TIS Inc.: Japan's Quiet Giant Powering the Invisible Infrastructure

Introduction: The Company You've Never Heard Of That Runs Japan's Money

Try a quick thought experiment.

You’re in a Tokyo convenience store, tapping a card for an onigiri. Or you’re in Osaka, paying a restaurant bill with your phone. Or zoom out even further: millions of salaries moving, on schedule, from corporate accounts into employees’ bank accounts across the country.

Different moments, same underlying requirement: the transaction has to clear flawlessly, every time. And in Japan, there’s a good chance that reliability is being delivered by a company most global investors couldn’t pick out of a lineup: TIS Inc.

TIS sits in an unusually powerful spot inside Japan’s payment plumbing. Around 86% of Japanese payment processors use services like TIS’s Branded Debit Processing Service, which handles the end-to-end functions needed to issue and operate branded debit cards. It’s not flashy work. It’s the kind of work where “it worked today” is not the goal; “it never fails” is. Decades in financial IT have given TIS the credibility—and the institutional know-how—to help clients modernize systems, launch new products, and expand into new business areas without breaking what already works.

Zooming out, TIS is part of the TIS INTEC Group, a leading independent prime contractor in Japan’s IT services market—an industry supported by steady demand as companies keep investing in digital technology. The group has about 21,765 employees, generated roughly $4.0B in revenue in 2024, and carries a market cap of around $7.7B.

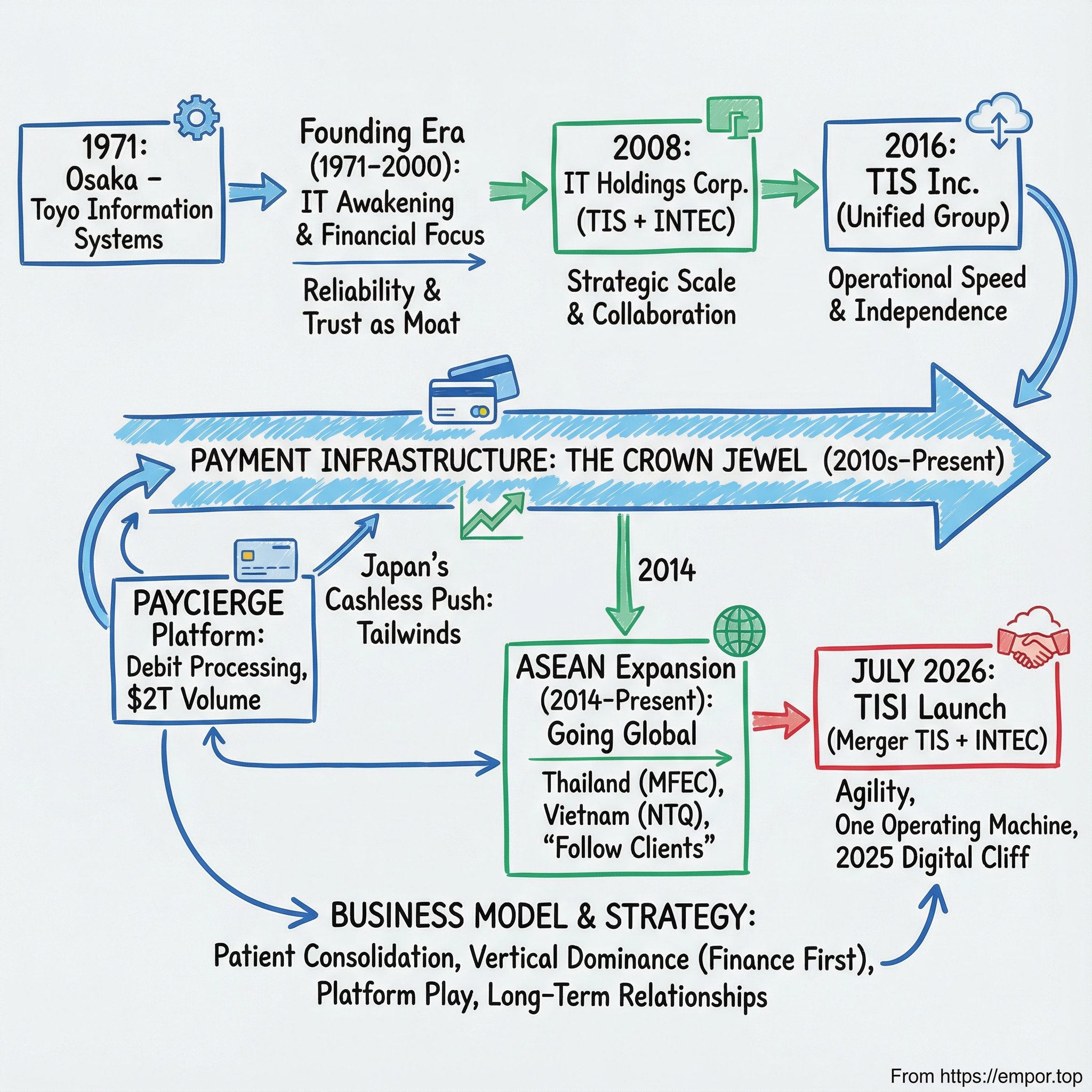

The thesis here is simple, even if the execution wasn’t: this is the story of how a 1971 outsourcing shop founded in Osaka became one of Japan’s most important IT infrastructure companies—by consolidating patiently, becoming indispensable in financial services, and making a deliberate bet on growth in ASEAN—while staying almost invisible in the global tech conversation.

Next, we’ll walk through TIS’s roots in Japan’s computing boom, the mergers that built scale, the payment infrastructure position that became its crown jewel, the push into Southeast Asia, and the upcoming integration that’s set to reshape the company for the next decade. Along the way, we’ll get clear on what makes the model work, where the moat really comes from, and what long-term observers should pay attention to.

