Nexon: The Company That Invented Free-to-Play Gaming

I. Introduction: The Accidental Architects of a $200 Billion Industry

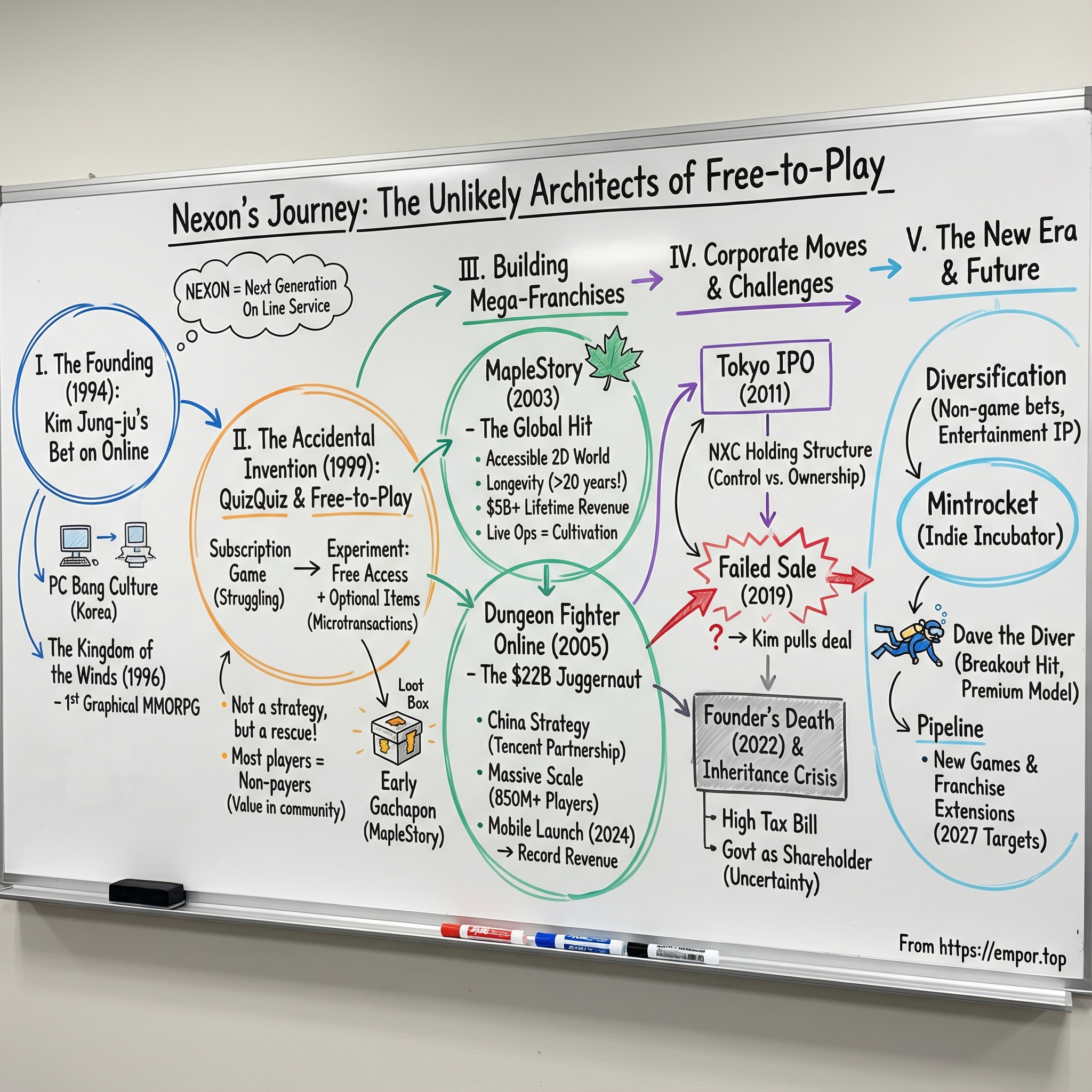

Picture this: it’s 2016, and Nexon drops a number that doesn’t sound real. Dungeon Fighter Online—a free-to-play online game launched in 2005, and largely unknown to Western audiences—had generated $8.7 billion in a little over a decade. More than the combined box office haul of Star Wars, the biggest film franchise at the time. Not Marvel. Not Harry Potter. A mostly invisible-to-the-West online game had quietly become one of the highest-grossing entertainment properties on the planet.

Fast-forward to today and the “quiet giant” label still fits. In 2024, Nexon reported record annual revenue of ¥446.2 billion, about $3 billion. It generated more than ¥100 billion in operating cash for the seventh year in a row and ended the year with over ¥600 billion in cash—roughly $4 billion sitting on the balance sheet, ready for whatever comes next.

But the numbers aren’t the real hook. The hook is the mystery behind them.

How did a small Korean startup—founded in a country just beginning its internet boom—accidentally invent the business model that would come to dominate gaming? And why is it that the rest of the world copied free-to-play, but so often missed the part Nexon seems to do better than anyone: keeping games alive, and lucrative, for decades?

Because Nexon isn’t a one-hit wonder. It now runs more than 80 live games across over 190 countries. And its flagship franchises—MapleStory, Dungeon Fighter Online, and FC Online—have been throwing off revenue for twenty years, defying the idea that games are disposable hits with short shelf lives.

This is the story of Kim Jung-ju: a computer science grad who helped create the first graphical MMO, stumbled into microtransactions while trying to rescue a struggling game, and built a company that would eventually outgrow him—then outlive him under tragic circumstances. Along the way: Korea’s PC Bang culture, the China goldmine, a $9 billion sale that almost happened, and an inheritance-tax crisis that turned the South Korean government into an unwilling shareholder in one of the country’s most valuable tech empires.

