Resonac Holdings: From Fertilizers to AI Chip Dominance

I. Introduction: The Hidden Giant Behind the AI Revolution

Picture the AI boom up close. A developer spins up another training run on NVIDIA’s latest GPUs. A hyperscaler orders more high-bandwidth memory to feed the models. Somewhere in South Korea or Taiwan, factories stack layer after layer of memory dies with tolerances so tight they’re measured in microns.

And inside those stacks is a material that almost nobody talks about: a non-conductive film, used to bond layers together while keeping the whole structure electrically insulated. It’s unglamorous, invisible, and absolutely essential. One Japanese company supplies roughly half of it worldwide.

That company is Resonac Holdings.

On paper, Resonac looks like a mid-sized chemicals player. Its market capitalization sits around $6.11 billion. But in the way modern supply chains actually work, Resonac occupies one of those strange, powerful positions where a company you’ve never heard of ends up controlling a chokepoint for industries worth trillions.

The tell is what Resonac decided to do next: ramp production for the materials that go into high-performance chips used mainly for AI. The company planned to expand capacity for two key products—non-conductive film (NCF) and thermal interface materials (TIM)—to several times its current level, rolling out the added capacity step-by-step starting in and after 2024. These aren’t speculative science projects. These materials have already been adopted by customers building the hardware that runs modern AI.

NCF sounds like packaging tape until you understand the job. It’s used in the back-end processes that connect and stack multilayer high-bandwidth memory (HBM). HBM is the memory architecture that makes today’s AI accelerators viable at all—because without fast, dense memory stacked right next to the compute, the whole system starves. Every HBM stack needs a reliable way to bond layers without short-circuiting. That’s the quiet, high-stakes niche where Resonac dominates.

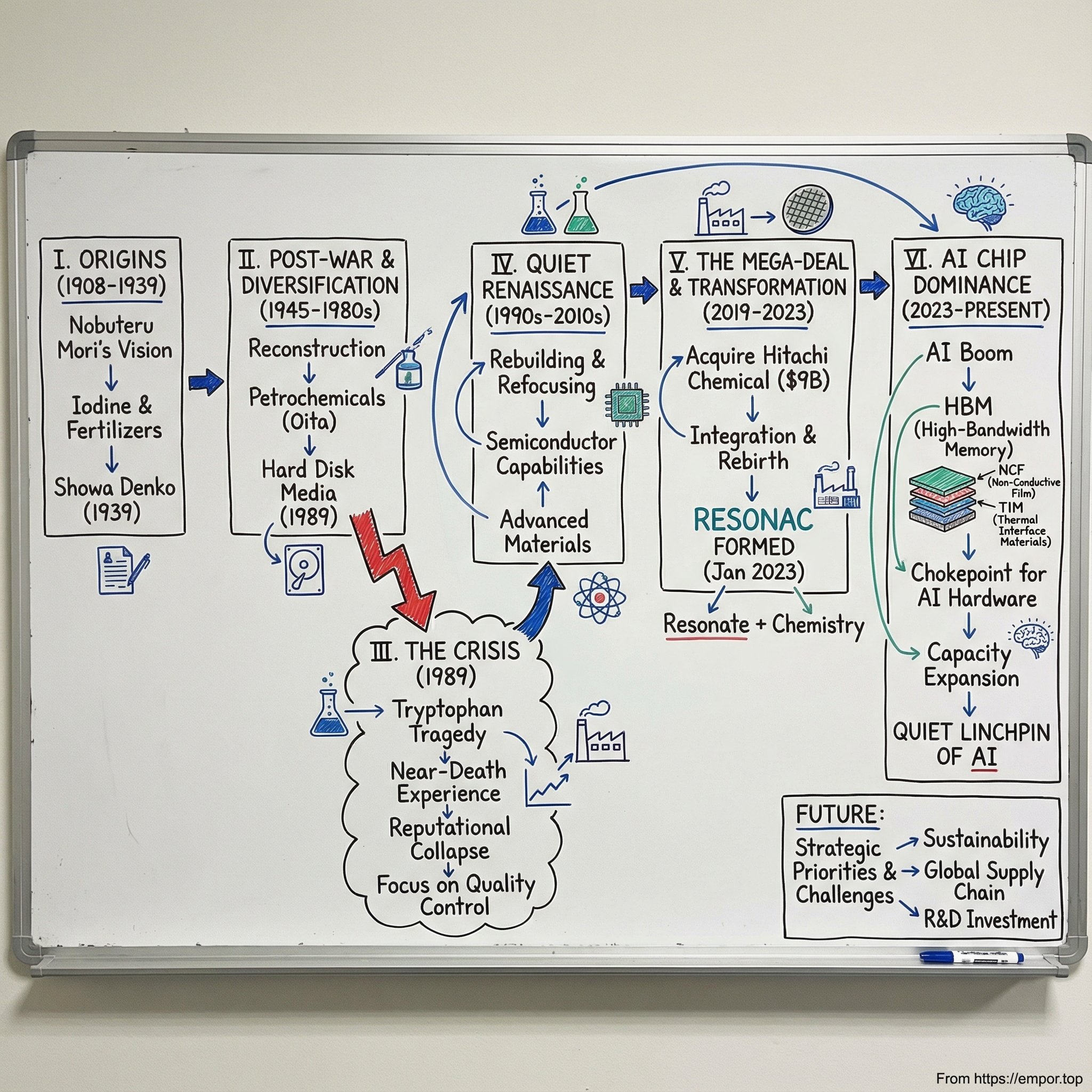

Now for the twist: Resonac didn’t arrive here by riding a trendy wave from day one. This company’s roots go back to 1908—when “computing” meant a person with a notebook—and to its founder, Nobuteru Mori, extracting iodine in rural Chiba Prefecture. From iodine to fertilizers, fertilizers to chemicals, chemicals to electronics materials, and then into the guts of the AI supply chain. Resonac is the rare industrial story that’s less about invention in a flash, and more about reinvention as a habit.

The Resonac name itself only appeared recently. In January 2023, Showa Denko K.K. and Showa Denko Materials Co., Ltd. integrated to form the Resonac Group. “Resonac”—a blend of “resonate” and “chemistry”—was a statement of intent: a new identity built around combining material design with a broad base of industrial manufacturing know-how.