The Founding Era: Toyo Information Systems and Japan's IT Awakening (1971–2000)

Setting the Scene: Osaka in the Early 1970s

To understand TIS, you have to start with the Japan that made it possible. It’s 1971. The country is still riding the momentum of the post-war economic miracle—industrial output is surging, exports are booming, and big companies are growing faster than their back offices can keep up.

That growth had a hidden constraint: information. Supply chains, payroll, inventory, and banking were becoming too complex to manage on paper and intuition. Mainframes were arriving, but making them useful required specialized skills most “traditional” companies didn’t have in-house. A market opened up for a new kind of business: the specialist that could run the machines, build the software, and keep the whole thing working, day after day.

That’s the world Toyo Information Systems was born into in Osaka in 1971. At the time, it wasn’t trying to become a household name. It was building a reputation in the unglamorous trenches of enterprise computing: operating data centers, writing custom systems, and taking responsibility for the parts of the business that couldn’t afford to go down.

Over time, Toyo Information Systems evolved into what we now know as TIS—part of the larger TIS INTEC Group, with businesses spanning service IT, financial IT, industrial IT, and BPO.

Why Financial Services Became the Anchor

Early on, TIS made a choice that quietly defined the next half-century: it leaned into financial services.

The timing was perfect. Japan’s consumer finance and card ecosystem was ramping up, and the systems behind it were brutally demanding. Processing transactions, reconciling accounts, producing statements, managing risk—none of it was forgiving. Banks and card companies didn’t just need software. They needed partners who could deliver reliability, security, and continuity for the long haul.

Working in finance for more than 50 years gave TIS exactly what matters most in regulated, mission-critical systems: accumulated know-how. Over time, it took on core development work for a meaningful share of Japan’s major credit card players—relationships that touched an enormous number of cardholders and a large portion of the country’s annual retail card transaction volume.

This is where the real compounding happens. Each year on these systems teaches you things you can’t learn from a specification sheet: how settlement actually works in practice, how regulations get interpreted, where failures tend to occur, and how legacy integrations behave under stress. That institutional memory becomes its own kind of moat. A competitor might show up with modern architecture and sharp engineers, but they won’t have decades of scar tissue—or the trust that comes with it.

From this, a philosophy emerged: the system integrator as trusted partner. TIS wasn’t just bidding on projects and moving on. It was embedding itself inside operations, building alongside clients, and becoming the steady hand that helps modernize without breaking what already works.

The Quiet Growth Years

Through the 1980s and 1990s—through boom, bubble, and bust—TIS kept building. It expanded its customer base, deepened its expertise across banking and insurance, and strengthened the reputation that matters most in this line of work: dependable.

In 1987, TIS completed its IPO. Public capital gave it more room to invest and expand, but the company’s growth style stayed disciplined and methodical.

By the time Japan entered the 2000s, TIS had become a serious player—but it was still operating in a crowded field. Japan’s IT services market was fragmented, with many mid-sized integrators competing on relationships and specialized know-how. And the keiretsu landscape mattered: companies tied to major corporate groups often had built-in lanes, especially when serving “family” clients.

TIS didn’t have that kind of captive demand. But independence created its own advantage: it could work across corporate boundaries, without being perceived as an extension of a rival group. The trade-off was scale. In this business, size increasingly determined who could take on the biggest, most complex, most long-lived programs.

And by the end of this era, that reality was becoming hard to ignore.

The seeds of consolidation were planted.

The Consolidation Era: IT Holdings and the Great Merger (2008–2016)

The Strategic Logic of Scale

By the mid-2000s, Japan’s IT services industry was running into a new reality: the work was getting bigger, broader, and more interconnected. Clients weren’t just buying a system anymore. They wanted end-to-end capability—cloud, data, mobile, security, and integration across old and new infrastructure. That demanded sustained investment in talent and technology, the kind that’s hard to fund when you’re stuck at mid-scale.

And Japan’s market had a lot of mid-scale.

Fragmentation, once a sign of healthy competition, started to look like a structural problem. Too many firms were chasing the same large, long-duration contracts. Pricing pressure increased. Hiring got tougher. The winners would be the companies that could build breadth, credibility, and delivery capacity at national scale.

In April 2008, TIS and INTEC took a decisive step: they formed IT Holdings Corporation. As TIS later put it, once IT Holdings became a joint holding company, TIS and INTEC began collaborating closely. The idea was straightforward—combine strengths without immediately forcing a full operational mash-up.

IT Holdings brought together two meaningful independent system integrators. TIS had deep roots in financial services, especially in card and payment-related systems. INTEC, based in Toyama Prefecture, brought complementary expertise, including manufacturing systems and strong regional client relationships. Together, they could credibly pitch a wider range of industries and a broader menu of services than either could offer alone.

The structure also created room for careful sequencing. In October 2009, INTEC Holdings merged with INTEC, with INTEC as the surviving company. And rather than rushing into a messy full integration, the group used the holding-company model to capture practical synergies—shared functions, coordination across sales, and tighter collaboration—while the core operating companies maintained their identities.

The 2016 Transformation

But holding companies are great for starting a marriage and not always great for running one.

By the mid-2010s, the pace of change was accelerating. Cloud computing was reshaping outsourcing. “Digital transformation” stopped being an optional initiative and became the default agenda item in boardrooms. Clients wanted unified solutions, delivered seamlessly—not a collection of capabilities spread across sister companies that collaborated when convenient.

So in July 2016, IT Holdings made the change that signaled the group was ready to operate as one. The company, formerly known as IT Holdings Corporation, changed its name to TIS Inc. That wasn’t just a branding exercise. IT Holdings executed an absorption-style merger with TIS, adopted the better-known name, and shifted to an operating holding company structure.

On paper, that sounds technical. In practice, it meant faster execution. TIS Inc. now sat at the center as both parent and operator—able to set strategy, allocate resources, and drive cross-group programs with fewer internal handoffs.

