Toray Industries: From Rayon to Running the Skies

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

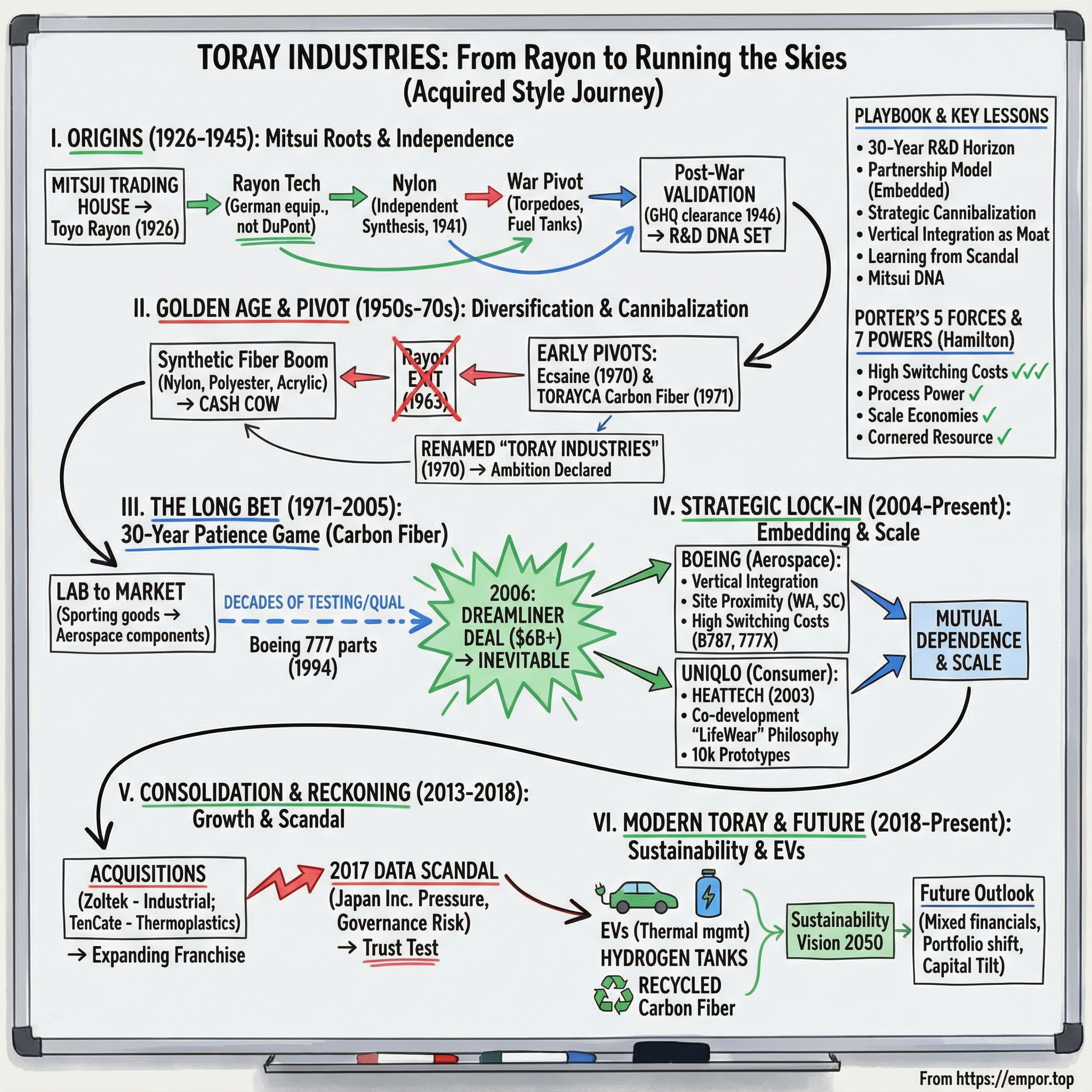

Picture this: you’re boarding a Boeing 787 Dreamliner for a long-haul flight—say, Tokyo to Los Angeles. You settle in. The cabin feels less cramped than you expect. The air feels better. The engines sound a little quieter. Everything about the experience seems just… newer.

What you almost certainly don’t know is that you’re sitting inside the payoff of a near-century-long corporate patience game. One that started with rayon yarn, and ended up helping reshape modern aviation.

Toray Industries is the world’s largest producer of carbon fiber, and Japan’s largest producer of synthetic fiber. On the 787, composite materials make up about half of the primary structure, including big pieces of the fuselage and wings—one of the reasons the Dreamliner is roughly 20 percent more fuel efficient than the plane it replaced.

But here’s the twist: that HEATTECH base layer keeping you warm in the cabin? Toray helped make that too.

Toray isn’t a household name because it rarely sells to households. It’s something more powerful in industrial terms: a behind-the-scenes technology partner that has made itself essential to both Boeing’s aerospace engineers and Uniqlo’s merchandisers. Different customers, different worlds, same underlying playbook.

Formally, Toray Industries, Inc. is a multinational corporation headquartered in Japan, built around deep expertise in organic synthetic chemistry, polymer chemistry, and biochemistry. It began in the most traditional place imaginable—fibers and textiles—then expanded into plastics and chemicals. And over decades, it kept climbing the value chain, from commodity threads to materials that literally hold aircraft together.

That arc is what makes Toray such a rich story. This isn’t a tale of one killer product and a fast takeoff. It’s a hundred-year bet on materials science: patient R&D, the willingness to cannibalize yesterday’s profit pools, and an almost unnerving commitment to long-term customer relationships.

Because the hardest questions in this story aren’t technical. They’re managerial. How do you keep funding research that won’t generate meaningful returns for decades? How do you make the case—internally and to shareholders—that the very business that built the company needs to be wound down? And how do you become so embedded in a customer’s operations that switching suppliers becomes nearly unthinkable?