But that “new start” was powered by one of the boldest corporate moves in modern Japan: Showa Denko’s roughly $9 billion acquisition of Hitachi Chemical in 2020. It was the kind of deal that makes markets nervous for a reason—Showa Denko was effectively betting the company to buy a larger rival and transform what it could be.

And the stakes weren’t just financial. This is also a company that had already stared down an existential crisis. In 1989, Showa Denko became linked to a tryptophan contamination disaster in the United States, an epidemic that resulted in thousands of cases of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome and dozens of deaths. The fallout was devastating: years of litigation, enormous settlements, and a reputational collapse that could have ended the story right there.

Instead, the company rebuilt—slowly, methodically—and ultimately positioned itself in exactly the kind of “picks and shovels” role that tends to matter most during a gold rush. Chipmakers get the headlines. Materials companies get embedded in the process, qualified over years, and then become very hard to replace.

So that’s the central question we’re going to chase: can a company built for the petrochemical age truly become a backbone supplier for the AI age—and stay there as this boom shifts from frenzy to an industry?

Let’s find out.

II. Origins: The Mori Vision and Japan's Industrial Awakening (1908–1939)

In December 1908, on the coast of Chiba Prefecture east of Tokyo, a young entrepreneur named Nobuteru Mori started a company with a simple, gritty purpose: extract iodine and sell it. He called it Sobo Marine Products K.K. It was the kind of business that sits at the base of an industrial pyramid—chemistry, logistics, and patience. Over time, Sobo Marine Products would evolve into Nihon Iodine K.K.

Mori’s timing mattered. Japan, barely half a century removed from reopening to the West, was sprinting through industrialization. The Meiji state had made modernization a national obsession: build domestic capability, reduce reliance on imports, and catch the great powers. “Industrial self-sufficiency” wasn’t a slogan; it was policy, prestige, and, increasingly, security.

Mori fit that moment. He would later be associated with a motto: “Dauntlessness and Indomitableness”—an insistence on pushing into new fields and taking adversity head-on. It reads like corporate wallpaper until you look at what he actually built. Mori didn’t just start a business. He started stacking capabilities.

Once the iodine operation established him as a serious industrialist, Mori moved into a product with far bigger implications for the country: fertilizer. In April 1928, he established Showa Fertilizer K.K. Three years later, in April 1931, Showa Fertilizers opened Japan’s first ammonium sulfate factory.

That was a breakthrough. Ammonium sulfate was one of the workhorse fertilizers of the industrial age, a way to turn chemistry into food supply. Producing it domestically meant Japan was no longer dependent on imported inputs to raise agricultural yields—an advantage that also carried obvious strategic weight in a world sliding toward conflict.

From there, Mori broadened his scope. He founded Nihon Yodo (later Nihon Denki Kogyo) and Showa Hiryo, and pushed into electrochemical industry—branching into the adjacent necessities that make heavy industry possible: power, mining, and materials. This expanding cluster of companies became known as the Mori Konzern, a pre-war-style industrial conglomerate built for scale and resilience.

In 1939, Mori merged Nihon Denki Kogyo and Showa Hiryo to form Showa Denko, and became its first president. The new company combined operations across electrochemicals and materials—spanning inorganic chemicals, organic chemicals, and metallic materials—positioning it as a wide-spectrum industrial supplier right on the eve of World War II.

Even the name captured the ambition. “Showa” referenced the era itself—the reign of Emperor Hirohito. “Denko” drew on the characters for electricity and industry. This was a company named for its time, built around the idea that electricity, chemistry, and materials could be industrial power.

That origin story also explains a difference in operating DNA. Showa Denko wasn’t born as a scrappy startup trying to find product-market fit. It emerged from a system where industrial firms often served national goals, where government policy shaped markets, and where planning horizons ran in decades.

And it sat inside a broader Japanese structure that would later matter enormously: the keiretsu. Keiretsu are networks of companies linked by long-standing business relationships and cross-shareholdings, typically organized around a core bank. The system helped insulate member companies from hostile takeovers and short-term market pressure, enabling long-term investment and coordination.

Showa Denko would ultimately be associated with the Mizuho keiretsu. That banking relationship would become a quiet but crucial part of the company’s capacity to make big, long-horizon moves—including, many decades later, financing the acquisition that helped create modern Resonac.

Mori’s foundation—electrochemistry, materials know-how, and long-term institutional support—turned out to be remarkably durable. But before any of it could evolve into semiconductor relevance, the company had to make it through war, reconstruction, and then, much later, a crisis that nearly ended the story entirely.

III. Post-War Reconstruction and Diversification (1945–1980s)

The Japan that emerged from World War II barely resembled the industrial power Nobuteru Mori had helped build. Cities were burned out. Factories were shattered. And the U.S. occupation initially aimed to dismantle the giant conglomerates—zaibatsu—that had anchored Japan’s wartime economy.

Out of that upheaval came something new. The zaibatsu were partially broken up, but not fully erased. As Cold War priorities took over, the United States pivoted toward rebuilding Japan as an industrial counterweight to communism in Asia. The result was a reorganization rather than a clean demolition: looser corporate groupings, less defined by family ownership, more defined by webs of banks, suppliers, and trading partners. This is the environment in which the prototypical keiretsu took shape.

For Showa Denko, that reversal mattered. It didn’t get carved into pieces. Instead, it adapted to postwar capitalism and started rebuilding with speed and discipline. In May 1949, Showa Denko listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. In September 1951, it won the first Deming Prize.

That award is easy to skim past, but it’s a signal. The Deming Prize is Japan’s most prestigious quality honor, tied to the ideas that helped turn Japanese manufacturing into the global benchmark. Showa Denko wasn’t being recognized for glamorous products. It was being recognized for operational rigor—process control, consistency, and a culture of improvement. Those capabilities don’t stay in one factory line; they compound across everything a company does.

The timing was perfect. The 1950s and 1960s became Japan’s “economic miracle,” a period when growth was so fast it rewrote the country’s role in the global economy. Japan moved from exporting silk and cotton to exporting cars, cameras, and electronics. The keiretsu system—stable financing, long relationships, coordination across industries—helped fuel that rise.

Showa Denko rode the wave by becoming something broader and sturdier than its prewar self: a diversified chemical and materials supplier that could plug into almost any industrial build-out. Its biggest statement of that era was petrochemicals. In April 1969, the Oita Petrochemical Complex began commercial operations. By March 1977, the complex had completed a second expansion of ethylene capacity.