Under the unified TIS INTEC Group identity, TIS provided the full range of IT solution services: system integration and entrusted development, plus service-style offerings like data center and cloud services. The group also expanded its ability to support customers globally, building a network centered on China and the ASEAN region and working with more than 3,000 business partners across industries.

Independence as Competitive Advantage

There’s another ingredient that matters a lot in Japan, and it’s easy to miss if you’re used to how tech services works elsewhere: TIS operates without a controlling shareholder.

In a landscape filled with IT arms tied to corporate groups—companies whose biggest customers are often their parent or their parent’s affiliates—TIS is structurally neutral. The TIS INTEC Group positioned itself as a major independent corporate group, free from keiretsu ties. That independence gave management the flexibility to make decisions quickly and pursue business development without having to optimize for a parent conglomerate’s priorities.

It cuts both ways. TIS doesn’t get a guaranteed stream of work from a parent ecosystem. It has to win on trust, track record, and capability.

But in relationship-heavy, risk-sensitive industries—especially finance—that neutrality can be a superpower. If you’re a bank, you don’t necessarily want your most sensitive systems built by the IT subsidiary of a rival corporate group. If you’re a manufacturer, you don’t want vendor recommendations shaped by internal politics. TIS can walk into those rooms as a prime contractor without the baggage.

By 2016, the company had evolved from a strong mid-sized player into a scaled group with roughly 130 affiliates and a workforce in the tens of thousands—large enough to go toe-to-toe with Japan’s biggest IT services firms when the projects were complex and mission-critical.

And now that scale was in place, the most valuable asset in the portfolio was about to matter even more: the payment infrastructure that sat quietly underneath Japan’s everyday commerce.

Payment Infrastructure: The Crown Jewel (2010s–Present)

Becoming Japan's Payment Backbone

In tech investing, people love to talk about “picks and shovels” businesses—the ones that profit no matter which shiny new product wins. TIS is that idea taken to an extreme. It doesn’t build the consumer-facing apps. It runs the machinery underneath them. And in payments, that machinery is so deep in the stack that most people never realize it’s there.

Start with what TIS actually touches. Through its PAYCIERGE payment system, TIS processes roughly $2 trillion in annual volume and is involved in about half of Japan’s credit card transactions. On the debit side, its Branded Debit Processing Service is used by about 86% of Japanese payment processors, supporting hundreds of millions of debit card transactions a year, worth trillions of yen.

If you live in Japan, the practical implication is simple: when you pay with a branded debit card—especially one tied to the big international networks like Visa, Mastercard, or JCB—there’s a high probability TIS is in the middle of that transaction, making sure it clears cleanly.

Zoom out and you can see why this matters. Japan has issued an enormous number of debit cards, and debit usage has risen into the hundreds of millions of transactions annually. Most of those payments run on international-brand rails. TIS’s role isn’t a nice-to-have add-on; it’s end-to-end infrastructure. The service covers what issuers need to actually operate branded debit cards—issuing, processing, and the operational functions that keep the whole thing reliable.

This isn’t “market leadership” in the way a consumer brand leads a category. It’s closer to a near-utility position in a critical layer of Japan’s payment system.

PAYCIERGE: The Platform Play

In 2014, TIS packaged its retail payment solutions under a single name: PAYCIERGE—short for “Payment” and “Concierge.” It’s a telling choice. TIS isn’t pitching itself as a one-off vendor that shows up, installs software, and disappears. It’s presenting itself as the steady guide that helps financial institutions and payment players navigate a fast-changing payments world.

PAYCIERGE is a platform used to provide payment solutions, and it became one of TIS’s mainstay businesses. The promise is breadth: issuing branded debit, integrating merchant acceptance, and supporting new payment methods alongside the old ones—without forcing clients to gamble the stability of systems that can’t afford downtime.

TIS has also positioned PAYCIERGE as an evolving concept. “PAYCIERGE 2.0” reflects that the payments market doesn’t sit still—and that security, operations, and reliability have to scale along with new features and new rails.

The business model shift here is the quiet unlock. Traditional systems integration is project-driven: win the work, deliver, move on. A platform flips that dynamic. It creates ongoing processing relationships and recurring service revenue. It’s still infrastructure, but it behaves less like a contractor and more like a utility—embedded, sticky, and compounding over time.

Japan's Cashless Push Creates Tailwinds

TIS’s dominance in payment infrastructure has aligned perfectly with a national push that’s been building for years: Japan going cashless.

By 2024, Japan’s cashless payment ratio reached 42.8%, clearing the government’s 40% target. METI has indicated it will keep pushing improvements with an eye toward 80% over time. The mix matters too: credit cards make up the majority of cashless payments, with debit, electronic money, and code payments taking smaller shares.

For TIS, this is the kind of tailwind infrastructure businesses dream about. More cashless adoption doesn’t just mean more apps—it means more transaction volume that has to be authorized, cleared, settled, reconciled, and secured. In other words: more work flowing through the pipes TIS already owns.

And that growth hasn’t been purely organic. The COVID-19 era accelerated contactless behavior, and policy incentives—like point reward programs—helped pull more consumers into digital payments. The trendline moved, and the underlying systems had to keep up.

Blockchain and the Next Frontier

What’s easy to assume, when you hear “mission-critical infrastructure,” is that the company will sit back and defend the legacy stack. TIS has done something more interesting: it’s tried to make itself the upgrade path.

Fireblocks, a digital asset security and infrastructure provider, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC Group), alongside Ava Labs and TIS. The goal: explore stablecoins for wholesale payments—an early signal that major institutions in Japan are actively evaluating how digital money could streamline large-value flows.

Then, in October 2025, TIS launched its Multi-Token Platform on Avalanche’s AvaCloud, a managed blockchain service. TIS spent two years building a platform designed to handle three categories of digital money: stablecoins for instant payments, tokenized deposits for institutions to move liquidity digitally, and digital securities intended to simplify issuance and trading.