Toray is also big enough that these choices matter. In 2025, the company reported $16.918B in annual revenue, a slight decline from 2024. By any standard it’s a major industrial player. But the most valuable thing Toray owns may not show up on a balance sheet at all: decades of accumulated know-how in fiber chemistry, process engineering, and quality control—experience that rivals can’t just buy and copy.

So in this episode, we’re going to follow Toray across a century of reinvention: the shift from commodity textiles to high-performance materials, the art of building strategic lock-in with customers, and the parts of Japan’s manufacturing culture that are both strength and vulnerability. Because this story isn’t just technological triumph. It also includes a quality data falsification scandal—an uncomfortable reminder of what can happen when delivery pressure starts to outrun the commitment to doing things the right way.

II. The Mitsui Origins & Pre-War Foundations (1926-1945)

Toray’s story begins in a very Japanese way: with a trading house, a national mission, and a long view.

On January 12, 1926, at the company’s inaugural meeting, Yunosuke Yasukawa—then a managing director of Mitsui & Co.—stood in as representative of the incorporators and spoke about “major benefits for the national economy.” He became the first chairman. A few months later, on April 16, he received permission from the governor of Shiga Prefecture to build a plant. Toray still marks April 16 as its Founding Day.

The backer wasn’t some scrappy startup fund. Toray was established as Toyo Rayon in 1926 by Mitsui Bussan, one of Japan’s two dominant trading companies of the era (the other was Mitsubishi Shoji). The sogo shosha were—and still are—an unusual institution in capitalism: massive, globally connected trading houses that think in decades, not quarters, and can bankroll industrial experiments most companies wouldn’t dare attempt.

But here’s the tell that this was not a sure thing: Mitsui didn’t even let the new company carry the Mitsui name. That was skepticism—almost a hedge—because Toyo Rayon didn’t actually have the core technology it needed. The company tried to buy rayon technology from Courtaulds and then DuPont, but the price was too high. So it did something harder: it bought equipment from a German engineering firm and hired roughly twenty foreign engineers to get the operation off the ground.

That decision mattered. This wasn’t just buying a machine; it was importing a capability.

In August 1927, Toyo Rayon began producing rayon yarn at its Shiga plant. Mitsui Bussan brought in Oskar Kohorn & Company to build the plant, train Toyo Rayon employees, and supply engineers and skilled workers. Mitsui Bussan even sent a chemical engineer—someone who had studied viscose at the University of Tokyo—to learn directly on the shop floor at Kohorn. This is the earliest version of a pattern you’ll see over and over in Toray’s history: get close to the process, internalize the know-how, and make it yours.

Then came nylon—and this is where Toyo Rayon’s DNA really forms.

Nylon was invented in 1935 by Wallace Carothers at DuPont, and DuPont publicly announced it a few years later. Toyo Rayon immediately acquired a sample through Mitsui Bussan’s New York branch and started researching it by dissolving the fiber in sulfuric acid. Patents meant they couldn’t simply copy DuPont’s process, so they had to synthesize their own polyamide and figure out how to turn it into usable fiber. By 1941—just three years after DuPont’s announcement—Toyo Rayon had completed the basic research and began building a small plant to produce Nylon 6.

That’s an astonishing pace for chemical engineering in the 1930s and early 1940s. More importantly, it set a cultural precedent: when Toray runs into a hard technical wall—especially one guarded by someone else’s IP—its instinct isn’t to give up. It’s to build an independent path.

The war then forced a brutal pivot. After 1943, Toyo Rayon converted to wartime production. Part of the Shiga plant produced torpedoes and torpedo heads for the Japanese Navy, while part of the Aichi plant produced airplane fuel tanks. The company also formed Sanyo Yushi (Oils and Fats) Ltd. as a joint venture with Mitsui Bussan to produce high-grade lubricating oil for aircraft.

By the end of the war, Toyo Rayon’s industrial base had been gutted. Rayon filament production collapsed from a peak of 18,200 tons in 1937 to just 345 tons in 1945. Rayon staple fell from 12,422 tons in 1941 to 1,840 tons in 1945.

And then came a moment that, in hindsight, reads like an origin myth for modern Toray.

In 1946, after World War II, DuPont asked GHQ—the General Headquarters of Allied Powers—to investigate Toyo Rayon for infringement of DuPont’s nylon patents. GHQ found no evidence of infringement and certified that Toyo Rayon’s nylon technology was its own.

For a Japanese manufacturer in the immediate post-war period, being cleared by the occupying American authorities wasn’t just a legal win—it was external validation of technical independence. Toray’s R&D culture had been proven on the world stage, and the template was set for the next eighty years.

If you’re trying to understand Toray’s later ability to make near-impossible long-term bets, this founding era gives you the core ingredients: patient capital from the sogo shosha model, a deep preference for internal R&D over dependency, and a willingness to invest heavily before the payoff is obvious. Those traits would become essential when Toray went hunting for the next material frontier—one that would take decades to turn into a business.

III. The Golden Age of Synthetic Fibers & First Diversification (1950s-1970s)

After the war, Toyo Rayon ran headfirst into an irony only industrial history can deliver.

They’d spent years building nylon know-how the hard way, then successfully defended their independence when DuPont tried to press its patent claims through GHQ. And yet, in 1951, Toyo Rayon turned around and signed a technology import contract for nylon with DuPont anyway.

Not because they’d lost their nerve—because the market was moving faster than anyone’s pride could keep up with. Japan’s recovery was picking up speed, synthetic fibers were about to become mass-market essentials, and Toyo Rayon needed full-scale industrial production yesterday. Tashiro—by then chairman of the board, and a former Mitsui Bussan New York hand—had Mitsui’s New York branch reach out to DuPont.

