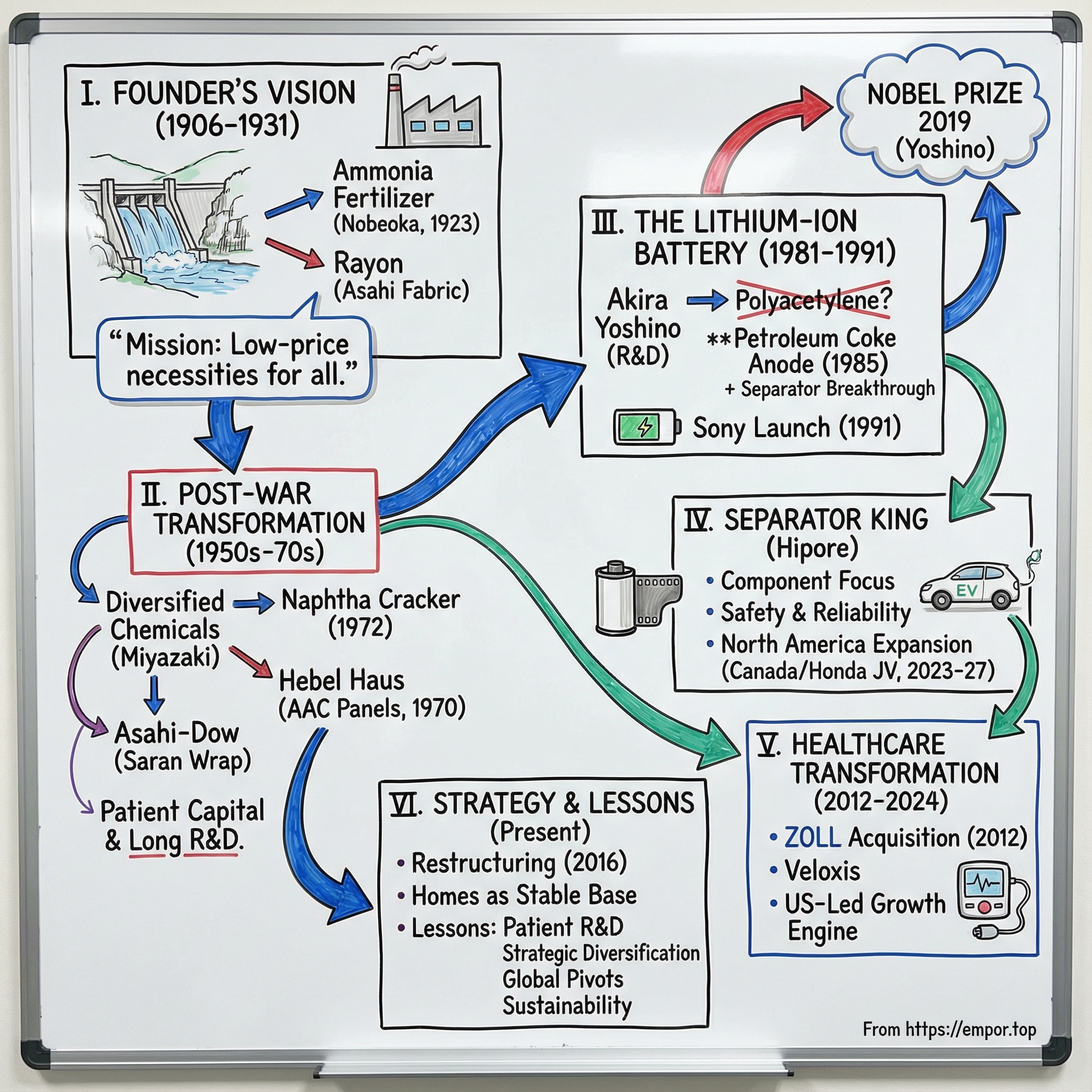

Asahi Kasei: From Ammonia to Nobel Prizes — A Century of Japanese Reinvention

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: Stockholm, December 2019. The Nobel Prize ceremony is in full, time-honored grandeur—the gilded halls, the Swedish royal family, the slow-roll pageantry of the world’s most famous scientific prize. Among the laureates sits a 71-year-old Japanese chemist named Akira Yoshino, dressed in white tie and tails.

He’s there for a technology so ordinary now that it’s almost invisible: the lithium-ion battery. The thing inside the phone you checked this morning. The thing inside the laptop you work on. The thing that made modern portable electronics—and, increasingly, electric cars—practical.

Now for the twist. Yoshino isn’t a tenured professor. He didn’t come out of a national lab. He spent his entire career at a company most people outside Japan couldn’t pick out of a lineup: Asahi Kasei Corporation.

Asahi Kasei is a 100-year-old Japanese conglomerate that began with synthetic ammonia for fertilizer. Today it spans materials, homes, and health care—building houses, manufacturing medical devices, and making the separator films that sit inside lithium-ion batteries and quietly decide whether they’re safe, reliable, and scalable.

So how does a chemicals company founded to help Japanese farmers end up enabling the smartphone era—and producing a Nobel Prize-winning inventor along the way? How does a Japanese industrial conglomerate, the kind that Western business schools often write off as a sprawling, unfocused relic, become a world-class engine of materials science innovation?

Zoom out and the scale is hard to ignore. Asahi Kasei is a major enterprise: roughly 50,000 employees, operations across multiple continents, and a portfolio that looks more like three companies than one. Yet outside Japan, it remains strangely anonymous—especially given how often its work ends up inside the products that define modern life.

Even its recent results underscore the contradiction. In fiscal 2024, Asahi Kasei grew net sales to ¥3,037.3 billion and lifted operating income to ¥211.9 billion. This is not a sleepy legacy manufacturer. And yet it still feels perpetually undervalued, perpetually misunderstood.

That’s why this story matters. Asahi Kasei is a case study in corporate reinvention—what happens when a company commits to patient R&D, keeps finding new arenas for its chemistry and materials expertise, and manages diversification without losing its edge. It’s also a story about constraints—Japan’s resource scarcity, geographic isolation, and the scars of war—and how those pressures can forge capabilities that last for generations.

And at the center is a simple, powerful theme: give talented researchers the freedom to chase new materials, and you sometimes get new industries.

From hydroelectric dams in rural Kyushu to a Nobel stage in Stockholm—from ammonia fertilizer to smartphone batteries to American health care—this is Asahi Kasei.

II. The Founder's Vision: Shitagau Noguchi and Hydroelectric Ambition (1906–1931)

The story begins not in a laboratory or a boardroom, but on the banks of a river in Kagoshima Prefecture, at Japan’s southern edge. It’s 1906. Japan has just stunned the world by winning the Russo-Japanese War and is racing to industrialize. But there’s a catch: it has almost none of the raw materials that powered America and Europe. No oil. Limited coal. A country with big ambitions and a thin resource pantry.