The important point isn’t that TIS “did blockchain.” It’s what it’s attempting to connect. TIS already processes roughly $2 trillion annually through PAYCIERGE and supports a huge share of Japan’s card activity. The Multi-Token Platform is positioned as a way to bring that real-world scale to blockchain rails—turning decades of payment operations into programmable infrastructure without asking the market to start from scratch.

Strategically, it’s a very TIS move. Rather than treating blockchain as a threat, it treats it as an extension. Its distribution advantage isn’t an app store ranking—it’s relationships: banks, card companies, and the institutions that already trust TIS with systems that cannot fail. Any competitor can try to build new rails. Very few can pair that with fifty years of credibility in regulated, high-stakes finance.

TIS’s presence in forums like the Bank of Japan’s CBDC Forum reinforces the same theme: it wants to be close to wherever the next version of money lands.

If Japan eventually launches a central bank digital currency, that won’t automatically decide which infrastructure wins. But it would make the battle for “who connects the new money to everyday commerce” very real—and TIS is clearly positioning itself to be one of the companies ready to do that work.

The ASEAN Bet: Going Global from Japan (2014–Present)

The Strategic Rationale

For decades, Japanese IT services companies lived with a built-in ceiling: Japan itself. The market could be strong—especially as digital transformation ramped—but the country’s demographics were moving in only one direction. An aging, eventually shrinking population meant that long-term, domestic growth would get harder.

TIS chose to look south.

As part of its broader transformation agenda, TIS pursued an overseas strategy aimed at becoming a top-class IT group in the ASEAN region. And it didn’t do it by opening a small office and hoping for the best. It pushed a deliberate playbook: expand business domains through capital and business alliances and other forms of cooperation with leading local companies.

The logic was straightforward. ASEAN markets—Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia—offered what Japan couldn’t: younger populations, rising middle classes, and huge unmet demand for modern IT. They were also familiar terrain for Japanese corporations that had spent decades building manufacturing and regional operations across Southeast Asia. For TIS, that meant an on-ramp: start by supporting existing Japanese clients abroad, then widen into local enterprise demand.

But the ambition went further than simply “following clients.” TIS saw a chance to bring one of its home-market strengths—payments and financial IT—into markets where the infrastructure was still being built and where digital-first solutions could scale quickly.

The MFEC Acquisition: Thailand as Beachhead

The centerpiece of this ASEAN push was Thailand, and the anchor partner was MFEC Public Company Limited.

In 2014, TIS formed a capital and business alliance with MFEC, a major Thai system integration specialist, and also acquired IAM Consulting, an SAP consulting firm. In April of that year, MFEC entered into the alliance with TIS Co., Ltd. of the TIS INTEC Group to expand services to Japanese companies operating in Thailand.

MFEC wasn’t a small bet. Established in 1997, MFEC Public Company Limited (PCL) grew into Thailand’s largest IT services enterprise. The MFEC Group serves more than 700 large enterprise clients across industries including banking and finance, healthcare, manufacturing, the public sector, and telecommunications.

At the start, TIS’s investment was designed to be strategic rather than fully controlling: a minority stake that preserved independence while the two companies built trust, tested joint offerings, and learned how to operate together across borders.

That relationship deepened over time. In 2020, TIS decided to consolidate its Thailand position. TIS’s Board resolved to acquire MFEC shares via a tender offer under Thailand’s securities exchange law and other local regulations. At that point, MFEC was already a TIS affiliate accounted for by the equity method—and TIS framed consolidation as meaningful for building a top-class IT group in ASEAN, accelerating restructuring at MFEC, and expanding the scale of overseas operations within the TIS INTEC Group.

The tender offer also highlighted the realities of cross-border M&A in the region. MFEC’s board rejected the bid, citing an inadequate offer price: THB 5 per share versus what it described as a fair value of THB 6.32 per share. Even so, TIS ultimately acquired a controlling stake, and MFEC became part of TIS’s consolidated group.

The Payment Play in ASEAN

MFEC was strategically valuable on its own—but one subsidiary made it especially important to TIS: PromptNow, which specializes in mobile payment applications for financial institutions.

TIS praised PromptNow’s strategy to expand payment solutions in Thailand and decided to position it as the platform for TIS’s payment-related business there. The timing helped. Thailand’s national e-payment master plan signaled major growth potential in payment solution services—exactly the kind of policy-driven tailwind that had supported Japan’s own cashless push.

This wasn’t accidental. TIS was aiming to apply a familiar playbook in a faster-moving market: use deep experience in payments and banking to become part of the rails, not just another vendor selling one-off projects.

TIS also framed this work in broader terms than commerce. The company has been applying its strengths in payments and banking to address public concerns in ASEAN, including traffic congestion, the wealth gap, and food waste. Its first focus area was financial inclusion—efforts to remove barriers to accessing financial services based on age, gender, or net worth. To pursue that, TIS has sought partnerships with both local and global players, aiming to co-create new value in the payment market.

In developing economies, that inclusion lens is practical strategy, not just a slogan. When millions of people still sit outside traditional banking, the first widely adopted “bank account” may be a phone. Whoever helps build the systems behind that shift can end up embedded in the next decade of commerce.

Expanding the Network: Vietnam and Beyond

Thailand was the entry point, not the endpoint. At the turn of 2025, TIS extended its footprint into Vietnam through a capital and business alliance with NTQ.

NTQ announced on January 21, 2025 that it had entered into a strategic capital and business alliance with TIS. TIS, for its part, stated it entered into the alliance with NTQ SOLUTION JOINT STOCK COMPANY on December 23, 2024, making NTQ an equity-method affiliate.

NTQ was founded in Hanoi in 2011 and has grown into a leading Vietnamese IT service provider, with offices spanning Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, North America, and Europe, and a workforce of more than 1,300 people.