DuPont’s opening terms were steep: a 3 percent royalty on nylon sales for 15 years, plus $3 million up front. The advance payment alone was wildly out of proportion to Toyo Rayon’s balance sheet at the time. Tashiro balked, then did what Toray leaders do when confronted with a daunting constraint: he ran the numbers. He concluded that if the advance could be structured at roughly ¥500 million per year, Toyo Rayon could cover it within two years without putting the whole company at risk. He negotiated DuPont down to terms he could live with, and the deal got done.

From there, the flywheel kicked in. Alongside its own development work in nylon and acrylic fibers, Toyo Rayon imported polyester production technology from the U.K.’s Imperial Chemical Industries in 1957. By the 1960s, it had become one of the world’s leading makers across the three major synthetic fibers: nylon, polyester, and acrylic.

These were the boom years. Toyo Rayon had placed itself right in the slipstream of Japan’s high-growth era, supplying the materials that clothed a rapidly modernizing country. And the nylon business, in particular, threw off profits so large they distorted the competitive landscape.

But here’s what makes Toray Toray: even while the money was great, leadership treated it like borrowed time.

Textiles were destined to commoditize. Management could see it coming—cheaper capacity, more competitors, less differentiation. So instead of waiting to be squeezed, Toray started building the escape hatch. In 1971, the company created a department with a simple mission: find the next businesses beyond textiles. This wasn’t a panic move. It was an intentional attempt to move up the value chain before circumstances forced their hand.

The symbolism caught up with the strategy in January 1970, when Toyo Rayon renamed itself Toray Industries, Inc. It wasn’t just a rebrand; it was an announcement. The company that began as “rayon” was formally declaring it would not die as one.

And the proof of that ambition showed up in the lab. After successfully developing polyacrylonitrile-based carbon fiber, Toray began test production in 1970—tiny quantities, measured in mere hundreds of grams per month. Around the same time, it brought two new products to market: Ecsaine, an artificial suede, and TORAYCA, a carbon fiber that would eventually become the backbone of the company’s modern identity. Ecsaine arrived first, in 1970. TORAYCA followed in 1971.

This pivot had teeth, because Toray was also willing to do something most companies refuse to do: walk away from the business that made them. In 1963, it stopped producing rayon yarn entirely. No soft landing. No “legacy segment” kept alive for nostalgia. Just an exit.

Then the world reminded everyone that strategy doesn’t get to vote on macroeconomics. After the 1973 oil crisis, Toray’s performance deteriorated and operating profits fell into the red. The era of easy growth was over. But in an odd way, the timing validated Toray’s instinct. If you were going to diversify into higher-value materials, you’d rather start that journey before you’re forced into it.

By the end of the 1970s, Toray had established a pattern that would define the next half-century: make money in a big market, assume that success won’t last, and use the cash and capability to build the next platform—even if it means cannibalizing the one you’re standing on.

IV. The Carbon Fiber Bet: A 30-Year Patience Game (1971-2005)

This is the heart of the Toray story: the kind of strategic patience that sounds inspirational in a shareholder letter, and feels borderline impossible in real life.

In 1970, Toray obtained a license to Akio Shindo’s patent rights. By 1971, it was manufacturing continuous PAN-based carbon fiber—TORAYCA T300 and M40—at a production capacity of about one ton a month. In other words: barely anything. And even that “barely anything” had a bigger problem. There was no obvious market waiting to buy it.

Toray began producing TORAYCA PAN-based carbon fiber in 1971. Over time it became widely recognized for technical excellence and quality across aerospace, sporting goods, motorsport, and industrial uses. But in the early years, that reputation didn’t exist yet. What existed was a lab-born material with extraordinary properties and very few proven customers.

Because the properties really were extraordinary. Carbon fiber is dramatically lighter than steel, far stronger, and it doesn’t rust. If you’re building anything that moves—anything where weight is expensive—those are magical characteristics. The catch was that in 1971, no major industry had figured out how to use carbon fiber at scale. Aerospace was intrigued and deeply cautious. Automotive was a distant dream. So the early applications were the ones willing to pay for performance and tolerate experimentation: fishing rods, golf clubs, tennis rackets.

Even Toray acknowledged the core issue at the time: limited knowledge about what carbon fiber was good for meant the market wasn’t growing yet. But Toray’s ambition was bigger than sporting goods. The company wanted airplanes. Carbon fiber reinforced plastics had the strength and stiffness that aviation engineers cared about most, and Toray aimed to get there fast.

Which brings us to the real story: capital allocation under uncertainty.

Toray had invented something powerful, but it wasn’t a business—not for a long time. Year after year, teams had to defend continued investment in carbon fiber while other divisions, especially textiles, could generate profits right now. They had to make the case to keep spending on a product that wasn’t yet trusted, wasn’t yet specified into major programs, and didn’t yet have a large end market.

The aerospace path was the slowest, hardest version of that. Boeing and Toray began pioneering prepreg composites in the 1970s. “Pioneering” sounds triumphant, but what it meant in practice was testing, evaluation, prototypes, more testing—and long stretches where the work consumed Toray’s time and money without producing meaningful revenue.

And the reason is simple: aerospace qualification doesn’t just validate a material. It validates a supplier. Aircraft manufacturers scrutinize manufacturing consistency, quality control, delivery reliability, and engineering support. They run exhaustive fatigue tests, environmental exposure tests, and failure analyses over years. It’s an endurance sport.

By 1994—more than twenty years after Toray started commercial production—assemblies including the empennage and floor beams were being produced for the Boeing 777 program, the first commercial airplane to feature structurally significant composite parts.

But notice what that milestone implies. Composite parts were now on a major airliner, yes—but not in the most demanding places. Tail sections and floor beams mattered, but they were still a fraction of the airframe. After decades of effort, carbon fiber still wasn’t the default choice for primary structures like wings and fuselages.