Shitagau Noguchi is exactly the kind of person that constraint produces. Born in 1873 in Kanazawa to a samurai-class family, he studies electrical engineering at Tokyo Imperial University (today’s University of Tokyo). He joins Siemens in 1898, then helps design Japan’s first commercial calcium carbide plant in Sendai in 1903. Noguchi understands something fundamental: Japan’s industrial future will run on electricity. And in Japan, electricity is going to come from water.

So in 1906, he builds a hydroelectric power station in Kagoshima—880 kilowatts, modest by today’s standards, but strategically enormous for its time. The insight is simple and powerful. Japan may not have oil fields, but it does have mountains, rain, and rivers—gravitational energy waiting to be converted into industrial horsepower.

The logic is elegant: use cheap hydropower to make energy-hungry chemicals that would otherwise require expensive imported fuel. It’s business strategy, yes. It’s also a bet on national self-sufficiency.

A decade and a half later, Noguchi aims that logic at one of Japan’s biggest vulnerabilities: fertilizer. In the early 1900s, Japan’s economy is still deeply agricultural, and demand for ammonium sulfate—an essential fertilizer input—is high. Domestic production is costly, and imports are a strategic risk.

In 1921, Noguchi takes a pivotal step. He buys a patent license for synthetic ammonia production technology—the Casale process—from Italian chemist and industrialist Luigi Casale, at a price equivalent to roughly 10 million euros today. When he acquires it, the technology is still in a pilot-stage form. But Noguchi’s organization—Nichitsu, his industrial group—does what Japanese industrial champions would become famous for: it takes imported know-how and engineers it into a scalable, commercially viable plant. The result is ammonium sulfate produced cheaply enough to beat incumbents and dominate the market.

In 1922, he lays the cornerstone for Japan’s first synthetic ammonia plant in Nobeoka, Miyazaki Prefecture. The plant begins operating in 1923. With the European process as a foundation and Japanese engineering discipline layered on top, Noguchi can produce ammonium sulfate domestically at low cost. In an era when feeding the nation is a central economic and political concern, this matters. Asahi Kasei makes history as the first company in Japan to synthesize ammonia for fertilizer.

Noguchi isn’t shy about the “why.” He frames the work as a moral project as much as an industrial one. “I want to solve the global food problems by providing low-priced fertilizer,” he says. “If people didn't have to worry about getting enough food, they wouldn't have to fight each other anymore.”

It’s consistent with the philosophy he repeats throughout his life: “Our ultimate mission is to improve people's standard of living by supplying an abundance of the highest-quality daily necessities at the lowest prices.”

And he doesn’t stop at ammonia. Around this same period, he’s looking at another import dependency: textiles. In the late Meiji era, artificial silk—rayon—is coming in from overseas as a substitute for silk. While traveling in Europe to implement ammonia synthesis technology, Noguchi becomes convinced rayon can be industrialized in Japan. He negotiates a technical partnership with the German company Glanzstoff, establishes a new company, and decides to take over the Zeze plant of Asahi Rayon.

This becomes Asahi Fabric, often described as the foundation of what eventually becomes Asahi Kasei. The name matters, too: the “Asahi” in Asahi Kasei traces back to Asahi Fabric.

What makes Noguchi so pivotal isn’t just what he builds. It’s the blend of idealism and pragmatism. He believes cheap fertilizer can reduce hunger and conflict—but he also understands that ideals don’t ship themselves. They require infrastructure, capital, and engineering. Hydropower plants. Chemical plants. Technical partnerships. Long time horizons.

Noguchi is often called the father of electrochemical engineering in Japan. His legacy, however, is not simple. He invested heavily in development in Korea and Manchukuo in cooperation with the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. After World War II, under the American occupation, his company is dissolved, and successor lineages include Chisso Corporation, and portions of Asahi Kasei, Sekisui Chemical Company, and Shin-Etsu Chemical.

The history raises difficult questions—and it should. But the core operating insight that powers Asahi Kasei’s story survives: in a resource-constrained country, mastery of energy, chemistry, and process engineering can substitute for what you don’t have in the ground. Pair that with patient investment and a sense of mission, and you can keep reinventing for a century.

Those values—resource efficiency, patient capital, technological self-reliance, and social purpose—become the company’s early DNA. And as Japan heads into the turbulence of the 20th century, Asahi Kasei will need all of it to rebuild, diversify, and eventually help invent the battery that changes the world.

III. The First Transformation: From Ammonia to Diversified Chemicals (1950s–1970s)

In 1945, Japan was shattered. Factories and ports were rubble. Food was scarce. And for companies that had been intertwined with the wartime economy, there was no clean reset—only a hard reckoning. For Asahi Kasei, the situation was existential. Assets in Korea and China were gone. The old industrial order was being dismantled under the American occupation. Whatever the company would become next, it would have to be rebuilt.

And then, almost improbably, Japan launched one of the greatest industrial recoveries in history. Within a couple of decades it was back—exporting, innovating, compounding. Asahi Kasei rode that wave, but it didn’t do it by simply returning to ammonia and fiber. It reinvented itself into something much broader: a diversified chemicals company.

That pivot was driven by Kagayaki Miyazaki, Asahi Kasei’s fifth president, who set a clear direction: the company should “be a diversified chemical company with clothing, food, and housing products.” Not as a slogan, but as an operating mandate. Under Miyazaki, Asahi Kasei pushed into three major new businesses—nylon fiber, synthetic rubber, and new construction materials. Decades later, those bets still sit at the core of the portfolio.

Miyazaki’s advantage wasn’t just boldness; it was time horizon. He made a habit of talking with young employees about what the world would need 10 or 20 years out. That kind of long-range thinking—rare anywhere, especially inside a manufacturing business still recovering from war—became part of Asahi Kasei’s culture.

The best example is the naphtha cracker. This is the kind of facility that defines modern petrochemicals: you take naphtha, apply extreme heat—around 800 degrees Celsius—and “crack” the molecules into lighter hydrocarbons you can turn into plastics and chemical building blocks. It took seven years just to plan. And the cost was so large it was equivalent to the company’s annual turnover.

That’s the bet: one project, one facility, on a timeline that doesn’t fit neatly into any fiscal year narrative. But this was the Japanese industrial model at its best—patient capital, heavy engineering, and the willingness to spend big now to control your destiny later.

In April 1972, the naphtha cracker in Mizushima, Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, began operating. It wasn’t just a plant turning on. It was Asahi Kasei declaring that it intended to compete as a true, integrated chemical company.

The rest of the era reads like a deliberate build-out of industrial optionality. The company expanded into acrylonitrile in 1962. It entered construction materials with Hebel autoclaved aerated concrete panels in 1967. It started up a glass fabric business in 1971. It launched an ethylene plant in 1972. And in November 1972, it formally established Asahi Kasei Homes as a subsidiary—building on the earlier launch of Hebel Haus steel-frame homes.

