SK Square: The Hidden Crown Jewel of Korea's AI Chip Boom

I. Introduction: The Strangest Valuation Anomaly in Global Tech

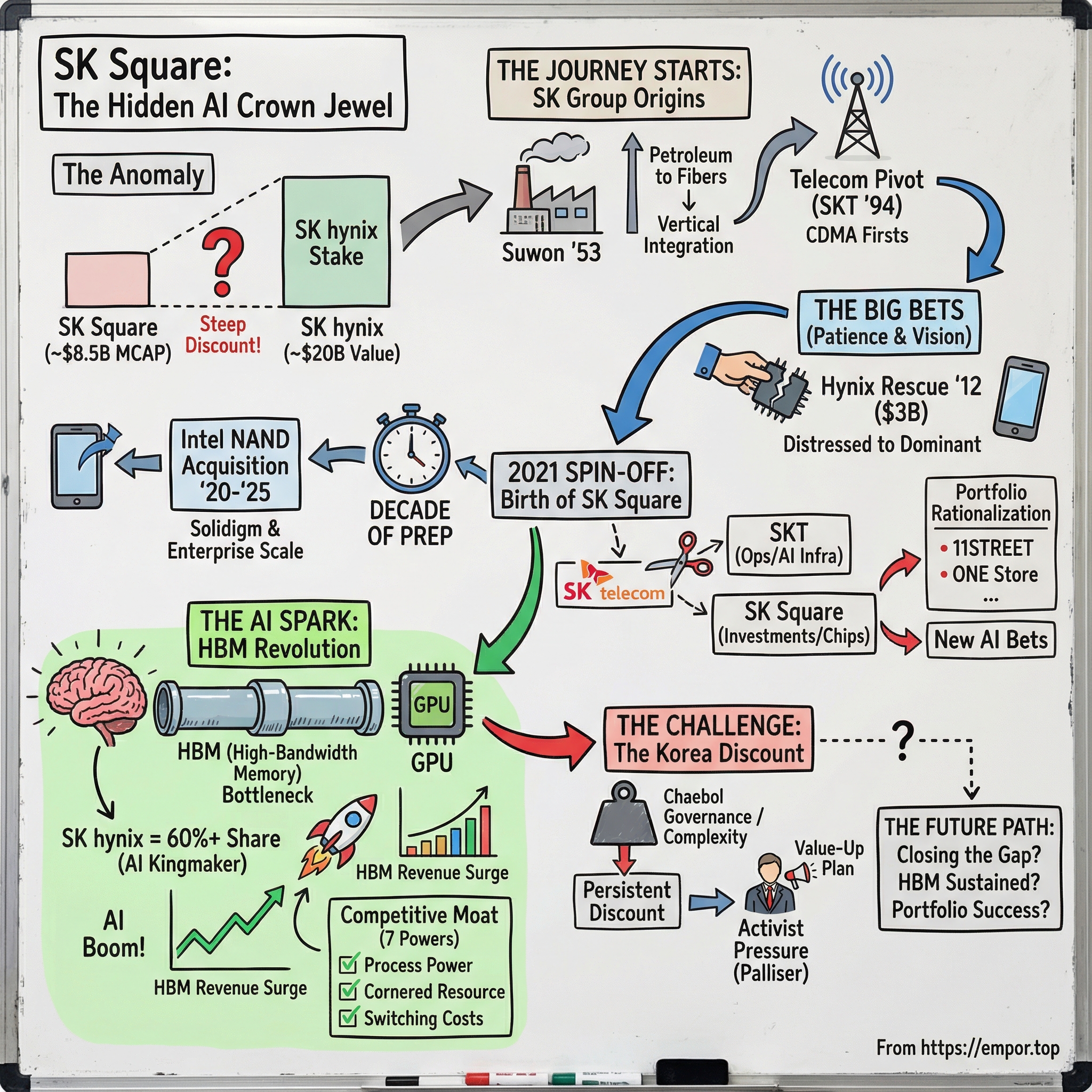

Picture this: a company owns a chunk of what might be the most important bottleneck asset in the entire AI revolution.

SK Square owns roughly 20% of SK hynix, the world’s dominant supplier of high-bandwidth memory. HBM is the specialized memory that sits right next to Nvidia’s most advanced GPUs and feeds them data fast enough to train modern AI models. In other words: if GPUs are the engines of AI, HBM is the fuel line.

That stake in SK hynix has been worth around $20 billion. And yet SK Square itself has traded around a roughly $8.5 billion market cap.

That gap is the story.

Because this isn’t some weird, illiquid stub stock. SK Square was created in 2021, spun out of South Korea’s biggest mobile carrier, and it now sits at the center of one of the most strategically important supply chains on earth. SK hynix doesn’t just participate in the HBM market; it has led it, with about 70% share, according to Counterpoint. And by the first quarter of 2025, it had even taken the top spot in DRAM revenue share for the first time, reaching 36%, powered by the HBM boom.

So how does a holding company that effectively controls that kind of asset wind up valued at a fraction of it?

To answer that, you have to rewind through seventy years of Korean industrial history: the rise of the chaebol system, the near-death experience of one of the world’s biggest memory makers, a roughly $3 billion rescue led by a telecom company with no semiconductor DNA, and then a corporate spin-off that reorganized SK’s tech empire into something that looks, in hindsight, like a direct call option on the AI buildout.