Then, in the early 2000s, Boeing moved from “composites as components” to a much bigger idea: design a commercial aircraft where the primary structure would be predominantly composite. That concept became the 787 Dreamliner.

And in 2006, Toray signed the contract that finally made the decades feel inevitable instead of irrational. On April 26, 2006, Toray Industries and Boeing signed a production agreement involving $6 billion worth of carbon fiber, extending a 2004 contract. It was a massive, public validation of everything Toray had been building toward since the early 1970s.

The Dreamliner itself would go on to use an unprecedented amount of composites—about half the aircraft by weight. That was the industry crossing a line: from experimenting with composites to committing to them.

From the outside, it can look like Toray made a brilliant bet and won. From the inside, it looked like roughly thirty years of staying the course before the payoff became undeniable.

How did Toray sustain that kind of timeline? A few forces lined up. The Mitsui heritage helped create tolerance for long-duration investment. Profitable legacy businesses—especially textiles—generated cash to fund R&D. Japanese corporate governance gave management more room than many American counterparts to pursue long-term plans. And, most importantly, Toray believed in the technology early enough to keep going when belief was the only thing the carbon fiber business could reliably produce.

For anyone evaluating Toray today, this chapter cuts both ways. It’s proof that the company can outlast skepticism and build businesses on a multi-decade clock. But it’s also a reminder: not every long bet gets a Dreamliner at the end of it.

V. The Boeing Partnership: Strategic Lock-In & Scale (2004-Present)

If the carbon fiber chapter was about patience, the Boeing chapter is about leverage—the good kind. Not market power in the abstract, but the kind you earn by becoming so deeply embedded in a customer’s product that replacing you would be painful, slow, and risky.

Toray and Boeing didn’t start with a splashy, headline deal. They started the way aerospace relationships usually start: in the 1970s, pioneering prepreg composites together—high-strength carbon fiber combined with toughened epoxy resin—and grinding through years of testing, documentation, and incremental adoption.

Over time, that collaboration hardened into something much rarer: a supplier relationship that is effectively written into the airframe.

Toray’s materials have been there from the beginning on the 787 Dreamliner. TORAYCA prepreg is used for primary structural materials, including the main wings and body. And when Boeing moved on to the next evolution of its widebody lineup, Toray was positioned not as an optional vendor, but as the continuation of the platform.

Toray announced it had signed a comprehensive long-term agreement with The Boeing Company to supply carbon fiber TORAYCA prepreg for the new 777X, extending the existing supply agreement for the 787. The scale is what you’d expect from a program that spans decades: the combined value of prepreg Toray expects to supply across the 787 and 777X over the contract period has been described in the trillions of yen, with more recent estimates putting the total above $11 billion.

Big numbers, yes. But the real story isn’t the contract value. It’s the switching costs.

In aerospace, you don’t just “qualify a material.” You qualify a material, a process, a factory, a quality system, and a supplier’s ability to deliver consistently for years. The material properties are then effectively baked into the aircraft’s certification. So once a carbon fiber prepreg is specified into primary structure—wings, fuselage, critical load paths—changing it isn’t like swapping out a commodity input. It means requalification, extensive testing, and a mountain of documentation. That’s the kind of change that can take years, cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and still carry execution risk.

That’s what Akihiro Nikkaku, then president of Toray Industries, was getting at when he said: "We believe that this agreement signifies the solid mutual trust Toray has been building with Boeing through the stable supply of high quality carbon fiber materials since the 1970s. It also reflects Boeing's recognition of our world-class technology and firm commitments to expanding composites application to aircraft. Going forward, Toray will continue to duly enhance its supply capacity in line with the production increases planned by Boeing."

“Mutual trust” is the polite version. The blunt version is: Boeing can’t easily replace Toray without disrupting its own programs.

And Toray didn’t just win this position with chemistry. It reinforced it with concrete and steel—by building its supply chain where Boeing builds planes.

To serve Boeing, Toray committed to major infrastructure investments in the United States, including a plant in South Carolina designed to integrate precursor, carbon fiber, and prepreg production for the 787 and 777X. Toray Composite Materials America also announced an expansion of its Spartanburg, South Carolina facility, adding capacity that it said would come online starting in 2025.

This is the strategic core: vertical integration. Toray doesn’t only supply carbon fiber. It controls the precursor (polyacrylonitrile), the carbonization process, and the conversion into prepreg, and it supports customers with the engineering needed to use these materials in real manufacturing environments. And in aerospace, every step of that chain has to be qualified.

It’s also a relationship built for proximity. Toray’s Tacoma plant began producing carbon fiber prepregs in 1992 next to Boeing’s Composite Manufacturing Center, creating a tight supply loop. First used on the Boeing 777, that prepreg is now incorporated into the 777 and 787 primary structures—and is slated for the new 777X wing as well.

And it’s not only Boeing. Toray also secured a 15-year deal to supply Airbus with materials for wings and fuselages starting in 2011. Its T800S carbon fiber has been used in major aircraft including the Boeing 777 and 787, and the Airbus A380.

For investors, the Boeing partnership shows both sides of specialty materials at the top of the value chain. The upside is obvious: long-term contracts, high switching costs, and pricing that reflects real differentiation. The risk is just as real: when your biggest customer slows down, you feel it. Boeing’s production schedules don’t just influence Toray’s aerospace business—they largely set its rhythm. When Boeing hits turbulence, Toray does too.

VI. The UNIQLO Alliance: Reinventing Consumer Textiles (2006-Present)

If the Boeing relationship shows Toray at the far edge of aerospace engineering, the Uniqlo partnership shows something just as hard: Toray translating deep materials science into something millions of people actually wear.

The relationship started quietly in 1999 with initial transactions. But in 2006 it became a true strategic alliance. And since then, the two companies have renewed the collaboration every five years, each renewal marking a new phase of joint development and a new set of products designed to feel inevitable in hindsight.