The housing business, in particular, is one of those Asahi Kasei moves that sounds strange until you see the logic. Miyazaki had a desire to “somehow provide a splendid house like those found in Europe.” But the execution wasn’t aesthetic—it was technical. In 1970, Asahi Kasei built the first Hebel Haus using autoclaved aerated concrete panels at a model home park in Kamata, Tokyo. AAC is lightweight, fire-resistant, and a strong thermal insulator. In other words: it’s a materials-science product that just happens to turn into a home. This is how a chemicals company ends up with a housing division that actually makes sense.

Another key moment came earlier, in 1952, with the establishment of Asahi-Dow Co., Ltd., a petrochemical joint venture that produced materials like polystyrene and cling film. In July 1952, it launched as a 50–50 partnership between Asahi Kasei and Dow Chemical International Ltd. But the start was rough. The fiber product Saran had real strengths—resistance to water and chemical agents—but it struggled as apparel fiber, especially on dyeability and texture. In the first three years, cumulative net loss reached 720 million yen. Asahi Kasei had promised Dow it wouldn’t be asked to add capital, so Asahi Kasei covered the deficit itself.

Eventually, Saran found its market—not in clothing, but as wrapping film for food products like ham and sausage. And with that, the business turned steadily profitable.

The bigger significance of Asahi-Dow wasn’t just one product getting fixed. It was that Asahi Kasei had built an entry ramp into petrochemicals—through partnership, imported know-how, and the willingness to absorb losses long enough to learn what worked.

That becomes the template. Enter new fields through technology acquisition or partnership. Accept early losses as tuition. Iterate until you find the right application. Then invest to scale and integrate. The diversification that followed—into petrochemicals, housing, and later into areas like medical devices, electronics, engineered resins, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals—rhymed with this same pattern across the decades.

What’s striking is not that Asahi Kasei diversified. Lots of conglomerates diversify. What’s striking is how often these moves turned into real, durable businesses rather than a pile of disconnected experiments. The connective tissue was the same thing Noguchi baked in from the beginning: process engineering, materials science, and the patience to play long games.

By the time the 1970s ended, Asahi Kasei was no longer just a fertilizer-and-fiber company. It had become a diversified chemical enterprise with deep capabilities in materials, a serious foothold in housing, and the industrial backbone to pursue whatever came next.

And what came next would start, quietly, in a research lab—where a young chemist began exploring a strange conductive polymer that most battery experts weren’t paying attention to.

IV. The Lithium-Ion Battery: When a Chemicals Company Changed the World (1981–1991)

The year is 1981. Personal computers are just starting to show up—IBM will launch its PC later that year. Mobile phones are still bricks: rare, expensive, mostly for executives and emergency services. The idea that billions of people might one day carry pocket-sized computers everywhere they go still sounds like sci-fi.

Inside Asahi Kasei’s Kawasaki research facility, a 33-year-old chemist named Akira Yoshino is looking for his next problem. He’d joined the company right after finishing his master’s degree in petrochemistry at Kyoto University in 1972. He’d spent the 1970s on Asahi Kasei’s Exploratory Research Team, hunting for new general-purpose materials. Some projects went nowhere. Which, in a way, is the whole point of exploratory research. But it left Yoshino searching for something that felt promising.

Then he comes across polyacetylene, a strange electroconductive polymer discovered by Hideki Shirakawa—work that would later earn Shirakawa the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000. Yoshino starts thinking: could a plastic material like this work as an electrode in a rechargeable battery?

Here’s the counterintuitive edge Yoshino had. He wasn’t a battery lifer. “I didn’t know about conventional wisdom in the field of battery technology,” he would later say—and he believed that ignorance was an advantage.

At Kyoto University, Yoshino had been shaped by a mindset captured in a motto from Professor Kenichi Fukui: doubt conventional wisdom. Yoshino brought that instinct into industry. And crucially, Asahi Kasei gave him room to act on it. He wasn’t told, “Go invent the battery of the future.” He was allowed to follow an interesting materials question and see where it led.

By late 1982, Yoshino had been exploring the idea of a plastic anode made from polyacetylene. What he needed was the right cathode to pair with it. In a scene that feels almost too perfect, Yoshino later recalled that on the last day of 1982—while cleaning his desk—he came across a technical paper from 1980 he had requested but never read. It was coauthored by John B. Goodenough, and it described a lithium cobalt oxide cathode.

Yoshino and a small team decided to try it. They paired Goodenough’s lithium cobalt oxide cathode with Yoshino’s polyacetylene anode, and they experimented with other anode materials too—especially different forms of carbon.

In 1983, Yoshino fabricated a prototype rechargeable battery using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode and polyacetylene as the anode. It worked, but polyacetylene didn’t. It wasn’t stable enough for the real world.

So Yoshino kept going. In 1985, he landed on the breakthrough: petroleum coke as the anode. Petroleum coke is a carbon-rich byproduct of oil refining, and at the molecular level it contains spaces where lithium ions can tuck themselves in. That seemingly simple swap—carbon hosting lithium ions instead of metallic lithium—was the move that made the modern lithium-ion battery commercially viable.

It also made it dramatically safer. Metallic lithium at the anode is volatile; it can ignite or explode when exposed to air or water. By avoiding metallic lithium, Yoshino’s design reduced the fundamental risk profile of the battery. And because lithium ions shuttle in and out of host materials—intercalated in both the anode and the cathode—the battery can be recharged many times with a long working life.

But invention isn’t just chemistry. It’s engineering, safety, and manufacturability. Yoshino’s team developed an extremely thin polyethylene-based porous membrane to separate the anode and cathode—a critical safety feature. Lithium ions can pass through the pores, but if the battery overheats, the membrane melts and the pores close, effectively shutting the battery down before a runaway event.

He also developed an aluminum foil current collector for the cathode, improving performance by enabling high voltage and high storage capacity.

In 1986, Yoshino commissioned a batch of lithium-ion battery prototypes. The safety data mattered beyond the lab. The U.S. Department of Transportation issued a letter stating that these batteries were different from metallic lithium batteries—an important distinction, because it meant they could be shipped by air. Without that, there’s no global consumer electronics supply chain. There’s no commercialization.

Yoshino filed a patent in 1985. The technology reached consumers in 1991, when Sony commercialized the first lithium-ion battery. The first prototype of the modern Li-ion battery—using a carbonaceous anode rather than lithium metal—had been developed by Yoshino in 1985, and then brought to market by a Sony and Asahi Kasei team led by Yoshio Nishi in 1991.