Oita became the backbone. The petrochemicals business manufactured and sold organic chemicals, olefins, and specialty polymers, and Showa Denko built a leading position in the Asian ethyl acetate market. The Oita plant supplied basic materials not just to Showa Denko, but to other chemical companies as well—inputs for acetyl derivatives, synthetic resins, synthetic rubber, and styrene monomers.

This is the part of the story that looks like a traditional chemical conglomerate: big plants, big volumes, big steady demand. But it mattered because it created something Showa Denko would later need desperately: reliable cash flow and a manufacturing base strong enough to support long-term bets.

And the company didn’t stop at petrochemicals. As the decades rolled on, it expanded into aluminum, industrial gases, and ceramics, and began building the early shape of what would later become its defining edge: electronic materials. Along the way, it introduced products like high-purity alumina in the 1960s—material that would become important to the semiconductor industry.

By 1980, the diversification engine was still running. Showa Denko became the first Japanese company to produce high-strength carbon fibers, opening doors to demanding applications like aviation and automotive. This wasn’t commodity chemistry anymore. This was advanced materials, where performance and quality mattered at the margins—and where customers were far stickier.

Then came another step toward precision manufacturing. In November 1989, Hard Disk Plant No. 1 was completed in Chiba, marking the company’s entry into hard disk media.

Hard disk media was a very different game than petrochemicals. Chemicals often reward scale and cost. Hard disk media rewards control—how magnetic layers behave, how surfaces are engineered, how defects are eliminated. It’s materials science performed at tight tolerances and under constant pressure to improve. In hindsight, it was training for the future: the kind of capability you need if you’re going to supply the semiconductor industry.

By the late 1980s, Showa Denko had built an unusual portfolio: commodity chemicals for stability, industrial materials for breadth, and early electronics-adjacent businesses for upside. The ingredients for transformation were sitting on the table.

And then, from a corner of the company that didn’t look strategically important at all, came the shock that nearly ended the story.

IV. The Tryptophan Tragedy: Near-Death Experience (1989–1991)

In the fall of 1989, doctors in New Mexico began seeing patients with a baffling mix of symptoms: intense muscle pain, unusually high eosinophil counts, skin thickening, and a kind of creeping weakness that wouldn’t let up. It didn’t look like anything standard. Then the cases spread. What first seemed like medical noise started to rhyme.

Before long, investigators had a suspect: L-tryptophan, a popular dietary supplement sold across the United States in health-food stores and vitamin aisles. People took it for insomnia, depression, and weight control. And for years, it had been treated as benign.

The illness would come to be known as eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, or EMS. The epidemic peaked in October 1989 and then collapsed almost as quickly after the FDA issued a recall on November 17, 1989. That pattern—sudden rise, sudden disappearance—pointed to a classic culprit in public health: contamination.

Here’s the detail that mattered for Showa Denko. Bulk L-tryptophan at the time was manufactured by multiple companies in Japan, imported into the U.S., and then repackaged into thousands of branded products by hundreds of distributors. But as the evidence accumulated, one source stood out. Scientific studies would strongly support the conclusion that the contaminated tryptophan came from a single primary manufacturer: Showa Denko K.K. in Tokyo.

Showa Denko hadn’t gotten into tryptophan because it wanted to be a health brand. It got in because it was a chemicals company—and fermentation-based amino acid production was a chemistry and process-control problem, the kind industrial firms know how to scale. In the early 1980s, Showa Denko began producing L-tryptophan using bacterial fermentation. By the end of the decade, it held a substantial share of global supply.

And then, in the pursuit of higher yields, the company made a series of changes that would define the next chapter of its history.

Later analysis of Showa Denko’s manufacturing procedures found several protocol changes made between December 1988 and June 1989. Among them: the introduction of a new, genetically altered bacteria strain—strain V of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens—intended to boost tryptophan output.

Output went up. But the product stream changed too.

Researchers focused on trace impurities, including one associated with a chromatographic signature known as peak E (sometimes referred to as EBT), which appeared strongly linked to the injuries. The underlying argument has never fully died: whether genetic engineering itself was the root cause, or whether other process changes—like purification and filtration decisions—allowed harmful impurities to slip through. Showa Denko denied that GMOs were the cause, pointing instead to non-genetic-engineering-related changes in production.

What isn’t debated is what happened next.

Thousands of people became seriously ill. Reports cited more than 1,500 cases and 27 deaths, and legal estimates suggested even more victims entered negotiations without filing. EMS wasn’t a temporary reaction. It was described as a painful, progressive multi-system disease—marked by severe muscle pain and elevated eosinophils, and capable of causing lasting scarring and fibrosis in nerve and muscle tissue along with chronic inflammation and long-term immune disruption.

The legal fallout was massive. Roughly 1,000 lawsuits were filed in the United States, with additional claims handled through negotiations. Many cases settled out of court with confidentiality agreements, which kept the story quieter than you might expect given its scale. But the cost to Showa Denko wasn’t quiet. Estimates vary, but settlements ultimately added up to the low billions of dollars.

For a mid-sized Japanese chemicals company, that’s not just a hit. That’s an extinction-level event.

And the most brutal part was the technical nuance. The contaminated tryptophan met the USP standard for purity. It was more than 99% pure. But in biology, “almost pure” can be lethal. Trace contaminants—present at parts-per-million levels—were enough to trigger devastating outcomes.

That’s why the tryptophan tragedy became more than a financial disaster. It rewired the company.

The lesson wasn’t “follow the standard.” The lesson was that standards can lag reality, and that process discipline has to be more conservative than the rulebook—especially when you’re making something that enters the human body. In the aftermath, quality control became a defining obsession. The company stepped away from consumer-facing health products and refocused on industrial domains where its materials capabilities could create value without the same catastrophic exposure.

And there’s an irony here that only shows up in hindsight. The crisis was born from a problem of purification—of trace impurities hiding inside an otherwise “clean” product. That is exactly the kind of problem semiconductor materials companies live and die by. In chipmaking, impurities at even smaller levels can wreck yields. The tryptophan episode burned into Showa Denko an institutional respect for what invisible contaminants can do.

Showa Denko survived—financially weakened, reputationally shaken, but culturally hardened. It had learned what near-extinction felt like. And that experience would quietly shape how it approached the next decades, when it began rebuilding itself into something far closer to today’s Resonac: a company engineered around precision, process control, and materials that the modern world can’t run without.

