ramp to 50% by March 2026.

Even that, Kawashima has admitted, may not be enough. Ibiden is already in discussions about pulling forward the timing for the remaining 50% of capacity. “Our customers have concerns,” he said. “We’re already being asked about our next investment and the next capacity expansion.”

It’s hard to overstate what that means. Ibiden is still pouring concrete for the current wave of expansion, and customers are already asking for the next one. In a supply chain where qualification takes time and mistakes are brutally expensive, that kind of pre-commitment is a signal: the AI buildout is pushing years ahead of critical manufacturing capacity.

Operationally, Ibiden is also shuffling pieces to move faster. With generative AI demand running hot, the Ono factory—which can produce a range of boards—is set to begin operations as scheduled in fiscal year 2025, and will take on some of the production that had originally been planned for the Gama plant. At the same time, Ibiden is stepping up development of next-generation boards, including boards designed for 3D packaging.

That’s where TSMC enters the story. Ibiden has joined the TSMC-led “TSMC 3DFabric Alliance,” and plans to work within TSMC’s Open Innovation Platform ecosystem, using 3Dblox standards. The goal is to support the IC board capacity needed for advanced process chips, with an ambition to expand capacity dramatically from today’s level.

Kawashima framed the move in the language of the roadmap: “The development of information and communication technology requires further integration and performance improvement of semiconductors,” he said. “IBIDEN welcomes TSMC’s initiative to launch the 3DFabric Alliance to further develop 3D packaging technology and will contribute to product realization in cooperation with joint partners.”

TSMC has also said it has worked with substrate partners including IBIDEN and UMTC to define a Substrate Design Tech file aimed at enabling substrate auto-routing, improving efficiency and productivity.

Strategically, the implication is straightforward: as the industry moves from 2D chips to 2.5D and 3D architectures—where multiple dies are combined and stacked to drive performance—substrates only get harder. Getting pulled into the ecosystem early is how you make sure you’re building what the next generation of packaging will require, not what the last generation happened to accept.

One place Ibiden is not racing to build, though, is the United States. The company has no manufacturing facilities there, and Kawashima has said it has no plans to add any because of labor and logistics costs—even with the possibility of broad tariffs under U.S. president-elect Donald Trump.

That choice may sound counterintuitive in an era of reshoring, but it fits Ibiden’s core belief: this is a process business. Substrates demand specialized skills and tight quality control, and Ibiden’s manufacturing depth is concentrated in Japan. Kawashima’s bet is that keeping that process excellence intact matters more than optimizing for political optics.

For investors, the larger point is that these aren’t symbolic investments. Building and ramping leading-edge substrate capacity is expensive, slow, and hard to reverse. Ibiden is doing it anyway—because it believes the AI infrastructure wave has enough durability to justify the commitment.

X. Competitive Landscape & Porter's Five Forces Analysis

To understand how Ibiden ended up in such an enviable position—and why it’s so hard to dislodge—you have to look at the structure of the substrate industry itself. This is one of those markets where “competition” doesn’t just mean who has the cheapest factory. It means who can clear the technical bar, earn customer trust, and then keep delivering at yield, at scale, for years.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

At the high end, chip package substrates are brutal products to make well. They’re dense, precise, thin, and packed with performance requirements that get less forgiving every year. That’s why, even in the most optimistic scenario, new entrants don’t just show up and start shipping.

According to minutes from an investor survey by Xinsen Technology, a newcomer typically needs at least 2 to 3 years just to get through the basics: assemble a team, secure land, build a plant, complete equipment installation and debugging, pass major customer certifications, and then ramp production. And that’s the optimistic case—where everything goes right and the customer qualification process moves quickly.

In reality, “two to three years” is often just the minimum time to get to the starting line. The harder part is proving you can manufacture these substrates with consistent reliability and high yields—because in this business, yield isn’t a nice-to-have. It is the business.

The industry’s history reinforces that barrier. As semiconductor manufacturing shifted over time to South Korea and Taiwan, the packaging substrate industry gradually developed there too. With Korean and Taiwanese manufacturers entering aggressively, many Japanese companies pulled back from the medium- and low-end market and doubled down on the high-end segments—products like FC BGA and FC CSP. The result is a stratified market: Japan, including players like Ibiden, is strongest at the top; Korea and Taiwan dominate the higher-volume, more standardized segments.