As the battery era began, Yoshino’s role evolved with it. He was promoted to manager of product development for ion batteries in 1992. In 1994, he became manager of technical development at A&T Battery Corp., a lithium-ion battery joint venture between Asahi Kasei and Toshiba.

Step back and this is the part that matters: Asahi Kasei didn’t stumble into lithium-ion by deciding to become a battery company. It got there by doing what it had been doing for decades—pushing materials science forward, letting researchers explore, and trusting that new materials could unlock new markets.

“Asahi Kasei got into the battery field simply because it was researching new materials and was able to develop the lithium-ion battery precisely because it was not a specialist in the field. Had I been a researcher with a battery manufacturer, I probably wouldn’t have encountered polyacetylene.”

That’s the paradox at the heart of the invention. The experts knew too much. The battery industry was chasing the next rechargeable battery, but couldn’t commercialize it because it couldn’t find the right anode material. Carbon anodes were widely considered a dead end. Yoshino, coming from a chemicals company without the same institutional assumptions, tried what the specialists wouldn’t—and it worked.

And Yoshino, ever the teacher, tied it back to timing and culture. He later reflected that he began the basic research at 33—an age when you know enough about how companies and society work to start something ambitious, but you still have time to recover if it fails. In his view, whether Japan produces future Nobel-level breakthroughs depends on whether people around that age have the freedom to pursue ideas that don’t fit the current playbook.

Still, there was no instant iPhone moment. Even after Sony’s 1991 launch, early lithium-ion batteries mostly went into video camcorders. The world had the key technology in hand—but it would take another decade, and an explosion of portable electronics, for lithium-ion to reveal what it was really capable of.

V. The Nobel Prize Moment and What It Revealed (2019)

On October 9, 2019, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences put a spotlight on a piece of technology that most of us only notice when it fails. It announced that Akira Yoshino had created the first safe, mass-producible lithium-ion battery—the one that went on to power the rise of cell phones and notebook computers, and later became the workhorse behind electric vehicles. Yoshino received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry alongside M. Stanley Whittingham and John B. Goodenough.

In Japan, the win landed with extra weight. Yoshino became the eighth Japanese scholar to receive the chemistry Nobel—but only the second to come from industry.

That detail matters, because it runs straight into a quiet hierarchy that exists almost everywhere: academia is where the “real” science happens, and corporate labs are where science gets turned into products. Yoshino’s Nobel punctured that story. He won while still associated with a company—Asahi Kasei—not a university department.

Asahi Kasei had elevated him long before Stockholm. It named him a fellow in 2003 and, in 2005, made him general manager of his own laboratory. By 2017, Yoshino also became a professor at Meijo University, while his role at Asahi Kasei shifted to honorary fellow.

The prize wasn’t just a career capstone. It validated a whole model of innovation: long-horizon corporate R&D, real freedom for researchers, and a willingness to fund fundamental materials science without demanding an immediate product roadmap. Yoshino didn’t just invent and patent the first lithium-ion battery; he kept improving it, ultimately securing more than 60 patents related to lithium-ion technology over his career.

And the impact is hard to overstate. Lithium-ion batteries unlocked portable consumer electronics, then laptops and smartphones, and now they sit at the center of the electric-car transition. They’ve also become critical for grid-scale storage, and for military and aerospace applications.

Yoshino’s own takeaway is almost disarmingly simple: “In the end, new materials and the freedom to develop them are what trigger new products.” It’s a statement about chemistry, but even more, it’s a statement about management. Asahi Kasei didn’t demand that a young chemist prove the market before he proved the material. It let him explore—and the exploration created the market.

The Nobel also clarified something important about how lithium-ion actually came to be. This wasn’t a lone “eureka.” It was a relay race run across decades and institutions: Whittingham’s intercalation work at Exxon in the 1970s, Goodenough’s lithium cobalt oxide cathode in 1980, Yoshino’s carbon anode breakthrough at Asahi Kasei in 1985. Each advance mattered. None was enough on its own.

In hindsight, the early lithium-ion story looks like two worlds operating in parallel. The scientific world moved through papers, conferences, and incremental technical wins. The commercial world largely failed to see what was forming—even when the key work was happening inside companies. Without Sony pushing lithium-ion into a real product in 1991, the chemistry might have stayed in the lab far longer.

What makes Asahi Kasei unusual is that it could live in both worlds at once: scientific enough to recognize the importance of an academic paper, and industrial enough to turn that insight into something manufacturable and safe.

For investors, the Nobel Prize isn’t just a feel-good moment. It’s a signal that Asahi Kasei possesses a capability that’s painfully hard to build: a culture and system that can repeatedly turn fundamental materials research into durable businesses. The question that hangs over the rest of this story is whether that capability keeps compounding—and where it shows up next.

VI. From Inventor to Separator King: The Hipore Story

Here’s the question that confuses almost everyone the first time they look at Asahi Kasei: if it helped invent the lithium-ion battery, why didn’t it become a major battery manufacturer? Why did Sony get to commercialize the first lithium-ion battery in 1991? And why, today, is CATL the world’s largest battery maker while Asahi Kasei isn’t even in the top tier of cell manufacturers?

The answer is a window into how the company thinks about competitive advantage and where the profits really live. Yoshino and his teams touched many of the materials that make lithium-ion work—electrodes, electrolytes, separator films. But over time, Asahi Kasei chose not to fight the brutal, capital-intensive war of being a full battery maker. Instead, it narrowed its focus to the component where it believed it could win on technology for decades: the separator.

HIPORE separators have been commercially available since 1983. And when the lithium-ion battery market took off in the early 1990s, they became widely recognized for something unglamorous but essential: keeping batteries safe and reliable. Today, the core of Asahi Kasei’s Energy Storage business is its Hipore wet-process lithium-ion battery separator, built on more than 40 years of manufacturing history and process know-how.

Mizuho Securities analyst Yamada has attributed the strength of Asahi Kasei’s separator business to its intellectual property and accumulated manufacturing capability. Asahi Kasei’s “technological assets include ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, membrane processing and coating, as well as deep expertise in electrochemistry.”

To understand why that matters, it helps to understand what a separator actually does. It’s a thin, microporous polyolefin film that sits between the cathode and anode. Its job is deceptively simple: prevent the electrodes from touching—because that would cause a short circuit—while still allowing lithium ions to move freely through the pores. And it has to do that under stress: heat, vibration, swelling, impurities, manufacturing variation, years of charge-discharge cycles.

Getting that balance right is hard. The separator needs to be thin enough to reduce resistance, tough enough to avoid punctures, and manufactured with precisely controlled porosity. In practice, this becomes a manufacturing and materials-science problem as much as it’s an electrochemistry problem—the kind of problem a century-old chemical company is unusually good at.