V. The Quiet Renaissance: Building Semiconductor Capabilities (1990s–2010s)

In the 1990s, while the business world fixated on the internet boom—and then the bust—Showa Denko was doing something far less fashionable and far more durable. It was remaking itself. Step by step, it began shifting from a broad, often commodity-oriented chemical producer into a company whose future depended on precision materials for the digital economy.

The hard disk media business, launched with that 1989 plant in Chiba, became the proving ground. Hard drives are not “just” metal platters. They’re engineered surfaces, thin films, coatings, and defect control—all the disciplines that separate traditional chemical manufacturing from modern electronics materials.

Then, in 2005, Showa Denko hit an inflection point. In July of that year, it began producing the world’s first hard disk media using perpendicular magnetic recording technology.

The breakthrough was driven by a looming physics wall. Traditional hard drives stored data by magnetizing tiny regions horizontally—along the surface of the disk. But as manufacturers pushed to pack more bits into the same area, those magnetic domains became so small they could no longer hold their orientation reliably. The industry was running into what’s known as the superparamagnetic limit: a threshold where the stored data starts to “forget” itself.

Perpendicular recording flipped the geometry. Instead of laying bits flat, it oriented magnetization vertically. That change, simple to describe and brutally hard to execute, pushed the limits of areal density forward right when horizontal recording was running out of road.

Showa Denko didn’t just publish a paper or demo a prototype. It commercialized the technology—turning an idea that had been championed for years by Professor Shun-ichi Iwasaki at Tohoku University into real product that drive makers could qualify and ship. And in the long arc of this story, that matters more than being clever. It proved the company could translate frontier materials science into high-volume manufacturing.

The win fueled expansion. In 2003, Showa Denko entered Singapore by acquiring Mitsubishi Chemical Group’s hard disk media plant there. In 2009, Fujitsu Limited and Showa Denko announced a memorandum of understanding to transfer Fujitsu’s hard disk drive media business to Showa Denko.

Inside the company, this era was framed by a strategic idea Showa Denko called “KOSEIHA.” The goal was to build a portfolio of KOSEIHA businesses—operations that could maintain profitability and stability at high levels over long periods. The hard disk media unit was positioned as one of the core examples. As the world’s largest independent supplier of hard disk media, Showa Denko kept pushing next-generation recording technologies into the market, competing on performance and reliability rather than on price alone.

That KOSEIHA philosophy is worth pausing on, because it sounds like internal branding until you see how it shaped decisions. The intent was to avoid businesses where everyone can make roughly the same thing, and instead dominate niches where customers can’t easily switch—because qualification is painful, performance is hard-won, and failure is expensive.

At the same time, Showa Denko was assembling the other half of the future: semiconductor materials. The company had long been in industrial gases and chemicals, but it increasingly oriented those capabilities toward electronics—offering high-purity gases and chemicals used in semiconductor manufacturing. And as chipmaking concentrated across Asia, Showa Denko followed, establishing overseas specialty-gas production sites in places like Shanghai and Singapore.

The portfolio kept tightening around advanced materials. In March 2001, Showa Denko merged with Showa Aluminum Corporation, strengthening its materials base and manufacturing depth.

By the mid-2010s, the company looked very different than it had in the wake of the tryptophan crisis. It had leadership in hard disk media, growing exposure to semiconductor-grade gases and chemicals, compound semiconductor capabilities including LED chips, and a broader bench of ceramics and specialty chemicals that were increasingly tied to electronics.

But management could see the next constraint coming—and it wasn’t technical. It was scale. The global semiconductor materials industry was consolidating, and competitive pressure was rising as manufacturers in China improved and expanded. Even sophisticated products can get dragged toward commoditization when rivals can outspend you and out-scale you.

If Showa Denko wanted to be a long-term winner in the materials layers underneath the next computing wave, it needed to get bigger, faster. And that set the stage for the move that would redefine the company: Hitachi Chemical.

VI. The Mega-Deal: Acquiring Hitachi Chemical (2019–2020)

In December 2019, Showa Denko announced a move that jolted Japan’s industrial world awake. It would buy Hitachi Chemical, the chemicals unit of Hitachi Ltd., in a deal valued at up to 964 billion yen, about $8.8 billion.

This wasn’t “bolt-on acquisition” territory. Showa Denko—Japan’s No. 3 diversified chemical supplier—agreed to pay more than double its own market value to acquire a larger rival. And it planned to do it mostly with debt. The message was clear: this wasn’t about smoothing out a portfolio. It was a full-body transformation, aimed at scaling up in lithium-ion battery materials and advanced materials, and keeping pace as global competition intensified.

If you want the mood of the moment, it’s this: either Showa Denko was making a generational, strategically necessary bet—or it was walking straight into a leverage trap.

The company’s public rationale was blunt about why scale suddenly mattered so much. “Chinese material manufacturers have developed a business that takes advantage of the economies of scale and Middle East material manufacturers have also been increasing cost competitiveness,” Showa Denko said. In other words: the floor was dropping out of the middle of the industry. If you weren’t a leader in something defensible, you were going to get squeezed.

From Showa Denko’s perspective, the logic was simple even if the execution was anything but. Semiconductor and electronics materials were becoming a game of narrow choke points. The winners would be companies that could fund relentless R&D, meet unforgiving quality requirements, and support the world’s most demanding customers. Everyone else would drift toward commodity competition, where scale and cost win.

Management believed combining with Hitachi Chemical would create the kind of breadth and heft that could compete globally, while also cutting costs by removing overlap. The company anticipated synergies of around $825 million over three years.

To understand why Hitachi was willing to sell, you have to look at Hitachi’s own evolution. Hitachi had been shedding businesses to focus on equipment and data services tied to internet-of-things technologies. Hitachi Chemical, despite its strong portfolio, wasn’t central to that future. For Hitachi, the sale was strategic housekeeping. For Showa Denko, it was identity-altering.

And Hitachi Chemical wasn’t some sleepy asset. It manufactured and sold a wide range of electronic materials, plastic polymers, automotive products, and other chemical-related products. Its advanced components and systems segment—its largest—sold automotive products, batteries, printed circuit boards, capacitors, and diagnostics equipment. Its functional materials segment sold semiconductor and electronics films, polymers and resins, lithium-ion battery materials, carbon products, and ceramics. Most of its revenue came from Asia, where the semiconductor supply chain was already concentrating.

Still, skeptics piled on immediately.