What made the 2006 agreement unusual was how it collapsed the traditional gap between a materials maker and a retailer. Instead of Toray selling a fiber and walking away, the partnership aimed to span the entire chain—from material design to the finished garment—so the final clothing could be engineered around real customer needs.

The breakout result is HEATTECH, Uniqlo’s thermal innerwear line that became a winter staple in Japan after its introduction in 2003.

The “how” is not a slogan. It’s chemistry. As Yukiko Onishi from Toray’s global operation department explained: "The first is that it absorbs moisture and generates heat. Our bodies produce water vapour without us realising it, and the rayon inside HEATTECH fabric absorbs that vapour. When that happens, the moisture molecules try to move around, converting that kinetic energy into heat energy. The material traps the generated heat in air pockets and maintains warmth."

In other words: use rayon’s moisture absorption, engineer the blend and fabric structure, and turn something your body constantly produces into warmth you can feel—without making the garment bulky or uncomfortable.

Getting there took the kind of work that sounds absurd until you remember who Toray is. To land on the right fabric structure, the companies created more than 10,000 prototypes. That’s not “innovation.” That’s iteration at industrial scale—Toray’s R&D culture, pointed at a consumer product.

The market response rewarded the effort. Since the line’s launch in 2003, HEATTECH had sold more than 100 million items over the years that followed.

But the bigger payoff may have been what the partnership did to Toray itself. Mitsuo Ohya, chairman of Toray Industries, described it this way: "We started in 1999, but the real partnership began in 2006. Initially, Toray was technology-driven, developing products from a manufacturer's perspective. With Uniqlo, we learned to prioritize consumers—Uniqlo's LifeWear philosophy. This shifted our focus to consumer needs and feelings, not just technology. It was our biggest transformation in decades."

That’s a profound statement from a company built by chemists and process engineers. Toray’s historical pattern was: invent a material, then search for a market. Uniqlo flipped the direction: start with what customers want to feel—warmth, softness, breathability, ease of care—and work backward into polymers, blends, and manufacturing methods. The result wasn’t just a hit product. It was a new muscle Toray could use far beyond apparel.

And strategically, it rounded out the company’s portfolio. Aerospace rises and falls with aircraft production schedules. Consumer textiles move to a different rhythm. More importantly, Uniqlo proved something about Toray’s core asset: world-class materials science isn’t confined to wings and fuselages. It can also show up in the base layer you pack for a flight.

VII. Acquisition Spree & Consolidating Carbon Fiber Leadership (2013-2018)

By the early 2010s, Toray was already the world’s largest carbon fiber producer. But in materials, being first isn’t the same as being safe. Leadership only matters if you can defend it—against new competitors, new applications, and the next shift in what customers want to buy.

So Toray went on the offensive. Not with a flashy consumer brand, but with acquisitions and capacity that filled in the weak spots around its carbon fiber crown jewel.

In September 2013, Toray announced it would buy Zoltek for about half a billion dollars. The deal terms were straightforward: Toray would acquire all outstanding shares for $16.75 per share in cash, valuing the equity at approximately $584 million.

Zoltek was strategically important for one big reason: it gave Toray something it didn’t really have—low-cost, high-volume carbon fiber for industrial markets. Toray’s core strength had been premium, aerospace-grade carbon fiber. But the next wave of demand was coming from places that don’t pay aerospace prices: wind turbine blades, automotive structures, construction and infrastructure, and energy-related applications. If carbon fiber was ever going to seriously compete with steel and aluminum in cars, the economics had to change. Zoltek brought the missing ingredient: meaningful capacity in low-cost precursor and carbonization lines.

Zoltek, headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, developed, manufactured, and marketed commercial carbon fiber across exactly those industrial categories—wind energy, alternative energy, lightweight automobiles, construction and infrastructure, and oil exploration. Since 2014, Zoltek has operated as part of the Toray Group and expanded production capacity to meet rising global demand.

Toray also doubled down on the less glamorous but absolutely critical part of the carbon fiber business: precursor. In 2014, as a major aerospace composites supplier, Toray opened a polyacrylonitrile (PAN) production line in Lacq, in south-western France. That move strengthened Toray’s European footprint and gave it local supply capability for Airbus and other customers in the region.

Then came the capstone deal. On March 14, 2018, Toray announced an agreement with Royal Ten Cate B.V. to acquire TenCate Advanced Composites for 930 million euros.

If Zoltek broadened Toray down-market into industrial volume, TenCate broadened Toray across technology. The combination brought together complementary product offerings in high-performance composites for aerospace, space and communications, and high-performance industrial markets. For Toray, the attraction was clear: accelerate growth and expand its advanced composites lineup—particularly in thermoplastics—while expecting meaningful synergies.

Toray Advanced Composites, acquired in July 2018, was a leader in thermoset materials and Toray Cetex® thermoplastic-based advanced composites. With four manufacturing sites across Europe and the U.S., it supplied prepregs and related formats—fabric and unidirectional tape, bulk molded compounds, and reinforced thermoplastic laminates—used in aerospace, satellite and communications, space, motorsport, and other high-performance industrial applications.

The deeper logic was vertical integration plus capability expansion. TenCate brought thermoplastic composite expertise to complement Toray’s thermoset prepreg strength. Thermoplastics can be processed faster and are recyclable, which makes them especially compelling for automotive and other higher-volume use cases.

Taken together, Zoltek ($584 million) and TenCate (€930 million) amounted to roughly $1.7 billion in acquisition spending. This wasn’t Toray relaxing into its lead. It was Toray methodically expanding the carbon fiber franchise—stretching from premium aerospace into industrial scale, and from thermoset chemistry into thermoplastics—so the next generation of composites growth would still run through Toray.