Asahi Kasei is now a global leader in battery separator manufacturing through its Hipore and Celgard brands. It offers both wet- and dry-process separators for automotive batteries and energy storage systems, and it expanded its technological base and global footprint through the acquisition of Polypore International.

Within Hipore, Asahi Kasei supplies two main products: a polyolefin microporous base film membrane, and a coated membrane separator made by applying ceramic and other coatings to that base film.

The strategy around all of this is focused and, in its own way, ruthlessly pragmatic. Asahi Kasei has prioritized automotive applications and concentrated on markets where it believes it can win—Japan, South Korea, and North America—while de-emphasizing Europe, where Chinese and Korean battery manufacturers have taken the lead.

It’s also responding to a hard reality in the separator market. Asahi Kasei feels many of the same pressures as competitors like Toray and Sumitomo: Chinese manufacturers expanded capacity aggressively, prices fell, and the economics got squeezed. Asahi Kasei’s separator business, centered on Hipore’s wet-process separator, saw sales decline, and EBITDA fell sharply from fiscal 2021 to fiscal 2024.

So the company’s response hasn’t been to chase the lowest cost curve. It’s been to double down on quality, and to move closer to where the next wave of demand is expected to be—especially in North America. As one warning from inside the market puts it: “If we continue to focus primarily on Japan, we will soon face a situation where we must consider downsizing our operations.”

That’s the bet. By the fifth year of the new plant’s operation—2031—Asahi Kasei expects its Hipore business to generate over $1.1 billion in sales, up from about $230 million in 2022, with an operating profit margin of 20%. Nearly fivefold growth, with healthy profitability—if the North American EV market materializes at the scale this plan assumes.

There’s also a policy tailwind. The One Big Beautiful Bill, passed and enacted by the U.S. Congress this year, maintains a tax credit for advanced manufacturing investments like battery plants, and adds new restrictions on “foreign entities of concern.” If a project’s raw materials or component sourcing from certain countries, including China, exceeds a threshold, the project becomes ineligible for the credit. Based on publicly available data from major South Korean battery manufacturers, this benefit is estimated to exceed $1 billion annually.

On the capacity side, the planned expansion would lift Asahi Kasei’s coating capacity for lithium-ion battery separators to about 1.2 billion square meters per year—enough coated separator to support batteries for the equivalent of roughly 1.7 million electric vehicles.

For investors, this is the knife-edge. The separator business is both Asahi Kasei’s biggest opportunity and its most visible risk. The opportunity is clear: the global battery separator market was $10.6 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow to $38.1 billion by 2031. But the competitive dynamics are moving fast, pricing pressure is real, and the company is making a large, time-bound bet on geography, quality, and policy-driven supply chain shifts.

VII. The Healthcare Transformation: ZOLL, Veloxis, and the American Pivot (2012–2024)

If the lithium-ion story is Asahi Kasei at its best as an inventor, health care is Asahi Kasei at its best as a builder—using disciplined acquisitions to assemble an entirely new growth engine.

The turning point came in 2012, with the biggest deal in the company’s history at the time: the acquisition of ZOLL Medical for approximately $2.21 billion. ZOLL, based in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, makes resuscitation and critical care devices. On April 26, 2012, it became a wholly owned consolidated subsidiary of Asahi Kasei.

This wasn’t a random diversification move. It fit squarely into Asahi Kasei’s “Health Care for Tomorrow” project, where resuscitation was a priority—and where ZOLL was already a U.S. market leader with a strong international presence.

Taketsugu Fujiwara, then President & Representative Director of Asahi Kasei, put the logic plainly: “In the medical devices business, the U.S. market leads the world, not only in size and scope, but also in technological innovation, so establishing a strong infrastructure in the U.S. is an important step for Asahi Kasei.”

ZOLL’s business is life-and-death, high-acuity medicine—devices and software that support emergency care and critical care. Its portfolio spans defibrillation and monitoring, circulation and CPR feedback, data management, fluid resuscitation, and therapeutic temperature management. In other words: ZOLL sits right where outcomes, urgency, and technology collide.

And here’s the part that reveals Asahi Kasei’s acquisition philosophy. ZOLL didn’t get folded into a Tokyo headquarters bureaucracy. It continued to be run by its existing management team. That pattern—operational autonomy paired with long-term capital—would become a defining feature of how Asahi Kasei builds in health care.

Richard A. Packer, ZOLL’s CEO, said at the time: “We are delighted with this transaction and believe that it is in the best interest of our shareholders. In addition, we are convinced that Asahi Kasei's ownership will create the right environment for ZOLL and its team to continue transforming the science of resuscitation.”

The next major move followed the same playbook. In late 2019, Asahi Kasei agreed to acquire Veloxis Pharmaceuticals, and the deal carried into 2019–2020. Veloxis is a commercial-stage specialty pharmaceutical company focused on immunosuppressive drugs used during and after organ transplant surgery.

Strategically, Veloxis gave Asahi Kasei something it didn’t have: a real U.S. pharmaceutical platform. The company was explicit about the “why”: “Accelerate the creation of new health care businesses by leveraging access to innovation and clinical practices in the U.S.”

Veloxis then grew. The kidney transplant market has been increasing, and its product Envarsus XR expanded dramatically—rising from 5.2% share of tacrolimus at the time of acquisition to more than 20% later on.

Zoom out, and you can see the shape of the transformation. ZOLL and Veloxis both delivered strong organic growth. Asahi Kasei has described a revenue CAGR of 13% in its Health Care sector since 2011, with income growing even faster. By fiscal 2023, Health Care generated 20% of net sales—but an outsized 34% of operating income. In a conglomerate, that’s what it looks like when a segment becomes core.

In 2024, Asahi Kasei announced its intention to acquire Calliditas Therapeutics, a Swedish pharmaceutical company, for a total equity value of approximately SEK 11.8 billion (approximately JPY 174 billion). Calliditas developed Tarpeyo, a treatment for IgA nephropathy, a rare kidney disease.

The geographic center of gravity has shifted with the strategy. Asahi Kasei is moving the global headquarters for its Healthcare Business to the United States, in Chelmsford, Massachusetts—ZOLL’s home. Since the ZOLL acquisition a little over a decade ago, Asahi Kasei’s health care business has more than tripled.

Through all of it, the acquisition approach has stayed consistent: buy great platforms, keep the teams that made them great, and fund growth without smothering execution. As one line captures it: “Asahi Kasei's method of managing the companies in the healthcare space that we have acquired is very, very attractive.”

For investors, this is more than a new segment on a slide deck. It’s a repositioning: Asahi Kasei, once defined primarily as a Japanese materials and chemicals company, is increasingly also a U.S.-anchored health care operator—one whose growth profile and margin mix look very different from the company’s industrial roots.