TIS has positioned Asia—given its market potential—as a core target of its long-term global strategy, with a goal of expanding in ASEAN and reaching consolidated revenue of ¥100 billion by fiscal 2026. That target matters because it would move ASEAN from “overseas optionality” to something that can genuinely influence the shape of the whole company.

The broader network is already in place. TIS operates through subsidiaries in Japan, China, the U.S., Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Singapore—creating coverage across key regional markets and a base for both organic growth and further partnerships.

And the original flywheel remains central: follow clients, then widen. Many Japanese companies run manufacturing and distribution operations across Southeast Asia. If TIS can support those customers consistently across countries, it increases switching costs in a very real way. The alternative isn’t just choosing a different vendor—it’s coordinating multiple vendors across multiple geographies, without the benefit of a partner that already understands the client’s systems end to end.

The 2026 Merger: TIS + INTEC = TISI

The Announcement and Rationale

After almost two decades of operating as a group built around two core companies, TIS decided it was time to finish the job.

In July 2025, TIS announced plans to merge fully with its subsidiary, INTEC Inc. The structure is straightforward: TIS will absorb INTEC, with TIS as the surviving entity. The newly formed company will take a new name—“TISI”—and is scheduled to launch on July 1, 2026.

TIS framed the move as a speed play. Management pointed to its long-term strategy, “Group Vision 2032,” established in May 2024, and argued that the business environment is changing too quickly to keep running a two-core-company model.

The backdrop matters. Japan’s IT services market was expected to keep growing, but the demand mix was shifting toward large-scale modernization: core-system renewals heading into the “2025 Digital Cliff,” government support for Society 5.0 initiatives, and cloud-first procurement rules for public agencies.

The “2025 Digital Cliff” is the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s warning that decades-old legacy systems are reaching end-of-life—and that delays in modernization could impose severe economic costs. The problem is familiar: heavily customized, on-premise systems that became “black boxes,” difficult to maintain and even harder to replace. METI has warned that failure to modernize could lead to annual economic losses approaching US$80 billion.

For TIS, that creates a rare combination of opportunity and urgency. Modernization work is large, complex, and time-sensitive. Winning it depends on how quickly you can mobilize talent, investment, and decision-making—without internal seams slowing you down.

Synergy Expectations and Organizational Changes

This merger isn’t being sold as a name change. It’s being pitched as a structural reset in how the group runs.

TIS said the integration is meant to improve agility in capital allocation and decision-making, and to strengthen its ability to co-create value with clients and society. In plain terms: one management team, one set of priorities, and a clearer ability to place bets—especially on technology investment and specialized talent—without negotiating across internal boundaries.

TIS also disclosed that merger-related expenses were expected to total about ¥20–30 billion across fiscal 2026 and fiscal 2027, and it referenced synergy effects on a fiscal 2033 single-year basis.

That expense line tells you something important: this is not a cosmetic reorganization. Real integrations cost real money—consolidating overlapping functions, unifying internal systems, and moving work into shared-service structures. TIS signaled it was planning that kind of deep integration, not just stapling two org charts together.

Alongside the operational integration, TISI will also adopt a governance structure with an audit and supervisory committee. That shift is typically associated with stronger oversight and clearer accountability—often an effort to meet institutional investor expectations around governance and transparency.

What This Means for the Future

If the 2008 creation of IT Holdings was the start of the marriage, the 2026 TISI launch is the decision to share a single household—one balance sheet, one management structure, and one operating model.

That matters competitively. The current setup—two core companies under common ownership—can create friction: duplicated support functions, overlapping territories, and internal complexity that slows down cross-group execution. A unified TISI should be able to show up to customers as one organization, staff programs more flexibly, and make faster decisions on where to invest and how to deliver.

And it matters for observers trying to understand the business. Removing another layer of corporate structure should make the story easier to read: cleaner reporting, clearer accountability, and a more direct link between strategy, execution, and results.

In other words, TIS is trying to enter the next phase of Japan’s modernization wave not as a federation, but as a single operating machine—built for speed, scale, and the kind of reliability its customers have always demanded.

Business Model Deep Dive: How TIS Actually Works

The Five Segments

To really understand TIS, you have to stop thinking in terms of “projects” and start thinking in terms of how the company is organized to monetize long-term complexity. TIS INTEC Group runs the business across five segments—each one a different way of selling trust, execution, and continuity.

The BPM segment delivers process improvement and outsourcing solutions using IT, business expertise, and human resources. The Financial IT and Industrial IT segments develop and promote business and IT strategies tailored to the financial sector and other industries, respectively. The Offering Service segment provides knowledge-based IT services built on the Group's expertise and investments. The Wide Area IT Solution segment offers professional IT services across regions and customer sites to support problem-solving and business growth.

Financial IT is the crown jewel. This is where payment systems, core banking, insurance platforms, and securities systems live—and where TIS’s reputation for “never fails” reliability turns into recurring demand. It’s also the segment most directly leveraged to the company’s branded debit processing position and PAYCIERGE, with growth pulled forward by Japan’s broader shift toward cashless payments and reinforced by newer initiatives like digital-asset infrastructure.

Industrial IT is the other big engine: systems for manufacturers, distributors, service businesses, telecom, and the public sector. It tends to be more competitive and more project-driven than financial IT, but it’s also where TIS can take its integration muscle—making legacy systems talk to cloud systems talk to data systems—and apply it across the rest of the economy.

Offering Services is the subtle business-model upgrade. Instead of building something bespoke for one client and walking away, this segment is about reusable platforms and solutions that can be deployed across many customers. When it works, the economics look less like “hours billed” and more like “products adopted”—more repeatable, more scalable, and often more margin-accretive than pure custom development.

Business Process Management (BPM) is TIS stepping beyond software into running the operation itself. It’s not just “here’s the system.” It’s “we’ll operate the process”—using IT plus people plus domain know-how to take on functions that clients don’t want to staff or rebuild internally.

Wide Area IT Solution is the group’s way of serving customers outside the biggest metro centers—supporting regional enterprises and local governments with the same toolkit, just deployed closer to where the work actually happens.