Jefferies analyst Yoshihiro Azuma came out negative on the deal, focused on the debt load and unimpressed by the synergy story. His critique cut deeper than “too expensive”: he didn’t see much product overlap, which made the integration thesis harder to believe.

Ratings agencies were also wary. Japan Credit Rating Agency warned that even with a structure designed to reduce direct burden, deterioration in Showa Denko’s financial structure would be unavoidable.

The financing plan showed just how hard Showa Denko was trying to thread the needle: raise an enormous amount of capital without issuing common equity. To fund the purchase, Showa Denko sought a 295 billion yen loan from Mizuho Bank and planned to sell preference shares to Mizuho Bank and the Development Bank of Japan—explicitly avoiding a common-share offering.

Under the acquisition vehicle, the Tender Offeror planned to fund settlement by borrowing up to 400 billion yen from Mizuho Bank, taking up to 275 billion yen via subscriptions of Class A preferred shares from Mizuho Bank and the Development Bank of Japan, and receiving up to 295 billion yen via subscriptions of the Tender Offeror’s common shares.

This is where the earlier keiretsu context stops being background and starts being plot. The Mizuho relationship—built over decades—made this kind of leveraged, high-conviction transaction possible. Showa Denko could do it because its main bank was willing to show up not just with loans, but with preferred equity too.

Then the world changed.

The tender offer began on March 24, 2020, and completed on April 20, 2020. Hitachi Chemical became a consolidated subsidiary of Showa Denko on April 28, 2020, after its shares were acquired by HC Holdings K.K., a wholly owned subsidiary of Showa Denko.

April 2020 was the height of pandemic uncertainty. Markets were swinging wildly, supply chains were breaking in real time, and nobody could confidently say what demand would look like—even in semiconductors. Showa Denko closed an almost $9 billion acquisition when the global economy’s trajectory was genuinely unknown. Whatever you think about the deal, there’s no denying the nerve it took to finish it.

After the acquisition, Hitachi Chemical took on a new identity inside the group as Showa Denko Materials Co., Ltd.—positioned as a one-stop advanced materials partner. The stated intent was to combine Hitachi Chemical’s material design and functional evaluation capabilities with Showa Denko’s wide-ranging materials technology, and build a global top-class manufacturer of functional chemical materials and products.

On the ground, the combined portfolio suddenly looked like a semiconductor supply chain map. Showa Denko brought high-purity gases, hard disk media expertise, and compound semiconductors. Hitachi Chemical brought strengths in CMP slurries, semiconductor packaging materials, and electronic films. Together, they could claim coverage across much of semiconductor manufacturing—stretching from wafer-side processes through packaging.

But buying the pieces isn’t the same as building the machine.

A deal this big only works if integration works: aligning cultures, rationalizing operations, delivering the promised synergies, and convincing customers that the combined company will be even more reliable than the two were separately. That would be the real test of whether Showa Denko had made the defining move of its century—or simply taken on defining risk.

VII. The Integration and Rebirth as Resonac (2020–2023)

If buying Hitachi Chemical was the thesis, integration was the exam. Showa Denko and Showa Denko Materials—the former Hitachi Chemical—had to turn a blockbuster deal into a coherent company. And in January 2023, they made it official: the group would operate as Resonac.

On the surface, Resonac still looked like a classic Japanese chemicals and materials house—petrochemicals, chemicals, carbon, ceramics, aluminum products, hard disk media, and electronic materials serving a wide range of industries. But under the hood, the integration was designed to do something much more specific: concentrate the company around higher-value, harder-to-replace materials, especially for semiconductors.

That was easier to declare than to do. The two organizations came with very different operating DNA. Showa Denko had a reputation for entrepreneurial deal-making. Hitachi Chemical carried the more conservative, process-heavy imprint you’d expect from decades inside one of Japan’s largest industrial conglomerates. Now add the real-world timing: the acquisition closed in April 2020, right as the pandemic whipsawed demand and complicated everything from factory operations to customer forecasting. Combining cultures and systems in that environment took more than project management. It took conviction.

A lot of that conviction came from Hidehito Takahashi. After joining Showa Denko in 2015, he rose through strategy roles—serving as Chief Strategy Officer from 2020—and became CEO in 2022. In 2023, he oversaw the launch of Resonac and pushed the company through a sharp turn: divesting 13 non-core businesses and tightening the strategic center of gravity around semiconductor materials.

Takahashi also didn’t fit the stereotype of a traditional Japanese industrial CEO. He had held management positions at GE Japan Holding Corporation and other foreign companies, and brought a more global, execution-first style to the role. Internally, the message was straightforward: integration wasn’t the work. Integration was the prerequisite for change.

The name change was meant to make that change legible. “Resonac”—a blend of “resonate” and “chemistry”—was positioned as a clean break from the past, and a signal of what the combined group wanted to be: a materials company that could offer better solutions by pairing Hitachi Chemical’s material design and functional evaluation strengths with Showa Denko’s wide-ranging manufacturing and materials technologies.

The portfolio work followed the same logic. Businesses that didn’t fit the new focus were put up for sale—deliberately and systematically. Resonac’s stated goal was to optimize how management resources were allocated, continuously review and reshape the portfolio, and use integration to spur innovation by combining the two predecessors’ technologies. The divestitures weren’t framed as fire sales; the company emphasized transferring assets in a condition that preserved value and matched them with owners better positioned to grow them.

That approach was consistent with the “Long-term Vision for Newly Integrated Company (2021–2030)” announced on December 10, 2020: build a global top-class functional chemicals manufacturer, and revise the portfolio accordingly.

One clear example came from the regenerative medicine business inherited from Hitachi Chemical. Minaris, a contract development and manufacturing organization, provides cell therapy manufacturing services and regenerative medicine products for pharmaceutical and biotech customers globally. Resonac’s management decided to pursue a deal with Altaris, concluding that Altaris—an investor with more than 20 years of healthcare focus—had the sector expertise and resources to support Minaris through its next phase of growth, and that the business would be better served under that ownership.

The subtext was unmistakable. This was a break from the traditional Japanese conglomerate instinct to hold everything forever. Resonac was willing to get smaller in places where it couldn’t be great, so it could concentrate investment where it could.

What emerged was a cleaner structure and a sharper story. Resonac would describe itself as a group of chemical companies spanning semiconductor and electronic materials, mobility, innovation-enabling materials, and chemicals—built on a deep base of material resources and advanced technologies that sit in the midstream to downstream parts of many global supply chains.