We’re going from the internet cafes of 1990s Seoul to the Tokyo Stock Exchange, from early online worlds to modern gaming’s most lucrative playbook. Let’s dive in.

II. The Founding: Kim Jung-ju and the Birth of Online Gaming

The Visionary Graduate

In late 1994, in Seoul’s Yeoksam-dong district, a 26-year-old computer science grad set up shop in a small rented space and placed a bet that, at the time, sounded almost absurd: games would move online.

Kim Jung-ju was born in Seoul on February 22, 1968. He earned a B.S. in Computer Science and Engineering from Seoul National University, then an M.S. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from KAIST—where, years later, he would return as an adjunct professor in 2011.

The early funding story is as personal as it is telling. Kim’s family valued education and conventional career paths, but his father backed him anyway. A lawyer who had served as a judge at the Seoul District Court before opening a private practice, he reportedly loaned Kim 60 million won to get started. Kim used it to secure a studio in Yeoksam-dong that doubled as Nexon’s first office.

That mattered because the industry Kim was walking into barely existed. In 1994, gaming meant cartridges and discs. Console gaming was defined by Nintendo and Sony. PC games were boxed products you bought at retail and played alone. The idea that thousands of people could share the same game world over the internet wasn’t a business plan so much as science fiction.

But on December 26, 1994, Kim founded Nexon in Seoul anyway—built around a conviction that online play wasn’t a feature, it was the future. Even the name was a flag planted in that future: “Nexon,” short for “NEXT Generation on Line Service.”

The World's First Graphical MMORPG

Two years later, Nexon shipped the proof.

In 1996, the company released Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds, widely acknowledged as the world’s first graphical massively multiplayer online role-playing game. It wasn’t just “an MMO before MMOs were cool.” It introduced the building blocks of what we now take for granted: real player interaction, cooperative quests, and in-game item trading inside a persistent online world.

Yes, multiplayer games existed before that—especially MUDs, the text-based online worlds where you read descriptions and typed commands. But Nexon made it visual. Players could see their character, see other players, and exist together in real time. That leap—from text to a living graphical world—turned online gaming from a niche hobby into something that could plausibly become mass-market.

And here’s the most Nexon part of the story: the company still services The Kingdom of the Winds today. Nearly 30 years of continuous operation. That longevity wasn’t an accident—it was an early signal of how Nexon would think differently from Western publishers that chased sequels and yearly releases. Nexon learned to treat games less like products and more like places.

The Korean Internet Cafe Culture

Nexon’s timing also happened to collide with a uniquely Korean phenomenon: the PC bang.

A PC bang is an internet cafe—part LAN center, part social hangout—where you pay by the hour to use a capable gaming PC and a fast connection. And in the late ’90s, they spread across South Korea at exactly the moment when the country was becoming the world’s online-gaming laboratory.

After the 1997 Asian financial crisis, life in South Korea shifted hard. Government programs were paused, unemployment rose, and many laid-off workers turned to entrepreneurship. PC bangs became one of the breakout businesses: low barrier, high demand, and perfectly aligned with a population eager for affordable entertainment and connection. The numbers tell the story of that explosion—an estimated 100 PC bangs in 1997, and more than 13,000 by 1999.

Even as home broadband penetration became among the highest in the world, PC bangs stayed popular because they offered something a home PC didn’t: a shared room full of friends. They also solved a practical problem. High-end computers were expensive. A PC bang gave anyone access to great hardware for a small hourly fee.

For online games, this was jet fuel. These cafes weren’t just distribution—they were retention. They turned gaming into a routine, a social ritual, something you did with your group after school or after work.

Game companies leaned into that culture with PC bang-specific incentives. Nexon did too: games like KartRider and BnB rewarded players with bonus Lucci—their virtual currencies—simply for logging in from a PC bang. It was a small mechanic with a big effect: it encouraged the behavior that made online worlds thrive.

As Nexon followed The Kingdom of the Winds with more titles—Dark Ages: Online Roleplaying, Elemental Saga, QuizQuiz, KartRider, Elancia, Shattered Galaxy—the company was accumulating something more valuable than hits. It was building operational muscle: how to run persistent online worlds, how to manage communities, and how to keep players coming back day after day.

And that’s the real foundation Nexon poured in the ’90s. Kim Jung-ju didn’t just start a game company. He bet on an inflection point—broadband plus social gaming—and built a business designed to live online. The decades-long lifespans of Nexon’s biggest franchises weren’t a lucky outcome. They were the strategy, baked in from the beginning.

III. The Accidental Invention: How Free-to-Play Was Born

The QuizQuiz Experiment

Free-to-play didn’t start as a grand monetization strategy. It started as triage.

Nexon had a subscription game that wasn’t getting enough players. The kind of title companies quietly shut down, write off, and move on from. Instead, the team tried something that sounded reckless for the time: make the game free, and sell a few optional items inside it. Not because they’d modeled out the economics, but because they were trying to keep the game alive.

That experiment was QuizQuiz, released in 1999. It was a massively multiplayer quiz game with an anime-inspired look—hardly the sort of thing you’d expect to reshape an entire industry. But QuizQuiz became one of the earliest examples of what we now call the microtransaction model: free access, optional purchases.

Nexon would later point to QuizQuiz—now known as QPlay—as the moment it first introduced microtransactions at scale. And from there, the precedent spread: a new way to build and run online worlds, where the front door is open to everyone.

The Philosophy Behind the Model

The more important part wasn’t the pricing. It was the intent.