The Client Relationship Model

One of TIS’s most valuable assets doesn’t show up neatly in a financial statement: the duration of its customer relationships, and what those relationships allow it to become.

TIS INTEC Group's TIS Inc. offers a broad range of IT services and solutions including systems integration, data centers, and cloud infrastructure. The company's global support system focuses on China and the ASEAN region. TIS serves over 3000 companies in various industries such as finance, logistics, manufacturing, public organizations, services, and telecommunications.

In Japan, these relationships often aren’t measured in quarters—they’re measured in decades. A client might start with TIS on a discrete build, then expand into operations, then expand again into modernization, security, cloud migration, and platform services. Over time, TIS stops being “a vendor” and becomes part of how the business runs.

That creates one of the strongest moats in enterprise IT: switching costs. And nowhere is that more intense than financial services. When TIS systems sit in the middle of mission-critical flows, replacing them isn’t like swapping a tool—it’s like performing open-heart surgery while the patient keeps running. Any transition can require years of parallel operation, heavy testing, regulatory approval, and a willingness to accept real operational risk. So even if a competitor shows up with a shiny proposal, the default answer is usually: why gamble?

Innovation Areas

TIS’s public image can read like a “traditional integrator,” but the company has been investing in the technologies that its clients are being forced to confront.

The company offers solutions such as payment, digital marketing, enterprise, its platform and security, and artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.

The robotics work stands out in Japan’s demographic reality. With the workforce shrinking and the population aging, automation isn’t a nice productivity boost—it’s a requirement to keep operations functioning. TIS has been positioning itself to support everything from process automation to robotics deployments in industrial settings, plus AI-driven tools that help organizations make decisions faster and operate with fewer people.

And then there’s blockchain, which ties back to the core thesis: TIS doesn’t want to be disrupted by the next version of financial infrastructure. It wants to be the company that installs it, integrates it, and operates it. The Multi-Token Platform is part of that bet—built on the expectation that as Japan’s digital-asset and stablecoin frameworks mature, the winners won’t be the loudest experiments, but the systems that institutions trust enough to put into production.

Playbook: Business and Strategy Lessons

TIS’s journey—from a no-frills outsourcing shop in Osaka to one of Japan’s most important pieces of payment infrastructure—has a few repeatable lessons baked into it. Not the hype-cycle kind. The compounding kind.

Patient Consolidation Over Flashy Acquisitions: TIS didn’t swing for the fences. It built scale through moves it could absorb: forming IT Holdings, collaborating closely with INTEC for years before deeper integration, and taking a measured approach in Thailand with MFEC. Each step was sized to be survivable—and that gave management time to learn what worked before committing to the next move.

Vertical Dominance Before Horizontal Expansion: TIS didn’t start by trying to serve every industry with equal intensity. It went deep where reliability matters most—financial services IT, especially payments—then used that credibility to broaden out. In a business where trust is the product, depth beats breadth early on.

The "Follow Your Clients" International Strategy: Instead of planting flags with greenfield expansions, TIS used a lower-risk entry: Japanese companies already operating across ASEAN. That meant the first overseas work started with customers TIS already understood, then widened into local demand once it had real on-the-ground capability.

Independence as Competitive Advantage: In a market where many IT providers are tied to larger corporate groups, TIS’s neutrality is a differentiator. It can walk into sensitive situations—especially in finance—without looking like an extension of a rival ecosystem. For clients who care about objectivity and confidentiality, that matters.

Platform Thinking in B2B: PAYCIERGE is the clearest example of TIS moving from “projects” to “infrastructure.” Platforms turn systems integration from a series of one-time builds into long-running operating relationships. The result is stickier customers, more predictable revenue, and a business that compounds instead of resetting every time a project ends.

Long-Cycle Investment Horizon: TIS’s biggest advantage is time. Decades-long client relationships aren’t just durable—they accumulate institutional knowledge: how a customer’s systems actually behave, how their operations really run, and what they will and won’t change. That’s the kind of context competitors can’t buy off the shelf. It becomes switching costs at their most absolute: not just hard to replace, but risky to even attempt.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MEDIUM

If you want to compete with TIS where it’s strongest—financial services IT—you don’t just need good engineers. You need regulatory credibility, security maturity, and the kind of domain expertise that usually takes years of operating in production to earn. These are mission-critical systems. They don’t get swapped out lightly. Switching costs are punishingly high, because a bank can’t “move fast and break things” when payments and settlement are on the line.

But the walls aren’t equally high everywhere. In the parts of IT that are less regulated and less central—analytics, customer engagement tools, modular fintech services—cloud-native players and global SaaS vendors are lowering the barrier to entry. With hyperscalers like AWS and Azure handling infrastructure, newer specialists can target narrow slices of the stack and start to nibble at the edges of what used to be integrator territory.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

On most inputs, TIS isn’t unusually exposed. It buys largely standard hardware, software licenses, and services, and its scale gives it leverage with technology vendors.

The real supplier constraint is people. Engineering talent is the bottleneck in Japan, where demographic pressure makes hiring more competitive. That does create pockets of supplier power—experienced developers, security specialists, and financial IT veterans can name their price. TIS has tried to blunt that risk by investing in training and by drawing on talent pools in ASEAN, where it’s already been building a footprint.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

TIS sells to sophisticated customers: major banks, card companies, and large enterprises. They negotiate hard, push for volume discounts, and have the procurement muscle to demand favorable terms.

And yet, in TIS’s most strategic niche, the usual buyer power gets checked by a simple reality: credible alternatives are limited. When TIS effectively sits in the middle of branded debit processing at scale, negotiating becomes less about “who’s cheaper” and more about “who can actually carry the risk.” In mission-critical infrastructure, the vendor that can reliably deliver often has more leverage than the buyer would like.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM (and Rising)

Substitution pressure is real, and it’s increasing. Cloud platforms can replace chunks of what used to require custom infrastructure and on-prem deployments. SaaS can take workloads that once demanded bespoke development and ongoing integration work.