VIII. The 2017 Data Scandal: Japan Inc.'s Reckoning

No honest examination of Toray can skip the 2017 data falsification scandal. It didn’t just create a bad headline. It exposed an uncomfortable pressure point inside Japanese manufacturing culture—and it tested Toray’s identity as a quality-first supplier.

In November 2017, Toray admitted to 149 cases of quality data falsification between 2008 and 2016. The issue involved test data on industrial fibers, including tire-strengthening cords. Because Toray’s customer list includes names like Boeing and Uniqlo, the news immediately raised a chilling question: if data can be manipulated in one part of the company, how confident should anyone feel about the rest?

The problems centered on Toray Hybrid Cord, an Aichi-based subsidiary that makes reinforcement cords used in tires, vehicle hoses, and felt used in paper manufacturing. The subsidiary said it found 149 cases out of roughly 40,000 inspections where two employees in quality assurance had altered figures. In those cases, the strength of the materials did not meet the standards promised to customers.

The most damaging part wasn’t only what happened. It was how Toray handled it.

At an emergency press conference, Toray’s president, Akihiro Nikkaku, said he had known about the manipulation for about a year. The company, he said, had not planned to disclose it because no safety problems had been found. The story only became public after a whistleblower posted comments in online chat rooms—comments that spread into rumors Toray could no longer contain.

Toray’s own timeline made the disclosure look reactive. It said the subsidiary became aware of the problem in July of the previous year, and the broader group learned in October. Public disclosure, however, came only after the anonymous online post surfaced earlier that month.

“There were no legal violations or safety problems; this was between us and our customers, and so there was no need to disclose it,” Nikkaku told reporters. Only when the internet post appeared did Toray decide it needed to “give a proper explanation before rumours spread.”

It was also happening in the worst possible moment for Japan Inc. Just weeks earlier, Kobe Steel disclosed that “data in inspection certificates had been improperly rewritten” for some aluminum and copper products that failed to meet specifications. Around the same period, other major Japanese manufacturers—including Nissan and Mitsubishi Materials—were dealing with their own quality scandals. The cumulative effect threatened something far larger than any single company: trust in Japanese manufacturing, at a time when competition from China and South Korea was intensifying.

As for why it happened, the explanations pointed to something uncomfortably ordinary. Two quality control managers led the falsification, and one driver was pressure to meet product delivery deadlines. It’s the classic failure mode: front-line employees squeezed by targets, problems kept quiet, and a culture that doesn’t surface bad news until it becomes impossible to hide.

Nikkaku’s public response was explicit: “We are taking this issue very seriously. In the next three years, we are committed to creating a product quality data system that won't allow misconduct.”

For investors, the scandal raised real concerns about governance and culture. At the same time, a few contextual points mattered. The falsification occurred at a subsidiary producing industrial cords, not in Toray’s aerospace-grade carbon fiber operations. The Boeing and Airbus qualification regimes—far more stringent and continuously audited—were not directly implicated. And Toray’s remediation plan emphasized building computerized quality management systems, suggesting an attempt at structural change rather than a purely cosmetic response. The company’s share price also recovered relatively quickly, implying the market saw the long-term damage as containable.

Still, the larger lesson cuts deeper than Toray. Japan helped pioneer modern quality control. So when data falsification shows up inside that system, it’s a signal that something has slipped—whether due to understaffing, delivery pressure, or a reluctance to escalate problems. Toray’s scandal wasn’t just a blemish. It was a warning about what happens when the demand to hit the ship date starts to outrun the discipline to tell the truth.

IX. The Modern Toray: Sustainability, EVs & the Future (2018-Present)

After the 2017 scandal, Toray didn’t just talk about trust and reform. It also sharpened its story about what it exists to do in the world.

In 2018, Toray formulated the Toray Group Sustainability Vision, laying out four perspectives for what it wants the world of 2050 to look like—and the initiatives required to get there. The mission statement is broad but telling: Toray aims to provide solutions to global challenges that sit at the intersection of development and sustainability—an ever-increasing global population, aging societies, climate change, water shortages, and resource depletion—through innovative technologies and advanced materials.

That framing matters. It positions Toray less as a seller of products and more as a materials science engine pointed at megatrends. Climate change, electrification, and tighter resource constraints aren’t just “ESG themes” here; Toray sees them as demand drivers for what it already does best.

One of the most immediate arenas is electric vehicles. Toray Resin and Toray Resin Mexico have been showcasing TORELINA™ PPS technology, used in materials for thermal management and cooling in next-generation EVs. The pitch is straightforward: as EVs get more demanding, lightweighting and performance improvements can meaningfully extend vehicle performance, and PPS-based materials become part of the toolkit for building cars that are more efficient, safer, and more environmentally friendly.

Toray is also pushing deeper into automotive relationships. In April 2024, Hyundai Motor Group signed an agreement for strategic cooperation with Toray Industries to advance material innovation for a new era of mobility. As Toray’s Chairman Ohya put it, “Toray Industries has developed innovative technology and materials focusing on electrification and sustainability to address the needs of customers in the constantly evolving automotive industry.”

Then there’s hydrogen—another place where “advanced materials” stops being abstract and becomes literal infrastructure.

Toray has pointed out that it supplies high-strength carbon fiber and liner resins for high-pressure hydrogen tanks. Its T700S standard modulus fiber has become the benchmark for Type IV tanks that store compressed gas hydrogen (CGH2) at standard pressures of 350 and 700 bar for fuel cell electric vehicles.

And this isn’t just R&D positioning. Toray Composite Materials America (Toray CMA), described as the largest producer of carbon fiber in the United States, is a primary supplier of carbon fiber into alternative energy, the emerging hydrogen economy, and the broader clean energy push. Its South Carolina expansion is expected to increase supply of industrial-strength carbon fiber for compressed natural gas, hydrogen tanks, and other pressure vessel applications.