For a new entrant, that’s a nasty setup. You’re not just competing with “a supplier.” You’re competing with decades of accumulated process learning and a customer base that has every incentive to avoid risk.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE-HIGH

If there’s a single pressure point in this whole ecosystem, it’s ABF resin.

Ajinomoto holds an extraordinary position in ABF materials used in CPU and GPU substrates—over 95% of global market share. And Ajinomoto has acknowledged a roughly 20% demand-supply gap that is expected to persist until new resin reactors start in 2026.

That shortage creates a hard ceiling for the entire industry. Even if a substrate maker has demand, customers, and factory space, it can’t ship what it can’t feed. When ABF is constrained, everyone is constrained—including Ibiden.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Ibiden’s customers are giants: Nvidia, Intel, AMD, and others with enormous purchasing power. But in advanced substrates, raw buying power only goes so far.

These substrates aren’t interchangeable parts. Many customers consult with Ibiden early in product development because the substrate—whose job is to transmit signals from the semiconductor to the circuit board—has to be tailored to each chip. Once that co-design work happens and a chip program is built around a specific substrate architecture, switching suppliers midstream becomes expensive, slow, and risky.

So buyers have leverage in negotiations, but they don’t have unlimited freedom of choice. At the cutting edge, there simply aren’t many suppliers you can trust to deliver, at volume, at yield.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW (but emerging)

The most credible substitute on the horizon is glass.

On September 18 (U.S. local time), Intel announced production plans for what it described as the world’s first glass substrate designed for advanced packaging, with production targeted in the 2026 to 2030 window. Intel believes glass could deliver 10x or more through-hole density versus organic substrates, and enable lower loss, higher-speed signaling—up to 448G.

That’s real potential disruption, but it’s not an overnight one. The adoption curve for a foundational packaging material is long, qualification cycles are punishing, and the ecosystem has to rebuild around the new manufacturing reality.

Ibiden isn’t ignoring it, either. It’s investing in glass substrate technology as a hedge—positioning itself to adapt if and when glass moves from “roadmap slide” to “mass adoption.”

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

The substrate market is concentrated—and still intensely competitive.

According to the Taiwan Printed Circuit Association, the top global substrate suppliers and their market shares in 2022 included Unimicron (17.7%), Nan Ya Printed Circuit Board (10.3%), Ibiden (9.7%), Samsung Electro-Mechanics (9.1%), and Shinko Electric Industries (8.5%).

The top five players—Unimicron, Ibiden, AT&S, Nan Ya PCB, and Shinko Electric Industries—collectively hold about 74% market share. Geographically, Taiwan leads with around 30%, followed by mainland China and South Korea at about 17% each.

So yes, a handful of companies control most of the market. But no one player owns it outright. Rivalry plays out through technology, yields, customer trust, and capacity—more than simple price cutting. And in a world where AI demand is outstripping supply, the winners are the ones that can reliably make the hardest substrates, in volume, without blowing up their process.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter explains why this industry is structurally tough. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers helps explain something more specific: why Ibiden, in particular, has been able to build advantages that persist.

Scale Economies: STRONG

Substrate manufacturing has real scale economies. Cleanrooms, specialized equipment, and R&D are expensive, and the more volume you run, the more those fixed costs get diluted.

Ibiden is one of Japan’s leading ABF substrate makers, known for pushing substrate design and production forward and for serving demanding end markets like automotive and consumer electronics. Just as importantly, its broad customer roster lets it spread development and process investments across many chip programs. When you’re supplying Intel, Nvidia, AMD, Samsung, and TSMC, you can justify building capabilities that pay off again and again, rather than being trapped funding one customer’s roadmap with one customer’s margin.

Network Effects: MODERATE

This isn’t a classic network-effects business. Nvidia doesn’t get more value from Ibiden because Intel also uses Ibiden.

But there is a network-like dynamic that comes from ecosystems and standards. TSMC has worked with substrate partners including IBIDEN and UMTC to define a Substrate Design Tech file intended to enable substrate auto-routing—improving efficiency and productivity.