Former Nexon CEO Owen Mahoney explained it at GamesBeat 2015: “The point in the story is that it didn’t start out as a monetization strategy or a business strategy. It started out as an idea on how to help your customers, or your gamers, to have more fun in the game.” And then Nexon noticed something that would become the foundation of modern gaming economics: most players didn’t pay. Mahoney said the team quickly realized that roughly 90 percent of players didn’t buy anything—yet they still had a great time.

That’s the inversion. In the old model, everyone pays upfront, and the market is limited to whoever can justify the price. Nexon flipped it: let everyone in, then offer optional ways for a subset of players to personalize, accelerate, or enhance their experience.

Nexon’s view of free-to-play also diverged from what many Western players later came to hate as “pay-to-win.” The goal, at least in Nexon’s framing, wasn’t to strong-arm people into paying to remain competitive. It was to keep the game fun and fair, and let spending be additive rather than required.

Mahoney was blunt about why that matters: if developers treat free-to-play as a way to “pull money out of people’s pocket,” players feel it. “If you fool people once, they don’t come back, and it’s death to your game,” he said.

He also pushed back on the industry obsession with “whales,” the tiny percentage of players who spend enormous amounts. In a GamesBeat Summit 2020 interview, Mahoney argued that whale-chasing isn’t just ethically messy—it’s operationally dangerous. Nexon, he said, looks for “reasonable to a low amount of spend” across a broad base of players. Because if your business depends on a handful of mega-spenders, it’s fragile. “If that whale leaves,” he said, “then you’re really in a tough position.”

The Birth of Loot Boxes

Microtransactions didn’t stay limited to straightforward purchases. In the MapleStory ecosystem around 2004, Japanese servers introduced “Gachapon tickets”—paid pulls for randomized items, modeled after Japan’s capsule toy machines. It’s one of the early, recognizable ancestors of what the industry would later call loot boxes.

And by the mid-2000s, the revenue impact was impossible to ignore. Nexon was generating the bulk of its business from virtual item sales—reported as 85% of its roughly $230 million in revenue in 2005.

That’s the moment you can feel the ground shift. These weren’t boxed games. They weren’t subscriptions. They were living worlds, free to enter, funded by digital goods.

Nexon’s internal logic was simple: build online experiences meant to last for years, not weeks. Mahoney later described it as a rejection of the “pump-and-dump” mentality—games designed to spike, extract, and fade. Nexon’s ambition was multi-year, sustained growth, built on respecting the time players invest and the communities they form.

The real breakthrough—one that would echo far beyond games—was recognizing that non-paying players still create enormous value. They populate the world. They keep matchmaking alive. They make the game feel like a place worth being. Free-to-play wasn’t just a pricing trick. It was a system design choice that turned player density and long-term engagement into the core asset.

And once Nexon proved it could work, the rest of the industry spent the next two decades racing to copy it.

IV. MapleStory: Building the First Mega-Franchise

The Wizet Acquisition

By the early 2000s, Nexon had done the hard, weird thing: it proved you could give a game away and still build a business. What it didn’t have yet was the kind of breakout hit that could take that model out of Korea and make it feel inevitable everywhere.

That hit was MapleStory.

In April 2001, a Seoul game studio called Wizet was founded, led by Seung-chan Lee—a lead developer who’d worked on Nexon’s QuizQuiz. That detail matters. Lee wasn’t coming from the boxed-software world. He came from the earliest days of Nexon’s free-to-play experiments, where “game design” and “business model” weren’t separate conversations.

Wizet released MapleStory in Korea in April 2003, and it caught fast. Shortly after launch, it hit 100,000 concurrent users and 2 million registered users. Later that year, it launched in Japan with similar success. In 2004, Nexon acquired Wizet—and from that point on, MapleStory wasn’t just a successful game Nexon published. It became a franchise Nexon would actively build, operate, and evolve for decades.

The Global Expansion

MapleStory worked because it didn’t ask much from you upfront—financially or technically. It was a 2D side-scrolling online world with a bright, approachable style, and it ran well on modest hardware. For a huge population of players, that mattered. It was an MMO you could fall into without the intimidation factor of the big 3D worlds that defined the genre.

Then came the real test: North America in 2005.

This wasn’t just a new regional launch. It was one of the first times the modern free-to-play model—at meaningful scale—was being brought to Western audiences. And it translated. Nexon America later said MapleStory reached 92 million users worldwide, with six million in North America. By 2020, Nexon reported over 180 million registered users worldwide.

The money followed the audience. Through 2011, MapleStory grossed $1.8 billion. From 2013 to 2017, it grossed another $1.181 billion. By 2020, it had passed $3 billion in lifetime revenue worldwide. And the story didn’t stop there: across its history, MapleStory has since surpassed 250 million registered users globally and generated more than $5.0 billion in lifetime revenue.

MapleStory's Lasting Legacy

MapleStory’s true achievement wasn’t just that it became big. It was that it stayed big.

The game launched in 2003 and is still actively developed today—more than two decades later. And it hasn’t merely coasted on nostalgia. In Q2 2025, Korean MapleStory recorded 91% revenue growth, Global MapleStory grew 36% year-over-year, and the franchise as a whole grew 60% year-over-year. Korean MapleStory even hit record quarterly revenue in its 22nd year.

This is what Nexon means when it treats games like places. MapleStory wasn’t shipped and “supported.” It was cultivated—updated, tuned, expanded, and kept socially alive, year after year. The company’s live-operations muscle, built in the ’90s, finally had the perfect vehicle.

That durability also shows up in Nexon’s financial shape today. In 2024, Nexon’s three largest franchises—MapleStory, Dungeon&Fighter, and FC—grew in aggregate by 10% year-over-year and accounted for 74% of Nexon’s 2024 revenue, up from 71% in 2023.