VIII. The North American EV Bet: Separator Expansion (2023–2027)

The global race to electrify transportation is reshaping the battery supply chain in real time. For Asahi Kasei, it’s the rare kind of moment where a single strategic choice can either unlock a decade of growth or leave you holding the bag.

The choice they’ve made is clear: build where the next wave of EV manufacturing is being built—North America—and do it at scale.

Asahi Kasei announced it would construct an integrated plant in Ontario, Canada for both base film manufacturing and coating of its Hipore wet-process lithium-ion battery separator. Alongside the announcement, it concluded a basic agreement with Honda Motor Co., tying the project to an automaker with an explicit, long-term EV roadmap.

The initial investment is massive by any standard: approximately 180 billion yen (about CAD$1.56 billion) to install around 700 million square meters of annual Hipore separator capacity at the Canadian facility.

Then came the physical commitment. Asahi Kasei Battery Separator Corporation broke ground on a new separator manufacturing facility in Port Colborne, Ontario. The plant is expected to begin commercial production in 2027, subject to permits and approvals, and it’s planned to operate as a joint venture facility between Asahi Kasei and Honda.

In its first phase, the facility is expected to create more than 300 full-time jobs. Capacity is planned at roughly 700 million square meters of coated separator per year—positioned as enough to supply around one million EVs annually.

“This facility signifies a bold step in advancing innovation in battery technology,” said Koshiro Kudo, President and Representative Director of Asahi Kasei Corporation. “We are establishing a center of excellence here in Port Colborne that will further position Asahi Kasei as a leader in meeting the growing demand for electric vehicle battery separators across North America, helping drive the energy transition forward with cutting-edge technology.”

Port Colborne also carries a symbolic milestone: it’s expected to be Canada’s first large-scale wet-process separator facility, a meaningful foothold for Asahi Kasei’s energy storage ambitions.

Honda made the strategic rationale explicit from its side, too. “To achieve carbon neutrality, Honda is targeting 100% of global sales from EVs and FCVs by 2040,” said Manabu Ozawa, Managing Executive Officer of Honda. “The separator is an extremely important component that contributes to higher performance and durability of batteries. We are very excited to partner with Asahi Kasei, having outstanding technological capability and broad expertise regarding separators. This will allow us to realize highly competitive EVs that can meet future growing demand in the North American market.”

The joint venture structure also tells you something about how both companies are thinking about risk. The ownership is set at 75% for Asahi Kasei Battery Separator Canada Corporation and 25% for Honda Canada Inc., with Honda investing approximately C$417 million (about US$300 million) through a mix of new shares and other investment.

And it isn’t only Honda. Asahi Kasei and Toyota Tsusho have also established a strategic partnership to supply automotive lithium-ion battery separator in North America. Beginning in mid-2027, Asahi Kasei is set to supply coated Hipore separator from its new coating facility under construction in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Put together, the North American strategy is straightforward: make Hipore the separator of choice for Japanese and Korean automakers building EVs in North America, and manufacture locally to align with U.S. policy incentives that discourage China-linked sourcing.

But the strategy also comes with very real execution risk—because the EV rollout is not a smooth curve. Honda announced it would postpone its battery plant investment by two years, citing “the recent slowdown of the EV market.” For Asahi Kasei’s separator plant, the company said it was “currently assessing the specific impact,” but expected it to be minimal, and that the planned 2027 start of operations remained unchanged because it had sales planned for other companies.

That’s the knife-edge for investors. If EV adoption accelerates as expected, this kind of capacity, on this side of the Pacific, could be transformative. If adoption stalls, Asahi Kasei risks building into overcapacity in a market where aggressive Chinese expansion has already pushed prices down.

IX. The 2016 Corporate Restructuring: From Holding Company to Operating Company

The way a company organizes itself often reveals more about its strategy than any investor presentation ever could. And by the mid-2010s, Asahi Kasei had a very modern problem: it had built a portfolio big enough to be powerful, but complex enough to get in its own way.

So in 2016, Asahi Kasei undertook a fundamental restructuring designed to make the whole machine run faster. Asahi Kasei Corp became an operating holding company through the merger of Asahi Kasei Chemicals Corp., Asahi Kasei Fibers Corp., and Asahi Kasei E-materials Corp.

On paper, this can look like bureaucratic reshuffling. In reality, it was a statement about speed and coordination. Under the old, more “pure” holding company structure, subsidiaries had wide autonomy—effectively running their own strategy, capital allocation, and talent decisions. The operating holding company model pulled more of that up to the center, so the group could make decisions and move resources across business lines more quickly.

Centered on Asahi Kasei Corp. and seven core operating companies, the group now runs through three sectors: Material, Homes, and Health Care.

In its holding company role, Asahi Kasei Corp. focuses on strategic planning and analysis, resource administration, oversight of management execution, and developing new businesses that don’t sit neatly inside any one existing unit.

This structure also supports a tougher kind of management muscle: portfolio discipline. Asahi Kasei has been explicit that it wants income growth in Health Care by expanding critical care medical devices, growing pharmaceuticals, and developing bioprocess businesses. But those are areas that require sustained, focused investment. So the company performed a portfolio review to set priorities—and to decide what would, and wouldn’t, get incremental capital.

That discipline became even more important as conditions got harder. Fiscal 2024 marked the final year of the company’s medium-term management plan built around the theme “Be a Trailblazer.” But a sharper-than-anticipated deterioration in the operating environment forced Asahi Kasei to revise down its original targets.

Still, the company said performance had improved since hitting a low point in fiscal 2022, with stronger businesses delivering higher growth. And with what it views as a stable financial foundation, Asahi Kasei has continued pushing its growth strategy and structural transformation aimed at the future.

The problem is that the market hasn’t fully bought the story. As Asahi Kasei has put it, “This indicates a gap between what we believe to be the value of the Asahi Kasei Group and the value that investors perceive.”

That “value gap” is a familiar theme in Japanese conglomerates. Many Western investors discount diversified models in favor of pure plays. For Asahi Kasei, the open question is the one that matters most: does tighter integration make the portfolio worth more than the sum of its parts—or does complexity keep dragging the valuation down?

X. The Homes Business: An Underappreciated Competitive Moat

A chemicals company that builds houses sounds, at first, like exactly the kind of corporate sprawl conglomerate critics love to mock. But in Asahi Kasei’s case, the Homes business isn’t a quirky side quest. It’s a durable, cash-generating franchise built on the same thing that powers the rest of the company: materials science, process discipline, and long time horizons.

The modern housing story starts with Hebel Haus. Asahi Kasei built the first Hebel Haus steel-frame home in 1970 at a model home park in Kamata, Tokyo, using autoclaved aerated concrete panels—AAC, also known in Japan as ALC.