But in heavily regulated financial services, the “just use a product” answer only goes so far. Banks and payment operators still need custom integration, specialized controls, and deep operational fit that off-the-shelf solutions often can’t provide.

The more interesting substitute isn’t one monolithic platform—it’s modularization. Fintech vendors can deliver narrow, modern capabilities that customers stitch together into a stack, slowly reducing how much work flows through traditional integrators. It doesn’t replace TIS overnight. It changes the shape of demand at the margins first.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Rivalry in Japan’s IT services market is intense. The competitive set includes domestic giants like NTT Data Group, Nomura Research Institute, SCSK, BIPROGY, and NS Solutions, alongside international firms such as Accenture and IBM. And beyond the headline names, there’s a long tail of competitors across consulting, outsourcing, and specialized IT services—including Alithis Group, CGI Group, Mitsubishi Research Institute, Astadia, and Sutherland Global Services.

This is a bidding market. The biggest deals attract multiple credible players, and competition shows up everywhere: recruiting battles, pricing pressure, and differentiation through domain specialization.

TIS’s advantage is that the most valuable part of its portfolio—payment infrastructure—is not a “most bidders win” business. It’s a trust-and-continuity business. That moat doesn’t eliminate rivalry across the rest of the market, but it does give TIS a defensible core even when the perimeter is hotly contested.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

TIS INTEC Group operates at real national scale: tens of thousands of employees and roughly 130 affiliates. That matters in IT services because the fixed costs are everywhere—data centers, security programs, training, platform development, delivery processes, sales coverage. With shared infrastructure like PAYCIERGE and the ability to cross-sell across group companies, TIS can spread those costs across a much larger base than smaller competitors. The result is a quiet advantage: it can invest more, standardize more, and deliver more consistently—without needing to charge “premium boutique” pricing.

Network Effects: MODERATE

Payments is one of the few places in TIS’s portfolio where network effects show up. The more issuers, merchants, and processors that run through a shared payments platform, the more valuable and defensible that platform becomes—because it becomes integrated into how the ecosystem functions day-to-day.

TIS has articulated a global vision of building a merchant payment business network with a strong presence across Asia. That said, most of TIS’s traditional system integration work doesn’t naturally compound through network effects. SI scales through people, process, and trust—not through flywheels of users.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

TIS isn’t a classic disruptor. It doesn’t win by radically undercutting incumbents or rewriting the category from scratch. In many ways, it succeeds by doing the opposite: fitting into the existing enterprise and financial-services world and making it run better.

Where it does differentiate is structural. Its independence from keiretsu ties can act like a form of counter-positioning against captive IT subsidiaries. When a client wants a prime contractor that isn’t implicitly aligned with a rival corporate group, TIS can be the “neutral” choice.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the heart of the moat.

Core banking systems, payment processing infrastructure, and regulatory compliance platforms don’t get swapped on a normal vendor cycle. They have replacement timelines measured in many years, because replacement means parallel runs, exhaustive testing, regulatory scrutiny, and real operational risk.

And beyond the code, there’s the hard-to-copy layer: institutional knowledge. TIS’s long-lived relationships embed operational context that can’t be replicated quickly by a competitor. For a risk-averse financial institution, switching payment processors isn’t just expensive. It’s a career-risk decision.

Branding: MODERATE

Inside Japan’s financial services world, TIS has the kind of brand that matters most in infrastructure: trusted, capable, safe. Outside of that, especially globally, it’s far less visible—partly because its biggest wins sit behind the scenes.

The upcoming shift to the TISI name and a more unified group identity should make the brand clearer and more cohesive, at least for customers and investors trying to understand the organization as one operating company.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Some inputs in IT are commoditized. Financial-services systems expertise is not.

Specialized talent in payment processing and regulated financial IT is scarce, and TIS has accumulated it over decades. On top of that, deep relationships with megabanks and major credit card companies create access that’s hard for newcomers to manufacture.

And regionally, TIS’s investments—like MFEC in Thailand and the alliance with NTQ in Vietnam—add a practical advantage: local delivery capacity and market presence in ASEAN, where talent and customer proximity matter.

Process Power: STRONG

TIS’s edge is also operational. Running high-reliability systems in regulated environments forces discipline: change management, incident response, quality control, security practices, documentation, and delivery rigor. Those processes get refined over years, and they become a competitive advantage when customers prioritize “it cannot break” over “it’s slightly cheaper.”

In other words, TIS doesn’t just sell technology. It sells a proven way of operating technology at scale.

Summary: Switching Costs + Process Power + Scale = a durable competitive position, especially in the core payment infrastructure business.

Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Japan’s digital transformation wave still looked early, and the demand backdrop for information services kept strengthening. In 2024, the market grew about 5.5% year over year to roughly ¥17.9 trillion—another signal that “information services” was becoming less of a support function and more of a core growth industry. As more companies committed to DX, the vendors that could actually execute the hard parts—modernization, integration, security, operations—stood to see years of follow-on demand.

The “2025 Digital Cliff” added a different kind of fuel: urgency. Companies that postponed replacing aging, heavily customized systems were running out of time. And this is exactly the kind of work TIS is built for. Decades spent inside banks, card companies, and other regulated environments translated into a practical advantage: it knows how to migrate and modernize legacy systems without breaking mission-critical operations.

Then there’s the crown jewel: payments. In the medium term, TIS’s position in branded debit processing is extremely hard to dislodge. When about 86% of Japanese payment processors depend on a service, that’s not just share—it’s embeddedness. If Japan’s long-term push toward higher cashless adoption continues, the simplest outcome is more volume flowing through the rails TIS already helps run. And the company’s blockchain work fits the same pattern: not a moonshot bet on disruption, but an attempt to make sure TIS is the safe, institution-ready bridge to whatever the next rails turn out to be.