When your methods and design assumptions get baked into the industry’s tooling and workflows, you don’t just become a vendor. You become part of how the ecosystem operates. It’s not a consumer-style network effect, but it does create stickiness that feels similar.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG (historically)

When Korean and Taiwanese competitors expanded in substrates, Japanese manufacturers largely chose not to fight a volume-and-price war in the middle of the market. They leaned into the high end—applications where technical performance and reliability mattered more than cost.

That move is a form of counter-positioning: competitors can’t simply copy it without rebuilding their capabilities and economics. And the Kawashima story—waiting outside Intel’s headquarters day after day to get feedback—captures the same mindset. Most suppliers won’t invest that kind of time and persistence without a guaranteed payoff. Ibiden did, and the relationship it built became a capability engine competitors couldn’t easily replicate.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

Many customers bring Ibiden in early because substrates aren’t off-the-shelf. They’re tailored to each chip, and they sit at the intersection of thermal behavior, electrical performance, and long-term reliability.

That design-in process creates massive switching costs. If you change substrate suppliers, you aren’t just swapping a part number—you’re revalidating the package: heat, warpage, signal integrity, stress, reliability. That can take months or years, and it introduces real risk of new defects. So once Ibiden is designed in, it’s hard to displace.

Branding: MODERATE

In B2B manufacturing, “brand” doesn’t mean household recognition. It means what engineers and program managers believe will happen when they bet their chip launch on your component.

Ibiden isn’t famous to consumers, but it does have a reputation among chip designers for quality and reliability. In an industry where a small defect can become a massive failure, that reputation is an asset.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

Ibiden is often described as innovative in substrates, with strong R&D capabilities and a meaningful position across markets including automotive and consumer electronics.

Underneath that is a deeper cornered resource: accumulated know-how in high-temperature materials and thermal stress—expertise that traces back through its electric furnace businesses and, later, ceramics. This is institutional knowledge about how materials behave under heat and repeated cycling, built over decades, that competitors can’t simply buy.

The same ceramics foundation that enabled the diesel particulate filter business also reinforced the substrate business. It’s proprietary, experience-based know-how—developed over half a century—that would be painfully slow to replicate.

Process Power: VERY STRONG

“Nvidia’s AI chips need sophisticated substrates, and Ibiden is the only one that can mass produce them at a good production yield,” an analyst said.

That’s the heart of the moat: process power. It’s the ability to run an incredibly complex manufacturing process consistently, efficiently, and at high yield. This advantage lives in tacit knowledge—how teams respond to small variations, which subtle signals predict failures, and what adjustments actually improve output without compromising reliability.

A competitor can buy similar equipment and hire talented engineers. What they can’t quickly recreate is the organizational muscle memory that delivers high yields, at volume, for the most demanding customers. Ibiden built that the hard way, over decades—and in advanced substrates, that’s the difference between “can make” and “can ship.”

XII. The Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

So what should we take away from Ibiden’s 112-year run—from river-valley hydropower to the heart of the AI supply chain?

1. Reinvention as Core Competency

Ibiden didn’t “pivot” once. It kept evolving: hydroelectric power to electric furnaces, electrochemicals to building materials, construction products to printed circuit boards, PCBs to IC substrates, and now substrates that sit beneath the world’s most advanced AI chips.

What’s striking is that these moves weren’t random trend-chasing. Each reinvention carried forward something Ibiden already knew how to do—process discipline, materials science, high-reliability manufacturing—and then aimed that competence at whatever the world suddenly couldn’t get enough of. Over a century, that ability to change shape without losing your identity may be the company’s most important asset.

2. Patient Capability Building

Ibiden repeatedly invested before the payoff was obvious. Ceramic fiber technology developed in 1974 later became the foundation for the DPF business that took off around 2000. The Intel relationship cultivated in the early 1990s didn’t just drive revenue—it trained Ibiden’s organization to manufacture at the frontier, which later made the Nvidia and AI surge possible.

That kind of patience is uncomfortable, especially as a public company. But in hardware businesses—where qualification cycles are long and manufacturing learning curves are brutal—capabilities often have to be built years before the market rewards them.