AAC is the sort of material a chemical company would fall in love with. It’s lightweight, fire-resistant, and an excellent thermal insulator. And it’s built for longevity: the basic structure of a Hebel Haus is designed for a service life of more than 60 years. In Japan’s demanding climate—rain, snow, humidity, harsh sunlight, and big seasonal swings—that durability isn’t a “nice to have.” It’s the product.

That durability shows up in how customers talk about it. In Japan, post-build satisfaction surveys are a serious business, and Hebel Haus has ranked number one in the steel construction category for seven consecutive years. An overwhelming majority of owners say they plan to live in their Hebel Haus long term, and most say they would recommend it to family and friends.

Financially, the Homes segment is more than just new builds. It includes construction contracting, renovations, rental management, and the supply of building materials like lightweight aerated concrete, insulation materials, and components. The segment has performed well, supported by higher average unit prices and an expanding rental management operation.

And while the core of the business is still Japan, Asahi Kasei has also been building an overseas foothold. It acquired ODC Construction, LLC, a Florida-based subcontractor, expanding into a state that ranked second in the U.S. for residential building permits in 2023.

That move matters because it hints at how Asahi Kasei is thinking about the next chapter. Japan is an aging, population-declining market. Florida is the opposite: a fast-growing state with heavy in-migration and an active construction cycle. It’s a very different demand curve—and a way to keep the housing engine growing even as Japan’s demographics tighten.

For investors, Homes plays two quiet but important roles. First, it’s steady cash flow—exactly the kind of ballast that helps fund long-horizon R&D and big strategic bets elsewhere in the portfolio. Second, it’s a subtle form of integration: Asahi Kasei’s materials expertise doesn’t just end at a resin pellet or a membrane film. In housing, it becomes a lived-in product, with durability and safety as the differentiators—advantages that are hard for pure-play homebuilders to replicate.

XI. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

After a century of reinvention, Asahi Kasei starts to look less like a “miscellaneous conglomerate” and more like a company running a repeatable system. The businesses change. The underlying moves rhyme. Here are the patterns—and the lessons—that show up again and again.

The Diversification Paradox

Asahi Kasei is proof that diversification doesn’t automatically mean value destruction. It expanded into materials, homes, and health care without losing its technical edge, because it didn’t diversify at random. It tends to enter new fields when it can bring something real—materials science, chemistry, or process engineering—and when that capability can become a durable advantage, not just a line item on a portfolio chart.

Patient Capital and R&D Freedom

“Asahi Kasei got into the battery field simply because it was researching new materials and was able to develop the lithium-ion battery precisely because it was not a specialist in the field.” That line is basically the company’s innovation thesis in one sentence.

Yoshino didn’t get a perfectly defined product brief. He got room to explore. Asahi Kasei repeatedly funded the kind of early-stage, high-uncertainty work that looks inefficient—right up until it produces something world-changing.

The Acquisition Playbook

ZOLL, Veloxis, and Calliditas point to the same M&A philosophy: buy strong platforms, then don’t break what made them strong. Asahi Kasei has consistently emphasized giving acquired companies autonomy while supplying capital and long-term support. ZOLL kept running with its existing management team after the deal and grew under Asahi Kasei’s ownership. In health care especially, that balance—resources without suffocating integration—has been a competitive weapon.

Geographic Pivots

Asahi Kasei has also shown a willingness to move its center of gravity when the growth moves. In health care, that means shifting the global headquarters to the United States. In separators, it means building capacity in North America because staying Japan-centric would eventually force the business into contraction. Many industrial companies talk about globalization; fewer are willing to reorganize the company around it.

The Vertical Integration Question

One of Asahi Kasei’s most instructive decisions is also one of its least intuitive: it helped invent lithium-ion batteries, and then chose not to become a major battery manufacturer.

Instead, it focused on the separator—the component that best matched its strengths in materials and manufacturing precision. That kind of strategic restraint is rare. It’s the discipline to say: we want exposure to the industry, but only where we can be structurally advantaged.

Sustainability as Embedded Philosophy

Asahi Kasei’s sustainability story isn’t something bolted on late. It reaches back to the beginning—Noguchi’s belief that industry should raise living standards, powered by Japan’s natural advantages like hydropower. Today, the group has nine hydroelectric power generation plants in the Nobeoka region, supplying about 14% of the electricity it used in Japan in 2018. Not a marketing campaign. An operating reality that traces back more than a century.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low to Moderate

On paper, separators look like “just another film.” In reality, Asahi Kasei’s position is protected by a moat made of know-how and time. The separator business sits on extensive intellectual property, and on a bundle of capabilities that are hard to assemble quickly: ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, membrane processing, coating, and deep electrochemistry expertise. Add more than 40 years of manufacturing experience, and you get meaningful barriers to entry.

Capital requirements reinforce that. A single new integrated plant—like the Canadian project—demands massive investment. Still, the market has already shown that barriers aren’t absolute. Chinese competitors, backed by scale and state support, have proven they can muscle into industries that once seemed impenetrable.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

The base inputs—polyethylene and other petroleum-derived chemicals—are largely commodities, which usually limits supplier power. The exception is the specialized grades of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene and other highly specific inputs where supply can be tighter and qualification requirements can narrow the field.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Asahi Kasei sells into a customer base that is concentrated, sophisticated, and price-sensitive: major battery manufacturers and automotive OEMs. These buyers have real negotiating leverage, especially when multiple suppliers can meet spec. Partnerships like the Honda arrangement help offset that risk somewhat by anchoring demand and tightening the relationship, but the fundamental dynamic remains: the buyers are big, and they know it.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate but Rising

The biggest long-term substitute risk is solid-state batteries. If solid-state designs scale, they could reduce—or in some architectures, potentially eliminate—the role played by today’s liquid-electrolyte separators. Asahi Kasei has been researching solid-state electrolyte technology, but the timeline and commercial breakthrough point are still uncertain.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is a crowded, hard-fought market. Competitors include Toray Industries, Sumitomo Chemical, SK Innovation, and a growing roster of Chinese manufacturers. And when capacity gets ahead of demand, pricing becomes the weapon of choice. The pressure shows up directly in results: Asahi Kasei’s separator EBITDA fell sharply from fiscal 2021 to fiscal 2024, reflecting how unforgiving the economics can get when the market turns.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Real and important. Separator manufacturing is capital-intensive, and the winners tend to be the ones who keep their plants running hot at high utilization. A facility with the scale of the Canadian plant—planned at 700 million square meters a year—illustrates what it takes to compete.

Network Effects: Minimal. This isn’t a consumer platform business. But long customer relationships and the qualification process create a different kind of stickiness.

Counter-Positioning: There’s an argument here. Asahi Kasei has leaned into high-quality wet-process separators for premium, performance-critical applications, while many Chinese competitors have targeted sheer volume and lower-end segments. That choice can look conservative in boom times, but it becomes a differentiator when customers start caring more about reliability, safety, and consistency than about the last dollar of cost.