And we’ll go beyond the origin story. We’ll get into why Korean stocks have long traded at chronic discounts to global peers, why a London-based activist fund founded by a former Elliott Management executive has been building a stake and pushing for changes, and whether SK hynix’s HBM dominance is a durable advantage—or just the peak of another brutal semiconductor cycle.

This is the story of SK Square, and why it might be one of the clearest windows into how the AI era is actually being financed and built.

II. The SK Group Origin Story: Textiles to Telecom

In the winter of 1953, South Korea was still a landscape of wreckage. The war had just ended, the economy was shattered, and “industrial policy” mostly meant: survive.

That’s when Chey Jong-gun, SK’s founding chairman, bought a ruined textile plant in Suwon, just south of Seoul, from the Korean government. The facility had originally been Japanese property. During the fighting it had been bombed out and abandoned—more rubble and twisted metal than factory.

Chey didn’t just buy it. He rebuilt it. And he did it the hard way: overseeing the work up close, reportedly sleeping most nights on a camp bed in the administration building while the place came back to life.

By October 1953, the factory was running again—small, basic, and practical, with a handful of weaving machines turning out textiles for domestic demand. It’s an almost simple origin story: a man, a broken building, and the stubborn decision to make something productive out of the aftermath.

That decision became the seed of what would grow into one of South Korea’s biggest business empires.

The Chaebol Context

But you can’t really understand SK without understanding the system it grew up in: the chaebols.

Chaebols are Korea’s family-controlled conglomerates—massive clusters of companies spanning industries, with influence that reaches well beyond the private sector. SK Group, headquartered in Seoul, would eventually become the country’s second-largest chaebol by revenue, behind Samsung.

They emerged in the postwar era as partners in national development. The government needed industrial champions; the chaebols got access to capital, protection, and policy support. In return, they built factories, infrastructure, and export machines that helped propel South Korea from poverty to global economic power.

That bargain created a distinctive mix: enormous capacity for long-term investment—and persistent questions about governance. Family control, often reinforced through cross-shareholding and complex corporate structures, can enable patience and coordination over decades. It can also leave minority shareholders feeling like passengers, not drivers. That tension sits right at the center of the “Korea discount” we’ll come back to later.

The Vertical Integration Strategy

Chey Jong-gun died suddenly in 1973, at just 47, after a heart attack. Control passed to his younger brother, Chey Jong-hyon, who had joined the company in the early 1960s after years of study in the United States. He earned a chemistry degree at the University of Wisconsin and later an M.B.A. at the University of Chicago—training that would shape how he thought about industry.

And he brought a philosophy that set Sunkyong apart from the typical chaebol playbook.

Instead of grabbing anything that looked like growth, Chey pushed for vertical integration: controlling the full production chain, especially the raw materials that determined costs and competitiveness. In 1973, he founded Sunkyong Petroleum—an explicit move to secure the inputs upstream of the textile business.

By 1975, that thinking hardened into a strategy with a name: “From Petroleum to Fibers.” The idea was straightforward and powerful—own the feedstock, own the process, own the margin.

The approach paid off. In December 1980, the group bought Korea National Oil, a leap that helped vault Sunkyong into the top tier of Korean conglomerates. Years later, in 1998, the company rebranded from Sunkyong Group to SK Group.

By then, the foundation was set: a chaebol built not just on expansion, but on control of critical value chains. And that mindset—find the bottleneck, own it—would eventually take SK somewhere no one would have predicted from a textile mill in Suwon: into the heart of Korea’s telecom industry, and later, the global semiconductor wars.

III. The Telecom Pivot: SK Enters the Digital Age

By the 1980s, Sunkyong was firmly an energy-and-chemicals powerhouse. But inside the group, leadership was quietly fixating on a very different kind of infrastructure: telecommunications.

What’s striking is how early SK started laying track. In 1984, it set up a Telecommunication Team inside its U.S. business planning office. In 1989, it created a U.S. affiliate, Yucronics, to manage the effort end-to-end. In 1990, it formed SK Information System through a joint venture with the American IT company CSC. None of this was glamorous. It was patient, unflashy capability-building—ten years of preparation before SK made its move.

And then, in 1994, the move came.

SK entered an open tender for shares of Korea Mobile Telecommunication and bought a 23% stake, paying KRW 335,000 per share—above the market price. That wasn’t overenthusiasm. It was intent. After a decade of groundwork, SK wasn’t going to lose the asset over a price quibble.

Ten years of preparation before making the decisive move—this was the patience of a conglomerate thinking in decades, not quarters.

The Privatization Opportunity

The opening was created by policy. In January 1994, Korea Mobile Telecom was privatized through open bidding as part of the government’s push to strengthen the competitiveness of Korea’s domestic telecommunications industry.

Korea Mobile Telecom had been tied to the state-owned Korea Telecom system. Once the government shifted toward competition and privatization in the early 1990s, SK was ready—while others were still debating whether telecom was worth the trouble.

SK’s acquisition, and the premium it paid, reflected the conviction of Chairman Chey Jong-hyon: that communications would be a long-term growth engine, and that Sunkyong had done the homework to win.

The CDMA Revolution

What followed wasn’t just a financial success. It was a technological statement.

In January 1996, SKT—by then operating as a newly privatized carrier—commercialized CDMA digital mobile phones for the first time in the world. CDMA, or Code Division Multiple Access, was still a leap of faith when Korea chose it as the national cellular standard in 1993. It hadn’t been proven commercially at scale. The government made the call anyway, betting that a true next-generation technology would give Korea a foothold in a brutally competitive global market.