It’s both impressive and revealing. On one hand, it’s extraordinary staying power—games old enough to drink still driving the company. On the other, it hints at a strategic tension: Nexon has been very good at keeping mega-franchises alive, and less consistent at creating new ones that reach the same scale.

But as a case study, MapleStory is the clearest proof of Nexon’s core thesis: if you keep investing in a single world—treating players like a community, not a conversion funnel—one game can generate returns for decades, without needing an annual sequel treadmill to stay relevant.

V. Dungeon Fighter Online: The $22 Billion Juggernaut

The Neople Subsidiary and China Strategy

If MapleStory proved free-to-play could travel, Dungeon Fighter Online proved it could print money on a completely different scale.

Dungeon Fighter Online—often shortened to DnF—is now one of the most-played and highest-grossing games ever made. As of June 2023, it had surpassed 850 million players worldwide and crossed $22 billion in lifetime revenue, putting it in the rare category of entertainment properties that compete with the biggest franchises in film and television.

Nexon owns this juggernaut through Neople, its wholly owned subsidiary and the developer behind Dungeon & Fighter. And while the game has fans across Asia, the story only really makes sense once you say the quiet part out loud: this is, above all, a China story.

Unlike MapleStory—which found meaningful audiences in North America—Dungeon Fighter’s truly astronomical scale is driven primarily by the Chinese market. Nexon’s partnership with Tencent to publish in China turned the game into something close to a perpetual revenue engine, in the single most lucrative market in gaming, and one of the hardest for foreign companies to access without the right local ally.

Becoming the Highest-Grossing Game Ever

The revenue arc is almost surreal.

In 2018, Dungeon Fighter Online was the second highest-grossing digital game in the world, bringing in about $1.5 billion. In 2019, it did it again at roughly $1.6 billion, pushing lifetime gross revenue to $13.4 billion as of 2019. By May 2020, it had passed $15 billion—already more than the box office grosses of major film series like Star Wars, Harry Potter, and the Avengers.

By December 2021, the original PC version alone had grossed over $18 billion and exceeded 850 million registered users worldwide. And by 2024, lifetime revenue was commonly cited at around $22 billion.

If you want a gut-check comparison: the Marvel Cinematic Universe has done roughly $30 billion at the global box office over more than a decade and dozens of films. Dungeon Fighter Online, a single free-to-play game, generated revenue in the same universe.

The 2024 Mobile Launch: A Case Study in IP Longevity

Then, in May 2024, Nexon and Tencent finally brought the franchise’s biggest test to market: Dungeon & Fighter Mobile in China, after years of delays. What followed was a reminder of Nexon’s core superpower—keeping worlds alive long enough that a “new launch” can happen nearly twenty years later and still feel like an event.

Niko Partners estimated the game made over $140 million in its first week across iOS and local Android stores. It went on to rank as the top-grossing iOS game in China for four straight weeks, with first-month revenue widely reported as exceeding $500 million once you include third-party Android stores.

By the end of 2024, the Chinese version of DnF Mobile had generated nearly $2.5 billion in gross revenue since launch, according to the Niko News newsletter. The broader Dungeon&Fighter franchise grew 53% in 2024, fueled by that mobile release expanding the player base.

The takeaway isn’t just that a beloved PC game got a mobile spin-off. It’s what the launch proves: enduring IP can move platforms even after nearly two decades, China remains the deepest pool of gaming revenue on earth, and Tencent is a distribution partner with real, hard-to-replicate leverage inside that market.

It also creates a very specific profile for Nexon. Dungeon Fighter Online is both a crown jewel and a concentration risk: in 2024, Neople hit record annual revenue—roughly $951 million—thanks to the China mobile launch. But that same dependence means any regulatory, political, or competitive shock in China can ripple straight through Nexon’s financials.

VI. The Tokyo IPO & Corporate Restructuring

Moving Headquarters to Japan

In 2005, Nexon made a move that still surprises people: this Korean-born company shifted its headquarters to Tokyo.

The rationale was practical, not sentimental. Japan offered tax advantages, deeper and more liquid capital markets, and a front-row seat to one of the world’s biggest gaming economies. For a business that was already thinking globally—and increasingly monetizing through always-on online games—Tokyo was a better platform than Seoul for what came next.

But the move didn’t mean Nexon stopped being, at its core, Kim Jung-ju’s Korean creation. The company’s largest shareholder remained NXC, an investment and holding company headquartered in Jeju Province, South Korea. From the outside, the setup looked a bit like corporate origami: a Tokyo-based operating company ultimately controlled by a Korean holding company. It added complexity, yes—but it also gave Nexon flexibility as it expanded across markets and managed ownership.

The Historic 2011 IPO

On December 14, 2011, Nexon went public on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in what became Japan’s largest IPO of the year—and the second largest tech IPO globally in 2011.

The offering raised 90 billion yen, about $1.15 billion at the time, by issuing 70.1 million new shares priced at 1,300 yen each. At that price, Nexon’s market value came out to roughly ¥550 billion, based on about 425 million shares outstanding.

The timing couldn’t have fit the story better. The industry was swinging hard toward digital distribution and free-to-play—exactly the territory Nexon had been mapping for more than a decade. As TechCrunch noted, it was the biggest IPO in Japan that year, and it gave global investors a rare chance to buy into a company behind massive online hits like MapleStory, Mabinogi, and Vindictus.

Over time, Nexon became a mainstay in Japan’s public markets, joining major indices including JPX400, Nikkei Stock Index 300, and Nikkei 225.

The NXC Holding Structure

Underneath the public listing was the control structure that mattered even more.