3. Concentration Risk Cuts Both Ways

The Intel era is the clearest example of the trade-off. A deep partnership can turn a supplier into a co-developer and accelerate its capability curve in a way no transactional customer ever will. But it can also make your entire company hostage to someone else’s execution.

Ibiden’s answer wasn’t to slam the door. It kept Intel close while deliberately widening the customer base—pursuing Nvidia and others without abandoning the relationship that helped make it world-class in the first place. For any component supplier, that’s a useful pattern: keep the depth, reduce the dependency.

4. Adjacent Expansion from Technical Strength

Nearly every successful diversification in Ibiden’s history has been adjacent to an existing strength. Building materials leveraged its industrial materials base. Printed circuit boards drew on high-temperature and precision processing. Diesel particulate filters grew out of ceramic fiber know-how. And today’s AI substrates build directly on decades of advanced packaging and process control.

That’s diversification with a safety rail: you’re entering new markets, but you’re not starting from zero. You’re carrying in an unfair advantage.

Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring:

If you’re tracking Ibiden going forward, three signals matter more than most headlines:

-

AI substrate revenue as a share of total sales – It’s already meaningful, and it should rise if Ibiden stays embedded in the AI buildout. This is a simple proxy for whether the company is capturing the right end of the demand wave.

-

Manufacturing yield on high-end, high-layer substrates – Ibiden’s moat shows up in yield. The company doesn’t disclose everything, but any management commentary that points to improving yields—or yield pressure—will usually tell you more than broad market forecasts.

-

Customer concentration within the substrate segment – The shift in Intel’s share of substrate revenue shows how quickly concentration can change. Continued diversification across Nvidia, AMD, and other advanced-chip programs reduces single-customer risk—and makes Ibiden more resilient across cycles.

XIII. Bull Case, Bear Case, and Investment Considerations

The Bull Case:

If you want the cleanest version of the upside story, it’s this: Ibiden sits in the small set of companies that can actually ship the substrates the AI boom requires—at scale, at yield, and with the trust of the world’s most demanding chip designers.

Street expectations reflect that momentum. Analysts covering the stock forecast strong revenue growth into fiscal 2025 and then additional growth in fiscal 2026. And while Ibiden lives in a cyclical industry, it has also shown it can expand profitability over time. Gross margins, for example, have trended upward over the past decade.

The bull case starts with the market itself. AI infrastructure spending still looks more like a multi-year buildout than a one-time surge. Nvidia, AMD, and custom chip designers continue to announce bigger platforms, and that implies more capacity, more advanced packaging, and more demand for high-end substrates.

Then there’s Ibiden’s edge: process power. At the high end, substrates aren’t “make it once and you’re done” products. The winners are the ones who can mass-produce sophisticated designs reliably, with strong yields. That’s exactly what analysts point to when they say Ibiden is hard to dislodge—and it’s also why early engagement with major chip designers matters so much. Ibiden isn’t betting on one logo. It’s positioned to supply whoever wins the next round of AI hardware.

Finally, there’s the capacity ramp. Ibiden is already investing to expand, and if those ramps go well, the company has a clear path to more volume through 2026 and beyond.

If all of that holds, the margin story gets even better. AI substrates are premium products—bigger, more complex, more demanding. As they become a larger share of the mix, margins can rise with them.

The Bear Case:

The risks are real, and they cluster around one theme: in semiconductors, today’s bottleneck can become tomorrow’s obsolete link—or tomorrow’s constraint can cap your growth no matter how strong demand is.

Glass substrate disruption: Intel has announced plans for glass substrates for advanced packaging, targeting production in the 2026 to 2030 timeframe.

If glass delivers the promised leap in interconnect density, it could eventually take share from today’s organic substrate approaches in the highest-end applications. Ibiden is investing in glass as well, but investing doesn’t guarantee leadership. A transition like this can reshuffle the leaderboard.

ABF supply constraints: Ajinomoto, the near-monopoly supplier of ABF resin, has acknowledged a meaningful demand-supply gap that may persist until new capacity comes online in 2026.