ASEAN, meanwhile, offered something Japan can’t: demographic and economic tailwinds. If TIS could turn its overseas push into a meaningful second engine—management set a goal of reaching ¥100 billion in ASEAN revenue by fiscal 2026—it would reduce dependence on a maturing domestic market. The opportunity is especially clear in payments and financial IT, where many Southeast Asian markets are still building infrastructure that Japan finished building decades ago.

Finally, the planned shift to TISI mattered because it was about speed. Simplifying the structure and fully integrating TIS and INTEC was intended to make capital allocation and decision-making cleaner—fewer internal seams, faster moves on talent, technology investment, and any acquisitions that fit the strategy.

Bear Case

The biggest constraint on Japan’s IT services boom wasn’t demand. It was people. Labor shortages have been tightening for years, and METI has projected a shortfall of 790,000 IT professionals. If TIS can’t recruit and retain enough engineers, growth becomes theoretical—projects slip, delivery quality suffers, and the company ends up capped by headcount rather than opportunity. Even if revenue rises, wage inflation can squeeze margins.

Cloud disruption was the longer-term strategic question. TIS has leaned into cloud partnerships and platform development, but the broader industry shift—from bespoke development toward standardized cloud services—naturally advantages hyperscalers with massive ecosystems and global R&D budgets. In a world where more of the stack becomes “configurable” rather than “custom-built,” regional integrators can get pushed into tougher economics unless they control differentiated platforms or domain-specific infrastructure.

Competition also wasn’t standing still. Global firms like Accenture and IBM continued to target Japan, bringing global delivery models, offshore capacity, and packaged platforms that can pressure pricing—especially outside the most regulated, highest-trust parts of the market.

Even in payments—TIS’s strongest fortress—there were real risks. Regulation could shift in ways that invite new entrants. Fintechs could unbundle pieces of the value chain. And the most dangerous scenario is reputational: a major system failure in payments or banking can be a lasting scar in an industry that buys reliability above all else.

ASEAN expansion came with its own execution risk. Cross-border integration is hard, and mismatches in management style and culture can quietly degrade the value of an acquisition or alliance. And the revenue goal is ambitious. If overseas growth falls short, it raises an uncomfortable question: can TIS really build a durable second growth engine, or will it remain primarily tied to Japan’s domestic trajectory?

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For long-term investors watching TIS, a few signals matter more than the rest. Not because they’re flashy, but because they tell you whether the strategy is actually turning into a stronger business.

1. Financial IT Segment Operating Margin: This is where TIS’s most defensible work lives, including the payment infrastructure that functions like a utility. The key question is whether that business is becoming more platform-driven over time, rather than staying stuck in labor-heavy, project-by-project delivery. If margins expand, it’s a sign that PAYCIERGE and other service-style offerings are scaling. If margins compress, it can point to pricing pressure, higher delivery costs, or execution strain in the parts of the portfolio that can’t afford mistakes.

2. Order Backlog Growth: In IT services, backlog is tomorrow’s revenue taking shape today. TIS has seen orders received and order backlogs rise year over year, with backlog reaching record highs. That’s a strong signal that demand is still building. If backlog starts to flatten or fall—especially in specific segments—it’s often an early warning that the next few quarters may get harder, even if current revenue still looks fine.

3. ASEAN Revenue Contribution: TIS has been explicit about wanting ASEAN to become a real second engine, with a goal of reaching ¥100 billion in the region by fiscal 2026. The important part here isn’t just whether overseas revenue grows, but whether it grows consistently enough to prove the playbook works outside Japan. Hitting that trajectory would validate the alliances and acquisitions strategy. Missing it would raise the question of whether ASEAN remains “promising optionality” rather than a durable pillar of the company’s future.

Conclusion: The Infrastructure Play Hiding in Plain Sight

TIS is the kind of company that almost never makes the news, and almost always matters. It doesn’t ship consumer apps. It doesn’t have a celebrity founder. It isn’t built for viral moments.

It’s built for uptime.

TIS sits underneath Japan’s financial system and quietly makes the country’s commerce work the way people expect it to work: flawlessly. When you tap a card at a convenience store, there’s a meaningful chance TIS is somewhere in the flow, helping authorize and process the payment. When banks and large employers move money at scale—payroll, settlement, reconciliation—TIS is the type of partner doing the heavy lifting in the background. And as Japan explores what the next generation of money could look like, from stablecoins to tokenized deposits, TIS isn’t treating that as a science project. It’s positioning itself to be the connector between new rails and real-world, production-scale payments.

That’s why the TISI transformation, scheduled for July 2026, matters. It’s the company taking the last step from “group of closely linked cores” to “one operating machine.” After years of gradual integration, this is the move designed to simplify decision-making, tighten execution, and compete faster in a market that’s being reshaped by legacy modernization and a new wave of large, complex IT programs.

The opportunity set is clear. Japan still has years of system renewal ahead as companies confront aging infrastructure and the costs of delay. ASEAN offers a second growth engine with stronger demographic tailwinds and payment ecosystems that are still being built out at scale. TIS has already shown its preferred method: follow trusted clients, partner with local leaders, then bring its financial IT and payments playbook to new markets.

For patient investors, the appeal is rare in “technology” precisely because it doesn’t feel like tech hype. TIS combines a near-utility position in mission-critical payment infrastructure, platform-like recurring characteristics in businesses like PAYCIERGE, and long-duration tailwinds from cashless adoption and ongoing modernization.

The risks are real: talent constraints in Japan, the shifting economics of cloud and modular software, and the difficulty of executing cross-border expansion without losing focus or quality. But the core point remains: businesses don’t end up deeply embedded in systems that cannot fail by accident. They get there by earning trust over decades—and by continuing to adapt without breaking what already works.

The market is full of loud stories. TIS is a quiet one. And sometimes, the quiet stories are the ones doing the most work.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music