In 2009, Kim consolidated his and his family’s majority ownership by creating NXC Corporation, and he served as NXC’s CEO until July 2021. NXC held the controlling stake in Tokyo-listed Nexon, which meant the center of gravity wasn’t the public company’s shareholder base. It was the Kim family’s ownership of the holding company.

In the early days, this looked like a straightforward founder-control setup: go public to raise capital and build credibility, but keep the steering wheel. And it worked—until it didn’t.

Because as Nexon grew into one of the world’s biggest gaming businesses, this structure carried a blunt implication: buying Nexon shares on the Tokyo exchange didn’t buy you control of Nexon. It bought you exposure, dividends, and whatever decisions the controlling shareholder chose to make. That reality would become central later—when the company flirted with a blockbuster sale, and when succession stopped being a theoretical issue and became an urgent one.

VII. The 2019 Failed Sale: A Pivotal Moment

Kim Jung-ju's Surprising Decision

In early 2019, a rumor hit the industry that sounded impossible: Kim Jung-ju wasn’t just considering a sale of some assets. He was exploring selling control of the entire empire.

What was on the table wasn’t the Tokyo-listed Nexon stock directly, but the holding company above it: NXC Corp. Reports estimated the stake for sale at essentially the whole company—about 98.64%—valued at over 10 trillion won, roughly $9 billion. If it had gone through, it would have been one of the biggest M&A deals South Korea had ever seen.

People close to the process pointed to two pressures converging at once. First, Kim had grown frustrated with heavy regulation around the gaming business. Second, he’d spent years under a harsh public spotlight because of a legal scandal.

That scandal started in 2016, when Kim was charged over suspicious stock transactions and bribery connected to South Korean prosecutor Jin Kyung-joon. Prosecutors alleged Kim had given Jin more than 920 million won and, separately, that Kim had provided 420 million won for Jin to buy unlisted Nexon Korea stock back in 2005. Kim apologized publicly and resigned from Nexon’s board in July 2016. Although he was ultimately acquitted, he still endured years of investigations into allegations including bribery, suspicious trading, and tax evasion—and the grind of that scrutiny appeared to leave a mark.

The Abrupt Withdrawal

Once the process became public, the buyer speculation went wild. Names like Tencent and The Walt Disney Company floated to the top, alongside the usual private equity giants.

Eventually, five bidders were confirmed: Kakao, Netmarble, MBK Partners, KKR, and Bain Capital. Binding bids came in from the private equity firms and from Kakao and Netmarble. Disney, despite the rumors, didn’t participate. Bain and Kakao were later dropped after submitting lower bids.

That left three finalists: KKR, MBK Partners, and Netmarble. Multiple reports said it had become a close race between MBK and Netmarble—but the numbers weren’t close to what Kim wanted. The bids came in well below the asking price, reported at roughly $8.5 billion, or around 10 trillion to 10.5 trillion won.

Netmarble pushed its offer up to $8 billion at the last moment. And then, just as suddenly as the sale had appeared, it stopped. Kim pulled the process and offered no clear public explanation. At the time, Nexon’s shares traded around 1,617 yen—well below where they would trade later—which only made the reversal feel more puzzling to outside observers. Bidders and analysts were left guessing: why start a deal of this magnitude, only to walk away at the finish line?

Kim's Vision for the Future

In hindsight, the failed sale exposed what Kim actually wanted—and what he didn’t.

Reports suggested he had hoped for a strategic buyer: someone who could operate live games, build new ones, and expand the company’s reach globally. He expected global giants like Disney, Amazon, and Tencent to show up. None did. And when the remaining field narrowed to financial buyers and domestic rivals, the fit may have felt wrong, even if the money was enormous.

After scrapping the sale, Kim turned back to the question he couldn’t escape: how does Nexon become more than its cash cows? MapleStory and Dungeon Fighter were extraordinary, but even he seemed to accept that a company can’t live forever on just a few immortal hits.

So instead of selling, he leaned into building—especially beyond games and toward broader entertainment, with a noticeable pull toward Hollywood. In July 2021, Nexon announced Nexon Film and Television, based in Los Angeles. Then, in January 2022, the Russo brothers’ production company AGBO sold a $400 million minority stake to Nexon, valuing AGBO at $1.1 billion and giving Nexon a 38% stake.

The $9 billion almost-deal became one of gaming’s great “what if” moments. Kim’s family kept control. Nexon kept compounding. And then, not long after, the story took a far darker turn.

VIII. The Founder's Death & Inheritance Crisis

The Shocking News

On February 28, 2022, Kim Jung-ju—the founder of Nexon, and one of the people most responsible for turning online games into a global business—died while traveling in Hawaii. He was 54. Nexon’s holding company, NXC, said he had been receiving treatment for depression, and that his condition seemed to have worsened in recent months.

By then, Kim wasn’t just an influential founder. He was one of South Korea’s wealthiest people, with an estimated net worth of $10.7 billion—ranking him third in the country at the time.

The reaction across the industry made clear how big a presence he’d been.

Nexon CEO Owen Mahoney called him “our friend and mentor Jay Kim,” and said, “It is difficult to express the tragedy of losing… a man who had an immeasurably positive impact on the world,” adding that Kim pushed people to ignore skeptics and trust their creative instincts.

Kim Taek-jin, CEO of rival gaming giant NCSoft, wrote a raw farewell on Facebook: “I feel the greatest pain I have not felt before in my life. My friend who walked on the path of life with me. I loved you. Rest in peace, please.”

But grief wasn’t the only thing that followed. Kim’s death triggered a chain reaction that would pull the South Korean government directly into Nexon’s ownership structure.