And the ambition didn’t stop at internal cleanup. “I believe we are the most logical partner for JSR,” said the executive who had orchestrated the Hitachi Chemical acquisition that led to Resonac’s formation—an offhand line in a conversation about further consolidation in semiconductor materials, but a revealing one. The point wasn’t that a specific deal would happen. It was that Resonac saw itself as a platform: built to integrate, built to scale, and built to keep consolidating where it could create durable leadership.

By the time the Resonac name went on the door in 2023, the company looked meaningfully different than the one that announced the Hitachi Chemical deal three years earlier: a more focused portfolio, a leadership team with global experience, and—most importantly—strong positions in the kinds of materials that were about to become mission-critical as the AI semiconductor boom accelerated.

VIII. The AI Chip Opportunity: Riding the Wave (2023–Present)

When ChatGPT launched in November 2022 and set off the current AI boom, Resonac was already standing in the right place.

Not because anyone at Showa Denko had predicted large language models years in advance. The Hitachi Chemical acquisition closed in 2020, long before “AI chips” became a household phrase. Resonac was positioned to win for a more durable reason: the bottlenecks in AI hardware were forming in exactly the kinds of materials and processes the company had been quietly building for decades.

So Resonac made the obvious move. It decided to expand capacity for materials used in high-performance semiconductor chips—especially those used mainly as CPUs for AI—by roughly 3.5 to 5 times from its then-current level. The focus was two products that had already been adopted by customers: non-conductive film (NCF) and thermal interface material (TIM). Resonac planned to invest 15 billion yen in facilities for these materials, bringing the expanded capacity online step-by-step starting in and after 2024. The bet was aligned with the market’s direction: AI chip demand in 2027 was expected to be about 2.7 times what it was in 2022.

To see why NCF and TIM matter, you have to zoom in on what makes AI hardware different. Traditional chips can get away with relatively modest memory bandwidth. Training large models can’t. Modern AI accelerators live and die by how fast they can move data, which is why high-bandwidth memory—HBM—has become so important. HBM stacks multiple memory layers vertically and connects them through microscopic pathways called through-silicon vias. That stacking is a packaging problem as much as it is a silicon problem.

NCF sits right in the middle of it. It’s used to connect and stack the multilayers of HBM that go into those high-performance packages. It has to bond reliably, maintain insulation, and hit incredibly tight thickness requirements—tolerance measured in less than microns.

That’s hard to appreciate until you think about what “less than microns” means in a factory. You’re coating and bonding at a scale where tiny variation isn’t a defect; it’s a yield killer. The film has to be thin and consistent, but also strong, electrically safe, and durable across the heat cycling of real chip operation. If it fails, an HBM stack fails. And if an HBM stack fails, the whole accelerator fails.

Resonac’s advantage is that, for them, NCF wasn’t a cold start. The company had years of development and production experience in die-bonding film—a predecessor technology—and it used that accumulated know-how to meet NCF’s quality requirements. In other words, the dominance wasn’t luck. It was adjacent mastery, carried forward.

Just as important, NCF isn’t the only hook. Resonac has a lineup of products that spans a wide range of semiconductor processes, from front-end to back-end, including several that hold top market share positions. That matters because the industry is changing in a way that can make a materials supplier grow faster than the chip count itself: as integration rises, the number of components and materials per package rises too.

This is one of the quiet engines of the AI era. The front-end—shrinking transistors—has become harder and more expensive to push. As those gains slow, the industry is leaning harder on back-end innovation: chiplets, 2.5D and 3D packaging, and advanced mounting techniques that squeeze more performance out of how chips are assembled rather than just how they’re etched.

Resonac has been explicit about what that shift means for them. With limits to density increases in front-end processes becoming more apparent, attention is turning to higher integration through back-end evolution. And because Resonac’s particular strengths are in making proposals for back-end materials, it argues it can respond flexibly to what customers need next.

The company frames this as a leadership opportunity: as the No. 1 global supplier of back-end materials, it aims to drive the semiconductor materials industry through co-creation.

That “co-creation” isn’t just a slogan. Resonac has pushed into industry collaboration in a very concrete way. In 2023, it became the first Japanese manufacturer and materials company to participate in the Texas Institute for Electronics (TIE), a Texas-based non-profit consortium of public- and private-sector companies aiming to advance the roadmap of cutting-edge semiconductor technology by five years. Resonac was invited because its strengths were recognized.

And it didn’t stop there. Resonac unveiled a Silicon Valley-based consortium for semiconductor back-end process R&D called “US-JOINT,” a ten-partner group that included Azimuth, KLA, Kulicke & Soffa, Moses Lake Industries, MEC, ULVAC, NAMICS, TOK, TOWA, and Resonac. US-JOINT expanded the activities of Japan-based open consortiums led by Resonac.

Strategically, this approach does a few things at once. It gives Resonac early visibility into where packaging roadmaps are going. It increases stickiness by embedding Resonac’s engineers and materials into customer development loops. And it helps shift the company’s position from “supplier of inputs” to “partner in outcomes”—a subtle but powerful difference in an industry where qualification cycles are long and switching can be painful.

The business results began to reflect that positioning as the semiconductor cycle recovered. Sales rose in the Semiconductor and Electronic Materials segment and in Innovation Enabling Materials, driven by increased sales volume, and overall sales increased.

By the time Resonac presented its third-quarter 2025 results, the contrast inside the portfolio was clear: strong momentum in semiconductors alongside a weaker chemicals business. The presentation highlighted record quarterly core operating profit in the Semiconductor and Electronic Materials segment. The market response captured the same split—shares rose after hours to 6,040 yen, and the stock had returned 102.64% over the prior six months, trading near a 52-week high of 6,248 yen. The company reported Q3 2025 revenue of 344.21 billion yen.

Investors were rewarding the semiconductor exposure even while some legacy businesses lagged. Which tees up the next question: as the AI boom cools into something more like an industry—and less like a land grab—can Resonac keep its position at the choke points, and keep growing with the shift toward advanced packaging?

IX. Current Business and Strategic Priorities

Resonac now runs the company through four primary segments: Semiconductor and Electronic Materials, Mobility, Innovation Enabling Materials, and Chemicals. That’s the portfolio on the org chart. But the real story is where the prestige and the momentum are.