The bet worked. South Korea launched the world’s first successful CDMA commercial service, demonstrating that digital mobile networks could beat analog performance in the real world, not just in engineering papers. And it didn’t happen in isolation—SK Telecom’s execution, alongside ETRI and major electronics manufacturers like Samsung, LG, and Hyundai Electronics, helped build an ecosystem that other mobile operators around the world would later adopt.

Over the next decade, SK Telecom kept collecting “firsts.” In May 2006, it became the world’s first carrier to commercialize HSDPA. In February 2008, it pushed beyond wireless by acquiring the second-largest fixed-line operator, Hanaro Telecom.

By the mid-2000s, SK Telecom had become Korea’s dominant mobile carrier: a cash-generating machine with the freedom to expand into services and content. It launched Melon in 2004, helped shape mobile media consumption, and pushed early into navigation with what would become TMAP.

But the bigger point is what this period did to SK’s identity. The group that had once mastered physical supply chains—petroleum into fibers—had now learned how to run a national digital network, deploy bleeding-edge standards, and build platforms on top of them.

And that would set the stage for the next, far more audacious expression of the same instinct to own the bottleneck: a telecommunications company going out and buying a semiconductor manufacturer.

IV. The SK Hynix Acquisition: A $3 Billion Bet on Memory

To understand why a telecommunications company would spend roughly $3 billion to buy a memory chip manufacturer, you first have to understand what SK was actually buying. Because Hynix wasn’t a shiny growth asset. It was a scarred survivor of one of the nastiest cycles in global tech.

Hynix's Troubled Origins

Hyundai Electronics was founded in 1983 by Chung Ju-yung, the founder of Hyundai Group. In the early 1980s, Chung saw electronics becoming critical to modern industry—especially for automobiles, one of Hyundai’s core businesses—and he wanted Hyundai to have a real stake in that future.

Through the 1990s, Hyundai Electronics rode the PC boom, expanded aggressively, and built huge DRAM fabrication capacity. Then the bottom fell out. When the tech bubble burst in 2001, memory prices collapsed, and the company’s semiconductor arm went into free fall.

In 2001, the crash left the business facing an annual loss of roughly ₩5 trillion. Survival meant drastic measures: spinning off non-memory businesses like LCDs, consumer electronics, and telecom equipment, and narrowing focus back to the one thing it could still plausibly win at—memory. In March 2001, it renamed itself Hynix Semiconductor, blending “Hyundai” and “Electronics” into a new identity meant to signal a clean break.

But the rebrand didn’t magically solve the underlying problem. For the next decade, Hynix lived in corporate limbo: too strategically important to South Korea to be allowed to fail, but too weighed down by debt and uncertainty to invest aggressively enough to lead. Its creditor group—including Korea Exchange Bank, Woori Bank, Shinhan Bank, and Korea Finance Corporation—tried repeatedly to sell their stake, and repeatedly failed. Names like Hyosung, Dongbu CNI, and even former stakeholders such as Hyundai Heavy Industries and LG were floated as potential buyers. Deals were explored, challenged, and withdrawn. No one wanted to inherit a cyclical, capital-intensive chip business with baggage.

The Rescue

Then, in July 2011, SK Telecom entered the bidding, alongside STX Group. STX dropped out in September 2011, leaving SK Telecom as the remaining bidder. In February 2012, SK ultimately acquired Hynix for about US$3 billion, taking a 20.1% stake for roughly KRW 3.4 trillion and management control. Once it was brought into the group, the company was renamed SK hynix.

From the outside, the move looked bizarre: a phone company buying a chipmaker. But inside SK, it tracked perfectly with the group’s long-running instinct: find the bottleneck and own it. SK had spent years studying semiconductors and came away convinced chips would be a defining industry for Korea’s future—and a new growth engine for a telecom business that had matured. SK Telecom’s own stock had been stuck, and growth had been stagnant for years. In that context, stepping into semiconductors didn’t feel optional. It felt inevitable.

There was also portfolio logic. Memory is volatile; telecom is steady. Put them together and, in theory, you get a group with both cash-flow stability and upside exposure. And SK Telecom had the one thing most would-be buyers didn’t: the financing capacity. The telecom business threw off predictable cash and could support a mix of retained earnings and bank loans to fund the acquisition.

The deal even mattered culturally. Bringing Hynix into SK helped push the group’s identity beyond “domestic, old-economy incumbent” and toward something more global and technology-forward—important for a chaebol that wanted to be seen as a national champion, not just a local conglomerate.

Post-Acquisition Transformation

Almost immediately, Hynix started paying back the bet. Strong performance began generating significant dividends for the group, which helped reduce acquisition-debt 부담 and improved SK’s overall financial position. The circular logic of the deal worked: SK Telecom’s stability financed the purchase, and SK hynix’s cash generation helped service what the group had borrowed to buy it.

In 2013, SK hynix posted what was then its best-ever year, reaching annual sales of KRW 14 trillion with an operating profit ratio of 24%. That performance wasn’t just “good execution.” It was also timing. In 2013, Japanese memory maker Elpida went bankrupt, tightening the industry into a smaller club dominated by Samsung, SK hynix, and Micron.

In other words: SK didn’t just buy a troubled chipmaker. It bought near the bottom of the cycle—right before the competitive landscape consolidated in its favor.

V. The Intel NAND Acquisition: Eating Intel's Lunch

If buying Hynix was SK’s entry ticket into semiconductors, buying Intel’s NAND business was the follow-up move that said: we’re not here to participate. We’re here to climb the leaderboard.