This one is simple and unforgiving: even if Ibiden has customers ready to buy and factories ready to run, it can’t ship what it can’t source. ABF availability can become the governing constraint on growth, independent of Ibiden’s own execution.

Customer concentration evolution: Intel’s share has fallen sharply from earlier peaks, and as AI ramps, Nvidia’s importance likely rises.

That’s progress in diversification—but it doesn’t eliminate the underlying hazard. If too much of the business again concentrates in a single customer, Ibiden risks replaying the same story: world-class capability, but exposure to someone else’s cycle and competitive fortunes.

Cyclicality: Substrates are still part of the broader semiconductor ecosystem, and that ecosystem swings.

AI spending could slow if macro conditions tighten, if customers digest capacity after a surge, or if the pace of model-driven demand surprises to the downside. Even in an “AI everywhere” world, procurement doesn’t move in a straight line.

Key Risks and Regulatory Considerations:

Geopolitics sits over everything in semiconductors now. Export controls, U.S.-China tensions, and potential tariff regimes can affect customer demand, supply chain reliability, and where new capacity gets built. Ibiden’s Japan-centered manufacturing footprint reduces some operational complexity, but it also concentrates execution in one geography and doesn’t insulate the company from policy-driven shocks in its customers’ end markets.

And then there’s the ceramics side. Environmental regulation originally helped create the DPF opportunity, but the longer-term trend toward electric vehicles reduces diesel particulate filter demand. That shift is gradual, and it gives Ibiden time to adjust its mix—but it’s still a structural headwind that matters when you think about what the company looks like a decade out.

XIV. Conclusion: The Persistence Premium

Ibiden’s story, more than anything, is a story about persistence—about how continuous improvement compounds when you’re willing to do it for decades.

Koji Kawashima now leads a company that began, 112 years ago, as a regional hydroelectric business. Since then, Ibiden has lived through world wars, economic shocks, technology shifts, and fierce global competition. And instead of getting locked into one identity, it kept adapting—often by taking the hard, unglamorous path of building capability first and trusting that the right market would eventually need it.

That’s why it matters that Ibiden isn’t simply “the Nvidia supplier.” The AI race is still early, the winners will change, and architectures will evolve. But Ibiden is positioned where it wants to be: inside the packaging stack, in the part of the system that has to work no matter whose logo is on the chip.

And Ibiden didn’t get that position from one lightning-strike invention. It earned it through accumulation: materials expertise that goes back to its early electrochemical roots, precision manufacturing capabilities strengthened through its moves into electronics, and co-development relationships forged in the 1990s—plus the capacity expansion it’s investing in right now.

The Kawashima origin story with Intel is the purest snapshot of what that looks like in practice. In the early 1990s, he would wait outside Intel’s headquarters in Santa Clara day after day, stopping engineers and executives to ask what Ibiden needed to improve. That persistence helped turn a long-shot introduction into a partnership—and, eventually, into the set of substrate capabilities that would make Ibiden valuable to the rest of the industry.

That image—showing up, repeatedly, to get better—captures something essential about Ibiden’s culture. This isn’t a company that expects quick wins. It’s a company built around the idea that the hard work is the strategy, and that if you keep improving long enough, the market eventually rewards you.

For investors, that creates an unusual setup: exposure to one of the fastest-growing infrastructure buildouts in the world, through a company whose edge comes from capabilities developed over generations. The moats here aren’t marketing claims. They show up in process power, in switching costs created through co-design, and in specialized know-how that can’t be recreated on a typical corporate timeline. And the leadership team—shaped by someone who personally lived the upside and downside of deep customer dependence—seems acutely aware of both the value and the risk of those relationships.

None of this makes Ibiden a sure thing. Technology can shift. Customer concentration can come roaring back in a new form. Semiconductor cycles don’t disappear just because the end-market is exciting.

But if you’re looking for a way to participate in the AI infrastructure wave through a company with durable competitive advantages, Ibiden deserves a serious look. A century-old hydropower company has quietly worked its way into the center of modern computing. Whether it compounds from here for another generation is unknowable—but the last 112 years suggest one thing: betting against Ibiden’s ability to adapt has rarely been a winning trade.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music