One signal came straight from the most demanding customer on Earth. Resonac received the “2025 TSMC Excellent Performance Award” for technological contributions in advanced packaging materials and for localizing high-purity gas production. In this business, awards aren’t participation trophies. TSMC’s supply chain runs on qualification, audit trails, and a brutal intolerance for inconsistency. Getting recognized there is a public confirmation that Resonac isn’t just present in advanced packaging—it’s contributing at a level that matters.

Underneath that customer-facing credibility is a second push: using AI to speed up the slowest part of a materials company—discovering and tuning the next material.

Resonac introduced neural network potential (NNP) technology, a simulation approach that combines first-principles calculation methods used in materials development with artificial intelligence. The goal is very specific: simulate and clarify the polishing mechanism in semiconductor processes using CMP slurry. Resonac says NNP can simulate chemical reactions more than 100,000 times faster while keeping the same level of accuracy as first-principles calculations. If that holds in practice, it changes the cadence of R&D. Instead of waiting on long, iterative lab cycles to understand why a slurry behaves the way it does, engineers can narrow the search space faster—and get to viable new formulations sooner.

In parallel, Resonac built an internal generative AI system called “Chat Resonac.” The point isn’t novelty; it’s integration. Chat Resonac can interactively draw on internal documents and accumulated data from both the former Showa Denko K.K. and the former Hitachi Chemical Co., Ltd. It’s designed to make knowledge that used to live in the heads of veteran employees accessible to everyone—so engineers can merge the two companies’ technical traditions and apply them to new development work, including semiconductor materials.

That’s a classic post-merger problem—two libraries, two vocabularies, two sets of “this is how we do it.” Resonac is effectively trying to use AI as the connective tissue, turning institutional memory into something searchable and shareable, and turning merger synergies into something you can actually execute.

Another strategic pillar sits outside Japan: the company’s joint venture with South Korea’s SK Materials. SK resonac, established with Resonac, has been growing into a leader in semiconductor etching gases by localizing high-level products that have historically been import-dependent and strengthening domestic technological independence. The JV has built a stable supply chain of high-purity etching gases based on Korea’s only synthesis process-based CH3F and HBr production facilities.

That matters because it places Resonac inside the Korean semiconductor gravitational field—where Samsung and SK Hynix sit at the center of the memory universe. And in the AI era, memory isn’t background; it’s the bottleneck. SK Hynix returned to profitability in the fourth quarter of 2023, largely driven by rising HBM sales for AI chips as generative AI demand surged. With HBM as a high-margin product, that growth had an outsized impact on revenue and profits. SK Hynix has been gearing up for mass production of a new HBM product with eight stacked DRAM layers and has started delivering samples of 12-layer variants to customers, while Samsung and Micron have also accelerated development of 12-layer HBM.

As the geopolitics of chips have gotten more tense, another theme has moved from “nice to have” to board-level priority: resilience. Resonac says its risk management system follows ISO31000 guidelines, with a Risk Management Committee chaired by the CEO overseeing cross-functional deliberations. The company also maintains significant inventories of key components to help keep commitments even when global disruptions hit. In a supply chain where a single missing input can stop an entire line, that kind of planning is less about efficiency and more about staying qualified.

And then there’s the long-term lens that increasingly shapes capital access and partnerships: sustainability. Resonac Holdings was selected as “SX Brand 2025” by METI and TSE. Being recognized by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry for sustainability transformation signals alignment with government priorities—something that can matter in subtle but real ways in Japan, from credibility with stakeholders to how a company is viewed when the next wave of industrial policy takes shape.

X. Competitive Analysis: Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's Seven Powers

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re trying to break into semiconductor materials, you’re not walking into a market so much as a fortress.

The industry is already concentrated and, in many categories, dominated by incumbents with decades of process know-how and long-term customer relationships. In photoresists, a small handful of producers control most global volume, and Japanese suppliers hold especially strong positions in multiple “must work every time” materials. The same pattern shows up in other inputs too: in high-purity hydrogen fluoride, Japanese firms have historically held an overwhelming share. These aren’t businesses where you win by being slightly cheaper. You win by being trusted.

That trust is built through qualification, and qualification is the real moat. Before a chipmaker will run a new material in production, it gets tested, re-tested, stress-tested, and audited—often over two to three years, at enormous cost. Even if a new entrant could create a technically comparable material, it still has to survive the long, expensive, low-revenue purgatory of getting into a high-volume process flow. And until that happens, the entrant is essentially burning cash while the incumbent keeps shipping.

The result is an ecosystem where entire upstream markets become quasi-locked. In silicon wafers, Shin-Etsu Chemical and SUMCO together control the vast majority of global supply. In photoresists, firms like JSR and Tokyo Ohka Kogyo hold a dominant share. Even in photomasks, Japanese companies account for a meaningful portion of the market. Taken together, it’s a picture of an industry where getting in is hard—and staying in requires constant reinvestment.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Resonac lives downstream of its own set of constraints: specialty raw materials and inputs, some tied to regions where geopolitics can turn procurement into a strategic problem overnight.

Parts of the supply chain are especially exposed. For example, the graphite electrode market is highly competitive and heavily supplied by China, which can create pricing pressure and volatility. Layer on top of that the reality that Resonac operates globally, and you get additional risk from shifting regulations, trade restrictions, and broader political instability.

In practice, this means supplier power isn’t crushing—but it’s real. Resonac has to manage around it, not pretend it doesn’t exist.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-LOW

On the other side of the table, Resonac sells to some of the toughest customers on the planet: TSMC, Samsung, SK Hynix, Intel. These companies are huge, technically sophisticated, and deeply cost- and yield-driven. In a normal industry, that would translate into relentless buyer power.

But semiconductor materials aren’t normal. Once a material is qualified into a production process, switching it is risky, slow, and expensive. It can introduce yield issues, trigger requalification, and cause disruptions that dwarf any savings from negotiating a lower unit price. That dynamic doesn’t remove customer leverage, but it tilts the balance back toward suppliers who are already embedded—especially when their materials sit in sensitive steps where failures are catastrophic.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

In many industries, the fear is that a new approach makes your product irrelevant. Here, the physics of chips are doing the opposite.

As front-end scaling runs into harder physical and economic limits, the industry’s attention has shifted toward back-end assembly technologies that improve functionality, integration, and density through packaging. That structural pivot doesn’t substitute away Resonac’s products; it increases the need for them.