Toray is also investing in recycled carbon fiber. The logic is simple and compelling: recycled carbon fiber has a lower carbon footprint than virgin material. Toray says it is advancing recycling technologies, building a strategic business model around recycled carbon fiber, and recommending adoption to customers looking to reduce the environmental impact of their products.

Financially, the picture has been mixed—exactly what you’d expect from a global manufacturer trying to pivot while managing cyclical end markets. In its Q2 2025 results, Toray reported consolidated revenue of ¥1,234.3 billion, down 4.6% year over year. Operating income fell 14.2% to ¥67.9 billion, and net profit dropped 33.5% to ¥36.9 billion. At the same time, Toray increased its full-year operating income forecast for the fiscal year ending March 2026 to JPY 150 billion versus the previous fiscal year.

What’s especially revealing is how actively Toray has been reshaping the portfolio. In October 2025, the company resolved the divestment of a joint venture for battery separator film in Hungary, and in November 2025 it moved forward with the sale of its equity interest in Japan Vilene Company.

Meanwhile, the capital allocation tilt is clear: more carbon fiber composites. Toray’s capital investment in carbon fiber composites totaled 74 billion yen over the three-year period ending in 2022, and it planned to more than double that to 165 billion yen for the three-year period ending in 2025.

In other words, even after almost a century of reinvention, Toray is still doing the most Toray thing possible: taking the long view, moving money away from lower-conviction areas, and doubling down on materials that sit at the center of the next industrial cycle.

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Toray’s history can feel idiosyncratic—rayon to carbon fiber, Boeing to Uniqlo—but the underlying strategy is surprisingly consistent. A few lessons show up again and again.

The 30-Year R&D Horizon: Toray’s carbon fiber bet took roughly three decades to turn into a meaningful profit engine. In most public markets, that timeline is almost unfinanceable. Yet Toray kept funding the work through long stretches where the “business” was really just a conviction. Part of the answer is structural: Toray’s ownership is dispersed among institutional investors, with no single controlling shareholder driving short-term demands. Its largest shareholder, Nippon Life Insurance Co., holds about 6.569% of the shares. Combined with Japanese corporate governance norms that have historically favored stability, Toray had room to play the long game.

The Partnership Model: Boeing and Uniqlo are completely different customers, but Toray approached both the same way: become essential. In aerospace, that meant qualification, process control, and a vertically integrated supply chain that Boeing could trust for decades. In apparel, it meant learning to co-develop from the consumer backward—turning Toray from a technology-push manufacturer into a true product development partner. Either way, Toray didn’t just sell materials. It embedded itself into how the customer builds.

Strategic Cannibalization: Toray has repeatedly walked away from yesterday’s profit pool to fund tomorrow’s. Rayon made the company—but Toray exited rayon. Nylon and polyester powered growth—but Toray invested beyond textiles while those businesses were still strong. Most companies talk about disruption; Toray has a track record of doing it to itself.

Vertical Integration as Moat: In carbon fiber, Toray doesn’t stop at making fiber. It spans precursor chemistry through carbonization to finished prepreg, and it supports customers with the engineering required to use those materials at scale. That depth compounds over time: better quality control, tighter process learning loops, and a higher bar for anyone trying to compete with a single slice of the chain.

Learning from Scandal: The 2017 data falsification crisis tested Toray’s credibility in the harshest way—by putting “quality-first” into question. The investor-grade takeaway isn’t the headline; it’s whether the response was structural or cosmetic. Toray’s push toward computerized quality management systems points to the company trying to make misconduct harder to hide and easier to detect.

Mitsui DNA: Finally, there’s the imprint of Toray’s origin as a Mitsui-backed spinoff. That sogo shosha heritage baked in a long-term orientation—patient capital, global relationships, and comfort with building capabilities before markets fully exist. It’s not something competitors can copy, because it isn’t a tactic. It’s an inheritance. And it’s a reminder that Toray often makes the most sense when you judge it on decades, not quarters.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Carbon fiber is one of those industries that looks attractive right up until you try to enter it. You need massive up-front capital, you need years of process learning that can’t be bought off the shelf, and if you want to sell into aerospace, you need qualification cycles that can take the better part of a decade.

That’s why the market stays concentrated. A small set of companies controls most of the global share, and Toray’s leadership position rests on exactly the things that are hardest to replicate: deep R&D capability, large-scale production capacity, and long-running strategic partnerships.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Toray has reduced supplier leverage by integrating backward into precursor production—the key input for carbon fiber. Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) itself is relatively commoditized, but turning it into consistent, aerospace-grade precursor is where the proprietary know-how lives. The remaining sensitivity is energy. Carbon fiber production is energy-intensive, and higher energy costs—particularly in Japan—can pressure margins.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On paper, Boeing and Airbus have huge leverage. They’re concentrated buyers with enormous purchasing power, and they can push hard on pricing.

In practice, that leverage is capped by switching costs. Once a material system is qualified into an aircraft program, it’s effectively written into certification, manufacturing processes, and decades of accumulated test data. Changing suppliers isn’t a procurement decision—it’s a requalification program.

That’s why the relationship is both powerful and sticky. Toray and Boeing formalized that reality with long-term agreements, including the major carbon fiber supply deal signed on April 26, 2006, extending a 2004 contract. Contracts that run 15–16 years don’t just “lock in revenue.” They create bilateral dependence.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

In aerospace primary structures, carbon fiber composites don’t really have a peer. The strength-to-weight tradeoff is the whole point, and alternatives can’t match it at the same performance level.

In automotive and other high-volume markets, it’s more complicated. Carbon fiber can deliver dramatic lightweighting versus steel or aluminum, which helps fuel economy and EV range—but steel and aluminum still win plenty of programs on cost. In textiles, substitutes are everywhere, and competition from low-cost producers in places like China and Korea keeps pressure on margins.