The Inheritance Tax Dilemma

Kim’s passing set off one of the most complicated inheritance situations in modern Korean business.

His family inherited an estate estimated at around 10 trillion won. South Korea’s inheritance taxes are among the highest in the world, and for the largest fortunes they can reach as high as 60 percent. That meant the family faced a bill of roughly 6 trillion won—about $4.5 billion.

The mechanics behind that number are brutal. Korea’s top inheritance rate is 50 percent, already far above the OECD average. And for controlling shareholders of large companies, there’s an additional 20 percent surcharge when ownership stakes are passed down—pushing the effective top rate to 60 percent.

The family’s solution was as dramatic as the problem. They chose to pay a large portion of the tax—4.7 trillion won—not in cash, but by handing over nearly 30 percent of NXC shares to the government. The transfer took place in May, and it became the largest inheritance tax ever paid in the form of corporate stock in South Korea.

That’s how the government ended up holding a massive chunk of the private holding company that controls Nexon. But owning the shares and turning them into money were two very different things.

The Failed Government Auctions

The government, through the Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO), tried to auction off the NXC stake it had received. Twice, nobody showed up.

The open bid to sell the Finance Ministry’s 29.3 percent stake—about 852,000 shares—ended with zero offers. An earlier attempt in mid-December failed the same way.

The reasons get to the heart of why Nexon’s holding-company structure matters so much.

First, NXC is unlisted, so there’s no clean market price. That makes it hard to agree on valuation, and the reserve prices were widely viewed as too high.

Second—and more importantly—even buying the government’s entire 29.3 percent wouldn’t give an investor control. Kim’s surviving family members still held a combined 69.34 percent stake. His widow, Yoo Jung-hyun, became an internal executive director and held the single largest stake at 34 percent. In other words: you could pay billions, and still be a passenger.

There was also a particularly awkward detail embedded in the auction structure: the buyer would effectively be paying for “management rights” that can’t actually be exercised, because the stake doesn’t come with control. Reports put that extra implied cost at about 800 billion won—another reason potential buyers balked.

And the stakes aren’t just academic. The government has treated the sale as a real budget item, factoring in an additional 3.7 trillion won in projected 2025 revenue on the assumption that the stake can be sold within the year.

For investors, the whole episode is a case study in concentrated founder control colliding with national tax policy. The Kim family still controls Nexon through NXC. But the government sitting there as a major minority shareholder adds uncertainty—and forces any would-be buyer to answer a simple question: why pay a premium for a large stake that can’t steer the company?

IX. The Diversification Play: From Games to Empire

Beyond Gaming

For someone who built one of the world’s most profitable game companies, Kim Jung-ju didn’t invest like a typical games founder. Through NXC, his holding company, he went hunting across categories—often for businesses that looked less like “synergies” and more like obsessions, curiosities, and long-term bets.

The most personal was Bricklink. Kim was an avid Lego fan, and in 2013 he bought the online marketplace where Lego enthusiasts buy and sell sets and parts. Six years later, in 2019, NXC sold Bricklink to The Lego Group itself. It was a very Kim move: buy something he genuinely loved, build around it, then hand it off to the natural strategic owner.

Then there was Stokke, the premium children’s furniture company NXC acquired in 2014, and later expanded with the 2018 purchase of JetKids. And in a completely different direction, NXC bought into crypto early, acquiring Korbit in 2017 and Bitstamp in 2018—major exchanges in South Korea and Europe, respectively. Whatever you think of crypto, those weren’t casual experiments. They put NXC in the middle of a major new financial category before it became a mainstream dinner-table topic.

The Entertainment Vision

Kim’s boldest diversification play aimed straight at Hollywood.

In July 2021, Nexon announced Nexon Film and Television, based in Los Angeles. The idea was simple in concept and brutally hard in practice: take the durable, global IP Nexon had built in games and extend it into film and TV.

That ambition showed up in the scale of the bets. In January 2022, the Russo brothers’ production company AGBO sold a $400 million minority stake to Nexon, valuing AGBO at $1.1 billion and giving Nexon a 38% stake. This wasn’t a licensing deal or a toe in the water. It was Nexon buying a real seat at the table with the people behind Avengers: Endgame—and a shot at turning game worlds into screen worlds.

Strategic Investments

Nexon also tried a third path: not buying whole companies, but building a portfolio of relationships with established entertainment and gaming players.

On June 2, 2020, the company announced plans to invest $1.5 billion in listed entertainment companies. By March 2021, it had deployed $874 million into Hasbro, Bandai Namco Holdings, Konami, and Sega Sammy Holdings, while saying it had no interest in outright acquisitions or activist positions. Read one way, this is straightforward diversification. Read another, it’s a way to get closer to IP-rich companies and signal that Nexon sees itself as part of a broader entertainment ecosystem, not just a Korean-born online game operator.

At the same time, Nexon did pursue a more direct “build in the West” strategy. In 2019, the company announced plans to acquire Embark Studios, founded by Patrick Söderlund, the former Chief Design Officer of Electronic Arts. If the public-market investments were about adjacency and optionality, Embark was about capability: recruiting proven AAA talent to create new games with global appeal.

For investors, all of this raises the most fundamental question in any cash-rich business: what’s the best use of the cash? Nexon throws off enormous free cash flow from its live games—over $700 million annually. Should that money go into more internal game development, bigger swings on new studios, minority stakes, film production, crypto exchanges, or returning capital to shareholders?

Nexon’s own actions suggest it feels that tension too. The company’s authorization of a one-year ¥100 billion share buyback was a clear message: even with big ambitions, it knows shareholders are watching whether diversification can beat the simple alternative—buying back stock and doubling down on the core.