The Deal Structure

In October 2020, Intel agreed to sell its NAND flash memory and SSD business to SK hynix in a deal ultimately valued at about $8.85 billion. It wasn’t a simple, one-and-done acquisition. It was structured in two closings stretched over years.

The first phase closed in December 2021. SK hynix paid about $6.61 billion and took over Intel’s SSD business and the NAND manufacturing facility in Dalian, China, along with associated IP and employees tied to those products. Then, in March 2025, the second closing completed the transfer: Intel received a final payment of about $1.9 billion, and SK hynix officially obtained the remaining NAND-related IP and personnel—bringing the multi-year transaction to the finish line.

The Solidigm Strategy

The operating plan had a name: Solidigm, the brand SK hynix used for the acquired Intel SSD business. Park Jung-ho, then vice chairman and co-CEO of SK hynix, framed it as a step-change moment: “My heartfelt welcome to the Solidigm team members who are joining our family. This acquisition will present a paradigm shifting moment for SK hynix’s NAND flash business to enter the global top tier level.”

And strategically, it made sense. SK hynix already had a world-class position in DRAM. But NAND is a different battleground—more commoditized, more cutthroat, and much harder to differentiate. Intel brought something SK hynix wanted badly: serious enterprise SSD capability, the kind that lives inside data centers and hyperscale storage racks.

That mattered because AI doesn’t just require compute. It requires oceans of fast, reliable storage to feed the models—training data, checkpoints, retrieval indexes, everything. With Solidigm’s enterprise SSD strengths alongside SK hynix’s mobile NAND leadership, the combined pitch was simple: close the gap in NAND competitiveness until it starts to look more like SK hynix’s DRAM business.

There was also a narrative twist here that’s hard to miss. Intel—one of the companies that helped invent DRAM, and once dominated memory before walking away in the 1980s to focus on microprocessors—was exiting memory again, this time NAND. Intel called it a strategic realignment: NAND had become a low-margin grind, and the company wanted to focus on higher-growth priorities like AI chips and advanced manufacturing.

SK hynix looked at the same situation and saw an opening. Where Intel saw a distraction, SK hynix saw a chance to buy scale, talent, and enterprise credibility—right before the world’s data centers began rebuilding themselves around AI.

VI. The 2021 Spin-off: Birth of SK Square

By 2021, SK Telecom had turned into something far bigger—and stranger—than a phone company. Yes, it still ran Korea’s dominant wireless network. But it also sat on a crown-jewel stake in SK hynix, plus a growing portfolio of tech platforms, from navigation to e-commerce.

And that created an obvious tension: was SK Telecom being rewarded for this tech empire… or was it being penalized for being too complicated to understand?

The Rationale for the Split

SK’s answer was to split the company in two.

“The biggest purpose of the spin-off is to maximize shareholder value,” SK Telecom CEO Park Jung-ho said.

In 2021, shareholders approved a restructuring that SK described as the first major one since SK Telecom’s founding in 1984. The plan was straightforward: separate the steady, cash-generating telecom operator from the higher-volatility, higher-upside investment portfolio.

After the spin-off plan was finalized at the General Shareholders’ Meeting on October 12, 2021, the split took effect on November 1, 2021. SK Telecom would remain as the operating company, focused on AI and digital infrastructure. The newly created entity—SK Square—would become the group’s investment arm for semiconductors and information and communication technologies, or ICT.

What Went Into SK Square

SK Square didn’t start life as a blank check. It launched holding 16 of SK Telecom’s existing non-telecom and tech units. Most importantly, that included SK hynix. It also included assets like app market operator ONE Store, e-commerce platform 11Street, and T Map Mobility.

Even the name was meant to signal a new identity. SK Square positioned itself as a global ICT-focused investment company—one that would make aggressive bets spanning semiconductors and “future technology.”

The Ambitious Target

The goal was as ambitious as the rebrand. SK Square said it aimed to grow its net asset value to KRW 75 trillion by 2025, up from KRW 26 trillion, driven by new investments.

It also laid out the kinds of areas it wanted to fund next: quantum cryptography, digital healthcare, and future media content.

Mechanically, the new structure was simple: SK Square would hold the chips-and-tech portfolio, while SK Telecom would hold the mature telecom cash flows. In theory, that clarity should have helped investors price each business more cleanly.

In practice, as we’ll see, the opposite happened. The market looked at SK Square—and applied an even bigger discount to what it owned.

VII. The HBM Revolution: SK Hynix Becomes the AI Kingmaker

Then came the moment that turned an obscure product line into the choke point of the AI era: ChatGPT.

When OpenAI’s chatbot landed in late 2022, it didn’t just kick off a consumer craze. It triggered a buildout of AI training infrastructure on a scale the semiconductor industry hadn’t seen in years. And sitting right next to the most in-demand chips on earth—Nvidia’s GPUs—was a piece of hardware most people had never heard of: high-bandwidth memory.

HBM is specialized DRAM designed to move data at extreme speeds while staying power-efficient. If the GPU is the engine, HBM is the feed system that keeps it from starving.

And SK hynix had been preparing for this exact moment for a long time.

The Origins of HBM Leadership

Back in 2009, SK hynix started investing in the back-end technologies that make HBM possible—especially TSV and advanced packaging approaches like WLP. The company’s bet was that compute was going to get faster, models were going to get bigger, and conventional memory architectures would eventually become the limiting factor.