Switching Costs: Moderate to high. Separators aren’t plug-and-play. Battery makers qualify materials through extensive testing, and once a separator is designed into a cell, switching suppliers introduces risk, delay, and expense. That friction creates defensibility—especially for suppliers with a track record.

Cornered Resource: Asahi Kasei’s deep intellectual property portfolio—built over four decades of separator development—functions as a classic cornered resource. So does the accumulated institutional knowledge embedded in its people, including battery pioneers like Akira Yoshino.

Process Power: This is one of Asahi Kasei’s most durable advantages. Membrane technology is a craft as much as a science, and the company’s expertise—built not only in separators but across other membrane-based products like medical filters—creates manufacturing and quality advantages that are difficult to replicate.

Branding: Limited, because this is a B2B components business. But within the industry, Hipore has earned real recognition, which matters when reliability and safety are part of the purchasing decision.

Key Metrics to Track

For investors monitoring Asahi Kasei’s ongoing performance, two indicators do an unusually good job of telling you whether the strategy is working:

-

Healthcare Segment Operating Margin: This is the scoreboard for the ZOLL, Veloxis, and Calliditas playbook. Watching operating income relative to segment sales helps reveal whether these businesses are compounding value under Asahi Kasei—or simply adding revenue without durable profitability.

-

Separator Business Revenue Growth: The bull case is a major scale-up—from roughly $230 million in 2022 to over $1.1 billion by 2031. The key is whether the ramp happens as the North American footprint comes online, and whether growth arrives with pricing and margins that justify the investment.

XIII. Bull Case and Bear Case

The Bull Case

The bull case for Asahi Kasei comes down to three big “if this goes right” engines.

First: health care keeps compounding. ZOLL and Veloxis have already shown they can grow under Asahi Kasei’s ownership, and the company has cited a 13% revenue CAGR in the Health Care sector since 2011. If that trajectory continues—and if the planned Calliditas acquisition delivers another leg of growth in specialty pharma—health care could become the primary earnings story. At that point, the narrative flips: Asahi Kasei starts to look less like a chemicals conglomerate with a medical segment, and more like a global health care operator that also happens to own valuable materials and housing franchises.

Second: the North American separator bet works. If EV adoption accelerates and policy-driven supply chain localization pushes more battery manufacturing into North America, Asahi Kasei’s move to build domestic separator capacity could look brilliantly timed. Management has said it expects the Hipore business to reach over $1.1 billion in sales by 2031 with 20% operating margins—nearly five times larger than in 2022. If that happens, separators stop being a volatile side story and become a major profit contributor again.

Third: the conglomerate discount narrows. If investors begin to see the portfolio as an integrated set of capabilities—not a collection of unrelated businesses—the valuation can change even without heroic execution. In the best case, the market buys the argument that Asahi Kasei’s edge is transferable: materials science feeding into high-performance building products, membrane and filtration expertise reinforcing battery components, and cash flows from steady businesses funding long-horizon R&D. A better corporate governance backdrop in Japan could help that reappraisal happen faster.

The Bear Case

The bear case is also three parts—and each one attacks a pillar of the plan.

First: separators stay structurally pressured. Chinese competitors have added capacity aggressively, which has pushed pricing down across the industry. Asahi Kasei’s separator profitability has already been hit hard, and a North American footprint doesn’t automatically fix that if the global price umbrella keeps falling. In that world, the company can build impressive capacity and still struggle to earn attractive returns on it.

Second: the EV transition disappoints—or shifts under Asahi Kasei’s feet. Honda’s decision to postpone its battery plant investment by two years, citing a slowdown in EV demand, is a reminder that adoption doesn’t move in a straight line. If hybrids remain dominant longer than expected, demand for separators may ramp more slowly. And if solid-state batteries arrive faster than anticipated, the risk isn’t just slower growth—it’s that parts of today’s separator investment case could change meaningfully, raising the specter of stranded assets.

Third: Japan becomes a heavier anchor. The Homes business is steady, but Japan’s aging, shrinking population is a real headwind for long-term domestic housing demand. And while Asahi Kasei is global, parts of the Materials segment remain tied to Japanese industrial cycles. If domestic demand softens and the company can’t offset it with overseas growth, the portfolio can start to look less like diversification and more like drag.

XIV. Conclusion: A Century of Reinvention

In December 2019, when Akira Yoshino walked onto the Nobel stage in Stockholm, he was never just accepting a medal for a better battery. He was the public face of something rarer: a Japanese industrial company that had spent decades funding curiosity, tolerating dead ends, and treating materials science as a long game.

That thread runs straight back to Shitagau Noguchi and the company’s founding idea:

"Our ultimate mission is to improve people's standard of living by supplying an abundance of the highest-quality daily necessities at the lowest prices."

Across a century, the products changed almost beyond recognition. Ammonia fertilizer that helped feed a nation. Rayon and fibers that reduced dependence on imports. Petrochemicals and construction materials that rode Japan’s postwar rebuild. Homes engineered around durability and safety. A life-saving U.S. critical care platform. Immunosuppressant drugs for transplant patients. And, in a quiet but world-shaping way, the separator films that help make lithium-ion batteries safe enough for everything from phones to cars.

That’s the part that makes Asahi Kasei so hard to categorize—and so easy to misunderstand. It’s a conglomerate, yes, but not a random collection of assets. It’s a company that keeps migrating toward the places where its core strengths—chemistry, membranes, manufacturing precision, and patient capital—can create an edge.

Today, it’s in another transition. Health care has become a core earnings driver and is shifting the company’s center of gravity toward the United States. The separator business is making a high-stakes bet that North American EV supply chains will be built locally, and that quality and safety will be rewarded. Legacy materials businesses are being reshaped under tougher global competition. And Homes remains the steady base—expanding overseas even as Japan’s demographics tighten.

For investors, the appeal is the mix. You get exposure to the EV transition through a critical battery component business. You get a compounding health care platform built through disciplined acquisitions. And you get a housing franchise that can generate steady cash to fund the next wave of bets. The tradeoff is real, too: conglomerate complexity, execution risk on huge projects, and uncertainty about how quickly electrification—and battery technology itself—evolves.

What’s clear is why Asahi Kasei has lasted this long. It has repeatedly survived disruption by committing to two principles: invest patiently in foundational technology, and stay flexible enough to pivot when the world changes.

The device you’re using right now is powered by a lithium-ion battery. Inside it is a separator that could very well trace back to Asahi Kasei. The chemist who helped make that battery practical spent his entire career at a company most people outside Japan barely recognize. And that company has been reinventing itself for more than a hundred years.

That’s the Asahi Kasei story. The question now isn’t whether it has a remarkable past. It’s whether its next reinvention will be just as consequential.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music