X. The New Era: Mintrocket, Dave the Diver & Global Expansion

Creating the "Indie Incubator"

In May 2022, Nexon announced Mintrocket: a sub-brand and internal label built around a deceptively simple mandate—make games “focusing on the essence of fun.”

On paper, that sounded almost rebellious coming from the company famous for giant, long-running online worlds and relentlessly tuned live operations. Mintrocket’s premise was the opposite: smaller teams, tighter scopes, faster learning cycles, and creative decisions driven by what feels good to play, not what best fits a monetization spreadsheet.

The twist, of course, is that it wasn’t a scrappy garage studio. It was a scrappy garage studio with the backing of a cash-rich global giant—creative freedom with a safety net.

Dave the Diver: A Breakout Success

Then Mintrocket shipped the proof-of-concept: Dave the Diver, a game that looks modest at first glance and then quietly steals your life.

By day, you dive for fish and ingredients. By night, you run a sushi restaurant. The loop is simple, the tone is charming, and the pacing is addictively well tuned—exactly the kind of “just one more run” magic that’s hard to manufacture on demand.

The market reaction was immediate. Two days after release, Dave the Diver was the fifth best-selling product on Steam. It passed one million copies sold within ten days, and reached three million by January 2024. By November 2024, Mintrocket said it had surpassed five million copies sold across all platforms.

Success also created a strange identity crisis—one that says a lot about how blurred the lines in games have become. Even though Mintrocket was wholly owned by Nexon, many people described Dave the Diver as an “indie game,” and it was nominated in “Best Independent Game” categories at both The Game Awards 2023 and the Golden Joystick Awards 2023. Those nominations sparked criticism that a Nexon-backed title could crowd out smaller, truly independent teams—and kicked off the perennial argument: is “indie” about budget, ownership, team size, or spirit?

Inside Nexon, the takeaway was simpler. Dave the Diver proved the company could create a hit outside the MMO playbook—and could do it with a completely different business model. This was a premium game: buy once, no microtransactions, no live-service treadmill. Just a great game that people wanted to own.

And with that validation in hand, Nexon doubled down. In September 2024, it made Mintrocket a wholly owned subsidiary—formalizing the experiment into a longer-term vehicle for new bets.

The Pipeline and Future Growth

Nexon now talks about the next phase with a level of structure that matches its scale. Looking ahead, it has seven new games planned for launch by 2027, each positioned as having the potential to generate more than ¥10 billion in annual revenue. The pipeline includes ARC Raiders; NAKWON: LAST PARADISE; Vindictus: Defying Fate; The Kingdom of the Winds 2; Project DX; and two new extensions of the Dungeon&Fighter universe: Project OVERKILL and Dungeon&Fighter: ARAD.

At a September 2024 briefing, Nexon also laid out its financial targets: a 15% revenue CAGR and a 17% operating income CAGR from 2023 to 2027, with annual revenue reaching ¥750 billion and annual operating income reaching ¥250 billion by 2027.

It’s a big swing—close to doubling both revenue and operating income in four years. And it only happens if Nexon can do two hard things at once: keep its old worlds compounding, and successfully launch new ones into a market that is more crowded, more expensive, and more hit-driven than ever.

“Following record-breaking revenue in 2024, Nexon is committed to strengthening established franchises like Dungeon&Fighter for sustained growth and profitability,” said Junghun Lee, President and CEO of Nexon. “A disciplined increase in our own creative force, plus a new co-development agreement with Tencent, will provide the resources needed to drive growth.”

That’s the new-era Nexon in one snapshot: still built on the long, steady cash flows of enduring franchises—but now trying to prove it can repeatedly create the next MapleStory, the next Dungeon Fighter, and yes, maybe even the next Dave the Diver.

XI. Investment Analysis: Bull Case, Bear Case, and What Matters

The Bull Case

If you’re bullish on Nexon, the case starts with a simple observation: this company isn’t guessing. It’s already done the thing most game companies only talk about.

Proven Franchise Longevity. Nexon runs worlds that have been generating meaningful revenue for decades. MapleStory and Dungeon Fighter aren’t just “successful games.” They’re long-running ecosystems—kept fresh through live operations, content pacing, and community management in a way Western publishers have often struggled to replicate at scale. That track record matters because in gaming, durability is the rarest commodity.

China Optionality. Dungeon Fighter Mobile’s launch in China was a reminder that Nexon’s biggest IP can still move platforms—even after nearly twenty years—and remain a massive commercial event. With Tencent as its partner, Nexon has a distribution path into the world’s most lucrative gaming market that’s difficult to match. Any future mobile adaptations or IP extensions come with China-sized upside.

Balance Sheet Strength. Nexon has piled up a war chest—over ¥600 billion in cash, plus steady operating cash generation. That gives it unusually wide strategic freedom: it can fund new development, make acquisitions, and return capital to shareholders without choosing just one. In a hits-driven industry, financial resilience is an edge.

Counter-Positioning. Through the lens of Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, Nexon benefits from being built around a model many competitors can’t easily adopt without breaking themselves. Nexon’s business is optimized for long-lived live-service operations. Traditional Western publishers have historically relied on big launches and annualized release cadences. Shifting to Nexon’s approach would mean cannibalizing existing practices, org structures, and P&L expectations—exactly the kind of internal resistance that makes counter-positioning powerful.

Process Power. Nexon’s real moat may not be any single game. It’s the accumulated muscle memory of running online worlds for 20+ years—reading player behavior, tuning economies, shipping updates at the right tempo, and monetizing without destroying trust. That kind of know-how is hard to copy quickly, even with money.