By December 2013, SK hynix had released the world’s first HBM based on TSV. That same year, HBM was adopted as a JEDEC industry standard (JESD235), after work proposed by AMD and SK hynix earlier in the decade. By 2015, high-volume manufacturing was underway at SK hynix’s facility in Icheon, South Korea.

The hard part wasn’t invention. It was timing.

For years, HBM was the right product for a market that didn’t quite exist yet. The high-performance computing ecosystem wasn’t mature enough, and adoption was slow. Internally, the HBM team hit a familiar moment in R&D-heavy industries: you’ve built something extraordinary, but you’re too early, and the business case is suddenly up for debate.

SK hynix didn’t walk away. The company stayed committed, in large part because it believed the HPC era was coming—and because by then it had already accumulated too much hard-won expertise to abandon the effort.

The AI Boom Validates the Bet

Around 2020, the tide started to turn. SK hynix’s persistence through HBM2E and then HBM3 met a market that was finally ready: AI and HPC workloads that were ravenous for bandwidth.

Once demand arrived, years of technical head start mattered. SK hynix scaled quickly and moved into the top position in HBM.

It also had a uniquely complete track record: SK hynix is the only company that has developed and supplied the full HBM lineup from the first generation, HBM1, through HBM3E—starting with that first commercial HBM release in 2013.

Market Dominance

By 2025, SK hynix’s HBM lead had become decisive. As of the second quarter of 2025, it held about 62% share of HBM supply. Samsung had fallen to about 17%, while Micron held roughly 21%.

This spilled over into the broader DRAM market, too. In the first quarter of 2025, SK hynix—long the number two player—took the number one spot in DRAM revenue share for the first time, reaching 36% according to Counterpoint Research. Samsung came in at 34%, and Micron at 25%.

Record Financial Performance

The financials followed the product. In 2024, SK hynix posted its best-ever annual results: ₩66.19 trillion in revenue, ₩23.47 trillion in operating profit, and ₩19.80 trillion in net profit—an operating margin of about 35% and a net margin around 30%. Revenues hit an all-time high, and the company swung hard from the prior year’s loss into deep profitability.

HBM became the centerpiece. In the fourth quarter, HBM accounted for more than 40% of total DRAM revenue, while enterprise SSD sales continued to climb. Reportedly, SK hynix’s HBM revenue in 2024 grew more than four-and-a-half times versus 2023.

Looking Forward

SK hynix has completed development of HBM4 and finished preparations for mass production.

And the broader setup remains the same: supply is expected to stay tight relative to demand into 2027, and SK hynix expects the AI memory market to grow at nearly 30% annually through 2030.

For SK Square, this is the punchline. The company isn’t just a holding vehicle with a semiconductor stake. It holds a piece of what has become one of the most valuable bottlenecks in the entire AI supply chain.

VIII. The Portfolio Beyond Semiconductors

SK hynix is the center of gravity in SK Square’s universe. But SK Square isn’t a single-asset wrapper. It also owns a collection of consumer and enterprise tech businesses—and they help explain both the upside story SK Square wants to tell, and the skepticism investors still price in.

The ICT Platform Companies

Start with 11STREET, SK Square’s e-commerce platform. The story here is less “rocket ship” and more “slow, painful rehab.” After years of losses, 11STREET focused on improving its profit-and-loss profile and cut its operating loss to KRW -9.7 billion, a 50% year-over-year improvement. More importantly, its refurbished open market business—built around higher-margin categories like food, fashion, and beauty—produced surplus operating income for 14 straight months, from March 2024 through April 2025.

Then there’s SK planet, the company behind the OK Cashbag loyalty platform. After pushing a set of initiatives to revitalize the core business—including launching a new membership program called Oki Club—SK planet swung into the black, posting KRW 8.3 billion in operating income in the first quarter of 2025. The company said it planned to further strengthen OK Cashbag’s competitiveness throughout 2025.

ONE Store, SK Square’s app market business, is still in the red—but it’s moving in the right direction. With improved marketing efficiency, ONE Store recorded an operating loss of KRW -3.2 billion, a 41% improvement year over year.

Portfolio Rationalization

At the holding-company level, SK Square said it planned to accelerate monetization of non-core assets in 2025—classic holding-company housekeeping: simplify the portfolio, free up capital, and reduce the “what exactly do you own?” confusion that feeds conglomerate discounts.

At the same time, it’s trying to lean into the moment. SK Square has positioned itself as an AI- and semiconductor-focused investment company and recently completed investments in five AI and semiconductor companies in the U.S. and Japan under a joint investment agreement with SK hynix, Shinhan Financial Group, and LIG Next1. In total, SK Square and its partners planned KRW 100 billion of investment, including KRW 20 billion already deployed into those five companies, with an emphasis on overseas tech businesses with high growth potential.

And it’s not just adding new bets—it’s actively reshuffling old ones. In the first quarter of 2025, SK Square rebalanced part of its portfolio by exchanging its stake in IDQ, a quantum-safe security company, for a stake in IonQ, the U.S. quantum computing company.

Taken together, these assets are exactly what you’d expect from a post-spin investment portfolio: a few turnaround stories, a few still-burning experiments, and a steady push toward “future tech” optionality. Some are improving. Some are still consuming capital.

But here’s the core issue for SK Square’s valuation: even if every one of these businesses executes perfectly, their combined value still gets dwarfed by the SK hynix stake—which makes SK Square’s persistent discount to net asset value feel even more counterintuitive.