More advanced packaging generally means more bonding materials, more thermal management, and more specialized films. As chipmakers lean into these techniques to keep pushing performance, demand rises for exactly the kinds of materials Resonac has built leadership in, including NCF and thermal interface materials.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

This is a concentrated industry with a small number of serious players. In electronics and semiconductor chemicals, a handful of companies control a large share of global market value, including JSR, Tokyo Ohka Kogyo, DuPont, Shin-Etsu, BASF, Merck, Fujifilm, Entegris (CMC Materials), Resonac, and Sumitomo Chemical.

That concentration cuts two ways. In the categories where Resonac leads—especially in back-end materials like NCF—its position reduces day-to-day rivalry because it’s not competing in a wide-open commodity brawl. But Resonac doesn’t only play in those defensible niches. In more commoditized segments of the portfolio, competition is intense, and scale players can squeeze margins.

So rivalry is moderate overall: high in some product lines, muted in the ones that matter most to the AI packaging story.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

-

Scale Economies: The Hitachi Chemical acquisition was a direct bet on scale. A larger base lets Resonac spread R&D across more revenue, run manufacturing assets at higher utilization, and negotiate procurement from a position of volume strength.

-

Network Effects: There aren’t classic network effects in chemicals, but Resonac is creating a softer version through ecosystem centrality. Consortium participation and leadership—JOINT, US-JOINT, and TIE—puts the company in the development loop as roadmaps get written.

-

Counter-Positioning: The acquisition was counter-positioning in action. Many legacy chemical companies can’t pivot hard into semiconductors without destabilizing their existing portfolios. Resonac made the disruptive move anyway, and built a company around it.

-

Switching Costs: This is the crown jewel. Semiconductor customers don’t swap materials casually. With multiple products that hold top share positions and a lineup spanning front-end to back-end, Resonac benefits not just from being qualified, but from being deeply integrated into how customers build and package chips.

-

Branding: In B2B materials, branding isn’t about consumer awareness; it’s about reputation. Reliability, consistency, and the ability to ship exactly the same thing, every time, at scale—those are the “brand” attributes that matter.

-

Cornered Resource: Decades of accumulated knowledge in back-end semiconductor materials. This is tacit expertise built through iteration with customers and manufacturing at unforgiving tolerances—difficult to copy, even with money.

-

Process Power: The ability to make these materials at the required purity levels and tolerances, consistently and at industrial scale, is a competitive advantage that compounds over time. It’s also the kind of advantage that only reveals itself under pressure—when volumes surge and quality requirements don’t relax.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors:

The most critical metrics to monitor:

-

Semiconductor and Electronic Materials Segment Operating Margin: The cleanest read on whether Resonac’s market positions are turning into real pricing power. Expansion suggests the strategy is working; compression suggests pressure from competition, mix, or costs.

-

Advanced Packaging Materials Revenue Growth: The direct proxy for exposure to the AI and HBM wave. If this grows meaningfully faster than the broader semiconductor market, it signals share gains, a better product mix, or both.

XI. Conclusion: The Materials Bet on the AI Age

Resonac is one of the purest “picks and shovels” stories hiding inside the AI boom. It isn’t trying to predict which model wins, which chip designer dominates, or which cloud platform captures the most workloads. The bet is simpler: advanced semiconductors are going to get built in enormous volumes, and the materials stack behind them will matter more, not less. Resonac sells some of the inputs you can’t manufacture without.

The bull case writes itself. AI semiconductors are projected to grow rapidly through the middle of the decade. And as AI chips demand more sophisticated packaging—more layers, tighter tolerances, and more heat to move—materials content per chip rises. That’s the key point: even if unit volumes grow, the complexity grows too, and that can expand Resonac’s revenue per device beyond simple shipment counts. The company’s strong position in NCF and other back-end materials creates real switching costs, the kind that protect pricing and keep competitors at arm’s length. Its consortium work and deep customer engagement help it see roadmaps early, and the Hitachi Chemical integration has largely moved from “risk” to “platform,” with synergies substantially realized while growth investment continues.

But the bear case is real, and it’s not subtle. Resonac is still carrying significant debt from the Hitachi Chemical deal, which makes it more exposed if interest rates rise further or the semiconductor cycle turns down. Parts of the portfolio remain cyclical—graphite electrodes and petrochemicals can throw off cash when conditions are good, and then become a drag when conditions aren’t. Chinese materials manufacturers continue to improve, and geopolitics can change customer behavior in ways that have nothing to do with performance. And while Resonac’s back-end dominance is formidable, it doesn’t automatically translate into the front-end process categories where other Japanese champions have long held the upper hand.

Then there are the operational risks that don’t show up in a market-share chart. In May 2025, Resonac experienced a ransomware-related security breach. Restoration efforts were ongoing, and the company was still assessing the potential impact on business performance. Cybersecurity isn’t a side issue anymore; for a materials supplier embedded in the semiconductor supply chain, it’s part of uptime.

That’s the thread running through Resonac’s whole modern story: fragility. Materials supply chains are unforgiving. A disruption at the wrong plant, at the wrong moment, can ripple through the entire semiconductor industry.

And no event captures the consequences of “small” failures better than the tryptophan tragedy of 1989. It proved that in specialized chemistry, tiny impurities and process decisions can trigger catastrophic outcomes—for customers, for society, and for the company itself. That memory helps explain Resonac’s institutional obsession with quality. In the AI era, where packaging gets denser and tolerances get tighter, that mindset may be one of the hardest advantages to replicate.

From iodine extraction in 1908 to the materials inside AI chips in 2025, Resonac’s arc shows how an industrial company can survive multiple technological epochs—if it keeps compounding capabilities, makes bold moves at the right moments, and has the discipline to prune what no longer fits. Nobuteru Mori’s “dauntlessness and indomitableness” has turned out to be less a motto than a requirement for staying alive this long.

Whether Resonac becomes a generational winner in AI semiconductors, or simply rides a powerful but cyclical wave, comes down to execution: winning and keeping customer qualifications, maintaining quality as specifications tighten, and investing early enough in the next generation of materials to stay ahead of the pack. The pieces are in place. The position is strong. The open question is whether Resonac can hold that edge as the boom matures into an industry.

For anyone watching the AI revolution, Resonac is the reminder hiding in plain sight: the future doesn’t run on headlines. It runs on supply chains—and on the specialized materials companies that quietly determine what the world can actually build.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music