The Bear Case

The bear case is also straightforward: Nexon is excellent at keeping a few worlds alive. The question is whether that’s enough.

Geographic Concentration. Dungeon Fighter Online is heavily exposed to China. If China tightens regulation again, if approvals slow, if competition shifts the market, or if the Tencent relationship weakens, the impact could be immediate and material. When one region drives that much of the upside, it also drives a lot of the risk.

Franchise Dependence. Nexon’s biggest franchises are also its oldest. Dungeon Fighter and MapleStory have carried the company for years, and the company hasn’t consistently created new hits at the same scale. Dave the Diver was a real success, but it’s not financially comparable to the legacy mega-franchises. The concern isn’t whether Nexon can make good games—it’s whether it can make the next global, enduring platform.

Governance Complexity. The holding company structure, the government’s unsold NXC stake, and the post-founder era all add uncertainty. CEO Junghun Lee may execute well operationally, but the alignment across public shareholders, the Kim family’s ongoing control, and the Korean government’s position as a large minority holder remains a complicated backdrop.

Regulatory Risk. Nexon has already taken heat for monetization practices. In 2024, the Korea Fair Trade Commission fined Nexon ₩11.6 billion (about $8.9 million) for misleading players about microtransactions in MapleStory, citing violations of South Korea’s consumer protection rules for electronic commerce. Ongoing scrutiny—especially around randomized mechanics like loot boxes—could force changes that reduce monetization or raise compliance costs.

Valuation. Games are inherently hit-driven. Nexon’s investment case asks you to believe two things at once: that aging franchises can keep compounding, and that new launches will replenish the portfolio. If either leg weakens, paying up for legacy cash flows can look expensive in hindsight.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate): Building a global live-service machine takes capital and expertise, but smaller studios can still break out with the right game. The market can surprise you, and new distribution channels make it possible for newcomers to emerge fast.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): Nexon develops much of its content in-house and isn’t overly dependent on a small set of external suppliers for its core products.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate): In free-to-play, players can quit instantly. The counterweight is stickiness: social networks, time investment, and identity inside a long-running game can be powerful retention forces.

Threat of Substitutes (High): Nexon doesn’t just compete with other games. It competes with everything that can absorb attention—streaming, social media, short-form video, and whatever else fills a spare hour.

Competitive Rivalry (High): Gaming is one of the most competitive industries in the world, with deep-pocketed rivals like Tencent and NetEase, major Western publishers, and an endless supply of mobile competitors fighting for the same player time.

Key Metrics to Track

If you want to track whether Nexon’s story is strengthening or cracking, a few metrics tend to tell you early:

-

Daily Active Users (DAU) by Franchise: The oxygen of live-service games. DAU erosion usually shows up before revenue declines, and it can be hard to reverse once momentum shifts.

-

Average Revenue Per User (ARPU): A read on monetization quality. Stable or rising ARPU with stable DAU is healthy. Rising ARPU alongside falling DAU can be a warning sign that monetization is getting too aggressive, too late.

-

Geographic Revenue Mix: China is both the prize and the pressure point. Watching the balance across Korea, China, Japan, and the West helps reveal whether Nexon is diversifying—or becoming even more dependent on a single market.

XII. Conclusion: The Legacy and the Lesson

Nexon’s story, at its core, is about understanding what players actually want—and having the patience to serve them for decades, not quarters.

Kim Jung-ju didn’t set out to rewrite gaming economics. He built a company during South Korea’s internet boom, shipped early online worlds, and then, when a subscription game started to die, tried a last-ditch experiment: make it free and sell optional items. QuizQuiz wasn’t supposed to become a business model. It was supposed to be a rescue. But that rescue turned into the playbook that would go on to power a huge share of modern gaming.

And Nexon didn’t just pioneer an idea. It lived the consequences of building a founder-controlled empire. After Kim’s death, the succession laid bare a set of structural realities that don’t show up on a quarterly earnings call: inheritance taxes large enough to force stock transfers, holding-company structures that complicate control, and the messy work of moving from founder intuition to professional management.

What makes Nexon distinctive isn’t any single hit. It’s the operating belief that games can be run like living services—worlds you tend over time—rather than disposable products you ship and replace. Owen Mahoney captured it cleanly: “Building online experiences for multi-year sustained growth is one of the most powerful ideas in games.” In other words, Nexon rejects the “pump-and-dump” impulse that burns trust, churns communities, and shortens a game’s life.

That philosophy is why MapleStory can still be setting records more than twenty years in. It’s why Dungeon Fighter Online became one of the biggest entertainment businesses on earth. And it’s why almost every successful live-service game since has tried, in some form, to recreate what Nexon learned early: the real asset isn’t the launch—it’s the relationship.

The open question in Nexon’s next chapter is simple and brutal: can it do it again? Can it create new franchises with the same longevity as the founding era’s giants, or were MapleStory and Dungeon Fighter lightning strikes that can’t be repeated? Nexon’s slate of major launches planned through 2027, its expanding partnership with Tencent, the Mintrocket experiment, and the post-founder management era are all different ways of answering that question with action.

For investors, Nexon is a rare profile in games: a pioneer with proven staying power, a fortress balance sheet, and a meaningful path into the world’s biggest gaming market. The risks are real too—China concentration, dependence on aging franchises, and governance complexity that doesn’t neatly disappear just because the operating business is strong.

But the enduring lesson of Nexon isn’t about revenue models or market timing. It’s about respect. Kim Jung-ju built a company around the idea that games are relationships, not transactions—and that treating players well isn’t just ethical, it’s good business. More than two decades after free-to-play was born, that insight remains Nexon’s most durable advantage.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music