IX. The Korea Discount & Activist Pressure

The Conglomerate Discount Problem

By now, the frustrating part of SK Square’s story should feel obvious. If it owns a stake in SK hynix—the AI memory kingmaker—why has the market been so stubborn about valuing SK Square at anything close to what its assets are worth?

The answer lives in a phenomenon so familiar it has a nickname: the Korea discount.

For years, South Korean public companies have traded at lower valuations than comparable peers overseas. Investors have often tied that gap to corporate governance: unclear capital allocation, structures that favor controlling shareholders, and a history of minority investors having limited leverage when interests diverge.

The numbers make the point. Over the decade from 2014 to 2023, Korean companies traded at price-to-book levels well below both developed-market and emerging-market averages. At the end of 2023, MSCI Korea sat around 1.1x price-to-book, versus about 2.4x for MSCI Taiwan and 1.4x for MSCI Japan. The discount showed up in earnings multiples, too.

And the roots run deep. Korea’s economy is dominated by chaebols—family-controlled conglomerates with complex ownership webs that can make outside shareholders feel like they’re investing alongside management, not with a real say in what happens next.

Politics plays a role as well. President Yoon publicly pushed market-related measures like a short-selling ban, and emphasized building “societal consensus” around Korea’s inheritance tax burden. That’s not a side issue. With inheritance taxes often cited in the 50% to 60% range, chaebol families face a constant pressure: how do you maintain control across generations without selling down ownership? The incentive, critics argue, can tilt toward preserving control rather than maximizing shareholder value.

So when SK Square trades at a steep discount to its net asset value, global investors don’t just see an anomaly. They see a familiar pattern—and assume the discount is structural.

Palliser Capital Enters

That’s the environment that attracted Palliser Capital.

Palliser is a UK-based activist fund founded in 2021 by James Smith, who previously ran Elliott Investment Management’s Hong Kong operations. The firm describes itself as a value-oriented activist manager, willing to work across the capital structure, with a bias toward opportunities in Asia and Europe. It manages over $1 billion.

Over the past couple of years, Palliser built a stake of more than 1% in SK Square, enough to place it among the company’s top ten shareholders—and then it started pushing.

The message was simple: if the market won’t close the gap on its own, SK Square should force the issue. Palliser called for more aggressive share buybacks and a sharper push into promising growth sectors. It also pressed for governance changes: adding board members with deeper asset-management experience and linking executive compensation more directly to performance. On capital structure, Palliser argued SK Square should lower its cost of capital by using more debt.

So far, sources have described meetings between Palliser and SK Square as “friendly.” But the subtext is clear: friendly is a phase, not a guarantee.

SK Square's Response

SK Square didn’t ignore the pressure. In November 2024, it announced a Corporate Value-Up Plan—a set of shareholder-friendly measures framed as a direct response to calls for value creation.

By the first quarter of 2025, the company reported improvement on several of its headline metrics. It said its net asset value discount rate had narrowed to 62.8%, down from 65.7% at the end of 2024 and 73.0% at the end of 2023. Over the same period, SK Square reported ROE rising from 21.7% to 27.6%, while its price-to-book moved from 0.62 to 0.68.

The targets were explicit: cut the NAV discount rate to 50% or below by 2027, generate ROE above its cost of equity over 2025 through 2027, and reach a price-to-book ratio of 1 or higher by 2027.

Whether those goals are achievable is one question. Whether the market believes SK Square will actually prioritize them, year after year, is the bigger one.

The Broader Reform Movement

What makes this moment different is that SK Square isn’t operating in a vacuum. Korea has been inching toward broader reform.

The National Assembly passed corporate governance changes aimed at strengthening minority shareholder rights and limiting the voting power of controlling families—reforms that investors have pushed for and many conglomerates have warned could create instability. The legislation passed with 180 votes in favor, and it includes a major requirement: large listed companies with assets above 2 trillion won must adopt cumulative voting.

The reforms were framed as part of a national push to tackle the Korea discount directly. They also align with a campaign pledge by President Lee, who vowed to lift the Kospi toward 5,000 by closing the valuation gap that has long haunted Korean equities.

For SK Square, this is the backdrop to everything: a structurally discounted market, an activist with a clear playbook, and a government that—at least on paper—now wants the discount gone.

The question is whether that’s enough to make investors finally believe what the balance sheet has been saying all along.

X. Playbook: Strategic & Business Lessons

Patience in Turnarounds

SK Square only exists because SK Telecom was willing to do something most “steady” companies don’t do: buy into a distressed, cyclical business and hold on long enough for the cycle to turn.

From the 2012 Hynix acquisition to the 2024 AI-memory boom is more than a decade of staying in the arena—funding capex, living through downcycles, and betting that the world would eventually need exactly what Hynix was best positioned to make. That’s what patient capital looks like when it works: not just buying low, but having the balance sheet and the stomach to wait.

Vertical Integration in the Digital Age

SK’s playbook has always been about controlling the bottleneck.

In the 1970s, it was “From Petroleum to Fibers”—own the inputs, own the economics. In the 2010s, that instinct reappeared in a modern form: telecom-to-semiconductors. When compute became strategic, the limiting factor wasn’t just processors. It was memory bandwidth. And in the AI era, SK hynix’s position in HBM didn’t just make it competitive—it made it essential.

The Spin-off Playbook

The 2021 spin-off was supposed to do the classic thing spin-offs promise: simplify the story and unlock value.