Industry Rivalry: MODERATE

Rivalry is intense, but it’s not pure price war—especially in aerospace. It’s relationship-based, qualification-based, and measured in program wins that play out over decades. Toray competes closely with other major Japanese players like Teijin and Mitsubishi Chemical, while the textile side of the business faces a much more traditional commodity-style fight.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: ✓ Toray’s position as the world’s largest carbon fiber producer creates real advantages: lower unit costs at volume, the ability to amortize R&D over massive output, and the purchasing power and capacity planning to support long-term OEM programs.

Network Effects: ✗ There aren’t classic network effects here. But there is an indirect effect: once Toray materials are specified into major programs, that specification can create a kind of standardization benefit across the ecosystem.

Counter-Positioning: ✓ Toray invested early in carbon fiber while many competitors stayed anchored to traditional textiles. And it made hard calls—like exiting rayon entirely—while others hesitated.

Switching Costs: ✓✓✓ This is Toray's primary power. Aerospace qualification takes years, material properties get baked into designs, and the accumulated test history becomes a moat of its own. Once Toray is qualified into a program, replacing it becomes slow, expensive, and risky.

Branding: ✓ TORAYCA is a benchmark name in aerospace carbon fiber. And while HEATTECH is Uniqlo’s brand, the partnership shows Toray can help build consumer-facing winners even if it doesn’t own the label.

Cornered Resource: ✓ Proprietary precursor chemistry and manufacturing know-how, built over decades, plus long-term supply agreements with major OEMs that competitors can’t simply wish into existence.

Process Power: ✓ Toray’s advantage compounds in the factory. Integrating precursor production, carbonization, and prepreg manufacturing creates tighter feedback loops, better consistency, and a process capability that’s extremely hard to replicate quickly.

Competitive Context:

Toray competes in a field dominated by a relatively small set of global players—companies like Mitsubishi Chemical, Hexcel, SGL Carbon, and Teijin. Each has its own angle: Hexcel is deeply entrenched in aerospace structures; Teijin pushes lightweighting with its Tenax brand; Mitsubishi Chemical targets industrial cost competitiveness; and SGL Carbon serves European automotive demand.

The looming question is how durable Toray’s lead remains as Chinese producers scale aggressively with government support, and as aerospace demand inevitably cycles. Toray’s edge—vertical integration, deep OEM embedding, and accumulated process knowledge—has proven unusually resilient so far. The next decade tests whether that resilience holds when the rest of the world tries to industrialize what Toray spent half a century learning.

XII. Key Investment Considerations

KPIs to Watch:

If you want a simple dashboard for Toray, you can get most of the signal from just two things: whether carbon fiber is getting more profitable, and whether the aircraft programs that consume it are actually being built.

1. Carbon Fiber Composite Materials Segment Margins: This is the cleanest read on whether Toray is turning technological leadership into economic leadership. In the Carbon Fiber Composites business, revenue rose 3.3% to ¥300 billion, while core operating income jumped 70.7% to ¥22.5 billion, helped by the aerospace recovery and wind energy demand. The key is less the absolute level and more the direction: expanding margins suggest pricing power and scale benefits; shrinking margins suggest carbon fiber is drifting toward commodity dynamics.

2. Boeing/Airbus Production Rates: Toray’s aerospace revenue is, in a very literal sense, bolted to production schedules. The 787 and 777X programs are central. So the unglamorous but essential homework is to monitor Boeing deliveries and the production rate guidance from both Boeing and Airbus.

Bull Case:

Toray sits right where several long-cycle trends overlap: lighter, more efficient aircraft; the EV shift; bigger wind turbines; and hydrogen storage. The carbon fiber market itself is expected to grow from USD 4.82 billion in 2025 to USD 6.82 billion by 2030, a projected CAGR of 7.2%, driven by demand across aerospace and defense, wind energy, automotive, and even sporting goods.

Toray also has real structural advantages if those markets expand. Vertical integration makes it more resilient on cost and quality. Multi-decade relationships make it harder to displace. And the portfolio mix—spanning aerospace, automotive, textiles, and water treatment—gives it more than one path to growth. The Zoltek and TenCate acquisitions add a second engine: industrial-scale applications beyond premium aerospace.

Bear Case:

The most direct threat is cost competition. Chinese producers are scaling aggressively with government support, including players such as Zhongfu Shenying and Jiangsu Hengshen, pushed along by subsidies and domestic wind energy demand. Aerospace remains harder to crack because qualification is slow and unforgiving, but industrial applications are far more exposed to low-price entrants.

Then there’s cyclicality and execution risk. Boeing’s production problems can hit Toray quickly. Toray’s Japanese cost base also introduces currency risk when the yen strengthens. And while the 2017 data falsification scandal appeared contained, it left a lingering question about whether the company’s quality culture is as bulletproof as its positioning requires.

Material Considerations:

The 2017 data falsification scandal is still the governance overhang that investors can’t completely ignore. Yes, it occurred at a subsidiary making industrial cords rather than aerospace materials. But eight years of falsified data is, by definition, a cultural failure—and worth continued scrutiny.

Toray’s dependence on Boeing and Airbus is both a moat and a risk. Those relationships are sticky, but they also concentrate exposure: a major delay, slowdown, or program disruption can ripple straight into Toray’s results.

Finally, sustainability can become either a tailwind or a liability. Toray’s initiatives in recycled carbon fiber, water treatment membranes, and reducing environmental footprint may help as ESG considerations become more central to procurement. But if execution falls short, the reputational damage could cut against the “trusted supplier” identity Toray has spent decades building.

At roughly $17 billion in revenue and about $10 billion in market capitalization, Toray trades at a modest multiple relative to its technological position. Whether that’s an opportunity—or simply the market pricing in the very real competitive and cyclical risks—comes down to time horizon and tolerance for uncertainty.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music