It definitely clarified the structure—one company for telecom operations, one for a tech-and-semiconductor portfolio. But the market’s response has been a reminder that clean org charts don’t automatically close valuation gaps. If investors believe governance and capital allocation will still favor the insider perspective, the discount can survive the restructuring. Structural clarity helps, but shareholder returns and credibility matter more.

Riding Technological Waves

SK’s history reads like a sequence of well-timed commitments: CDMA, then the mobile internet era, then platform services, and eventually the move into memory.

The pattern isn’t that SK predicts the future perfectly. It’s that when it commits, it commits early—before the market fully agrees—and then it invests long enough to be there when adoption finally arrives. That “early plus patient” combination is how you end up owning the boring component that suddenly becomes the most important part of the stack.

Chaebol Governance Trade-offs

The same structure that makes long-term bets possible can also be the reason outside investors demand a discount.

Family control and complex ownership can enable coordinated, multi-decade capital allocation—exactly what you need to build semiconductor leadership through cycles. But it also creates the governance concerns at the heart of the Korea discount: how cash gets deployed, how accountability works, and whether minority shareholders get the full benefit when the bets pay off.

That tension doesn’t resolve itself. It’s the ongoing trade: extraordinary patience and strategic consistency, priced against persistent skepticism about who the system ultimately serves.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Zoom out from the corporate structure and the activist headlines, and SK Square’s real question becomes simpler: how defensible is the thing it owns?

To answer that, it helps to run two classic strategy lenses on SK hynix: Porter’s 5 Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. Not because frameworks are magic, but because in memory semiconductors they make one point painfully clear: this is a brutal industry where advantages are rare, and right now SK hynix has several of the ones that actually matter.

Porter's 5 Forces for SK Hynix

The competitive dynamics of HBM and memory semiconductors are unusually favorable for a business that, historically, has been anything but.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. SK hynix is already a top-tier supplier in both DRAM and NAND, with roughly one-third share in DRAM and about one-fifth in NAND. To compete, a newcomer would need tens of billions of dollars for fabs, years of hard-won process expertise, and the ability to qualify with the world’s most demanding customers. In reality, no true new entrant has broken into memory at scale in decades.

Supplier Power: MODERATE. The toolmakers matter—especially at the bleeding edge, where scarce equipment like EUV systems can become a constraint. But scale cuts both ways. SK hynix is one of the few buyers big enough to matter, and that size gives it real negotiating leverage even in a supplier-concentrated world.

Buyer Power: LOW-MODERATE. Yes, the customer list is concentrated: Nvidia, Apple, the hyperscalers. But in HBM, the defining fact is capacity. With supply expected to remain tight relative to demand into 2027, and capacity effectively spoken for well ahead of time, buyers simply have less room to push pricing and terms the way they can in more balanced markets.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW. For modern AI training systems, there isn’t a clean substitute for what HBM does: extremely high bandwidth, low latency, and tight power efficiency, sitting right next to the GPU. If you want performance, you need the architecture—and if you need the architecture, you need HBM.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE. Memory is an oligopoly—Samsung, SK hynix, Micron—and that structure can be stabilizing. But it’s still memory: rivalry gets ugly when the cycle turns and everyone fights for utilization. The difference this time is that in HBM, SK hynix has held the lead, while Samsung has struggled to close the gap. That first-mover advantage matters most when demand is exploding and supply is constrained.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter tells you why the playing field looks the way it does. Helmer tells you what kind of advantage can last on that field.

Scale Economies: STRONG. Memory is the definition of a scale business. Bigger fabs, higher yields, more learning per wafer—everything pushes cost down with volume. SK hynix operates at the scale where those benefits compound.

Network Effects: WEAK. This isn’t software. Your choice of memory supplier doesn’t get better because someone else picked the same one.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE. The SK Square structure exists because the old structure wasn’t built for this. Separating telecom from an investment-led semiconductor portfolio made it easier to concentrate capital and attention where the opportunity was. And Intel’s repeated exits from memory—most recently NAND—underline the strategic opening SK hynix leaned into.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG. In HBM, “qualified” is everything. Once a memory stack is designed into a GPU platform and validated in production systems, switching suppliers isn’t a purchase order—it’s a requalification process that can burn cycles, risk performance, and jeopardize product timelines. That creates real friction, especially mid-generation.

Branding: MODERATE. Memory is still closer to an engineered component than a consumer brand. But in enterprise and datacenter markets, reputation for reliability, supply continuity, and execution does matter—and SK hynix has built credibility there.

Cornered Resource: STRONG. Dominant share in HBM and, just as importantly, the capacity to ship it at scale during an AI buildout, functions like a scarce resource. When everyone wants the same component at once, the supplier that can actually deliver becomes the one with leverage.

Process Power: STRONG. This is the quiet superpower. SK hynix began investing in TSV and advanced packaging back in 2009, released the first TSV-based HBM in 2013, and has been compounding know-how in 3D stacking ever since. In semiconductors, accumulated process learning doesn’t show up on a balance sheet—but it’s often the hardest advantage to copy.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull thesis is basically: the bottleneck stays the bottleneck.

First, SK hynix keeps its grip on HBM as AI infrastructure spending continues to compound. Demand is still being driven by the same hard reality: state-of-the-art GPUs don’t deliver state-of-the-art performance without HBM attached. Industry forecasts reflect that dynamic. HBM revenue in 2025 was expected to surge toward roughly the mid–$30 billion range, and Yole Group projects HBM growing at about a 33% CAGR through 2030—potentially becoming a massive portion of the broader DRAM profit pool.

Second, the discount closes. SK Square’s entire valuation debate is about whether the market will ever price it closer to the value of what it owns. As of 2025’s first quarter, SK Square said its NAV discount had improved to 62.8%, from 65.7% at the end of 2024 and 73.0% at the end of 2023. If Korea’s governance reforms actually change investor behavior—and if SK Square keeps pairing those reforms with credible capital returns—there’s a lot of room for the gap to narrow.

Third, the “other stuff” stops being dead weight. If portfolio companies like 11STREET and SK planet keep moving toward profitability, SK Square starts to look less like “a discounted Hynix stub plus distractions,” and more like an actual ICT investment platform with multiple sources of value creation.

Fourth, SK Square generates real returns on new AI and semiconductor investments. The company has been positioning itself as a specialized investor in these sectors; if those bets produce outsized winners, it gives the market a second reason—beyond just the hynix stake—to pay attention.

Bear Case

The bear thesis is just as intuitive: semiconductors giveth, semiconductors taketh away.

Memory cycles have always been vicious. If AI spending pauses, or if capacity ramps faster than demand, the market can swing from “allocation and premiums” to “oversupply and price cuts” in a hurry. Even within HBM, growth is expected to slow as the market matures—the blistering pace seen in 2024 and 2025 likely can’t last forever, with some expectations that growth could cool materially by 2026.

There’s also the competitive risk, and it’s not theoretical. Reports have suggested SK hynix remained the primary HBM supplier for Nvidia’s Blackwell, but that minor issues may have led Nvidia to prioritize Micron in some deployments. Those same reports also indicated SK hynix had been qualified on Blackwell Ultra with its 12-layer HBM3E and was still expected to be Nvidia’s primary supplier, partly because it could offer greater capacity. Even if these issues are “minor,” this is what the downside looks like in a bottleneck market: tiny performance or yield problems can become real share shifts when your customer is shipping at massive scale.

Then there’s Samsung. If Samsung closes the qualification and execution gap in HBM, SK hynix’s pricing power and market share could erode.

Finally, the structural drags remain. The Korea discount could persist even with reforms, especially if investors conclude chaebol incentives haven’t truly changed. Some of SK Square’s ICT assets could keep consuming capital longer than hoped. And geopolitical risk still hangs over the Intel NAND footprint—particularly the Dalian operations in China—at a time when tech supply chains are increasingly politicized.

Key Risks

One risk sits above all the others: concentration of control.

Chey Tae-won has been chairman of SK Group since 1998, and over time he has held top leadership roles across the empire—chairman of SK Innovation since 2011, chairman of SK hynix since 2012, and chairman of SK Telecom since February 2022. SK Group became South Korea’s second-largest corporate group during his tenure.

That kind of long-running, centralized leadership has benefits in a capex-heavy industry that rewards long-term commitment. But it also creates key-man risk and unavoidable succession questions. It also matters in the context of governance pressure: Palliser’s growing interest has come as SK has been reshaping its portfolio, in what has been described as an effort to secure cash without weakening Chairman Chey’s control over key affiliates.

Another persistent limitation is structural complexity. Cross-shareholding between SK Inc., SK Square, and SK hynix makes “clean” value realization harder than it looks on a spreadsheet—and as long as that’s true, some level of holding-company discount may remain rational.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you’re tracking SK Square, you can ignore most of the noise and keep your eye on three metrics that tell you whether the story is strengthening—or starting to crack.

1. SK hynix HBM revenue as a percentage of DRAM revenue. In the fourth quarter of 2024, HBM made up more than 40% of total DRAM revenue. This is the cleanest real-time signal for what matters most: how much of SK hynix’s DRAM business is shifting from “commodity memory” toward “scarce AI bottleneck.” If that mix keeps climbing and starts pushing toward half of DRAM revenue, it’s a sign that AI spending remains strong and SK hynix is holding its ground at the top of the stack.

2. SK Square’s NAV discount rate. As of 2025 1Q, SK Square said its net asset value discount stood at 62.8%. This is the scoreboard for everything the market cares about outside the fabs: governance credibility, capital returns, and whether the holding-company structure is actually going to work for minority shareholders. SK Square’s stated goal is to push that discount below 50% by 2027.

3. SK hynix operating margin. In 2024, SK hynix reported operating profit of ₩23.4673 trillion, an operating margin of about 35%. Memory margins are famously cyclical—SK hynix was unprofitable in the 2023 downturn—so the question is whether this level is a temporary peak or a new plateau driven by HBM mix and sustained tight supply. If margins can hold above 30% for a stretch, that starts to look less like a cycle and more like structural advantage.

The story of SK Square is really about patience, positioning, and the difficulty of turning value on paper into value for shareholders inside Korea’s chaebol system.

A holding company trading at a fraction of the value of its biggest holding is either an extraordinary opportunity, a stubborn governance discount that refuses to budge, or—most likely—some combination of both. What’s hard to argue with is the industrial reality: SK hynix’s long bet on HBM put it in the middle of the AI infrastructure buildout at exactly the moment the world decided it needed to scale AI.

Whether investors can actually capture that value through SK Square depends on much more than semiconductor execution. It hinges on whether governance reforms have teeth, whether activist pressure forces sharper capital discipline, and whether the Korea discount finally starts to shrink—or proves, once again, that it can outlast even the best operating performance.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music